The publication of guidelines for advanced life support by the European Resuscitation Council in 1992 was a landmark in international cooperation and coordination.1 Previously, individual countries or groups had produced guidelines,2 but for the first time an international group of experts produced consensus views based on the best available information. Since 1992 even wider international collaboration and support has occurred. In particular, the establishment of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation has facilitated global cooperation and discussion between representatives from North America, Europe, Southern Africa, Australia, and most recently Latin America. The advisory statement produced in 1997 by the committee forms the basis for these guidelines.3

The 1992 guidelines by the European Resuscitation Council indicated that review would occur on a regular basis. Change is not advocated for its own sake and is not warranted without convincing scientific or educational reasons. Education and its organisation is a process with a long latency, and it can be confusing and distracting for trainers and trainees if the message lacks consistency.

The Advanced Life Support Working Group of the European Resuscitation Council recognised that the previous guidelines necessitated a level of rhythm recognition, interpretation, and subsequent decision making that some users found difficult. While automated external defibrillators ease some of these problems, the 1992 guidelines were not specifically designed for these devices. These new guidelines are applicable to manual and automated external defibrillators. Decision making has been reduced to a minimum whenever possible. This increases clarity, while still allowing people with specialist knowledge to apply their expertise.

Changes in guidelines are only the first step in the process of care. Their implementation necessitates considerable effort. Training materials and methods may require modification, information must be disseminated, and, perhaps most importantly, evaluation of efficacy is needed. For these purposes, reporting and publication of out of hospital and in-hospital cardiac arrest events using the Utstein templates4,5 is strongly advised to provide objective assessment of outcome.

The limitations of guidelines must be recognised. As always in the practice of medicine, words and flow charts must be interpreted with common sense and an appreciation of their intent. While much is known about the theory and practice of resuscitation, in many areas our ignorance is profound. Resuscitation practice remains as much an art as a science. Furthermore, the interpretation of guidelines may differ according to the environment in which they are used. We acknowledge that individual resuscitation councils may wish to customise the details while accepting that the guiding principles are universal. Any such changes must be approved by the European Resuscitation Council if they are to be regarded by this organisation as representing its official guidelines.

Precursors to cardiac arrest

In the so called industrialised world the commonest cause of adult sudden cardiac death is ischaemic heart disease.6–9 Prevention of cardiac arrest is to be greatly preferred to post hoc treatment. The guidelines on the management of peri-arrest arrhythmias produced by the European Resuscitation Council in 1994 and updated in 1996 and 1998 are concerned with treating arrhythmias that may lead to the development and recurrence of cardiac arrest in critical situations.10

Small, but important, subgroups of patients sustain cardiac arrest in certain special circumstances other than ischaemic heart disease. These include trauma, drug overdose, hypothermia, immersion, anaphylaxis, pregnancy, hypovolaemia. While this European Resuscitation Council algorithm is universally applicable, specific modifications may be required to maximise the likelihood of success in these circumstances.

Specific interventions and their use in the algorithm

Defibrillation

In adults the commonest primary arrhythmia at the onset of cardiac arrest is ventricular fibrillation (VF) or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT).11–14 The overwhelming majority of eventual survivors come from this group.15–18 If the definitive treatment for these arrhythmias—defibrillation—can be implemented promptly a perfusing cardiac rhythm may be restored and lead to long term survival. The only interventions that have been shown unequivocally to improve long term survival are basic life support and defibrillation. VF is a readily treatable rhythm, but the chances of successful defibrillation decline substantially with the passage of each minute.19,20 The amplitude and waveform of VF deteriorate rapidly, reflecting the depletion of myocardial high energy phosphate stores.21,22 The rate of decline in success depends partly on the provision and adequacy of basic life support.23 As a result, the priority is to minimise any delay between the onset of cardiac arrest and the administration of defibrillating shocks.

At present, the most commonly used transthoracic defibrillation waveform has a damped sinusoidal pattern. Newer techniques such as biphasic waveforms and sequentially overlapping shocks producing a rapidly shifting electrical vector during a multi-pulse shock may reduce the energy requirements for successful defibrillation.24–26 Automated defibrillators that can deliver a current based shock appropriate to the measured transthoracic impedance are available and are being evaluated. Their use may increase the efficacy of individual shocks while reducing myocardial injury in patients with unusually high or low transthoracic impedance.27,28

The use of groups of three shocks is retained, the initial sequence having energies of 200 J, 200 J, and 360 J. The reasons for choosing 200 J as the energy for the first two shocks of conventional waveform defibrillation have been presented.29 Subsequent shocks, if required, should have energies of 360 J. If a coordinated rhythm has supervened for a limited interval, there is no strong scientific basis for deciding whether to revert to 200 J or continue at 360 J. There is evidence that myocardial injury, both functionally and morphologically, is greater with increasing energies, but the comparative success rates for defibrillation attempts at this point with 200 J v 360 J are unknown. Both strategies are therefore acceptable. Most automated external defibrillators have an algorithm that does not revert to 200 J after a short period of non-VF/VT. In this case, defibrillation should continue with 360 J instead of restarting the automated external defibrillator to allow a 200 J shock to be given. Alternative waveforms and energy levels are acceptable if shown to be of equal or greater net clinical benefit in terms of safety and efficacy.

A pulse check is required after a shock (and should be prompted by an automated external defibrillator) only if the waveform changes to one compatible with cardiac output. Thus if VF, or VT with an identical waveform, persists after the first 200 J shock, the second shock at 200 J is given without checking the pulse. If, in turn, this shock is unsuccessful, the third shock—this time at 360 J—is given. With modern defibrillators, charging times are sufficiently short for three shocks to be given within one minute.

