Abstract

ANF-RGC$ membrane guanylate cyclase is the receptor for the hypotensive peptide hormones, atrial natriuretic factor (ANF) and type B natriuretic peptide (BNP). It is a single transmembrane spanning protein. Binding the hormone to the extracellular domain activates its intracellular catalytic domain. This results in accelerated production of cyclic GMP, a second messenger in controlling blood pressure, cardiac vasculature and fluid secretion. ATP is the obligatory transducer of the ANF signal. It works through its ATP regulated module, ARM, which is juxtaposed to the C-terminal side of the transmembrane domain. Upon interaction, ATP induces a cascade of temporal and spatial changes in the ARM, which, finally, result in activation of the catalytic module. Although the exact nature and the details of these changes are not known, some of these have been stereographed in the simulated three-dimensional model of the ARM and validated biochemically. Through comprehensive techniques ofsteady-state, time-resolved tryptophan fluorescence and Forster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), site-directed and deletion-mutagenesis, and reconstitution, the present study validates and explains themechanism of the model-based predicted transduction role of the ARM’s structural motif, 669WTAPELL675. This motif is critical in the ATP-dependent ANF signaling. Molecular modeling shows that ATP binding exposes the 669WTAPELL675 motif, the exposure, in turn, facilitates its interaction and activation of the catalytic module. These principles of the model have been experimentally validated. This knowledge brings us a step closer to our understanding of the mechanism by which the ATP-dependent spatial changes within the ARM cause ANF signaling of ANF-RGC.

Keywords: ANF, ATP, ANF-RGC, membrane guanylate cyclase, cyclic GMP, signal transduction

INTRODUCTION

ANF-RGC is a prototype member of the mammalian membrane guanylate cyclase family. Its discovery was remarkable [1–5, reviewed in: 6]. It established that ANF-RGC besides being an enzyme is also a surface receptor of the peptide hormone, ANF. It demonstrated that the membrane guanylate cyclase transduction mechanism is distinct from the G-protein-coupled receptors and the soluble guanylate cyclases. Importantly, it ceased the intense debate that questioned the independent integrity of its operation in the mammalian systems.

With the discovery of ROS-GC membrane guanylate cyclase that was solely modulated by the intracellular pulsated levels of Ca2+ within the photoreceptors, the membrane guanylate cyclase family branched into two subfamilies, peptide hormone receptor and Ca2+-modulated ROS-GC. Significantly, the family got the recognition of being the transducer of both types of signals, generated outside and inside the cells [reviewed in: 6, 7].

There are three functional members of the peptide hormone receptor guanylate cyclase subfamily. They are ANF-RGC, the receptor of the a trial natriuretic factor [8–10] and the type B natriuretic peptide [11]; CNP-RGC, the receptor of C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) [12–14]; and STa-RGC, the receptor of enterotoxin, guanylin and uroguanylin [15]. These guanylate cyclases have been alternately termed as GC-A [9, 10], GC-B [13, 14], and GC-C [15], respectively. A recent study shows that ONE-GC, a ROS-GC member, also belongs to the peptide hormone receptor subfamily, it is receptor for the urine peptide, uroguanylin [16]. Presently, it is a sole member of the cross-over ROS-GC-hormone peptide receptor subfamily. Thus, this represents the third membrane guanylate cycles subfamily.

All members of the membrane guanylate cyclase family are single transmembrane-spanning proteins, composed of modular blocks [reviewed in: 6]. Their functional forms are all homo-dimeric [17–21]. In each mono-meric subunit, the transmembrane module divides the protein into two roughly equal portions, extracellular and intracellular. The individual modular blocks within each portion provide functional uniqueness to each member of the guanylate cyclase family. Each modular block within the extracellular region of the receptor guanylate cyclases uniquely senses its peptide hormone signal and within the intracellular block of a ROS-GC its Ca2+ signal. The catalytic domain in each membrane guanylate cyclase resides in its intracellular region. However, topographical arrangement of this domain differs in the two sub-families. In the peptide hormone receptor, it is at the C-terminal end and in the ROS-GC it is followed by a C-terminal extension [reviewed in: 7].

Like ANF-RGC, ANF is a proto-type hormone of the natriuretic peptide family [reviewed in: 22–24]. The residential sites of ANF and BNP are in the atrial and ventricular granules of the heart. With each atrial and ventricular stretch, defined doses of these peptides are pulsated into the blood stream and carried to their target tissues where they exhibit their biological activities. Gene-knock out studies link ANF and ANF-RGC with salt-sensitive [25] and salt-in-sensitive hypertension [26]. Thus, ANF and ANF-RGC are critical components of the renal and cardiovascular physiology.

Originally it was shown that ATP facilitates and, subsequently, that it is an obligatory transduction factor in ANF dependent ANF-RGC signaling [27–30; reviewed in: 31]. It functions through two independent mechanisms, direct [27–30, 32, 33, 34] and indirect [33, 35, 36]. In the direct, ATP interacts with a defined intracellular domain of ANF-RGC. In the indirect, through a hypothetical protein kinase it phosphorylates ANF-RGC.

Two recent studies have reinforced the ATP-dependent mode of ANF-RGC signal transduction mechanism [34, 37]. They have refuted a sole claim [35] that this transduction mechanism is ATP-independent, and have pointed out the technical flaws in this study.

Sequential analysis of the ATP-dependent direct mechanism has resulted in defining some of its temporal features, which have been choreographed in a three-dimensional ARM (ATP Regulated Module) model [38, 39; reviewed in: 31]. The model depicts that ARM domain has two distinct structural elements. One is the ATP-binding pocket and second, the transduction region. The binding pocket resides in the smaller, N-terminal lobe of the ARM and the transduction region in the larger, predominantly helical, C-terminal lobe [38, 39, reviewed in; 31; Fig. 1]. The model predicts that ATP binding to the pocket causes a cascade of sequential stereo-specific changes. These changes result in exposure of the 669WTAPELL675 motif; the exposure, in turn, facilitates its direct or indirect activation of the catalytic module [31, 39].

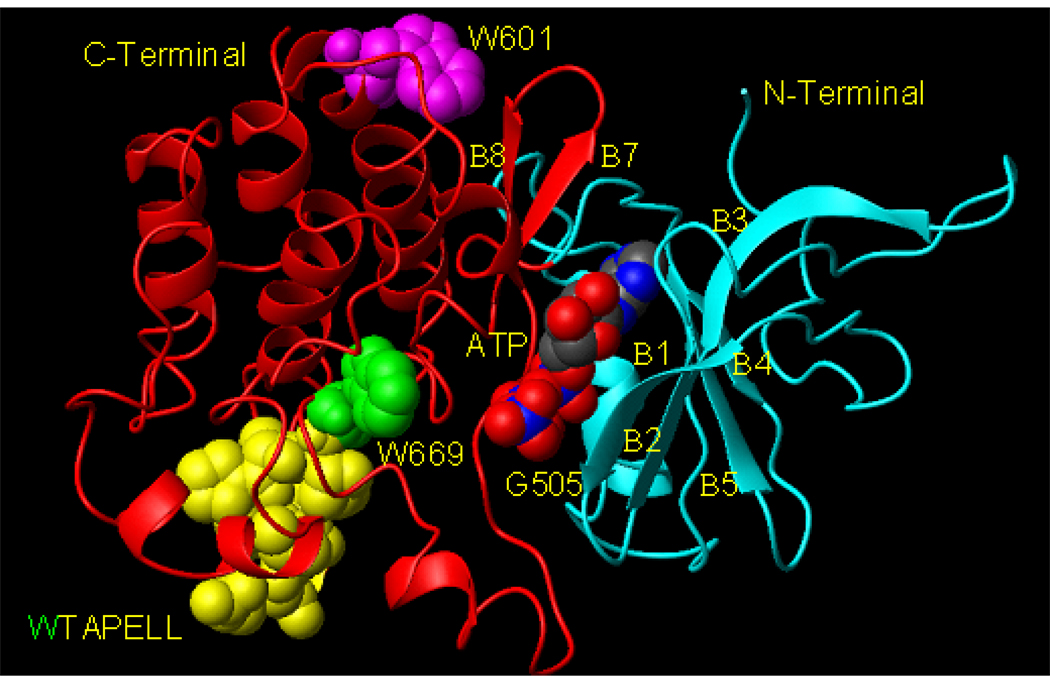

Figure 1. Model of the ARM domain. 3D computer generated ribbon model of the ATP-bound ANF-RGC ARM domain.

ATP is shown in multicolor CPK model. W601 is shown in magenta CPK model, W669 in green, and 670TAPELL675, in yellow. The structure was generated as in (38). For clarity of presentation (position of ATP, W601 and W669), as compared to (31, 38, 39), the model is rotated around×axis. N- and C-terminals, β-sheets (B1, B2, etc) and the G505 are indicated.

To test this hypothesis, in the present study, steady-state and time-resolved fluorescence analyses of two ARM domain’s tryptophan mutants were performed. The fluorescence results were then analyzed in terms of the stereo-specific changes occurring within the ARM domain upon ATP binding using 3-D modeling. These crucial stereo-specific changes were then confirmed by measuring the guanylate cyclase activity of the full-length ANF-RGC’s point and deletion mutants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification of ANF-RGC ARM domain

In an identical fashion to the earlier ARM fragment construct aa 486–661 [34], the present ARM fragment, aa 486–692, was amplified from ANF-RGC cDNA by PCR and directly cloned into the ligation independent site of pET-30aXa/LIC vector (Novagen). The structure of this construct was verified by the sequence analysis. It was transfected into E. coli BL21-Codon-Plus-RIL cells for protein expression. The ARM domain was expressed as a His-tag-fusion protein and purified to homogeneity according to the earlier protocol [34] with some modifications. The same protocol was followed for expression and purification of the ARM-W601A and ARM-W669A mutants.

