Abstract

The Knops blood group antigen erythrocyte polymorphisms have been associated with reduced falciparum malaria-based in vitro rosette formation (putative malaria virulence factor). Having previously identified single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the human complement receptor 1 (CR1/CD35) gene underlying the Knops antithetical antigens Sl1/Sl2 and McCa/McCb, we have now performed genotype comparisons to test associations between these two molecular variants and severe malaria in West African children living in the Gambia. While SNPs associated with Sl:2 and McC(b+) were equally distributed among malaria-infected children with severe malaria and control children not infected with malaria parasites, high allele frequencies for Sl 2 (0.800, 1365/1706) and McCb (0.385, 658/1706) were observed. Further, when compared to the Sl 1/McCa allele observed in all populations, the African Sl 2/McCb allele appears to have evolved as a result of positive selection (modified Nei–Gojobori test Ka−Ks/s.e. = 1.77, P-value <0.05). Given the role of CR1 in host defense, our findings suggest that Sl 2 and McCb have arisen to confer a selective advantage against infectious disease that, in view of these case–control study data, was not solely Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Factors underlying the lack of association between Sl 2 and McCb with severe malaria may involve variation in CR1 expression levels.

Keywords: malaria, blood groups, single-nucleotide polymorphisms, complement receptor 1 (CR1), evolution

Introduction

Rosette formation resulting from adhesion between Plasmodium falciparum-infected red blood cells (RBC) and uninfected RBC is viewed as a critical in vitro marker of malaria pathogenesis.1 Parasitized RBCs (pRBC) adhere to uninfected RBC (rosetting), other pRBC (autoagglutination), and to endothelial cells lining blood vessels (cytoadherence). In aggregate, it is clear that these adhesive interactions underlie P. falciparum sequestration and are likely to contribute to the obstruction of blood flow and severe malaria. A number of field studies have reported an association between in vitro rosette formation using patient’s cells collected at the time of clinical presentation of malaria illness and cerebral malaria,1,2 severe malarial anemia,3,4 or both cerebral malaria and severe malarial anemia.5-8 Although exceptions to these findings have been reported,9,10 these observations are of interest, as identifying host–parasite molecular partners underlying P. falciparum sequestration may provide direction for developing strategies to block interactions linked to severe malaria pathogenesis that contribute to millions of childhood deaths annually.

Serologic factors have been observed both to promote6,11-14 and disrupt1,2,5 in vitro rosette formation. Additionally, several recent studies have uncovered a complex of molecular relations involving the variant P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein (PfEMP1) family of pRBC surface antigens and a number of different host cell surface proteins in cellular adhesion assays. These studies have described ‘receptor–ligand’ relation between regions of PfEMP1 and CD36, thrombospondin (TSP), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1),15,16 complement receptor 1 (CR1/CD35),17 platelet endothelial adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1/CD31),18 blood group A,19 and heparan sulfate-like molecules20 in a range of cellular adhesion interactions. Of further interest has been the suggestion that these adhesive interactions may work synergistically to induce severe malaria.4

Our recent studies have suggested that low CR1 expression and the Sl:2 phenotype (previously known as Vil+21) are associated with reduced rosetting.17 The Sl:2 phenotype may result from homozygosity for the Sl2 allele, presence of a nonexpressed Sl1 allele (amorph), and/or reduced expression levels of the Sl1 allele that obscure serological typing assays. Through identification of single-nucleotide polymorphisms SNPs in exon 2922 of the CR1 gene, we recently correlated specific amino-acid substitutions in complement control protein (CCP) module 25 (R1601G and K1590E) with Knops Sl:2 and McC(b+) serologic phenotypes, respectively. Here, we have performed genotype comparisons to test associations between these two molecular variants and severe malaria in a well-characterized case–control study of West African children living in the Gambia.23

