Abstract

Hyperbilirubinemia remains a common condition in neonates. The constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) is an orphan nuclear receptor that has been shown to participate in the activation of the uridine diphosphate-5′-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1) gene, which plays an important role in bilirubin clearance. Oncostatin M (OSM), a member of the IL-6 family, is involved in the maturation of fetal hepatocytes. We have demonstrated that low OSM levels are a potential indicator of neonatal jaundice and the need for phototherapy. In this study we examined the effects of OSM on CAR-mediated signaling to investigate its potential role in neonatal jaundice via the CAR-UGT1A1 pathway. We observed that OSM positively augmented the CAR and UGT1A1 expressions and CAR-mediated signaling in vivo and in vitro, through cross talk between the nuclear CAR receptor and the plasma membrane OSM receptor, via the MAPK cascade. These data suggest that OSM might play a role in bilirubin metabolism via the CAR-UGT1A1 pathway.

Oncostatin M plays a role in bilirubin metabolism via the CAR-UGT1A1 pathway through crosstalk between CAR and the plasma membrane OSM receptor.

Hyperbilirubinemia remains a common condition in neonates. The risk of jaundice-associated neurotoxicities, such as kernicterus, continues to be a major concern of physicians caring for neonates (1). Bilirubin metabolism in newborn infants is still in a transitional fetal-to-adult stage. The distinctive aspects of normal newborn physiology that contribute to the development of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia include increased bilirubin synthesis (caused by the degradation of fetal hemoglobin) (2), less effective binding and transportation by albumin, less efficient hepatic conjugation and excretion (which is usually attributable to prematurity of liver function and bilirubin clearance, including poor bilirubin uridine diphosphate-5′-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT1A1) activity) (3), and enhanced absorption of bilirubin via the enterohepatic circulation (1).

The constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) is an orphan nuclear receptor. It was originally characterized as a nuclear receptor able to activate an empirical set of retinoic acid response elements without retinoic acid (4,5), and that can be activated in response to xenochemical exposure, including phenobarbital (PB)-stimulated activation of a response element, NR1, found in human and mouse cytochrome P450 (CYP)2B genes (6,7). This PB response enhancer module is also located in the upstream region of the UGT1A1 gene and is activated by CAR (8), and the activation of the bilirubin-clearance pathway by CAR ligands was abolished in CAR-null mice (9), suggesting that the CAR-UGT1A1 pathway might play an important role in bilirubin clearance.

Oncostatin M (OSM) is a member of the IL-6 cytokine family and was originally characterized by its ability to inhibit the proliferation of tumor cells (10,11,12,13,14). Since then, it has also been shown to be involved in inflammation, hematopoiesis, embryonic development, and tissue remodeling (10,13,15). In addition, OSM has recently been shown to play an important role in liver development and regeneration (10,13,15,16,17,18). The mouse OSM receptor is composed of the glycoprotein 130 subunit (gp130), common to all IL-6 family cytokines, and an OSM-specific subunit (19). Studies of gp130 knockout mice revealed an essential role for OSM/gp130 in hepatic maturation in vivo (15). In addition, we have demonstrated that OSM levels in umbilical venous blood were significantly lower in neonates who received phototherapy than in those who did not, suggesting that the requirement for phototherapy in neonatal jaundice might be associated with lower umbilical OSM concentrations (21).

Thus, CAR has been shown to participate in the activation of the UGT1A1 gene and the bilirubin clearance, whereas OSM is involved in the maturation of fetal hepatocytes (22,23), and low OSM levels could be a potential indicator for phototherapy in infants with neonatal jaundice (21). We therefore examined the effect of OSM on CAR-mediated signaling to investigate the potential role of OSM in the development of neonatal jaundice via the CAR-UGT1A1 pathway.

Results

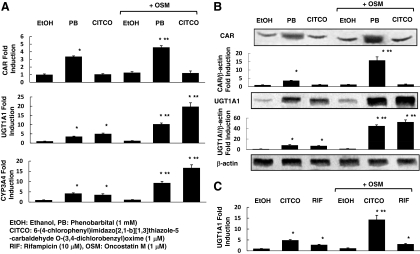

Effect of CAR ligands and OSM on CAR and UGT1A1 expression

We used human hepatoma HepG2 cells because CAR is relatively expressed in this cell line (data not shown). PB and 6-(4-chlorophenyl)imidazo[2,1-b] (1,3)thiazole-5-carbaldehyde O-(3,4-dichlorobenzyl)oxime (CITCO) were used as CAR ligands because they have been demonstrated to activate the CAR-mediated pathway (7,24). The mRNA expressions of CAR, UGT1A1, and CYP3A4, which is another target gene by CAR (25), were significantly increased in the presence of PB, and the mRNA levels of UGT1A1 and CYP3A were increased in the presence of CITCO compared with ethanol treatment, whereas OSM significantly affected CAR, UGT1A1, and CYP3A4 mRNA expression with CAR ligands, PB, or CITCO (Fig. 1A). We also observed that the protein expressions of CAR and UGT1A1 were significantly increased in the presence of PB, and only protein levels of UGT1A1 were increased in the presence of CITCO compared with ethanol treatment, whereas OSM significantly affected CAR and UGT1A1 protein expression with CAR ligands, PB, or CITCO (Fig. 1B). Then, we examined whether the induction of UGT1A1 by rifampicin (RIF) was augmented by OSM because RIF was known as a ligand for pregnane X receptor (PXR) and an inducer for UGT1A1(26). Treatment with OSM did not enhance the UGT1A1 mRNA expression in the presence of RIF (Fig. 1C), suggesting that OSM might not affect the UGT1A1 expression through PXR.

