Abstract

Objective To assess whether equity is achieved in use of general practitioner, outpatient, and inpatient services by children and young people according to their ethnic group and socioeconomic background.

Design Secondary analysis of the British general household survey, 1991-94.

Subjects 20 473 children and young people aged between 0 and 19 years.

Main outcome measures Consultations with a general practitioner within a two week period, outpatient attendances within a three month period, and inpatient stays during the past year.

Results There were no significant class differences in the use of health services by children and young people, and there was little evidence of variation in use of health services according to housing tenure and parental work status. South Asian children and young people used general practitioner services more than any other ethnic group after controlling for socioeconomic background and perceived health status, but the use of hospital outpatient and inpatient services was significantly lower for children and young people from all minority ethnic groups compared with the white population.

Conclusions Our results differ from previous studies, which have reported significant class differences in use of health services for other age groups. We found no evidence that children and young people’s use of health services varied according to their socioeconomic status, suggesting that equity has been achieved. A child or young person’s ethnic origin, however, was clearly associated with use of general practitioner and hospital services, which could imply that children and young people from minority ethnic groups receive a poorer quality of health care than other children and young people.

Key messages

The use of general practitioner, outpatient, and inpatient services by children and young people does not vary significantly according to their socioeconomic status

Indian children and young people are more likely to consult a general practitioner than any other ethnic group

Black Caribbean, Indian, and Pakistani or Bangladeshi children and young people are less likely to use hospital inpatient and outpatient services than white children and young people

These ethnic differences have important implications for the quality of health care received by children and young people

Introduction

Many large scale studies have questioned whether equity is being achieved in the use of health services on the basis of social class; some have suggested that the higher social classes use disproportionately more health services than the lower classes after accounting for variations in morbidity1–3 whereas others have not found any class inequality.4–6

However, studies of equity frequently neglect or exclude the use of health services by children and young people, despite evidence that young age groups form a significant proportion of all healthcare users,7 and that health service use is heavily age dependent.1,4

Many previous studies are based on data from the 1970s. Therefore it is important to update and extend these analyses to reflect social and economic factors that may influence health service use in the mid-1990s. In addition to social class, poor material living conditions are associated with increased illness and accidents in children and young people8–10 and a higher use of health services.11

We examined the use of health services by children and young people from different ethnic groups. A consistent finding for adults is high utilisation of general practitioner services, particularly among the South Asian population,12–14 and lower hospital use among minority ethnic groups relative to the white population.15–17 However, despite the youthful age profile of minority ethnic groups, the use of general practitioner and hospital services has rarely been considered specifically for children and young people after adjusting for differences in their socioeconomic background and perceived health status. Our study provides a broader analysis of equity that examines not only whether class inequality exists in children and young people’s use of health services, but also considers whether their ethnic group and other salient features of the patient’s socioeconomic environment influence the pattern of health service use.

Subjects and methods

We used data from the British general household survey, aggregated over three years from 1991 to 1994. The survey is nationally representative and collects data on all individuals living in approximately 10 000 households each year. The response rate is estimated at 75% for minority ethnic groups and 82% for white people, but households with children tend to be overrepresented in the sample.18 Information for children under 16 years is obtained from the mother or person responsible for them within the household. Our sample included 20 473 children and young people aged between 0 and 19 years. About 10% of our sample belonged to a minority ethnic group according to the classification of the general household survey, of which 1% were black Caribbean (n=243), 2% Indian (n=483), and 3% Pakistani or Bangladeshi (n=505). These proportions were equivalent to the 1991 census, in which 9.7% of children and young people aged between 0 and 19 years in Great Britain were in minority ethnic groups.19

Health service use—

The health service use measures were: (a) whether the child or young person consulted a general practitioner within a two week period, (b) whether the child or young person had attended a casualty or outpatient department within the past three months, and (c) whether the child or person had been an inpatient during the past year.

