Abstract

Study Objectives:

To examine factors associated with self-reported sleep quality and duration among very old adults in China.

Design:

Cross-sectional analysis of the 2005 wave of the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS).

Setting:

In-home interview with older adults in 22 provinces in mainland China.

Participants:

A total of 15,638 individuals aged 65 and older (5,047 aged 65-79, 3,870 aged 80-89, 3,927 aged 90-99, and 2,794 aged 100 and older, including 6,688 men and 8,950 women).

Interventions:

N/A

Measurements and Results:

Two self-reported sleep questions together with numerous sociodemographic and health status measures were used in this study. Sixty-five per cent of Chinese elders reported good quality of sleep. The average number of self-reported hours of sleep was 7.5 (SD 1.9), with 13.1%, 16.2%, 18.0%, 28.0%, 9.2%, and 15.5% reporting ≤ 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and ≥ 10 hours, respectively (weighted). Multivariate analyses showed that male gender, rural residence, Han ethnicity, higher socioeconomic status, and good health conditions were positively associated with good quality of sleep. All other factors being equal, octogenarians, nonagenarians, and centenarians were more likely to have good sleep quality than the young elders aged 65-79. Elders with poorer health status or older age were more likely to have either relatively shorter (≤ 6 h) or longer (≥ 10 h) sleep duration. Married elders were more likely to have an average duration between these two values. Except for some geographic variations, associations between all other factors and sleep duration were weak compared to the effects of health.

Conclusions:

Age and health conditions are the two most important factors associated with self-reported sleep quality and duration. Good quality of sleep among long-lived old adults may have some implications for achieving healthy longevity.

Citation:

Gu D; Sautter J; Pipkin R; Zeng Y. Sociodemographic and health correlates of sleep quality and duration among very old Chinese. SLEEP 2010;33(5):601-610.

Keywords: China, healthy longevity survey, older adults, oldest-old, quality of sleep, sleep duration, sociodemographic factors

A NUMBER OF STUDIES HAVE REPORTED THAT OLDER AGE IS ASSOCIATED WITH INCREASED SLEEP PROBLEMS1–5 AND SHORTER SLEEP DURATION,6–8 YET THE association between older age and poor quality of sleep disappears once physical and mental health conditions are considered.2,9,10 In addition to health, other sociodemographic, social integration, and health behavior factors may be related to sleep quality and duration. Women have more sleep problems than men,1–3,11 and they are likely to sleep less.12 Ethnic/racial differences are also reported in the literature. For example, Whites report more sleep problems than non-Whites,11,13 and African Americans are more likely to report both short and long sleep duration,14 possibly because of racial/ethnic differences in predisposition, lifestyle, and culture.11,13 Yet, racial/ethnic differences are infrequently addressed outside of the United States. Non-urban residence maintains or promotes good sleep quality, possibly because noise or pollution in urban areas disturbs sleep.15 In terms of socioeconomic status, some studies find that low income and low education are associated with increased risk for insomnia12,16–17 and shorter daytime sleep,18 but other studies find that income19 and education3 are not associated with sleep problems. Lower levels of emotional social support or single marital status are also found to be associated with poor sleep quality.3,17,20 Finally, in terms of health behaviors, lack of physical exercise,2,15,20,21 smoking,1 and excessive alcohol use22,23 reduce sleep quality. However, one study found that the relationship between smoking, drinking, and exercise and sleep quality among Chinese elders in Shandong Province was not significant.3

It is well documented that poor quality of sleep and insufficient or excessive hours of sleep are associated with poor physical function, poor cognitive function, higher morbidity, poor quality of life, and excessive mortality rates.24–31 However, many studies have also shown that poor health is a risk factor for poor sleep quality. For instance, self-reported sleep problems are significantly greater among those with higher levels of depression/anxiety,11 chronic illnesses,1,11,20 mental illness,1,2,11 poor self-rated health,1,3,11 and poor functional status.32 Other studies further articulated that the association between sleep duration and mortality may be nonlinear.31,33 Overall, the causal relationship between sleep problems and health could be bi-directional and complex.

All of this previous research has contributed to our understanding of sleep quality and duration in old ages. Yet, age patterns of sleep quality and duration for the oldest-old, aged 80 years and older, remain largely unknown because most studies rely on data that lack relatively large samples of the oldest-old,10 especially nonagenarians and centenarians who provide the best opportunities to study healthy longevity. Furthermore, there is a paucity of studies examining sleep quality and duration among the elderly from China, a country with the largest elderly population in the contemporary world. So far, only a couple of locally based studies with a small sample size have investigated sleep issues among the Chinese elderly,1,3,19 and some have focused on Hong Kong or Taiwan. It is unclear whether the empirical findings in Western countries will hold in China, an Eastern developing country; for example, Chinese elders have earlier average waking and bed times than their Western counterparts.3 In addition, with few exceptions,33,34 many studies model sleep duration as a continuous variable35–37 and do not examine possible non-linear associations between sleep quality or sleep hours and health outcomes. Our research aimed to investigate sleep quality, duration, and their associated factors by using a nationally representative population-based survey dataset from mainland China with the largest sample of centenarians and nonagenarians in the current world.

DATA AND METHODOLOGY

Data Source

This study used data from the 2005 wave of the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS). The CLHLS, which began in 1998, is the first nationwide longitudinal survey focusing on the oldest-old ever conducted in a developing country. Interviews were conducted in randomly selected halves of the counties/cities in 22 of the 31 provinces in China. Among 22 sampled provinces, 21 provinces are predominantly populated by Han Chinese who normally have high accuracy in age reporting; one province is predominantly populated by those of Zhuang ethnicity who over the years have been culturally and residentially integrated with the Han. The CLHLS intended to interview all centenarians in the sampled counties/cities with informed consent. For each centenarian with a pre-designated random code, one nearby octogenarian and one nonagenarian of pre-designated age and sex were randomly chosen to be interviewed. The term “nearby” refers to the same village or street, or the same town, county or city, when applicable. This sampling strategy was designed to ensure comparable numbers of randomly selected male and female octogenarians and nonagenarians at each age from 80 to 99. We use the 2005 wave of the CLHLS because this was the first year that included questions on self-reported sleep quality and duration. The 2005 wave interviewed 15,638 individuals aged 65 and older, with 5,047 young seniors aged 65 to 79, and 10,591 oldest-old seniors aged 80 and older (3,870 octogenarians, 3,927 nonagenarians, and 2,794 centenarians); 6,688 respondents were men, and 8,950 were women.

In addition to data on sleep quality and hours of sleep, the 2005 wave collected data covering demographic characteristics, family and household characteristics, lifestyle, diet, psychological characteristics, economic resources, self-reported health, self-reported life satisfaction, lower and upper extremity performance, instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), activities of daily living (ADL), cognitive functioning, and chronic disease. All information was obtained through in-home interviews.

Several studies have shown that age reporting at very old ages in the CLHLS was quite accurate, close to that in Australia or Canada, and better than that in the United States, although less accurate than those in Japan and Sweden.38–41 The high quality of age reporting data in the CLHLS is mainly attributable to the fact that Han Chinese and some ethnic minorities use the Chinese lunar calendar and the Western calendar plus animal years to remember their birthdays (in addition to high quality data collection procedures adopted in the CLHLS study).38–41 Indeed, Han Chinese, even if illiterate, can usually provide a reliable date of birth for themselves or for their close family members because the precise date of birth is important for Chinese people in making decisions about major life events such as matchmaking for marriage, date of marriage, and the date to start building a house, among other events.41 One study using the 1981 census data showed that except for minorities in Xinjiang Province, the death rate among the Chinese oldest-old is quite accurate,42 and the CLHLS had higher data quality in age reporting than the census.39 Systematic assessments of the CLHLS regarding the reliability, validity, and consistency of numerous other measures and the randomness of attrition revealed good data quality.43

Variables

The 2005 CLHLS included one question about sleep quality: “how do you rate your sleep quality recently?” Response categories included: very good, good, fair, bad, and very bad. We dichotomized the sleep quality measure into good/very good (coded as 1) versus other (coded as 0). The survey also included one question about self-reported daily hours of sleep: “how many hours on average do you sleep every day including napping?” In order to capture possible non-linear associations between sleep duration and its associates, we followed a similar categorization used by two previous studies33,34 and classified sleep hours into ≤ 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and ≥ 10 hours per day.

