Abstract

Background

Guidelines translate best evidence into best practice. A well-crafted guideline promotes quality by reducing healthcare variations, improving diagnostic accuracy, promoting effective therapy, and discouraging ineffective – or potentially harmful – interventions. Despite a plethora of published guidelines, methodology is often poorly defined and varies greatly within and among organizations.

Purpose

This manual describes the principles and practices used successfully by the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery to produce quality-driven, evidence-based guidelines using efficient and transparent methodology for action-ready recommendations with multi-disciplinary applicability. The development process, which allows moving from conception to completion in twelve months, emphasizes a logical sequence of key action statements supported by amplifying text, evidence profiles, and recommendation grades that link action to evidence.

Conclusions

As clinical practice guidelines become more prominent as a key metric of quality healthcare, organizations must develop efficient production strategies that balance rigor and pragmatism. Equally important, clinicians must become savvy in understanding what guidelines are – and are not – and how they are best utilized to improve care. The information in this manual should help clinicians and organizations achieve these goals.

1 INTRODUCTION

If you use or develop clinical practice guidelines this manual will likely be of interest. “There are many paths to the top of the mountain,” suggests an old Chinese proverb, “but the view is always the same.”1 Although many paths lead to guidelines, we offer proven strategies for crafting a valid and action-ready product within twelve months. The driving force is quality improvement with a continuous effort to balance pragmatism with developmental rigor. The end product is a starting point for performance improvement.

This manual builds on an earlier publication2 by American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) to systematize internal guideline development. By following these principles the AAO-HNS published five multidisciplinary guidelines in five years, all within 12 months from conception to completion.3–7 Each guideline presented a fresh opportunity to test and refine prior efforts, necessitating a revised and greatly expanded manual only three years after initial publication. Our new manual not only summarizes this experience, but allows other organizations to assess and adapt the processes.

Our goals in publishing a revised manual are several. First, we sought to provide clinicians with a straightforward explanation of guidelines, considering the increasing prominence of guidelines as a quality metric. Second, we wanted a pragmatic resource, which accurately reflects current practices, to sustain consistent guideline development at the AAO-HNS. Last, we wanted to share our successful development process with the guideline community at-large to encourage an exchange of ideas and to promote best practices.

Guidelines are particularly important when wide regional variations exist in managing a condition. Similarly, the wide variability in guideline methodology, both within and between organizations, is precisely what mandates a systematic approach to guideline development. Despite a plethora of techniques reflected in published guidelines, we could not find a single, comprehensive “how-to” manual with a valid and pragmatic approach that could be readily implemented. This work is offered to address this void.

We thank the AAO-HNS for their trust, support, and flexibility throughout this fruitful collaboration, and sincerely hope that you may also benefit from the experience. We humbly acknowledge that ours is one of many paths to the mountain top, and look forward to further refinement based on reader feedback and ongoing experience.

2 HOW TO USE THIS MANUAL

Throughout the manual we emphasize principles and practices, recognizing that both are needed to translate concepts into action. Principles underlying practices are always stated, to promote conceptual focus and clarity before getting sidetracked with implementation details. Practices are illustrated with examples from prior AAO-HNS guidelines to clarify how we chose to implement a principle, with the understanding that other development groups will need to modify the particulars to fit their organizational structure and resources.

Content that is offset from the remainder of the text is intended to emphasize a concept, insight, or principle, of special note or importance. This also serves to create visual breaks that improve readability, along with tables, bulleted lists, numbered lists, and frequent subheadings.

The following list describes some of the fundamental principles underlying guideline development that are discussed sequentially in this manual:

Medicine and guidelines: why guidelines are an essential for quality care

Understanding guidelines: what makes a guideline useful and valid?

Principles of guideline development: essential steps and processes

Identifying evidence: finding and using best published evidence

Identifying topics: how to prioritize quality improvement opportunities

Understanding key action statements: the backbone of a clear and usable guideline

Understanding evidence profiles: how they promote transparency

Understanding recommendation grades: the link between action and evidence.

Appraising implementability: maximizing the chance to influence clinician behavior

This manual is also intended as a practical resource for use during guideline development. Major sections of the text correspond to the activities involved (Table 1), allowing the user to move from one section to the next as development proceeds. When significant principles apply to an activity they are discussed within, or just before, the relevant section.

Table 1.

Timetable for guideline development

| Month | Activity | Goals |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Planning | Define topic; identify leadership, partner organizations, and working group members |

| 0–1 | Stage 1 literature search | Identify existing guidelines and systematic reviews |

| 2 | Conference call #1 | Define purpose, timeline, and scope; discuss conflicts of interest; plan stage 2 literature search |

| 2–3 | Stage 2 literature search | Identify randomized controlled trials |

| 3 | Conference call #2 | Refine scope and definitions; generate a draft topic list of opportunities for quality improvement |

| 4 | In-person meeting #1 | Construct a “straw man” guideline of key action statements based on topic priorities; outline supporting text for key statements; discuss writing assignments |

| 4–5 | Stage 3 literature search | Identifying best evidence to facilitate writing assignments for specific action statements |

| 4–5 | Writing assignments | Write the amplifying text for key action statements; chair collates into guideline draft |

| 6 | In-person meeting #2 | Refine the key, action statements; review amplifying text, assign evidence profiles; grade recommendations |

| 6–7 | Writing assignments | Revise and polish the draft guideline |

| 7 | Appraising draft guideline implementability |

Appraisal of draft guideline clarity, quality, and ability to be successfully implemented |

| 8 | Conference call #3 | Review guideline appraisal report; remedy deficiencies |

| 9 | Pre-release peer review | External review of draft guideline by representatives of target audience and practice settings |

| 10 | Organizational board review | Internal review and approval of final guideline by the board or directors of the sponsoring organization(s) |

| 11–12 | Publication | Final guideline submitted for publication |

We have tried to make this manual as reader-friendly as possible, but how to best approach the material will depend upon one’s background and perspective. Individuals and organizations involved in guideline development comprise a diverse audience that may benefit from the material in the manual in several ways:

Organizations new to guideline development will benefit from understanding the nuances and complexities of guideline creation, and may consider using the process outlined as a starting point for their own endeavors.

Organizations with an established guideline development process may wish to compare their current processes to those described here, potentially identifying areas for improved quality, efficiency, or both.

Members of guideline panels or working groups can derive greater insight and understanding of development methodology, allowing to them to contribute most effectively as an author or participant.

Staff supporting guideline development will find practical suggestions on staying focused and efficient, and may consider using, or adapting, the manual as a template for their own processes.

Guideline users are perhaps even more diverse than guideline developers. Whereas most guideline users do not need, or want, detailed information on methodology, some understanding is necessary to interpret and utilize existing products:

Organizations that use guidelines will gain greater insight into the guideline development process, understanding what makes a guideline valid and action-ready, and what attributes should be sought when critically assessing a guideline’s potential value.

Organizations that conduct systematic reviews can interact most effectively with guideline developers if they understand the process of moving from evidence to action, how systematic reviews facilitate these efforts, and how recommendations are made when evidence is absent or of low quality.

Clinicians with an interest in guidelines can use them most effectively if they understand how they are developed, what are current best practices, and how guidelines should – and should not – be used to influence clinical care.

Consumers or consumer groups that have identified guidelines of interest will be better able to assess quality, and select among multiple guidelines of varying quality, if they appreciate the processes involved in creating valid guidelines.

3 MEDICINE AND GUIDELINES

The Institute of Medicine has identified three crucial tasks for a national system to identify highly effective health care services: priority setting, evidence review, and developing recommendations (guidelines).8 The last task – creating clinical practice guidelines – is perhaps the most challenging, because methodology continues to evolve, the quality and relevance of available evidence is highly variable, and evidence gaps mandate valid processes for incorporating expert consensus.