UV cross-linking

According to the previous protocol [34], 1 µg (50 pmol) of the purified ARM protein in 20 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5 was incubated for 5 min with 100 pmol of 2-azido-ATP and 1 µCi [γ32P]-2-azido-ATP [specific activity 10-15 Ci/mmol (ALT, Inc)], 1 mM MgCl2 in a total volume of 25 µl. The reaction mixture was UV irradiated (254 nm) and analyzed by SDS-15%PAGE followed by autoradiography.

Steady-state tryptophan fluorescence measurements

All steady-state fluorescence experiments were performed using 1 cm × 1 cm quartz cuvettes in a Cary Eclipse fluorometer (Varian) with 5 nm excitation and emission slits unless otherwise specified. Emission spectra were measured from 300 to 450 nm. 2–5 µM ARM protein (wt-ARM, ARM- W601A or ARM-W669A) were dissolved in 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8 buffer containing 1 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol and 0.2% laurosarcosyl and used in steady-state as well as time-resolved fluorescence studies. Spectra were normalized and corrected in some cases for the background. N-acetyl tryptophanamide was used as an external standard. To denature the proteins, they were mixed with buffer containing 6 M guanidine-HCl for 3 min before the measurements. To determine collisional quenching of tryptophan fluorescence, stock solution of 1 M acrylamide was used. The effects of dilution were either negligible or were calibrated in parallel experiments. The quenching data were plotted according to Stern-Volmer equation F0/F= 1+ KD[Q], where F0 and F are the relative fluorescence intensities in the absence and presence of collisional quencher at concentration [Q], and KD is the Stern-Volmer quenching constant.

Time-resolved tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy

Time-domain measurements were performed on a Fluotime 200 fluorometer (Picoquant) equipped with a Hamamatsu microchannel plate (MCP) providing <50 ps resolution. The emission monochromator was set to 332 nm for W601 and to 345 nm for W669, with the emission and excitation slits fully open, and the polarizers set to the magic angle conditions. The excitation source was a 295 nm LED driven at a 10 mHz repetition rate by a PDL800 driver (Picoquant) fitted with a Corning 7–54 short pass filter for wavelengths below 320 nm. The emission side was equipped with a 303 nm long pass filter in front of the monochromator. Time resolved fluorescence data were analyzed using Fluofit software package (Picoquant 4.0). Lifetime data were fit using nonlinear-squares analysis to a sum of n exponentials according to the equation:

where αi is the fractional contribution of each life-time component (τi). When more than one life-time component is indicated, the amplitude-weighted average life-time is reported as:

Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)

Steady-state and time resolved fluorescence measurements were performed as described above except that increasing concentrations of ATP-fluorescent derivative, 2’-0-(N-methylantraniloyl)-adenosine 5’-triphosphate (Mant-ATP) were added to the reaction mixture.

Molecular modeling

Molecular modeling was done on a Silicon Graphics workstation using Sybyl molecular modeling package [SYBYL modeling software (version 6.6) Tripos Associate Inc.] and the figures were generated using Molmol [40]. To optimize the allowed conformations of W601, W669 and other residues in the 669WTAPELL675 motif, systematic conformational search for side chains of these residues along single bonds with an angle increment of 20 degrees was performed. All sterically allowed conformations were analyzed and the one with least energy for each amino acid in the final structure was chosen.

Mutagenesis

Mutations were introduced into the isolated ARM domain and in the full-length ANF-RGC cDNA using Quick Change mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The authenticity of all mutations was verified by sequence analyses.

Expression in COS cells

COS-7 cells were transfected with ANF-RGC cDNA or its mutants using a calcium-phosphate co-precipitation technique [41]. Sixty hours after transfection, the cells were harvested and their membranes prepared as described earlier [34, 38].

Guanylate cyclase activity assay

Membranes were assayed for guanylate cyclase activity in an assay mixture consisting of 10 mM theophylline (phosphodiesterase inhibitor), 15 mM phosphocreatine, 20 µg creatine kinase, 50 mM Tris-HCI, pH 7.5, and 10−7 M ANF and 0–1 mM ATP. The total assay volume was 25 µl. The reaction was initiated by the addition of the substrate solution containing 4 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM GTP, continued for 10 min at 37 °C, and terminated by the addition of 225 µl of 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 6.25) followed by heating in a boiling water-bath for 3 min [34, 38]. The amount of cyclic GMP formed was quantified by radioimmunoassay [42]. All experiments were done in triplicate.

RESULTS

Background

The ARM domain in ANF-RGC is the processing unit of the ATP signal transduction. It stretches between residues 496–771. Its 3D-model predicts that it is composed of two interconnected lobes, the smaller, N-terminal and the larger, C-terminal [38, 39; Fig. 1].

The smaller lobe is the site of ATP-binding. The lobe is arranged in a twisted β-sheet of four anti-parallel strands and one αhelix. The folding organization of 13 residues--L511, T513, K535, T580, C583, S587, C634, V635, D590, K630, S632, and N633, D646 constitutes the ATP binding pocket. The importance of the bold-faced residues in the functional vitality of ARM has been validated by the point mutation/expression studies [38]. A UV cross-linking experiment has further confirmed the role of C634 in ATP binding as evidenced by the direct cross-linking of 8-azido ATP with the bond between C634 and V635 [34].

The ARM model predicts that creation of the ATP-bound pocket causes two sequential changes in the configuration of the smaller lobe [38, 39]. 1) The lobe’s β1 and β2 strands move 3 to 4 Å and rotate by 15° the floor of the ATP binding pocket. (It is recalled that the floor is a separate domain from the ATP-binding pocket domain [38, 39]). Gly505 constitutes the PIVOT for both the movement and rotation. 2) It moves 2 to 7 Å, the β4 and β5 strands, and the connecting loop. An important consequence of these choreographed changes is the exposure of Ser506 side chain, which together with Gly505 plays an important role in transmission of the ANF signaling of the catalytic module of ANF-RGC. This feature of the model has been experimentally validated through site directed mutation studies [38]. The mutation G505A reduces the ATP-dependent transduction activity of ANF-RGC by more than 55%; S506A by 64% and of G505A, S506A together by about 75% [38]

The present study analyzes the role of the larger lobe of the ARM. This lobe consists of 185 residues, aa 587–771. It is predominantly helical, composed of 8 α-helices and 2 β strands. The ARM model predicts that the ATP-dependent configurational changes in the small ATP-bound lobe are transmitted to the second lobe and result in a movement of the αEF helix by 2–5 Å. A conserved 669WTAPELL675 motif constitutes this helix. The movement exposes this hydrophobic motif thus, promotes its direct (or indirect) interaction with and activation of the catalytic module of ANF-RGC [31, 39]. What follows is the systematic functional analysis of this motif and its role in transmitting and transducing the configurational events from the smaller lobe to the catalytic module of ANF-RGC.