To capture a relatively full spectrum of sleep patterns at old age, we attempted to examine as many factors as possible that have been found to be associated with sleep quality and hours of sleep in previous studies.33,34 These factors included demographics, socioeconomic status (SES), family/social connections, health practice, and health conditions. We further tested geographic differences. Demographic variables included chronological age, sex, ethnicity (Han vs. Non-Han), and urban/rural residence (urban vs. rural). We measured SES with education (1+ years of schooling vs. 0), self-reported family economic condition (good vs. other, as compared to other families), and access to healthcare when in need (yes vs. no). We measured social connection/support with current marital status (married vs. no), number of living children, and living arrangements (classified as living alone, living with spouse or family, or living in an institution). Health practice included whether the respondent was a smoker (yes vs. no) and whether the respondent was an alcohol user (yes vs. no) at the time of survey.

Health indicators were measured by ADL, IADL, cognitive function, self-rated health, chronic diseases suffered, and feelings of anxiety and fearfulness. ADL refers to basic personal care tasks of every day life. In this study, ADL disability was defined as self-reported difficulty with any of the following ADL items: (a) bathing, (b) dressing, (c) eating, (d) indoor transferring, (e) toileting, and (f) continence. Following previous studies,37 we dichotomized ADL functional capacity into “active” (no ADL limitation) and “disabled” (at least one ADL limitation). IADL disability was defined as self-reported difficulty with any of the following IADL items: (a) visiting neighbors, (b) shopping, (c) cooking, (d) washing clothes, (e) walking for 1 km, (f) lifting 5 kg weight, (g) crouching and standing up three times, and (h) taking public transportation. The reliability and validity of the IADL measures are reasonably good.34 We dichotomized IADL functional capacity into “active” (no IADL limitation) and “disabled” (at least one IADL limitation). Cognitive impairment was measured by the Chinese version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), which is adapted from the work of Folstein and his colleagues44 and tests the following aspects of cognitive functioning: orientation, registration, copy and design, calculation, recall, naming, and language (repetition, read and obey, write, and command). The Chinese version of the MMSE is intended to be consistent with the cultural and socioeconomic conditions in China and to make the questions easily understandable and answerable among normally functioning oldest-old Chinese. The Chinese version of the MMSE has been proven to be reliable and valid.38–40,45 We used a score of ≥ 18 out of a total of 30 as the cutoff value to classify a respondent as cognitively unimpaired because of the low level of education among Chinese elders.45 Self-rated health was assessed using a single item. Subjects were asked the question, “In general, would you say your health is: (1) very good, (2) good, (3) fair, (4) bad, or (5) very bad?” We dichotomized the measure of self-rated health into very good/good health versus fair/bad/very bad health, and treated it as a binary outcome to correct for its highly skewed distribution. Self-rated health has high predictive validity for mortality, physical disability, chronic disease status, health behaviors, and health care utilization.46 We measured chronic illness with a single dummy variable that indicated whether the respondent had any of 20 major chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, arthritis, cataracts, cancer, pneumonia, or Parkinson's disease at the time of the survey. The prevalence of chronic disease in the CLHLS is highly reliable as compared to other Chinese nationwide surveys.39 Finally, we examined a measure of feeling anxious or fearful that reflects psychological health. The variable “Do you have feelings of anxiety or fearfulness in daily life?” had 5 response categories: “always, often, sometimes, seldom, never”; we dichotomized the responses into always/often versus other.

METHODS

We used logistic regressions for analyses of dichotomous sleep quality and multinomial logit regressions for investigation of sleep duration. We constructed 3 sequential models for both logistic regressions and multinomial logit regressions. Model I looked at the effect of age as well as other demographics and geographic location on sleep quality and duration; Model II further examined associations for SES, social connection, and health practices; Model III added health conditions into the analyses. In multinomial logit models, we used the category of 8 h of sleep as the reference group, which has the highest weighted frequency (see Table 1). Analyses using the category of 7 h as the reference group produced similar results. We chose these reference categories because some studies reported that those who slept 7 or 8 h usually had the lowest mortality risk.29,30

Table 1.

Sample distribution by sleep quality, duration, and other study variables

| Sample size |

Good sleep quality (%) | Sleep duration (hours per day) (%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ≤ 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ≥ 10 | ||

| Total | 15,638 | 100.0 | 63.8 | 12.4 | 14.6 | 13.8 | 22.9 | 7.7 | 28.6 |

| (100.0) | (65.0) | (13.1) | (16.2) | (18.0) | (28.0) | (9.2) | (15.5) | ||

| Ages 65-79 | 5,047 | 32.3 | 65.2 | 13.0 | 16.3 | 18.4 | 28.3 | 9.1 | 14.9 |

| Ages 80-89 | 3,870 | 24.7 | 63.0 | 14.2 | 14.9 | 13.1 | 23.6 | 7.8 | 26.4 |

| Ages 90-99 | 3,927 | 25.1 | 63.4 | 11.0 | 14.1 | 11.8 | 20.2 | 6.8 | 36.1 |

| Age 100+ | 2,794 | 17.9 | 63.8 | 10.9 | 12.0 | 9.1 | 15.9 | 6.2 | 45.9 |

| Women | 8,950 | 57.2 | 60.6 | 13.1 | 15.0 | 13.6 | 21.0 | 7.1 | 30.2 |

| Men | 6,688 | 42.8 | 68.4 | 11.5 | 14.1 | 14.0 | 25.4 | 8.5 | 26.5 |

| Minority ethnicity | 964 | 6.2 | 53.8 | 12.7 | 14.2 | 14.3 | 22.0 | 8.1 | 28.7 |

| Han ethnicity | 14,674 | 93.8 | 64.6 | 12.4 | 14.7 | 13.7 | 23.0 | 7.7 | 28.6 |

| Rural | 8,659 | 55.4 | 64.2 | 12.2 | 14.5 | 13.3 | 22.5 | 7.7 | 29.8 |

| Urban | 6,979 | 44.6 | 63.9 | 12.8 | 14.9 | 14.3 | 23.4 | 7.6 | 27.0 |

| North | 897 | 5.7 | 63.3 | 12.5 | 14.8 | 14.1 | 22.4 | 7.1 | 29.1 |

| Northeast | 1,497 | 9.6 | 71.3 | 12.8 | 14.8 | 15.2 | 21.9 | 6.7 | 28.6 |

| East | 6,087 | 38.9 | 64.5 | 11.3 | 13.5 | 14.3 | 22.4 | 8.3 | 30.2 |

| Central/South | 4,660 | 29.8 | 57.1 | 11.7 | 15.0 | 13.1 | 22.5 | 8.5 | 29.2 |

| West | 2,497 | 16.0 | 70.9 | 16.4 | 16.6 | 12.8 | 25.5 | 5.4 | 23.3 |

| 0 years of schooling | 9,587 | 61.3 | 62.0 | 12.7 | 14.7 | 13.1 | 21.0 | 7.2 | 31.3 |