Guidelines help clinicians translate best evidence into best practice. A well-crafted guideline promotes quality by reducing healthcare variations, improving diagnostic accuracy, promoting effective therapy, and discouraging ineffective – or potentially harmful – interventions.

This manual offers one approach to efficient guideline development based on experience of the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) and the Yale Center for Medical Informatics. The AAO-HNS and associated Foundation sponsor continuing medical education, professional meetings, scientific research, and practice management guidance for more than 13,000 ear, nose, and throat specialists in the United States and abroad. Since 2004 the AAO-HNS has devoted substantial resources to creating and publishing guidelines that improve quality of care in diverse clinical practice environments.

Despite an immediate need for valid, action-ready guidelines, many barriers exist. Published guidelines, although numerous, are often poorly suited to assess performance or influence care, because recommendations do not translate into measurable actions or activities. Moreover, the development process is generally inefficient and highly complex, requiring, on average, about 2 to 3 years per guideline. Gaps in the evidence base for many important issues typically preclude guideline recommendations based on evidence, even when quality concerns or practice variations mandate urgent action.

One solution is to produce quality-driven, evidence-based guidelines using efficient and transparent methodology for action-ready recommendations with multi-disciplinary applicability:

QUALITY-DRIVEN means placing quality improvement at the forefront of guideline development, using current best evidence and multidisciplinary consensus to prioritize recommendations. Selection of key action statements is driven by opportunities to promote best practices, reduce variations in care, and minimize inappropriate care or resource utilization.

EVIDENCE-BASED means supporting all decisions with the best available research evidence identified through systematic literature review. An absence of high quality evidence (e.g., randomized trials), however, does not preclude a structured use of expert consensus if an important quality concern needs to be addressed.

EFFICIENT guidelines make maximum use of available resources to create a timely product, ideally moving from conception to publication within 12 to 18 months.

TRANSPARENT METHODOLOGY is explicit, reproducible, and applied consistently so guideline users can link recommendations to the corresponding the level of evidence, benefit-harm-cost relationship, and the roles of values and patient preferences in decision making.

ACTION-READY recommendations tell providers what to do, to whom, under what specific circumstance, using unambiguous language that facilitates implementation and measurement.

MULTI-DISCIPLINARY validity and applicability means that all stakeholders (e.g., primary care, specialists, allied health, nursing, consumers) are part of the development and implementation processes.

The utility of a guideline depends highly on its transparency, which makes clear the purpose and basis of recommendations to end users. Transparency mandates disclosure of competing interests by authors, explicit statements about the reasons for developing a policy, and explanation of contributing factors are weighed.9

AAO-HNS guidelines prescribe recommendations in key action statements followed by amplifying text. All guideline action statements should ideally be supported by evidence profiles that summarize clearly the decision-making process in terms of aggregate evidence quality, harm-benefit assessment, development group values, and the role of patient preference. Evidence profiles are discussed fully later in this manual.

4 UNDERSTANDING GUIDELINES

As defined by the Institute of Medicine, clinical practice guidelines are “systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances.”10 Despite increasing acceptance of an evidence-based approach to clinical decision-making, much clinical practice is still not based on the best available evidence. Guidelines are one way of implementing evidence into practice.11 They can serve as a guide to best practices, a framework for clinical decision-making, and a benchmark for evaluating performance.

Guidelines benefit patients through better outcomes, fewer ineffective interventions, greater consistency of care, and by creating secondary implementation materials (pamphlets, videos, etc.). Clinicians can use guidelines to make better decisions, initiate quality improvement efforts, prioritize new research initiatives, and support coverage or reimbursement for appropriate services. Conversely a flawed guideline could significantly harm both patients and clinicians, thereby mandating sound methodology as a basis for guideline development.12

Simply inserting the word “guideline” in the title of a document does not make it so. Many review articles, consensus statements, practice parameters, and policy recommendations are mistakenly labeled as “guidelines,” even though they do not possess the methodologic rigor to warrant such a designation. A real guideline is one that fulfills all or most of the specific criteria defined below.

The Appraisal of Guidelines Research & Evaluation (AGREE) instrument is a widely used generic measure of guideline quality.13 Quality guidelines are characterized by the following attributes:

EXPLICIT SCOPE AND PURPOSE: Specific descriptions are given of the overall guideline objective(s), the clinical question(s) covered, and the patients to whom the guideline is meant to apply.

STAKEHOLDER INVOLVEMENT: The development group includes individuals from all relevant professional groups; patients’ views and preferences are sought; target users are clearly defined; and the guideline has been piloted among target users.

RIGOR OF DEVELOPMENT: Systematic methods are used to search for and select evidence; methods for formulating recommendations are clearly described; recommendations take into account health benefits, side effects, and risks; recommendations are linked explicitly to supporting evidence; the guideline is externally reviewed by experts prior to publication; and a procedure for updating the guideline is provided.

CLARITY OF PRESENTATION: Recommendations are specific and unambiguous; different options for management are clearly presented; key recommendations are easily identifiable; and the guideline is supported with tools for application.

APPLICABILITY: Potential organizational barriers in applying the recommendations are discussed; potential cost implications are considered; and the guideline presents key review criteria for monitoring and/or audit purposes.

EDITORIAL INDEPENDENCE: Externally funded guidelines should state explicitly that views and interests of the funding body have not influenced final recommendations; all group members should explicitly state potential conflicts of interest, which are recorded in the guideline.

The Conference on Guideline Standardization (COGS) Checklist is another tool that specifies characteristics of a valid and usable clinical practice guideline.14 In contrast to the AGREE instrument, which assesses guidelines after completion, the COGS checklist can be used during development to improve quality. The 18 characteristics in the COGS checklist are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of a quality clinical practice guideline

| Topic | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Overview material | Structured abstract including release date, status, print and electronic sources |

| 2. Focus | Primary disease/condition and intervention/service/technology |

| 3. Goal | Goal guideline is expected to achieve, including rationale for topic |

| 4. Users/setting | Intended users of the guideline and practice settings |

| 5. Target population | Patient population eligible for guideline plus exclusion criteria |

| 6. Developer | Organization(s) responsible for development plus author names/credentials |

| 7. Funding source | Who sponsored development, what was role, what are conflicts of interest |

| 8. Evidence collection | Literature search methods, including dates, databases, and filter criteria |

| 9. Grading criteria | Method for grading recommendation strength and rating evidence quality |

| 10. Evidence synthesis | How evidence was used to create recommendations |

| 11. Prerelease review | How guideline developer reviewed and/or tested guidelines prior to release |

| 12. Update plan | Expiration date for guideline and plans for updating |

| 13. Definitions | Defines unfamiliar terms and those critical to correct application |

| 14. Recommendations and rationale |

Recommended actions are stated precisely with specific circumstances under which to perform them, and explicit linkage to supporting evidence |

| 15. Benefits & harms | Potential benefits and risks associated with recommendations |

| 16. Patient preferences | Role in decisions with substantial personal choice or values |