Morbidity—

Two measures of morbidity used to represent chronic and acute illness were firstly, whether the child or young person had a reported non-limiting or limiting illness and, secondly, whether the child or young person had had to reduce activity within the past two weeks because of ill health (with additional information on the number of days that activity was restricted). Measures of perceived health status have been shown to be predictive of actual health status, with no systematic bias according to class, age,20,21 or parental reports of chronic illness in children and young people.22

Age—

Age was used as a control variable in the multivariate analysis as infants are likely to differ from older children in their access to healthcare services.

Ethnicity—

The general household survey asks for the ethnic group of respondents according to a list provided. For the purposes of our analysis, children and young people were classified into one of five ethnic groups: white, black Caribbean, Pakistani or Bangladeshi, Indian, and other. ‘Other’ includes children and young people of mixed origin as well as other Asian and black African groups. For part of the analysis, the Indian and Pakistani or Bangladeshi groups were combined into a single South Asian group to achieve an adequate sample size.

Socioeconomic background—

We used three measures of socioeconomic status. Firstly, social class of the head of the family unit, based on the registrar general’s socioeconomic groups, was used to measure the socioeconomic status of the child or young person’s family unit. Secondly, information about the current work status of parents provided information on the labour force participation of both couple and lone parent families. Thirdly, housing tenure of the parents was used as a measure of structural disadvantage that applied universally to the household, divided into three categories: owner occupier, privately rented, and local authority or housing association property.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using the spss package.23 After tabular analysis, multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to assess the influence of socioeconomic background and ethnicity on the child or young person’s use of each health service, after controlling for perceived health need. These results are presented as odds ratios.

Results

Table 1 examines whether class inequality exists in the use of each health service for people under 20 years of age. The proportion of children and young people consulting a general practitioner did not vary significantly with social class and there was no evidence of a class gradient in the use of this service. The lowest use of outpatient services was for children and young people whose parents were skilled manual workers (572/5499, 10.4%) and the highest use was for children and young people whose parents were unskilled workers (101/849, 11.9%), but this variation was not consistent across the social classes and did not reach statistical significance. There was some evidence that social class is associated with use of inpatient services (P<0.05). Children and young people from the non-manual classes displayed a comparable use of inpatient services (about 5.6%), which rose to 7.2% (61/849) for those whose parents were unskilled workers.

Table 1.

Numbers (percentages) of children and young people using general practitioner, outpatient, and inpatient services by socioeconomic group of head of family unit. Data from British general household survey, 1991-94

| Health service | Socioeconomic group of head of family unit

|

P value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professional, managerial | Employer, managerial, lower professional | Junior non-manual | Skilled manual | Semi-skilled | Unskilled | All | ||

| General practitioner | 430/3212 (13.4) | 477/3363 (14.2) | 330/2114 (15.6) | 809/5501 (14.7) | 400/2617 (15.3) | 119/849 (14.0) | 2560/17 656 (14.5) | NS |

| Outpatient | 350/3210 (10.9) | 367/3363 (10.9) | 245/2114 (11.6) | 572/5499 (10.4) | 293/2619 (11.2) | 101/849 (11.9) | 1914/17 564 (10.9) | NS |

| Inpatient | 177/3210 (5.5) | 188/3362 (5.6) | 123/2113 (5.8) | 380/5501 (6.9) | 170/2619 (6.5) | 61/849 (7.2) | 1089/17 564 (6.2) | <0.05 |

Table 2 shows the use of health services among children and young people by ethnic group. Within the two week reference period, children and young people from both South Asian groups were more likely to consult a general practitioner than those from the white population and other ethnic groups: 17.1% (78/456) of Indian children or young people and 16.4% (78/475) of Pakistani or Bangladeshi children or young people compared with 14.5% (2399/16 542) of white children and young people. The lowest likelihood of consultation (31/235, 13.2%) was among black Caribbean children and young people. In contrast, the use of outpatient services was significantly lower among Indian (28/456, 6.1%) and Pakistani or Bangladeshi children and young people (24/475, 5.1%), with around twice as many white children and young people (1869/16 540, 11.3%) using this service over a three month period. The proportion of black Caribbean children and young people using outpatient services (17/235, 7.2%) was lower than that of white children and young people and those from other ethnic groups. Overall, the ethnic variation in outpatient use was statistically significant (P<0.001). All children and young people from minority ethnic groups had lower use of hospital inpatient services than white children and young people, and these differences were statistically significant (P<0.01). This lower use was most evident among black Caribbean children and young people, where only 2.6% (6/235) stayed as a hospital inpatient in the past year compared with 6.5% (1075/16 540) of white children and young people. The proportion of South Asian children and young people using this service was low for Indian children and young people (16/456, 3.5%) and Pakistani or Bangladeshi children and young people (24/475, 5.1%).

