Abstract

This study evaluated a biodegradable drug delivery system for local cancer radiotherapy consisting of a thermally sensitive elastin-like polypeptide (ELP) conjugated to a therapeutic radionuclide. Two ELPs (49 kD) were synthesized using genetic engineering to test the hypothesis that injectable biopolymeric depots can retain radionuclides locally and reduce the growth of tumors. A thermally sensitive polypeptide, ELP1, was designed to spontaneously undergo a soluble-insoluble phase transition (forming viscous microparticles) between room temperature and body temperature upon intratumoral injection, while ELP2 was designed to remain soluble upon injection and to serve as a negative control for the effect of aggregate assembly. After intratumoral administration of radionuclide conjugates of ELPs into implanted tumor xenografts in nude mice, their retention within the tumor, spatio-temporal distribution, and therapeutic effect were quantified. The residence time of the radionuclide-ELP1 in the tumor was significantly longer than the thermally insensitive ELP2 conjugate. In addition, the thermal transition of ELP1 significantly protected the conjugated radionuclide from dehalogenation, whereas the conjugated radionuclide on ELP2 was quickly eliminated from the tumor and cleaved from the biopolymer. These attributes of the thermally sensitive ELP1 depot improved the antitumor efficacy of iodine-131 compared to the soluble ELP2 control. This novel injectable and biodegradable depot has the potential to control advanced-stage cancers by reducing the bulk of inoperable tumors, enabling surgical removal of de-bulked tumors, and preserving healthy tissues.

Keywords: Local drug delivery, thermally responsive, elastin-like polypeptide, radionuclide conjugate, tumor retention, radiotherapy

Introduction

Although the first treatment option for solid tumors remains surgical resection, many patients are ineligible. To promote tumor accessibility and organ preservation during surgery better approaches are required for surgical downstaging of cancer. Relevant therapeutic approaches include adjuvant chemo-, hormone-, radio- (including external beam and internal brachytherapy), and immunotherapy. Adjuvant therapeutics are usually introduced into patients by systemic administration; however, their clinical application is frequently hampered by severe toxicity in healthy tissues.

Intratumoral (i.t.) drug delivery is an alternative to systemic drug delivery for therapy of solid tumors because it circumvents the problems inherent in systemic drug delivery –low tumor penetration, rapid drug clearance and exposure to healthy tissues– potentially retaining an anti-cancer therapeutic within the tumor for an extended period of time. This route of administration achieves a high therapeutic concentration at the desired site of action and avoids the need for systemic exposure and associated adverse effects [1–3]. Brachytherapy–the direct implantation of radioactive depots is one methodology for i.t. administration of radiopharmaceuticals and enables delivery of the maximum amount of radioactivity to the tumor [4–6] with sharp dose fall-off to surrounding normal structures, thus limiting side effects. Brachytherapy has several disadvantages. Implantation requires general anesthesia and complicated placement procedures; furthermore, these seeds may require removal and can potentially result in pulmonary migration [7–11].

To overcome these limitations, we are exploring the use of macromolecules as carriers of antitumor agents for i.t. administration. Several related strategies have shown antitumor efficacy and decreased systemic toxicity [12–15]. I.t. treatment has also become a common method for viral gene delivery in clinical trials. However, only a handful of these trials have demonstrated even a limited therapeutic effect, partially due to the lack of efficient, specific, and safe delivery vectors. Moreover, there are several obstacles to the successful implementation of i.t. administration of antitumor agents using injectable polymer depots: (1) macromolecules and nanoparticles can not effectively distribute across the tumor by diffusion, which limits interstitial penetration [16]; (2) rapid clearance of soluble polymers and drugs from the tumor interstitium [17]; (3) dose-limiting normal-tissue toxicity arising from proximal drug diffusion outside the region of interest; and (4) distal normal-tissue toxicity caused by systemic re-absorption [18–21].

This approach has been explored using synthetic co-polymers, such as poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) [22–24], PCL-PEG-PCL and PLGA-PEG-PLGA [25]; furthermore, ELP biomaterials have potential advantages over these synthetic polymeric carriers. Genetically engineered ELPs: (1) undergo coacervation and form a viscoelastic gel at a 300-fold lower concentration (.08% w/w) than other thermosensitive synthetic polymers, including poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-based polymer (2.5% w/w) or PLGA-PEG-PLGA (25% w/w). This is important in that loading of the ELP depot in the tumor environment can be kept low, while providing the requisite mechanical properties for sustained release. (2) ELPs are composed of natural amino acids that degrade into biocompatible monomers, unlike many hydrogel-forming synthetic polymers, whose degradation products have greater toxicity (e.g., acrylamides). (3) ELPs can be produced from bacterial culture with high yield and low cost in a laboratory setting (>100 mgs/L culture media). (4) ELPs are easily purified without chromatography using a batch purification process –inverse transition cycling– that only requires water, salt, and heat and laboratory centrifuges. This eliminates the requirement for, and removal of, organic solvents and harmful chemicals during synthesis and purification. It also reduces the need for complex and time-consuming chromatography protocols, further reducing the production cost compared to other peptide-based systems. (5) Genetically encoded synthesis of ELPs permits precise control over both the monomer sequence and molecular weight (MW). Unlike synthetic polymers, which frequently have some degree of polydispersity, the ELP monodispersity permits tight control tumor diffusion and clearance, which are important determinants of local drug delivery. (6) Using biomolecular engineering, optimization of peptide architecture is trivial, which permits exact placement of peptide ligands, and unique reactive sites (e.g, Lys or Cys) along the polymer chain for conjugation for therapeutics.

We hypothesized that injectable polymer-radionuclide conjugates that form a local depot upon in vivo injection can sustain “inside-out” radioactive exposure for local therapy of solid tumors. Elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs) display a thermally-triggered soluble-insoluble phase transition known as coacervation, which occurs above an inverse phase transition temperature (Tt). ELPs are artificial polypeptides based on a pentameric repeat unit bio-inspired by human tropoelastin, Val-Pro-Gly-Xaa-Gly (VPGXG), where Xaa is any amino acid except proline. As biomaterials, genetically engineered ELPs are attractive because their Tt can be precisely tuned between 0–100 °C simply by adjusting their composition, Xaa, or molecular weight (MW) [26, 27].

We designed an ELP with a sub-physiological Tt of ~28 °C to enable formation of a viscous ELP-rich coacervate at the physiological temperature of 37 °C upon i.t. injection. Investigation of i.t. retention and tissue biodistribution of the ELP and its radioiodine conjugates revealed that ELPs that transition at body temperature: (1) retain a significant fraction of the injected dose in the tumor for more than a week, (2) have low systemic toxicity even at high radionuclide doses, (3) delay tumor growth, and (4) improve survival in mice with implanted tumors when compared to a soluble ELP radio-conjugate.

