Abstract

Most fungal effectors characterized so far are species-specific and facilitate virulence on a particular host plant. During infection of its host tomato, Cladosporium fulvum secretes effectors that function as virulence factors in the absence of cognate Cf resistance proteins and induce effector-triggered immunity in their presence. Here we show that homologs of the C. fulvum Avr4 and Ecp2 effectors are present in other pathogenic fungi of the Dothideomycete class, including Mycosphaerella fijiensis, the causal agent of black Sigatoka disease of banana. We demonstrate that the Avr4 homolog of M. fijiensis is a functional ortholog of C. fulvum Avr4 that protects fungal cell walls against hydrolysis by plant chitinases through binding to chitin and, despite the low overall sequence homology, triggers a Cf-4-mediated hypersensitive response (HR) in tomato. Furthermore, three homologs of C. fulvum Ecp2 are found in M. fijiensis, one of which induces different levels of necrosis or HR in tomato lines that lack or contain a putative cognate Cf-Ecp2 protein, respectively. In contrast to Avr4, which acts as a defensive virulence factor, M. fijiensis Ecp2 likely promotes virulence by interacting with a putative host target causing host cell necrosis, whereas Cf-Ecp2 could possibly guard the virulence target of Ecp2 and trigger a Cf-Ecp2-mediated HR. Overall our data suggest that Avr4 and Ecp2 represent core effectors that are collectively recognized by single cognate Cf-proteins. Transfer of these Cf genes to plant species that are attacked by fungi containing these cognate core effectors provides unique ways for breeding disease-resistant crops.

Keywords: Cladosporium fulvum, Mycosphaerella fijiensis, effector-triggered immunity, biotrophy, toxigenic peptides

Cladosporium fulvum is a nonobligate biotrophic fungus that causes leaf mold of tomato (Solanum esculentum). The interaction between C. fulvum and tomato has become a model for studies on plant–pathogen interactions that comply with the gene-for-gene system (1). During infection of tomato, C. fulvum secretes effector proteins into the apoplast, which act as virulence factors. However, these effectors (previously called avirulence or Avr factors) are also recognized by cognate C. fulvum (Cf) resistance proteins in resistant tomato lines, leading to rapid elicitation of plant defense responses that culminate in the hypersensitive response (HR), a type of programmed cell death that prevents further growth of the fungus (2, 3). Tomato Cf resistance (R) proteins are members of a distinct class of R proteins that are collectively called receptor-like proteins (RLPs) (2, 3). To date, four avirulence (Avr) genes have been cloned from C. fulvum, and they all encode small cysteine-rich proteins that are secreted during infection. They are the Avr2, Avr4, Avr4E, and Avr9 effector proteins, whose recognition in tomato is mediated by the cognate Cf proteins Cf-2, Cf-4, Cf-4E, and Cf-9, respectively (1, 2). An additional set of six extracellular proteins (Ecps), namely Ecp1, Ecp2, Ecp4, Ecp5, Ecp6, and Ecp7, has been characterized from C. fulvum that invoke an HR in tomato lines carrying a cognate Cf-Ecp resistance trait. All Avrs and Ecps are assumed to be virulence factors, but so far, the intrinsic functions of only Avr2, Avr4, and Ecp6, have been elucidated (1, 2). In particular, Avr4 was shown to be a chitin-binding lectin, which protects fungal cell walls against hydrolysis by basic plant chitinases (4). Consequently, knocking down of Avr4 in C. fulvum decreases virulence of the fungus (5). Ecp2 is also a virulence factor, as deletion of the encoding gene reduces virulence of C. fulvum (6). However, the intrinsic function of Ecp2 has not yet been elucidated (6). In tomato, the ability to recognize Ecp2 and to invoke an HR is mediated by a single dominant gene, termed Cf-Ecp2, that originates from the wild tomato species Solanum pimpinellifolium. Cf-Ecp2 has been mapped on the Orion locus on the short arm of chromosome 1 and its cloning is underway (7).

Our current understanding of plant disease resistance is summarized in the “zigzag” model proposed by Jones and Dangl (2006) (8). This model suggests that recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) is mediated by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) to induce PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI). As a result of coevolution between a host and its pathogen, the latter has evolved effectors that suppress PTI; in response, host plants have evolved R proteins that recognize cognate effectors and mediate effector-triggered immunity (ETI). So far, most fungal effectors appear to be species-specific that facilitate virulence on a particular host species (2). We challenged this concept by examining whether homologous fungal effector proteins could exist across species boundaries with conserved biological functions that could facilitate virulence on distantly related host species. Occurrence of such “core” effectors would support the hypothesis of divergent effector-based evolution of fungal plant pathogens. Along the same lines, it could be envisaged that plants have evolved cognate R proteins that can mediate recognition of core effectors from different pathogens and initiate ETI.

Here we provide evidence for the existence of homologous effectors in species of Dothideomycetes that are pathogenic on distantly related monocots and dicots (9). In particular, we have identified functional homologs of the C. fulvum Avr4 and/or Ecp2 effectors in Mycosphaerella fijiensis, causal agent of the devastating black Sigatoka disease of banana (10) and other phylogenetically related pathogens. We further demonstrate that the M. fijiensis Avr4 is a functional ortholog of the C. fulvum Avr4 that triggers Cf-4- and Hcr9-Avr4-mediated HR in tomato. Three homologs of Ecp2 were identified in M. fijiensis, one of which induces an HR in a Cf-Ecp2 tomato line. Collectively our data suggest that Avr4 and Ecp2 represent core effectors with conserved domains that are recognized by single cognate Cf proteins. The presence of homologous effectors in fungal pathogens that are collectively recognized by a single RLP provides leads for disease resistance breeding by transferring such an RLP into distantly related plant species.

