Abstract

TERMINAL FLOWER1 (TFL1)-like genes are highly conserved in plants and are thought to function in the maintenance of meristem indeterminacy. Recently, we described six maize (Zea mays) TFL1-related genes, named ZEA CENTRORADIALIS1 (ZCN1) to ZCN6. To gain insight into their functions, we generated transgenic maize plants overexpressing their respective cDNAs driven by a constitutive promoter. Overall, ectopic expression of the maize TFL1-like genes produced similar phenotypes, including delayed flowering and altered inflorescence architecture. We observed an apparent relationship between the magnitude of the transgenic phenotypes and the degree of homology between the ZCN proteins. ZCN2, -4, and -5 form a monophylogenetic clade, and their overexpression produced the strongest phenotypes. Along with very late flowering, these transgenic plants produced a “bushy” tassel with increased lateral branching and spikelet density compared with nontransgenic siblings. On the other hand, ZCN1, -3, and -6 produced milder effects. Among them, ZCN1 showed moderate effects on flowering time and tassel morphology, whereas ZCN3 and ZCN6 did not change flowering time but still showed effects on tassel morphology. In situ hybridizations of tissue from nontransgenic plants revealed that the expression of all ZCN genes was associated with vascular bundles, but each gene had a specific spatial and temporal pattern. Expression of four ZCN genes localized to the protoxylem, whereas ZCN5 was expressed in the protophloem. Collectively, our findings suggest that ectopic expression of the TFL1-like genes in maize modifies flowering time and inflorescence architecture through maintenance of the indeterminacy of the vegetative and inflorescence meristems.

Plant architecture is largely determined by the combined activity of the apical and axillary meristems, the population of self-renewing undifferentiated cells that generate organs (Prusinkiewicz et al., 2007). In annual monocot plants, such as maize (Zea mays), the shoot apical meristem (SAM) is positioned on the stem tip and produces lateral organs, like leaves, during vegetative growth. The duration of vegetative growth determines the final leaf number on the mature plant and is one measure of flowering time. After the floral transition, the SAM is converted into the inflorescence meristem, marking the onset of reproductive growth (Colasanti and Muszynski, 2009). Maize is monoecious, meaning that individual male and female flowers (florets in grasses) are formed on the same plant. The apical inflorescence meristem produces the male inflorescence or tassel, which bears staminate florets, while the female inflorescence or ear develops from a number of axillary meristems positioned in the leaf axil and bears pistilate florets. The floral transition signals the initiation of tassel development at the plant apex, which is followed by the initiation of ear development on axillary branches approximately 10 d later.

The floral transition is a finely tuned process controlled by converging genetic pathways in response to a number of environmental and endogenous signals (Boss et al., 2004; Bernier and Perilleux, 2005; Baurle and Dean, 2006; Jaeger et al., 2006). In Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), two closely related genes, FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) and TERMINAL FLOWER1 (TFL1), are key integrators of the floral transition pathways that have antagonistic functions in the floral transition (Kardailsky et al., 1999; Kobayashi et al., 1999). FT promotes flowering, whereas TFL1 represses the transition. A single amino acid difference between the FT and TFL1 proteins is sufficient to swap their functions from a floral activator to a floral repressor (Hanzawa et al., 2005). Both genes encode 20-kD proteins with homology to phosphatidylethanolamine-binding proteins (PEBPs). Biochemical analyses of mammalian PEBPs classified them as kinase inhibitors, suggesting that these proteins might function as modifiers of protein phosphorylation in signal transduction pathways (Banfield et al., 1998; Yeung et al., 1999; Banfield and Brady, 2000; Yeung et al., 2000).

Several studies indicate that the Arabidopsis FT protein and homologous FT-like proteins from other species function as mobile signals to activate the floral transition. The current model for FT function proposes that the FT protein is expressed in leaves and then moves through the phloem to the SAM, where it interacts with the basic Leu zipper (bZIP) transcription factor FLOWERING LOCUS D (FD). This interaction activates the expression of the meristem identity MADS box transcription factor APETALA1, triggering floral morphogenesis (Jaeger et al., 2006; Corbesier et al., 2007; Jaeger and Wigge, 2007; Turck et al., 2008; Zeevaart, 2008; Michaels, 2009).

The mode of TFL1 action is less clear. Mutant and transgenic analyses indicated that the Arabidopsis TFL1 gene regulates the indeterminacy of both vegetative and reproductive meristems throughout several stages of plant development (Shannon and Meeks-Wagner, 1991; Bradley et al., 1997). Accumulation of TFL1 mRNA is low during vegetative growth stages but is up-regulated during the floral transition, where it is first detected in axillary meristems and later in the central zone of the SAM. However, the TFL1 protein is more broadly distributed across shoot and axillary meristems, suggesting that the TFL1 protein can move from the site of its transcription in the central zone to the periphery of the meristems (Conti and Bradley, 2007). Like the FT protein, the TFL1 protein is also mobile, but it moves locally within the meristem, whereas FT can move longer distances (Giakountis and Coupland, 2008; Turck et al., 2008). The TFL1 protein also appears to be involved in trafficking proteins to specialized protein storage vacuoles in meristematic cells, possibly storing factors necessary for development (Sohn et al., 2007). TFL1 has also been shown to be involved in temperature sensing under temperate conditions (Strasser et al., 2009).

Proteins homologous to TFL1 are found in virtually all plant species. In general, the structure and function of TFL1-related proteins are greatly conserved (Kato et al., 1998; Pnueli et al., 1998; Jensen et al., 2001; Nakagawa et al., 2002; Carmel-Goren et al., 2003; Sreekantan et al., 2004; Chardon and Damerval, 2005; Esumi et al., 2005; Kotoda and Wada, 2005; Zhang et al., 2005; Boss et al., 2006; Guo et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2006; Argiriou et al., 2008; Datta et al., 2008; Igasaki et al., 2008; Elitzur et al., 2009; Hiroyuki et al., 2009; Mimida et al., 2009). However, there is evidence for diversification and specification of the function of different TFL1 family members. The closest homolog of TFL1, the ATC (for Arabidopsis CENTORADIALIS), gene does not participate in the regulation of meristem activity, and its function is not clear (Mimida et al., 2001). In Antirrhinum majus, the CENTRORADIALIS (CEN) gene is expressed in the inflorescence meristem after the floral transition, and cen null mutants produce terminal flowers but the timing of flowering is not affected, suggesting a function in inflorescence meristem maintenance but not the floral transition (Bradley et al., 1996; Cremer et al., 2001). In pea (Pisum sativum), two genes, LATE FLOWERING and DETERMINATE, maintain the indeterminacy of the SAM during vegetative growth and the inflorescence meristem during reproductive growth, respectively (Foucher et al., 2003). Hence, the single Arabidopsis TFL1 gene plays a role in vegetative and reproductive meristem function, whereas in other plant species, functioning in the vegetative and reproductive meristems appears to be maintained by separate TFL1-related genes.

Previously, we identified the expanded family of 25 PEBP-related genes in the maize genome named ZEA CENTRORADIALIS (ZCN). Within this family, six genes (ZCN1 to -6) encode proteins having the closest phylogenetic relationship to Arabidopsis TFL1 (Danilevskaya et al., 2008a). In this study, we investigated the functions of these six genes using a transgenic approach and RNA in situ hybridization. Our findings suggest functional diversification among the six maize TFL1-related genes. Overexpression of ZCN1, ZCN2, ZCN4, and ZCN5 produced transgenic plants that are late flowering and have tassels with an increased number of lateral branches and high spikelet density. These phenotypes suggest that these genes might be involved in the floral transition and maintenance of meristem indeterminacy. Overexpression of ZCN3 and ZCN6 had no effect on flowering time and only mild effects on tassel development, suggesting a more limited role in the regulation of meristem indeterminacy. The ZNC2 gene is the most likely ortholog of Arabidopsis TFL1, due to its overexpression phenotype, similar developmental expression pattern, and interaction with the DLF transcription factor protein in yeast two-hybrid studies. Expression of all six ZCN genes is associated with various components of vascular bundles, raising the possibility that they exert their influence through the regulation of hormone trafficking in vascular tissue.

