Abstract

Blastomere cytofragmentation in mammalian embryos poses a significant problem in applied and clinical embryology. Mouse two-cell-stage embryos display strain-dependent differences in the rate of cytofragmentation, with a high rate observed in C3H/HeJ embryos and a lower rate observed in C57BL/6 embryos. The maternally inherited genome exerts the strongest effect on the process, with lesser effects mediated by the paternally inherited genome and the ooplasm. The effect of the maternal genome is transcription dependent and independent of the mitochondrial strain of origin. To identify molecular mechanisms that underlie cytofragmentation, we evaluated transcriptional activities of embryos possessing maternal pronuclei (mPN) of different origins. The mPN from C57BL/6 and C3H/HeJ strains directed specific transcription at the two-cell stage of mRNAs corresponding to 935 and 864 Affymetrix probe set IDs, respectively. Comparing transcriptomes of two-cell-stage embryos with different mPN revealed 64 transcribed genes with differential expression (1.4-fold or greater). Some of these genes occupy molecular pathways that may regulate cytofragmentation via a combination of effects related to apoptosis and effects on the cytoskeleton. These results implicate specific molecular mechanisms that may regulate cytofragmentation in early mammalian embryos. The most striking effect of mPN strain of origin on gene expression was on adenylate cyclase 2 (Adcy2). Treatment with dibutyryl cAMP (dbcAMP) elicits a high rate and severe form of cytofragmentation, and the effective dbcAMP concentration varies with maternal genotype. An activator of exchange proteins directly activated by cAMP (EPACs, or RAPGEF 3 and 4) 8-pCPT-2′-O-methyl-cAMP, elicits a high level of fragmentation while the PKA-specific activator N6-benzoyl-cAMP does not. Inhibition of A kinase anchor protein activities with st-Ht31 induces fragmentation. Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling also induces fragmentation. These results reveal novel mechanisms by which maternal genotype affects cytofragmentation, including a system of opposing signaling pathways that most likely operate by controlling cytoskeletal function.

Keywords: EPACs, apoptosis, gene array, signal transduction, cytoskeleton, adenylate cyclase

from the earliest time in life, death must be overcome. Mammalian embryos are predisposed to die unless crucial early developmental events intervene to suppress death. The ability to impose this early suppression of programmed cell death has been proposed as an early “quality control” mechanism that preserves maternal resources by eliminating unfit embryos on the basis of a failure to execute essential early events, including cell cycle passage and transcriptional genome activation (24). As an early quality control check, it is fitting that the maternally inherited chromosomes exert the strongest control over whether an embryo undergoes cytofragmentation (17, 18). This has been demonstrated in mouse genetic studies using two inbred strains, C57BL/6 and C3H/HeJ (hereinafter referred to as B6 and C3H) with low versus high rates of fragmentation at the two-cell stage, respectively (17, 18). In maternal pronucleus (mPN) transfer studies, a B6 mPN suppresses fragmentation and a C3H mPN increases it, regardless of the strain of origin of sperm or ooplasm (17, 18). The mPN effect is sensitive to treatment with α-amanitin and thus is transcription dependent (17). More recent studies revealed that the ooplasm strain of origin can also affect fragmentation rate to a mild degree, and that this occurs at least in part via interactions with the paternal pronucleus (pPN) (18).

Cytofragmentation is believed to reflect apoptotic processes in the embryo (5, 6, 24–27, 30, 46, 60). Among the cellular and molecular indicators of early cell death are nuclear fragmentation, blastomere cytofragmentation, DNA fragmentation, caspase activation, and annexin V exteriorization, all of which are classical hallmarks of the well-regulated process known as apoptosis (3, 7, 20, 26, 27, 30, 33, 39, 50). In contrast to somatic cells, however, early embryos may not display all of these hallmarks concurrently (21, 60). Blastomere cytofragmentation appears to be the most widespread indicator of apoptosis, while other markers such as DNA fragmentation are not universally associated with cytofragmentation. Aside from apoptosis, an alternative mechanism triggering cytofragmentation may be disruption in the correct control of the cytoskeleton. The mammalian embryo is notable for its comparatively large size, hence correct control of cellular architecture is key for sustained development. Uncontrolled actin depolymerization or uncontrolled formation and activation of a contractile apparatus could account for the frequent observation of cytofragmentation in the absence of other markers of apoptosis.

Oocyte or blastomere fragmentation is seen in a number of different mammalian species, including cow, mouse, and human (2, 3, 7, 20, 33, 39, 57). Clinically, this reduces the number of high-quality embryos available for establishing pregnancy. Of human embryos produced by in vitro fertilization, more than 80% exhibit some degree of cellular fragmentation (27), and this propensity appears to be programmed by the one-cell stage (19). Fragmented embryos can produce term pregnancies, but fragmentation is associated with reduced egg quality and lower developmental potential (2, 15). Studies of cytofragmentation in mouse embryos, however, indicate that fragmentation can be chiefly attributable to genetic factors (i.e., the maternal genome) as opposed to ooplasmic factors. Additionally, apoptosis and fragmentation may reflect embryonic responses to suboptimal in vitro procedures (4, 10–13, 28, 35, 36, 41, 42, 47), rather than inherent genetic or ooplasmic deficiencies. Thus, human embryos may not fragment because they are of poor quality, but because they are by chance poorly equipped to withstand suboptimum culture conditions. Whatever the cause of cytofragmentation, the long-term outlook for pregnancy and post-natal life might be enhanced by preventing it.

The mouse genetic model of cytofragmentation (C3H vs. B6) provides an ideal system with which to identify genes that mediate cytofragmentation, define the pathways that underlie the process, and devise novel approaches for controlling the process. Because cytofragmentation is controlled primarily by a transcription-dependent effect of the maternal pronucleus (PN), we undertook a comparison of the two-cell-stage transcriptomes of embryos differing solely in their mPN strains of origin. The mPN of the two strains directed the α-amanitin-sensitive, differential transcription of a large number of genes. This differential gene activity resulted in an overall difference in expression of 64 genes at the two-cell stage between embryos with different mPN strain of origin. Some of these genes reside in molecular pathways with the capacity to regulate apoptosis and actin polymerization. One of the largest expression differences involved adenylate cyclase 2. Treatment of embryos with dibutyryl cAMP (dbcAMP) elicited a dramatic fragmentation phenotype, and the effective dosage varied with maternal genotype, confirming this pathway as a novel regulator of the process contributing to the strain difference. Additional studies implicate signaling via cAMP-activated exchange proteins (EPACs, or RAPGEF3 and RAPGEF4) in promoting fragmentation, while A kinase anchor proteins (AKAPs) and signaling via phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PIK3) inhibit the process, indicating a system of opposing pathways that most likely regulate the cytoskeleton. Caspase activation in fragmenting embryos confirms a link between apoptosis pathways and pathways controlling cytofragmentation. These results illuminate the possible mechanisms underlying cytofragmentation and how the process may be affected by endogenous and exogenous factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice, embryos, and embryo culture.

Mice of the B6 strain were purchased from Harlan Sprague-Dawley (Indianapolis, IN). Adult C3H mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Females (8–15 wk of age) were typically superovulated by injection of 5 IU equine chorionic gonadotropin (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) followed 48 h later by 5 IU human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and then mated (males >10 wk of age). All studies adhered to procedures consistent with the National Research Council Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All procedures employing laboratory animals were evaluated and approved by the Temple University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and satisfied the guidelines for laboratory animal welfare.