Results

Consistent with previous studies,22,24,25 we observed a significant elevation of the Sl2 (1601G) and McCb (1590E) alleles in the West African children (Sl2, 0.800, 1365/1706; McCb, 0.386, 658/1706) compared to Caucasian (Sl2, 0.005, 1/200; McCb, 0.000, 0/200), Asian (Sl2, 0.030, 6/198; McCb, 0.020, 4/198), and Hispanic Americans (Sl2, 0.030, 6/200; McCb, 0.025, 5/200) (Sl2 Fisher’s exact test, P-value<0.0001; McCb Fisher’s exact test, P-value<0.0001). Table 1 provides a comparison of genotype frequencies for these same populations. Overall, alleles at both the Sl and McC loci were observed to be in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (Sl χ2 (2 df)=0.079, P-value=0.674; McC χ2 (2 df)=0.005, P-value=0.997) for the Gambian children studied here. As the amino-acid substitution at position 1615 was not observed to influence serological recognition of either McCoy or Swain–Langley antigens,22 and because all study subjects were either homozygous or heterozygous for the mutant allele (1615 V), this polymorphism was not considered in our association studies.

Table 1.

Comparing Sl (R1601G) and McC (K1590E) genotype frequencies: The Gambia vs North American ethnicities

| Ethnic/geographic group | n | R/R a | Freq. | R/G | Freq. | G/G | Freq. | P-value b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sl (R1601G) | ||||||||

| The Gambia | 853 | 40 | 0.047 | 261 | 0.306 | 552 | 0.647 | |

| Caucasian Am | 100 | 99 | 0.990 | 1 | 0.010 | 0 | 0.000 | <0.0001 |

| Asian Am | 99 | 94 | 0.949 | 4 | 0.040 | 1 | 0.010 | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic Am | 100 | 94 | 0.940 | 6 | 0.060 | 0 | 0.000 | <0.0001 |

| McC (K1590E) | n | K/K | Freq. | K/E | Freq. | E/E | Freq. | P-value |

| The Gambia | 853 | 324 | 0.380 | 400 | 0.469 | 129 | 0.151 | |

| Caucasian Am | 100 | 100 | 1.000 | 0 | 0.000 | 0 | 0.000 | <0.0001 |

| Asian Am | 99 | 95 | 0.960 | 4 | 0.040 | 0 | 0.000 | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic Am | 100 | 95 | 0.950 | 5 | 0.050 | 0 | 0.000 | <0.0001 |

Single letter amino-acid sequence nomenclature is used to identify CR1CCP25 alleles (R=arginine, G=glycine, K=lysine, E=glutamic acid).

Fisher’s exact test.

Results in Table 2 show that neither Sl 2 nor McCb alleles separately, or the Sl 2/McCb allele (data not shown) conferred protection against any of the severe malaria phenotypes when malaria-infected children with disease were compared to children classified as ‘non-malaria controls’ (children with mild, mostly infectious, illnesses who did not require hospital admission and did not have any malaria parasites in their blood on microscopy).23 Children classified by a generalized phenotype of severe malaria were further characterized by having one of cerebral malaria (unrousable coma score<3,26 or repeated seizures of >30 min), severe anemia (hemoglobin<5 g/dl on admission), or by a combined category including death or disabling neurological sequelae when discharged from the hospital.27,28 For all comparisons, absence of association between the CR1CCP25 polymorphisms was independent of hemoglobin S in beta globin genotypes (the most significant human polymorphism conferring protection from severe malaria), and other potential confounders (sex, ethnic group, location of residence) (data not shown).

Table 2.

Comparing Sl (R1601G) and McC (K1590E) genotype frequencies for Gambian mild control and severe malaria cohorts

| Malaria phenotype | n | R/R a | Freq. | R/G | Freq. | G/G | Freq. | χ 2 | P-value b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sl (R1601G) | |||||||||

| Nonmalaria controls | 390 | 23 | 0.059 | 128 | 0.328 | 239 | 0.613 | ||

| Malaria (severe) | 463 | 17 | 0.037 | 133 | 0.287 | 313 | 0.676 | 4.7 | 0.095 |

| Cerebral | 331 | 13 | 0.039 | 95 | 0.287 | 223 | 0.674 | 3.4 | 0.182 |

| Anemia | 152 | 4 | 0.026 | 46 | 0.303 | 102 | 0.671 | 3.2 | 0.207 |

| Death or sequelae | 98 | 5 | 0.051 | 33 | 0.337 | 60 | 0.612 | 0.1 | 0.949 |

| McC (K1590E) | n | K/K | Freq. | K/E | Freq. | E/E | Freq. | χ 2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonmalaria controls | 390 | 155 | 0.397 | 171 | 0.438 | 64 | 0.164 | ||