Figure 1.

Effects of OSM on CAR and UGT1A1 expressions. HepG2 cells were treated with ethanol or 10−3 m PB, 10−6 m CITCO, or 10−5 m RIF with or without 10−6 m OSM for 36 h. A, Total RNA was obtained from HepG2 cells and analyzed for the mRNA expression of CAR, UGT1A1, and CYP3A4 using real-time quantitative PCR. The mRNA levels were normalized to β-actin mRNA and expressed as fold induction over control. B, Whole-cell extracts were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. CAR, UGT1A1, and β-actin protein levels were determined by Western blotting using anti-CAR, -UGT1A1, and -β-actin antibodies. Relative protein levels are expressed by taking the control values obtained from the ethanol-treated cells as one. C, Total RNA was obtained from HepG2 cells and analyzed for the mRNA expressions of UGT1A1 using real-time quantitative PCR. The mRNA levels were normalized to β-actin mRNA and expressed as fold induction over control. The results represent the mean ± sd of triplicate determinations (*, P < 0.01 compared with ethanol-treated cells; **, P < 0.01 compared with non-OSM-treated cells).

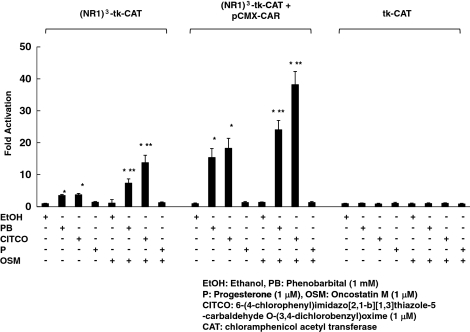

Effect of CAR ligands and OSM on CAR-mediated transcription

The reporter gene constructs, (NR1)3-tk-chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT) or tk-CAT with or without pCMX-CAR expression vector, were introduced into HepG2 cells. Both PB and CITCO significantly activated native or overexpressed CAR-mediated transcription in HepG2 cells using (NR1)3-tk-CAT (Fig. 2). Progesterone had no effect on this transcription. There were no nonspecific activations with any ligand in the cells transfected with tk-CAT. In addition, we observed significant increases in CAR-mediated transcription in the presence of OSM with CAR ligands, PB, or CITCO, compared with transcription without OSM.

Figure 2.

Effects of OSM on CAR-mediated transcription. HepG2 cells were cotransfected with 1 μg of a reporter gene construct, (NR1)3-tk-CAT or tk-CAT vector with or without pCMX-CAR expression vector. The cells were treated with ethanol vehicle or 10−3 m PB or 10−6 m CITCO or 10−6 m progesterone, with or without 10−6 m OSM for 36 h. The amount of CAT was determined using a CAT ELISA kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The results represent the mean ± sd of triplicate determinations (*, P < 0.01 compared with ethanol-treated cells; **, P < 0.01 compared with the cells without OSM treatment).

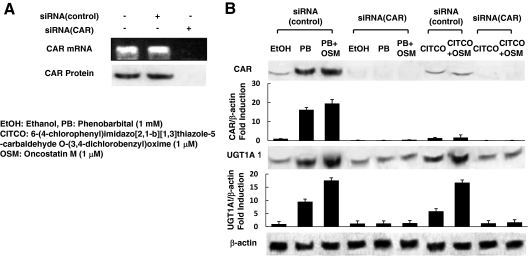

Effect of CAR small interfering RNA (siRNA) on the expression of UGT1A1 and CAR-mediated transcription in the presence of CAR ligands

To investigate the effect of CAR siRNA on the expression of CAR and UGT1A1 in the presence of CAR ligands, we qualitatively examined the levels of CAR and UGT1A1 proteins in HepG2 cells. We confirmed the efficacy of CAR siRNA for the knockdown of CAR mRNA in HepG2 cells using RT-PCR and Western blotting. Neither CAR mRNA nor CAR protein was detected in HepG2 cells transfected with CAR siRNA (Fig. 3A). In the presence of PB, both CAR and UGT1A1 protein expression were increased, and CITCO affected only the UGT1A1 expression. In cells transfected with CAR siRNA, no significant increases were seen in CAR and UGT1A1 protein levels in the presence of the CAR ligands, PB, and CITCO, compared with cells treated with control siRNA (Fig. 3B). The augmentation of CAR and UGT1A1 by OSM was not also observed in cells transfected with CAR siRNA.

