SUMMARY

Microtubules are essential regulators of cell polarity, architecture and motility. The organization of the microtubule network is context-specific. In non-polarized cells, microtubules are anchored to the centrosome and form radial arrays. In most epithelial cells, microtubules are noncentrosomal, align along the apico-basal axis and the centrosome templates a cilium. It follows that cells undergoing mesenchyme-to-epithelium transitions must reorganize their microtubule network extensively, yet little is understood about how this process is orchestrated. In particular, the pathways regulating the apical positioning of the centrosome are unknown, a central question given the role of cilia in fluid propulsion, sensation and signaling. In zebrafish, neural progenitors undergo progressive epithelialization during neurulation, and thus provide a convenient in vivo cellular context in which to address this question. We demonstrate here that the microtubule cytoskeleton gradually transitions from a radial to linear organization during neurulation and that microtubules function in conjunction with the polarity protein Pard3 to mediate centrosome positioning. Pard3 depletion results in hydrocephalus, a defect often associated with abnormal cerebrospinal fluid flow that has been linked to cilia defects. These findings thus bring to focus cellular events occurring during neurulation and reveal novel molecular mechanisms implicated in centrosome positioning.

INTRODUCTION

Epithelial and mesenchymal cells exhibit distinct forms of cell polarity. Epithelial cells are polarized along the apico-basal axis, which is manifested by the localized distribution of junctional proteins, the apical position of the centrosome, the organization of the microtubule (MT) and actin cytoskeleton, the transport of cellular components and solutes across the epithelium and the presence of basal lamina at the basal surface. Mesenchymal cells are often migratory and have a front-to-back polarity (Hay 2005; Lee et al. 2006; Thiery and Sleeman 2006). The ability of cells to establish polarization is essential, not only for their function but also for proper morphogenesis of the tissues and organs of which they are a part. Polarization is typically studied in epithelial cells or mesenchymal cells but fewer studies have focused on how cells that are transitioning between the two states rearrange their polarity. In particular, the changes that occur during mesenchymal-to-epithelial transitions (MET) are poorly understood.

MTs are dynamic polar filaments with fast-growing plus-ends and slow-growing minus-ends that are key regulators of cell polarity. In migratory cells, the majority of MTs are anchored by their minus-ends at the centrosome or microtubule-organizing center (MTOC), resulting in a radial MT array with plus-ends facing towards the cell cortex. Radial MT tracks are thought to deliver activators of actin polymerization to the leading edge of the cell, thereby promoting polarized migration (Siegrist and Doe, 2007). By contrast, in epithelial cells, MTs are mostly noncentrosomal and align along the apico-basal axis. Polarity of MTs in these cells is manifested by the orientation of the minus ends towards the apical surface and the plus-ends facing the basal domain. This polarized organization facilitates directional vesicular transport to the apical and basolateral domains of the cell (Musch, 2004). Key to the acquisition of epithelial MT organization is the release of MTs from the centrosome (Keating et al., 1997). The latter is positioned at the apical surface in most epithelial cells and functions as a basal body, templating the growth of a ciliary axoneme (Satir and Christensen, 2007).

The mechanisms that mediate centrosome/basal body positioning in epithelial cells are poorly understood (Dawe et al., 2007) and yet essential, as cilia carry out functions in sensation, signaling and fluid flow across the surface of the epithelial sheet (Satir and Christensen, 2007). The role of the cytoskeleton in centrosome migration has been investigated in multi-ciliated cells using drugs that disrupt the cytoskeleton (Dawe et al., 2007). Disruption of MTs in these cells did not directly prevent centrosome migration, whereas disruption of the actin-myosin network did, highlighting a central role for the actin cytoskeleton in this process. The requirement for either the MT or actin network in cells with only one (primary) cilium on their surface is unknown (Dawe et al., 2007). Given the increasing evidence that proteins of the Par6-Par3-aPKC complex organize the MT network (Manneville and Etienne-Manneville, 2006), it is likely that these molecules are also implicated in centrosome positioning, however direct evidence for this is lacking.

Neurulation in the zebrafish provides a convenient in vivo setting in which to investigate how cell polarity is established, as neural progenitor cells are known to undergo progressive epithelialization. At the onset of neurulation, the zebrafish neural plate is composed of two cell layers. Deep cells are columnar and maintain contact with the basement membrane throughout neurulation (Hong and Brewster, 2006; Papan and Campos-Ortega, 1994). Superficial cells lie directly below the enveloping layer (Hong and Brewster, 2006). During neural convergence, an early stage in neurulation resulting in the formation of the neural rod, deep and superficial cells converge towards the dorsal midline while simultaneously intercalating amongst one another to create a single cell layered neuroepithelium. Both convergence and intercalation are active processes, mediated by the formation of polarized membrane protrusions (Hong and Brewster, 2006). Following neural convergence, cells establish a clearly defined apico-basal axis, marked by the presence of apical junctional complexes and primary cilia that extend into the luminal space (Geldmacher-Voss et al., 2003; Hong and Brewster, 2006; Kramer-Zucker et al., 2005). The establishment of apico-basal polarity in the zebrafish neural tube is thought to be intimately linked to a unique mode of cell division, known as a C-Division, during which one daughter cell remains on the ipsilateral side of the neural keel while the other crosses the midline (Kimmel et al., 1994; Papan and Campos-Ortega, 1994). Following these divisions, daughter cells acquire mirror-image polarity, which is essential for defining the midline of the neural tube (Clarke, 2009; Tawk et al., 2007). The importance of these divisions is highlighted by the severe morphological defects that arise when they occur in ectopic positions (Ciruna et al., 2006; Tawk et al., 2007). Pard3, also known as ASIP/Par3/Bazooka (Geldmacher-Voss et al., 2003), is an essential regulator of C-Divisions, as the orientation of the mitotic spindle is defective in Pard3-depleted embryos (Geldmacher-Voss et al., 2003) and midline crossing is not observed (Clarke, 2009; Tawk et al., 2007). While C-Divisions are clearly important for regulating cell polarity, other mechanisms that do not involve cell division are likely to be in place. Indeed, not all neural cells undergo C-Divisions (Concha and Adams, 1998) and blocking cell division does not prevent proper neural tube morphogenesis or epithelialization (Ciruna et al., 2006; Tawk et al., 2007).

In order to gain a better understanding of the mechanisms regulating cell polarity during neurulation, we investigate here the role of MTs and Pard3. We observe that MTs transition from a radial to a linear organization during neural convergence, consistent with a progressive epithelialization process, akin to MET. We further demonstrate overlapping functions for MTs and Pard3 in positioning the centrosome at the apical cortex, where it templates a primary cilium. Pard3 depletion results in hydrocephalus, a defect often associated with abnormal cerebrospinal fluid flow and cilia defects. Together, these findings bring to focus cellular events implicated in cell polarization during neurulation and reveal novel molecular mechanisms required for centrosome positioning. Since cell behaviors that drive neurulation in zebrafish are similar to those occurring during neural tube morphogenesis in Xenopus (Davidson and Keller, 1999) and secondary neurulation in amniotes (Harrington et al., 2009) the mechanisms revealed in this study are likely to be conserved.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Zebrafish strains

Studies were performed using wild-type (AB) strains and linguini (lin) mutants. The stages of neurulation (neural plate/tb-1 som, neural keel/4-5 som, neural rod/12-13 som and neural tube/24hpf and older) are as previously defined for the hindbrain region (Hong and Brewster, 2006).

