Abstract

Summary: TopoGSA (Topology-based Gene Set Analysis) is a web-application dedicated to the computation and visualization of network topological properties for gene and protein sets in molecular interaction networks. Different topological characteristics, such as the centrality of nodes in the network or their tendency to form clusters, can be computed and compared with those of known cellular pathways and processes.

Availability: Freely available at http://www.infobiotics.net/topogsa

Contact: nxk@cs.nott.ac.uk; avalencia@cnio.es

1 INTRODUCTION

Functional genomic experiments provide researchers with a wealth of information delineating gene sets of biological interest. To interpret these lists of genes, common steps in a functional gene set analysis include the search for enrichment patterns [for a review, see (Abatangelo et al., 2009)], e.g. to identify significant signalling pathways or protein domains, and text mining in the literature [see review by (Krallinger et al., 2008)]. Another approach for the functional interpretation of gene sets is the analysis of molecular interactions in which the genes or their corresponding proteins are involved, in particular protein–protein interactions. In this context, some existing bioinformatics tools already allow users to map genes onto networks of interacting or functionally associated molecules to identify related genes and proteins (Jenssen et al., 2001; Snel et al., 2000). However, to the best of the authors' knowledge, so far these tools do not take into account topological properties in interaction networks to analyse and compare gene sets.

In this article, we introduce TopoGSA (Topology-based Gene Set Analysis), a web-tool to visualize and compare network topological properties of gene or protein sets mapped onto interaction networks.

2 WORKFLOW AND METHODS

2.1 Analysis of network topological properties

An analysis begins with the upload of a list of gene or protein identifiers (Ensembl IDs, HGNC symbols, etc.; see webpage for a complete list of supported formats). Alternatively, a microarray dataset can be used as input and differentially expressed genes will be extracted automatically using methods from a previously published online microarray analysis tool [arraymining.net (Glaab et al., 2009)]. Moreover, the user can add labels to the uploaded identifiers to compare different subsets of genes (e.g. ‘up- regulated’ versus ‘down-regulated’ genes).

After submitting the list of identifiers, the application maps them onto an interaction network (Section 4), and computes topological properties for the entire network, the uploaded gene/protein set and random sets of matched sizes. The available network topological properties are:

The degree of a node (gene or protein) is the average number of edges (interactions) incident to this node.

The local clustering coefficient quantifies the probability that the neighbours of a node are connected (Watts and Strogatz, 1998).

The shortest path length (SPL) for two nodes vi and vj in an undirected, unweighted network is defined as the minimum number of edges that have to be traversed to reach vj from vi. We use the SPL as a centrality measure, computing the average SPL from each node of interest to all other nodes in the network.

- The node betweenness B(v) of a node v can be calculated from the number of shortest paths σst from nodes s to t going through v:

(1) The eigenvector centrality measures the importance of network nodes by applying a centrality definition, in which the score of each node reciprocally depends on the scores of its neighbours. More precisely, the centrality scores are given by the entries of the dominant eigenvector of the network adjacency matrix (see Bonacich et al., 2001, for a detailed discussion of this property).

Furthermore, user-defined 2D and 3D representations can be displayed for each individual gene/protein in the dataset and plotted data points are interlinked with relevant entries in an online annotation database.

2.2 Comparison with known gene sets

The analysis of network topological properties of only a single gene/protein set does not lend itself to direct functional interpretation. However, TopoGSA enables the user to compare the properties of a dataset of interest with a multitude of predefined datasets corresponding to known functional processes from public databases. For the human species, these include signalling pathways [KEGG (Kanehisa et al., 2006), BioCarta (Nishimura, 2001)], Gene Ontology [Biological Process, Molecular Function and Cellular Component (Ashburner et al., 2000)] and InterPro protein domains (Apweiler et al., 2001). Summaries of network topological properties are provided for all gene/protein sets, and in the 2D and 3D plots different colours distinguish different datasets. Users can identify pathways and processes similar to the uploaded dataset visually, based on the plots or based on a tabular ranking using a numerical score to quantify the similarity across all topological properties. The similarity score is obtained by computing five ranks for each pathway/process set according to the absolute differences between each of its five median topological properties and the corresponding value for the uploaded dataset. The sum of ranks across all topological properties is then computed and normalized to a range between 0 and 1.

3 EXAMPLE ANALYSIS

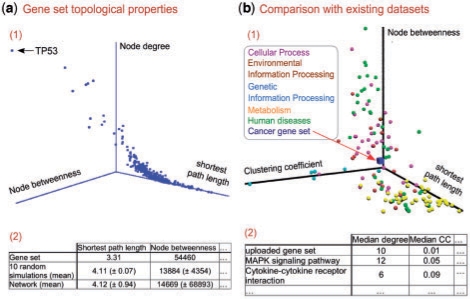

It has been shown that proteins encoded by genes that are known to be mutated in cancer have a higher average node degree in interaction networks than other proteins (Jonsson et al., 2006). This observation is confirmed by a TopoGSA analysis of the complete set of genes currently known to be mutated in cancer [Futreal et al. (2004), http://www.sanger.ac.uk/genetics/CGP/Census]. The cancer genes are involved in more than twice as many interactions, on average, than matched-size random subsets of network nodes (with a difference of > 15 SDs for 10 random simulations). Furthermore, the analysis with TopoGSA reveals that the cancer genes are closer together in the network (in terms of their average pairwise shortest path distances) than random gene sets of matched sizes and occupy more central positions in the interaction network (see Fig. 1a for details). The 3D plot displaying node betweenness, degree and SPL reveals in particular the tumour suppressor p53's (TP53) outstanding network topological properties.