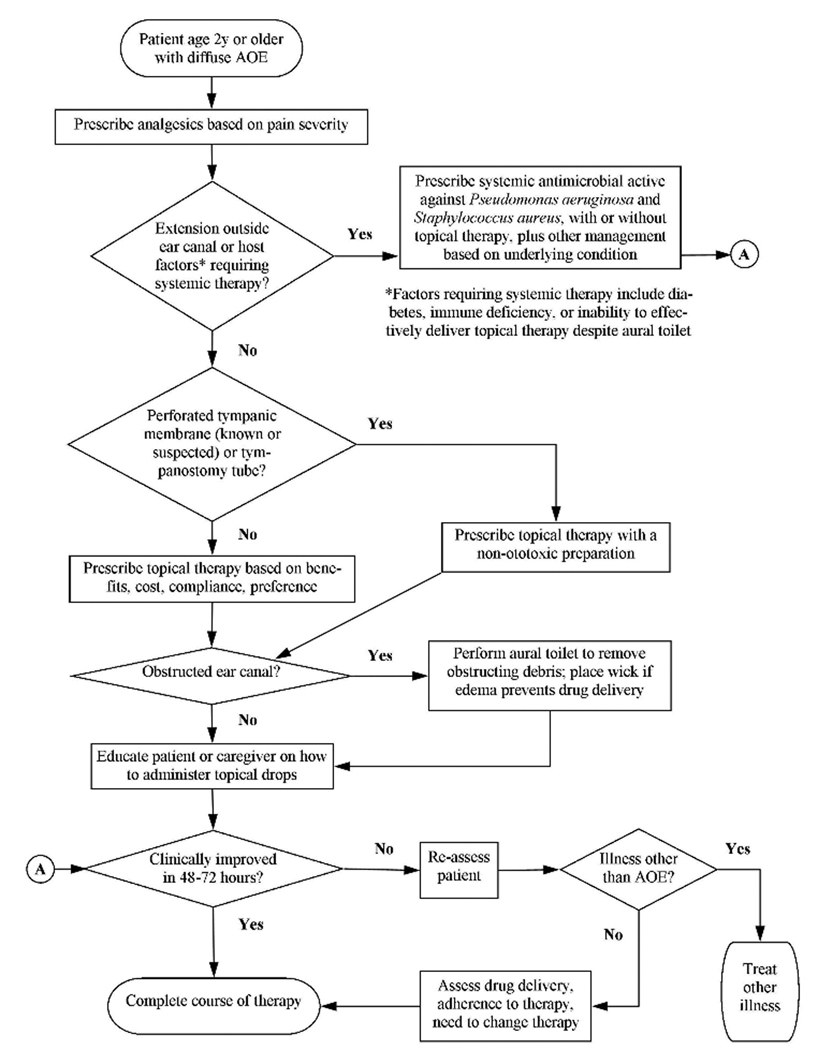

| 17. Algorithm | Graphical description of the stages and decisions in clinical care |

| 18. Implementation | Anticipated barriers to implementation, auxiliary materials, review criteria |

Adapted from the Conference on Guideline Standardization.14

Guidelines meeting certain quality standards are included in the National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC) database, an initiative of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality NGC inclusion criteria are:15

The clinical practice guideline contains systematically developed statements that include recommendations, strategies, or information that assists physicians and/or other health care practitioners and patients make decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances.

The clinical practice guideline was produced under the auspices of medical specialty associations; relevant professional societies, public or private organizations, government agencies at the federal, state, or local level; or health care organizations or plans. A clinical practice guideline developed and issued by an individual not officially sponsored or supported by one of the above types of organizations does not meet the inclusion criteria for NGC.

Corroborating documentation can be produced and verified that a systematic literature search and review of existing scientific evidence published in peer reviewed journals was performed during the guideline development. A guideline is not excluded from NGC if corroborating documentation can be produced and verified detailing specific gaps in scientific evidence for some of the guideline's recommendations.

The full text guideline is available upon request in print or electronic format (for free or for a fee), in the English language. The guideline is current and the most recent version produced. Documented evidence can be produced or verified that the guideline was developed, reviewed, or revised within the last five years.

Equally important to understanding what guidelines are is a clear appreciation of what guidelines are not. Without this perspective clinicians may become apprehensive about the impact of guidelines on their lives, and organizations may apply guidelines to situations they were never intended.

Guidelines are not reimbursement policies

Guidelines are not performance measures

Guidelines are not legal precedents

Guidelines are not measures of certification or licensing

Guidelines are not for provider selection or public reporting

Guidelines are not recipes for cookbook medicine

Guidelines are never intended to supersede professional judgment; rather they may be viewed as a relative constraint on individual clinician discretion in a particular clinical circumstance.16 Clinicians should always act and decide in a way that they believe will best serve their patients’ interests and needs, regardless of guideline recommendations. Guidelines simply represent the best judgment of a team of experienced clinicians and methodologists addressing the scientific evidence for a particular topic.

Guidelines differ from systematic reviews and evidence reports that identify and combine studies using explicit methods to reduce bias, but do not typically define appropriate actions or incorporate values. In contrast, a guideline uses information from evidence reviews and other sources to make specific recommendations by considering values and linking the strength of recommendation to the quality of evidence.

Last, evidence-based clinical practice guidelines are not intended for cost control or healthcare rationing. Guidelines seek to produce optimal health outcomes for patients, minimize harm, and reduce inappropriate variations in clinical care. Whereas some of these outcomes may also reduce costs, financial benefits alone are generally not the main focus of an evidence-based clinical practice guideline.

5 PRINCIPLES OF GUIDELINE DEVELOPMENT

Without substantial advance planning, guideline development is likely to be biased and inefficient. Moreover, an a priori protocol is mandatory to ensure attention to the COGS and AGREE quality standards. Based on literature review and direct experience in North America and the United Kingdom, Shekelle and colleagues17 concluded that five steps are involved in the initial development of an evidence-based guideline:

Identifying and refining the subject area

Convening and running guideline development groups

Assessing evidence identified by systematic literature review

Translating evidence into recommendations

Subjecting the guideline to external review

Turner and co-workers11 compared approaches to guideline development in six handbooks from the Council of Europe, World Health Organization, and from national organizations in Australia, Scotland, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. All handbooks agreed that key aspects of development included a multidisciplinary panel, consumer involvement, identifying clinical questions or problems, systemically reviewing and appraising the literature, a process for drafting recommendations, external consultation and review, and planned updating.

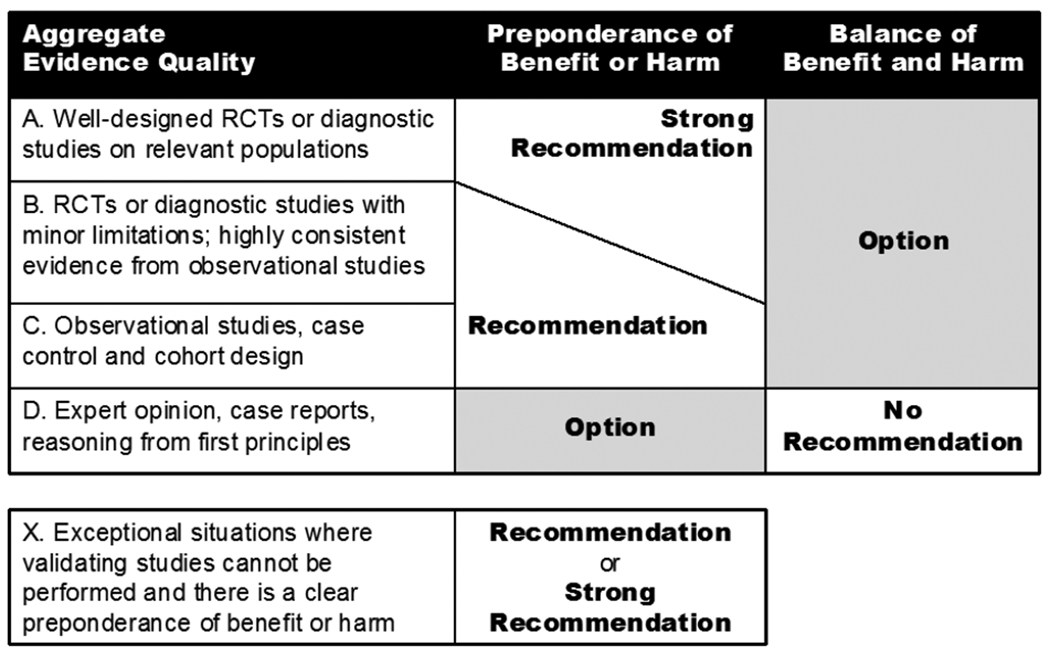

Guyatt and colleagues18 have focused on grading evidence quality and recommendation strength in guidelines, emphasizing that both are separate and distinct processes essential to validity. An optimal grading system is characterized by simplicity and transparency for the clinician consumer, sufficient (but not too many) categories, explicitness of methodology for guideline developers, simplicity for guideline developers, consistency with general trends in grading systems, and an explicit approach to different levels of evidence for different outcomes.