Immunohistochemistry and imaging

Immunohistochemistry and imaging were carried out as previously described (Hong and Brewster, 2006) with the following modifications. Embryos were fixed overnight at 4°C in BT fixative (4% paraformaldehyde, 0.15 mM CaCl2, 4% sucrose in 0.1 M PO4 buffer) or at room temperature with either 4% paraformaldehyde or Prefer fixative (Anatech). Embryos that were treated using the BT fixative were washed with 0.1 M PO4 and H2O for 5 minutes each and treated with acetone at − 20°C for 7 minutes, followed by sequential washes with H2O and 0.1 M PO4. Fixed embryos were sectioned through the hindbrain region and processed for immunolabeling. Sections were imaged either with a Zeiss 510 META or a Leica SP5 confocal microscope.

The following antibodies were used: mouse-anti-ZO-1 (Zymed laboratories) at 1:200; mouse-anti-acetylated tubulin (Sigma) at 1:200; mouse-anti-β-tubulin (Sigma) at 1:200; rabbit-anti-β-tubulin (Abcam) at 1:200; mouse-anti-γ-tubulin (Sigma) at 1:200; rabbit-anti-Glu-tubulin (Millipore) at 1:500; mouse-anti-GM130 (Sigma) at 1:150; rabbit-anti-GFP (Invitrogen) at 1:1000. Secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa 488 or Cy3 (Molecular Probes) were used at a 1:200 dilution. DAPI (Molecular probes) was used according to manufacturer’s instructions.

pard3 MO-injected embryos displaying the hydrocephalus phenotype and uninjected controls were imaged live, using Nomarski optics, under a Nikon SMZ-1500 dissecting microscope and a Nikon Ri1 Color Camera.

Transmisson electron microscopy

Transmission electron imaging was performed as described by Brosamle and Halpern (Brosamle and Halpern, 2002).

DNA, RNA and Morpholino injections

Plasmids encoding mGFP (courtesy of R. Harland) and pard3-GFP (von Trotha et al., 2006) were prepared using a Qiagen Maxi Prep Kit. pard3-GFP was linearized and transcribed using mMESSAGE mMACHINE (Ambion). mGFP DNA was injected at the one cell stage and pard3-GFP RNA was injected mosaically at the 8-16 cell stage.

The pard3 MO1 (5′ TCAAAGGCTCCCGTGCTCTGGTGTC 3′) and ASIP MO (5′-ACACCGTCACTTTCATAGTTCCAAC- 3′) are targeted against the 5′UTR of the pard3 mRNA (Geldmacher-Voss et al., 2003; Wei et al., 2004). pard3 MO1 was injected at 2 mg/ml, 3 mg/ml, 4 mg/ml and 5 mg/ml concentrations. ASIP MO was injected at 20 mg/ml. mGFP DNA was injected at a 40 ng/μl concentration and pard3-eGFP RNA at 70 ng/μl for expression studies. Approximately 2 nl was injected into each embryo. For rescue experiments, a total of 130 pg or 260 pg of pard3-GFP RNA were injected.

Nocodazole treatment

Nocodazole (Sigma, cat # M1404) was prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions and diluted to 20 ug/ml in embryo medium. Because survival was poor following exposure to nocodazole, the treatments of (dechorionated) embryos were limited to 15–30 minutes at 28°C and the embryos fixed immediately after drug-exposure. Analysis of centrosome position: embryos that were injected with mGFP DNA at the one cell stage were exposed to nocodazole for 30 minutes beginning at the 9 som stage. Analysis of Pard3-GFP localization: embryos were injected mosaically with pard3-GFP mRNA at the 8-16 cell stage and exposed to nocodazole at 6 som.

Hydroxyurea/aphidicolin treatment

Tailbud stage embryos were dechorionated and incubated in 150 μM of aphidicolin (Sigma) and 20 mM hydroxyurea (Sigma) in 4% DMSO until the neural rod stage. Treated embryos were fixed, sectioned and processed for immunolabeling as described above. The procedure was effective as there was a ~ 75% reduction in the number of dividing cells in the hindbrain region of drug-treated embryos.

Measurements and statistical analysis

Measurements were done using the LSM software (Zeiss) and the student t-test was used to analyze measurements. Orientation of axonemes: the angle of the cell was measured as described in Hong and Brewster, 2006 and defined as “0°”. Axonemes that were plus or minus 45° degrees relative to this reference and pointing towards the midline were categorized as ‘apical’ while all other axonemes were labeled as ‘other’. Position of centrosomes relative to midline: a line was drawn through the midline of the neural rod and the distance between the line and each centrosome was measured. Normalized values were obtained by dividing the average distance of centrosomes from the midline in a designated region of the neural tube (boxed-in area of predefined size) by one half of the width of the neural tube. These measurements (centrosome position and NT width) were performed where the neural tube is widest, unless otherwise indicated. The student t-test was used to analyze measurements. Length of cilia: Z-stacks were taken of the hindbrain sections (as ventral and dorsal cilia spanned multiple focal planes) and measurements were done on projections of the z-stacks.

RESULTS

MT organization shifts from radial to comet-shaped during neurulation

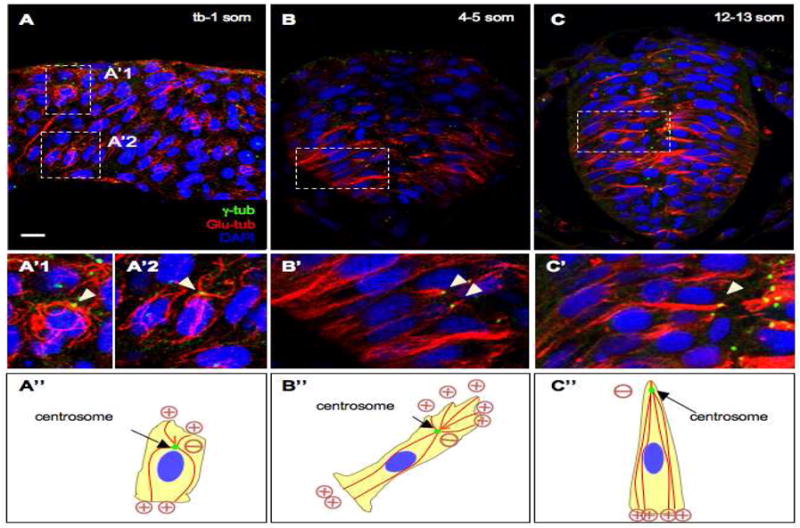

Zebrafish neuroepithelial cells exhibit both mesenchymal and epithelial features during neural convergence but acquire progressively more epithelial characteristics as neurulation proceeds (Geldmacher-Voss et al., 2003; Hong and Brewster, 2006). Given their early hybrid cytoarchitecture, it was unclear how the MT network would be organized and whether the centrosome functions as a MTOC in these cells. To address these questions, we immunolabeled embryos at the neural plate (tb-1 som) and neural keel (4-5 som) stages with anti-γ-tubulin (γ-tub), a centrosome marker (Oakley, 1992), and anti-Glu-tubulin (Glu-tub) a detyrosinated form of α-tubulin in which the carboxy-terminal glutamic acid is exposed (Westermann and Weber, 2003). Glu-tubulin is typically considered a marker for stable (older) MTs that are associated with the centrosome (Wen et al., 2004; Westermann and Weber, 2003). We observed that at the tb-1 som stage, MTs in both deep and superficial cells have a radial organization, extending from the perimeter of the centrosome (Fig. 1A–A″). By the 4-5 som stage many deep and superficial cells have already undergone intercalation and it is no longer possible to identify these cell types unambiguously. At this stage, MTs extend from the basal side of the centrosome, although some short MTs are also observed protruding towards the apical surface (Fig. 1B–B″).