Results

Homologs of C. fulvum Effectors Are Present in Species of Dothideomycetes.

We queried the publicly available genome sequences of five Dothideomycete species, namely Mycosphaerella fijiensis, Mycosphaerella graminicola, Stagonospora nodorum, Pyrenophora tritici-repentis, and Alternaria brassicicola, available at the website of the DOE Joint Genome Institute of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE; http://www.jgi.doe.gov/), for the presence of C. fulvum Avr- and Ecp-like proteins, using BlastP. Blast hits with a cut-off E-value of 1e−4 were considered as significant and were used for further analyses.

Avr4 Homologs.

Query of the S. nodorum, P. tritici-repentis, and A. brassicicola genome sequences with the Avr and Ecp protein sequences of C. fulvum produced no significant hits. However, query of the genomic sequence of M. fijiensis produced a single hit (Protein ID: Mycfi1:87167; renamed MfAvr4) for C. fulvum Avr4 (Avr4) with 42% identity at the protein level (Fig. S1 A and C and Table S1). MfAvr4 is a protein of 121 amino acids (aa), consisting of a putative N-terminal signal peptide (SP) of 21 aa and a mature part that harbors a chitin-binding Peritrophin-A domain (InterPro ID: IPR002557). High similarity between Avr4 and MfAvr4 was found within this domain (Fig. S1C). Ten cysteine (Cys) residues are present in MfAvr4, and positioning and spacing of eight Cys residues are similar to the pattern observed in Avr4, suggesting a similar disulfide bonding pattern and structural homology between the two proteins (11). The other two Cys residues at the C terminus of MfAvr4 might be involved in an additional disulfide bond. Using a PCR-based approach, we also identified homologs of Avr4 in the Cercospora species C. beticola, C. nicotianae, C. apii, and C. zeina. These species were selected based on their phylogenetic relationship to C. fulvum, supported, among others, by the presence of highly homologous mating-type genes (12). The Avr4 homologs identified in the Cercospora species share high sequence similarity with each other, both at the nucleotide (93.1–99.8%) and protein (95.6–99.3%) level (Fig. S1 A and C and Table S1). Protein identity between the Cercospora Avr4 homologs and C. fulvum Avr4 was between 30 and 32%, which is lower than the identity levels between Avr4 and MfAvr4 (42%) (Table S1). This difference corresponds to the larger phylogenetic distance between the Cercospora species and C. fulvum, as compared to the phylogenetic distance between M. fijiensis and C. fulvum. All putative Avr4 homologs from the four Cercospora species are predicted to have an N-terminal SP of 19 aa, followed by a 116 aa (C. beticola, C. apii) or a 115 aa (C. nicotianae, C. zeina) mature protein that contains a chitin-binding Peritrophin-A domain (InterPro ID: IPR002557). Highest levels of similarity between Avr4 and the Cercospora Avr4 homologs were found within this chitin-binding domain (Fig. S1C). The eight Cys residues present in C. fulvum Avr4 are also conserved in all Cercospora Avr4 homologs. However, the Cercospora Avr4 homologs contain one additional Cys residue, located behind a proline-alanine-rich repeat region of 23 aa at the C terminus (Fig. S1C). This repeat region might be removed upon secretion of the protein into the apoplast and subsequent maturation, as has also been reported for the C-terminal 20 aa of Avr4 (13).

Ecp2 Homologs.

In addition- to Avr4, three proteins were identified in the genome of M. fijiensis that showed homology to C. fulvum Ecp2 (Ecp2) (Fig. S1B and Table S2). The M. fijiensis Ecp2 protein (Protein ID: Mycfi1:60658; renamed MfEcp2) most homologous to Ecp2 (57% identity), contains 161 aa and has a predicted SP of 19 aa. The other two putative M. fijiensis Ecp2 homologs are 28% (Protein ID: Mycfi1:23545; renamed MfEcp2-2) and 25% (Protein ID: Mycfi1:52972; renamed MfEcp2-3) identical to Ecp2 and contain 174 aa and 236 aa, with putative N-terminal SPs of 19 aa and 18 aa, respectively. Structural comparison of Ecp2 and all three MfEcp2s showed conservation of four Cys residues and an intron in the encoding genes. The intron is present at almost identical positions in Ecp2 and the three MfEcp2s, spanning the nucleotide triplet encoding the third conserved Cys residue (Fig. S1B). This suggests a common evolutionary origin for the Ecp2 genes, as independent identical positions of introns are unlikely to have occurred. The presence of the intron in the three MfEcp2s was confirmed in publicly available EST sequence data for M. fijiensis and by in-house sequencing of PCR-amplified cDNA clones. Query of the M. graminicola genome also identified three Cys-rich proteins with homology to Ecp2 and MfEcp2 (Fig. S1B and Table S2). The M. graminicola Ecp2 protein (Protein ID: Mycgr:104404; renamed MgEcp2) most homologous to Ecp2 (30% identity) and MfEcp2 (32% identity), contains 179 aa and has a predicted SP of 19 aa. Again, the four Cys residues and the location of the exon-intron boundaries in the encoding gene are also preserved in MgEcp2. The other two Ecp2 homologs present in M. graminicola are 29% (Protein ID: Mycgr3:107904, renamed MgEcp2-2) and 26% (Protein ID: Mycgr3:111636, renamed MgEcp2-3) identical to Ecp2 and contain 170 aa and 159 aa, respectively, both with putative SPs of 21 aa. The four conserved Cys residues present in Ecp2 and MfEcp2 are also present in MgEcp2-2 and MgEcp2-3, but both their encoding genes lack introns based on EST sequence data publicly available for M. graminicola. Phylogenetic analysis showed clustering of Ecp2, MfEcp2, and MgEcp2 based on orthology rather than paralogy, suggesting inheritance from a common ancestor in which gene duplication has occurred before speciation (Fig. S1B).