Tryptophan Fluorescence Spectroscopy

ARM constructs

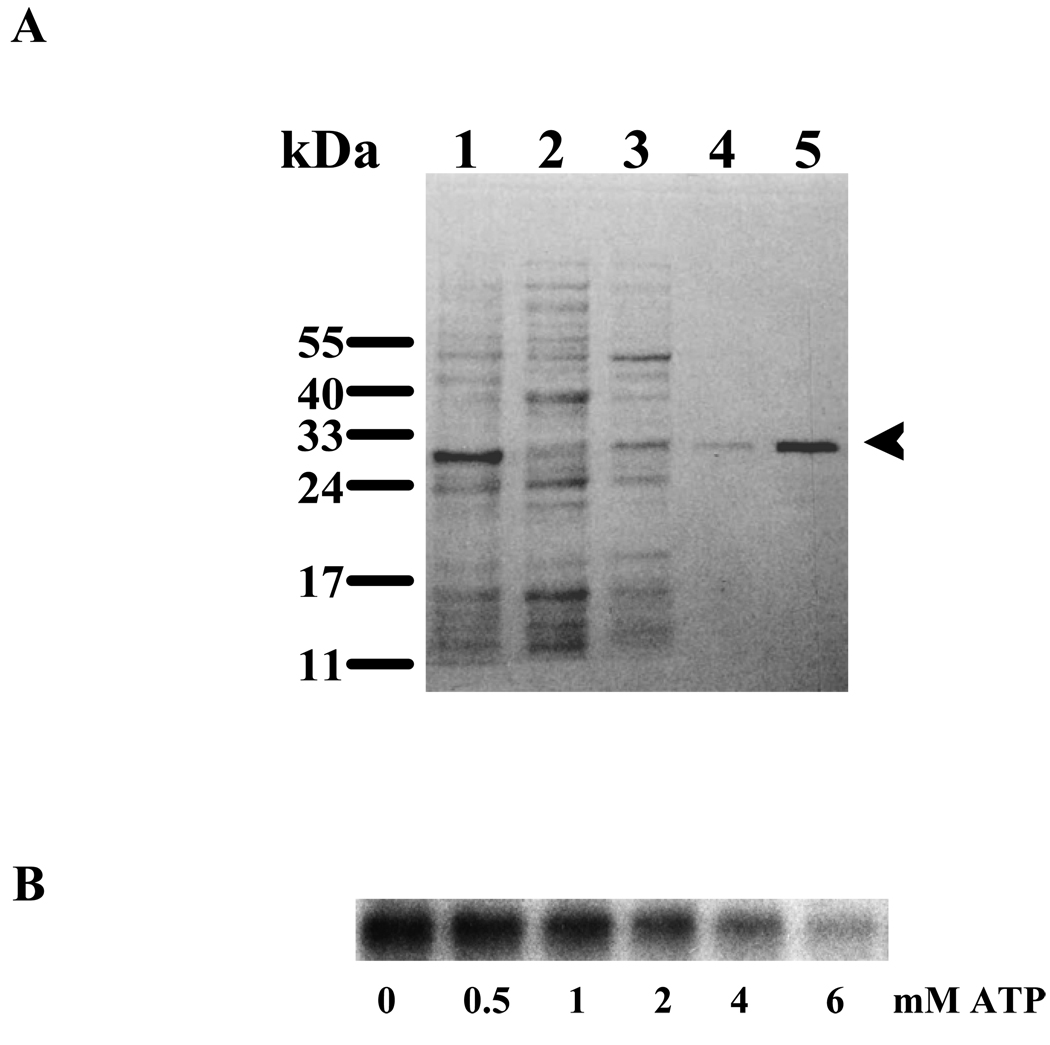

To accomplish the stated objective, the first task was to construct the appropriate ARM constructs. These constructs must possess two essential domains: ATP binding and the transduction containing 669WTAPELL675 motif. The aa486–692 fragment of the ARM domain was chosen, expressed in bacteria and purified as a soluble His-tagged protein (Fig. 2A: lane 5, indicated by an arrowhead). Its calculated molecular mass is 28.1-kDa, 23.3-kDa of the ARM and 4.8 kDa of the His-tag. The fragment was tested for ATP binding through a photoactive probe, 2-azido ATP. It is noted that the His-tag present in the 28.1-kDa ARM fragment does not bind azido-ATP (34). This fragment was incubated with 1 µCi (100 pmoles) of [γ32P]-2-azido-ATP and UV cross-linked. The reaction mixture was resolved by SDS-PAGE and the radiolabeled protein was visualized by autoradiography (Fig. 2B: lane “0 mM ATP”). To test the specificity of ATP binding, the increasing amounts of non-radioactive ATP were added to the reaction mixtures containing [γ32P]-2-azido-ATP, which were then UV-cross-linked and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. A typical autoradiogram is presented in figure 2B (lanes “0.5 – 6 mM ATP”). The autoradiogram shows that the increased concentrations of non-radioactive ATP compete for the radioactive 2-azido-ATP binding site in the ARM fragment. These results prove that the 28.1-kDA ARM fragment retains the native feature of ATP binding.

Figure 2.

(A) Purification of the ARM domain of ANF-RGC. The ANF-RGC ARM domain fragment aa 486–692, was expressed in E.coli and purified to homogeneity. Lane 1-total cell lysate; Lanes 2 & 3- unbound proteins; Lane 4- eluted protein; Lane 5 - purified and concentrated ARM. The positions of the molecular weight markers are given alongside. An arrowhead indicates the purified protein. (B) Specificity of the ATP binding to the ARM domain. One µg of the wtARM protein was UV cross-linked with [γ32P]-2-azido-ATP in the absence and presence of increasing concentrations of ATP. The reaction mixtures were analyzed through SDS-15%PAGE and the radiolabeled proteins were visualized by autoradiography.

The 28.1-kDA ARM fragment contains two tryptophan residues, at positions 601 and 669. Therefore, this fragment is appropriate for tryptophan fluorescence analysis.

To segregate the effects of the two tryptophans, each one was mutated through site-directed mutagenesis, resulting in two ARM domain mutants, ARM-W601A (contains only W669) and ARM-W669A (contains only W601). These mutants were expressed in bacteria, purified and assessed for their ATP binding characteristics to assure their functional integrities.

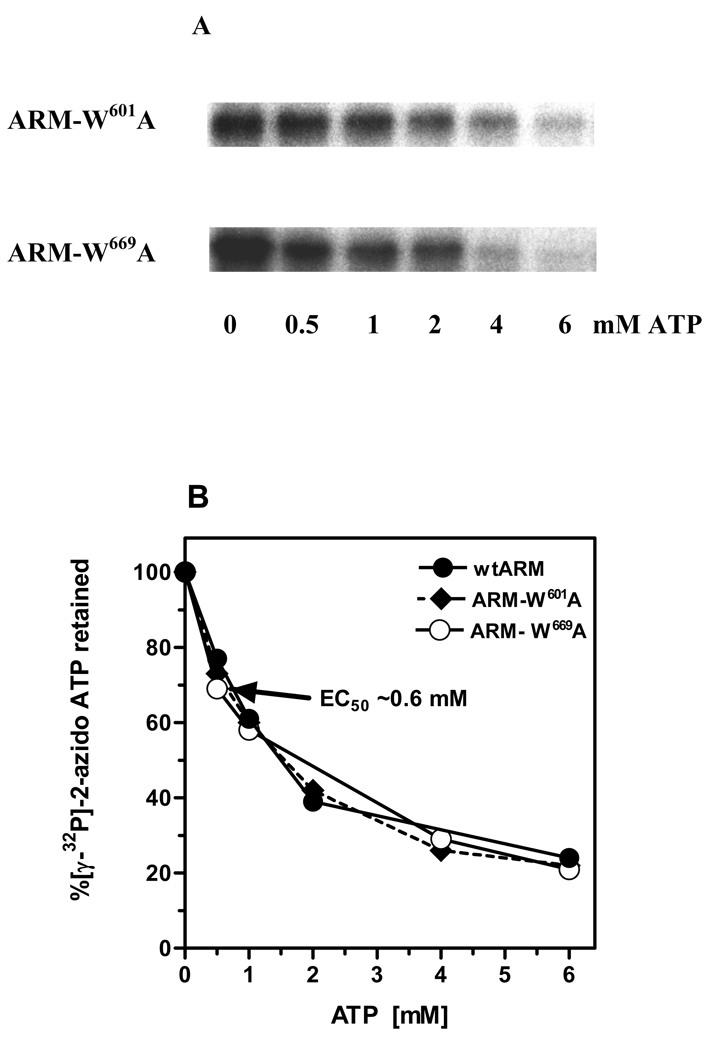

Both tryptophan mutants bound [γ32P]-2-azido-ATP (Fig. 3A: lane “0 mM ATP”). The specificity of 2-azido-ATP binding was assessed through displacement of the [γ32P]-2-azido-ATP by an excessive amount of unlabeled ATP (Fig. 3A: lanes “0.5 – 6 mM ATP”). The displacement was quantified by scintillation counting (Fig. 3B). The results showed that non-radioactive ATP competed for the [γ32P]-2-azido-ATP binding domain in a dose-dependent fashion. The 50% bound [γ32P]-2-azido-ATP was displaced by 0.6 mM ATP and ~80% was displaced by 3 mM ATP. The displacement profiles were almost identical for the two mutants and virtually undistinguishable from the wt-ARM (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Specificity of the ATP binding to the ARM-W601A and ARM-W669A mutants.

(A) One µg of each mutant, ARM-W601A and ARM-W669A, was UV cross-linked with [γ32P]-2-azido-ATP in the absence and presence of increasing concentrations of ATP. The reaction mixtures were analyzed through SDS-15%PAGE and the radiolabeled proteins were visualized by autoradiography. (B) Radiolabeled bands after autoradiography were cut out from the gel, counted for radioactivity (Cherenkov) and the percentage of radioactivity retained was calculated. WtARM was processed identically and served as control.

These results demonstrated that the three proteins, wtARM and both mutants, are functionally equivalent in their ATP-binding properties and, therefore, are appropriate for comparative fluorescence studies.

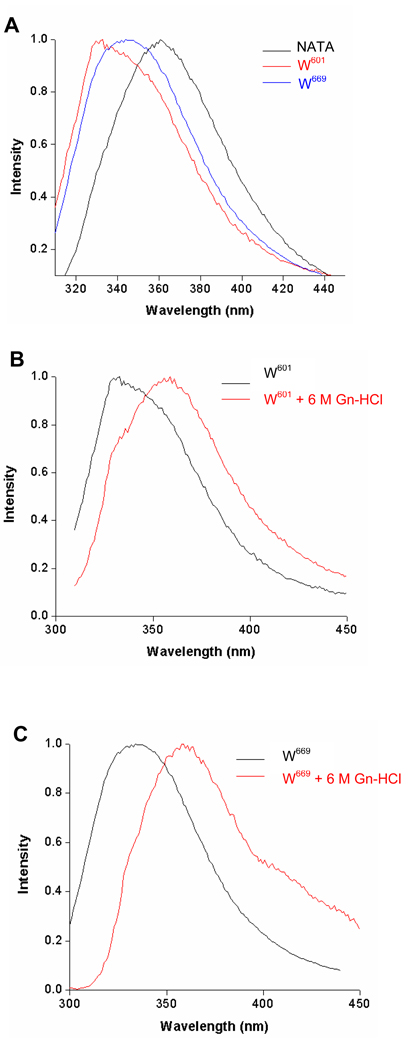

The W669 residue is in more polar environment than the W601 residue

When excited at 295 nm the fluorescence emission λmax for the wt ARM domain was at 340 nm. Under identical conditions, the observed λ max was at 332 nm and 345 nm for its mutants, ARM-W669A (fluorescence of W601) and ARM-W601A (fluorescence of W669), respectively (Fig. 4A). These values indicate that the two tryptophan residues contribute almost equally to the fluorescence of the wt-ARM domain.

Figure 4.

(A) Fluorescence emission spectra of the ARM domain W601 and W669 and of N-acetyl tryptophanamide (NATA). The ARM domain mutants ARM-W669A (W601) and ARM-W601A (W669) dissolved in 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8 buffer containing 1 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol and 0.2% laurosarcosyl were excited at 295 nm and their fluorescence spectra were measured as described in “Materials and Methods”. NATA was dissolved in water at a concentration of 1 µM and was treated identically. (B) Fluorescence emission spectra of the ARM domain W601 and (C) of W669 in native and denatured proteins. The ARM domain mutants were denatured using 6 M guanidine-HCl as described in “Materials and Methods”. The spectra were normalized and corrected for the background.

The fluorescence λmax is reflective of the polarity of the microenvironment surrounding a tryptophan residue [43, 44]. Increasing polarity causes red shift in the fluorescence λmax and decreasing polarity results in its blue shift. Therefore, the observed λ max values of 332 nm for W601 and 345 nm for W669 indicate that W669 is located within relatively more polar environment than W601.

