Abstract

The NF-κB family of transcription factors responds to inflammatory cytokines with rapid transcriptional activation and subsequent signal repression. Much of the system control depends on the unique characteristics of its major inhibitor, IκBα, which appears to have folding dynamics that underlie the biophysical properties of its activity. Theoretical folding studies followed by experiments have shown that a portion of the ankyrin repeat domain of IκBα folds on binding. In resting cells, IκBα is constantly being synthesized but most of it is rapidly degraded leaving only a very small pool of free IκBα. Nearly all of the NF-κB is bound to IκBα resulting in near complete inhibition of nuclear localization and transcriptional activation. Combined solution biophysical measurements and quantitative protein half-life measurements inside cells have allowed us to understand how the inhibition occurs, why IκBα can be degraded quickly in the free state but remain extremely stable in the bound state, and how signal activation and repression can be tuned by IκB folding dynamics. This review summarizes results of in vitro and in vivo experiments that converge demonstrating the effective interplay between biophysics and cell biology in understanding transcriptional control by the NF-κB signaling module.

The NF-κB signaling system is an ubiquitous immediate early response network that transduces extra-cellular signals from a variety of receptors, integrates the information of the physiological state, and regulates patterns of gene expression. This ‘signaling module’ (1) has been implicated in a variety of cellular functions such as cell growth, proliferation, apoptosis, and stress responses and is missregulated in numerous diseases (2, 3). The system is named after the Nuclear-Factor κB (NF-κB) which was originally discovered as a transcription factor present in activated B-cells that strongly activates the immunoglobulin kappa-chain gene expression (4). In vertebrates, NF-κB connotes not a single protein but a family of polypeptides that form a combinatorial number of homo- and heterodimers of p65 (RelA), RelB, c-Rel, p50, and p52 subunits (2). Several inhibitors of NF-κB activity have been identified and named as Inhibitors-of-kappaB (IκB) including isoforms IκBα, IκBβ, and IκBε, which block the nuclear localization and transcriptional activity of p65 and c-Rel-containing NF-κB dimers (5) and the newest member of the family, IκBδ (6). In resting cells, most of the estimated 100,000 NF-κB dimers are bound to IκBs, keeping the NF-κB pool mainly in the cytoplasm by inhibiting its nuclear localization and association with DNA (7, 8). A variety of extracellular signals, including viral antigens and lipopolysaccharides, as well as several physiological cytokines activate extracellular receptors that initiate the assembly of the IκB kinase (IKK), which in turn phosphorylates the N-terminal signal response domain of NF-κB-bound IκBα, leading to subsequent ubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome (9). NF-κB dimers then translocate to the nucleus, bind DNA, and regulate transcription of numerous target genes (10). The large number of genes that are activated by NF-κBs show widely varying transcritption levels, activation kinetics, and post-induction repression. The mechanism of this diversity is only beginning to be understood (11, 12). Among the strongly activated genes is the one coding for IκBα (13–15). Newly synthesized IκBα translocates to the nucleus and binds to NF-κB, and the complex is exported from the nucleus (Figure 1) (1, 16). According to this model, the NF-κB transcriptional activity can be brought back to baseline by a deceptively simple negative feedback loop. However, puzzling questions arise regarding how robustness and specificity are achieved in a cellular response system that is activated by many different ligands and subsequently activates hundreds of different genes. In addition, the time dependence of the NF-κB activity functionally relevant in that it rises and falls rapidly and may display dampened oscillations (1). Quantitative models of cell signaling have recently opened new approaches to our understanding of the temporal control of the NF-κB signal response (1). Ordinary differential equation (ODE) flux models of this system suggest that the rates at which such a simple feedback mechanism functions depends critically on the concentrations of species, in this case NF-κB and IκBα, and the rates at which they are produced and degraded (17, 18). These studies demonstrated that the synthesis and degradation rates of IκBα are critical parameters that control the signaling by the entire NF-κB signaling module. Degradation of free IκBα, which occurs by a ubiquitin-independent but proteasome dependent fashion, is extremely rapid so that the intracellular half-life is less than 10 min. On the other hand, NF-κB-bound IκBα is incredibly stable, with an intracellular half-life of many hours. Once bound to NF-κB, IκBα is only degraded if it is first phosphorylated, then ubiquitinated, and finally degraded by the proteasome in a ubiquitin-dependent fashion. What are the biochemical and biophysical origins of such a switch in degradation mechanism, and how can such a rapid signal response be initiated and subsequently repressed? The goal of this review is to illustrate that it is possible to assign reliable rates from biochemical and biophysical experiments to the apparent rate constants in the ODE model and that such an iterative process can give new insights about the behavior of the signaling module.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the NF-κB signaling pathway. The figure places emphasis on the role of IκBα, showing the different degradation pathways and transcriptional activation of new IκBα synthesis. The newly synthesized IκBα is either degraded, binds to an NF-κB in the cytoplasm, or enters the nucleus and binds nuclear NF-κB. This feedback part of the pathway is indicated by red arrows.

FOLDING DYNAMICS OF IκBα

The domain structure of IκBα

The full-length IκBα protein is composed of three major regions; an N-terminal signal response region of ~70 amino acids, where phosphorylation and ubiquitination occur, an ankyrin repeat domain (ARD) of ~220 amino acids, and a C-terminal PEST sequence that extends from residues 275-317 (Figure 2A) (19, 20). Sequence analyses predict intrinsic disorder in both the N-terminal domain and the PEST region of IκBα as well as in a good portion of the ARD (Figure 2B) (21). The N-terminal domain receives the phosphorylation and ubiquitinylation signals and targets the protein to the proteasome for degradation (9), and has no measureable effect on binding of IκBα to NF-κB (22). The binding activity can be localized to the ARD and PEST regions, for which high resolution crystal structures were obtained only when in complex with NF-κB, and show that the ARD can fold as a typical elongated stack of six AR (Figure 2C). IκBα has resisted all attempts to crystallize it in the unbound state, and its biophysical behavior is consistent with a native state that does not adopt a unique compact fold (23).

