Abstract

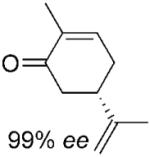

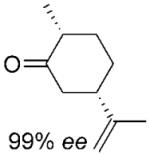

We show that pentaerythritol tetranitrate reductase (PETNR), a member of the ‘ene’ reductase old yellow enzyme family, catalyses the asymmetric reduction of a variety of industrially relevant activated α,β-unsaturated alkenes including enones, enals, maleimides and nitroalkenes. We have rationalised the broad substrate specificity and stereochemical outcome of these reductions by reference to molecular models of enzyme-substrate complexes based on the crystal complex of the PETNR with 2-cyclohexenone 4a. The optical purity of products is variable (49–99% ee), depending on the substrate type and nature of substituents. Generally, high enantioselectivity was observed for reaction products with stereogenic centres at Cβ (>99% ee). However, for the substrates existing in two isomeric forms (e.g., citral 11a or nitroalkenes 18–19a), an enantiodivergent course of the reduction of E/Z-forms may lead to lower enantiopurities of the products. We also demonstrate that the poor optical purity obtained for products with stereogenic centres at Cα is due to non-enzymatic racemisation. In reactions with ketoisophorone 3a we show that product racemisation is prevented through reaction optimisation, specifically by shortening reaction time and through control of solution pH. We suggest this as a general strategy for improved recovery of optically pure products with other biocatalytic conversions where there is potential for product racemisation.

Keywords: asymmetric synthesis, biocatalysis, ene reductase, old yellow enzyme, pentaerythritol tetranitrate reductase, stereochemistry

Introduction

In recent years there has been an intensive search for enzymatic methods in organic synthesis given the increasing demand for optically pure compounds. The biocatalytic asymmetric reduction of activated C=C bonds has received much attention because it can generate up to two new stereogenic centres in a single step.[1-10] Unlike transition metal-catalyzed cis-hydrogenation, biocatalytic reduction of activated α,β-unsaturated alkenes catalyzed by flavin-dependent ‘ene’ reductases from the old yellow enzyme (OYE) family at the expense of NAD(P)H is known to proceed as a net trans-addition of 2 H.[11] These flavoenzymes, obtained primarily from plants and microorganisms,[1-10] have proved to be useful biocatalysts as they reduce a wide spectrum of α,β-unsaturated ketones, aldehydes, nitroalkenes, carboxylic acids and their derivatives, yielding products with a variety of biotechnological and pharmaceutical applications. However, the stereoselectivity and optical purity of the respective products varies widely between these enzymes and is dependent on the nature of the cofactor or cofactor-regeneration system used.[2]

Pentaerythritol tetranitrate reductase (PETNR) from the anaerobic microorganism Enterobacter cloacae st. PB2[12] is related to the prototypical OYE from Saccharomyces pastorianus.[13] PETNR was isolated via its ability to degrade a variety of high explosives, including reduction of nitroaromatics to Meisenheimer hydride complexes and hydrolytic cleavage of nitrate esters.[14,15] More recently we reported that PETNR catalyses the enantioselective reduction of a variety of (E)- and (Z)-α,β-unsaturated nitroalkenes under biphasic reaction conditions.[16] As the enzyme exhibited some unusual behaviour in comparison to other OYEs, including by-product formation,[16] we explored the ability of PETNR to act as a general ‘ene’ reductase. In this paper, we describe the stereoselective reduction of α,β-unsaturated alkenes including enals, enones, enamides and nitroolefins using PETNR. We propose a rationale for the substrate specificity and stereoselectivity of PETNR, based on kinetic and stereochemical data in conjunction with modelling approaches. We also demonstrate that the optimisation of reaction conditions (e.g., enzyme concentration, pH and reaction time) can improve substantially the enantiopurity of the products. We show that this optimisation is required to minimise ‘off-enzyme’ racemisation, which may account for the low enantiopurity of some products of biocatalytic reactions reported in the literature.

Results and Discussion

Substrate Specificity of PETNR for α,β-Unsaturated Alkenes

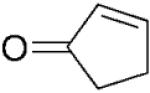

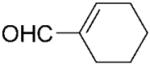

PETNR is known to reduce the C=C double bonds of nitroolefins,[16] prednisone[13] and 2-cyclohexenone (4a),[14] but the substrate range has not been explored further. Therefore, we benchmarked the biocatalytic ability of PETNR against other enzymes from the OYE family[1-6,9] by studying anaerobic bioreduction of a variety of α,β-unsaturated activated olefins. Initially, we determined the kinetic constants (apparent Km, kcat, Ki) of PETNR of anaerobic reduction of the substrates under steady-state turnover conditions (Table 1, Supporting Information Figure S1a-i) prior to analysing reaction products and the stereochemical outcome of the reaction.

Table 1.

Steady state kinetics of PETNR with α,β-unsaturated activated alkenes.[a]

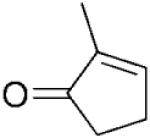

| Entry | Substrate | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | Ki (mM) | kcat/Km (s−1 mM−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

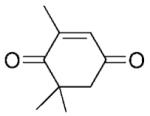

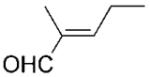

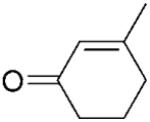

| 1 | 1a |

|

7.65±0.13 | 3.1±0.2 | - | 2468 |

| 2 | 2a |

|

8.00±0.35 | 112.1±10.3 | 3.20±0.70 | 71 |

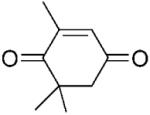

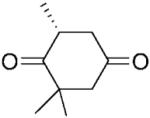

| 3 | 3a |

|

5.52±0.10 | 13.7±0.5 | - | 404 |

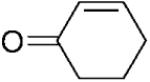

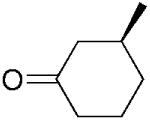

| 4 | 4a |

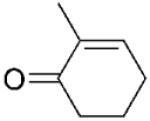

|

6.12±0.17 | 1239±81 | 23.3±1.7 | 5 |

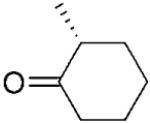

| 5 | 5a |

|

nd | nd | nd | 4[b] |

| 6 | 6a |

|

nd | nd | nd | 2[b] |

| 7 | 7a |

|

nd | nd | nd | 1[b] |

| 8 | 8a |

|

nd | nd | nd | <0.5[b] |

| 9 | 9a |

|

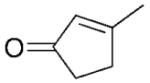

4.10±0.10 | 50.4±3.0 | 3.13±0.63 | 81 |

| 10 | 10a |

|

6.23±0.33 | 102.3±10.5 | 1.93±0.46 | 61 |

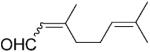

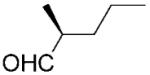

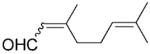

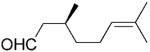

| 11 | 11a |

|

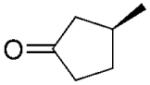

0.240±0.004 | 26.7±1.3 | - | 9 |

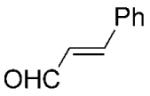

| 12 | 12a |

|

0.83±0.02 | 27.9±1.5 | 2.50±0.54 | 30 |

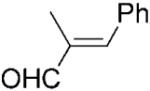

| 13 | 13a[c],[d] |

|

4.70±0.4 | 589±103 | - | 8 |

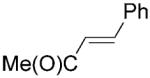

| 14 | 14a [d] |

|

nd | nd | nd | <0.5[b] |

Reactions (0.3 mL) were performed in potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, KH2PO4/K2HPO4, pH 7.0) containing NADPH (100 μM), oxidising substrate (2.5 μM to 50 mM) PETNR (12–2000 μM) and 5% ethanol to solubilise the substrates. The reactions were followed continuously by monitoring NADPH oxidation at 340 nm for 2 min at 25 °C under oxygen free atmosphere (<5 ppm).

kcat/Km was determined from the slope of the progress curve as is standard when Km values are high compared to substrate concentration.

Reactions with oxidizing substrates measured at 365 nm to avoid substrate spectral overlap.

Calculated from a partial curve due to substrate absorbance at 365 nm, > 1.2 mM substrate; nd = not determined due to the poor solubility of the substrate and/or weak activity with PETNR.

Although the biocatalytic reductions of alkenes by OYEs are routinely conducted under aerobic conditions,[1-10] molecular oxygen can compete with the alkene substrates for the oxidation of enzyme-bound FMNH2.[17] This reduces the overall reaction rate, and also yields undesirable reactive products (hydrogen peroxide and superoxide).[17] We confirmed that oxygen affects the reaction rate of PETNR by measuring the reaction rates both aerobically and anaerobically (<5 ppm oxygen). Compared to anaerobic assays, aerobic reduction of 2-cyclohexenone 4a and 2-methylpentenal 10a by PETNR showed a significant reduction in the overall steady-state reaction rate (18% and 48%, respectively), showing the importance of excluding oxygen from the reactions. We therefore ran all reactions under anaerobic conditions.

