Abstract

The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) nucleocapsid p7 (NCp7) protein holds two highly conserved “CCHC” zinc finger domains that are required for several phases of viral replication. Basic residues flank the zinc fingers, and both determinants are required for high-affinity binding to RNA. Several compounds were previously found to target NCp7 by reacting with the sulfhydryl group of cysteine residues from the zinc fingers. Here, we have identified an N,N′-bis(1,2,3-thiadiazol-5-yl)benzene-1,2-diamine (NV038) that efficiently blocks the replication of a wide spectrum of HIV-1, HIV-2, and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) strains. Time-of-addition experiments indicate that NV038 interferes with a step of the viral replication cycle following the viral entry but preceding or coinciding with the early reverse transcription reaction, pointing toward an interaction with the nucleocapsid protein p7. In fact, in vitro, NV038 efficiently depletes zinc from NCp7, which is paralleled by the inhibition of the NCp7-induced destabilization of cTAR (complementary DNA sequence of TAR). A chemical model suggests that the two carbonyl oxygens of the esters in this compound are involved in the chelation of the Zn2+ ion. This compound thus acts via a different mechanism than the previously reported zinc ejectors, as its structural features do not allow an acyl transfer to Cys or a thiol-disulfide interchange. This new lead and the mechanistic study presented provide insight into the design of a future generation of anti-NCp7 compounds.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is the causative agent of AIDS and still represents a serious global public health problem. Shortly after the isolation of the virus, an intensive search for compounds that would inhibit the infectivity and replication of the virus was initiated. Although in the last 25 years, 25 compounds were licensed for the treatment of AIDS, and significant progress has been made in the treatment of HIV-infected individuals, there is presently no curative treatment for HIV/AIDS. Although established anti-HIV treatments are relatively effective, they are sometimes poorly tolerated, highlighting the need for a further refinement of existing antiviral drugs and the development of drugs with other mechanisms of antiviral action.

In order to replicate, HIV has to undergo several major steps. First, infectious virions bind to the cellular receptors on the surface of susceptible cells. The fusion of the viral envelope with the cellular membrane ensues, and the viral core penetrates into the cytoplasm (11). The single-stranded RNA genome of the virus is copied into a double-stranded linear DNA molecule by the viral enzyme reverse transcriptase (RT) assisted by nucleocapsid molecules in the core structure (13, 28). The DNA is then transported to the nucleus as a nucleic acid-protein complex (the preintegration complex [PIC]) and is integrated into the host cell's genome by the action of a second viral enzyme, integrase (IN), assisted by the NC protein (2). The covalently integrated form of viral DNA, which is defined as the provirus, serves as the template for transcription. Retroviral RNAs are synthesized, processed, and then transported to the cytoplasm, where they are translated by an internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-based mechanism (4) to produce viral proteins. The proteins that form the viral core, encoded by the gag and pol genes, initially assemble into immature cores together with two copies of the full-length viral RNA. As these structures bud through the plasma membrane, they become enveloped by a lipid bilayer from the cell membrane that also harbors the viral Env glycoproteins in the form of trimers. Coincident with virus assembly and budding, the viral protease (PR) cleaves the Gag and Gag-Pol precursors to release the structural core proteins and Pol enzymes in their final processed forms.

The development of anti-HIV compounds continues to be very active, and many lead compounds still emerge from initial antiviral screens. Compounds with a novel mechanism of action targeting mutation-intolerant targets are of special interest. The CCHC zinc fingers and the HIV nucleocapsid NCp7 protein are examples of such targets. The zinc finger motif is essential for virus replication, and the mutation of cysteine residues, which functions as zinc binding ligands, resulted in noninfectious virus particles (15, 17, 18), further underlining the importance of NCp7 in the viral life cycle. Several classes of compounds targeting the retroviral NCp7 have been described, including 3-nitrosobenzamide (NOBA) (30), 2,2′-dithiobisbenzamide (DIBA) (31), cyclic 2,2′-dithiobisbenzamide (e.g., SRR-SB3) (37), 1,2-dithiane-4,5-diol-1,1-dioxide (29), azadicarbonamide (ADA) (32), pyridinioalkanoyl thiolesters (PATEs) (35), and S-acyl-2-mercaptobenzamide thioesters (SAMTs) (20). These compounds react with the sulfhydryl group of cysteine residues from the NCp7 zinc fingers. On the other hand, zinc chelation by a general zinc chelator, TPEN [N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine], inhibits Vif function and enhances the APOBEC3G (A3G)-mediated degradation of HIV; however, this effect is unrelated to the interaction of Vif with A3G (25, 38). Here we report the characterization of an N,N′-bis(4-ethoxycarbonyl-1,2,3-thiadiazol-5-yl)benzene-1,2-diamine (NV038) that efficiently inhibits the replication of HIV-1, HIV-2, and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV). Studies of the mechanism of action indicate that this compound interferes with an early stage of the replication cycle coinciding with an early function of the NCp7 protein of Gag and chelates the Zn2+ from NCp7.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, and virus-like particles (VLPs).

MT-4 and C8166 cells were grown and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 0.1% sodium bicarbonate, and 20 μg gentamicin per ml.

The HIV-1IIIB strain was provided by R. C. Gallo and M. Popovic. The NL4-3.GFP11 strain expressing an enhanced version of green fluorescent protein (GFP) in place of Nef was a kind gift of A. Valentin and G. N. Pavlakis (National Cancer Institute at Frederick, Frederick, MD). For all tests described, the NL4-3.GFP11 virus was obtained by DNA transfection of 293T cells with the molecular clone. Next, 1 ml of virus-containing supernatant was used to infect 8 × 106 MT-4 cells in 40 ml of culture medium. Three days after infection, the supernatant was collected and used as a viral input in the respective assays.

Vesicular stomatitis virus G protein (VSV-G)-pseudotyped HIV-1 cells containing the envelope glycoprotein of the vesicular stomatitis virus instead of the wild-type HIV-1 envelope protein were produced by cotransfecting 293T cells with a NL4.3 molecular clone lacking a functional SUgp120 (pNL4.3-ΔE-GFP) (39) and a construct encoding VSV-G.

