Abstract

The activity of cyclin dependent kinases (CDKs), which are key regulators of the eukaryotic cell cycle, is regulated through post-translational mechanisms, including binding of a cyclin and phosphorylation. Previously studies have shown that Leishmania mexicana CRK3 is an essential CDK that is a functional homologue of human CDK1. In this study, recombinant histidine tagged L. mexicana CRK3 and the cyclin CYCA were combined in vitro to produce an active histone H1 kinase that was inhibited by the CDK inhibitors, flavopiridol and indirubin-3′-monoxime. Protein kinase activity was observed in the absence of phosphorylation of the T-loop residue Thr178, but increased 5-fold upon phosphorylation by the CDK activating kinase Civ1 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Seven recombinant L. major CRKs (1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7 and 8) were also expressed and purified, none of which were active as monomers. Moreover, only CRK3 was phosphorylated by Civ1. HA tagged CYCA expressed in L. major procyclic promastigotes was co-precipitated with CRK3 and exhibited histone H1 kinase activity. These data indicate that in Leishmania CYCA interacts with CRK3 to form an active protein kinase, confirm the conservation of the regulatory mechanisms that control CDK activity in other eukaryotes, but identifies biochemical differences to human CDK1.

1. Introduction

Despite recent advances in understanding of the cell biology of the protozoan parasite, Leishmania, its cell cycle remains relatively unexplored. Fundamentally, the parasite's cell cycle is the same as every other eukaryote's featuring growth, DNA replication, mitosis and cytokinesis. In addition, Leishmania must ensure the duplication and faithful segregation of their singular organelles: the nucleus, the kinetoplast, the flagellum and the Golgi apparatus. Leishmania possess orthologues of many of the protein kinases that have been shown to be key players in controlling the eukaryotic cell cycle, including cyclin-dependent kinases, Aurora and polo-like kinases [1-6], but direct evidence linking these orthologues to a role in Leishmania cell cycle control is limited [1,7]. In other eukaryotes, cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) act at the boundaries between different cell cycle stages, to prevent premature or inappropriate transition through key checkpoints. Their activity is tightly regulated through a variety of mechanisms including binding of a cyclin partner and phosphorylation [8]. Cyclin binding is further regulated at the transcriptional level, resulting in cyclical expression, and post-translationally through targeted destruction by the proteasome [9]. There are two main sites of phosphorylation on CDKs: close to the catalytic site, at Y15 and T14 (in human CDK1), and on the activation or T-loop, at T161 (in human CDK1). Phosphorylation of Y15 and T14 has an inhibitory effect [10,11] which can be reversed by dephosphorylation by the CDC25 phosphatase [12]. Phosphorylation at the T-loop residue is required for the full activity of CDK1, CDK2 [13] and CDK4 [14] resulting in a dramatic conformational change in the T-loop, creating the substrate binding site and orientating ATP correctly for phospho-transfer [15]. However, CDK6 activity in vivo appears to be independent of its T-loop phosphorylation status [16].

In mammalian cells, the kinase responsible for phosphorylating the T-loop threonine (CDK activating kinase or CAK) is itself a CDK (CDK7) that is found in a complex with cyclin H and an assembly factor, MAT1 [17]. In contrast, in budding yeast the CDK activating kinase consists of a single protein, known as CAK or Civ1 (CAK in vivo) [18]. Both can phosphorylate CDKs but they possess quite different substrate specificities: Civ1 is predominantly cytoplasmic [19] and preferentially phosphorylates CDK monomers, whilst CDK7/cyclin H/MAT1 favours CDK/cyclin complexes [20]. In vitro, CDK7/cyclin H (with or without MAT1) can phosphorylate CDK1, CDK2, CDK3, CDK4 and CDK6 [14,21,22]. However, although T-loop phosphorylation of CDK4 is required for activity [14], CDK7 may not be responsible for this phosphorylation in vivo [16], implying that there may be more than one human CAK enzyme. Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Civ1, can also phosphorylate and activate most mammalian CDKs in vitro [20,23,24], implying that the effect of the T-loop phosphorylation in vitro is independent of the activating enzyme. No CDK activating kinase has been identified in the L. major genome [5].

In comparison with S. cerevisiae, Leishmania possess a relatively expanded repertoire of 12 cdc2-related kinases [5], perhaps reflecting the relative complexity of the parasite's cell division cycle and the need to integrate that with the developmental life cycle, in which the parasite oscillates between proliferative and cell-cycle arrested forms. CRK3 is the best described of the leishmanial CDKs. It is highly conserved between different species of Leishmania (for example, there is only one amino acid difference between CRK3 of L. mexicana, L. major and L. donovani), complements a Schizosaccharomyces pombe cdc2 mutant [25] and functions at the G2/M boundary [7], suggesting it is a functional CDK1 homologue. CRK3 is predicted to be regulated by similar mechanisms to other CDKs, since it possesses a conserved cyclin-binding domain and the three regulatory phosphorylation sites (Aligned to T14, Y15 and T160 of human CDK1) [2]. Eleven cyclins have been identified in the L. major genome and these fall into 3 classes based on their sequence characteristics [4]; mitotic cyclins (CYCA, CYC3, CYC6 and CYC8), PHO80-like cyclins (CYC2, CYC4, CYC5, CYC7, CYC10, CYC11) and transcriptional cyclins (CYC9). All the cyclins are conserved with other trypanosomatids, such as Trypanosoma brucei, except CYCA, which appears to be specific to Leishmania species. To date the only CDK:cyclin pair identified in Leishmania is the L. donovani CRK3:CYC1 (the syntenic homologue of L. major CYCA) [26].

In the present work we successfully expressed, purified and reconstituted an active recombinant CRK3:CYCA protein kinase complex in vitro. Recombinant CRK3:CYCA has histone H1 protein kinase activity in the absence of phosphorylation on the T-loop threonine, a feature that distinguishes it from mammalian CDK1. Phosphorylation of the T-loop threonine by S. cerevisiae Civ1, however, is associated with a 5-fold increased kinase activity. Thus these results confirm that the activity of the leishmanial CDK, CRK3, is regulated in a similar fashion to other eukaryotic CDKs, but that CRK3:CYCA has some differences from human CDK1 .

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Parasites

L. major (MHOM/JL/80/Friedlin) and promastigotes were grown in modified Eagle's medium with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated foetal calf serum (designated complete HOMEM medium) at 25°C [27].