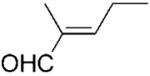

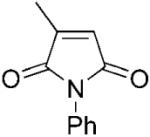

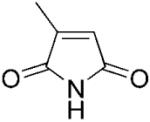

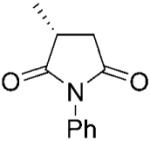

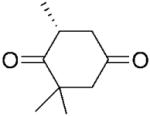

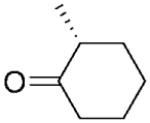

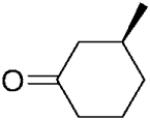

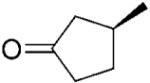

Steady-state parameters (Table 1) indicated a high specificity (kcat/Km) of PETNR for maleimides 1–2a and ketoisophorone 3a. The biological functions and physiological substrates of PETNR and many other OYEs remain unknown, despite the various hypotheses that have been made.[17,18] It is worth noting that the Km for 1a was within the range typical for natural substrates of enzymes. Interestingly, substrates 1–3a possess two activating groups (carbonyl groups) and they were also readily reduced by members of OYE family.[1] By contrast, other cyclohexanone derivatives 4–7a, which possess only one carbonyl group, had kcat/Km two orders of magnitude lower, despite being structurally similar to ketoisophorone 3a (Table 1, entries 4–8 vs. entry 3). In general, ketones 4–8a and 13a were relatively poor substrates under steady-state conditions (Table 1), whereas aldehydes 9–13a were reduced readily by PETNR.

PETNR did not reduce the following α,β-unsaturated carboxylic acid derivatives: trans-cinnamide, trans-cinnamic acid, 3-phenylmaleic acid, 1-cyclohexene-1-carboxylic acids (and their respective esters), methyl trans-cinnamate, and methyl cyclohexenecarboxylate. We also found no activity towards substrates containing activating groups such as nitrile or halogens (crotonitrile, 3-bromocyclohexene, trans-cinnamonitrile, cyclohexene-1-carbonitrile and β-bromostyrene) either in spectrophotometric assays or measured by GC analysis.

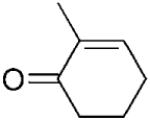

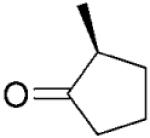

We noted that PETNR has a restricted substrate specificity, which possibly results from the difficulty in accommodating the large substituents at Cα and Cβ in the active site. The selectivity for the alkene activating group is also restricted. The kinetic data (Table 1) demonstrate a general preference for small cyclic molecules (1–9a). For the aldehyde series, smaller substitutents at Cβ were preferred (10a vs. 11–13a), while the presence of a methyl substituent at Cα increased the activity in comparison to the unsubstituted parent molecule. For cinnamaldehyde derivatives (E)-12a and (E)-13a, the introduction of an α-methyl group led to a decrease in kcat, but this was compensated for by the 21-fold decrease in Km, resulting in an overall 3-fold improvement in specificity (kcat/Km). Similar trends were previously observed for nitroalkenes.[16] In contrast, the activity with 2-methylcyclohexenone 5a was lower than with the respective parent ketone (4a; Table 1). The presence of a methyl substituent at Cβ (3-methylcyclohexanone 15a and 3-methylcyclopentanone 16a) leads to a significant reduction in enzyme activity (data not shown). The enzyme was inactive for more sterically hindered substrates such as 3-phenylcyclohexene-1-one.

Similar trends have also been seen with other OYEs,[2-4] which is consistent with the structural similarity of the enzymes within the family. However, recent studies show that directed evolution can be used to extend the substrate specificity of OYEs towards more sterically hindered substrates.[5,19]

We noted that substrate inhibition occurred with many substrates, with Ki values in the low mM range (Table 1; Supporting Information Figure S1a-i). This is a common feature of catalysis by PETNR with both reducing and oxidising substrates.[12] However, this problem can be solved by using a continuous feed of substrate, to maintain the substrate concentration at a non-inhibitory level whilst still ensuring the desired productivity. Furthermore, the enzyme concentration can be increased if necessary to compensate for substrate inhibition.

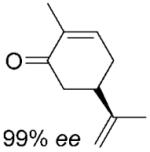

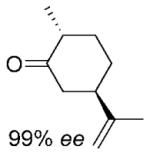

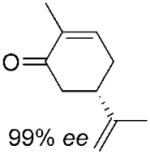

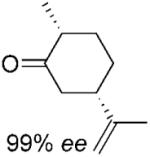

Stereoselectivity of PETNR-Catalyzed Reduction of α,β-Unsaturated Alkenes

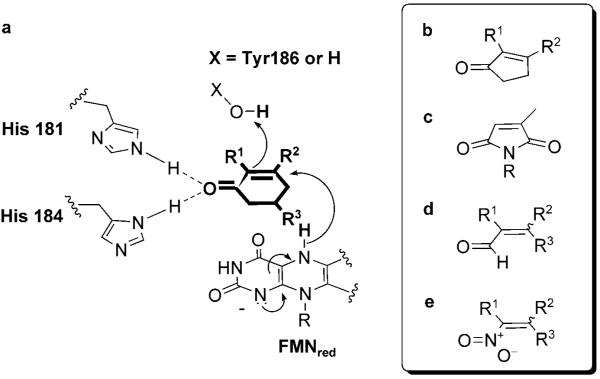

The mechanism of alkene reduction catalyzed by OYEs is known to proceed via hydride transfer (from reduced flavin, FMNH2) to the Cβ atom of the substrate and proton transfer (from a conserved tyrosine residue, Y186 in PETNR, or from water) to the Cα position of the substrate.[11] Hydrogenation of the C=C bond occurs in a trans-fashion, consistent with the crystal structure of PETNR in complex with cyclohexenone 4a (Scheme 1).[14] The binding of the substrates is dictated by two basic amino acid residues, His181 and His184 for PETNR, which interact with the electron-withdrawing group of the substrates and orientate them to allow the hydride transfer to proceed. To obtain stereochemical insight into PETNR-catalyzed reactions, we studied the reduction of compounds with different activating groups and substitution patterns. The assays were performed anaerobically against a variety of substituted α,β-unsaturated substrates (5 mM substrate; 2 μM PETNR) using a glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase/NADPH (G6PDH) cofactor recycling system[20] as the source of reducing equivalents (Table 2).

Scheme 1.

Model of the postulated binding mode and mechanism of alkene reduction by PETNR. Panel a: substrates 3–6a and 15a; panel b: substrates 16–17a; panel c: substrates 1–2a; panel d: substrates 10–11a; panel e: substrates 18–19a.

Table 2.

Reduction of various activated alkenes by PETNR using NADP+/G6PDH co-factor regeneration system.[a]

| Entry | Substrate | Conf. | Product | t [h] | Conv.[b] [%] | Yield[b] [%] | ee[c] [%] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1a |

|

(R)-1b |

|

24 | >99 | 98 | >99 |

| 2 | 2a |

|

(R)-2b |

|

24 | >99 | 99 | >99 |

| 3 | 3a |

|

(R)-3b |

|

24 | >99 | 95 | 49 |

| 4 | 5a |

|

(R)-5b |

|

24 | >99 | 93 | 98 |

| 5 | (5R)-6a |

|

(2R,5R)-6b |

|

24 | >99 | 82 | 95%[d,e] |

| 6 | (5S)-7a |

|

(2R, 5S)-7b |

|

24 | >99 | 95 | 88%[d,e] |

| 7 | 10a |

|

(S)-10b |

|

24 | >99 | 85 | 66 |

| 8 | 11a |

|

(S)-11b |

|

24 | >99 | 56 | 87 |

| 9 | 15a |

|

(S)-15b |

|

24 | 25 | 18 | >99 |

| 10 | 16a |

|

(S)-16b |

|

24 | 14 | 14 | >99 |

| 11 | 17a |

|

(S)-17b |

|

24 | 58 | 56 | 70 |

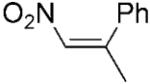

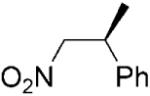

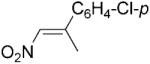

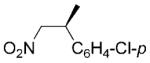

| 12 | (E)-18a |

|

(S)-18b |

|

24 | 96 | 70 | 69 |

| 13 | (Z)-18a |

|

(S)-18b |

|

24 | >99 | 87 | 95 |

| 14 | (E)-19a |

|

(S)-19b |

|

24 | 64 | 40 | 64 |

Conditions: Reactions contained potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4 pH 7.0, 1.0 mL), alkene (5 mM), PETN reductase (2 μM), glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (10 U), glucose 6-phosphate (15 mM) and NADP+ (10 μM). Reactions were agitated at 30 °C at 130 rpm for 24 h. Alkenes 1a, 3a and 18-19a were added as a DMF solution [2% (v/v) final DMF concentration].

by GC using DB-Wax column.

By GC or HPLC.