Materials and Methods

ELP design and synthesis

The Tt of the ELPs were controlled at the polypeptide sequence level by specifying the fraction and identity of the fourth, guest residue (X) in the pentapeptide repeat [28]. Two types of ELPs were used for i.t. drug delivery; thermally-sensitive ELP (ELP1) was designed to have a target Tt of 28 °C by incorporation of Val at all guest residue positions and MW = 49.9 kDa. As a control a thermally-insensitive control (ELP2) was designed with a MW = 49.0 kDa, with Tt > 60 °C to ensure solubility at body temperature. The control ELP2 had guest residues Val:Gly:Ala in the ratio of 1:7:8. Synthetic genes encoding ELP1 and ELP2 were inserted into pET-25b (+) expression vectors and transformed into BLR(DE3) E. coli (Novagen, Madison, WI). One liter TB-Dry media (Mo Bio, West Carlsbad, CA) in 5-liter flask, supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin, were then inoculated with transformed cells and incubated for 24 hr at 37 °C and 250 rpm. ELP was purified using Inverse Transition Cycling (ITC), a non-chromatographic method exploiting ELP’s thermal transition to sequentially remove soluble and insoluble impurities through centrifugation and recover high yield of ELP with endotoxin levels that are below the FDA required limit of 5 EU/dose (1 dose = 1 mg) for biologics [29]. This method has been extensively described [30, 31]. In the absence of induction, expression yields between 50 and 150 mg/L were observed, which result from low-level, constitutive expression from the T7 promoter [32].

Synthesis of [14C]ELPs

ELPs were homogeneously labeled with 14C by inducing ELP expression from E. coli in M9 medium spiked with 264 mCi/mmol [U-14C]-D-glucose (Moravek Biochemicals, Brea, CA) and unlabeled glucose as the sole carbon source as previously described [33, 34]. Briefly, BLR(DE3) E. coli harboring a gene encoding either ELP1 or ELP2 in a modified pET-25b(+) expression plasmid were grown in 125 ml M9 medium at 37 °C and 250 rpm. When the OD600 of the E. coli culture reached 2.0 approximately 5 h after inoculation, protein expression was induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside. ELP was purified using ITC [31, 35]. Typically, five rounds of ITC were sufficient to purify the ELP. The specific radioactivity of [14C]ELP was 0.2 μCi/mg.

Radioiodination of ELP

The ELPs with carboxyl-terminal tyrosine residues was labeled with either 125I or 131I (PerkinElmer, Boston, MA) by the IODO-Gen (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) method [36]. Briefly, iodine was conjugated to ELPs with carboxyl-terminal tyrosine residues. A 100 μL of ELP at appropriate concentration in PBS was added to the IODO-Gen Pre-coated tube containing 2 mCi 125INa or 20 mCi 131INa for tumor retention or radiotherapy study, respectively, and purified by size-exclusion chromatography with a PD-10 column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). The radioactivity was counted on a γ-counter (LKB-Wallac, Turku, Finland). The concentration of iodinated ELP was measured by UV-Vis spectrophotometry (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) at a wavelength of 280 nm. The final concentration and radioactivity of iodinated ELP were adjusted by mixing with unlabeled ELP for an injection concentration (5 μCi/20μL of 250 μM ELP) and specific radioactivity (12 μCi/mg) for both in vitro stability and in vivo tumor retention studies; the injection concentration of [131I]ELPs were 500 ~1500 μCi/20μL of 250 μM ELP with specific radioactivity of 2000 ~ 60000 μCi/mg.

Attachment of fluorescent labels to ELP

ELPs with carboxyl-terminal cysteine residues were reacted with a ~5-fold molar excess of the maleimide derivative of Alexa Fluor 488 (AF488, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CO). AF488 was chosen due to minimal influence on the phase transition behavior of ELPs [37]. A 150 μM ELP solution in phosphate buffer (pH = 7.0) was incubated for 1 hr at room temperature with a 5-fold molar excess AF488 dissolved in DMSO (10 mg/ml). ELP-fluorophore conjugate was then separated from unreacted fluorophore by ITC and further purified via size-exclusion chromatography on a PD-10 column to ensure removal of free fluorophore. This reaction typically resulted in a labeling ratio of ~0.8 (fluorophore/ELP). Purified conjugate was then concentrated by ITC and stored at −20 °C in PBS at a concentration of ~500 μM until further use.

Thermal characterization

ELP thermal properties were characterized by monitoring the optical density (OD) of an ELP solution at 350 nm as a function of temperature (1 °C/min) on a temperature-controlled UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Cary 300 Bio; Varian instruments, Palo Alto, CA). The temperature at which the maximum of first derivative of the turbidity profile occurs is defined as the Tt.

Retention of radioiodine on radioiodinated ELP conjugates in vitro

The in vitro stability of the 125I label in [125I]ELP1 or [125I]ELP2 in PBS and plasma was determined by incubating 5 μL of 250 μM ELP of each conjugate with 15 μL of PBS or fresh mouse serum at 37 °C. Samples were collected from this mixture at 0, 2, 4, 8, 24, 48, 72, and 168 hr and immediately stored at −20 °C. Radiolabel stability in the conjugate was quantified by precipitating large ELP fragments (> 10 kDa) with 100 μL 16.5% cold trichloroacetic acid [38]. Low MW degradation products (< 10 kDa) in the supernatant and larger ELP species in the pellet were measured on a γ-counter and the loss of label was obtained by dividing the supernatant radioactivity by the total radioactivity in the supernatant and pellet at each time point.