The guideline development process described in this manual addresses the above issues, yet strives for a balance between rigor and pragmatism that maintains efficiency.

Efficiency is critical in guideline development, because moving from planning to completion in about 12 months helps avoid a situation in which new evidence continues to appear. With an efficient protocol in place an organization can stagger guidelines under simultaneous development to result in a finished product every 6 months (depending on resources). The timeline in Table 1 has been developed to ensure rigor in development while promoting efficiency. The remainder of this manual describes the steps listed in Table 1 in terms of general concepts and specific suggestions based on prior experience.

6 PLANNING

6.1 Define topic

Guidelines can be developed for a wide range of topics, including conditions (sinusitis, ear infections), procedures (tonsillectomy, tympanostomy tubes), and signs or symptoms (cough, hoarseness). Topics selected for guideline development should be high-priority and feasible.

High-priority topics have the potential for evidence-based practice to improve health outcomes, minimize undesirable variations in care, and reduce the burden of disease and health disparities. The Institute of Medicine has identified the following priority setting criteria as common to most international guideline development groups:8

DISEASE BURDEN. Extent of disability, morbidity, or mortality imposed by a condition, including effects on patients, families, communities, and society overall.

CONTROVERSY. Controversy or uncertainty around the topic and supporting data.

COST. Economic cost associated with the condition, procedure, treatment, or technology related to the number of people needing care, unit cost of care, or indirect costs.

NEW EVIDENCE. New evidence with the potential to change conclusions from prior assessments.

POTENTIAL IMPACT. Potential to improve health outcomes and quality of life; improve decision making for patient or provider

PUBLIC OR PROVIDER INTEREST. Consumers, patients, clinicians, payers, and others want an assessment to inform decision making.

VARIATIONS IN CARE. Potential to reduce unexplained variations in prevention, diagnosis, or treatment; the current use is outside the parameters of clinical evidence.

Feasible topics have a sufficient base of high quality published evidence (ideally randomized, controlled trials) to drive guideline development, have one or more existing systematic reviews or meta-analyses already published on relevant issues, and have relatively clear definitions of the condition or procedure under consideration.

A steering committee that includes organizational leadership and broad stakeholder representation can help identify, prioritize, and refine guideline topics. Diversity of expertise and perspective helps minimize bias caused by conflicts of interests.

The AAO-HNS convened the Guideline Development Task Force as a steering committee for developing evidence-based guidelines and related knowledge products.19 The task force includes representatives of all sub-specialty groups within otolaryngology and of all relevant internal Academy groups, including research, patient safety, quality improvement, board of governors, and evidence-based medicine. Topics are solicited with a standardized form, based on principles outlined above, then presented to the task force for ranking and prioritization.

6.2 Convene the guideline working group

Perhaps the most important decision in creating a successful guideline relates to composition of the working group. A group size of 15–20 members encourages diversity and efficiency yet is small enough to avoid delays and redundancy.

The group should consist of the (1) chair and two assistant chairs, (2) staff lead and assistant, (3) technical consultant, (4) content experts, (5) stakeholders from all relevant disciplines, including nursing, primary care, and allied health, and (6) a consumer representative. The roles and responsibilities of group members are outlined in the sections that follow.

6.3 Identify organizational leadership

A staff lead is assigned as the primary liaison for the group, with one or more assistants who have the dual responsibility of supporting the lead and learning the process so they may serve as a future lead. Qualifications for staff lead include service as an assistant staff lead on a prior guideline panel, experience conducting literature searches and using a citation database, and a basic understanding of study design, medical terminology, and levels of evidence.

Specific responsibilities of the staff lead and assistants include:

Conducting a preliminary search to assess topic feasibility

Identifying guideline group members by working with internal leadership and relevant external organizations

Scheduling and handling logistics for all conference calls and group meetings

Working with the chair to create agendas and pre-distribute supporting materials

Coordinating literature searches, organizing search results, and obtaining full-text articles

Appraising the guideline for implementability using predetermined methods

Identifying external peer reviewers and collating comments for distribution to the chair

Assisting the chair in developing and obtaining permissions for tables and figures

Proofreading the guideline final draft, including checks for grammar and spelling

Submitting a summary of key action statements and supporting evidence profiles for review and approval by the organizational board of directors

Assisting the chair in formatting the final document for publication submission

Obtaining copyright transfer and financial disclosure forms from working group members

A technical consultant is assigned to ensure that the working group adheres to methodologic standards and protocols endorsed by the organization, and to serve as a facilitator who supports the chair during conference calls and meetings. The technical consultant should be fluent with guideline methodology, understand the process of systematic review, and have direct experience prior guidelines developed by the organization.

Developing valid guidelines is not intuitive, but is an acquired skill that is independent from clinical expertise and accomplishment. Whereas an explicit and comprehensive manual aids the process, it cannot substitute for hands-on experience.

6.4 Identify clinical leadership

A chair should be identified to lead the group in developing the guideline and to work with the technical consultant and staff lead to ensure adherence to methodologic standards. The chair also facilitates the interpersonal aspects of the group processes, so the members work in a spirit of collaboration with balanced contribution from all members.

Specific responsibilities of the chair include:20–21

Assisting the staff in planning conference calls and meetings

Steering discussions according to the agenda

Encouraging all members to contribute to discussions and activities of the group

Remaining aware and constantly attentive to small group processes, including how the group interacts, communicates, and makes decisions

Establishing a climate of trust and mutual respect among members while remaining sensitive to preexisting inter-professional tensions and hierarchies

Maintaining a unified group discussion free of sub-conversations and dominance

Encouraging constructive debate without forcing agreement

Winding up repetitive debate and disagreements through careful negotiation

Summarizing main points and key decisions of a debate

Delegating writing assignments and integrating completed assignments and group feedback into the draft guideline

The chair is appointed by a selection panel that includes organizational leadership, steering committee representation, the guideline staff lead, and the technical consultant. An ideal chair should be efficient and motivated, have demonstrated leadership ability, have prior experience with evidence-based guideline development, have demonstrated skills in scientific writing, and be fluent with using the internet, e-mail, and e-mail attachments. Candidates for chair will be asked to submit a curriculum vitae and declaration of competing interests, and to confirm that they understand and accept the substantial time commitment involved.

The chair should ideally not be a content expert for the guideline topic, but should be familiar with the scientific literature and management of the clinical condition. Content experts are usually abundant in an organization and can be readily added to the working group to fill in knowledge gaps. Conversely, the chair should be an impartial leader who stimulates discussion, not an advocate who injects their own opinions.17

One or two assistant chairs should be identified who will be asked to chair the next guideline development effort. To maintain a pipeline of guideline projects, a continuing source of leadership for upcoming projects is needed. The best way to groom new chairs is to have them serve on one or two prior guideline groups to learn methodology and expectations early on. An ideal assistant chair should have experience with evidence-based medicine, but does not necessarily need prior guideline development experience.

The chair is ultimately responsible for moving along the guideline process and keeping the group focused and task oriented. Having more than one chair is inadvisable, because responsibilities can be easily shifted and diffused. Instead, the structure should include one chair and one or more assistant-chairs, as noted above.

6.5 Identify partner organizations

Guideline development panels should include individuals from a range of relevant stakeholder groups to minimize bias. Multidisciplinary participation helps identify and evaluate all relevant evidence, builds support among the intended guideline users, and increases the chances of addressing practical problems related to implementation.10

Many guidelines warrant input from nursing, consumers, and primary care clinicians. Based on the target population and setting, the working group may include internists, pediatricians, geriatricians, family practitioners, and emergency medicine physicians. Additional specialty clinicians are recruited as dictated by the specific topic or condition under study. Allied health professions are similarly recruited, and may include audiologists, physical therapists, speech-language pathologists, and others.

