Abstract

To clarify whether transduction efficiency and cell type specificity of self-complementary (sc) AAV5 vectors are similar to those of standard, single stranded AAV5 vectors in normal retina, one micro liter of scAAV5-smCBA-GFP vector (1X1012 genome containing particles/ml) and AAV5-smCBA-GFP vector (1X1012 genome containing particles/ml) were subretinally or intravitreally (in both cases through the cornea) injected into the right and left eyes of adult C57BL/6J mice, respectively. On post-injection day (PID) 1, 2, 5, 7, 10, 14, 21, 28 and 35, eyes were enucleated; retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) wholemounts, neuroretinal wholemounts and eyecup sections were prepared to evaluate green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression by fluorescent microscopy. GFP expression following trans-cornea subretinal injection of scAAV5-smCBA-GFP vector was first detected in RPE wholemounts around PID 1 and in neuroretinal wholemounts between PID 2 and 5; GFP expression peaked and stabilized between PID 10-14 in RPE wholemounts and between P14 and P21 in neuroretinal wholemounts with strong, homogeneous green fluorescence covering the entire wholemounts. The frozen sections supported the following findings from the wholemounts: GFP expression appeared first in RPE around PID 1-2 and soon spread to photoreceptors (PR) cells; by PID 7, moderate GFP expression was found mainly in PR and RPE layers; between PID 14 and 21, strong and homogenous GFP expression was observed in RPE and PR cells. GFP expression following subretinal injection of AAV5-smCBA-GFP was first detected in RPE wholemounts around PID 5-7 and in neuroretinal wholemounts around PID 7-10; ssAAV5 mediated GFP expression peaked at PID 21 in RPE wholemounts and around PID 28 in neuroretinal wholemounts; sections from AAV5 treated eyes also supported findings obtained from wholemounts: GFP expression was first detected in RPE and then spread to the PR cells. Peak GFP expression in RPE mediated by scAAV5 was similar to that mediated by AAV5. However, peak GFP expression mediated by scAAV5 in PR cells was stronger than that mediated by AAV5. No GFP fluorescence was detected in any retinal cells (RPE wholemounts, neuroretinal wholemounts and retinal sections) after trans-cornea intravitreal delivery of either scAAV5-GFP or AAV5-GFP. Neither scAAV5 nor AAV5 can transduce retinal cells following trans-cornea intravitreal injection. The scAAV5 vector used in this study directs an earlier onset of transgene expression than the matched AAV5 vector, and has stronger transgene expression in PR cells following subretinal injection. Our data confirm the previous reports that scAAV vectors have an earlier onset than the standard, single strand AAV vectors (Natkunarajah et al., 2008; Yokoi et al., 2007). scAAV5 vectors may be more useful than standard, single stranded AAV vector when addressing certain RPE and/or PR cell-related models of retinal dystrophy, particularly for mouse models of human retinitis pigmentosa that require rapid and robust transgene expression to prevent early degeneration in PR cells.

Keywords: transgene expression, self-complementary AAV, scAAV5, AAV5, subretinal injection, intravitreal injection, photoreceptor, RPE

Introduction

With the progress of molecular biology, more and more homologous genetic defects in human and animals have been characterized. This has greatly added in the development of gene therapies for different kinds of inherited human diseases. Gene therapy for retinal diseases is particularly attractive due to intrinsic features of the retina that lend themselves to gene mediated therapies; specifically, isolated anatomical structure and immunological privilege (Bainbridge et al., 2006; Dinculescu et al., 2005). Though there are several ways to transfect the target ocular tissues and cells with genes, viral vectors, especially the utilizing recombinant adenoassociate virus (rAAV), have become widely used. rAAV has proven to be a good vector for retinal gene therapy due to the lack of pathogenicity, ability to transfect quiescent cells (i.e. neurons, including retinal photoreceptors) and ability to promote long term expression of delivered transgene (Dudus et al., 1999; Bennett et al., 1999). AAV also has the additional advantage of serotype selectivity. By changing the nature of the capsid protein AAV can be targeted to specific cells type and the relative intensity of transduction efficiency can be modulated (Pang et al., 2008a; Yang et al., 2002; Rabinowitz et al., 2002; Davidson et al., 2000; Bainbridge et al., 2003; Auricchio et al., 2001).

Among the 12 reasonably well-studied serotypes, AAV2 and AAV5 are commonly used in the development of gene therapies for retinal diseases in animal models and in ongoing human clinical trials (Bainbridge et al., 2008; Maguire et al., 2008; Cideciyan et al., 2008; Cideciyan et al., 2009a; Pang et al., 2006a; Alexander et al., 2007). In these studies cell specificity was strongly dependent on the site of administration and the AAV serotype used (Pang et al., 2008a; Pang et al., 2006a; Alexander et al., 2007). Subretinal injection of AAV2 and AAV5 resulted in either retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) or photoreceptor (PR) cell transduction, or both, depending on the nature of the promoter and transgene delivered (Pang et al., 2008a; Pang et al., 2006a; Alexander et al., 2007).

In our previous comparative study of AAV2 and AAV5 vector transduction, we found that AAV2 transduced inner retinal cells, including retinal ganglion and Müller cells following trans-sclera intravitreal injection, but only weak gene expression was found following trans-sclera intravitreal injection of AAV5-CBA-GFP vector, and this expression was limited to the injection site (Pang et al., 2008a). This expression pattern may have been mediated by the physical injury associated with injection (Pang et al., 2008a).

Since the leaking of AAV2 vector into the vitreous cavity is a likely scenario during or after subretinal injection, it is important to determine whether there is AAV5-mediated gene expression in the inner retinal cells following trans-cornea intravitreal injection. By utilizing a trans-cornea approach to the vitreous we can avoid injection related retinal injury, and thereby mitigate vector transduction mediated by retinal injury.

Among the animal models of inherited retinal diseases, mouse models are favored for their ease of handling, high reproductive rate and short generation time. Mouse models of retinal degeneration exhibit a high degree of variation i.e., different cellular targets of the gene mutation (RPE versus PR cells versus ganglion cells), as well a variety of mutations within a cell type (for example, PR cells) and different timeframe for the course of retinal degeneration. There are several well studied mouse models with rapid photoreceptor degeneration. For example, PR degeneration starts around postnatal day (P) 7 in rd1 (Caley et al., 1972) and P16 in rd10 mice (Chang et al., 2007; Gargini et al., 2006), and within the following two weeks most of the PR cells are gone. Our previous studies show that cone degeneration also starts very early in rd12 mice (Pang et al., 2005; Pang et al., IOVS 2007 (48): ARVO E-Abstract 1688) and in other cone photoreceptor function loss mouse models (Pang et al., 2008, IOVS 49: ARVO E-Abstract 5355). Because of the technical difficulty and low success rate of subretinal injections in neonatal mice, it is extremely important to achieve therapeutic gene expression as soon as possible in mouse models with aggressive retinal degenerations (Pang et al., 2008b). Rapid expression may also be critical for devastating episodic retinal diseases such as retinal detachment.