Cell Culture

Both FaDu and 4T1 cells were cultured as a monolayer in tissue culture flasks. The FaDu culture medium contained minimal essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The 4T1 culture medium contained RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM HEPES, 4.5 g/L glucose, 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, and antibiotic-antimycotic solution. The cultures were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Animal and implantation of tumor subcutaneous xenografts

Female nude mice (Balb/C nu/nu) with an average body weight of about 20 g were purchased from NCI (Frederick, Maryland) for both tumor retention and regression experiments. They were housed in isolated caging with sterile rodent food, acidified water ad libitum, and a 12 hr light/dark cycle. Tumor leg xenografts were established from FaDu and 4T1 tumor cell lines. The right lower leg of each mouse was implanted s.c. with 1 × 106 cells in 30 μL of PBS. Tumors were allowed to grow to 150 ± 20 mm3 before starting treatment. Mice were monitored for general well-being, weight, and tumor volume. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Tumor retention of ELPs

Tumor retention of ELP1 and ELP2 following i.t. infusion was compared in nude mice bearing FaDu tumor xenografts for [14C]ELP and 4T1 for [125I]ELP. The use of two types of tumors provides greater confidence in the generality of this local radionuclide delivery approach with an injectable polymer. Twenty μL of ELPs were infused into tumors using a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, MA) at a rate of 4 μL/min. For radioactivity measurements, animals were sacrificed. The tumors were collected and analyzed using a β-counter for [14C]ELP or γ-counter for [125I]ELP at 0 and 24 h in the ELP2 group and 0, 24, 48, 72, and 168 hr in the ELP1 group. For scintillation counting, following a standard procedure from Amersham Sciences, the tumor tissue was completely dissolved in a solubilizer (Amersham Sciences, Piscataway, NJ) after 2 h incubation at 55 °C, and then 30 μL glacial acetic acid per ml of the solubilizer was added before counting on a beta counter. In a preliminary experiment, we measured a range of 86–100% recovery rate of 14C from a mixture of 14C-ELP and solublized organs. In order to evaluate the accumulation of ELPs in each organ, the count per minute of each organ was normalized by the recovered tissue mass. For fluorescence imaging, ELP1-AF488 and ELP2-AF488 were infused into FaDu tumors. At 0 and 24 hr in the ELP2 group and 0, 24, 48, 72, and 168 hr in the ELP1 group following injection, mice were given i.v. injection of Hoechst dye and sacrificed. Tumors were excised, immediately fixed by freezing in N2 (l), and cut into 20 μm thick slices. Images were obtained at 4x magnification using a TE-2000U epifluorescence microscope (Nikon Inc., Melville, NY).

Pharmacokinetic analysis of [125I]ELPs

Both [125I]ELP1 and [125I]ELP2 were infused into 4T1 tumors using the same conditions as the ELP retention study. The tumors were collected and γ-counted at 0, 4 and 24 hr following injection in the ELP2 group and 0, 24, 48, 72, and 168 hr following injection in the ELP1 group. The radioactivity level of [125I]ELP in the tumor was quantified as the % ID/tumor for each mouse at different time points. The [125I]ELP tumor retention time-course was analyzed with a one-compartment pharmacokinetic model to approximate both tumor retention and elimination of the ELP. The pharmacokinetic analysis was performed by fitting the experimental data to a pharmacokinetic model using SAAMII software (University of Washington, Seattle, WA).

Dose-dependent response of 4T1 tumors to [131I]ELP

Groups of 6 mice with s.c. 4T1 tumors were infused with 20 μL of 250 μM [131I]ELP for a total dose of 0, 500, 1000 and 1500 μCi. The mice were monitored for tumor volume, body weight (BW) and survival daily for the first week. After the first week, tumor volume and BW were monitored every 48 hours, and survival was monitored on a daily basis. Tumor volume was determined with the equation: volume = (width)2 × length × π/6. Tumor measurements were taken by one individual blinded to the treatment groups.

Effect of [131I]ELPs on 4T1 tumor xenograft

Groups of 9 mice with s.c. 4T1 tumors were infused with the following experimental groups: (1) [131I]ELP1 (20 μL, 250 μM, 1500 μCi/dose); (2) [131I]ELP2 (20 μL, 250 μM, 1500 μCi/dose); (3) saline control (20 μL,). Tumor growth, BW, and mouse survival were monitored in the same manner as the dose-dependence experiment. In the final two experiments, all the animals were monitored until the tumor size reached 5-times the initial tumor volume or 60 days post-treatment, at which point they were euthanized.

Statistical methods

Tumor retention data of [14C]ELP1 and [14C]ELP2 and [125I]ELP1 and [125I]ELP2 were compared by Student t testing. In vitro deiodination of iodine-ELPs conjugate, and tumor growth data of [131I]ELP1 and [131I]ELP2 was analyzed with one-factor ANOVA based on treatment group followed by Bonferroni t-test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in both cases. Statistical difference between survival rates of the animals was determined by Kaplan-Meier analysis.

Results

Thermal characterization of ELPs

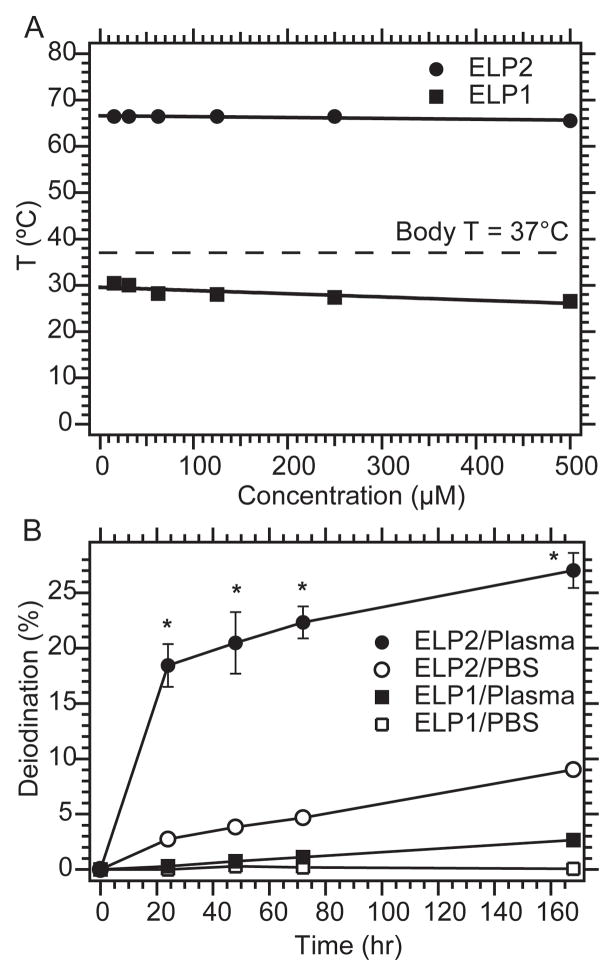

To promote i.t. retention, ELP1 was designed to form an insoluble coacervate in the tumor upon i.t. administration. Based on our previous studies, we expected the Tt of ELP1 to be > 25 °C (room temperature) and < 31.7 °C, the s.c. tumor temperature in anesthetized mice. Figure 1A shows that the Tt of ELP1 was 27 °C at a concentration of 500 μM in PBS. This Tt is relatively concentration-independent as a 30× dilution (from 500 to 15 μM) resulted in an increase of only ~3 °C. This data suggests that the ELP1 will remain in coacervate form until its concentration drops to the nanomolar range due to degradation and clearance. In contrast, ELP2 was designed to have a Tt that is much greater than the s.c temperature, so that it remains soluble upon intratumoral injection, and hence serves as a negative control for the effect of coacervation. This was achieved by the replacement of valine (Val) guest residues (Xaa) with a mixture of predominantly alanine (Ala) and glycine (Gly) in the pentameric repeat sequence of ELP2. The Tt of ELP2 was 62.5 °C at 500 μM in PBS (Fig. 1A), indicating that ELP2 should not form a coacervate following injection or at any time thereafter as dilution would simply increase Tt. These two ELPs were subsequently used to investigate the hypothesis that the thermally triggered coacervation of the ELP can result in the formation of an in situ radionuclide depot after i.t. injection.

