Abstract

The glmS ribozyme is the first naturally occurring catalytic RNA that relies on an exogenous, non-nucleotide cofactor for reactivity. From a biochemical perspective, the glmS ribozyme derived from Bacillus anthracis is the best characterized. However, much of the structural work to date has been done on a variant glmS ribozyme, derived from Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis. Here we present structures of the B. anthracis glmS ribozyme in states before the activating sugar, glucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcN6P), has bound and after the reaction has occurred. These structures show an active site pre-organized to bind GlcN6P that retains some affinity for the sugar even after cleavage of the RNA backbone. A structure of an inactive glmS ribozyme with a mutation distal from the ligand-binding pocket highlights a nucleotide critical to the reaction that does not affect GlcN6P binding. Structures of the glmS ribozyme bound to a naturally occurring inhibitor, glucose-6-phosphate (Glc6P), and a non-natural activating sugar, mannosamine-6-phosphate (MaN6P), reveal a binding mode similar to that of GlcN6P. Kinetic analyses show a pH dependence of ligand binding that is consistent with titration of the cofactor’s phosphate group and support a model in which the major determinant of activity is the sugar amine independent of its stereochemical presentation.

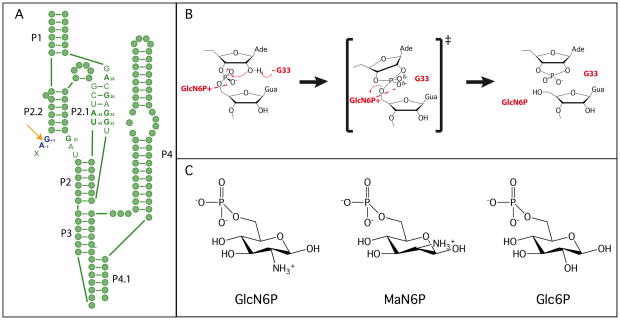

The glmS ribozyme catalyzes a reaction that is chemically identical to that of other nucleolytic ribozymes, but uses a novel catalytic strategy [Figure 1A] (1). In the nucleolytic cleavage reaction the 2′-OH of a ribose acts as the nucleophile, attacking the scissile phosphate and releasing the 5′-oxygen leaving group [Figure 1B]. This reaction requires an in-line (180°) conformation for the 2′-OH, scissile phosphate and 5′-oxygen. The reaction is often accelerated through activation of the nucleophile, stabilization of the transition state or protonation of the leaving group (1). Many nucleolytic ribozymes use nucleobases and metal ions to fulfill these roles (2). In the glmS ribozyme, a guanosine has been implicated in the reaction mechanism [Figure 1B] (3, 4). However, the glmS ribozyme is the first identified example of a nucleolytic RNA that also relies on a small molecule cofactor, glucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcN6P), to promote chemistry [Figure 1C] (5). The glmS ribozyme is found upstream of the gene for glucosamine-6-phosphate synthase, the enzyme responsible for GlcN6P production (5). This RNA is also a riboswitch, regulating the cellular production of GlcN6P.

Figure 1.

Structure and mechanism of the glmS ribozyme. A. Secondary structure of the pre-cleaved glmS ribozyme. Green filled circles represent individual nucleotide and key active site nucleotides are indicated. The cleavage site is shown using an orange arrow, and the nucleotides flanking the scissile phosphate are shown in dark blue. Paired regions are numbered according to convention. B. The proposed catalytic mechanism of the glmS ribozyme. C. The three sugars used in the mechanistic and structural studies.

Riboswitches are a recently identified class of RNAs that function as regulators of gene expression (6). In most cases, the riboswitch is located in the 5′-untranslated region of a gene that is involved in regulating the concentration of the small molecule that the riboswitch binds (7). Upon ligand binding, a conformational change occurs that is propagated along the mRNA leading to decreased (or increased) gene production using a variety of mechanisms, including the formation of a transcriptional terminator or seclusion of the Shine-Dalgarno sequence (7). However, even the earliest reports of the glmS ribozyme suggested that as a riboswitch it was using a different mechanism (5). First, addition of GlcN6P induced a specific cleavage event in the 5′-UTR of the glmS gene, which seemed to be correlated with gene expression levels. Second, there did not appear to be any structural rearrangements in the RNA upon addition of GlcN6P (5, 8).

Initial crystallographic studies of the glmS ribozyme added evidence to support a different mode of action for this riboswitch (3, 9). The structure of a pre-cleaved version of the glmS ribozyme from Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis was very similar to the structure of the ribozyme bound to the competitive inhibitor, glucose-6-phosphate (Glc6P) (9). Glc6P is structurally identical to GlcN6P, but has a hydroxyl at C2 instead of a primary amine [Figure 1C]. Furthermore, all pre-cleaved, post-cleavage, and effector bound structures solved to date show very similar active sites, supporting the biochemical conclusion that there is little difference between the unbound, bound and reacted forms of the ribozyme (3, 5, 8, 9, 10).