| 1+ years of schooling | 6,051 | 38.7 | 66.8 | 12.0 | 14.6 | 14.7 | 25.8 | 8.5 | 24.4 |

| Poor family economic condition | 13,138 | 84.0 | 61.8 | 13.1 | 14.9 | 13.8 | 22.4 | 7.5 | 28.3 |

| Good family economic condition | 2,500 | 16.0 | 75.1 | 9.0 | 13.2 | 13.7 | 25.2 | 8.6 | 30.3 |

| Did not get adequate medical service | 1,793 | 11.5 | 45.0 | 19.7 | 16.1 | 12.2 | 19.0 | 6.9 | 27.1 |

| Got adequate medical service | 13,845 | 88.5 | 66.3 | 11.5 | 14.5 | 13.9 | 23.4 | 7.9 | 28.8 |

| Not married | 10,556 | 67.5 | 62.8 | 12.7 | 14.4 | 12.4 | 20.3 | 6.9 | 33.4 |

| Married | 5,082 | 32.5 | 66.4 | 11.8 | 15.1 | 16.9 | 28.3 | 9.3 | 18.6 |

| 0 or 1 living child | 2,522 | 16.1 | 60.6 | 13.6 | 13.8 | 12.3 | 20.7 | 6.8 | 32.8 |

| 2 living children | 2,188 | 14.0 | 64.2 | 11.7 | 16.1 | 13.4 | 21.5 | 6.8 | 30.5 |

| 3 living children | 3,022 | 19.3 | 63.3 | 12.2 | 16.0 | 14.1 | 21.9 | 8.3 | 27.5 |

| 4 living children | 3,024 | 19.4 | 64.4 | 11.3 | 14.4 | 14.8 | 23.8 | 8.0 | 27.7 |

| 5 living children | 2,412 | 15.4 | 67.0 | 12.5 | 14.0 | 13.7 | 25.1 | 8.0 | 26.7 |

| 6+ living children | 2,470 | 15.8 | 64.2 | 13.4 | 13.4 | 11.9 | 24.2 | 8.0 | 27.1 |

| Live alone | 2,097 | 13.4 | 59.4 | 14.6 | 16.0 | 14.3 | 22.0 | 7.6 | 25.5 |

| Live with spouse or family | 13,119 | 83.9 | 64.9 | 11.9 | 14.3 | 13.8 | 23.2 | 7.7 | 29.1 |

| Live in an institution | 422 | 2.7 | 55.7 | 17.5 | 18.0 | 11.1 | 16.4 | 7.1 | 29.9 |

| Current nonsmoker | 12,633 | 80.8 | 62.4 | 12.7 | 14.9 | 13.7 | 22.0 | 7.3 | 29.4 |

| Current smoker | 3,005 | 19.2 | 70.1 | 11.3 | 13.6 | 13.9 | 26.4 | 9.4 | 25.4 |

| Current non-consumer of alcohol | 12,492 | 79.9 | 62.1 | 12.7 | 15.1 | 13.8 | 22.3 | 7.4 | 28.7 |

| Current alcohol consumer | 3,146 | 20.1 | 71.0 | 11.5 | 13.0 | 13.5 | 25.1 | 8.8 | 28.1 |

| IADL not disabled | 4,912 | 31.4 | 72.5 | 10.4 | 15.2 | 17.9 | 29.4 | 10.0 | 17.1 |

| IADL disabled | 10,726 | 68.6 | 60.0 | 13.4 | 14.4 | 11.9 | 19.9 | 6.6 | 33.8 |

| ADL not disabled | 11,704 | 74.8 | 66.0 | 12.1 | 15.1 | 15.3 | 25.4 | 8.4 | 23.7 |

| ADL disabled | 3,934 | 25.2 | 57.5 | 13.3 | 13.4 | 9.1 | 15.4 | 5.7 | 43.1 |

| Cognitively unimpaired | 9,527 | 60.9 | 67.2 | 11.4 | 15.1 | 15.8 | 26.0 | 8.8 | 22.9 |

| Cognitively impaired | 6,111 | 39.1 | 58.8 | 14.0 | 13.9 | 10.6 | 18.0 | 6.0 | 37.5 |

| Self-rated good health | 11,995 | 76.7 | 68.8 | 10.2 | 14.5 | 15.0 | 24.9 | 8.5 | 26.9 |

| Self-rated poor health | 3,643 | 23.3 | 47.6 | 19.7 | 15.2 | 9.7 | 16.1 | 5.2 | 34.1 |

| Have no chronic diseases | 5,300 | 33.9 | 72.5 | 8.4 | 13.1 | 14.8 | 26.2 | 8.9 | 28.6 |

| Have 1+ chronic diseases | 10,338 | 66.1 | 59.5 | 14.5 | 15.4 | 13.3 | 21.2 | 7.0 | 28.6 |

| Do not often feel anxious or fearful | 14,943 | 95.6 | 64.7 | 11.9 | 14.5 | 13.8 | 23.2 | 7.8 | 28.8 |

| Often feel anxious or fearful | 695 | 4.4 | 47.3 | 23.3 | 16.7 | 13.8 | 17.1 | 5.2 | 24.9 |

Figures in the parentheses are weighted, while all others are unweighted.

To reduce possible biases in our data analysis and inference due to missing items (although only about 2% of the data are missing for any variable), we imputed missing values with the variable mean for continuous variables, and with the mode of the variable for categorical variables.47 We also tested other imputation approaches (such as median, simple regression, and multiple imputations). All of them yielded similar results. Given that the sampling weight variable in the publicly released CLHLS dataset is calculated based on the age-sex-urban/rural residence-specific distribution of the population and does not capture other important compositional variables, such as marital status and economic status, we did not apply sample weights in the regression analyses. Research has shown that including variables related to sample selection in the regression produces unbiased coefficients without weights47; additionally, weighted regression results are likely to enlarge the standard errors.48 However, we did apply the weight in the cases when we referred to the general elderly population. We performed all analyses using STATA 10.1.

RESULTS

Table 1 lists the distribution of the sample by study variable. Overall, the weighted prevalence of reporting good sleep quality was approximately 65% (the unweighted figure was 64%). The sleep duration category with the highest weighted prevalence was 8 h (28.0%). The weighted average number was 7.5 h (SD 1.9), which is close to a local study of elders in China that reported the average sleeping h of 7.1 (SD 1.6).3

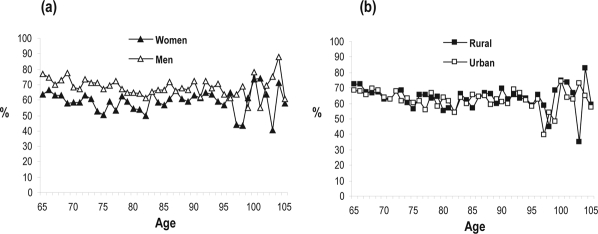

Figure 1 presents the observed age-specific prevalence of good sleep quality by sex and residence, showing that there was no upward or downward trend in observed rates of good sleep quality over age. We observed no urban/rural difference, but found that men tended to have a higher prevalence of good sleep than women. Figure 2 illustrates the average hours of daily sleep by age, sex, and residence. Again, no clear pattern was found across age by sex or by residence.

Figure 1.

Observed age-specific prevalence of good sleep quality by sex and residence, CLHLS, 2005

Figure 2.

