Abstract

Motivation: Microarrays are being increasingly used in cancer research to better characterize and classify tumors by selecting marker genes. However, as very few of these genes have been validated as predictive biomarkers so far, it is mostly conventional clinical and pathological factors that are being used as prognostic indicators of clinical course. Combining clinical data with gene expression data may add valuable information, but it is a challenging task due to their categorical versus continuous characteristics. We have further developed the mixture of experts (ME) methodology, a promising approach to tackle complex non-linear problems. Several variants are proposed in integrative ME as well as the inclusion of various gene selection methods to select a hybrid signature.

Results: We show on three cancer studies that prediction accuracy can be improved when combining both types of variables. Furthermore, the selected genes were found to be of high relevance and can be considered as potential biomarkers for the prognostic selection of cancer therapy.

Availability: Integrative ME is implemented in the R package integrativeME (http://cran.r-project.org/).

Contact: k.lecao@uq.edu.au

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

In clinical cancer studies, the primary treatment of localized cancer is either complete tumor excision with or without radiotherapy. The addition of systemic adjuvant therapies, such as chemotherapy or hormonal treatment has been shown to increase the chance of long-term survival but also to increase side effects and costs. Strong prognostic factors are, therefore, needed to predict more accurately the disease outcome as this would help physicians make treatment decisions. Various clinical or pathological factors have been evaluated as prognosis factors. For example, the treatment of primary breast cancer is often based on factors such as age, lymph node status, tumors size, among others, and also cell biological estrogen receptor status. Although these factors provide valuable information about the risk of recurrence, they are generally considered not to be sufficient to predict individual patient outcomes and determine an individual patient's need for systemic adjuvant therapy. In some cases, for example, patients with the same clinical parameters can have different clinical courses.

DNA microarray-based technology is seen as a great potential to gain new insight into cell biology and biological pathways. This technology has been mostly used to further delineate cancer subgroups or to identify candidate genes for cancer prognosis and therapeutic targeting. However, even though the identified gene signature was promising, e.g. the 70-gene signature from van't Veer et al. (2002), the clinical applications resulting from microarray statistical analyzes remain somewhat limited. This might be due to the complex and noisy nature of microarray data.

Utilizing both clinical factors and genetic markers may add complementary information and may lead to a more accurate prognostic. Another reason to combine both types of variables is purely economical. Indeed, if the combination of clinical factors and a small number of biomarkers would suffice to either (i) improve the prognostic prediction or (ii) reduce the number of biomarkers while performing as good as when using a bigger set of genes alone, this would imply major cost cutting in biomarkers driven clinical treatments. To this end, a first step would be to select a combined signature of both gene expressions and clinical factors, which would be used in an appropriate statistical methodology. Then, the last step would be to assess if the selected genes can be considered as potential biomarkers for the clinic.

The combination of both markers is a challenging task for two reasons. First, both types of variables do not measure the same entity. While microarray data are homogeneous, as the expression levels of genes or transcripts are measured, clinical variables are heterogeneous in their nature, as they can measure the age of the patient, but also the size of the tumor or the gender. Second, most clinical variables are of a categorical type, or are discretized by the physician, whereas microarray data are continuous data. Developing an appropriate methodology that can handle both types of variables, thus raises some statistical challenges.

Related work: few methodologies have been proposed so far to combine clinical factors and gene expression to improve cancer prognosis. In a general framework, Hothorn et al. (2006) proposed conditional inference trees to deal with various types of variables. Closer to our focus of application, several authors analyzed the van't Veer et al.'s (2002) study. While Dettling and Buhlmann (2004) proposed a penalized logistic regression (PELORA), Sun et al. (2007) selected a hybrid signature using the algorithm I-RELIEF and Gevaert et al. (2006) proposed Bayesian networks to automatically perform feature selection. The latter authors showed that their selection of three clinical variables and 13 genes had comparable results to the 70-signature genes from van't Veer et al.'s (2002) study, suggesting that the inclusion of clinical variables may, therefore, reduce the number of genes to reliably predict the prognosis. More recently, there have been further studies that assessed the additional predictive value of microarray data compared to clinical data alone. For example, Cox proportional hazards models were used on a simulation study (Truntzer et al., 2008), and a two-step approach based on Random Forests (RFs) and partial least squares (PLS) regression was also proposed by Boulesteix et al. (2008). Both articles cautioned the optimism or overestimation that appears in the integrated models as microarray data are artificially favored during the gene selection process (see also Tibshirani and Efron, 2002). Interestingly, when incorporating clinical variables on the van't Veer et al.'s (2002) data, Sun et al. (2007) found an improvement in the accuracy, Gevaert et al. (2006) found comparable results, and Dettling and Buhlmann (2004) and Boulesteix et al. (2008) found that the clinical variables did not contain much useful information for class prediction. It is likely that the performance results highly depend on the proposed statistical approach, as well as how both types of data are dealt with. For example, the clinical factors were rescaled in Sun et al. (2007), which rendered them continuous, whereas the gene expression data were discretized into three categories: baseline, overexpressed and underexpressed in Gevaert et al. (2006).