HIV-1 VLPs were generated by the cotransfection of a codon-optimized Gag p55 polyprotein expression plasmid (33) with pVSV-g in 293T cells. These plasmids were a kind gift of M. Rosati and G. N. Pavlakis (National Cancer Institute at Frederick, Frederick, MD). To obviate specific cell surface receptor requirements, VLPs were pseudotyped with the pantropic VSV-G envelope protein.

In vitro antiviral assays.

Evaluation of the antiviral activity of the compounds against HIV-1IIIB in MT-4 cells was performed by using a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay as previously described (27). Stock solutions (10× final concentration) of test compounds were added in 25-μl volumes to two series of triplicate wells to allow the simultaneous evaluation of their effects on mock- and HIV-infected cells at the beginning of each experiment. Serial 5-fold dilutions of test compounds were made directly in flat-bottomed 96-well microtiter trays using a Biomek 3000 robot (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA). Untreated HIV- and mock-infected cell samples were included as controls. An HIV-1IIIB stock (50 μl) at 100 to 300 50% cell culture infectious doses (CCID50) or culture medium was added to either the infected or mock-infected wells of the microtiter tray. Mock-infected cells were used to evaluate the effects of the test compound on uninfected cells in order to assess the cytotoxicity of the test compounds. Exponentially growing MT-4 cells were centrifuged for 5 min at 1,000 rpm, and the supernatant was discarded. The MT-4 cells were resuspended at 6 × 105 cells/ml, and 50-μl volumes were transferred into the microtiter tray wells. Five days after infection, the viability of mock- and HIV-infected cells was examined spectrophotometrically by using the MTT assay. The MTT assay is based on the reduction of yellow MTT (Acros Organics, Geel, Belgium) by the mitochondrial dehydrogenase of metabolically active cells to a blue-purple formazan that can be measured spectrophotometrically. The absorbances were read in an eight-channel computer-controlled photometer (Multiscan Ascent reader; Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland) at two wavelengths (540 and 690 nm). All data were calculated by using the median optical density (OD) value of three wells. The 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) was defined as the concentration of the test compound that reduced the absorbance (OD at 540 nm [OD540]) of the mock-infected control sample by 50%. The concentration achieving 50% protection against the cytopathic effect of the virus in infected cells was defined as the 50% effective concentration (EC50).

Evaluation of the antiviral activity of the compounds against NL4-3.GFP11 in C8166 cells was performed by using flow cytometry (see below), and HIV-1 core antigen (p24 antigen [Ag]) in the supernatant was analyzed by a p24 Ag enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Perkin-Elmer).

Flow cytometry.

Flow cytometric analysis was performed with a FACSCanto II flow cytometry system (Becton Dickinson, Erembodegem, Belgium) equipped with a 488-nm argon-ion laser and a 530-nm/30-nm-bandpass filter (FL1, detection of GFP-associated fluorescence) (Becton Dickinson). Before acquisition, cells were pelleted at 1,000 rpm for 10 min and fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde solution. Acquisition was stopped when 10,000 events were counted. Data analysis was carried out with Cell Quest software (BD Biosciences). Cell debris were excluded from the analysis by gating on forward- versus side-scatter dot plots.

Time-of-addition experiments.

MT-4 cells were infected with HIV-1IIIB at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.5. Following a 1-h adsorption period, cells were distributed into a 96-well tray at 45,000 cells/well and incubated at 37°C. Test compounds were added at different times (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 24, and 25 h) after infection. HIV-1 production was determined at 31 h postinfection via a p24 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Perkin-Elmer, Brussels, Belgium).

Zinc chelation monitored by NPG fluorescence.

The zinc chelation assay buffer consisted of 20 mM HEPES and 10 μM ZnCl2 (pH 7.4). Zinc chelation was monitored by monitoring the decrease in the fluorescence of a zinc-selective fluorophore, Newport Green (NPG) (Molecular Probes), in the assay buffer at room temperature. Zinc chelation was initiated by the addition of different concentrations of test compounds in dimethyl sulfoxide to the zinc chelation assay buffer and incubation for 20 min at room temperature. An equal volume of 1 μM NPG in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) was then added, and the increase fluorescence was monitored at 530 nm (excitation wavelength = 485 nm) by using the Saffire2 fluorescence reader (Tecan).

Zinc ejection and inhibition of NC(11-55) destabilization of cTAR (complementary DNA sequence of TAR).

The NC(11-55) peptide was synthesized by solid-phase peptide synthesis on a 433A synthesizer (ABI, Foster City, CA) as previously described (34). The lyophilized peptide was dissolved in water, and its concentration was determined by using an extinction coefficient of 5,700 M−1·cm−1 at 280 nm. Next, 2.5 molar equivalents of ZnSO4 were added to the peptide, and the pH was raised to its final value by adding buffer. The increase of pH was done only after the addition of zinc to avoid the oxidization of the zinc-free peptide.

Doubly labeled cTAR was synthesized at a 0.2 μmol scale by IBA GmbH Nucleic Acids Product Supply (Göttingen, Germany). The 5′ terminus of cTAR was labeled with 6-carboxyrhodamine (Rh6G) via an amino linker with a six-carbon spacer arm. The 3′ terminus of cTAR was labeled with 4-(4′-dimethylaminophenylazo)benzoic acid (Dabcyl) using a special solid support with the dye already attached. Doubly labeled cTAR was purified by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. An extinction coefficient at 260 nm of 521,910 M−1·cm−1 was used for cTAR. All experiments were performed at 20°C with a solution containing 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 30 mM NaCl, and 0.2 mM MgCl2 (8). Absorption spectra were recorded with a Cary 400 spectrophotometer. Fluorescence spectra were recorded at 20°C with a Fluorolog spectrofluorometer (Horiba Jobin-Yvon) equipped with a thermostated cell compartment. Excitation wavelengths were 295 nm and 520 nm for NC(11-55) and Rh6G-5′-cTAR-3′-Dabcyl, respectively. The spectra were corrected for dilution and buffer fluorescence. The protein spectra were additionally corrected for screening effects due to the zinc-ejecting agent with the following equation:

|

where Im is the measured fluorescence of the protein, Ip is the fluorescence intensity of the protein in the absence of inner filter, dp is the absorbance of the protein, ds is the absorbance of NV038 at the excitation wavelength, and dr is the absorbance of NV038 at the emission wavelengths.