When addressing these rapidly degenerating models with tradition, single stranded AAV vectors, arresting the progression of PR degeneration and restoring ERG responses has proven difficult. This is presumably due to the lag in transgene expression intrinsic to these vectors. It has been established that the lag in expression mediated by AAV is at least in part due to the time required to convert the singlestranded viral DNA genome into a double strand DNA molecule in-vivo, which can then serve as a platform for transcription (Ferrari et al., 1996; Fisher et al., 1996).

To overcome this rate-limiting step, self-complementary AAV vector (scAAV) have been developed that package an inverted repeat genome that subsequently folds into a double stranded DNA molecule that is covalently linked on one end (Yokoi et al., 2007; McCarty et al., 2003). Several studies have shown faster onset of expression and overall increased transduction efficiency with scAAV vectors relative to matched AAV vectors. Cell types analyzed have included brain (Fu et al., 2003), liver (Nathwani et al., 2006), muscle (Wang et al., 2003), cancer cells (Xu et al., 2005), and the trabecular meshwork of the eye (Borrás et al., 2006). It has also been shown that scAAV vectors generate quicker and more efficient transgene expression in retinal cells (Yokio et al., 2007; Natkunarajah et al., 2008) compared with standard AAV. It is well established that AAV5 has better transduction efficiency in PR cells than AAV2 (Pang et al., 2008a; Yang et al., 2002; Rabinowitz et al., 2002; Davidson et al., 2000), therefore we chose to compare scAAV5 versus AAV5 matched vectors in the mouse retina. By utilizing a long acting, ubiquitous promoter, smCBA (Pang et al., 2008b), and evaluating both wholemounts (RPE and neuroretinal) and eye-cup cross-sections we were able to compare efficiency in both RPE and PR cells.

METHODS

Animals

C57BL/6J mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and bred at Wenzhou Medical College (Wenzhou, China). All mice were maintained in the Animal Facilities of Wenzhou Medical College under a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. One hundred and forty, 6–8 weeks old C57BL/6J mice were used in this study; at least three eyes were evaluated for each time point of the experiment. All experiments were approved by the Wenzhou Medical College’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were conducted in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Production of AAV5 and scAAV5 vectors

Standard and self-complementary versions of pseudotyped AAV5 capsid were manufactured and purified in accordance with previously published methods (Flannery et al., 1997; Zolotukhin et al., 1996; Zolotukhin et al., 2002). The matched vectors contained the small version of the hybrid CMV-chicken beta-actin promoter (smCBA) driving the humanized green fluorescent protein (hGFP) cDNA. smCBA (Pang et al., 2008b) has been shown to have identical transduction and tropism characteristics to the full chimeric CMV-chicken beta-actin (CBA) promoter when driving transgene expression in mouse retina (Pang et al., 2008b; Haire et al., 2006; Petrs-Silva et al., 2009). The vector plasmid containing modifications to allow for self-complementary AAV packaging has been previously described (McCarty et al., 2003).

Viral preparations had an average titer of 1013 genome-containing viral particles per milliliter (ml). Vector titer was determined by real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Petrs-Silva et al., 2009) and final aliquots were resuspended in balanced saline solution (Alcon Laboratories, Forth Worth TX, USA) containing 0.014% Tween 20. Both scAAV5-smCBA-GFP and ssAAV5-smCBA-GFP vectors were diluted to 1x1012 genome-containing viral particles per ml with the same balanced saline solution before injection.

Subretinal injection and intravitreal injection

One micro liter of scAAV5-smCBA-GFP vector (1X1012 genome containing particles/ml) or AAV5-smCBA-GFP vector (1X1012 genome containing particles/ml) was delivered into the subretinal space or vitreous cavity of right and left eyes of adult C57 BL/6J mice by either trans-cornea subretinal or intravitreal injections (Figure 1), as previously described (Pang et al., 2006a; Li et al., 2009), but with modifications. Briefly, a hole was made on the cornea within the dilated pupil area with a 30 1/2-gauge disposable needle. A 33-gauge blunt needle was introduced through the cornea hole, avoiding the iris and lens, stopping just before reaching the inner retinal surface for intravitreal injection or going deeper into the subretinal space for subretinal injection. The vector suspension was slowly delivered into the vitreous cavity or subretinal space under direct observation aided by a micro-surgery microscope OPMI Pico surgery microscope, (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Subretinal injection-related analysis of GFP expression was only carried out in mice that experienced >90% retinal detachment and minimal injection-related complications. One drop of 1% atropine (Hi-Tech Pharmacal Co. Inc., Amityville, NY) and a small amount of Ophthalmic Ointment with Neomycin, Polymyxin B Sulfates and Dexamethasone (E. Fougera and Co., Melville, NY) were applied to the eye following injection to reduce injection-related inflammation and prevent possible infection.

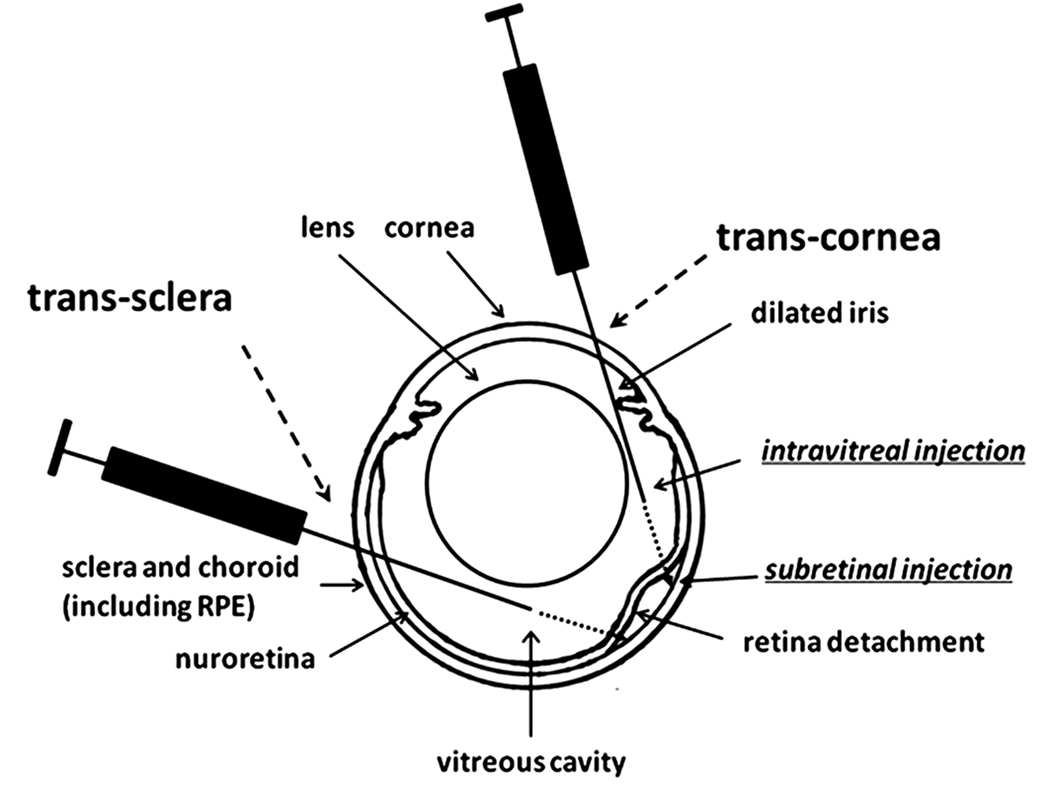

Figure 1.

