Abstract

The availability of oxygen is a major environmental factor for many microbes, in particular for bacteria such as Shewanella species, which thrive in redox-stratified environments. One of the best-studied systems involved in mediating the response to changes in environmental oxygen levels is the Arc two-component system of Escherichia coli, consisting of the sensor kinase ArcB and the cognate response regulator ArcA. An ArcA ortholog was previously identified in Shewanella, and as in Escherichia coli, Shewanella ArcA is involved in regulating the response to shifts in oxygen levels. Here, we identified the hybrid sensor kinase SO_0577, now designated ArcS, as the previously elusive cognate sensor kinase of the Arc system in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Phenotypic mutant characterization, transcriptomic analysis, protein-protein interaction, and phosphotransfer studies revealed that the Shewanella Arc system consists of the sensor kinase ArcS, the single phosphotransfer domain protein HptA, and the response regulator ArcA. Phylogenetic analyses suggest that HptA might be a relict of ArcB. Conversely, ArcS is substantially different with respect to overall sequence homologies and domain organizations. Thus, we speculate that ArcS might have adopted the role of ArcB after a loss of the original sensor kinase, perhaps as a consequence of regulatory adaptation to a redox-stratified environment.

Shewanella species are Gram-negative, facultatively anaerobic gammaproteobacteria. Bacteria of this genus are characterized by their ability to use an impressive range of organic and inorganic alternative terminal electron acceptors if oxygen is lacking. Numerous compounds such as fumarate, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), thiosulfate, nitrate, and nitrite and, in addition, numerous soluble and insoluble metal ions such as Fe(III) and Mn(III/IV) can be respired (50, 52). Thus, species such as Shewanella significantly impact biogeochemical cycling processes and are of particular interest with regard to the mobilization and immobilization of potential anthropogenic pollutants (24, 25, 41, 51). The enormous respiratory versatility is thought to be a consequence of adaptation to redox-stratified environments (76). To successfully compete in such environments, Shewanella species are required to rapidly respond to changes in the availability of oxygen. In addition, Shewanella species are thought to be useful agents for bioremediation processes. Thus, maximizing the potential of Shewanella species in bioremediation processes requires a better understanding of how they sense and respond to redox clines.

One of the best-studied bacterial systems involved in the adaptation to changes in environmental oxygen levels is the Arc (anoxic redox control) two-component system of Escherichia coli (28). The Arc system consists of a sensor histidine kinase (ArcB) and a cognate DNA-binding response regulator (ArcA). ArcB does not sense oxygen directly but instead senses the redox status of ubiquinone and menaquinone, the central electron carriers of respiration (10, 18, 46). The autophosphorylation activity of an ArcB dimer is thought to depend on intermolecular disulfide bond formation involving two cytosol-located cysteine residues. Under anaerobic conditions, the pool of ubiquinone and menaquinone shifts to the reduced state and releases the disulfide bonds by the reduction of the corresponding cysteine residues, thereby activating the ATP-dependent autophosphorylation activity of the transmitter domain (46). Via a multistep phosphorelay, the phosphoryl group is transferred to the receiver domain of the response regulator ArcA by the C-terminal phosphotransfer domain (Hpt). Phosphorylated ArcA can function as an activator or a repressor by binding to the promoter regions of its target genes (20, 35, 43). ArcB has been demonstrated to be a bifunctional histidine kinase that also mediates the dephosphorylation of its cognate response regulator ArcA, resulting in signal decay (17, 55). Since the multimerization of phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated ArcA is required for response regulator function, ArcB likely ensures, in the dependence of environmental conditions, that an appropriate level of phosphorylated ArcA is present in the cell (30).

An ortholog of ArcA can also be identified in Shewanella species. ArcA of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 shares 81% identity with its E. coli counterpart and is one of the most highly conserved proteins between the two organisms (25). Accordingly, S. oneidensis ArcA was shown to complement an E. coli arcA mutant (21). As in E. coli, ArcA is a major regulator in S. oneidensis MR-1, and it was demonstrated previously that ArcA is involved in mediating the response to changing oxygen levels and in the formation and dynamics of biofilms (15, 21, 71). Global transcriptomic analysis revealed that in both S. oneidensis MR-1 and E. coli, more than 1,000 genes are directly or indirectly regulated by this response regulator (15, 39, 61). However, overlaps in the ArcA-controlled regulons of E. coli and S. oneidensis MR-1 were surprisingly rare. Thus, despite representing one of the major regulators in both species, the physiological function of ArcA appears to be substantially different (16).

In addition to Shewanella, orthologs of ArcA are present in numerous bacteria such as Erwinia, Haemophilus, Shigella, Vibrio, and Yersinia (18, 42, 63, 74). In these species, the cognate sensor kinase ArcB can be readily identified by sequence homologies to E. coli ArcB. An exception is the Shewanella Arc system, which lacks a sensor kinase orthologous to ArcB. A single histidine phosphotransferase domain protein (SO_1327 [HptA]) displays significant homologies to the C-terminal Hpt domain of E. coli ArcB. Based on genetic studies, it was hypothesized that HptA acts as a phosphodonor for ArcA in S. oneidensis MR-1 (21). However, in vivo protein-protein interactions and/or phosphotransfer have not been demonstrated. Thus, it remains obscure whether HptA and ArcA function in the same signaling pathway, and furthermore, a cognate sensor kinase for the Shewanella Arc system still remains unknown.

In this study, we used a candidate approach to identify the cognate sensor kinase for the Shewanella ArcA response regulator. We demonstrate that the hybrid sensor kinase SO_0577 (herein designated ArcS), HptA, and ArcA constitute an atypical Arc signaling system in S. oneidensis MR-1 and most likely in other Shewanella species. Although distinct from ArcB sensor kinases, ArcS appears to be functionally equivalent to E. coli ArcB. The results pose intriguing questions about the functional evolution of the Arc system in Shewanella.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. S. oneidensis MR-1 and E. coli were routinely grown in LB medium at 30°C (for S. oneidensis) and 37°C (for E. coli), unless indicated otherwise. When required, media were solidified by using 1.5% (wt/vol) agar. Anaerobic growth was assayed in LB adjusted to pH 7.5 and supplemented with 20 mM lactate as a carbon source and either 220 mM dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 20 mM fumarate as a terminal electron acceptor. To remove oxygen from culture tubes, they were stoppered, sealed, and flushed with nitrogen gas for several minutes with periodic shaking prior to autoclaving (7). The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of cultures was monitored. If necessary, media were supplemented with 10 μg·ml−1 chloramphenicol, 50 μg·ml−1 kanamycin sulfate, and/or 100 μg·ml−1 ampicillin sodium salt. To allow the growth of the conjugation strain E. coli WM3064, meso-diaminopimelic acid (DAP) was added to a final concentration of 300 μM. For promoter induction from plasmid pBAD33, l-arabinose was added to a final concentration of 0.2% (wt/vol) in liquid medium.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid and function | Relevant genotype or descriptiona | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5α-λpir | φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U196 recA1 hsdR17 deoR thi-1 supE44 gyrA96 relA1/λpir | 48 |

| WM3064 | thrB1004 pro thi rpsL hsdS lacZΔM15 RP4-1360 Δ(araBAD)567 ΔdapA1341::[erm pir(wt)] | W. Metcalf, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign |

| BTH101a | F−cya-99 araD139 galE15 galK16 rpsL1 (Strr) hsdR2 mcrA mcrB1 | Euromedex, France |

| Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 | ||

| S79 | Wild type | 72 |

| S143 | ΔSO_0577 (ΔarcS) | This study |

| S838 | Wild type (“knock-in” complementation of ΔarcS) | This study |

| S313 | ΔSO_1327 (ΔhptA) | This study |

| S802 | Wild type (knock-in complementation of ΔhptA) | This study |

| S318 | ΔSO_3988 (ΔarcA) | This study |

| S805 | Wild type (knock-in complementation of ΔarcA) | This study |

| S315 | Δarc ΔhptA | This study |

| S320 | ΔarcS ΔarcA | This study |

| S836 | ΔhptA ΔarcA | This study |

| S834 | ΔarcS ΔhptA ΔarcA | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pNPTS138 | mobRP4+sacB ColE1 ori Kmr | M. R. Alley, unpublished data |

| pUC18R6KT-mini-Tn7T | mobRP4+ori-R6K TnR/TnL Apr | 13 |

| pNPTS138-R6KT | mobRP4+ori-R6K sacB; suicide plasmid for in-frame deletions; Kmr | This study |

| Construction of in-frame deletions and complementation in Shewanella sp. | ||

| pGP704Sac28Km | mobRP4+ori-R6K sacB; suicide plasmid for in-frame deletions; Kmr | Chengyen Wu, unpublished data |

| pGP704Sac28Km-ΔSO_0577 | SO_0577 (arcS) deletion fragment in pGP704Sac28Km | This study |