Fig. 1.

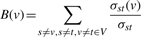

Example results produced with TopoGSA based on the cancer gene set by Futreal et al. (2004). (a) Topological properties can be computed and examined as visual (1) and tabular (2) outputs; (b) The gene set can be compared with a chosen reference database (here the KEGG database).

When comparing the network topological properties of the cancer proteins with pathways from the KEGG database, considering each individual pathway as a gene set (Fig. 1b), the cancer proteins appear to have network properties comparable to several KEGG cellular processes and environmental information processing pathways [according to the KEGG-BRITE pathway hierarchy (Kanehisa et al., 2006), Fig. 1b, purple and brown], whereas they clearly differ from metabolism-related pathways (Fig. 1b, yellow). Interestingly, although the network topological properties of cancer genes are in agreement with their role in promoting cell division and inhibiting cell death (Vogelstein and Kinzler, 2004), they differ from those of most disease-related KEGG pathways (Fig. 1b, green).

4 IMPLEMENTATION

The network analysis and gene mapping was implemented in the programming language R and the web interface in PHP. To build a human protein interaction network, experimental data from five public databases [MIPS (Mewes et al., 1999), DIP (Xenarios et al., 2000), BIND (Bader et al., 2001), HPRD (Peri et al., 2004) and IntAct (Hermjakob et al., 2004)] were combined and filtered for binary interactions by removing entries with PSI-MI codes for detection methods that cannot verify direct binary interactions (these are evidence codes for co-immunoprecipitation or colocalization, for example; details on the used method definitions and PSI-MI codes can be found in the ‘Datasets’ section on the webpage). This filtering resulted in a network consisting of 9392 proteins and 38 857 interactions. Additionally, protein interaction networks for the model organisms yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), fly (Drosophila melanogaster), worm (Caenorhabditis elegans) and plant (Arabidopsis thaliana) have been built using the same methodology as for the human network and the BioGRID database (Stark et al., 2006) as additional data source (see the help sections on the webpage for additional details on these networks). TopoGSA will be updated periodically twice per year to integrate newly available protein interaction data and reference gene sets. Moreover, users can upload their own networks. A video tutorial and instructions on how to use the web tool are available in the ‘Tutorial’ section on the webpage.

Funding: Marie-Curie EarlyStage-Training programme (MEST-CT-2004-007597); the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BB/F01855X/1); Spanish Ministry for Education and Science (BIO2007-66855); Juan de la Cierva post-doctoral fellowship (to A.B.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Abatangelo L, et al. Comparative study of gene set enrichment methods. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:275. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apweiler R, et al. The InterPro database, an integrated documentation resource for protein families, domains and functional sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:37. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M, et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader G, et al. BIND–the biomolecular interaction network database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:242–245. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonacich P, et al. Eigenvector-like measures of centrality for asymmetric relations. Soc. Networks. 2001;23:191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Futreal P, et al. A census of human cancer genes. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2004;4:177–183. doi: 10.1038/nrc1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaab E, et al. ArrayMining: a modular web-application for microarray analysis combining ensemble and consensus methods with cross-study normalization. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:358. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermjakob H, et al. IntAct: an open source molecular interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D452–D455. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenssen T, et al. A literature network of human genes for high-throughput analysis of gene expression. Nat. Genet. 2001;28:21–28. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson P, et al. Global topological features of cancer proteins in the human interactome. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2291–2297. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, et al. From genomics to chemical genomics: new developments in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D354–D357. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krallinger M, et al. Linking genes to literature: text mining, information extraction, and retrieval applications for biology. Genome Biol. 2008;9(Suppl. 2):S8. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-s2-s8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mewes H, et al. MIPS: a database for genomes and protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:44–48. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura D. BioCarta. Biotech Softw. Internet Rep. 2001;2:117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Peri S, et al. Human protein reference database as a discovery resource for proteomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D497. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snel B, et al. STRING: a web-server to retrieve and display the repeatedly occurring neighbourhood of a gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:3442–3444. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.18.3442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark C, et al. BioGRID: a general repository for interaction datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D535. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein B, Kinzler K. Cancer genes and the pathways they control. Nat. Med. 2004;10:789–799. doi: 10.1038/nm1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts D, Strogatz S. Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks. Nature. 1998;393:440–442. doi: 10.1038/30918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xenarios I, et al. DIP: the database of interacting proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:289–291. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]