Figure 1. In vitro thermal behavior and degradation of ELPs.

A, ELP1 has a Tt below body temperature over a large range of concentrations. ELP2 has a high Tt and over the identical concentration range, and is not expected to transition at body temperature. B, The percentage of iodine released was determined over a period of one week at 37 °C. In both PBS and mouse plasma, the ELP1 (insoluble) conjugates released only a small fraction of the iodine compared to that liberated from ELP2 (soluble) conjugates. The data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4–5). * indicates significant difference (p < 0.01)

ELP aggregation prevents the dehalogenation of iodinated peptides

The iodine in the [125I]ELP1 conjugate exhibited high retention of radioiodine in vitro after incubation in fresh mouse plasma at 37 °C for up to one week with a maximum degradation of < 3 %. In contrast, loss of label from [125I]ELP2 in mouse plasma was ~30% after a one-week incubation (Fig. 1B, p < 0.01, t-test). This substantial resistance of [125I]ELP1 to dehalogenation suggests that ELP-mediated coacervation may decrease the accessibility of the conjugated iodine to enzymatic degradation processes such as dehalogenases in vivo, and thereby increase the localized exposure of the tumor to the radioiodine. Loss of the radiolabel is a major clinical obstacle to the development of peptide-based radionuclide carriers, and coacervation-mediated strategies potentially may overcome this barrier [39].

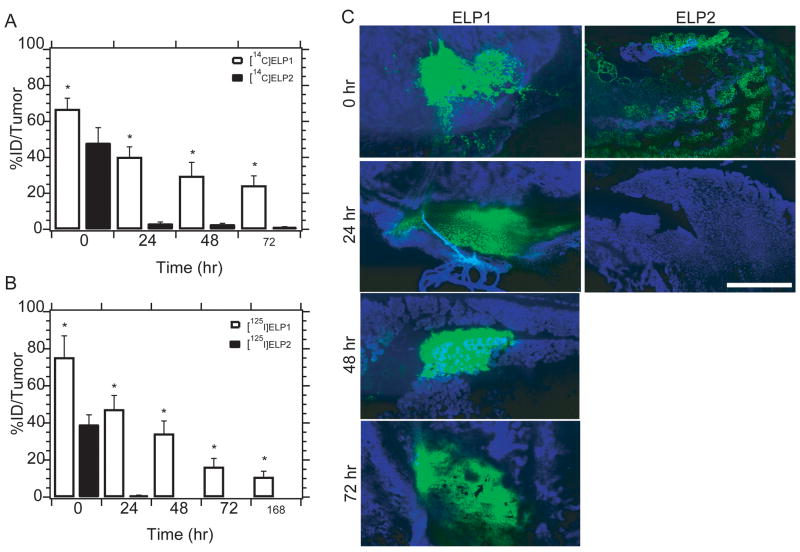

Thermally responsive ELP1 has longer tumor retention than soluble ELP2

There was a dramatic difference (p < 0.01, t-test) between the level of radioactivity in the tumors infused with the two ELPs as a function of time (Fig. 2A); ELP2 was largely lost from the tumor within 24 hr, while 30% of the injected dose of ELP1 was retained at 72 hr after infusion. These results unequivocally demonstrate that the formation of coacervate promotes retention of thermally responsive ELP infused into a tumor. Fluorescent images (Fig. 2C) demonstrate that spatial microdistribution of fluorescently labeled ELP1 within the tumor remains nearly constant over a week, suggesting the formation of a stable coacervate depot within the tumor after infusion. The fluorescence images also confirm that soluble ELP2 is rapidly cleared from the tumor, confirming the importance of coacervate in promoting retention.

Figure 2. Tumor retention of ELP and radioactive ELPs after intratumoral infusion.

A, tumor retention of ELP after intratumoral infusion of [14C]ELPs in mice bearing FaDu tumor. The ID%/tumor of 0, 24, 48 and 72 hr after administration are expressed as mean (n = 8–10); error bars, SEM; * indicates significant difference (p < 0.01; t-test); B, tumor retention of radioactivity loaded on ELPs after intratumoral infusion of [125I]ELPs in mice bearing 4T1 tumor. The ID%/tumor at 0, 24, 48, 72 hr and 1 week after administration are expressed as mean (n = 9); error bars, SEM; * indicates significant difference (p< 0.01; t-test). NOTE: Fig 2A shows retention of ELP after injection, whereas Fig 2B directly assays for radioiodine retention in the tumor. C, ELP-AF488 fluorescence imaging following intratumoral administration. Epifluorescent images of tumor sections at these time points verify the increase in tumor retention time (AF488 = green, Hoechst = blue, scale bar = 100 μm)).

Thermally sensitive ELP prolongs tumor retention of iodine-125

There was a significant difference in the level of radioactivity as a function of time in the tumor between 125I conjugates of the two ELPs (p < 0.01, t-test) which is consistent with the ~10 × longer tumor retention time of insoluble ELP1 vs. soluble ELP2 (Fig. 2B). The temporal profile of [125I]ELP follows the pattern of [14C]ELP accumulation, which suggests that the loss of radiolabel is controlled either by clearance or proteolysis of ELP, not by dehalogenation. Furthermore, measurement of radioactivity from the [125I]ELP1 conjugate suggests that the radiolabel remains attached long enough to ELP1 to provide prolonged exposure of the tumor to radiation in a therapeutic scenario.

Tumor pharmacokinetics of ELP after i.t. administration

ELP1 exhibited a higher tumor retention half-life of 44.2 compared to 8.3 for ELP2 (Table. 1). Tumor exposure as measured by the area-under-curve (AUC) parameter showed that ELP1 had a 57-fold greater tumor exposure than ELP2 (Table. 1). These data indicate that coacervation increases both tumor retention and exposure of radioiodine following i.t. administration.