However despite the similar active sites, there are some differences in the peripheral regions of the ribozyme between the T. tengcongensis structures and the effector bound B. anthracis structure (3, 10). These may have arisen because the ribozymes were derived from different sources or because different substitutions were made to inhibit the ribozyme. Because the majority of the biochemical characterization of the glmS ribozyme has been done using the B. anthracis sequence, it is important to examine the structure of this form of the ribozyme throughout the catalytic cycle and with inactivating mutations.

The glmS ribozyme appears to be poised for catalysis, even in the absence of ligand binding, raising the question of how effector selectivity is achieved by the ribozyme (9). Klein et al. demonstrated the importance of a guanosine at the nucleotide 3′ of the scissile phosphate, showing that mutation of that nucleotide led to reduced affinity for GlcN6P over other ligands with primary amines (10). Here we present the crystal structures of a series of glmS ribozymes, providing snapshots of the full catalytic pathway for the B. anthracis variant of the riboswitch as well as highlighting important aspects of GlcN6P binding. Additional biochemical data explore the fine control the ribozyme exerts in recognition of the sugar ligand for catalysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

RNA expression constructs were developed, synthesized and purified as previously described (3). Glucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcN6P) and glucose-6-phosphate (Glc6P) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Mannosamine-6-phosphate (MaN6P) was synthesized enzymatically, using a modified procedure based on that of Liu and Lee (11). Briefly, 2 mmoles (0.43 g) of 2-Amino-2-deoxy-D-mannose hydrochloride were combined with 1.4 mmoles (0.29 g) MgCl2·6H2O and 2.2 mmoles (1.21g) of ATP in 54 mL of deionized water. 1320 units (13 mg) of hexokinase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae were dissolved in 1 mL of deionized water and added to this mixture. The reaction was stirred for 5 hours at room temperature, and the pH was kept constant at 7.5. The product appeared as a UV-negative, ninhydrin-positive spot with a lower Rf value than the starting material when visualized by thin layer chromatography (TLC). When complete, the reaction mixture was lyophilized and then re-suspended in a minimal amount of water (approximately 5 mL) and the pH adjusted to 5. Purification was performed using a Dowex 50 W x 8 column (200–400 mesh, H+ form) washed one time with water, two times with 1 M HCl, and then equilibrated with water until it reached pH 5. The compound was eluted with water and purity was verified by TLC analysis. MaN6P was checked for nuclease contamination prior to use.

Methods

Crystallization

Complexes were prepared for crystallization, with the exception of the MaN6P containing crystals, following the previously published method (3). MaN6P crystals were grown at higher pH, using TAPS (pH 8.5) instead of sodium cacodylate (pH 6.8) and 5 mM-20 mM MaN6P. Crystals were harvested and frozen in 35% PEG-8000, 1.5 M 1,6-hexanediol, 200 mM KCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 20 mM TAPS (pH 8.5). The freezing solution had to be re-adjusted to pH 8.5 after all components were added. All data collection was done at Brookhaven National Laboratory. Data were processed using HKL-2000 and molecular replacement was done using PHASER (12, 13). REFMAC and COOT were used for the rebuilding and refinement of all crystallographic data (14–16). All structural figures were made using PYMOL (17).

Kinetics

Ban-11U RNA (B. anthracis glmS ribozyme construct) (1 μM) was incubated with 5′ end radiolabeled rS (substrate oligonucleotide containing a ribose at the cleavage site) in kinetics buffer (100 mM MgCl2, 25 mM K-acetate, 25 mM K-cacodyate, 25 mM K-HEPES, 25 mM TAPSO, adjusted to the appropriate pH) for ~5 minutes. GlcN6P or MaN6P, pH adjusted, was added to start the reaction. Aliquots were taken at appropriate times, either by hand or using a quench flow apparatus (KinTek Corporation, Austin, TX) and quenched using formamide loading buffer (95% formamide, 2.5 mM EDTA, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 0.1% xylene cyanol) or formamide loading buffer with 100 mM EDTA for the quench flow experiments. Reactant and product rS were separated by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and visualized using a STORM PhosphorImager (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Data were analyzed using ImageQuant (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) and rates were determined using the equation:

| (1) |

and fit using the least squares implementation in KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software, Reading, PA). K1/2 (concentration of sugar required to achieve half maximal rate) and kmax (maximum rate of cleavage) at each pH were determined using the equation:

| (2) |

The apparent pKa’s for 1/K1/2, kmax and kmax/K1/2 were determined using the equations:

| (3) |

Where y is 1/K1/2, kmax, or kmax/K1/2 and ymax is the maximum value for 1/K1/2, kmax or kmax/K1/2 over the entire pH range. In all cases the slope, m, was set to 1 except in the case of kmax for glmS cleavage catalyzed by GlcN6P.

Three independent kinetic trials were run for each sugar concentration at every pH, and Ka’s were determined from the average of the trials, represented in Figure 6. Reported error is the calculated standard error from the three trials and displayed as error bars in Figure 6.