| pGP704Sac28Km-KI-SO_0577 | SO_0577 (arcS) complementation fragment in pGP704Sac28Km | This study |

| pNPTS138-R6KT-ΔhptA | hptA deletion fragment in pNPTS138R6KT | This study |

| pNPTS138-R6KT-KI-hptA | hptA complementation fragment in pNPTS138R6KT | This study |

| pNPTS138-R6KT-ΔarcA | arcA deletion fragment in pNPTS138R6KT | This study |

| pNPTS138-R6KT-KI-arcA | arcA complementation fragment in pNPTS138R6KT | This study |

| pNPTS138-R6KT-ΔSputCN32_3300 | SputCN32_3300 (arcS) deletion fragment in pNPTS138R6KT | This study |

| pNPTS138-R6KT-KI-SputCN32_3300 | SputCN32_3300 complementation fragment in pNPTS138R6KT | This study |

| pBAD33 | ori-p15a araC PBAD Cmr | 23 |

| pBAD33-RBS-SO0577 | SO_0577 (arcS) in pBAD33 | This study |

| pBAD33-RBS-hptA | hptA in pBAD33 | This study |

| pBAD33-RBS-arcA | arcA in pBAD33 | This study |

| Overproduction of S. oneidensis MR-1 Arc components | ||

| pBAD-HisA | Invitrogen | |

| pBAD-HisA-SO_0577-646 | SO_0577 C-terminal coding region (aa 646-1188) in pBADHisA | This study |

| pBAD-HisA-arcA | arcA in pBADHisA | This study |

| pBAD-HisA-arcA-D54N | arcA(D54N) in pBADHisA | This study |

| pBAD-HisA-SO_3457-181 | SO_3457 C-terminal coding region (aa 181-929) in pBADHisA | This study |

| pGEX4T-1 | ori-pBR322 Plac Apr | |

| pGEX4T-1-hptA | hptA in pGEX4T-1 | This study |

| pGEX4T-1-hptA-H62A | hptA(H62A) in pGEX4T-1 | This study |

| Bacterial two-hybrid constructs | ||

| pUT18 | ori-ColE1 Plac T18 for N-terminal fusion; Apr | Euromedex, France |

| pUT18C | ori-ColE1 PlacT18 for C-terminal fusion; Apr | Euromedex, France |

| pKT25 | ori-p15a Plac T25 for C-terminal fusion; Kmr | Euromedex, France |

| pKNT25 | ori-p15a Plac T25 for N-terminal fusion; Kmr | Euromedex, France |

| pUT18-SO_0577-364 | SO_0577 (arcS) C-terminal region (aa 364-1188) in pUT18 | This study |

| pUT18C-SO_0577-364 | SO_0577 (arcS) C-terminal region (aa 364-1188) in pUT18C | This study |

| pKT25-SO_0577-364 | SO_0577 (arcS) C-terminal region (aa 364-1188) in pKT25 | This study |

| pUT18-hptA | hptA in pUT18 | This study |

| pUT18C-hptA | hptA in pUT18C | This study |

| pKT25-hptA | hptA in pKT25 | This study |

| pKNT25-hptA | hptA in pKNT25 | This study |

| pUT18C-arctA | arcA in pUT18C | This study |

| pKT25-arcA | arcA in pKT25 | This study |

| pKNT25-arcA | arcA in pKNT25 | This study |

| pUT18C-SO_3457-172 | SO_3457 (barA) C-terminal region (aa 172-929) into pUT18C | This study |

| pKT25-SO_3457-172 | SO_3457 (barA) C-terminal region (aa 172-929) into pKT25 | This study |

Apr, ampicillin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Kmr, kanamycin resistance.

Strain constructions.

Molecular methods were carried out according to standard protocols (58, 62) or according to the manufacturer's instructions. Kits for the isolation of plasmids and purification of PCR products were purchased from HISS Diagnostics GmbH (Freiburg, Germany). Enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Frankfurt, Germany) and Fermentas (St. Leon-Rot, Germany). Replicative plasmids were transferred into E. coli strains by transformation using chemically competent cells (27) and into Shewanella sp. by electroporation (49).

In-frame deletion mutants of S. oneidensis MR-1 were constructed essentially as previously described, leaving terminal sections of the target genes (69, 71). For that purpose, upstream and downstream fragments (about 500 bp) of the desired gene region were amplified by PCR using the corresponding primer pairs (listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material). After purification, the fragments were fused by overlap PCR (64). The final product was isolated from an agarose gel, digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes, and ligated into the suicide vector pGP704Sac28Km (arcS) and pNPTS138-R6KT (hptA arcA). pNPTS138-R6KT was derived from pNPTS138 (M. R. Alley, unpublished data), replacing the pUC origin by a γ origin amplified from pUC18R6KT-mini-Tn7T (13) after restriction with BssSI and DraIII. The resulting plasmid was introduced into S. oneidensis MR-1 by conjugative mating using E. coli WM3064 as a donor on LB medium containing DAP. Single-crossover integration mutants were selected on LB plates containing kanamycin but lacking DAP. Single colonies were grown overnight in LB without antibiotics and plated onto LB containing 10% (wt/vol) sucrose to select for plasmid excision. Kanamycin-sensitive colonies were then checked for targeted deletion by colony PCR using primers bracketing the location of the deletion.

For complementation of in-frame deletions, two strategies were used. For induced ectopic expression from a plasmid, the corresponding gene was amplified from wild-type chromosomal DNA, treated with the appropriate restriction enzymes, and ligated into pBAD33. In addition, the S. oneidensis MR-1 genotype was restored by replacing the in-frame deletion by the wild-type copy of the gene according to the deletion strategy described above.

Construction of strains and plasmids for two-hybrid analysis.

For protein-protein interaction analysis, we used the bacterial two-hybrid system described by Karimova et al. (32). To this end, the corresponding genes were cloned into bacterial two-hybrid expression vectors to create N- and C-terminal fusions to two complementary fragments, T25 and T18, encoding segments of the catalytic domain of the Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase CyaA. In vivo interactions of T25- and T18-fused proteins will lead to a reconstitution of CyaA activity and increase of intracellular cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels in an appropriate E. coli reporter strain (32). To generate in-frame fusions to the T18 and T25 fragments of adenylate cyclase (CyaA) from Bordetella pertussis, specific gene regions from S. oneidensis MR-1 and E. coli MG1655 were amplified with specific primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). PstI and BamHI restriction sites were introduced at the 5′ ends of the arcA (SO_3988) forward and reverse primers, respectively, and cloned in frame into pKT25, pKNT25, pUT18, and pUT18C. For all other fragments, XbaI and XmaI restriction sites were introduced at the 5′ ends of the forward and reverse primers, respectively, and cloned in frame into plasmids pKT25, pKNT25, pUT18, and pUT18C (33). Subsequently, different plasmid pairs (Fig. S4) were cotransformed into chemically competent E. coli BTH101 (Euromedex, France) cells and grown on selective LB agar. Plasmids for positive controls (pKT25-zip and pUT18-zip harboring an in-frame fusion to the leucine zipper of GCN4) and negative controls (empty vectors) were transformed in the same way. The successful transformation of both plasmids of interest into E. coli BTH101 cells was verified by PCR using plasmid-specific check primers. Positive candidates were grown at 30°C with orbital shaking (200 rpm) in 5 ml LB medium with the appropriate antibiotics. Three-microliter aliquots of exponentially growing cultures were spotted onto selective MacConkey agar plates containing 50 g/liter MacConkey agar (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) containing the appropriate antibiotics and 1% (wt/vol) maltose. Positive- and negative-control strains were spotted additionally onto each plate. The plates were incubated at room temperature for at least 72 h until colonies developed a clearly distinguishable color tone and were photographed from the top view.

Construction of plasmids for protein overproduction.

Genes and gene fragments to be overexpressed were amplified from template genomic DNA by using the primers listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Site-directed mutagenesis in arcA and hptA was achieved by use of overlap extension PCR as previously described (2). The resulting PCR products for arcS(646-1188), arcA, arcA(D54N), and barA(181-929) were ligated into pBAD-HisA (Invitrogen) to result in N-terminal His tag fusions. hptA and hptA(H62A) were cloned into pGEX4T-1 (GE Healthcare), yielding N-terminal fusions to glutathione S-transferase (GST).

Biofilm formation and motility assays.

Rapid motility screening was carried out by spotting 3 μl of a liquid culture of the appropriate strain onto plates that contained LB agar with an agar concentration of 0.25% (wt/vol). Differences in motility were determined by the rate of radial expansion from the center of inoculation (54).