Only a small proportion of the delivered electrical energy traverses the myocardium during transthoracic defibrillation30 and efforts to maximise this proportion are important. The commonest defects are inadequate contact with the chest wall, failure or poor use of couplants to aid the passage of current at the interface between the paddles and the chest wall, and faulty positioning or size of paddles.31–34 One paddle should be placed below the right clavicle in the mid-clavicular line and the other over the lower left ribs in the mid-anterior axillary line (just outside the position of the normal cardiac apex). In female patients the second pad or paddle should be placed firmly on the chest wall just outside the position of the normal cardiac apex, avoiding the breast tissue.35

If unsuccessful, other positions such as apex posterior may be considered.36,37 Although the polarity of the electrodes affects success with internal techniques such as implantable defibrillators, during transthoracic defibrillation the polarity of the paddles seems unimportant.38–40

Airway management and ventilation

In 1996 guidelines for the advanced management of the airway and ventilation during resuscitation were published by a working group of the European Resuscitation Council.41 These guidelines outline basic and advanced approaches to airway management together with their separate indications, contraindications, and descriptions of the procedures. Further reviews were published in 1997.42,43

While recognising that tracheal intubation remains the optimal procedure, these guidelines acknowledge that the technique can be difficult and sometimes hazardous and that regular experience and refresher training are required. The laryngeal mask airway offers an alternative to tracheal intubation, and although it does not guarantee absolutely against aspiration, the incidence in reported series is low.44,45 The pharyngotracheal lumen airway and the oesophageal-tracheal Combitube are alternatives but require more training and have their own specific problems in use.41

During cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation lung characteristics change because of an increase in dead space while the development of pulmonary oedema reduces lung compliance.46,47 Oxygenation of the patient is the primary objective of ventilation and the aim should be to provide inspired oxygen concentrations (FiO2) of 1.0. Carbon dioxide production and delivery to the lungs are limited during the initial period of cardiac arrest. Tidal volumes of 400-600 ml are adequate to make the chest rise.48 Adequate minute ventilation is necessary to facilitate carbon dioxide elimination and prevent the potential development of hypercarbic acidosis after the administration of carbon dioxide producing buffers such as sodium bicarbonate.

Ventilation techniques vary from simple bag valve devices to the most sophisticated automatic ventilators which can provide an FiO2 of 1.0, consistent tidal volumes and inspiratory flow rates, and respiratory frequencies that are adjustable on demand.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation techniques

The only change recommended in the technique of closed chest compression is that the rate should be 100/minute. There have been and are ongoing trials of new techniques, most notably with active compression-decompression cardiopulmonary resuscitation, but there are at present no clinical data showing unequivocal improvement in outcomes.49–52 To improve the scientific basis for future recommendations, the use of new techniques should be carefully evaluated by clinical trials before implementation into prehospital and in-hospital practice.

Drug delivery

The venous route remains the optimal method of drug administration during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The previous guidance with regard to venous cannulation is unchanged.53 If already in situ, central venous cannulae can deliver agents rapidly to the central circulation. If a central line is not present, the risks associated with the technique—which can themselves be life threatening—mean that for an individual patient the decision as to peripheral v central cannulation will depend on the skill of the operator, the nature of the surrounding events, and available equipment. If a decision is made to attempt central venous cannulation, this must not delay defibrillation attempts, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or airway security. When peripheral venous cannulation and drug delivery is performed, a flush of 20 ml of 0.9% saline is advised to expedite entry to the circulation.

The administration of drugs through a tracheal tube remains only a second line approach because of impaired absorption and unpredictable pharmacodynamics. The agents which can be given by this route are limited to adrenaline/epinephrine, lignocaine/lidocaine, and atropine. Doses of 2-3 times the standard intravenous dose diluted up to a total volume of at least 10 ml of 0.9% saline are currently recommended. After administration, five ventilations are given to increase dispersion to the distal bronchial tree, thus maximising absorption.

Specific drug treatment

Vasopressors

Experimentally adrenaline/epinephrine improves myocardial and cerebral blood flow and resuscitation rates in animals, and higher doses are more effective than the “standard” dose of 1 mg.54,55 There is no clinical evidence that adrenaline/epinephrine improves survival or neurological recovery in humans irrespective of whether a standard or high dose is used.56,57 Some clinical trials have reported slightly increased rates of return of spontaneous circulation with high doses of adrenaline/epinephrine but without improvement in overall survival rate.58–62 The reasons for the difference between experimental and clinical results are likely to reflect differences in underlying pathology and the relatively long periods of arrest before the advanced life support team is able to give adrenaline/epinephrine outside hospital. It is also possible that higher doses of adrenaline/epinephrine may be detrimental in the post-resuscitation period.63,64 Pending definitive placebo controlled trials the indications, dosage, and time interval between doses for adrenaline/epinephrine are unchanged. In practical terms for non-VF/VT rhythms each loop of the algorithm lasts 3 minutes and therefore adrenaline/epinephrine is given with every loop. For VF/VT rhythms the process of rhythm assessment, three defibrillatory shocks, followed by one minute of cardiopulmonary resuscitation will take 2-3 minutes. Thus, adrenaline/epinephrine could generally be given with each loop if precise timing of administration is impracticable.

Considerable caution should be used before routinely administering adrenaline/epinephrine to patients whose arrest is associated with solvent abuse, cocaine, and other sympathomimetic drugs.65–68

The evidence with regard to other adrenergic and non-adrenergic vasopressors is limited. Experimentally, vasopressin leads to significantly higher coronary perfusion pressures and preliminary data in relation to return of spontaneous circulation rates may be encouraging,69,70 but at present, no pressor agent other than adrenaline/epinephrine can be recommended.