2.2 Cloning Leishmania CRKs and CYCA

N-terminally histidine tagged L. mexicana CRK3 was expressed from plasmid pGL751, which was constructed as follows: CRK3 was PCR amplified using primers OL225 and OL894 (Table 1), which added Nde1 and Xho1 sites onto the 5′ and 3′ ends of the ORF respectively. The PCR product was cloned into Nde1/Xho1 digested pET28a to create pGL751. To make a non-tagged version, CRK3 was excised from pGL751 using NdeI/BamH1 and cloned into pET21a generating pGL1072. L. mexicana CYCA was amplified from genomic DNA with oligonucleotides primers OL813 and OL814 which added Nde1 and Xho1 sites onto the 5′ and 3′ end of the ORF respectively. This was cloned into Nde1/Xho1 digested pET21a, to give plasmid pGL630, which encodes CYCA with a C-terminal six histidine tag.

Table 1.

| Gene | Destination vector | Primer | Primer sequence 5′ to 3′ |

|---|---|---|---|

| L. mexicana CRK3 | pET28a | OL225 | GAATTCCATATGTCTTCGTTTGGCCGTGTGA |

| L. mexicana CRK3 | pET28a | OL894 | CTCGAGCTACCAACGAAGGTCGCTGA |

| L. mexicana CRK3 | Mutagenesis primer | OL877 | CCCATGCACACCTACGAGCACGAGGTGGTT ACG |

| L. mexicana CRK3 | Mutagenesis primer | OL878 | CGTAACCACCTCGTGCTCGTAGGTGTGCAT GGG |

| L. mexicana CYCA | pET21a | OL813 | CATATGGCGGTCCCACTGCGAATG |

| L. mexicana CYCA | pET21a | OL814 | CTCGAGCGCAGAAGTTGAAATGAA |

| L. major CRK1 | pET15b | OL1783 | CCATATGACCAGCCGGTACGAGCGGCA GGAGAAGATC |

| L. major CRK1 | pET15b | OL1784 | CGGATCCCTAAAACTGGAGGCTAAAGTACG GGTG |

| L. major CRK2 | pET15b | OL1785 | CCATATGCGGAGCAGCGGCCCCACCCCAGC GC |

| L. major CRK2 | pET15b | OL1786 | CGGATCCTTACGACTGCTGCTGCTGCTGCTG CTG |

| L. major CRK3 | pET15b | OL1787 | CCATATGTCTTCGTTTGGCCGTGTTACCGCCC |

| L. major CRK3 | pET15b | OL1788 | CGGATCCCTACCAGCGAAGGTCACTGAACC ACGGG |

| L. major CRK4 | pET15b | OL1789 | CCATATGTCGACGGCGGGTCGGTACAAGCA CG |

| L. major CRK4 | pET15b | OL1790 | CGGATCCTCATAGCAAGTGGCAGGCCTCCA TCGTC |

| L. major CRK6 | pET15b | OL1791 | CCATATGTCCGCGTCAGTGAACGACTTGGA TG |

| L. major CRK6 | pET15b | OL1792 | CGGATCCCTACGCATCCTTCATAAAGGGGT GTTCC |

| L. major CRK7 | pET15b | OL1793 | CCATATGGACAAGTACGCGTTGGGGCCG GTTATC |

| L. major CRK7 | pET15b | OL1794 | CGGATCCTCATGCACGCAGCAAGGTATCTG AGAG |

| L. major CRK8 | pET15b | OL1795 | CCATATGGGAGGGGAACTGGATAACCAGAAC |

| L. major CRK8 | pET15b | OL1796 | CGGATCCTCAATGCTCCAGCTCCTTCCGCTT GACC |

| L. mexicana CYCA | pXG | OL1935 | CCC CGG GAT GGC GGT CCC ACT GCG AAT GAG GA |

| L. mexicana CYCA | pXG | OL1936 | TGG ATC CTC AGG CAT AGT CCG GGA CGT CGT AGG GGT |

| L. mexicana CYCA | pXG | OL1937 | CCC CGG GAT GTA CCC CTA CGA CGT CCC GGA CTA TGC |

| L. mexicana CYCA | pXG | OL1938 | GTG GAT CCT CAC GCA GAA GTT GAA ATG A AA GG |

Restriction endonuclease sites are underlined

Mutagenesis sites are in bold

To generate histidine tagged L. major CRK3, PCR amplification of LmjF36.0550 was performed using L. major genomic DNA, oligonucleotides OL1787 and OL1788 and Invitrogen Thermozyme polymerase. The PCR product was subcloned into pET15b, which was pre-digested with BamHI and NdeI, generating pGL1340. L. major CRK1 (LmjF21.1080; pGL1338), CRK2 (LmjF05.0550; pGL1339), CRK4 (LmjF16.0990; pGL1616), CRK6 (LmjF27.0560; pGL1341, CRK7 (LmjF26.0040; pGL1349), CRK8 (LmjF11.0110; pGL1342) in combination with the oligonucleotides shown in Table 1 were similarly PCR amplified and cloned into pET15b.

To create HA epitope tagged L. mexicana CYCA, the gene was amplified with oligonucleotides incorporating the HA tag at the N or C-terminus (OL1937 and OL1938 and OL1935 and OL1936 respectively) and cloned into the SmaI/BglII site of pXG [28].

To generate CRK3T178Ehis site directed mutagenesis was performed using manufacturers instructions (QuikChange kit, Stratagene) on plasmid pGL751 using oligonucleotide primers OL877 and OL878, resulting in plasmid pGL1071.

2.3 Protein purification and kinase assays

L. mexicana CRK3his was expressed in BL21 (DE3) pLysS Escherichia coli cells (Stratagene), inducing with 100μM IPTG at 20°C overnight, and purified as described previously [2]. For L. mexicana CYCA, BL21 (DE3) pLysS E. coli cells were transformed with plasmid pGL630. Cells were induced for protein expression at 19°C over night using 5mM IPTG and CYCAhis was purified as described for CRK3his. Plasmids expressing L. major CRK1-CRK8 were transformed into BL21 (DE3) pLysS E. coli cells and induced with 1mM IPTG at 19 °C over night. All the CRKs produced soluble protein, but expression levels varied from low (CRK6 and CRK8) to high (CRK1, CRK2, CRK3 and CRK7). S. cerevisiae Civ1-GST was purified as described previously [24]. The expression and purification of CRK3:CYC6 will be described elsewhere (Walker et al., manuscript in preparation).