An excellent source of consumer participants for guideline development is Consumers United for Evidence-based Healthcare (CUE), a national coalition of health and consumer advocacy organizations, which empowers consumers through critical appraisal of articles, guidelines, and systematic reviews.22 CUE is a project of the U.S. Cochrane Center and works closely with the Cochrane Consumer Network.

If another discipline is to be a full partner in developing the guideline, they are approached early to secure interest and cooperation. Alternatively, working group members can be selected to represent their “discipline,” not their “organization.” In this model a pediatrician member of the working group would provide essential input for pediatrics as a discipline, but would not necessarily represent the American Academy of Pediatrics or imply their specific endorsement of the resulting guideline.

6.6 Identify guideline working group members

In deciding what disciplines other than otolaryngology to include in guideline development, a useful approach is to ensure that every discipline or organization that would be involved with implementation, including consumers, has a voice at the table. This will nearly always include one or more primary care clinicians, since invariably they will be involved in counseling the patient and coordinating care with the specialist. Representatives of all relevant medical specialties other than otolaryngology must also be considered.

A single specialty group will reach different conclusions than a multidisciplinary group when presented with the same evidence.17 Individuals from a single discipline are often biased towards procedures in which they have a vested interest. Involving multiple disciplines tends to balance bias and produce more valid guidelines.8

Potential members of the working group can be identified by organizational leadership, partner organizations, the working group chair, and the staff liaisons. An understanding of evidence-based medicine is desirable. Individuals are invited as representatives of their field or discipline, but need not be content experts for the guideline topic. Content experts should be a minority voice on the working group to limit bias.

Specific responsibilities of the working group members include:

Participating in all conference calls

Attending all meetings with a commitment to teamwork and clear communication

Reading all relevant materials and providing constructive comments and feedback during and between meetings

Checking and responding to e-mails on a regular basis

Completing personal assignments to meet deadlines

Maintaining confidentiality

Disclosing fully any potential conflicts or interest

The importance of choosing an appropriate working group cannot be overemphasized. This is called a “working” group for a reason: producing a guideline requires substantial time and effort. All members have a responsibility to other participants to behave with integrity, commitment, and a fully professional demeanor.

Despite the upfront commitment of all working group members to participate fully in guideline development, conflicts or unexpected circumstances may arise that threaten validity if an important discipline is not represented. Therefore, certain disciplines, which include primary care and selected others depending on the topic, should be represented by two group members to ensure representation.

6.7 Compile contact information grid

The staff lead should compile a grid of contact information for all working group members and organizational representatives. Included in the grid should be (1) name and degrees, (2) working group role, (3) organizational affiliation, (4) clinical and academic titles, (5) mailing address, (6) disclosed conflicts of interests, and (7) contact information.

6.8 Conflict of interest disclosure

A conflict of interest exists when a participant or the participant’s institution has financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that may inappropriately influence (bias) his or her actions.

Despite good intentions, it is not appropriate for individuals to decide if a particular relationship causes conflict; their role is to declare, not interpret. The group as a whole must ultimately determine if a conflict may result in bias, and whether or not the degree of conflict excludes the individual from participating in the entire guideline or selected sections.

Financial relationships are easily identifiable, but conflicts can also occur because of personal relationships, academic competition, or intellectual passion. Examples of financial conflicts include employment, consultancies, stock ownership, honoraria, paid expert testimony, patents or patent applications, and travel grants. Full disclosure is advised regardless of whether the participant considers the relationship relevant to the guideline content.

The contact and disclosure list should be distributed to all members for verification and should be updated, as needed, during guideline development and prior to publication.

6.9 Determine dates for conference calls and meetings

Adhering to a predetermined, specific timeline allows publication of the guideline within 18 months. Arranging dates for conference calls and meetings is particularly difficult when dealing with individuals representing multiple organizations and disciplines. Therefore, it is critical to plan early in the process. Events are planned using the timetable in Table 1

Conference call #1 takes place in month 2

Conference call #2 takes place about 4 weeks later, in month 3

In-person meeting #1 takes place about 4 weeks later, in month 4

In-person meeting #2 takes place about 6–8 weeks later, in month 6

Conference calls are often most feasible if planned to start at 8:00 p.m. Eastern Time. Calls should be generally scheduled for 2 hours. In-person meetings can begin at noon with a light working lunch to allow attendees to fly in the same morning. Similarly, they can end by noon the next day to allow a return flight the same day. A group dinner should be planned the first day. A convenient schedule is to begin on either Friday or Sunday, and end the next day.

The staff lead prepares a grid of potential dates for the calls and meetings. The grid is circulated by electronic mail to the chair, assistant chair, and technical consultant to determine to determine available dates for the first two conference calls. For the in-person meetings and future conference calls, the grid may be circulated to the entire working group to assess availability. There will clearly be a need for compromise by some group members, since the odds of finding dates agreeable to all are extremely low. Group members must commit to attending these meetings at the start.

The importance of having all working group members participate in all conference calls and attend all meetings cannot be overemphasized. Advance planning is the best guarantee of success, since maximal time is available for group members to adjust their schedules as needed and block out event dates in their calendars. If a group member cannot make this commitment, an alternate should be found as soon as possible.

7 IDENTIFYING EVIDENCE

7.1 Purpose

The validity of an evidence-based guideline depends in large part on an unbiased and comprehensive literature search. The goal is to locate the best evidence from all relevant sources, producing a comprehensive body of evidence that will allow clinical questions to be answered and highlight gaps in the evidence base where formal consensus methods may be needed.20

7.2 The role of evidence in guideline development

Although identifying evidence is essential for guideline development, we suggest the proper role is as supporting cast, not protagonist:

EVIDENCE AS PROTAGONIST MODEL. Many organizations publish “practice parameters” or “evidence-based reviews” as their primary quality products, having the literature search take center stage, with exhaustive evidence tables or textual discussions that rank and summarize citations. If recommendations are made, the strength is linked directly to level of evidence, sometimes with a threshold number of minimum studies of a specific level or combinations thereof, rather than an explicit consideration of benefits, risks, harms, and costs. Recommendations have uncertain validity because there is no systematic process to incorporate costs, harms, adverse events, uncertainty, vagueness, working group values, or patient preference. Moreover, recommendations become difficult to make when evidence gaps exist.

EVIDENCE AS SUPPORTING CAST MODEL. An alternative approach, described in this manual, is to drive guideline development with considerations of quality improvement, using the literature search as one of many factors to translate evidence into action. In this model the ratio of benefits to harms and costs is considered equal to, or even greater than, level of evidence in formulating recommendations. Evidence profiles are used to state explicitly how values, patient preferences, and conflicts of interest were incorporated. Recommendations are still possible with evidence gaps, but strength will be limited.

Although it is tempting to exclude topics with limited evidence from guideline development, it is precisely such topics that benefit most from inclusion because of uncertainty and conflicting opinions. Even if evidence is limited recommendations are still possible if well-document benefit or harm is identified.

Using expert opinion or consensus to fill evidence gaps is entirely appropriate, provided this basis is explicit and transparent to the critical reader.9 Discussing topics with limited evidence allows guideline developers to highlight future research needs, with critical suggestions on how to best fill existing gaps. The guideline as a whole, however, should focus on topics with high quality evidence and avoid overreliance on expert opinion as a primary decision-making strategy.23

7.3 Literature search stages

Similar to the National Institute of Clinical Excellence,20 we have found that searching is an iterative process that is best implemented in three stages. The stages correspond to different phases of guideline development, and are discussed in detail at the appropriate point in the manual. The three stages of searching (Table 1) can be briefly summarized as:

Identifying systematic reviews and clinical practice guidelines, performed before the first conference call.