Embryos were isolated at the one-cell stage, ∼19 h post-hCG (hphCG). Cumulus cells were removed by digestion with hyaluronidase (500 U/mg, 120 U/ml; ICN Pharmaceuticals, Costa Mesa, CA) in M2 medium at room temperature. Embryos were cultured in CZB medium (8) as in the previous studies (17, 18, 21) to maintain continuity with those studies. Embryos of both strains develop efficiently beyond the two-cell stage in CZB medium. Any unfertilized eggs or morphologically abnormal embryos were removed.

Production of embryos by PN transfer and intracytoplasmic sperm injection.

PN transfers were performed 22–25 hphCG as described (17). The polar bodies were removed during PN transfer. Electrofusion (900 V/cm, 10 ms, one pulse) was performed in fusion medium (275 mM mannitol, 0.05 mM CaCl2, 0.10 mM MgSO4, and 0.3% bovine serum albumin). Only constructs that fused after a single pulse and yielded single cell, intact embryos were retained. The survival rates of reconstructed embryos were over 90%. After PN transfer, embryos were returned to CZB medium and cultured overnight as described (17, 21) with or without α-amanitin. The cleavage rates of the PN transfer embryos were over 95%. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) that was used to obtain fertilized embryos was performed as described (61) using a piezo pipette micromanipulator (PMM Prime Tech, Ibaraki-ke, Japan).

Chemical treatments.

One-cell embryos isolated 20–21 hphCG were cultured in CZB media supplemented with 2.5 and 25 μM dbcAMP (Calbiochem/EMD Bioscience, Gibbstown, NJ). After 24 h, embryos were analyzed for cytofragmentation as described (17, 18, 21) or fixed for caspase analysis. Embryos at these stages were also treated with the AKAP inhibitor st-Ht31 (Promega, Madison, WI), the PKA activator N6-benzoyl-cAMP (Calbiochem/EMD Bioscience), the EPAC activator 8-pCPT-2′-O-methyl-cAMP (Calbiochem), and the PIK3 inhibitors LY-294002 (Calbiochem) and wortmannin (Calbiochem).

RNA isolation, amplification, and hybridization.

RNA isolation was performed with the PicoPure kit (Arcturus, Mountain View, CA) as described (51). Embryos (16–21 per sample) at late two-cell stage were collected into 20 μl of extraction buffer 50 hphCG and then stored at −70°C until processing. For each sample, the mRNA population was reverse transcribed after oligo(dT) priming as described (51). The cDNA was employed for a first round of in vitro transcription, followed by random priming and a second round of reverse transcription and in vitro transcription to achieve a linear amplification (Affymetrix Small Sample Technical Bulletin, www.affymetrix.com) with the following minor modifications: the initial volume for mRNA annealing was raised to 5 μl, and the conditions for reverse transcription were 30 min at 42°C followed by 30 min at 45°C to increase the reaction efficiency in GC-rich regions of mRNA. The amplified cRNA samples were fragmented, and 10 μg were hybridized to Affymetrix MOE 430 2.0 Gene Chips in the University of Pennsylvania Microarray Facility, then washed and stained on fluidic stations, and scanned according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Array analysis.

Microarray Analysis Suite 5.0 (MAS 5.0, Affymetrix) program was used to quantify the microarray signals with default analysis parameters and global scaling to target a mean equal to 150 signal units. Quality control parameters for all samples were within ranges shown in Supplemental Table S1 (supplemental data can be found in the online version of this article at American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology website). The raw data of all samples are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo, accession no. GSE17886). The MAS metric output was loaded into GeneSpring GX v7.3.1 (Agilent Technologies, Foster City, CA) with per chip normalization to the 50th percentile and per gene normalization to the median. To minimize false positive signals, only genes called “present” in at least three out of four replicates in one embryo kind/condition were used for further analysis with all statistical packages. The K-means hierarchical clustering of GeneSpring GX v7.3.1 was used among samples to divide them into groups based on their expression patterns and to produce groups with a high degree of similarity within groups and low degree of similarity between groups. The Affymetrix MOE430 2.0 array interrogates one gene with every probe set, and 14.7% of the genes present on the array are represented by more than one probe set. All analyses described were performed using the Affymetrix probe set lists, except when noted where gene numbers were used to avoid redundancy. The Statistical Analysis of Microarray (SAM) (49) algorithm was applied to identify genes with significant differences among samples at the 10% false discovery rate. Genes were further selected as differentially expressed on the basis of t-test (P < 0.05). Fold changes of expression differences between stages and conditions were calculated following SAM analysis. The resulting lists of differentially expressed genes (fold change ≥ 1.4) were imported into Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA, www.ingenuity.com) and Expression Analysis Systematic Explorer (EASE, version 2.0) to detect networks detailing physical association or functional interaction among transcripts falling into different gene ontology annotation categories.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis.

Total RNA was isolated as described above. Twenty genes were selected for analysis and their mRNAs quantified by reverse transcription followed by real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) (ABI PRISM 7000). Three replicates were used for each qRT-PCR reaction, and each mRNA was analyzed two to three times per replicate. Minus RT and minus primers/probe reactions served as controls. The ABI TaqMan gene expression primers/probes were from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Quantification was normalized to the endogenous histone H2A [Mm-00501974_s1, (Hisst2ah2aa10)] within the log linear phase of the amplification curve using the comparative Ct method (31), where Ct is threshold cycle. These mRNAs were selected to be examined by qRT-PCR because of their apparent abundances as judged by the microarray hybridization signals and as representatives of specific functional categories.

Analysis of caspase activity.

For performing the analysis of caspase activity, the two-cell embryos with or without dbcAMP treatment were stained with CaspACETM FITC-VAD-FMK, a fluorescent analog of the pan caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK [carbobenzoxy-valyl-alanyl-aspartyl-(O-methyl)-fluoromethylketone; Promega, Madison, WI] at a final concentration of 10 μM for 20 min and then fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscope Sciences, Hatfield, PA) in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. The samples were treated for 5 min with 10 μg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich) to stain the DNA and then mounted on a glass slide for the observation by confocal microscopy. Confocal microscopy was performed on an inverted Olympus (Olympus America) microscope equipped with the fluoview confocal lasers and scanning software (Olympus).

RESULTS

Previous studies indicated that the rate of cytofragmentation at the two-cell stage is controlled by the maternal genotype, predominantly by the strain of origin of the mPN, with lesser effects of the ooplasm strain of origin and the paternal genotype (17). The effect of the mPN is sensitive to treatment with α-amanitin, indicating that it requires transcription from the mPN at this early stage. The objective of this study was to identify genes that display differential expression at the two-cell stage dependent on maternal PN strain of origin. Such genes should include those that control cytofragmentation, enabling identification of specific molecular mechanisms that regulate the process.

To accomplish this, we constructed one-cell-stage embryos by mPN transfer having B6 ooplasm, B6 pPN, and either B6 or C3H mPN (BBB and BCB, respectively). Previous studies revealed transcription-dependent differences in cytofragmentation rates for these two kinds of embryos (17). Additionally, we collected embryos of each type that were either treated or untreated with α-amanitin. Comparison of the transcriptomes of these different kinds of embryos should reveal genes for which expression differs according to maternal PN strain of origin, and the α-amanitin data should reveal which of these differences is due to gene transcription, as opposed to any transcription-independent differences attributable to ooplasm-derived maternal mRNA pools. Pronuclear transfer is obviously required to produce embryos that possess maternal chromosomes of different origins within identical ooplasm, and these manipulations could affect the transcriptome. However, because all embryos being compared were produced by pronuclear transfer, all of the steps involved in the production and culture of these embryos are held constant, hence the array comparisons evaluate the effects of genetic origin of the mPN.