Figure 2.

(A) Schematic diagram of NF-κB(p65) one of the most abundant NF-κB family members in the cell and of IκBα, the key member of the inhibitor family. (B) PONDR (21) analysis of the intrinsic disorder in the ankyrin repeat domain of IκBα. (C) LEFT: The crystal structure of IκBα (blue) bound to NF-κB (p50, green; p65, red) (19). RIGHT: The crystal structure of NF-κB (p50, green; p65, red) bound to κB site DNA (gold) (46). (Figure prepared using PyMOL (64)).

Theoretical models of folding of IκBα

ARDs are a very common protein-protein interaction motif that adopt an elongated fold in which the ankyrin repeats (ARs) stack against each other in a linear fashion by folding into two antiparallel α-helices connected by a short loop, followed by a β-hairpin that protrudes away from the helical stack (Figure 2C). This non-globular fold is stabilized by both intra and inter-repeat interactions and the general folding properties can be successfully modeled with simple near-neighbor interaction schemes (24, 25). Theoretical folding studies using native topology-based models (26) (Figure 3A) and experiments (24, 27–29) show that for natural ARDs composed of few ARs, the equilibrium folding mechanism shows a sharp transition in which once initial nucleation has occurred, the rest of the ARs fold in a highly cooperative fashion. Only the fully unfolded and fully folded species are significantly populated at equilibrium (reviewed in Barrick et al., 2008 (30)). However, subtle variations in the interactions between modules may result in decoupling of the folding elements, giving rise to more complicated folding scenarios where partially folded intermediates and multiple folding routes can be detected (31).

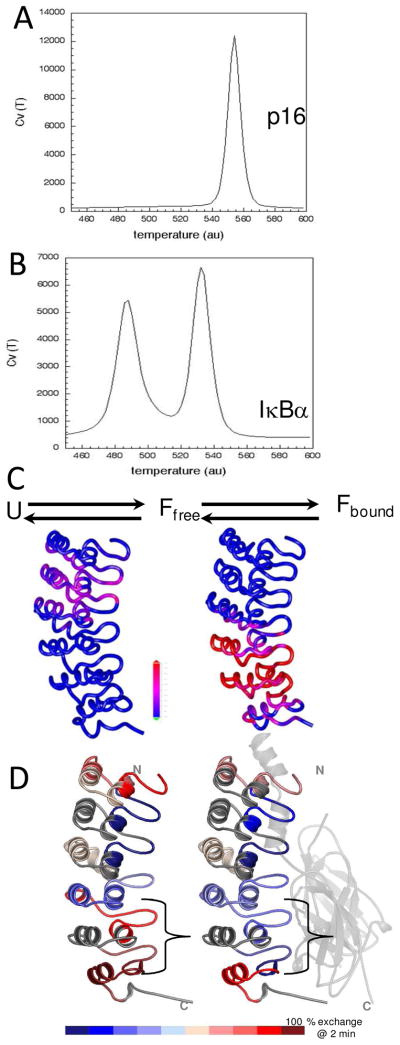

Figure 3.

(A) Folding simulations of p16, an example ankyrin repeat protein. The folding of p16 was simulated with energetically unfrustrated models. The heat capacity as a function of temperature derived from several constant temperature runs is plotted. The peak in the plot corresponds to the folding temperature (Tf). (B) Similar analysis as in (A) for the ankyrin repeat domains of IκBα (residues 67-287). (C) Probability of contact formation during folding simulations of IκBα(67–287) at the first Tf (LEFT) and at the second Tf (RIGHT). The probability is plotted on a color scale with the most probable colored red. (D) Results from amide H/D exchange experiments on IκBα free in solution (LEFT) and when bound to NF-κB (RIGHT). The amount of exchange was measured after 2 min exposure to deuterated buffer followed by pepsin digestion and mass spectrometry. The extent of exchange is plotted on a color scale with the most exchanged colored red.

In the case of IκBα, native topology-based models using the structure of IκBα taken from the structure in complex with NF-κB predict that two separate folding events are necessary to attain complete folding, each encompassing the folding of roughly three consecutive ARs. The folding nucleates around AR2 and AR3 and propagates outward to include AR1 and AR4. Folding of AR5 and AR6 is predicted to occur in a second folding transition (Figure 3C). Thus, the ARD of IκBα behaves more like larger ARDs, which have been shown both by theory and experiment to allow for “cracks” to occur and folding sub-domains to emerge (32, 33).

IκBα deviates from the consensus sequence for stable ARs

Bioinformatic analysis of the hundreds of AR sequences has resulted in several attempts to define a consensus sequence for the AR (34–39). Full-consensus ARDs have been constructed and these show much higher thermal and chemical stability as well as faster folding rates than naturally occurring ARDs of similar size (36–38, 40–42). Approximately 50% of the IκBα sequence conforms to the minimum consensus and is marginally stable (Figure 4B).