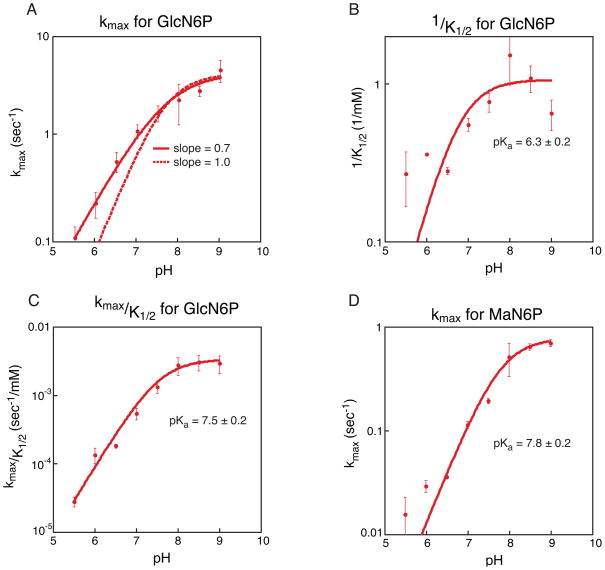

Figure 6.

Kinetic analysis of GlcN6P and MaN6P activation of the glmS ribozyme. A. Plot of pH versus average kmax for GlcN6P activation of the glmS ribozyme. Three independent kinetic trials were run for each concentration at each pH and three independent values of kmax were determined; the average of the three values is depicted. Error bars represent the standard error on the average. In solid red is the best fit to the data, producing a slope of 0.7. The dotted line is the fit to the same data but forcing the slope of the line to be 1. B. Plot of pH versus 1/K1/2 for GlcN6P activation of the glmS ribozyme. Three independent kinetic trials were run for each concentration at each pH and three independent values of 1/K1/2 were determined; the average of the three values is depicted. Error bars represent the standard error on the average. Three independent pKa’s were calculated and the average value is given; reported error is the standard error on the average. C. Plot of pH versus kmax/K1/2 for GlcN6P activation of the glmS ribozyme. As in plot B the values given are averages and errors and error bars represent the standard error of three trials. D. Plot of pH versus kmax for MaN6P activation of the glmS ribozyme. As in plot B the values given are averages and errors and error bars represent the standard error of three trials.

31P NMR titration

NMR samples containing GlcN6P were titrated using KOH and brought to a final concentration of 50 mM cofactor and 50% D2O, in the absence of the ribozyme. A total of 11 samples were used between pH 4.2 and 8.4. A 1D 31P spectrum with composite-pulse proton decoupling was collected on a 500 MHz Bruker Advance NMR spectrometer running TopSpin version 1. The pH was measured before and after the NMR experiment and the two measured values were averaged to give a pH for each sample; however, only the pH of the samples initially at pH 4.2 and 8.4 changed over the course of the experiment. The Ka of the phosphate group was calculated using the equation:

| (4) |

where Δω is the change in 31P chemical shift.

RESULTS

All structures reported here were derived from crystals that grew in conditions similar to the original published condition for the B. anthracis glmS ribozyme (3). The data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in table S1. For a list of all glmS ribozyme structures determined to date, see table S2. All ribozyme crystallization complexes were composed of an RNA transcript, an oligonucleotide with a 2′-O-methyl-adenosine at the cleavage site, and the RNA binding domain of the U1A protein, unless otherwise noted. All crystals were in the P21 space group with four molecules in the asymmetric unit. In most cases, the overall architecture of the active sites of the four molecules was the same. Any differences observed between the four are mentioned explicitly in the discussion of each structure.

Structure of the pre-cleaved glmS

The structure of a glmS ribozyme derived from B. anthracis in the absence of cofactor was solved and refined to 3.1 Å resolution. The overall structure is similar to that of our previously reported structure of the ribozyme bound to the natural ligand, GlcN6P [Figure 2A and 2B] (3). The average RMS deviation between the two structures is less than 1.5 Å. This apo-glmS structure, like a structure of the apo-glmS ribozyme derived from T. tengcongensis, reveals an active site architecture that is poised for catalysis (9). Even in the absence of sugar binding, all atoms involved in bond making and bond breaking are aligned for chemistry. The 2′-OH (methylated in this construct to inhibit the reaction), the scissile phosphate and the 5′-O leaving group are at an angle of approximately 155°, very close to the in-line conformation required for nucleolytic attack [Figure 2A].

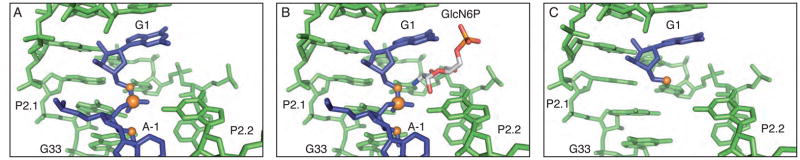

Figure 2.