| Malaria (severe) | 463 | 169 | 0.365 | 229 | 0.495 | 65 | 0.140 | 2.8 | 0.247 |

| Cerebral | 331 | 124 | 0.375 | 160 | 0.483 | 47 | 0.142 | 1.6 | 0.450 |

| Anemia | 152 | 55 | 0.362 | 76 | 0.500 | 21 | 0.138 | 1.7 | 0.420 |

| Death or Sequelae | 98 | 40 | 0.408 | 49 | 0.500 | 9 | 0.092 | 3.4 | 0.181 |

Single letter amino-acid sequence nomenclature is used to identify CR1CCP25 alleles (R=arginine, G=glycine, K=lysine, E=glutamic acid).

Fisher’s exact test.

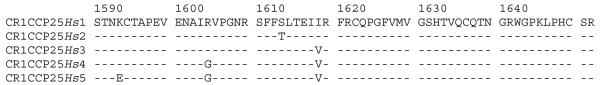

When DNA and amino-acid sequence comparisons were performed among human and Pan troglodytes CR1CCP25 haplotypes, we observed that all SNP led to amino-acid changes (nonsynonymous mutations) in the human alleles, whereas three of four SNP observed in the P. troglodytes CR1CCP25 coding sequence (GenBank Acc#. L24920)29 did not change the amino-acid sequence (synonymous mutations). We then performed pairwise comparisons of the human CR1CCP25 sequences (Figure 1) to determine if evidence for positive or adaptive selection was observed. Results from a modified Nei–Gojobori test suggest that positive selection underlies the accumulation of sequence changes differentiating CR1CCP25Hs1 (Sl1/McCa; all human ethnic/geographic populations) and CR1CCP25Hs5 (Sl2/McCb; African-derived) (Modified Nei–Gojobori (Jukes–Cantor) test (Ka−Ks/s.e. = 0.023/0.013 = 1.77, P-value<0.05).30 Additional evidence supportive of positive selection among human CR1CCP25 haplotypes was also obtained by the McDonald–Kreitman test31 (Fisher’s exact test, two-tailed P-value = 0.03). Together with results from our previous study showing that the amino-acid substitutions at positions 1590 and 1601 are responsible for the serological phenotype differences between McC(a+) vs McC(b+) and Sl:1 vs Sl:2, respectively,22 evidence consistent with positive selection suggests that the CR1CCP25 polymorphisms have evolved to confer some form of selective advantage in African populations.

Figure 1.

Amino-acid sequence alignment comparing CR1CCP25 (Hs) alleles. Standard single-letter nomenclature illustrates the amino-acid sequence for five human CR1CCP25 alleles. This sequence is inclusive of amino acids 1587–1648. Amino-acid identity is represented by a dash (-); polymorphic positions are identified by a variant amino-acid symbol compared to the CR1CCP25Hs1 reference sequence. GenBank accession numbers for each of the human CR1CCP25 alleles include AF264716 (CRlCCP25Hs1), AF264715 (CR1CCP25Hs2), L17408 (CR1CCP25Hs3), AF169969 (CR1CCP25Hs4), and AF169970 (CR1CCP25Hs5).

Discussion

We observed a significant increase in the frequency of genetic polymorphisms associated with the Knops blood group phenotypes Sl:2 and McC(b+) in the Gambian study population living in malarious West Africa compared to non-African US-based populations. Despite the striking increased frequency of Sl2 and McCb in the Gambian study population, we did not observe an association between these African CR1 alleles and protection from severe malaria phenotypes.

To interpret this result, it may be important to consider the influence of erythrocyte CR1 expression polymorphism on the Knops serologic and malaria disease phenotypes. During our studies to identify DNA sequence polymorphisms associated with Sl:2 and McC(b+), we showed that both heterozygosity for the CR1 K1590E (SNP A4795G) and R1601G (SNP A4828G) amino-acid substitutions and erythrocyte CR1 expression polymorphism contributed to genotype-Knops blood group phenotype discordance in 18% of Malians studied.22 With this in mind, we examined further the associations between Sl and McC genotypes and severe malaria by excluding heterozygous individuals from our analyses; however, again no significant associations between Sl2/McCb alleles and severe malaria phenotypes were observed (data not shown).