Why mixture of experts? Mixture of experts (ME) models (Jacobs et al., 1991) and their generalization, hierarchical ME models (Jordan and Jacobs, 1994) were introduced to account for non-linearities and other complexities in the data. It is based on a divide-and-conquer strategy to tackle a ‘complex problem by dividing it into simpler problems whose solutions can be combined to yield a solution to the complex problem’ (Jordan and Jacobs, 1994). ME are of interest due to their wide applicability [see for example Chen et al. (1999); Ng and McLachlan (2007) and, more recently, Gormley and Murphy (2008)] and the advantages of fast learning via the expectation–maximization (EM) algorithm (Dempster et al., 1977; Jordan and Xu, 1995). Recently, ME have been developed for classification purposes (Chen et al., 1999; Ng and McLachlan, 2007). In this study, we set into a binary classification framework as the cancer studies that we analyzed have a recurrence versus non-recurrence of metastasis outcome, or a patient's survival status outcome.

Our contribution: in this article, we propose to extend ME to combine clinical factors and gene expression using different functions to incorporate both types of variables. We propose to use different gene selection procedures before applying ‘integrative ME’. The results are obtained on three well-known cancer studies: prostate (Stephenson et al., 2005), breast (van de Vijver et al., 2002), and central nervous system (CNS; Pomeroy et al., 2002). We show that (i) categorical clinical variables can be included in a statistical model to circumvent the noisy nature of microarray data and improve cancer prognosis and (ii) the selected gene signature that is combined with these clinical variables can be considered as containing potential relevant biomarkers for the clinic.

2 APPROACH

2.1 ME for binary classification

Notations: let X denote the n × p matrix containing the column-centered expression values of p genes for the n patients and Z the n × q matrix containing the values of the q categorical clinical factors for these same n patients. In the case of binary classification problems, we assume that the output y is a discrete binary variable that has possible outcomes of ‘recurrence’ and ‘non-recurrence’. In the following, we denote xj and zj the output vectors on the jth sample and wj = (xjT, zjT)T the concatenated vector of both types of variables (j = 1,…, n).

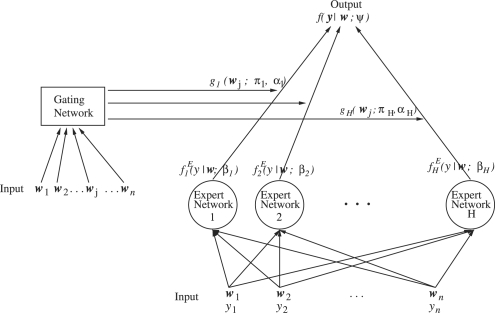

General principle: the ME architecture is shown in Figure 1. The expert networks sit at the leaves of the tree and the gating network sits at the non-terminals of the trees. Each expert h receives the input vector wj and produces an output vector (h = 1,…, H, j = 1,…, n). These output vectors then proceed up the tree and are blended by the gating network outputs, which also receives the vectors wj as input. The final output of the ME architecture is a convex weighted sum of all the output vectors produced by the experts and the gating network. The experts are trained on different partitions of the input space. As the data are allowed to lie simultaneously in multiple regions, it allows for an overlap between neighboring regions. This is called a ‘soft splits’ partitioning of the data, as opposed to ‘hard splits’ used in CART or MARS trees.

Fig. 1.

General principle of ME networks.

The expert networks: the output of each of the H experts is produced via a generalized linear function of the input. For example, in our classification problem, the Bernoulli distribution of possible binary outcomes of ‘recurrence’ and ‘non-recurrence’ is used

| (1) |

where βh is the unknown weight vector of the input wj.

The gating network: the gating network is also a generalized linear function and is modeled by the generic softmax function as

| (2) |

where πh > 0, ∑h=1H πh = 1, fhG(wj; αh) denotes a function with input vector wj and αh is the vector of unknown parameters for the hth expert. In integrative ME, we will use different types of gh functions to combine both clinical factors and microarray data.

Final output of ME: the final output of an ME neural network is a weighted sum of all the local output vectors produced by the experts

where Ψ is the vector of all the unknown parameters and can be estimated by the maximum likelihood approach via the EM algorithm. As both outputs from the gating and expert networks depend on the input w, the overall output of ME architecture is a non-linear function of the input.

2.2 Combining gene expression with categorical clinical factors

We propose to use different types of gating network functions to handle both categorical and continuous variables in the integrative ME approach.

