Abstract

While several experimental techniques now exist for characterizing protein unfolded states, all-atom simulation of unfolded states has been challenging due to the long time scales and conformational sampling required. We address this problem by using a combination of accelerated calculations on graphics processor units and distributed computing to simulate tens of thousands of molecular dynamics trajectories each up to ~10 μs (for a total aggregate simulation time of 127 milliseconds). We used this approach in conjunction with Trp-Cys contact quenching experiments to characterize the unfolded structure and dynamics of protein L. We employed a polymer theory method to make quantitative comparisons between high temperature simulated and chemically denatured experimental ensembles, and find that reaction-limited quenching rates calculated from simulation agree remarkably well with experiment. In both experiment and simulation, we find that unfolded state intramolecular diffusion rates are very slow compared to highly denatured chains, and that a single-residue mutation can significantly alter unfolded state dynamics and structure. This work suggests a view of the unfolded state in which surprisingly low diffusion rates could limit folding, and opens the door for all-atom molecular simulation to be a useful predictive tool for characterizing protein unfolded states along with experiments that directly measure intramolecular diffusion.

Introduction

One requirement for a full understanding of the folding reaction must be an accurate description of the unfolded protein before it folds. In recent years, some progress has been made in this respect. An increasing wealth of experimental techniques are now available to characterize unfolded conformational ensembles1,2. SAXS techniques can provide static or time-resolved measurements of unfolded-state Rg3,4. In addition to NMR observables such as NOEs and chemical shifts, unfolded states and early folding events have been recently characterized by residual dipolar couplings5–7, paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) studies8,9. Single-molecule FRET spectroscopy has been used to characterize the ensemble conformational distributions of many proteins in denaturant, including protein L, with the common finding that the denatured ensemble becomes more compact in decreasing amounts of denaturant10–13. However it is not generally known how the dynamics of reconfiguration in unfolded proteins change with denaturant.

The intrachain dynamics of unfolded states have been measured in several studies using contact quenching techniques14–18. The Trp-Cys quenching method measures intramolecular contact rates by the triplet quenching of a tryptophan residue by cysteine to obtain information about loop closure dynamics and conformational distributions16,19. Trp-Cys quenching studies have shown that proteins L and G share similar denatured state structure and intramolecular dynamics20, with lower rates of intramolecular diffusion in decreasing amounts of denaturant. Similar findings have been made using single-molecule FRET21 and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy22.

To interpret the results of dynamic unfolded-state experiments, it is necessary to obtain high-quality simulation models of the unfolded state. For instance, deviations from random-coil behavior have been interpreted as being a result of unfolded state structure23,24, a question which can be addressed by molecular simulation. However, most computational models of unfolded state ensembles to date have been either: random-coil or worm-like chain models25,26 generated from Monte Carlo chain sampling algorithms,27,28, short molecular dynamics simulations29,30 often using restraints from experimental NMR data31–33, or Go-like models, which contain native-state bias and can be tuned to reproduce experimental unfolded state data34–36. Physics-based all-atom simulations of unfolded ensembles offer significant advantages over simpler models, which include the ability to 1) generate ensembles unbiased by native state information, 2) provide quantitative chemical detail, 3) model unfolded states in the absence of denaturant, and 4) predict early folding events under folding conditions.

In this paper, we report significant advances in using all-atom molecular simulation as a predictive tool to probe unfolded states of proteins in concert with Trp-Cys quenching studies that directly measure intramolecular diffusion. Traditional simulation approaches for this purpose have been unfeasible due to the dual computational challenges of adequate conformational sampling and slow dynamical time scales. We solve this problem by taking advantage of accelerated calculations on graphics processor units via the Folding@Home distributed computing platform, which allow us to simulate tens of thousands of all-atom, implicit solvent molecular dynamics trajectories out to ~10 μs in order to generate converged ensembles of unfolded states. We also solve the problem of quantitatively comparing simulations to experimental ensembles by using a polymer model of the coil-globule transition to calibrate simulated temperature and experimental denaturant concentration.

Using these techniques, we probe the structure and dynamics of unfolded states of protein L. The simulations predict collapse on the 100 ns timescale, achieve excellent quantitative agreement with reaction-limited quenching rates, and recapitulate similar trends in compaction and diffusivity as a function of denaturant concentration. Uniquely accessible by simulation is unfolded state structure and dynamics in the absence of denaturant. We predict a compact globular state with greater native-like structuring than seen in chemically denatured states. However, our analysis also finds that the implicit solvent model used in the simulations overly stabilizes compact states, the implications of which we discuss. We also characterize a destabilized single-residue mutant (F22A) of protein L which can be studied experimentally in lower concentrations of denaturant, and find it to be less compact and surprisingly more (intramolecularly) diffusive in the unfolded state. Simulations predict similar sequence-dependent differences, suggesting a structural explanation.

Materials and Methods

Molecular dynamics simulation

Standard MD simulations were performed using the AMBER9 molecular dynamics package. Distributed GPU MD simulations were performed using an accelerated version of GROMACS37 written specifically for GPUs38 using the Folding@Home platform. The AMBER ff9639 and ff0340 forcefields were used with the generalized Born/surface area (GBSA) implicit solvent model of Onufriev, Bashford and Case41. Tens of thousands of parallel simulations at 300K, 330K, 370K and 450K were performed using stochastic integration with water-like viscosity. We found the two forcefield models to perform comparably, so we present only the results using AMBER96, which has been reported to have more accurate secondary structure propensities when used with GBSA42. (See Supporting Information for more details.)