RESULTS

Transgenic Plants Overexpressing TFL1-Like ZCN cDNAs Display Pleiotropic Phenotypes

The family of 25 maize PEBP-related ZCN genes forms three major clades, FT-like, MFT-like, and TFL1-like, which are named after their Arabidopsis homologous proteins (Danilevskaya et al., 2008a). To assess the functions of the ZCN genes, we generated transgenic maize events harboring constructs overexpressing the cDNA for 22 ZCN genes under the control of the constitutive ubiquitin promoter (Pro:UBI; Supplemental Table S1). Unexpectedly, expression of the FT-like ZCN genes severely retarded callus formation and growth; therefore, it was extremely difficult to generate transgenic plants from FT-like genes. MFT-like ZCN genes did not affect callus formation but did not produce obvious phenotypes and were not pursued further. The TFL1-like ZCN genes produced transgenic plants, and some of them displayed distinct phenotypes. In the greenhouse, T0 ZCN1 and ZCN2 transgenic events produced tall, late-flowering plants with bushy tassels and ample pollen shed that prompted us to further investigate this group (Supplemental Figs. S1 and S2). Only events expressing the transgene were selected for further analysis (Supplemental Fig. S3).

To confirm the original T0 observations, T3 populations segregating 1:1 transgenic and nontransgenic siblings were grown in the field. Expression of the transgene was confirmed in representative T3 plants (Supplemental Fig. S3). Phenotypic data were collected on flowering time (Table I) and tassel and ear traits (Table II). The magnitude of the overexpression phenotypes correlated with the phylogenetic relationship of the genes. The ZCN1, ZCN3, and ZCN6 genes from the same group induced relatively mild changes in transgenic plants (Fig. 1, A, C, and F). ZCN1 transgenic plants showed only a few days delay in flowering, producing on average one more leaf. ZCN3 and ZCN6 transgenic plants had no delay in flowering (Table I).

Table I. Flowering traits of ZCN1 to -6 transgenic maize plants.

All constructs were expressing cDNAs with the exception of ZCN4g, which was a genomic exon/intron fragment. Phenotypic data were collected from 40 to 50 individual nontransgenic (NTG) and transgenic (TG) siblings from three independent events in the field. Mean values and sd were calculated by linear regression using SAS. GDU, Growing degree units.

| Line | GDU to Shed | Shedding Duration (Date) | GDU to Silk | Leaf No. |

| NTG siblings | 1,514 ± 76 | 7/21–7/31 | 1,614 ± 86 | 18.0 ± 0.81 |

| TG Pro:UBI ZCN1 | 1,714 ± 64a | 7/30–8/09 | 1,754 ± 75a | 19.6 ± 0.81a |

| NTG siblings | 1,572 ± 77 | 7/22–7/30 | 1,625 ± 75 | 19.0 ± 0.79 |

| TG Pro:UBI ZCN2 | 2,087 ± 10a | 8/09–8/22 | 2,099 ± 11a | 22.4 ± 1.51a |

| NTG siblings | 1,624 ± 12 | 7/27–7/28 | 1,668 ± 21 | 19.6 ± 0.74 |

| TG Pro:UBI ZCN3 | 1,622 ± 48 | 7/26–7/30 | 1,656 ± 40 | 20.0 ± 0.20 |

| NTG siblings | 1,576 ± 44 | 7/24–7/28 | 1,630 ± 42 | 19.0 ± 0.14 |

| TG Pro:UBI ZCN4g | 2,168 ± 50a | 8/15–8/20 | 2,188 ± 36a | 22.4 ± 0.56a |

| NTG siblings | 1,557 ± 66 | 7/22–7/25 | 1,585 ± 65 | 20.2 ± 1.17 |

| TG Pro:UBI ZCN5 | 1,833 ± 21a | 7/31–8/14 | 1,841 ± 19a | 23.6 ± 2.54 a |

| NTG siblings | 1,656 ± 43 | 7/28–8/01 | 1,764 ± 62 | 16.5 ± 0.54 |

| TG Pro:UBI ZCN6 | 1,693 ± 41 | 7/28–8/01 | 1,765 ± 88 | 16.5 ± 0.54 |

Means are statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Table II. Tassel and ear traits of ZCN1 to -6 transgenic maize plants.

The experimental design and statistical analysis are the same as in Table I. Spikelet density was determined by manual counting of individual spikelets on 5 cm of the central rachis of the fully mature tassels after pollen shed. Spikelet row number was determined by counting the number of spikelets around the circumference of the ear at its midpoint. Spikelets per row were counted from the base to the tip of the ear along a file at silking. Two files of spikelets per ear were counted and averaged. Differences in spikelet number per ear row are shown in the last column.

| Line | Tassel |

Ear |

|||

| Branch No. | Spikelet Density | Increase Spikelet Density in TG | Spikelet Row No. | Spikelets per Row | |

| % | |||||

| NTG siblings | 13 ± 3 | 71.00 ± 6.16 | 16.58 ± 1.42 | 54.83 ± 5.51 | |

| TG Pro:UBI ZCN1 | 14 ± 3 | 114.92 ± 18.83a | 62 | 15.73 ± 1.32a | 55.27 ± 6.86 |

| NTG siblings | 10 ± 3 | 64.48 ± 5.39 | 15.81 ± 1.84 | 55.86 ± 4.69 | |

| TG Pro:UBI ZCN2 | 16 ± 4a | 98.40 ± 20.42a | 53 | 14.33 ± 1.54a | 58.87 ± 8.89a > 3 |

| NTG siblings | 12 ± 3 | 72.44 ± 10.12 | 15.22 ± 1.60 | 56.06 ± 4.25 | |

| TG Pro:UBI ZCN3 | 12 ± 3 | 82.96 ± 13.36a | 15 | 14.83 ± 1.77 | 58.10 ± 4.29b > 2 |

| NTG siblings | 11 ± 2 | 69.69 ± 9.89 | 16.11 ± 1.41 | 57.70 ± 4.61 | |

| TG Pro:UBI ZCN4g | 15 ± 3a | 106.86 ± 24.27a | 53 | 14.67 ± 1.52a | 56.80 ± 6.88 |

| NTG siblings | 14 ± 3 | 58.32 ± 12.06 | 14.32 ± 1.99 | 48.79 ± 6.41 | |

| TG Pro:UBI ZCN5 | 17 ± 4a | 98.32 ± 22.69a | 69 | 14.23 ± 1.42 | 63.00 ± 8.97a > 14 |

| NTG siblings | 8 ± 2 | 40.67 ± 6.49 | 14.30 ± 1.98 | 46.15 ± 10.11 | |

| TG Pro:UBI ZCN6 | 10 ± 2a | 53.83 ± 7.56a | 31 | 13.02 ± 1.79a | 41.36 ± 9.38b < 5 |

Means are statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Means are statistically significant at P < 0.1.

Figure 1.

Phenotypes of ZCN transgenic plants. A to F, Nontransgenic and transgenic siblings grown in the field. Images of nontransgenic plants and tassels are on the left, and nontransgenic ears are on the top. G to K, Phenotypes of nontransgenic and transgenic plants in the early background grown in the greenhouse. Bars = 10 cm.

Phenotypic data collected for tassel traits included total lateral branch number and spikelet density per 5 cm of the central spike (Table II). ZCN1 plants produced a characteristic bushy tassel phenotype due to a 62% increase in spikelet density and an increased number of lateral branches (Fig. 1A; Table II; Supplemental Fig. S4). Overexpression of ZCN3 and ZCN6 caused 15% and 31% increases in tassel spikelet density, respectively (Fig. 1, C and F; Table II). ZCN6 overexpression also increased lateral branch number. The ear traits recorded include the number of spikelet rows (files) around the circumference of the ear at its midpoint and the number of spikelets within the row (file) from the base to the tip of the ear. ZCN1 and ZCN6 transgenic ears had fewer spikelet rows compared with their nontransgenic siblings (12 versus 14; Table II). ZCN3 transgenic plants produced ears with a mild increase (two to three spikelets) per row, whereas ZCN6 transgenic plants showed an opposite effect, having five to six fewer spikelets per row. ZCN1 overexpression did not have a statistically significant effect on ear traits. It should be noted that ZCN1 and ZCN3 are duplicated genes sharing 96% amino acid identity; however, their effects on transgenic plant phenotypes are quite different.