Multinomial logit: this function was originally proposed by Jacobs et al. (1991) and Jordan and Xu (1995) and can be fitted via the iterative reweighted least squares (IRLS) algorithm (McCullagh and Nelder, 1989). In our case

where vh is a variable weight vector for each expert. The multinomial logit function is well adapted in our case to deal with different types of variables.

Independence model: the independence model is based on the naive assumption that the categorical variables are independent of each other and of the continuous variables. As was proposed by Ng and McLachlan (2005), the function fhG(wj; αh) in (2) is defined as

| (3) |

where ϕh(xj; μh, Σh) denotes a multivariate Gaussian function for input vector xj with mean μh and covariance matrix Σh, and fhi(zij) the hth conditional density of the ith categorical variable in zj, i = 1,…, q. If we denote ni the number of distinct values taken by the variable zi, we can then use a multinomial distribution that consists of one drawn on ni values with probabilities λhi1,…, λhini, where λhini = 1 − ∑l=1ni−1 λhil. Therefore, we have

| (4) |

where δ(zij, l) = 1 if zij = l and is zero otherwise (l = 1,…, ni).

Location model: the naive independence model can be modified to allow for some dependence between the two types of data, for example, by using a location model (Hunt and Jorgensen, 1999) as was proposed by Ng and McLachlan (2008). In the location model, some of the q′ most correlated categorical variables, q′ ≤ q are transformed into a single multinomial random variable U with S cells where S is the number of distinct patterns or locations of these variables. Thus, (3) is replaced by

where δ(j, s) = 1 if zij = s and is zero otherwise, and phs is the probability that the q′ categorical variables correspond to the sth pattern for the expert h, h = 1,…, H; s = 1,…, S. The conditional density of the remaining q − q′ categorical variables is as in (4).

This model does not impose any orders of the categories in each categorical variable. The q′ clinical variables are determined by testing the association between the q categorical variables, for example, via a simple χ2 test.

EM algorithm and parameter tuning. The application of the EM algorithms for the different integrative ME models can be found in Supplementary Material S1 to estimate the unknown parameters π, α and β. The tuning of the number of experts is also described.

2.3 Overview of the analysis

The additive power of combining clinical factors and genes markers as well as the relevancy of the genetic markers is assessed in three steps.

Step 1: variable selection: gene selection is an important step, not only to select informative and potentially relevant gene expression signature, but also to circumvent the ‘curse of dimensionality’. Indeed, integrative ME can be limited by a too large number of variables as in that case it will require the inversion of ill-conditioned matrices. Many variable selection procedures were proposed in the literature for classification purposes; see, for example, Guyon et al. (2002), Tibshirani et al. (2002) and Lê Cao et al. (2007), among many others. We propose to use three different types of methodologies:

a univariate filter method with the widely used t-test to select differentially expressed genes;

a wrapper method with RFs (Breiman, 2001) that proposes an internal importance measure to select discriminative genes;

a sparse exploratory approach called sparse PLS (sPLS; Lê Cao et al., 2008, 2009), which is similar to a sparse discriminant analysis approach.

As previously underlined (Tibshirani and Efron, 2002; Truntzer et al., 2008), combining genes and classical clinical variables tends to give biased results. Indeed, the predictive power of the genes tends to be overestimated as the outcomes y are already used during the selection process. Conversely, the clinical variables do not necessarily need to be selected as they are fewer (q = 5 − 10) and were often validated in many large studies. This artefact gives an artificial importance to the genes compared to the clinical variables if selection bias is not taken into account. In the following, we denote X* the dataset that contains only the p* selected gene expression values. p* is arbitrarily defined and is set to a small value as the focus is to find genetic biomarkers. To avoid overfitting issues, the p* genes are selected on a training set XL using, for example, K-fold cross-validation (say, K = 10).

Step 2: assess the predictive ability of the integrative ME model: once the p* genes are selected using one of the proposed variable selection procedure on the training samples L, both datasets X*L and ZL are combined to learn the parameters of integrative ME using the outcome yL. The class of the test samples T is then predicted using X*T, ZT and the parameters learnt in integrative ME. The predicted class is then compared to the real class label yT. This is performed K times to predict all samples in the study and to assess the predictive power of integrative ME.

Step 3: biological interpretation: the final aim of the analysis is to evaluate the biological relevance of the p* genes that were selected with the different variable selection methodologies (1), (2) or (3). Indeed, it would be extremely useful to the clinician to investigate whether these genes can be considered as potential biomarkers for cancer prognosis. Furthermore, this would also validate the biological relevance of the proposed integrative methodology.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Cancer datasets

The performance of integrative ME is compared to other related approaches on three cancer studies. The characteristics of the clinical data can be found in Supplementary Material S2.