Experimental methods

The Protein L plasmid was a kind gift from David Baker and was mutated and expressed as described previously20. The instrument to measure tryptophan triplet lifetimes has been described previously20. Briefly, the tryptophan triplet is populated simultaneously with the singlet state within a 10 ns pulse of light at 289 nm. The triplet population is monitored by absorption at 442 nm. In aqueous conditions, the triplet lives for 40 μs in the absence of quenching, but can be observed to decay in as little as 100 ns for a short peptide with Trp and Cys at the ends16. The decay in optical absorption was detected by a silicon detector and observed on two oscilloscopes to cover a time range between 10 ns and 100 ms.

Results and Discussion

Equilibration of simulated unfolded ensembles

Molecular dynamics simulations of the unfolded state of the 64-residue protein L (see Methods) were initially conducted on standard CPUs starting from extended and coil conformations. These trajectories converged within 10 ns for temperatures above 500 K but for lower temperatures, each 10 ns trajectory produced an independent and nonergodic distribution of distances (see Fig. 2d). Therefore we attempted to simulate a large ensemble of longer trajectories (up to ~10 μs) using graphics processing units (GPUs) and distributed computing (See Methods).

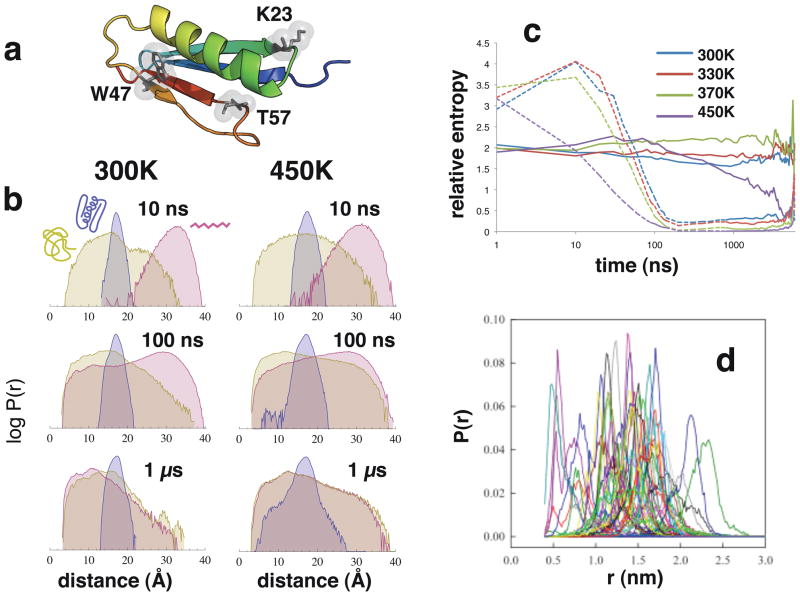

Figure 2. Convergence of simulated intermolecular distance distributions.

(a) A cartoon representation of the native structure of protein L. Highlighted residues are the single tryptophan W47, and residues K23 and T57, each used to make single-cysteine mutants. (b) Simulated distributions of W47-T57C distances over time, for various starting states, at 300K and 450K. The vertical axis is on a logarithmic scale to enhance detail. (c) The relative entropy of Pext(r) (dashed line) and Pnative(r) (solid line) with respect to P0(r)=Pcoil(r) over time, at various temperatures. Smaller values of relative entropy, computed as ∫drP(r)log[P(r)/P0(r)] over 50 ns segments, reflect more similar distributions. (d) Histograms of W47-T57 distances compiled from the last half of fifty 10-ns simulations, each started from a different random-coil configuration.

The simulated native state of protein L is very stable, drifting only ~2.5Å RMSD (Cα) over the course of microseconds (Figure S1). The average native-state radius of gyration (Rg) of protein L in the simulations is ≈12Å. This is similar to values seen in other simulation studies30, and compares well to the Rg=11.8Å of the NMR structure (2PTL), but lower than the value of ≈16.2Å measured in SAXS experiments3 and estimated from single molecule FRET experiments at low denaturant concentrations11. As noted by Merchant et al., this difference may be explained by His-tag and FRET labeling effects, and/or overestimation of Rg in the SAXS experiment12. For the high-temperature (450K) simulations started from the native state, Rg begins to increase after ~1 μs as a fraction of the population transitions to the random-coil ensemble, although convergence is not reached within the simulation time, consistent with the millisecond-timescale unfolding rate43.