Figure 3.

Effects of CAR siRNA on UGT1A1 expression and CAR-mediated transcription in the presence of CAR ligands. A, HepG2 cells were transfected with CAR or control siRNA. Whole-cell extracts were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. CAR protein levels were determined by Western blotting using anti-CAR antibodies. Total RNA was also obtained from HepG2 cells and analyzed for the expression of CAR mRNAs using RT-PCR. PCR products were separated on 3% Nu-Sieve agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. B, HepG2 cells were transfected with CAR or control siRNAs and treated with ethanol vehicle or 10−3 m PB or 10−6 m CITCO with or without 10−6 m OSM for 36 h. Whole-cell extracts were prepared and CAR, UGT1A1, and β-actin protein levels were determined by Western blotting. Relative protein levels are expressed by taking the control values obtained from the ethanol-treated cells as one. Each bar represents the mean ± sd from three independent experiments.

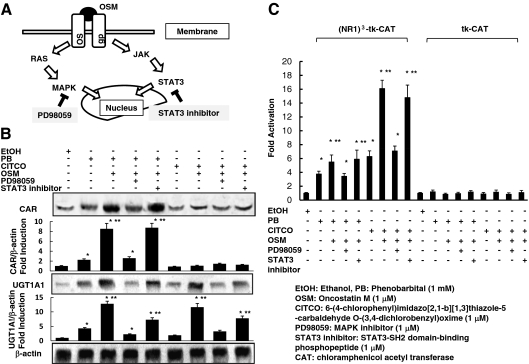

MAPK inhibitor abolishes the effects of OSM on CAR-UGT1A1 pathway

OSM is involved in two signal transduction pathways, through either signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)3 or MAPK (Fig. 4A) (27,28). We examined which pathway was important for the effects of OSM on the CAR-UGT1A1 pathway. The MAPK inhibitor PD98059 abolished the effects of OSM on CAR and UGT1A1 expression in the presence of the CAR ligands (Fig. 4B). In contrast, a STAT3 inhibitor had no effect on their expression. Moreover, we also observed that augmentation of native CAR-mediated transcription by OSM was prevented in the presence of PD98059, whereas a STAT3 inhibitor had no effect on OSM augmentation of CAR-mediated transcription (Fig. 4C). The lack of differences in basal transcription using the tk-CAT vector indicated that there were no nonspecific effects of PD98059 or STAT3 inhibitor on transcription.

Figure 4.

MAPK inhibitor abolishes the effects of OSM on CAR-UGT1A1 pathway. A, Schema of CAR transduction cascade and inhibitor. B, HepG2 cells were treated with ethanol or 10−3 m PB or 10−6 m CITCO, with or without 10−6 m OSM, PD98059, or STAT inhibitor for 36 h. Whole-cell extracts were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. CAR, UGT1A1, and β-actin protein levels were determined by Western blotting using anti-CAR, -UGT1A1, and -β-actin antibodies. Relative protein levels are expressed by taking the control values obtained from the ethanol-treated cells as one. C, HepG2 cells were cotransfected with 1 μg of a reporter gene construct, (NR1)3-tk-CAT, or tk-CAT vector. The cells were treated with ethanol or 10−3 m PB or CITCO, with or without 10−6 m OSM, PD98059, or STAT inhibitor for 36 h. The amount of CAT was determined using a CAT ELISA kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The results represent the mean ± sd of triplicate determinations (*, P < 0.01 compared with ethanol-treated cells; **, P < 0.01 compared with PB or CITCO-treated cells without OSM).