Identifying randomized controlled trials, performed before the second conference call.

Identifying supplementary literature, performed after the first in-person meeting.

All search stages must be documented for transparency and reproducibility. Specific considerations include databases, time periods, key words, subject headings, language restrictions, use of gray literature (e.g., symposium proceedings), and selection criteria, such as filters, algorithms, or inclusion and exclusion criteria. A balance of pragmatism and rigor is required to avoid delays in the development process.

7.4 Evidence quality assessment

Simply identifying reviews, guidelines, and randomized trials does not ensure quality, and basing decisions on research with weak design or flawed methodology may yield biased or invalid conclusions. Therefore, to filter out potentially biased or poorly conducted studies, quality assessment must be performed as part of identifying evidence. Suggestions for assessing reviews, guidelines, and randomized trials are presented later in the manual when the related search stage is discussed.

7.5 Performing systematic review and meta-analysis

An organization may find it necessary to perform a systematic review as part of guideline development if there are no published reviews, or if existing reviews are outdated or of poor quality. Systematic review is a rigorous and complex undertaking, which often requires additional expertise, resources, and staff support.

All systematic reviews should be conducted using a priori protocols that adhere to standards for the conduct and reporting of meta-analyses, as suggested in the QUOROM statement for randomized trials24 and the MOOSE statement for observational studies.25 Systematic reviews can be used to define natural history using placebo group outcomes and the absolute or comparative efficacy of interventions.26–27

7.6 Key points to remember

Identifying evidence involves a three stage literature search, with different stages occurring at different times in the development process

The literature search supports guideline development not vice versa

All aspects of searching must be documented for transparency and reproducibility

Constant vigilance is required to balance rigor vs. pragmatism so that guideline development is not stalled or delayed because of overly complex search strategies

8 STAGE 1 LITERATURE SEARCH

8.1 Purpose

The stage 1 search establishes a foundation for the first working group conference call by identifying existing systematic reviews and practice guidelines related to the current topic. This provides important on perspective on what has already been accomplished, what areas of controversy exist, how robust the evidence based is to support guideline development, and where the greatest opportunities lie for improving upon the existing knowledge base.

The stage 1 search is coordinated by the staff lead before the first working group conference call using parameters defined by the chair and technical consultant. Search results are reviewed by the chair to eliminate irrelevant items. A summary grid is compiled and full text files are obtained for distribution to the working group.

8.2 Identifying systematic reviews

Systematic reviews will greatly facilitate guideline development because they identify and synthesize evidence in a format that is readily usable by the working group. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are found by:

identifying Cochrane Reviews and Protocols via the Cochrane Collaboration website (www.cochrane.org) and by searching the Cochrane Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE);

locating evidence reports sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (www.ahrq.gov), which are often developed to support guideline development and may contain useful evidence tables, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses;

searching standard databases – MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) – using “systematic review” or “meta-analysis” as a publication type or text word in the title or abstract;

using search filters of known validity for identifying systematic reviews;28 and

searching Clinical Evidence available from the BMJ publishing group (www.clinicalevidence.bmj.com).

8.3 Identifying clinical practice guidelines

Clinical practice guidelines may already exist for the topic under consideration, but do not preclude further guideline development. Existing guidelines may be outdated or may not have been developed with the methodologic rigor or relevancy that is currently sought. These documents, however, are a useful starting point for group discussions. Clinical practice guidelines can be identified by:

searching the National Guidelines Clearinghouse (www.guideline.gov), an initiative of AHRQ that serves as a public resource for evidence-based guidelines;

searching the database maintained by the Guidelines International Network (www.g-i-n.net), which includes guidelines, evidence reports, and systematic reviews; and

searching standard electronic databases for “guideline” or “practice parameter” as a text word in the title or abstract.

8.4 Assessing quality

Systematic reviews published by the Cochrane Collaboration or government agencies (AHRQ) are typically of high methodologic quality and may not require further assessment. Conversely, reviews authored by individuals or other organizations are highly variable in rigor and quality. Minimum quality criteria for systematic reviews might include (a) an a priori, hypothesis driven protocol, (b) explicit and systematic literature search, (c) validated data extraction from source articles, (d) data pooling with standard statistical techniques, and (e) tabular presentation of results with graphical summaries.

Clinical practice guidelines are highly variable in quality regardless of origin. Minimum quality criteria might include (a) explicit scope and purpose, (b) multi-disciplinary stakeholder involvement, (c) systematic literature review, (d) explicit system for ranking evidence, and (e) explicit system for linking evidence to recommendations.

9 CONFERENCE CALL #1: DEFINING SCOPE

9.1 Purpose

The first conference call (Table 2) sets the stage for guideline development by introducing working group members, defining the guideline timeline and scope, discussing conflicts of interest, and planning for the stage 2 literature search. The call is planned to last 120 minutes and may be recorded for future reference.

The staff lead records minutes of the call, for dissemination and review by the group after the call concludes. The main purpose is to document process, workflow, and decisions made, thereby avoiding the discussion of settled controversies. The group chair takes additional notes during the call to record ideas, concepts, definitions, and key phrases that may later prove difficult to reproduce or remember.

9.2 Pre-distribute electronic materials

Documents should be distributed by e-mail prior to the conference call for review by participants before the call. Materials specific to the guideline that should be distributed include:

Agenda for the conference call

Working group contact information grid with conflict of interest disclosures

Summary grid of relevant systematic reviews and guidelines identified in the Stage 1 literature search

General materials that should be distributed include:

A copy of one or more recently published guidelines from the sponsoring organization to serve as a model of how the finished product will look. Suggested guidelines sponsored by the AAO-HNS include otitis media with effusion,29 acute otitis externa,3 adult sinusitis,4 cerumen impaction,5 and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.6

Reporting checklist from the Conference on Guideline Standardization (COGS)14

Article by Choudhry and co-workers30 about conflict of interest disclosure

9.3 Review contact information, titles, organizations

Group members should review contact information and titles for accuracy. Group members should briefly introduce themselves, including their areas of expertise and experience in developing prior guidelines and their role in the workgroup. The need for any additional group members should be discussed, taking care to be sure that all relevant disciplines are adequately represented.

9.4 Introduce purpose, methodology, timeline

The purpose of sponsoring organization(s) in developing the guideline should be specified, and can be revised and updated as development proceeds. The purpose can often be divided into two distinct, but related components:

objective, i.e., general goals that implementation of the guideline are intended to bring about and

rationale, i.e., reasons for developing recommendations including why the guideline is needed (e.g., evidence of practice variation or inappropriate practice).

Here is an example of how purpose was stated in the AAO-HNS guideline on acute otitis externa: “The primary purpose of this guideline is to promote appropriate use of oral and topical antimicrobials for diffuse acute otitis externa and to highlight the need for adequate pain relief. Additional goals are to make possible an acute otitis externa performance measure and to make clinicians aware of modifying factors that can or may alter management (e.g., diabetes, immune compromised state, prior radiotherapy, tympanostomy tube, non-intact tympanic membrane).”3

As another example, consider this statement of purpose from the AAO-HNS guideline on adult sinusitis: “The primary purpose of this guideline is to improve diagnostic accuracy for adult rhinosinusitis, reduce inappropriate antibiotic use, reduce inappropriate use of radiographic imaging, and promote appropriate use of ancillary tests that include nasal endoscopy, computed tomography, and testing for allergy and immune function.”4

After the guideline purpose has been discussed, the consultant provides a very brief overview of development methodology. Points worthy of emphasis include:

The guideline will meet or exceed reporting standards defined by the COGS statement and AGREE instrument13,14

The guideline will be developed using an explicit, evidence-based process that incorporates group values and patient preferences

The process will involve three conference calls and two in-person meetings

The goal is to produce a document with key action statements for clinicians, highlighting the key areas of behavior change and quality improvement defined by the working group that address the stated purpose

The guideline will incorporate a series of about 10 to 18 key action statements, each of which is followed by amplifying text on why the statement is made, how the recommendation may be carried out, and a summary evidence profile

Each key action statement will have an associated strength of recommendation based on the quality and consistency of supporting evidence plus a consideration of the benefit-harm relationship for any interventions

The document will conclude with implementation considerations and recommendations for future research

The detailed methodology for classifying recommendations should not be discussed at this time to avoid an unnecessary tangent. Instead, this is optimally discussed before classifications are made at the first or second in-person meeting. Members who want additional details can be referred to the American Academy of Pediatrics Policy Statement on Classifying Recommendations.16

9.5 Discuss conflicts of interest

Group members must disclose all industry relationships and potential conflicts of interest during the first conference call. The group will then decide if any particular relationships are significant enough to preclude participation of any individual(s). Relationships should be thoroughly documented and included in the guideline manuscript.