RESULTS

Inhibition of HIV and SIV in cell culture.

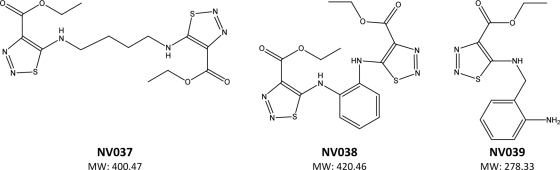

We have discovered an N,N′-bis(4-ethoxycarbonyl-1,2,3-thiadiazol-5-yl)benzene-1,2-diamine (NV038) with anti-HIV and anti-SIV activities in cell culture (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The inhibition of viral replication was monitored by measuring the viability of MT-4 cells 5 days after infection (27). The cytotoxicity of the compound was assessed in parallel by monitoring the viability of mock-infected cells. Interestingly, NV038 was equally active against HIV-1IIIB, HIV-2ROD, and SIVMac251, while compounds lacking the benzenediamine moiety (NV037) or carrying only one 4-ethoxycarbonyl-1,2,3-thiadiazyle substitution (NV039) were completely inactive. The well-characterized nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) nevirapine did not inhibit the replication of HIV-2 or SIV at concentrations of up to 7.5 μM tested. The 50% cytotoxic concentration of NV038 was greater than 297.5 μM tested, resulting in a selective range value of more than 17.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structures of tested compounds. MW, molecular weight (in thousands).

TABLE 1.

Antiviral effect of N,N′-bis(4-ethoxycarbonyl-1,2,3-thiadiazol-5-yl)benzene-1,2-diamine and analoguesa

| Compound | Mean EC50 ± SEM (μM) |

Mean CC50 ± SEM (μM) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1IIIB | NL4.3/WT | NL4.3/DS5000R (165-fold) | NL4.3/AMD3100R (>100-fold) | NNRTIRK103N:Y181C (>85-fold) | HIV-2ROD | SIVMac251 | ||

| NV037 | >105 | ND | ND | ND | ND | >105 | ND | 105 ± 20 |

| NV038 | 17 ± 3 | 15 ± 4.0 | 10 ± 5 | 8 ± 3 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 26 ± 7 | 17 ± 4 | >297.5 |

| NV039 | >290 | ND | ND | ND | ND | >290 | ND | >290 |

Values are from at least 3 independent experiments. The fold resistance toward the respective inhibitor of resistant strains is given in parentheses (with the EC50 for the NL4.3 wild type [WT] set as 1). EC50, 50% effective concentration (concentration of inhibitor required for 50% inhibition of viral replication); CC50, 50% cytotoxic concentration (concentration of inhibitor that kills 50% of the cells); ND, not determined.

To assess the potential of NV038 against drug-resistant HIV-1 strains, its antiviral activity was tested against strains that are resistant to either the entry antagonist dextran sulfate, the CXCR4 inhibitor AMD3100, or the NNRTI nevirapine. NV038 retained its activity against these strains (Table 1), whereas dextran sulfate, AMD3100, and nevirapine were inactive against their respective resistant HIV-1 mutants. These results provide evidences that NV038 does not interfere with virus-cell (coreceptor) binding or the catalytic reverse transcription activity of viral replication and prompted us to carry out a more detailed study of the NV038 mechanism of action.

Mechanism-of-action studies: determination of the step in the virus life cycle affected by the action of NV038.

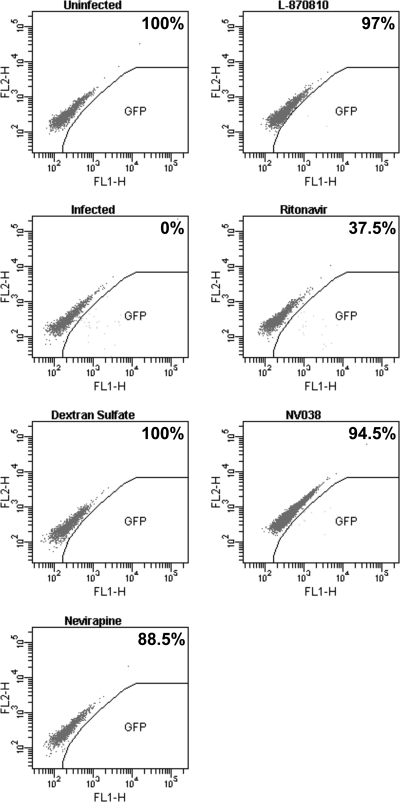

In the NL4-3.GFP11 molecular clone (36), enhanced GFP (eGFP) is expressed from multiply spliced nef mRNAs. Therefore, eGFP expression from this recombinant clone enabled us to determine whether an inhibitor interferes with a target before or after the expression of multiply spliced mRNA (12, 12a). To study the effect of NV038 during a single round of infection, C8166 cells were infected with NL4-3.GFP11 in the presence of inhibitors. Cells were harvested 24 h after infection (time required for a single round of replication), and the number of eGFP-expressing cells was monitored by flow cytometry (Fig. 2). The toxicity of the compounds was assessed from the forward- versus side-scatter dot plots. As expected, the well-characterized HIV inhibitors dextran sulfate and nevirapine and the integrase inhibitor L-870,810 caused a dramatic decrease in numbers of eGFP-expressing cells compared to the untreated control. In contrast, in cultures treated with the HIV-1 protease inhibitor ritonavir, the number of eGFP-expressing cells was similar to that for the untreated control. These results are consistent with the fact that in a single round of infection, molecules interfering with a viral component implicated in the early steps of virus replication inhibit the expression of eGFP, while molecules targeting a viral component essential for virus assembly do not inhibit eGFP expression. NV038 behaved like dextran sulfate, nevirapine, and L-870,810 in that it inhibited the expression of eGFP (by 94.5% compared to the control), thus targeting a viral component playing a key role during the early steps of virus replication.

FIG. 2.

NV038 targets a pretranscriptional step of the HIV-1 life cycle. Cells were infected with NL4-3.GFP11 in the presence of the test compound, and 24 h after infection, cells were analyzed for GFP expression as a marker for infection. The amount of GFP-expressing cells (gated as indicated) were quantified by flow cytometry analysis, and the percentage of inhibition of GFP-expressing cells compared to that of the untreated control (0%) is given in the upper right corner of each plot. Concentrations used were as follows: dextran sulfate, 20 μM; nevirapine, 7.5 μM; L-870,810, 0.3 μM; ritonavir, 2.8 μM; NV038, 297.5 μM.