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of [125I]ELP in the tumor after intratumoral administration.

| ELP | Ke (h−1) | T1/2 (hr) | AUC (hr %ID/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ELP1 | 0.016 | 44.2 | 4440.5 |

| ELP2 | 0.083 | 8.3 | 72.7 |

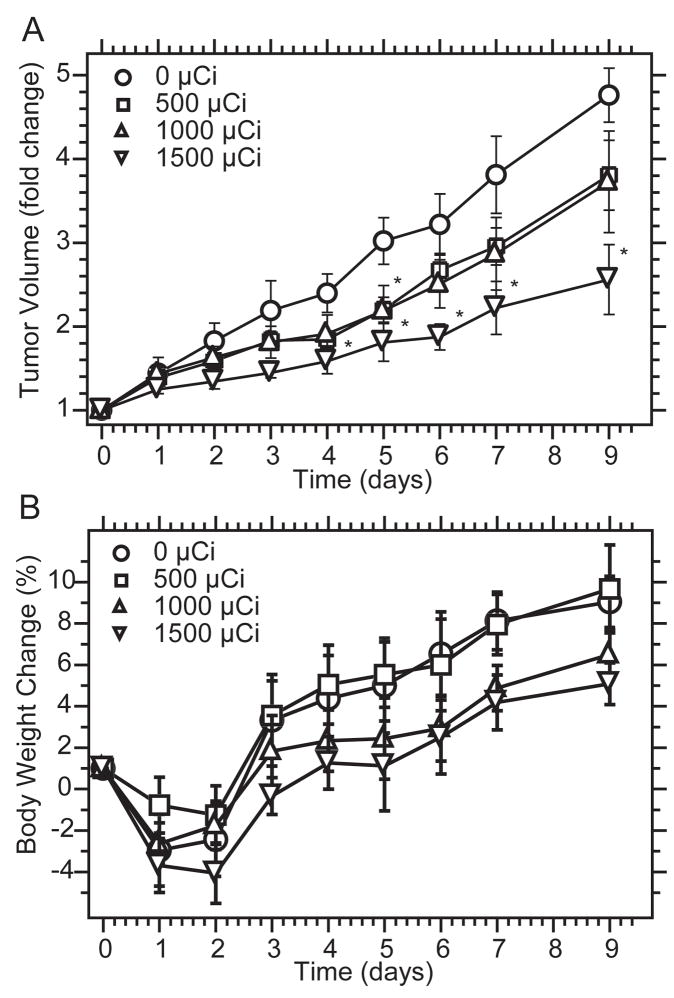

Dose-dependent response of tumors to [131I]ELP

[131I]ELP1 exhibited significant tumor inhibition at a dose of 1500 μCi from days 4–9 after i.t. administration when compared to 0 μCi/dose ELP (p < 0.05, t-test). At lower doses, only 1000 μCi showed statistically significant inhibition at day 5 compared to the control (Fig. 3A). The administered radioactivity level-dependent curves for body weight showed that no animal lost more than 5% body weight in any of the treatment groups (Fig. 3B). The minimal body weight loss indicates that intratumoral radiotherapy with ELP does not lead to significant toxicity, and that the mice may be able to tolerate higher doses. The decrease in tumor size and the minimal toxicity suggested that local delivery of [131I]ELP via coacervate formation in a tumor has the potential for initiating local tumor regression, justifying additional study.

Figure 3. Dose-dependent response of tumors to 131I -loaded ELPs.

A, Relative tumor volume (normalized to initial tumor volume) for mice infused with different doses of radioactivity, which are expressed as mean (n = 6); error bars, SEM; * indicates statistically significant difference (p < 0.05, t-test) from unlabelled ELP control. B. Mean body weights of 4T1 xenograft-bearing nude mice intratumorally injected with unlabeled ELP1 and increasing doses of [131I]ELP1. Data represent mean (n = 6); error bars, SEM.

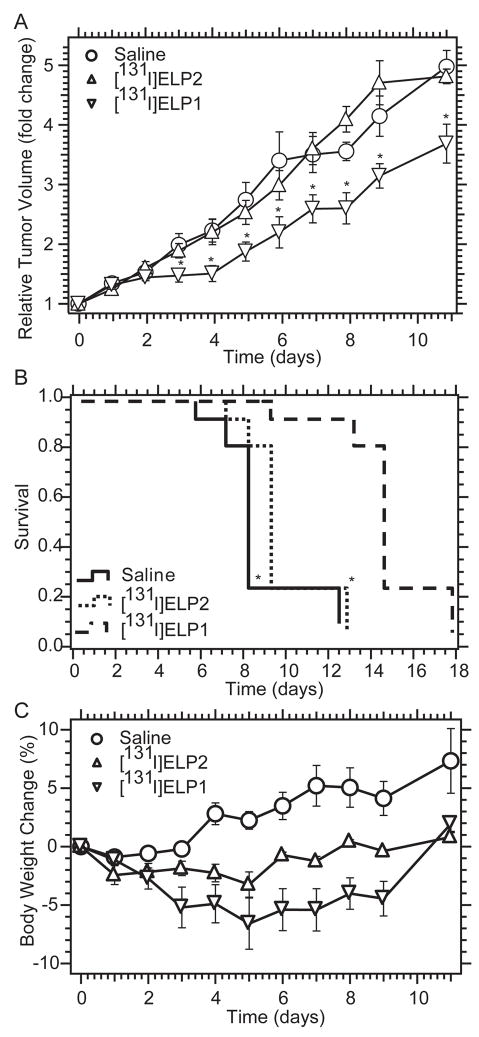

Antitumor effect of iodine 131-loaded ELPs

[131I]ELP1 exhibited significant tumor inhibition at the dose of 1500 μCi from day 3 to 11 after i.t. administration when compared with [131I]ELP2 or NaCl saline (saline, 0.9 % sodium chloride) (p < 0.05, t-test ) (Fig. 4A). [131I]ELP1 also prolonged the survival time of the mice compared with the two control groups (p < 0.01, Kaplan-Meier analysis) vs. saline or ELP2 group (Fig. 4B). Neither [131I]ELP1 or [131I]ELP2 induced greater than 7% body weight loss (Fig. 4C). These results clearly show the benefits of using an ELP that undergoes coacervation within the tumor after injection over a soluble ELP that does not form a coacervate in vivo. Clearly, retaining the radioactivity within the tumor after injection provides significant benefit for loco-regional therapy of solid tumors.

Figure 4. Antitumor efficacy of 131I -loaded ELPs.