Since more than 80% of guideline authors, in general, have potential conflicts of interest, the existence of a relationship alone is not sufficient to preclude participation.30 They are only excluded if the nature of the relationship is considered by the group to interfere with objective participation (e.g., equity relationship, patent holder, royalty arrangements). Based on the nature of the disclosed relationship, a member may be asked to not participate in a specific section of the guideline where a conflict may produce bias.

9.6 Determine guideline scope

A well-crafted guideline has a clearly defined scope. Defining scope will occupy most of the first conference call, and may require a second for completion. Inexperienced guideline developers attempt to cover all aspects of a condition, resulting in a broad scope that will stall development efforts. The key to progress is a razor sharp focus from the start, recognizing that some issues important to some stakeholders will inevitably be left out.

9.6.1 Define target condition or procedure

The group should identify the conditions, procedures, or signs or symptoms for which the guideline is intended. This may be a single condition or a list of potential target conditions, which could be later condensed into those that can be realistically examined by the group within its allotted time. A guideline can be procedure-based instead of disease-oriented. For example, the emphasis can be on “tonsillectomy” as a procedure instead of tonsillitis as an acute or chronic condition.

Any diseases or procedures should be explicitly defined by the group. Definitions derived from publications on the topic can be used, if available, but a multidisciplinary group can often improve upon definitions advanced by an individual or single discipline. This is a particularly valuable contribution when existing definitions are controversial or unclear.

The definition of the target or procedure should be clear and concise (Table 3). The definition, however, should be distinguished from diagnostic criteria, which are typically specified later in the guideline and have more precise and detailed information to guide clinicians.

Table 3.

Sample definitions from clinical practice guidelines

| Guideline | Definition |

|---|---|

| Otitis Media with Effusion Guideline23 |

Otitis media with effusion as discussed in this guideline is defined as the presence of fluid in the middle ear without signs or symptoms of acute ear infection. otitis media with effusion is considered distinct from acute otitis media, which is defined as a history of acute onset of signs and symptoms, the presence of middle-ear effusion, and signs and symptoms of middle-ear inflammation. |

| Adult Sinusitis Guideline4 |

Rhinosinusitis is defined as symptomatic inflammation of the paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity. The term rhinosinusitis is preferred because sinusitis is almost always accompanied by inflammation of the contiguous nasal mucosa. Rhinosinusitis may be further classified by duration as acute (less than 4 weeks), subacute (4–12 weeks), or chronic (more than 12 weeks with or without acute exacerbations). |

| Cerumen Impaction Guideline5 |

Cerumen impaction is defined as an accumulation of cerumen that causes symptoms, prevents a needed assessment of the ear canal/tympanic membrane or audiovestibular system, or both. Although “impaction” usually implies that cerumen is lodged, wedged, or firmly packed in the ear canal, our definition of cerumen impaction does not require a complete obstruction. |

| Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo Guideline6 |

Positional vertigo is defined as a spinning sensation produced by changes in head position relative to gravity. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo is defined as a disorder of the inner ear characterized by repeated episodes of positional vertigo. |

9.6.2 Define target patient or clinical presentations

The authoring group should specify the type of patient for whom the guideline is intended as precisely as possible. The target patient can be specified in terms of demographics, presenting signs and symptoms, past health history, results of previous diagnostic tests, or similar criteria.

Equally important as defining the target patient is defining clearly the types of patients or clinical presentations that are beyond the scope of the group’s analysis. One or more exclusion criteria should generally accompany the definition. For example, consider this definition from the AAO-HNS guideline on acute otitis externa:

“The target patient is aged 2 years or older with diffuse acute otitis externa, defined as generalized inflammation of the external ear canal, with or without involvement of the pinna or tympanic membrane. This guideline does not apply to children under age 2 years or to patients of any age with chronic or malignant (progressive necrotizing) otitis externa. acute otitis externa is uncommon before age 2 years, and very limited evidence exists regarding treatment or outcomes in this age group. Although the differential diagnosis of the “draining ear” will be discussed, recommendations for management will be limited to diffuse acute otitis externa, which is almost exclusively a bacterial infection. The following conditions will be briefly discussed but not considered in detail: furunculosis (localized acute otitis externa), otomycosis, herpes zoster oticus (Ramsay Hunt syndrome), and contact dermatitis.”3

Here is another example of target patient definition from the AAO-HNS guideline on cerumen impaction:

“The target patient for this guideline is over 6 months of age with a clinical diagnosis of cerumen impaction. The guideline does not apply to patients with cerumen impaction associated with the following conditions: dermatologic diseases of the ear canal; recurrent otitis externa; keratosis obturans; prior radiation therapy affecting the ear; previous tympanoplasty/myringoplasty or canal wall down mastoidectomy. However, the guideline will discuss the relevance of these conditions in cerumen management. The following modifying factors are not the primary focus of the guideline, but will be discussed relative to their impact on management: non-intact tympanic membrane (perforation or tympanostomy tube); ear canal stenosis; exostoses; diabetes mellitus; immunocompromised state; or anticoagulant therapy.”5

9.6.3 Define the intended audience and practice settings

The decision about the intended users of the guideline needs to be made early in the process, since it influences decisions about the interventions that will be considered and the audiences to which the language in the final product and specific implementation suggestions will be directed. Ideally, a representative of each target audience group or organization should be included on the guideline working group. Stakeholder representatives should also be involved in reviewing and pre-testing the document.

Practice settings should also be defined, since a guideline may be applicable only in selected settings (e.g., rural, primary care, hospital emergency room, operating room, managed care, specific geographic regions). The working group should identify those settings in which using the guideline would be appropriate as well as settings where it should not be applied.

Here is an example of how practice setting was defined in the AAO-HNS otitis media with effusion guideline: “The guideline is intended for use by providers of health care to children, including primary care and specialist physicians, nurses and nurse practitioners, physician assistants, audiologists, speech-language pathologists, and child development specialists. The guideline is applicable to any setting in which children with otitis media with effusion would be identified, monitored, or managed.”29

As another example, consider the definition used in the guideline on benign, paroxysmal positional vertigo: “The guideline is intended for all clinicians who are likely to diagnose and manage patients with benign, paroxysmal positional vertigo and applies to any setting in which benign, paroxysmal positional vertigo would be identified, monitored, or managed.”6

9.6.4 Identify interventions to consider and exclude

The group should generate a list of the clinical interventions (diagnostic tests, treatments, preventive measures) that will be considered in developing the guideline. This list should include all interventions relevant to the topic. A sample list developed for use in a sinusitis guideline is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Sample list of interventions considered in guideline development for sinusitis*

| Diagnosis | Treatment | Prevention |

|---|---|---|

| targeted history physical examination anterior rhinoscopy transillumination nasal endoscopy nasal swabs antral puncture culture of nasal cavity, middle meatus, or other site imaging procedures blood tests: CBC, others allergy evaluation and testing immune function testing gastroesophageal reflux pulmonary function tests mucociliary dysfunction tests |

watchful waiting/observation education/information systemic antibiotics topical antibiotics oral/topical steroids systemic/topical decongestants antihistamines mucolytics leukotriene modifiers nasal saline analgesics complementary and alternative medicine postural drainage/heat biopsy (excluded from guideline) sinus surgery (excluded from guideline) |

topical steroids immunotherapy nasal lavage smoking cessation hygiene education pneumococcal vaccination influenza vaccination environmental controls |

Adapted from Rosenfeld et al.4

The purpose of the topic list is to document transparency and to stimulate discussion as development proceeds, reminding the group of all interventions available for consideration. In contrast, the list is not intended as an outline or template for writing the guideline, since many items will be outside the document focus.