Diagram of trans-cornea and trans-sclera subretinal/intravitreal injections. This diagram clearly shows that there is no penetration of the retina (and hence damage) via the standard trans-cornea intravitreal injection.

Wholemounts and cryosections

At post-injection day (PID) 1, 2, 5, 7, 10, 14, 21, 28, and 36, mice were sacrificed and their eyes were enucleated and placed into 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline solution (Dulbecco’s PBS; Mediatech, Inc., Herndon, VA). The eyecups were prepared according to previously described methods (Pang et al., 2008a; Petrs-Silva et al., 2009).

Half of the eyecups were used to prepare wholemounts. First, the optic nerve bud and its surrounded sclera were cut from the back of the eyecup with microsurgery scissors. Soft touching and gentle pressing by forceps on sclera of the eyecup were used to help separate the neuroretinal layer from RPE-choroid-sclera layers. When the whole neuroretinal layer was separated from the RPE layer, the eyecup became the neuroretinal wholemount and what remained was the RPE-choroid-sclera wholemount (RPE wholemount). The neuroretinal or RPE wholemounts were prepared by 4 cuts at 3, 6, 9 and 12 O’clock and then flat-mounted on slides and coverslipped before photographing using previously described method (Pang et al., 2008a). Other eyecups were transferred to 30% sucrose in PBS for 2 hours and then transferred into optimal cutting temperature embedding compound (OCT, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). After the embedment was quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen, 12 µm thick sections were obtained with a cryostat. The sections were mounted on gelatin-coated slides and coverslipped using anti-fade Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). GFP-specific fluorescence in wholemounts was analyzed using an Olympus CK40 inverted microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and photographed using a Spot RT (real-time) digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments Color Digital Cameras, McHenry, IL). Background autofluorescence has wider emission spectrum and can be observed by both FITC and Cy3 filters; while green color from GFP expression could be observed by FITC filter only. GFP expression was identified from background autofluorescence by comparing the expression patterns through a FITC and a Cy3 filter.

Image analysis

Images were saved as TIFF files and analyzed using Image J software. GFP fluorescence intensity measurements at each time point were obtained from either RPE or neuroretinal wholemounts. Fluorescence intensity measurements were calculated from 3 different wholemounts, values were averaged and the standard deviation and p-values were determined by an un-paired, two-tailed t-test. Significant differences in fluorescence intensity across samples were obtained by comparing the averages of 3 wholemounts at each time point. Data is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Statistical comparison of fluorescence intensities in GFP expressed PRE and neuroretinal wholemounts at different days following subretinal injection of either scAAV5-smCBA-GFP or AAV5-smCBA-GFP vectors to normal C57BL/6J mice. scAAV5- and AAV5-mediated GFP expressions from RPE wholemounts were at the left columns. scAAV5- and AAV5-mediated GFP expressions from neuroretinal wholemounts were at the right columns. Bars: mean ± SD. Each wholemount was measured (n=3) and averaged to get means at each time point. Standard deviation listed is the standard deviation of the individual wholemount means. P Values were calculated using an unpaired, two-tailed t-test.

| RPE wholemounts (n=3) | Neuroretinal wholemounts (n=3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| scAAV5-smaCBA-GFP | ssAAV5-smCBA-GFP | scAAV5-smCBA-GFP | ssAAV5-smCBA-GFP | ||

| PID 2 | 38.4±4.3 | 20.1±1.8 | PID 2 | 31.3±3.4 | 21.3±1.8 |

| P value | 0.0092 | 0.0208 | |||

| PID 5 | 70.0±4.0 | 36.5±4.3 | PID 7 | 56.2±3.1 | 33.2±4.1 |

| P value | 0.0074 | 0.0203 | |||

| PID 14 | 100.8±4.3 | 58.1±5.3 | PID 14 | 75.7±5.8 | 57.1±3.2 |

| P value | 0.0101 | 0.0188 | |||

| PID 21 | 98.6±4.2 | 92.5±3.6 | PID 21 | 93.7±3.04 | |

| P value | 0.2616 | PID 28 | 77.4±3.8 | ||

| scAAV-PID 14: ssAAV-PID 21; P=0.0918 | P value | 0.0420 | |||

RESULTS

GFP expression in RPE wholemount following subretinal injection

Following subretinal injection of scAAV5-smCBA-GFP, very weak, sparsely distributed GFP expression could be detected with high magnification, especially around the injection site at PID 1 (data not shown); at PID 2 (Fig. 2A), mild GFP expression was observed in more areas. Images were photographed with an exposure time of 6.8 seconds, this exposure setting was used for all subsequent photographs taken of RPE wholemounts; at PID 5-7, moderate GFP expression had spread to most areas (Fig. 2B); by PID 10-14, GFP expression peaked and showed strong, homogeneous green fluorescence throughout the entire wholemount (Fig. 2C); GFP expression remained stable with bright green fluorescence between PID 21 (Fig. 2D) and PID 35 (data not shown).