The above-described results were confirmed when NV038 was evaluated for its inhibitory effect on virus production by chronically HIV-1-infected HuT-78 cells (data not shown). We noticed no inhibitory effect on the release of infectious virus at subtoxic concentrations, while, as expected, the control compound ritonavir, targeting the viral protease, efficiently inhibited the production of infectious viruses. Taken together, such data suggest that the compound NV038 targets an early viral function.

Time of drug addition.

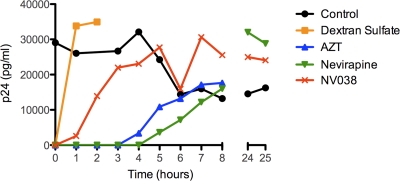

To identify the viral component targeted by this compound, a time-of-addition experiment was set up. This experiment determines how long the addition of a compound can be postponed before its antiviral activity is lost. Indeed, when an inhibitor that interferes with the binding of the virus to the host cell is present at the time of virus addition, it will inhibit virus replication. However, when this binding inhibitor is added after virus delivery to the host cell, it will not interfere with replication. To that end, cells were infected at a high multiplicity of infection, and either one of the compounds was added at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 h after infection, as indicated in Fig. 3. Virus replication was monitored by p24 capsid expression at 31 h after infection. Depending on the drug target, the addition of the compound could be delayed for hours specifically for each compound without losing its antiviral activity. Dextran sulfate, which interacts with virus adsorption to the cell, should be added together with the virus (at 0 h) to be active; its addition at 1 h postinfection or later did not block viral replication because adsorption had already occurred at this time. For zidovudine (AZT) and nevirapine, their addition could be delayed for 3 and 4 h postinfection, respectively. The addition of NV038 could be postponed for only 1 h, favoring the notion that it targets the incoming core or the early reverse transcription complex (RTC).

FIG. 3.

Time-of-addition experiment. MT-4 cells were infected with HIV-1, and the test compounds were added at different time points after infection. Virus production was determined by p24 Ag production in the supernatant at 31 h postinfection. Circles, control; squares, dextran sulfate (20 μM); triangles, AZT (1.9 μM); inverted triangles, nevirapine (7.5 μM); crosses, NV038 (297.5 μM). This graph is representative of data for 2 independent experiments.

NV038 did not interfere with the virus entry process as measured with a classical virus-binding assay (data not shown). The compound also retained full antiretroviral activity against VSV-G-pseudotyped HIV-1 replication (data not shown), confirming that it is not interfering with the specific binding or fusion processes of HIV-1.

N,N′-Bis(4-ethoxycarbonyl-1,2,3-thiadiazol-5-yl)benzene-1,2-diamine targets one of the Gag proteins.

The above-described data suggest that this new compound interacts with one or more essential viral components soon after virus entry into cells. In that respect, NCp7 is a likely candidate since it plays a critical role in the viral core structure and in DNA synthesis and maintenance, notably by chaperoning the RT enzyme during the obligatory minus- and plus-strand DNA transfers to generate long terminal repeats (LTRs) (13, 21).

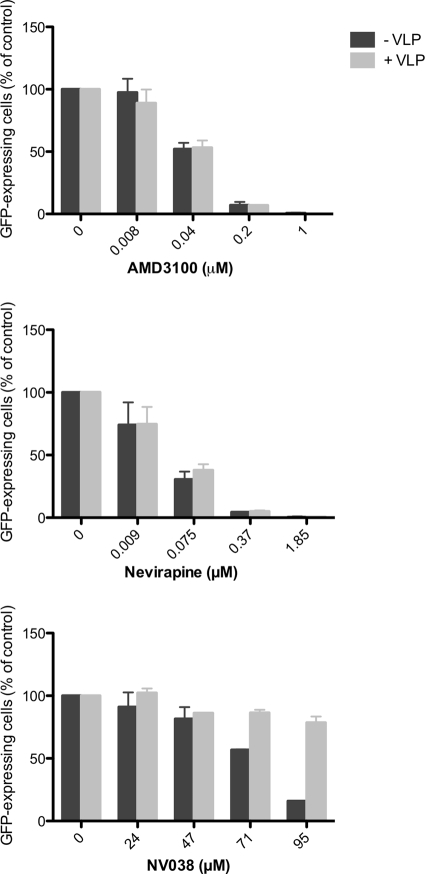

To test whether the anti-HIV-1 activity of NV038 is targeting one of the Gag proteins (including NCp7), we examined whether the anti-HIV-1 effect of NV038 could be suppressed by saturating target cells with HIV-1 virus-like particles (VLPs) containing Gag and pseudotyped with VSV-G. The anti-HIV-1 activity of NV038 decreased in the presence of VLPs, while VLPs had no effect on AMD3100 or on nevirapine (Fig. 4). These results indicate that the inhibitory effect exhibited by NV038 is saturable and is caused by an interaction with one or more of the Gag structural proteins.

FIG. 4.

NV038 inhibition of HIV-1 NL4-3.GFP11 replication is decreased in the presence of VLPs expressing the Gag p55 polyprotein. Human T-lymphocyte C8166 cells were infected with GFP-encoding HIV-1 in the presence or absence of Gag p55-containing VLPs as indicated. Viral replication in the presence of different concentrations of compound was measured by virus-dependent GFP expression using flow cytometry.