ZCN2, ZCN4, and ZCN5 transgenic plants displayed the most severe phenotypes. Plants overexpressing these genes flowered up to 2 weeks later, producing four more leaves than nontransgenic siblings (Fig. 1, B, D, and E; Table I). Delayed flowering of ZCN5 transgenic plants was so severe that it was difficult to produce seeds, as it flowered very late in the growing season. In general, ZCN transgenic plants in this group produced tassels with three to four additional lateral branches than their nontransgenic siblings (Table II; Fig. 1, B, D, and E; Supplemental Fig. S2). ZCN2 and ZCN4 plants produced tassels with a 53% increase in spikelet density. The greatest increase in spikelet density was observed in ZCN5-overexpressing plants, which had a 69% increase compared with nontransgenic siblings. ZCN2, ZCN4, and ZCN5 ears also looked “skinnier” due to a reduction in spikelet row number, 12 rows compared with 14 rows in nontransgenic siblings (Table II). ZCN2 transgenic plants produced longer ears due to an increase of more than three spikelets per row, whereas ZCN4 did not affect ear length. ZCN5 transgenic plants had the strongest effect on ear length, with more than 14 additional spikelets per row.

ZCN1, ZCN2, ZCN4, and ZCN5 were transformed into Gaspe Flint, an early-flowering inbred (Fig. 1G) producing transgenic plants with even more dramatic phenotypes (Fig. 1, H–K). Nontransgenic sibling plants had five to six total leaves at flowering and had tassels with two to three lateral branches. Strikingly, transgenic plants produced three to four more leaves at flowering and had tassels with 10 to 20 additional branches. In this early-flowering background, ZCN5 again displayed the strongest effect on plant architecture. ZCN5 transgenic plants produced 10 leaves, almost doubling the total leaf number of control plants. Leaves from transgenic plants were also longer than leaves from nontransgenic siblings.

Overexpression of TFL1-Like ZCN Genes Affects Meristem Indeterminacy

The phenotypes of ZCN1, ZCN2, ZCN4, and ZCN5 transgenic plants suggested that meristem activity might be altered. For example, the late-flowering phenotype indicated the floral transition was delayed in ZCN transgenic plants. To test this hypothesis, the SAM was imaged at different stages of vegetative and reproductive growth. At the V4 stage, when plants had four fully expanded leaves, the SAMs of both nontransgenic and transgenic seedlings were in the vegetative growth state, initiating leaf primordia (Fig. 2, V4 stage). At the V6 stage, SAMs from nontransgenic plants had already transitioned to reproductive development and initiated a tassel primordium (Fig. 2, V6 stage). SAMs from ZCN3 and ZCN6 transgenic plants transitioned to reproductive development at a time similar to their nontransgenic siblings, consistent with no effect on flowering time for these two genes (Fig. 2, C and F). In contrast, SAMs from ZCN1, ZCN2, ZCN4, and ZCN5 transgenic plants were still in the vegetative growth stage at V6 and transitioned later to reproductive development (Fig. 2, A, B, D, and E). This is consistent with the increased leaf numbers and later flowering produced by these transgenic plants.

Figure 2.

SAM development in nontransgenic (NT) and ZCN transgenic (TG) plants. Representative images of shoot apices collected from V4-stage plants (left column) before and V6-stage plants (right column) after the floral transition of nontransgenic plants are shown. Nontransgenic apices are shown on the left side of each column. The vegetative apices have a smooth round shape, whereas transitioning apices have elongated rough shapes due to emerging branch meristems. A, ZCN1 transgenic line. B, ZCN2 transgenic line. C, ZCN3 transgenic line. D, ZCN4 transgenic line. E, ZCN5 transgenic line. F, ZCN6 transgenic line. Bars = 50 μm.

The inflorescence phenotypes of mature ZCN1, ZCN2, ZCN4, and ZCN5 transgenic plants suggested that the indeterminacy of meristems on the developing inflorescence was maintained for a longer period of time compared with nontransgenic sibling plants. To test this hypothesis, development of tassels and ears was observed in ZCN transgenic and nontransgenic siblings in the early-flowering Gaspe Flint background (Fig. 3). Examination of nontransgenic tassel primordia showed that the inflorescence meristem was collapsed after producing approximately 25 to 30 spikelets within a file along the central tassel rachis (Fig. 3A) and along the ear (Fig. 3F). Examination of transgenic tassel primordia showed that the inflorescence meristem had produced more than 30 spikelets but was still active, as determined by its translucent appearance, and continued to produce spikelet pair meristems (Fig. 3, B–E, tassels, and G–J, ears). The most extreme case was the ZCN5 transgenic plants, which produced more than 40 spikelets along a file in the ear while the inflorescence meristem was still active (Fig. 3J). ZCN5 transgenic plants also had tassel primordia with lateral branches as long as or longer than the central rachis, suggesting that the meristem at the tips of the lateral branches was still indeterminate (Fig. 3E). Thus, overexpressing ZCN1, ZCN2, ZCN4, and ZCN5 maintained the indeterminacy of the inflorescence meristem for a longer period, allowing the production of more lateral organs compared with nontransgenic siblings.

Figure 3.

Inflorescence meristem development in nontransgenic and ZCN transgenic plants. Representative images of immature tassels (A–E) and immature ears (F–J) collected from the ZCN transgenic lines in the early background grown in the greenhouse are shown. Tassel images are shown with the main rachis and the two longest lateral branches. White horizontal bars mark 10 spikelet meristems. A and F, nontransgenic inflorescences. B and G, ZCN1 inflorescences. C and H, ZCN2 inflorescences. D and I, ZCN4 inflorescences. E and J, ZCN5 inflorescence. Bars = 200 μm in A and E and 1 mm in B to D and F to J.

To understand the cause of the increase in spikelet density on transgenic tassels, we removed spikelets from the central tassel rachis of ZCN1 transgenic plants and found shorter internodes between spikelet pairs compared with nontransgenic plants (Supplemental Fig. S5). This observation suggested that shortened internodes are the cause of higher spikelet density in transgenic plants. Spikelet density on the central rachis was not influenced by rank, as no changes in rank were found.

Detection of TFL1-Like ZCN Transcription Domains by RNA in Situ Hybridization

To identify the temporal and spatial expression domains of TFL1-like ZCN genes, tissues were chosen for in situ hybridization according to our previous reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analyses (Danilevskaya et al., 2008a) and additional RT-PCR of dissected organs (Supplemental Fig. S6).

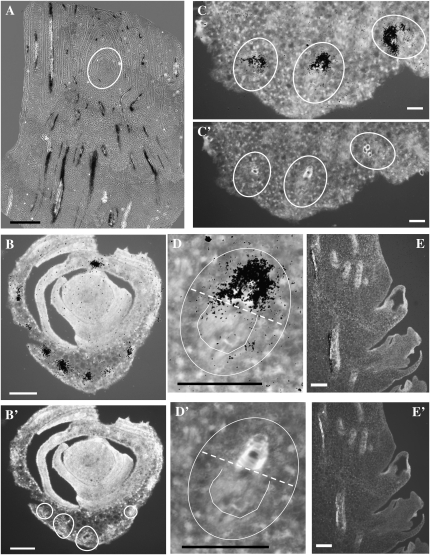

Given that ZCN1 and ZCN3 are expressed at vegetative and reproductive stages, V3 to V8 shoot apices and developing ears were used for in situ hybridization. ZCN1 and ZCN3 are duplicated genes sharing 90% identity at the nucleotide level (Danilevskaya et al., 2008a). For this reason, it was not possible to develop probes specific for each gene, so the results represent expression of both genes. RNA in situ hybridizations with control sense ZCN probes are shown in Supplemental Figure S7A. The ZCN1/3 antisense probe revealed strong signal in the vascular bundles in the stem of the shoot apex. No signal was detected in the SAM proper (Fig. 4A). Incipient leaf primordia enwrap the SAM as they develop and enclose each other within the shoot apex (Supplemental Fig. S8). The positions of leaf primordia in relation to the SAM are defined by their plastochron number, such that the newest arising primordium, closest to the SAM, is at position P1 while primordia that arose earlier are at positions P2, P3, P4, et cetera and are farther from the SAM. In V3 stage apices, vascular bundle differentiation first becomes evident in P2 leaf primordia. This can be visualized using UV autofluorescence of lignin in the secondary cell walls of protoxylem elements (Supplemental Fig. S8). In transverse sections of shoot apices, ZCN1/3 signals can be seen in P2 and older leaf primordia, where signals cluster over provascular cells (Fig. 4, B and B′). At higher magnification, ZCN1/3 hybridization signals were associated with lignified xylem vessels (Fig. 4, C, C′, D, and D′). In longitudinal sections of immature ears, ZCN1/3 signals were detected on the internal (adaxial) side of the vascular bundles, closer to the central axis of the ear that corresponds to xylem (Fig. 4, E and E′).