This conclusion was supported by the comparative fluorescence analysis of both tryptophan residues and of the N-acetyl tryptophanamide fluorescence in aqueous solution. In this case the tryptophan is totally exposed to polar environment and its fluorescence exhibits maximal achievable λmax for tryptophan in water. After excitation at 295 nm the N-acetyl tryptophanamide fluorescence λmax was at 360 nm (Fig. 4A). The relative blue shift in the fluorescence of both ARM’s tryptophans indicates that their environments are less polar than that of N-acetyl tryptophanamide; and, comparatively, the environment of W601 is less polar than of W669. Only after the proteins were denatured with 6 M guanidine-HCl their fluorescence λmax was comparable with the fluorescence of N-acetyl tryptophanamide reaching 355 – 360 nm (Figures 4B and 4C).

That the environments of the two tryptophan residues are different from each other was further supported through the determination of their accessibility to collisional fluorescence quencher. The Stern-Volmer quenching constant KD quantitatively describes this accessibility [45, 46]. The KD values for W601, W669 and N-acetyl tryptophanamide were determined under native and denatured conditions using acrylamide as a quencher. Under native conditions the KD for W601 was 4.0 and for W669 it was 5.5. The KD value for N-acetyl tryptophanamide was 24.5 (Table 1). Thus, both ARM’s tryptophan residues are significantly less accessible to acrylamide than N-acetyl tryptophanamide is and the lowering is 6.1-fold for W601 and 4.5-fold for W669. Between themselves, W601 is 27% less accessible than W669. These results demonstrate that both residues are shielded from the solvent, yet the shielding of W601 is stronger than that of W669.

Table 1. Accessibility of W601 and W669 to collisional fluorescence quencher.

Values are the Stern-Volmer quenching constants (KD) obtained as described under “Materials and Methods”.

Proteins were denatured by incubation in a buffer containing 6 M guanidine-HCl for 3 min.

Titration with acrylamide followed the denaturation step.

Stern-Volmer analysis of the denatured proteins showed that the quenching constants for both tryptophan residues, in comparison with the constants for the native proteins, increased and they became closer to each other: 7.8 for W601 and 7.1 for W669 (Table 1). These values show that after denaturation both tryptophan residues are almost equally accessible to acrylamide. The KD values for both ARM’s tryptophans are, however, still in excess of 3-fold lower than the 24.5 KD value for N-acetyl tryptophanamide (Table 1). This suggests that even after denaturation both tryptophane residues continue to be partially shielded by the side-chains of the surrounding amino acids, which make them not fully accessible to the quencher [47].

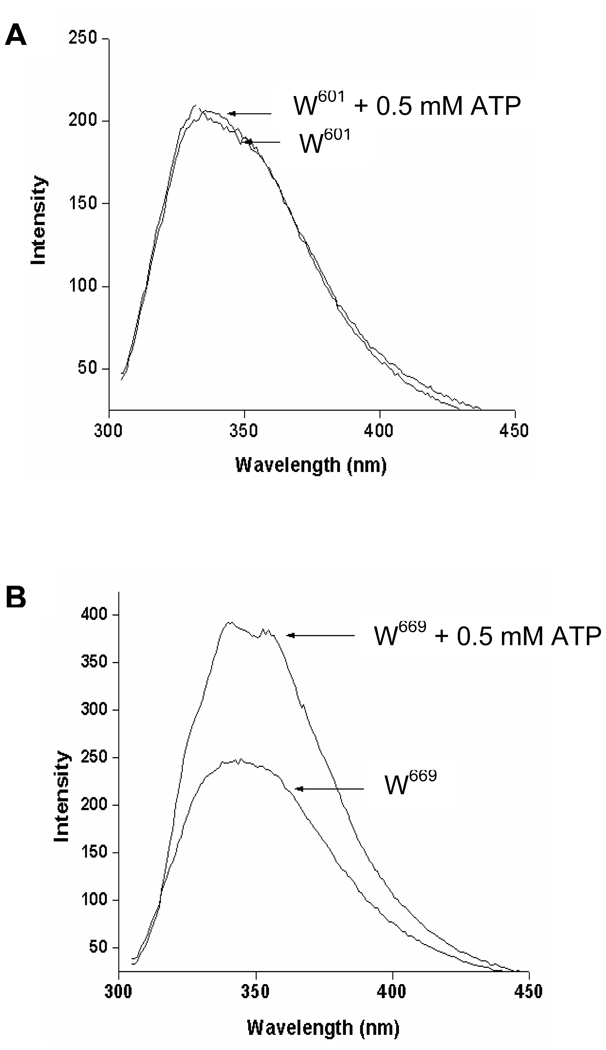

ATP binding affects the configurational arrangement around W669 in the transduction domain of ARM

To assess if ATP binding to the smaller lobe of ARM causes the concomitant stereospecific changes in the larger lobe of ARM, the individual fluorescence of W601 and W669 was measured in the presence of ATP-MgCl2. Because 0.5 mM ATP causes the maximal activation of the wt-ANF-RGC, this ATP concentration was chosen for the fluorescence experiments.

When W601 was excited in the presence of 0.5 mM ATP and 0.5 mM MgCl2 and the emitted fluorescence was measured, neither change in fluorescence λmax nor intensity was observed (Fig. 5A). In contrast, when the fluorescence of W669 was measured under the same experimental conditions, there was a significant increase of fluorescence intensity as compared with the fluorescence in the absence of ATP (Fig. 5B). The increase was about 37%. In addition, ATP caused 5 nm blue shift in the fluorescence λmax (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that binding of ATP to the ARM induces a concomitant conformational change around W669; as a result, its surrounding becomes less polar. The ATP binding, however, does not affect the steric arrangement around the W601 residue.

Figure 5. ATP effect on the fluorescence of the ARM domain’s W601 (A) and W669 (B).

Two µM solutions of the ARM domain mutants in Tris-HCl, pH 8, 1mM of MgCl2 and 5% glycerol were used for the experiments. 0.5 mM ATP was then added to the solution and the fluorescence spectra were measured after excitation at 295 nm.

W669 is closer to the ATP-binding pocket than W601

Both tryptophan residues, W669 and W601, reside outside the ATP-binding pocket. The ARM model predicts that upon ATP binding, structural changes in the vicinity of the ATP binding pocket, cause movement of W669 towards the smaller lobe in the direction of the ATP binding pocket. There is no significant change observed in the position of the W601, however [31, 39].

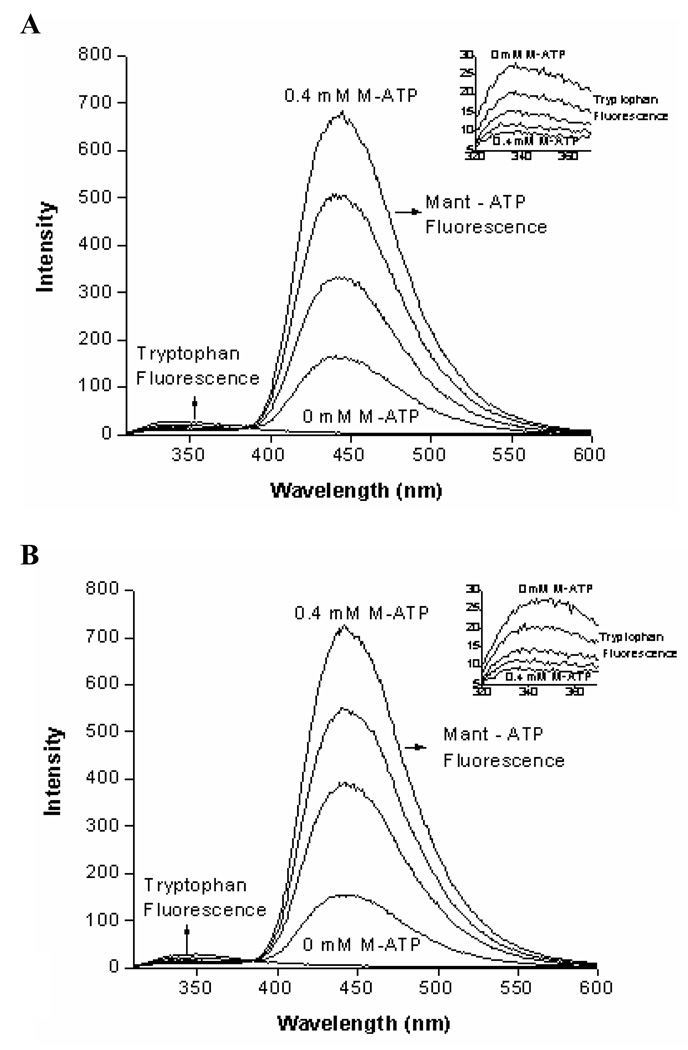

To experimentally validate this prediction, Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) technique was applied. ATP-fluorescent derivative, 2’-0-(N-methylantraniloyl)-adenosine 5’-triphosphate (Mant-ATP) was used as a probe. Because Mant-ATP’s maximum absorption at 355 nm overlaps with emission of the ARM’s tryptophan residues but its maximum emission at 448 nm does not, Mant-ATP is the perfect reagent to assess the effect of the ATP binding on the spatial changes occurring around the tryptophan residues.

The ARM-mutants were individually excited in the presence of increasing concentrations (0–0.4 mM) of Mant-ATP and fluorescence of the respective tryptophan residues was measured (Fig. 6). In both cases the presence of Mant-ATP resulted in a dose-dependent decrease of the tryptophan fluorescence intensity with a concomitant increase of Mant-ATP own fluorescence (Fig. 6A for W601 and fig. 6B for W669). To quantitatively characterize the Mant-ATP quenching effect on the fluorescence of both tryptophan residues, Stern-Volmer’s quenching constants were calculated. These were 4.8 and 6.1 for W601 and W669, respectively (Table 2), and indicated that Mant-ATP quenched the fluorescence intensity of W669 approximately 22% more than that of W601. Because the extent of quenching is reversely proportional to the distance between the fluorophore and the quencher, the Stern-Volmer values prove that W669 is closer to the ATP-binding pocket than W601.