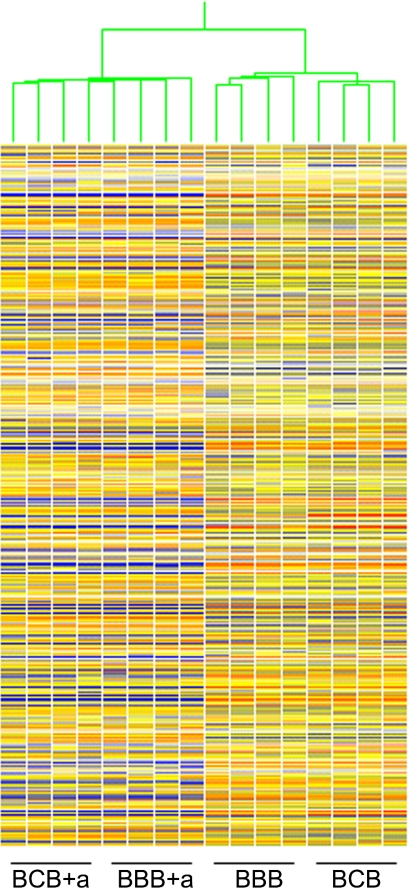

We obtained four high-quality samples of each embryo kind/treatment and processed the samples for array analysis. Among the eight arrays (BBB and BCB), percent present call ranged from 48.0 to 49.9, corresponding to ∼21,648 to 22,504 probe sets, which is well within the acceptable range (30 to 60), and an overall presence call of 48.9% (22,059 of 45,101 probe sets) (Supplemental Table S1). The other quality control parameters for all the samples were also within the following ranges: scale factor 0.53 to 0.77 (accepted range: 0.5 to 5.0), and background 42.5 to 54.9 (accepted range: 20 to 100) (Supplemental Table S1). We also compared these array sets to arrays for α-amanitin-treated BBB and BCB embryos (BBB+a and BCB+a). The arrays for α-amanitin-treated embryos yielded an average presence call of 40.7%, and other quality control parameters were within the acceptable range (Supplemental Table S1). We used K-means hierarchical clustering to ascertain the overall degree of similarity between the transcriptomes of the BBB, BCB, BBB+a, and BCB+a two-cell embryos after filtering for presence call in at least three out of four replicates of at least one of the conditions (Fig. 1). The replicates of four kinds of embryos readily clustered appropriately, with no apparent outliers. This clustering pattern indicated a high degree of reproducibility and small biological variability between samples of each kind of embryo, and it also indicated sufficient difference between the two kinds of embryos to allow them to cluster separately. There was slightly more similarity between α-amanitin treated BBB and BCB embryos, which is not surprising because of the suppression of any differential expression by the C3H and B6 maternal pronuclei.

Fig. 1.

Hierarchical clustering of untreated [having C57BL/6 (B6) ooplasm, B6 paternal pronuclei, and either B6 (BBB) or C3H/HeJ (BCB) maternal pronuclei] and α-amanitin-treated (BBB+a and BCB+a) two-cell embryos after filtering for presence call in at least 3 out of 4 replicates of at least one of the conditions.

Maternal PN strain-specific sensitivity to α-amanitin treatment.

Comparing BBB untreated and α-amanitin-treated embryos revealed which genes were actively transcribed in BBB embryos, and comparing BCB untreated and α-amanitin-treated embryos revealed which genes were actively transcribed in BCB. A total of 8,525 probe sets displayed α-amanitin sensitivity (1.4-fold or greater reduction with treatment) in the BBB embryos and a total of 8,454 probes sets were sensitive in BCB embryos. The lists of α-amanitin-sensitive transcribed genes were not identical between the two embryo types, indicating differential transcriptional activity dependent on mPN strain of origin. There were 935 probe sets showing sensitivity to treatment in embryos with B6 mPN but not with C3H mPN, and 864 probe sets showing the reciprocal sensitivity (Supplemental Tables S2 and S3). This differential transcriptional activity of the two kinds of mPN provides a basis for the differential effect of maternal genome transcription on embryo phenotype.

Identification of genes differentially expressed between BBB and BCB embryos.

We compared the gene expression profiles of the BBB and BCB embryos to each other. Although a large number of genes displayed differential α-amanitin sensitivity with the 1.4-fold cutoff applied, a much smaller number of genes actually displayed a statistically significant difference in transcript abundance comparing the BBB and BCB embryos at the two-cell stage. The results provide the first indication of the overall effect of mPN strain of origin on the two-cell-stage embryo transcriptome.

Differentially expressed genes were identified by using the SAM package followed by application of a t-test (P < 0.05 considered significant) (Supplemental Tables S4–S7). A total of 89 genes displayed statistically significant differences in expression between BBB and BCB embryos and were also sensitive to α-amanitin treatment. There were 41 genes more highly expressed at the level of 1.4-fold or greater in BBB embryos (Supplemental Table S4). The differences in expression for these genes were generally small, ranging from 1.5- to 3.5-fold. There were 23 genes sensitive to α-amanitin treatment and expressed at least 1.4-fold more highly in BCB embryos (Supplemental Table S5). These genes included many with dramatic differences, ranging as high as 100-fold, indicating that elevated expression with a C3H maternally inherited genome constitutes the largest effect on individual gene expression. Two genes (Dusp10 and Tmem77) displayed higher expression in BCB embryos but were not sensitive to α-amanitin, and four genes (Crtc1, Kif3a, Man2a1, and Rps6kb1) were so affected in BBB embryos (Supplemental Tables S6 and S7).

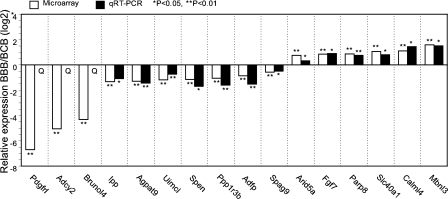

From among the differentially expressed genes listed in Supplemental Tables S4 and S5, 16 were selected for testing by qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. 2). All 16 mRNAs displayed either qualitative differences (Adcy2, Pdgfrl, and Brunol4) or significant quantitative differences in expression by this method, and the ratios of expression by qRT-CPR were in excellent agreement with the ratios seen in the array data. These results confirm the validity of the array data and the identifications of genes differentially expressed between BBB and BCB embryos.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of array results and quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) results showing differences in mRNA expression between BBB and BCB two-cell embryos. Q, qualitative difference, not detected in BBB.

Biofunction and pathway analysis of differentially expressed mRNAs.