Antiarrhythmic agents

There is incomplete evidence to make firm recommendations on the use of any anti-arrhythmic agent, although our knowledge of lignocaine/lidocaine is greater than for the others. Early studies suggested that lignocane/lidocaine increased the ventricular defibrillation threshold in animals,71–74 but this may have been influenced by experimental techniques.75 In humans the administration of lignocaine/lidocaine before defibrillation may not increase the energy requirements for defibrillation.76,77 In one randomised placebo controlled trial there was a beneficial effect on the threshold in the special circumstance of patients undergoing myocardial reperfusion after coronary artery bypass grafting.78

For these reasons and pending the results of trials, it is recommended that no change is made in the previous recommendations with regard to lignocaine/lidocaine, bretylium, and other antiarrhythmic agents.79

Atropine has a well established role in the treatment of haemodynamically compromising bradyarrhythmias and some forms of heart block.10 It was advocated for asystole in the 1992 guidelines on the basis that increased vagal tone could contribute to the development or unresponsiveness of this arrhythmia. Evidence of value in this condition is equivocal and limited to small series and case reports.80–83 Since any adverse effect is unlikely in this situation its use can still be considered in a single dose of 3 mg intravenously. This dose is known to be sufficient to block vagal activity effectively in fit adults with a cardiac output.84

Buffer agents

In previously healthy people arterial blood gas analysis does not show a rapid or severe development of acidosis during cardiorespiratory arrest provided that effective basic life support is performed.85–87 Simply measuring arterial (or even mixed venous blood) gas tensions may, however, be misleading and bear little relation to the internal milieu of myocardial or cerebral intracellular values.88–92

With this background, the role of buffers in cardiopulmonary resuscitation is still uncertain. Much of the evidence against the routine use of bicarbonate is based on animal studies and may have limited applicability to humans as the doses of bicarbonate used have often been high.93–95 One prospective randomised controlled trial has been reported on the use of buffers in patients with out of hospital cardiac arrest.96 The buffer used was Tribonat (a mixture of sodium bicarbonate, trometamol, disodium phosphate, and acetate). There was no improvement in hospital admission or discharge rates. In this study the time between ambulance dispatch and response was short and the confidence interval of the odds ratio was wide.97

Pending further studies, it is suggested that the judicious use of buffers is limited to severe acidosis as defined in the previous guidelines (arterial pH <7.1 and base excess <−10) and to certain special situations, such as cardiac arrest associated with hyperkalaemia or after tricyclic antidepressant overdose. For sodium bicarbonate, a dose of 50 mmol (50 ml of an 8.4% solution) is appropriate, with further administration dependent on the clinical situation and the results of repeat arterial blood gas analysis.

Using the universal algorithm

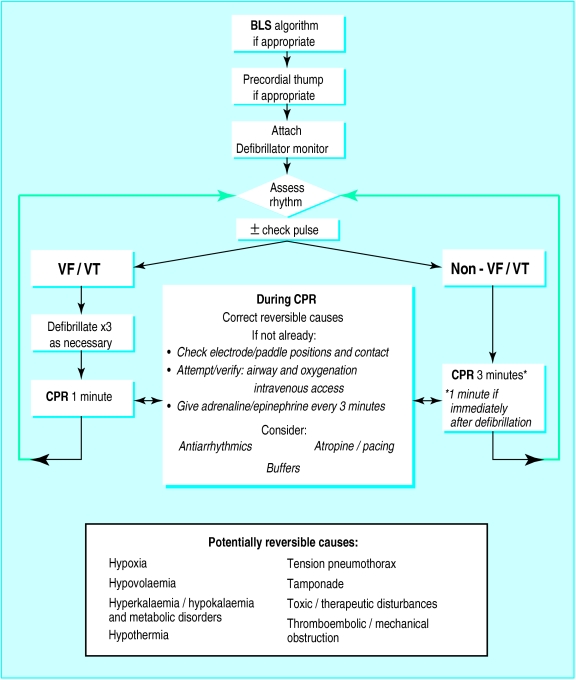

Each step that follows in the advanced life support algorithm (figure) assumes that the preceding one has been unsuccessful.

A precordial thump may, in certain situations such as a witnessed event, precede (albeit by a few seconds only) the attachment of a monitor/defibrillator.98,99

Electrocardiographic monitoring then provides the link between basic and advanced life support procedures. Electrocardiographic rhythm assessment must be always interpreted within the clinical context as movement artefact, lead disconnection, and electrical interference can mimic rhythms associated with cardiac arrest.

Following this assessment, the algorithm splits into two pathways—VF/VT and other rhythms.

VF/VT rhythms

The first defibrillating shock must be given without any delay. If unsuccessful it is repeated once and, if necessary, twice. This initial group of three shocks should occur with successive energies of 200 J, 200 J, and 360 J. If VF/VT persists further shocks are given at 360 J or the biphasic equivalent. A pulse check is performed and should be prompted by an automated external defibrillator if, following a defibrillating shock, a change in waveform is produced which is compatible with output. If the monitor/defibrillator indicates that VF/VT persists, then further DC shocks are administered without a further pulse check.

It is important to note that after a shock the electrocardiograph’s monitor screen will often show an isoelectric line for several seconds. This is commonly due to a transient period of electrical or myocardial “stunning,” or both, and does not necessarily mean that the rhythm has converted to asystole, as a coordinated rhythm or return of VF/VT may supervene subsequently. If the monitor screen of a manual defibrillator shows a “straight” line for more than one sweep immediately after a shock, 1 minute of cardiopulmonary resuscitation should be given without a new dose of adrenaline/epinephrine and the patient reassessed. Only if the result of this reassessment is a non-VF/VT rhythm without a pulse should a new dose of adrenaline/epinephrine be administered and cardiopulmonary resuscitation given for a further two minutes before the patient is assessed again. Algorithms of automated external defibrillators should also take account of this phenomenon.

Emphasis must be placed on the correct performance of defibrillation, including the use of couplants. The safety of the resuscitation team is paramount. During defibrillation, no one must be in contact with the patient. Liquids, wet clothing, and spreading of excess electrode gel may cause problems. Transdermal patches should be removed to prevent the possibility of electrical arcing.100 Paddles or pads should be kept 12-15 cm away from implanted pacemakers. During manual defibrillation the operator must give a command such as “Stand clear!” and check that this is obeyed before the shock is given. With automated systems an audio command is given, and all team members must comply with this command.