Figure 4.

RNA in situ hybridization with the ZCN1/3 probe. A to E, Hybridization signals of the ZCN1/3 antisense 35S-labeled probe. B′ to E′, UV light images for visualization of lignified vessels. A, Longitudinal section of the V3 vegetative shoot apex showing hybridization signals in the vasculature of developing leaves and the stem but the absence of detectable expression in the SAM (circle). B, Transverse section of the shoot apex at the V3 stage showing discrete signal over the vascular bundles starting in the second leaf primordium. B′, Expression of ZCN1/3 coincides with vessel lignification in the xylem. C and C′, Higher magnification of the transverse section of the leaf primordium showing signal over three vascular bundles (circles). D and D′, 20× magnification of an individual vascular bundle from the leaf primordium showing signal in the cells surrounding the lignified vessel of the protoxylem. The dashed lines mark the border between the xylem and the phloem. The U-shaped lines mark the phloem. E and E′, Longitudinal section of the ear base showing hybridization signal on the internal (adaxial) side of the vascular bundle corresponding to xylem. Bars = 100 μm in A, 500 μm in B, and 10 μm in C to E.

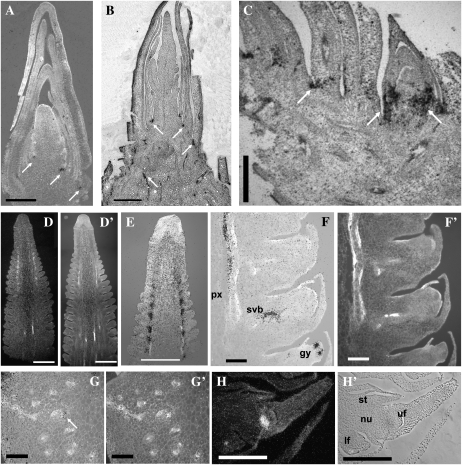

Because ZCN2 is expressed in both vegetative and reproductive stages, the ZCN2 probe was hybridized to V3 and V8 shoot apices and developing ears (Fig. 5). In the V3 apex, the hybridization signal was detected in the axils of each leaf, presumably overlapping the location of axillary meristem initiation (Fig. 5A). In the reproductive V8 apex, after the tassel primordia had initiated, the ZCN2 signal persisted in the leaf axils (Fig. 5B) and at the base of the axillary branch (Fig. 5C) but not in the tassel primordia (Fig. 5B). ZCN2 signal was also associated with vascular bundles in the stem below the tassel primordium, but no signal was detected in leaf vascular bundles, distinguishing ZCN2 from ZCN1/3 expression. It is important to point out that no ZCN2 signal was detected in the SAM or the tassel primordia by RNA in situ hybridization, consistent with RT-PCR results (Supplemental Fig. S6).

Figure 5.

RNA in situ hybridization with the ZCN2 probe. A to H, Hybridization signals of the ZCN2 antisense 35S-labeled probe. Signals are black in bright-field (A–C, E, F, and H) and white in dark-field (D and H) images. White arrows point to hybridization signal. D′ to H′, UV light images for visualization of lignified vessels. lf, Lower floret; nu, nucellus; st, stamen; uf, upper floret. A, Longitudinal section of the V3 vegetative shoot apex showing hybridization signal in the axils of leaf primordia. B, Longitudinal section of the V8 reproductive shoot apex with a tassel primordium showing hybridization signal in the leaf axils and stem vasculature. C, Longitudinal section of V8 reproductive shoot apex with axillary meristem (the ear bud) showing hybridization signals at its base. D and E, Longitudinal sections of the ear tip showing hybridization signal in cells on the adaxial side of eight to nine consecutive spikelet meristems in the area where the spikelet pair meristems are branching into the spikelet meristems. F and G, Longitudinal (F) and transverse (G) sections of the ear base showing hybridization signal on the internal (adaxial) side of the vascular bundle corresponding to the protoxylem (px). Some signal was localized to spikelet vascular bundles (svb) and the gynoecium (gy). H, Longitudinal section of the developing floret showing signal in the nucellus and the stamen primordia of the upper floret and in a group of cells in the lower floret. Bars = 200 μm in A and B, 20 μm in C, E, and H, 500 μm in D, and 10 μm in F and G.

In developing ears, the ZCN2 gene has a complex pattern of expression. The ear develops in a gradient from the tip to the base with more developed floral organs occurring at the base (Cheng et al., 1983). The apical inflorescence meristem initiates spikelet pair meristems on its flanks, which later branch into two spikelet meristems. The spikelet meristem branches into two floret meristems, one upper and one lower. The upper floret meristems mature into florets bearing ovules, while the lower floret meristems abort. In apical portions of immature ears, ZCN2 signal was detected at the base of the uppermost eight to nine consecutive spikelet meristems, possibly indicating the position where spikelet pair meristems are branching into spikelet meristems (Fig. 5, D, D′, and E). In this zone, the emerging protoxylem, as visualized by lignified vessels, also appeared to overlap with ZCN2 signal. At the base of the ear, where florets were more differentiated, ZCN2 expression was detected in spikelet vascular bundles and the gynoecium as two clusters of signal, possibly marking the upper and lower floret meristems (Fig. 5, F and F′; Supplemental Fig. S9). Upon differentiation of the floret, ZCN2 signal appeared in the nucellus of the ovule (Fig. 5, H and H′) and in the stamen primordia of the upper floret (Supplemental Fig. S10). ZCN2 signal was also seen in the pith of the developing ears on the inner (adaxial) side of the bundle vessel (Fig. 5, F, F′, G, and G′), indicating that ZCN2 is presumably transcribed in protoxylem or tracheids. Overall, ZCN2 has a complex developmental pattern of expression in localized domains mostly associated with axillary branches, ears and florets, and the xylem of vascular bundles.

ZCN4 and ZCN5 are expressed after the floral transition in reproductive organs, with transient expression in tassel primordia and continuous expression in developing ears (Supplemental Fig. S6). Therefore, probe was hybridized to the apical and basal portions of developing ears. The ZCN4 probe revealed hybridization to vascular bundles in longitudinal sections of developing ear apices (Fig. 6, A and A′) and bases (Fig. 6, B and B′). Hybridization to transverse sections showed ZCN4 signals in lignified xylem vessels that could be fiber tracheids (Fig. 6, C and C′).

Figure 6.

RNA in situ hybridization of the ZCN4 and ZCN5 probes. A and B, Hybridization signal of ZCN4. D to G, Hybridization signal of ZCN5. Signals are white in dark-field (A and D) and black in bright-field (B, C, and E–G) images. A′ to G′, UV light images for visualization of lignified vessels. A and B, Longitudinal sections of ear tip (A) and base (B) showing ZCN4 hybridization signal over well-developed vascular bundles. C, Transverse section of the ear base showing ZCN4 signal in a group of cells that are tightly wrapped around the lignified xylem vessels. D, Longitudinal section of the ear tip showing ZCN5 signal in cells underlying the emerging spikelet pair meristems as well as the first eight to 10 spikelet meristems. Near the position of the 20th spikelet from the ear tip, ZCN5 signal reappeared in the vascular bundles. E, Longitudinal section of the ear tip at 20× magnification. The first cluster of ZCN5-labeled cells was located inside the apical inflorescence meristem six to eight cell layers underneath the epidermis (black arrows). There is a second region of small clusters of signal consisting of one or two cells located below the emerging spikelet pair meristems. Near the region where the spikelet pair meristems arise, clusters of labeled cells are located at the base of each spikelet pair meristem. F, Longitudinal section of the ear base showing ZCN5 signal on the outer (abaxial) side of the vascular bundles corresponding to the phloem. G, Transverse section of the ear tip showing strong ZCN5 signal in the phloem underneath each spikelet pair meristem. Bars = 500 μm in A and D and 10 μm in B, C, and E to G.