To analyze biofilm formation (70), 96-well flat-bottom microtiter polypropylene plates containing 150 μl of LB were inoculated with exponentially growing cultures (OD600 of 0.1) of the appropriate Shewanella strains. The cultures were incubated at 30°C for 24 h, and crystal violet was added directly to each well at a final concentration of 0.015% (wt/vol). After 10 min, the wells were washed twice with water, and the remaining surface-attached biomass was quantified indirectly by the solubilization of retained crystal violet by the addition of 200 μl of 95% ethanol followed by measurements of the absorbance at 570 nm. To exclude that differences in biofilm formation are caused by growth defects, each sample was normalized to the planktonic growth yield (sample OD600/sample OD570). Biofilm formation of the mutants was determined for eight replications and normalized to that of the wild-type control.

RNA extraction from S. oneidensis MR-1.

Cells growing exponentially either under aerobic conditions (OD600 of 0.5 to 0.7) or under anaerobic conditions (OD600 of 0.3 to 0.4) were harvested by centrifugation at 4,600 × g for 15 min at 4°C, and the cell sediments were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Total RNA was extracted from S. oneidensis MR-1 cells by using the hot-phenol method (1). Residual chromosomal DNA was removed by using Turbo DNA-Free (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The purified RNA was then used for transcriptomic profiling by microarray analysis or quantitative real-time PCR (q-RT-PCR).

Expression profiling.

Microarray analysis was performed with Febit (Febit Biomed GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany). For each strain, three independent RNA samples from three independent experiments were analyzed. Oligonucleotide probes were synthesized by using light-activated in situ oligonucleotide synthesis inside a biochip of a Geniom One instrument (Febit Biomed GmbH, Germany) as described previously (9). One biochip (array) contained eight individual microfluidic channels, each of which contained >15,000 individual DNA probe features. The probe set was calculated from the full S. oneidensis MR-1 genome sequence (according to TIGR; data accessed on 4 June 2008) using proprietary software from Febit Biomed based on a modified Smith-Waterman algorithm (65). For each of the 4,770 genes annotated for S. oneidensis MR-1, three 50-mer probes likely to hybridize with high specificity and sensitivity were synthesized. For some of the genes, fewer than three probes could be calculated based on the Febit specificity criteria.

Quality control of RNA was carried out with the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 apparatus used the RNA 6000 nanokit according to the manufacturer's instructions. 16S and 23S rRNAs were removed from RNA by use of the MICROBExpress kit from Ambion. For each array, 3 μg of total RNA was purified according to the manufacturer's instructions. mRNA was then labeled by use of the Message AmpTMII-Bacteria kit (Ambion). After biotin labeling, samples were dried in a Speed-Vac and fragmented with a fragmentation buffer (Febit). Finally, 15 μl of Longmer hybridization buffer (Febit) was added to each array. Samples were loaded onto the arrays, and hybridization was carried out overnight (16 h) at 45°C by using argon pressure to move the samples within the arrays. After the hybridization, the chip was washed automatically, and the signal was enhanced according to standard Febit protocols.

Data analysis.

The resulting detection pictures were evaluated by using Geniom Wizard software (Febit Biomed GmbH). Following background correction, quantile normalization was applied, and all further analyses were carried out by using the normalized and background-subtracted intensity values. After verification of the normal distribution of the measured data, a parametric t test (unpaired and two tailed) was carried out for each gene separately to detect genes that showed a differential expression between the compared groups. The resulting P values were adjusted for multiple testing by Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment (26, 34). For significant statistical measurements, an adjusted P value cutoff of <0.05 (5%) was applied.

q-RT-PCR.

Extracted total RNA was applied as a template for random-primed first-strand cDNA synthesis by using Bioscript (Bioline) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cDNA was used as a template for quantitative PCR (Real-Time 7300 PCR machine; Applied Biosystems) by using the Sybr green detection system (Applied Biosystems). Samples were assayed at least in duplicate. The signal was standardized to recA where the CT (cycle threshold) was determined automatically by use of Real-Time 7300 PCR software (Applied Biosystems) after 40 cycles. The efficiency of each primer pair was determined by using four different concentrations of S. oneidensis MR-1 chromosomal DNA (10 μg·liter−1, 1.0 μg ng·liter−1, 0.1 μg·liter−1, and 0.01 μg·liter−1) as a template for q-RT-PCRs.

Overproduction and purification of recombinant proteins.

His6-ArcS, His6-ArcA, and His6-BarA as well as the corresponding derivatives were overproduced in E. coli DH5α λpir cells harboring the corresponding expression plasmids in super optimal broth (SOB) medium. Expression was induced by the addition of l-arabinose to a final concentration of 0.2% (wt/vol) to exponentially growing cultures followed by incubation for 4 h at 37°C. To induce the production of GST-HptA proteins, 1 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to the corresponding cultures.

For the purification of recombinant proteins (29), cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4 [pH 8.0], 300 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 0.5 mg/ml lysozyme) and lysed by three passages through a French press (SLM-Aminco; Spectronic) at 18,000 lb/in2.

The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C, and the supernatant was filtered (0.45 μm). The purification was performed by affinity chromatography at 4°C, according to the manufacturer's instructions, in a batch procedure using either 1 ml Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) Superflow (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) for His6 proteins or 1 ml GST-Bind resin (Novagen) for GST fusion proteins. Elution fractions containing purified protein were pooled and dialyzed against TGMNKD buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 10% [vol/vol] glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol) overnight at 4°C prior to use for further assays (59).

Radiolabeled in vitro autophosphorylation and phosphotransfer assays.

To autophosphorylate ArcA, 10 μM protein was incubated in TGMNKD buffer with an equivalent volume of [32P]acetyl phosphate for 30 min at room temperature (29). The reaction was quenched with 5× Laemmli sample buffer (0.125 M Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 20% glycerol, 4% SDS, 10% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.02% bromophenol blue). Radioactive acetyl phosphate was generated by incubating the following reaction mixture at room temperature for 2 h: 1.5 units of acetate kinase (Sigma), TKM buffer (2.5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 6 mM potassium acetate, 1 mM MgCl2), and 10 μl of [γ-32P]ATP (14.8 GBq·mmol−1; Amersham Biosciences) in a total volume of 100 μl. To remove the acetate kinase, the reaction was subjected to centrifugation in a Microcon YM-10 centrifugal filter unit (Millipore) for 1 h. The flowthrough was collected and stored at 4°C.

In vitro phosphorylation of ArcS and BarA was carried out with TGMNKD buffer containing 0.5 mM [γ-32P]ATP (14.8 GBq mmol−1; Amersham) and 10 μM corresponding protein in a 50-μl total volume for 30 min at room temperature. Aliquots of 10 μl were quenched with 2 μl of 5× Laemmli (36) sample buffer (0.313 M Tris-HCl [pH 6.8 at 25°C], 10% SDS, 0.05% bromophenol blue, and 50% glycerol).

Phosphotransfer reactions with purified ArcA, HptA, ArcS, and corresponding point mutations were performed by first autophosphorylating 10 μM either ArcA or ArcA(D54N) for 30 min as described above. An aliquot was removed for an autophosphorylation control. An equivalent volume containing the response regulator at an equal concentration was then added to the reaction mixture and incubated for 1 min. Both reactions were then quenched with 5× Laemmli sample buffer (kinase final concentration, 2.5 μM).

For analysis of the autophosphorylation or the phosphotransfer reaction, 10-μl samples were loaded without prior heating on a 15% polyacrylamide gel and separated by denaturating sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Subsequently, gels were exposed to a PhosphorImager screen overnight, and images were detected on a Typhoon Trio PhosphorImager (Amersham Biosciences). Gels were subsequently stained by Coomassie dye (Carl Roth, Germany) to visualize proteins.

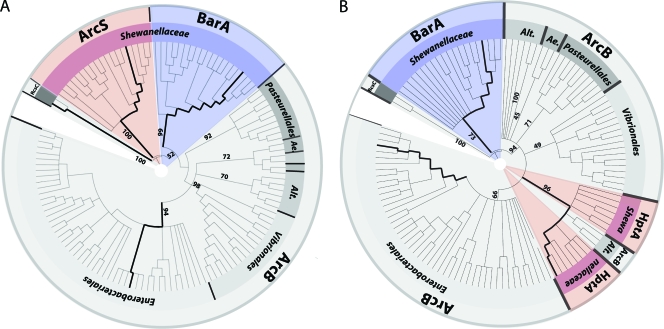

Identification and phylogenetic analysis of ArcB proteins.

To identify proteins orthologous to E. coli ArcA and ArcB, the corresponding E. coli sequence was aligned to the available sequence data for gammaproteobacteria by using BLAST (6). The retrieved sequences for ArcA were used for multiple alignments by using ClustalX 2.0.10.

The HisKA-ATPase_e domain or the Hpt domain of ArcB proteins was individually aligned against the corresponding domains of Shewanella ArcS, BarA, HptA, and SO_4445 (outgroup). The resulting alignments were improved by manual curation and were then used to generate phylogenetic trees by using the maximum-likelihood method (http://phylobench.vital-it.ch/raxml-bb) (66). Phylogenetic trees were visualized by using iTOL (38).

Microarray data accession number.