Prostate data: we analyzed the gene expression and clinical data used in Stephenson et al. (2005). The dataset was built from tissue samples obtained from 79 patients all treated by radical prostatectomy. There were 37 samples that were classified as recurrent and 42 as non-recurrent primary prostate tumor. Gene expression analysis was carried out using the Affymetrix U133A human gene array and the prefiltered dataset contains 7884 features and eight clinical variables.

Breast data: The dataset from van de Vijver et al. (2002) contains gene expression of tumors from 256 patients who were all treated by modified radical mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery, 75 of them were classified as recurrent and 181 as non-recurrent metastasis within 5 years. The preprocessed data contain 5537 genes spotted on Agilent Hu25K microarrays. Eight prognostic factors were available and categorized as indicated by the authors.

CNS data: medulloblastomas are embryonal tumors of the CNS. Pomeroy et al. (2002) investigated this malignant brain tumor of childhood as the response of therapy is difficult to predict. The biopsies of 60 patients were obtained before they received any treatment, 21 patients died within 24 months and 39 survived. The expression level of 7128 genes were available, as well as five clinical variables.

3.2 Assessing classification performance

As a baseline, classification performance was first assessed on each separate dataset X and Z with different methodologies (Table 1). For the analysis of the clinical dataset Z only, RF, (Breiman, 2001) or a logistic regression (multinom) were applied. For the analysis of the X microarray dataset only, we compared the wrapper approaches RFs, recursive feature elimination (RFE; Guyon et al., 2002) and nearest shrunken centroids (NSCs; Tibshirani et al., 2002). These approaches include an internal variable selection step and the evaluation was, therefore, performed on the p* most relevant genes that were selected within these approaches. We also applied the PLS-RF methodology from (Boulesteix et al., 2008) on X*, where variable selection is performed beforehand with a t-test. Integrative ME was applied on X* with the three proposed variable selection procedures defined in Section 2.3.

Table 1.

Mean error rate percentage using 10-CV (10 validation trials) obtained on X* and Z alone

| Prostate | Breast | CNS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z | RF | 29.36 (1.43) | 29.96 (1.15) | 49 (3.61) |

| multinom | 29.74 (2.93) | 28.16 (1.18) | 40.33 (3.49) | |

| X* | RF | 27.72 (6.35) | 33.94 (2.60) | 41.83 (3.88) |

| RFE | 39.11 (3.93) | 29.49 (0.2) | 41.83 (4.61) | |

| NSC | 35.44 (0.6) | 31.79 (0.6) | 36.67 (3.14) | |

| PLS-RF | 33.64 (4.51) | 28.58 (0.84) | 36.99 (4.43) | |

| ME/X* | t-test (1) | 26.45 (2.89) | 28.83 (1.01) | 40.67 (4.17) |

| RF (2) | 28.86 (5.53) | 34.88 (1.82) | 46.17 (7.03) | |

| sPLS (3) | 26.71 (2.42) | 28.94 (2.22) | 41.33 (6.75) |

For X*, the wrapper approaches perform internal variable selection, with p* = 5.

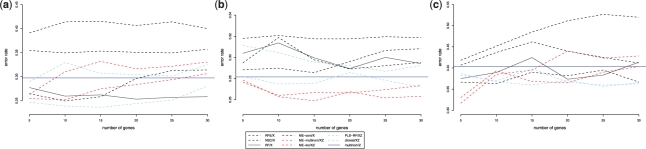

In Table 2, we compared integrative ME with a logistic regression (multinom), PLS-RF and cforest, which is based on conditional inference trees (Hothorn et al., 2006), on the combined datasets X*Z. With ME, the three gating functions were tested: independence function (indep), multinomial logit function (multinom) and the location function (loc) and the genes were selected with either t-test (1), RF (2), sPLS (3) for p* = 5. Figure 2 also displays the averaged error rate of some of the tested approaches where p* varies from 5 to 30.

Table 2.

Mean error rate percentage using 10-CV (10 validation trials) obtained on both datasets X*Z together

| Gene selection | t-test (1) | RF (2) | sPLS (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prostate | PLS-RF | 28.98 (4.16) | ||