Active site of the glmS ribozyme through the cleavage reaction. A. The active site structure of the unbound, pre-cleaved state of the glmS ribozyme. The ribozyme is depicted in green, with the nucleotides that flank the scissile phosphate in blue and the reactive atoms shown in orange. This coloring scheme is used throughout the figures. B. The active site structure of the GlcN6P bound state of the glmS ribozyme. The bound sugar molecule is depicted in gray. C. The active site of the reacted state of the glmS ribozyme.

The sugar-binding pocket is structurally similar to that which was observed in the GlcN6P bound state of the ribozyme (3). P2.1 and P2.2, where most of the nucleotides that interact with GlcN6P are located, are superimposable in the presence or absence of sugar [Figure 2A and 2B]. Further, the conserved guanosine (G33) that has been predicted to activate the nucleophile is still within hydrogen bonding distance of the methylated 2′-OH (3, 9).

Structure of the product glmS complex

The crystal structure (2.9 Å resolution) of the product state of the glmS ribozyme was obtained from crystals containing the RNA transcript, U1A, GlcN6P and an all ribose substrate oligonucleotide (rS). The substrate was fully cleaved during the pre-crystallization incubation time and only the product was observed in the crystals [Figure 2C].

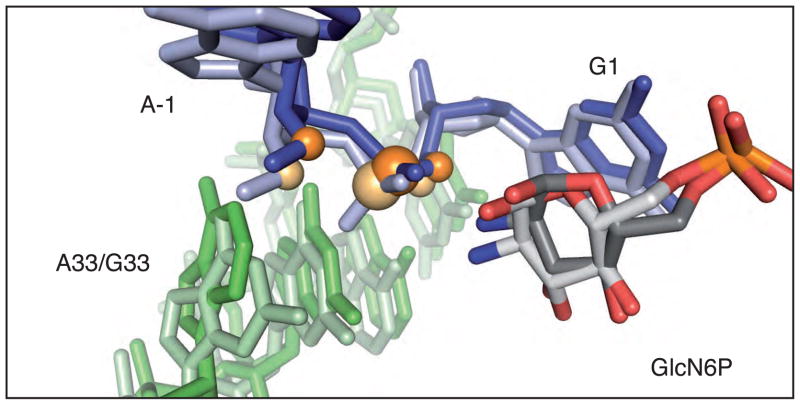

In this structure of the B. anthracis product ribozyme the GlcN6P appears to be bound in at least one of the four active sites present within the asymmetric unit where there is clear density for the phosphate and the entire sugar [Figure 3A]; the cofactor is positioned as it is in the pre-cleaved structure [Figures 3B and 3C]. The C2 primary amine, which has been implicated in the catalytic mechanism, is positioned between the free 5′-OH and the O4 of U43 [Figure 3B] (5, 18). There is also weak density for what appears to be the phosphate atom in the other three active sites but it was modeled as a water molecule due to a lack of density for the sugar ring.

Figure 3.

The active site of the product state of the glmS ribozyme. A. Fo−Fc density in the active site of the cleaved glmS ribozyme contoured at 2σ. B. GlcN6P modeled into the active site of the cleaved glmS ribozyme. C. The active site of the cleaved glmS ribozyme superimposed on the active site of the pre-cleaved glmS ribozyme. The pre-cleaved ribozyme is shown in lighter shades.

Structure of an inactive mutant glmS ribozyme

The initial structures of the glmS ribozyme implicated a conserved guanosine, G33 (G40 in T. tengcongensis), in activation of the nucleophile (3, 9). Mutation of the G to any other nucleotide severely decreases the rate of the reaction (3, 4). The G to A mutant is the most detrimental and reduces the rate of the reaction by about 105. While this nucleotide has been implicated in catalysis, we cannot rule out the possibility that the effect may be due to a gross structural rearrangement in the active site. To address this question, we determined the structure of the mutant ribozyme in which this nucleotide was mutated to an adenosine (G33A).

The overall structure of a pre-cleaved, G33A mutant (3.0 Å) has an average RMSD less than 2 Å from the structure of the wild type ribozyme. Even the position of nucleotide 33 is essentially superimposable between the two structures. There is less than a 1 Å shift between the N1 of A33 and the N1 of G33; this shift moves A33 to a position that is slightly out of hydrogen bonding distance to the methylated 2′-OH nucleophile [Figure 4]. However, it does not disrupt the inline conformation of the nucleophile, scissile phosphate and leaving group or affect GlcN6P binding to the ribozyme as there is clear density for the sugar molecule in every active site.

Figure 4.

The active site of the G33A mutant glmS ribozyme superimposed on the active site of the wild type G33 mutant glmS ribozyme. The mutant is shown in dark shades and wild type ribozyme is shown in light shades.