Protein kinase assays were performed as described previously [2]. Recombinant protein kinase was incubated in 50 mM MOPS pH 7.2, 20 mM MgCl2, 10 mM EGTA, 2 mM DTT, 4 μM ATP, plus 1 μCi γ-P32ATP (3000Ci/mmol) and 2.5 μg histone H1 per reaction. Reactions were incubated at 30 °C for 30 min. Final volume of each reaction was 20 μl and at the end of the 30 min incubation 20 μl of two times Laemmli protein loading buffer was added to stop the reaction, samples then were incubated at 100 °C for 5 min and loaded on 12% acrylamide gel. The gel was dried and exposed to KODAK sensitive film overnight. Protein kinase activity was quantified by scanning the dried gels on a Typhoon phosphor imager (GE Healthcare).

To assess the interaction of L. mexicana CRK3 with CYCAhis in vitro, BL21 DE3 E. coli cells were transformed with plasmid pGL630 to express CYCAhis. Cell lysate was incubated with 200 μl of Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) bead slurry for 5 min at room temperature and centrifuged for 5 min at 2100 g. This column of Ni-NTA + CYCAhis was washed 2 times with PBS 7.4 and incubated with a soluble bacteria lysate containing non tagged CRK3 for 30 min, mixing at room temperature to permit the binding of the two proteins. The beads were then centrifuged at 1000 g for 5 min. The column was washed 2 times with PBS 7.4 and eluted in 100 μl fractions with phosphate buffer consisting of 100 mM NaPi 7.4, 10 mM NaCl and 0.5 M imidazole (pH 8.0). 10 μl of each elution fraction was mixed with 10 μl Laemmli protein loading buffer and the total volume of 20 μl was loaded on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel. The proteins on the gel were transferred to a PVDF membrane and a western blot was performed using α-CRK3 antibodies [7] diluted 1:2000.

2.4 Immunoprecipitation

L. major were transformed with plasmids pGL1388 and pGL1389 using the method of Robinson and Beverley [29]. Transformants were selected in the presence of 50μg ml−1 G418. These cell lines were grown to mid log phase and 50ml of culture was harvested at 1000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The cell pellet was then washed twice in cold PBS and resuspended in 1ml of IP lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet P40) containing protease inhibitors (100 μg ml−1 leupeptin, 500 μg ml−1 Pefabloc, 5 μg ml−1 pepstatin, 1mM 1-10, phenanthroline, 1mM EDTA and 1mM EGTA). To this lysis suspension, 50 μl of HA affinity purification matrix (Roche) was added and an overnight incubation at 4 °C with agitation was done. The matrix was then washed 3 times with 1ml of lysis buffer and resuspended in 50 μl of lysis buffer. 10 μl was loaded on an SDS-PAGE gel, which was used either for Western blotting or silver staining. 5 μl of matrix was used in a kinase assay using histone H1 as a substrate. For western blots to detect HA tagged proteins, monoclonal mouse HRP conjugated antibody (Roche) was used diluted at 1 in 500.

3. Results

3.1 Leishmania CYCA binds and activates CRK3 in vitro

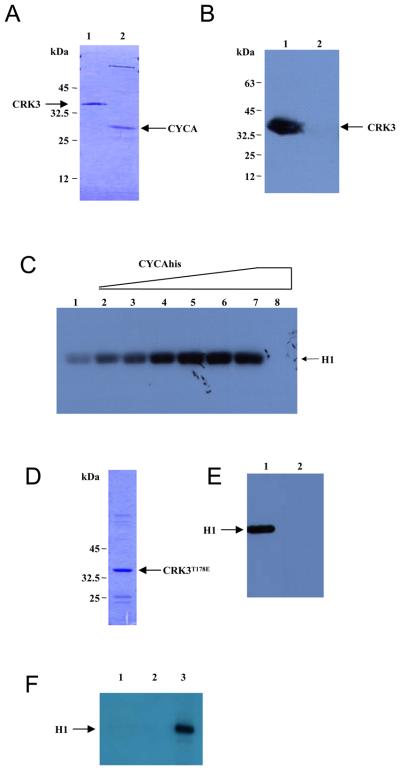

Leishmania mexicana CRK3 and CYCA were histidine tagged, expressed and purified from Escherichia coli (Fig. 1A, lanes 1 and 2 respectively). A construct expressing CRK3 without a histidine tag was also generated. To investigate the interaction of CRK3 and CYCA, an in vitro binding assay was carried out whereby CYCAhis was bound onto a Ni-NTA column and then incubated with an E. coli cell lysate containing non tagged CRK3. After washing to remove non-specifically bound proteins, CYCAhis was eluted from the column and the presence of co-eluting CRK3 in the eluant was assessed by Western blotting with an anti-CRK3 antibody [2]. CRK3 was found to bind immobilised CYCAhis (Fig. 1B, lane 1) but not control beads (lane 2), showing that L. mexicana CRK3 can interact with CYCA in vitro. Recombinant monomeric CRK3his had negligible histone H1 protein kinase activity (Fig. 1C, lane 1), but when increasing concentrations of CYCAhis were pre-incubated with a fixed concentration of CRK3his, escalating histone H1 kinase activity was detected (lanes 2-7). No histone H1 kinase activity was detected with cyclin alone (lane 8). Optimal CRK3his:CYCAhis protein kinase activity was detected when CRK3 and CYCA were mixed in an approximate 1:1 molar ratio (lane 6).

Figure 1. L. mexicana CRK3:CYCA.