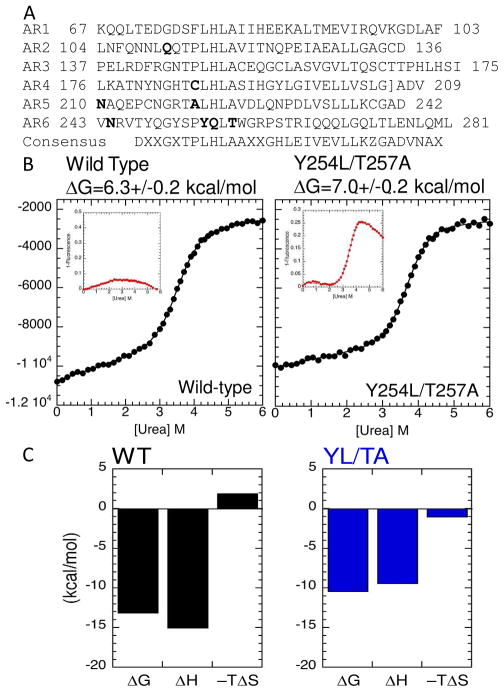

Figure 4.

(A) Sequence of IκBα showing locations of some of the substitutions that stabilize the protein. (B) Equilibrium unfolding experiments with wild type (LEFT) and Y254L, T257A mutant IκBα. The insets show the change in fluorescence of W258, a naturally-occurring Trp in AR6. In the wild type protein, this residue does not change fluorescence appreciably with denaturant, however in the stabilized mutant, its fluorescence changes in a manner similar to the CD signal indicating it follows the major cooperative folding transition of the protein. (C) Plots of the thermodynamic parameters of binding of wild type (LEFT) and Y254L, T257A mutant (RIGHT) forms of IκBα to NF-κB(p50248–350/p65190–321) determined by ITC.

Like many proteins with weakly-folded parts, IκBα is prone to aggregation when isolated, even at physiological temperatures (23). Although this feature precludes any strict quantification of its thermal denaturation, IκBα can be reversibly denatured by chemical denaturants and its folding properties analyzed in detail (43). Upon denaturant challenge, the equilibrium folding behavior of the IκBα ARD (residues 67-287) shows two transitions; a minor non-cooperative conversion upon subtle perturbation, and a major cooperative folding event. By introducing Trp residues as spectroscopic probes at several positions, the non-cooperative conversion was mapped to AR5 and AR6 (43). The single native Trp at position 258 in AR6 does not follow a cooperative transition in the wild type protein. However, introduction of two consensus residues (Y254L, T257A) stabilizes AR6 such that Trp 258 then follows the cooperative unfolding transition of the whole ARD (Figure 4B) (44). Based on the consensus design principles, a library of mutants with varying properties of folding and stability can be engineered and quantitatively studied. If the folding properties are conserved in the cellular mellieu, these can be used as a molecular toolbox to perturb elementary parameters of the signaling network.

IκBα FOLDING IS COUPLED TO NF-κB BINDING

Evidence of folding upon binding from H/D exchange

Native state amide H/D exchange experiments followed by mass spectrometry recapitulated the theoretical results for IκBα folding transitions (Figure 3D). The β-hairpins of AR2 and AR3 were remarkably resistant to exchange, whereas AR5 and AR6 exchanged completely within the first minute in free IκBα. When bound to NF-κB, the β-hairpins of AR5 and AR6 showed dramatically less exchange in the bound state (Figure 3D) (45). The decrease in the number of exchanging amides could not be accounted for just by interface protection suggesting that IκBα undergoes a folding transition upon binding.

Structure and energetics of IκBα•NF-κB complex formation

From the primary sequence viewpoint, NF-κB and IκBα bind in a head-to-tail fashion with the N-terminal domain of NF-κB near the C-terminal PEST sequence of IκBα (19, 20). The Rel-homology domain (RHD) of NF-κBs specifically bind both DNA and IκBs. Crystal structures of DNA-bound NF-κB(p50/p65) and IκBα-bound NF-κB(p50/p65) show overlapping but non-identical binding surfaces (19, 20, 46, 47) (Figure 2C and D). DNA contacts the loops protruding from the dimerization and N-terminal domains of the RHD and the linker between them whereas IκBα contacts mainly the dimerization domain and helix3-NLS-helix4 at the C-terminus of the RHD of p65 (compare Figure 2C and D). How is binding energy distributed in this complex macromolecular assembly?

The protein-protein interface that forms between NF-κB and IκBα is large, having some 4000 Å2 of buried surface area, yet mutations of interface residues had little affect on the binding free energy (Figure 4C) (48). Instead, all of the binding energy is attributable to interactions occurring at the two ends of the complex. At the very C-terminal end of the RHD is the nuclear localization signal (NLS polypeptide), which connects the dimerization domain to the transactivation domain in the full length NF-κB(p65) protein (Figure 2C). The KRKR sequence, which constitutes the minimal NLS, is in between two helical segments in the structure of IκBα-bound NF-κB (19). Deletion of the last part of this region of NF-κB, helix 4 (residues 305-321), reduces IκBα binding affinity by 7.8 kcal/mol (8). Theoretical studies of the binding of the NLS polypeptide (residues 291-325) of NF-κB(p65) to IκBα suggested that this segment of NF-κB folds on binding to IκBα (53). NMR experiments also show large chemical shift changes upon binding consistent with the transition from mainly random coil to a helical fold (Cervantes et al., in preparation). It has been experimentally observed that this segment binds with a 1μM KD to IκBα, and with a large ΔCP,obs for IκBα binding to this NLS segment (−1.30 ± 0.03 kcal mol−1 K−1) that could not be accounted for by burial of polar and non polar surface area calculations derived from the crystal structures (49–51). Thus, the thermodynamic signatures of the binding interaction cannot be accounted for by merely docking the individucal static structures, and larger structural rearrangements must be implicated, as is often observed for protein-DNA interactions (52). Thus, the “head” of IκBα (ARs 1–3) appears to be folded based on H/D exchange experiments, and the “tail” of NF-κB (the NLS polypeptide) folds upon binding to it.