Fig. 1. Microtubule organization during neurulation.

(A–C) Sections of embryos at the neural plate (A, A′), neural keel (B, B′) and neural rod (C, C′) stages immunolabeled with antiγ-tub and anti-Glu-tub. (A′–C′) Higher magnification of boxed areas in (A–C). Panels A, A′1, A′2 are a compilation of Z stacks. (A″;–C″) Representations of MT organization. Plus and minus signs indicate the orientation of microtubules (inferred from the position of the centrosome). The red lines are microtubules, the green dots are centrosomes. Arrowheads: centrosomes. Scale bars: 10 μm (A–C), 5 μm (A′–C′).

Recent evidence suggests that the trans-Golgi network can also nucleate MTs in migrating cells. Unlike the radial, centrosome-nucleated MT arrays, the Golgi-originated MTs were shown to be asymmetric, pointing toward the leading edge of the polarized/migrating cell (Efimov et al., 2007). We therefore asked whether a subset of cytoplasmic MTs are also anchored at the Golgi, by immunolabeling embryos at the neural keel stage with the cis-Golgi marker GM130 (Nakamura et al., 1995) and anti-β-tubulin (β-tub), a general marker for MTs. We observed that the Golgi network appeared to align parallel rather than perpendicular to MT tracks and is thus unlikely to function as a MTOC in neuroepithelial cells (data not shown). These observations suggest that the centrosome functions as a MTOC and that the organization of MTs is mesenchymal in neuroepithelial cells at the tb-1 som stage.

Towards the end of neural convergence, cells establish apico-basal polarity (Geldmacher-Voss et al., 2003; Hong and Brewster, 2006). We therefore inquired what changes in MT organization accompany this transition. Analysis of embryos at the neural rod stage (12-13 som), revealed that the centrosome shifted to an apical position (characteristic of epithelial cells) and that MTs facing the apical surface were no longer observed, while those extending towards the basal surface remained attached to the centrosome and appeared longer, giving the complex a comet-like appearance (Fig. 1C–C″).

Together these findings reveal that the organization of the MT network undergoes a dramatic rearrangement, shifting from a mesenchymal to an epithelial-like organization between the neural plate and the neural rod stages. These observations further support the model that zebrafish neuroepithelial cells undergo progressive epithelialization during neurulation.

The centrosome migrates apically during neural convergence

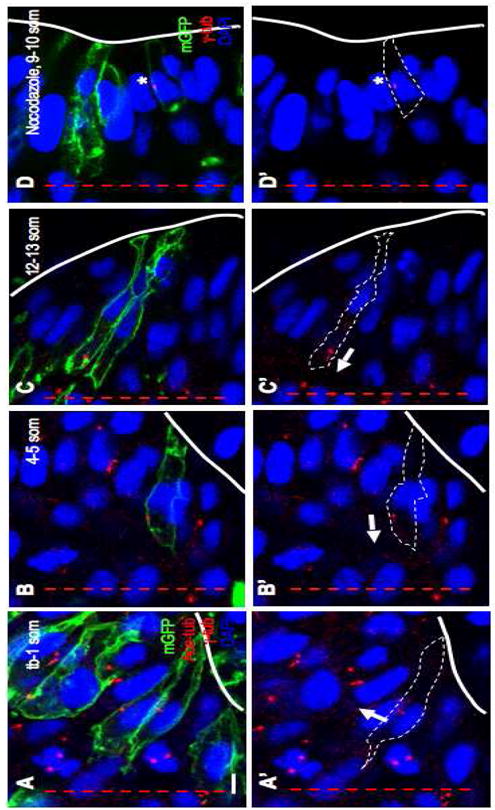

The transition in MT organization from radial to comet-shaped appears to coincide with the migration of the centrosome towards the apical surface. In order to assess the extent of migration more directly, we visualized the position of the centrosome relative to the cell cortex and the nucleus by double labeling cells with mGFP and anti-γ-tub. The position of the centrosome was scored in individual mGFP-labeled deep cells as either lateral (position 1) or apical to the nucleus at the neural plate, neural keel and neural rod stages (Fig. 2). The latter group was further subdivided into: immediately apical to the nucleus (position 2) or a distance away from the nucleus (position 3). We observe that, at early stages (tb-5 som), the majority of centrosomes are in position 1 or 2 (Fig. 2A–B′; Table S1). As neurulation proceeds (12-13 som), most centrosomes now occupy position 3 (Fig. 2C,C′; Table S1).

Fig. 2. Centrosome position during neural convergence is microtubule-dependent.

Sections of WT (A–C) and nocodazole-treated (D) embryos at the neural plate (A, A′), neural keel (B, B′) and neural rod (C, C′, D, D′) stages immunolabeled with anti-Ace-tub, anti-γ-tub and anti-GFP (A–C) or anti-γ-tub and anti-GFP (D). (A′, B′, C′, D′) Same panels as in (A, B, C, D) without the mGFP label. Red lines: midline; white lines: outline of the cells; arrows: orientation of axonemes; asterisk: ectopic centrosome. Scale bar: 5 μm.

This shift in position indicates that the centrosome undergoes migration from the cell center towards the apical cortex, but docking of the centrosome is not completed by the end of neural convergence. The apical movement of the centrosome correlates temporally with the reorganization of the MT network from radial to comet-like, suggesting that these events are linked.

Centrosomes anchor both cytoplasmic MTs and axonemes during neural convergence

The comet-shaped organization of MTs at the neural rod stage contrasts with that reported for most epithelial cells, in which centrosomes function as basal bodies and release cytoplasmic MTs (Musch, 2004). One possible explanation for the persistent association of the centrosome with MTs in neuroepithelial cells is that cilia/axoneme assembly may be delayed in neuroepithelial cells. To address the timing of axoneme assembly, we labeled neural rod stage embryos with antibodies directed against acetylated tubulin (Ace-tub, a marker for axonemal and axonal MTs) and Glu-tub. Interestingly, we observed that a short axoneme-like structure, that was both Ace-tub and Glu-tub-positive, was present at this stage and closely associated with cytoplasmic MTs that were labeled with Glu-tub exclusively (Fig. S1A–A″). This structure is likely to be an axoneme because it anchors at the centrosome, as revealed by double immunolabeling with anti-Glu-tub and anti-γ-tub (Fig. S1B–B″).