Observed age-specific average daily hours of sleep by sex and residence, CLHLS, 2005

Table 2 presents odds ratios from logistic regressions demonstrating the associations of demographics, SES, family/social support and connection, and health practice with sleep quality. Model I revealed that there was no significant age pattern for sleep quality when only major demographic factors were taken into consideration, which is in line with the observed data presented in Figure 1. Elderly men were 42% more likely to report good sleep quality than women. As compared to non-Han elders, Han elders were 34% more likely to report good sleep quality. Urban elders were 9% less likely to report good sleep quality as compared to their rural counterparts. Elders from Northeast and West China had 33% and 43% higher odds than elders from North China of reporting good sleep quality, respectively; elders from Central/South China had 22% reduced odds than their counterparts from North China of reporting good sleep quality. Elders from North China and East China shared similar quality of sleep.

Table 2.

Factors associated with good quality of sleep, CLHLS, 2005

| Model I | Model II | Model III | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ages 80-89 (ages 65-79) | 0.92 (0.84,1.01) | 0.96 (0.88,1.06) | 1.19 (1.07,1.32)** |

| Ages 90-99 (ages 65-79) | 0.98 (0.90,1.07) | 1.04 (0.94,1.15) | 1.38 (1.23,1.55)*** |

| Ages 100+ (ages 65-79) | 1.06 (0.96,1.17) | 1.13 (1.00,1.26)* | 1.70 (1.48,1.95)*** |

| Men | 1.42 (1.32,1.52)*** | 1.27 (1.17,1.39)*** | 1.23 (1.12,1.34)*** |

| Han ethnicity | 1.34 (1.17,1.54)*** | 1.32 (1.15,1.51)*** | 1.47 (1.27,1.69)*** |

| Urban | 0.91 (0.85,0.97)** | 0.86 (0.80,0.92)*** | 0.88 (0.82,0.94)*** |

| Northeast (north) | 1.43 (1.20,1.71)*** | 1.48 (1.24,1.77)*** | 1.53 (1.27,1.84)*** |

| East (north) | 1.03 (0.89,1.19) | 1.04 (0.90,1.21) | 1.01 (0.87,1.18) |

| Central/South (north) | 0.78 (0.67,0.90)** | 0.84 (0.72,0.98)* | 0.77 (0.66,0.90)** |

| West (north) | 1.36 (1.16,1.60)*** | 1.43 (1.21,1.69)*** | 1.33 (1.12,1.58)*** |

| 1+ years of schooling | 1.00 (0.92,1.08) | 0.98 (0.90,1.06) | |

| Good family economic condition | 1.67 (1.52,1.85)*** | 1.56 (1.41,1.73)*** | |

| Got adequate medical service | 2.20 (1.98,2.44)*** | 1.84 (1.66,2.05)*** | |

| Married | 1.00 (0.92,1.10) | 0.98 (0.89,1.08) | |

| No. of living children | 1.00 (0.98,1.02) | 1.00 (0.99,1.02) | |

| Live with spouse or family (alone) | 1.11 (1.01,1.23)* | 1.17 (1.05,1.30)* | |

| Institutionalized (alone) | 0.78 (0.63,0.98)* | 0.85 (0.68,1.07) | |

| Current smoker | 1.13 (1.03,1.25)** | 1.06 (0.96,1.17) | |

| Current alcohol consumer | 1.27 (1.16,1.39)*** | 1.16 (1.05,1.27)** | |

| IADL disabled | 0.66 (0.60,0.72)*** | ||

| ADL disabled | 0.89 (0.81,0.98)* | ||

| Cognitively impaired | 0.95 (0.87,1.04) | ||

| Self-rated poor health | 0.54 (0.50,0.59)*** | ||

| Have 1+ chronic diseases | 0.66 (0.61,0.71)*** | ||

| Often anxious | 0.62 (0.53,0.73)*** | ||

| -LL | 10072.8*** | 9845.4*** | 9506.8*** |

Numbers in the table are odds ratios and the 95% confidence intervals based on binary logistic regression. Category in the parentheses is the reference for categorical variables. All other variables are dichotomous.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001.

Model II showed that the significant associations between sleep quality and variables in Model I still persisted although some odds were reduced (and a few increased) once socioeconomic condition, family/social support, and health practice were added into the analyses. Interestingly, centenarians were 13% more likely to have good sleep quality as compared to young elders aged 65-79 when socioeconomic status, social/family support, and health practice were additionally controlled for. Education was not significantly associated with sleep quality, but good family economic status and adequate access to healthcare increased the odds of reporting good sleep quality by 67% and 120%, respectively. Additional exploratory analyses (not shown in the table) with age and education as the only covariates revealed that elders with some education were 23% more likely than the non-educated to have good sleep quality, but the significance disappeared once gender was included as an additional control. This indicated that gender may explain the major educational variation in sleep quality.

Marriage and number of living children had no relationship with sleep quality, whereas living arrangements seemed to be associated with quality of sleep. As compared to those living alone, living with a spouse or family member increased the odds of having good sleep quality by 11%, whereas institutionalization decreased the odds by 22%. Current smokers had 13% increased odds of reporting good quality of sleep as compared to nonsmokers; current alcohol consumers had 27% increased odds of reporting good quality of sleep as compared to those who do not consume alcohol.

When health conditions were added in the model (Model III), octogenarians, nonagenarians, and centenarians were 19%, 38%, and 70% more likely to have a good quality of sleep than young elders, respectively. The patterns for all other previous factors in Model II persisted in Model III, except that the effect of institutionalization and smoking became nonsignificant. With the exception of cognitive impairment, all other poor health conditions were negatively associated with the quality of sleep.

Table 3 summarizes associations of sleep duration with all study variables based on sequential multinomial logit models. Model I demonstrated that very old Chinese were more likely than young elders aged 65-79 to report short (≤ 6 h) or long (≥ 10 h) duration of daily sleep, with more pronounced effects for longer sleep duration. Compared to women, men were 17% to 25% less likely to report ≤ 7 h of sleep. Urban elders were 17% less likely to sleep ≥ 10 h than their rural counterparts, whereas elders from West China were 34% to 35% less likely to have ≥ 9 h of sleep than their Northern counterparts. We found no significant pattern for ethnicity or among other geographic areas.

Table 3.

Factors associated with sleep duration, CLHLS, 2005

| Model I | ≤ 5 h vs 8 h | 6 h vs 8 h | 7 h vs 8 h | 9 h vs 8 h | ≥ 10 h vs 8 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages 80-89 (ages 65-79) | 1.30 (1.13,1.50)*** | 1.10 (0.96,1.25) | 0.86 (0.75,0.99)* | 1.03 (0.87,1.22) | 2.15 (1.90,2.44)*** |

| Ages 90-99 (ages 65-79) | 1.15 (0.99,1.34) | 1.18 (1.03,1.36)* | 0.89 (0.77,1.02) | 1.03 (0.86,1.22) | 3.39 (2.99,3.84)*** |

| Ages 100+ (ages 65-79) | 1.35 (1.13,1.61)** | 1.21 (1.02,1.44)* | 0.84 (0.70,1.00) | 1.23 (0.99,1.52) | 5.46 (4.74,6.30)*** |

| Men | 0.75 (0.66,0.84)*** | 0.80 (0.72,0.89)*** | 0.83 (0.75,0.93)** | 1.04 (0.91,1.19) | 0.92 (0.84,1.01) |

| Han ethnicity | 0.92 (0.72,1.17) | 1.04 (0.83,1.32) | 0.90 (0.71,1.13) | 0.99 (0.75,1.31) | 1.07 (0.88,1.31) |

| Urban | 1.01 (0.90,1.13) | 0.99 (0.89,1.11) | 1.01 (0.91,1.13) | 0.95 (0.83,1.09) | 0.83 (0.75,0.91)*** |