| cforest | 24.65 (4.91) | |||

| multinom | 27.09 (2.47) | 26.33 (3.03) | 26.96 (4.74) | |

| ME-indep | 29.24 (4.44) | 28.86 (5.53) | 31.64 (3.48) | |

| ME-multinom | 26.32 (4.77) | 25.82 (4.74) | 27.59 (5.62) | |

| ME-loc | 25.44 (3.70) | 26.83 (2.44) | 23.54 (2.61) | |

| Breast | PLS-RF | 28.20 (1.86) | ||

| cforest | 31.15 (1.60) | |||

| multinom | 27.89 (1.69) | 31.33 (1.53) | 28.59 (2.02) | |

| ME-indep | 27.81 (1.47) | 30.19 (1.73) | 27.77 (1.28) | |

| ME-multinom | 27.65 (1.45) | 29.88 (1.80) | 27.89 (1.46) | |

| ME-loc | 27.85 (1.51) | 29.92 (1.25) | 27.26 (1.16) | |

| CNS | PLS-RF | 38.68 (2.18) | ||

| cforest | 38.33 (6.90) | |||

| multinom | 33.67 (5.49) | 36.83 (7.51) | 37.17 (4.16) | |

| ME-indep | 43.83 (6.5) | 42.81 (6.57) | 41.83 (4.81) | |

| ME-multinom | 33.00 (6.08) | 39.67 (6.08) | 35.67 (6.34) | |

| ME-loc | 31.67 (6.98) | 35.16 (5.63) | 35.33 (5.37) |

Classification performances which were as good or better than X* or Z alone (see Table 1) are indicated in bold (p* = 5).

Fig. 2.

Average error rates of different methods on prostate (a) breast (b) and CNS (c) with respect to the number of selected genes. Black lines, wrapper approaches on X* only; red lines, integrative ME on X* and Z and blue line: logistic regression on Z only.

Table 3 investigates the gain in accuracy when the clinical variables are also selected based on the outcome status y (q* = 3) and Table 4 compares the sensitivity and specificity measures of the tested approaches on X*, Z and X*Z for p* = 5.

Table 3.

Mean error rate percentage using 10-CV (10 validation trials) obtained when variable selection is performed on both X*Z* (p* = 5 and q* = 3)

| Gene selection | t-test (1) | RF (2) | sPLS (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prostate | PLS-RF | 29.36 (5.99) | ||

| cforest | 24.72 (3.62) | |||

| ME-indep | 26.45 (4.11) | 27.97 (4.24) | 25.95 (3.44) | |

| ME-multinom | 24.81 (2.25) | 24.68 (2.25) | 23.67 (2.53) | |

| Breast | PLS-RF | 27.15 (1.73) | ||

| cforest | 31.60 (1.74) | |||

| ME-indep | 27.19 (1.22) | 29.02 (1.29) | 26.21 (2.14) | |

| ME-multinom | 28.05 (2.16) | 31.76 (2.51) | 27.46 (1.93) | |

| CNS | PLS-RF | 38.68 (5.64) | ||

| cforest | 37.46 (4.65) | |||

| ME-indep | 36.5 (5.90) | 38.54 (5.87) | 42.83 (8.92) | |

| ME-multinom | 38 (3.49) | 36.67 (6.67) | 36.5 (5.58) |

Classification performances which were as good or better than X*Z (see Table 2) are indicated in bold.

Table 4.

Comparison of sensitivity and specificity percentages using 10-CV (10 validation trials) obtained on X*, Z and X*Z using different approaches (p* = 5)

| Sensitivity |

Specificity |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prostate | Breast | CNS | Prostate | Breast | CNS | ||

| Z | RF | 66.22 | 90.61 | 15.24 | 76.43 | 20.93 | 70.26 |

| X* | RF | 71.62 | 81.27 | 33.81 | 74.28 | 29.47 | 70.00 |

| PLS-RF | 64.05 | 85.63 | 36.67 | 72.86 | 35.2 | 73.07 | |

| ME+(1) | 65.94 | 75.19 | 44.28 | 70.95 | 54.67 | 69.49 | |

| ME+(2) | 67.02 | 71.71 | 31.90 | 74.76 | 49.20 | 65.64 | |

| ME+(3) | 70.81 | 78.45 | 43.33 | 75.47 | 53.20 | 66.92 | |

| X*Z | PLS-RF | 62.97 | 89.28 | 10.95 | 77.62 | 28.40 | 92.05 |

| cforest | 71.35 | 89.83 | 11.42 | 81.19 | 21.07 | 84.87 | |

| ME-indep (1) | 67.56 | 84.42 | 42.38 | 73.57 | 42.67 | 63.85 | |

| ME-indep (2) | 67.02 | 83.87 | 42.38 | 74.76 | 35.87 | 63.85 | |

| ME-indep (3) | 64.05 | 84.75 | 42.38 | 72.42 | 42.00 | 66.67 | |

| ME-multi (1) | 64.86 | 85.25 | 47.14 | 81.42 | 41.20 | 77.69 | |

| ME-multi (2) | 69.72 | 84.31 | 39.52 | 78.09 | 35.87 | 71.54 | |

| ME-multi (3) | 66.76 | 84.81 | 40.95 | 77.38 | 41.47 | 76.92 | |

| ME-loc (1) | 75.67 | 84.42 | 40.95 | 73.57 | 42.53 | 76.92 | |

| ME-loc (2) | 75.67 | 84.42 | 40.95 | 73.57 | 35.47 | 76.92 | |

| ME-loc (3) | 76.49 | 84.70 | 48.57 | 76.42 | 43.87 | 73.33 | |

(1), (2) and (3) indicate the variable selection procedure used (see Section 2.3).