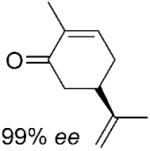

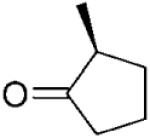

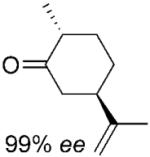

The stereochemical outcome of the bioreductions can be interpreted by reference to the mechanism of reduction of cyclohexenone 4a (Scheme 1).[14] Thus, 3-methylcyclohexenone 15a was reduced to its respective (3S)-enantiomer of 15b, while all 2-methylcyclohexanone derivatives 3–7a were reduced to their respective (2R)-enantiomers (Table 2, entries 3–6). The presence of the bulky substituent remote to the reaction site did not affect the stereochemical outcome of the reaction and the reduction of carvones (5R)–6a and (5S)–7a gave the diastereoisomeric products with the same absolute configuration on carbon C2 (2R) in 95% and 88% de, respectively. The enantioselectivity obtained in the reactions with 2-methyl-substituted cyclohexenones 3a and 5–7a varied from 49 to 98% ee, whereas 3-methylcyclohexanone 15b was obtained in optically pure form. Similarly, 3-methylcyclopentenone 16a yielded the (3S)-enantiomer of 16b in high optical purity (>99% ee), while the reduction of 2-methylcylopentenone 17a furnished the product 17b in moderate ee (70%). Interestingly, the (S)-enantiomeric product, rather than the expected (R)-enantiomer of 17b was formed. This unexpected change of enantioselectivity for formation of 2-methylcyclopentanone 17b has also been reported for other OYEs, although no explanation for this observation was given.[2-4] In light of recent work by Stewart et al.[5] it is possible that substrate 17a may bind in a ‘flipped’ orientation, while maintaining an optimal Cβ-FMN N5 distance and angle (105°),[21] similar to that seen for OYE1 mutant W116I.[5]

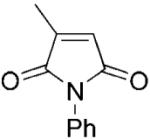

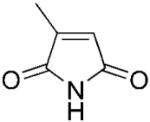

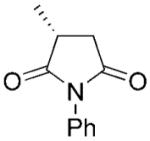

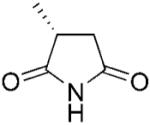

PETNR proved to be highly efficient and highly stereoselective in the reduction of 2-methylmaleimide derivatives 1a–b giving the respective (2R)-products in quantitative yields and high enantioselectivities (>99% ee, Table 2 and Scheme 1c). Similar results were also seen with other OYEs,[2,3] although OYE2 resulted only in the product (R)-2b at 75% ee.[3]

Aldehydes 10–11a were reduced effectively by PETNR, although only with low or moderate ee (Table 2, entries 7 and 8). It should be noted that for the aldehydes tested in this study (9–11a) the yields obtained were not quantitative (50–60%) despite high observed substrate depletion rates (>95%). We were unable to identify the side product(s) formed from these substrates. The corresponding enol products could not be detected suggesting the side reactions did not involve carbonyl bond reduction, so non-enzymatic substrate and/or product decomposition is likely.

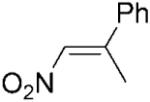

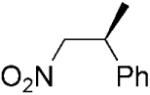

The low enantiopurity of the aldehydes, as well as nitroalkenes with a stereogenic centre at Cα can be attributed to the racemisation of the products in aqueous media.[4,22] The interpretation of the stereochemical outcome of the reduction of citral 11a [the citral 11a used in this study was a mixture of geranial (E)-11a and neral (Z)-11a in approximately 65:35 ratio (by GC)] and nitroalkenes 18a and 19a is more complex, because these substrates isomerise between their E/Z forms under the reaction conditions.[23,24]

We previously published data for the reduction of a library of nitroalkenes by PETNR under biphasic reaction conditions (isooctane/phosphate buffer).[16] To obtain a like-for-like comparison with other substrates reported in this paper, we have also repeated the reductions of 2-aryl-1-nitropropenes 18–19a, using DMF (2%) to solubilise the substrates in a single phase aqueous system (Table 2, entries 12–14). Similarly to our previous study,[16] under monophasic reaction conditions, the (Z)-isomer of 18a gave the respective (S)-product quantitatively in high optical purity (95% ee, compared to 96% in the biphasic system). The reduction of (E)-isomers of nitroalkenes 18a and 19a, furnished the same (S)-enantiomer of the products in moderate enantioselectivity (69 and 64% ee, compared with 89 and 72% in the biphasic system). Moreover, for (E)-nitroolefins 18–19a the yields were not quantitative and the formation of by-products was observed, as described previously.[16] The respective 1-aryl-2-nitropropanes were obtained under the reaction conditions in almost racemic form (data not shown), compared with up to 54% ee reported for the biphasic reductions.[16]

As the configuration of the newly formed stereogenic centre at Cβ depends on highly stereoselective hydride transfer from the flavin (Scheme 1d-e), the moderate ees obtained for 11b and 18–19b are likely to be the result of an enantiodivergent course for the reduction of (E) and (Z)-isomers of the substrates.[23] The kinetic data for nitroalkenes showed a clear preference for the (Z)-isomers of β,β-disubstituted nitroalkenes 18a and 19a compared with their respective (E)-counterparts.[16] Since the reduction of both (E) and (Z)-isomers of nitroalkene 18a lead to the formation of (S)-enantiomer (Table 2, entries 12 and 13), one cannot exclude an enzyme-driven shift in equilibrium between the (E) and (Z)-isomers towards the isomer that binds more strongly to the active site, leading to an apparent enantioconvergent course of the reduction of both isomers. The kinetic data obtained for nitroolefins[16] and modelling of both isomers of citral 11a [(E)-geranial and (Z)-neral] into the active site of PETNR (Supporting Information, Figure S2a-b) suggests that the enzyme prefers a small substituent at Cβ in the position trans to the aldehyde/nitro group (Me vs. Ph for nitroalkenes and Me vs. alkyl for citral).

Enantioselectivity in Relation to Reaction Conditions

The bioreduction catalysed by PETNR gave products with variable degrees of optical purity (49–>99% ee; Table 2), which was also observed with other OYEs.[2-4] As previous studies have shown that the nature of the cofactor or cofactor regeneration system affects the enantiopurity and even the absolute configuration of the product,[2-4] we studied the effect of using NADP+/G6PDH as cofactor recycling system vs. reactions with excess NADPH (Table 3). Both reaction conditions proved to be equally efficient (inferred from similar yields and conversion) and the products had similar optical purities after 24 h. When we extended the reaction time for the NADP+/G6PDH system (48–72 h), we observed high optical purity of the reduction products possessing a stereogenic centre at Cβ (>99% ee for 15–16b). This is in contrast to all the 2-methyl-substituted cyclohexenones 3b and 5–7b and 2-methylcyclopenenone 17b, which lost enantiopurity over time. A similar time-dependent loss of enantiopurity for these compounds was seen with other OYEs, although it was not investigated in detail.[2,3] Since the enzymatic reaction with these substrates was complete after 24 h, we concluded that the loss of optical purity was due to racemisation of products with a stereogenic centre at Cα. The apparent rate of racemisation varied depending on the nature of the product. For example, while levodione 3b racemised quickly, other cyclohexanone derivatives 5–7b racemised at a slower rate. Maleimide 1a gave virtually optically pure products, which were stable on prolonged incubation (Table 3, entry 2), as it is not prone to racemisation.

Table 3.

Reduction of activated alkenes by PETNR over 24–72 h hours with NADPH and an NADP+/G6PDH co-factor regeneration system, respectively.[a]

| Entry | Conf. | Product | Cofactor | 24 h Conv.[b] [%] |

Yield[b] [%] | ee[c] [%] | 48 h ee[c] [%] |

72 h ee[c] [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

NADPH | >99 | >99 | 93 | - | - | |

| 2 | (R)-1b | NADP+/G6PDH | >99 | >99 | 99 | >99 | >99 | |

| 3 |

|

NADPH | >99 | >99 | 21 | - | - | |

| 4 | (R)-3b | NADP+/G6PDH | >99 | >99 | 57 | 26 | 13 | |

| 5 |

|

NADPH | >99 | >99 | 94 | - | - | |

| 6 | (R)-5b | NADP+/G6PDH | >99 | >99 | 96 | 94 | 91 | |

| 7 |

|

NADPH | >99 | 88 | 93% de[b] | - | - | |

| 8 | (2R,5R)-6b | NADP+/G6PDH | >99 | 81 | 94% de[b] | 92% de[b] | 89% de[b] | |

| 9 |

|

NADPH | >99 | 97 | 81% deb | — | — | |

| 10 | (2R,5S)-7b | NADP+/G6PDH | >99 | 91 | 87% de[b] | 80% de[b] | 75% de[b] | |

| 11 |

|

NADPH | 54 | 53 | >99 | - | - | |

| 12 | (S)-15b | NADP+/G6PDH | 53 | 53 | >99 | >99 | >99 | |

| 13 | (S)-16b |

|

NADPH | 44 | 41 | >99 | - | - |

| 14 | NADP+/G6PDH | 41 | 40 | >99 | >99 | >99 | ||

| 15 |

|

NADPH | >99 | >99 | 65 | - | - | |

| 16 | (S)-17b | NADP+/G6PDH | >99 | >99 | 71 | 65 | 58 |

Conditions for assays with NADPH: alkene (5 mM), PETN reductase (2 μM), NADPH (15 mM) in phosphate buffer (50 mM, 1 mL total volume), 30 °C at 130 rpm, 24 h; Conditions for assays with NADP+/G6PDH: alkene (5 mM), PETN reductase (2 μM), glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (10 U), glucose 6-phosphate (15 mM) and NADP+ (10 μM) in phosphate buffer (50 mM, 1 mL total volume), 30 °C at 130 rpm, 24 h. Alkenes 1a and 3a were added as a DMF solution (2% final DMF solution).

