Abstract

Thalamic inputs strongly drive neurons in the primary visual cortex, even though these neurons constitute only ~5% of the synapses on layer 4 spiny stellate simple cells. We modeled the feedforward excitatory and inhibitory inputs to these cells based on in vivo recordings in cats, and we found that the reliability of spike transmission increased steeply between 20 and 40 synchronous thalamic inputs in a time window of 5 milliseconds, when the reliability per spike was most energetically efficient. The optimal range of synchronous inputs was influenced by the balance of background excitation and inhibition in the cortex, which could gate the flow of information into the cortex. Ensuring reliable transmission by spike synchrony in small populations of neurons may be a general principle of cortical function.

Neurons can perform coincidence detection of synaptic inputs with a temporal integration window that depends on the time courses of the synaptic conductances and the intrinsic properties of the postsynaptic neuron (1). Synchronous cortical inputs occur when there is a salient event in the sensory environment, such as the entrance of a moving object into a receptive field (2) or the deflection of a whisker in rodent (3). The precise timing of action potentials has been shown to potentially provide information in addition to the spike rate (2, 4–7). For a population of pre-synaptic neurons to fire nearly simultaneously, however, requires resources to time spike initiation precisely, parallel anatomical pathways to carry the spikes, and energy costs for redundant spikes, which may outweigh the benefits of increased information rate (8, 9). We explored these issues in the projections from the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) to the primary visual cortex.

The question of efficient information transfer is particularly important for thalamocortical connections, because thalamic synaptic inputs, which are comparable in strength to cortical inputs, constitute only ~5% of the total synaptic input to cortical simple cells (10–12), but are nonetheless capable of reliably driving cortical neurons. To examine the relationship between synchrony and reliability, we performed computer simulations of a detailed biophysical model of a spiny stellate cell in layer 4 of area V1 (13) of the cat primary visual cortex (Fig. 1A). This cell received 300 synaptic inputs from the LGN, competing with 5500 other excitatory and inhibitory intracortical synapses, including feedforward inhibition. All synapses were stochastic, and the excitatory synapses included short-term history-dependent modulation of release probability. We used this model to quantify the number of synchronous synaptic inputs that maximizes the efficient transfer of information to the cortical cell, and we compared these predictions to experimental data obtained in vivo from anesthetized cats (14).

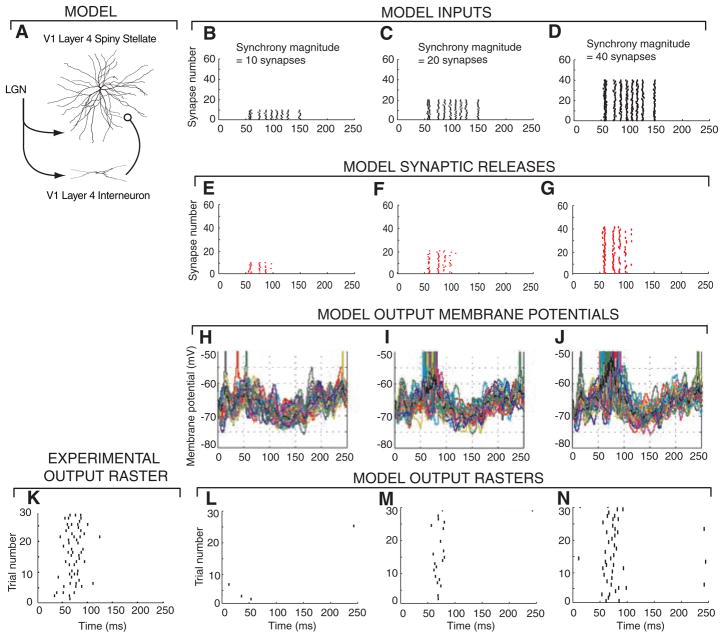

Fig. 1.

Varying the synchrony of input synapses affects output reliability and firing rates. (A) Morphology of a reconstructed V1 layer 4 spiny stellate cell that was modeled with 748 compartments, thalamocortical (TC) synapses with a release probability of P = 0.2 and short-term plasticity (13, 14), and a feedforward inhibitory interneuron that receives input from LGN and projects to the spiny stellate cell. (B to D) Rastergrams of 60 thalamocortical synaptic inputs into the model cell for one trial. An input spike train obtained from in vivo LGN recordings (21) (referred to as event times) was repeated on a number of input synapses (SM). The input events were time jittered on average by 1 ms and had 1 out of 10 spikes randomly deleted. (E to G) Synaptic release rastergram for inputs (B to D). (H to J) Superimposed spiny stellate membrane potentials from 30 trials. (K) Cortical cell output spike trains from experimental in vivo recordings (21). (L to N) Rastergrams of outputs from 30 trials of inputs based on different LGN spike trains from the in vivo data.