Table 2.

Numbers (percentages) of children and young people using general practitioner, outpatient, and inpatient services by ethnic group. Data from British general household survey, 1991-94

| Health service | Ethnic group of patient

|

P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Black Caribbean | Indian | Pakistani or Bangladeshi | Other | All | ||

| General practitioner | 2399/16 542 (14.5) | 31/235 (13.2) | 78/456 (17.1) | 78/475 (16.4) | 113/791 (14.3) | 2682/18 499 (14.5) | NS |

| Outpatient | 1869/16 540 (11.3) | 17/235 (7.2) | 28/456 (6.1) | 24/475 (5.1) | 81/791 (10.2) | 2016/18 495 (10.9) | <0.001 |

| Inpatient | 1075/16 540 (6.5) | 6/235 (2.6) | 16/456 (3.5) | 24/475 (5.1) | 43/791 (5.4) | 1165/18 497 (6.3) | <0.01 |

Table 3 presents the results of a logistic regression analysis, which highlights the independent effects of socioeconomic status and ethnicity on the use of health services by children and young people after controlling for age, sex, and perceived health status.

Table 3.

Odds ratios of health service use adjusted for age (in paired years), socioeconomic position*, perceived health status, and ethnic group in 17 485 children and young people. Data from British general household survey, 1991-94

| Variable | General practitioner

|

Outpatient

|

Inpatient

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 1.00 | <0.05 | 1.00 | <0.01 | — | NS | ||

| Female | 1.12 (1.02 to 1.22) | 0.87 (0.79 to 0.96) | — | |||||

| Housing tenure | ||||||||

| Owner occupier | — | NS | — | NS | 1.00 | <0.001 | ||

| Private rental | — | — | 1.14 (0.87 to 1.51) | |||||

| Local authority | — | — | 1.40 (1.19 to 1.67) | |||||

| Chronic health status | ||||||||

| No chronic illness | 1.00 | <0.001 | 1.00 | <0.001 | 1.00 | <0.001 | ||

| Longstanding illness | 1.89 (1.66 to 2.17) | 2.58 (2.26 to 2.95) | 2.86 (2.42 to 3.39) | |||||

| Limiting longstanding illness | 1.69 (1.45 to 1.99) | 4.71 (4.11 to 5.41) | 5.24 (4.42 to 6.22) | |||||

| Days of acute illness in past 2 weeks | ||||||||

| None | 1.00 | <0.001 | — | NA | — | NA | ||

| 1-2 | 4.41 (3.70 to 5.26) | — | — | |||||

| 3-5 | 10.75 (8.99 to 12.88) | — | — | |||||

| ⩾6 | 12.10 (10.08 to 14.53) | — | — | |||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 1.00 | <0.05 | 1.00 | <0.001 | 1.00 | <0.05 | ||

| Black Caribbean | 0.83 (0.53 to 1.31) | 0.58 (0.34 to 1.01) | 0.38 (0.17 to 0.87) | |||||

| Indian | 1.59 (1.21 to 2.10) | 0.62 (0.42 to 0.93) | 0.65 (0.38 to 1.12) | |||||

| Pakistani or Bangladeshi | 1.09 (0.81 to 1.50) | 0.46 (0.29 to 0.73) | 0.80 (0.51 to 1.30) | |||||

| Other | 0.90 (0.71 to 1.15) | 0.98 (0.77 to 1.27) | 0.80 (0.57 to 1.13) | |||||

NA=not applicable to model.