The raw data and normalized data are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE21044.

RESULTS

Identification of an ArcA cognate sensor kinase.

According to the genomic data, the chromosome of S. oneidensis MR-1 encodes 44 putative sensor kinases, 9 of which are predicted to be hybrid kinases (25). To narrow down the group of potential candidates of cognate sensor kinases for ArcA in Shewanella, we made several assumptions. Based on the high identity of ArcA within the genus Shewanella, we expected the corresponding sensor kinase to be equally highly conserved among Shewanella species. Since the single-domain protein HptA was assumed to be involved in phosphotransfer to ArcA (21), the cognate sensor kinase might lack a phosphotransfer domain. In addition, we hypothesized that, in accordance with E. coli arcB, a likely candidate is not associated directly with a response regulator (“orphan”). Finally, since ArcA was demonstrated to regulate the shift from aerobic to anaerobic conditions, the cognate sensor kinase might possess one or several PAS domains, as does E. coli ArcB.

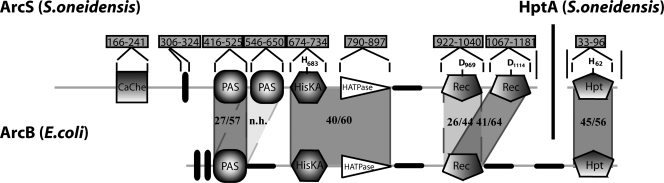

Based on these assumptions, SO_0577 emerged as the most likely candidate in S. oneidensis MR-1 (Fig. 1). The corresponding open reading frame encompasses 3,567 bp and might be transcribed monocistronically or in an operon with the downstream gene SO_0578, encoding a hypothetical protein. The encoded protein of 1,188 amino acids (aa) with a predicted molecular mass of 134.7 kDa is annotated as a hybrid sensor kinase. Analysis of the amino acid sequence suggests that the protein possesses a pronounced periplasmic segment (aa 1 to 305), including a CaChe domain followed by a single transmembrane domain (aa 306 to 324). The cytoplasmic section (aa 325 to 1188) of the protein is predicted to consist of two PAS domains, a histidine kinase region (consisting of HisKA [DHp] and HATPase_c [CA] domains), and two receiver domains. Thus, the domain organization and identity/similarity at the amino acid level are remarkably different from those of E. coli ArcB (Fig. 1). Due to these differences, we referred to SO_0577 as ArcS. ArcS is highly conserved within the genus Shewanella (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) and resides in the same genetic context in all species sequenced so far.

FIG. 1.

Domain organization of Shewanella ArcS compared to that of E. coli ArcB. The numbers in boxes mark the positions of the domains in the amino acid sequence. The position of conserved amino acid residues putatively involved in phosphotransfer is marked within the corresponding domain. The numbers in shaded areas between the domains of ArcS and ArcB display levels of identity/similarity between the domains (n/h, no homologies). Black vertical bars show the positions of transmembrane domains. CaChe, CaChe-sensing domain; PAS, energy-sensing domain; HisKA, histidine kinase dimerization domain; HATPase_c, histidine kinase ATPase domain; REC, receiver domain.

A comparison of ArcS with the genome of E. coli revealed that the highest similarities do not occur with ArcB but rather occur with BarA, the cognate sensor kinase of the global response regulator UvrY (37). In S. oneidensis MR-1, another orphan hybrid sensor kinase, SO_3457, is annotated as the BarA sensor kinase of the UvrY ortholog SO_1860. The cytoplasmic phosphotransfer section of Shewanella BarA displayed a similar degree of similarity to E. coli ArcB as ArcS and has a similar domain structure. Therefore, SO_3457 was included as a specificity control in subsequent experiments.

Phenotypic mutant analysis of arcS, hptA, and arcA.

To elucidate whether ArcS, HptA, and ArcA might function together in a single regulatory pathway, we conducted a mutant phenotype analysis. We generated in-frame deletions in the corresponding genes as well as all combinations of double deletions and a triple deletion. Deletions in hptA and arcA were previously reported to have pleiotropic phenotypes such as a pronounced growth defect under aerobic conditions (15, 21) and altered biofilm formation and dynamics (71). Therefore, we determined the effect of the introduced mutations on growth, biofilm formation, and motility. All phenotypic analyses were carried out in at least three independent experiments.

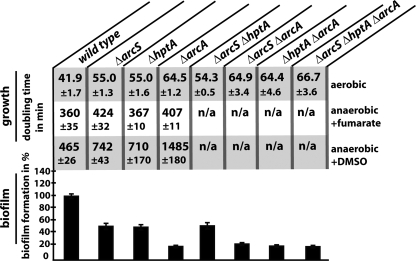

Growth experiments were conducted under conditions similar to those previously reported to yield comparable sets of data. The deletion of either arcS, hptA, or both genes resulted in an increase in doubling time from 42 min (wild type) to 55 min (single mutants) and 54.3 min (ΔarcS ΔhptA) (Fig. 2). A deletion of arcA further increased the doubling time to 64.5 min, almost exactly matching the doubling times of the ΔarcS ΔarcA and ΔhptA ΔarcA mutants as well as the triple-deletion strains (64.9, 64.4, and 66.7 min, respectively). arcS and arcA mutants displayed a slight growth defect during anaerobic growth with fumarate as the terminal electron acceptor, similar to what was reported previously for mutants lacking ArcA and HptA (15, 21). Additionally, the ΔarcS and ΔhptA strains had the same growth phenotype under anaerobic conditions with DMSO as a terminal electron acceptor, while ΔarcA mutants displayed a more drastic growth defect (Fig. 2). All phenotypes of the mutants were restored to wild-type levels upon the expression of the corresponding proteins ectopically from a plasmid or by restoring the wild-type genotype by the reintegration of the gene (“knock-in”) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG. 2.

Growth and biofilm formation of ΔarcS, ΔhptA, and ΔarcA mutans. The doubling times of the corresponding strains under aerobic (top) and anaerobic conditions with fumarate (middle) and DMSO (bottom) as electron acceptors, respectively, are indicated. At the bottom, the biofilm formation of the mutants relative to that of the wild type is indicated. The error bars represent the standard deviations. n/a, not applicable.

The biofilm formation ability of mutants and the wild type was determined with a static microtiter dish assay (Fig. 2, bottom). Consistent with the observed growth phenotypes, the ΔarcS, ΔhptA, and ΔarcS ΔhptA mutants displayed an identical decrease in biofilm formation. The lack of ArcA resulted in less surface-attached biomass, and no cumulative phenotype occurred in the corresponding double- or triple-deletion mutant strains. Complementation of the single-mutant strains resulted in the restoration of biofilm formation to wild-type levels. In addition, all mutants displayed a similar reduction of motility, as measured by the rate of radial expansion from the center of inoculation. As for aerobic growth and biofilm formation, mutants in arcA were more drastically affected than mutants lacking SO_0577 and HptA (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

If all three proteins function in the same regulatory pathway, we expected similar phenotypes of mutants lacking the sensor kinases ArcS, HptA, and both, since both components would be required for signal acquisition and transmission. Since ArcA represents the most downstream component of the signaling cascade, additional deletions of the putative signaling partners should not yield a cumulative phenotype. Previous studies of the Arc system of E. coli revealed that the function of ArcA requires the multimerization of phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated response regulator subunits (30). In the absence of the sensor kinase ArcB, which also functions as ArcA phosphatase, ArcA can undergo autophosphorylation in vivo at the expense of acetyl phosphate (40). Thus, in the absence of ArcB, ArcA might still exhibit a substantial level of activity. This would explain the finding that for S. oneidensis MR-1, an arcA deletion results in more drastic phenotypes than deletions of arcS and/or hptA. Thus, the phenotypic analysis strongly supported the hypothesis that ArcS, HptA, and/or ArcA functions in the same regulatory pathway with the response regulator ArcA as the epistatic component.

ArcS and ArcA have overlapping regulons.

If ArcS is the cognate sensor kinase for ArcA, we assumed that a significant set of genes is directly or indirectly regulated in a similar fashion by both sensor kinase and response regulator. The regulon of ArcA in S. oneidensis MR-1 has recently been analyzed (15). To determine whether the regulon of SO_0577 overlaps with that of ArcA, we performed a global transcriptomic analysis by comparing the wild-type transcriptome to that of an arcS mutant under aerobic conditions. In order to obtain comparable data sets, growth conditions were adjusted according to those described in a previous study (15). The cells of the wild-type and mutant strains were harvested 1 h after entering the exponential growth phase at an OD600 of 0.5. The validation of the expression data by statistical analysis was confirmed by quantitative real-time PCR (q-RT-PCR) conducted on seven genes with different levels of regulation (r2 = 0.94) (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material).