(A) SDS PAGE of CRK3his (lane 1) and CYCAhis (lane 2) purified from E. coli and stained with Coomassie blue R-250. (B) CYCAhis binds CRK3. Ni-NTA beads, with (lane 1) or without (lane 2) bound CYCAhis, were incubated with E. coli lysates expressing CRK3, washed, eluted and the eluted protein subjected to Western blot analysis with α-CRK3 antibody. (C) Activation of CRK3:CYCA. Phosphorylation of histone H1 by L. mexicana CRK3:CYCA was performed by mixing increasing quantities of CYCAhis (0 μg-3 μg in 0.5 μg increments from lanes 1-7) to a fixed amount of CRK3his (4 μg, lanes 1-7) in an in vitro kinase assay buffer containing 2.5 μg of histone H1 per reaction and γ-P32-ATP. Lane 8 contains 3 μg CYCAhis only. Phosphorylated histone H1 was detected following SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (D) SDS PAGE of CRK3T178Ehis purified from E. coli and stained with Coomassie blue R-250. (E) CRK3T178Ehis kinase assay with CYCA. 4 ug of CRK3his (lane 1) or CRK3T178Ehis (lane 2) was incubated with 3 μg of CYCAhis and histone H1 kinase activity assessed as in panel C. H1; histone H1. (F) CRK3T178Ehis kinase assay with CYC6. 3.5 μg of CRK3T178Ehis (lanes 1 and 2) or CRK3his (lane 3) was incubated with (lanes 2 and 3) or without (lane 1) 3 μg of CYC6his and histone H1 kinase activity assessed as in panel C.

Phosphorylation of the canonical Thr residue in the T-loop of CDKs is essential for maximal activity in yeast, plants and mammals [30]. Substitution of a Thr residue with a negatively charged Glu can mimic phosphorylation of the Thr [31] and when applied to the T-loop residue in the Plasmodium CDK, PfPK5, resulted in a 5 to 10-fold activation [32]. To test if this was also the case for CRK3, site directed mutagenesis was carried out on the conserved T-loopThr residue (Thr 178) of CRK3his to produce CRK3T178Ehis. Affinity purified CRK3T178Ehis (Figure 1D) lacked histone H1 kinase activity both in the absence (Figure 1F, lane 1) and presence of CYCA (Figure 1E, lane 2). The results show that CYCAhis is able to activate CRK3his (Figure 1E, lane 1) but not CRK3T178Ehis (lane 2), indicating that the mutation abolishes histone H1 kinase activity. CRK3 is also activated by the cyclin CYC6 to produce a kinase with histone H1 kinase activity (Walker et al., manuscript in preparation; Figure 1F, lane 3). CRK3T178Ehis, however, is not activated by CYC6 (Figure 1F, lane 2), showing that T178 is essential for CRK3 protein kinase activity with two different cyclin partners.

L. mexicana CRK3his affinity purified from the parasite has been shown to have histone H1 kinase activity and to be inhibited by a variety of CDK inhibitors [2,33]. Although it is not known how many cyclins bind and activate CRK3 or the Thr178 phosphorylation status of CRK3 in vivo, the CRK3 purified from L. mexicana promastigotes could be compared to the recombinant purified CRK3his:CYCAhis by comparing their inhibition with two well established CDK inhibitors, flavopiridol [34] and indirubin-3′-monoxime [35]. IC50 values of 102 nM for flavopiridol and 3.1 μM for indirubin-3′-monoxime with CRK3his:CYCAhis (Figure S1) were similar to the IC50 values of 100 nM [7] and 1.35 μM [33] respectively for CRK3his affinity purified from L. mexicana. The variation in IC50 between recombinant CRK3 and that purified from the parasite might be due to the presence of a complex mixture in the parasite-derived enzyme preparation. Monomeric CRK3, CRK3:CYCA, CRK3:CYC6 or potentially other CRK3:cyclin complexes might be present, possibly each with different inhibition profiles.

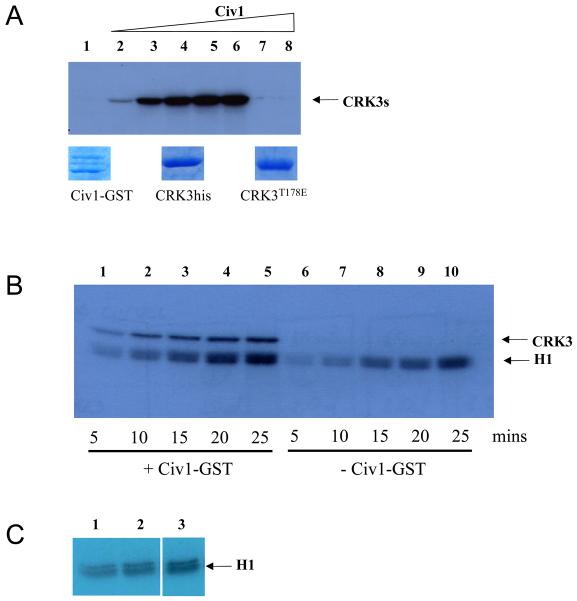

The genome of Leishmania major contains over 170 protein kinase genes [5], but it has not been possible to identify using bioinformatics analysis which of these genes might encode a functional Leishmania CDK activating kinase (CAK). For this reason we tested if the GST-tagged S. cerevisiae CAK (Civ1-GST) [18], expressed and purified from E. coli (Fig 2A, lower panel), would phosphorylate CRK3 on Thr178. The yeast Civ1-GST was able to phosphorylate recombinant CRK3his in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 2A, lanes 2-6, upper panel). Civ1-GST did not auto-phosphorylate (lane 7) or phosphorylate CRK3T178Ehis (lane 8) indicating that Thr178 in CRK3 was the most likely site of phosphorylation. In order to assess whether the phosphorylation of CRK3his Thr178 would increase its protein kinase activity, a time course was carried out where CYCAhis and CRK3his were incubated in the presence and absence of Civ1-GST and histone H1 kinase activity assessed at various time intervals (Figure 2B). A 5-fold increase in phosphorylated histone H1 was observed after Thr178 phosphorylation by Civ1-GST (compare histone H1 signal in lanes 5 and 10). Civ1-GST does not phosphorylate histone H1 significantly (Figure 2C, compare lane 1, in the absence of Civ1, with lanes 2 and 3 in the presence of 0.3mg and 1.8mg Civ1 respectively).

Figure 2. Phosphorylation of CRK3 with a CDK-activating kinase.