We next asked how early the axoneme is formed in neuroepithelial cells, since transmission electron microscopy reports revealed that, depending on the cell type, it is either preassembled while the mother centriole occupies a central position within the cell or assembled at the cell cortex once the centrosome has assumed its role as a basal body (Pedersen et al., 2008; Sorokin, 1962). The former mechanism applies for neuroepithelial cells, as a short anti-Ace-tub labeled axoneme is associated with the centriole as early as the neural plate stage (Fig. 2A, A′) and continuing into the neural keel and rod stages (Fig. 2B–C′). Thus, during neural convergence, the centrosome appears to have the dual function of anchoring cytoplasmic MTs and the axoneme. Moreover, the axoneme is assembled prior to docking of the centrosome/basal body at the apical cell cortex.

The centrosome/MT/cilium complex is maintained in the neural tube

Upon completion of neural convergence, cavitation transforms the zebrafish neural rod into a neural tube with a ciliated central lumen (Kramer-Zucker et al., 2005). We next investigated whether the complex between the centrosome, cytoplasmic and axonemal MTs is maintained in neural progenitors lining the luminal space or whether these cells eventually acquire a MT organization that is more typical of epithelial cells (Musch, 2004). Analysis of neural tube stage, 24 hpf and 48 hpf embryos, immunolabeled with a combination of anti-Glu-tub/anti-Ace-tub or anti-Glu-tub/anti-Ace-tub/anti-γ-tub, revealed that in lateral (Fig. S2A,B–B″), ventral (Fig. S2A,C–C″,F–F″) and dorsal (Fig. S2D,E–E″) regions of the neural tube, both the cytoplasmic MTs and axoneme appear to remain anchored at the centrosome/basal body, now relocated at the apical cortex. However, in contrast to the short axonemes present during neural convergence and in lateral regions of the neural tube, the axonemes in ventral and dorsal regions of the neural tube were almost six-fold longer (Table S2, 5.9-fold for ventral cilia and 5.6-fold for dorsal cilia).

Together, the above findings provide the first detailed analysis of MT dynamics that occur during neurulation in the zebrafish. We demonstrate that neural convergence is accompanied by a reorganization of cytoplasmic MTs and by the apical migration of the centrosome. Moreover, the centrosome, which functions as a MTOC in these cells, exhibits several interesting properties, in that it does not orient toward the direction of protrusive activity during neural convergence and does not release cytoplasmic MTs once it becomes a basal body. The centrosome also appears to template for an intracytoplasmic axoneme.

MTs are required for centrosome positioning but not Pard3 localization

Microtubules are prime candidates for positioning the centrosome at the apical cortex, as they are tethered to this organelle on one end and contact the cell cortex with their other end. To determine whether MTs are implicated in centrosome positioning, we exposed mGFP DNA-injected embryos to nocodazole at the neural rod stage (9 som) and labeled them following treatment with anti-γ-tub (Fig. 2D,D′). To score the effect of the drug treatment on centrosome localization, we measured the average distance between the centrosomes and the midline of the neural rod. We observed that centrosomes in drug-treated embryos were positioned significantly further away from the midline than in controls (Table S3.1). While this suggests that centrosomes are localized basally, we were concerned that not all cells span the full width of the neuroepithelium in drug-treated embryos. We therefore also scored the percentage of mGFP labeled cells in which the centrosome is ectopically positioned in the immediate vicinity to the nucleus (Position 1, Fig. 2D,D′) and found this number to be higher for drug-treated cells (dorsal region: 64% for nocodazole-treated versus 13% for controls; Table S3.2), particularly in dorsal regions. These findings suggest that MT destabilization alters centrosome positioning. To further test the requirement of MTs in centrosome migration, we analyzed centrosomes in linguini (lin) mutants in which MTs are disorganized and similar in appearance to those in nocodazole-treated embryos (insets in Fig. S3B and unpublished observation). Labeling of embryos at the 4-5 som stage with mGFP and anti-γ-tub revealed that 66% of centrosomes were immediately adjacent to the nucleus (Position 1) in lin mutants (n= 32 centrosomes, 2 embryos) in comparison to 17 % in controls (n= 60 centrosomes, 5 embryos). These finding further support a role for MTs in centrosome positioning.

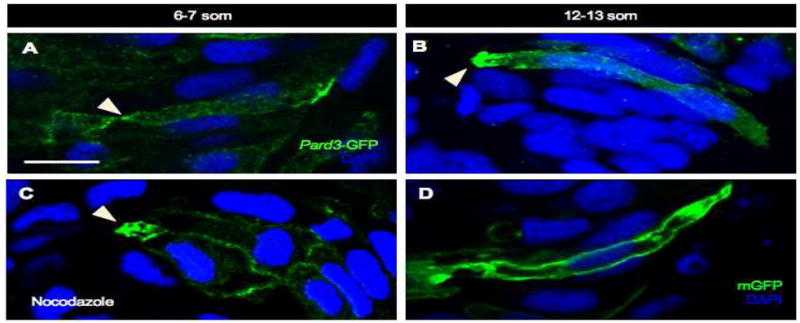

Par3/Bazooka is one of the earliest markers for apico-basal polarity in epithelial cells and its localization at the apical surface is thought to depend on multiple factors, including MTs (Harris and Peifer, 2005; Martin-Belmonte and Mostov, 2008). To address whether MTs control several aspects of apico-basal polarity in the neural rod, we investigated whether MTs are required for proper localization of Pard3, using a construct encoding a GFP-tagged version of Pard3 (von Trotha et al., 2006). The first time point when we observe apical Pard3-GFP in control embryos is at 6-7 som (Fig. 3A). Pard3-GFP also localizes to the basal surface in 41% of mGFP labeled cells (n= 22 cells, 3 embryos), however, this is most likely due to overexpression as basal Pard3 has not been previously reported. By 12-13 som, Pard3-GFP expression is enhanced at the apical pole, as previously reported (Geldmacher-Voss et al., 2003; Tawk et al., 2007). Interestingly, we observed that nocodazole treatment did not disrupt apical Pard3-GFP localization at 6-7 som (Fig. 3C; 45% of mGFP-labeled cells with apical localization for nocodazole-treated, n= 47 cells, 4 embryos versus 54% for controls, n= 22 cells, 3 embryos). The ubiquitous expression of mGFP (Fig. 3D) compared to the polarized expression of Pard3-GFP (Fig. 3C) suggests that the injection procedure itself did not introduce an artifact. Thus, Pard3 is the earliest known marker to localize to the apical cortex in the zebrafish neural tube, as other markers become localized only at the late neural rod stage (Geldmacher-Voss et al., 2003; Hong and Brewster, 2006), and its initial localization appears independent of MTs. Together these observations indicate that MTs control centrosome positioning but are not required for all aspects of neuroepithelial cell polarity during neurulation.