A, Comparison of 131I -loaded ELP1 and ELP2. Data represent mean (n = 9); error bars, SEM; * indicates P < 0.05 vs. ELP2 or saline. B, The mouse survival was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by Mann-Whitney Test. * indicates P < 0.01 Vs. ELP1 C, Mean body weights of 4T1 xenograft-bearing nude mice given intratumoral injections of saline or [131I]ELP1. Data represent mean (n = 9); error bars, SEM.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to evaluate the in vitro stability of the radionuclide, the tumor retention and the antitumor efficacy of a radioactive, injectable, thermally responsive ELP that forms a viscous, gel-like coacervate phase upon intratumoral injection. We have previously shown that ELPs in combination with hyperthermia may be useful as drug carriers for the thermally targeted systemic delivery of therapeutics to solid tumors [40, 41]. This study is complementary to these previous studies in that it expands upon the range of modalities via which thermally responsive ELPs may be used for the delivery of cancer therapeutics.

Direct loco-regional drug administration is an attractive approach for drug delivery because it is the most direct form of treatment, and in principle, it can immediately lead to a high therapeutic concentration at the desired site of action, while avoiding the need for high systemic exposure and associated adverse effects. To achieve significant antitumor efficacy via i.t administration of radionuclide, the radionuclide-carrier conjugate must have the following attributes: (1) a highly efficient radionuclide with high energy, appropriate penetration range, and optimal decay half-life; (2) a highly stable radionuclide immobilization, which prevents dissemination from the injection site; (3) a minimal release rate from the tumor into bulk circulation; (4) a radionuclide carrier that is both biocompatible and biodegradable; and (5) a suitable method for convenient administration in the clinic.

Motivated by these considerations, we selected 131I as the anticancer reagent because it is both a gamma and beta emitting radionuclide with a decay half-life of 8.1 days and is the most frequently utilized radionuclide for clinical targeted radiotherapy. This half-life roughly matches the retention time (one week) of [125I]ELP in solid tumors, and is expected to decrease the systemic toxicity after due to release into the circulation. Because the mean tissue penetration distance of 131I beta emission is 910 μm it is well suited to the treatment of small tumors [42] using a single injection or larger tumors using image guided injection of multiple focal deposits.

We chose ELPs as the radioactive iodine carrier primarily dictated by the consideration that ELPs can be readily engineered to undergo a soluble to coacervate transition slightly below body temperature, so that upon intratumoral infusion a radionuclide-ELP conjugate spontaneously forms a depot within the tumor, which irradiates the tumor from the inside-out. In addition, the ELP transition temperature can be controlled changing the amino acid composition and the peptide molecular weight [43, 44]. Both of these variables can be precisely controlled by recombinant ELP biosynthesis; furthermore, it is trivial to design and purify an ELP with the desired in vivo thermal behavior.

ELPs have other useful attributes as drug delivery vehicles. First, the number(s) and location(s) of one or more orthogonally reactive functional groups can be precisely specified along the ELP chain, so that different drugs and/or imaging agents can be conjugated to the ELP. Furthermore, because ELPs can be genetically encoded [43, 45], they can be synthesized as monodisperse polymers with high yields [26] via hyperexpression from synthetic genes in E. coli, which are simple to purify using their phase transition behavior [31]. In addition to controlling the phase transition behavior of an ELP, the ability to synthesize monodisperse polypeptides at high MW is desirable for many drug delivery applications. MW is one of the primary parameters that controls the polymer pharmacokinetics within the animal and diffusion within a tumor [46]. Lastly, ELPs are slowly biodegraded into short peptides and amino acids in vivo, which provides a simple mechanism of elimination for these high MW polymers.

An important factor to successfully deliver anticancer drugs to tumors is the ability to selectively concentrate the drug in the tumor while sparing surrounding healthy tissue. Twenty four hours after administration, greater than 40% of the injected dose (ID) of the thermally sensitive ELP1 remained in the tumor while less than 1% the control, ELP2, remained in the tumor (Fig. 2B). Thermally sensitive ELP1 ([125I]ELP1) also exhibited significantly longer tumor retention (20% ID/tumor up to one week) when compared with the saline control and the thermally insensitive ELP2 group. These data suggest that ELP1 undergoes its thermal transition in the tumor immediately after i.t. administration. Similarly, pharmacokinetic analysis showed that the clearance time of radionuclide from the [125I]ELP1 conjugate that was injected into the tumor was much slower, and its AUC was much higher than the control groups (Table 1).

The similarity in the time-dependent tumor retention of 125I in the [125I]ELP1 conjugate compared to the parent ELP1 also suggested that the radionuclide remains closely associated with the ELP for prolonged periods of time, suggesting that the in vivo coacervation of ELP1 reduces the loss of the radionuclide, which provides an important ancillary benefit to the use of a thermally sensitive ELP. It is well known that the dehalogentation of iodine from peptides and proteins most frequently occurs via an enzymatic process [39], and factors that protect the iodine from these enzymes improve the stability and efficacy the radionuclide. As proteins, dehalogenases are high molecular weight molecules that are unlikely to penetrate inside ELP coacervates. Without access to the interior of the depot, these polypeptide coacervates prevent release and subsequent clearance of free iodine. Through this mechanism, the thermally sensitive ELP aggregation prevents loss of the radioisotope and improves the efficacy of the conjugate.

In i.t. radionuclide therapy, unlike chemotherapy, drug release from the ELP carrier is not necessary; furthermore, the radionuclide does not need to be internalized by tumor cells to achieve efficacy, because the radioactive emissions can kill tumor cells from a distance. For example, 131I has an effective tissue penetration distance of 910 μm, and can therefore exert a “bystander” or “crossfire” effect [47]. As the ELP retains the radionuclide through aggregation and radionuclide-conjugated peptides are released slowly, ELP radionuclide carrier depots may achieve tumor regression via two mechanisms: (1) bulk irradiation from the core killing tumor cells close to the administration site and (2) ELP proteolysis and diffusion of partially degraded peptides to tumor cells beyond the path of irradiation.

In previous studies, we have shown that thermally responsive ELPs accumulate in heated xenograft tumors (mouse leg) after systemic administration [40, 48]. For large, subcutaneous tumors heated from the surface of the skin, the tumor accumulation was uneven, with concentration in the center of the tumor much lower than at the periphery [49, 50]. Thus, cytotoxic agents acting on dividing tumor cells at the growing edge of the tumor mass may be unable to influence the cells in the center of the tumor. Alternatively in this report we describe the i.t. injection of an ELP that forms a coacervate that immobilizes the therapeutic agent within the tumor core. This approach slows tumor growth from the inside-out and may be complementary to systemic therapy.

Although significant tumor growth delay was achieved in [131I]ELP1 at 1500 μCi/dose, complete regression may require either additional radioactivity or improved distribution throughout the tumor. In future studies, we hope to maximize tumor regression by optimizing the ELP concentration and infusion volume/protocol and designing new ELPs that form more stable coacervates in vivo through incorporation of intermolecular crosslinks. Nevertheless, these results strongly suggest that local delivery of [131I]ELP via coacervate formation in a tumor has exciting potential for tumor therapy.