A similar list of exclusions should be generated. For example, some groups may be reluctant to evaluate drugs, procedures, or other interventions that have only recently been introduced into practice and have limited experience regarding long-term benefits and harms. Other groups may find these relevant. Any exclusions should be specifically noted in the list of interventions considered (Table 4).

9.6.5 Identify outcomes to consider

Outcomes should be selected prospectively that limit scope and provide measures against which to evaluate the effectiveness of the recommendation’s limit.

HEALTH STATUS OUTCOMES are direct measures of physical morbidity, emotional well-being, mortality, or some other heath-related construct. Examples include audiometric hearing levels or survival rates for head and neck cancer (e.g., 2-year, 5-year, and 10-year).

FUNCTIONAL HEALTH STATUS measures reflect how a person functions physically, emotionally, and socially, with or without aid from the health care system. There are many general- and disease-specific surveys available to assess this construct.

QUALITY OF LIFE measures reflect how a person perceives their functional health status. Like patient satisfaction, this is an inherently subjective construct that can be measured with surveys.

Other measures to consider include cost, quality, and utilization. Often the outcome of interest is related only tenuously to the proposed interventions. In such cases, proxy indicators of outcome or process may be selected.

Here is an example of outcome definition from the AAO-HNS acute otitis externa guideline: “The primary outcome considered in this guideline is clinical resolution of acute otitis externa. Additional outcomes considered include minimizing the use of ineffective treatments; eradicating pathogens; minimizing recurrence, cost, complications and adverse events; maximizing the health-related quality of life of individuals afflicted with acute otitis externa; increasing patient satisfaction; and permitting the continued use of necessary hearing aids.”3

As another example, consider the definition from the cerumen impaction guideline: “The primary outcome considered in this guideline is resolution or change in the signs and symptoms associated with cerumen impaction. Secondary outcomes include complications or adverse events. Cost, adherence to therapy, quality of life, return to work or activity, return physician visits, and effect on co-morbid conditions (e.g., sensorineural hearing loss, conductive hearing loss) were also considered.”5

9.7 Define parameters for the stage 2 literature search

The stage 2 literature search, described in the next section, identifies randomized controlled. During the first conference call, the parameters of the literature search conducted by the staff are discussed and defined.

The group should define any constraints on the initial literature search: published vs. unpublished data, language restrictions (e.g., English language only), time periods (e.g., 1980 or later), or age groups (e.g., adults, children, or both).

The group should discuss keywords for the search. If systematic reviews are already published (or in process at Cochrane), the search strategies used are reviewed for relevance to the current project. Suggestions for MeSH (medical subject heading) terms or other search keywords are solicited.

The group should discuss search strategies for randomized controlled trials that will be combined with the keywords to identify evidence.

The group should discus bibliographic sources that will be used for the search, including the role of gray literature (e.g., symposium proceedings).

9.8 Working group assignments and deadlines

At the end of the call the group reviews specific assignments or requests for additional information made during the call. Deadlines are assigned for completing the assignment, emphasizing the importance of responding within the time frame specified.

After the call the staff leads forwards notes and minutes to the chair for review and clarification. The revised minutes are distributed to the group for review and feedback. The definitions, scope, and purpose are further refined by e-mail exchange before the next conference call.

9.9 Key points to remember

The stage 1 literature search for systematic reviews and clinical practice guidelines must be performed, assessed by the chair, and compiled into a summary grid before the call

Most of the call will be spent defining the target condition or procedure using clear, concise, language that can be readily understood by all readers

A sharply defined purpose and scope for the guideline will facilitate future efforts

Emphasis is placed on broad concepts and groups consensus; details and specifics are filled in after the call via e-mail exchange

10 STAGE 2 LITERATURE SEARCH

10.1 Purpose

The second step in identifying evidence is to assess the quantity and scope of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) available to support guideline development. Recommendations are strongest when supported by RCTs or systematic reviews of RCTs, and a paucity – or surplus – of quality studies may impact group decisions.

The stage 2 search should be coordinated by the staff lead before the second working group conference call using parameters defined by the working group during the first conference call. Search results are reviewed by the chair and assistant chairs to eliminate irrelevant items. Remaining RCTs are organized by broad subject headings to facility group discussion and reference. A summary grid is compiled and distributed to the working group. The grid is most useful if some brief, descriptive information is included for each trial, such as sample size, blinding (open, single, or double), and industry funding (no or yes).

10.2 Identifying randomized trials

Randomized trials are most valuable for evaluating therapeutic interventions. Different search strategies are required for questions related to prognosis, natural history, diagnostic tests, etc. Relevant clinical trials can be identified by:

searching standard databases – MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL – for randomized controlled trial as a specific publication type;

searching standard databases for “double blind$” or “random$” in all fields;

searching the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials accessible via the Cochrane Library website;

manual cross check of bibliographies from systematic reviews; and

-

using other strategies or search filters of known validity, such as the Cochrane highly sensitive strategy for MEDLINE randomized trials that searches for:31

“randomized controlled trial” or “controlled clinical trial” as publication type, or

“randomized,” “placebo,” or “randomly” in the abstract, or

“clinical trials as topic” as a Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) term, or

“trial” in the title, and

restricts the final set (1 or 2 or 3 or 4) by excluding “animals” as MeSH term.

10.3 Assessing quality

Randomized controlled trials are highly variable in methodology and validity. A simple and efficient scale can be used to rank quality from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent) based on (a) method and adequacy of randomization, (b) method and adequacy of masking, and (c) reporting of withdrawals and dropouts.32 A similar quality scale is available for randomized trials included in systematic reviews.33

11 CONFERENCE CALL #2: IDENTIFYING TOPICS

11.1 Purpose

The primary purpose of the second conference call (Table 2) is to refine and polish the concepts developed in the first call, particularly the scope and definition(s). The interval between the first and second conference calls should be kept short, about 4 to 6 weeks, to facilitate recall and sustain momentum.

The stage 2 literature search is now available and will help identify errors, omissions, and exclusions in the earlier discussion. The call ends with a discussion of quality improvement opportunities that are used to form a preliminary topic list, which will be further refined and prioritized by electronic mail exchange after the call. The call is planned to last 120 minutes and may be recorded.

11.2 Pre-distribute electronic materials

Documents should be distributed by e-mail prior to the conference call for review by participants before the call. Materials for predistribution include:

Agenda for the conference call

Updated working group contact information grid with conflict of interest disclosures

Results of the stage 2 literature search for randomized controlled trials

Minutes of the first call, updated to include post-call assignments and e-mail exchanges

Any other information on content or methodology identified by working group members that would be helpful in educating the group or stimulating discussion

11.3 Review first conference call and timeline

Minutes from the first conference call are reviewed, with emphasis on the guideline purpose, scope, and definitions. Feedback is also solicited on the stage 2 literature search, especially from the group content experts, regarding content, organization, and possible omissions.

Decisions made at the first meeting are reviewed and updated. Revisions to the definition(s), scope, or purpose are discussed in detail until consensus is achieved. Some changes will likely occur, now that the group is more familiar with the topic and available evidence.