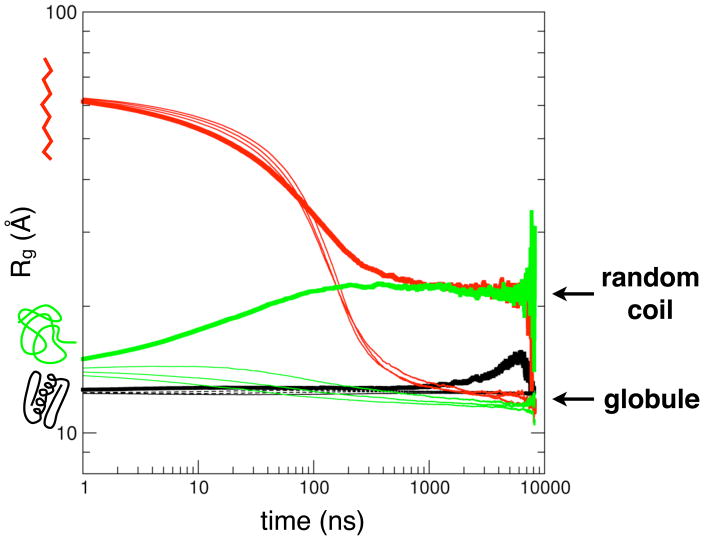

Simulations started from extended and coil conformations both produce well-converged ensembles by 1 μs. The 300K, 330K and 370K simulations reach a collapsed compact globule state with Rg value of ≈12.2Å, while the 450K simulations converge to a random-coil ensemble (Rg ≈ 21.8Å) (Figure 1). It should be noted that simulated temperatures do not correspond to experimental temperatures (discussed below). Single-exponential fits of the average Rg over time yield apparent collapse times of ~100 ns, although longer relaxations up to ~1 μs are evident from the time course as shown on a logarithmic scale. The fast rate is consistent with collapse times observed for BBL after T-jump44 and the rate generally expected from measurements of loop formation in unstructured peptides14,16. The overall dynamics is qualitatively consistent with ultrafast microfluidic mixing experiments showing collapse dynamics on time scales less than the dead time of ~4 μs plus a slower 50 μs decay due to a rough landscape in the unfolded basin45.

Figure 1. Convergence of simulated unfolded ensembles.

Average values of the radius of gyration (Rg) over time for simulated ensembles starting from native (black), extended (red) and coil (green) conformations. Non-native ensembles simulated at 300K, 330K and 370K (thin lines) converge to a compact globule state (Rg≈12.2Å) on the microsecond time scale, while the 450K (thick lines) ensembles converge to a random-coil state with Rg ≈ 21.8Å.

Probability distributions for the intermolecular distance between residues W47 and T57 and residues K23 and W47 (Figure 2a) for simulated ensembles started from extended and coil states are converged by 1 μs (Figures 2b and S2). To quantify the convergence of the distributions over time, we computed the relative entropies of Pext(r) and Pnative(r) with respect to the reference distribution P0(r)=Pcoil(r) over time, computed as ∫drP(r)log[P(r)/P0(r)] (Figure 2c). Smaller values of relative entropy reflect more similar distributions. The relative entropy metric decays roughly exponentially to small values only after 100 ns, explaining why shorter 10 ns trajectories (Figure 2d) fail to produce converged ensembles.

Calibration of simulated temperature and experimental denaturant concentration

Flory-like polymer theory models of the coil-globule transition have been used previously11,46,47 to describe the expansion of the unfolded state observed as denaturant concentration increases. In these models, there are two competing effects: 1) mixing entropy, which favors the insertion of chain monomers into solvent, and 2) the (disfavorable) transfer free energy of inserting a chain monomer into solvent. Using a model adapted from Sanchez48, Ziv and Haran have recently calculated (per-monomer) transfer free energies46 for protein L as a function of denaturant, ε([GdnHCl]), from the chain expansion seen in published smFRET experiments11,12. In a similar fashion, we employed two closely-related polymer theory approaches in the literature46,49 to calculate the per-monomer transfer free energy as a function of temperature ε(T) that best fits the chain expansion we observe in our unfolded-state simulations as temperature increases. By comparing ε([GdnHCl]) and ε(T), we were able to find the effective denaturant concentration ([GdnHCl]) corresponding to an ensemble simulated at a given temperature (T). Our analysis showed that the sharp transition from globule to coil seen in the simulations requires a temperature-dependent model of the transfer free energy ε(T) = ε0 − (T−T0)ΔS, where we found the parameters ε0 and ΔS by least-squares fitting (with T0=300K). Based on this analysis we conclude that the simulated unfolded ensembles at low temperatures correspond to unfolded ensembles near zero concentration of denaturant, whereas the 450K ensembles correspond to [GdnHCl] ≈ 3.2M ± 1M (see Supporting Information).

The polymer theory modeling produces fits with ε(T) several kcal/mol above the published ε([GdnHCl]) values, suggesting that compact states are over-stabilized by the GBSA model, causing artificially high melting temperatures with sharp transitions, an effect which has been observed in other high-temperature GBSA simulations28,50. Since the most commonly available GB models have typically been parameterized using small-molecule hydration free energies, we believe there is much room for improvement in GB models for large protein simulations. More sophisticated GB models that account for solvent dispersion interactions and shape-dependent cavitation free energies could improve unfolded-state simulation models significantly51.

Residual structure in unfolded states

There appears to be a consensus in the field that the large-scale conformational distribution of highly denatured states are well described by wormlike or freely-jointed chains restricted by excluded volume4,25. In the past, much of the work on unfolded states of proteins had focused on the question of whether native-like structure exists in unfolded states, and whether such pre-organization could help explain how proteins are able to overcome the conformational search problem. There has been disagreement as to the extent of residual structure in proteins unfolded by chemical denaturants52, although the mutual existence of local structure and random-coil scaling4,53 are thought to be compatible. Indeed, conformational ensembles generated from models with native-state bias exhibit random-coil scaling, with Rg values comparable to those measured in SAXS experiments24,54.