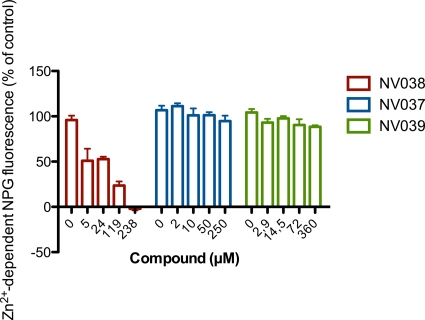

NCp7, which is one of the Gag proteins, contains two CCHC zinc fingers required for the specific recognition of genomic RNA and viral DNA synthesis (reviewed in reference 13). Using Newport Green (NPG) as a specific zinc indicator, we have found that N,N′-bis(4-ethoxycarbonyl-1,2,3-thiadiazol-5-yl)benzene-1,2-diamine is able to efficiently chelate zinc (Fig. 5). The assay is based on the increase in Newport Green fluorescence intensity upon binding Zn2+. In this experiment, NV038 was incubated with 10 μM ZnCl2 for 30 min, and free Zn2+ was then quantified by using Newport Green. Figure 5 shows the decrease of Zn2+-dependent Newport Green fluorescence in the presence of NV038, suggesting that NV038 is chelating Zn2+ ions. NV037 and NV039 had no effect on Newport Green fluorescence in the presence of Zn2+. Altogether, these experiments provide strong evidence that NV038 is interfering with an early step in viral replication by targeting HIV-1 NCp7 function and chelating the Zn2+ ions from the zinc fingers.

FIG. 5.

Zn2+-dependent Newport Green (NPG) fluorescence in the presence of N,N′-bis(1,2,3-thiadiazol-5-yl)benzene-1,2-diamine derivatives. Zinc chelation of the compounds was monitored by measuring the decrease in the fluorescence of the zinc-selective fluorophore Newport Green.

Zinc ejection and inhibition of NCp7(11-55) destabilization of cTAR.

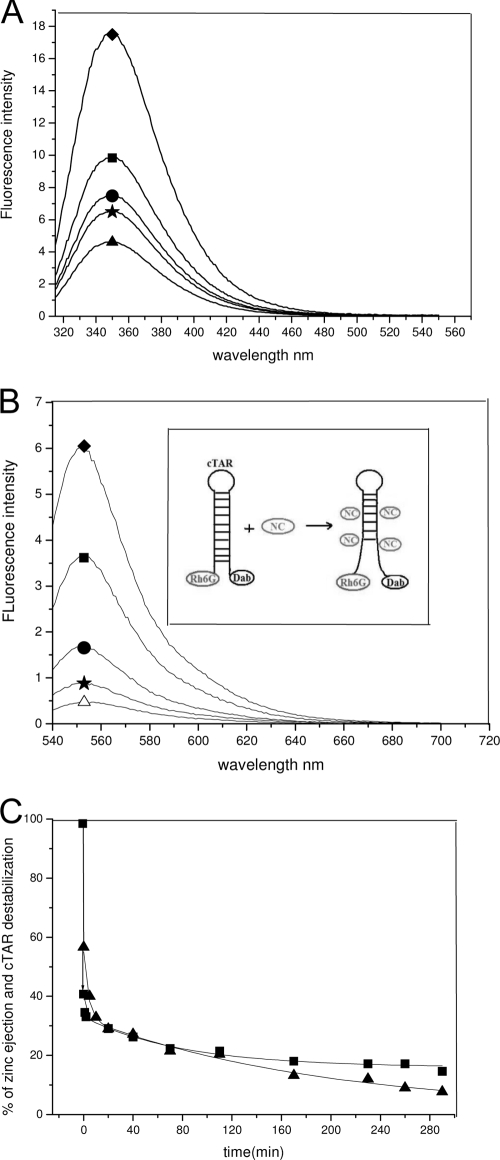

Zinc ejection from the NCp7 zinc finger by NV038 was monitored through the intrinsic fluorescence of residue Trp37 of NC(11-55). This residue belongs to the distal zinc finger motif and shows a 3.0-fold increase of its fluorescence quantum yield upon zinc binding (9, 24). The addition of a 10-fold excess of NV038 was found to induce a rapid decrease of Trp37 fluorescence (Fig. 6A), suggesting that NV038 efficiently removes zinc from NC(11-55). After 3 h, the fluorescence dropped to a level close to that observed in the presence of 1 mM EDTA, indicating a nearly full ejection of zinc.

FIG. 6.

Zn ejection and inhibition of NC(11-55)-promoted cTAR destabilization by NV038. (A) Ejection of the zinc ions bound to NC(11-55) by NV038. The emission spectrum of 1 μM NCp7 was recorded either in the absence (diamond) or in the presence of 4.2 μg/ml (10 μM) NV038 after 1 min (square), 1 h (circle), and 3 h (star) of incubation. Triangle, emission spectrum of NC(11-55) after the addition of 1 mM EDTA. (B) Inhibition of NC(11-55)-induced cTAR destabilization by NV038. The emission spectrum of 0.1 μM Rh6G-5′-cTAR-3′-Dabcyl was recorded either in the absence (open triangle) or in the presence of 1 μM NC(11-55) before (diamond) and after incubation with 10 μM of the NV038 compound for 1 min (square), 1 h (circle), and 3 h (star). (Inset) Scheme of the NC(11-55)-induced destabilization of cTAR and the resulting fluorescence increase of Rh6G. (C) Correlation between zinc ejection and inhibition of NC(11-55)-promoted cTAR destabilization. The percentages of Zn2+ ejection (squares) and inhibition of cTAR destabilization (triangles) induced by 10 μM NV038 are reported as a function of time. Solid lines represent double-exponential fits to the data.

To confirm the zinc ejection, we then monitored, in the presence of NV038, the NC(11-55)-induced destabilization of the secondary structure of cTAR DNA (Fig. 6B, inset), the complementary sequence of the transactivation response element, involved in minus-strand DNA transfer during reverse transcription (3, 5, 8). Indeed, this destabilization is exquisitely sensitive to the proper folding of the zinc-bound finger motifs and totally disappears when zinc ions are removed (6). Sensitive monitoring of the NCp7-induced destabilization of cTAR can be obtained by using the doubly labeled Rh6G-5′-cTAR-3′-Dabcyl derivative. In the absence of NC, cTAR is mainly in a nonfluorescent closed form, where the Rh6G and Dabcyl labels at the 5′ and 3′ termini, respectively, of the cTAR stem are close together, giving excitonic coupling (7). As previously reported (8), NC(11-55) added to cTAR at a 10-fold molar excess led to a melting of the bottom of the cTAR stem, which increases the distance between the two fluorophores and thus restores Rh6G fluorescence (Fig. 6B). In line with the zinc ejection hypothesis, the addition of NV038 to the NC(11-55)/cTAR complex at a molar ratio of 10:1 with respect to NC(11-55) led to a strong decrease in Rh6G emission and, thus, in cTAR destabilization. The NC(11-55)-induced destabilization of cTAR further decreased with time, and the peptide became almost fully inactive after 3 h of incubation with NV038. Moreover, the loss of the ability of NC(11-55) to destabilize cTAR was found to closely match the ejection of zinc from the fingers (Fig. 6C), further confirming that NV038 efficiently removes bound zinc ions from NCp7.