Structure of the glmS ribozyme bound to a competitive inhibitor

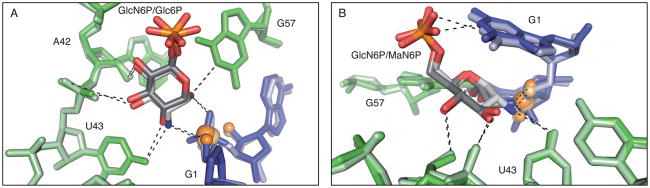

Previous structural and biochemical work has shown that the glmS ribozyme binds to, but is not activated by, a GlcN6P analog, glucose-6-phosphate (Glc6P), in which the primary amine is replaced by a hydroxyl (5, 9, 18). We determined the structure of the precleaved form of the B. anthracis ribozyme bound to the Glc6P inhibitor (2.85 Å). As in the structure of the T. tengcongensis glmS ribozyme, there is strong density for Glc6P in the sugar-binding pocket of the B. anthracis structure (9). Glc6P occupies an almost identical position in the glmS ribozyme active site as GlcN6P, with perhaps a small shift (less than 1 Å) of the sugar away from the scissile phosphate (3). This sugar variant makes a set of contacts with the ribozyme similar to that made by the cognate ligand including a hydrogen bond between the O4 of U43 the C2-hydroxyl of Glc6P [Figure 5A].

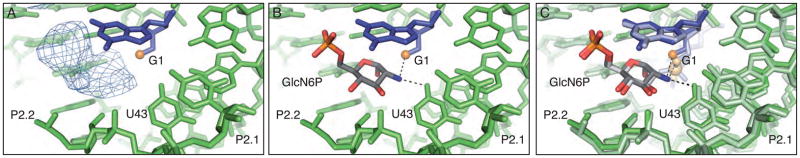

Figure 5.

Alternative sugar binding in the active site of the glmS ribozyme. A. The Glc6P bound active site of the glmS ribozyme superimposed on the GlcN6P bound active site. The Glc6P bound structure is shown in dark shades and the GlcN6P bound structure is shown in light shades. B. The MaN6P bound active site of the glmS ribozyme superimposed on the GlcN6P bound active site. The MaN6P bound structure is shown in dark shades and the GlcN6P bound structure is shown in light shades.

Structure of the glmS ribozyme bound to a non-natural, activating sugar

Breaker and coworkers reported that the glmS ribozyme could also be activated by mannosamine-6-phosphate (MaN6P), a GlcN6P analog in which the stereochemistry at the C2-amine is inverted (19). We have determined the structure of MaN6P bound to the B. anthracis glmS ribozyme at 3.0 Å resolution. Due to limitations of sugar solubility in the freezing conditions, 5 mM MaN6P was used in the study. This concentration is below the measured K1/2 for MaN6P (see below); however, density was observed for this sugar in at least two of the four glmS ribozymes present in the asymmetric unit. While the stereochemistry at C2 is inverted, the overall position of the sugar in the active site is similar to that of GlcN6P [Figure 5B]. In fact, the C2-amine is still within hydrogen bonding distance of the 5′-oxygen leaving group, fulfilling the proposed role of the primary amine in protonation of the leaving group.

Kinetic analysis of GlcN6P activation of the glmS ribozyme

In our initial report of the B. anthracis ribozyme structure, we measured kinetic constants for activation of the ribozyme by GlcN6P (3). We found that the order of addition (i.e. whether the reaction begins by addition of labeled oligonucleotide or by addition of GlcN6P) impacts the rate of the reaction. The kmax plateaus at a slower rate when the reaction is initiated with labeled oligonucleotide than when the reaction is initiated with GlcN6P. We attributed this to slow binding of the oligonucleotide or a conformational change that dominated the rate of the reaction under saturating conditions of GlcN6P. The complex is formed in ~1 minute (data not shown), therefore a pre-incubation time of ~ 5 minutes was used to ensure complete complex formation. We also revisited other aspects of the reaction conditions. First, we observed that under the conditions used, increasing the concentration of the ribozyme 10-fold did not affect the rate of the reaction, suggesting that the ribozyme concentration is saturating for the oligonucleotide substrate. Second, we were concerned about the free magnesium concentration in the reaction, particularly at high concentrations of sugar analogs. Initial reactions were carried out in 10 mM MgCl2, however we noticed that the reaction rate plateaus and then decreases when the concentration of MgCl2 is less than or equal to the concentration of sugar phosphate (data not shown). This was attributed to free GlcN6P coordinating Mg2+ in solution and inhibiting the reaction. To ensure that Mg2+ did not become limiting at any of the reaction conditions 100 mM MgCl2 was used in all kinetics reactions. This change resulted in less than a 2-fold rate change at low concentrations of GlcN6P (data not shown).