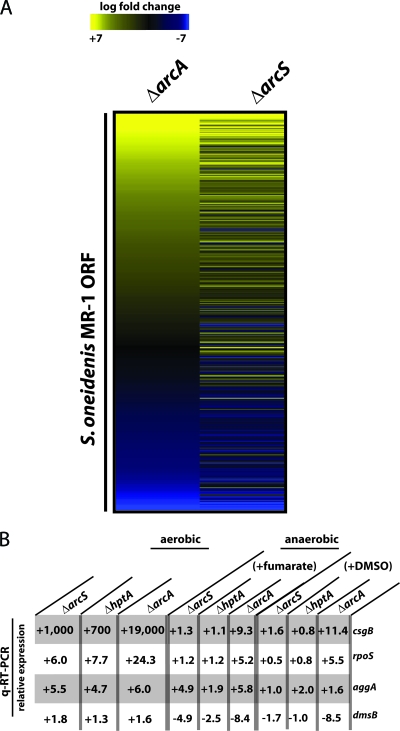

According to the statistical analysis (P < 0.05), 604 genes had significantly different transcriptional levels (log2 ≥ 1), confirming that ArcS is likely to represent the sensor kinase of a global regulator system. Among the 604 genes, 295 genes were significantly upregulated and 309 genes were significantly downregulated (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). In order to determine whether the changes in transcriptomic levels of an arcS mutant are similar to that of an arcA mutant, we compared our data set to that obtained from a mutant lacking ArcA (Fig. 3) (15). Four hundred twenty-five genes were identified as being significantly regulated in both mutants. Out of these 425 genes, 365 (85.9%) displayed similar regulation patterns in mutants lacking either ArcA or ArcS, suggesting an extensive overlap of the respective regulons.

FIG. 3.

Transcriptomic analysis of ΔarcS, ΔhptA, and ΔarcA mutants. (A) Hierarchical clustering of genes significantly regulated in both ΔarcA and ΔarcS mutant strains under aerobic conditions as analyzed by microarrays. Expression differences between mutants (left, ΔarcA; right, ΔarcS) and the wild type are represented by colors (yellow, induced; blue, repressed). (B) Changes in transcriptional levels of csgB, rpoS, aggA, and dmsB in ΔarcS, ΔhptA, and ΔarcA mutants grown under aerobic and anaerobic conditions compared to the wild type. Transcript levels were analyzed by q-RT-PCR. ORF, open reading frame.

To further determine whether a similar regulatory pattern of mutants in arcS, hptA, and arcA occurs under aerobic and anaerobic conditions, qRT-PCR was conducted on four selected genes (csgB, rpoS, aggA, and dmsB) (Fig. 3). Template RNA was prepared from exponentially growing cultures of the wild type and corresponding mutants. For the anaerobic cultures, fumarate or DMSO was added as a terminal electron acceptor. This analysis revealed identical expression patterns of the four genes with respect to up- or downregulation in all three mutants under all conditions tested. While the levels of expression changes in the arcS and hptA mutants were very similar, an arcA mutation usually resulted in a more drastic change in expression. This was in agreement with the observations from the phenotypic analysis and might be the result of ArcA autophosphorylation by acetyl phosphate (40).

Interaction and phosphotransfer between ArcS, HptA, and ArcA.

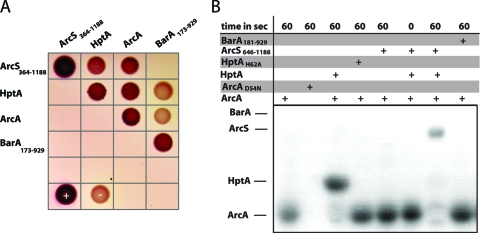

The phenotypic and transcriptomic analyses of mutants in arcS, hptA, and arcA indicated that all three components function in the same regulatory pathway. Thus, it should be expected that the components interact and that a phosphoryl group is transferred between the sensor kinase and the response regulator via HptA. In order to demonstrate directly that a functional interaction occurs, we employed two strategies. In the first approach, in vivo interactions between the components were determined by a bacterial two-hybrid assay. To this end, arcS, hptA, and arcA were cloned in bacterial two-hybrid expression vectors to create N- and C-terminal fusions to two complementary fragments, T25 and T18, encoding segments of the catalytic domain of the Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase CyaA (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The cloned fragment of ArcS (aa 364 to 1188) did not include the periplasmic and transmembrane domains, which are unlikely to be involved in functional interactions. To serve as a control for the specificity of sensor-regulator interactions, the cytoplasmic section (aa 173 to 929) of the hybrid sensor kinase SO_3457, annotated as BarA in Shewanella, was also fused to T25 and T18. These interaction studies revealed that all components interact with themselves (Fig. 4). This was expected, since sensor kinases were previously described to dimerize (67), and dimer and/or multimer formation of Hpt single-domain proteins and ArcA, respectively, was demonstrated in previous studies (30, 75). The assay also strongly indicated that in vivo interactions occur between all components of the putative Shewanella Arc system, ArcS, HptA, and ArcA. In contrast, neither HptA nor ArcA displayed interactions with the sensor kinase SO_3457 (BarA). From these results, we concluded that ArcS, HptA, and ArcA interact with each other and that the interactions of the putative Arc system are likely specific.

FIG. 4.

In vivo and in vitro interactions of ArcS, HptA, and ArcA. (A) Analysis of in vivo protein-protein interactions in a bacterial two-hybrid system. Interactions of the indicated proteins fused to the T18 and T25 fragments, respectively, of the B. pertussis adenylate cyclase result in a red appearance of the colonies on MacConkey agar. +, positive control (T18-zip/T25-zip); −, negative control (T18/T25 empty vectors). (B) Autoradiographic analysis of phosphotransfer between ArcS(646-1188), GST-HptA, and ArcA. Phosphorylated ArcA (10 μM) was incubated for the given amount of time (top) with equimolar amounts of the indicated components and then separated by SDS-PAGE.

In a second parallel approach, we conducted in vitro phosphotransfer studies on purified proteins to demonstrate that functional interactions occur between ArcS, HptA, and ArcA. As a specificity control, the sensor kinase SO_3457 (BarA) was included in these analyses.

HptA was purified as a GST-tagged recombinant protein; all other proteins were produced by using recombinant N-terminal His tag fusions. ArcS was purified as a soluble variant (aa 646 to 1188) lacking the periplasmic, transmembrane, and PAS sensor domains. The construct for the overproduction of BarA comprised the cytoplasmic part (aa 181 to 929) lacking the periplasmic and the transmembrane domains. The activity of the purified sensor kinases was tested by incubation with [γ-32P]ATP and subsequent separation by SDS-PAGE. Both sensor kinases were readily phosphorylated, indicating that the kinase region is capable of autophosphorylation. However, when either of the phosphorylated sensor kinases was incubated with purified GST-HptA and/or ArcA, no phosphotransfer occurred, and the sensor kinases remained phosphorylated (data not shown).

E. coli ArcB is known to be a bifunctional histidine kinase that also mediates the dephosphorylation of its cognate response regulator ArcA, resulting in signal decay in vivo (17, 55). We therefore tested whether reverse phosphotransfer from the response regulator to the sensor kinase might occur (Fig. 4 and see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). To this end, purified ArcA and an ArcA variant in which the predicted site of phosphorylation was replaced [ArcA(D54N)] were incubated with [γ-32P]acetyl phosphate. Only wild-type ArcA was radioactively labeled under these conditions, indicating protein phosphorylation at the predicted site. Purified GST-HptA was not phosphorylated by either [γ-32P]ATP or [γ-32P]acetyl phosphate (data not shown). When phosphorylated ArcA was incubated with GST-HptA, the phosphogroup was rapidly transferred and further passed on to ArcS (Fig. 4 and see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). No direct phosphotransfer occurred between ArcA and ArcS. Phosphotransfer between ArcA, GST-HptA, and ArcS was also not observed when an HptA variant was used in which the predicted site of phosphorylation was replaced [HptA(H62A)]. The control assays demonstrated that no reverse phosphotransfer to SO_3457 (BarA) occurred in the presence or absence of GST-HptA (Fig. S4).

From these results, we concluded that ArcS, HptA, and ArcA specifically interact and that a phosphoryl group is transferred among the three components. Thus, taken together with data from the phenotypic and transcriptomic analyses, we have unambiguously identified ArcS as a cognate sensor kinase for ArcA in Shewanella.

Functional overlap between ArcS and ArcB.