(A) Upper panel. Phosphorylation of CRK3his or CRK3T178Ehis by S. cerevisiae Civ1-GST. CRK3his (3 μg, lanes 1-7) or CRK3T178Ehis (3 μg, lane 8) were incubated with increasing concentrations of Civ1-GST (lanes 1, 0 μg, lanes 2-6, 0.5μg increasing in 0.5μg increments, lanes 7 and 8, 2.5μg) for 30 mins in the presence of γ-P32-ATP. Phosphorylated CRK3his or CRK3T178Ehis was detected following SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Lower panel. Coomassie blue R-250 stained protein used in the assay. (B) Histone H1 kinase assay. CRK3:CYCA complex (4 μg) was incubated with 0.5 μg Civ1-GST (lanes 1-5) or control buffer (lanes 6-10) for 15 mins prior to addition of histone H1 substrate. Samples were taken at 5, 10, 15 and 20 mins after addition of histone H1 and analysed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (C) Histone H1 is not a Civ1-GST substrate. Histone H1 was incubated in the presence of Civ1-GST (0ug, lane 1; 0.3 μg in lane 2 and 1.8 μg in lane 3) for 30 mins in the presence of γ-P32-ATP. Phosphorylated histone H1 was detected following SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

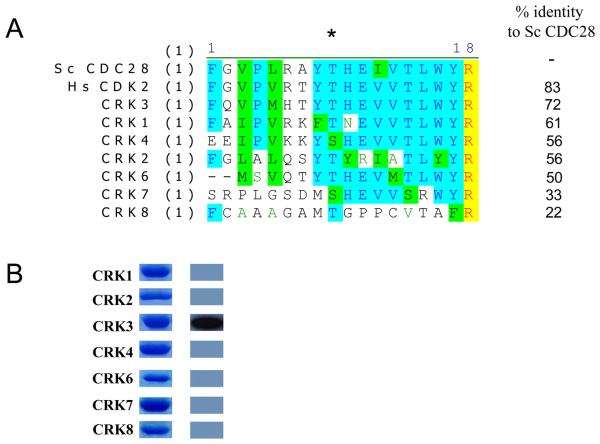

The natural substrate for Civ1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is CDC28 [18]. The fact that Leishmania CRK3 can be phosphorylated by Civ1 indicates that the phosphorylation site is conserved between these two species (see Figure 3A) and implies that this phosphorylation may play a role in regulating CRK3 activity, as it does for CDC28 [18]. L. major has 12 CRKs and 10 of these have a conserved T-loop Thr or Ser residue [4]. To assess if other CRKs could be phosphorylated by Civ1-GST, L. major CRKs 1-8 (Fig 3B) were cloned into pET15b and expressed and purified from E. coli (Figure 3B). CRK5 was not included as it has been reclassified as a MOK-family MAP kinase and is unlikely to be cyclin-dependent [4]. L. major CRKs were chosen as the L. mexicana genome was unavailable for analysis at the time and the CRK family in that species was unknown. Only L. major CRK3his was found to be phosphorylated by Civ1-GST (Figure 3B). The purified monomeric CRKs were tested for histone H1 kinase activity, but none were active (data not shown). These data show that yeast Civ1-GST has specificity for CRK3, the Leishmania CRK with the highest homology to Civ1's natural substrate, CDC28 (Figure 3A), and that Leishmania CRKs are not active histone H1 kinases, when expressed as soluble monomeric proteins. This does not, however, preclude their activation by a cognate cyclin partner(s), yet to be identified or activity as monomers towards other substrates.

Figure 3. Phosphorylation of Leishmania CRKs with Civ1.

(A) Sequence alignment of L. major CRK1-4, 6-8, S. cerevisiae CDC28, the natural substrate for Civ1, and human CDK2. The T-loop residue is indicated (*) (B) Phosphorylation of L. major CRKs by Civ1-GST. Left panel: purified recombinant histidine-tagged CRK proteins. Right panel: Phosphorylation by Civ1-GST.

3.2 An active CRK3:CYCA complex in L. major

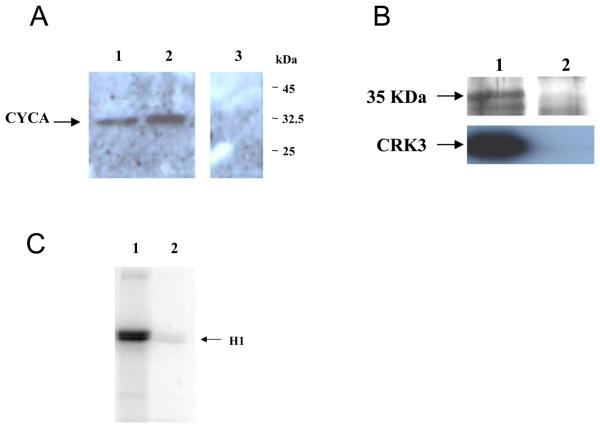

CYCA was amplified with a C- or N-terminal HA tag and cloned into an episomal expression vector pXG to generate pGL1388 (N-terminal HA tag; HA-CYCA), and pGL1389 (C-terminal HA tag; CYCA-HA). L. major promastigotes were transfected with each plasmid and cell lines resistant to G418 isolated (designated L. major [pXG-CYCA-HA], for C-terminal tag, and L. major [pXG-HA-CYCA], for the N-terminal tag). The expression of both CYCA-HA (Figure 4A, lane 1) and HA-CYCA (lane 2) was detected in procyclic promastigote cell lysates at the predicted size of 35 kDa, while no HA-tagged protein was detected in wild type cells (lane 3).

Figure 4. CRK3:CYCA in L. major.

(A) Western blot of L. major promastigote cell lysates probed with anti-HA antibody. Lane 1: L. major [pXG-CYCA-HA], Lane 2: L. major [pXG-HA-CYCA], Lane 3, wild type L. major (B) Upper panel: Silver stained SDS-PAGE gel of protein eluted from anti-HA antibody affinity column. Lower panel. Western blot with anti-CRK3 antibody. Lane 1: L. major [pXG-HA-CYCA] Lane 2: wild type L. major. (C) histone H1 kinase assay with immuno-precipitated HA-CYCA Lane 1: L. major [pXG-HA-CYCA], Lane 2: wild type L. major. H1; histone H1

An immuno-precipitation (IP) of L. major and L. major [pXG-HA-CYCA] was performed using a column of conjugated anti-HA antibody (Figure 4B). The proteins immunoprecipitated from cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with silver stain. A protein corresponding to the expected size of HA tagged CYCA was immuno-precipitated from L. major [pXG-HA-CYCA] (Figure 4B upper panel, lane 1), but not wild type L. major (lane 2). CRK3 was detected with a CRK3-specific antibody in immuno-precipitates of L. major [pXG-HA-CYCA] (Figure 4B, lower panel, lane 1) but not of wild type L. major (lane 2), confirming that CRK3 interacts with CYCA in procyclic promastigotes. The precipitated material was assayed for histone H1 kinase activity. Activity was detected in immuno-precipitates from L. major [pXG-HA-CYCA] (Figure 4C, lane 1), but not from wild type L. major (lane 2). These data show that CYCA interacts with CRK3 in vivo and forms an active histone H1 kinase.