We examined the reaction kinetics, initiating the reaction with GlcN6P and measuring the rate under conditions where the proposed conformational change is no longer rate limiting. Both kmax (the maximum rate of cleavage) and K1/2 (concentration of sugar required to achieve half maximal rate) showed a dependence on pH, with tighter binding and a faster rate at high pH [Figure 6A and 6B]. At high pH, kmax plateaus at ~5 sec−1. The data do not fit to a curve with a slope fixed at 1, but fit nicely to a curve with a slope of 0.7 [Figure 6A]. This indicates that the kinetics are more complex than can be described by a simple system with a single pKa. A plot of kmax/K1/2, however, fits very well to the titration of a group with pKa ~7.5 [Figure 6C]. These data suggest that the amine of GlcN6P (pKa ~8) could be playing a key role as either an acid or a base in the ribozyme reaction. The K1/2 data indicate that cofactor binding is relatively weak, with a K1/2 of 1–2 mM from pH 7–9 [Figure S1]. Binding of GlcN6P is even weaker at low pH, with a K1/2 of ~6 mM at pH 5.5 (data not shown). A plot of 1/K1/2 versus pH reveals a pKa of ~6.3. There are no groups within the RNA that have a pKa near 6, but the pKa of the phosphate of GlcN6P is expected to be in this range. The pKa of GlcN6P was determined by collecting the phosphorus NMR spectrum of free GlcN6P at a variety of pHs. This revealed a pKa for unbound GlcN6P of ~6.1 [Figure S2]. The correlation between the pKa of the phosphate of GlcN6P and the pKa of GlcN6P binding to the glmS ribozyme suggests that titration of this phosphate may inhibit binding of GlcN6P to the glmS ribozyme.

Kinetic analysis of MaN6P activation of the glmS ribozyme

We examined the ability of MaN6P to activate the glmS ribozyme under single turnover conditions. We measured the kmax for the reaction and found that it increases with increasing pH, plateaus at about 0.7 sec−1 and has an apparent pKa of ~7.8 [Figure 6D]. This rate is only about 7-fold slower than for activation by GlcN6P and has a pKa in the same range. However, the K1/2 for MaN6P for the glmS ribozyme is higher than that for GlcN6P. The highest concentration of MaN6P used in this analysis was 50 mM, which limits the accuracy with which we are able to determine the K1/2. In fact, at all pH’s the K1/2 was too large to be measured accurately but it is at least 15 mM and is possibly higher than 50 mM [Figure S3].

DISCUSSION

The glmS ribozyme binds GlcN6P leading to self-scission of the RNA backbone. However, unlike other riboswitch ligands that induce a conformational change in the RNA upon binding, the role of GlcN6P appears to be entirely chemical (5, 8). We have solved a series of crystal structures of the glmS ribozyme that show that the active site is pre-organized in the absence of GlcN6P. In fact, we observe some residual binding of GlcN6P to the product state of the ribozyme, suggesting that many of the ribozyme elements required for GlcN6P binding are retained following cleavage [Figure 3]. Additionally, mutation of a key guanosine predicted to activate the nucleophile of the reaction does not affect GlcN6P binding or significantly alter the conformation of the active site [Figure 4]. New kinetic analysis further supports this conclusion, as the pKa of kmax/K1/2 for the reaction is consistent with the amine of GlcN6P playing a key role in catalysis [Figure 6]. Structures of the glmS ribozyme bound to sugar variants of GlcN6P, including the activating sugar, MaN6P and the non-activating sugar, Glc6P, suggest that the ribozyme uses both catalytic and structural mechanisms to select against incorrect ligands [Figure 5]. Additionally, we measured the rate of glmS ribozyme activity in the presence of MaN6P, a diastereomer of GlcN6P with inverted stereochemistry at the amine [Figure 6]. This kinetic analysis demonstrates that the glmS ribozyme binds and is activated by MaN6P but at higher concentrations than GlcN6P, consistent with the structure of the glmS ribozyme bound to MaN6P [Figures S1 and S3].

GlcN6P recognition through the catalytic cycle of the glmS ribozyme

Previous biochemical and structural work indicated that the active site of the glmS ribozyme is almost fully formed even in the absence of bound ligand (5, 8, 9). Unlike other riboswitches, no large structural rearrangements upon binding could be detected using any solution technique (5, 8). This deviation from the traditional mode of ligand binding by riboswitches may also contribute to the low affinity binding of GlcN6P by the glmS ribozyme [Figure 6]. Other riboswitches tend to have high affinity for their cognate ligands, with Kd’s as low as 1 nM (20). Even the glycine riboswitch, which has one of the weakest reported affinities, binds glycine with a Kd of around 30 μM (20, 21). In contrast, the glmS ribozyme has a K1/2 for GlcN6P of at least 1 mM.