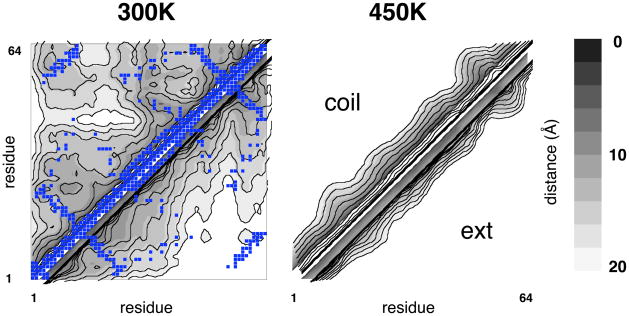

The residual structuring found in the simulations supports the idea that native-like structures can exist within disordered protein states. Average Rg calculated for all pairs (i, j) of inter-residue (Cα) distances were used to find the best fit to the power-law Rg ∝|i−j|ν to extrapolate the scaling coefficient ν. For the 450K ensemble, we found ν=0.59, very close to the expected ν=0.588 for a random-coil chain with excluded volume55. For the 300K ensemble, we found ν=0.37, close to the expected ν=1/3 for a compact spherical globule. At the same time, residue pairs participating in native contacts were found to be closer on average than non-native contacts (Figure S3), when compared to the average Rg provided by the scaling law fits.

A plot of all average inter-residue distances on a contour map shows long-range variations corresponding in part to native contacts (Figure 3). Such structuring mostly vanishes for the expanded 450K ensembles, although some residual turn structure remains. The initial coil and extended ensembles show similar kinds of native-like residual structure after 1 μs, although more long-range structure is apparent in the ensemble started from compact coil states (Figure S4). It is unclear whether the long-range structuring seen in the globule state constitutes any tertiary structure formation per se, as secondary structure formation may bias average long-range distances, and chain compaction could increase the probability of end-to-end contacts.

Figure 3. Residual structuring in compact unfolded states.

Average distances in the 350K and 450K ensembles for all residue pairs, shown on a contour map. Calculations were made from snapshots taken after 1 μs were from simulations starting from an extended state (lower right), and random-coil states (upper left). Superimposed on the 300K data is a native contact map computed from the native structure 2PTL using the CMA server at http://ligin.weizmann.ac.il/cma/.

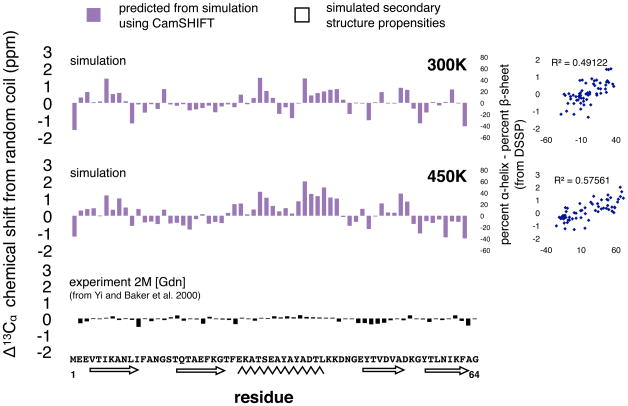

Secondary structure propensities for the 300K and 450K ensembles calculated using the DSSP algorithm56 show mostly native-like helix and sheet propensities (Figure 4). One exception is the N-terminal region, which shows alpha-helix propensity in the unfolded state, potentially stabilized by Glu-Lys salt bridges. The 300K ensemble shows less secondary structure than the 450K ensemble, which has more helical structure in particular (Figure S5), Whereas the 300K ensemble is a very compact globular state with many non-specific nonlocal interactions that overcome the local torsional preferences of the chain, the 450K ensemble is a random-coil that is much more freely diffusing and with fewer nonlocal contacts, allowing the chain to better satisfy its local torsional preferences at high temperature. The temperature-independence of GBSA solvation may further facilitate this effect.

Figure 4. Simulations show more secondary structure in the absence of denaturant compared with experimental chemical shifts in 2M GdnHCl.

Secondary structure propensities of the 300K (top) and 450K (middle) ensemble started from the extended state (black outline), plotted against predicted chemical shifts from the CamSHIFT algorithm (purple bars). Propensities are calculated as percent α-helix minus percent β-sheet, using the DSSP algorithm. The correlation between simulated propensities and predicted chemical shifts is shown to the right. (c) Chemical shift deviations from random coil in 2M GdnHCl, as measured experimentally by Yi et al. (2000). Random coil values in all figures are from Wishart and Sykes (1994).

We find that the simulated ensembles at both 300K and 450K exhibit more secondary structure in the absence of denaturant than measured experimentally in 2M GdnHCl. To compare the structuring seen in the simulations to previous experimental measurements of NMR chemical shifts in denaturant53, we used the CamSHIFT algorithm to predict Δ13Cα chemical shift deviations from random-coil values 57 using the coordinate snapshots (Figure 4). We found CamSHIFT to be more accurate than the SHIFTX and SPARTA algorithms for this purpose (Figure S6). We note that these results might also reflect enhanced secondary structure in the simulations due to forcefield effects such as torsional biases, or due to compaction itself.