4. Discussion

The work presented here is the first to describe the production of a defined active recombinant CRK3 kinase complex and demonstrates that, although the leishmanial CDK shares some regulatory features with mammalian and yeast CDKs, there are also some important differences. In this study, soluble CRK3 was expressed in bacteria, purified and found to possess negligible histone H1 kinase activity. A putative cyclin, CYCA [4], was identified in L. mexicana and also expressed in bacteria. The purified CYCA protein was found to bind and activate CRK3 in vitro in a dose-dependent manner, with optimal kinase activity occurring when the molar ratio of kinase to cyclin was 1:1. The syntenic homologue of CYCA in L. donovani, LdCYC1, has previously been shown to bind LdCRK3 in vivo but could not activate bacterially expressed LdCRK3 in vitro [26], possibly as a result of the recombinant protein(s) being mis-folded and therefore inactive.

Previously, active CRK3 enzyme was purified from leishmanial lysates [33], but the complex was uncharacterised in terms of the cyclin partner(s) and the phosphorylation status of the kinase subunit. The ability to re-constitute active kinase complex entirely from bacterially expressed protein ensures that the enzyme preparation is clearly defined, consistent and reproducible. The accurate biochemical characterisation of this complex may help to further elucidate the role(s) of CRK3 in Leishmania. Indeed it has enabled us to scrutinise the role of phosphorylation of the T-loop Thr-178 in the regulation of recombinant CRK3 protein kinase activity.

Phosphorylation of the T-loop Thr in CDK1, CDK2 and CDK4 is required for full activation [13,14] and is associated with a dramatic increase in protein kinase activity [36]. This increased activity is explained by the conformational change elicited by phosphorylation, which creates the substrate binding site and orientates ATP for phospho-transfer [15,37]. Mutation of a Thr residue to Asp or Glu is thought to mimic phosphorylation at this site. In cAMP-dependent kinase, phosphorylation of a Thr in the catalytic subunit is essential for the formation of the hetero-tetrameric complex. Mutation of this Thr to either Asp or Glu mimics the presence of the phospho-threonine and allows the association of the subunits. This effect is specific for the acidic amino acids; mutation to any other residue abolishes complex formation [30]. There is some evidence that this approach can be used to mimic T-loop phosphorylation in CDKs. Mutation of the T-loop residue in Schizosaccharomyces pombe cdc2 (CDK1) to Glu results in a phenotype in vivo that is consistent with constitutive activation of this CDK; deregulated mitosis and premature cytokinesis [38]. Replacement of the T-loop Thr with Glu in the Plasmodium falciparum CDK, PfPK5, results in a 5-10-fold increase in kinase activity [31,32]. Mutation of the T-loop residue of CRK3 to Glu (CRK3T178E), however, did not activate the enzyme; instead it abolished protein kinase activity in the presence of CYCA. Although this was unexpected, it is consistent with what is observed for Saccharomyces cerevisiae CDC28; Mutation of the T-loop Thr to Glu inhibits both kinase activity and biological function, although second suppressor site mutations can generate T169E mutants with partially recovered biological activity [39]. On its own, Glu cannot fully complement for the phospho-threonine in CDC28. Moreover, mutation of the T-loop Thr abolishes catalytic activity in CDK1 and CDK2: in CDK1 mutation to Val abolishes cyclin-binding and kinase activity [38] and in CDK2 mutation to Ala abolishes activity of bacterially-expressed protein [40]. Leishmania CRK3 has an additional Thr residue (T176) close to the T-loop T178, which might also be a site of phosphorylation (Figure 3A). T176 is conserved in human CDK1 and CDK2, but not in S. cerevisiae CDC28. To our knowledge, this residue has not been identified as a site of phosphorylation in CDK proteins of other eukaryotes, but it could potentially be an additional site of regulation for T-loop function in Leishmania. Since this approach to mimic T-loop phosphorylation was unsuccessful and because the leishmanial CAK has not yet been identified, we further explored the requirement for CRK3 to be phosphorylated on its T-loop using the S. cerevisiae monomeric CAK, Civ1 [18].

The natural substrate for Civ1 is CDC28 but Civ1 can also phosphorylate and activate most mammalian CDKs in vitro [20,24]. Civ1 could phosphorylate wild type CRK3 in vitro but not CRK3T178E, indicating that T178 is likely to be the phosphorylation site in CRK3, as predicted. Pre-incubation of the CRK3:CYCA complex with Civ1 resulted in phosphorylation of the kinase subunit and a 5-fold increase in its histone H1 kinase activity. Compared to the 80-100-fold increase observed for CDK1 and CDK2 [36], this is a fairly modest stimulation of activity. Possible reasons for this include: In the experimental conditions used, Civ1 may not be able to fully phosphorylate CRK3 because (a) the conditions are sub-optimal; the conditions used were those optimised for the subsequent phosphorylation of histone H1 by the CRK3 complex, (b) the sequence of the T-loop is only partially conserved (Fig 3A, CRK3 72% identical to CDC28) and CRK3 is an inefficient substrate for Civ1 or (c) because Civ1 prefers CDK monomer as its substrate and may not have been able to efficiently phosphorylate the CRK3:CYCA complex. Indeed, it is known that Civ1 phosphorylates monomer CDK2 much more efficiently than CDK2/cyclin A complexes [20] and the intensity of the phosphorylated CRK3 (CRK3 monomer in Fig 2A) appears greater than when Civ1 was pre-incubated with CRK3:CYCA complex (Fig 2B). Future experiments will test the relative efficiency of CRK3 phosphorylation and activation when CRK3 is pre-incubated with Civ1 and then allowed to associate with CYCA.