At the other end of the IκBα ARD, deletion of the PEST sequence (residues 276-287) reduces the NF-κB binding by some 5 kcal/mol (54). Taken together, the binding affinity losses due to deletion at the ends of the interface are more than enough to account for the entire binding energy of complex formation. Interestingly, the PEST region does not become completely ordered upon binding to NF-κB according to high resolution NMR spectroscopy data (55). The native state of the NF-κB•IκBα complex thus retains regions with highly dynamic character. Given that AR5 and AR6 at one end of the interface and the NLS at the other end of the interface both fold on binding, the folding energy landscape of both proteins must be taken into account in analyzing the binding event.

Alteration of binding thermodynamics by stabilizing mutations

It is important to emphasize that AR5–6 of IκBα in the free state are not random coil or completely unfolded. Indeed, even though the amides in these two repeats completely exchange within one minute, no new secondary structure forms when IκBα binds to NF-κB (23). Thus, the AR5–6 region must be partially folded, perhaps molten-globular in the free state. Further evidence for the partially folded state of AR5–6 comes from studies on the thermodynamics of binding of wild type and mutant forms of IκBα.

The aforementioned Y254L, T257A mutant showed a markedly changed equilibrium folding profile compared to wild type IκBα (Figure 4B). Indeed, one can conclude that AR5 and AR6 now form part of the cooperatively unfolding ARD. Binding thermodynamics of this locally stabilized mutant IκBα compared to the wild type allowed us to speculate about how the very tight binding affinity of IκBα for NF-κB is achieved. The unfavorable entropy change upon binding of wild type IκBα is smaller than would be expected if the residues in AR5 and AR6 (some 80 amino acids) of IκBα were undergoing a transition from completely unfolded to completely folded (Figure 4C). To a first approximation, if folding is coupled to binding, stabilizing a weakly folded protein should strengthen binding as the unfavorable folding entropy should be decreased. The stabilized mutant did, indeed, have a less unfavorable entropy change upon binding but the effect was only about 2 kcal/mol. Surprisingly, the binding affinity of the stabilized mutant IκBα to NF-κB was weakened some 30-fold, due to much less favorable enthalpy change upon binding (Figure 4C). Our interpretation of this result is that if the free IκBα is molten globular, it has already paid most of the entropy cost of folding (and gained most of the favorable entropy from the hydrophobic effect), but has not completely attained the favorable enthalpy of the folded state. An alternative interpretation is that the stabilized mutant can not structurally adapt to access the conformation required for optimal binding of NF-κB.

Possible entropy compensation upon binding

Even with the model just described, it is still surprising that the entropy cost upon binding is so small considering one-third of IκBα is weakly folded when free in solution (45). A possible explanation is that some other part of the ARD becomes more dynamic upon binding and compensates for the entropy cost of folding AR5 and AR6. NMR backbone dynamics experiments revealed that some entropy compensation of this type may be occurring. Surprisingly, although AR2 and AR3 are the most well-folded, a large number of the resonances in AR3 that are observed in the NMR spectrum of free IκBα(67–206) are actually not observed in the NMR spectrum of IκBα(67–287) in complex with NF-κB (56). When amide cross peaks are not visible in the NMR spectrum, this is usually evidence of intermediate exchange on the NMR time scale, a phenomenon indicative of μsec-msec dynamics. Given the sub-nanomolar binding affinity of the NF-κB•IκBα complex, these dynamics must be regarded as an increase in backbone dynamics within the complex and not a result of an association-dissociation process. Such an increase in dynamics suggests a re-distribution of disorder so that the loss of entropy in ARs5 and AR6 may be compensated for by an increase in AR3. Backbone relaxation measurements and analysis of long-timescale dynamics from residual dipolar coupling experiments on the free IκBα(67–206) revealed that although AR3 is in the core of the “folded” part of IκBα, parts of this AR are more dynamic than the other ARs even in the free state (57).

IκBα FOLDING DETERMINES ITS INTRACELLULAR HALF-LIFE

Distinct degradation pathways for IκBα

It is generally believed, (although not thoroughly tested) that, in the absence of active mechanisms of degradation, the more thermodynamically stable a protein is, the longer its in vivo half-life will be. Consistent with this notion, free IκBα, which is marginally stable (23), has a very short intracellular half-life of less than 10 minutes (17, 58). This rapid degradation rate depends in part on the presence of the C-terminal PEST sequence (18, 59, 60). The degradation of the free protein appears to be independent of ubiquitinylation, since all of the Lys residues in IκBα can be mutated without changing the degradation rate of the free protein (18). In addition, although free IκBα can be phosphorylated and ubiquitinylated, its degradation rate is not different in IKK−/− cells indicating that ubiquitin-independent degradation is the primary route for free IκBα (17). The Y254L, T257A mutant IκBα is degraded more slowly than wild-type IκBα both in vitro by the 20S proteasome and in vivo suggesting that in addition to the PEST sequence, the weakly-folded AR6 of IκBα is important for rapid ubiquitin-independent degradation (Figure 5B, C) (44).