Surprisingly slow intermolecular contact rates in denatured states

We performed Trp-Cys quenching studies using two protein L constructs, T57C and K23C, each of which were engineered to have a single cysteine mutation at least 10Å from W47 in the folded structure. Under conditions in which at least some of the protein population is unfolded, tryptophan triplet kinetics exhibit a rapid decay due to contact quenching of the tryptophan by cysteine within an unfolded chain and a slower (~40 μs) decay due to the natural decay of the triplet within the folded state. The observed rate is determined by both the rate of intramolecular diffusion, which brings the excited tryptophan and the cysteine residues together with a diffusion-limited forward rate kD+, and a reaction-limited rate kR due to irreversible quenching which occurs only when the residues are in close contact. The observed rate kobs can be written as

| (1) |

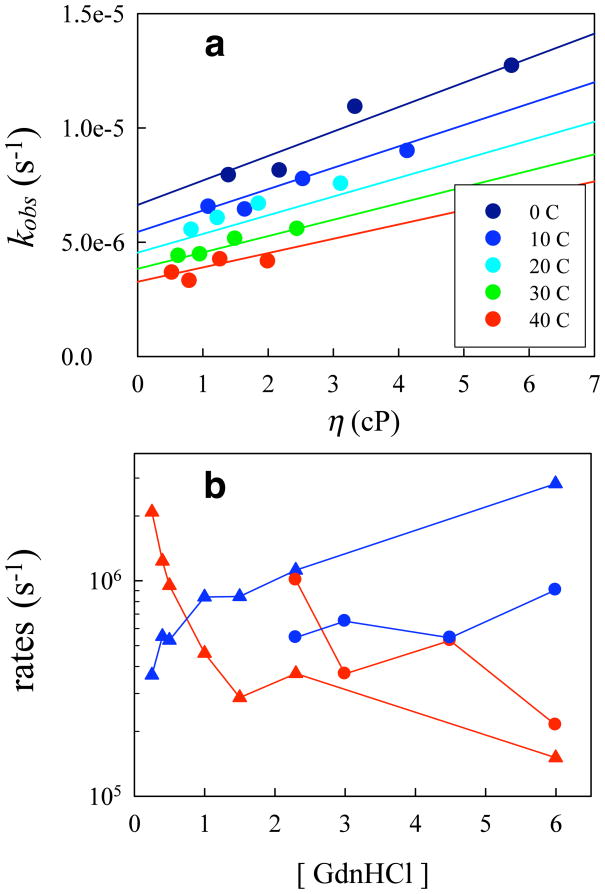

where we assume that the reaction limited rate, kR, depends only on temperature and kD+ depends on both temperature and viscosity26. By varying temperature and viscosity, it is possible to determine these quantities by fitting 1/kobs vs. viscosity (η) at constant temperature to a line with intercept equal to 1/kR and slope equal to 1/ηkD+ (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

(a) Measured tryptophan triplet rates of F22A in 1.5 M GdnHCl at various temperatures and viscosities. The lines are a global fit to Eq. S3 and S4. (b) Reaction-limited (red) and diffusion-limited (blue) rates of K23C (circles) and F22A K23C (triangles) at various concentrations of GdnHCl.

Whereas kD+ is a measure of the time scale of chain reconfiguration in the unfolded state, kR reflects the fraction of the unfolded state population with particular residues in close contact. Thus, these two quantities give a very sensitive measure of both dynamical and structural information about protein unfolded states. See Supplemental Information for details about experimental determination of these rates.

The values of kD+ and kR (circles) plotted in Figure 5b are taken from reference20 and are limited to fairly high denaturant concentrations because the protein population must be at least 20% unfolded to accurately measure kobs. Therefore we added the destabilizing mutation F22A to the K23C mutant, which is partially unfolded at denaturant concentration as low as 0.25 M GdnHCl. The diffusion-limited and reaction-limited rates for K23C F22A are plotted as triangles in Figure 5b. These data show a significant increase in kR and decrease in kD+ with decreasing denaturant at [GdnHCl] < 2 M, indicating compaction and loss of diffusivity. At higher [GdnHCl] we see that kR is lower and kD+ is higher for the mutant than for the wildtype.

These results are remarkable for two reasons. First is the extremely slow rate of intramolecular diffusion, decreasing over an order of magnitude as denaturant is decreased. Extrapolating this trend suggests that in the absence of denaturant, folding rates may be limited by low diffusivity. Second, our results show that a single mutation of a hydrophobic residue significantly expands the ensemble and increases the intramolecular diffusivity. Such an extensive change in the unfolded state raises interesting questions about biophysical processes in which the structure and dynamics of folding may be fine-tuned specifically by unfolded state effects58,59. Intrinsically unstructured proteins, for example, may rely on such tuning to efficiently couple folding and binding60,61.

Experiment and simulation make quantitative predictions of unfolded state structure and dynamics

To compare the observed dynamics to those calculated by MD, we use a theory by Szabo, Schulten and Schulten (SSS) that models intramolecular dynamics as diffusion on a one-dimensional potential determined by the probability distribution of the observed intramolecular pair16,62. The reaction-limited and diffusion-limited rates are then given by

| (2) |

| (3) |

where r is the distance between the tryptophan and cysteine and P(r) is the probability density of finding the polypeptide at that distance, calculated from the simulation. D is the effective intramolecular diffusion constant, a is the distance of closest approach (defined to be 4.5 Å), and q(r) is the distance dependent quenching rate. The distance-dependent quenching rate for the Trp-Cys system has been determined experimentally and drops off very rapidly beyond 4.5 Å, so the reaction-limited rate is mostly determined by the probability of the shortest distances63.