To determine whether the affected genes could account for the observed effects of mPN strain of origin on the two-cell-stage cytofragmentation phenotype, we examined the known biological functions of the genes listed in Supplemental Table S4 and S5, and their known relationships to specific biological processes and networks using the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis program. This analysis (Supplemental Table S8) yielded a number of highly significant biofunction categories likely relevant to cytofragmentation, including cell death, cell morphology, cellular assembly and organization, cell growth and proliferation, gene expression, and nucleic acid metabolism. Some additional categories that are prominent and that could affect overall physiology of the cell are lipid metabolism, small molecule biochemistry, carbohydrate metabolism, and molecular transport. Additional categories contain a large fraction of affected genes, have less obvious connections to cytofragmentation, and are related to a range of genetic disorders (e.g., Hurler's syndrome, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and cardiovascular disease) that are linked to immune responses, endocrine functions, or cell/tissue degeneration.

We also used the EASE program to evaluate affected biological processes amongst genes with elevated expression in BBB embryos (Supplemental Table S9). This analysis revealed affected gene ontology categories antigen processing and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class complex, although these categories only encompassed three or four of the affected genes. This category echoes the immune responses revealed in the Ingenuity analysis. Among the genes displaying the largest differences in expression was H2-Q8. Other affected genes of potential interest for their roles in apoptosis and cytoskeletal function (two processes that may contribute to cytofragmentation) included Calml4, Dst, Mbnl3, Parp8, and Snx6.

Among the genes more highly expressed in BCB embryos, EASE analysis yielded significant overrepresentation for the gene ontology categories of mRNA processing, mRNA metabolism, G protein signaling and adenylate cyclase activating pathway, receptor activity, and a number of transcription-related categories (Supplemental Table S10). The numbers of genes encompassed in these categories (2 to 9) were again small. The genes showing the largest differences in average raw intensity values were Pdgfrl (>100-fold), Gabra1 (90-fold), Adcy2 (39-fold), Mdga2 (28-fold), Acn9 (20-fold), Brunol4 (20-fold), and Wdr16 (15-fold). Genes with known functions that could play roles in the control of apoptosis or cytoskeletal function include Pdgfrl, Adcy2, Nfkbil1, Capn8, and Ppp1r3b.

Effect of parental origin of PN on gene expression.

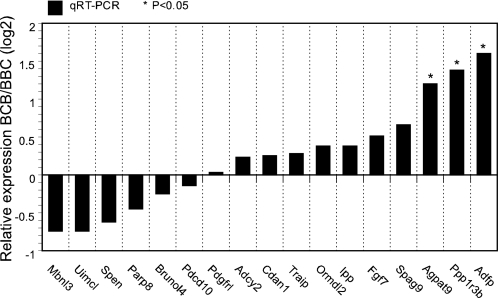

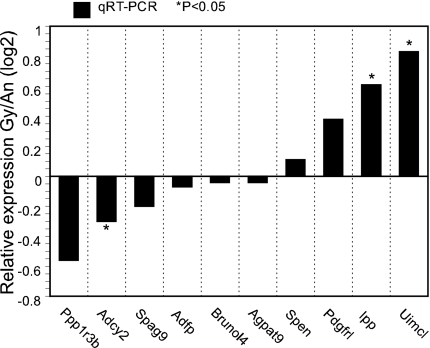

The previous pronuclear transfer studies (17, 18) indicated that the mPN exerts a predominant role in controlling cytofragmentation, with a relatively weak effect of the paternal PN. This phenomenon suggests a possible parental-origin effect on genes expressed at the two-cell stage, directing higher expression from the mPN, possibly as a result of genomic imprinting. We compared the lists of affected genes to the published lists of known or suspected imprinted genes for mouse and human (www.geneimprint.com; 39). Aside from Brunol4, for which the homologue is a candidate imprinted gene in the human, we found no candidate for an imprinted gene that could account for the strong effect of the mPN. To determine whether any of the affected genes showing large differences in expression between BBB and BCB embryos displayed any parental origin effect or imprinting effect, we examined expression of the affected genes by qRT-PCR in two ways. First, we compared expression between BCB embryos produced by mPN transfer and BBC embryos produced by ICSI (ICSI was employed to get the manipulated control embryos). Of the 17 genes examined, only three (Agpat9, Ppp1r3b, and Adfp) displayed any significant difference; however, the fold change was quite low (only about 2- to 3-fold) slightly enhanced in favor of maternal C3H allele expression (Fig. 3). We next compared the expression of 10 genes (including Agpat9, Ppp1r3b, and Adfp) between diploid C3H androgenones (two paternal genomes) and C3H gynogenones (two maternal genomes) constructed by PN transfer (Fig. 4). None of these genes displayed the expected strong differential expression typical of imprinted genes, though a few displayed minor differences in expression possibly related to different developmental staging between the two kinds of embryos.

Fig. 3.

qRT-PCR assays of mRNA expression in BCB and BBC two-cell embryos. The BCB embryos were produced by maternal pronuclear transfer and the BBC embryos were produced by intracytoplasmic sperm injection of C3H/HeJ sperm into B6 eggs.

Fig. 4.

qRT-PCR assays of mRNA expression in C3H/HeJ gynogenetic (Gy) and C3H/HeJ androgenetic (An) two-cell embryos. Constructs were prepared using C3HXC3H zygotes.

Caspase activation in fragmenting embryos.

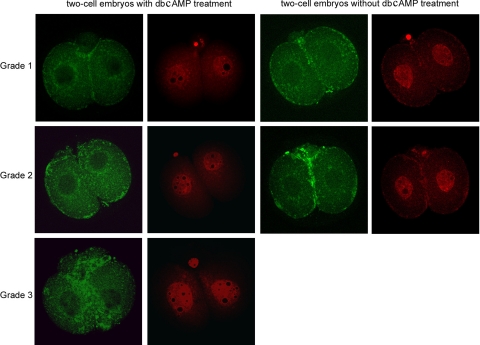

Cytofragmentation is widely believed to reflect apoptotic processes in oocytes or early embryos; however, some hallmarks of apoptosis in somatic cells (e.g., DNA fragmentation) may not accompany cytofragmentation (21). The presence of genes that potentially regulate apoptosis and intracellular signaling among the affected gene lists (Supplemental Tables S4 and S5) provides further indication that cytofragmentation could reflect activation of apoptotic processes within the early embryo. To explore this possibility further, we examined cytofragmented embryos for activation of endogenous caspases (Fig. 5). We observed that caspase activation indeed occurs in severely fragmented embryos, particularly within the fragments themselves. However, caspase activation is not a prominent feature of embryos showing only a mild cytofragmentation phenotype.

Fig. 5.

Confocal microscopic imaging of the caspase activation in grade 1–3 fragmented two-cell-stage embryos with or without dibutyryl (db)cAMP treatment. The green fluorescence shows the caspase activity of each embryo and the corresponding panels with red fluorescence show DNA stained with propidium iodide.

Effect of dbcAMP on fragmentation and caspase activation.

The EASE analysis yielded G protein signaling, adenylate cyclase activating pathway as one of the overrepresented gene ontology categories. One of the most highly overexpressed genes in the BCB embryos is Adcy2, encoding a variant of adenylate cyclase. We therefore tested whether an increase in cyclic AMP could affect the cytofragmentation phenotype (Fig. 5). For these studies, we employed embryos produced without the use of pronuclear transfer. We treated embryos from either B6XB6 or C3HXB6 crosses with 2.5 or 25 μM dbcAMP starting at the late one-cell stage onward and observed cytofragmentation at the two-cell stage (Table 1). At 25 μM dbcAMP there was a twofold increase in the total rate of cytofragmentation for C3HXB6 embryos and a fourfold increase for B6XB6 embryos compared with untreated embryos. There was a dramatic increase in the incidence of the more severe cytofragmentation grades 2 and 3 for C3HXB6 embryos (17% vs. 2%), whereas the incidence of severe fragmentation remained limited (3%) for B6XB6 embryos. At 2.5 μM dbcAMP, there was a 3.5-fold increase in total cytofragmentation for C3HXB6 and twofold for B6XB6 embryos however, the increase in the more severe grades 2 and 3 cytofragmentation remained pronounced for the C3HXB6 embryos (27%) but limited (3%) for B6XB6 embryos.