Conclusion

Thermally sensitive ELPs are promising materials for intratumoral drug delivery because they: (1) are injectable, which provides a convenient administration method; (2) prevent deiodination of the covalently conjugated radionuclide and localize the radionuclide to this delivery depot; (3) have a longer retention time in the tumors compared to soluble polymer, which increases the therapeutic exposure to the tumor; and (4) inhibit tumor growth and extend animal survival. Although these initial results are promising, in that they suggest that local delivery of [131I]ELP via coacervate formation in a tumor has the potential for local tumor regression, much remains to be done to optimize this system to obtain complete tumor regression. Future efforts will focus on improving the efficacy of this methodology by increasing the retention time and tumor dissemination of the ELP-radionuclide conjugate within the tumor by a number of strategies; these include the incorporation of reversible crosslinks to mechanically stabilize the coacervate and by the incorporation of embedded peptide sequences that promote binding to ubiquitous extracellular matrix proteins that are overexpressed by tumors [51, 52]. Thus, the current approach describes a biocompatible and biodegradable radionuclide-biopolymer conjugate, which may serve a useful role in brachytherapy of injection-accessible tumors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This research was supported by the NIH through grant R01 CA138784 to W. L., 5F32-CA-123889 to J.A.M., and RO1 EB000188 to A.C