M. fijiensis Avr4 Binds to Chitin and Protects Fungi Against Plant Chitinases.

We previously showed that Avr4 binds specifically to chitin (4). Hence, we examined whether MfAvr4 also shows affinity for chitin, using the same affinity precipitation assay. Indeed, MfAvr4 showed specific affinity for chitin as it coprecipitated with insoluble chitin, such as crab-shell chitin and chitin-agarose resin, but not with the other insoluble polysaccharides tested, indicating that MfAvr4 contains a functional chitin-binding domain (Fig. S2A). Subsequently, we tested in vitro whether MfAvr4 was able to protect fungal cell walls against hydrolysis by plant chitinases, as has been reported for Avr4 (4). For this purpose, plant chitinases were isolated from leaves of transgenic tomato plants overexpressing basic chitinases targeted to the apoplast. The lytic activity of the chitinase fraction was tested against Trichoderma viride, as growth of this fungus is known to be strongly inhibited by chitinases alone (4). Addition of sublethal doses of the chitinase fraction to overnight pregerminated germlings of T. viride inhibited mycelial growth. In contrast, combined application of the chitinase fraction and 3.75 or 7.5 μg of MfAvr4 resulted in full protection of the germlings against chitinases, as no visible growth inhibition could be observed (Fig. S2B). Growth of T. viride germlings was not affected by adding 3.75 or 7.5 μg of MfAvr4 alone. These observations indicate that MfAvr4 is a functional ortholog of Avr4 that binds to chitin and protects fungal cell walls against lytic activity of plant chitinases.

The M. fijiensis Avr4 Triggers a Cf-4–Mediated HR.

Previously we reported that Avr4 triggers a Cf-4–mediated HR (13). We examined whether MfAvr4, which is a functional chitin-binding lectin but shows only 42% identity to Avr4, also triggers a Cf-4–mediated HR. Therefore, we used the Potato Virus X (PVX)–based expression system to systemically deliver MfAvr4 into tomato. Inoculation of the near-isogenic Cf-0 and Cf-4 tomato lines of cv. MoneyMaker (MM) with the empty PVX-based binary vector pSfinx resulted in systemic mosaic symptoms commonly seen after PVX infection. However, inoculation of tomato with PVX::MfAvr4 resulted in induction of a strong and systemic HR in the MM-Cf-4 line, whereas only mosaic symptoms were observed in the MM-Cf-0 line. As expected, inoculation of the two lines with PVX::Avr4 resulted in an HR only in the MM-Cf-4 line and mosaic symptoms in the MM-Cf-0 line. These results indicate specific recognition of Avr4 and MfAvr4 by the Cf-4 resistance protein (Fig. 1A). However, although both Avr4 and MfAvr4 are able to trigger Cf-4–mediated HR, the responses were quantitatively different with Avr4 inducing a stronger and more rapid HR compared with MfAvr4. Nevertheless, in both cases, the inoculated MM-Cf-4 plants eventually became completely necrotic 2 to 3 weeks after the first appearance of symptoms (Fig. 1A). Inoculation of MM-Cf-4 and MM-Cf-0 tomato lines with PVX::CnAvr4 (C. nicotianae Avr4) and PVX::CbAvr4 (C. beticola Avr4) caused only mosaic symptoms (Fig. S3A).

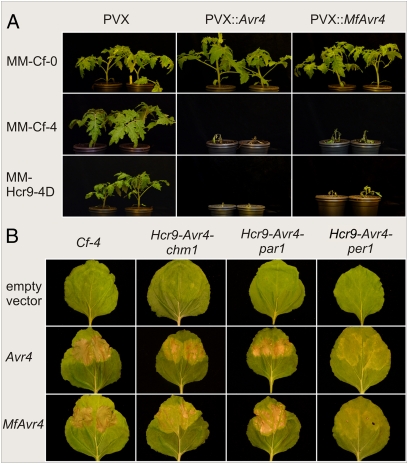

Fig. 1.

The Mycosphaerella fijiensis Avr4 (MfAvr4) triggers a Cf-4– and Hcr9-Avr4–mediated hypersensitive response (HR). (A) Specific induction of HR by MfAvr4 in a MM-Cf-4 and a MM-Hcr9-4D tomato line transgenic for 35S::Hcr9-4D. Tomato plants were inoculated with Agrobacterium tumefaciens transformants expressing PVX::MfAvr4. HR was induced only in MM-Cf-4 and the MM-Hcr9-4D transgenic tomato line but not in the MM-Cf-0 line. As controls, the empty binary vector pSfinx (PVX) and the C. fulvum Avr4 (PVX::Avr4) were used. As expected, inoculation with PVX::Avr4 resulted in an HR only in MM-Cf-4 and the MM-Hcr9-4D transgenic tomato. Only mosaic symptoms caused by PVX were observed after inoculation of the three lines with the empty pSfinx vector. Photographs were taken 20 days post-inoculation. (B) Transient coexpression of Cf-4 and the Avr4 homologs from C. fulvum and M. fijiensis, in Nicotiana benthamiana by the Agrobacterium tumefaciens transient transformation assay (ATTA). For ATTAs, A. tumefaciens cultures were mixed in a 1:1 ratio and infiltrated in leaves of N. benthamiana plants. Coexpression of MfAvr4 and tomato Cf-4 or the Hcr9-Avr4 homologs from Solanum chmielewskii (Hcr9-Avr4-chm1), S. parviflorum (Hcr9-Avr4-par1), and S. peruvianum (Hcr9-Avr4-per1) results in HR in N. benthamiana leaves. As positive controls, C. fulvum Avr4 (Avr4) was coexpressed with Cf-4/Hcr9-Avr4s.