| Northeast (north) | 1.07 (0.80,1.44) | 1.04 (0.79,1.38) | 1.10 (0.83,1.45) | 0.96 (0.68,1.37) | 1.06 (0.84,1.35) |

| East (north) | 0.91 (0.71,1.17) | 0.91 (0.72,1.15) | 1.02 (0.81,1.30) | 1.15 (0.86,1.56) | 1.02 (0.83,1.25) |

| Central/South (north) | 0.91 (0.70,1.18) | 1.00 (0.79,1.28) | 0.91 (0.71,1.17) | 1.17 (0.86,1.60) | 0.92 (0.75,1.13) |

| West (north) | 1.15 (0.89,1.50) | 0.98 (0.76,1.26) | 0.81 (0.62,1.05) | 0.66 (0.47,0.93)* | 0.65 (0.52,0.81)*** |

| Model II | |||||

| Ages 80-89 (ages 65-79) | 1.13 (0.97,1.32) | 1.00 (0.86,1.15) | 0.84 (0.72,0.97)* | 1.04 (0.87,1.25) | 1.88 (1.64,2.15)*** |

| Ages 90-99 (ages 65-79) | 0.96 (0.81,1.14) | 1.03 (0.88,1.21) | 0.85 (0.72,0.99)* | 1.05 (0.87,1.27) | 2.78 (2.42,3.20)*** |

| Ages 100+ (ages 65-79) | 1.10 (0.90,1.34) | 1.04 (0.86,1.26) | 0.80 (0.65,0.98)* | 1.27 (1.00,1.60)* | 4.33 (3.68,5.09)*** |

| Men | 0.88 (0.76,1.02) | 0.93 (0.81,1.06) | 0.90 (0.79,1.04) | 0.99 (0.83,1.16) | 1.03 (0.91,1.15) |

| Han ethnicity | 0.95 (0.75,1.21) | 1.06 (0.84,1.33) | 0.90 (0.71,1.13) | 0.99 (0.75,1.32) | 1.09 (0.90,1.33) |

| Urban | 1.06 (0.95,1.20) | 1.00 (0.89,1.11) | 1.02 (0.91,1.14) | 0.95 (0.83,1.09) | 0.83 (0.75,0.91)*** |

| Northeast (north) | 1.06 (0.79,1.42) | 1.05 (0.79,1.39) | 1.10 (0.83,1.45) | 0.95 (0.67,1.37) | 1.07 (0.84,1.36) |

| East (north) | 0.89 (0.69,1.14) | 0.90 (0.71,1.14) | 1.01 (0.80,1.29) | 1.14 (0.84,1.55) | 1.03 (0.84,1.26) |

| Central/South (north) | 0.84 (0.65,1.09) | 0.97 (0.76,1.24) | 0.90 (0.70,1.15) | 1.18 (0.86,1.60) | 0.93 (0.75,1.14) |

| West (north) | 1.11 (0.85,1.44) | 0.97 (0.75,1.25) | 0.81 (0.62,1.05) | 0.65 (0.46,0.91)* | 0.65 (0.52,0.81)*** |

| 1+ years of schooling | 0.95 (0.83,1.09) | 0.93 (0.82,1.05) | 0.94 (0.83,1.07) | 0.99 (0.85,1.16) | 0.96 (0.86,1.07) |

| Good family economic condition | 0.69 (0.58,0.81)*** | 0.84 (0.72,0.97)* | 0.91 (0.79,1.05) | 1.01 (0.85,1.21) | 0.99 (0.87,1.11) |

| Got adequate medical service | 0.50 (0.43,0.60)*** | 0.79 (0.67,0.94)** | 0.93 (0.78,1.12) | 1.11 (0.88,1.41) | 0.97 (0.83,1.13) |

| Married | 0.78 (0.67,0.91)** | 0.87 (0.76,1.00) | 0.99 (0.86,1.14) | 1.02 (0.86,1.21) | 0.68 (0.60,0.77)*** |

| No. of living children | 1.01 (0.98,1.04) | 0.97 (0.94,1.00) | 0.99 (0.96,1.02) | 1.01 (0.97,1.04) | 0.99 (0.97,1.01) |

| Live with spouse/family (alone) | 0.92 (0.78,1.09) | 0.93 (0.79,1.09) | 0.93 (0.79,1.10) | 0.97 (0.79,1.19) | 1.21 (1.05,1.40)** |

| Institutionalized (alone) | 1.75 (1.21,2.53)** | 1.47 (1.03,2.12)* | 1.08 (0.72,1.62) | 1.30 (0.81,2.09) | 1.44 (1.04,2.00)* |

| Current smoker | 0.85 (0.73,0.99)* | 0.87 (0.75,1.01) | 0.90 (0.70,1.15) | 1.13 (0.95,1.35) | 1.00 (0.88,1.13) |

| Current alcohol user | 0.95 (0.82,1.10) | 0.86 (0.75,0.99)* | 0.81 (0.62,1.05) | 1.06 (0.90,1.25) | 1.03 (0.92,1.16) |

| Model III | ≤ 5 h vs 8 h | 6 h vs 8 h | 7 h vs 8 h | 9 h vs 8 h | ≥ 10 h vs 8 h |

| Ages 80-89 (ages 65-79) | 0.95 (0.81,1.13) | 0.93 (0.79,1.08) | 0.84 (0.72,0.98)* | 1.07 (0.89,1.30) | 1.56 (1.35,1.79)*** |

| Ages 90-99 (ages 65-79) | 0.76 (0.63,0.92)** | 0.93 (0.78,1.10) | 0.86 (0.72,1.03) | 1.08 (0.87,1.35) | 2.02 (1.72,2.37)*** |

| Ages 100+ (ages 65-79) | 0.76 (0.61,0.95)* | 0.87 (0.70,1.08) | 0.82 (0.66,1.03) | 1.29 (0.98,1.68) | 2.68 (2.23,3.22)*** |

| Men | 0.92 (0.80,1.07) | 0.95 (0.83,1.09) | 0.91 (0.79,1.04) | 0.98 (0.83,1.15) | 1.07 (0.95,1.21) |

| Han ethnicity | 0.85 (0.67,1.08) | 1.00 (0.79,1.26) | 0.90 (0.71,1.13) | 1.00 (0.75,1.32) | 1.02 (0.84,1.25) |

| Urban | 1.03 (0.91,1.16) | 0.97 (0.87,1.09) | 1.01 (0.90,1.13) | 0.95 (0.82,1.09) | 0.80 (0.78,0.88)*** |

| Northeast (north) | 1.05 (0.78,1.41) | 1.05 (0.78,1.41) | 1.10 (0.83,1.46) | 0.95 (0.66,1.36) | 1.05 (0.83,1.34) |

| East (north) | 0.92 (0.71,1.18) | 1.04 (0.79,1.38) | 1.01 (0.79,1.28) | 1.16 (0.86,1.57) | 1.12 (0.91,1.38) |

| Central/South (north) | 0.91 (0.70,1.18) | 0.92 (0.72,1.17) | 0.90 (0.70,1.16) | 1.20 (0.88,1.63) | 1.06 (0.86,1.32) |

| West (north) | 1.21 (0.92,1.59) | 1.02 (0.80,1.31) | 0.81 (0.62,1.06) | 0.66 (0.47,0.93)* | 0.73 (0.58,0.91)** |

| 1+ years of schooling | 0.97 (0.84,1.11) | 1.03 (0.80,1.33) | 0.93 (0.82,1.06) | 0.99 (0.84,1.16) | 0.98 (0.87,1.09) |