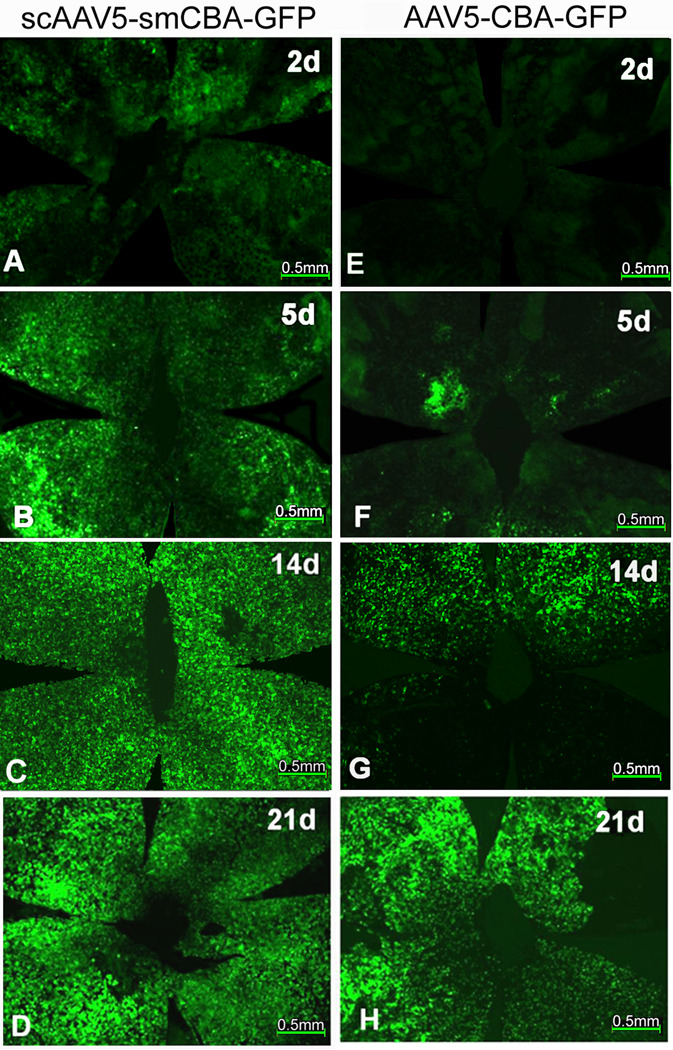

Figure 2.

Time course of GFP expression in RPE wholemounts of C57BL/6J mice after subretinal injection of scAAV5-smCBA-GFP or AAV5-smCBA-GFP vectors.

Fluorescent micrographs of the RPE wholemounts from PID 2 to PID 21 showing a panoramic view of GFP expression in RPE cells from the beginning to the peak time of expression. A-D): RPE whole mounts at PID 2, 5, 14 and 21 following subretinal delivery of scAAV5-smCBA-GFP vectors; E-H: RPE wholemounts at PID 2, 5, 14 and 21 following subretinal delivery of AAV5-smCBA-GFP vectors. The PID is labeled as “d” in each picture.

Following subretinal injection of AAV5-smCBA-GFP vector, GFP expression was undetectable at PID 2 (Fig. 2E); GFP expression was first observed at PID 5 (Fig. 2F) with a similar expression pattern to that of scAAV5-GFP (Fig. 2A). GFP expression increased gradually, and by PID 10-14 mild to moderate GFP expression had spread to more than half of the wholemount area (Fig. 2G); GFP expression peaked with strong, homogeneous green fluorescence throughout the RPE wholemount around PID 21 (Fig. 2H); GFP expression remained stable with strong, homogeneous green fluorescence between PID 28 and 35(data not shown).

GFP expression in neuroretinal wholemount following subretinal injection

Following subretinal injection of scAAV5-smCBA-GFP vector, mild, sparsely distributed GFP expression was first observed in the neuroretinal wholemount, especially around the injection site, at PID 2 (Fig. 3A); Images were photographed with an exposure time of 1.6 seconds, this exposure setting was used for all subsequent photographs taken of neuroretinal wholemounts; GFP expression gradually spread from PID 7 (Fig. 3B) to PID 10; by PID 14, strong GFP expression was observed in most parts of the wholemount (Fig. 3C); by PID 21, GFP expression peaked, with strong, homogenous green fluorescence in the neuroretinal wholemount (Fig. 3D). GFP expression remained stable between PID28 and35 (data not shown).

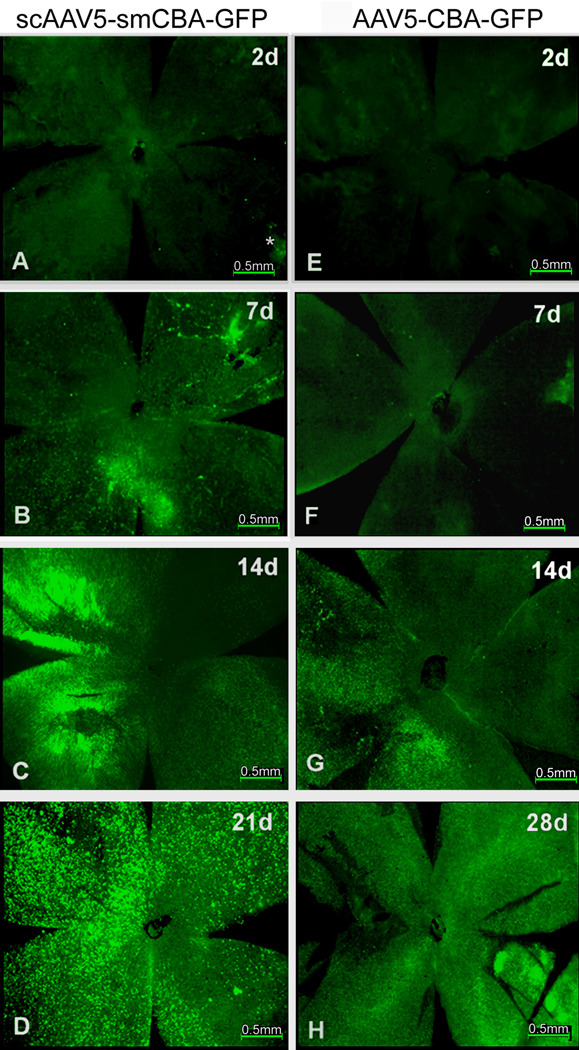

Figure 3.

Time course of GFP expression in neuroretinal wholemounts of C57BL/6J mice after subretinal injection of scAAV5-smCBA-GFP or AAV5-smCBA-GFP vectors.

Fluorescent micrographs of the neuroretinal wholemounts from PID 2 to PID 28 showing a panoramic view of GFP expression in neuroretinal wholemounts from the beginning to the peak time of expression. A-D: neuroretinal wholemounts at PID 2, 7, 14 and 21 following subretinal delivery of scAAV5-smCBA-GFP vectors; E-H: neuroretinal whole mounts at PID 2, 7, 14 and 28 following subretinal delivery of AAV5-smCBA-GFP vectors. The large dark areas in 3E and 3F represent areas where the neuroretina has no GFP fluorescence.

Following subretinal injection of AAV5 vector, no GFP expression was detected at PID2 (Fig. 3E). GFP expression was first observed around PID 7 (Fig. 3F) and showed a similar pattern to that mediated by scAAV5-GFP at PID 2 (Fig. 3A). The AAV5 mediated GFP expression continued to gradually increase at PID 14 (Fig. 3G) and peaked between PID 21 and PID28 (Fig. 3H).

GFP expression in eyecup cross-section following subretinal injection

Cross-sections of eyecups made from eyes following subretinal delivery of scAAV5-smCBA-GFP vectors indicated that GFP positive RPE cells were first detectable at PID 1; GFP positive PR cells were first detected around PID 2, especially around the injection site, which showed obvious signs of injection-related retinal detachment and damage (data not shown). The number of GFP positive RPE and PR cells continued to increase, and by PID 7 (Fig. 4A) more than half of the RPE and PR cells showed mild to moderate GFP expression. It was observed that injection-related damage began diminishing at PID 7, although retinal detachment was still frequently noted during section preparation. By PID 14 most of the RPE and PR cells were transduced, with RPE showing particularly robust GFP expression; in addition retinas at PID 14 appeared to have recovered from the earlier signs of damage attributed to the subretinal injection (Fig. 4B). By PID 21, strong green fluorescence was found not only in the RPE but also in the PR cells, including in the outer nuclear layer (ONL), outer segments (OS) and inner segments (IS) of PR cells (Fig. 4C).