By GC using a DB-Wax column.

By GC or HPLC. Conv. = % conversion.

Therefore, we investigated the conditions influencing the enantiopurity of the product of PETNR-catalysed reductions. As a model compound we chose ketoisophorone 7a to levodione (R)-7b, which is an important synthon in the synthesis of zeaxanthin.[25] Initially, we investigated the effect of pH and enzyme concentration on the optical purity of product (R)-3b (Table 4 and Table 5).

Table 4.

pH dependence for the reduction of ketoisophorone 3a with 0.02 μM PETNR.[a]

| Entry | pH | Conv. (1.5 h)[b] [%] |

Yield (1.5 h)[b] [%] |

ee (1.5 h)[c] [%] |

ee (24 h)[c] [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.0 | 2 | 1 | >99 | 93 |

| 2 | 5.5 | 5 | 3 | >99 | 93 |

| 3 | 6.0 | 13 | 12 | >99 | 91 |

| 4 | 6.5 | 24 | 22 | >99 | 87 |

| 5 | 7.0 | 27 | 26 | 99 | 79 |

| 6 | 7.5 | 28 | 27 | 98 | 62 |

| 7 | 8.0 | 33 | 31 | 97 | 41 |

| 8 | 8.5 | 32 | 31 | 95 | 13 |

| 9 | 9.0 | 31 | 30 | 92 | 0 |

Conditions: The reactions contained Bis-Tris/HEPPS/CHES buffer (75 mM/38 mM/38 mM, respectively, 1 mL total volume), alkene 3a (5 mM), PETNR (0.02 μM), and NADPH (6 mM). Reactions were agitated at 30 °C at 130 rpm for 1.5 and 24 h. Alkene 3a was added as a DMF solution (2% final DMF concentration).

By GC using a DB-Wax column.

By GC using Chirasil-DEX-CB column.

Table 5.

Enzyme concentration dependence for the reduction of ketoisophorone 3a after 2 h.[a]

| Entry | Enzyme concentra- tion |

Conv.[b] [%] |

Yield[b] [%] |

ee[c] [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 μM | >99 | 95 | 93 |

| 2 | 0.2 μM | >99 | 95 | 96 |

| 3 | 0.02 μM | 37 | 33 | 95 |

| 4 | 0.002 μM | 2 | 2 | >99 |

Conditions: alkene 3a (5 mM), PETN reductase, NADPH (6 mM) in phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0, 1 mL total volume), 30 °C at 130 rpm, 2 h. Alkene 3a was added as a DMF solution (2% final DMF solution).

By GC using a DB-Wax column.

By GC using Chirasil-DEX-CB.

PETNR had a broad pH optimum at basic pH values (pH 7.0–9.0), with only low conversion observed below pH 6.0 (Table 4). The enzyme possesses up to two histidine residues, which are involved in substrate binding (Scheme 1).[13,14] Since the imidazole ring of histidine is mostly protonated below pH 6.0 (pKa of imidazole ring 5.97), this may explain the poor activity at lower pH. As expected, reductions catalysed at acidic or neutral pH (5.0–7.0) yielded the product (R)-3b with high enantiopurity, with lower optical purity obtained at pH 7.5–9.0. The pH effect was more pronounced if reactions were carried out for 24 h, reflecting a time-dependent loss of enantiopurity (Table 4). Therefore, we conducted further assays at pH 7.0 to minimise racemisation whilst obtaining reasonable reaction rates.

Reactions carried out at higher enzyme concentrations yielded a slightly lower optical purity of the product, suggesting an apparent enzymatic effect (Table 5). However, the racemisation process could be attributed potentially to: (i) enzyme-catalysed racemisation within the active site;[23,26] (ii) enzyme-catalysed racemisation specific to basic amino acid groups located on the enzyme surface (which may involve either PETNR or G6PDH or both); (iii) influence of glucose 6-phosphate or the 6-phosphogluconate formed during cofactor regeneration, which may decrease the pH, if buffer capacity is exceeded; (iv) non-enzymatic racemisation. To determine whether the observed racemisation was purely non-enzymatic or enzyme-driven, we determined the rate of racemisation of product at pH 7.0 over 24 h (Table 6 and Figure S3 in Supporting Information). Control reactions were performed where after 8 h of incubation either the PETNR reductive activity was inhibited by the addition of 1,4,5,6-tetrahydroNADPH (NADPH4; an excellent inhibitor of PETNR activity[27]), or total protein was removed from the reactions by filtration and the reactions were incubated for further 16 h. This enabled us to distinguish between the potential mechanisms of racemisation (Table 6, entries 10–12).

Table 6.

The effect of time on the reduction of ketoisophorone 3a and product racemisation catalysed by PETNR (0.02 μM).[a]

| Entry | Time [h] | Conv.[b] [%] | Yield[b] [%] | ee[c] [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.5 | 14 | 12 | >99 |

| 2 | 1 | 27 | 23 | 99 |

| 3 | 1.5 | 37 | 35 | 98 |

| 4 | 3 | 53 | 53 | 93 |

| 5 | 4 | 69 | 65 | 90 |

| 6 | 6 | 85 | 80 | 82 |

| 7 | 8 | 94 | 87 | 76 |

| 8 | 12 | 98 | 88 | 69 |

| 9 | 22 | >99 | 91 | 33 |

| 10 | 24 | >99 | 95 | 30 |

| 11 | 24[d] | 99 | nd | 30 |

| 12 | 24[e] | 99 | nd | 29 |

Conditions: alkene 3a (5 mM), PETNR (0.02 μM), NADPH (6 mM) in phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0, 1 mL total volume), 30 °C at 130 rpm, 2 h. Alkene 3a was added as a DMF solution (2% final DMF solution).

By GC using a DB-Wax column.

By GC using a Chirasil-DEX-CB column.

Filtered using 10 K millipore filter after 8 h to remove all enzyme content.

PETNR inhibitor NADPH4 (1.2 mg) added after 8 h to inhibit enzymatic activity.

The data showed a decline in enantiopurity of (R)-3b with time at a rate of approximately 3% ee/h (Table 6). The enantiomeric excess of 3b obtained after 24 h (30% ee) was virtually the same as those obtained in the control experiments (entry 10 vs. 11 and 12), what clearly demonstrates that the racemisation is primarily a non-enzymatic, chemical process. This suggests that the effect of enzyme concentration on product enantiopurity (Table 5) might be due to the balance between the rates of reduction and racemisation processes. At high enzyme concentration, the reaction is completed rapidly, and the product (R)-3b is left in the aqueous reaction mixture, allowing it to racemise (Table 5, entry 1). At low enzyme concentrations (entry 4), the substrate is reduced much more slowly, and the freshly formed (R)-enantiomer was still accumulating when the reaction was terminated after 2 h. Thus, the continued synthesis of (R)-3b would compensate for the racemisation only to a small extent. Therefore we concluded that minimising the reaction time was crucial to obtain high enantiopurity of the product. Indeed, when we studied the time effect on the optical purity of levodione 3b at higher enzyme concentration (2 μM, Supporting Information, Table S1 and Figure S4), we observed the same rate of racemisation (3% ee/h) and the high ees (≥95%) were obtained only for the assays conducted for less then 1 h.

These studies showed that a combination of (i) optimising the solution pH and (ii) reducing the time the product spends in aqueous solution (by shortening the reaction time or using biphasic reaction systems, as shown before[16]) is critical to improving the enantiopurity of products subject to racemisation. We achieved complete conversion and obtained optically pure levodione 3b (97% ee) using 2 μM enzyme concentration at pH 7.0 when conducting the reduction for only 30 min. This contrasts with the relatively poor ees obtained from longer reaction times (Table 1 and Table 3). Optimisation in this way may be beneficial to other biocatalytic processes catalysed by different enzymes where product racemisation is an issue. For reactions yielding products where racemisation is negligible, optimisation studies should be more focused on optimising enzyme activity and/or increasing substrate/product solubility and media engineering.