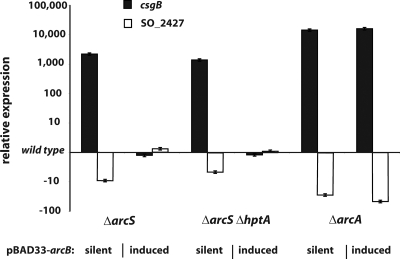

Previous studies demonstrated that, similar to E. coli, the Shewanella Arc system is implicated in regulating the shift from aerobic to anaerobic conditions (15, 21). E. coli ArcB is assumed to respond primarily to the redox status of central electron carriers of respiration, ubiquinone and menaquinone (10, 18, 46). The differences in ArcS- and ArcB-sensing domain architectures raised the question of whether ArcS is also responding to the redox state in a fashion similar to that of ArcB or whether a different signal might be perceived. If both sensor kinases respond to the same signal, we hypothesized that ArcB of E. coli might be able to partially complement the phenotypes of mutants lacking ArcS and/or HptA. To determine a potential functional overlap between ArcB and ArcS, we cloned E. coli arcB in a vector under the control of an inducible promoter. The vector was introduced into the S. oneidensis MR-1 wild type, an ΔarcS mutant, an ΔarcS ΔhptA mutant, and the ΔarcA mutant. We then tested the effect of ArcB production on growth under aerobic conditions (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Surprisingly, the induction of arcB resulted in a full restoration of the growth rate in the ΔarcS and ΔarcS ΔhptA mutants. In contrast, an ΔarcA mutant could not be complemented. In addition, total RNA isolated from the ArcB-expressing mutant strains during the exponential growth phase was used to determine the expression levels of two genes (csgB and SO_2427) by quantitative real-time PCR. Both genes were previously identified by microarray analysis to be strongly up- or downregulated by ArcS and ArcA in S. oneidensis. Strikingly, in accordance with the complementation of growth phenotypes, transcriptional levels of both genes were restored to that of the wild type in ΔarcS and ΔarcS ΔhptA but not in ΔarcA mutants (Fig. 5). Thus, despite the pronounced structural differences, ArcS and ArcB appear to respond to signals in a similar fashion to regulate the activity of ArcA.

FIG. 5.

Restoration of transcriptional levels in arc mutants by E. coli ArcB. arcB from E. coli was cloned into the inducible vector pBAD33, and the resulting vector was electroporated into ΔarcS, ΔarcS ΔhptA, and ΔarcA mutants. The transcriptional levels of csgB (black bars) and SO_2427 (white bars) were determined by q-RT-PCR of RNA obtained from the corresponding cultures grown aerobically under inducing and noninducing (“silent”) conditions. The bars display the expression levels relative to that of the wild type. The error bars represent standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

The availability of oxygen has profound consequences for numerous bacteria with respect to metabolism and detoxification of reactive oxygen species. Thus, bacteria must be capable of sensing oxygen levels or the environmental redox state to elicit an appropriate response. This is particularly imperative for bacteria that live in redox-stratified environments, such as Shewanella species (52). However, the regulatory systems underlying the response to changing oxygen levels in Shewanella are not well understood. Here, we identified the cognate sensor kinase of the Arc system in S. oneidensis MR-1 that is involved in regulating the shift from aerobic to anaerobic conditions. In addition, we have demonstrated that the signaling pathway includes the single phosphotransfer domain protein HptA, which mediates the phosphotransfer between the hybrid sensor kinase ArcS and the response regulator ArcA.

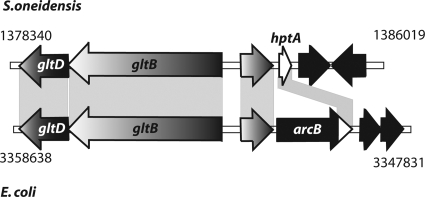

The paradigm Arc system of E. coli has been extensively studied, where it consists of two components, the sensor kinase ArcB and the cognate response regulator ArcA (reviewed in reference 45). Numerous gammaproteobacteria have been described to possess ArcA response regulators orthologous to E. coli (18, 42, 63, 74). However, in sharp contrast to Shewanella, in almost all species, the cognate sensor kinase ArcB can be readily identified by homology comparisons. Previous studies have identified the single phosphotransfer domain protein HptA of S. oneidensis MR-1 to share significant homologies (45% identity and 56% similarity) with the corresponding C-terminal domain of ArcB (21). An analysis of the adjacent gene regions surrounding hptA revealed that the upstream region is strikingly similar to that of ArcB in E. coli (Fig. 6). In both cases, the upstream region encompasses an open reading frame encoding a conserved hypothetical protein (57% identity and 72% similarity) and two genes encoding subunits of the glutamate synthase, gltB and gltD. Not surprisingly, in homology alignments, HptA and its corresponding orthologs in other Shewanella species form a clade together with hybrid sensor kinases annotated as ArcB of other gammaproteobacteria (Fig. 7). The most likely explanation for this finding would be that the residual part of arcB encoding the receiver, histidine kinase, and sensor domains was either lost or relocated to another region of the chromosome by genetic rearrangements. In the latter case, it would be expected that the cognate sensor ArcS shares significant homologies to other ArcB sensor kinase proteins. However, as homology comparisons have demonstrated, ArcS does not fall into a group with other ArcB sensor kinases (Fig. 7). This implies that a genetic rearrangement has occurred with an ArcB sensor kinase that was already significantly different from the E. coli counterpart. A second possibility is that ArcS has taken over the role as the cognate sensor kinase for ArcA after a loss of the original ArcB.

FIG. 6.

Gene organization alignments of the S. oneidensis hptA locus and the E. coli arcB locus. Genes are displayed as arrows indicating the direction of transcription. The shaded areas display regions of significant similarity. The coordinates in the genome are given to the left and right of the corresponding region. The genetic organization strongly indicates that the major part of arcB was lost in Shewanella, leaving the phosphotransfer domain hptA.

FIG. 7.

Phylogenetic analysis of the Shewanella ArcS histidine kinase region (A) and HptA (B). The appropriate protein sequences were aligned with those of the BarA sensor kinase, the ArcB sensor kinase, and the putative RcsC sensor kinase of S. oneidensis MR-1 (outgroup). Bold lines represent the positions of S. oneidensis RcsC, ArcS, and BarA and E. coli ArcB (A) and S. oneidensis MR-1 BarA and HptA and E. coli ArcB (B) (in clockwise order). The numbers display the corresponding bootstrap values. The Shewanella Arc and BarA proteins are marked in red and blue, respectively. ArcB proteins are marked in gray. Alt., Alteromonadales; Ae., Aeromonadales.

Our studies have shown that E. coli ArcB can functionally replace ArcS with respect to growth under aerobic conditions. This indicates that ArcS might similarly sense the redox state of membrane-located electron carriers. Two redox-active cysteine residues (Cys180 and Cys241) are located in the ArcB PAS domain of E. coli and were demonstrated previously to be involved in the silencing of autophosphorylation activity (46). Only one of the cysteine residues is conserved in ArcS (Cys435) and might play a similar role in regulating activity. However, for the redox sensing of ArcB, the cysteine residues might be dispensable. Notably, a group of ArcB sensor kinases, for example, from Actinobacillus, Haemophilus, Mannheimia, and Pasteurella, are lacking the PAS domain and both conserved cysteine residues. However, the ArcB sensor kinases of Mannheimia succiniciproducens and Haemophilus influenzae were demonstrated to partially complement phenotypes of an arcB deletion in E. coli, indicating a significant degree of functional conservation (19, 31). Thus, the mechanism of signal sensing by ArcS might be similar to that of the ArcB sensor kinases lacking the redox-active cysteine residues, but this remains to be elucidated. Further studies are required to determine whether and under which conditions phosphorelay toward the response regulator occurs. Thus far, our in vitro studies demonstrated only phosphotransfer toward the sensor kinase.

Previous studies have shown that the regulons of ArcA are strikingly different in S. oneidensis MR-1 and E. coli. In contrast to S. oneidensis, which displayed a pronounced growth phenotype under aerobic conditions, the E. coli Arc system appears to have a rather limited role during aerobic growth (3-5, 57). An effect on bacterial stasis survival, as was described previously for E. coli (47, 53), was not identified for S. oneidensis MR-1 (15, 73). Also, while ArcA is affecting the activity of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle in E. coli, its role in regulating metabolism in S. oneidensis is rather minor (with the exception of DMSO reduction) (15, 21). The life-styles and natural environments of E. coli and Shewanella are substantially different, and it was suggested previously that regulatory systems adopted by individual species are adjusted accordingly (56). Not surprisingly, the Arc system is not the only regulator system that has been shown to function in a different fashion in Shewanella. Other orthologs of major regulating systems of E. coli that have a different regulatory output are present in S. oneidensis MR-1. In E. coli, a second major regulator mediating the response to oxygen levels is FNR (22, 33). In contrast to E. coli, in which FNR is regulating anaerobic respiration, the Shewanella ortholog EtrA does not have a significant role in this process (44). The EtrA regulon is also rather small, encompassing 69 genes (11). Notably, the cyclic AMP receptor protein (CRP) is thought to be a major regulator to mediate anaerobic respiration in Shewanella. It was therefore hypothesized that the shift to anaerobic conditions might be regulated directly or indirectly via cAMP levels (12, 60). In E. coli, CRP is implicated to play a role in catabolite repression (14).