The Cf-4 locus in tomato contains a cluster of five homologous genes known as Hcr9-4s (for homologues of Cladosporium resistance gene Cf-9), of which Hcr9-4D is the genuine Cf-4 resistance gene that mediates recognition of Avr4 (14). To confirm that Cf-4 (Hcr9-4D) and not any of the other Hcr9-4 homologs mediated recognition of MfAvr4, we inoculated MM-Cf-0 plants transformed with Hcr9-4D under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter (14). The phenotype of the PVX::MfAvr4-inoculated plants expressing the Hcr9-4D transgene was similar to that of the control MM-Cf-4 lines (Fig. 1A), confirming that Hcr9-4D mediates recognition of MfAvr4. In contrast, PVX::CbAvr4, PVX::CnAvr4 and the empty pSfinx binary vector induced only mosaic symptoms in the Hcr9-4D-transgene and the MM-Cf-4 control plants (Fig. S3A).

The specificity of interaction between Cf-4 and MfAvr4 was further confirmed by agroinfiltration experiments, where we transiently coexpressed Cf-4 and MfAvr4 in Nicotiana benthamiana, using the Agrobacterium tumefaciens transient transformation assay (ATTA) (Fig. 1B) (15). These experiments supported the results obtained previously using PVX-mediated expression confirming that Cf-4, and not another Hcr9-4 homolog, mediates recognition of MfAvr4.

Hcr9-Avr4 Genes from Wild Solanum Species also Mediate Recognition of M. fijiensis Avr4.

Cf-4 homologs, termed Hcr9-Avr4s, have been identified in the past by our research group in different wild Solanum (previously Lycopersicon) species, including S. chilense (Hcr9-Avr4-chl1), S. chmielewskii (Hcr9-Avr4-chm1), S. parviflorum (Hcr9-Avr4-par1), and S. peruvianum (Hcr9-Avr4-per1), the products of which mediate recognition of Avr4 (16). We tested whether the Hcr9-Avr4 homologs from S. chmielewskii, S. parviflorum, and S. peruvianum were also responsive to the M. fijiensis, C. beticola, and C. nicotianae Avr4 homologs, using ATTAs in N. benthamiana. These experiments showed that all three Hcr9-Avr4s tested responded in a similar way to Avr4 and MfAvr4, as Cf-4 (Fig. 1B). Indeed, coinfiltration of A. tumefaciens strains (mixed in a 1:1 ratio) expressing the gene pairs Hcr9-Avr4s and Avr4 or MfAvr4 resulted in the development of an HR only in the infiltrated leaf sectors. As reported earlier (16), the activity of Hcr9-Avr4-per1 was lower compared with Cf-4, since coexpression of Avr4 or MfAvr4 with Hcr9-Avr4-per1 induced less necrosis than coexpression with Cf-4. Also Hcr9-Avr4-chm1 was slightly less active than Cf-4, whereas the activity of Hcr9-Avr4-par1 was comparable to that of Cf-4. In contrast, none of the three Hcr9-Avr4 homologs tested was responsive toward the Avr4 homologs from C. beticola or C. nicotianae (Fig. S3B).

Necrosis- and HR-Associated Recognition of M. fijiensis Ecp2 in Tomato.

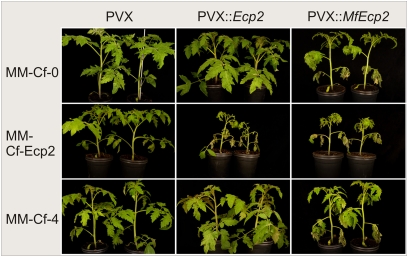

Ecp2 from C. fulvum induces a specific HR in tomato lines carrying the resistance gene Cf-Ecp2 (7). We used the PVX-expression system to test for induction of Cf-Ecp2-mediated HR by the three MfEcp2 homologs of M. fijiensis. Therefore, PVX-based constructs of the MfEcp2s were inoculated onto a near-isogenic MM-Cf-Ecp2 tomato line. Inoculation of PVX::MfEcp2 (M. fijiensis Ecp2) on 2-week-old MM-Cf-Ecp2 plants resulted in induction of a strong systemic HR, eventually leading to plant death (Fig. 2). These symptoms were comparable to those developed after inoculation with PVX::Ecp2 (C. fulvum Ecp2) on MM-Cf-Ecp2 tomato plants, although responses were quantitatively different, with PVX::Ecp2 causing faster and more severe systemic HR than PVX::MfEcp2. Strikingly, inoculations with PVX::MfEcp2 onto MM-Cf-0 and MM-Cf-4 plants also resulted in induction of necrosis, indicating that there was an additional factor other than Cf-Ecp2 that triggers necrosis. However, necrotic symptoms developed on the MM-Cf-0 and MM-Cf-4 plants after inoculation with PVX::MfEcp2 were less severe than those developed on the MM-Cf-Ecp2 line and did not lead to lethality. As expected (17), inoculations of MM-Cf-0 and MM-Cf-4 plants with PVX::Ecp2 induced only mosaic symptoms, typical for PVX infections. Finally, inoculations with PVX::MfEcp2-2 and PVX::MfEcp2-3 did not trigger HR or necrosis on any of the tomato lines tested, but induced only systemic mosaic symptoms typical for PVX infections (Fig. S4).