Models of Substrate-Bound PETNR and NMR Studies on the Stereochemistry

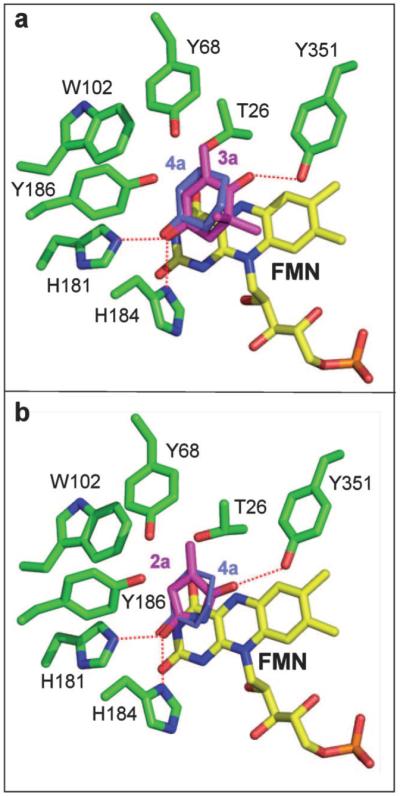

Kinetic data for the compounds possessing two activating groups 1–3a suggest that they are especially good substrates for PETNR-mediated reduction (Table 1). To gain a greater understanding of the stereochemical outcome of the reactions, we modelled the potential binding modes of maleimide 2a and ketoisophorone 3a in the active site of PETNR (Figure 1 a and b). We maintained a similar relative position and orientation of the C=C and C=O bonds (in red) as in the structure of PETNR containing bound 2-cyclohexenone 4a as well as a near optimal Cβ-FMN N5 distance and orientation.[14,16]

Figure 1.

Models of the active site of PETNR containing (a) ketoisophorone 3a and (b) 2-methylmaleimide 2a overlaid with the known position of 2-cyclohexenone 4a. The position of 4a is derived from a superimposition of the 2CH-PETNR structure onto the model (pdb code 1GVQ).[14] All residues are shown as atom-coloured sticks with green, yellow, magenta and blue carbons for amino acids, FMN, substrate 3a or 2a and 4a, respectively. Predicted hydrogen bonds are indicated by red dotted lines. The figures were generated in Pymol.[29]

Both models predict that the substrates bind to the active site of PETNR on the si-face of the isoalloxazine ring of the FMN, with the carbonyl group O2 within hydrogen bonding distance of both H181 NE2 and H184 ND1 as seen in the 2-cyclohexenone and progesterone-bound structures.[13,14] In the case of the model for maleimide 2a binding (Figure 1b), the second carbonyl oxygen O5 is within hydrogen bonding distance of the OG1 atom of Y351. This residue (Y375 in OYE1) is known to be involved in binding the inhibitor, p-hydroxybenzaldehyde, via a hydrogen bond between atom OG1 and the inhibitor carbonyl atom O1′.[17,28] This suggests a possible role of Y351 in the binding and correct orientation of some substrates within the active site. A minor clash between the C12 atom (methyl group at Cβ) and T26 OG1 was also present in this model. A second model where the substrate was rotated 180°, swapping the positions of Cα and Cβ, is predicted to be less favoured due to a significant clash between the substrate C12 atom and W102 (results not shown).

The model of ketoisophorone 3a (Figure 1a) shows a closer match in both the position and orientation to the known position of cyclohexene 4a,[14] resulting in a change in orientation of the substrate with respect to the model of 4a. This results in the absence of an interaction between the second carbonyl group (O7) and Y351 OH. A model of 2a in the same relative orientation as in 4a would be less favoured as there would be severe clashes between the 2′- and 6′-methyl groups with residues W102 and Q241. In this position the OH atom of the putative proton donor Y186 is about 3.2 Å from both the Cα and Cβ atoms of the substrate.

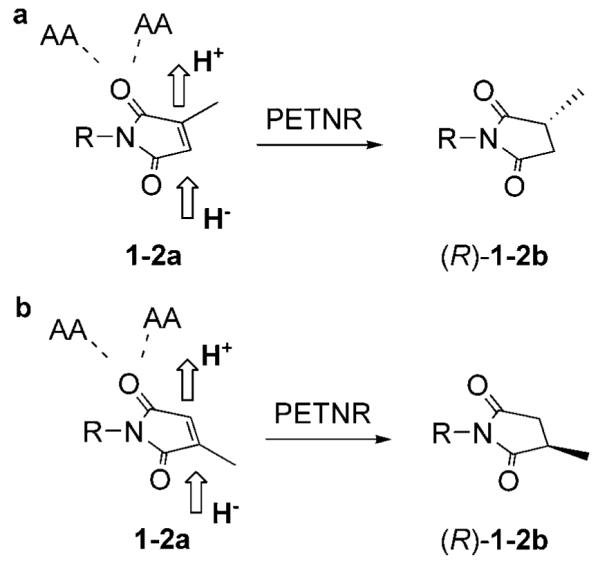

Interestingly, both the binding modes of the substrates 1–3a should result in the same stereochemical outcome for reduction, leading to the formation of the (R)-enantiomer, as depicted in Scheme 2 for maleimides 1–2a. This makes it more difficult to predict which of the different possible binding mode/s of these substrates are catalytically competent and which catalytic step determines the stereochemistry: protonation or hydride addition.

Scheme 2.

Stereochemical course of the reduction of maleimides 1–2a by PETNR (R=Ph or H). Two possible binding modes of 1–2a give the same stereochemical outcome: a) hydrogen at new stereogenic centre (C2) is derived from protonation step; b) from hydride addition step.

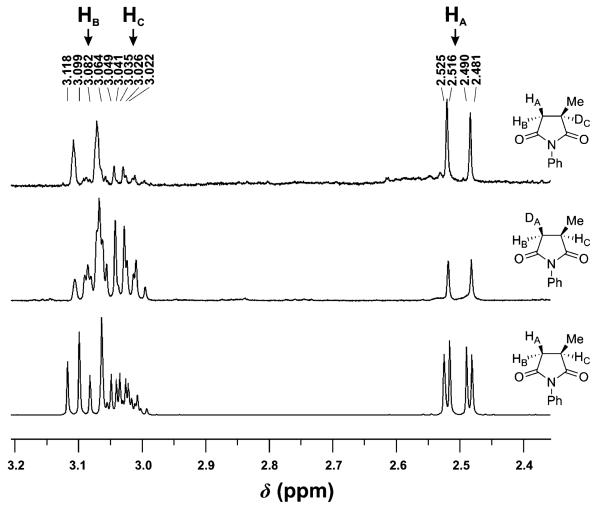

To investigate further the binding modes of the substrates in PETNR, we envisaged using NMR to determine whether the hydrogen at the newly formed stereogenic centre of the products came from either the FMN by hydride transfer or from a water-mediated protonation step. Unfortunately, the reduction of the substrate 3a by PETNR in deuterated phosphate buffer (pD 7.0), with NADPH as a cofactor lead to a complete exchange of all the ring protons to deuterium. This clearly established significant proton exchange for levodione 3b, which is easily enolisable. Fortunately, the racemisation of succinimides is negligible so we performed two parallel bioreductions of maleimide 1a with PETNR using either NADPH in deuterated phosphate buffer pD 7.0, or pro-R NADPD in phosphate buffer pH 7. In both experiments deuterium was found at C2 and C3 positions, but the level of incorporation biased either toward HA or HC (Figure 2). The retention of geminal coupling constant JAB (about 18 Hz) and the complete loss of the vicinal coupling constant JAC (about 4 Hz) present in the spectrum of a parent, non-deuterated compound (Figure 2, bottom spectrum), suggests that the total yield deuterium incorporation between these 2 positions was 100%, however, unequally distributed. The NMR analysis of the product 1b obtained in deuterated buffer showed approximately 65% incorporation of deuterium at the C3 position (DA) and approximately 35% at the position C2 (DC, by NMR integration, Figure 2 middle spectrum). In contrast, the reaction where NADPD served as reducing cofactor led primarily to deuterium incorporation at the C2 position (70% of DC), whereas 30% was incorporated at C3 (Figure 2 top spectrum).

Figure 2.

1H NMR (400 MHz) analysis of N-phenyl-2-methylsuccinamide (1b): a) reduction in the presence of (R)-[4-2H]-NADPH (NADPD) in phosphate buffer; b) reduction in the presence of NADPH in deuterated phosphate buffer; c) a parent non-deuterated compound.

These results suggest that, while both of the postulated binding modes are possible, the orientation depicted in Scheme 2b is favoured and the proton at the newly formed stereogenic centre C2 is derived mostly from the hydride transfer step. This agrees with our modelling studies with substrate 2a, which predicts that hydride transfer occurs predominately on the C2 atom (Figure 1b).