Over 80% of people in whom defibrillation will be successful have this achieved by one of the first three shocks.17,19,20,101 Subsequently, the best prospects for restoring a perfusing rhythm still remain with defibrillation, but at this stage the search for and correction of potentially reversible causes or aggravating factors is indicated, together with an opportunity to maintain myocardial and cerebral viability with chest compressions and ventilation. During cardiopulmonary resuscitation attempts can be made to institute advanced airway management and ventilation, achieve venous access, and administer drugs if appropriate to do so.

The time interval between the third and fourth shocks should not exceed two minutes. Although the interventions which can be performed during this period may improve the prospects for successful defibrillation, this is unproved, while it is well established that with the passage of time the chances of success for defibrillating shocks lessen.

“Looping” the algorithm

For patients with persistent VF/VT potential causes or aggravating factors may include electrolyte imbalance, hypothermia, and drugs and toxic agents for which specific treatment may be indicated. When it is appropriate to continue resuscitation, successive loops of the algorithm are followed, allowing further sequences of shocks, basic life support, and the ability to perform and secure advanced airway and ventilation techniques, oxygenation, and drug delivery. Antiarrhythmic drugs may be considered after the first two sets of three shocks, although maintaining the previous policy of deferring this treatment until four sets would be acceptable.

Non-VF/VT rhythms

If VF/VT can be positively excluded, defibrillation is not indicated as a primary intervention (although it may be required later if ventricular fibrillation develops), and the right sided path of the algorithm is followed.

For patients in cardiac arrest with non-VF/VT rhythms, the prognosis is in general much less favourable. The overall survival rate with these rhythms is about 10-15% of the survival rate with VF/VT rhythms, but the possibility of survival should not be disregarded. In some series about 20% of eventual survivors present with a non-VF/VT rhythm.102–105

With the passage of time, all electrical rhythms associated with cardiac arrest deteriorate with the eventual production of asystole. The abysmal prognosis of this degenerated rhythm is well justified. There are, nevertheless, some situations in which a non-VF/VT rhythm may be caused or aggravated by remediable conditions, especially if this was the primary rhythm. As a consequence the detection and treatment of reversible causes become relatively more important.

During the search for and correction of these causes, cardiopulmonary resuscitation together with advanced airway management, oxygenation and ventilation, and any necessary attempts to secure venous access should occur, with adrenaline/epinephrine administered every 3 minutes.

The use of atropine for asystole has been discussed above. Intravenous atropine 3 mg is given once, along with adrenaline/epinephrine 1 mg for asystole on the first loop. Pacing may play a valuable part in patients with extreme bradyarrhythmias, but its value in asystole is questionable, except in cases of trifascicular block where P waves are seen. In patients in whom pacing is to be performed but a delay occurs before it can be achieved, external cardiac percussion (known as “fist” or “thump” pacing) may generate QRS complexes with an effective cardiac output, particularly when myocardial contractility is not critically compromised.106–108 External cardiac percussion is performed with blows at a rate of 100/minute, given with less force than a precordial thump and delivered over the heart, not the sternum. Conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation should be substituted immediately if QRS complexes with a discernible output are not being achieved.

After 3 minutes of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, the patient’s electrical rhythm is reassessed. If VF/VT has supervened the left sided path of the algorithm is followed, otherwise loops of the right sided path of the algorithm will continue for as long as it is considered appropriate for resuscitation to continue. Resuscitation should generally continue for at least 20-30 minutes from the time of collapse unless there are overwhelming reasons to believe that resuscitation is likely to be futile.

Post-resuscitation care

There are no changes in the recommendations for post-resuscitation care. The most vulnerable organ for the ischaemic-hypoxic damage occurring in association with cardiac arrest is the central nervous system. Around a third of the patients who have return of spontaneous circulation die a neurologic death, with a third of long term survivors having recognisable motor or cognitive deficits.109–111 Fortunately only 1-2% of these patients do not achieve an independent existence.112

Intensive research efforts are rapidly increasing our knowledge about the pathophysiology of ischaemia-hypoxia of the central nervous system, but there are no new clinically validated treatment strategies for the cerebral damage sustained with cardiac arrest. Efforts should be directed to the avoidance and correction of hypotension, hypoxia, hypercarbia, electrolyte imbalance, and hypoglycaemia or hyperglycaemia.113–116

Many victims of cardiac arrest have features indicating that the event was precipitated by acute myocardial infarction.117 In these patients there is an urgent need for appropriate management, including such aspects as thrombolysis or other methods for obtaining coronary reperfusion and maintaining electrical stability, to reduce the chances of further episodes of cardiac arrest and to improve the overall prognosis. These aspects are covered by the publications on the management of acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology and the ESC/ERC Task Force on the Prehospital Management of Myocardial Infarction.118–120

Figure.

Algorithm for adult advanced life support. BLS=basic life support, VF=ventricular fibrillation, VT=pulseless ventricular tachycardia, CPR=cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Acknowledgments

Members of the Advanced Life Support Working Group of the European Resuscitation Council are: Colin Robertson (United Kingdom), Petter Steen (Norway), Jennifer Adgey (United Kingdom), Peter Baskett (United Kingdom), Leo Bossaert (Belgium), Pierre Carli (France), Douglas Chamberlain (United Kingdom), Wolfgang Dick (Germany), Lars Ekstrom (Sweden), Svein A Hapnes (Norway), Stig Holmberg (Sweden), Rudolph Juchems (Germany), Fulvio Kette (Italy), Rudy Koster (Netherlands), Francisco J de Latorre (Spain), Karl Lindner (Austria), and Narcisco Perales (Spain). The working party also received contributions from Raoul Alasino (Council for Latin American Resuscitation), Vic Callanan (Australian Resuscitation Council), Brian Connolly (Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada), Richard Cummins (American Heart Association), and Walter Kloeck (Resuscitation Council Southern Africa).