Bellamy et al32 have surveyed the same Gambian population studied here for a CR1 intron 27 Hind III polymorphism associated with CR1 expression level differences to determine if the low expression-associated allele would confer reduced susceptibility to severe malaria. Although no significant association was observed between the HindIII low expression-associated allele and protection from severe malaria,32 it is important to consider the relationship between this polymorphism and CR1 expression in different ethnic groups. While a number of studies have observed an association between the HindIII low-expression-associated allele and reduced CR1 expression in Caucasians, Herrera et al33 found no association between this marker and CR1 expression in African Americans. Similar lack of association between CR1 expression and the CR1 intron 27 Hind III polymorphism has now been observed in a study population from Mali.34 Given the observed inconsistencies between CR1 genetic and expression phenotype polymorphisms, efforts to determine how erythrocyte CR1 expression differences contribute to in vitro rosetting and severe malaria would require assessing erythrocyte CR1 density using freshly collected blood samples not available for this retrospective study.

We have therefore confronted an interesting, but inevitable limitation of PCR-based field investigations. PCR has enabled innumerable field studies once constrained by difficulties in obtaining sufficient quantities and numbers of fresh blood samples, and by limited supplies of antisera needed for blood group serology. Adhesion between pRBC and uninfected cells may be influenced by amino-acid sequence polymorphism as well as differences in CR1 protein expression. Therefore, DNA-based studies may be limited in detecting associations between critical molecular polymorphisms and disease-related phenotypes.

It will also be important to keep in mind the potentially complex molecular interactions between the highly polymorphic P. falciparum ligand, PfEMP1, and CR1. The C3b binding site (recognized by the mAb J3B11) has recently been identified as the region of CR1 necessary for P. falciparum rosetting.35 Interestingly, this region does not contain either Sl2 or McCb polymorphisms. Using a number of P. falciparum laboratory strains (n = 4) and field isolates from Kenya (n = 15) and Malawi (n = 10), it was shown that blocking interactions between erythrocyte-CR1 and P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes is consistently efficacious in inhibiting rosette formation and therefore not limited to one specific PfEMP1 sequence.35 Thus, although initial characterization of CR1-PfEMP1 involvement with in vitro rosette formation relied upon a portion of a single PfEMP1 allele, this further study suggests that this host receptor–parasite ligand interaction may be a common biological mechanism responsible for adhesion between P. falciparum-infected and uninfected erythrocytes. Therefore, through an improved understanding of factors that might inhibit erythrocyte-CR1–P. falciparum interactions in vitro, it may be possible to develop therapeutic agents to limit or eliminate severe falciparum malaria pathogenesis.

Numerous microbial pathogens, in addition to P. falciparum, contribute to the infectious burden on African populations. The worldwide distribution of the Sl1/McCa haplotype suggests that this apparent ancestral allele may have been carried by human populations migrating out of Africa between 60 000 and 100 000 years ago. The observed restriction of the Sl2/McCb haplotype within African populations suggests that this haplotype has emerged within African populations after this time period. Sequence comparisons between the human and chimpanzee CR1CCP25 domains, in general, and between the CR1 Sl1/McCa (all human ethnic/geographic populations) and Sl2/McCb (African-derived) domains suggest that this region of CR1 and resulting conformations22 have evolved under adaptive selection pressure. This hypothesis could be tested more completely after more extensive DNA sequence analysis of the human CR1 locus using linkage analysis approaches recently described by Sabeti et al.36 Since Sl2/McCb appears to be advancing toward fixation in African populations (Table 1), and considering the important role CR1 plays in regulating immunity and host defense37 this polymorphism has probably been elevated in frequency by infectious disease that, in view of these case–control study data, was not solely P. falciparum malaria.