Table 1.

Effects of PKA, EPAC, and PIK3 activators and inhibitors on cytofragmentation phenotype

| Number Fragmented (%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration, μM | Embryo Genotype | Total | No. of Experiments | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Total |

| 25 | B × B | 158 | 4 | 35 (22)c,g | 2 (1.3) | 3 (2) | 40 (25)c,g |

| 25 | C × B | 276 | 5 | 29 (11) | 41 (15)c | 5 (1.8) | 75 (27)c |

| 2.5 | B × B | 131 | 4 | 13 (10)g | 3 (2.3)b | 1 (0.7)g | 17 (13)b,g |

| 2.5 | C × B | 139 | 4 | 32 (23)c | 15 (11)c | 22 (16)c | 69 (50)c |

| 0 | B × B | 290 | 9 | 17 (6)g | 0 | 0 | 17 (6)g |

| 0 | C × B | 302 | 9 | 34 (11) | 6 (2) | 1 (0.3) | 41 (14) |

| N6-Benzoyl-cAMP | |||||||

| 10 | B × B | 115 | 2 | 7 (6) | 0 | 0 | 7 (6) |

| 10 | C × B | 132 | 2 | 17 (13) | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 18 (14) |

| st-Ht31 | |||||||

| 10 | B × B | 140 | 2 | 14 (10) | 15 (11)c | 7 (5)a,c | 36 (26)c |

| 10 | C × B | 119 | 2 | 20 (17) | 8 (7)a | 0 | 28 (24)a |

| st-Ht31 + High dbcAMP | |||||||

| 10 + 25 | B × B | 165 | 5 | 10 (6)f,g | 2 (1) | 0 | 12 (7)f,g |

| 10 + 25 | C × B | 311 | 5 | 53 (17) | 12 (4)f | 2 (1) | 67 (22)a |

| st-Ht31 + Low dbcAMP | |||||||

| 10 + 2.5 | B × B | 135 | 2 | 7 (5)g | 2 (2) | 0 | 9 (7)g |

| 10 + 2.5 | C × B | 108 | 2 | 17 (16) | 9 (8) | 3 (3) | 29 (27)f |

| 8-pCPT-2′-O-methyl-cAMP | |||||||

| 10 | B × B | 187 | 3 | 14 (8)g | 4 (2)a | 0 | 18 (10)g |

| 10 | C × B | 206 | 3 | 63 (31)c | 0 | 0 | 63 (31)c |

| LY-294002 | |||||||

| 10 | B × B | 115 | 2 | 20 (17)c,g | 10 (9)c,g | 5 (4)c | 35 (30)c,g |

| 10 | C × B | 70 | 2 | 50 (71)c | 0 | 0 | 50 (71)c |

| Wortmannin | |||||||

| 250 nM | B × B | 115 | 2 | 15 (13)g | 4 (3.5)b,g | 1 (0.9) | 20 (17)c,g |

| 250 nM | C × B | 70 | 2 | 40 (57)c | 10 (14)c | 2 (3) | 52 (74)c |

EPAC, cAMP-activated exchange proteins; PIK3, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; dbcAMP, dibutyryl cAMP. C, C3H/HeJ; B, C57BL/6. Significantly different from untreated: aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01; cP < 0.001. Significantly different from dbCAMP in double treatment of the same concentration: dP < 0.05, eP < 0.01; fP < 0.001. Significantly different from C × B: gP < 0.05.

To explore the pathway by which dbcAMP induces fragmentation, we evaluated the effects of specific activators of two alternate mediators, N6-benzoyl-cAMP to activate PKA, and 8-pCPT-2′-O-methyl-cAMP to activate the EPACs (or RAPGEF3 and RAPGEF4). We observed that N6-benzoyl-cAMP failed to induce fragmentation in either strain, yielding values nearly identical to those seen with untreated embryos. The EPAC activator 8-pCPT-2′-O-methyl-cAMP induced fragmentation to a high degree in embryos from C3H mothers but not B6 mothers. Interestingly, inhibiting AKAP interactions using st-Ht31 alone also activated fragmentation. Addition of st-Ht31 with either low or high dbcAMP doses yielded fragmentation rates similar to those with either drug alone for embryos from C3H mothers, although the unusually high rate (50%) observed with 2.5 μM dbcAMP in C × B embryos was reduced to a level (27%) seen in the other treatments. The addition of st-Ht31 and dbcAMP together yielded a low rate of fragmentation for embryos from B6 mothers.

Because in some cells EPACs can signal by activating the PIK3 pathway and because some of the mRNAs affected on the array may interact with this pathway, we evaluated the effects of PIK3 signaling pathway inhibitors on fragmentation. Inhibiting PIK3 activity with either LY-294002 or wortmannin alone resulted in a high level of fragmentation, opposite to the EPAC effect. These results thus implicate EPACs as mediators of the dbcAMP-induced fragmentation, and they suggest a PIK3-independent signaling pathway, most likely signaling via a member of the Ras-like small GTPase family.

To test whether dbcAMP could induce apoptosis like responses, we examined caspase activation after dbcAMP treatment. Caspase activation was a prominent feature of embryos induced to fragment with dbcAMP (Fig. 5).

DISCUSSION

Oocytes and early embryos are notable for their large cell size compared with somatic cells, and many other features such as altered cell cycles, altered metabolic properties, and altered homeostatic mechanisms (37). Each blastomere represents a substantial fraction of the future embryo and must be kept intact. Additionally, mammalian oocytes and embryos undergo a long period of transcriptional silence, during which cellular processes are regulated by posttranscriptional mechanisms until the embryonic genome becomes transcriptionally active again. When transcription resumes, a profound transition occurs from ooplasmic (posttranscriptional) to embryonic (transcriptional) control of development, which entails an extensive turnover of ooplasmic proteins and mRNAs in favor of a vastly different array of gene products (37). This transition must be carefully controlled so that basic cellular processes can continue, and the developmental program can be initiated. Failure to control this transition correctly can lead to abnormal events, potentially compromising embryo viability. Indeed, it has been proposed that fulfillment of this requirement is an early quality control check that can eliminate unfit embryos and conserve maternal resources (24).

Early demise of embryos and cytofragmentation are serious complications in assisted reproduction. Cytofragmentation can occur in human embryos with >80% displaying some degree of fragmentation (27). Although fragmented embryos can produce term pregnancies, and fragmentation alone is an inadequate predictor of developmental competence, fragmented embryos yield term deliveries at reduced frequencies (9, 14, 15, 22, 23, 29, 52). Fragmentation, which may reflect inherently poor egg quality, maternal age, and insufficient follicular development, can deplete the embryo of key molecules (3). Interestingly, removal of fragments enhances embryo survival (29), supporting the idea that preventing fragmentation should be advantageous, and also indicating that interventions to enhance embryo survival should be possible. The ability to reduce or prevent cytofragmentation clinically would be highly desirable. Cytofragmentation is most often thought of in terms of an apoptotic response, but because it can occur without other hallmarks of apoptosis (21), this connection is tentative at best, and the underlying cause of cytofragmentation has remained unknown. A solid foundation of knowledge is thus needed to control the process predictably and minimize nonspecific effects during assisted reproduction.