Conclusions

We have shown that PETNR has excellent potential as a biocatalyst due to its ability to catalyse the asymmetric bioreduction of a variety of industrially relevant α,β-unsaturated activated alkenes in a stereoselective manner. It is an efficient catalyst for the reduction of a variety of enones, enals, maleimides and nitroalkenes. It terms of stereoselectivity it is similar to other OYEs such as OPR3 from tomato[4] and NCR-reductase from Zymomonas mobilis.[3] This provides further evidence for the catalytic promiscuity of PETNR, which was originally isolated by its ability to reduce nitroaromatic explosives via the formation of the Meisenheimer-hydride complex.[15,30]

Enzymes obtained from natural sources rarely possess the combined properties necessary for industrial applications such as high activity with non-natural substrates, and more-importantly high stereoselectivity.[31] Our study demonstrates that optimisation of the reaction conditions such as pH, reaction time and enzyme concentration appears to be critical in significantly increasing the enantiopurity of products which are subject to racemisation under the reaction conditions. We were able to dramatically improve the enantiopurity of the product (R)-levodione 3b from 49% to 97% ee by simply increasing the enzyme concentration and reducing the reaction time. Such optimisation studies could be broadly applied to biotransformations of other substrates by OYEs, and to other reaction types where product racemisation is a problem.

Our work emphasises the importance of using a hybrid approach, combining studies of both substrate specificity/enantioselectivity with analysis of models for the target enzyme-substrate complex whilst identifying and screening industrially useful biocatalysts. Our approach has allowed us to rationalise the substrate specificity of PETNR and to predict the importance of Y351 in substrate binding of double-activated molecules such as 1–3a. Modelling approaches should reduce the burden of performing extensive substrate screens to identify compounds that are accommodated in the enzyme active site as well as introducing new functional groups into target substrates. Structural modelling approaches also suggest strategies to generate new improved biocatalysts by directed mutagenesis. Structure-based identification and design of biocatalysts complements other powerful laboratory evolution approaches for the creation of new biocatalysts that are not necessarily dependent on structural knowledge of the enzyme.[5,19,32]

Experimental Section

General Enzymatic Procedures

Glucose 6-phosphate and glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) from Leuconostoc mesenteroides, KH2PO4, K2HPO4, CHES {2-(N-cyclohexylamino)ethanesulfonic acid], Bis-Tris {1,3-bis[tris(hydroxymethyl)methylamino]-propane} and HEPPS [N-(2-hydroxyethy1)piperazine-N’-propanesulfonic acid] were obtained from Sigma Aldrich. NADP+ and NADPH were obtained from Melford. (R)-[4-2H]-NADPH (NADPD; >95% deuterium incorporation by 1H NMR) and the inhibitor 1,4,5,6-tetrahydroNADPH (NADPH4) were kindly supplied by Dr. Christopher R. Pudney. PETNR was prepared as described previously.[13] Prior to use, PETNR was deoxygenated by passage through a BioRad 10DG column equilibrated in anaerobic reaction buffer to avoid unproductive flavin reoxidation during oxidising substrate reduction. All the solutions were made anaerobic and the reactions were set-up in the oxygen free environment (<5 ppm of O2).

Steady-State Kinetic Analysis

All kinetics measurements were performed within an anaerobic glove box (Belle Technology Ltd) under a nitrogen atmosphere (<5 ppm oxygen). The following extinction coefficients were used to calculate the concentration of NADPH and enzyme: NADPH (ε340=6220 M−1 cm−1; ε365=3256 M−1 cm−1) and PETNR (ε464=11.3×103 M−1 cm−1). The following extinction coefficients were used to calculate the concentration of the alkene substrates 1a (ε221=21200 M−1 cm−1); 2a (ε221=19100 M−1 cm−1); 3a (ε246=21100 M−1 cm−1); 4a (ε231=11000 M−1 cm−1); 5a (ε242=10450 M−1 cm−1); (5R)–6a and (5S)–7a (ε242=7600 M−1 cm−1); 8a (ε223=14100 M−1 cm−1); 9a (ε237=13800 M−1 cm−1); 10a (ε234=14600 M−1 cm−1); 11a (ε244=15100 M−1 cm−1); 12a (ε288=24800 M−1 cm−1); 13a (ε292=24100 M−1 cm−1); and 14a (ε292=23200 M−1 cm−1); 15a (ε241=14700 M−1 cm−1); 16a (ε231=16200 M−1 cm−1); 17a (ε232=10900 M−1 cm−1).

Steady-state kinetic measurements were performed anaerobically using a BioTek Synergy HT microtiter plate reader with a 0.84 cm path length. Reactions (0.3 mL) were performed in buffer (50 mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4 pH 7.0) containing NADPH (100 μM), oxidising substrate (2.5 μM to 50 mM) PETNR (12–2000 μM) and 5% ethanol to solubilise the substrates. The reactions were followed continuously by monitoring NADPH oxidation at 340 nm for 2 min at 25°C. Reactions with oxidising substrates that absorbed at 340 nm were monitored at 365 nm. To determine the kinetic parameters with each substrate (apparent Km, kcat and Ki), the reactions were performed with variable oxidising substrate concentrations. For substrates that were reduced by PETNR at very low rates, only the kcat/Km parameter could be determined using substrate concentrations (10–40 μM) well below the estimated Km. Initial velocity data as a function of oxidising substrate were analysed by fitting to either the standard Michaelis-Menten rate equation, or to an equation that incorporates substrate inhibition [Eq. (1)].

| (1) |

Aerobic reactions were performed as above, except all solutions were prepared, and all data collected outside the glove box. For all microtiter plate kinetic assays, a minimum of 6 replicates was generated per data point to ensure data accuracy and reproducibility.

General Procedures for the Reduction of Alkenes by PETNR

General procedure 1

Standard reactions (1.0 mL) were performed in buffer (50 mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4 pH 7.0) containing alkene (5 mM), NADPH (15 mM) and PETNR (2 μM). The reactions were shaken at 30 °C at 130 rpm followed by reaction termination by extraction with ethyl acetate (0.9 mL) containing an internal standard (limonene, 5% v/v), and dried using MgSO4. The extracts were analysed by GC or HPLC to determine the yield, % conversion, and enantiomeric excess. Products were identified by comparison with authentic reference material. Maleimide 1a ketoisophorone 3a, and nitroalkenes 18-–19a were added as a concentrated solution in 2% DMF.

General Procedure 2

Reactions employing a NADPH recycling system (1.0 mL) were performed in buffer (50 mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4 pH 7.0) containing alkene (5 mM; dissolved as above), glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (10 U), glucose 6-phosphate (15 mM), NADP+ (10 μM) and PETNR (2 μM). The reactions were shaken at 30 °C at 130 rpm followed by extraction with ethyl acetate (0.9 mL) containing an internal standard (limonene, 5% v/v) and analysed as described above.

General Procedure 3

To determine the effect of pH, all reactions (1.0 mL) were performed in a broad pH range buffer mixture (75 mM Bis-Tris, 38 mM HEPPS, 38 mM CHES, pH 5.0–9.0) containing alkene (5 mM), NADPH (6 mM) and PETNR (20 nM to 2 μM). The reactions were agitated at 30 °C at 130 rpm followed by extraction with ethyl acetate (0.9 mL) containing an internal standard and analysed as described above.

General Procedure 4

This procedure is to determine if the physical presence of the enzyme influences the rate of racemisation of products (i.e., if basic amino acid residues influence the racemisation rate independent of reductive activity). After 8 h of biotransformations with ketoisophorone 3a: a) the enzyme was removed from the reaction via centrifugation (5000 rpm for 5 min) in a 10 kDa milipore filter spin column; b) PETNR inhibitor NADPH4 was added. The reactions were further incubated and analysed after 24 h (total time) as described above.

Chemistry

NMR spectra were recorded on 400 MHz or 500 MHz spectrometers and referenced to the solvent, unless stated otherwise. The chemical shifts are reported in ppm and coupling constants (J) are given in hertz (Hz). Melting points were determined using an electrothermal capillary apparatus and are uncorrected. IR spectra were recorded neat on NaCl plates. HPLC analysis was performed using an instrument equipped with a UV detector. UV-visible data were recorded with a diode array spectrophotometer. The progress of the reactions was monitored by GC or TLC on standard silica gel plates. All chemicals obtained from commercial sources and the solvents were of analytical grade. Citraconic anhydride, substrates 3–12a, trans-cinnamide, trans-cinnamic acid, methyl trans-cinnamate, trans-cinnamonitrile, 3-phenylmaleic acid, 1-cyclohexene-1-carboxylic acid, methyl 1-cyclohexene-1-carboxylate, crotonitrile, 3-bromocyclohexene, 2-cinnamonitrile, cyclohexene-1-carbonitrile, β-bromostyrene, racemic products 3–12a, (R)-(+)-3-methylcyclopentanone [(R)-7b], (R)-(+)-3-methylcyclohexanone [(R)-6b], (S)-citronellal [(S)-11b] were from commercial suppliers (Aldrich, Avocado). (+)-Dihydrocarvone was obtained from a commercial supplier as a mixture of 2 isomers (2R,5R)–6b and (2R,5S)–6b in 77:20 ratio (>99% ee). Nitroalkenes (E)-18a, (Z)-18a and (E)-19a were synthesised as described previously.[16,24] Racemic nitroalkanes 18–19b were obtained in 80–85% yields by silica gel-assisted reduction of their respective nitroalkenes by NaBH4 according to as described in the literature.[33] Model optically active nitroalkanes (R)-18b and (R)-19b were synthesised as described before.[24] 3-Phenyl-2-cyclohexene-1-one was synthesised as described previously.[34]