The adaptation of regulatory circuits might occur at the level of transcription factors, promoter sequences, and circuit architecture (56). Thus, we suggest that the switch of the Shewanella Arc sensory system reflects an adaption to environmental conditions. A separation of the phosphotransfer domain HptA and the sensor kinase might enable regulatory cross talk with another signaling pathway, as does the presence of a second intrinsic receiver domain in ArcS. In addition, ArcS possesses a second PAS sensor domain and an N-terminal periplasmic CaChe domain. While PAS domains have long been recognized as sensors of various signals (68), a CaChe domain was recently implicated in energy and/or pH sensing (8). In light of the redox-stratified environment from which Shewanella species can be isolated, we hypothesize that an expansion of the Arc sensor system occurred as a consequence of the requirement to adapt to a broader range of environmental conditions.

Taken together, our studies have identified a novel sensor kinase for an Arc two-component system involved in mediating the response to shifts in oxygen levels. Further studies will focus on the role of the additional domains and address the question of whether other signals can be received and integrated into regulating the phosphorylation level of ArcA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Penelope Higgs for critically reading the manuscript and helpful discussions. We are also grateful to the group of Martin Thanbichler and Albert Schweitzer for kindly providing plasmids pNTPS-138 and pUC18R6KT-mini-Tn7T, respectively. We thank the groups of Lotte Søgaard-Andersen and Penelope Higgs for assistance with protein production and phosphpotransfer studies and Febit Biomed GmbH for assistance with the microarray data analysis.

This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG TH-831) and the Max Planck Gesellschaft.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 March 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiba, H., S. Adhya, and B. de Crombrugghe. 1981. Evidence for two functional gal promoters in intact Escherichia coli cells. J. Biol. Chem. 256:11905-11910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiyar, A., Y. Xiang, and J. Leis. 1996. Site-directed mutagenesis using overlap extension PCR. Methods Mol. Biol. 57:177-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexeeva, S., B. de Kort, G. Sawers, K. J. Hellingwerf, and M. J. de Mattos. 2000. Effects of limited aeration and of the ArcAB system on intermediary pyruvate catabolism in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 182:4934-4940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexeeva, S., K. J. Hellingwerf, and M. J. Teixeira de Mattos. 2002. Quantitative assessment of oxygen availability: perceived aerobiosis and its effect on flux distribution in the respiratory chain of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:1402-1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexeeva, S., K. J. Hellingwerf, and M. J. Teixeira de Mattos. 2003. Requirement of ArcA for redox regulation in Escherichia coli under microaerobic but not anaerobic or aerobic conditions. J. Bacteriol. 185:204-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balch, W. E., and R. S. Wolfe. 1976. New approach to the cultivation of methanogenic bacteria: 2-mercaptoethanesulfonic acid (HS-CoM)-dependent growth of Methanobacterium ruminantium in a pressurized atmosphere. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 32:781-791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baraquet, C., L. Theraulaz, C. Iobbi-Nivol, V. Mejean, and C. Jourlin-Castelli. 2009. Unexpected chemoreceptors mediate energy taxis towards electron acceptors in Shewanella oneidensis. Mol. Microbiol. 73:278-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baum, M., S. Bielau, N. Rittner, K. Schmid, K. Eggelbusch, M. Dahms, A. Schlauersbach, H. Tahedl, M. Beier, R. Guimil, M. Scheffler, C. Hermann, J. M. Funk, A. Wixmerten, H. Rebscher, M. Honig, C. Andreae, D. Buchner, E. Moschel, A. Glathe, E. Jäger, M. Thom, A. Greil, F. Bestvater, F. Obermeier, J. Burgmaier, K. Thome, S. Weichert, S. Hein, T. Binnewies, V. Foitzik, M. Müller, C. F. Stahler, and P. F. Stahler. 2003. Validation of a novel, fully integrated and flexible microarray benchtop facility for gene expression profiling. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:e151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bekker, M., S. Alexeeva, W. Laan, G. Sawers, J. Teixeira de Mattos, and K. Hellingwerf. 2010. The ArcBA two-component system of Escherichia coli is regulated by the redox state of both the ubiquinone and the menaquinone pool. J. Bacteriol. 192:746-754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beliaev, A. S., D. K. Thompson, M. W. Fields, L. Wu, D. P. Lies, K. H. Nealson, and J. Zhou. 2002. Microarray transcription profiling of a Shewanella oneidensis etrA mutant. J. Bacteriol. 184:4612-4616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charania, M. A., K. L. Brockman, Y. Zhang, A. Banerjee, G. E. Pinchuk, J. K. Fredrickson, A. S. Beliaev, and D. A. Saffarini. 2009. Involvement of a membrane-bound class III adenylate cyclase in regulation of anaerobic respiration in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. J. Bacteriol. 191:4298-4306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi, K. H., J. B. Gaynor, K. G. White, C. Lopez, C. M. Bosio, R. R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, and H. P. Schweizer. 2005. A Tn7-based broad-range bacterial cloning and expression system. Nat. Methods 2:443-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fic, E., P. Bonarek, A. Gorecki, S. Kedracka-Krok, J. Mikolajczak, A. Polit, M. Tworzydlo, M. Dziedzicka-Wasylewska, and Z. Wasylewski. 2009. cAMP receptor protein from Escherichia coli as a model of signal transduction in proteins—a review. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 17:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao, H., X. Wang, Z. K. Yang, T. Palzkill, and J. Zhou. 2008. Probing regulon of ArcA in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 by integrated genomic analyses. BMC Genomics 9:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao, H., Y. Wang, X. Liu, T. Yan, L. Wu, E. Alm, A. Arkin, D. K. Thompson, and J. Zhou. 2004. Global transcriptome analysis of the heat shock response of Shewanella oneidensis. J. Bacteriol. 186:7796-7803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Georgellis, D., O. Kwon, P. De Wulf, and E. C. Lin. 1998. Signal decay through a reverse phosphorelay in the Arc two-component signal transduction system. J. Biol. Chem. 273:32864-32869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Georgellis, D., O. Kwon, and E. C. Lin. 2001. Quinones as the redox signal for the arc two-component system of bacteria. Science 292:2314-2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Georgellis, D., O. Kwon, E. C. Lin, S. M. Wong, and B. J. Akerley. 2001. Redox signal transduction by the ArcB sensor kinase of Haemophilus influenzae lacking the PAS domain. J. Bacteriol. 183:7206-7212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Georgellis, D., A. S. Lynch, and E. C. Lin. 1997. In vitro phosphorylation study of the arc two-component signal transduction system of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:5429-5435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gralnick, J. A., C. T. Brown, and D. K. Newman. 2005. Anaerobic regulation by an atypical Arc system in Shewanella oneidensis. Mol. Microbiol. 56:1347-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green, J., J. C. Crack, A. J. Thomson, and N. E. LeBrun. 2009. Bacterial sensors of oxygen. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12:145-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guzman, L. M., D. Belin, M. J. Carson, and J. Beckwith. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121-4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hau, H. H., and J. A. Gralnick. 2007. Ecology and biotechnology of the genus Shewanella. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61:237-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heidelberg, J. F., I. T. Paulsen, K. E. Nelson, E. J. Gaidos, W. C. Nelson, T. D. Read, J. A. Eisen, R. Seshadri, N. Ward, B. Methe, R. A. Clayton, T. Meyer, A. Tsapin, J. Scott, M. Beanan, L. Brinkac, S. Daugherty, R. T. DeBoy, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, D. H. Haft, J. F. Kolonay, R. Madupu, J. D. Peterson, L. A. Umayam, O. White, A. M. Wolf, J. Vamathevan, J. Weidman, M. Impraim, K. Lee, K. Berry, C. Lee, J. Mueller, H. Khouri, J. Gill, T. R. Utterback, L. A. McDonald, T. V. Feldblyum, H. O. Smith, J. C. Venter, K. H. Nealson, and C. M. Fraser. 2002. Genome sequence of the dissimilatory metal ion-reducing bacterium Shewanella oneidensis. Nat. Biotechnol. 20:1118-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hochberg, Y. 1988. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika 75:800-802. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inoue, H., H. Nojima, and H. Okayama. 1990. High efficiency transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. Gene 96:23-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iuchi, S., and E. C. Lin. 1988. arcA (dye), a global regulatory gene in Escherichia coli mediating repression of enzymes in aerobic pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 85:1888-1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jagadeesan, S., P. Mann, C. W. Schink, and P. I. Higgs. 2009. A novel “four-component” two-component signal transduction mechanism regulates developmental progression in Myxococcus xanthus. J. Biol. Chem. 284:21435-21445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeon, Y., Y. S. Lee, J. S. Han, J. B. Kim, and D. S. Hwang. 2001. Multimerization of phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated ArcA is necessary for the response regulator function of the Arc two-component signal transduction system. J. Biol. Chem. 276:40873-40879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jung, W. S., Y. R. Jung, D. B. Oh, H. A. Kang, S. Y. Lee, M. Chavez-Canales, D. Georgellis, and O. Kwon. 2008. Characterization of the Arc two-component signal transduction system of the capnophilic rumen bacterium Mannheimia succiniciproducens. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 284:109-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karimova, G., J. Pidoux, A. Ullmann, and D. Ladant. 1998. A bacterial two-hybrid system based on a reconstituted signal transduction pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:5752-5756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiley, P. J., and H. Beinert. 1998. Oxygen sensing by the global regulator, FNR: the role of the iron-sulfur cluster. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 22:341-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klipper-Aurbach, Y., M. Wasserman, N. Braunspiegel-Weintrob, D. Borstein, S. Peleg, S. Assa, M. Karp, Y. Benjamini, Y. Hochberg, and Z. Laron. 1995. Mathematical formulae for the prediction of the residual beta cell function during the first two years of disease in children and adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Med. Hypotheses 45:486-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kwon, O., D. Georgellis, and E. C. Lin. 2000. Phosphorelay as the sole physiological route of signal transmission by the arc two-component system of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 182:3858-3862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lapouge, K., M. Schubert, F. H. Allain, and D. Haas. 2008. Gac/Rsm signal transduction pathway of gamma-proteobacteria: from RNA recognition to regulation of social behaviour. Mol. Microbiol. 67:241-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Letunic, I., and P. Bork. 2007. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL): an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Bioinformatics 23:127-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu, X., and P. De Wulf. 2004. Probing the ArcA-P modulon of Escherichia coli by whole genome transcriptional analysis and sequence recognition profiling. J. Biol. Chem. 279:12588-12597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu, X., G. R. Pena Sandoval, B. L. Wanner, W. S. Jung, D. Georgellis, and O. Kwon. 2009. Evidence against the physiological role of acetyl phosphate in the phosphorylation of the ArcA response regulator in Escherichia coli. J. Microbiol. 47:657-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lovley, D. R., D. E. Holmes, and K. P. Nevin. 2004. Dissimilatory Fe(III) and Mn(IV) reduction. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 49:219-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu, S., P. B. Killoran, F. C. Fang, and L. W. Riley. 2002. The global regulator ArcA controls resistance to reactive nitrogen and oxygen intermediates in Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis. Infect. Immun. 70:451-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lynch, A. S., and E. C. Lin. 1996. Transcriptional control mediated by the ArcA two-component response regulator protein of Escherichia coli: characterization of DNA binding at target promoters. J. Bacteriol. 178:6238-6249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maier, T. M., and C. R. Myers. 2001. Isolation and characterization of a Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1 electron transport regulator etrA mutant: reassessment of the role of EtrA. J. Bacteriol. 183:4918-4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malpica, A., G. R. Pena-Sandoval, C. Rodriguez, B. Franco, and D. Georgellis. 2006. Signaling by the Arc two-component system provides a link between the redox state of the quinone pool and gene expression. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 8:781-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Malpica, R., B. Franco, C. Rodriguez, O. Kwon, and D. Georgellis. 2004. Identification of a quinone-sensitive redox switch in the ArcB sensor kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:13318-13323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mika, F., and R. Hengge. 2005. A two-component phosphotransfer network involving ArcB, ArcA, and RssB coordinates synthesis and proteolysis of sigmaS (RpoS) in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 19:2770-2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller, V. L., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1988. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J. Bacteriol. 170:2575-2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Myers, C. R., and J. M. Myers. 1997. Replication of plasmids with the p15A origin in Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 24:221-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Myers, C. R., and K. H. Nealson. 1988. Bacterial manganese reduction and growth with manganese oxide as the sole electron acceptor. Science 240:1319-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nealson, K. H., A. Belz, and B. McKee. 2002. Breathing metals as a way of life: geobiology in action. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 81:215-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nealson, K. H., and J. Scott. 2003. Ecophysiology of the genus Shewanella, p. 1133-1151. In M. Dworkin (ed.), The prokaryotes: an evolving electronic resource for the microbial community. Springer-NY, LLC, New York, NY.