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

A.C. has a financial interest in Phase Biopharmaceuticals, which has licensed the rights to the local delivery technology described herein from Duke University.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Celikoglu F, Celikoglu SI, York AM, Goldberg EP. Intratumoral administration of cisplatin through a bronchoscope followed by irradiation for treatment of inoperable non-small cell obstructive lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2006;51(2):225–236. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakase Y, Hagiwara A, Kin S, Fukuda K, Ito T, Takagi T, Fujiyama J, Sakakura C, Otsuji E, Yamagishi H. Intratumoral administration of methotrexate bound to activated carbon particles: antitumor effectiveness against human colon carcinoma xenografts and acute toxicity in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311(1):382–387. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.069450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Herpen CM, van der Laak JA, de Vries IJ, van Krieken JH, de Wilde PC, Balvers MG, Adema GJ, De Mulder PH. Intratumoral recombinant human interleukin-12 administration in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients modifies locoregional lymph node architecture and induces natural killer cell infiltration in the primary tumor. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(5):1899–1909. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li YC, Xu WY, Tan TZ, He S. 131I-recombinant human EGF has antitumor effects against MCF-7 human breast cancer xenografts with low levels of EGFR. Nucl Med Biol. 2004;31(4):435–440. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosemurgy A, Luzardo G, Cooper J, Bowers C, Zervos E, Bloomston M, Al-Saadi S, Carroll R, Chheda H, Carey L, Goldin S, Grundy S, Kudryk B, Zwiebel B, Black T, Briggs J, Chervenick P. 32P as an adjunct to standard therapy for locally advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer: a randomized trial. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(4):682–688. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0430-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vriesendorp HM, Quadri SM. Radiolabeled immunoglobulin therapy: old barriers and new opportunities. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2001;1(3):461–478. doi: 10.1586/14737140.1.3.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bensaleh S, Bezak E, Borg M. Review of MammoSite brachytherapy: advantages, disadvantages and clinical outcomes. Acta Oncol. 2009;48(4):487–494. doi: 10.1080/02841860802537916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perera F, Chisela F, Engel J, Venkatesan V. Method of localization and implantation of the lumpectomy site for high dose rate brachytherapy after conservative surgery for T1 and T2 breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31(4):959–965. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)00576-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redmond MC. Ultrasonically guided interstitial brachytherapy for prostate cancer: care of the patient in ambulatory surgery. J Perianesth Nurs. 1998;13(3):156–164. doi: 10.1016/s1089-9472(98)80045-2. quiz 164–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone NN, Stock RG. Prostate brachytherapy in patients with prostate volumes >/= 50 cm3: dosimetic analysis of implant quality. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;46(5):1199–1204. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00516-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone NN, Stock RG. Reduction of pulmonary migration of permanent interstitial sources in patients undergoing prostate brachytherapy. Urology. 2005;66(1):119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Netti PA, Hamberg LM, Babich JW, Kierstead D, Graham W, Hunter GJ, Wolf GL, Fischman A, Boucher Y, Jain RK. Enhancement of fluid filtration across tumor vessels: implication for delivery of macromolecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(6):3137–3142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saltzman WM, Fung LK. Polymeric implants for cancer chemotherapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1997;26(2–3):209–230. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bobo RH, Laske DW, Akbasak A, Morrison PF, Dedrick RL, Oldfield EH. Convection-enhanced delivery of macromolecules in the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(6):2076–2080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zentner GM, Rathi R, Shih C, McRea JC, Seo MH, Oh H, Rhee BG, Mestecky J, Moldoveanu Z, Morgan M, Weitman S. Biodegradable block copolymers for delivery of proteins and water-insoluble drugs. J Control Release. 2001;72(1–3):203–215. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00276-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu P, Wang X, Fu YX. Enhanced local delivery with reduced systemic toxicity - Delivery, delivery, and delivery. Gene Ther. 2006;13(15):1131–1132. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wenig BL, Werner JA, Castro DJ, Sridhar KS, Garewal HS, Kehrl W, Pluzanska A, Arndt O, Costantino PD, Mills GM, Dunphy FR, 2nd, Orenberg EK, Leavitt RD. The role of intratumoral therapy with cisplatin/epinephrine injectable gel in the management of advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128(8):880–885. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.8.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomita T. Interstitial chemotherapy for brain tumors: review. J Neurooncol. 1991;10(1):57–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00151247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Hu JK, Krol A, Li YP, Li CY, Yuan F. Systemic dissemination of viral vectors during intratumoral injection. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2(11):1233–1242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bier J, Benders P, Wenzel M, Bitter K. Kinetics of 57Co-bleomycin in mice after intravenous, subcutaneous and intratumoral injection. Cancer. 1979;44(4):1194–1200. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197910)44:4<1194::aid-cncr2820440405>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Begg AC, Bartelink H, Stewart FA, Brown DM, Luck EE. Improvement of differential toxicity between tumor and normal tissues using intratumoral injection with or without a slow-drug-release matrix system. NCI Monogr. 1988;(6):133–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hruby M, Konak C, Kucka J, Vetrik M, Filippov SK, Vetvicka D, Mackova H, Karlsson G, Edwards K, Rihova B, Ulbrich K. Thermoresponsive, hydrolytically degradable polymer micelles intended for radionuclide delivery. Macromol Biosci. 2009;9(10):1016–1027. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200900083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hruby M, Kucka J, Lebeda O, Mackova H, Babic M, Konak C, Studenovsky M, Sikora A, Kozempel J, Ulbrich K. New bioerodable thermoresponsive polymers for possible radiotherapeutic applications. J Control Release. 2007;119(1):25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hruby M, Subr V, Kucka J, Kozempel J, Lebeda O, Sikora A. Thermoresponsive polymers as promising new materials for local radiotherapy. Appl Radiat Isot. 2005;63(4):423–431. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2005.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bae SJ, Suh JM, Sohn YS, Bae YH, Kim SW, Jeong B. Thermogelling poly(caprolactone-b-ethylene glycol-b-caprolactone) aqueous solutions. Macromolecules. 2005;38(12):5260–5265. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chilkoti A, Dreher MR, Meyer DE. Design of thermally responsive, recombinant polypeptide carriers for targeted drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54(8):1093–1111. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chilkoti A, Dreher MR, Meyer DE, Raucher D. Targeted drug delivery by thermally responsive polymers. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54(5):613–630. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyer DE, Chilkoti A. Quantification of the effects of chain length and concentration on the thermal behavior of elastin-like polypeptides. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5(3):846–851. doi: 10.1021/bm034215n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McHale MK, Setton LA, Chilkoti A. Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of enzymatically cross-linked elastin-like polypeptide gels for cartilaginous tissue repair. Tissue Eng. 2005;11(11–12):1768–1779. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Betre H, Setton LA, Meyer DE, Chilkoti A. Characterization of a genetically engineered elastin-like polypeptide for cartilaginous tissue repair. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3(5):910–916. doi: 10.1021/bm0255037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer DE, Chilkoti A. Purification of recombinant proteins by fusion with thermally-responsive polypeptides. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17(11):1112–1115. doi: 10.1038/15100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grossman TH, Kawasaki ES, Punreddy SR, Osburne MS. Spontaneous cAMP-dependent derepression of gene expression in stationary phase plays a role in recombinant expression instability. Gene. 1998;209(1–2):95–103. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu W, Dreher RM, Furgeson DY, Peixoto VK, Yuan H, Zalutsky MR, Chilkoti A. Tumor Accumulation, Degradation and Pharmacokinetics of Elastin-Like Polypeptides in Nude Mice. J Control Release. 2006;116(2):170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu W, Dreher MR, Chow DC, Zalutsky MR, Chilkoti A. Tracking the in vivo fate of recombinant polypeptides by isotopic labeling. Journal of Controlled Release. 2006;114(2):184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyer DE, Trabbic-Carlson K, Chilkoti A. Protein purification by fusion with an environmentally responsive elastin-like polypeptide: effect of polypeptide length on the purification of thioredoxin. Biotechnol Prog. 2001;17(4):720–728. doi: 10.1021/bp010049o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Unak T, Akgun Z, Yildirim Y, Duman Y, Erenel G. Self-radioiodination of iodogen. Appl Radiat Isot. 2001;54(5):749–752. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(00)00337-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dreher MR, Raucher D, Balu N, Michael Colvin O, Ludeman SM, Chilkoti A. Evaluation of an elastin-like polypeptide-doxorubicin conjugate for cancer therapy. J Control Release. 2003;91(1–2):31–43. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00216-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith CE, Dahan S, Fazel A, Lai W, Nanci A. Correlated biochemical and radioautographic studies of protein turnover in developing rat incisor enamel following pulse-chase labeling with L-[35S]- and L-[methyl-3H]-methionine. Anat Rec. 1992;232(1):1–14. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092320102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Engler D, Burger AG. The deiodination of the iodothyronines and of their derivatives in man. Endocr Rev. 1984;5(2):151–184. doi: 10.1210/edrv-5-2-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meyer DE, Kong GA, Dewhirst MW, Zalutsky MR, Chilkoti A. Targeting a genetically engineered elastin-like polypeptide to solid tumors by local hyperthermia. Cancer Res. 2001;61(4):1548–1554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raucher D, Chilkoti A. Enhanced uptake of a thermally responsive polypeptide by tumor cells in response to its hyperthermia-mediated phase transition. Cancer Research. 2001;61(19):7163–7170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zalutsky M. Radionuclide therapy. In: RF, editor. Handbook of nuclear chemistry: radiochemistry and radiopharmaceutical chemistry in life sciences. Vol. 4. Kluwer Academic; Dordrecht, Netherlands: 2003. pp. 315–348. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meyer DE, Chilkoti A. Genetically encoded synthesis of protein-based polymers with precisely specified molecular weight and sequence by recursive directional ligation: examples from the elastin-like polypeptide system. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3(2):357–367. doi: 10.1021/bm015630n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Urry DW. Free energy transduction in polypeptides and proteins based on inverse temperature transitions. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1992;57(1):23–57. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(92)90003-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meyer DE, Chilkoti A. Quantification of the effects of chain length and concentration on the thermal behavior of elastin-like polypeptides. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5(3):846–851. doi: 10.1021/bm034215n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dreher MR, Liu W, Michelich CR, Dewhirst MW, Yuan F, Chilkoti A. Tumor vascular permeability, accumulation, and penetration of macromolecular drug carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(5):335–344. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharkey RM, Goldenberg DM. Targeted therapy of cancer: new prospects for antibodies and immunoconjugates. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56(4):226–243. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.4.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meyer DE, Shin BC, Kong GA, Dewhirst MW, Chilkoti A. Drug targeting using thermally responsive polymers and local hyperthermia. J Control Release. 2001;74(1–3):213–224. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00319-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dreher MR, Liu W, Michelich CR, Dewhirst MW, Chilkoti A. Thermal cycling enhances the accumulation of a temperature-sensitive biopolymer in solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67(9):4418–4424. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Z, Ballinger JR, Rauth AM, Bendayan R, Wu XY. Delivery of an anticancer drug and a chemosensitizer to murine breast sarcoma by intratumoral injection of sulfopropyl dextran microspheres. The Journal of pharmacy and pharmacology. 2003;55(8):1063–1073. doi: 10.1211/0022357021567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahmed F, Steele JC, Herbert JM, Steven NM, Bicknell R. Tumor stroma as a target in cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2008;8(6):447–453. doi: 10.2174/156800908785699360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chometon G, Jendrossek V. Targeting the tumour stroma to increase efficacy of chemo- and radiotherapy. Clin Transl Oncol. 2009;11(2):75–81. doi: 10.1007/s12094-009-0317-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.