The rest of the compounds were synthesised as follows:

N-Phenyl-2-methylmaleimide (1a) was synthesised from citraconic anhydride and aniline as pale yellow needles, according to the procedure described previously;[35] yield: 60%; mp 98–100 °C (lit. mp 96–98 °C);[35] 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ=2.15 (d, J=1.8 Hz, 3 H), 6.46 (q, J=1.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.16–7.31 (m, 5 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ=11.2., 126.0, 127.5, 129.12, 131.7, 145.8, 169.6, 170.7; anal. calcd. for C5H5NO2: C 54.05, H 4.54, N 12.61; found: C 54.31, H 4.57, N 12.48. All spectral data were in accordance with those reported in the literature.[35]

(R)-N-Phenyl-2-methylsuccinimide (1b) was synthesised enzymatically at 50 mL scale according to general procedure 2 (36 h) as a white solid; yield: 98%; mp 133–134 °C (lit. mp 132–134 °C);[36] 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ=1.45 (d, J=7.2 Hz, 3 H), 2.50 (dd, J=4.3 Hz, J=17.6 Hz, 1 H), 2.98–3.13 (m, 2 H), 7.26–7.50 (m, 5 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ=16.9, 34.8, 36.6, 126.4, 128.6, 129.1, 131.9, 175.4, 179.5; [α]D: + 9.90 (c 1.01, CHCl3) lit. + 6.6 (c 0.56, CHCl3);[37] >99% ee (Chiralcel OD: hexane/i-PrOH, 9:1, tR=53.5 min, ts=63.0 min); anal. calcd. for C11H11NO2: C 69.83, H 5.86, N 7.40; found: C 69.95, H 5.90, N, 7.28. A respective racemic compound 1b was synthesised as described before[2] as white crystals; yield: 62%; mp 106–107 °C (lit. mp 107 °C, ethanol).[38] All spectral data were in accordance with those reported in the literature.[2]

2-Methylmaleimide (2a) was synthesised according to the procedure described previously; yield: 5%;[2,39] mp 104–106 °C (lit. mp 105 °C);[2] 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ=2.11 (d, J=1.6 Hz, 3 H), 6.34 (q, J=1.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.4 (bs, 1 H); anal. calcd. for C5H5NO2: C 54.05, H 4.54, N 12.61; found: C 54.31, H 4.57, N 12.48. All spectral data were in accordance with those reported in the literature.[35]

(R)-2-Methylsuccinimide (2b) was synthesised enzymatically at 50 mL scale according to general procedure 2 (36 h) as a white solid; yield: 95%; mp 66 °C (lit. mp 62 °C);[40] 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ=1.33 (d, J=7.2 Hz, 3 H), 2.33–2.39 (m, 1 H), 2.90–2.98 (m, 2 H), 8.9 (bs, 1 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ=16.4, 36.1, 37.5, 177.2, 181.4; >99% ee (by Chiral GC using Chiraldex B-TA);[2] [α]D: + 24.8 (c 1.60, CHCl3) lit. [α]D: + 29.4 (c 2.0, CHCl3);[40] anal. calcd. for C5H7NO2: C 53.09, H 6.24, N 12.38; found: C 53.47, H 6.47, N 11.83. A respective racemic compound 2b was synthesised from maleimide 2a as a white powder; yield: 98%; mp 68–70 °C (lit. mp 66–68.5 °C).[41] All spectral data were in accordance with those reported in the literature.[2]

(R)-Levodione (3b) was synthesised from ketoisophorone according to general procedure 2 (36 h) as a white solid; yield: 90%; mp 68–70 °C [lit. mp 65–67 °C for racemate, 91–92 °C for (R)-enantiomer];[25] 27% ee (by Chiral GC on Chirasil-DEX-CB column);[2] 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ=1.12 (s, 3 H), 1.14 (d, J=6.6 Hz, 3 H), 1.16 (s, 3 H), 2.34 (dd, J=12.8 Hz, J=17.8 Hz, 1 H), 2.52 (dd, J=0.7 Hz, J=15.4 Hz, 1 H), 2.72–2.78 (m, 2 H), 2.96–3.05 (m, 1 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ=14.6, 25.6, 26.5, 39.8, 44.2, 44.8, 52.7, 208.0, 214.1; [α]D: −64.6 (c 0.61, MeOH) lit. −270 (c 0.4, MeOH);[25] anal. calcd. for C9H14O2: C 70.10, H 9.15; found: C 70.31, H 9.43. All spectral data were in accordance with those reported in the literature.[42]

2-Methyl-2-cylohexene-1-one (5a) was synthesised from cyclohexenone 4a in a 3-step synthetic strategy, as described before.[43,44] 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ=1.66–1.78 (m, 3 H), 1.95–2.02 (m, 2 H), 2.29–2.33 (m, 2 H), 2.40–2.44 (m, 2 H), 6.72–6.76 (m, 1 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ=16.0, 23.3, 26.0, 38.3, 135.7, 145.6, 200.0.

(2R,5R)- Dihydrocarvone (6b) was synthesised enzymatically at 50 mL scale according to general procedure 2 (1.5 days) as a transparent oil; yield: 90%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ=1.04 (d, J=6.5 Hz, 3 H), 1.36 (dq, J=3.5 Hz, J=13.1 Hz, 1 H), 1.57–1.70 (m, 1 H), 1.71–1.73 (m. 3 H),1.90–1.96 (m, 1 H), 2.08–2.14 (m, 1 H), 2.23–2.45 (m, 4 H), 4.70–4.75 (m, 2 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ=14.3, 20.5, 30.7, 34.9, 44.7, 46.8, 47.0, 109.6, 147.6, 212.7; >99% ee by GC, 96% de by 1H NMR All spectral data were in accordance with those reported in the literature for (2S,5S)–6b.[45]

3-Methylcyclohexanone (15b) was synthesised from the respective 3-methyl-2-cylohexene-1-one 15a as described for 17b as a transparent oil; yield: 77%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ=1.02 (dd, J=1.8 Hz, J=6.3 Hz, 3 H), 1.28–1.38 (m, 1 H), 1.60–1.80 (m, 2 H), 1.81–2.52 (m, 4 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ=22.1, 25.3, 33.3, 34.2, 41.1, 50.0, 212.1. All spectral data were in accordance with those reported in the literature.[46,47]

2-Methylcyclopentanone (17b) was synthesised from the respective 2-methyl-2-cylopetene-1-one 17a. Hydrogen was purged through the solution of alkene (2 mmol) and Pd/C (10%, 10 mg) in ethyl acetate or methanol (12 mL) until the reaction was completed as detected by TLC. The reaction mixture was filtered through a Celite plug and the solution was evaporated under vacuum. Solid products were purified by chromatography (hexane:ethyl acetate). Liquid products were vacuum-distilled (bulb-to-bulb). Yield: 20% : 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ=1.02 (d, J=7.0 Hz, 3 H), 1.43–1.53 (m, 1 H), 1.73–1.83 (m, 1 H), 1.92–2.05 (m, 1 H), 2.07–2.17 (m, 2 H), 2.20–2.36 (m, 2 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ=14.2, 20.6, 31.9, 37.6, 44.0, 221.0. All spectral data were in accordance with those reported in the literature.[46,48]

Analytical Procedures

Determination of yield and % conversion

GC analysis of conversion and yields was performed on a 30 m DB-Wax (0.32 mm, 0.25 mm) column, unless stated otherwise. Yield and % conversion of the reduction of 2-methylmaleimide 2b were determined using a Chiraldex B-TA column (40 m, 0.25 mm).