Editorial by Nolan. These guidelines have been published in Resuscitation, the official journal of the European Resuscitation Council (Resuscitation 1998;37:81-90). Members of the working group are listed at the end of the article

References

- 1.Guidelines for advanced life support. A statement by the advanced life support working party of the European Resuscitation Council, 1992. Resuscitation. 1992;24:111–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Standards and guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and emergency cardiac care (ECC) JAMA. 1986;255:2905–2989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ALS Working Group of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. The universal algorithm. Resuscitation. 1997;34:109–111. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(97)01100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chamberlain DA, Cummins RO, Eisenberg M (Task Force Cochairmen). Resuscitation. Recommended guidelines for uniform reporting of data from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: the Utstein style. Resuscitation 1991;22:1-26. [PubMed]

- 5.Cummins RO, Chamberlain DA, Hazinski MF, Nadkarni V, Kloeck W, Kramer E, et al. Recommended guidelines for uniform reporting of data from in-hospital resuscitation: the in-hospital “Utstein style.”. Resuscitation. 1997;34:151–183. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(97)01112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spain D, Bradess V, Mohr C. Coronary atherosclerosis as a cause of unexpected and unexplained death. JAMA. 1960;174:384–388. doi: 10.1001/jama.1960.03030040038010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schatzkin A, Cupples LA, Fisher R, Heeren T, Morelock S, Mucatel M, et al. The epidemiology of sudden unexpected death: risk factors for men and women in the Framingham heart study. Am Heart J. 1984;107:1300–1306. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(84)90302-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmes DR, Davis K, Gersh BJ, Mock MB, Pettinger MB. Risk factor profiles of patients with sudden cardiac death and death from other cardiac causes: a report from the coronary artery surgery study (CASS) J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;13:524–530. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90587-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myerburg RJ, Kessler KM, Bassett AL, Castellanos A. A biological approach to sudden cardiac death: structure, function and cause. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63:1512–1516. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chamberlain D. Periarrest arrhythmias. Br J Anaesth. 1997;79:198–202. doi: 10.1093/bja/79.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Surawicz B. Ventricular fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;5:438–548. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(85)80526-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sedgewick ML, Dalziel K, Watson J, Carrington DJ, Cobbe SM. The causative rhythm in out-of-hospital cardiac arrests witnessed by the emergency medical services in the Heartstart Scotland project. Resuscitation. 1994;27:55–59. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(94)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deluna AB, Courrel P, Leclercq JF. Ambulatory sudden cardiac death: mechanisms of production of fatal arrhythmia on the basis of data from 157 cases. Am Heart J. 1989;117:151–159. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(89)90670-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adgey AAJ, Devlin JE, Webb SW, Mulholland H. Initiation of ventricular fibrillation outside hospital in patients with acute ischaemic heart disease. Br Heart J. 1982;47:55–61. doi: 10.1136/hrt.47.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roth R, Stewart RD, Rogers K, Cannon GM. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: factors associated with survival. Ann Emerg Med. 1984;13:237–243. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(84)80470-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekstrom L, Herlitz J, Wennerblom B, Axelsson A, Bang A, Holmberg S. Survival after cardiac arrest outside hospital over a 12-year period in Gothenburg. Resuscitation. 1994;27:181–188. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tunstall-Pedoe H, Bailey L, Chamberlain DA, Masden A, Ward M, Zideman D. Survey of 3765 cardiopulmonary resuscitations in British hospitals (the BRESUS study) BMJ. 1992;304:1347–1351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6838.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tortolani AJ, Risucci DA, Rosati RJ, Dixon R. In-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: patient, arrest and resuscitation factors associated with survival. Resuscitation. 1990;20:115–128. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(90)90047-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hargarten KM, Steuven HA, Waite EM, Olson DW, Mateer JR, Aufderheide TP, et al. Prehospital experience with defibrillation of coarse ventricular fibrillation: a ten-year review. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81801-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cobbe SM, Redmond MJ, Watson JM, Hollingsworth J, Carrington DJ. “Heartstart Scotland”—initial experience of a national scheme for out of hospital defibrillation. BMJ. 1991;302:1517–1520. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6791.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neumar RW, Brown CG, Robitaille PL, Altschuld RA. Myocardial high energy phosphate metabolism during ventricular fibrillation with total circulatory arrest. Resuscitation. 1990;19:199–226. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(90)90103-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mapin DR, Brown CG, Dzuonczyk R. Frequency analysis of the human and swine electrocardiogram during ventricular fibrillation. Resuscitation. 1991;22:85–91. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(91)90067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larsen MP, Eisenberg MS, Cummins RO, Hallstrom AP. Predicting survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a graphic model. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22:1652–1658. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81302-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greene HL, Dimarco JP, Kudenchuk PJ, Scheinman MM, Tang ASL, Reiter MJ, et al. Comparison of monoplasic and biplasic defibrillating pulse waveforms for transthoracic cardioversion. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:1135–1139. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80745-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bardy GH, Gliner BE, Kudenchuk PJ, Poole JE, Dolack GL, Jones GK, et al. Truncated biphasic pulses for transthoracic defibrillation. Circulation. 1995;91:1768–1774. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.6.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerber RE, Spencer KT, Kallock M, Birkett C, Smith R, Yoerger D, et al. Overlapping sequential pulses: a new waveform for transthoracic defibrillation. Circulation. 1994;89:2369–2379. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.5.2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerber RE, Kouba C, Martins JB, Kelly R, Low R, Hoyt R, et al. Advance prediction of transthoracic impedence in human defibrillation and cardioversion: importance of impedence in determining the success of low energy shocks. Circulation. 1984;70:303–308. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.70.2.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kerber RE, Martins JB, Kienzle MG, Constantin L, Olshansky B, Hopson R, et al. Energy, current and success in defibrillation and cardioversion: clinical studies using an automated, impedence-based energy adjustment method. Circulation. 1988;77:1038–1046. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.77.5.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bossaert L, Koster R. Defibrillation: methods and strategies. A statement for the Advanced Life Support Working Party of the European Resuscitation Council. Resuscitation. 1992;24:211–225. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(92)90181-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lermann BB, Deale OC. Relation between transcardiac and transthoracic current during defibrillation in humans. Circulation Res. 1990;67:1420–1426. doi: 10.1161/01.res.67.6.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adgey AAJ, Dalzell GNW. Paddle/pad placement for defibrillation in adults. Br J Intensive Care 1994;suppl:14-6.

