Abstract

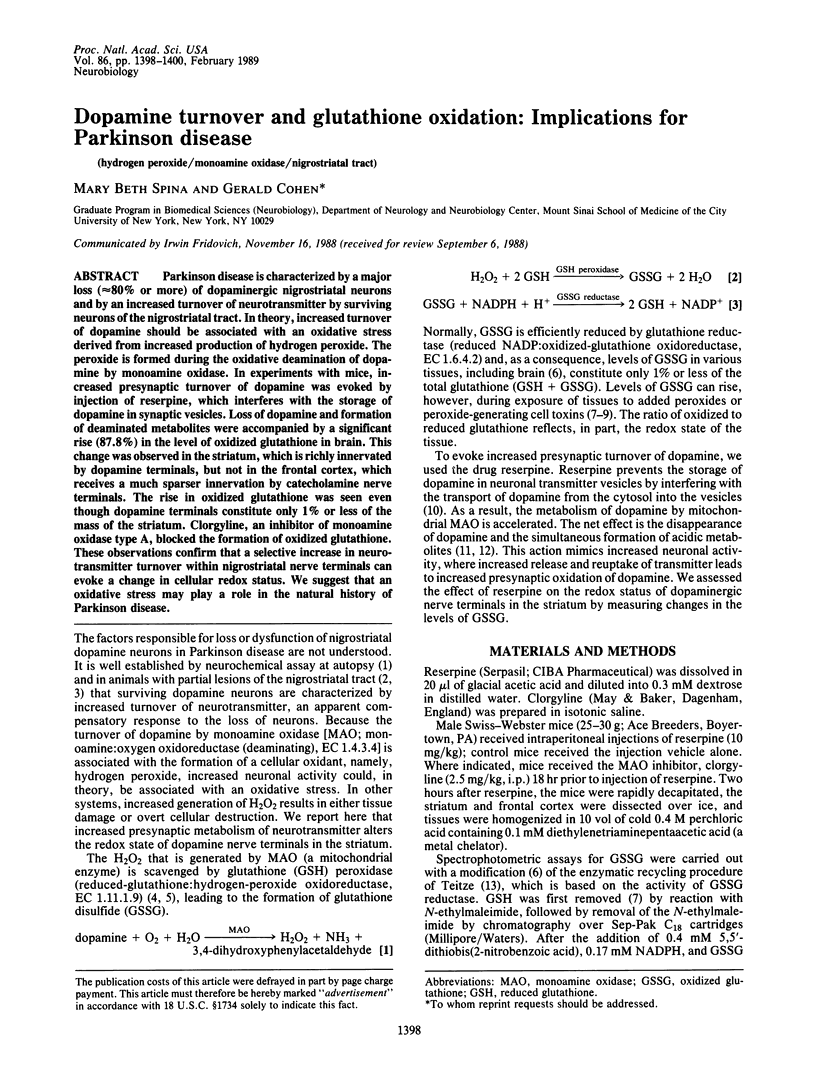

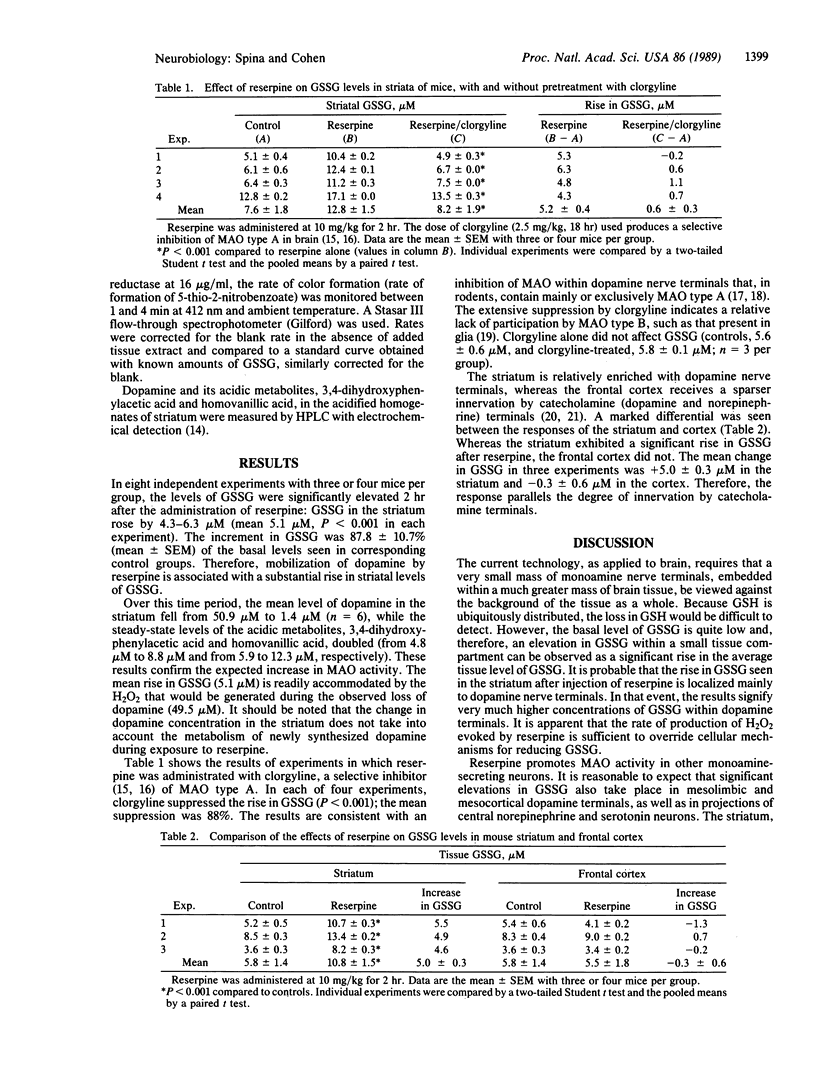

Parkinson disease is characterized by a major loss (approximately 80% or more) of dopaminergic nigrostriatal neurons and by an increased turnover of neurotransmitter by surviving neurons of the nigrostriatal tract. In theory, increased turnover of dopamine should be associated with an oxidative stress derived from increased production of hydrogen peroxide. The peroxide is formed during the oxidative deamination of dopamine by monoamine oxidase. In experiments with mice, increased presynaptic turnover of dopamine was evoked by injection of reserpine, which interferes with the storage of dopamine in synaptic vesicles. Loss of dopamine and formation of deaminated metabolites were accompanied by a significant rise (87.8%) in the level of oxidized glutathione in brain. This change was observed in the striatum, which is richly innervated by dopamine terminals, but not in the frontal cortex, which receives a much sparser innervation by catecholamine nerve terminals. The rise in oxidized glutathione was seen even though dopamine terminals constitute only 1% or less of the mass of the striatum. Clorgyline, an inhibitor of monoamine oxidase type A, blocked the formation of oxidized glutathione. These observations confirm that a selective increase in neurotransmitter turnover within nigrostriatal nerve terminals can evoke a change in cellular redox status. We suggest that an oxidative stress may play a role in the natural history of Parkinson disease.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adams J. D., Jr, Lauterburg B. H., Mitchell J. R. Plasma glutathione and glutathione disulfide in the rat: regulation and response to oxidative stress. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1983 Dec;227(3):749–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altar C. A., Marien M. R., Marshall J. F. Time course of adaptations in dopamine biosynthesis, metabolism, and release following nigrostriatal lesions: implications for behavioral recovery from brain injury. J Neurochem. 1987 Feb;48(2):390–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb04106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andén N. E., Hfuxe K., Hamberger B., Hökfelt T. A quantitative study on the nigro-neostriatal dopamine neuron system in the rat. Acta Physiol Scand. 1966 Jul-Aug;67(3):306–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1966.tb03317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen G., Heikkila R. E., Allis B., Cabbat F., Dembiec D., MacNamee D., Mytilineou C., Winston B. Destruction of sympathetic nerve terminals by 6-hydroxydopamine: protection by 1-phenyl-3-(2-thiazolyl)-2-thiourea, diethyldithiocarbamate, methimazole, cysteamine, ethanol and n-butanol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1976 Nov;199(2):336–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen G. The pathobiology of Parkinson's disease: biochemical aspects of dopamine neuron senescence. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1983;19:89–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FUXE K. EVIDENCE FOR THE EXISTENCE OF MONOAMINE NEURONS IN THE CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM. IV. DISTRIBUTION OF MONOAMINE NERVE TERMINALS IN THE CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1965:SUPPL 247–247:37+. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller R. W., Hemrick-Luecke S. K. Influence of selective, reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase on the prolonged depletion of striatal dopamine by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine in mice. Life Sci. 1985 Sep 23;37(12):1089–1096. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(85)90352-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert H. F. Biological disulfides: the third messenger? Modulation of phosphofructokinase activity by thiol/disulfide exchange. J Biol Chem. 1982 Oct 25;257(20):12086–12091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glowinski J., Iversen L. L. Regional studies of catecholamines in the rat brain. I. The disposition of [3H]norepinephrine, [3H]dopamine and [3H]dopa in various regions of the brain. J Neurochem. 1966 Aug;13(8):655–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1966.tb09873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefti F., Melamed E., Wurtman R. J. Partial lesions of the dopaminergic nigrostriatal system in rat brain: biochemical characterization. Brain Res. 1980 Aug 11;195(1):123–137. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90871-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong M., Jenner P., Marsden C. D. Comparison of the acute actions of amine-depleting drugs and dopamine receptor antagonists on dopamine function in the brain in rats. Neuropharmacology. 1987 Feb-Mar;26(2-3):237–245. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(87)90214-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornykiewicz O., Kish S. J. Biochemical pathophysiology of Parkinson's disease. Adv Neurol. 1987;45:19–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindt M. V., Youngster S. K., Sonsalla P. K., Duvoisin R. C., Heikkila R. E. Role for monoamine oxidase-A (MAO-A) in the bioactivation and nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurotoxicity of the MPTP analog, 2'Me-MPTP. Eur J Pharmacol. 1988 Feb 9;146(2-3):313–318. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90308-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanoff S. J. Oxygen metabolism and the toxic properties of phagocytes. Ann Intern Med. 1980 Sep;93(3):480–489. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-93-3-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt P., Pintar J. E., Breakefield X. O. Immunocytochemical demonstration of monoamine oxidase B in brain astrocytes and serotonergic neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Oct;79(20):6385–6389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.20.6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin R. Drug trial for Parkinson's. Science. 