- 53.Nystrom, T., C. Larsson, and L. Gustafsson. 1996. Bacterial defense against aging: role of the Escherichia coli ArcA regulator in gene expression, readjusted energy flux and survival during stasis. EMBO J. 15:3219-3228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paulick, A., A. Koerdt, J. Lassak, S. Huntley, I. Wilms, F. Narberhaus, and K. M. Thormann. 2009. Two different stator systems drive a single polar flagellum in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Mol. Microbiol. 71:836-850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pena-Sandoval, G. R., O. Kwon, and D. Georgellis. 2005. Requirement of the receiver and phosphotransfer domains of ArcB for efficient dephosphorylation of phosphorylated ArcA in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 187:3267-3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Perez, J. C., and E. A. Groisman. 2009. Evolution of transcriptional regulatory circuits in bacteria. Cell 138:233-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perrenoud, A., and U. Sauer. 2005. Impact of global transcriptional regulation by ArcA, ArcB, Cra, Crp, Cya, Fnr, and Mlc on glucose catabolism in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 187:3171-3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pospiech, A., and B. Neumann. 1995. A versatile quick-prep of genomic DNA from gram-positive bacteria. Trends Genet. 11:217-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rasmussen, A. A., S. Wegener-Feldbrügge, S. L. Porter, J. P. Armitage, and L. Søgaard-Andersen. 2006. Four signalling domains in the hybrid histidine protein kinase RodK of Myxococcus xanthus are required for activity. Mol. Microbiol. 60:525-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saffarini, D. A., R. Schultz, and A. Beliaev. 2003. Involvement of cyclic AMP (cAMP) and cAMP receptor protein in anaerobic respiration of Shewanella oneidensis. J. Bacteriol. 185:3668-3671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Salmon, K. A., S. P. Hung, N. R. Steffen, R. Krupp, P. Baldi, G. W. Hatfield, and R. P. Gunsalus. 2005. Global gene expression profiling in Escherichia coli K12: effects of oxygen availability and ArcA. J. Biol. Chem. 280:15084-15096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sambrook, K., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 63.Sengupta, N., K. Paul, and R. Chowdhury. 2003. The global regulator ArcA modulates expression of virulence factors in Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 71:5583-5589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shi, X., S. Wegener-Feldbrügge, S. Huntley, N. Hamann, R. Hedderich, and L. Søgaard-Andersen. 2008. Bioinformatics and experimental analysis of proteins of two-component systems in Myxococcus xanthus. J. Bacteriol. 190:613-624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smith, T. F., and M. S. Waterman. 1981. Identification of common molecular subsequences. J. Mol. Biol. 147:195-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stamatakis, A., P. Hoover, and J. Rougemont. 2008. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML Web servers. Syst. Biol. 57:758-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stock, A. M., V. L. Robinson, and P. N. Goudreau. 2000. Two-component signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:183-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Taylor, B. L., and I. B. Zhulin. 1999. PAS domains: internal sensors of oxygen, redox potential, and light. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:479-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thormann, K. M., S. Duttler, R. M. Saville, M. Hyodo, S. Shukla, Y. Hayakawa, and A. M. Spormann. 2006. Control of formation and cellular detachment from Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 biofilms by cyclic di-GMP. J. Bacteriol. 188:2681-2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thormann, K. M., R. M. Saville, S. Shukla, D. A. Pelletier, and A. M. Spormann. 2004. Initial phases of biofilm formation in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. J. Bacteriol. 186:8096-8104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thormann, K. M., R. M. Saville, S. Shukla, and A. M. Spormann. 2005. Induction of rapid detachment in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 187:1014-1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Venkateswaran, K., D. P. Moser, M. E. Dollhopf, D. P. Lies, D. A. Saffarini, B. J. MacGregor, D. B. Ringelberg, D. C. White, M. Nishijima, H. Sano, J. Burghardt, E. Stackebrandt, and K. H. Nealson. 1999. Polyphasic taxonomy of the genus Shewanella and description of Shewanella oneidensis sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49(Pt. 2):705-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang, F., J. Wang, H. Jian, B. Zhang, S. Li, X. Zeng, L. Gao, D. H. Bartlett, J. Yu, S. Hu, and X. Xiao. 2008. Environmental adaptation: genomic analysis of the piezotolerant and psychrotolerant deep-sea iron reducing bacterium Shewanella piezotolerans WP3. PLoS One 3:e1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wong, S. M., K. R. Alugupalli, S. Ram, and B. J. Akerley. 2007. The ArcA regulon and oxidative stress resistance in Haemophilus influenzae. Mol. Microbiol. 64:1375-1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xu, Q., S. W. Porter, and A. H. West. 2003. The yeast YPD1/SLN1 complex: insights into molecular recognition in two-component signaling systems. Structure 11:1569-1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ziemke, F., I. Brettar, and M. G. Höfle. 1997. Stability and diversity of the genetic structure of a Shewanella putrefaciens population in the water column of the Central Baltic. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 13:63-74. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.