Effect of OSM on CAR and UGT1A1 expression in neonatal mice in vivo

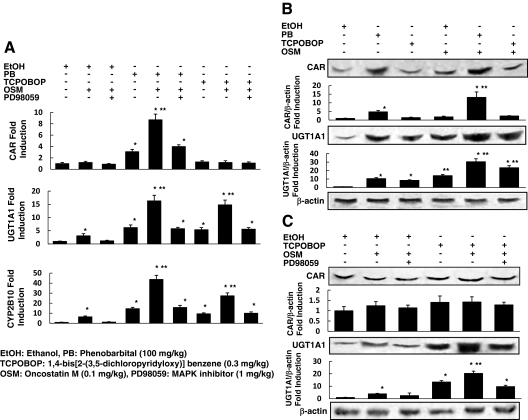

CAR, UGT1A1, and CYP2B10 expression in the livers of neonatal ICR mice (d 3) after 72-h exposure to PB, 1,4-bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)] benzene (TCPOBOP), or ethanol, with or without OSM and PD98059, were analyzed using real-time quantitative PCR and Western blotting. Five neonatal mice were analyzed for each treatment group. We used TCPOBOP, which was shown to specially bind to mouse CAR, instead of CITCO, which binds only to human CAR, as a ligand for murine CAR (29) and analyzed the expression of CYP2B10, which is another target gene of murine CAR (6). The CAR, UGT1A1, and CYP2B10 mRNA expressions were markedly increased after exposure to PB, and UGT1A1 and CYP2B10 expression was increased after exposure to TCPOBOP, compared with ethanol (Fig. 5A). Treatment with OSM enhanced the CAR expression in the presence of PB and enhanced the UGT1A1 and CYP2B10 expression in the presence or absence of the CAR ligands. We also examined whether the MAPK inhibitor PD98059 blocked the effects of OSM on the CAR-UGT1A1 pathway. PD98059 blocked the augmentation of the mRNA expressions of UGT1A1 and CYP2B10 by OSM in the presence or absence of the CAR ligands (Fig. 5A). Then, we also examined the effect of OSM on the CAR-UGT1A1 signaling in protein levels using Western blotting. Protein levels of CAR and UGT1A1 were markedly increased after exposure to PB, and only UGT1A1 protein expression was increased after exposure to TCPOBOP, compared with ethanol (Fig. 5B). Treatment with OSM enhanced the CAR expression in the presence of PB and UGT1A1 expression in the presence or absence of the CAR ligands, whereas PD98059 blocked the augmentation of the UGT1A1 expression by OSM in the presence or absence of the CAR ligand, TCPOBOP (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Effects of OSM on CAR and UGT1A1 expression in neonatal mice in vivo. Neonatal ICR mice (3 d old) were administered PB (100 mg/kg), TCPOBOP (0.3 mg/kg), or ethanol, with or without OSM (0.1 mg/kg) or PD98059 (1 mg/kg) via ip injection every 24 h. The animals were killed under ether anesthesia 72 h after the injection, and the livers were removed, immediately frozen, and stored at −70 C. A, The mRNA expression of CAR, UGT1A1, and CYP2B10 in the livers of mice after 72-h exposure to TCPOBOP or ethanol, with or without OSM or PD98059, was analyzed using real-time quantitative PCR. The mRNA levels were normalized to β-actin mRNA and expressed as fold induction over control. B, CAR, UGT1A1, and β-actin protein expression in the livers of mice after 72-h exposure to PB, TCPOBOP, or ethanol, with or without OSM, was determined by Western blotting using anti-CAR, -UGT1A1, and -β-actin antibodies. Relative protein levels are expressed by taking the control values obtained from the ethanol-treated mouse as one. C, CAR, UGT1A1, and β-actin protein expression in the livers of mice after 72-h exposure to TCPOBOP or ethanol, with or without OSM or PD98059, were determined by Western blotting using anti-CAR, -UGT1A1, and -β-actin antibodies. Relative protein levels are expressed by taking the control values obtained from the ethanol-treated mouse as one. Five neonatal mice were analyzed for each treatment group. The results represent the mean ± sd of triplicate determinations (*, P < 0.01 compared with ethanol treatment without OSM; **, P < 0.01 compared with PB or TCPOBOP treatment without OSM).

Discussion

In this study, we examined the effects of OSM on CAR-UGT1A1 signaling. We observed that CAR ligands, PB, and CITCO enhanced both UGT1A1 expression and CAR-mediated transcription, whereas the CAR expression was also increased only in the presence of PB. OSM positively enhanced both CAR and UGT1A1 expressions and CAR-mediated transcription in the presence of CAR ligands in vitro but in the absence and presence of CAR ligands in vivo. We also confirmed that the effects of OSM on CAR-UGT1A1 signaling were mediated by CAR itself, by down-regulating CAR using siRNA. In addition, we demonstrated that MAPK in signal transduction by CAR might play important roles for the cross talk with CAR in vitro and in vivo.

In this study, we demonstrated that the CAR itself was essential for both direct target gene regulation by CITCO or TCPOBOP and indirect target gene regulation by PB. Although PB, CITCO, and TCPOBOP are known as CAR ligands, there are some differences of effect on CAR-UGT1A1 pathway, especially on CAR expression, between PB and CITCO/TCPOBOP. CITCO and TCPOBOP are the only ligands shown to specifically bind to human and mouse CAR and regulate the target genes, respectively (24,29). However, PB shows no evidence of direct binding to CAR and causes the activation of phosphatase 2A and the translocation from the cytoplasma to the nucleus, which results in the activation of target gene expression in the absence of ligand binding (6,7). Because PB enhances posttranslational modifications through phosphatase 2A (30), but there were no reports that CITCO and TCPOBOP affect such modifications, an unknown mechanism might exist in the regulation of CAR expression. Further analysis will be required to investigate the regulation of CAR expression in CAR-mediated signaling pathway.

OSM is a cytokine from the IL-6 family that binds to a plasma membrane receptor complex containing the OSM receptor and gp130 (27,28). Although several other growth factors and cytokines, including epidermal growth factor (EGF), GH, IL-1β, and IL-6 have been reported to repress PB induction of CAR target genes and/or CAR expression (31,32,33,34), we observed that OSM positively enhanced CAR-UGT1A1 pathway in the presence of CAR ligands in vitro and in the absence of CAR ligands only in vivo, suggesting that endogenous CAR ligands might participate in the positive effect by OSM in vivo. Moreover, signal transduction by OSM involves activation of Janus kinase tyrosine kinase family members, leading to the activation of transcription factors in the STAT and MAPK cascades (27,28). We therefore determined which cascade was responsible for the effects of OSM on CAR. The positive effect of OSM on CAR-mediated signaling was blocked by a MAPK inhibitor, but not by a STAT inhibitor, suggesting that the MAPK cascade might be important for this effect.