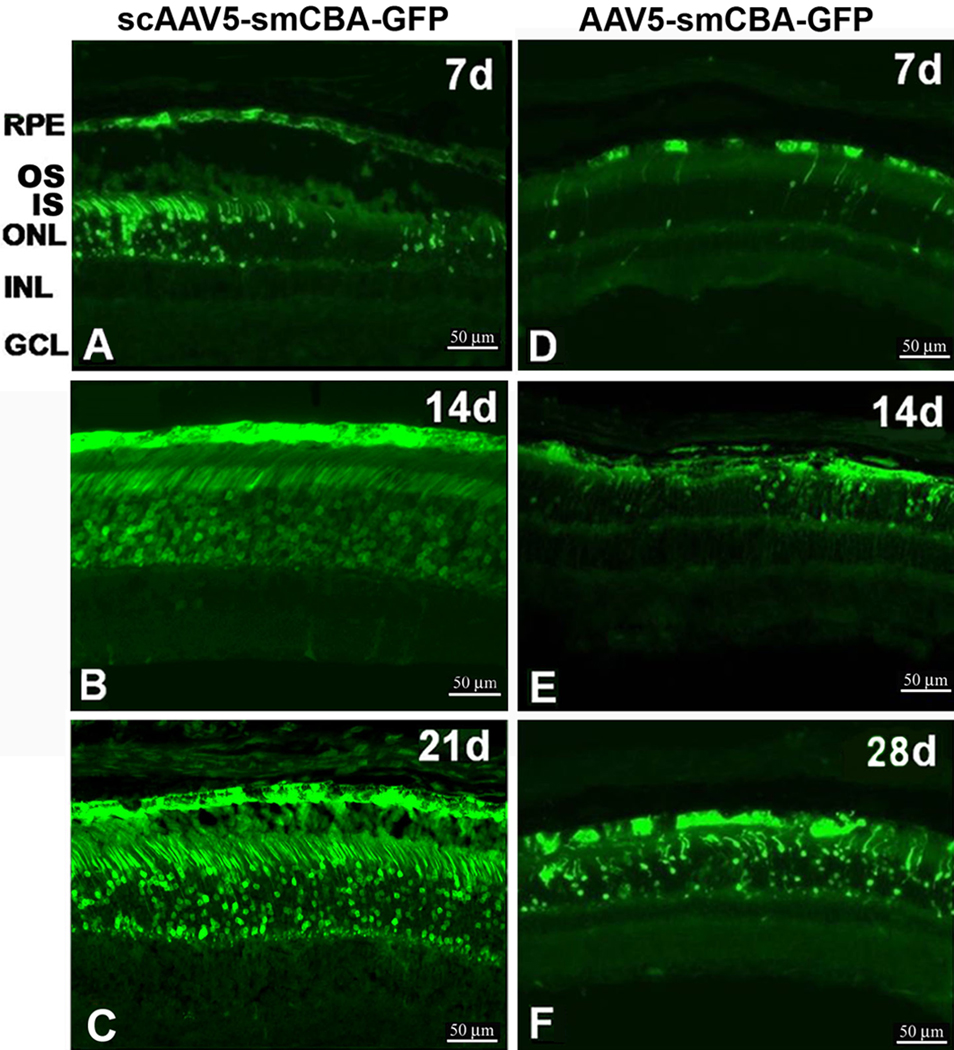

Figure 4.

Time course of GFP expression in eyecup cross-sections of C57BL/6J mice after subretinal injection of scAAV5-smCBA-GFP or AAV5-smCBA-GFP vectors.

Fluorescent micrographs of the cross-sections showing GFP expression from PID 7 to PID 28. A-C: Cross-sections from mice at PID 7, 14 and 21 after subretinal injection of scAAV5-smCBA-GFP. D-F: Cross-sections from mice at PID 7, 14 and 28 after subretinal injection of AAV5-smCBA-GFP vectors. RPE: retinal pigmented epithelium; OS: outer segments of PR cells; IS: inner segments of PR cells; ONL: outer nuclear layer; INL: inner nuclear layer; GCL: retinal ganglion cell layer.

Sections from AAV5 treated eyes supported findings obtained from wholemounts: GFP expression was first detected in RPE and then spread to the PR cells. Small numbers of RPE cells and even fewer PR cells exhibited weak green fluorescence in cross-section at PID 7 after subretinal delivery of AAV5-smCBA-GFP vectors (Fig. 4D); Increasing numbers of GFP positive RPE and PR cells were found at PID 14 (Fig. 4E); most of the RPE and PR cells, especially RPE, showed strong GFP expression at PID 28 (Fig. 4F) and continuing on to PID 35 (data not shown). GFP expression in RPE was stronger than in PR cells at all time points.

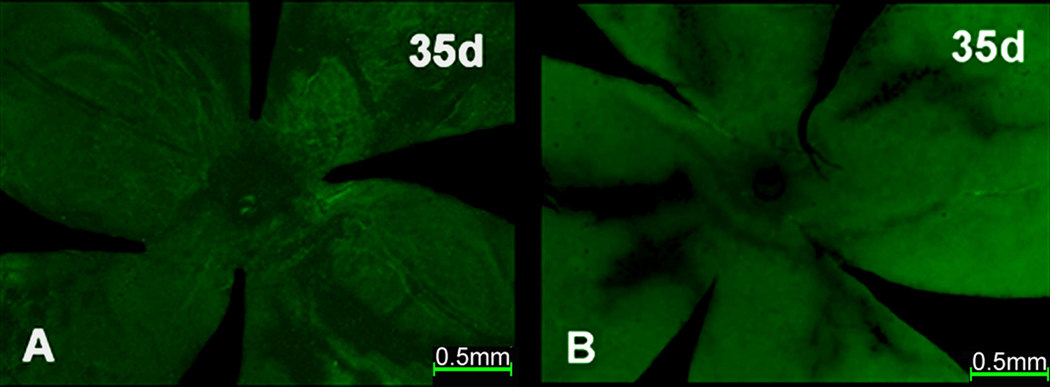

GFP fluorescence in RPE and neuroretinal wholemounts or sections following intravitreal injection

Following trans-cornea intravitreal injection of scAAV5-smCBA-GFP vector, no GFP expression was detected in the eyecup section (data not shown) or in either the RPE (Fig. 5A) or neuroretinal (Fig. 5B) wholemounts by PID 35. Similar results were observed following trans-cornea intravitreal injection of the AAV5-smCBA-GFP vector (data not shown).

Figure 5.