Fig. 2.

Induced hypersensitive response (HR) and necrosis in tomato after transient expression of the Mycosphaerella fijiensis Ecp2 homolog (MfEcp2), using the PVX-based expression system. Cotyledons of 2-week-old MM-Cf-Ecp2, MM-Cf-0, and MM-Cf-4 tomato plants were inoculated with Agrobacterium tumefaciens transformants expressing PVX::MfEcp2. As controls the empty binary vector pSfinx (PVX) and the C. fulvum Ecp2 (PVX::Ecp2) were used. Transient expression of MfEcp2 in MM-Cf-0 and MM-Cf-4 tomato lines resulted in induction of necrosis, while an additional HR is induced in the MM-Cf-Ecp2 line, as reflected by the higher level of necrosis. As expected, the PVX-based expression of C. fulvum Ecp2 (PVX::Ecp2) resulted in an HR only on the MM-Cf-Ecp2 line. Only mosaic symptoms caused by PVX were observed upon inoculations of the lines with the empty pSfinx vector. Photographs were taken 21 days post-inoculation.

Discussion

Avr4 and Ecp2 Effectors of C. fulvum Are Not Species-Specific.

Most fungal effectors reported so far appear to be species-specific (2). Until recently, this was also true for the Avrs and Ecps of C. fulvum with the exception of Ecp6, as orthologs of this effector occur in many different fungal species, mainly due to the presence of LysM–motifs. Lys-M domains are involved in carbohydrate binding, including chitin, and therefore Ecp6 is proposed to be a chitin-binding lectin (18, 19). However, the occurrence of homologous effectors has been described before for several bacteria and oomycetes, where their distribution within and across species suggests a basic role in virulence and host species- and cultivar-specificity (20–22). Analogous to what has been described for bacterial and oomycete pathogens, we can now distinguish three classes of fungal effectors based on their presence or absence in different species, using the C. fulvum effectors as an example. Indeed, some effectors like Ecp6 show a broad distribution among different pathogenic and nonpathogenic fungal species (18, 19), while Avr4 and Ecp2 appear to occur only in a particular class of fungal species (this paper). These two groups of fungal effector proteins could represent a core set of effectors that facilitate pathogenicity on a wide range of hosts by providing basic virulence functions. Their preservation across species could, among others, depend both on the importance of their intrinsic virulence functions and the conservation of their virulence targets in different host species. The third and largest group of C. fulvum Avr and Ecp effectors appears to be species-specific, which is the case for most fungal effectors identified so far (2). The latter group of effectors likely facilitates virulence on particular host species and derived cultivars, by interacting with virulence targets specific for these species and cultivars. This might also explain why, under selection pressure, patho-adaptation leads to jettison of the C. fulvum-specific effectors Avr2, Avr4E, and Avr9, whereas core effectors like Avr4 and Ecp2 remain present in all strains of the fungus (23).

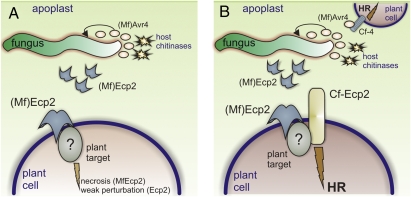

The data presented here for the Avr4 and Ecp2 homologs, in conjunction with data previously published by our laboratory (2), support the above proposed classification of fungal effectors in general and those of C. fulvum in particular. In this respect, it can be envisaged that chitin-binding lectins, such as Avr4 and Ecp6, have developed as core effectors during evolution of different fungal species [(18, 19) and this study], to provide protection against hydrolysis by plant chitinases. The intrinsic function of Ecp2 is still elusive, but it is likely that the necrosis induced by the M. fijiensis Ecp2 homolog in tomato reflects its original intrinsic virulence function. We assume that interaction of MfEcp2 with a common host virulence target present in different plant species leads to necrosis, which is important for the necrotrophic phase of hemibiotrophs, such as M. fijiensis (24). The conservation of the intron–exon boundaries in all Ecp2 homologs and their classification based on orthology rather than paralogy suggests inheritance from a common ancestral species. Therefore, Ecp2 might also represent a core effector gene that has been passed on by vertical descent and subsequently diverged after duplications and mutations into three homologs in M. fijiensis, M. graminicola and likely other pathogens as well. In future studies, we will extend our searches for the presence of homologous C. fulvum core effectors in sequenced genomes of fungi outside the class of Dothideomycetes.

Single Cf Proteins of Tomato Mediate Recognition of Cognate Homologous Effectors from Different Fungal Species.

