Abstract

Synthetic in vivo molecular ‘computers’ could rewire biological processes by establishing programmable, non-native pathways between molecular signals and biological responses. Multiple molecular computer prototypes have been shown to work in simple buffered solutions. Many of those prototypes were made of DNA strands and performed computations using cycles of annealing-digestion or strand displacement. We have previously introduced RNA interference (RNAi)-based computing as a way of implementing complex molecular logic in vivo. Because it also relies on nucleic acids for its operation, RNAi computing could benefit from the tools developed for DNA systems. However, these tools must be harnessed to produce bioactive components and be adapted for harsh operating environments that reflect in vivo conditions. In a step toward this goal, we report the construction and implementation of biosensors that ‘transduce’ mRNA levels into bioactive, small interfering RNA molecules via RNA strand exchange in a cell-free Drosophila embryo lysate, a step beyond simple buffered environments. We further integrate the sensors with our RNAi ‘computational’ module to evaluate two-input logic functions on mRNA concentrations. Our results show how RNA strand exchange can expand the utility of RNAi computing and point toward the possibility of using strand exchange in a native biological setting.

INTRODUCTION

Research in molecular computing has pursued two complementary paths: solving the so-called ‘NP-hard’ computational problems (1–7), and building autonomous molecular computers—synthetic, layered information-processing networks—that could potentially operate in vivo (8–14). The top sensory layer in these networks is composed of biosensor devices that interact with external molecular signals. Each biosensor is a small circuit that transduces a specific input signal into a prescribed output according to a pre-programmed input–output relation. The nature of the outputs is normally dictated by the design of the downstream computational layer, which accepts the sensors’ outputs as immediate inputs and integrates them in a programmed fashion to produce a desired biological outcome. In other words, the outputs produced by the sensors are analogous to voltages that serve as immediate inputs to silicon-based computers.

The pursuit for in vivo computers is motivated by the tasks they could execute in single cells and organisms. Although molecular ‘computations’, both digital and analog, are already performed by natural cellular pathways such as transcriptional networks (15), those pathways are highly evolved to execute particular tasks using specific inputs and outputs. It is often desirable to be able to specify a new pathway in an artificial biological network in terms of its inputs, outputs and their relation. For example, such artificial systems in individual cells could control the release of ‘smart drugs’ (10) based on programmed analysis of specific intracellular disease-markers. Furthermore, cells augmented with synthetic information-processing networks could drive tissue formation, as has already been shown with pattern-generating cells (16). In these and other examples (17–27), the artificial networks were inspired by natural systems. However, natural systems may not directly guide the construction of artificial networks, because natural systems have evolved to specialize in their current functions. Therefore, a comprehensive rational design framework is required to enable rapid construction of ‘computational’ networks to specifications. One specification is the chemical character of the inputs to the network. For example, in nature, most receptors respond to only a few specific ligands, but it could be very useful if a sensor could be constructed for any molecule of a specific class (e.g. protein, mRNA or a small chemical) using rational design. Indeed, there are no natural sensors for most mRNA transcripts or proteins. Another specification is the exact link between the inputs and the outputs. This includes the definition of specific input combinations that should trigger the output, or a requirement for a specific temporal order, or certain concentration thresholds.

Nucleic acid inputs and mRNA transcripts in particular have long been a focus of research in biocomputing. The amount of mRNA in a cell often correlates with the amount of the protein it encodes. As a result, mRNA levels provide information about not only the phenotype of the cell, but also about changes in cell physiology in response to developmental processes, environmental stresses or disease. Probing multiple transcripts in order to produce a bioactive response could lead to a diverse and highly useful family of applications: generating an engineered action in the biological system only under precisely defined circumstances or conditions. In our particular case those circumstances will manifest themselves as a complex gene-expression profile reflected in mRNA levels. The condition that would trigger a response could be, among others, a malignant transformation, specific developmental stage or environmental perturbation. The response of the computing circuit would be activation of a drug, expression of a fluorescent reporter or induction of a desired downstream pathway, respectively. Accordingly, previous studies have demonstrated synthetic biocomputing networks that contained sensors for a variety of nucleic acid inputs such as DNA oligonucleotides (9), mRNAs (10) and microRNA (miRNA) molecules (11). However, those sensors were embedded in biocomputing systems that operated in carefully formulated buffer solutions. Comparable approaches that sense mRNA levels in cells include molecular beacons (28) that emit fluorescent output in response to high mRNA concentrations, but they are strictly single input–single output detectors that cannot link multiple mRNA inputs to physiological outputs. Another approach utilizes a fluorescent reporter fused to mRNA-binding motifs (29), but this requires that the mRNA in question be tagged with multiple repeats of the nucleic acid sequence that binds this protein. The latter approach has been useful in single-molecule mRNA studies but, similar to molecular beacons, it generates fluorescent output and furthermore may not be used to detect unmodified endogenous transcripts. In contrast to these approaches, processes of strand annealing and migration employed in biocomputing networks and other nucleic acid devices (9–11,30–32) could be incorporated in sensors to generate outputs that could be further integrated in computational modules and generate responses to multiple inputs. Typically, the devices include partially double-stranded DNA fragments with single-stranded ‘toeholds’. While stable, those structures can react with other DNA or RNA species that are complementary to the toehold and the rest of the toehold-containing strand. The initial hybridization to the toehold leads to rapid displacement of the originally hybridized strand via strand migration (33), leading to a single-stranded fragment that can participate in downstream processes with similarly designed substrates generating, at times, highly complex behaviors. We call this approach the ‘annealing and migration’ paradigm. Here, we asked if this paradigm is viable in a setting that better represents the environment of a cell cytoplasm, where such networks are eventually intended to operate.