The biological effects of steroid hormones are mediated by nuclear receptors acting as transcriptional activators. Nuclear receptors, in addition to being induced by their own ligands, are also regulated by cellular kinases activated by growth factors, including EGF (35,36). Growth factors are known to influence the expression and activity of nuclear receptors as well as to regulate the action of various nuclear receptor transcriptional cofactors (35,36). In particular, the estrogen receptor is phosphorylated and activated by several intracellular kinases, including the MAPK pathway through the EGF receptor (35,37). Estrogen receptor phosphorylation can result in ligand-independent activation of the receptor (37). In addition, pregnane X receptor (PXR) can be also phosphorylated, resulting in the induction of PXR-mediated target gene expression with the strengthened PXR-coactivator protein-protein interaction (38). Moreover, protein phosphorylation of nuclear receptor coativators as well as nuclear receptors play important roles in nuclear receptor functions (39). Thus, phosphorylation signals to nucleus in response to activation of MAPK pathway by OSM might enhance CAR-mediated signaling through the phosphorylation of CAR and/or CAR coativators such as glucocorticoid receptor interacting protein-1, steroid receptor coativator-1, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1, which have been reported to participate in CAR-mediated transcription (40,41,42). Nuclear localization of CAR in the presence of CAR ligands might be important for CAR transcriptional activity, and the dephosphorylation of CAR constitutes a crucial signal for its release from the cytosolic complex upon PB treatment (43,44). Further studies are needed to clarify the role of phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of CAR and coactivators in the regulation of CAR-mediated signaling by OSM.

We observed that CAR expression in the liver and intestines of mice during the perinatal period were very weak, compared with their expression in adults (data not shown). Huang et al. (9) demonstrated that activation of the bilirubin-clearance pathway by CAR ligands was abolished in CAR-null mice and the CAR expression was much lower in neonatal livers than adult livers. Thus, these expression patterns suggested that the activity of the CAR-UGT1A1 pathway for bilirubin metabolism might be very low in mice during the perinatal period. In this study, we demonstrated that OSM, an important factor in liver development and maturation, positively augmented CAR-mediated signaling in vitro and in vivo, through cross talk between the nuclear receptor, CAR, and the plasma membrane OSM receptor via the MAPK pathway. These data suggest that OSM might be involved in bilirubin metabolism, acting via the CAR-UGT1A1 pathway and the potential therapeutic target for the prevention and treatment of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Progesterone, RIF, TCPOBOP, CITCO, and PB were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). PD98059 was obtained from A.G. Scientific, Inc. (San Diego, CA). STAT inhibitor, which was a STAT3-SH2 domain-binding phosphopeptide that acted as a highly selective blocker of STAT3 activation (45), was purchased from Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corp. (San Diego, CA). OSM was purchased from R & D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN). HepG2 cells were obtained from the Health Science Research Resources Bank (Osaka, Japan).

Cell culture and RNA interference

HepG2 cells were cultured in DMEM without phenol red, supplemented with 10% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum. The medium and serum were purchased from Invitrogen Corp. (Carlsbad, CA). The siRNA cocktail targeting human CAR was purchased from B-Bridge International, Inc. (Mountain View, CA) and contained three siRNAs as follows: first sequence, gggaagaugagcugaggaa (sense) and uuccucagcucaucuuccc (antisense); second sequence, gcaacugaguaaggagcaa (sense) and uugcuccuuacucaguugc (antisense); and third sequence, ccauggaacacuacgaaaa (sense) and uuuucguaguguuccaugg (antisense). A negative control cocktail, which consisted of noncomplementary human, mouse, rat, and liposome sequences for siRNA transfection (siFECTOR), were also purchased from B-Bridge International, Inc. Cells were transfected with CAR siRNA or control siRNA using siFECTOR, according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Western blot analysis

Whole-cell extracts were obtained from cells using M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagents (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL), according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and stored at −80 C until analysis. Protein extracts were also obtained from tissues of fetal, neonatal, and adult ICR mouse (Charles River Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) using T-PER Tissue Protein Extraction Reagent (Pierce Chemical Co.). Protein content was determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Pierce Chemical Co.), and equivalent amounts of nuclear protein (25 μg/sample) from each extract were solubilized in sodium dodecyl sulfate buffer (0.05m Tris-HCl; 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate; 6% mercaptoethanol; 10% glycerol, pH 6.8) and analyzed by Western blot analysis, as previously described (46). We used a rabbit polyclonal antibody for CAR (1:1000 dilution), and goat polyclonal antibodies for UGT1A1 (1:1000 dilution) and β-actin (1:1000 dilution) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA). Each band was quantitatively analyzed by densitometry using Image Scanner GT-9500 (Epson, Suwa, Japan) and Bio Image BQ 2.0 software (Ann Arbor, MI).