Thus far, most of the R genes cloned from various plant species confer resistance to only a narrow range of isolates of a pathogen species by recognition of isolate-specific effectors. There are only a few examples of mainly NBS-LRR-containing R proteins that confer broad-spectrum resistance by mediating recognition of homologous effectors present in multiple pathogens (25, 26). Most R genes are arranged in clusters of homologs with different recognition specificities that could represent a reservoir of resistance specificities against different not yet identified pathogens (14, 16). Here we show that Cf proteins, such as Cf-4 and its functional Hcr9-Avr4 homologs from Solanum species, can mediate recognition of homologous Avr4 effectors from a fungus (C. fulvum) pathogenic on the dicot tomato and a fungus (M. fijiensis) pathogenic on the monocot banana. This suggests that a common domain present in the two homologous Avr4 effectors is recognized by Cf-4 and Hrc9-Avr4s. Currently, we are examining whether the surface-exposed residues important for chitin-binding present in this domain directly interact with these resistance proteins.

Resistance proteins can mediate effector recognition either directly or indirectly by monitoring perturbation of the effector's plant virulence targets (2, 8). We anticipate that direct interaction is expected to be effective against protective effectors with fungal targets, such as Avr4, which protects fungal cell walls against plant chitinases. Indeed, some preliminary evidence suggest a direct interaction between Cf-4 and Avr4, as expression of Avr4 in tomato does not induce significant alterations in expression of tomato genes (27). Furthermore, heterologous expression of the Avr4 homologs from C. fulvum and M. fijiensis in tomato and N. benthamiana lacking the Cf-4 gene did not result in any visible disease symptoms, suggesting that Avr4 is a defensive virulence factor, the primary function of which is to protect fungi against plant chitinases. Avr4 and its functional homolog from M. fijiensis only trigger an HR in tomato and N. benthamiana containing a functional Cf-4 or Hrc9-Avr4 protein. It is currently not known whether wild accessions of banana also contain functional Cf-4 or Hrc9-Avr4 homologs. If not, then transfer of the tomato Cf-4, Hcr9-Avr4-par1, Hrc9-Avr4-chm1 or Hrc9-Avr4-per1 genes to banana could possibly provide HR-based resistance to M. fijiensis. The same could be done by transferring these genes to other crop plants that are attacked by Dothideomycete fungi containing functional Avr4 homologs.

Ecp2 Homologs Present in Different Fungi Are Involved in Both Virulence and Avirulence.

The intrinsic biochemical function of C. fulvum Ecp2 is still unknown, but Ecp2 disruption mutants of the fungus are compromised in virulence (6). PVX-mediated expression of Ecp2 in MM-Cf-0 and MM-Cf-4 plants that lack the Cf-Ecp2 resistance protein did not cause necrosis, in strong contrast to MfEcp2, which caused Cf-Ecp2-independent necrosis. This suggests that MfEcp2 promotes virulence much stronger than the C. fulvum Ecp2, by interacting with a host virulence target that eventually leads to necrosis. These observations could reflect gradual differences in the virulence function of Ecp2 for the biotroph C. fulvum that relies mostly on living tissue for nutrition (28) and the hemibiotroph M. fijiensis that shows an initial biotrophic mode of nutrition followed by necrotrophy (24). It is possible that as a result of coevolution between C. fulvum and tomato, the C. fulvum Ecp2 has been fine-tuned either at the level of expression or at the level of affinity for the host target to facilitate its biotrophic lifestyle by only weakly perturbing the virulence target without inducing necrosis. This sophisticated way of retrieving nutrients from living host cells-that enables fungal growth without causing visible damage, differs from the hemibiotrophic lifestyle of M. fijiensis, where MfEcp2 induces strong necrosis. However, in the presence of the cognate Cf-Ecp2 protein, an additional HR leading to increased levels of necrosis is induced by the M. fijiensis Ecp2 effector. Therefore, we speculate that Cf-Ecp2 could guard the virulence target of Ecp2 in the host and trigger a Cf-Ecp2–mediated HR that is epistatic over virulence target-mediated necrosis, as suggested in the model presented in Fig. 3. Depending on the con-centrations of MfEcp2, its virulence target, and the Cf-Ecp2 receptor the overall outcome of the interaction could vary. We should consider that delivery of Ecp2 as tested here is artificial, and it is possible that under natural conditions the concentrations of the secreted Ecp2s are lower and that Cf-Ecp2–mediated HR is epistatic over virulence target-mediated necrosis. The situation described here shows similarities with previous studies, where effector proteins could act as enhancers of virulence in susceptible hosts and as inducers of host defense responses and resistance in plants containing cognate R genes. Examples include the NIP1 effector from Rhynchosporium secalis (29) and ToxA from P. tritici-repentis (30) and S. nodorum (31, 32). NIP1 is a necrosis-inducing peptide that functions both as a necrosis-inducing effector and an elicitor of defense responses in barley plants that carry the cognate Rrs1 resistance gene (33). Similar situations might hold for the necrotrophic fungi P. tritici-repentis and S. nodorum that also produce several necrosis-inducing peptides (34). Indeed, the toxigenic peptide ToxA of P. tritici-repentis (30) and several other toxigenic peptides (SnToxA, SnTox1, SnTox2, and SnTox3) of S. nodorum (31, 32) induce necrosis required for virulence on susceptible wheat cultivars that carry the dominant toxin sensitivity genes Tsn1, Snn1, Snn2, and Snn3, respectively (31, 32, 35). Likewise, MfEcp2 might have a function similar to ToxA of P. tritici-repentis and the toxigenic peptides of S. nodorum in enhancing virulence of the fungi on susceptible hosts by targeting a yet-unidentified host target that is guarded by the cognate Cf-Ecp2 protein in resistant cultivars.

Fig. 3.