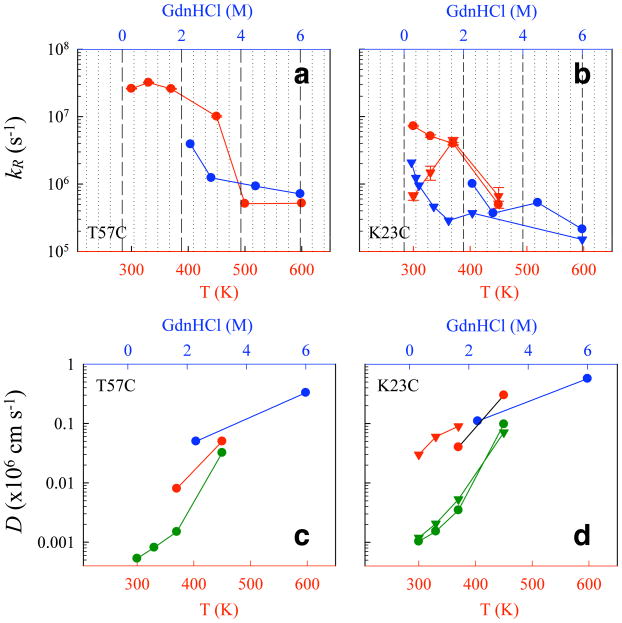

To present the comparison between the reaction-limited rates from experiment and simulation, we align the temperature and [GdnHCl] axes on the same plot according to the polymer theory calibration above, with simulated temperature 300K corresponding to 0M [GdnHCl] and 450K corresponding to 3.2M (Figure 6). We see remarkable agreement between kR from measurement (using Eq. 3) and simulation (using Eq. 5) in the denatured-state regime, where there is overlap of simulated and experimental ensembles. Simulations at low temperature corresponding to the absence of denaturant predict a compact globular state with kR values increased by an order of magnitude.

Figure 6. Comparison of unfolded state dynamics computed from simulation and experiment.

(a,b) Reaction-limited rates kR for loops (a) T57C and (b) K23C measured in various concentrations of (GdnHCl) (blue), and calculated from simulated P(r) (red) using Eq. 2. Wildtype values are shown as circles, F22A values as triangles. The 500K and 600K predicted values included in (a) are from standard MD simulations. (c, d) Three calculations of intermolecular diffusion coefficients D for loops (c) T57C and (d) K23C are compared here: the average D after 1 μs calculated from simulated mean squared displacement over time (green); a “hybrid” D calculated using Eq. 3 from the simulated P(r) and measured kD+ (red); and D calculated from ref 20 in which a wormlike chain model was used to match the measured P(r) at a particular [GdnHCl] (blue).

We find that all-atom simulations are sensitive enough to predict differences in unfolded-state structure and dynamics due to single-residue mutations. At lower simulation temperatures (300K and 330K), we predict kR values for F22A that show an expanded ensemble compared to wildtype, consistent with experiment. However, at higher simulation temperatures the predicted kR values differ only slightly from wildtype values (Figure 6a and b).

Structural comparison of the simulated wildtype and F22A ensembles offers a biophysical hypothesis for the differences in unfolded state. Simulations at 300K show an increase in local helicity near F22A, and an increase in average inter-residue distances between residues in central helix and C-terminal hairpin (Figure S7). These changes are consistent with a model in which the F22A mutation disrupts long-range hydrophobic core interactions, increasing intramolecular diffusivity. Simulated Rg values for F22A after 1 μs are only ~5% larger than wildtype, which is consistent with forthcoming smFRET studies showing minimal changes in mean-FRET compared to wildtype. This comparison also further demonstrates that the Trp-Cys method is more sensitive to small changes in the unfolded state distribution.

Simulated and experimental values of the intramolecular diffusion coefficient D are shown in Figure 6c and d. Simulated diffusion coefficients (green) were calculated directly from the trajectory data by fitting the mean square displacements of Trp-Cys distances over time in 50-ns windows. These values decrease over time, equilibrating after ~1 μs (Figure S8), so we compute D as the average value after this time. We also computed a “hybrid” value of D using Eq. 3 with the experimental value for kD+, and the simulated values of P(r) (red). These were compared to values of D calculated in reference20 using a wormlike chain model (blue). For purposes of comparison, the hybrid values use the P(r) of the simulated 300K, 330K and 370K ensembles with the kD+ measured at 0.25M, 1.5M, and 2.3M GdnHCl, respectively.

The values of D from the 450K simulations, which we calibrated to ~3.2M GdnHCl using polymer theory, agree well with the measured values at 3.0M GdnHCl, for all three methods. For lower temperatures, the estimates of D from simulation are lower than the experimental and “hybrid” values. Since there is reasonably good agreement for kR at low simulated temperatures, we must conclude that the diffusion coefficients calculated from mean square displacement are artificially low. Consistent with this conclusion are inter-residue autocorrelation times in simulated ensembles after 1 μs that we calculate to be on the ~100 ns timescale (Table S1). An inspection of our unfolded-state molecular dynamics simulations shows that over time, the chain occupies many long-lived, compact globular conformations stabilized by nonspecific nonlocal interactions. Thus, we interpret the low simulated values of the diffusion coefficient as mainly a thermodynamic effect, due to the fact that GBSA models overstabilize compact states, in turn slowing the dynamics of chain rearrangement. We note that other, more subtle effects may also be present, such as the lack of hydrodynamic interactions64. The plotted values of D versus temperature calculated from simulation by mean-squared-displacement (Figure 6c and 6d, green) are not corrected for experimental temperature. If so, the additional decrease in D would further underscore the extent of low intramolecular diffusivity seen in the simulations.