This study has revealed for the first time a dramatic effect of maternal genotype on gene expression at the two-cell stage and how a subset of these genes contributes to the control of cytofragmentation. We observed nearly 2,000 genes for which mRNA abundance displays quantitative differences between strains in sensitivity to α-amanitin treatment. We also observed genes that are significantly differentially expressed between embryos that differ only in the origin of their mPN. The number of genes differing between the embryo types (64 transcribed genes differing at the level of 1.4-fold or greater difference) is comparatively small. These genes provide for the first time insight into the specific molecular pathways that likely link maternal genotype to cytofragmentation phenotype. While the array data were obtained from embryos that had undergone maternal pronuclear transfer and embryo culture, and while such procedures could affect gene expression, these variables were held constant between the different kinds of embryos being compared. The differences reported between BBB and BCB embryos thus are specifically associated with this difference in maternal pronucleus origin, though this might include genotype-dependent responses to these manipulations.

Although the number of affected genes is comparatively small, these genes potentially affect a wide array of key processes in the early embryo. Particularly significant effects (based on Ingenuity Pathway and EASE analysis) include effects on cell death, cell proliferation, mRNA processing and metabolism, RNA binding, gene transcription, adenylate cyclase intracellular signaling, and antigen presentation at the cell surface, and various metabolic pathways.

Some differentially expressed genes encode components of pathways that can affect apoptosis and/or cytoskeleton function, either of which could affect blastomere integrity and cytofragmentation. However, two of the genes most highly altered in our array analysis were Adcy2 and Pdgfrl. ADCY2 would affect cellular functions by elevating cAMP levels. We find that treatment with dbcAMP induces fragmentation, confirming a role for cAMP signaling in this process. Interestingly, there was a strain-dependent difference in sensitivity to dbcAMP treatment, with the embryos from C3H mothers showing much greater sensitivity than those from B6 mothers, consistent with a genetic predisposition to undergo fragmentation. Our data indicate that cAMP signaling induces fragmentation in embryos from C3H mothers by activating EPACs. The EPAC activator strongly induced fragmentation in embryos from C3H mothers but not B6 mothers. We excluded PIK3 signaling as a mediator of EPAC-activated fragmentation, because PIK3 signaling opposed fragmentation. This implicates other mediators, possibly RAP or other Ras-like small GTPases. Additionally, the AKAPs oppose fragmentation in both strains, because treatment with st-Ht31 elevated the rate of fragmentation. The inability of the PKA-specific activator N6-benzoyl-cAMP to affect fragmentation rate indicates that the dbcAMP effect mostly likely occurs via a pathway independent from PKA, again implicating the EPAC pathway. PKA may normally oppose the profragmentation effects of EPACs via AKAPs, and in other systems, AKAPs coordinate opposing effects of PKA and EPACs (16, 38, 43). There was also a strain-specific effect of combining st-Ht31 with dbcAMP treatment, wherein this combination yielded a low rate of fragmentation in embryos from B6 mothers. This suggests that AKAPs may interact with a different array of proteins (PKA, EPACs, phosphodiesterases, and phosphatases) in embryos of the two strains, or that the expression or activities of these proteins may vary by strain.

In other systems, EPACs regulate a range of cellular reorganization processes involving cytoskeleton remodeling, such as chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and endothelial cell barrier formation (16, 43). EPACs undergo dynamic redistribution during the cell cycle, including relocalization to the zone of incipient contractile ring formation during M-phase (40). EPACs can occupy protein complexes along with PKA, AKAPs, phosphodiesterases, small GTPases, and other signaling components, and these complexes can be recruited to the cytoskeleton in a controlled manner (16, 40). We propose that at least two opposing signaling systems are responsible for regulating EPAC functions, and their propensity to direct cleavage-like reorganizations of the cytoskeleton. We propose that incorrect regulation of EPACs or failure to oppose their actions leads to fragmentation by activating cleavage-like activities in the cortical cytoskeleton. AKAPs and PKA may normally suppress fragmentation by stabilizing the cortical actin network. EPACs activate specific Ras-like small GTPases, such as RAP. These in turn promote cortical actin reorganization, most likely mediated by such factors as cofilin, the activity of which can be inhibited by PIK3 signaling via other small GTPases (e.g., LIMK). Another gene displaying a much higher expression in BCB than BBB embryos, Pdgfrl, may inhibit the PIK3 signaling pathway by suppressing upstream signaling from the PDGF receptor, which would create an interesting opportunity for autocrine and paracrine effects. Thus, a system of opposing signaling pathways may normally inhibit cytokinesis-like processes during interphase, but an imbalance in these pathways can arise, resulting in reduced AKAPs or PIK3 signaling or an increase in EPAC activity, and then uncontrolled cytokinesis, and cytofragmentation. The ease with which this balance is disrupted is sensitive to genetic differences in expression of key regulators, in this case most notably ADCY2. Genetic differences in the expression of components of this system would increase or decrease sensitivity to environmental factors, including stress in vitro, and such genetic differences may contribute to cytofragmentation in human assisted reproduction. Further study of the specific signaling pathways and the genes involved should thus be of great value in understanding, anticipating, and controlling this process clinically. Moreover, because EPACs, AKAPs and the PIK3 pathway affect so many cellular processes, their continued study in the early embryo is likely to shed new light on the mechanisms controlling a range of cellular processes.

The ability to trigger severe cytofragmentation and elicit caspase activation via dbcAMP treatment also indicates that severe cytofragmentation can be accompanied by apoptotic processes within the cell. We previously observed no evidence for effects on DNA (negative TUNEL reactions) (21). The data presented here indicate that apoptosis is likely activated with only a subset of the normal array of cellular changes observed in somatic cells. This most likely reflects a deficiency of certain mediators, such as the caspase-activated DNAse at this early stage. Moreover, our data cast doubt on the simplistic explanation that cytofragmentation is merely a consequence of apoptosis in the early embryo. Rather, our data indicate that apoptosis may only be activated in parallel to fragmentation, possibly through disruption in PIK3/Akt signaling, a pathway in which several components displayed alterations in mRNA expression on our arrays. Moreover, cytofragmentation may arise independently of apoptosis, perhaps in response to cellular stressors that affect these signaling pathways.

The differential expression of MHC complex genes, including H2-Q8 (the most highly overexpressed gene in BBB embryos relative to BCB embryos) could affect embryo developmental potential. The Ped gene, a class Ib MHC component called the Qa-2 antigen (a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked cell surface protein encoded in the Q region of the mouse MHC), is associated with enhanced cleavage rate, larger blastocyst cell numbers, and greater midgestation survival (34, 48, 53–56). Previous reports concluded that the Ped phenotype is directed by the Q7 or Q9 genes, because Q6 and Q8 expression was undetected by RT-PCR (58, 59). Our data indicate that the expression of H2-Q8 is low but detectable on arrays, leaving open the possibility that this gene may affect early cleavage rate.