Strong ZCN5 signal was detected at the base of the visible eight to 10 spikelet pair meristems, and expression diminished in the region where spikelet meristems formed (Fig. 6, D and D′). Signal first appeared near the apical tip of the ear, six to eight cell layers from the surface, which might correspond to the zone of the inflorescence meristem that predicts the location of spikelet pair meristem formation (Fig. 6E). Tiny clusters of label could be traced down under each spikelet meristem. Farther from the ear apex, ZCN5 signal reappeared in the outer (abaxial) side of vascular bundles corresponding to phloem. ZCN5 expression was located underneath each individual spikelet, possibly marking the vasculature subtending the developing florets (Fig. 6, F and F′). Clusters of ZCN5 signal were also found beneath some spikelets associated with the outer side of the vascular bundles, suggesting expression in the developing protophloem (Supplemental Fig. S11). Hybridization to transverse sections of the immature ear confirmed ZCN5 signal in the phloem (Fig. 6, G and G′). No expression was found within the florets at any stage. Hence, ZCN5 expression was limited to the nascent and developed vasculature and, more specifically, to the phloem.

Hybridization with the ZCN6 probe proved to be the most difficult for RNA in situ hybridization. According to our previous RT-PCR results, ZCN6 is weakly expressed in the ear bud and in the embryo (Supplemental Fig. S6). RNA in situ hybridization was performed with the ear primordia at V7, and weak signals were seen beneath spikelet meristems and husks (Supplemental Fig. S7B).

Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay of ZCN Protein Interactions with the DLF1 Transcription Factor

Ectopic expression of specific ZCN genes delayed flowering in transgenic plants. The late-flowering and bushy-tassel phenotypes are reminiscent of the phenotype characteristic of delayed flowering1 (dlf1) mutants (Muszynski et al., 2006). In Arabidopsis, ectopic expression of AtTFL1 also causes late flowering (Ratcliffe et al., 1998). It was proposed that the negative effect of the TFL1 protein on flowering time might be due to competition with the floral activator FT for their common target, the FD transcription factor that is activated by FT (Ahn et al., 2006). In maize, the bZIP transcription factor DLF1 functions as a floral activator in a manner similar to FD (Muszynski et al., 2006; Danilevskaya et al., 2008a, 2008b). We used the yeast two-hybrid assay to test for interaction of DLF1 with six ZCN proteins in reciprocal combinations of bait and prey plasmids (Table III; Supplemental Fig. S12). A strong and repeatable interaction was only detected between DLF1 and ZCN2 in reciprocal plasmid combinations, suggesting that the ZCN2 gene might play a role orthologous to the Arabidopsis TFL1 gene.

Table III. Yeast two-hybrid interactions between DLF1 and ZCN proteins.

Interactions were assessed by transformed yeast colony growth on the synthetic dextrose/−Leu/−Trp/−His dropout medium (Supplemental Fig. S12) using reciprocal combinations of the bait pGBKT7 vector and the prey pGADT7 vector with insertions of the tested cDNAs. “Yes” indicates interaction in both reciprocal combinations, and “no” indicates no interaction or interaction only in one combination.

| Protein | DLF1 | ZCN1 | ZCN2 | ZCN3 | ZCN4 | ZCN5 | ZCN6 |

| DLF | Yes | ||||||

| ZCN1 | No | No | |||||

| ZCN2 | Yes | No | |||||

| ZCN3 | No | No | |||||

| ZCN4 | No | No | |||||

| ZCN5 | No | No | |||||

| ZCN6 | No | No |

DISCUSSION

Transgenic TFL1-Like ZCN Plants Show a Range of Modifications to Flowering Time and Inflorescence Architecture

Six of the maize ZCN genes (ZCN1 to -6) belong to the TFL1-like family, whose members have been shown to function in the regulation of flowering time and the maintenance of meristem indeterminacy in diverse plant species (Bradley et al., 1996, 1997; Pnueli et al., 1998; Nakagawa et al., 2002; Carmel-Goren et al., 2003; Foucher et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2005). In this study, we made an attempt to unravel the functions of the maize TFL1-like genes using a transgenic approach and RNA in situ hybridization.

Our results indicate that the duration of the vegetative growth stage of the SAM is prolonged by overexpression of several ZCNs, leading to a later floral transition and delay in flowering (Fig. 1). In addition, the indeterminacy of the inflorescence meristem appears to be significantly extended by overexpression of a single ZCN gene, resulting in increased branching in both the tassel and ear (Fig. 1). However, each ZCN gene had a unique and distinct effect on the architecture of mature transgenic maize plants. The strongest phenotypes were produced by the ZCN2, ZCN4, and ZCN5 genes, which form a monophyletic clade with the rice (Oryza sativa) RCN2 and RCN4 genes (Danilevskaya et al., 2008a). Transgenic plants from this group have a 2- to 3-week delay in flowering time and produce three to four additional leaves. In our standard Midwest growing conditions, some transgenic plants began shedding pollen in the middle of August, when their nontransgenic siblings were already at the grain-filling stage. Predictably, SAMs from these transgenic plants did not exit vegetative growth and transition until V7 to V8 (Fig. 2). Similar to their strong effect on flowering time, overexpression of this group of ZCNs had striking effects on tassel architecture, producing more and longer lateral branches with a higher spikelet density. This effect was more pronounced when the transgene constructs were transformed into an early-flowering line (Fig. 1, I–K). These findings indicate that overexpression of ZCN2, ZCN4, and ZCN5 delayed the floral transition of the SAM and prolonged the indeterminacy of the inflorescence meristem.

Overexpression of ZCN1, ZCN3, and ZCN6, which group with rice RCN1 and RCN3 (Danilevskaya et al., 2008a), produced mild effects on flowering time and inflorescence architecture. Of this group, only ZCN1 affected both flowering and tassel architecture similar to the ZCN2-4-5 group (Fig. 1; Supplemental Figs. S1 and S4). Overexpression of ZCN3 and ZCN6 did not affect flowering time and had mild effects on tassels. Surprisingly, although ZCN1 and ZCN3 are duplicated genes and their proteins differ by only seven amino acids, overexpression of ZCN3 had no effect on flowering time and only a mild increase in tassel spikelet density.

The strength of transgenic phenotypes may be arranged in the following order: ZCN5 > ZCN2 > ZCN4 > ZCN1 > ZCN3 > ZCN6. ZCN5 transgenic plants produced the longest ears, which might be of interest for increasing grain yield. However, late flowering is considered a negative agronomic trait, which prevents immediate usage of these transgenic plants for practical purposes. Four of the six TFL1-like maize genes appear to share some redundancy in the regulation of the floral transition and meristem maintenance. However, ZCN3 and ZCN6 have no effect on flowering time, suggesting that they may have evolved separate functions.

ZCN transgenic phenotypes are similar to the dramatic morphological changes induced by TFL-like genes in other plants. Ectopic expression in Arabidopsis of its own TFL1 and numerous TFL1-like genes from other species produced transgenic plants with late-flowering phenotype and highly branched inflorescences (Ratcliffe et al., 1998; Jensen et al., 2001; Nakagawa et al., 2002; Pillitteri et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2005; Guo et al., 2006; Carmona et al., 2007). In rice, ectopic expression of RCN1, RCN2, and RCN3 caused late flowering and more branched and densely packed panicles (Nakagawa et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2005), similar to our observation in maize. Branch initiation and outgrowth is controlled, in part, by the action of several hormones, including auxin, cytokinin, and strigolactone (McSteen, 2009). The common phenotype of increased axillary branching in TFL1-like transgenic plants suggests that these effects are mediated through possible interactions with hormones controlling shoot branching.