3.3 Statistical results

Tables 1 and 2 show that the combination of clinical and microarray data improves the prognosis prediction in the three studies when the number of genes p* is small. It is interesting to see that integrative ME solely applied on X* data can give competitive results compared to the other related approaches (Table 1). Both experts and gating network, therefore, play an important role in the classification performance, first by soft partitioning the variable space (the experts) and second by weighting the experts that perform the best at solving the problem (the gating network). However, the inclusion of clinical variables is still necessary to improve the accuracy. Table 2 shows that the gain in the prediction performance using X* only to the integration of X* and Z can increase from 3% (ME/X* versus ME-loc) for prostate, from 1.5% (PLS-RF versus ME-loc) for breast and from 4% (NSC versus ME-loc) for CNS if we consider the best results obtained in both tables. These statistical results are consistent with the findings of the few related studies in the literature. For example, Boulesteix et al. (2008) found that their proposed PLS-RF methodology led to a 4% improvement in the accuracy on a colorectal dataset.

Following the results obtained in Tables 1 and 2, we further assessed the classification performance of some of the tested approaches with respect to the number of selected genes. The average values of the error rate estimates are plotted in Figure 2 to compare the performances of the approaches RFE, NSC, RF and integrative ME applied on the dataset X* alone, integrative ME with the multinomial or the location model with a t-test variable selection, and PLS-RF and cforest on X*Z. Generally, it is encouraging to see that integrative ME can perform better than clinical variables alone (horizontal line). In prostate and CNS studies, integrative ME on X*Z improves the prediction performance compared to X* alone when the number of selected genes is small (5–10). This argues in favor of a reduced number of potential gene markers and, therefore, of reduced costs in biomarkers driven prognosis. Only cforest on prostate seems to be competitive with integrative ME. For breast dataset, the results are also encouraging as no other wrapper approach is able to perform better than integrative ME, even when the number of selected genes increases. This improvement suggests a better hybrid signature of gene markers and clinical factors than a gene signature alone.

The variable selection step plays an important role in the predictive ability of the integrative ME model. Often, the best results were obtained with a t-test or a sPLS selection (Table 2). In addition, when clinical variables were also selected, the accuracy improved from 1% to 2% for prostate (breast) where Gleason stage, extra capsular extension and seminal vesicle invasion (histological grade, tumor diameter and age) were selected, when compared to the use of all clinical variables (Table 3 versus Table 2, independent and multinomial gating functions). These results could be explained by the relevance of the selected clinical variables. For prostate, for example, these three clinical factors have been described many times as very good markers for prognostic outcomes (Griebling et al., 1997; Montie, 1996). The accuracy improved up to 7% in CNS (age, tumour type and chemotherapy Cx selected). However, these results were not as good as when using the location gating function in integrative ME. The location model may, therefore, suffice when q is small as the most correlated clinical factors are replaced by a unique categorical variable, the location variable (see Supplementary Material S2 for the chosen locations).

Interestingly, both sensitivity and specificity criteria were improved when combining both datasets X*Z compared to X* or Z alone. With integrative ME, good improvements were obtained on prostate and CNS for both measures. Breast seems to be a particular case were the Z data tend to improve the sensitivity (i.e. classifying the recurrent cases), whereas the X* data tend to improve the specificity (i.e. classifying the non-recurrent cases). PLS-RF significantly improved the specificity in CNS, but not the sensitivity. Compared to the other approaches applied on X*Z (PLS-RF and cforest), these results show that integrative ME makes a good compromise to classify both recurrent and non-recurrent patients in their respective classes.

In overall, the location and multinomial gating functions seemed to perform the best in terms of classification performance and specificity/sensitivity when including all clinical variables, whereas the independent model seemed to be competitive once the clinical variables were selected on breast and CNS. The location gating function coupled with a t-test or a sPLS variable selection performed the best in the three studies.

3.4 Relevance of potential genetic markers

We further analyzed the biological relevance of the selected p* genes that were integrated with the clinical factors in integrative ME. The most relevant genes for the prostate dataset are presented in Table 5 and are discussed below (see Supplementary Material S3 for a detailed analysis of the other datasets).

Table 5.

Most relevant selected genes with a potential biomarker status in prostate

| Gene name (symbol) | Lvl | Gene selection method [rank] |

|---|---|---|

| Etoposide induced 2.4 mRNA (EI24) | + | t-test[1], RF[1], sPLS[1] |

| Erythrocyte membrane protein band 4.9 (EPB4.9) | − | t-test[2], sPLS[2] |

| CHMP1A | − | t-test[5], RF[2], sPLS[5] |

| ASNS | + | RF[4] |

| PTMA | + | RF[5] |

Expression level in subjects with respect to class ‘recurrent’ is indicated: overexpressed (+), underexpressed (−).