Previously, we reported an RNAi-based computation module (23). This module provides a unique test-bed to study whether the ‘annealing and migration’ paradigm can indeed step beyond simple buffer solutions, because the module functions in live cells or certain cell-free extracts but not in simple buffers. The computation module also prescribes what a sensor should do—convert an mRNA strand present in high concentration into an siRNA molecule. In other words, a sensor must generate siRNA in response to an mRNA in either cell-free extract or cytoplasm. We note that chemical inputs have been converted into siRNA before. Small molecules were shown to affect siRNA and shRNA activity in vitro and in vivo (34–37), and more recently a short RNA oligo served as a trigger to produce a functional siRNA in a simple buffer that, when transfected into the cells, was found to repress a target gene (38). However, full-length mRNA transcripts have never been used to trigger functional siRNA either in simple buffers, cell extracts or cells.

We chose the cell-free extract as a milieu for our proof-of-concept experiments, since the extract allows a level of control that is impossible to achieve in live cells, and yet it retains many properties of the cytoplasm. Specifically, we used a well-established Drosophila embryo lysate system (39). To this end, we formulated novel empirical rules for rational ‘annealing and migration’-based design of biosensor devices that transduce mRNA levels into siRNA molecules, and we constructed biosensors for four different mRNA species. Two of these sensors were shown to operate in the lysate after a series of chemical modifications and extensive structural optimization. The biosensors were then combined with the computation module, and the fully assembled system was able to evaluate logic expressions using mRNA levels as inputs. Our results suggest that RNAi-based molecular computation is a viable approach for conducting complex signal processing, and it represents a valuable addition to the existing repertoire of molecular computing devices.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The 42- or 43-nt trigger-sequence motifs were selected in the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of the signal mRNA with the sequence pattern 5′-N110-N24-N35-6-N42-3-N55-6-N64-N72-N810-3′. N1, N2, … N8 represent different subsequences within the motif, and the subscripts denote their lengths. The empirically determined constraints on those subsequences are as follows (i) N24 should be AU-rich while N64 should be GC-rich, creating the thermodynamic asymmetry required for specific RISC incorporation of the [Sense:Antisense (S:As)] duplex (40); (ii) N110 and N810 are 10-nt nucleation sequences with approximately 50% GC content; (iii) the GC content of the combined N24-N35-6-N55-6-N64-N72 sequence is 45–55% to ensure that the S:As is active in the RNAi pathway (40); (iv) a 2- or 3-nt bulge N4 is included to accelerate the strand exchange reaction; (v) the N72, a 3′ overhang of the As strand in S:As, should be GC-rich to reduce the background exchange.

Equimolar amounts of purified Pr and As strands were annealed in 1× lysis buffer (100 mM KOAc, 30 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.5, 2 mM Mg(OAc)2, 5 mM dithiothreitol) and 1 U/µl Superase-In (Ambion). Annealed duplexes [Protecting:Antisense (Pr:As)] were purified using 15% native PAGE, dissolved in 1×lysis buffer, and stored at −80°C. Signal and target RNA transcripts were in vitro transcribed. Strand-displacement reactions were assembled on ice before incubation at 25°C or 37°C. In kinetics experiments, biosensor devices were assembled using Pr strand with 2′-O-methyl modification (mP), As strand with fluorescein at the 3′-terminus and S strand with carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) at the 5′ terminus. The Drosophila embryo lysate was prepared as previously described (41). In lysate experiments, mP strands and unmodified S and As strands were used to assemble each biosensor device that includes annealed Pr:As and 1.5× amount of S. The biosensors’ operation in lysate was monitored by in vitro RNAi assays as described previously (42). Biosensor devices operated in lysate in a two-step manner (Figure 5) or a one-step manner (Figure 4). In the two-step manner, a 3-µl mixture of biosensor devices and signal RNAs in 1× lysis buffer was incubated at 25°C for 10 min before adding a 7-µl mixture of lysate, target RNAs and reaction buffer. In the one-step manner, a biosensor device was added to a 7-µl mixture of lysate, target RNAs and reaction buffer, followed by immediate addition of signal RNA. Equal aliquots of the corresponding S strand were added five additional times at 5-min intervals to compensate for the loss of S strand due to degradation by nucleases in the lysate. Additional methods details and sequences of RNA and DNA oligonucleotides, PCR primers, etc., are provided in the Supplementary Data.

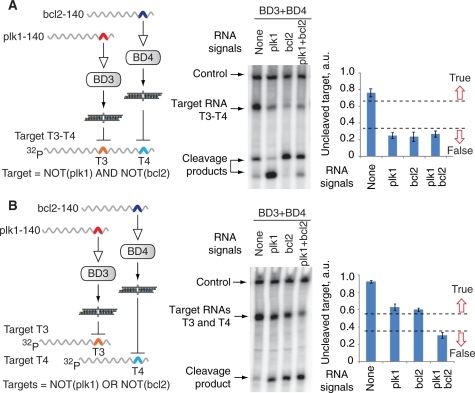

Figure 5.

Logic computations on mRNA signals in Drosophila embryo lysate. A 3-µl mixture of biosensor devices and signal RNAs or mock RNAs in 1× lysis buffer was incubated at 25°C for 10 min before adding a 7-µl mixture containing 5-µl lysate and target RNAs. The mixture was then incubated at 25°C for 2 h. (A) The ‘AND’ gate between bcl2 and plk1 signals computed in a two-step manner. Final reaction contains 5-nM T3–T4 target RNA, 30-nM BD3 and/or 25-nM BD4, 0.5-µM signal RNAs or mock RNAs. Left panel, the schematics of the circuit and the logic formula it computes. Middle panel, denaturing gel electrophoresis analysis of the circuit’s function with different combinations of signals. Right panel, quantified amounts of uncleaved target RNA normalized to the control radiolabeled RNA in the sample (mean ± SD). High and low amounts represent the circuit’s True and False logic outputs, respectively. The True/False separation is a qualitative illustration of the gate’s performance under observed sample-to-sample variability. (B) The ‘OR’ gate integration of bcl2 and plk1 signals. Final reaction contains 3-nM T3 target RNA, 3-nM T4 target RNA, 50-nM BD3 and/or 15-nM BD4, 0.5-µM signal RNAs or mock RNAs. Left, middle and right panels are as in (A).