GFP expression in wholemounts of C57BL/6J mice after trans-cornea intravitreal injection of scAAV5-smCBA-GFP vectors.

Fluorescent micrographs of the whole mounts at PID 35 showed no GFP expression either in RPE (A) or neuroretinal (B) wholemounts.

Quantification of GFP expression in RPE and neuroretinal wholemounts

Table 1 shows that scAAV5-mediated GFP expression in RPE was significantly stronger than that of AAV5 at PID 2, 5 and 14 (P<0.05); however no statistical difference was found when comparing scAAV-PID14 vs. AAV-PID21 (P=0.0918) when both vectors had reached peak expression in RPE, or when comparing respective vectors at PID21 (P=0.2616). By PID 14, scAAV5-mediated GFP expression in PR cell was significantly stronger than that of AAV5 (Table 1, P<0.05); scAAV5-mediated GFP expression in PR cells at P21 was significantly stronger than that of AAV5 at P28, when both vectors had reached peak expression (P<0.05).

DISCUSSION

It is already known that scAAV vectors elicit a more rapid onset of transgene expression relative to traditional AAV vectors. In this study, we expand upon this knowledge by specifically comparing scAAV and AAV vectors packaged in an AAV serotype with a well established affinity for retinal cells, AAV5 (Pang et al., 2008a; Yang et al., 2002; Rabinowitz et al., 2002; Davidson et al., 2000), and utilizing a shortened version of a promoter, chimeric CMV-chicken beta-actin (CBA), which is reported to be safe, effective and persistent when used in proof of concept experiments and clinical trials of retinal disease (Bainbridge et al., 2008; Maguire et al., 2008; Cideciyan et al., 2008; Cideciyan et al., 2009a; Pang et al., 2008b; Haire et al., 2006; Li et al., 2009).

Even small differences in the titer of delivered vector can influence transduction efficiency. In order to fairly compare the differences in transduction efficiencies between two vectors, both vector stocks were titered within the same laboratory in identical fashion, they were then diluted from high concentration stocks (~1x1013 genome containing particles/ml) to 1x1012 genome containing particles/ml just prior to injection. In addition, we chose only those subretinally injected eyes which had >90% retinal detachment for the evaluation of wholemounts. Since both vectors only transduce RPE in the RPE-choroid-sclera layers following subretinal injection, we simply refer to this as RPE wholemount to compare the GFP expression in RPE layer. We found that scAAV5-mediated GFP expression in neuroretina was statistically stronger than that of the AAV when both had reached peak expression (Table1). Since both vectors only transduce PR cells in neuroretina, this suggests that scAAV5 vectors are better at PR transduction than AAV vectors. These results support the use of scAAV5 vectors as the preferred choice for rescuing mouse models with early rod or cone degeneration (Chang et al., 2007; Gargini et al., 2006; Pang et al., 2005; Pang et al., IOVS 48: ARVO E-Abstract 1688; Pang et al., 2008, IOVS 49: ARVO E-Abstract 5355).

In a previous report, stronger GFP expression was observed in RPE following subretinal injection of scAAV5 vector as compared with that of AAV5 (Natkunarajah et al., 2008). We also found significantly stronger expression in RPE with our scAAV5 vector at PID 2, 5 and 14. (Table 1) In order to better evaluate early GFP expression we uniformly used a long exposure time, in so doing we were able to clearly observe GFP signal as early as PID 2. However, this may be the reason that a statistical difference in GFP expression in RPE at PID 21, when both vectors had reached peak expression, was not detected.

Although subretinal injection-induced retinal blebs usually diminish after 1 day, retinal detachment and injection-related damage can easily persist up to PID 7, and is extremely common before PID 5 from our experience. For this reason we did not present cross section pictures before PID 7. However, the transient retinal detachment makes it easier to prepare the RPE and neuroretinal wholemounts, which in this case clearly showed GFP expression in RPE and PR cells at time points earlier than PID 7.

In general, our results were consistent with other studies using self-complementary AAV vectors in retina (Yokoi et al., 2007; Natkunarajah et al., 2008). Our data show that scAAV5 and standard AAV5 vectors have similar cell specificity, mainly transducing RPE and PR cells. Transgene expression following subretinal injection of scAAV5-smCBA-GFP was first observed in RPE at PID 1 and in PR cells between PID 2-5. AAV5-mediated GFP expression was first observed in RPE around PID 5-7. Early GFP expression may be related to features specific to RPE, for example, the ability to phagocytize and its monolayer structure. Indeed, we have found that 4 days after subretinal injection of scAAV5 vector containing RPE65 to rd12 mice lacking functional RPE65 protein in retinal pigment epithelial cells, half of the rod ERG amplitude relative to a congenic wildtype mouse can be restored as opposed to no earlier than 12 days after subretinal injection with a matched AAV vector (Pang et al., 2007, IOVS 48: ARVO-E Abstract 1688).

Our data also indicate that scAAV5-mediated GFP expression peaks in PR cells around PID 21, while AAV5 peaks around PID 28. This data would suggest that the onset of transgene expression mediated by the scAAV5 vector is about 1 week faster than that mediated by the matched AAV5 vector.

Direct intensity comparisons between RPE and neuroretinal wholemounts cannot be made due to the difference in exposure time, cell number and morphology.

It is interesting to note that in this and a previous study of ours we have documented that AAV-mediated GFP expression starts around the injection site and then spreads from RPE to PR cells (Pang et al., 2008a). Increased transduction around the injection site may be a result of increased viral uptake due to a weakened physical barrier following subretinal injection (Pang et al., 2006b).

In a previous study we showed that AAV2 can transduce RPE and PR cells via subretinal injection, and can also transduce retinal ganglion and Müller cells via intravitreal injection (Pang et al., 2008a). Traditional AAV5-mediated GFP expression was only observed around the trans-sclera intravitreal injection site, which may be the result of injection-related damage, because the needle has to penetrate the retina before reaching the vitreous cavity (Pang et al., 2008a). The subretinal space has been shown to be immune-privileged, whereas the vitreous cavity is thought to be only partially immune-privileged (Li et al., 2008; Li et al., 2009). It is important to avoid an immune response following retinal gene therapy, particularly if in the future there is a need for a second dose or treatment of the contralateral eye. In this study, we show that neither scAAV5 nor AAV5 vectors tranduce retinal cells following careful trans-cornea intravitreal delivery. It is important to emphasize that by doing a trans-cornea intravitreal injection, the injection-related retinal injury seen with the trans-sclera methodology is avoided, and hence a lack of spurious transgene expression around the damage site (Figure 1 diagrammatically shows the difference between the two methodologies). The current findings increase our understanding of AAV5 vectors and may benefit ongoing clinical trials of retinal gene therapy, especially therapies for those diseases that require therapeutic gene expression only in RPE and PR cells, such as LCA2 (RPE expression) (Bainbridge et al., 2008; Maguire et al., 2008; Cideciyan et al., 2008; Cideciyan et al., 2009a; Cideciyan et al., 2009b) and Achromatopsia (cone expression) (Alexander et al., 2007; Pang et al., 2008, IOVS 49: ARVO E-Abstract 5355). Although due to their double stranded nature scAAV5 vector are not suitable for packaging large transgene cassettes (Wu et al., 2007), they are beneficial for those gene therapies that require a fast onset of transgene expression, and that have appropriate sized promoters and genes (Pang et al., 2007, IOVS 48: ARVO E-Abstract 1688).