Regardless of these simulation artifacts, the low intramolecular diffusivity we observe is generally consistent with the slow (50 μs) relaxation observed in ultrarapid mixing experiments45. Considering the mean square displacement calculation as a lower limit on D and the SSS calculation as an upper limit and extrapolating logarithmically to low temperatures, we conclude that, under folding conditions, D is at least 1½ and as much as 3 orders of magnitude smaller than under high denaturing conditions.

Conclusion

We have made significant advances in using all-atom molecular simulation as a predictive tool to characterize protein unfolded state dynamics and structure in concert with experiments, in this case, Trp-Cys quenching studies that directly measure intramolecular diffusion for unfolded states of protein L. To overcome the limitations of traditional MD simulations, we used a combination of accelerated simulations on fast graphics processsors and distributed computing to generate converged unfolded-state ensembles, and used a polymer theory method for making specific quantitative connections between experiment and simulation. While the simulated distribution of inter-residue distances gives very good predictions of measured intramolecular contact rates, polymer theory fits to the simulated ensemble data as well as simulated intrachain dynamics suggest that implicit solvent simulations overly stabilize compact states, indicating the need for improved implicit solvent models.

In simulation and experiment, we find that intramolecular diffusion in unfolded states of protein L are very slow compared to highly denatured chains, and that a single-residue mutation can significantly alter unfolded state dynamics and structure. This has wide-reaching implications for the role of the unfolded state in the overall folding reaction, often thought of as an ensemble of rapidly interconverting configurations. Our work suggests a rugged folding landscape in the absence of denaturant, with chain collapse on the 0.1–1 μs time scale, native-like structural heterogeneity, and extremely low diffusion rates that may limit the folding reaction.

The ability for simulation to make quantitative predictions of experiment suggests that the door may now be open to much more detailed study of unfolded states. In the future, we speculate that advanced simulation methods such as those presented here, combined with experiment, will be used to obtain valuable information about unfolded states and folding mechanisms for proteins of key biological importance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Marcus Jäger and Shimon Weiss for valuable feedback and comments on the manuscript. We acknowledge support from NSF FIBR (NSF EF-0623664), NSF MCB (NSF MCB-0825001) and NIH (NIH U54 GM072970), and the valued contributors of the Folding@Home project. Initial simulations were completed on the High Performance Computing Center at Michigan State University. The research of Lisa Lapidus, Ph.D. is supported in part by a Career Award at the Scientific Interface from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Figures S1–S8; Table S1; detailed descriptions of GPU and CPU simulation methods, Trp-Cys quenching experimental materials and methods; methods for calibrating simulated unfolded ensembles with experiment. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Contributor Information

Lisa J. Lapidus, Email: lapidus@msu.edu.

Vijay S. Pande, Email: pande@stanford.edu.