Another category of effects revealed in the lists of affected genes relates to mRNA processing, RNA binding, and metabolism. Differential regulation of maternal or embryonic mRNAs by the differential expression of these proteins could arise. With respect to maternal mRNAs, our analysis revealed six mRNAs that were α-amanitin insensitive but differentially expressed depending on mPN strain of origin. The existence of even a small number of such mRNAs indicates that maternal mRNA regulation may be affected by the mPN. The differences in expression were quite modest, and, overall, there is no evidence for a widespread effect of the mPN on the maternal mRNA population. However, effects on the synthesis, processing, and stability of embryonic transcripts remain a possibility.

Our data do not yet offer an explanation for the predominant effect of the mPN on the cytofragmentation phenotype. Such a difference is suggestive of an effect of genomic imprinting; however, none of the differentially expressed genes is known to be affected by genomic imprinting, and none of the genes tested displayed significant differences in expression related to parental origin of the C3H genome or between C3H androgenones and gynogenones. Whether some of the other genes are imprinted but lose their imprints soon after the two-cell stage, or whether some other differences in chromatin state inherited from the gametes or acquired after fertilization in some way differentially affect maternal and paternal chromosome function remains to be determined. Earlier studies indicated that the pPN undergoes preferential global demethylation and preferential acquisition of acetylated histones (1, 44, 45). Such changes would typically be associated with enhanced transcription, but because in the case of cytofragmentation it is the maternally inherited genome that dominates in controlling cytofragmentation, it is not immediately clear how either of these differences could contribute to the observed effects of the maternal genome on phenotype or gene transcription. Differences in gene expression not detected by conventional array analysis (e.g., small RNAs) could contribute to the mPN effect on phenotype.

Our studies began with an array analysis based on embryos produced by maternal pronuclear transfer. Those studies implicated specific molecules and pathways that could control cytofragmentation. Subsequent studies employing embryos not produced by pronuclear transfer indicated that the cytofragmentation process is indeed regulated by these pathways and that this regulation is subject to maternal genetic variation. This result gives greater emphasis to the importance of understanding how maternal genotype affects both ooplasm composition and early embryonic gene transcription. Our results provide a novel foundation for future studies to evaluate the mechanisms by which polymorphisms in specific genes affect embryonic phenotype. Our data identify the Adcy2, Pdgfrl, and Brunol4 genes as having qualitatively different expression depending on whether the gene is of C3H or B6 origin. An examination of the cis- and trans-regulators of these genes and how they function in different cell types should reveal polymorphisms to account for differences in gene regulation in the early embryo, and whether that regulation is embryo specific. Such studies should enhance our understanding of the specific factors that control early development.

Also of interest is the differential expression of a large number of genes related to specific diseases and genetic disorders, including arthritis, diabetes, Hurler's syndrome, and cardiovascular disease. These data suggest that the B6 and C3H mouse strains may provide useful genetic tools for understanding the development of these complex diseases.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD41440) and National Center for Research Resources (RR18907).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Hua Pan for advice on array data analysis.