Socioeconomic group for head of family unit, and family work status were not statistically significant after controlling for other variables, and are therefore not shown.

For all children and young people, perceived health status was most strongly associated with the use of each health service. The odds of consulting a general practitioner increased with the duration of acute illness, and reporting a chronic illness significantly increased the use of all three health services.

There were no statistically significant social class differences in the use of general practitioner, outpatient, or inpatient services, and so these results are not shown. The class variation in inpatient use shown in table 1 disappeared after controlling for perceived health status and housing tenure.

Housing tenure was not associated with the use of general practitioner or outpatient services, but the odds ratio of inpatient use was increased by 40% in children and young people living in local authority accommodation compared with those living in owner occupied housing.

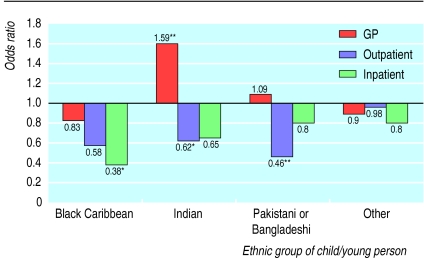

Ethnicity was significantly associated with the use of general practitioner, outpatient, and inpatient services by children and young people. The figure presents the odds ratios of health service use by minority ethnic children and young people relative to white children and young people. Indian children and young people were significantly more likely to consult a general practitioner than white children and young people (odds ratio 1.59, 95% confidence interval 1.21 to 2.10), whereas the use of this service by Pakistani or Bangladeshi children and young people was comparable to that by white children and young people after controlling for the other variables in the model. The use of outpatient services by both South Asian groups was significantly lower than that of white children and young people, especially for Pakistani or Bangladeshi children and young people where the odds were reduced by 54%. Black Caribbean children and young people also had reduced odds of using outpatient services, and they were also significantly less likely to become an inpatient than any other ethnic group (odds ratio 0.38, 0.17 to 0.87).

Discussion

The absence of class variation observed in children and young people contrasts with previous work on the adult population1–3 and suggests that important differences may exist in the use of health services by children and young people compared with adults. Although our initial results suggested social class was associated with the use of inpatient services by children and young people, this variation was eliminated when controlling for the patient’s perceived health status and other socioeconomic factors. Overall, there was no evidence to suggest that children and young people from the lower social classes are more disadvantaged in their use of health services than children and young people from the professional classes. Therefore the use of health services is equitable in terms of social class status.

Our results showed that other measures of socioeconomic status did not produce any consistent variation in the use of health services by children and young people, except that those living in local authority housing were significantly more likely to use inpatient services. This is consistent with previous work on children and young people,14 but in addition our study showed that this association remained after controlling for the child or young person’s morbidity. These findings support previous work showing that children and young people living in materially deprived conditions are more likely to be admitted to hospital,10 or that accidents occurring in the home environment that require hospital treatment are socially patterned.8,9

Ethnicity was clearly associated with the use of health services by children and young people, after controlling for socioeconomic status and perceived health status. Consistent with this finding, several previous studies of adults reported that the number of general practitioner consultations in South Asian adults12,14,15 was higher than that in adults from any other ethnic group, after controlling for variations in morbidity.13 An important finding of our analysis is that Indian children and young people were most likely to consult their general practitioner, whereas previous studies on adults reported that Pakistani or Bangladeshi patients consulted a general practitioner more than any of the other ethnic groups.13

Increased general practitioner consultations for South Asian groups could indicate a poor initial consultation that necessitates further visits to the doctor during a period of ill health. The much lower use of secondary care services by minority ethnic children and young people confirms previous research findings,24 and would be consistent with general practitioner discrimination or bias in the referral process. However, a study that examined the referral of children and young people from minority ethnic groups by general practitioners found no evidence to support this claim.25

Conclusion

Studying a broad age range of children and young people, we found no evidence to suggest that class inequalities exist in the use of general practitioner, outpatient, and inpatient services. Local authority housing was associated with higher use of inpatient services by children and young people after controlling for morbidity, but other measures of socioeconomic status did not produce consistent variation in health service use. In contrast, the ethnicity of children and young people was strongly associated with their pattern of use. Indian children and young people were significantly more likely to consult a general practitioner, but children and young people from all minority ethnic groups had a much lower use of outpatient and inpatient services than white children and young people. These differences persisted after controlling for socioeconomic position and health status, and they may suggest that children and young people from minority ethnic groups receive lower rates of referral to secondary care services and a poorer healthcare service than white children and young people.