Figure 6. Mant-ATP effect on the fluorescence of the ARM domain’s W601 (A) and W669 (B).

ARM domain mutants were individually excited at 295 nm in the presence of increasing concentrations (0–0.4 mM) of Mant-ATP and the emission spectra were recorded. Quenching of tryptophan fluorescence in the presence of Mant-ATP is due to the Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) from tryptophan to Mant-ATP. INSETS show the enlarged part of the emission spectrum (320–370 nm) where the fluorescence of the tryptophan residue occurs.

Table 2. Effect of Mant-ATP (M-ATP) on the fluorescence of W601 and W669 residues.

Values are the Stern-Volmer quenching constants (KD) and the fluorescence life-times obtained as described under “Materials and Methods”

| W601 | W669 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence quenching | 4.8 | 6.1 | ||

| 0 mM M-ATP | 0.4 mM M-ATP | 0mM M-ATP | 0.4 mM M-ATP | |

| Fluorescence life-time | 3.04 ns | 3.29 ns | 3.60 ns | 3.67 ns |

ATP forms a stable complex with its binding pocket

The ability of Mant-ATP to quench fluorescence of both tryptophans indicates that relatively short distance separates it from these residues. It however, does not allow discriminating whether Mant-ATP’s interaction with ARM domain is static or dynamic, meaning, if Mant-ATP acts as a static or a collisional quencher. The static quencher forms a stable complex with its binding domain whereas the collisional quencher does not. This was determined using time-resolved FRET fluorescence technique. In this technique, the life-time of a fluorophore changes if the quencher interacts with it dynamically but remains unchanged when the interaction is static.

The two ARM’s tryptophans were exposed to the excitation wavelength of 295 nm and the average life span of the fluorescence was measured in absence and the presence of 0.4 mM Mant-ATP. In its absence for W669 it was 3.60 ns, and in its presence it was 3.67 ns (Table 2). For W601, the respective values were 3.04 ns and 3.29 ns (Table 2). These results indicate that there is no statistical difference between the fluorescence life times of both tryptophans in the absence and presence of Mant-ATP. It is, thus, concluded that the quenching by Mant-ATP is static, therefore, ATP exists as a complex with the ARM.

Together, these fluorescence studies experimentally validate the earlier theoretical predictions of the model [38, 39]. They prove that 1) ATP forms a stable complex with its ARM pocket; 2) stereoscopically, W669 residue is closer than the W601 residue to the ATP bound pocket; and 3) ATP binding induces conformational changes around W669 but not around W601 [38, 39]. This means that the ATP-bound ARM state of ANF-RGC affects the stereochemistry of the W669 residue but not of the W601.

Modeling Studies

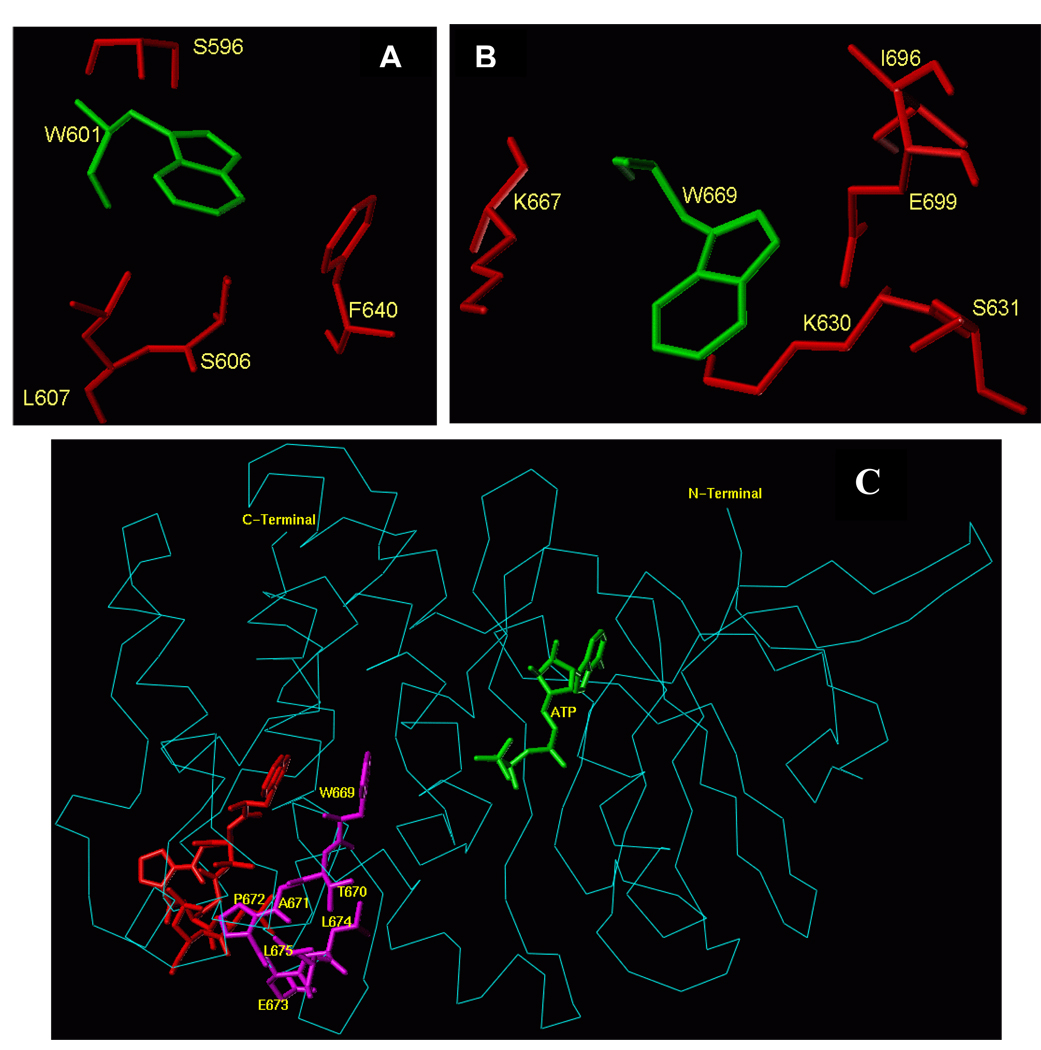

Three-dimensional ARM domain model explains the results of the fluorescence studies and depicts the catalytic domain activation mechanism

To pictorially visualize and explain the fluorescence results in 3D-terms, the ARM domain model analysis was focused on W601 and W669 and their surroundings in the apo- and ATP-bound states [38, 39; reviewed in: 31].

The analysis shows that the environment and conformations of the two tryptophanes in the two states are very different. Both residues reside in the larger lobe of the ARM domain, outside the ATP-binding pocket. The W601 residue is a part of the helix E structure [38, 39] and does not interface the ATP binding pocket (Fig. 1). Its side-chain is oriented towards the protein surface, and it is flanked by several hydrophobic residues, F640, L607, S606 and S596 (Fig. 7A). Thus, the fluorescence λmax value of W601 at 332 nm is in accordance with these defined structural features.

Figure 7.

(A) Amino acid residues surrounding W601 and (B) Amino acid residues surrounding W669 within the ARM domain. Amino acid residues depicted in red are located within a 4 Å sphere from the respective tryptophan residue (green). (C) Conformational changes within the 669WTAPELL675 motif induced by ATP binding to the ARM domain. The backbone structure of the ATP-bound ARM domain is shown in cyan and the ATP molecule is in green. The 669WTAPELL675 motif is shown in magenta color. Apo structure of the ARM domain was superimposed on the ATP-bound form to assess the relative, ATP binding induced, conformational changes. For clarity, only the 669WTAPELL675 motif (shown in red) of the apo-enzyme is visible. ATP binding results in a more compact structure of the ARM domain: the W669 side chain moves towards the ATP binding pocket while the side chains of T670, E673, L674 and L675 move toward the protein surface [compare the orientation of side chain of these amino acid residues before (in red) and after (in magenta) ATP binding]. This movement changes the surface properties of the ARM domain (39; reviewed in: 31). The movement towards the surface of the protein is poised to facilitate interaction of this amino acid stretch with subsequent transduction motif, possibly within the catalytic domain, propagation of the ANF/ATP binding signal and activation of the catalytic domain.

W669 is located at the end of a loop connecting β8 strand and αEF helix [38, 39; and Fig. 1]. It is a part of the hydrophobic motif, 669WTAPELL675. The side chain of W669 is flanked by the polar residues: E699, S631, K667, K630 and L696 (Fig. 7B). Therefore, the red shift of the fluorescence λmax of W669 at 345 nm is in accordance with these structural features.

The 3D-ARM model also predicts that the structural motif 669WTAPELL675 faces the ATP binding pocket (Fig. 1). None of the residues of this motif has a direct interaction with ATP, yet ATP binding affects their orientations [38, 39]. These changes in their orientations cause a significant increase in the surface hydrophobicity [31, 39]. These features are now experimentally validated by the fluorescence studies as evidenced by a blue shift of the emission spectrum and an increase of the fluorescence intensity (Fig. 5B).

With these new experimentally-validated added features, further insights into the structural dynamics of the 669WTAPELL675 transduction motif of the ARM model were attempted. Superimposition of the ATP-free and the ATP-bound forms indicated that ATP binding induces contraction of the entire ARM domain and affects the orientation and environment of W669 but not of W601. The contraction results in shortening of the distance between W669, but not W601, and the ATP binding pocket (Fig. 7C). ATP binding also causes reorientation of the W669 side chain. It turns and becomes more shielded by the surrounding amino acids (blue shift in W669 fluorescence upon ATP binding; note that the figure shows only the backbone of the amino acid structure but not the respective side chains). Turning of the W669 side chain pushes the remainder of the motif, 670TAPELL675, to the surface resulting in its exposure. It is envisioned that this exposure makes these residues accessible for interaction with another transduction module of ANF-RGC, possibly with the catalytic domain, propagation of the ATP binding signal, and ultimately activation of the catalytic module.