Present address of R. Vassena: Stem Cell Bank CMR[B] Av. Dr. Aiguader 88, Barcelona, E-08003, Spain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adenot PG, Mercier Y, Renard JP, Thompson EM. Differential H4 acetylation of paternal and maternal chromatin precedes DNA replication and differential transcriptional activity in pronuclei of 1-cell mouse embryos. Development 124: 4615–4625, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alikani M, Calderon G, Tomkin G, Garrisi J, Kokot M, Cohen J. Cleavage anomalies in early human embryo and survival after prolonged culture in vitro. Hum Reprod 15: 2634–2643, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antczak M, Van Blerkom J. Temporal and spatial aspects of fragmentation in early human embryos: possible effects on developmental competence and association with the differential elimination of regulatory proteins from polarized domains. Hum Reprod 14: 429–447, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedaiwy MA, Falcone T, Mohamed MS, Aleem AA, Sharma RK, Worley SE, Thornton J, Agarwal A. Differential growth of human embryos in vitro: role of reactive oxygen species. Fertil Steril 82: 593–600, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergeron L, Perez GI, Macdonald G, Shi L, Sun Y, Jurisicova A, Varmuza S, Latham KE, Flaws JA, Salter JC, Hara H, Moskowitz MA, Li E, Greenberg A, Tilly JL, Yuan J. Defects in regulation of apoptosis in caspase-2-deficient mice. Genes Dev 12: 1304–1314, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brewster JL, Martin SL, Toms J, Goss D, Wang K, Zachrone K, Davis A, Carlson G, Hood L, Coffin JD. Deletion of Dad1 in mice induces an apoptosis-associated embryonic death. Genesis 2: 271–278, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byrne AT, Southgate J, Brison DR, Leese HJ. Analysis of apoptosis in the preimplantation bovine embryo using TUNEL. J Reprod Fertil 117: 97–105, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatot CL, Ziomek CA, Bavister BD, Lewis JL, Torres I. An improved culture medium supports development of random-bred 1-cell mouse embryos in vitro. J Reprod Fertil 86: 679–688, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Check JH, Summers-Chase D, Yuan W, Horwath D, Wilson C. Effect of embryo quality on pregnancy outcome following single embryo transfer in women with a diminished egg reserve. Fertil Steril 87: 749–756, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen HW, Jiang WS, Tzeng CR. Nitric oxide as a regulator in preimplantation embryo development and apoptosis. Fertil Steril 75: 1163–1171, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chi MM, Hoehn A, Moley KH. Metabolic changes in the glucose-induced apoptotic blastocyst suggest alterations in mitochondrial physiology. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 283: E226–E232, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooke S, Quinn P, Kime L, Ayres C, Tyler JP, Driscoll GL. Improvement in early human embryo development using new formulation sequential stage-specific culture media. Fertil Steril 78: 1254–1260, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diamond MP, Pettway ZY, Logan J, Moley K, Vaughn W, DeCherney AH. Dose-response effects of glucose, insulin, and glucagon on mouse pre-embryo development. Metabolism 40: 566–570, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fauque P, Leandri R, Merlet F, Juillard JC, Epelboin S, Guibert J, Jouannet P, Patrat C. Pregnancy outcome and live birth after IVF and ICSI according to embryo quality. J Assist Reprod Genet 24: 159–165, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giorgetti C, Terriou P, Auquier P, Hans E, Spach JL, Salzmann J, Roulier R. Embryo score to predict implantation after in-vitro fertilization: based on 957 single embryo transfers. Hum Reprod 10: 2427–2431, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grandoch M, Roscioni SS, Schmidt M. The role of Epac proteins, novel cAMP mediators, in the regulation of immune, lung, and neuronal function. Br J Pharmacol 159: 265–284, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han Z, Chung YG, Gao S, Latham KE. Maternal factors controlling blastomere fragmentation in early mouse embryos. Biol Reprod 72: 612–618, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han Z, Mtango NR, Patel BG, Sapienza C, Latham KE. Hybrid vigor and transgenerational epigenetic effects on early mouse embryo phenotype. Biol Reprod 79: 638–648, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardy K, Spanos S, Becker D, Iannelli P, Winston RM, Stark J. From cell death to embryo arrest: mathematical models of human preimplantation embryo development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 1655–1660, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hardy K. Apoptosis in the human embryo. Rev Reprod 4: 125–134, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawes SM, Chung YG, Latham KE. Genetic and epigenetic factors affecting blastomere fragmentation in preimplantation stage mouse embryos. Biol Reprod 65: 1050–1056, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hesters L, Prisant N, Fanchin R, Mendez Lozano DH, Feyereisen E, Frydman R, Tachdjian G, Frydman N. Impact of early cleaved zygote morphology on embryo development and in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer outcome: a prospective study. Fertil Steril 89: 1677–1684, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hourvitz A, Lerner-Geva L, Elizur SE, Baum M, Levron J, David B, Meirow D, Yaron R, Dor J. Role of embryo quality in predicting early pregnancy loss following assisted reproductive technology. Reprod Biomed Online 13: 504–509, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jurisicova A, Latham KE, Casper RF, Varmuza SL. Expression and regulation of genes associated with cell death during murine preimplantation embryo development. Mol Reprod Dev 51: 243–253, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jurisicova A, Rogers I, Fasciani A, Casper RF, Varmuza SL. Effect of maternal age and conditions of fertilization on programmed cell death during murine preimplantation embryo development. Mol Hum Reprod 4: 139–145, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jurisicova A, Varmuza S, Casper RF. Involvement of programmed cell death in preimplantation embryo demise. Hum Reprod Update 1: 558–566, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jurisicova A, Varmuza S, Casper RF. Programmed cell death and human embryo fragmentation. Mol Hum Reprod 2: 93–98, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keim AL, Chi MM, Moley KH. Hyperglycemia-induced apoptotic cell death in the mouse blastocyst is dependent on expression of p53. Mol Reprod Dev 60: 214–224, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keltz MD, Skorupski JC, Bradley K, Stein D. Predictors of embryo fragmentation and outcome after fragment removal in in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril 86: 321–324, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu L, Trimarchi JR, Keefe DL. Involvement of mitochondria in oxidative stress-induced cell death in mouse zygotes. Biol Reprod 62: 1745–1753, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luedi PP, Hartemink AJ, Jirtle RL. Genome-wide prediction of imprinted murine genes. Genome Res 15: 875–884, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matwee C, Betts DH, King WA. Apoptosis in the early bovine embryo. Zygote 8: 57–68, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McElhinny AS, Kadow N, Warner CM. The expression pattern of the Qa-2 antigen in mouse preimplantation embryos and its correlation with the Ped gene phenotype. Mol Hum Reprod 4: 966–971, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moley KH, Chi MM, Knudson CM, Korsmeyer SJ, Mueckler MM. Hyperglycemia induces apoptosis in pre-implantation embryos through cell death effector pathways. Nat Med 4: 1421–1424, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moley KH, Vaughn WK, DeCherney AH, Diamond MP. Effect of diabetes mellitus on mouse pre-implantation embryo development. J Reprod Fertil 93: 325–332, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mtango NR, Potireddy S, Latham KE. Oocyte quality and maternal control of development. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 268: 223–290, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nijholt IM, Dolga AM, Ostraveanu A, Luiten PG, Schmidt M, Elsel UL. Neuronal AKAP150 coordinates PKA and Epac-mediated PKB/Akt phosphorylation. Cell Signal 20: 1715–1724, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Otoi T, Yamamoto K, Horikita N, Tachikawa S, Suzuki T. Relationship between dead cells and DNA fragmentation in bovine embryos produced in vitro and stored at 4 degrees C. Mol Reprod Dev 54: 342–347, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qiao J, Mei FC, Popov VL, Vergara LA, Cheng Z. Cell cycle-dependent subcellular localization of exchange factor directly activated by cAMP. J Biol Chem 277: 26581–26586, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riley JK, Carayannopoulos MO, Wyman AH, Chi M, Moley KH. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity is critical for glucose metabolism and embryo survival in murine blastocysts. J Biol Chem 281: 6010–6019, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riley JK, Carayannopoulos MO, Wyman AH, Chi M, Ratajczak CK, Moley KH. The PI3K/Akt pathway is present and functional in the preimplantation mouse embryo. Dev Biol 284: 377–386, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roscioni SS, Elzinga CRS, Schmidt M. Epac: effectors and biological functions. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 377: 345–357, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santos F, Hendrich B, Reik W, Dean W. Dynamic reprogramming of DNA methylation in the early mouse embryo. Dev Biol 241: 172–82, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Santos F, Peters AH, Otte AP, Reik W, Dean W. Dynamic chromatin modifications characterise the first cell cycle in mouse embryos. Dev Biol 280: 225–36, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spanos S, Rice S, Karagiannis P, Taylor D, Becker DL, Winston RM, Hardy K. Caspase activity and expression of cell death genes during development of human preimplantation embryos. Reproduction 124: 353–363, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Summers-Chase D, Check JH, Swenson K, Yuan W, Brittingham D, Barci H. A comparison of in vitro fertilization outcome by culture media used for developing cleavage-stage embryos. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 31: 179–182, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tian Z, Xu Y, Warner CM. Removal of Qa-2 antigen alters the Ped gene phenotype of preimplantation mouse embryos. Biol Reprod 47: 271–276, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 5116–5121, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van Blerkom J, Davis PW. DNA strand break and phosphatidylserine redistribution in newly ovulated cultured mouse and human oocytes: occurrence and relationship to apoptosis. Hum Reprod 13: 1317–1324, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vassena R, Han Z, Gao S, Baldwin DA, Schultz RM, Latham KE. Tough beginnings: alterations in the transcriptome of cloned embryos during the first two cell cycles. Dev Biol 304: 75–89, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vergouw CG, Botros LL, Roos P, Lens JW, Schats R, Hompes PG, Burns DH, Lambalk CB. Metabolomic profiling by near-infrared spectroscopy as a tool to assess embryo viability: a novel, non-invasive method for embryo selection. Hum Reprod 23: 1499–1504, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Warner CM, Brownell MS, Rothschild MF. Analysis of litter size and weight in mice differing in Ped gene phenotype and the Q region of the H-2 complex. J Reprod Immunol 19: 303–313, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Warner CM, Exley GE, McElhinny AS, Tang C. Genetic regulation of preimplantation mouse embryo survival. J Exp Zool 282: 272–279, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Warner CM, McElhinny AS, Wu L, Cieluch C, Ke X, Cao W, Tang C, Exley GE. Role of the Ped gene and apoptosis genes in control of preimplantation development. J Assist Reprod Genet 15: 331–337, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Warner CM, Panda P, Almquist CD, Xu Y. Preferential survival of mice expressing the Qa-2 antigen. J Reprod Fertil 99: 145–147, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watson AJ, De Sousa P, Caveney A, Barcroft LC, Natale D, Urquhart J, Westhusin ME. Impact of bovine oocyte maturation media on oocyte transcript levels, blastocyst development, cell number, and apoptosis. Biol Reprod 62: 355–364, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu L, Exley GE, Warner CM. Differential expression of Ped gene candidates in preimplantation mouse embryos. Biol Reprod 59: 941–952, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu L, Feng H, Warner CM. Identification of two major histocompatibility complex class Ib genes, Q7 and Q9, as the Ped gene in the mouse. Biol Reprod 60: 1114–1119, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu JS, Cheung TM, Chan ST, Ho PC, Yeung WS. Human oviductal cells reduce the incidence of apoptosis in cocultured mouse embryos. Fertil Steril 74: 1215–1219, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoshida N, Perry AC. Piezo-actuated mouse intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). Nat Protoc 2: 296–304, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.