| Good family economic condition | 0.76 (0.64,0.90)** | 0.86 (0.74,1.00) | 0.90 (0.78,1.05) | 1.01 (0.85,1.20) | 1.04 (0.92,1.18) |

| Got adequate medical service | 0.64 (0.54,0.76)*** | 0.87 (0.73,1.03) | 0.93 (0.78,1.13) | 1.09 (0.86,1.39) | 1.07 (0.92,1.25) |

| Married | 0.79 (0.67,0.91)** | 0.87 (0.76,1.00) | 0.99 (0.96,1.14) | 1.01 (0.85,1.20) | 0.70 (0.62,0.80)*** |

| No. of living children | 1.01 (0.98,1.04) | 0.97 (0.94,1.00) | 0.99 (0.96,1.02) | 1.01 (0.97,1.04) | 0.99 (0.96,1.01) |

| Live with spouse/family (alone) | 0.90 (0.75,1.06) | 0.90 (0.78,1.04) | 0.94 (0.79,1.11) | 0.96 (0.78,1.18) | 1.11 (0.96,1.28) |

| Institutionalized (alone) | 1.60 (1.10,2.33) | 1.40 (0.97,2.01) | 1.08 (0.72,1.62) | 1.29 (0.81,2.09) | 1.27 (0.91,1.77) |

| Current smoker | 0.92 (0.79,1.08) | 0.90 (0.78,1.04) | 0.90 (0.77,1.04) | 1.13 (0.95,1.35) | 1.05 (0.92,1.19) |

| Current alcohol consumer | 1.06 (0.91,1.23) | 0.90 (0.77,1.05) | 0.93 (0.81,1.07) | 1.05 (0.89,1.24) | 1.11 (0.98,1.25) |

| IADL disabled | 1.35 (1.15,1.57)*** | 1.13 (0.98,1.30) | 0.99 (0.86,1.14) | 0.89 (0.75,1.05) | 1.28 (1.13,1.45)*** |

| ADL disabled | 1.14 (0.96,1.34) | 1.19 (1.02,1.40)* | 0.97 (0.82,1.15) | 1.16 (0.95,1.42) | 1.65 (1.45,1.88)*** |

| Cognitively impaired | 1.10 (0.95,1.27) | 0.99 (0.86,1.13) | 0.99 (0.86,1.14) | 1.00 (0.83,1.19) | 1.16 (1.03,1.30)* |

| Self-rated poor health | 2.10 (1.82,2.70)*** | 1.30 (1.13,1.51)*** | 0.95 (0.81,1.11) | 0.94 (0.77,1.15) | 1.30 (1.15,1.47)*** |

| Have 1+ chronic diseases | 1.78 (1.55,2.02)*** | 1.36 (1.21,1.52)*** | 1.11 (0.99,1.24) | 0.99 (0.86,1.13) | 1.12 (1.01,1.24)* |

| Often anxious | 2.02 (1.57,2.60)*** | 1.36 (1.04,1.78)* | 1.33 (1.00,1.75)* | 0.91 (0.63,1.34) | 0.98 (0.76,1.26) |

Numbers in the table are odds ratios and the 95% confidence intervals (in parentheses) based on multinomial logistic regression. The category in the parentheses is the reference for those categorical variables. All other variables are dichotomous.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001.

Once SES, family/social support, and health practice were considered, patterns for age and gender changed (Model II). There was no significant difference across ages with respect to short sleep hours, but the age difference for long sleep hours was still significant, despite some reductions in odds ratios. The gender difference was no longer significant. Yet the significant differences between urban and rural areas and between West and North China for long sleep hours (≥ 10) persisted.

Model II further revealed that higher family income and adequate access to medical service deceased odds of reporting ≤ 6 h of daily sleep. Married elders were 22%, 13%, and 32% less likely than unmarried elders to have ≤ 5, 6, and ≥ 10 h of sleep, respectively. Institutionalized elders were more likely than elders living alone to report ≤ 6 h or ≥ 10 h of sleep.

Model III showed that nonagenarians and centenarians were 24% less likely to sleep ≤ 5 h than young elders aged 65-79, once health conditions were taken into consideration. No other significant changes were found for other variables from Model II, except that the effect of SES in the 6-h versus 8-h category became nonsignificant. In other words, poor health did not account for the associations between sleep duration and most other variables, except for age. Yet, with respect to the association between health conditions and sleep duration, poor health conditions tended to increase the odds of reporting either ≤ 6 h or ≥ 10 h of sleep.

One interesting finding in Table 3 was that the Chinese elders' profiles for sleep duration of 7, 8, or 9 h were similar regardless of respondents' demographics, socioeconomic conditions, social/family support, health practice, and health conditions. This indicated that Chinese elders who slept for 7-9 h per day were a homogeneous group rather a heterogeneous one. If these 3 categories of sleep hours were more likely to have lower mortality risks and better health conditions than other categories as noted in previous studies,24–31 we may speculate that these elders who slept 7-9 h per day were more likely to be healthy, and that healthy elders, regardless of their characteristics, shared a similar frequency of sleep duration.

DISCUSSION

We investigated general patterns of sleep quality and daily hours of sleep and associated sociodemographic, social connection, and health factors among very old persons using data with the largest sample of nonagenarians and centenarians in the current world from a nationwide survey in mainland China. To our knowledge, this study was the first to use nationally representative data to examine sleep quality and hours of sleep among elders in mainland China. It was also the first attempt to examine sleep issues in a relatively large sample of exceptionally long-lived persons.

With the exception of a few health indicators, poorer health conditions were associated with poorer sleep quality and shorter or longer sleeping hours (compared to 7-9 hours) regardless of individual characteristics, which is in line with earlier reports.20,24 We further found that oldest-old adults aged 80 or older tended to sleep either shorter or longer as compared to young elders. This is because when the old adults get older, their health condition gets worse, on average. Yet, the quality of sleep of the oldest-old did not differ much from that of young elders; and the former even had better sleep quality than the latter when demographics, SES, family/social support and connection, health practice, and health conditions were controlled for. This is in accordance with an Italian centenarian study which reported that long-lived individuals had better self-rated quality of sleep.28 This may also support the notion that the majority of healthy elders could experience satisfactory sleep quality.49 Overall, these findings may support the argument that sleep problems at old and oldest-old ages likely arise from a variety of physiological and psychosocial factors rather than aging per se.2,3,5 They might also imply that healthy long-lived individuals may adapt their perception of what is “acceptable” sleep and therefore do not report poor sleep quality even if objective quality of sleep does change with advancing age.50

Consistent with previous research, we found that men's self-rated quality of sleep was consistently better than that of women. There are many possible reasons for this sleep differential in gender among elders, including biological differences in terms of estrogen deficiency,23,51,52 prior psychiatric illness,53 and caregiving roles.13 Yet, women's disadvantage may be reversed when quality of sleep is assessed with actigraphy.5 Urban/rural difference in the quality of sleep might be due in part to different lifestyles between urban and rural areas and in part to environmental influence. Indeed, noise or pollution were possible major causes of poor sleep among urban elders.15 Similarly, geographic differences in sleep quality and duration might also result from different lifestyles. The significant ethnic difference in likelihood of good sleep quality that might be attributed to different cultures or lifestyle factors reported in the West were also observed in the present study.