The pairwise correlation strength between two neurons is often used to estimate their degree of synchrony (15, 16). In the visual thalamocortical pathway, correlated spikes from two presynaptic LGN neurons strongly increase the probability of firing in a postsynaptic primary visual cortex (V1) simple cell (17–19) and ensure the transfer of information from the thalamus to the cortex, despite a low probability of synaptic transmission (3, 20). Our simulations support these results by showing that spike output reliability can be predicted by synchrony magnitude (SM), which is the number of thalamocortical synapses that are simultaneously driven by the same presynaptic thalamic spike train. Simultaneous recordings from more than two LGN neurons would be needed to measure the SM directly.

We compared the output of our model with in vivo recordings from Kara et al. (21), who simultaneously recorded spike trains from retinal ganglion cells, LGN relay cells, and cortical cells in the primary visual pathway of anesthetized cats. The visual stimulus was a drifting grating, which produced patterns of spikes without highly synchronous events, as occurs with flickering visual stimuli (2). The presynaptic spike times from the in vivo recordings of LGN cells were distributed across a varying number of input synapses in the model (Fig. 1, B to D), as well as across an inhibitory feedforward pathway leading to the spiny stellate cell. This pattern was transformed by the synapses into a sequence of neurotransmitter releases (Fig. 1, E to G) and integrated with the cortical background inputs to produce a fluctuating membrane potential (Fig. 1, H to J, and figs. S1 and S2). The average firing rate and the reliability (22) of the cortical cell spike pattern was then computed across 30 repeated 250-ms trials (Fig. 1, K to N), each using a different LGN cell spike pattern from the in vivo recordings (14).

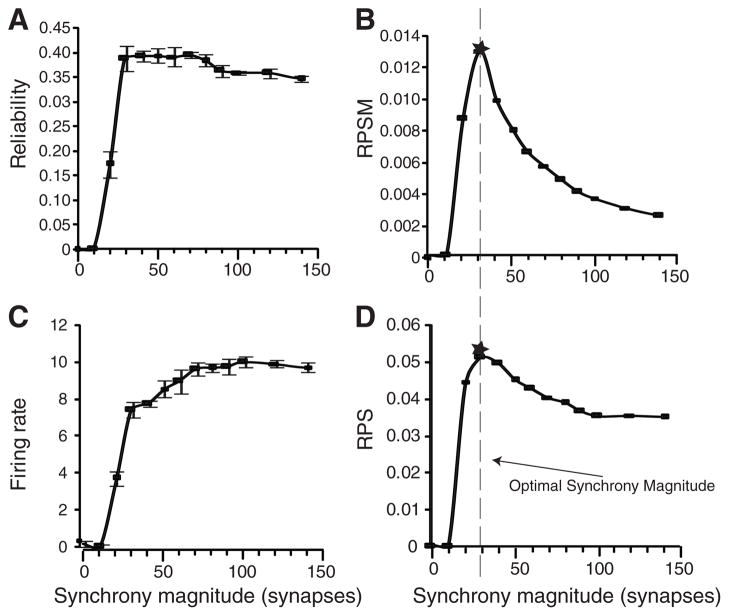

Output reliability was a highly nonlinear function of SM, rising steeply from 20 to a maximum at 40 synapses (Fig. 2A), more rapidly than the output firing rate (Fig. 2C). The reliability-per-SM (RPSM) function, defined by dividing the reliability by the SM, reached an optimal synchrony magnitude (OSM) at approximately 30 synapses (Fig. 2B, dashed line). The reliability-per-spike (RPS) ratio, a measure of the reliability increase for each additional output spike computed by dividing each reliability output by its corresponding firing rate, also peaked at approximately 30 synchronous synapses (Fig. 2D). Similar results were obtained when the synaptic inputs were generated from groups of five synchronous inputs corresponding to single LGN afferents with each group from a different recorded LGN input (fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

Average spike-time reliability, firing rate, and efficiency measures as a function of synchrony magnitude for inputs as described in Fig. 1. Standard deviation bars plotted using data from 10 sets of simulations with 30 independent trials each. (A) Output spike reliability. (B) RPSM has a peak at a synapse synchrony magnitude of 30 (vertical dashed line). (C) Firing rate responses. (D) RPS efficiency (reliability/firing rate) also peaked at 30 synchronous synapses.

In experimental recordings from thalamic and cortical cells, the trial-to-trial spike-count variability was low (21, 23), indicating that the spike rates of these cells conveyed important information about the input stimulus. Using spike trains from LGN recordings as inputs to the model cell (21), we also found low spike-count variability: The Fano factor (FF), defined as the sample variance divided by sample mean, achieved a minimum of 0.2 to 0.4 in the range of 20 to 80 synchronous synapses (fig. S4).