Fig. 3. Localization of Pard3-GFP may be microtubule-independent.

Sections of control (A, B, D) and nocodazole-treated (C) embryos at 6-7 som (A, C) and 12-13 som (B, D). (A–C) Embryos were mosaically injected at the 8-16 cell stage with pard3-GFP mRNA and immunolabeled with anti-GFP. (C) The nocodazole treatment was performed for 30 minutes at an early 6 som stage and the embryo was fixed immediately following treatment. (D) Embryo was injected with mGFP DNA and immunolabeled with anti-GFP. Arrowheads: apical localization of Pard3-GFP. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Pard3 depletion disrupts centrosome positioning

Given that Pard3 is an early marker for apico-basal polarity, we asked whether it may function as a cortex-derived signal to regulate centrosome positioning. We reasoned that if Pard3 is required for centrosome migration towards the apical cortex, then loss of Pard3 function should result in the mispositioning of centrosomes.

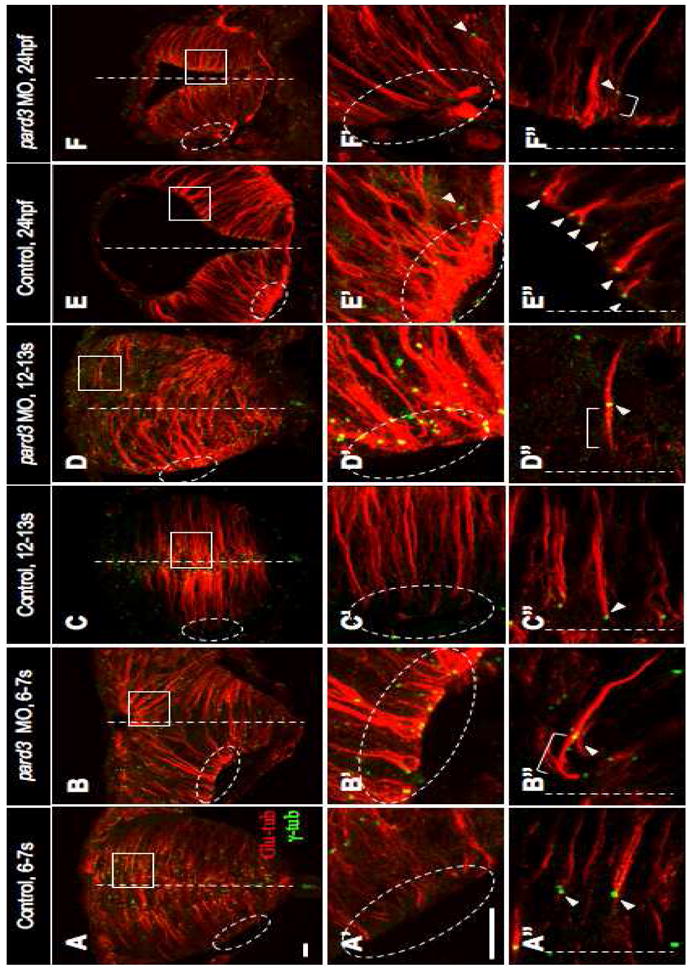

To test this, we depleted Pard3 function using morpholinos (MO1) (Wei et al., 2004) and immunolabeled embryos at 12-13 som with anti-γ-tub and anti-Glu-tub. pard3 MO1 was injected at four different concentrations (2 mg/ml, 3 mg/ml, 4 mg/ml and 5 mg/ml). Loss of Pard3 function caused a slight delay in neurulation, however the neural tube did eventually form properly. We next measured the distance between centrosomes and the midline at the neural rod stage, in embryos that had been injected with these different concentrations of pard3 MO. Consistent with our hypothesis on the role of pard3, we observed a dosage-dependent effect, with the highest MO1 concentrations causing the most severe displacement of the centrosome away from the midline (Table S4). Notably, embryos injected at the 5 mg/ml concentration could be clustered into two groups: those in which the majority of centrosomes were positioned in close vicinity but not immediately adjacent to the basement membrane (Fig. 4D,D′, 25.9 μm relative to 5.9 μm for controls) and another group in which centrosomes were observed closer to the midline (15.9 μm).

Fig. 4. Pard3 is required for apical localization of the centrosome.

Sections of control (A–A″, C–C″, E–E″) and pard3 MO-injected (B–B″, D–D″, F–F″) embryos at the early rod (6-7 som, A–B″), late rod (12-13 som, C–D″) and neural tube (24 hpf, E–F″) stages immunolabeled with anti-Glu and anti-γ-tub. Ovals and rectangles in (A–F): areas magnified in panels A′–F′ and A″–F″ respectively; white lines: midline; bracketed lines: MTs extending towards the apical cortex; arrowheads: centrosomes. Scale bars: 10 μm.

To investigate centrosome migration in Pard3-depleted embryos, we carried out a developmental series on embryos injected at the 5 mg/ml concentration. At the tailbud stage, labeling with mGFP and anti-γ-tub revealed that the majority of centrosomes in Pard3-depleted embryos are positioned close to next to the nucleus (71% of centrosomes, n= 7 cells, 3 embryos; data not shown), as observed in control embryos (Fig. 2A, A′; Table S1). However, we observed a striking mispositioning of centrosomes in embryos immunolabeled with anti-γ-tub and anti-Glu-tub at the 6-7 som stage, coincident with the onset of Pard3-GFP localization in neuroepithelial cells. While centrosomes were absent from basal regions in control embryos (Fig. 4A′), a subset (Table S5, 11%) aligned along the basal cortex in pard3 MO1-injected embryos (Fig. 4B′). In apical regions, centrosomes of control embryos were positioned at the tip of the MT arrays, resulting in a comet-like shape (Figs 4A″, 1C′). By contrast, in pard3 MO1-injected embryos, MTs extended in a “bipolar” fashion from the centrosome (bracketed line in Fig. 4B″). At the neural rod stage (12-13 som), basally-positioned centrosomes were observed in pard3 MO1-injected embryos, as described above, however they no longer aligned with the basal cell cortex, suggesting that they had begun to migrate (Fig. 4D′). Apically-positioned centrosomes in these embryos continued to anchor bipolar MTs (Fig. 4D″; Table S6, 71% for pard3 MO1-injected versus 2% for control embryos). Following neural tube formation (24 hpf), a few basally positioned centrosomes were now observed in control embryos (Fig. 4E′), which most likely are associated with newly formed neurons (Zolessi et al., 2006). There was no obvious difference in the number of basally positioned centrosomes in Pard3-depleted embryos compared to controls (Fig. 4F′). However, in contrast to the subapical anchoring of the majority of centrosomes in control embryos, which now function as basal bodies, many centrosomes in pard3 MO1-injected embryos were not adjacent to the apical surface and continued to anchor bipolar MTs (Fig. 4F″; Table S6, 46% in pard3 MO1-injected versus 5% in control embryos).

The effects of pard3 MO1 on centrosome positioning were independently confirmed (Table S7) using another translation blocking MO against Pard3/ASIP (Geldmacher-Voss et al., 2003). Furthermore, centrosome positioning defects were rescued (Table S7) in pard3 MO1-depleted embryos by co-injecting RNA encoding Pard3-GFP that lacks the binding site for MO1 (von Trotha et al., 2006).