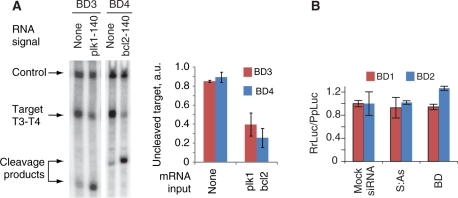

Figure 4.

The operation of biosensor devices in the Drosophila embryo lysate. (A) Autonomous operation of individual biosensors in lysate; 0.5 µl of 2-µM Pr3:As3 or 1-µM Pr4:As4 was added to a 7-µl mixture containing 5-µl lysate and ∼5-nM target RNAs, followed by immediate addition of 0.5 µl of 10-µM plk1-140nt or bcl2-140nt and 0.5 µl of 1-µM S3 or 0.5-µM S4, respectively. Equal aliquots of the corresponding S strand were added five additional times at 5-min intervals to compensate for the loss of S strand due to degradation by nucleases in the lysate. The mixture was additionally incubated at 25°C for 2 h. Cleavage of the target indicates the generation of the siRNA output, as expected in the presence of signal. Left panel, denaturing gel electrophoresis of the reaction mixture. Right panel, the quantified amount of the uncleaved target as measured in three replicates. (B) The assessment of the biosensor-induced perturbation of the mRNA signal. Full-length mRNA signals (100 nM RrLuc-Sig1 or RrLuc-Sig2) were incubated with 25 nM mock siRNA, 25 nM S:As siRNA outputs of their cognate biosensors or 25 nM biosensors themselves and then incubated in the Drosophila embryo lysate at 25°C for 2 h. The chart shows the relative translation of RrLuc-Sig1 and RrLuc-Sig2 as measured by the dual-luciferase assay (mean ± SD).

RESULTS

Biosensor design rules

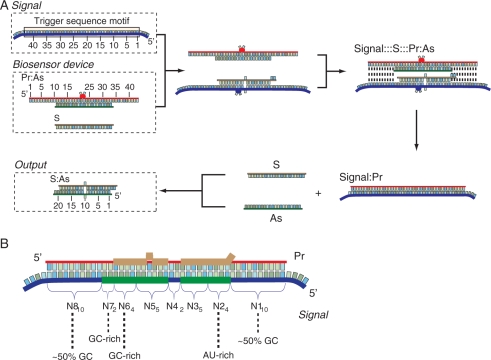

Earlier we described an in vivo Boolean evaluator that is capable in principle of executing any arbitrary logic calculation in mammalian cells (23). A central feature of the evaluator is using regulation by RNA interference to perform signal integration. Therefore, the evaluator requires that any input signal be converted, or transduced, into small interfering RNA (siRNA) ‘mediator’ prior to integration. The state of a signal (On/True or Off/False) is therefore reflected in its mediator siRNA (Supplementary Figure S1), and multiple siRNA mediators are in turn logically integrated in the downstream gene network to elicit a single On/Off response. Here we propose how to design a molecular biosensor ‘device’ that receives an mRNA signal as input and produces an siRNA molecule as output. The mechanistic details of our approach (Figure 1A and B, Supplementary Table S1) are inspired by previously reported nucleic acid ‘devices’ (8,10–12,30,32,43–46). The base composition of the biosensor (Figure 1B) is derived from a short ‘trigger-sequence motif’ ∼43-nt long found in its cognate mRNA signal, which triggers the sensing process. The device (Figure 1A, left) consists of a partially double-stranded RNA duplex denoted as Pr:As and a single-stranded RNA molecule denoted as S (Sense). The Pr strand is complementary to the trigger-sequence motif, while the As strand is complementary to the central half of the Pr strand, leaving two 10-nt single-stranded overhangs. In the presence of the signal, the two 10-nt overhangs in the Pr strand hybridize to the complementary single-stranded (ss) RNA sequences in the trigger-sequence motif, initiating strand exchange and thus displacement of the As strand. The single-stranded As molecule is then free to hybridize to the complementary S strand, forming a functional siRNA (S:As). In the absence of the mRNA signal, the device is generally stable and no siRNA is generated, although some background-exchange process occurs with the As strand migrating to the S strand (see below). Initially, the S strand may partially hybridize to the trigger-sequence motif, but it does not block the nucleation sequences and also becomes displaced during the exchange process.

Figure 1.

The design of the biosensor device for mRNA signal and the signal transduction process. (A) Mechanism of action. The mRNA signal contains a ‘trigger-sequence motif’ 43-nt long. The biosensor device consists of a ‘protecting’ (Pr) strand pre-annealed to an ‘antisense’ (As) strand, along with a single ‘sense’ (S) strand. The Pr strand is a chemically modified (Supplementary Table S1) ribooligonucleotide fully complementary to the trigger-sequence motif. The As strand is complementary to the nucleotides 11, …, 20 and 23, …, 33 of the Pr strand, generating a 2-nt ‘bulge’ in the Pr:As duplex. This bulge serves to accelerate the sensing process and can also be 3-nt long (Supplementary Figure S4B). The Pr:As duplex has two 10-nt single-stranded overhangs, which serve as nucleation sequences during its interaction with the trigger-sequence motif. The S-strand RNA contains, starting from its 3′-terminus, two unpaired nucleotides, a segment complementary to the nucleotides 1, …, 9 of the As strand, one unpaired nucleotide and another segment complementary to the nucleotides 11, …, 19 of the As strand. During the interaction between the signal and the biosensor, the Pr strand migrates over to the trigger-sequence motif, and the released As strand hybridizes with the single-stranded S strand to form a canonical siRNA duplex S:As with a single-nucleotide mismatch that is not detrimental to RNAi efficiency (58) but serves to modulate the energy balance of the process. (B) The anatomy of the trigger motif and the biosensor device. Blue strand is the input and red strand is the fully complementary Pr. The requirements from various subsequences of the trigger motif are indicated. The bases of the trigger motif that serve to form an As strand are highlighted in green, and the bases of the Pr strand that form the S strand are shown in brown.