However, the modest increase in CRK3 kinase activity upon phosphorylation by Civ1 may simply reflect the fact that T-loop phosphorylation is less important in the regulation of CRK3 activity than it is for CDK1, CDK2 and CDK4. Not all protein kinases are activated through phosphorylation of their T-loop; those that are include CDKs, MAPKs and cAPK. Immediately adjacent to the conserved aspartate residue within their catalytic domain, these protein kinases invariably have an arginine residue (RD kinases). Whilst all protein kinases that are activated by phosphorylation of their T-loop possess this RD motif, the reciprocal is not true; not all RD kinases require T-loop phosphorylation for activation. CRK3 does possess this RD motif but it may fall into the latter category, along with CDK5 and CDK6, whose activity appears to be independent of their T-loop phosphorylation status [16]. Protein kinases that do not utilise T-loop phosphorylation can adopt an active conformation without this post-translational modification [41]. CRK3 appears to lie somewhere between these two extremes: it is active in the absence of T-loop phosphorylation but its activity is further stimulated upon phosphorylation of its T-loop, albeit to a much lesser extent than observed with CDK1, CDK2 and CDK4.

In some cases, T-loop phosphorylation is required for CDK/cyclin complex formation: T-loop phosphorylation is a pre-requisite for CDK1/cyclin B complex formation in vivo but CDK2 can form complexes with cyclins in the absence of T-loop phosphorylation [13]. CRK3 appears to be more like CDK2 in this regard since CRK3 can form active complexes with CYCA in the absence of phosphorylation of T178. However, based upon current results, it cannot be ruled out that phosphorylation of CRK3 before incubation with CYCA would increase the efficiency of complex formation and the observed kinase activity.

In a recent analysis of the phosphoproteome of bloodstream form T. brucei, CRK3 was found to be phosphorylated on T33 and Y34, sites that correspond to human CDK1 T14 and Y15 [42,43]. In humans phosphorylation of Y15 by the wee1 kinase is a negative regulator of protein kinase activity [44] and the presence of wee1 in both the trypanosome and Leishmania genomes would suggest that CRK3 is regulated by a similar mechanism. In contrast, no phosphorylation was detected on T-loop threonine residue of T. brucei CRK3 [42] and no CAK-like protein kinases have been identified in either the trypanosome or Leishmania genomes [4,5]. Whilst the lack of detection of a T178 CRK3 phosphopeptide does not rule out its presence in the cell, it is possible that the trypanosomatids have evolved alternative mechanisms to positively regulate CRK3 activity.

In contrast to the phosphorylation and activation of CRK3 by Civ1, none of the other leishmanial CRKs could be phosphorylated by Civ1 in vitro. This may simply reflect the fact that the sequence similarity across the T-loop between these CRKs and the natural Civ1 substrate is lower than for CRK3. However, none of these CRKs displayed any histone H1 kinase activity as monomers either. As the CRKs are likely to be cyclin-dependent [4,5], these are likely to have to bind their cognate cyclin partners and possibly also be phosphorylated by the leishmanial CAK before they can form an active kinase. Future work will strive to identify the cyclin partners for the remaining leishmanial CRKs.

In summary, this work reports that the leishmanial CDK, CRK3, can associate with and be activated by the cyclin, CYCA; that the T-loop Thr-178 residue is essential for kinase activity in vitro and that phosphorylation of T178 by the yeast CAK, Civ1, can further increase kinase activity, in an analogous fashion to mammalian CDKs, albeit to a much lesser degree than mammalian CDKs. These results demonstrate that the way in which CDK activity is controlled in other eukaryotes is conserved in Leishmania but that there may be significant differences in the relative importance of the different regulatory mechanisms in the parasite.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Jane Endicott for the Civ1-GST construct. This work was funded by the Medical Research Council [grant numbers G9722968 and G0400028]. FG was a recipient of a Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Passoal de Nivel Superior (CAPES) Fellowship from the Brazilian Government.