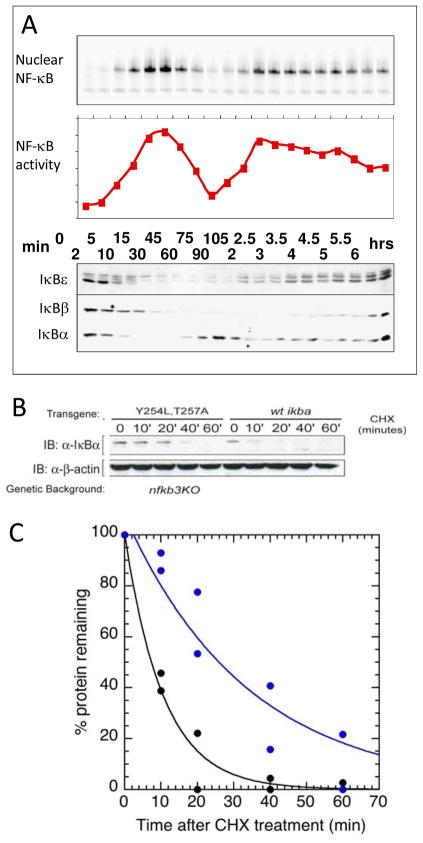

Figure 5.

(A) NF-κB transcription activity was measured as a function of time after stimulation with tumor necrosis factor. Proteins were also measured by quantitative western blotting. TOP: NF-κB(p65, BOTTOM: IκB isoforms. (B) Quantitative Western blot showing the levels of IκBα(Y254L, T257A) and wild-type after cyclohexamide treatment in NF-κB −/− cells.

When IκBα is bound to NF-κB, they form a very stable complex that requires ubiquitinylation for degradation by the Ub-dependent degradation pathway that uses the ATPases of the 26S subunit to unfold and subsequently degrade the protein. Our studies showing that the binding affinity for the NF-κB-bound IκBα is concentrated in two regions at the ends of the interface suggest a mechanism for proteasome degradation of the NF-κB-bound IκBα. If proteasome digestion starts near the N-terminal ubiquitinylated residues of IκBα, and proceeds to AR1, this would disrupt the interaction between AR1 and the NLS polypeptide (residues 305-325 of NF-κB(p65)). We know from deletion studies that the interaction between the NLS polypeptide and AR1 is worth some 8000-fold in binding affinity, and disruption of this interaction causes the NF-κB to rapidly dissociate (8).

Intracellular half-life of IκBα is a critical parameter for signaling control

An ordinary differential equation (ODE) model of the NF-κB signaling system has been constructed that recapitulates the interesting oscillatory behavior of the NF-κB transcription activity (Figure 5A) (1). Such ODE models are informative because one can test them for sensitivity of each of the parameters to computationally dissect the system’s behavior. In the case of NF-κB signaling, one of the most sensitive parameters for control of the constitutive transcriptional activity is the intracellular half-life of IκBα (17). Recent re-parameterization of this model shows that when the binding rates and affinities measured in vitro by SPR are used as fixed parameters, the model recapitulates the rates and amplitudes of the NF-κB response. SPR experiments revealed the extremely slow dissociation rate of the IκBα•NF-κB complex, consistent with the long intracellular half-life of the complex, which is completely stable in the absence of IκB kinase (IKK) phosphorylation and subsequent ubiquitinylation (>12 hrs). Thus, IκBα “foldedness” I, controlled by binding to NF-κB, allows it to switch between degradation mechanisms (18).