Biosensor construction and initial testing

We constructed four biosensor devices: BD1 and BD2, which sense two synthetic transcripts (Sig1 and Sig2, respectively), and BD3 and BD4, which sense truncated variants of two endogenous mRNA transcripts (plk1 and bcl2, respectively, Supplementary Table S1). The two synthetic transcripts (Sig1 and Sig2) were constructed by subcloning artificially designed trigger-sequence motifs into the 3′-UTR of the Renilla luciferase gene. The cDNA of plk1 and bcl2, often over-expressed in cancer cells (47,48), were used to generate the truncated variants of the endogenous transcripts. We chose trigger-sequence motifs in the 3′-UTR of the signals such that they did not overlap with known functional sequences because we reasoned that the hybridization of the Pr strand to this region will neither inhibit proper translation of the mRNA nor interfere with mRNA metabolism. Specifically, potential interference with the signal mRNA can come from three sources: (i) hybridization of the single-stranded S strand prior to strand exchange; (ii) binding of the Pr strand in the process of sensing and (iii) RNAi against the signal elicited by the formed S:As duplex. Generally speaking, neither of these processes should interfere with the signal. The consequences of an interaction similar to that of the S or the Pr strands with the signal mRNA have been extensively investigated. In vivo studies concluded that individual RNA strands do little to inhibit gene expression (49) while, in rare cases where such activity was observed, it was linked to RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and highly specialized experimental conditions (50). RdRp-dependent silencing has not been observed in mammalian cells which are the intended milieu for the next generation of our sensors (51), and in any case such activity can be abolished by chemical modification on the oligonucleotide (50). A thorough in vitro study (52) showed that single-stranded components of an siRNA are generally inactive and only trigger mild degradation of the target when phosphorylated at their 5′-end. The fully assembled S:As duplex might trigger RNAi against the target if both strands are equally loaded into the RISC complex. Here we utilized the asymmetry of siRNA duplexes (53) to ensure that only the As strand is selected by introducing high AU content into the four rightmost base pairs in the siRNA duplex and high CG content in the four leftmost base pairs. Ultimately, we experimentally verified our expectations by directly measuring the effect of the sensor on the signal mRNA (see below, Figure 4B and Supplementary Figure S10) and showed that there is no significant effect on the signal’s proper function.

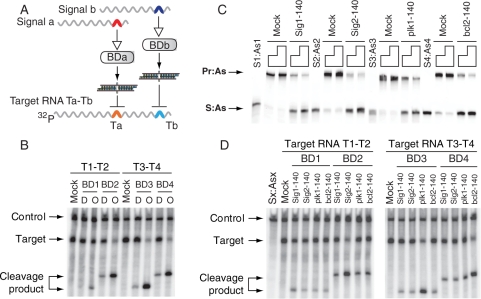

We first confirmed that, in the absence of mRNA signals, the biosensor devices (Pr:As + S) and their predicted outputs (S:As) were inactive and active, respectively, in the RNAi pathway. We showed this by incubating both species with their intended target RNA strands that contain a sequence recognized by the S:As siRNA outputs (‘Target RNAs’ in Figure 2A that correspond to ‘computational RNAs’ from Supplementary Figure S1 without a coding sequence) in Drosophila embryo lysate. Figure 2B shows that, while there is some background target cleavage, the RNAi activity of the intended output molecules is much stronger. Second, we showed that the devices produce the desired siRNA output upon interaction with the RNA signal containing the corresponding trigger-sequence motif in buffer (Figure 2C). Next, we confirmed the RNAi activity of the biosensor-generated outputs by incubating these mixtures with the target RNAs in the lysate (Figure 2D). The same gel also shows that the devices are selective toward their intended signals and do not interact with scrambled (Mock; Figure 2C) and unintended signals.

Figure 2.

Basic features and properties of biosensor device. (A) The molecular components used in (B), (C) and (D); BDa and BDb stand for either BD1 and BD2 (biosensors for Sig1 and Sig2, respectively), or BD3 and BD4 (biosensors for plk1 and bcl2 signals, respectively). Colored arches in signals represent trigger-sequence motifs in their 3′-UTR; colored arches in the target RNA represent target sequences (Ta or Tb) for the corresponding S:As siRNA outputs. Target RNAs used in the cleavage assay were cap-labeled by 32P-GTP (Supplementary Methods). (B) The activities of the biosensor devices ‘D’ and their predicted siRNA outputs ‘O’ as analyzed by RNA cleavage assay in the Drosophila embryo lysate. Target RNA T1–T2 was used for BD1 and BD2, and target RNA T3–T4 was used for BD3 and BD4; control, a 600-nt control RNA (CK600nt) was used to normalize the loading of samples in each lane; mock, nonspecific siRNA. (C) Biosensor devices in which the As strands were labeled with fluorescein at the 3′ terminus were incubated with excess molar amounts (4× or 8×) of 140-nt scrambled RNA (Mock) or 140-nt signal RNA at 25°C for 1 h. Samples were analyzed by native polyacrylamide gel. (D) Testing the specificity of the biosensor devices in the Drosophila embryo lysate. Different biosensors were incubated with their cognate and non-cognate signals. Sx:Asx, the mixture of S1:As1, S2:As2, S3:As3 and S4:As4; mock, non-specific siRNA.