In summary, we concluded that neither scAAV5 nor AAV5 can transduce retinal cells when delivered to the vitreous in a damage free manner. scAAV5 vector exhibit a faster onset of, as well as stronger transgene expression than standard AAV5 vectors in PR cells. This property along with the specificity for transgene expression in RPE and PR cell make scAAV5 vectors an important candidate for RPE and/or PR-related gene therapy studies, especially for those mouse models with early rod or cone degeneration.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by grants of Major Projects of the National Science and Technology of China (No: 2009ZX09503), Key Projects of National High-Tech R&D Program (863 Program) of China (No: 2007AA021004), retinal gene therapy study grants from Eye Hospital, School of Ophthalmology & Optometry, Wenzhou Medical College, Wenzhou, China and NIH grants EY018331 for partial support of this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

W.W. Hauswirth and the University of Florida have a financial interest in the use of AAV therapies, and own equity in a company (AGTC Inc.) that might, in the future, commercialize some aspects of this work.

REFERENCES

- Alexander JJ, Umino Y, Everhart D, Chang B, Min SH, Li Q, Timmers AM, Hawes NL, Pang J-J, Barlow RB, Hauswirth WW. Restoration of cone vision in a mouse model of achromatopsia. Nat. Med. 2007;13:685–687. doi: 10.1038/nm1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auricchio A, Kobinger G, Anand V, Hildinger M, O'Connor E, Maguire AM, Wilson JM, Bennett J. Exchange of surface proteins impacts on viral vector cellular specificity and transduction characteristics: the retina as a model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:3075–3081. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.26.3075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge JW, Mistry A, Schlichtenbrede FC, Smith A, Broderick C, DeAlwis M, Georgiadis A, Taylor PM, Squires M, Sethi C, Charteris D, Thrasher AJ, Sargan D, Ali RR. Stable rAAV-mediated transduction of rod and cone photoreceptors in the canine retina. Gene Ther. 2003;10:1336–1344. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge JW, Tan MH, Ali RR. Gene therapy progress and prospects: the eye. Gene Ther. 2006;13(16):1191–1197. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge JW, Smith AJ, Barker SS, Robbie S, Henderson R, Balaggan K, Viswanathan A, Holder GE, Stockman A, Petersen-Jones S, Bhattacharya SS, Thrasher AJ, Fitzke FW, Carter BJ, Rubin GS, Moore AT, Ali RR. Effect of gene therapy on visual function in Leber's congenital amaurosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:2231–2239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett J, Maguire AM, Cideciyan AV, Schnell M, Glover E, Anand V, Aleman TS, Chirmule N, Gupta AR, Huang Y, Gao GP, Nyberg WC, Tazelaar J, Hughes J, Wilson JM, Jacobson SG. Stable transgene expression in rod photoreceptors after recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated gene transfer to monkey retina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:9920–9925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrás T, Xue W, Choi VW, Bartlett JS, Li G, Samulski RJ, Chisolm SS. Mechanisms of AAV transduction in glaucoma-associated human trabecular meshwork cells. J. Gene Med. 2006;8:589–602. doi: 10.1002/jgm.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caley DW, Johnson C, Liebelt RA. The postnatal development of the retina in the normal and rodless CBA mouse: a light and electron microscopic study. Am. J. Anat. 1972;133:179–212. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001330205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang B, Hawes NL, Pardue MT, German AM, Hurd RE, Davisson MT, Nusinowitz S, Rengarajan K, Boyd AP, Sidney SS, Phillips MJ, Stewart RE, Chaudhury R, Nickerson JM, Heckenlively JR, Boatright JH. Two mouse retinal degenerations caused by missense mutations in the beta-subunit of rod cGMP phosphodiesterase gene. Vision Res. 2007;47:624–633. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cideciyan AV, Aleman TS, Boye SL, Schwartz SB, Kaushal S, Roman AJ, Pang JJ, Sumaroka A, Windsor EA, Wilson JM, Flotte TR, Fishman GA, Heon E, Stone EM, Byrne BJ, Jacobson SG, Hauswirth WW. Human gene therapy for RPE65 isomerase deficiency activates the retinoid cycle of vision but with slow rod kinetics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:15112–15117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807027105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cideciyan AV, Hauswirth WW, Aleman TS, Kaushal S, Schwartz SB, Boye SL, Windsor EA, Conlon TJ, Sumaroka A, Pang JJ, Roman AJ, Byrne BJ, Jacobson SG. Human RPE65 Gene Therapy for Leber Congenital Amaurosis: Persistence of Early Visual Improvements and Safety at One Year. Hum Gene Ther. 2009a;20:1–6. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cideciyan AV, Hauswirth WW, Aleman TS, Kaushal S, Schwartz SB, Boye SL, Windsor EA, Conlon TJ, Sumaroka A, Roman AJ, Byrne BJ, Jacobson SG. Vision 1 year after gene therapy for Leber's congenital amaurosis. N Engl. J. Med. 2009b;361:725–727. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0903652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson BL, Stein CS, Heth JA, Martins I, Kotin RM, Derksen TA, Zabner J, Ghodsi A, Chiorini JA. Recombinant adeno-associated virus type 2, 4, and 5 vectors: transduction of variant cell types and regions in the mammalian central nervous system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:3428–3432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050581197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinculescu A, Glushakova L, Min SH, Hauswirth WW. Adeno-associated virus-vectored gene therapy for retinal disease. Hum. Gene Ther. 2005;16:649–663. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudus L, Anand V, Acland GM, Chen SJ, Wilson JM, Fisher KJ, Maguire AM, Bennett J. Persistent transgene product in retina, optic nerve and brain after intraocular injection of rAAV. Vision Res. 1999;39:2545–2553. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(98)00308-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari FK, Samulski T, Shenk T, Samulski RJ. Second-strand synthesis is a rate-limiting step for efficient transduction by recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors. J. Virol. 1996;70:3227–3234. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3227-3234.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher KJ, Gao GP, Weitzman MD, DeMatteo R, Burda JF, Wilson JM. Transduction with recombinant adeno-associated virus for gene therapy is limited by leading-strand synthesis. J. Virol. 1996;70:520–532. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.520-532.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery JG, Zolotukhin S, Vaquero MI, LaVail MM, Muzyczka N, Hauswirth WW. Efficient photoreceptor-targeted gene expression in vivo by recombinant adeno-associated virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:6916–6921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H, Muenzer J, Samulski RJ, Breese G, Sifford J, Zeng X, McCarty DM. Self-complementary adeno-associated virus serotype 2 vector: global distribution and broad dispersion of AAV-mediated transgene expression in mouse brain. Mol. Ther. 2003;8:911–917. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargini C, Terzibasi E, Mazzoni F, Strettoi E. Retinal organization in the retinal degeneration 10 (rd10) mutant mouse: a morphological and ERG study. J Comp. Neurol. 2006;500:222–238. doi: 10.1002/cne.21144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haire SE, Pang J, Boye SL, Sokal I, Craft CM, Palczewski K, Hauswirth WW, Semple-Rowland SL. Light-driven cone arrestin translocation in cones of postnatal guanylate cyclase-1 knockout mouse retina treated with AAV-GC1. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006;47:3745–3753. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Miller R, Han P-Y, Pang J, Dinculescu A, Chiodo V, Hauswirth WW. Intraocular route of AAV2 vector administration defines humoral immune response and therapeutic potential. Mol. Vis. 2008;14:1760–1769. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Kong F, Li X, Dai X, Liu X, Wu R, Zhou X, Lu F, Chang B, Li Q, Hauswirth WW, Qu J, Pang J-J. Gene therapy following subretinal AAV vector delivery is not affected by a previous intravitreal AAV vector administration in the partner eye. Mol. Vis. 2009;15:267–275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire AM, Simonelli F, Pierce EA, Pugh EN, Mingozzi F, Bennicelli J, Banfi S, Marshall KA, Testa F, Surace EM, Rossi S, Lyubarsky A, Arruda VR, Konkle B, Stone E, Sun J, Jacobs J, Dell'Osso L, Hertle R, Ma JX, Redmond TM, Zhu X, Hauck B, Zelenaia O, Shindler KS, Maguire MG, Wright JF, Volpe NJ, McDonnell JW, Auricchio A, High KA, Bennett J. Safety and efficacy of gene transfer for Leber's congenital amaurosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:2240–2248. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty DM, Fu H, Monahan PE, Toulson CE, Naik P, Samulski RJ. Adeno-associated virus terminal repeat (TR) mutant generates self-complementary vectors to overcome the rate-limiting step to transduction in vivo. Gene Ther. 2003;10:2112–2118. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathwani AC, Gray JT, Ng CY, Zhou J, Spence Y, Waddington SN, Tuddenham EG, Kemball-Cook G, McIntosh J, Boon-Spijker M, Mertens K, Davidoff AM. Self-complementary adeno-associated virus vectors containing a novel liver-specific human factor IX expression cassette enable highly efficient transduction of murine and nonhuman primate liver. Blood. 2006;107:2653–2661. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natkunarajah M, Trittibach P, McIntosh J, Duran Y, Barker SE, Smith AJ, Nathwani AC, Ali RR. Assessment of ocular transduction using single-stranded and self-complementary recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 2/8. Gene Ther. 2008;15:463–467. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang J-J, Chang B, Hawes NL, Hurd RE, Davisson MT, Li J, Noorwez SM, Malhotra R, McDowell JH, Kaushal S, Hauswirth WW, Nusinowitz S, Thompson DA, Heckenlively JR. Retinal degeneration 12 (rd12): a new, spontaneously arising mouse model for human Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) Mol. Vis. 2005;11:152–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang J-J, Chang B, Kumar A, Nusinowitz S, Noorwez SM, Li J, Rani A, Foster TC, Chiodo VA, Doyle T, Li H, Malhotra R, Teusner JT, McDowell JH, Min SH, Li Q, Kaushal S, Hauswirth WW. Gene therapy restores vision-dependent behavior as well as retinal structure and function in a mouse model of RPE65 Leber congenital amaurosis. Mol. Ther. 2006a;13:565–572. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang J-J, Cheng M, Haire SE, Barker E, Planelles V, Blanks JC. Efficiency of lentiviral transduction during development in normal and rd mice. Mol. Vis. 2006b;12:756–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang J-J, Lauramore A, Deng WT, Li Q, Doyle TJ, Chiodo V, Li J, Hauswirth WW. Comparative analysis of in vivo and in vitro AAV vector transduction in the neonatal mouse retina: effects of serotype and site of administration. Vision Res. 2008a;48:377–385. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang J-J, Boye SL, Kumar A, Dinnnculescu A, Deng W, Li J, Li Q, Rani A, Foster TC, Chang B, Hawes NL, Boatright JH, Hauswirth WW. AAV-mediated gene therapy delays retinal degeneration in the rd10 mouse containing a recessive PDEβ mutation. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis Sci. 2008b;49:4278–4283. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrs-Silva H, Dinculescu A, Li Q, Min SH, Chiodo V, Pang JJ, Zhong L, Zolotukhin S, Srivastava A, Lewin AS, Hauswirth WW. High-efficiency transduction of the mouse retina by tyrosine-mutant AAV serotype vectors. Mol. Ther. 2009;17:463–471. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz JE, Rolling F, Li C, Conrath H, Xiao W, Xiao X, Samulski RJ. Cross-packaging of a single adeno-associated virus (AAV) type 2 vector genome into multiple AAV serotypes enables transduction with broad specificity. J. Virol. 2002;76:791–801. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.2.791-801.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Ma HI, Li J, Sun L, Zhang J, Xiao X. Rapid and highly efficient transduction by double-stranded adeno-associated virus vectors in vitro and in vivo. Gene Ther. 2003;10:2105–2111. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Zhao W, Zhong L, Han Z, Li B, Ma W, Weigel-Kelley KA, Warrington KH, Srivastava A. Self-complementary recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors: packaging capacity and the role of rep proteins in vector purity. Hum. Gene Ther. 2007;18:171–182. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, McCarty D, Fernandes A, Fisher M, Samulski RJ, Juliano RL. Delivery of MDR1 small interfering RNA by self-complementary recombinant adeno-associated virus vector. Mol. Ther. 2005;11:523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang GS, Schmidt M, Yan Z, Lindbloom JD, Harding TC, Donahue BA, Engelhardt JF, Kotin R, Davidson BL. Virus-mediated transduction of murine retina with adeno-associated virus: effects of viral capsid and genome size. J. Virol. 2002;76:7651–7660. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.15.7651-7660.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoi K, Kachi S, Zhang HS, Gregory PD, Spratt SK, Samulski RJ, Campochiaro PA. Ocular gene transfer with self-complementary AAV vectors. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis Sci. 2007;48:3324–3328. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolotukhin S, Potter M, Hauswirth WW, Guy J, Muzyczka N. A "humanized" green fluorescent protein cDNA adapted for high-level expression in mammalian cells. J. Virol. 1996;70:4646–4654. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4646-4654.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolotukhin S, Potter M, Zolotukhin I, Sakai Y, Loiler S, Fraites TJ., Jr Production and purification of serotype 1, 2, and 5 recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors. Methods. 2002;28:158–167. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]