DISCUSSION

We have identified N,N′-bis(4-ethoxycarbonyl-1,2,3-thiadiazol-5-yl)benzene-1,2-diamine (NV038), a new lead compound that efficiently interferes with the replication of HIV-1, HIV-2, and SIV and resistant HIV-1 strains. The compound was tested with different acute and chronic HIV infection models in order to establish its time of effect and mode of action. Its effectiveness in inhibiting HIV replication in acute infection models as opposed to its inability to block virus production from chronically infected cells indicates that the target of NV038 encompasses a preintegrational process. Furthermore, time-of-addition experiments even refined the time of intervention to a time frame situated after entry and prior to the completion of the reverse transcription step, indicating that NV038 targets the incoming core complex. However, compared to the efficiency of AZT or nevirapine, its current EC50 does not predict sufficient potency for good efficacy in clinical studies. Indeed, in comparison to these extremely potent inhibitors, the antiretroviral activity of NV038 is almost insignificant. However, one of the keystones of actual anti-HIV treatment, namely, the phosphonate acyclic nucleotide analogue (R)-PMPA (tenofovir), has a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 7 μM when assessed with the same biological system. This is only about half the value observed for NV038. Nevertheless, its potency might be increased by chemical modification. By using molecular modeling, a rational design of new analogues that will enable an improvement of activity and selectivity is planned.

As NCp7 is one of the possible targets occurring after entry and prior to the completion of the RT step, the effect of loading infected cells with an excess of Gag p55 on the inhibitory activity of NV038 was tested. The observed loss of the anti-HIV-1-inhibitory effect of NV038 in the presence of Gag p55-containing VLPs suggested a stoichiometric interaction of the compound with a protein derived from Gag p55. In vitro, we demonstrated that NV038 is able to chelate zinc ions. Interestingly, the zinc chelation ability of NV038 and its analogues correlates well with their inhibitory capacity on retroviral replication. Indeed, the compound NV038 is able to chelate zinc and inhibit HIV replication, while the related compounds NV037 (having a 1,3-proylenediamine linker instead of the 1,2-benzenediamine linker) and NV039 (having only one 4-ethoxycarbonyl-1,2,3-thiadiazol-5-yl moiety) did not inhibit HIV in vitro, nor did they chelate zinc. We also demonstrated that NV038 efficiently ejects zinc from NCp7. Noticeably, our data (Fig. 6A) indicate that the distal finger motif releases zinc in the presence of NV038. Moreover, the loss of the ability of NCp7 to destabilize cTAR was correlated with the ejection of zinc from the fingers, further confirming that NV038 efficiently removes the bound zinc ions from NCp7. Altogether, these experiments unambiguously pinpoint NCp7 as the target for this new lead compound.

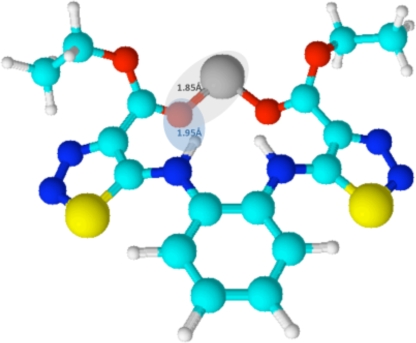

It was reported previously that compounds with zinc ejection properties can inhibit a postintegration stage of HIV-1 replication (31). However, the N,N′-bis(4-ethoxycarbonyl-1,2,3-thiadiazol-5-yl)benzene-1,2-diamine described here clearly interferes with an early step happening after viral entry and before reverse transcription. Other compounds with zinc-ejecting properties were previously shown to inhibit an early step of the HIV-1 life cycle (14). Furthermore, the reported zinc-ejecting compounds that are interfering with HIV-1 replication, whether they act on an early or a late stage of the viral life cycle, have been shown to target one of the functions of the nucleocapsid (NCp7) protein. Indeed, retroviral nucleocapsid proteins harbor a multiplicity of functions, including viral RNA binding and packaging (1, 40), virus infectivity (15, 18), reverse transcription promotion (16, 19, 22, 26), and the stimulation of retroviral integration (10). Since these processes are happening in both early and late stages of the viral life cycle, different inhibitors targeting different functions of NCp7 could have an early or a late effect on HIV-1 replication. Further molecular analysis of how these different classes of NCp7 inhibitors act and how they structurally interact with NCp7 could be useful to draw the different functional regions within NCp7 responsible for early and late functions. At least for the thioester zinc ejectors, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and mass spectroscopy studies showed that they act by the covalent modification of Cys39 (20). Also, for DIBA compounds, the proposed reaction mechanism is a thiol-disulfide interchange between DIBA and NCp7 at Cys36 and Cys49 (23). We speculate that the N,N′-bis(1,2,3-thiadiazol-5-yl)benzene-1,2-diamine described here acts via a different mechanism, as its structural features do not allow an acyl transfer to Cys or a thiol-disulfide interchange. Future research, such as structure-activity relationship experiments, is needed to confirm this hypothesis. However, the limited series of compounds reported here already indicates that the anti-HIV activity is linked to the Zn2+-chelating capacity of the compound. It is likely that the conformation adopted by NV038 is determined by the chelation of the Zn2+ ion by the two carbonyl oxygens of the esters and furthermore by a hydrogen bond between the NH and the carbonyl of the esters. This model is depicted in Fig. 7 and is in agreement with the typical bond lengths for a Zn-oxygen complex (≈1.85 Å) and the interatomic distance for N-H…O (≈1.95 Å). The selectivity of the compound reveals a possible specific chelation of zinc at the zinc fingers. This implies that NV038 harbors structural features that direct the molecule to the zinc fingers of NCp7. In an ongoing effort to study the structural requirements for Zn2+ chelation at the zinc fingers, a series of molecules that will shed light on the structure-activity relationship is now being synthesized.

FIG. 7.