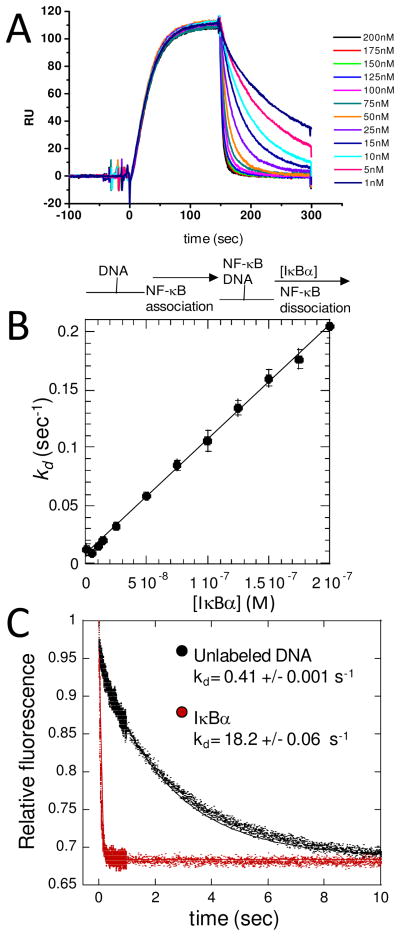

RAPID TRANSCRIPTION REPRESSION REQUIRES PARTIALLY FOLDED IκBα

A key feature of the NF-κB negative feedback is the rapidity with which the transcriptional activation is subsequently repressed (Figure 5A) (1). The rapid post-induction repression is partly explained by the fact that the gene for IκBα is strongly induced by NF-κB, so activation of NF-κB immediately produces newly synthesized IκBα. However, the new IκBα must still escape proteasome degradation, enter the nucleus, and compete for binding to NF-κB with the very large number of κB sites in the DNA. We recently discovered an intriguing kinetic phenomenon in which IκBα is able to markedly increase the rate of dissociation of NF-κB from the DNA (61). The phenomenon was initially discovered by flowing nanomolar concentrations of IκBα over the NF-κB•DNA complex in a co-injection step in an SPR experiment (Figure 6A). IκBα is remarkably efficient at increasing the dissociation rate (kd) of NF-κB from the DNA; the apparent second order rate constant for the IκBα-mediated dissociation is 106 M−1 s−1 (Figure 6B). Similar experiments were also performed using stopped-flow fluorescence the same phenomenon was observed under solution conditions (Figure 6C). Several mutant forms of IκBα were also tested for their ability to mediate dissociation of NF-κB from the DNA. The mutations had a variety of effects on NF-κB binding, from none to a decrease of some 100-fold. However, all of the thermodynamically stabilized mutants, even the ones that bound with the same affinity, were less able to mediate dissociation of NF-κB from the DNA (61). Thus, an important function of the “weakly-folded” part of IκBα may be to facilitate dissociation of NF-κB from the DNA to rapidly repress post-induction transcriptional activation.

Figure 6.

(A) Real-time binding and dissociation experiment monitored by SPR. Biotinylated κB-site DNA was bound to the streptavidin chip (t=0). NF-κB(p50(19–363)/p65(1–325)) was allowed to associate with the DNA until a pseudo-flowing equilibrium was reached (t=100 sec). Varying concentrations of IκBα were then injected through the second sample loop (co-inject experiment) and the dissociation rate constant (kd) was measured. A schematic of the binding events is shown below the graph. (B) Plot of the kd determined from experiments like that shown in (A) as a function of IκBα concentration. The error bars represent four independent experiments. The slope of the line is the pseudo-second order rate constant for IκBα-mediated dissociation, and its value of 106 M−1 s−1 indicates that IκBα-mediated active dissociation is a very efficient process. (C) Dissociation was also monitored by stopped-flow fluorimetry using a pyrene-labeled DNA hairpin. Stopped-flow fluorescence experiment in which pyrene-labeled hairpin DNA (0.25 μM) complexed to NF-κB(p50(19–363)/p65(1–325)) (0.5 μM) in syringe 1 was rapidly mixed with a 50-fold excess (relative to NF-κB) of either unlabeled hairpin DNA (black curve, kd = 0.41 s−1) or IκBα (red curve, kd = 18.2 s−1).

CONCLUDING REMARKS AND PERSPECTIVES

Although the NF-κB signaling module comprises only a small portion of the entire cellular signaling network, it has intriguing complexities. The importance of biochemical and biophysical experiments that seek a quantitative understanding of such signaling modules can not be underestimated. If we are to build up a quantitative and robust description of cellular signaling, the interplay between rigorous biophysical measurements and cell biological experiments as well as comprehensive mathematical models that reveal the emerging properties of the system will all be essential (62, 63). Protein-protein interactions play a fundamental role in intracellular signaling, but simple models that assume equilibrium binding under cellular conditions will not suffice. Signaling networks depend upon protein-protein interactions that can be under kinetic as well as thermodynamic control. We have shown that the structural and dynamic features of IκBα, in particular, its foldedness, is exploited to provide kinetic control of dynamic regulatory processes, including its degradation through Ub-dependent and independent pathways and competition with DNA for NF-κB.

When quantitative in vitro experiments can be racapitulated in cellular models, emergent properties of the cellular control can be discovered. For example, the observation of a kinetic control mechanism in the NF-κB signaling module raises the possibility that when the model is more complete. The number of newly synthesized IκBα molecules that enter the nucleus during post-induction repression may be very low, and single molecules may be able to remove NF-κB from transcription sites requiring inclusion of stochastic processes in addition to the equilibrium flux equations to accurately model the entire system. The iteration between biophysical experiments and measurement of cellular properties will be critical for such a further model refinement. The converse is also true in the sense that when a protein is involved in a highly regulated cellular system, it is more likely that its interactions will be tuned to respond rapidly to changes in the regulatory state, and will most likely not display simple kinetics or thermodynamics of binding.

