Abstract

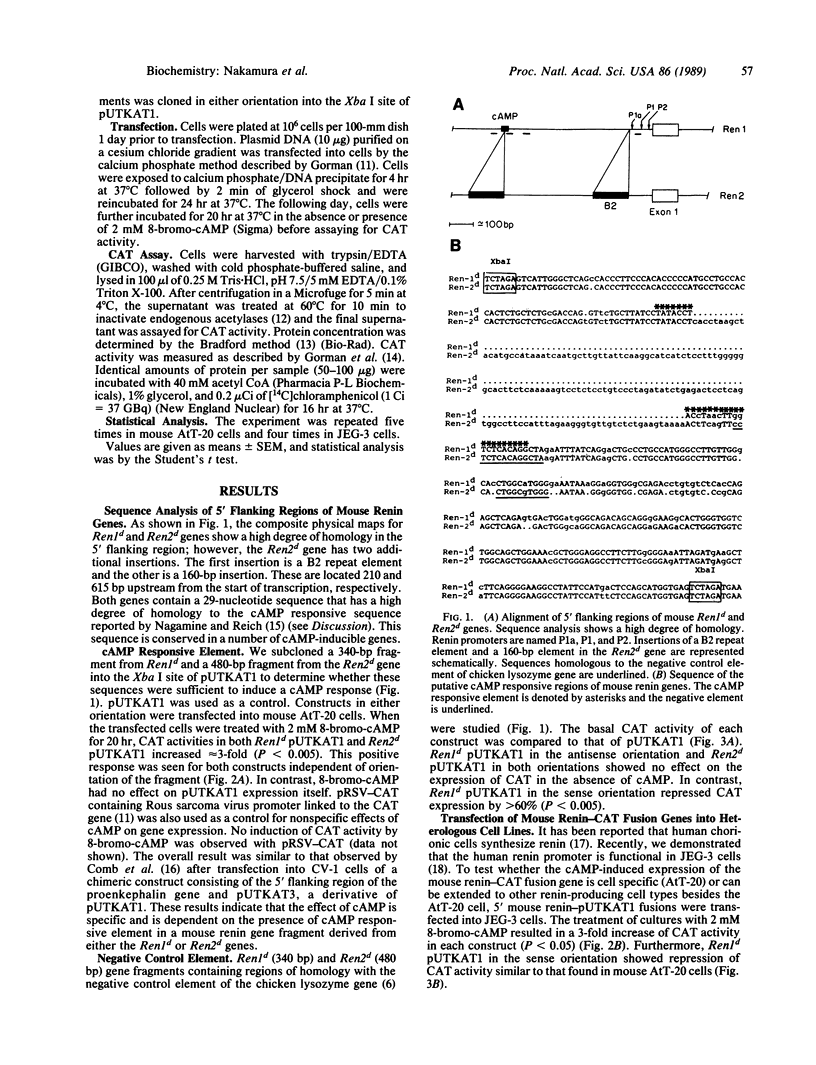

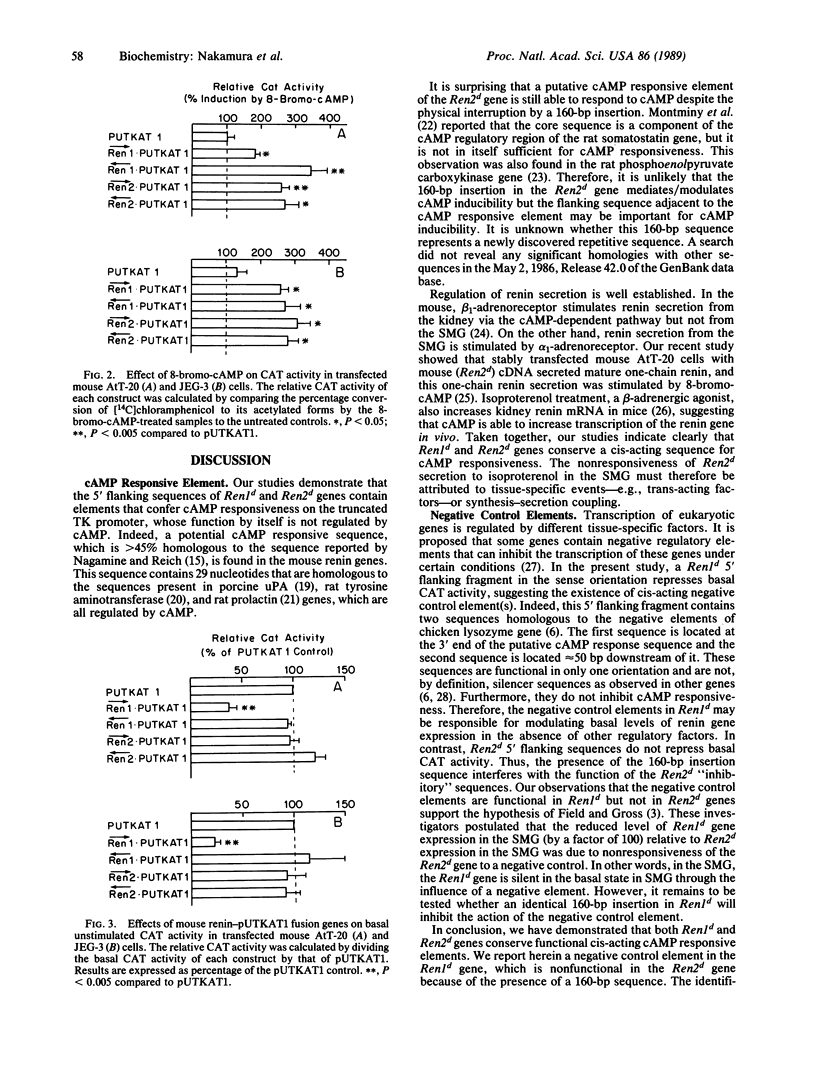

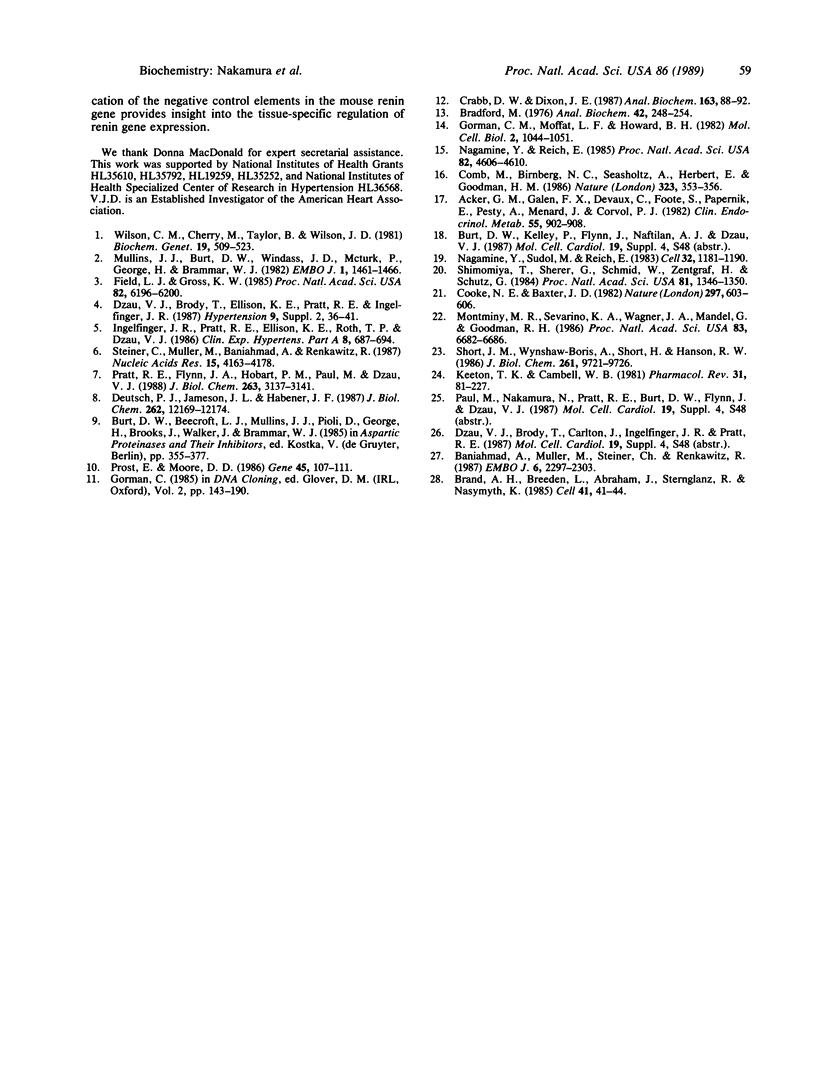

The 5' flanking regions of the mouse renin genes (Ren1d and Ren2d) contain putative negative control and cAMP responsive elements. Sequence analysis shows additionally that these putative control elements in the Ren2d gene are interrupted by a 160-base-pair insertion. To document the functions of these elements, we isolated these regions and fused them to the reporter gene chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT), which was linked upstream to a thymidine kinase (TK) promoter (pUTKAT1). The chimeric constructs were transfected into mouse pituitary tumor AtT-20 and human choriocarcinoma JEG-3 cells. At the basal unstimulated condition, Ren1d 5' flanking sequence in the sense orientation inhibited basal CAT expression from the TK promoter of pUTKAT1, whereas the same sequence in the antisense orientation did not. The 5' flanking region of Ren2d had no inhibitory effect on basal CAT expression. These data demonstrate that the negative control element is functional in Ren1d but is nonfunctional in Ren2d, suggesting that the 160-base-pair insertion in Ren2d interferes with the function of the negative control elements. In response to 8-bromo-cAMP, both renin genes increased transcription 3-fold, suggesting a functional cis action of the cAMP responsive element in both genes. These data may be important in the understanding of the regulation of the tissue-specific expression of mouse renin genes.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Acker G. M., Galen F. X., Devaux C., Foote S., Papernik E., Pesty A., Menard J., Corvol P. Human chorionic cells in primary culture: a model for renin biosynthesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1982 Nov;55(5):902–909. doi: 10.1210/jcem-55-5-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baniahmad A., Muller M., Steiner C., Renkawitz R. Activity of two different silencer elements of the chicken lysozyme gene can be compensated by enhancer elements. EMBO J. 1987 Aug;6(8):2297–2303. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02504.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976 May 7;72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand A. H., Breeden L., Abraham J., Sternglanz R., Nasmyth K. Characterization of a "silencer" in yeast: a DNA sequence with properties opposite to those of a transcriptional enhancer. Cell. 1985 May;41(1):41–48. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comb M., Birnberg N. C., Seasholtz A., Herbert E., Goodman H. M. A cyclic AMP- and phorbol ester-inducible DNA element. 1986 Sep 25-Oct 1Nature. 323(6086):353–356. doi: 10.1038/323353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke N. E., Baxter J. D. Structural analysis of the prolactin gene suggests a separate origin for its 5' end. Nature. 1982 Jun 17;297(5867):603–606. doi: 10.1038/297603a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabb D. W., Dixon J. E. A method for increasing the sensitivity of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase assays in extracts of transfected cultured cells. Anal Biochem. 1987 May 15;163(1):88–92. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch P. J., Jameson J. L., Habener J. F. Cyclic AMP responsiveness of human gonadotropin-alpha gene transcription is directed by a repeated 18-base pair enhancer. Alpha-promoter receptivity to the enhancer confers cell-preferential expression. J Biol Chem. 1987 Sep 5;262(25):12169–12174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field L. J., Gross K. W. Ren-1 and Ren-2 loci are expressed in mouse kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Sep;82(18):6196–6200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.18.6196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman C. M., Moffat L. F., Howard B. H. Recombinant genomes which express chloramphenicol acetyltransferase in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1982 Sep;2(9):1044–1051. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.9.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingelfinger J. R., Pratt R. E., Ellison K. E., Roth T. P., Dzau V. J. Multiple sites of regulation of mouse renin expression in ontogeny. Clin Exp Hypertens A. 1986;8(4-5):687–694. doi: 10.3109/10641968609046586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montminy M. R., Sevarino K. A., Wagner J. A., Mandel G., Goodman R. H. Identification of a cyclic-AMP-responsive element within the rat somatostatin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Sep;83(18):6682–6686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.18.6682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins J. J., Burt D. W., Windass J. D., McTurk P., George H., Brammar W. J. Molecular cloning of two distinct renin genes from the DBA/2 mouse. EMBO J. 1982;1(11):1461–1466. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01338.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagamine Y., Reich E. Gene expression and cAMP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Jul;82(14):4606–4610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.14.4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagamine Y., Sudol M., Reich E. Hormonal regulation of plasminogen activator mRNA production in porcine kidney cells. Cell. 1983 Apr;32(4):1181–1190. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90301-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt R. E., Flynn J. A., Hobart P. M., Paul M., Dzau V. J. Different secretory pathways of renin from mouse cells transfected with the human renin gene. J Biol Chem. 1988 Mar 5;263(7):3137–3141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prost E., Moore D. D. CAT vectors for analysis of eukaryotic promoters and enhancers. Gene. 1986;45(1):107–111. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinomiya T., Scherer G., Schmid W., Zentgraf H., Schütz G. Isolation and characterization of the rat tyrosine aminotransferase gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Mar;81(5):1346–1350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short J. M., Wynshaw-Boris A., Short H. P., Hanson R. W. Characterization of the phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (GTP) promoter-regulatory region. II. Identification of cAMP and glucocorticoid regulatory domains. J Biol Chem. 1986 Jul 25;261(21):9721–9726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner C., Muller M., Baniahmad A., Renkawitz R. Lysozyme gene activity in chicken macrophages is controlled by positive and negative regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987 May 26;15(10):4163–4178. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.10.4163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C. M., Cherry M., Taylor B. A., Wilson J. D. Genetic and endocrine control of renin activity in the submaxillary gland of the mouse. Biochem Genet. 1981 Jun;19(5-6):509–523. doi: 10.1007/BF00484623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]