Determination of enantiomeric excess and absolute configuration

The absolute configuration of N-phenyl-2-methylsuccinimide 1b was determined by a comparison of its optical rotation with literature data[37] while the enantiomeric excess was determined by HPLC using a Chiralcel OD column [hexane/i-PrOH, 9:1, retention times: (R)- and (S)-maleimide 20.0 min and 22.0 min, respectively] or a Chiralcel OJ column [hexane/i-PrOH, 9:1, (R)- and (S)-maleimide 53.4 min and 60.8 min, respectively]. The absolute configuration of 2-methylsuccinimide 2b was determined by comparing the optical rotation value with literature data[40] and its enantiomeric excess was determined using a Chiraldex B-TA column (40 m, 0.25 mm), as described previously.[2] The absolute configuration of levodione 3b was assigned by a comparison of its optical rotation with literature data[25] and the ee was determined using a CP-Chirasil-DEX-CB column (25 m, 0.32 mm, 0.25 μm film), as described previously.[2] Enantiomeric excesses of ketones 5b and 15–17b were determined using a Chiraldex B-TA column (40 m, 0.25 mm), as described before,[2] and the absolute configurations were assigned by a comparison with authentic samples of (R)-5b and (R)-17b obtained commercially. The absolute configurations of ketones 15b and 16b were assigned by comparison of the elution order on a Chiraldex B-TA column with the literature data.[2] The absolute configurations of (2R,5R)-dihydrocarvone (2R,5R)–6b obtained from (5R)-carvone (5R)–6a and (2R,5S)-dihydrocarvone (2R,5S)–7b obtained from (S)-carvone (5S)–7a were assigned by NMR[45] and compared with an authentic sample of (2RS,5R)-dihydrocarvone 6b obtained commercially as a mixture of trans:cis isomers 77:20 [by NMR and GC on DB-wax column: split 20, flow 1 mLmin−1, injector: 220 °C, detector: 250 °C, temperature programme: 40 °C hold for 2 min, to 210 °C at 15°Cmin−1, hold for 3 min; retention times: (2R,5R)–6b and (2S,5R)–6b 11.31 and 11.46 min, respectively]. Enantiomeric excesses of dihydrocarvones 6–7b were determined using a Chiraldex B-TA column (40 m, 0.25 mm column): split 100, injector 180 °C, detector 200 °C, flow 1 mLmin−1, 80°C, hold 2 min, to 110 °C at 10°Cmin−1, hold 20 min, to 120 °C at 10 °Cmin−1, hold 10 min, to 180 °C at 10°C hold 1 min. Retention times: (2R,5R)–6b 30.59 min, (2S,5R)–6b 31.71 min, (2R,5S)–7b 32.88 min, (2S,5S)–7b 33.95 min. The enantiomeric excess of 2-methylpentanal 10b was determined using a Hydrodex-β-TBDAc column (25 m, 0.25 mm): split 100, flow 1 mLmin−1, injector: 180 °C, detector: 250 °C, temperature programme: 80 °C hold for 10 min, to 120 °C at 4°Cmin−1, hold for 2 min, to 180 °C at 10°Cmin−1, hold for 2 min; retention times: (R)- and (S)-2-methylpentanal 10.86 and 11.36 min, respectively. The absolute configuration of (S)-10b was assigned after reduction of aldehyde to primary alcohol with NaBH4 and comparison of the chromatographic data on a chiral column (Hydrodex-β-TBDM, 25 m, 0.25 mm) as published previously.[2,4] The enantiomeric excess of citronellal 11b was determined using a Hydrodex-β-TBDAc column (25 m, 0.25 mm)[2] and the absolute configuration was assigned by comparison of the chromatogram with an authentic sample of (S)-11b obtained commercially (Aldrich). The absolute configurations of nitroalkanes 18–19b were determined by a comparison with literature data and authentic samples obtained by us previously.[16,24] The enantiomeric excess of nitroalkane 18b was determined using a CP-Chirasil-DEX-CB column (25 m, 0.32 mm, 0.25 μm film) as described previously.[2] The enantiomeric excess of nitroalkane 19b was determined using a Chiralcel OD column, respectively, as described previously.[16,24] The absolute configurations of nitroalkanes 18–19b were assigned by comparison with previously published data.[16,24]

Molecular Modelling

The substrates 2a and 3a were modelled into the active site of PETNR using the methods of Sketcher[49] and Coot,[50] based on the position of the substrate in the 2-cyclohexenone-bound structure (pdb code 1 gvq).[14] The models were refined using the structural idealisation functions of the programme REFMAC[51] to normalise the bond angles and distances of the substrates and minimise clashes.

Supplementary Material

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/adsc.200900574.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council. NSS is a BBSRC Professorial Research Fellow and GS is a BBSRC Research Development Fellow.

References

- [1].Chaparro-Riggers JF, Rogers TA, Vazquez-Figueroa E, Polizzi KM, Bommarius AS. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2007;349:1521–1531. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hall M, Stueckler C, Ehammer H, Pointner E, Oberdorfer G, Gruber K, Hauer B, Stuermer R, Kroutil W, Macheroux P, Faber K. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008;350:411–418. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hall M, Stueckler C, Hauer B, Stuermer R, Friedrich T, Breuer M, Kroutil W, Faber K. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008:1511–1516. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hall M, Stueckler C, Kroutil W, Macheroux P, Faber K. Angew. Chem. 2007;119:4008–4011. doi: 10.1002/anie.200605168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:3934–3937. doi: 10.1002/anie.200605168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Padhi SK, Bougioukou DJ, Stewart JD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:3271–3280. doi: 10.1021/ja8081389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Stueckler C, Hall M, Ehammer H, Pointner E, Kroutil W, Macheroux P, Faber K. Org. Lett. 2007;9:5409–5411. doi: 10.1021/ol7019185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Swiderska MA, Stewart JD. Org. Lett. 2006;8:6131–6133. doi: 10.1021/ol062612f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Swiderska MA, Stewart JD. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 2006;42:52–54. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bougioukou DJ, Stewart JD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:7655–7658. doi: 10.1021/ja800200r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kosjek B, Fleitz FJ, Dormer PG, Kuethe JT, Devine PN. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2008;19:1403–1406. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Stuermer R, Hauer B, Hall M, Faber K. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2007;11:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].French CE, Nicklin S, Bruce NC. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:6623–6627. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.22.6623-6627.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Barna TM, Khan H, Bruce NC, Barsukov I, Scrutton NS, Moody PC. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;310:433–447. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Khan H, Harris RJ, Barna T, Craig DH, Bruce NC, Munro AW, Moody PC, Scrutton NS. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:21906–21912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200637200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].a) Williams RE, Rathbone DA, Scrutton NS, Bruce NC. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:3566–3574. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.6.3566-3574.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ye J, Singh A, Ward OP. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004;20:117–135. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Toogood HS, Fryszkowska A, Hare V, Fisher K, Roujeinikova A, Leys D, Gardiner JM, Stephens GM, Scrutton NS. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008;350:2789–2803. doi: 10.1002/adsc.200800561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Williams RE, Bruce NC. Microbiology. 2002;148:1607–1614. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-6-1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Amari F, Fettouche A, Samra MA, Kefalas P, Kampranis SC, Makris AM. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008;56:11740–11751. doi: 10.1021/jf802829r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kille S, Bougioukou DJ, Reetz MT. Biotrans. Berne; Switzerland: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Meah Y, Massey V. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:10733–10738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190345597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Fraaije MW, Mattevi A. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:126–132. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ohta H, Kobayashi N, Ozaki K. J. Org. Chem. 1989;54:1802–1804. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Muller A, Hauer B, Rosche B. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2007;98:22–29. doi: 10.1002/bit.21415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Fryszkowska A, Fisher K, Gardiner JM, Stephens GM. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:4295–4298. doi: 10.1021/jo800124v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Leuenberger HGW, Boguth W, Widmer E, Zell R. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1976;59:1832–1849. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Case DA, Cheatham I, E T, Darden T, Gohlke H, Luo R, Merz J, M K, Onufriev A, Simmerling C, Wang B, Woods R. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1668–1688. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Pudney CR, Hay S, Scrutton NS. FEBS J. 2009;276:4780–4789. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Fox KM, Karplus PA. Structure. 1994;2:1089–1105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].DeLano WL. DeLano Scientific; Palo Alto, CA, USA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Khan H, Barna T, Harris RJ, Bruce NC, Barsukov I, Munro AW, Moody PC, Scrutton NS. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:30563–30572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403541200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Stephan Luetz LGJL. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2008;101:647–653. doi: 10.1002/bit.22077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Mugford PF, Wagner UG, Jiang Y, Faber K, Kazlauskas RJ. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:8912–8923. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:8782–8793. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Sinhababu AK, Borchardt RT. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:227–230. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zhang Z, Zha Z, Gan C, Pan C, Zhou Y, Wang Z, Zhou M-M. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:4339–4342. doi: 10.1021/jo060372b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Choi D-S, Huang S, Huang M, Barnard TS, Adams RD, Seminario JM, Tour JM. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:2646–2655. doi: 10.1021/jo9722055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Balenovi K, Bregant N. J. Chem. Soc. 1965:5131–5132. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hirata T, Takarada A, Matsushima A, Kondo Y, Hamada H. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2004;15:15–16. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kling J. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1897;30:3041. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Shah KR, Blanton CD. J. Org. Chem. 1982;47:502–508. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Polonski T. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1. 1988:629–637. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Earl RA, Clough FW, Townsend LB. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1978;15:1479–1483. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Sefton MA, Skouroumounis GK, Massywestropp RA, Williams PJ. Austr. J. Chem. 1989;42:2071–2084. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Baraldi PG, Barco A, Benetti S, Pollini GP, Zanirato V. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:4291–4294. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Confalone PN, Baggiolini E, Hennessy B, Pizzolato G, Uskokovic MR. J. Org. Chem. 1981;46:4923–4927. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Maestro MA, Castedo L, Mourino A. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:5208–5213. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Stothers JB, Tan CT. Can. J. Chem. 1974;52:308–314. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Tsuda T, Hayashi T, Satomi H, Kawamoto T, Saegusa T. J. Org. Chem. 1986;51:537–540. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Jedlinski Z, Misiolek A, Glowkowski W, Janeczek H, Wolinska A. Tetrahedron. 1990;46:3547–3558. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Collaborative Computational Project number 4 Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Emsley P, Cowtan K. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/adsc.200900574.