Chemical model for chelation of Zn2+ by the two carbonyl oxygens of the esters from NV038. Bond lengths for a Zn-oxygen complex (1.85 Å) and the interatomic distance for N-H…O (1.95 Å) are given. This figure was created by using ACD/Chemsketch 12.0 software. Red, oxygen; dark blue, nitrogen; yellow, sulfur; gray, zinc; green, carbon; white, hydrogen.

In conclusion, we present a new lead compound inhibiting HIV-1, HIV-2, as well as SIV retroviruses. Data from mechanism-of-action studies indicate that this compound targets an early-stage function of the nucleocapsid protein and chelates Zn2+ from the NCp7 zinc fingers. This lead compound and the study of its mechanism of action are useful for the development of a future generation of NCp7 inhibitors with improved activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Bral, L. De Dier, K. Erven, C. Heens, and K. Uyttersprot for excellent technical assistance; G. Pavlakis and B. Felber for plasmids; and J.-L. Darlix for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript. A number of reagents were obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program.

The work was supported by grant number 1.5.104.07 from the Belgian Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (FWO), a Geconcerteerde Onderzoeksacties grant (grant number GOA 10/014) to the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, the French ANRS (Agence Nationale de la Recherche sur le SIDA), and the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (grant numbers RFBR 08-03-00376 a and RFBR/NNSF 08-03-92208 a).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 February 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aldovini, A., and R. A. Young.1990. Mutations of RNA and protein sequences involved in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 packaging result in production of noninfectious virus. J. Virol. 64:1920-1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Mawsawi, L. Q., and N. Neamati.2007. Blocking interactions between HIV-1 integrase and cellular cofactors: an emerging anti-retroviral strategy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 28:526-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azoulay, J., J. P. Clamme, J. L. Darlix, B. P. Roques, and Y. Mely.2003. Destabilization of the HIV-1 complementary sequence of TAR by the nucleocapsid protein through activation of conformational fluctuations. J. Mol. Biol. 326:691-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balvay, L., M. Lopez Lastra, B. Sargueil, J. L. Darlix, and T. Ohlmann.2007. Translational control of retroviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:128-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beltz, H., J. Azoulay, S. Bernacchi, J. P. Clamme, D. Ficheux, B. Roques, J. L. Darlix, and Y. Mely.2003. Impact of the terminal bulges of HIV-1 cTAR DNA on its stability and the destabilizing activity of the nucleocapsid protein NCp7. J. Mol. Biol. 328:95-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beltz, H., C. Clauss, E. Piemont, D. Ficheux, R. J. Gorelick, B. Roques, C. Gabus, J. L. Darlix, H. de Rocquigny, and Y. Mely.2005. Structural determinants of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein for cTAR DNA binding and destabilization, and correlation with inhibition of self-primed DNA synthesis. J. Mol. Biol. 348:1113-1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernacchi, S., and Y. Mely.2001. Exciton interaction in molecular beacons: a sensitive sensor for short range modifications of the nucleic acid structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:E62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernacchi, S., S. Stoylov, E. Piemont, D. Ficheux, B. P. Roques, J. L. Darlix, and Y. Mely.2002. HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein activates transient melting of least stable parts of the secondary structure of TAR and its complementary sequence. J. Mol. Biol. 317:385-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bombarda, E., N. Morellet, H. Cherradi, B. Spiess, S. Bouaziz, E. Grell, B. P. Roques, and Y. Mely.2001. Determination of the pK(a) of the four Zn2+-coordinating residues of the distal finger motif of the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein: consequences on the binding of Zn2+. J. Mol. Biol. 310:659-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carteau, S., R. J. Gorelick, and F. D. Bushman.1999. Coupled integration of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cDNA ends by purified integrase in vitro: stimulation by the viral nucleocapsid protein. J. Virol. 73:6670-6679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clapham, P. R., and A. McKnight.2002. Cell surface receptors, virus entry and tropism of primate lentiviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 83:1809-1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daelemans, D., C. Pannecouque, G. N. Pavlakis, O. Tabarrini, and E. De Clercq.2005. A novel and efficient approach to discriminate between pre- and post-transcription HIV inhibitors. Mol. Pharmacol. 67:1574-1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12a.Daelemans, D., E. De Clercq, and A. M. Vandamme.2001. A quantitative GFP-based bioassay for the detection of HIV-1 Tat transactivation inhibitors. J. Virol. Methods 96:183-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darlix, J. L., J. L. Garrido, N. Morellet, Y. Mely, and H. de Rocquigny.2007. Properties, functions, and drug targeting of the multifunctional nucleocapsid protein of the human immunodeficiency virus. Adv. Pharmacol. 55:299-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Rocquigny, H., V. Shvadchak, S. Avilov, C. Z. Dong, U. Dietrich, J. L. Darlix, and Y. Mely.2008. Targeting the viral nucleocapsid protein in anti-HIV-1 therapy. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 8:24-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorfman, T., J. Luban, S. P. Goff, W. A. Haseltine, and H. G. Gottlinger.1993. Mapping of functionally important residues of a cysteine-histidine box in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein. J. Virol. 67:6159-6169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Driscoll, M. D., and S. H. Hughes.2000. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein can prevent self-priming of minus-strand strong stop DNA by promoting the annealing of short oligonucleotides to hairpin sequences. J. Virol. 74:8785-8792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorelick, R. J., W. Fu, T. D. Gagliardi, W. J. Bosche, A. Rein, L. E. Henderson, and L. O. Arthur.1999. Characterization of the block in replication of nucleocapsid protein zinc finger mutants from Moloney murine leukemia virus. J. Virol. 73:8185-8195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorelick, R. J., S. M. Nigida, Jr., J. W. Bess, Jr., L. O. Arthur, L. E. Henderson, and A. Rein.1990. Noninfectious human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mutants deficient in genomic RNA. J. Virol. 