Mutational analysis

The 669WTAPELL675 transduction motif of ARM is obligatory for ATP-dependent signaling of ANF-RGC

The above prediction was tested through two approaches, involving mutagenesis technique. In Approach 1, deletion mutagenesis and in Approach 2, point mutagenesis, were used.

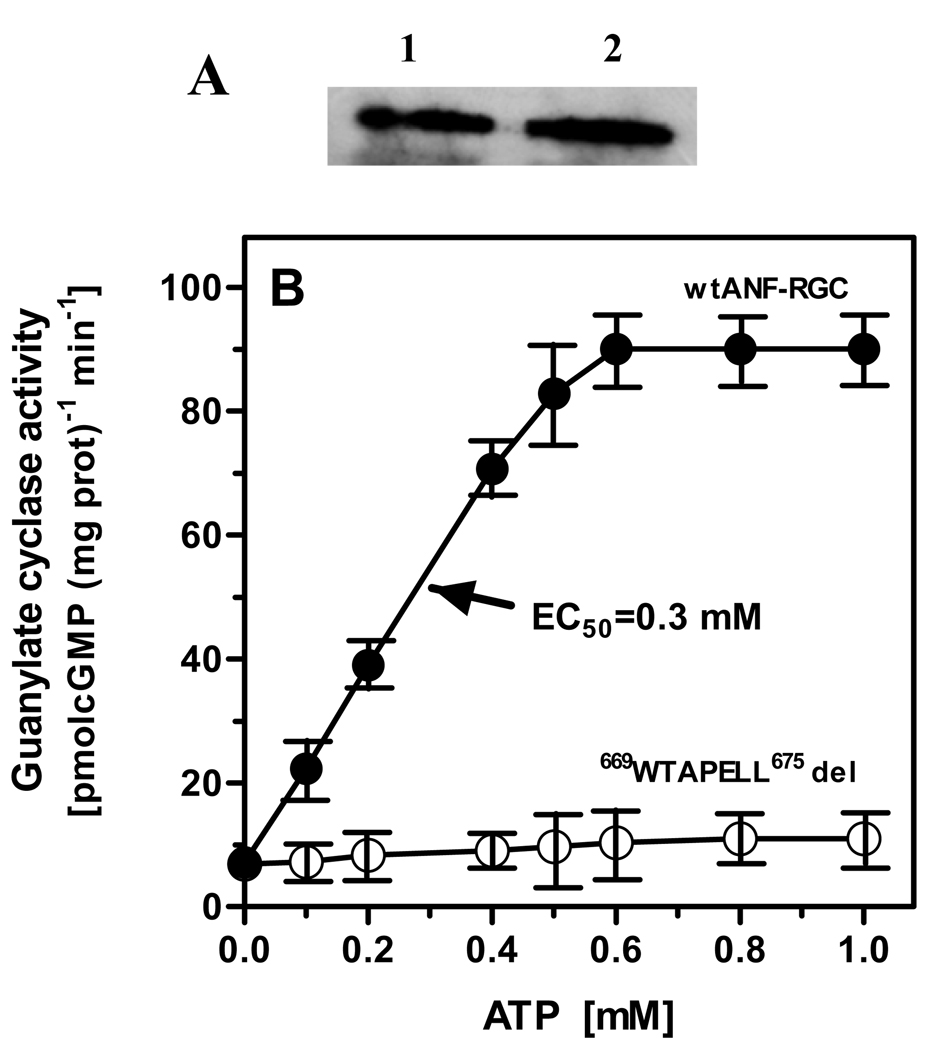

Approach 1

A deletion mutant of ANF-RGC was prepared; it did not contain the 669WTAPELL675 motif. To ensure that the deletion did not affect mutant’s basal activity, it was compared with the parent ANF-RGC’s activity. Both the parent and the mutant cDNAs were individually expressed in COS cells, the membrane fractions were prepared, the expression levels of the proteins were checked through Western-blots, and the basal and ANF/ATP-dependent guanylate cyclase activities were assessed.

Basal activity

Figure 8A shows that the membranes contained equal levels of the parent and the mutant proteins. They also exhibited almost identical activity (figure 8B: compare the values of 6.9 with 7.2 pmol cyclic GMP/min/mg). This conclusion was further verified by the determination of their Km values for the substrate GTP. They were almost identical, 614 µM for the wt and 608 µM for the mutant protein.

Figure 8. Role of the 669WTAPELL675 motif in ANF-RGC signal transduction.

(A) Western analysis. COS cells were transfected with wt ANF-RGC or its 669WTAPELL675 deletion mutant and their particulate fractions were prepared as described in ”Materials and Methods”. The membranes were analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies against ANF-RGC. Lane1, wt ANF-RGC; Lane 2, 669WTAPELL675 deletion mutant. (B) ANF/ATP-dependent cyclase activity of ANF-RGC. Wild type ANF-RGC and the deletion mutant were individually expressed in COS cells and their membranes were analyzed for ANF/ATP-dependent cyclase activity. Cyclic GMP formed was measured by radioimmunoassay. The experiment was done in triplicate and repeated two times for reproducibility. The results presented (mean ± SD) are from these experiments.

These results demonstrated that deletion of the 669WTAPELL675 motif does not affect the expression, affinity for the substrate, and the basal catalytic activity of the mutant. Thus, the deletion mutant is biochemically sound and can be used to assess the transduction role of the 669WTAPELL675 motif in the ATP-dependent ANF signaling of ANF-RGC.

ANF/ATP-dependent activity

The membranes expressing wt-ANF-RGC or the 669WTAPELL675 deletion mutant were exposed to constant, 10−7 M, ANF concentration and increasing concentrations of ATP. As anticipated, the activity of wt-ANF-RGC was stimulated in an ATP-dose-dependent fashion with an EC50 of 0.3 mM (Fig. 8B). The maximal stimulation was about 12-fold above the basal level (Fig. 8B). Under the same experimental conditions, the ATP-dependent ANF stimulation of the 669WTAPELL675 deletion mutant of ANF-RGC was statistically negligible (Fig. 8B).

The remote possibility that the lack of stimulation of the mutant might have incurred indirectly due to the inactivation of its extracellular ANF receptor domain was ruled out by the following experiment. The receptor activities of both the wt-ANF-RGC and the mutant were assessed through ANF binding, using [125I]ANF probe. Their receptor activities were statistically equal with the respective specific binding values of 9.7±0.6 and 10.1±0.9 pmol [125I]ANF/mg protein.

Keeping in mind that 669WTAPELL675 motif has no role in the binding of ATP [31, 39] the above results prove that the motif is exclusively involved in the ATP-dependent transduction activity of the ANF signaling of ANF-RGC.

Mutational analysis of the 669WTAPELL675 motif

The model-based prediction (Modeling studies) that the individual residues of the 669WTAPELL675 motif play a role in the transduction activity of the ATP signal, was experimentally assessed through the alanine scanning mutagenesis. W669, T670, P672 and E673 residues were mutated to alanine, resulting in four mutants: W669A, T670A, P672A and E673A. They were individually expressed in COS cells and their membranes were analyzed for ANF/ATP-dependent cyclase activity. Wt-ANF-RGC served as control.

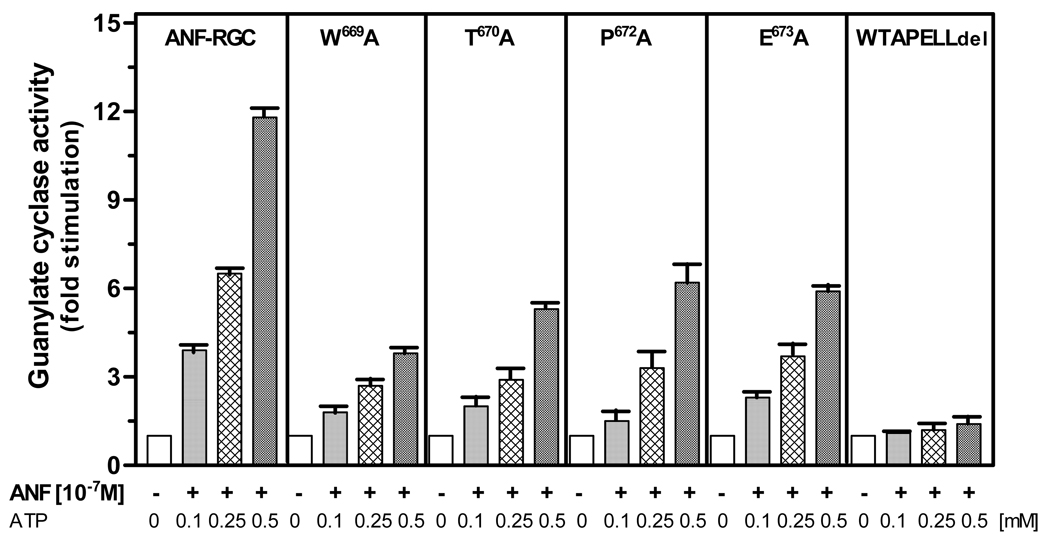

The basal activities of all the mutants ranged between 6 and 7 pmol cyclic GMP formed/min/mg protein, which was comparable to the control activity of 7.2 pmol cyclic GMP formed/min/mg protein. Thus, all these mutants were properly and equally targeted to cell plasma membrane. They, however, responded in different manners to the ANF/ATP stimulation. The mutants did respond to the ANF/ATP signals but the response was only partial and it was not identical; the saturation activity of wtARM was 12-fold over its basal value, it was 4-fold for W669A mutant and 6- to 7-fold for T670A, P672A, and E673A, mutants (Fig. 9). For comparison, the results with the total 669WTAPELL675 deleted motif are also provided side by side in figure 9.

Figure 9. Alanine scanning of the 669WTAPELL675 motif of the ARM domain.