In line with prior research,12,18 we showed that resource-rich elders slept longer than resource-poor elders, and the former had better sleep quality than the latter. More economic and personal resources allow those individuals with higher SES to respond more favorably to adverse events and avoid risky behaviors.54 However, controlling for demographics, education was not associated with sleep quality. We speculate that this may be related to the uniqueness of the historical experience of older Chinese cohorts. Education of Chinese elders is a variable reflecting their childhood condition rather than adult condition, since most current Chinese elders, especially women, could not go to school when they were children because of very limited educational facilities. Although some young elders attended school during adulthood in the national illiteracy eradication movement,55 prevalence of literacy is much lower among women (34%) than among men (75%). Further, a majority of Chinese elders are illiterate, and some literate elders might have been politically persecuted during the Cultural Revolution. Thus, education might not be a good indicator of SES for Chinese elders. The nonsignificant association between education and sleep problems was also found by Liu and Liu3 from local data in China.

Another factor unique to the Chinese elderly is that China established a healthcare system in the 1950s, in which urban, but not rural, residents were entitled to free public medical service access and social security after retirement. Although this system has been reformed since the 1990s, the majority of the current old cohorts were not affected by the reform. It is possible that those persons with access to healthcare, who are more likely to be urban residents, could be more likely to rely on sleeping drugs than those who have difficulties in accessing healthcare. Thus, access to healthcare is an important indicator that captures both rural/urban status and likelihood of using sleep medication in the Chinese context.

Our findings for family/social support and connection were similar to prior reports in the literature.3,17,20 Elders living alone were less likely to have good quality of sleep, which provides evidence supporting a previous study by Geroldi et al.,5 who found that socially disadvantaged old people aged 75 and older suffered more frequent sleep problems. One interesting finding is that marriage was positively associated with good sleep quality in a bivariate model with chronological age controlled, but was not significantly associated with sleep quality once other covariates were present. This may indicate that the protective effect of marriage on sleep quality is largely determined by other factors at very old ages.

In contrast to previous findings, we found that current smokers or alcohol users were more likely to have good sleep quality. This paradoxical finding might be due to the fact that smokers or drinkers were relatively healthy in the CLHLS. Another possible explanation for this association might be that we did not distinguish level of smoking or drinking and types of alcohol used (wine, beer, or liquor). Further more nuanced research on smoking and alcohol use, especially among the very selective oldest-old population, is warranted.

In summary, like two previous studies,33,34 one strength of the present study lies its analytical strategy in using multinomial logit regression that allowed us to identify important differences in the predictors of both relatively short and relatively long sleep durations. These insights into the nonlinear effects of covariates on sleep duration might provide a new arena for modeling self-reported sleep duration beyond continuous36,57 or dichotomous measures.6,58

Nevertheless, several limitations of this study should be taken into account when interpreting the results. First, due to the cross-sectional nature of the data, we were unable to explore the possible causal relationships between health conditions and quantity and quality of sleep. It seems plausible that there would be a bidirectional relationship between sleep quality and healthy longevity.51 Once the 2008 wave data are released, we will extend our current preliminary results to examine how sleep quality and duration in 2005 are associated with health conditions in 2008 and vice versa.

Second, the data on sleep quality and sleep duration in the CLHLS were self-reported. Although subjective evaluation of sleep is likely to be important, this type of measure is not standardized due to different questions asked by different investigators in surveys, which may limit comparability with other studies. And more importantly, subjective measures and some objective measures such as actigraphy may yield different results.5

Third, unlike some previous studies based on more detailed sleep data, the present study examined very basic patterns of sleep quality and hours among Chinese elders. More detailed questions, including data on the duration, frequency, or severity of sleep problems suffered by older adults would be informative.

Fourth, use of sleep medication (both Western and Chinese herbal/botanical) was not measured in the CLHLS. Thus, we were unable to distinguish between people who have sleep problems that are corrected by sleep medications or other drugs that affect sleep and people who do not have sleep problems. Given that use of medication is associated with quality of sleep,3,59,60 this mixture of corrected and non-corrected sleep patterns might introduce some bias into the estimates. For example, medications not specifically prescribed for sleep, such as anticholinergic medications for incontinence and ulcers, affect both sleep and cognitive performance; however, one study shows that there is still a significant relationship between sleep quality and cognition after controlling for potentially confounding factors such as medication use, cerebrovascular disease, and depression.28 Empirical studies have shown that approximately 3% to 7% of seniors in China use sleep medicines,1,3 so such biases might not be very harmful to our general conclusions. However, further research that controls for these confounders is warranted.

Fifth, also related to the last two points, some neighborhood factors (such as noise, pollution, and so forth) might be associated with sleep quality and even mediate the relationship between urban/rural residence, SES, and sleep quality. Integration of these factors into analysis is rare in the existing literature but might have important implications for sleep intervention through environmental improvement. In spite of these shortcomings, we have extended the existing research by providing new estimates of sleep quality, duration, and associated factors among a unique, large sample of oldest-old adults from a developing country where the population of elders grows fast and their sleep problems are largely unknown. The results of this study help us to understand patterns of quantity and quality of sleep and their associations with health status among exceptionally long-lived adults.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article is based on data derived from the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS), which was supported by R01 AG023627-01 (Zeng Yi, principal investigator) awarded to Duke University. The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), China Natural Science Foundation, China Social Sciences Foundation, and Hong Kong Research Grants Council also provided grant support for the survey. The Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research provided support for international training. Danan Gu's work was partially supported by R01 AG023627-01 when he was at Duke University. Zeng Yi's work was supported by R01 AG023627-01. Jessica Sautter's work was supported by an NIA T32 Traineeship in the Social, Economic, and Medical Demography of Aging. An early version of this article was presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, April 17-19, 2008, New Orleans. The authors would like to thank Professor Anatoli Yashin at Duke University and two anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments.

Authors' Contributions: Danan Gu initiated and designed the study, conducted the analysis, drafted and revised the paper. Jessica Sautter assisted in drafting and revising the paper. Robin Pipkin assisted in revising the paper. Zeng Yi raised the funds for data collection.