Proposed functions for Ecp2 and Avr4. (A) In the absence of Cf resistance proteins, Ecp2 promotes virulence by interacting with an in planta target, causing host cell necrosis (indicated by the brown color of the host cell) that facilitates the necrotrophic mode of nutrition of hemibiotrophs, such as Mycosphaerella fijiensis. In case of biotrophs, such as Cladosporium fulvum coevolution between host and pathogen has fine-tuned Ecp2 to only weakly perturb the host cells without inducing cell necrosis. Avr4 is a defensive virulence factor, which interacts with fungal cell-wall chitin (indicated as an orange glow around the hyphae) to protect it against hydrolysis by host chitinases (4). (B) In the presence of cognate Cf resistance proteins, a hypersensitive response (HR) is induced that arrests fungal growth. In this model, we speculate that Cf-Ecp2 guards the virulence target of Ecp2 and triggers a Cf-Ecp2-mediated HR that is epistatic over virulence target-mediated necrosis. In contrast, Cf-4 presumably interacts directly with Avr4, and triggers an HR.

Materials and Methods

Identification of Effector Homologs in Dothideomycetes.

Genomic sequences of Dothideomycete species are available at the Joint Genome Institute (JGI) (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/). Inquiry of the genomes for C. fulvum effector homologs was done by BlastP, with an E-value of 1e−4. Homologs of Avr4 in Cercospora species were identified using PCR. Detailed information is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Fungal Strains and Plant Material.

Isolates used were M. fijiensis strain CIRAD86 (C86) from CIRAD culture collection, M. graminicola strain IPO323 and Cercospora species, C. beticola (CBS 116456), C. apii (CBS 116455), and C. zeina (CBS 118820), all obtained from CBS culture collection in Utrecht, the Netherlands. C. nicotianae was kindly provided by Margaret Daub, North Carolina State University (Raleigh, NC). Tomato lines used were cultivar MoneyMaker (MM) carrying no known Cf genes (referred to as MM-Cf-0), the near isogenic line MM-Cf-4, containing the Cf-4 cluster, breeding line Ontario-7518 carrying the Cf-Ecp2 resistance gene, and MM-Cf-0 transformed with Hcr9-4D (Cf-4) under control of the CaMV 35S promoter. Plants were grown in greenhouse conditions as described elsewhere (5). Detailed information is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Heterologous Expression of Effector Proteins in Planta.

We used the binary Potato Virus X (PVX)–based vector pSfinx for transient expression of foreign genes into plants (36). Recombinant viruses made were pSfinx::MfAvr4, pSfinx::CnAvr4, and pSfinx::CbAvr4 for Avr4-related constructs, and pSfinx::MfEcp2, pSfinx::MfEcp2-2, and pSfinx::MfEcp2-3 for Ecp2-related constructs. Transient coexpression of effectors and cognate resistance proteins in N. benthamiana was performed as described (15). Binary vectors pCf-4, pAvr4, pCf-9, pAvr9 (30) and pHcr9-Avr4-chm1, pHcr9-Avr4-par1 pHcr9-Avr4-per1 (16) were used as control gene pairs. Binary vectors made were pMfAvr4, pCbAvr4, and pCnAvr4. Constructs were obtained by cloning Avr4 or Ecp2 cDNAs encoding the mature proteins, downstream of the PR1A signal sequence of N. tabacum for secretion into the apoplast and under control of the CaMV 35S promoter. Detailed information is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Heterologous Production of His6-FLAG-Tagged M. fijiensis Avr4 in Pichia pastoris.