RT-PCR and real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from HepG2 cells and mouse liver using Trizol reagent (Life Technology, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). The sequences of primers and probes for human and mouse CAR, UGT1A1, CYP3A4 and β-actin have been described previously (25,47). To confirm the down-regulation of CAR by RNA interference, RT-PCR was performed using an RNA PCR kit (Takara Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Amplification of CAR was carried out on a GeneAmp PCR system 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, CA). The number of PCR cycles required to produce PCR products in the linear logarithmic phase of the amplification curve was determined. PCR samples were electrophoresed on 3% agarose gels and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide. To measure the mRNA levels of CAR, UGT1A1, CYP3A4, and CYP2B10, real-time quantitative PCR was performed using a StepOne real-time PCR System with TaqMan RNA-to-CT gene kit (Applied Biosystems). RNA samples (25 ng) were assayed with 15 pmol of gene-specific primers and 5 pmol of gene-specific probe in triplicate. For an internal control, human or mouse β-actin was measured using predeveloped TaqMan primer and probe mixture (Applied Biosystems). The mRNA levels were normalized to β-actin mRNA and expressed as fold induction over control.

Transient transfection studies

The pCMX-CAR expression plasmid containing the full-length human CAR cDNA was kindly provided by Dr. R. Evans (The Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, CA) (20). The (PBRE)3-tk-CAT vector was generated by insertion of three copies of double-stranded oligonucleotides containing the NR1 site (5-gatcACTGTACTTTCCTGACCTTGgatc-3), as described previously (7). HepG2 cells were cotransfected with 1 μg of a reporter gene construct, (NR1)3-tk-CAT or tk-CAT vector, with or without pCMX-CAR expression vector. In all transfections, liposome-mediated transfections were accomplished using Lipofectamine (Life Technologies, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transfected cells were treated either with vehicle alone or with the indicated concentrations of CAR ligands for 24 h. Cell extracts were prepared and assayed for CAT activity. The amount of CAT was determined using a CAT ELISA kit (Roche Diagnostics Co., Tokyo, Japan), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Administration of CAR ligands and OSM to mice and tissue collection

Neonatal ICR mice (3 d old) were administered PB (100 mg/kg), TCPOBOP (0.3 mg/kg), or ethanol, with or without OSM (0.1 mg/kg) or PD98059 (1 mg/kg) via ip injection every 24 h. The animals were killed under ether anesthesia 72 h after the injection, and the livers were removed, immediately frozen, and stored at −70 C. Protein was extracted using T-PER Tissue Protein Extraction Reagents (Pierce Chemical Co.), and total RNA was also extracted using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, Inc.), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. Data are the means ± sd. P < 0.05 denotes the presence of a statistically significant difference.

Footnotes

This work was supported, in part, by research grants (17591739) from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan and the Okayama Medical Foundation (to H.M.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online March 2, 2010

Abbreviations: CAR, Constitutive androstane receptor; CAT, chloramphenicol acetyl transferase; CITCO, 6-(4-chlorophenyl)imidazo[2,1-b] (1,3)thiazole-5-carbaldehyde O-(3,4-dichlorobenzyl)oxime; CYP, cytochrome P450; EGF, epidermal growth factor; OSM, oncostatin M; PB, phenobarbital; PXR, pregnane X receptor; RIF, rifampicin; siRNA, small interfering RNA; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; TCPOBOP, 1,4-bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)] benzene; UGT1A1, uridine diphosphate-5′-glucuronosyltransferase.

References

- Stoll BJ, Kliegman RM 2006 Jaundice and hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, eds. Nelson textbook of pediatrics, 18th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 592–599 [Google Scholar]