Expression of TFL1-Like ZCN Genes Is Associated with Vascular Tissue

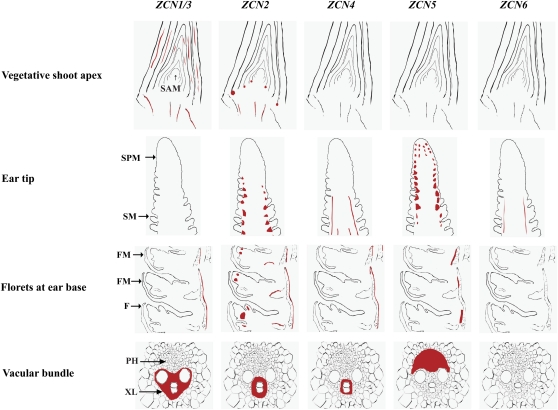

As discussed above, ZCN1 to -6 overexpression in transgenic plants appears to prolong meristem indeterminacy; however, our RNA in situ experiments revealed no ZCN1 to -6 mRNA in either vegetative or reproductive meristems. Expression of all six TFL1-like ZCN genes was found in the vascular bundles, but each gene had unique temporal and spatial patterns, which are summarized in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Summary of the expression domains of ZCN genes. The areas where mRNA was detected for each ZCN gene are shown in red. F, Floret; FM, floral meristem; PH, phloem; SM, spikelet meristem; SPM, spikelet pair meristem; XL, xylem.

Based on their developmental expression patterns, the ZCN1 to -6 genes fall into two categories: those expressed during vegetative and reproductive stages (ZCN1/3 and ZCN2), and those whose expression is limited to the reproductive stage (ZCN4, ZCN5, and ZCN6; Supplemental Fig. S6). In vegetative shoot apices, ZCN1/3 are expressed in vascular bundles of the stem and the P2 leaf, coinciding with the appearance of the first lignified xylem vessels corresponding to the protoxylem. These observations may indicate that ZCN1/3 are involved in the determination of provascular cell identity in vegetative tissues such as stems and leaves. It is worthwhile to note that the Arabidopsis ATC gene, the closest homolog of AtTFL1, is expressed in the hypocotyl vasculature in 2-week-old plants and is not expressed in meristems, displaying a different pattern from TFL1 (Mimida et al., 2001). ATC null mutants do not have an early-flowering phenotype, as do TFL1 mutants, and thus do not control flowering time. However, ATC-overexpressing transgenic plants showed late-flowering and extra-branching phenotypes similar to the TFL1-overexpressing transgenic plants (Mimida et al., 2009). This result suggests that despite their sequence similarity, the ATC and TFL1 proteins appear to have divergent biological functions, although the proteins have similar biochemical annotations. Hence, since Arabidopsis ATC, maize ZCN1/3, and rice RCN1 (Zhang et al., 2005) are expressed in vegetative stage vasculature, they seem to represent a subgroup of TFL1-like proteins that likely do not directly control flowering time but rather might be involved in vasculature development.

The ZCN2 gene exhibits the most complex expression pattern. In vegetative apices, ZCN2 is expressed in the axils of leaf primordia as distinct compact spots but not in the SAM (Fig. 7). TFL1-like genes with a similar expression pattern during vegetative growth can be found in different species, including rice RCN3 (Zhang et al., 2005), tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) CET2 and CET4 (Amaya et al., 1999), pepper (Capsicum annuum) FASCICULATE (Elitzur et al., 2009), lotus (Lotus japonicus) Ljcen1 (Guo et al., 2006), and the founder gene Arabidopsis TFL1 (Conti and Bradley, 2007). However, after entering the reproductive stage, their expression patterns diverge. Lotus Ljcen1 and Arabidopsis TFL1 mRNA appear in the inner cells of the shoot inflorescence meristem, and at later stages of development, TFL1 mRNA can be seen in the vascular bundle (Conti and Bradley, 2007). In contrast, tobacco CET2 and CET4 continue to express in axillary meristems and no signal appears in the apical meristem, suggesting that their functions are limited to axillary meristem development (Amaya et al., 1999). ZCN2 expression is limited to the base of axillary meristems that produce the maize female inflorescence, the ear. ZCN2 expression was not detected in developing tassels (Supplemental Fig. S6), supporting a specific role in ear development.

In the developing ear, ZCN2, ZCN4, and ZCN5 demonstrate a consecutive sequence of expression (Fig. 7). ZCN5 is the first gene of this group expressed in the tip of the ear in the region of the inflorescence meristem where initiation of spikelet pair meristems occurs. Its expression diminishes in the zone where spikelet pair meristems branch into spikelet meristems. In this region, ZCN2 expression appears in groups of cells underlying eight to nine spikelet meristems that overlap with the emerging protoxylem. ZCN4 expression is first detected in this same region, and expression persists in vascular bundles along the full length of the developing ear, being tightly associated with the central lignified vessels of the xylem.

In the more developed ear base, ZCN5 expression is detected again in the phloem of the vascular bundles underneath each individual floret, possibly specifying the conducting tissue for the developing florets. In the ear pith, ZCN2 is transcribed in the protoxylem on the adaxial side of the vascular bundles. In addition, the expression of ZCN2 can be found in various components of the developing florets, namely in the floret vascular bundles, in the floret meristem, in the nucellus of the developing ovule, and in the stamen primordia. The location of ZCN2 and ZCN5 expression coincides with the position of future bundle vessel plexuses between major vessel bundles and floret vessel bundles. Comparative analysis of ZCN gene expression showed that each gene apparently displays a unique developmental pattern, with each gene expressed in specific groups of cells within a vascular bundle (Fig. 7).

ZCN2 Displays Features Consistent with an Orthologous Function to Arabidopsis TFL1

A late-flowering phenotype was induced by overexpression of ZCN1, -2, -4, and -5. According to the Arabidopsis genetic model, flower development is initiated when the bZIP transcription factor, FD, is activated by interaction with the PEBP protein, FT (Abe et al., 2005). The TFL1 protein, which is also a PEBP protein, is proposed to compete with FT, preventing activation of the FD transcription factor (Ahn et al., 2006). In maize, dlf1 is an activator of the floral transition and is thought to function in a similar manner as FD in Arabidopsis (Muszynski et al., 2006; Danilevskaya et al., 2008a, 2008b). Using the yeast two-hybrid assay, only ZCN2 was found to interact with the DLF protein, providing a reasonable explanation for the late-flowering phenotype of transgenic plants. One could envision that in overexpressing plants, ZCN2 is competing with a putative maize FT to activate the DLF protein. The excess of ZCN2 protein in the transgenic plants would likely outcompete the putative maize FT, thereby delaying the activation of DLF, leading to late flowering.

However, ZCN1, -4, and -5 transgenic plants also induced late flowering, but ZCN1, -4, and -5 proteins do not interact with DLF1, suggesting that other unknown components are required for interaction in planta. This is not surprising, as it is well established that flowering time is controlled by a complex network of genetic pathways and that there may be other targets for ZCN genes. So far, ZCN2 seems to behave orthologously to the Arabidopsis TFL1 gene in controlling flowering time, but its expression in the female inflorescence after the floral transition suggests a novel function in floret development.

Overexpression of ZCN genes has a major impact on meristem indeterminacy, resulting in an increase of lateral organ formation (more branches and spikelets) in transgenic plants. However, none of these genes is expressed in the meristem of normal nontransgenic plants; rather, their expression is associated with the vasculature. One explanation for this paradox might be that ZCN proteins are mobile, similar to Arabidopsis FT, which moves via the phloem from the leaves to the SAM. which is the site of its function (Jaeger et al., 2006; Corbesier et al., 2007). Another explanation is that ZCN genes control the movement of other substances via the vasculature such as hormones. These ideas are not mutually exclusive but require a significant amount of future experimentation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

T-DNA Constructs and Plant Transformation

Gateway technology was used for vector construction. Full-length cDNA sequences of the ZCN1 to -6 genes were integrated between the ubiquitin promoter and PinII terminators and cointegrated with JT vectors as described previously (Unger et al., 2001; Cigan et al., 2005). Plasmids were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LBA4404 and used to transform Hi-Type II maize (Zea mays) embryos. Typically, 20 independent events were generated for each construct. Single-copy T-DNA integration events that expressed transgenes were used for further characterization and crosses (Supplemental Fig. S3). Segregating populations from the T3 generation from the primary transformed lines were grown in the field in Iowa. Transgenic plants were identified by leaf painting with herbicide (2% Liberty). Two independent events were analyzed for each construct. Phenotypic data were collected for 30 to 40 individual plants per event.