Cleavage by the glmS ribozyme results in the release of nucleotides 5′ of the scissile phosphate. In structures of the pre-cleaved, sugar bound glmS ribozyme complex, these nucleotides do not interact with GlcN6P; all of the nucleotides responsible for sugar binding are within the core of the RNA and are present in the product form of the ribozyme (3, 9). However, the initial structure of the cleaved form of the ribozyme from T. tengcongensis did not provide any evidence for GlcN6P bound in the active site (9). We independently solved the structure of the post-cleavage form of the glmS ribozyme from B. anthracis. In one active site we see clear density for the entire molecule of GlcN6P and in the other active sites we see density for at least the phosphate atom [Figure 3], suggesting that the glmS ribozyme retains affinity for GlcN6P following cleavage. The difference in cofactor binding between the B. anthracis structure reported here and the earlier T. tengcongensis structure is most likely a consequence of the T. tengcongensis crystals being grown at low pH (~5.3) where the K1/2 for GlcN6P is ~6 mM (10). At this pH, the phosphate moiety of the sugar would be titrated to neutral, which would reduce the ability of the sugar to interact with Mg2+ and reduce the binding affinity. This is supported by the initial, low pH, T. tengcongensis glmS ribozyme structures where there is no evidence of metal ions coordinating the sugar phosphate.

Additionally, we solved the structure of an inactive mutant of the B. anthracis glmS ribozyme. In this ribozyme, the guanosine (G33) predicted to act as the general base to deprotonate the 2′-OH nucleophile has been mutated to an adenosine. A similar structure of the T. tengcongensis ribozyme has been reported by Klein et al (4). This mutant ribozyme is extremely slow, over a factor of 105 less active than the wild type glmS ribozyme (3, 4). In the mutant structure, the A is positioned in a similar way to the G in the wild type structure [Figure 4]. The only significant difference between the structure of the mutant and wild type ribozymes is a slight shift in the position of the nucleotide leading to the loss of a hydrogen bond between the N1 of the purine and the 2′-OH nucleophile (4). This implicates G33 in the catalytic mechanism, acting not to position the 2′-OH, but in another role. Additionally, this nucleotide is located across the scissile phosphate from the GlcN6P binding pocket and mutation of G33 appears to have no effect on GlcN6P binding, suggesting that G33 and the sugar cofactor play different roles in the catalytic mechanism.

Selectivity of the glmS ribozyme against non-cognate ligands

The glmS ribozyme is responsive to GlcN6P concentrations to regulate sugar levels within the cell. Activation of the ribozyme by ligands other than GlcN6P would deregulate this process and compromise the integrity of the bacteria. The feedback control mechanism of GlcN6P over the glmS gene would be circumvented by alternate sugars, both naturally occurring and foreign. Here we present two crystal structures of the glmS ribozyme bound to analogs of GlcN6P [Figure 5]. One sugar, Glc6P is structurally identical to GlcN6P with the substitution of oxygen (at C2) for nitrogen. The other sugar, MaN6P is chemically identical to GlcN6P but has the stereochemistry inverted at C2. Both structures have RNA backbones that are superimposable with the structure of the glmS ribozyme bound to GlcN6P. These structures raise the question: How does the glmS ribozyme discriminate between GlcN6P and other similar sugars?

Glc6P is a naturally occurring, structurally similar, GlcN6P analog. Most of the glucose that enters a cell is converted into Glc6P. There is clear density for the entire Glc6P molecule as well as the two coordinating magnesium ions, in all four active sites in the B. anthracis glmS crystal structure. However, the rate of the cleavage reaction with Glc6P is the same as the uncatalyzed rate (18). Further, there is some evidence that Glc6P can actually inhibit the reaction. Under subsaturating concentrations of GlcN6P, very high concentrations (10 mM) of Glc6P can reduce the rate of ribozyme cleavage (18). This indicates that although Glc6P is binding with at least moderate affinity to the glmS ribozyme, it is entirely unable to promote the reaction and suggests that the ribozyme discriminates against this sugar molecule using a catalytic mechanism.

How is the glmS ribozyme able to exclude molecules that contain a primary amine, which appears to be the key functional group for reactivity? All previous studies showed that deletion of that functional group on the small molecule led to cleavage rates for the glmS ribozyme similar to what is seen in the absence of small molecule activation (5, 18). Additionally, molecules that retain the primary amine and are able to activate the ribozyme, such as glucosamine and serinol, have much weaker apparent binding affinity than GlcN6P (18). These molecules are missing at least the phosphate moiety of the ligand. Presumably the deletion of functional groups is detrimental to binding as potential hydrogen bonding partners are lost. Structures of the B. anthracis glmS ribozyme indicate that the phosphate moiety interacts with at least two Mg2+ ions, providing additional ionic interactions between the ligand and the ribozyme, an interaction that appears to be somewhat lost at low pH, where the phosphate becomes protonated and uncharged, thereby reducing it’s ability to coordinate Mg2+ and resulting in a significant increase of the K1/2 of GlcN6P for the glmS ribozyme.