Footnotes

A commentary on this article appears in this issue on page 575.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chiu HF, Leung T, Lam LCW, et al. Sleep problems in Chinese elderly in Hong Kong. Sleep. 1999;22:717–26. doi: 10.1093/sleep/22.6.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohayon MM, Zulley J, Guilleminault C, Smirne S, Priest RG. How age and daytime activities are related to insomnia in the general population: consequences for older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:360–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu X, Liu L. Sleep habits and insomnia in a sample of elderly persons in China. Sleep. 2005;28:1579–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoch CC, Dew MA, Reyonds CF, III, et al. Longitudinal changes in diary- and laboratory-based sleep measures in healthy “old old” and “young old” subjects: a three-year follow-up. Sleep. 1997;20:192–202. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.3.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van den Berg JF, Miedema HME, Tulen JHM, Hofman A, Knuistingh-Neven A, Tiemeier H. Sex differences in subjective and actigraphic sleep measures: a population-based study of elderly persons. Sleep. 2009;32:1367–75. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.10.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams J. Socioeconomic position and sleep quantity in UK adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:267–9. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.039552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hale L. Who has time to sleep? J Public Health. 2005;27:205–11. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdi004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel SR, Malhotra A, Gottlieb DJ, White DP, Hu FB. Correlates of long sleep duration. Sleep. 2006;29:881–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.7.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raiha I, Seppala M, Impivaara O, Hyyppa MT, Knuts LR, Sourander L. Chronic illness and subjective quality of sleep in the elderly. Aging. 1994;6:91–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03324222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts RE, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA. Prospective data on sleep complaints and associated risk factors in an older cohort. Psychosom Med. 1991;61:188–96. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199903000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blazer DG, Hays JC, Foley DJ. Sleep complaints in older adults: a racial comparison. J Gerontol. 1995;50A:M280–4. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.5.m280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore JP, Adler NE, Williams DR, Jackson JS. Socioeconomic status and health: the role of sleep. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:337–44. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200203000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jean-Louis G, Magai CM, Cohen CI, et al. Ethnic differences in self-reported sleep problems in older adults. Sleep. 2001;24:926–33. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.8.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hale L, Phuong Do D. Racial differences in self-reports of sleep duration in a population-based study. Sleep. 2007;30:1096–103. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka H, Shirakawa S. Sleep health, lifestyle and mental health in the Japanese elderly: ensuring sleep to promote a healthy brain and mind. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:465–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foley D, Ancoli-Israel S, Britz P, Walsh J. Sleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults: results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Survey. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:497–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su TP, Huang SR, Chou P. Prevalence and risk factors of insomnia in community-dwelling Chinese elderly: a Taiwanese urban area survey. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38:706–13. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lang FR, Rieckmann N, Baltes MM. Adapting to aging losses: do resources facilitate strategies of selection, compensation, and optimization in everyday functioning? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57:P501–9. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.p501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen YY, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Acevedo-Garcia D, Lee YJ. Can social factors explain sex differences in insomnia? Findings from a national survey in Taiwan. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:488–94. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.020511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bazargan M. Self-reported sleep disturbance among African-American elderly: the effects of depression, health status, exercise, and social support. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 1997;42:143–60. doi: 10.2190/GM89-NRTY-DERQ-LC7D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King AC, Oman RF, Brassington GS, Bliwise DL, Haskell WL. Moderate-intensity exercise and self-rated quality of sleep in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;277:32–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lands WEM. Alcohol, slow wave sleep, and the somatotropic axis. Alcohol. 1999;18:109–22. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(98)00073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanigawa T, Tachibana N, Yamahishi K, et al. Usual alcohol consumption and arterial oxygen desaturation during sleep. JAMA. 2004;292:923–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.923-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Briones B, Adams N, Strauss M, et al. Relationship between sleepiness and general health status. Sleep. 1996;19:583–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.7.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hays JC, Blazer DG, Foley DJ. Risk of napping: excessive daytime sleepiness and mortality in an older community population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:693–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nebes RD, Buysse EMH, Houck PR, Monk TH. Self-reported sleep quality predicts poor cognitive performance in healthy older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64B:180–7. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbn037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reid KJ, Martinovich Z, Finkel S, et al. Sleep: a marker of physical and mental health in the elderly. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:860–6. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000206164.56404.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tafaro L, Cicconetti P, Baratta A, et al. Sleep quality of centenarians: cognitive and survival implications. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2007;(Suppl. 1):385–89. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2007.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hublin C, Partinen M, Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J. Sleep and mortality: a population-based 22 year follow-up study. Sleep. 2007;30:1245–53. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.10.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kripke DF, Garfinkel L, Wingard DL, Klauber MR, Marler MR. Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:131–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamakoshi A, Ohno Y. Self-reported sleep duration as a predictor of all-cause mortality: results from the JACC study, Japan. Sleep. 2004;27:51–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCall WV. Sleep in the elderly: burden, diagnosis and treatment. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;6:9–20. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v06n0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ayas NT, White DP, Al-Delaimy WK, et al. A prospective study of self-reported sleep duration and incident diabetes in women. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:380–4. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krueger PM, Freidman EM. Sleep duration in the United States: a cross-sectional population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:1052–63. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foley DJ, Monjan AA, Brown SL, Simonsick EM, Wallace RB, Blazer DG. Sleep complaints among elderly persons: an epidemiologic study of three communities. Sleep. 1995;18:425–32. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.6.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lauderdale DS, Knutson KL, Yan LL, et al. Objectively measured sleep characteristics among early-middle-aged adults: the CARDIA Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:5–16. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohayon MM. Interactions between sleep normative data and socialcultural characteristics in the elderly. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:479–86. doi: 10.1016/j.psychores.2004.04.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gu D. The data assessment for the 2005 wave of the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey. Technological document No. 2007-01. Durham, NC, USA: Duke University; 2007. http://www.geri.duke.edu/china_study/2005_Data%20assessment%20of%20the%202005%20wave.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gu D, Dupre ME. Assessment of reliability of mortality and morbidity in the 1998-2002 CLHLS waves. In: Zeng Y, Poston DL, Vlosk DA, Gu D, editors. Healthy longevity in China: Demographic, socioeconomic, and psychological dimensions. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer Publisher; 2008. pp. 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zeng Y, Vaupel JW, Xiao Z, Zhang C, Liu Y. The healthy longevity survey and the active life expectancy of the oldest old in China. Population: An English Selection. 2001;13:95–116. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zeng Y, Gu D. Reliability of age reporting among the Chinese oldest-old in the CLHLS datasets. In: Zeng Y, Poston DL, Vlosk DA, Gu D, editors. Healthy longevity in China: demographic, socioeconomic, and psychological dimensions. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer Publisher; 2008. pp. 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coale AJ, Li S. The effect of age misreporting in China on the calculation of mortality rates at very high ages. Demography. 1991;29:293–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gu D. General data assessment of the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey in 2002. In: Zeng Y, Poston DL, Vlosk DA, Gu D, editors. Healthy longevity in China: demographic, socioeconomic, and psychological dimensions. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer Publisher; 2008. pp. 38–59. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of the patients for clinician. J Psychol Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Z. Gender differentials in cognitive impairment and decline of the oldest old in China. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61B:S107–15. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.2.s107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Winship C, Radbill L. Sampling weights and regression analysis. Sociol Methods Res. 1994;23:230–57. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hendrikx J. The impact of weights on standard errors. Presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Survey Computing, April 17, Imperial College, London, UK, 2002. [accessed on August 8, 2006]. Available at http://www.asc.org.uk/Events/Apr02/Full/Hendrickx.doc.

- 49.Driscoll HC, Serody L, Patrick S, Maurer J, Bensasi S, Houck PR, et al. Sleeping well, aging well: a descriptive and cross-sectional study of sleep in “successful agers” 75 and older. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:74–82. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181557b69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Avidan AY. Sleep and neurologic problems in the elderly. Sleep Med Clin. 2006;1:273–92. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Manber R, Armitage R. Sex, steroids, and sleep: A review. Sleep. 1999;22:540–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moe KE. Reproductive hormones, aging, and sleep. Semin Reprod Endocrinol. 1999;17:339–48. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1016243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lindberg E, Janson C, Gislason T, Bjornsson E, Hetta J, Boman G. Sleep disturbances in a young adult population: can gender differences be explained by differences in psychological status? Sleep. 1997;20:381–87. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.6.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Winkleby A, Jatulis DE, Frank E, Fortmann SP. Socioeconomic status and health: how education, income, and occupation contribute to risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:816–20. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.6.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zeng Y, Gu D, Land KC. The association of childhood socioeconomic conditions with healthy longevity at oldest-old ages in China. Demography. 2007;44:497–518. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Geroldi C, Frisoni GB, Rozzini R, De Leo D, Trabbuchi M. Principal lifetime occupation and sleep quality in the elderly. Gerontology. 1996;42:163–69. doi: 10.1159/000213788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, Vitiello MV. Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep. 2004;27:1255–73. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.7.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wingard DL, Berkman LF. Mortality risk associated with sleeping patterns among adults. Sleep. 1983;6:102–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/6.2.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wolkove N, Elkholy O, Baltzan M, Palayew M. Sleeping and aging: 1. Sleep disorders commonly found in older people. Can Med Assoc J. 2007;176:1299–1304. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wolkove N, Elkholy O, Baltzan M, Palayew M. Sleeping and aging: 2. Sleep disorders commonly found in older people. Can Med Assoc J. 2007;176:1449–54. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]