1987 Jun 12;236(4807):1420–1420. doi: 10.1126/science.3109033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maker H. S., Weiss C., Silides D. J., Cohen G. Coupling of dopamine oxidation (monoamine oxidase activity) to glutathione oxidation via the generation of hydrogen peroxide in rat brain homogenates. J Neurochem. 1981 Feb;36(2):589–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1981.tb01631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T. B., Angers M. Effects of different monoamine oxidase inhibitors on the metabolism of L-dopa in the rat brain. Biochem Pharmacol. 1987 May 15;36(10):1731–1735. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(87)90060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offermann M. K., McKay M. J., Marsh M. W., Bond J. S. Glutathione disulfide inactivates, destabilizes, and enhances proteolytic susceptibility of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase. J Biol Chem. 1984 Jul 25;259(14):8886–8891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshino N., Chance B. Properties of glutathione release observed during reduction of organic hydroperoxide, demethylation of aminopyrine and oxidation of some substances in perfused rat liver, and their implications for the physiological function of catalase. Biochem J. 1977 Mar 15;162(3):509–525. doi: 10.1042/bj1620509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponzio F., Achilli G., Calderini G., Ferretti P., Perego C., Toffano G., Algeri S. Depletion and recovery of neuronal monoamine storage in rats of different ages treated with reserpine. Neurobiol Aging. 1984 Summer;5(2):101–104. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(84)90038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slivka A., Brannan T. S., Weinberger J., Knott P. J., Cohen G. Increase in extracellular dopamine in the striatum during cerebral ischemia: a study utilizing cerebral microdialysis. J Neurochem. 1988 Jun;50(6):1714–1718. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb02468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slivka A., Spina M. B., Cohen G. Reduced and oxidized glutathione in human and monkey brain. Neurosci Lett. 1987 Feb 10;74(1):112–118. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spina M. B., Cohen G. Exposure of striatal [corrected] synaptosomes to L-dopa increases levels of oxidized glutathione. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988 Nov;247(2):502–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland M. W., Nelson J., Harrison G., Forman H. J. Effects of t-butyl hydroperoxide on NADPH, glutathione, and the respiratory burst of rat alveolar macrophages. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985 Dec;243(2):325–331. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90509-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urwyler S., von Wartburg J. P. Studies on the subcellular localization of monoamine oxidase types A and B and its importance for the deamination of dopamine in the rat brain. Biochem Pharmacol. 1980 Nov 15;29(22):3067–3073. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(80)90447-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]