Field Phenotype Data Collection

Vegetative growth stages (V1–V9) were defined according to the appearance of the leaf collar of the uppermost leaf (Ritchie et al., 1997). Transgenic flowering time notes were collected in the field. Measurement of total leaf number was done by marking the fifth leaf and the tenth leaf when they first fully expanded. The times of first pollen shed and first silk emerged were recorded in the field and converted to growing degree units (GDU) according the formula GDU = (H + L)/2 − B, where H and L are the daily high and low temperatures and B = 50°F (Ritchie et al., 1997).

Statistical Analysis

Mean values and sd were calculated by linear regression using SAS Enterprise Guide 3.0 (SAS Institute) and the linear model ANOVA procedure in SAS. The difference in flowering time was tested by two-way ANOVA, taking the events and the presence or absence of the transgene as the two potential sources of variation. Tukey's family error rate was chosen for one-way multiple comparisons, with P value levels of significance (α-level) equal to 0.05 and 0.1.

Tissue Imaging

Vegetative and reproductive apices and immature ears were dissected and fixed in 50% acetic acid. Images were taken with a Nikon SMZ1500 microscope and a Nikon DXM1200 digital camera.

In Situ Hybridization

In situ hybridizations were performed by the Phylogeny Company (http://www.phylogenyinc.com). Tissues were sampled from the public B73 inbred line. Riboprobes were 35S-radiolabeled. For each probe/tissue combination, four antisense and two sense slides were prepared. Each slide contained a minimum of four to six tissue sections, depending on the size of the tissue. For each hybridization, the two antisense and one sense slides were developed at 1 week and then at 2 weeks of exposure. Images were taken for the typical comprehensive examples.

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers EU241917 (ZCN1), EU241918 (ZCN2), EU241919 (ZCN3), EU241920 (ZCN4), EU241921 (ZCN5), and EU241922 (ZCN6).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. ZCN1 transgenic tassels in the greenhouse.

Supplemental Figure S2. ZCN2 transgenic tassels in the greenhouse.

Supplemental Figure S3. Transgene and native gene expression in T0 leaf blade (RT-PCR).

Supplemental Figure S4. ZCN1 transgenic tassels in the field.

Supplemental Figure S5. Internode distance between spikelets in nontransgenic and ZCN1 transgenic tassels.

Supplemental Figure S6. ZCN gene expression in dissected organs (RT-PCR).

Supplemental Figure S7. Sense controls (A) and ZCN6 in situ hybridization to immature ears (B).

Supplemental Figure S8. Longitudinal and transverse sections of vegetative shoot apices.

Supplemental Figure S9. RNA in situ hybridization of the ZCN2 probe to the ear base.

Supplemental Figure S10. RNA in situ hybridization of the ZCN2 probe to the developing female spikelet.

Supplemental Figure S11. RNA in situ hybridization of the ZCN5 probe to the developing protophloem.

Supplemental Figure S12. Yeast two-hybrid assay of ZCN and DLF protein interaction.

Supplemental Table S1. Transformation efficiency of the ProUbi:ZCN constructs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Lawrence Stiner and Rajeev Gupta for vector construction, Deping Nu for transformation, Will Stork for technical assistance, and Mark Chamberlin for help with microscope imaging. The manuscript was significantly improved due to critical comments from Mike Muszynski, Norbert Brugiere, Jeff Habben, and Laura Appenzeller.

References

- Abe M, Kobayashi Y, Yamamoto S, Daimon Y, Yamaguchi A, Ikeda Y, Ichinoki H, Notaguchi M, Goto K, Araki T. (2005) FD, a bZIP protein mediating signals from the floral pathway integrator FT at the shoot apex. Science 309: 1052–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn JH, Miller D, Winter VJ, Banfield MJ, Lee JH, Yoo SY, Henz SR, Brady RL, Weigel D. (2006) A divergent external loop confers antagonistic activity on floral regulators FT and TFL1. EMBO J 25: 605–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaya I, Ratcliffe OJ, Bradley DJ. (1999) Expression of CENTRORADIALIS (CEN) and CEN-like genes in tobacco reveals a conserved mechanism controlling phase change in diverse species. Plant Cell 11: 1405–1418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argiriou A, Michailidis G, Tsaftaris AS. (2008) Characterization and expression analysis of TERMINAL FLOWER1 homologs from cultivated allotetraploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) and its diploid progenitors. J Plant Physiol 165: 1636–1646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banfield MJ, Barker JJ, Perry AC, Brady RL. (1998) Function from structure? The crystal structure of human phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein suggests a role in membrane signal transduction. Structure 6: 1245–1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banfield MJ, Brady RL. (2000) The structure of Antirrhinum centroradialis protein (CEN) suggests a role as a kinase regulator. J Mol Biol 297: 1159–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baurle I, Dean C. (2006) The timing of developmental transitions in plants. Cell 125: 655–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier G, Perilleux C. (2005) A physiological overview of the genetics of flowering time control. Plant Biotechnol J 3: 3–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss PK, Bastow RM, Mylne JS, Dean C. (2004) Multiple pathways in the decision to flower: enabling, promoting, and resetting. Plant Cell (Suppl) 16: S18–S31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss PK, Sreekantan L, Thomas MR. (2006) A grapevine TFL1 homologue can delay flowering and alter floral development when overexpressed in heterologous species. Funct Plant Biol 33: 31–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley D, Carpenter R, Copsey L, Vincent C, Rothstein S, Coen E. (1996) Control of inflorescence architecture in Antirrhinum. Nature 379: 791–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley D, Ratcliffe O, Vincent C, Carpenter R, Coen E. (1997) Inflorescence commitment and architecture in Arabidopsis. Science 275: 80–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmel-Goren L, Liu YS, Lifschitz E, Zamir D. (2003) The SELF-PRUNING gene family in tomato. Plant Mol Biol 52: 1215–1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona MJ, Calonje M, Martínez-Zapater JM. (2007) The FT/TFL1 gene family in grapevine. Plant Mol Biol 63: 637–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chardon F, Damerval C. (2005) Phylogenomic analysis of the PEBP gene family in cereals. J Mol Evol 61: 579–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng PC, Greyson RI, Walden DB. (1983) Organ initiation and the development of unisexual flowers in the tassel and ear of Zea mays. Am J Bot 70: 450–462 [Google Scholar]

- Cigan AM, Unger-Wallace E, Haug-Collet K. (2005) Transcriptional gene silencing as a tool for uncovering gene function in maize. Plant J 43: 929–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colasanti J, Muszynski M. (2009) The maize floral transition. The Maize Handbook; Springer-Verlag, New York, pp 41–55 [Google Scholar]

- Conti L, Bradley D. (2007) TERMINAL FLOWER1 is a mobile signal controlling Arabidopsis architecture. Plant Cell 19: 767–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbesier L, Vincent C, Jang S, Fornara F, Fan Q, Searle I, Giakountis A, Farrona S, Gissot L, Turnbull C.et al (2007) FT protein movement contributes to long-distance signaling in floral induction of Arabidopsis. Science 316: 1030–1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer F, Lonnig WE, Saedler H, Huijser P. (2001) The delayed terminal flower phenotype is caused by a conditional mutation in the CENTRORADIALIS gene of snapdragon. Plant Physiol 126: 1031–1041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilevskaya ON, Meng X, Hou Z, Ananiev EV, Simmons CR. (2008a) A genomic and expression compendium of the expanded PEBP gene family from maize. Plant Physiol 146: 250–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilevskaya ON, Meng X, Selinger DA, Deschamps S, Hermon P, Vansant G, Gupta R, Ananiev EV, Muszynski MG. (2008b) Involvement of the MADS-box gene ZMM4 in floral induction and inflorescence development in maize. Plant Physiol 147: 2054–2069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Basu D, Mukherjee K. (2008) PTC-1: a homologue of TFL1/CEN involved in the control of shoot architecture in Beta palonga. Curr Sci 94: 89–96 [Google Scholar]