Methods

Sample preparation

Samples analyzed here have been described previously.23,38 Overall this was a hospital-based case–control study of children categorized according to malaria infection/disease severity as nonmalaria cases with other mild illnesses (nonmalaria controls; n = 390; average age = 2.47 years) or cases of severe malaria (n = 463; average age = 3.43 years).23 Subgroups of severe included cerebral malaria (n = 331 average age = 3.78 years), severe anemia (n = 152; average age = 2.19 years), and death or neurological sequelae (n = 98; average age = 3.53 years). Differences observed for the number of individuals studied here compared to previous studies arose based upon the availability of sufficient genomic DNA, efficiency of PCR and resolution of CR1 genotyping assay results. Samples representing North American ethnic groups have been described previously.38 Briefly, anonymous donors were between 18 and 55 years of age and were classified by self-identified ethnicity. No information regarding exposure to malaria parasites or other infectious diseases was available. Sample collection from pediatric patients from the Gambia was performed following protocols approved by the Gambian government/MRC joint ethical committee and permission from each child’s parent or guardian. Sample collection from random blood donors was performed following protocols approved by the American Red Cross.

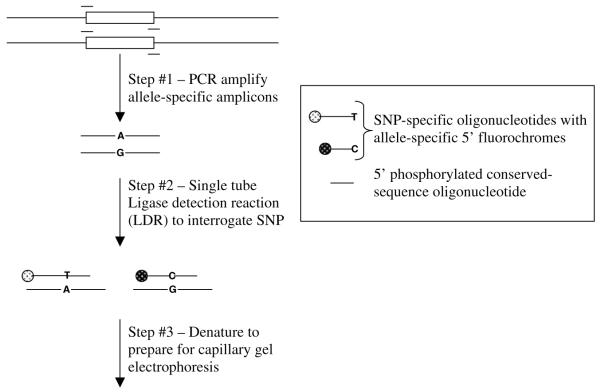

CR1 genotyping using post-PCR multiplexed ligation detection reaction (LDR)

A 476 bp fragment of CR1 containing three polymorphic sites was PCR amplified using the primers 5′-TAAAAAATAAGCTGTTTTACCATACTC and 5′-CCCTCACACCCAGCAAAGTC (Figure 1). Amplifications were performed in a total volume of 25 μl and contained 10 mm Tris-HCl pH 8.3, 50 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 200 μm of each dNTP, 0.2 μm of each primer, approximately 50 ng DNA, and 0.5 U of Amplitaq Gold polymerase (Perkin-Elmer). To prevent polymerase extension during the subsequent LDR procedure, residual polymerase activity was removed by incubation with 1/10 volume of 1 mg/ml proteinase K in 50 mm EDTA at 37°C for 30 min, 55°C 10 min. The proteinase K was inactivated by incubation at 99°C for 10 min.

A set of three LDR probes consisting of two fluorescently labelled allelic and one common probe was designed for each of the SNPs occurring at nucleotide positions 4795, 4828, and 4870 (Table 3, Figure 2). The common probes (100 pmol of each) were 5′ phosphorylated in a volume of 100 μl using 10 U of T4 polynucleotide kinase and 1 mm ATP in 70 mm Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.6 containing 10 mm MgCl2 and 5 mm dithiothreitol. After incubation at 37°C for 45 min, the T4 kinase was inactivated by the addition of 20 μg of proteinase K in 100 μl of TE buffer (10 mm Tris/HCl and 5 mm EDTA pH 8.0) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The proteinase K was inactivated by incubation at 99°C for 10 min.

Table 3.

CR1 exon 29a-specific ligase detection reaction genotyping assay probes

| LDR probes | LDR probe sequence | Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| 4795A | FAM-aataCAGCCCTCCCCCTCGGTGTATTTCTACTAATA | 71 |

| 4795G | HEX-ataaAGCCCTCCCCCTCGGTGTATTTCTACTAATG | 70 |

| 4795com | AATGCACAGCTCCAGAAGTTGAAAATGCAATatat | |

| 4828Crev | HEX-GAGGGAAAAGAAACTCCTGTTTCCTGGTACTCC | 65 |

| 4828Trev | FAM-GTGAGGGAAAAGAAACTCCTGTTTCCTGGTACTCT | 67 |

| 4828revcom | AATTGCATTTTCAACTTCTGGAGCTGTGCATT | |

| 4870G | FAM-AAACAGGAGTTTCTTTTCCCTCACTGAGATCG | 61 |

| 4870A | HEX-GAAACAGGAGTTTCTTTTCCCTCACTGAGATCA | 62 |

| 4870com | TCAGATTTAGATGTCAGCCCGGGTTTGTC |

Exon 29 encodes CR1CCPs 24 and 25.

Figure 2.

Post-PCR ligase detection reaction (LDR) genotyping assay.