- Bartoletti AL, Stevenson DK, Ostrander CR, Johnson JD 1979 Pulmonary excretion of carbon monoxide in the human infant as an index of bilirubin production. l. Effects of gestational and postnatal age and some common neonate abnormalities. J Pediatr 94:952–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onishi S, Kawade N, Itoh S, Isobe K, Sugiyama S 1979 Postnatal development of uridine diphosphate glucuronosyl transferase activity toward bilirubin and o-aminophenol in human liver. Biochem J 194:705–707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baes M, Gulick T, Choi HS, Martinoli MG, Simha D, Moore DD 1994 A new orphan member of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily that interacts with a subset of retinoic acid response elements. Mol Cell Biol 14:1544–1552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HS, Chung M, Tzameli I, Simha D, Lee YK, Seol W, Moore DD 1997 Differential transactivation by two isoforms of the orphan nuclear hormone receptor CAR. J Biol Chem 272:23565–23571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honkakoski P, Zelko I, Sueyoshi T, Negishi M 1998 The nuclear orphan receptor CAR-retinoid X receptor heterodimer activates the phenobarbital-responsive enhancer module of the CYP2B gene. Mol Cell Biol 18:5652–5658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sueyoshi T, Kawamoto T, Zelko I, Honkakoski P, Negishi M 1999 The repressed nuclear receptor CAR responds to phenobarbital in activating the human CYP2B6 gene. J Biol Chem 274:6043–6046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugatani J, Kojima H, Ueda A, Kakizaki S, Yoshinari K, Gong QH, Owens IS, Negishi M, Sueyoshi T 2001 The phenobarbital response enhancer module in the human bilirubin UDP-glucuronosyltransferase UGT1A1 gene and regulation by the nuclear receptor CAR. Hepatology 33:1232–1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Zhang J, Chua SS, Qatanani M, Han Y, Granata R, Moore DD, Huang W, Zhang J, Chua SS, Qatanani M, Han Y, Granata R, Moore DD 2003 Induction of bilirubin clearance by the constitutive androstane receptor (CAR). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:4156–4161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyajima A, Kinoshita T, Tanaka M, Kamiya A, Mukouyama Y, Hara T 2000 Role of Oncostatin M in hematopoiesis and liver development. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 11:177–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taga T, Kishimoto T 1997 Gp130 and the interleukin-6 family of cytokines. Annu Rev Immunol 15:797–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Miyajima A 2003 Oncostatin M. a multifunctional cytokine. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 149:39–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace PM, MacMaster JF, Rouleau KA, Brown TJ, Loy JK, Donaldson KL, Wahl AF 1999 Regulation of inflammatory responses by oncostatin M. J Immunol 162:5547–5555 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarling JM, Shoyab M, Marquardt H, Hanson MB, Lioubin MN, Todaro GJ 1986 Oncostatin M: a growth regulator produced by differentiated histiocytic lymphoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 83:9739–9743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya A, Kinoshita T, Ito Y, Matsui T, Morikawa Y, Senba E, Nakashima K, Taga T, Yoshida K, Kishimoto T, Miyajima A 1999 Fetal liver development requires a paracrine action of oncostatin M through the gp130 signal transducer. EMBO J 18:2127–2136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Nonaka H, Saito H, Tanaka M, Miyajima A 2004 Hepatocyte proliferation and tissue remodeling is impaired after liver injury in oncostatin M receptor knockout mice. Hepatology 39:635–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okaya A, Kitanaka J, Kitanaka N, Satake M, Kim Y, Terada K, Sugiyama T, Takemura M, Fujimoto J, Terada N, Miyajima A, Tsujimura T 2005 Oncostatin M inhibits proliferation of rat oval cells, OC15-5, inducing differentiation into hepatocytes. Am J Pathol 166:709–719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Sekiguchi T, Xu MJ, Ito Y, Kamiya A, Tsuji K, Nakahata T, Miyajima A 1999 Hepatic differentiation induced by oncostatin M attenuates fetal liver hematopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:7265–7270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Hara T, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Miyajima A 1999 Reconstitution of the functional mouse oncostatin M (OSM) receptor: molecular cloning of the mouse OSM receptor β subunit. Blood 93:804–815 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W, Barwick JL, Simon CM, Pierce AM, Safe S, Blumberg B, Guzelian PS, Evans RM 2000 Reciprocal activation of xenobiotic response genes by nuclear receptors SXR/PXR and CAR. Genes Dev 14:3014–3023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsukasa H, Masuyama H, Akahori Y, Inoue S, Masumoto A, Hiramatsu Y 2008 Relations between neonatal jaundice and oncostatin M, hepatocyte growth factor and soluble gp130 levels in umbilical cord. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 87:1322–1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya A, Kinoshita T, Miyajima A 2001 Oncostatin M and hepatocyte growth factor induce hepatic maturation via distinct signaling pathways. FEBS Lett 492:90–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Matsui T, Kamiya A, Kinoshita T, Miyajima A 2000 Retroviral gene transfer of signaling molecules into murine fetal hepatocytes defines distinct roles for the STAT3 and ras pathways during hepatic development. Hepatology 32:1370–1376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maglich JM, Parks DJ, Moore LB, Collins JL, Goodwin B, Billin AN, Stoltz CA, Kliewer SA, Lambert MH, Willson TM, Moore JT 2003 Identification of a novel human constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) agonist and its use in the identification of CAR target genes. J Biol Chem 278:17277–17283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin B, Hodgson E, D'Costa DJ, Robertson GR, Liddle C 2002 Transcriptional regulation of the human CYP3A4 gene by the constitutive