The residues W669, T670, P672, and E673 in ANF-RGC were individually mutated to alanine. The mutants were expressed in COS cells and analyzed for ANF/ATP-dependent cyclase activity. Wt-ANF-RGC and 669WTAPELL675 ANF-RGC deletion mutant were treated identically and served as controls. Cyclic GMP formed was measured by radioimmunoassay. The experiment was done in triplicate and repeated two times for reproducibility. The results presented (mean ± SD) are from these experiments.

These results demonstrate that all the indicated residues of the 669WTAPELL675 motif contribute selectively to the motif’s function, together making the whole motif most functional in its transduction activity.

Within the 669WTAPELL675 transduction motif W669 is predicted to be the key residue. Its movement pushes the remainder of the motif, 670TAPELL675, to the surface. As a consequence, 670TAPELL675 gets exposed (Modeling studies).

This prediction was further experimentally assessed with a rationale that this special function of the W699 residue within the transduction motif 669WTAPELL675 is due to its bulky, aromatic ring structure.

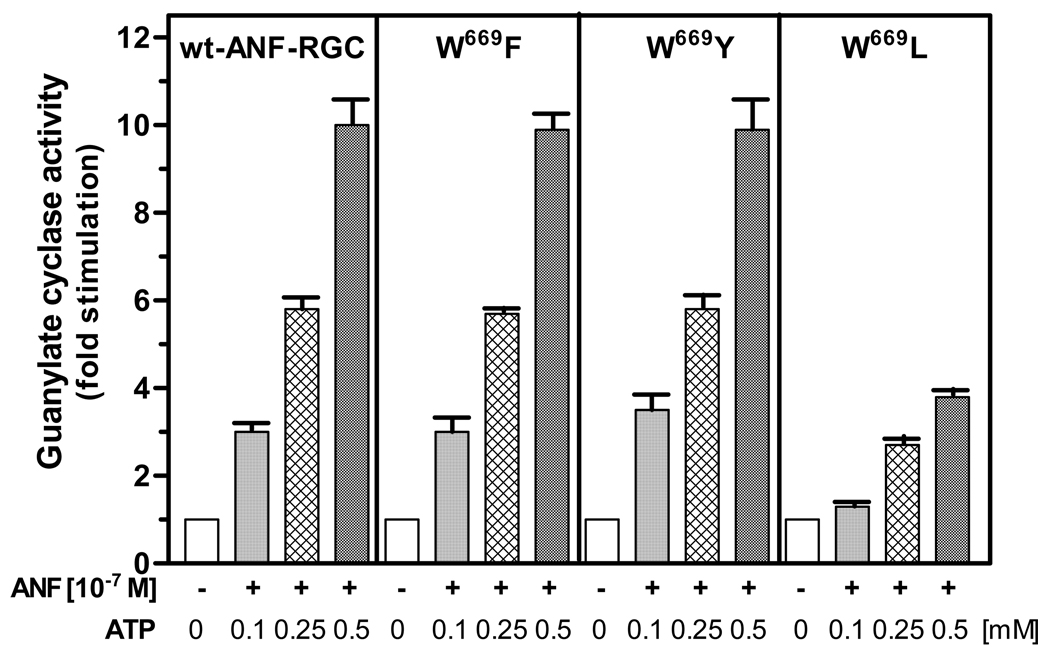

To test this, W699 was mutated to two aromatic ring containing amino acids: phenylalanine and tyrosine, and to an aliphatic residue, leucine. These mutants are represented as W669F, W669Y and W669L. If the W669 function is really due to is bulky size, aromatic side chain then the first two mutants should respond to the ATP/ANF signal like the wild-type ANF-RGC and the last one should be only minimally responsive or totally unresponsive.

Figure 10 shows that the prediction is, indeed, correct. W669F and W669F mutants responded to the ANF/ATP signal like the wild-type ANF-RGC; the W669L mutant was only slightly responsive to the ATP/ANF signal (29% compared to the control) and the response was comparable to that of the W669A mutant.

Figure 10. An aromatic amino acid must occupy the 669 position in ANF-RGC.

W669 of the full length ANF-RGC was mutated to fenylalanine, tyrosine and leucine. The mutants were expressed in COS cells and analyzed for ANF/ATP-dependent cyclase activity. Cyclic GMP formed was measured by radioimmunoassay. The experiment was done in triplicate and repeated two times for reproducibility. The results presented (mean ± SD) are from these experiments.

DISCUSSION

The present comprehensive study defines the molecular identity and provides the biochemical description of a new paradigm of the ATP transduction mechanism that controls the ANF signaling of ANF-RGC. About a decade ago this transduction mechanism was predicted through simulation of the 3D-ARM model [38, 39]. The presented study experimentally validates that prediction and provides detailed principles of its operation.

3-D ARM model

The model predicted that one of the three significant changes that occur in configuration of the ARM of ANF-RGC upon ATP binding is that “It moves the αEF helix by 2-5 Ả. It is possible that this movement exposes the site…involved in the interaction between the helix and the catalytic domain. This, in turn, results in the ATP-dependent signaling of the cyclase” [38, 39]. The structural motif of the αEF helix is 669WTAPELL675.

Model explanation

This meant that the ATP-binding fold, that exists in the smaller lobe of the ARM domain, upon its occupancy by ATP sets in motion the structural movement and rotation of the floor of the pocket [31, 38, 39] and these structural dynamics, in turn, are transmitted and affect the structural dynamics of the αEF helix motif 669WTAPELL675 (residing in the larger lobe of the ARM domain) that directly or indirectly cause stimulation of the catalytic domain of ANF-RGC.

Issue 1

Does ATP binding to its pocket selectively cause configurational changes around and within the 669WTAPELL675 motif?

The tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopic studies demonstrate that this, indeed, is the case. The binding of ATP to the ARM’s smaller lobe induces conformational changes that are transduced to the 669WTAPELL675 motif. These changes make the surrounding of the W669 residue less polar. In contrast, no such change occurs around the W601 residue of the E helix.

Issue 2

Are the environments of W601 and W669 different?

Again the tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopic studies, complemented by the quantitative Stern-Volmer quenching analyses, done under the native and denatured conditions of the proteins, demonstrate that the answer is yes. These analyses show that the environment around W601 is less polar than that around W669. Both tryptophans are partially shielded by its surrounding residues; however, the shielding is lesser in the case of W669. Thus, W601 and W669 are in different environments.

Issue 3

Does ATP binding cause movement of W669 in the direction of the ATP binding pocket?

The analyses through FRET and time-resolved fluorescence techniques demonstrate that the answer is ”yes”. The findings show that W669 is physically closer to the ATP-binding pocket than W601.

Molecular modeling studies pictorially visualize the above conclusions and explain the fluorescence results in three dimensional terms. The model shows that W669 resides in the large lobe of the ARM domain. It interfaces the ATP binding pocket (Fig. 1), and its side chain is flanked by the polar residues: E699, S631, K667, K630 and L696 (Fig. 7B).

In contrast, W601 does not interface the ATP binding pocket (Fig. 1), and its side chain is flanked by the hydrophobic residues: F640, L607, S606 and S596 (Fig. 7A).

In addition to these disclosures, modeling studies provide clues on the mechanism of the ATP-induced structural dynamics of the 669WTAPELL675 motif. They predict that the ATP binding to the ARM induces contraction of the entire ARM domain, resulting in shortening of the distance between W669 and the ATP binding pocket. It also reorients the W669 residue’s side chain. As a consequence, the side chain turns and is now more shielded by the surrounding amino acids. These dynamic events result in exposure of the remaining residues of the 669WTAPELL675 motif, the 670–675 residues, TAPELL.

An important aspect of these predictions is that W669 is the driving force for functionality of the 669WTAPELL675 motif. In this picture, W669 plays a pivotal role in exposing its remainder motif, 670TAPELL675.

Based on these clues, below-described three issues related with functionality of the 669WTAPELL675 motif were experimentally assessed.

Issue 4

Is the 669WTAPELL675 motif biochemically functional?

This issue has been resolved through the deletion-mutation expression studies. These studies demonstrate that 669WTAPELL675 motif is not essential to the basal activity of ANF-RGC. It is, however, absolutely critical for its ATP-dependent signaling of ANF-RGC.

Issue 5

Do individual residues of the 669WTAPELL675 play the selective roles in the transduction activities of the whole motif?

The answer is “yes”. Site-directed mutational analysis of the individual residues--W669, T670, P672, E673—demonstrate that these residues do not influence the basal activity of the motif. Each of them partially, yet not fully, influences the activity of the whole motif.

Issue 6

Is W669 the key residue for functionality of the 669WTAPELL675 motif?

The answer is yes. It was reasoned that the special function of the W699 residue within the transduction motif 669WTAPELL675 is due to its bulky and/or aromatic ring structure. Validity of this idea is established through the site-directed mutagenesis studies. The W669F and W669Y mutations do not change the natural phenotype of the ANF-RGC. The mutants and the wild-type ANF-RGC have identical basal and identical ATP-dependent ANF signaling activities of ANF-RGC. However, W669A (Fig. 9) and W669L (Fig. 10) mutants lose most of its signaling activity.

In conclusion this study through sequential technologies involving steady-state, time-resolved tryptophan fluorescence, FRET, molecular modeling, site-directed and deletion mutagenesis, and reconstitution studies have provided the molecular, biochemical and functional identity of a motif, 669WTAPELL675, that is critical in the ATP-dependent signaling of ANF-RGC. The location of this transduction motif is in a different domain to that of the ATP-binding domain. It senses the ATP signal indirectly and becomes exposed. This stimulates the catalytic domain of ANF-RGC that resides in its C-terminal. This information advances our understanding how ANF signals ANF-RGC and, ANF-RGC controls blood pressure.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by NIH grants HL 070015, HL084584 (TD), DC 005349 (RKS), MD001633 (SB), and Texas Emerging Technologies Grant (IG and ZG)

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ANF, atrial natriuretic factor; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; ANF-RGC, atrial natriuretic factor receptor guanylate cyclase; ARM, ATP regulated module; FRET, Förster resonance energy transfer; Mant-ATP, 2’-0-(N-methylantraniloyl)-adenosine 5’-triphosphate.