Multiplexed LDR was performed in 15 μl volumes of 20 mm Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.6 containing 25 mm KCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 1mm NAD+, 10mm DTT, 0.1% Triton X-100, 10 nm (200 fmol) of each LDR probe, 2 μl of PCR product, and 2 U of Taq DNA ligase. The reactions were prepared on ice and then hot-started by placing on PCR blocks preheated to 95°C. An initial 1 min denaturation at 95°C was followed by 15 thermal cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s, annealing and ligation at 68°C for 4 min. The activity of the ligase was stopped after 15 cycles by cooling to 4°C and adding 2 μl of 100 mm EDTA.

Electrophoresis and detection of LDR products was performed on an ABI 3700 fluorescent DNA sequencer. To 1 μl of LDR product was added 10 μl Hi Di formamide and 0.01 μl of 8 nm ABI Genescan-500 Rox size standards. Product sizes were calculated relative to the standard by Genescan 3.5 using the second-order least-squares method. Automated allele calling of LDR products was performed using Genotyper 2.5 and standardized by assays performed on amplicons from cloned and sequenced allele-specific controls.

Hemoglobin (Hb) A/S genotyping

For individual samples lacking analysis of Hb A/S status, genotyping was performed following methods developed by Husain et al.39 In these analyses, numerous samples examined previously were included.23 All samples assayed in this, and the former study produced results that were 100% concordant (data not shown).

Statistical analysis

χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests were performed using Stat View 5.0.1 or SAS 8.02 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Tests comparing nonsynonymous (amino-acid changing; Ka) SNPs vs synonymous (amino-acid non-changing; Ks) between allele-specific sequences were performed using MEGA2 (http://www.megasoftware.net).30 Briefly, modified Nei–Gojobori (Jukes–Cantor) tests were performed for all pairwise sequence comparisons among the human haplotypes reported in Figure 1 to determine the difference (Ka−Ks); standard errors (s.e.) were computed based upon 1000 bootstrap replicates. A further one-tailed Z-test (D/σ) was performed to determine the significance of each pairwise difference: Ka−Ks/(s.e.) where a score ≥1.6 attains a P-value of <0.05. An additional test of positive/adaptive selection was conducted by performing a McDonald–Kreitman test comparing the five human CR1CCP25 haplotypes with that for P. troglodytes (GenBank Acc# L24920).29 This test was performed using DnaSP 3.53 (http://www.ub.es/dnasp).40

Acknowledgements

We thank L Miller, AG Palmer III, M Johnson, and E Eichler for helpful discussions during this study, and B Greenwood, D Kwiatkowski, CEM Allsopp, S Bennett, and N Anstey who contributed to conduct and design of the original case–control study. Funding support was provided by the National Institutes of Health (AI R01 42367 (JMM) and the Wellcome Trust (AVSH is a Wellcome Trust Principal Research Fellow and 055167 (JAR)).

Footnotes

Nomenclature for the Knops blood group Swain–Langley has been updated at the International Society of Blood Transfusion Nomenclature Committee meeting, 27th Congress of the ISBT, Vancouver, British Columbia as follows. The Swain–Langley-positive phenotype and antigen previously referred to as Sl(a+) and Sla are now Sl:1 and Sl1, respectively; the allele Sla is now Sl 1. The antithetical phenotype and antigen previously referred to as Vil+ and Vil are now Sl:2 and Sl2, respectively; the allele Vil, is now Sl 2. Nomenclature for the Knops blood group, McCoy phenotype, antigen, and allele are McC(a+), McCa, McCa, and McC(b+), McCb, McCb (Geoff Daniels, personal communication).