androstane receptor. Mol Pharmacol 62:359–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugatani J, Nishitani S, Yamakawa K, Yoshinari K, Sueyoshi T, Negishi M, Miwa M 2005 Transcriptional regulation of human UGT1A1 gene expression: activated glucocorticoid receptor enhances constitutive androstane receptor/pregnane X receptor-mediated UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 regulation with glucocorticoid receptor-interacting protein 1. Mol Pharmacol 67:845–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich PC, Behrmann I, Haan S, Hermanns HM, Müller-Newen G, Schaper F 2003 Principles of interleukin (IL)-6-type cytokine signalling and its regulation. Biochem J 374:1–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Lechón MJ 1999 Oncostatin M: signal transduction and biological activity. Life Sci 65:2019–2030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzameli I, Pissios P, Schuetz EG, Moore DD 2000 The xenobiotic compound 1,4-bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)] benzene is an agonist ligand for the nuclear receptor CAR. Mol Cell Biol 20:2951–2958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinari K, Kobayashi K, Moore R, Kawamoto T, Negishi M 2003 Identification of the nuclear receptor CAR:HSP90 complex in mouse liver and recruitment of protein phosphatase 2A in response to phenobarbital. FEBS Lett 548:17–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kietzmann T, Hirsch-Ernst KI, Kahl GF, Jungermann K 1999 Mimicry in primary rat hepatocyte cultures of the in vivo perivenous induction by phenobarbital of cytochrome P-450 2B1 mRNA: role of epidermal growth factor and perivenous oxygen tension. Mol Pharmacol 56:46–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer D, Wolfram N, Kahl GF, Hirsch-Ernst KI 2004 Transcriptional regulation of CYP2B1 induction in primary rat hepatocyte cultures: repression by epidermal growth factor is mediated via a distal enhancer region. Mol Pharmacol 65:172–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assenat E, Gerbal-Chaloin S, Larrey D, Saric J, Fabre JM, Maurel P, Vilarem MJ, Pascussi JM 2004 Interleukin 1β inhibits CAR-induced expression of hepatic genes involved in drug and bilirubin clearance. Hepatology 40:951–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascussi JM, Gerbal-Chaloin S, Pichard-Garcia L, Daujat M, Fabre JM, Maurel P, Vilarem MJ 2000 Interleukin-6 negatively regulates the expression of pregnane X receptor and constitutively activated receptor in primary human hepatocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 274:707–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arpino G, Wiechmann L, Osborne CK, Schiff R 2008 Crosstalk between the estrogen receptor and the HER tyrosine kinase receptor family: molecular mechanism and clinical implications for endocrine therapy resistance. Endocr Rev 29:217–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu ML, Kyprianou N 2008 Androgen receptor and growth factor signaling cross-talk in prostate cancer cells. Endocr Relat Cancer 15:841–849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato S, Endoh H, Masuhiro Y, Kitamoto T, Uchiyama S, Sasaki H, Masushige S, Gotoh Y, Nishida E, Kawashima H, Metzger D, Chambon P 1995 Activation of the estrogen receptor through phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinase. Science 270: 1491–1494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X, Staudinger JL 2005 Induction of drug metabolism by forskolin: the role of the pregnane X receptor and the protein kinase a signal transduction pathway. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 312:849–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu RC, Smith CL, O'Malley BW 2005 Transcriptional regulation by steroid receptor coactivator phosphorylation. Endocr Rev 26:393–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min G, Kemper JK, Kemper B 2002 Glucocorticoid receptor-interacting protein 1 mediates ligand-independent nuclear translocation and activation of constitutive androstane receptor in vivo. J Biol Chem 277:26356–26363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muangmoonchai R, Smirlis D, Wong SC, Edwards M, Phillips IR, Shephard EA 2001 Xenobiotic induction of cytochrome P450 2B1 (CYP2B1) is mediated by the orphan nuclear receptor constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) and requires steroid co-activator 1 (SRC-1) and the transcription factor Sp1. Biochem J 355:71–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiraki T, Sakai N, Kanaya E, Jingami H 2003 Activation of orphan nuclear constitutive androstane receptor requires subnuclear targeting by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α—a possible link between xenobiotic response and nutritional state. J Biol Chem 278:11344–11350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto T, Sueyoshi T, Zelko I, Moore R, Washburn K, Negishi M 1999 Phenobarbital-responsive nuclear translocation of the receptor CAR in induction of the CYP2B gene. Mol Cell Biol 19:6318–6322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honkakoski P, Negishi M 1998 Protein serine/threonine phosphatase inhibitors suppress phenobarbital-induced Cyp2b10 gene transcription in mouse primary hepatocytes. Biochem J 330:889–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkson J, Ryan D, Kim JS, Zhang Y, Chen Z, Haura E, Laudano A, Sebti S, Hamilton AD, Jove R 2001 Phosphotyrosyl peptides block Stat3-mediated DNA binding activity, gene regulation, and cell transformation. J Biol Chem 276:45443–45455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuyama H, MacDonald PN 1998 Proteasome-mediated degradation of the vitamin D receptor (VDR) and a putative role for SUG1 interaction with the AF-2 domain of VDR. J Cell Biochem 71:429–440 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maglich JM, Stoltz CM, Goodwin B, Hawkins-Brown D, Moore JT, Kliewer SA 2002 Nuclear pregnane X receptor and constitutive androstane receptor regulate overlapping but distinct sets of genes involved in xenobiotic detoxification. Mol Pharmacol 62:638–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]