In the prostate cancer study, the best classification performance was obtained with the sPLS gene selection method. This result could be explained by the selection of very relevant genes closely linked to cancer phenotype. EPB4.9 gene is located on chromosome 8p21.1, a region frequently deleted in prostate carcinoma and could have a possible role in cell shape alteration, tumor progression and metastasis (Lutchman et al., 1999). EI24 is also located in a region frequently altered in several malignancies (Gu et al., 2000). EI24/PIG8 is a member of PIGs encoding proteins with activities related to the redox status of cells (Polyak et al., 1997), and has been linked to apoptosis modulation (Zhao et al., 2005). Chromatin-modifying protein 1A (CHMP1A) was recently found underexpressed in pancreatic tumors as well as in numerous cancers and was proposed as a tumor suppressor (Li et al., 2008). Several other genes selected by the sPLS method were related to the cellular metabolism in general (GCAT, ACAT2, etc.). Numerous studies highlighted the modification of cellular metabolism in cancer cells (Weinberg and Chandel, 2009). In addition, sPLS selected interesting genes amongst which STIP1, OGN and ITGB4 could be of relative importance (see Supplemental Material S3 for details). The t-test selection method gave similar prediction rate. Three important genes that could be considered as potential biomarkers were also present in the top list of the selected genes (EBP4.9, EI24 and CHMP1A). The RF gene selection method gave less performant results, nonetheless, these results were better than using microarray or clinical variables alone. Interestingly, the genes selected by RF were high of high interest. For example, asparagine synthetase (ASNS) and prothymosin alpha (PTMA). The ASNS expression is linked to cell growth and ASNS mRNA content is controlled in accordance with changes in the cell cycle (Greco et al., 1987). Numerous studies showed that a high level of ASNS expression was correlated with drug resistance in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL; Richards and Kilberg, 2006). Recently, Estes et al. (2007) demonstrated that ASNS silencing could revert T-ALL cells to drug sensitivity. PTMA is an histone H1-binding protein ubiquitously expressed and correlated with several cancer progression. Suzuki et al. (2006) demonstrated that PTMA is involved in the differentiation and progression of prostate adenocarcinomas and could become a candidate target for therapy and diagnosis. Although these genes have been either implied in the numerous cancers, or identified as potential biomarker, further investigations need to be performed to clarify the contribution of these selected genes to prostate carcinoma recurrences.

4 CONCLUSION

We have presented a method to combine categorical clinical factors and continuous gene expression variables in a hybrid signature. We have shown that the gene selection step did yield important biological insights into the cancer studies. These genes should be investigated further to validate them as potential biomarkers.

The ME methodology was improved by proposing different gating networks function to combine clinical factors and gene expression. In addition, three different gene selection procedures were proposed that improved the prognosis prediction accuracy on three cancer studies. We also investigated the gain in accuracy when selecting clinical variables based on the outcome status. The accuracy was improved for the independent gating function in integrative ME, but in general, we showed that the location model sufficed to give good results as the number of clinical variables was small. Furthermore, we showed that sensitivity and specificity criteria were generally improved with integrative ME. Therefore, both types of variables should not be neglected or separately analyzed. Indeed, although microarray data can help uncover new features into cancer cell biology, cancer prognosis cannot solely rely on microarray data without taking into account the clinical characteristics of the patients. Conversely, clinical factors have valuable information about the risk of recurrence but they lack accuracy to determine the need of systemic adjuvant therapy. The availability of larger-scale studies involving the records of a larger number of clinical variables will undoubtedly allow better improvements in the prediction accuracy, as we will be able to select disease-specific clinical variables that are more closely related to the cancer study.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the three reviewers for their constructive comments, which substantially improved the manuscript. We thank Dr. S.K. Ng (Griffith University) who provided the original Fortran ME programs and Dr J. Satagopan (University of Wisconsin) for making the prostate dataset available.