64:3207-3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo, J., T. Wu, J. Anderson, B. F. Kane, D. G. Johnson, R. J. Gorelick, L. E. Henderson, and J. G. Levin.2000. Zinc finger structures in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein facilitate efficient minus- and plus-strand transfer. J. Virol. 74:8980-8988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenkins, L. M., J. C. Byrd, T. Hara, P. Srivastava, S. J. Mazur, S. J. Stahl, J. K. Inman, E. Appella, J. G. Omichinski, and P. Legault.2005. Studies on the mechanism of inactivation of the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein NCp7 with 2-mercaptobenzamide thioesters. J. Med. Chem. 48:2847-2858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levin, J. G., J. Guo, I. Rouzina, and K. Musier-Forsyth.2005. Nucleic acid chaperone activity of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein: critical role in reverse transcription and molecular mechanism. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 80:217-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li, X., Y. Quan, E. J. Arts, Z. Li, B. D. Preston, H. de Rocquigny, B. P. Roques, J. L. Darlix, L. Kleiman, M. A. Parniak, and M. A. Wainberg.1996. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein (NCp7) directs specific initiation of minus-strand DNA synthesis primed by human tRNA(Lys3) in vitro: studies of viral RNA molecules mutated in regions that flank the primer binding site. J. Virol. 70:4996-5004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loo, J. A., T. P. Holler, J. Sanchez, R. Gogliotti, L. Maloney, and M. D. Reily.1996. Biophysical characterization of zinc ejection from HIV nucleocapsid protein by anti-HIV 2,2′-dithiobis[benzamides] and benzisothiazolones. J. Med. Chem. 39:4313-4320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mely, Y., H. De Rocquigny, N. Morellet, B. P. Roques, and D. Gerad.1996. Zinc binding to the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein: a thermodynamic investigation by fluorescence spectroscopy. Biochemistry 35:5175-5182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nathans, R., H. Cao, N. Sharova, A. Ali, M. Sharkey, R. Stranska, M. Stevenson, and T. M. Rana.2008. Small-molecule inhibition of HIV-1 Vif. Nat. Biotechnol. 26:1187-1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ottmann, M., C. Gabus, and J. L. Darlix.1995. The central globular domain of the nucleocapsid protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is critical for virion structure and infectivity. J. Virol. 69:1778-1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pannecouque, C., D. Daelemans, and E. De Clercq.2008. Tetrazolium-based colorimetric assay for the detection of HIV replication inhibitors: revisited 20 years later. Nat. Protoc. 3:427-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ren, J., and D. K. Stammers.2005. HIV reverse transcriptase structures: designing new inhibitors and understanding mechanisms of drug resistance. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 26:4-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rice, W. G., D. C. Baker, C. A. Schaeffer, L. Graham, M. Bu, S. Terpening, D. Clanton, R. Schultz, J. P. Bader, R. W. Buckheit, Jr., L. Field, P. K. Singh, and J. A. Turpin.1997. Inhibition of multiple phases of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by a dithiane compound that attacks the conserved zinc fingers of retroviral nucleocapsid proteins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:419-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rice, W. G., C. A. Schaeffer, B. Harten, F. Villinger, T. L. South, M. F. Summers, L. E. Henderson, J. W. Bess, Jr., L. O. Arthur, J. S. McDougal, et al.1993. Inhibition of HIV-1 infectivity by zinc-ejecting aromatic C-nitroso compounds. Nature 361:473-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rice, W. G., J. G. Supko, L. Malspeis, R. W. Buckheit, Jr., D. Clanton, M. Bu, L. Graham, C. A. Schaeffer, J. A. Turpin, J. Domagala, R. Gogliotti, J. P. Bader, S. M. Halliday, L. Coren, R. C. Sowder II, L. O. Arthur, and L. E. Henderson.1995. Inhibitors of HIV nucleocapsid protein zinc fingers as candidates for the treatment of AIDS. Science 270:1194-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rice, W. G., J. A. Turpin, M. Huang, D. Clanton, R. W. Buckheit, Jr., D. G. Covell, A. Wallqvist, N. B. McDonnell, R. N. DeGuzman, M. F. Summers, L. Zalkow, J. P. Bader, R. D. Haugwitz, and E. A. Sausville.1997. Azodicarbonamide inhibits HIV-1 replication by targeting the nucleocapsid protein. Nat. Med. 3:341-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneider, R., M. Campbell, G. Nasioulas, B. K. Felber, and G. N. Pavlakis.1997. Inactivation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 inhibitory elements allows Rev-independent expression of Gag and Gag/protease and particle formation. J. Virol. 71:4892-4903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shvadchak, V., S. Sanglier, S. Rocle, P. Villa, J. Haiech, M. Hibert, A. Van Dorsselaer, Y. Mely, and H. de Rocquigny.2009. Identification by high throughput screening of small compounds inhibiting the nucleic acid destabilization activity of the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein. Biochimie 91:916-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turpin, J. A., Y. Song, J. K. Inman, M. Huang, A. Wallqvist, A. Maynard, D. G. Covell, W. G. Rice, and E. Appella.1999. Synthesis and biological properties of novel pyridinioalkanoyl thiolesters (PATE) as anti-HIV-1 agents that target the viral nucleocapsid protein zinc fingers. J. Med. Chem. 42:67-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valentin, A., W. Lu, M. Rosati, R. Schneider, J. Albert, A. Karlsson, and G. N. Pavlakis.1998. Dual effect of interleukin 4 on HIV-1 expression: implications for viral phenotypic switch and disease progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:8886-8891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Witvrouw, M., J. Balzarini, C. Pannecouque, S. Jhaumeer-Laulloo, J. A. Este, D. Schols, P. Cherepanov, J. C. Schmit, Z. Debyser, A. M. Vandamme, J. Desmyter, S. R. Ramadas, and E. de Clercq.1997. SRR-SB3, a disulfide-containing macrolide that inhibits a late stage of the replicative cycle of human immunodeficiency virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:262-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiao, Z., E. Ehrlich, K. Luo, Y. Xiong, and X. F. Yu.2007. Zinc chelation inhibits HIV Vif activity and liberates antiviral function of the cytidine deaminase APOBEC3G. FASEB J. 21:217-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang, H., Y. Zhou, C. Alcock, T. Kiefer, D. Monie, J. Siliciano, Q. Li, P. Pham, J. Cofrancesco, D. Persaud, and R. F. Siliciano.2004. Novel single-cell-level phenotypic assay for residual drug susceptibility and reduced replication capacity of drug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 78:1718-1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang, Y., and E. Barklis.1995. Nucleocapsid protein effects on the specificity of retrovirus RNA encapsidation. J. Virol. 69:5716-5722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]