Mature Mfvr4 was produced in P. pastoris and purified from culture filtrate as previously described (37). Binding of MfAvr4 to chitin and in vitro fungal growth assays in the presence of chitinases were examined as described (4). Detailed information is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. R. P. Oliver and Dr. B. P. H. J. Thomma for critical reading of the manuscript. I.S. is financially supported by an ERA-PG grant, H.v.d.B. by the Centre of BioSystems Genomics (CBSG), P.J.G.M.D.W. by the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, and G.H.J.K. is partially sponsored by the Dioraphte Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The nucleotide sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in GenBank (accession nos. CbAvr4: GU574324 CnAvr4: GU574325 CaAvr4: GU574326 CzAvr4: GU574327).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/1002910107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Thomma BPHJ, Van Esse HP, Crous PW, De Wit PJGM. Cladosporium fulvum (syn. Passalora fulva), a highly specialized plant pathogen as a model for functional studies on plant pathogenic Mycosphaerellaceae. Mol Plant Pathol. 2005;6:379–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2005.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stergiopoulos I, De Wit PGM. Fungal effector proteins. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2009;47:233–263. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.112408.132637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wulff BBH, Chakrabarti A, Jones DA. Recognitional specificity and evolution in the tomato-Cladosporium fulvum pathosystem. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2009;22:1191–1202. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-10-1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van den Burg HA, et al. Cladosporium fulvum Avr4 protects fungal cell walls against hydrolysis by plant chitinases accumulating during infection. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2006;19:1420–1430. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Esse HP, et al. The chitin-binding Cladosporium fulvum effector protein Avr4 is a virulence factor. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2007;20:1092–1101. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-9-1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laugé R, et al. The in planta-produced extracellular proteins ECP1 and ECP2 of Cladosporium fulvum are virulence factors. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1997;10:725–734. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haanstra JPW, et al. The Cf-ECP2 gene is linked to, but not part of, the Cf-4/Cf-9 cluster on the short arm of chromosome 1 in tomato. Mol Gen Genet. 1999;262:839–845. doi: 10.1007/s004380051148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones JDG, Dangl JL. The plant immune system. Nature. 2006;444:323–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoch CL, et al. A multigene phylogeny of the Dothideomycetes using four nuclear loci. Mycologia. 2006;98:1041–1052. doi: 10.3852/mycologia.98.6.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marin DH, Romero RA, Guzman M, Sutton TB. Black sigatoka: An increasing threat to banana cultivation. Plant Dis. 2003;87:208–222. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2003.87.3.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van den Burg HA, et al. Binding of the AVR4 elicitor of Cladosporium fulvum to chitotriose units is facilitated by positive allosteric protein-protein interactions. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16786–16796. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312594200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stergiopoulos I, et al. Mating-type genes and the genetic structure of a world-wide collection of the tomato pathogen Cladosporium fulvum. Fungal Genet Biol. 2007;44:415–429. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joosten MHAJ, et al. The biotrophic fungus Cladosporium fulvum circumvents Cf-4-mediated resistance by producing unstable AVR4 elicitors. Plant Cell. 1997;9:367–379. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.3.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas CM, et al. Characterization of the tomato Cf-4 gene for resistance to Cladosporium fulvum identifies sequences that determine recognitional specificity in Cf-4 and Cf-9. Plant Cell. 1997;9:2209–2224. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.12.2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van der Hoorn RAL, Laurent F, Roth R, De Wit PJGM. Agroinfiltration is a versatile tool that facilitates comparative analyses of Avr9/Cf-9-induced and Avr4/Cf-4-induced necrosis. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2000;13:439–446. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kruijt M, et al. The Cf-4 and Cf-9 resistance genes against Cladosporium fulvum are conserved in wild tomato species. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2005;18:1011–1021. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-18-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laugé R, et al. Successful search for a resistance gene in tomato targeted against a virulence factor of a fungal pathogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9014–9018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.9014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bolton MD, et al. The novel Cladosporium fulvum lysin motif effector Ecp6 is a virulence factor with orthologues in other fungal species. Mol Microbiol. 2008;69:119–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Jonge R, Thomma BPHJ. Fungal LysM effectors: Extinguishers of host immunity? Trends Microbiol. 2009;17:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collmer A, Schneider DJ, Lindeberg M. Lifestyles of the effector rich: Genome-enabled characterization of bacterial plant pathogens. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:1623–1630. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.140327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hajri A, et al. A «repertoire for repertoire» hypothesis: Repertoires of type three effectors are candidate determinants of host specificity in Xanthomonas. PLoS One. 2009;4(8):e6632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamoun S. A catalogue of the effector secretome of plant pathogenic oomycetes. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2006;44:41–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.44.070505.143436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stergiopoulos I, De Kock MJD, Lindhout P, De Wit PJGM. Allelic variation in the effector genes of the tomato pathogen Cladosporium fulvum reveals different modes of adaptive evolution. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2007;20:1271–1283. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-10-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beveraggi A, Mourichon X, Sallé G. Comparative-study of the first stages of infection in sensitive and resistant banana plants with Cercospora fijiensis (Mycosphae-rella fijiensis), responsible for black leaf streak disease. Can J Bot Rev. 1995;73:1328–1337. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bisgrove SR, et al. A disease resistance gene in Arabidopsis with specificity for 2 different pathogen avirulence genes. Plant Cell. 1994;6:927–933. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.7.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao SY, et al. Broad-spectrum mildew resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana mediated by RPW8. Science. 2001;291:118–120. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5501.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Esse HP, et al. Tomato transcriptional responses to a foliar and a vascular fungal pathogen are distinct. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2009;22:245–258. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-3-0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliver RP, Ipcho SVS. Arabidopsis pathology breathes new life into the necrotrophs-vs.-biotrophs classification of fungal pathogens. Mol Plant Pathol. 2004;5:347–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2004.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wevelsiep L, Kogel KH, Knogge W. Purification and characterization of peptides from Rhynchosporium secalis inducing necrosis in barley. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1991;39:471–482. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ciuffetti LM, Tuori RP, Gaventa JM. A single gene encodes a selective toxin causal to the development of tan spot of wheat. Plant Cell. 1997;9:135–144. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friesen TL, et al. Emergence of a new disease as a result of interspecific virulence gene transfer. Nat Genet. 2006;38:953–956. doi: 10.1038/ng1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friesen T, et al. Characterization of the interaction of a novel Stagonospora nodorum host-selective toxin with a wheat susceptibility gene. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:682–693. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.108761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rohe M, et al. The race-specific elicitor, Nip1, from the barley pathogen, Rhynchosporium secalis, determines avirulence on host plants of the Rrs1 resistance genotype. EMBO J. 1995;14:4168–4177. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00090.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friesen TL, Faris JD, Solomon PS, Oliver RP. Host-specific toxins: Effectors of necrotrophic pathogenicity. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:1421–1428. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haen KM, Lu HJ, Friesen TL, Faris JD. Genomic targeting and high-resolution mapping of the Tsn1 gene in wheat. Crop Sci. 2004;44:951–962. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hammond-Kosack KE, Staskawicz BJ, Jones JDG, Baulcombe DC. Functional expression of a fungal avirulence gene from a modified Potato-Virus-X genome. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1995;8:181–185. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rooney HCE, et al. Cladosporium Avr2 inhibits tomato Rcr3 protease required for Cf-2-dependent disease resistance. Science. 2005;308:1783–1786. doi: 10.1126/science.1111404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.