References

- 1.Meier S, Blackledge M, Grzesiek S. J Chem Phys. 2008;128:052204. doi: 10.1063/1.2838167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mittag T, Forman-Kay JD. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plaxco KW, Millett IS, Segel3 DJ, Doniach S, Baker D. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:554–556. doi: 10.1038/9329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kohn JE, Millett IS, Jacob J, Zagrovic B, Dillon TM, Cingel N, Dothager RS, Seifert S, Thiyagarajan P, Sosnick TR, Hasan MZ, Pande VS, Ruczinski I, Doniach S, Plaxco KW. PNAS. 2004;101:12495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403643101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohana-Borges R, Goto NK, Kroon GJA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:1131–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohnishi S, Lee AL, Edgell MH, Shortle D. Biochemistry. 2004;43:4064–4070. doi: 10.1021/bi049879b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shortle D, Ackerman MS. Science. 2001;293:487–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1060438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felitsky DJ, Lietzow MA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. PNAS. 2008;105:6278–6283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710641105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song J, Guo LW, Muradov H, Artemyev NO, Ruoho AE, Markley JL. PNAS. 2008;105:1505–1510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709558105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schuler B, Lipman EA, Eaton WA. Nature. 2002;419:743–747. doi: 10.1038/nature01060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sherman E, Haran G. PNAS. 2006;103:11539–11543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601395103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merchant KA, Best RB, Louis JM, Gopich IV, Eaton WA. PNAS. 2007;104:1528–1533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607097104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sherman E, Itkin A, Kuttner YY, Rhoades E, Amir D, Haas E, Haran G. Biophys J. 2008;94:4819–4827. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.120220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bieri O, Wirz J, Hellrung B, Schutkowski M, Drewello M, Kiefhaber T. PNAS. 1999;96:9597–9601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hudgins RR, Huang F, Gramlich G, Nau WM. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:556–564. doi: 10.1021/ja010493n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lapidus LJ, Eaton WA, Hofrichter J. PNAS. 2000;97:7220–7225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JC, Langen R, Hummel PA, Gray HB, Winkler JR. PNAS. 2004;101:16466–16471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407307101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neuweiler H, Schulz A, Böhmer M, Enderlein J, Sauer M. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:5324–5330. doi: 10.1021/ja034040p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buscaglia M, Schuler B, Lapidus LJ, Eaton WA, Hofrichter J. J Mol Biol. 2003;332:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00891-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh VR, Kopka M, Chen Y, Wedemeyer WJ, Lapidus LJ. Biochemistry. 2007;46:10046–10054. doi: 10.1021/bi700270j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nettels D, Gopich IV, Hoffmann A, Schuler B. PNAS. 2007;104:2655–2660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611093104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo L, Chowdhury P, Glasscock JM, Gai F. J Mol Biol. 2008;384:1029–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JC, Lai BT, Kozak JJ, Gray HB, Winkler JR. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:2107–2112. doi: 10.1021/jp068604y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Z, Plaxco KW, Makarov DE. Biopolymers. 2007;86:321–328. doi: 10.1002/bip.20747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buscaglia M, Lapidus LJ, Eaton WA, Hofrichter J. Biophys J. 2006;91:276–288. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.071167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lapidus LJ, Steinbach PJ, Eaton WA, Szabo A, Hofrichter J. J Phys Chem B. 2002;106:11628–11640. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jha AK, Colubri A, Freed KF, Sosnick TR. PNAS. 2005;102:13099–13104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506078102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindorff-Larsen K, Kristjansdottir S, Teilum K, Fieber W, Dobson CM, Poulsen FM, Vendruscolo M. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3291–3299. doi: 10.1021/ja039250g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zagrovic B, Snow CD, Khaliq S, Shirts MR, Pande VS. J Mol Biol. 2002;323:153–164. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00888-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Camilloni C, Sutto L, Provasi D, Tiana G, Broglia RA. Protein Sci. 2008;17:1424–1433. doi: 10.1110/ps.035105.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marsh JA, Neale C, Jack FE, Choy WY, Lee AY, Crowhurst KA, Forman-Kay JD. J Mol Biol. 2007;367:1494–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeSimone A, Richter B, Salvatella X, Vendruscolo M. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3810–3811. doi: 10.1021/ja8087295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dedmon MM, Lindorff-Larsen K, Christodoulou J, Vendruscolo M, Dobson CM. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:476–477. doi: 10.1021/ja044834j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown S, Fawzi NJ, Head-Gordon T. PNAS. 2004;100:10712–10717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1931882100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Das P, Matysiak S, Clementi C. PNAS. 2005;102:10141–10146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409471102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Brien EP, Ziv G, Haran G, Brooks BR, Thirumalai D. PNAS. 2008;105:13403–13408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802113105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Spoel D, Lindahl E, Hess B, Groenhof G, Mark AE, Berendsen] HJC. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1701–1718. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friedrichs MS, Eastman P, Vaidyanathan V, Houston M, Legrand S, Beberg AL, Ensign DL, Bruns CM, Pande VS. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:864–872. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang J, Cieplak P, Kollman PA. J Comput Chem. 2000;21:1049–1074. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duan Y, Wu C, Chowdhury S, Lee MC, Xiong G, Zhang W, Yang R, Cieplak P, Luo R, Lee T, Caldwell J, Wang J, Kollman P. J Comput Chem. 2003;24:1999–2012. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Onufriev A, Bashford D, Case D. Proteins. 2004;55:383–394. doi: 10.1002/prot.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shell MS, Ritterson R, AK J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:6878–6886. doi: 10.1021/jp800282x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scalley ML, Yi Q, Gu H, McCormack A, III, JRY, Baker D. Biochemistry. 1997;36:3373–3382. doi: 10.1021/bi9625758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sadqi M, Lapidus LJ, Muñoz V. PNAS. 2003;100:12117–12122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2033863100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waldauer SA, Bakajin O, Ball T, Chen Y, DeCamp SJ, Kopka M, Jäger M, Singh VR, Wedemeyer WJ, Weiss S, Yao S, Lapidus LJ. HFSP Journal. 2008;2:388–395. doi: 10.2976/1.3013702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ziv G, Haran G. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:2942–2947. doi: 10.1021/ja808305u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ziv G, Thirumalai D, Haran G. PCCP. 2009;11:83–93. doi: 10.1039/b813961j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanchez IC. Macromolecules. 1979;12:980–988. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dill KA. Biochemistry. 1985;24:1501–1509. doi: 10.1021/bi00327a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pitera JW, Swope W. PNAS. 2003;100:7587–7592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1330954100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen J, III, CLB PCCP. 2008;10:471–481. doi: 10.1039/b714141f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCarney ER, Kohn JE, Plaxco KW. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;40:181–189. doi: 10.1080/10409230591008143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yi Q, Scalley-Kim ML, Alm EJ, Baker D. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:1341–1351. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fitzkee NC, Rose GD. PNAS. 2004;101:12497–12502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404236101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Le Guillou JC, Zinn-Justin J. Phys Rev Lett. 1977;39:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kabsch W, Sander C. Biopolymers. 1983;22:2577–2637. doi: 10.1002/bip.360221211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wishart DS, Sykes BD. J Biomol NMR. 1994;4:171–180. doi: 10.1007/BF00175245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cho JH, Raleigh DP. J Mol Biol. 2006;359:1437–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brewer SH, Vu DM, Tang Y, Li Y, Franzen S, Raleigh DP, Dyer RB. PNAS. 2005;102:16662–16667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505432102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dyson HJ, Wright EP. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Szabo A, Schulten K, Schulten Z. J Chem Phys. 1980;72:4350–4357. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lapidus LJ, Eaton WA, Hofrichter J. Phys Rev Lett. 2001;87:258101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.258101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Frembgen-Kesner T, Elcock AH. J Chem Theory Comput. 2009;5:242–256. doi: 10.1021/ct800499p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.