Figure.

Comparison of odds ratios of health service use by children and young people from minority ethnic groups (compared with white population) controlling for age, sex, socioeconomic status, and perceived health status of patient. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (signficance of difference from reference category of white). Data from general household survey, 1991-94

Acknowledgments

The general household survey data were supplied by the University of Essex data archive and Manchester computing service.

Footnotes

Funding: This project was funded by the NHS South Thames mother and child health programme. The paper represents the views of the authors and not the NHS Executive.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Forster DP. Social class differences in sickness and general practitioner consultations. Health Trends. 1976;8:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Grand J. The distribution of public expenditure: the case of health care. Economica. 1978;45:125–142. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health and Social Security. Inequalities in health: the Black Report. Harmondsworth: Penguin; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins E, Klein R. Equity and the NHS: self reported morbidity, access and primary care. BMJ. 1980;281:1111–1115. doi: 10.1136/bmj.281.6248.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blaxter M. Equity and consultation rates in general practice. BMJ. 1984;288:1963–1967. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6435.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Donnell O, Propper C. Equity and the distribution of UK National Health Service resources. J Health Econ. 1991;10:1–19. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(91)90014-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett N, Jarvis L, Rowlands O, Singleton N, Haselden L. Living in Britain: results from the 1994 General Household Survey. London: HMSO; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts H, Smith SJ, Bryce C. Children at risk? Safety as a social value. Buckingham: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts I, Power C. Does the decline in child mortality vary by social class? A comparison of class specific mortality in 1981 and 1991. BMJ. 1996;313:784–786. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7060.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maclure A, Stewart GT. Admission of children to hospitals in Glasgow: relation to unemployment and other deprivation variables. Lancet. 1984;ii:682–685. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91234-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balarajan R, Yuen P, Machin D. Socioeconomic differentials in the uptake of medical care in Great Britain. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1987;41:196–199. doi: 10.1136/jech.41.3.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson MR, Cross M, Cardew SA. Inner city residents, ethnic minorities and primary health care. Postgrad Med J. 1983;59:664–667. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.59.696.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Modood T. Ethnic minorities in Britain: diversity and disadvantage. London: Policy Studies Institute; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balarajan R, Yuen P, Raleigh VS. Ethnic differences in general practitioner consultations. BMJ. 1989;299:958–960. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6705.958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smaje C, Le Grand J. Ethnicity, equity and the use of health services in the British NHS. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:485–496. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00380-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rudat K. Black and minority ethnic groups in England: health and lifestyles. London: Health Education Authority; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smaje C. Health, race and ethnicity: making sense of the evidence. London: King’s Fund Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foster K, Jackson B, Thomas M, Hunter P, Bennett N. London: HMSO; 1995. Appendixn: General Household Survey 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Office for Population Censuses and Surveys. 1991 census: children and young adults. Vol. 1. London: HMSO; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macintyre S, Pritchard C. Comparisons between the self assessed and observer-assessed presence and severity of colds. Soc Sci Med. 1989;29:1243–1248. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lundberg O, Manderbacka K. Assessing reliability of self-rated health. Scand J Soc Med. 1996;24:218–224. doi: 10.1177/140349489602400314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ecob R, Macintyre S, West P. Reporting by parents of longstanding illness in their adolescent children. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36:1017–1022. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90119-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norusis MJ. Base system user’s guide, release 6.0. Chicago: SPSS; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balarajan R, Raleigh VS, Yuen P. Hospital care among ethnic minorities in Britain. Health Trends. 1991;23:90–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smaje C. Equity and the ethnic patterning of GP services in Britain. Soc Policy Administration. 1998;32:116–131. [Google Scholar]