Measurements of biosensors’ kinetic properties

The operation of the device depends on the rapid and specific generation of the output siRNA and the efficient participation of this siRNA in the RNAi pathway. Since the latter aspect has been well studied (54), we set out to elucidate factors affecting the kinetics of siRNA generation. The measurements were taken using a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based assay (‘Materials and methods’ section and Supplementary Methods). We verified that siRNA generation is first order in both the input mRNA signal and in the Pr:As duplex until 50–70% completion (See sections ‘Calculation of strand displacement rates’ and ‘Estimation of the background exchange rates’, as well as Supplementary Figure S3 in the Supplementary Data), and that the strand exchange, rather than annealing between S and As strands, is the rate-limiting step (Supplementary Figure S3). We then used an integrated kinetics equation to calculate the rate constants (Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Figure S3).

To gauge the effect of the overhang length in the Pr strand, we constructed variants of biosensors BD1 and BD2 that contained either 5-, 10-, 15- or 20-nt overhangs (Supplementary Table S2). We found that the 10-nt overhangs enabled the fastest exchange, while both shorter and longer overhangs reduced siRNA production (Supplementary Figure S4A). The bulge in the middle of the Pr:As duplex accelerated the output production by ∼3.5-fold, while increasing the background exchange only by ∼2-fold (Supplementary Figure S4B). Remarkably, stabilizing the Pr strand with 2′-O-methyl modifications increased the signal-to-background ratio, since it reduced the background rates to those observed with no bulge, without affecting the rate of signal-triggered siRNA formation (Supplementary Figure S4B).

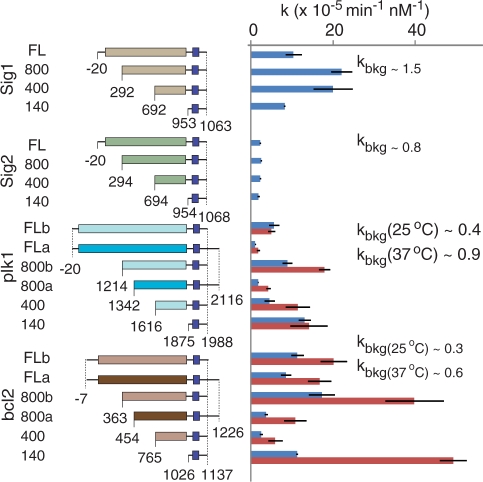

The effects of mRNA signal length and trigger-sequence motif placement were assessed by comparing the full-length (FL) signals with their 140-, 400- and 800-nt long truncated variants in the exchange process (Figure 3). In versions ‘a’ and ‘b’ of signal mRNAs, the overall length was exactly or almost exactly preserved, but the 5′- and 3′-termini were shifted, changing the placement of the trigger-sequence motif relative to the 3′-terminus. As shown in Figure 3, the background-corrected rate constants range from 10−5 min−1nM−1 to 2 × 10−4 min−1 nM−1 at 25°C and from 2 × 10−5 min−1 nM−1 to 5 × 10−4 min−1nM−1 at 37°C, with their values doubling on average as the temperature increased from 25 to 37°C. The ratios of signal-induced to background-exchange rates varied across different biosensors from 2 to 57 at 25°C with a mean of 16, and from 2 to 81 at 37°C with a mean of 25 (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S5). In addition, increasing the distance between the trigger-sequence motif and the signal’s 3′-terminus reduced the rate constants (compare ‘a’ and ‘b’ versions of plk1-FL, plk1-800, bcl2-FL and bcl2-800 signals in Figure 3). Since signal length per se did not correlate with the kinetic parameters, we checked whether fine details of the secondary structure or the energy balance of exchange intermediates can explain the observations. Among the various parameters, only the overall free energy of the exchange processes (Supplementary Figure S6 and Supplementary Table S3) appeared to have a non-linear correlation with the rate constants, although more experiments are needed to confirm this observation.

Figure 3.

The effects of mRNA signal variants on biosensor switching. Cumulative summary of the rate constants measured with varying lengths of RNA signals, varying positioning of the trigger-sequence motifs (versions ‘a’ and ‘b’) and different temperatures (25°C, blue bars, and 37°C, red bars). Background-exchange rate constants in comparable units are indicated. Different rectangle colors represent different coding sequences, and different hues of the same color (e.g. light versus dark brown) indicate transcripts with varying positioning of the trigger motif but identical coding sequence. Dark blue squares indicate trigger-sequence motifs. The numbers denote nucleotide coordinates relative to the translational start site. In addition to features shown in the figure, all transcripts include A25 tails at their 3′ termini. Error bars are ± SD of three independent replicates.

To test the sensitivity of the biosensors, we monitored the generation of siRNA output at low, equimolar concentrations of signal mRNA and biosensor by the FRET-based assay at 37°C. We show the results of bcl2-140 and BD4 as an example in Supplementary Figure S7. The strand exchange slowed down when concentrations of bcl2-140 and BD4 decreased from 50 to 3 nM (Supplementary Figure S7A) in accordance with the second-order kinetics of the process. Measurements at low signal and biosensor concentrations help us anticipate the performance of the biosensor under in vivo conditions. For example, with the highest measured rate constant of 5 × 10−4 min−1 nM−1, it will take ∼100 min for a signal mRNA at a physiological concentration of 1 nM to generate 0.5 nM of the siRNA output, when 10 nM of the biosensor components are present. This amount of siRNA should be enough to elicit strong knockdown of the target RNA in the cell, since the total concentration of the RISC complex in mammalian cells (55) is estimated at ∼3 nM. Indeed, we detected strand exchange when reactions were performed using 3 and 1 nM of the signal (bcl2-140) and the biosensor (BD4) at 37°C (Supplementary Figure S7B). However, the background exchange is clearly an obstacle at low signal and sensor concentrations (Supplementary Figure S7B); in the current design, the free energy balance of this exchange is slightly negative due to the favorable intramolecular folding and homo-dimerization of the single-stranded Pr strand (Supplementary Table S4), so the barrier is mainly kinetic. One potential strategy that could improve the operation of the devices at low mRNA concentrations is to also make the background exchange thermodynamically unfavorable.