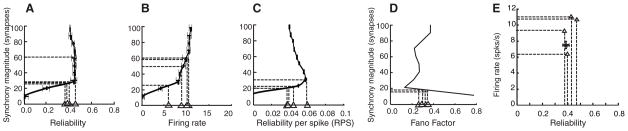

The quantitative analysis of output reliability can be used to predict the number of synchronous inputs that drive cortical cell responses during in vivo behavioral experiments (Fig. 3). We plotted data from in vivo recordings of V1 cells supplied by Kara et al. (21) against the transfer function of input synchrony as a function of output reliability, as determined by our model, to infer synchrony magnitude of the cells in vivo. Each of the four neurons (from different animals) predicted input synchrony in the range of 20 to 60 synchronous synapses (Fig. 3). The reliability and firing rate at the OSM from our model (Fig. 2, stars), using recorded thalamic input spike trains, fall within the observed ranges of the experimental values (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

Predicted input synchrony ranges for in vivo recordings. Graphs from Fig. 2 were inverted to make synchrony magnitude the dependent variable. In each plot, four triangles are positioned along the x axis (input value), corresponding to in vivo experimentally measured values from four separate animals (21), and the inferred output synchrony magnitude is shown as a horizontal dashed line from the first intersection on each curve. Predictions were made based on (A) reliability, (B) firing rates, (C) RPS, and (D) FF (taken from fig. S4C). (E) The predicted firing rate and reliability at SM = 30 (solid circle with error bars indicating SD) is plotted along with the measured values from the four sets of recordings (triangles). Despite the small sample of cells with enough trials, the estimated reliabilities cluster around 0.4.

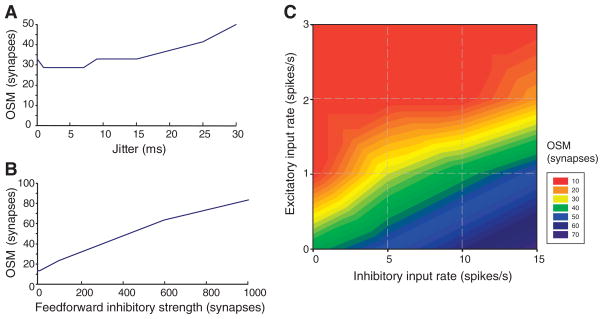

These results were robust to increasing the jitter and varying the strengths of thalamic inputs and feedforward inhibitory synapses (Fig. 4, A and B, and fig. S4). However, the OSM depended on the balance between background excitatory (E) and inhibitory (I) inputs to the 5500 intracortical synapses. When the integrated inputs were balanced (total average excitatory input equal to the total average inhibitory input), the neuron became highly sensitive to correlated fluctuations of the membrane potential, which affected the reliability (23) as well as the gain of the input spike rate to output spike rate curve (24). We varied the cortical background rate and the ratio of inhibitory to excitatory input rates, β = I/E, to assess their influence on the reliability of the synchronous inputs to LGN synapses (Fig. 4C and fig. S3). Background excitatory inputs above 1 spike/s depressed the reliability response by directly competing with the LGN excitatory inputs and introducing high levels of spurious output firing. Increasing the background inhibition also increased the OSM and was therefore a potential mechanism for setting the threshold for synchrony detection. The sensitivity of the cortex to synchronous inputs can be varied over a wide range by regulating β.

Fig. 4.

Effect of input jitter, inhibitory inter-neuron strength, and the balance of inhibitory and excitatory background inputs on the predicted OSM. (A) The jitter of the input event signals was varied from 0 to 30 ms. The default used in Figs. 1 to 3 used jitter = 1 ms. (B) The number of synapses from the feedforward inhibitory inter-neurons was varied from 0 to 1000 synapses. The default used in Figs. 1 to 3 was 200 synapses. (C) The Poisson-distributed presynaptic spike trains for the 4500 excitatory (glutamate) and 1000 inhibitory (γ-aminobutyric acid) intracortical synapses were covaried from 1 to 3 spikes/s excitatory background inputs and 1 to 15 spikes/s inhibitory background inputs. The default in Figs. 1 to 3 was 1 excitatory spike/s and 5 inhibitory spikes/s.

Spiking due to input synchrony may be a way to ensure that important events are registered by the spiny stellate neurons in the cortex, regardless of asynchronously arriving spikes from ongoing cortical computation. This prediction could be tested with intracellular recordings in vivo by using a dynamic clamp (25) to inject somatic conductances reflecting events in the presence of in vivo background noise.