The glmS ribozyme is activated by the stereochemical analog of GlcN6P, MaN6P. This molecule is chemically identical to GlcN6P, providing the same repertoire of functional groups as the natural ligand, but the stereochemistry is inverted at C2, which positions the primary amine on the same side of the sugar ring as the phosphate moiety. In the structure of the glmS ribozyme bound to MaN6P, there is only weak density observed for the sugar molecule in the active site of the ribozyme but the molecule retains all of the same hydrogen bonding partners as GlcN6P [Figure 5]. We estimate the K1/2 for MaN6P to be at least 20-fold higher than for GlcN6P. That such a slight change in the structure of the sugar molecule could impact the binding affinity of the ligand without having a similar effect on the rate suggests that there is a structural mechanism for discriminating against non-cognate sugars [Figure 6].

Two mechanisms seem to be in play in the activation of the glmS ribozyme by small molecules: first a chemical mechanism seems to be the driving force behind rejecting the GlcN6P mimic, Glc6P. Second, molecules with primary amines that retain the ability to activate the ribozyme appear to bind with significantly lower affinity than GlcN6P. This is even true for subtle changes, such as the inversion of the stereochemistry of the C2-amine or lack of the phosphate group. By employing both of these mechanisms, the glmS ribozyme is able to select against ligands that are structurally and chemically similar to GlcN6P.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank H. Robinson, A. Heroux, S. Myers, A. Soares and the beamline staff at X25 and X29 at the NSLS at Brookhaven National Laboratory; M. Strickler and the CSB core staff; A. Pyle and V. Serebrov for assistance with the quench-flow apparatus; Y. Xiong, R. Breaker, P. Loria, J. Wang, D. Hiller and members of the Strobel Lab for comments and discussions.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation (MCB0544255) to S.A.S.

ABBREVIATIONS

- B. anthracis

Bacillus anthracis

- GlcN6P

glucosamine-6-phosphate

- Glc6P

glucose-6-phosphate

- MaN6P

mannosamine-6-phosphate

- T. tengcongenis

Thermoanerobacter tengcongensis

Footnotes

Atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org, under accession codes XXXX, XXXX, XXXX, XXXX and XXXX.

References

- 1.Cochrane JC, Strobel SA. Catalytic strategies of self-cleaving ribozymes. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:1027–1035. doi: 10.1021/ar800050c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fedor MJ, Williamson JR. The catalytic diversity of RNAs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:399–412. doi: 10.1038/nrm1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cochrane JC, Lipchock SV, Strobel SA. Structural investigation of the GlmS ribozyme bound to Its catalytic cofactor. Chem Biol. 2007;14:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein DJ, Been MD, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Essential role of an active-site guanine in glmS ribozyme catalysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:14858–14859. doi: 10.1021/ja0768441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winkler WC, Nahvi A, Roth A, Collins JA, Breaker RR. Control of gene expression by a natural metabolite-responsive ribozyme. Nature. 2004;428:281–286. doi: 10.1038/nature02362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winkler WC, Breaker RR. Regulation of bacterial gene expression by riboswitches. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2005;59:487–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mandal M, Breaker RR. Gene regulation by riboswitches. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:451–463. doi: 10.1038/nrm1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hampel KJ, Tinsley MM. Evidence for preorganization of the glmS ribozyme ligand binding pocket. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7861–7871. doi: 10.1021/bi060337z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein DJ, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Structural basis of glmS ribozyme activation by glucosamine-6-phosphate. Science. 2006;313:1752–1756. doi: 10.1126/science.1129666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein DJ, Wilkinson SR, Been MD, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Requirement of Helix P2.2 and Nucleotide G1 for Positioning the Cleavage Site and Cofactor of the glmS Ribozyme. J Mol Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu MZ, Lee YC. Comparison of chemical and enzymatic synthesis of 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-D-mannose 6-phosphate: a new approach. Carbohydr Res. 2001;330:413–419. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)00299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Likelihood-enhanced fast translation functions. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2005;61:458–464. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905001617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Meth Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pannu NS, Murshudov GN, Dodson EJ, Read RJ. Incorporation of prior phase information strengthens maximum-likelihood structure refinement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:1285–1294. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998004119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winn MD, Isupov MN, Murshudov GN. Use of TLS parameters to model anisotropic displacements in macromolecular refinement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2001;57:122–133. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900014736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeLano WL. DeLano Scientific. San Carlos, CA: 2002. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCarthy TJ, Plog MA, Floy SA, Jansen JA, Strauss-Soukup JK, Soukup GA. Ligand requirements for glmS ribozyme self-cleavage. Chem Biol. 2005;12:1221–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim J, Grove BC, Roth A, Breaker RR. Characteristics of ligand recognition by a glmS self-cleaving ribozyme. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:6689–6693. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandal M, Boese B, Barrick JE, Winkler WC, Breaker RR. Riboswitches control fundamental biochemical pathways in Bacillus subtilis and other bacteria. Cell. 2003;113:577–586. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mandal M, Lee M, Barrick JE, Weinberg Z, Emilsson GM, Ruzzo WL, Breaker RR. A glycine-dependent riboswitch that uses cooperative binding to control gene expression. Science. 2004;306:275–279. doi: 10.1126/science.1100829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stryer L. Biochemistry. 4. W.H. Freeman and Company; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.