Testing of fully assembled systems in Drosophila embryo lysate

The delineation of the kinetics parameters primed us for testing the end-to-end operation of the biosensor devices in the lysate, that is, the transduction of the mRNA signal through the device to a target RNA. Drosophila embryo lysate represents a well-controlled model of the cytoplasm in which all the components of the synthetic system can be added in their final forms at known concentrations. However, some of its features are different from those of the mammalian cytoplasm, including: the need for high siRNA load of 10–25 nM to elicit efficient RNAi response (Supplementary Figure S8), the short lifetime of the RNAi machinery, the working temperature of 25°C and, most importantly, the low tolerance for stabilizing modifications in the siRNA backbone (42). Therefore, while Pr strands with 2′-O-methyl modifications were used to increase its resistance to nucleases, S and As strands were kept unmodified in lysate (56). The As strand bound to the modified Pr strand, however, was protected from degradation, and it remained stable during the short time window between its displacement from the Pr:As duplex and its hybridization to the S strand. On the other hand, lifetime of unmodified S strand in lysate was only a few minutes (Supplementary Figure S9). Therefore, S strand had to be replenished in the lysate at 5-min intervals to compensate for its continuous degradation. (In the lysate, siRNA activity is significantly reduced by chemical modifications in the constituent strands and hence those are hard to stabilize, while in mammalian cells modifications are well tolerated and could be used for the next generation of the sensors in vivo).

Taking the above constraints into consideration, we tested the devices BD3 and BD4 by incubating them with their target RNA and either with or without their cognate signal RNAs in lysate. As expected, both the interaction with the signal to produce the siRNA output, and the cleavage of the target RNA by this output in the RNAi pathway occurred autonomously (Figure 4A). We also tested if the devices perturb the input signals by measuring the level of luciferase translated from the two synthetic signals, Sig1 and Sig2, in the presence of the biosensors. As shown in Figure 4B, no obvious effect was detected, demonstrating that neither binding of the Pr strand to the trigger-sequence motif in these signals nor the formation of the S:As siRNA duplex affects the primary function of the mRNA signal–protein expression. We additionally confirmed that even high excess of the Pr strand bound to the signal mRNA does not alter protein expression. In our experiments only 100-fold excess, but not 10-fold excess, led to a moderate 25% drop in expression (Supplementary Figure S10). However, under typical working conditions the signal is used in excess, making the above ratios an unlikely scenario.

We further wanted to determine if the devices could be integrated in larger circuits (Supplementary Figure S1). The logic function computed by the evaluator depends on the placement of siRNA targets in the 3′-UTR of ‘computational genes’. With two working devices that implement a directly proportional relation between the signal and the siRNA output, and two siRNA targets, there are two possible functions: (i) NOT (Signal 1) AND NOT (Signal 2), when the targets for the siRNA outputs are placed in the same UTR (Figure 5A, left panel); and (ii) NOT (Signal 1) OR NOT (Signal 2), when the targets are placed in different UTRs (Figure 5B, left panel). Gate operation was monitored by measuring the uncleaved fraction of targets in lysate. The NOT-AND-NOT (NOR) gate that integrated two signals operated as expected, with a True/False output ratio of about 4:1 that is similar to the True/False ratio of the single biosensor (Figure 5A). The NOT-OR-NOT (NAND) gate exhibited the anticipated analog behavior, due to the fact that each target RNA (T3 or T4) is cleaved separately (Figure 5B). As previously discussed (23), there are a number of ways to make this a perfect ‘NAND’ gate, for example by saturating the downstream response by at least one unrepressed computational gene.

DISCUSSION

Here, we have shown that RNAi-based molecular computation systems (‘RNAi computers’) can be used, at least in cell-free extracts, to logically integrate messenger RNA signals. These systems were mainly inspired by previously published DNA-based devices capable of similar high-level function (10). Earlier devices used strand-exchange processes between RNA input signals or their DNA mimics and DNA-based components (‘transition molecules’) to sense an input state. An iterative process of annealing and enzyme-catalyzed cleavage of another DNA component (‘diagnostic molecule’) would then execute a finite-state computation. Those devices were shown to work in carefully formulated buffer solution where the strand exchange, the annealing and the cleavage proceeded efficiently. However, the devices’ compatibility with biological surroundings, such as the cytoplasm of a live cell, has remained an open question.

While the conceptual framework of the current RNAi-based system draws on those earlier ideas, it recasts them into a radically different implementation. For example, the DNA-based transition molecules that were previously used to sense the inputs and drive the computation are replaced here with siRNA mediators. The cycles of annealing and cleavage are replaced by the simultaneous binding to and cleavage of the target RNA by RISC loaded with various siRNA mediators. In both cases, the mechanism by which an mRNA input signal is transduced into a transition molecule or an siRNA mediator is based on strand-exchange processes. As a result, the combination of all these changes and adaptations—using RNA as the sole building material of the new system, using RNAi as the underlying biological mechanism to execute signal integration, using siRNA to relay the signals to the logic core—specifically address the issues of biocompatibility and show the promise of our current approach in realistic biological settings.

It is noteworthy that the observed rate constants of the siRNA output production are one to two orders of magnitude lower than those measured with model DNA strand-exchange substrates (57). However, it is nontrivial to draw direct comparison between the systems due to the simpler structure of the DNA substrates used for measurement. Our shortest trigger was still much longer than a typical DNA strand used to trigger displacement, and secondary structures could contribute to slow initial complex formation. Potentially useful insight could be obtained by constructing fully DNA-based analogs of our systems and comparing their kinetics. In addition, the absence of a simple correlation between the structure and the rate constants calls for more thorough investigation of RNA-based devices, along with RNA and DNA strand migration in complex arrangements.