Moving visual inputs give rise to synchronous spikes in retinal ganglion cells (26). A single retinal ganglion cell can drive four or more LGN cells (27), which can make one to eight synapses each (28), with a spiny stellate cell in V1 with overlapping receptive fields (17). Thus, assuming an average of four synapses for each LGN axon and an OSM of 20 to 40, as few as 5 to 10 LGN cells could effectively drive a cortical neuron. This prediction could be tested by studying the effects of modulating the contrast of visual stimuli on the firing rates and reliability of spike timing in cortical cells (21, 29). Cortical feedback to the thalamus could also regulate the degree of synchrony among thalamocortical cells.

We have quantified the number of synchronous thalamic spikes needed to reliably report a major sensory event to cortical neurons (19), which is consistent with previous physiological experiments that found correlated firing with 1-ms precision in visual cortex (4, 17) and mouse barrel cortex (3). Spike synchrony, through converging anatomical pathways, enhances the information transfer rate and speeds up processing (30, 31).

The output spike pattern of a layer 4 neuron is thus determined by the temporal pattern, as well as the rate, of the synchronous thalamic inputs according to the history-dependent dynamics of its synapses acting coherently within 6 to 8 ms. The same analytical methods used here could be applied to study reliability and connectivity in other types of neurons. Spike synchrony, observed throughout the cortex, may also have a more general function in ensuring information transmission between cortical areas (32).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Kara, P. Reinagel, and R. C. Reid for sharing in vivo recordings of simultaneously recorded retinal, thalamic, and cortical neurons. K. Martin provided invaluable anatomical data on thalamocortical connectivity. This research was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the NSF Science of Learning Center SBE-0542013.

Footnotes

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/328/5974/106/DC1

Materials and Methods References

References and Notes

- 1.Salinas E, Sejnowski TJ. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:539. doi: 10.1038/35086012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reinagel P, Reid RC. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5392. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-14-05392.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruno RM, Sakmann B. Science. 2006;312:1622. doi: 10.1126/science.1124593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dan Y, Alonso JM, Usrey WM, Reid RC. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:501. doi: 10.1038/2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reich DS, Mechler F, Purpura KP, Victor JD. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1964. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-01964.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Usrey WM. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12:411. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00339-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumbhani RD, Nolt MJ, Palmer LA. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:2647. doi: 10.1152/jn.00900.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Humphrey DR, Schmidt EM, Thompson WD. Science. 1970;170:758. doi: 10.1126/science.170.3959.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salinas E, Abbott LF. J Comput Neurosci. 1994;1:89. doi: 10.1007/BF00962720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White EL. Cortical Circuits: Synaptic Organization of the Cerebral Cortex—Structure, Function and Theory. Birkhauser; Boston: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peters A, Payne BR. Cereb Cortex. 1993;3:69. doi: 10.1093/cercor/3.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed B, Anderson JC, Douglas RJ, Martin KA, Nelson JC. J Comp Neurol. 1994;341:39. doi: 10.1002/cne.903410105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mainen ZF, Sejnowski TJ. Nature. 1996;382:363. doi: 10.1038/382363a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 15.Usrey WM. Philos Trans R Soc London Ser B. 2002;357:1729. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Usrey WM, Reid RC. Annu Rev Physiol. 1999;61:435. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alonso JM, Usrey WM, Reid RC. Nature. 1996;383:815. doi: 10.1038/383815a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kara P, Reid RC. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8547. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-24-08547.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Usrey WM, Alonso JM, Reid RC. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5461. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-14-05461.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de la Rocha J, Doiron B, Shea-Brown E, Josić K, Reyes A. Nature. 2007;448:802. doi: 10.1038/nature06028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kara P, Reinagel P, Reid RC. Neuron. 2000;27:635. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schreiber S, Whitmer D, Fellous JM, Tiesinga P, Sejnowski TJ. Neurocomputing. 2003;52–54:925. doi: 10.1016/S0925-2312(02)00838-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mainen ZF, Sejnowski TJ. Science. 1995;268:1503. doi: 10.1126/science.7770778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salinas E, Sejnowski TJ. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6193. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06193.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharp AA, O’Neil MB, Abbott LF, Marder E. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69:992. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.3.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chatterjee S, Merwine DK, Amthor FR, Grzywacz NM. Vis Neurosci. 2007;24:827. doi: 10.1017/S0952523807070757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamos JE, Van Horn SC, Raczkowski D, Sherman SM. J Comp Neurol. 1987;259:165. doi: 10.1002/cne.902590202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freund TF, Martin KAC, Whitteridge DJ. Comp Neurol. 1985;242:263. doi: 10.1002/cne.902420208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneidman E, Berry MJ, 2nd, Segev R, Bialek W. Nature. 2006;440:1007. doi: 10.1038/nature04701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Butts DA, et al. Nature. 2007;449:92. doi: 10.1038/nature06105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lesica NA, et al. Neuron. 2007;55:479. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tiesinga P, Fellous JM, Sejnowski TJ. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:97. doi: 10.1038/nrn2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.