References

- 1.Mottram JC, Grant KM. Leishmania mexicana p12cks1, a functional homologue of fission yeast p13suc1, associates with a stage-regulated histone H1 kinase. Biochem J. 1996;316:833–839. doi: 10.1042/bj3160833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant KM, Hassan P, Anderson JS, Mottram JC. The crk3 gene of Leishmania mexicana encodes a stage-regulated cdc2-related histone H1 kinase that associates with p12cks1. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10153–10159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siman-Tov MM, Ivens AC, Jaffe CL. Identification and cloning of Lmairk, a member of the Aurora/Ipllp protein kinase family, from the human protozoan parasite Leishmania. Biochim Biophys Acta: Gene Struct Expr. 2001;1519:241–245. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(01)00240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naula C, Parsons M, Mottram JC. Protein kinases as drug targets in trypanosomes and Leishmania. Biochim Biophys Acta: Prot proteom. 2005;1754:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parsons M, Worthey EA, Ward PN, Mottram JC. Comparative analysis of the kinomes of three pathogenic trypanosomatids; Leishmania major, Trypanosoma brucei and Trypanosoma cruzi. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:127. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mottram JC, McCready BP, Brown KP, Grant KM. Gene disruptions indicate an essential function for the LmmCRK1 cdc2-related kinase of Leishmania mexicana. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:573–582. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hassan P, Fergusson D, Grant KM, Mottram JC. The CRK3 protein kinase is essential for cell cycle progression of Leishmania mexicana. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2001;113:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(01)00220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Mammalian cyclin-dependent kinases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:630–641. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fung TK, Poon RY. A roller coaster ride with the mitotic cyclins. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parker LL, Piwinica-Worms H. Inactivation of the p34(cdc2)-cyclin-b complex by the human WEE1 tyrosine kinase. Science. 1992;257:1955–1957. doi: 10.1126/science.1384126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mueller PR, Coleman TR, Kumagai A, Dunphy WG. Myt1: A membrane-associated inhibitory kinase that phosphorylates Cdc2 on both threonine-14 and tyrosine-15. Science. 1995;270:86–90. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5233.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nilsson I, Hoffmann I. Cell cycle regulation by the Cdc25 phosphatase family. Prog Cell Cycle Res. 2000;4:107–114. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4253-7_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larochelle S, Merrick KA, Terret ME, Wohlbold L, Barboza NM, Zhang C, Shokat KM, Jallepalli PV, Fisher RP. Requirements for Cdk7 in the assembly of Cdk1/cyclin B and activation of Cdk2 revealed by chemical genetics in human cells. Mol Cell. 2007;25:839–850. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kato J-Y, Matsuoka M, Strom DK, Sherr CJ. Regulation of cyclin D-dependent kinase 4 (cdk4) by cdk4- activating kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2713–2721. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartova I, Otyepka M, Kriz Z, Koca J. Activation and inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase-2 by phosphorylation; a molecular dynamics study reveals the functional importance of the glycine-rich loop. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1449–1457. doi: 10.1110/ps.03578504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bockstaele L, Bisteau X, Paternot S, Roger PP. Differential regulation of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) and CDK6, evidence that CDK4 might not be activated by CDK7, and design of a CDK6 activating mutation. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:4188–4200. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01823-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devault A, Martinez AM, Fesquet D, Labbé JC, Morin N, Tassan JP, Nigg EA, Cavadore JC, Dorée M. MAT1 (‘menage a trois’) a new RING finger protein subunit stabilizing cyclin H-cdk7 complexes in starfish and Xenopus CAK. EMBO J. 1995;14:5027–5036. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00185.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thuret JY, Valay JG, Faye G, Mann C. Civ1 (CAK in vivo), a novel Cdk-activating kinase. Cell. 1996;86:565–576. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaldis P, Pitluk ZW, Bany IA, Enke DA, Wagner M, Winter E, Solomon MJ. Localization and regulation of the cdk-activating kinase (Cak1p) from budding yeast. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:3585–3596. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.24.3585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaldis P, Russo AA, Chou HS, Pavletich NP, Solomon MJ. Human and yeast Cdk-activating kinases (CAKs) display distinct substrate specificities. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2545–2560. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.9.2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fesquet D, Labbé J-C, Derancourt J, Capony J-P, Galas S, Girard F, Lorca T, Shuttleworth J, Dorée M, Cavadore J-C. The MO15 gene encodes the catalytic subunit of a protein kinase that activates cdc2 and other cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) through phosphorylation of Thr161 and its homologues. EMBO J. 1993;12:3111–3121. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05980.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aprelikova O, Xiong Y, Liu ET. Both p16 and p21 families of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors block the phosphorylation of cyclin-dependent kinases by the CDK-activating kinase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18195–18197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.31.18195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foley E, O'Farrell PH, Sprenger F. Rux is a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitory (CKI) specific for mitotic cyclin-Cdk complexes. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1392–1402. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)80084-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown NR, Noble ME, Lawrie AM, Morris MC, Tunnah P, Divita G, Johnson LN, Endicott JA. Effects of phosphorylation of threonine 160 on cyclin-dependent kinase 2 structure and activity. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8746–8756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang YX, Dimitrov K, Garrity LK, Sazer S, Beverley SM. Stage-specific activity of the Leishmania major CRK3 kinase and functional rescue of a Schizosaccharomyces pombe cdc2 mutant. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;96:139–150. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banerjee S, Sen A, Das P, Saha P. Leishmania donovani cyclin 1 (LdCyc1) forms a complex with cell cycle kinase subunit CRK3 (LdCRK3) and is possibly involved in S-phase-related activities. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;256:75–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Besteiro S, Tonn D, Tetley L, Coombs GH, Mottram JC. The AP3 adaptor is involved in the transport of membrane proteins to acidocalcisomes of Leishmania. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:561–570. doi: 10.1242/jcs.022574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LeBowitz JH, Coburn CM, McMahon-Pratt D, Beverley SM. Development of a stable Leishmania expression vector and application to the study of parasite surface-antigen genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9736–9740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson KA, Beverley SM. Improvements in transfection efficiency and tests of RNA interference (RNAi) approaches in the protozoan parasite Leishmania. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;128:217–228. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(03)00079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaldis P. The cdk-activating kinase (CAK): from yeast to mammals. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55:284–296. doi: 10.1007/s000180050290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levin LR, Zoller MJ. Association of catalytic and regulatory subunits of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase requires a negatively charged side group at a conserved threonine. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:1066–1075. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.3.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Graeser R, Franklin RM, Kappes B. Mechanism of activation of the cdc2-related kinase PfPK5 from Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;79:125–127. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02643-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grant KM, Dunion MH, Yardley V, Skaltsounis A-L, Marko D, Eisenbrand G, Croft SL, Meijer L, Mottram JC. Inhibitors of Leishmania mexicana CRK3 cyclin-dependent kinase: chemical library screen and antileishmanial activity. Antimicrob Agents Chem. 2004;48:3033–3042. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.8.3033-3042.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Losiewicz MD, Carlson BA, Kaur G, Sausville EA, Worland PJ. Potent inhibition of CDC2 kinase activity by the flavonoid L86-8275. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;201:589–595. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoessel R, Leclerc S, Endicott JA, Nobel MEM, Lawrie A, Tunnah P, Leost M, Damiens E, Marie D, Marko D, Niederberger E, Tang WC, Eisenbrand G, Meijer L. Indirubin, the active constituent of a Chinese antileukaemia medicine, inhibits cyclin-dependent kinases. Nature Cell Biol. 1999;1:60–67. doi: 10.1038/9035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Connell-Crowley L, Solomon MJ, Wei N, Harper JW. Phosphorylation independent activation of human cyclin-dependent kinase 2 by cyclin A in vitro. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:79–92. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stevenson LM, Deal MS, Hagopian JC, Lew J. Activation mechanism of CDK2: role of cyclin binding versus phosphorylation. Biochemistry. 2002;41:8528–8534. doi: 10.1021/bi025812h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ducommun B, Brambilla P, Felix MA, Franza BR, Karsenti E, Draetta G. Cdc2 phosphorylation is required for its interaction with cyclin. EMBO J. 1991;10:3311–3319. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04895.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cross FR, Levine K. Molecular evolution allows bypass of the requirement for activation loop phosphorylation of the Cdc28 cyclin-dependent kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2923–2931. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abbas T, Jha S, Sherman NE, Dutta A. Autocatalytic phosphorylation of CDK2 at the activating Thr160. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:843–852. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.7.4000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nolen B, Taylor S, Ghosh G. Regulation of protein kinases; controlling activity through activation segment conformation. Mol Cell. 2004;15:661–675. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nett IR, Martin DM, Miranda-Saavedra D, Lamont D, Barber JD, Mehlert A, Ferguson MA. The phosphoproteome of bloodstream form Trypanosoma brucei, causative agent of African sleeping sickness. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:1527–1538. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800556-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nett IR, Davidson L, Lamont D, Ferguson MA. Identification and specific localization of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins in Trypanosoma brucei. Eukaryot Cell. 2009;8:617–626. doi: 10.1128/EC.00366-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morgan DO. Principles of CDK regulation. Nature. 1995;374:131–134. doi: 10.1038/374131a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.