The transition of this approach into in vivo systems should be multi-pronged. On one hand, stability issues may be less prominent because all strands of the biosensor could be stabilized with appropriate chemical modifications without impairing their activity in the RNAi pathway (56). Yet chemical modifications may alter the kinetics of the process, and they should be thoroughly investigated. On the other hand, the detection limit of the sensing should be improved by about an order of magnitude to rapidly probe endogenous transcripts. This may require concerted effort to gain better mechanistic insight into the functioning of such biodevices. Another promising approach is to genetically encode the components of the sensor and express them from DNA templates. This will better integrate the devices with the rest of the cellular processes. However, such encoding is far from trivial and will probably require significant alteration of the current design. Overall, the implementation of our ideas in mammalian cells is challenging, but it will be greatly facilitated by the data we gathered in our current study.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Bauer Fellows program and National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIIGMS; grants GM068763-01 and GM068763 for National Centers for Systems Biology). S.J.L was supported by the Harvard College Research Program (HCRP) and Harvard’s Program for Research in Science and Engineering (PRISE). Funding for open access charge: National Institute of General Medical Sciences Center grant for Centers of Systems Biology.

Conflict of interest statement. US patent application as pending.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank D. Schwarz, D. Duplissa, K. V. Myrick and W. Gelbart for help with the Drosophila facility and lysate preparation, and C. Reardon and C. Daly for technical assistance. We thank M. Leisner, J. Lohmueller, J. Schmid-Burgk and I. Benenson for help with the manuscript, and A. Murray, E. O’Shea, B. Stern and members of FAS CSB community for discussions. We thank anonymous referees for insightful comments and suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adleman LM. Molecular computation of solutions to combinatorial problems. Science. 1994;266:1021–1024. doi: 10.1126/science.7973651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipton RJ. DNA solution of hard computational problems. Science. 1995;268:542–545. doi: 10.1126/science.7725098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ouyang Q, Kaplan PD, Liu SM, Libchaber A. DNA solution of the maximal clique problem. Science. 1997;278:446–449. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winfree E, Liu FR, Wenzler LA, Seeman NC. Design and self-assembly of two-dimensional DNA crystals. Nature. 1998;394:539–544. doi: 10.1038/28998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reif JH. Parallel biomolecular computation: Models and simulations. Algorithmica. 1999;25:142–175. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faulhammer D, Cukras AR, Lipton RJ, Landweber LF. Molecular computation: RNA solutions to chess problems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:1385–1389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Head T, Rozenberg G, Bladergroen RS, Breek CKD, Lommerse PHM, Spaink HP. Computing with DNA by operating on plasmids. Biosystems. 2000;57:87–93. doi: 10.1016/s0303-2647(00)00091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benenson Y, Paz-Elizur T, Adar R, Keinan E, Livneh Z, Shapiro E. Programmable and autonomous computing machine made of biomolecules. Nature. 2001;414:430–434. doi: 10.1038/35106533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stojanovic MN, Stefanovic D. A deoxyribozyme-based molecular automaton. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:1069–1074. doi: 10.1038/nbt862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benenson Y, Gil B, Ben-Dor U, Adar R, Shapiro E. An autonomous molecular computer for logical control of gene expression. Nature. 2004;429:423–429. doi: 10.1038/nature02551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seelig G, Soloveichik D, Zhang DY, Winfree E. Enzyme-free nucleic acid logic circuits. Science. 2006;314:1585–1588. doi: 10.1126/science.1132493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakamoto K, Gouzu H, Komiya K, Kiga D, Yokoyama S, Yokomori T, Hagiya M. Molecular computation by DNA hairpin formation. Science. 2000;288:1223–1226. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5469.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Komiya K, Sakamoto K, Kameda A, Yamamoto M, Ohuchi A, Kiga D, Yokoyama S, Hagiya M. DNA polymerase programmed with a hairpin DNA incorporates a multiple-instruction architecture into molecular computing. Biosystems. 2006;83:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mao CD, LaBean TH, Reif JH, Seeman NC. Logical computation using algorithmic self-assembly of DNA triple-crossover molecules. Nature. 2000;407:493–496. doi: 10.1038/35035038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayo AE, Setty Y, Shavit S, Zaslaver A, Alon U. Plasticity of the cis-regulatory input function of a gene. Plos Biol. 2006;4:555–561. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basu S, Gerchman Y, Collins CH, Arnold FH, Weiss R. A synthetic multicellular system for programmed pattern formation. Nature. 2005;434:1130–1134. doi: 10.1038/nature03461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiss R, Homsy GE, Knight TF. Toward in vivo digital circuits. In: Landweber LF, Winfree E, editors. Evolution as Computation: DIMACS Workshop. Berlin: Springer; 1999. pp. 275–295. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardner TS, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Construction of a genetic toggle switch in Escherichia coli. Nature. 2000;403:339–342. doi: 10.1038/35002131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dueber JE, Yeh BJ, Chak K, Lim WA. Reprogramming control of an allosteric signaling switch through modular recombination. Science. 2003;301:1904–1908. doi: 10.1126/science.1085945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobayashi H, Kaern M, Araki M, Chung K, Gardner TS, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Programmable cells: Interfacing natural and engineered gene networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:8414–8419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402940101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kramer BP, Fischer C, Fussenegger M. BioLogic gates enable logical transcription control in mammalian cells. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2004;87:478–484. doi: 10.1002/bit.20142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isaacs FJ, Dwyer DJ, Ding CM, Pervouchine DD, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Engineered riboregulators enable post-transcriptional control of gene expression. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:841–847. doi: 10.1038/nbt986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rinaudo K, Bleris L, Maddamsetti R, Subramanian S, Weiss R, Benenson Y. A universal RNAi-based logic evaluator that operates in mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:795–801. doi: 10.1038/nbt1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Win MN, Smolke CD. A modular and extensible RNA-based gene-regulatory platform for engineering cellular function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:14283–14288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703961104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson JC, Voigt CA, Arkin AP. Environmental signal integration by a modular AND gate. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2007;3:8. doi: 10.1038/msb4100173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Win MN, Smolke CD. Higher-order cellular information processing with synthetic RNA devices. Science. 2008;322:456–460. doi: 10.1126/science.1160311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ellis T, Wang X, Collins JJ. Diversity-based, model-guided construction of synthetic gene networks with predicted functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009;27:465–471. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan WH, Wang KM, Drake TJ. Molecular beacons. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2004;8:547–553. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Golding I, Cox EC. RNA dynamics in live Escherichia coli cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:11310–11315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404443101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yurke B, Turberfield AJ, Mills AP, Simmel FC, Neumann JL. A DNA-fuelled molecular machine made of DNA. Nature. 2000;406:605–608. doi: 10.1038/35020524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macdonald J, Li Y, Sutovic M, Lederman H, Pendri K, Lu WH, Andrews BL, Stefanovic D, Stojanovic MN. Medium scale integration of molecular logic gates in an automaton. Nano Letters. 2006;6:2598–2603. doi: 10.1021/nl0620684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yin P, Choi HMT, Calvert CR, Pierce NA. Programming biomolecular self-assembly pathways. Nature. 2008;451:318–322. doi: 10.1038/nature06451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cox MM, Lehman IR. RecA protein of Escherichia-coli promotes branch migration, a kinetically distinct phase of DNA strand exchange. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA-Biol. Sci. 1981;78:3433–3437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.6.3433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.An CI, Trinh VB, Yokobayashi Y. Artificial control of gene expression in mammalian cells by modulating RNA interference through aptamer-small molecule interaction. Rna-a Public. RNA Soc. 2006;12:710–716. doi: 10.1261/rna.2299306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tuleuova N, An C-I, Ramanculov E, Revzin A, Yokobayashi Y. Modulating endogenous gene expression of mammalian cells via RNA-small molecule interaction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;376:169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beisel CL, Bayer TS, Hoff KG, Smolke CD. Model-guided design of ligand-regulated RNAi for programmable control of gene expression. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2008;4:422. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar D, An CI, Yokobayashi Y. Conditional RNA Interference Mediated by Allosteric Ribozyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:13906–13907. doi: 10.1021/ja905596t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Masu H, Narita A, Tokunaga T, Ohashi M, Aoyama Y, Sando S. An activatable siRNA probe: trigger-RNA-dependent activation of RNAi function. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2009;48:9481–9483. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tuschl T, Zamore PD, Lehmann R, Bartel DP, Sharp PA. Targeted mRNA degradation by double-stranded RNA in vitro. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:3191–3197. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.24.3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reynolds A, Leake D, Boese Q, Scaringe S, Marshall WS, Khvorova A. Rational siRNA design for RNA interference. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:326–330. doi: 10.1038/nbt936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haley B, Tang G, Zamore P. In vitro analysis of RNA interference in Drosophila melanogaster. Methods. 2003;30:330–336. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elbashir SM, Martinez J, Patkaniowska A, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Functional anatomy of siRNAs for mediating efficient RNAi in Drosophila melanogaster embryo lysate. EMBO J. 2001;20:6877–6888. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.23.6877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stojanovic MN, Mitchell TE, Stefanovic D. Deoxyribozyme-based logic gates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:3555–3561. doi: 10.1021/ja016756v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mao CD, Sun WQ, Shen ZY, Seeman NC. A nanomechanical device based on the B-Z transition of DNA. Nature. 1999;397:144–146. doi: 10.1038/16437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Penchovsky R, Breaker RR. Computational design and experimental validation of oligonucleotide-sensing allosteric ribozymes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:1424–1433. doi: 10.1038/nbt1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davidson EA, Ellington AD. Engineering regulatory RNAs. Trends Biotechnol. 2005;23:109–112. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takai N, Hamanaka R, Yoshimatsu J, Miyakawa I. Polo-like kinases (Plks) and cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:287–291. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adams JM, Cory S. The Bcl-2 apoptotic switch in cancer development and therapy. Oncogene. 2007;26:1324–1337. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parrish S, Fleenor J, Xu SQ, Mello C, Fire A. Functional anatomy of a dsRNA trigger: Differential requirement for the two trigger strands in RNA interference. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:1077–1087. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tijsterman M, Ketting RF, Okihara KL, Sijen T, Plasterk RHA. RNA helicase MUT-14-dependent gene silencing triggered in C-elegans by short antisense RNAs. Science. 2002;295:694–697. doi: 10.1126/science.1067534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scherr M, Morgan MA, Eder M. Gene silencing mediated by small interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003;10:245–256. doi: 10.2174/0929867033368493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schwarz DS, Hutvagner G, Haley B, Zamore PD. Evidence that siRNAs function as guides, not primers, in the Drosophila and human RNAi pathways. Mol. Cell. 2002;10:537–548. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00651-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schwarz DS, Hutvagner G, Du T, Xu ZS, Aronin N, Zamore PD. Asymmetry in the assembly of the RNAi enzyme complex. Cell. 2003;115:199–208. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00759-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reynolds A, Leake D, Boese Q, Scaringe S, Marshall WS, Khvorova A. Rational siRNA design for RNA interference. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:326–330. doi: 10.1038/nbt936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bartlett DW, Davis ME. Insights into the kinetics of siRNA-mediated gene silencing from live-cell and live-animal bioluminescent imaging. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:322–333. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Czauderna F, Fechtner M, Dames S, Aygun H, Klippel A, Pronk GJ, Giese K, Kaufmann J. Structural variations and stabilising modifications of synthetic siRNAs in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2705–2716. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang DY, Winfree E. Control of DNA strand displacement kinetics using toehold exchange. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:17303–17314. doi: 10.1021/ja906987s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cullen BR. Induction of stable RNA interference in mammalian cells. Gene Ther. 2006;13:503–508. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.