- 32.Sirna SJ, Ferguson DW, Charbonnier F, Kerber RE. Electrical cardioversion in humans: factors affecting transthoracic impedence. Am J Cardiol. 1988;62:1048–1052. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(88)90546-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kerber RE. Electrical treatment of cardiac arrhythmias: defibrillation and cardioversion. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;27:296–301. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)80459-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alyward PE, Keiso R, Hite P, Charbonnier F, Kerber RE. Defibrillator electrode-chest wall coupling agents: influence on transthoracic impedence and shock success. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;6:682–686. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(85)80131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pagan-Carlo LA, Spencer KT, Robertson CE, Dengler A, Birkett C, Kerber RE. Transthoracic defibrillation: importance of avoiding electrode placement directly on the female breast. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:449–452. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00487-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kerber RE, Grayzel J, Kennedy J, Jensen SR. Elective cardioversion: influence of paddle electrode location and size on success rates and energy requirements. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:658–662. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198109173051202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kerber RE, Martins JB, Kelly KJ, Ferguson DW, Kouba C, Jensen SR, et al. Self-adhesive pre-applied electrode pads for defibrillation and cardioversion: experimental and clinical studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1984;3:815–820. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(84)80258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bardy GH, Ivey TD, Allen MD, Johnson G, Greene HL. Evaluation of electrode polarity on defibrillation efficacy. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63:433–437. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90314-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strickberger SD, Hummel JD, Horwood LE, Jentzer J, Daoud E, Niebauer M, et al. Effect of shock polarity on ventricular defibrillation threshold using a transvenous system. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;24:1069–1072. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90871-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weaver WD, Martin JS, Wirkus MJ, Morud S, Vincent S, Litwin PE, et al. Influence of external defibrillator electrode polarity on cardiac resuscitation. Pace. 1993;16:285–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1993.tb01578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baskett PJF, Bossaert L, Carli P, Chamberlain DA, Dick W, Nolan JP, et al. Guidelines for the advanced management of the airway and ventilation during resuscitation. A statement by the Airway and Ventilation Management Group of the ERC. Resuscitation. 1996;31:201–230. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(96)00976-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gabbott DA, Baskett PJF. Management of the airway and ventilation during resuscitation. Br J Anaesth. 1997;79:159–171. doi: 10.1093/bja/79.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nolan JP, Parr MJA. Aspects of resuscitation in trauma. Br J Anaesth. 1997;79:226–240. doi: 10.1093/bja/79.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brimacombe JR, Berry A. The incidence of aspiration associated with the laryngeal mask airway: a meta-analysis of published literature. J Clin Anaesth. 1995;7:297–305. doi: 10.1016/0952-8180(95)00026-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Owens TM, Robertson P, Twomey C, Doyle M, McDonald N, McShane AJ. The incidence of gastro-esophageal reflux with the laryngeal mask. Anesth Analg. 1995;80:980–984. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199505000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davis K, Johannigman JA, Johnson RC, Branson RD. Lung compliance following cardiac arrest. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:874–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1995.tb03100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ornato JP, Bryson BL, Donovan PJ. Measurement of ventilation during CPR. Crit Care Med. 1983;11:79–82. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198302000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baskett PJF, Nolan J, Parr MJA. Tidal volumes which are perceived to be adequate for resuscitation. Resuscitation. 1996;31:231–234. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(96)00994-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen TJ, Tucker KJ, Lurie KG, Redberg RF, Chin MC, Dutton JP, et al. Active compression-decompression. A new method of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. JAMA. 1992;267:2916–2923. doi: 10.1001/jama.267.21.2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwab TM, Callaham ML, Madsen CD, Utecht TA. A randomised clinical trial of active compression-decompression CPR vs. standard CPR in out of hospital cardiac arrest in two cities. JAMA. 1995;273:1261–1268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steill IG, Hebert PC, Wells GA, Laupacis A, Vandmleen K, Dreyer JF, et al. The Ontario trial of active compression-decompression cardiopulmonary resuscitation for in-hospital and prehospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 1996;275:1417–1423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Plaisance P, Adnet F, Vicant E, Hennequin B, Magre P, Prudhomme C, et al. Benefit of active compression decompression CPR as a prehospital advanced cardiac life support. Circulation. 1997;95:955–961. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.4.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hapnes S, Robertson C. CPR—drug delivery routes and systems. Resuscitation. 1992;24:137–142. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(92)90019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Redding JS, Pearson JW. Evaluation of drugs for cardiac resuscitation. Anaesthesiology. 1963;24:203–207. doi: 10.1097/00000542-196303000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Redding JS, Pearson JW. Adrenaline in cardiac resuscitation. Am Heart J. 1963;66:210–214. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(63)90036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Woodhouse SP, Cox S, Boyd P, Case C, Weber M. High dose and standard dose adrenaline do not alter survival compared with placebo in cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 1995;30:243–249. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(95)00890-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Herlitz J, Ekstrom L, Wennerblom B, Axelsson A, Bang A, Holmberg S. Adrenaline in out of hospital ventricular fibrillation. Does it make any difference? Resuscitation. 1995;29:195–201. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(94)00851-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Callaham ML, Modsen CD, Barton CW, Saunders CE, Pointer J. A randomised clinical trial of high-dose epinephrine and noradrenaline vs standard dose epinephrine in prehospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 1992;268:2667–2672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abramson NS, Safar P, Sutton-Tyrrel K. A randomised clinical trial of escalating doses of high dose epinephrine during cardiac resuscitation [abstract] Crit Care Med. 1995;23:A178. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lindner KH, Ahnefeld FW, Prengel AW. Comparison of standard and high-dose adrenaline in the resuscitation of asystole and electromechanical dissociation. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1991;35:253–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1991.tb03283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Steill IG, Hebert PC, Weitzman BW, Wells GA, Raman S, Stark RM, et al. High dose epinephrine in adult cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1045–1050. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210083271502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brown CG, Martin DR, Pepe PE, Steuven H, Cummins RO, Gonzales E. A comparison of standard-dose and high-dose epinephrine in cardiac arrest outside the hospital. The Multicenter High-dose Epinephrine Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1051–1055. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210083271503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morady F, Nelson SD, Kon WF. Electrophysiological effects of epinephrine in humans. J Am Col Cardiol. 1988;11:1335–1344. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)90287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tang W, Weil MH, Sun S, Noc M, Yang L, Gasmuri RJ. Epinephrine increases the severity of post-resuscitation myocardial dysfunction. Circulation. 1995;92:3089–3093. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.10.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lathers CM, Tyau LSY, Spino MM, Agarwal I. Cocaine-induced seizures, arrhythmias and sudden death. J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;28:584–593. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1988.tb03181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lange RA, Cigarroa RG, Yancy CW, Willard JE, Popma JJ, Sills MN, et al. Cocaine-induced coronary artery vasoconstriction. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1557–1562. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198912073212301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sheperd RT. Mechanism of sudden death associated with volatile substance abuse. Hum Toxicol. 1989;8:287–292. doi: 10.1177/096032718900800406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boon NA. Solvent abuse and the heart. BMJ. 1987;294:722. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6574.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lindner KH, Prengel AW, Pfenninger EG, Lindner IM, Strohmenger HU, Georgieff M, et al. Vasopressin improves vital organ blood flow during closed-chest cardiopulmonary resuscitation in pigs. Circulation. 1995;91:215–221. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.1.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lindner KH, Prengel AW, Brinkmann A, Strohmenger HU, Lindner IM, Lurie KG. Vasopressin administration in refractory cardiac arrest. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:1061–1064. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-12-199606150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Babbs CF, Yim GKW, Whistler SJ, Tacker WA, Geddes LA. Elevation of ventricular defibrillation threshold in dogs by antiarrhythmic drugs. Am Heart J. 1979;98:345–350. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(79)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chow MSS, Kluger J, Lawrence R, Fieldman A. The effect of lidocaine and bretylium on the defibrillation threshold during cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Proc Soc Exper Biol Med. 1986;182:63–67. doi: 10.3181/00379727-182-42309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dorian P, Fain ES, Davy JM, Winkle RA. Lidocaine causes a reversible, concentration-dependent increase in defibrillation energy requirements. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:327–332. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Echt DS, Black JN, Barbey JT, Coxe DR, Cato E. Evaluation of antiarrhythmic drugs on defibrillation energy requirements in dogs. Sodium channel block and action potential prolongation. Circulation. 1989;79:1106–1117. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.5.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Natale A, Jones DL, Kim Y-H, Klein GJ. Effects of lidocaine on defibrillation threshold in the pig: evidence of anesthesia related increase. Pace. 1991;14:1239–1244. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1991.tb02862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kerber RE, Pandian NG, Jensen SR, Constantin L, Kieso R, Melton J, et al. Effect of lidocaine and bretylium on energy requirements for transthoracic defibrillation: experimental studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;7:397–405. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80512-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kerber RE, Jensen SR, Gascho JA, Grayzel J, Hoyt R, Kennedy J. Determinants of defibrillation: prospective analysis of 183 patients. Am J Cardiol. 1983;52:739–745. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(83)90408-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lake CL, Kron IL, Mentzer RM, Crampton RS. Lidocaine enhances intraoperative ventricular defibrillation. Anesth Analg. 1986;65:337–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Von Planta M, Chamberlain DA. Drug treatment of arrhythmias during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 1992;24:227–232. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(92)90182-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brown DC, Lewis AJ, Criley JM. Asystole and its treatment: the possible role of the parasympathetic nervous system in cardiac arrest. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians. 1979;8:448–452. doi: 10.1016/s0361-1124(79)80058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Iseri LT, Humphrey SB, Sirer EJ. Prehospital bradyasystolic cardiac arrest. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88:741–745. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-88-6-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Coon GC, Clinton JE, Ruiz E. Use of atropine for bradyasystolic prehospital cardiac arrest. Ann Emerg Med. 1981;10:462–467. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(81)80277-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Steuven HA, Tonsfeldt DJ, Thomson BM. Atropine in asystole: human studies. Ann Emerg Med. 1984;13:815–817. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(84)80447-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chamberlain DA, Turner P, Sneddon JM. Effects of atropine on heart-rate in healthy man. Lancet. 1967;ii:12–15. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(67)90057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Steedman DJ, Robertson CE. Acid base changes in arterial and central venous blood during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Arch Emerg Med. 1992;9:169–176. doi: 10.1136/emj.9.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Henreman PL, Ember JE, Marx JA. Development of acidosis in human beings during closed chest and open chest CPR. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:672–675. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(88)80607-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gilston A. Clinical and biochemical aspects of cardiac resuscitation. Lancet. 1965;ii:1039–1043. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(65)90570-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Von Planta M, Weil MH, Gazmuri RJ, Bisera J, Rackow EC. Myocardial acidosis associated with CO2 production during cardiac arrest and resuscitation. Circulation. 1989;80:684–692. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.3.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Capparelli EV, Chow MSS, Kluger J, Fieldman A. Difference in systemic and myocardial blood acid-base status during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Crit Care Med. 1989;17:442–446. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198905000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gudipati CV, Weil MH, Gazmuri RJ, Deshmukh HG, Bisera J, Rackow EC. Increases in coronary vein CO2 during cardiac resuscitation. J Appl Physiol. 