- Elitzur T, Nahum H, Borovsky Y, Pekker I, Eshed Y, Paran I. (2009) Co-ordinated regulation of flowering time, plant architecture and growth by FASCICULATE: the pepper orthologue of SELF PRUNING. J Exp Bot 60: 869–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esumi T, Tao R, Yonemori K. (2005) Isolation of LEAFY and TERMINAL FLOWER 1 homologues from six fruit tree species in the subfamily Maloideae of the Rosaceae. Sex Plant Reprod 17: 277–287 [Google Scholar]

- Foucher F, Morin J, Courtiade J, Cadioux S, Ellis N, Banfield MJ, Rameau C. (2003) DETERMINATE and LATE FLOWERING are two TERMINAL FLOWER1/CENTRORADIALIS homologs that control two distinct phases of flowering initiation and development in pea. Plant Cell 15: 2742–2754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giakountis A, Coupland G. (2008) Phloem transport of flowering signals. Curr Opin Plant Biol 11: 687–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Zhao Z, Chen J, Hu X, Luo D. (2006) A putative CENTRORADIALIS/TERMINAL FLOWER 1-like gene, Ljcen1, plays a role in phase transition in Lotus japonicus. J Plant Physiol 163: 436–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanzawa Y, Money T, Bradley D. (2005) A single amino acid converts a repressor to an activator of flowering. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 7748–7753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroyuki S, Dany H, Hidenori S, Takato K. (2009) Identification and characterization of FT/TFL1 gene family in cucumber. Breed Sci 59: 3–11 [Google Scholar]

- Igasaki T, Watanabe Y, Nishiguchi M, Kotoda N. (2008) The FLOWERING LOCUS T/TERMINAL FLOWER 1 family in Lombardy poplar. Plant Cell Physiol 49: 291–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger KE, Graf A, Wigge PA. (2006) The control of flowering in time and space. J Exp Bot 57: 3415–3418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger KE, Wigge PA. (2007) FT protein acts as a long-range signal in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol 17: 1050–1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen CS, Salchert K, Nielsen KK. (2001) A TERMINAL FLOWER1-like gene from perennial ryegrass involved in floral transition and axillary meristem identity. Plant Physiol 125: 1517–1528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardailsky I, Shukla VK, Ahn JH, Dagenais N, Christensen SK, Nguyen JT, Chory J, Harrison MJ, Weigel D. (1999) Activation tagging of the floral inducer FT. Science 286: 1962–1965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H, Honma T, Goto K. (1998) CENTRORADIALIS/TERMINAL FLOWER 1 gene homolog is conserved in N. tabacum, a determinate inflorescence plant. J Plant Res 111: 289–294 [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Han MS, Cho HW, Jo YD, Cho MC, Kim BD. (2006) Molecular cloning of a pepper gene that is homologous to SELF-PRUNING. Mol Cells 22: 89–96 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y, Kaya H, Goto K, Iwabuchi M, Araki T. (1999) A pair of related genes with antagonistic roles in mediating flowering signals. Science 286: 1960–1962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotoda N, Wada M. (2005) MdTFL1, a TFL1-like gene of apple, retards the transition from the vegetative to reproductive phase in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Sci 168: 95–104 [Google Scholar]

- McSteen P. (2009) Hormonal regulation of branching in grasses. Plant Physiol 149: 46–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels SD. (2009) Flowering time regulation produces much fruit. Curr Opin Plant Biol 12: 75–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimida N, Goto K, Kobayashi Y, Araki T, Ahn JH, Weigel D, Murata M, Motoyoshi F, Sakamoto W. (2001) Functional divergence of the TFL1-like gene family in Arabidopsis revealed by characterization of a novel homologue. Genes Cells 6: 327–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimida N, Kotoda N, Ueda T, Igarashi M, Hatsuyama Y, Iwanami H, Moriya S, Abe K. (2009) Four TFL1/CEN-like genes on distinct linkage groups show different expression patterns to regulate vegetative and reproductive development in apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.). Plant Cell Physiol 50: 394–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muszynski MG, Dam T, Li B, Shirbroun DM, Hou Z, Bruggemann E, Archibald R, Ananiev EV, Danilevskaya ON. (2006) delayed flowering1 encodes a basic leucine zipper protein that mediates floral inductive signals at the shoot apex in maize. Plant Physiol 142: 1523–1536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa M, Shimamoto K, Kyozuka J. (2002) Overexpression of RCN1 and RCN2, rice TERMINAL FLOWER 1/CENTRORADIALIS homologs, confers delay of phase transition and altered panicle morphology in rice. Plant J 29: 743–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillitteri LJ, Lovatt CJ, Walling LL. (2004) Isolation and characterization of a TERMINAL FLOWER homolog and its correlation with juvenility in citrus. Plant Physiol 135: 1540–1551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pnueli L, Carmel-Goren L, Hareven D, Gutfinger T, Alvarez J, Ganal M, Zamir D, Lifschitz E. (1998) The SELF-PRUNING gene of tomato regulates vegetative to reproductive switching of sympodial meristems and is the ortholog of CEN and TFL1. Development 125: 1979–1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusinkiewicz P, Erasmus Y, Lane B, Harder LD, Coen E. (2007) Evolution and development of inflorescence architectures. Science 316: 1452–1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe OJ, Amaya I, Vincent CA, Rothstein S, Carpenter R, Coen ES, Bradley DJ. (1998) A common mechanism controls the life cycle and architecture of plants. Development 125: 1609–1615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie SW, Hanway JJ, Benson GO. (1997) How a Corn Plant Develops: Special Report No. 48. Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa [Google Scholar]

- Shannon S, Meeks-Wagner DR. (1991) A mutation in the Arabidopsis TFL1 gene affects inflorescence meristem development. Plant Cell 3: 877–892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn EJ, Rojas-Pierce M, Pan S, Carter C, Serrano-Mislata A, Madueno F, Rojo E, Surpin M, Raikhel NV. (2007) The shoot meristem identity gene TFL1 is involved in flower development and trafficking to the protein storage vacuole. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 18801–18806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreekantan L, Clemens J, McKenzie MJ, Lenton JR, Croker SJ, Jameson PE. (2004) Flowering genes in Metrosideros fit a broad herbaceous model encompassing Arabidopsis and Antirrhinum. Physiol Plant 121: 163–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser B, Alvarez MJ, Califano A, Cerdan PD. (2009) A complementary role for ELF3 and TFL1 in the regulation of flowering time by ambient temperature. Plant J 58: 629–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turck F, Fornara F, Coupland G. (2008) Regulation and identity of florigen: FLOWERING LOCUS T moves center stage. Annu Rev Plant Biol 59: 573–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger E, Betz S, Xu R, Cigan AM. (2001) Selection and orientation of adjacent genes influences DAM-mediated male sterility in transformed maize. Transgenic Res 10: 409–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung K, Janosch P, McFerran B, Rose DW, Mischak H, Sedivy JM, Kolch W. (2000) Mechanism of suppression of the Raf/MEK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway by the raf kinase inhibitor protein. Mol Cell Biol 20: 3079–3085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung K, Seitz T, Li S, Janosch P, McFerran B, Kaiser C, Fee F, Katsanakis KD, Rose DW, Mischak H.et al (1999) Suppression of Raf-1 kinase activity and MAP kinase signalling by RKIP. Nature 401: 173–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeevaart JA. (2008) Leaf-produced floral signals. Curr Opin Plant Biol 11: 541–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Hu W, Wang L, Lin C, Cong B, Sun C, Luo D. (2005) TFL1/CEN-like genes control intercalary meristem activity and phase transition in rice. Plant Sci 168: 1393–1408 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.