Funding: Australian Research Council under the ARC Centres of Excellence program, ARC Centre of Excellence in Bioinformatics (to K.-A.L.C.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Boulesteix A, et al. Microarray-based classification and clinical predictors: on combined classifiers and additional predictive value. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1698. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiman L. Random forests. Mach. learn. 2001;45:5–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, et al. Improved learning algorithms for mixture of experts in multiclass classification. Neural Netw. 1999;12:1229–1252. doi: 10.1016/s0893-6080(99)00043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster A, et al. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. J. R Stat. Soc. Ser. B. 1977;1:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dettling M, Buhlmann P. Finding predictive gene groups from microarray data. J. Multivariate Anal. 2004;90:106–131. [Google Scholar]

- Estes D, et al. Genetic alterations determine chemotherapy resistance in childhood T-ALL: modelling in stage-specific cell lines and correlation with diagnostic patient samples. Br. J. Haematol. 2007;139:20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gevaert O, et al. Predicting the prognosis of breast cancer by integrating clinical and microarray data with Bayesian networks. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:e184–e190. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gormley I, Murphy T. A mixture of experts model for rank data with applications in election studies. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2008;2:1452–1477. [Google Scholar]

- Greco A, et al. Molecular cloning of a gene that is necessary for G1 progression in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 1987;84:1565–1569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.6.1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griebling T, et al. Prognostic implications of extracapsular extension of lymph node metastases in prostate cancer. Mod. Pathol. 1997;10:804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyon I, et al. Gene selection for cancer classification using support vector machines. Mach. learn. 2002;46:389–422. [Google Scholar]

- Gu Z, et al. ei24, a p53 response gene involved in growth suppression and apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:233–241. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.1.233-241.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn T, et al. Unbiased recursive partitioning: a conditional inference framework. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 2006;15:651–674. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt L, Jorgensen M. Mixture model clustering using the MULTIMIX program. Aust. N. Z. J. Stat. 1999;41:154–171. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs R, et al. Adaptive mixtures of local experts. Neural Comput. 1991;3:79–87. doi: 10.1162/neco.1991.3.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan M, Jacobs R. Hierarchical mixtures of experts and the EM algorithm. Neural Comput. 1994;6:181–214. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan M, Xu L. Convergence results for the EM approach to mixtures of experts architectures. Neural Netw. 1995;8:1409–1431. [Google Scholar]

- Lê Cao K.-A, et al. Selection of biologically relevant genes with a wrapper stochastic algorithm. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2007;6:29. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lê Cao K.-A, et al. Sparse PLS: variable selection when integrating omics data. Stat. Appl. Mol. Biol. 2008;7:37. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lê Cao K.-A, et al. integrOmics: an R package to unravel relationships between two omics data sets. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2855–2856. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, et al. Chmp1A functions as a novel tumor suppressor gene in human embryonic kidney and ductal pancreatic tumor cells. Cell cycle. 2008;7:2886. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.18.6677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutchman M, et al. Loss of heterozygosity on 8p in prostate cancer implicates a role for dematin in tumor progression. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 1999;115:65–69. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(99)00081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullagh P, Nelder J. Generalized linear models. London: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Montie J. Current prognostic factors for prostate carcinoma. CA Cancer J. Clin. 1996;78:341–344. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960715)78:2<341::AID-CNCR24>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng S, McLachlan G. Normalized Gaussian networks with mixed feature data. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2005;3809:879. [Google Scholar]

- Ng S, McLachlan G. Extension of mixture-of-experts networks for binary classification of hierarchical data. Artif. Intell. Med. 2007;41:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng S, McLachlan G. Expert networks with mixed continuous and categorical feature variables: a location modeling approach. In: Peters. H, Vogel. M, editors. Machine Learning Research Progress. Hauppauge, New York: Nova Science; 2008. pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Polyak K, et al. A model for p53-induced apoptosis. Nature. 1997;389:300–5. doi: 10.1038/38525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomeroy S, et al. Prediction of central nervous system embryonal tumour outcome based on gene expression. Nature. 2002;415:436–442. doi: 10.1038/415436a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards N, Kilberg M. Asparagine synthetase chemotherapy. Annu. Rev. 2006;75:629–654. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson A, et al. Integration of gene expression profiling and clinical variables to predict prostate carcinoma recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Cancer. 2005;104:290–298. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, et al. Improved breast cancer prognosis through the combination of clinical and genetic markers. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:30. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, et al. Expression of prothymosin alpha is correlated with development and progression in human prostate cancers. Prostate. 2006;66 doi: 10.1002/pros.20385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani R, Efron B. Pre-validation and inference in microarrays. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2002;1 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1000. Article 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani R, et al. Diagnosis of multiple cancer types by shrunken centroids of gene expression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2002;99:6567–6572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082099299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truntzer C, et al. Comparative optimism in models involving both classical clinical and gene expression information. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:434. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van't Veer L, et al. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature. 2002;415:530. doi: 10.1038/415530a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Vijver M, et al. A gene-expression signature as a predictor of survival in breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;347:1999–2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg F, Chandel N. Mitochondrial metabolism and cancer. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009;1177:66–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, et al. Apoptosis factor EI24/PIG8 is a novel endoplasmic reticulum-localized Bcl-2-binding protein which is associated with suppression of breast cancer invasiveness. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2125–2129. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.