REFERENCES

- 1.Paul AK, Marala RB, Jaiswal RK, Sharma RK. Coexistence of guanylate cyclase and atrial natriuretic factor receptor in a 180-kD protein. Science. 1987;235:1224–1226. doi: 10.1126/science.2881352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paul AK. Doctoral thesis. University of Tennessee; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuno T, Andersen JW, Kamisaki T, Waldman SA, Chang LY, Saheki S, Leitman DC, Nakane M, Murad F. Co-purification of an atrial natriuretic factor receptor and particulate guanylate cyclase from rat lung. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:5817–5823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pandey KN, Pavlou SN, Inagami T. Identification and characterization of three distinct atrial natriuretic factor receptors. Evidence for tissue-specific heterogeneity of receptor subtypes in vascular smooth muscle, kidney tubular epithelium, and Leydig tumor cells by ligand binding, photoaffinity labeling, and tryptic proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:13406–13413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meloche S, McNicoll N, Liu B, Ong H, De Lean A. Atrial natriuretic factor R1 receptor from bovine adrenal zona glomerulosa: purification, characterization, and modulation by amiloride. Biochemistry. 1988;27:8151–8158. doi: 10.1021/bi00421a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma RK. Evolution of the membrane guanylate cyclase transduction system. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2002;230:3–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma RK, Duda T, Venkataraman V, Koch K-W. Calcium-modulated mammalian membrane guanylate cyclase ROS-GC transduction machinery in sensory neurons: A universal concept. Curr. Topics Biochem. Res. 2004;6:111–144. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duda T, Goraczniak R, Sharma RK. Site-directed mutational analysis of a membrane guanylate cyclase cDNA reveals the atrial natriuretic factor signaling site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:7882–7886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chinkers M, Garbers DL, Chang MS, Lowe DG, Chin HM, Goeddel DV, Schulz S. A membrane form of guanylate cyclase is an atrial natriuretic peptide receptor. Nature. 1989;338:78–83. doi: 10.1038/338078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowe DG, Chang MS, Hellmiss R, Chen E, Singh S, Garbers DL, Goeddel DV. Human atrial natriuretic peptide receptor defines a new paradigm for second messenger signal transduction. EMBO J. 1989;8:1377–1384. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03518.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang MS, Lowe DG, Lewis M, Hellmiss R, Chen E, Goeddel DV. Differential activation by atrial and brain natriuretic peptides of two different receptor guanylate cyclases. Nature. 1989;341:68–72. doi: 10.1038/341068a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duda T, Goraczniak RM, Sitaramayya A, Sharma RK. Cloning and expression of an ATP-regulated human retina C-type natriuretic factor receptor guanylate cyclase. Biochemistry. 1993;32:1391–1395. doi: 10.1021/bi00057a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulz S, Green CK, Yuen PS, Garbers DL. Guanylyl cyclase is a heat-stable enterotoxin receptor. Cell. 1990;3:941–948. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90497-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koller KJ, Lowe DG, Bennett GL, Minamino N, Kangawa K, Matsuo H, Goeddel DV. Selective activation of the B natriuretic peptide receptor by C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) Science. 1991;252:120–123. doi: 10.1126/science.1672777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schultz S, Singh S, Bellet RA, Singh G, Tubb DJ, Chin H, Garbers DL. The primary structure of a plasma membrane guanylate cyclase demonstrates diversity within this new receptor family. Cell. 1989;58:1155–1162. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90513-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duda T, Sharma RK. ONE-GC membrane guanylate cyclase, a trimodal odorant signal transducer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;367:440–445. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Labrecque J, Mc Nicoll N, Marquis M, De Lean A. A disulfide-bridged mutant of natriuretic peptide receptor-A displays constitutive activity. Role of receptor dimerization in signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:9752–9759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu H, Olshevskaya E, Duda T, Seno K, Hayashi F, Sharma RK, Dizhoor AM, Yamazaki A. Activation of retinal guanylyl cyclase-1 by Ca2+binding proteins involves its dimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:15547–15555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson EM, Chinkers M. Identification of sequences mediating guanylyl cyclase dimerization. Biochemistry. 1995;34:4696–4701. doi: 10.1021/bi00014a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thorpe DS, Niu S, Morkin E. Overexpression of dimeric guanylyl cyclase cores of an atrial natriuretic peptide receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1991;180:538–544. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y, Ruoho AE, Rao VD, Hurley JH. Catalytic mechanism of the adenylyl and guanylyl cyclases: modeling and mutational analysis. Proc.Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:13414–13419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Bold AJ. Atrial natriuretic factor: a hormone produced by the heart. Science. 1985;230:767–770. doi: 10.1126/science.2932797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pandey KN. Biology of natriuretic peptides and their receptors. Peptides. 2005;26:901–932. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Bold AJ, de Bold ML. Determinants of natriuretic peptide production by the heart: basic and clinical implications. J. Investig. Med. 2005;53:371–377. doi: 10.2310/6650.2005.53710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.John SW, Krege JH, Oliver PM, Hagaman JR, Hodgin JB, Pang SC, Flynn TG, Smithies O. Genetic decreases in atrial natriuretic peptide and salt-sensitive hypertension. Science. 1995;267:679, 681. doi: 10.1126/science.7839143. Erratum in: Science 267, 1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopez MJ, Wong SK, Kishimoto I, Dubois S, Mach V, Friesen J, Garbers DL, Beuve A. Salt-resistant hypertension in mice lacking the guanylyl cyclase-A receptor for atrial natriuretic peptide. Nature. 1995;378:65–68. doi: 10.1038/378065a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurose H, Inagami T, Ui M. Participation of adenosine 5'-triphosphate in the activation of membrane-bound guanylate cyclase by the atrial natriuretic factor. FEBS Lett. 1987;219:375–379. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang CH, Kohse KP, Chang B, Hirata M, Jiang B, Douglas JE, Murad F. Characterization of ATP-stimulated guanylate cyclase activation in rat lung membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1990;1052 doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(90)90071-k. 159-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chinkers M, Singh S, Garbers DL. Adenine nucleotides are required for activation of rat atrial natriuretic peptide receptor/guanylyl cyclase expressed in a baculovirus system. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:4088–4093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marala RB, Sitaramayya A, Sharma RK. Dual regulation of atrial natriuretic factor-dependent guanylate cyclase activity by ATP. FEBS Lett. 1991;281:73–76. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duda T, Venkataraman V, Ravichandran S, Sharma RK. ATP-regulated module (ARM) of the atrial natriuretic factor receptor guanylate cyclase. Peptides. 2005;26:969–984. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goraczniak RM, Duda T, Sharma RK. A structural motif that defines the ATP-regulatory module of guanylate cyclase in atrial natriuretic factor signalling. Biochem.J. 1992;282:533–537. doi: 10.1042/bj2820533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foster DC, Garbers DL. Dual role for adenine nucleotides in the regulation of the atrial natriuretic peptide receptor, guanylyl cyclase-A. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:16311–16318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burczynska B, Duda T, Sharma RK. ATP signaling site in the ARM domain of atrial natriuretic factor receptor guanylate cyclase. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2007;301:193–207. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9400-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Antos LK, Abbey-Hosch SE, Flora DR, Potter LR. ATP-independent activation of natriuretic peptide receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:26928–26932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505648200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antos LK, Potter LR. Adenine nucleotides decrease the apparent Km of endogenous natriuretic peptide receptors for GTP. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E1756–E1763. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00321.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joubert S, Jossart C, McNicoll N, de Lean A. Atrial natriuretic peptide-dependent photolabeling of a regulatory ATP-binding site on the natriuretic peptide receptor-A. FEBS J. 2005;272:5572–5580. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duda T, Yadav P, Jankowska A, Venkataraman V, Sharma RK. Three dimensional atomic model and experimental validation for the ATP-Regulated Module (ARM) of the atrial natriuretic factor receptor guanylate cyclase. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2001;217:165–172. doi: 10.1023/a:1007236917061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma RK, Yadav P, Duda T. Allosteric regulatory step and configuration of the ATP-binding pocket in atrial natriuretic factor receptor guanylate cyclase transduction mechanism. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2001;79:682–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wüthrich K. MOLMOL: A program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graphics. 1996;14:51–55. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sambrook MJ, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Ed. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nambi P, Aiyar NV, Sharma RK. Adrenocorticotropin-dependent particulate guanylate cyclase in rat adrenal and adrenocortical carcinoma: comparison of its properties with soluble guanylate cyclase and its relationship with ACTH-induced steroidogenesis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1982;217:638–646. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(82)90545-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gryczynski I, Wiczk W, Inesi G, Squier T, Lakowicz JR. Characterization of the tryptophan fluorescence from sarcoplasmic reticulum adenosinetriphosphatase by frequency-domain fluorescence spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1989;28:3490–3498. doi: 10.1021/bi00434a051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Demchenko AP, Gryczynski I, Gryczynski Z, Wiczk W, Malak H, Fishman M. Intramolecular dynamics in the environment of the single tryptophan residue in staphylococcal nuclease. Biophys Chem. 1993;48:39–48. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(93)80040-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lakowicz JR, Zelent B, Gryczynski I, Kuśba J, Johnson ML. Distance-dependent fluorescence quenching of tryptophan by acrylamide. Photochem Photobiol. 1994;60:205–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1994.tb05092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lakowicz JR, Kuśba J, Szmacinski H, Johnson ML, Gryczynski I. Distance-dependent fluorescence quenching observed by frequency-domain fluorometry. ChemPhysLett. 1993;206:455–463. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou T, Rosen BP. Tryptophan fluorescence reports nucleotide-induced conformational changes in a domain of the ArsA ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19731–19737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.32.19731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]