1990;68:1405–1408. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.68.4.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kette F, Weil MH, Gazmuri RJ, Bisera J, Rackow EC. Intramyocardial hypercarbic acidosis during cardiac arrest and resuscitation. Crit Care Med. 1993;21:901–906. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199306000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Javaheri S, Clendening A, Papadakis N, Brody JS. pH changes in the surface of brain and in cisternal fluid in dogs in cardiac arrest. Stroke. 1984;15:553–558. doi: 10.1161/01.str.15.3.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kette F, Weil MH, Gazmuri RJ. Buffer solutions may compromise cardiac resuscitation by reducing coronary perfusion pressure. JAMA. 1991;266:2121–2126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gazmuri RJ, von Planta M, Weil MH, Rackow EC. Cardiac effects of carbon dioxide-consuming and carbon dioxide-generating buffers during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:482–489. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bleske BE, Rice TL, Warren EW, De Las Alas VR, Tait AR, Knight PR. The effect of sodium bicarbonate administration on the vasopressor effect of high-dose epinephrine during cardiopulmonary resuscitation in swine. Am J Emerg Med. 1993;11:439–443. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(93)90078-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dybvik T, Strand T, Steen PA. Buffer therapy during out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 1995;29:89–95. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(95)00850-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Koster RW. Correction of acidosis during cardio-pulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 1995;29:87–88. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(95)00849-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Caldwell G, Millar G, Quinn E, Vincent R, Chamberlain DA. Simple mechanical methods for cardioversion: defence of the precordial thump. BMJ. 1985;291:627–630. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6496.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Robertson C. The precordial thump and cough techniques in advanced life support. Resuscitation. 1992;24:133–135. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(92)90018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Paracek EA, Munger MA, Rutherford WF, Gardner SF. Report of nitropatch explosions complicating defibrillation. Am J Emerg Med. 1992;10:128–129. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(92)90044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Adgey AAJ. The Belfast experience with resuscitation ambulances. Am J Emerg Med. 1984;2:193–209. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(84)90002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sedgwick ML, Dalziel K, Watson J, Carrington DJ, Cobbe SM. Performance of an established system of first responder out of hospital defibrillation. Resuscitation. 1993;26:75–88. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(93)90166-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Myerburg RJ, Conde CA, Sing RJ, Mayorga-Cortes A, Mallon SM, Sheps DS, et al. Clinical, electrophysiological and haemodynamic profile of patients resuscitated from prehospital cardiac arrest. Am J Med. 1980;68:568–576. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90307-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Isen LT, Humphrey SB, Sirer EJ. Prehospital bradyasystolic cardiac arrest. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88:741–745. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-88-6-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Herlitz J, Ekstrom L, Wennerblom B, Axelsson A, Bang A, Holmberg S. Survival among patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest found in electromechanical dissociation. Resuscitation. 1995;29:97–106. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(94)00821-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sandoe E. Ventricular standstill and percussion. Resuscitation. 1996;32:3–4. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(96)00978-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dowdle JR. Ventricular standstill and cardiac percussion. Resuscitation. 1996;32:31–32. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(96)00977-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Scherf D, Bornemann C. Thumping of the precordium in ventricular standstill. Am J Cardiol. 1960;5:30–40. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(60)90006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Edgren E, Hedstrand N, Kelsey S, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Safar P BRCT 1 Study Group. Assessment of neurological prognosis in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest. Lancet. 1994;343:1055–1059. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Roine RO, Kaste M, Kinnunen A, Nikki P, Sarna S, Kajaste S. Nimodipine after resuscitation from out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation. A placebo controlled, double blind, randomized trial. JAMA. 1990;264:3171–3177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Brain Resuscitation Clinical Trial II Study Group. A randomized study of calcium entry blocker (lidoflazine) administration in the treatment of comatose survivors of cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1225–1231. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199105023241801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Graves JR, Herlitz J, Axelsson A, Ekstrom L, Holmberg M, Lundquist J, et al. Survivors of out of hospital cardiac arrest: their prognosis, longevity and functional status. Resuscitation. 1997;35:117–122. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(97)00035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Cantu RC, Ames A, Di Giancinto G, Dixon J. Hypotension: a major factor limiting recovery from cerebral ischaemia. J Surg Res. 1969;9:525–529. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(69)90129-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sieber FE, Traystman RJ. Special issues, glucose and the brain. Crit Care Med. 1991;20:104–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Longstreth WT, Inin TS. High blood glucose level on hospital admission and poor neurological recovery after cardiac arrest. Ann Neurol. 1984;15:59–63. doi: 10.1002/ana.410150111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Buylaert WA, Calle PA, Honbreckts HN Cerebral Resuscitation Study Group. Serum electrolyte disturbances in the post resuscitation period. Resuscitation. 1989;17:S189–S196. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(89)90104-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cobb LA, Werner J, Trobough G. Sudden cardiac death: a decade’s experience with out of hospital resuscitation. Mod Concepts Cardiovasc Dis. 1980;49:31–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Task Force on the Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Acute myocardial infarction: prehospital and in-hospital management. Eur Heart J. 1996;17:43–63. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a014691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute myocardial infarction. A report of the ACC/AHA task force on assessment of diagnostic and therapeutic cardiovascular procedures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;16:249–292. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90575-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Arntz HR, Bossaert L, Carli P, Chamberlain DA, Davies M, Dellborg M, et al. The prehospital management of acute heart attacks: report of a task force of ESC/ERC. Resuscitation (in press).