The centrosome positioning defects observed in Pard3-depleted embryos are not caused by a disruption in cell morphology or apico-basal polarity. Indeed, cellular morphology in these embryos appears normal as revealed by the presence of linear Glu-tub-positive MT arrays at all developmental stages analyzed (Fig. 4B,D,F). In addition, embryos co-injected with the pard3 MO1 and mGFP have characteristic elongated cell shapes at the neural rod stage (12-13 som; Fig. S4B,D). Apico-basal polarity also did not appear significantly disrupted in Pard3-depleted embryos, since ZO-1, a marker for tight junctions, localized properly at the apical midline (Fig. S4B,B′) despite the displacement of centrosomes in the same embryos, at the neural rod stage (12-13 som; Fig. S4D,D′).

We therefore propose that the apical localization of Pard3-GFP is consistent with a requirement for Pard3 in mediating but not initiating the migration of the centrosome, as the latter occupies a subapical position by the 6-7 som stage (Fig. 2B–C′). In addition, loss of pard3 function appears to delay the docking of the centrosome/basal body at the apical cell cortex. These defects correlate with the abnormal organization of MTs, which fail to transition into the characteristic comet shape observed in control embryos, suggesting that centrosome migration is intimately coupled with rearrangement of the MT cytoskeleton. The ectopic position of centrosomes in nocodazole-treated embryos provides further evidence for the role of MTs in mediating this process.

The findings outlined above are consistent with a role for Pard3 in regulating centrosome migration. However, several reports have also documented an abnormal basal positioning of dividing neuroepithelial cells in embryos treated with pard3 MO1 (Geldmacher-Voss et al., 2003; Zolessi et al., 2006), raising the possibility that centrosome mislocalization is in fact caused by ectopic cell divisions. To address this concern, we blocked cell division using the mitotic inhibitors hydroxyurea and aphidicolin at the neural plate stage, and analyzed centrosome position in Pard3-depleted (5 mg/ml MO) and control embryos. We found that while blockage of cell division partially rescues pard3-MO1 injected embryos, centrosomes in these embryos are further apart than in uninjected, drug-treated controls (Table S4), indicating that ectopic cell division cannot be the sole explanation for abnormal centrosome positioning. These results suggest that Pard3 is required for centrosome migration in interphase cells.

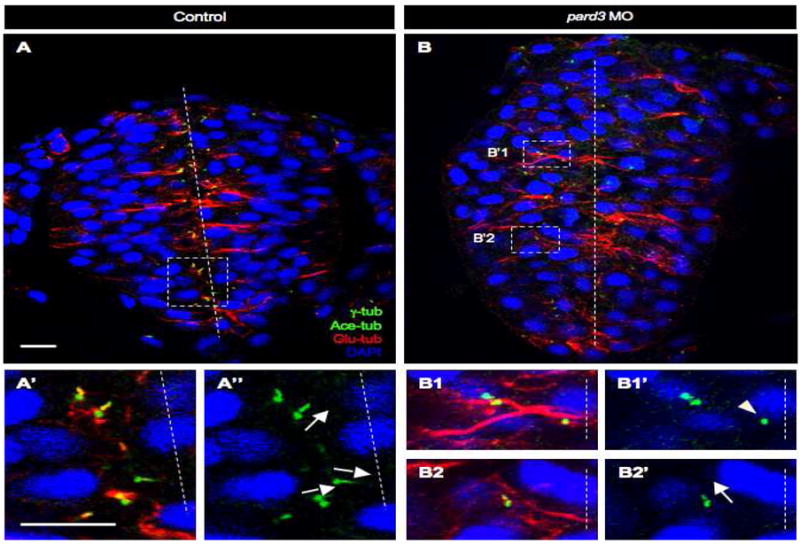

Cilia defects associated with loss of Pard3 function

While members of the Par3-Par6-aPKC complex have not been implicated in centrosome migration in other organisms, recent evidence suggests that Par3 is required for the growth and elongation of the primary cilium (Sfakianos et al., 2007). We therefore tested whether pard3 MO1-injected embryos exhibit other defects associated with cilia. We first scored axonemes for growth defects at the neural rod stage and observed that in pard3 MO-injected embryos, a significant fraction of centrioles are either not associated with an axoneme or their axoneme is too short to be detected (Fig. 5B1–B1′, Table S8, 25% for controls versus 55% for pard3 MO). At the neural tube stage in control embryos, internal axonemes remain short (Fig. 2A–C) until the centrosome docks at the apical cortex and becomes a basal body. A dramatic growth phase of ventral (Fig. S2A, C–C″, Table S2) and dorsal (Fig. S2D–E″, Table S2) cilia follows, which is mediated by intraflagellar transport (Pedersen et al., 2008). In contrast, cilia lining the lateral walls of the neural tube remain short (Fig. S2A–B″, Table S2). In the pard3 MO1-injected embryos, the length of cilia in both lateral and ventral cells is comparable to that of controls at the neural tube stage (Table S2, lateral: 1.12 μm versus 1 μm in controls and ventral: 5.17 μm versus 5.91 μm in controls), indicating that axoneme growth is delayed rather than blocked in these embryos.

Fig. 5. pard3 depletion causes misorientation and delayed cilia growth.

Sections of control (A–A″)and pard3 MO-injected (B–B2′) embryos at 12-13 som, immunolabeled with anti-Glu-tub, anti-γ-tub and anti-Ace-tub. Nuclei are labeled with DAPI. (A′, A″, B1–B2′) Higher magnifications of boxed areas in (A) and (B) respectively. Dashed lines: midline; arrows: orientation of cilia; arrowhead: centrosome not associated with an axoneme. Scale bars: 10 μm.

We also investigated whether loss of pard3 function causes axoneme orientation defects. In control embryos, axoneme orientation appears to be random until the centrosomes approach the apical surface at the neural rod stage (Fig. 2A′–C′, Table S9). By this stage, the majority of axonemes orient perpendicular to the cell surface (Figs. 2C′, 5A–A″, Table S9). In pard3 MO1-injected embryos, axoneme orientation remains random at the neural rod stage (Fig. 5B2–B2′; Table S9) and continuing into the neural tube stage (Table S10). These findings suggest that pard3 may also be implicated in the proper orientation of the axoneme prior to and following the docking of the centrosome at the apical cortex.

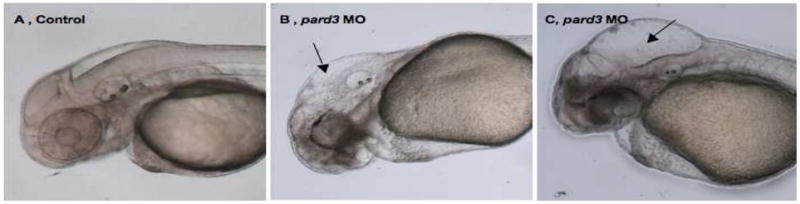

Pard3-depletion causes hydrocephalus

Impaired motility of cilia in the mouse neural tube results in hydrocephalus, an enlarged brain caused by abnormal cerebrospinal fluid flow (Bisgrove and Yost, 2006). The cilia lining the zebrafish neural tube are motile (Kramer-Zucker et al., 2005) and consistent with this observation, we demonstrate here using transmission electron microscopy that they have a 9 + 2 axoneme (containing nine peripheral doublet microtubules and two central microtubules; Fig. S5), a configuration thought to be required for force generation. As in the mouse embryo, impaired cilia motility in zebrafish causes hydrocephalus (Kramer-Zucker et al., 2005).