Abbreviations

- IκB

inhibitor of kappa B proteins

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa B

- AR

ankyrin repeat

- ARD

ankyrin repeat domain

References

- 1.Hoffmann A, Levchenko A, Scott ML, Baltimore D. The IkappaB-NF-kappaB signaling module: temporal control and selective gene activation. Science. 2002;298:1241–1245. doi: 10.1126/science.1071914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghosh S, May MJ, Kopp EB. NF-kappa B and Rel proteins: evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:225–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar A, Takada Y, Boriek AM, Aggarwal BB. Nuclear factor-kappaB: its role in health and disease. J Mol Med. 2004;82:434–448. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0555-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffmann A, Baltimore D. Circuitry of nuclear factor kappaB signaling. Immunol Rev. 2006;210:171–186. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verma IM, Stevenson JK, Schwarz EM, Van Antwerp D, Miyamoto S. Rel/NF-kappa B/I kappa B family: intimate tales of association and dissociation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2723–2735. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basak S, Kim H, Kearns JD, Tergaonkar V, O’Dea E, Werner SL, Benedict CA, Ware CF, Ghosh G, Verma IM, Hoffmann A. A fourth IkappaB protein within the NF-kappaB signaling module. Cell. 2007;128:369–381. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baeuerle PA. IkB-NF-kB structures: at the interface of inflammation control. Cell. 1998;95:729–731. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81694-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergqvist S, Croy CH, Kjaergaard M, Huxford T, Ghosh G, Komives EA. Thermodynamics reveal that helix four in the NLS of NF-kappaB p65 anchors IkappaBalpha, forming a very stable complex. J Mol Biol. 2006;360:421–434. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Traenckner EB, Baeuerle PA. Appearance of apparently ubiquitin-conjugated I kappa B-alpha during its phosphorylation-induced degradation in intact cells. J Cell Sci Suppl. 1995;19:79–84. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1995.supplement_19.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pahl HL. Activators and target genes of Rel/NF-kappaB transcription factors. Oncogene. 1999;18:6853–6866. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffmann A, Leung TH, Baltimore D. Genetic analysis of NF-kappaB/Rel transcription factors defines functional specificities. EMBO J. 2003;22:5530–5539. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Werner SL, Barken D, Hoffmann A. Stimulus specificity of gene expression programs determined by temporal control of IKK activity. Science. 2005;309:1857–1861. doi: 10.1126/science.1113319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown K, Park S, Kanno T, Franzoso G, Siebenlist U. Mutual regulation of the transcriptional activator NF-kappa B and its inhibitor, I kappa B-alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2532–2536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott ML, Fujita T, Liou HC, Nolan GP, Baltimore D. The p65 subunit of NF-kappa B regulates I kappa B by two distinct mechanisms. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1266–1276. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7a.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun SC, Ganchi PA, Ballard DW, Greene WC. NF-kappa B controls expression of inhibitor I kappa B alpha: evidence for an inducible autoregulatory pathway. Science. 1993;259:1912–1915. doi: 10.1126/science.8096091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Turpin P, Rodriguez M, Thomas D, THR, Virelizier JL, Dargemont C. Nuclear localization of IkBa promotes active transport of NF-kB from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:369–378. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Dea EL, Barken D, Peralta RQ, Tran KT, Werner SL, Kearns JD, Levchenko A, Hoffmann A. A homeostatic model of IkappaB metabolism to control constitutive NF-kappaB activity. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:111. doi: 10.1038/msb4100148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathes E, O’Dea EL, Hoffmann A, Ghosh G. NF-kappaB dictates the degradation pathway of IkappaBalpha. EMBO J. 2008;27:1357–1367. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobs MD, Harrison SC. Structure of an IkappaBalpha/NF-kappaB complex. Cell. 1998;95:749–758. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81698-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huxford T, Huang DB, Malek S, Ghosh G. The crystal structure of the IkappaBalpha/NF-kappaB complex reveals mechanisms of NF-kappaB inactivation. Cell. 1998;95:759–770. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81699-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garner E, Romero P, Dunker AK, Brown C, Obradovic Z. Predicting Binding Regions within Disordered Proteins. Genome Informatics. 1999;10:41–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huxford T, Malek S, Ghosh G. Structure and mechanism in NF-kappa B/I kappa B signaling. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1999;64:533–540. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1999.64.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Croy CH, Bergqvist S, Huxford T, Ghosh G, Komives EA. Biophysical characterization of the free IkappaBalpha ankyrin repeat domain in solution. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1767–1777. doi: 10.1110/ps.04731004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mello CC, Barrick D. An experimentally determined protein folding energy landscape. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:14102–14107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403386101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferreiro DU, Walczak AM, Komives EA, Wolynes PG. The energy landscapes of repeat-containing proteins: topology, cooperativity, and the folding funnels of one-dimensional architectures. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;16:e1000070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferreiro DU, Cho SS, Komives EA, Wolynes PG. The energy landscape of modular repeat proteins: topology determines folding mechanism in the ankyrin family. J Mol Biol. 2005;354:679–692. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang KS, Guralnick BJ, Wang WK, Fersht AR, Itzhaki LS. Stability and folding of the tumour suppressor protein p16. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:1869–1886. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zweifel ME, Barrick D. Studies of the ankyrin repeats of the Drosophila melanogaster Notch receptor. 2 Solution stability and cooperativity of unfolding. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14357–14367. doi: 10.1021/bi011436+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeeb M, Rosner H, Zeslawski W, Canet D, Holak TA, Balbach J. Protein Folding and Stability of Human CDK Inhibitor p19INK4d. J Mol Biol. 2002;315:447–457. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barrick D, Ferreiro DU, Komives EA. Folding landscapes of ankyrin repeat proteins: experiments meet theory. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lowe AR, Itzhaki LS. Rational redesign of the folding pathway of a modular protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2679–2684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604653104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Löw C, Weininger U, Zeeb M, Zhang W, Laue ED, Schmid FX, Balbach J. Folding Mechanism of an Ankyrin Repeat Protein: Scaffold and Active Site Formation of Human CDK Inhibitor p19INK4d. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:219–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Werbeck ND, Itzhaki LS. Probing a moving target with a plastic unfolding intermediate of an ankyrin repeat protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:7863–7868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610315104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michaely P, Bennett V. The ANK repeat: a ubiquitous motif involved in macromolecular recognition. Trends in cell biology. 1992;2:127–129. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(92)90084-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sedgwick SG, Smerdon SJ. The ankyrin repeat: a diversity of interactions on a common structural framework. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:311–316. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01426-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mosavi LK, Minor DL, Jr, Peng ZY. Consensus-derived structural determinants of the ankyrin repeat motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16029–16034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252537899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Binz HK, Stumpp MT, Forrer P, Amstutz P, Pluckthun A. Designing repeat proteins: well-expressed, soluble and stable proteins from combinatorial libraries of consensus ankyrin repeat proteins. J Mol Biol. 2003;332:489–503. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00896-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kohl A, Binz HK, Forrer P, Stumpp MT, Pluckthun A, Grutter MG. Designed to be stable: crystal structure of a consensus ankyrin repeat protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1700–1705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337680100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tripp KW, Barrick D. Enhancing the stability and folding rate of a repeat protein through the addition of consensus repeats. J Mol Biol. 2007;365:1187–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Devi VS, Binz HK, Stumpp MT, Pluckthun A, Bosshard HR, Jelesarov I. Folding of a designed simple ankyrin repeat protein. Protein Sci. 2004;13:2864–2870. doi: 10.1110/ps.04935704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Interlandi G, Wetzel SK, Settanni G, Pluckthun A, Caflisch A. Characterization and further stabilization of designed ankyrin repeat proteins by combining molecular dynamics simulations and experiments. J Mol Biol. 2008;375:837–854. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wetzel SK, Settanni G, Kenig M, Binz HK, Pluckthun A. Folding and unfolding mechanism of highly stable full-consensus ankyrin repeat proteins. J Mol Biol. 2008;376:241–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferreiro DU, Cervantes CF, Truhlar SM, Cho SS, Wolynes PG, Komives EA. Stabilizing IkappaBalpha by “consensus” design. J Mol Biol. 2007;365:1201–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Truhlar SME, Mathes E, Cervantes CF, Ghosh G, Komives EA. Pre-folding IkappaBalpha alters control of NF-kappaB signaling. J Mol Biol. 2008;380:67–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.02.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Truhlar SM, Torpey JW, Komives EA. Regions of IkappaBalpha that are critical for its inhibition of NF-kappaB. DNA interaction fold upon binding to NF-kappaB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18951–18956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605794103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen FE, Huang DB, Chen YQ, Ghosh G. Crystal structure of p50/p65 heterodimer of transcription factor NF-kappaB bound to DNA. Nature. 1998;391:410–413. doi: 10.1038/34956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Müller CW, Rey FA, Sodeoka M, Verdine GL, Harrison SC. Structure of the NF-kappa B p50 homodimer bound to DNA. Nature. 1995;373:311–317. doi: 10.1038/373311a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huxford T, Mishler D, Phelps CB, Huang DB, Sengchanthalangsy LL, Reeves R, Hughes CA, Komives EA, Ghosh G. Solvent exposed non-contacting amino acids play a critical role in NF-kappaB/IkappaBalpha complex formation. J Mol Biol. 2002;324:587–597. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ha JH, Spolar RS, Record MT. Role of the Hydrophobic Effect in Stability of Site-Specific Protein-DNA Complexes. J Mol Biol. 1989;209:801–816. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90608-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Livingstone JR, Spolar RS, Record MT. Contribution to the Thermodynamics of Protein Folding from the Reduction in Water-Accessible Nonpolar Surface-Area. Biochemistry-Us. 1991;30:4237–4244. doi: 10.1021/bi00231a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spolar RS, Livingstone JR, Record MT. Use of Liquid-Hydrocarbon and Amide Transfer Data to Estimate Contributions to Thermodynamic Functions of Protein Folding from the Removal of Nonpolar and Polar Surface from Water. Biochemistry-Us. 1992;31:3947–3955. doi: 10.1021/bi00131a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spolar RS, Record JMT. Coupling of Local Folding to Site-Specific Binding of Proteins to DNA. Science. 1994;263:777–784. doi: 10.1126/science.8303294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Latzer J, Papoian GA, Prentiss MC, Komives EA, Wolynes PG. Induced fit, folding, and recognition of the NF-kappaB-nuclear localization signals by IkappaBalpha and IkappaBbeta. J Mol Biol. 2007;367:262–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bergqvist S, Ghosh G, Komives EA. The IkBa/NF-kB complex has two hot-spots, one at either end of the interface. Prot Sci. 2008;17:2051–2058. doi: 10.1110/ps.037481.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sue SC, Dyson HJ. Interaction of the IkappaBalpha C-terminal PEST sequence with NF-kappaB: insights into the inhibition of NF-kappaB DNA binding by IkappaBalpha. J Mol Biol. 2009;388:824–838. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sue SC, Cervantes C, Komives EA, Dyson HJ. Transfer of Flexibility between Ankyrin Repeats in IkappaBalpha upon Formation of the NF-kappaB Complex. J Mol Biol. 2008;380:917–931. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cervantes CF, Markwick PRL, Sue SC, McCammon JA, Dyson HJ, Komives EA. Functional dynamics of the folded ankyrin repeats of IkappaB alpha revealed by nuclear magnetic resonance. Biochemistry. 2009;48:8023–8031. doi: 10.1021/bi900712r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rogers S, Wells R, Rechsteiner M. Amino acid sequences common to rapidly degraded proteins: the PEST hypothesis. Science. 1986;234:364–368. doi: 10.1126/science.2876518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rice NR, Ernst MK. In vivo control of NF-kappa-B activation by I-kappa-B-alpha. EMBO J. 1993;12:4685–4695. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06157.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pando MP, Verma IM. Signal-dependent and -independent degradation of free and NF-kappa B bound IkappaBalpha. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21278–21286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002532200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bergqvist S, Alverdi V, Mengel B, Hoffmann A, Ghosh G, Komives EA. Kinetic enhancement of NF-kappaB•DNA dissociation by IkappaBalpha. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2009 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908797106. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu JQ, McCormick CD, Pollard TD. Chapter 9: Counting proteins in living cells by quantitative fluorescence microscopy with internal standards. Methods Cell Biol. 2008;89:253–273. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)00609-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pollard TD, Berro J. Mathematical models and simulations of cellular processes based on actin filaments. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:5433–5437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800043200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. DeLano Scientific; San Carlos, CA, USA: 2002. [Google Scholar]