Since a subset of cilia in Pard3-depleted embryos have delayed growth or exhibit abnormal orientation, we asked whether these defects may also trigger hydrocephalus. To address this, we injected pard3 MO1 at concentrations ranging from 1 mg/ml to 5 mg/ml. Embryos injected with the lowest and highest concentrations of MO1 did not have enlarged brains, in fact brain size was even reduced in the latter, most likely due to high levels of cell death (data not shown). However, up to 25% of embryos injected with intermediate concentrations (2.5 mg/ml) of MO1 exhibited hydrocephalus (Table S11), with phenotypes ranging from mild (Fig. 6B) to severe (Fig. 6C). These morphological defects were rescued by co-injecting pard3-GFP mRNA, as the percentage of embryos exhibiting enlarged ventricles was reduced from 25 % for Pard3 MO-depleted (2 mgs/ml, n= 42 out of 168 embryos) to 14 % and 4 % for embryos co-injected with 130 pg (n= 9 out of 63 embryos) and 260 pg (n= 6 out of 168 embryos) of pard3-GFP mRNA, respectively. Together these findings indicate that MO1-depletion of Pard3 causes hydrocephalus, in a concentration-dependent manner. While this phenotype can be triggered by a variety of cellular abnormalities, the presence of abnormal cilia in pard3 MO1-injected embryos is likely to be an underlying cause.

Fig. 6. Pard3 depletion causes hydrocephalus.

(A–C) Lateral views of 48 hpf control (A) and pard3 MO-injected embryos, with a mild (B) and severe (C) hydrocephalus, imaged using Nomarski optics. Black arrows: enlarged hindbrain ventricles. Scale bar: 24nm.

DISCUSSION

MTs play a central role in cell polarity, architecture and motility. While MT organization has been studied extensively in epithelial and mesenchymal cells, little is known about how the MT network reorganizes in cells converting between the epithelial and mesenchymal states. Such switches are not only encountered during normal development, (for example gastrulation, nephrogenesis and neural crest emigration) but also during cancer progression (Yang and Weinberg, 2008). Neurulation in the zebrafish provides a convenient in vivo context in which to investigate the events and molecular mechanisms orchestrating the transformation of these cytoskeletal elements, as neural progenitor cells undergo progressive epithelialization.

Changes in MT organization during neurulation coincide with behavioral transitions

Our studies have unveiled three distinct stages in MT organization that appear to closely parallel cellular events that drive neurulation in the zebrafish. Stage 1 MTs (neural plate and neural keel) have a radial organization, with their minus ends anchored at the centrally positioned centrosome. This type of MT organization is typically observed in migrating mesenchymal cells, where the plus ends of radial MTs are thought to deliver activators of the actin cytoskeleton to the leading edge (Siegrist and Doe, 2007). We have previously shown that neuroepithelial cells extend polarized protrusions during neural convergence (Hong and Brewster, 2006) and have recently obtained evidence that this protrusive activity is dependent on MTs (manuscript in preparation). Stage 2 MTs (neural rod) take on a comet-like appearance, as neural convergence is completed. This change in organization is brought about by the migration of the centrosome towards the apical cortex and the apparent selective shortening of MTs whose plus ends face the midline of the neural rod. The shift in MT organization coincides with a gradual decrease in membrane protrusive activity and the early phase of apico-basal polarity establishment. It is tempting to speculate that the elimination of MTs with plus ends directed medially may contribute to the cessation of protrusive activity, as proteins that normally associate with the plus end of MTs and stimulate actin polymerization would no longer be delivered to the cell cortex. In stage 3 (neural tube), the centrosome docks at the apical cortex and becomes a basal body, while continuing to anchor MTs that run parallel to the long axis of the cell. MTs at this stage may further contribute to the establishment of apico-basal polarity by facilitating the polarized delivery of junctional complex proteins (Musch, 2004). Thus, MT dynamics during neurulation may not occur simply as a consequence of changes in cellular behaviors but actually drive some of these changes.

Role of Pard3 in orchestrating cell polarity in the neural tube

Pard3 has previously been shown to orchestrate midline crossing during C-Divisions in zebrafish (Clarke, 2009; Tawk et al., 2007). These divisions generate daughter cells with mirror-image apico-basal polarity and are thought to play an essential role in neural tube morphogenesis, as they orchestrate the formation of ectopic apical and basal specialization and neural tubes when they occur ectopically (Clarke, 2009; Tawk et al., 2007). While these observations suggest that apico-basal polarity is primarily established during C-Divisions, we speculate that there is an additional, cell division-independent mechanism in place, as cells that divide at the neural plate and early neural keel stages do not appear to cross the midline (Concha and Adams, 1998), and hence do not inherit mirror symmetric apico-basal structures. Furthermore, blockage of cell division does not impair neural tube morphogenesis (Ciruna et al., 2006; Tawk et al., 2007) or centrosome positioning (this study). Thus, we hypothesize that Pard3 is also required for the establishment of apico-basal polarity in interphase cells.

Loss of Pard3 function during early development in the zebrafish does not significantly affect cell morphology, possibly because Pard3 function is only partially lost. Regardless of the reason underlying this relatively mild phenotype, the lack of adhesion and polarity defects has enabled us to address the role of this protein in centrosome positioning. Our studies suggest that Pard3, under normal conditions, is required to relocate the centrosome from its initial position near the nucleus to the apical pole. When Pard3 function is lost, centrosome migration is impaired as early as the 6-7 som stage and this effect is further exacerbated by ectopic cell divisions displacing centrosomes basally. Since Pard3 only localizes apically at the 6-7 som stage and centrosomes begin migrating prior to this time point, Pard3 is unlikely to initiate this process. Furthermore, the observation that centrosomes are ectopically located in nocodazole-treated embryos but Pard3 localization appears unaffected, suggest that Pard3 may function upstream of MTs to recruit the centrosome to the apical cortex. In support of this hypothesis, MT organization is disrupted in Pard3-depleted embryos. Therefore, a possible model, similar to one proposed for mitotic spindle orientation (Wu et al., 2006), is that Pard3 functions at the apical cortex, along with the MT motor protein Dynein, to reel in MTs whose plus ends face this domain. Since MTs are tethered to centrosomes by their minus ends, they could exert a tugging force on this organelle. It would be interesting in the future to test whether other members of the Par6-Par3-aPKC complex are implicated in centrosome positioning. There is so far no evidence for this, as loss of Pard6γb appears to be implicated in apical membrane biogenesis in the zebrafish neural tube (Munson et al., 2008). The function of aPKC has not yet been tested.

In summary, our functional analysis of Pard3 has revealed a novel role for this protein in centrosome positioning that may be mediated by microtubules. In addition, we observe that Pard3 is required for proper cilia orientation and confirm its role in timely cilia elongation (Sfakianos et al., 2007).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mike Sepanski for his assistance with electron microscopy and A. Reugels for the pard3-GFP construct. In addition, we thank D. Blumberg, M. Halpern, M. Starz-Gaiano and M. Van Doren for comments and suggestions on the manuscript. This research was supported by an National Science Foundation Grant # 0448432 and an NIH/NIGMS Grant # 1R01GM085290-01A1 to R. Brewster. The Leica SP5 confocal microscope was purchased with funds from the National Science Foundation, Grant # DBI-0722569.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bisgrove BW, Yost HJ. The roles of cilia in developmental disorders and disease. Development. 2006;133:4131–4143. doi: 10.1242/dev.02595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosamle C, Halpern ME. Characterization of myelination in the developing zebrafish. Glia. 2002;39:47–57. doi: 10.1002/glia.10088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciruna B, Jenny A, Lee D, Mlodzik M, Schier AF. Planar cell polarity signalling couples cell division and morphogenesis during neurulation. Nature. 2006;439:220–224. doi: 10.1038/nature04375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke J. Role of polarized cell divisions in zebrafish neural tube formation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concha ML, Adams RJ. Oriented cell divisions and cellular morphogenesis in the zebrafish gastrula and neurula: a time-lapse analysis. Development. 1998;125:983–994. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.6.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson LA, Keller RE. Neural tube closure in Xenopus laevis involves medial migration, directed protrusive activity, cell intercalation and convergent extension. Development. 1999;126:4547–4556. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawe HR, Farr H, Gull K. Centriole/basal body morphogenesis and migration during ciliogenesis in animal cells. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:7–15. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efimov A, Kharitonov A, Efimova N, Loncarek J, Miller PM, Andreyeva N, Gleeson P, Galjart N, Maia AR, McLeod IX, Yates JR, 3rd, Maiato H, Khodjakov A, Akhmanova A, Kaverina I. Asymmetric CLASP-dependent nucleation of noncentrosomal microtubules at the trans-Golgi network. Dev Cell. 2007;12:917–930. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geldmacher-Voss B, Reugels AM, Pauls S, Campos-Ortega JA. A 90-degree rotation of the mitotic spindle changes the orientation of mitoses of zebrafish neuroepithelial cells. Development. 2003;130:3767–3780. doi: 10.1242/dev.00603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington MJ, Hong E, Brewster R. Comparative analysis of neurulation: first impressions do not count. Mol Reprod Dev. 2009;76:954–965. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris TJ, Peifer M. The positioning and segregation of apical cues during epithelial polarity establishment in Drosophila. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:813–823. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong E, Brewster R. N-cadherin is required for the polarized cell behaviors that drive neurulation in the zebrafish. Development. 2006;133:3895–3905. doi: 10.1242/dev.02560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating TJ, Peloquin JG, Rodionov VI, Momcilovic D, Borisy GG. Microtubule release from the centrosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:5078–5083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel CB, Warga RM, Kane DA. Cell cycles and clonal strings during formation of the zebrafish central nervous system. Development. 1994;120:265–276. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer-Zucker AG, Olale F, Haycraft CJ, Yoder BK, Schier AF, Drummond IA. Cilia-driven fluid flow in the zebrafish pronephros, brain and Kupffer’s vesicle is required for normal organogenesis. Development. 2005;132:1907–1921. doi: 10.1242/dev.01772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manneville JB, Etienne-Manneville S. Positioning centrosomes and spindle poles: looking at the periphery to find the centre. Biol Cell. 2006;98:557–565. doi: 10.1042/BC20060017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Belmonte F, Mostov K. Regulation of cell polarity during epithelial morphogenesis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munson C, Huisken J, Bit-Avragim N, Kuo T, Dong PD, Ober EA, Verkade H, Abdelilah-Seyfried S, Stainier DY. Regulation of neurocoel morphogenesis by Pard6 gamma b. Dev Biol. 2008;324:41–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musch A. Microtubule organization and function in epithelial cells. Traffic. 2004;5:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2003.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura N, Rabouille C, Watson R, Nilsson T, Hui N, Slusarewicz P, Kreis TE, Warren G. Characterization of a cis-Golgi matrix protein, GM130. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1715–1726. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley BR. Gamma-tubulin: the microtubule organizer? Trends Cell Biol. 1992;2:1–5. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(92)90125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papan C, Campos-Ortega JA. On the formation of the neural keel and neural tube in the zebrafish Danio (Brachydanio) rerio. Roux’s Archives. 1994;203:178–186. doi: 10.1007/BF00636333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen LB, Veland IR, Schroder JM, Christensen ST. Assembly of primary cilia. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:1993–2006. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satir P, Christensen ST. Overview of structure and function of mammalian cilia. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:377–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.040705.141236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sfakianos J, Togawa A, Maday S, Hull M, Pypaert M, Cantley L, Toomre D, Mellman I. Par3 functions in the biogenesis of the primary cilium in polarized epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:1133–1140. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegrist SE, Doe CQ. Microtubule-induced cortical cell polarity. Genes Dev. 2007;21:483–496. doi: 10.1101/gad.1511207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorokin S. Centrioles and the formation of rudimentary cilia by fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells. J Cell Biol. 1962;15:363–377. doi: 10.1083/jcb.15.2.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawk M, Araya C, Lyons DA, Reugels AM, Girdler GC, Bayley PR, Hyde DR, Tada M, Clarke JD. A mirror-symmetric cell division that orchestrates neuroepithelial morphogenesis. Nature. 2007;446:797–800. doi: 10.1038/nature05722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Trotha JW, Campos-Ortega JA, Reugels AM. Apical localization of ASIP/PAR-3:EGFP in zebrafish neuroepithelial cells involves the oligomerization domain CR1, the PDZ domains, and the C-terminal portion of the protein. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:967–977. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X, Cheng Y, Luo Y, Shi X, Nelson S, Hyde DR. The zebrafish Pard3 ortholog is required for separation of the eye fields and retinal lamination. Dev Biol. 2004;269:286–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y, Eng CH, Schmoranzer J, Cabrera-Poch N, Morris EJ, Chen M, Wallar BJ, Alberts AS, Gundersen GG. EB1 and APC bind to mDia to stabilize microtubules downstream of Rho and promote cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:820–830. doi: 10.1038/ncb1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermann S, Weber K. Post-translational modifications regulate microtubule function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:938–947. doi: 10.1038/nrm1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Xiang X, Hammer JA., 3rd Motor proteins at the microtubule plus-end. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Weinberg RA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition: at the crossroads of development and tumor metastasis. Dev Cell. 2008;14:818–829. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolessi FR, Poggi L, Wilkinson CJ, Chien CB, Harris WA. Polarization and orientation of retinal ganglion cells in vivo. Neural Develop. 2006;1:2. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.