References

- 1.Carlson J, et al. Human cerebral malaria: association with erythrocyte rosetting and lack of anti-rosetting antibodies. Lancet. 1990;336:1457–1460. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)93174-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Treutiger CJ, et al. Rosette formation in Plasmodium falciparum isolates and anti-rosette activity of sera from Gambians with cerebral or uncomplicated malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;46:503–510. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.46.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newbold C, et al. Receptor-specific adhesion and clinical disease in Plasmodium falciparum. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:389–398. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.57.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heddini A, et al. Fresh isolates from children with severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria bind to multiple receptors. Infect Immun. 2001;69:5849–5856. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5849-5856.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rowe A, Obeiro J, Newbold CI, Marsh K. Plasmodium falciparum rosetting is associated with malaria severity in Kenya. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2323–2326. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2323-2326.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowe JA, Shafi M, Kai O, Marsh K, Raza A. Nonimmune IgM but not IgG binds to the surface of Plasmodium falciparum infected erythrocytes and correlates with rosetting and severe malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.692. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ringwald P, et al. Parasite virulence factors during falciparum malaria: rosetting, cytoadherence, and modulation of cytoadherence by cytokines. Infect Immun. 1993;61:5198–5204. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.5198-5204.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kun JF, et al. Merozoite surface antigen 1 and 2 genotypes and rosetting of Plasmodium falciparum in severe and mild malaria in Lambarene, Gabon. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:110–114. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(98)90979-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.al-Yaman F, et al. Human cerebral malaria: lack of significant association between erythrocyte rosetting and disease severity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89:55–58. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(95)90658-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogerson SJ, et al. Cytoadherence characteristics of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes from Malawian children with severe and uncomplicated malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:467–472. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scholander C, Treutiger CJ, Hultenby K, Wahlgren M. Novel fibrillar structure confers adhesive property to malaria-infected erythrocytes. Nat Med. 1996;2:204–208. doi: 10.1038/nm0296-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clough B, Atilola FA, Black J, Pasvol G. Plasmodium falciparum: the importance of IgM in the rosetting of parasite-infected erythrocytes. Exp Parasitol. 1998;89:129–132. doi: 10.1006/expr.1998.4275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Treutiger CJ, Carlson J, Scholander C, Wahlgren M. The time course of cytoadhesion, immunoglobulin binding, rosette formation, and serum-induced agglutination of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:202–207. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Somner EA, Black J, Pasvol G. Multiple human serum components act as bridging molecules in rosette formation by Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Blood. 2000;95:674–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baruch DI, Gormely JA, Ma C, Howard RJ, Pasloske BL. Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 is a parasitized erythrocyte receptor for adherence to CD36, thrombospondin, and intercellular adhesion molecule 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3497–3502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardner JP, Pinches RA, Roberts DJ, Newbold CI. Variant antigens and endothelial receptor adhesion in Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3503–3508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rowe JA, Moulds JM, Newbold CI, Miller LH. P. falciparum rosetting mediated by a parasite-variant erythrocyte membrane protein and complement-receptor 1. Nature. 1997;388:292–295. doi: 10.1038/40888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Treutiger CJ, Heddini A, Fernandez V, Muller WA, Wahlgren M. PECAM-1/CD31, an endothelial receptor for binding Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Nat Med. 1997;3:1405–1408. doi: 10.1038/nm1297-1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barragan A, Kremsner PG, Wahlgren M, Carlson J. Blood group A antigen is a coreceptor in Plasmodium falciparum rosetting. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2971–2975. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2971-2975.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barragan A, Fernandez V, Chen Q, von Euler A, Wahlgren M, Spillmann D. The duffy-binding-like domain 1 of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) is a heparan sulfate ligand that requires 12 mers for binding. Blood. 2000;95:3594–3599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moulds JM, et al. Expansion of the Knops blood group system and subdivision of Sl(a) Transfusion. 2002;42:251–256. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2002.00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moulds JM, Zimmerman PA, Doumbo OK, et al. Molecular identification of Knops blood group polymorphisms found in long homologous region D of complement receptor 1. Blood. 2001;97:2879–2885. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.9.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hill AV, Allsopp CE, Kwiatkowski D, et al. Common west African HLA antigens are associated with protection from severe malaria. Nature. 1991;352:595–600. doi: 10.1038/352595a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moulds MK. Serological investigation and clinical significance of high-titer, low-avidity (HTLA) antibodies. Am J Med Technol. 1981;47:789–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moulds JM, Kassambara L, Middleton JJ, et al. Identification of complement receptor one (CR1) polymorphisms in west Africa. Genes Immun. 2000;1:325–329. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molyneux ME, Taylor TE, Wirima JJ, Borgstein A. Clinical features and prognostic indicators in paediatric cerebral malaria: a study of 131 comatose Malawian children. Q J Med. 1989;71:441–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brewster DR, Kwiatkowski D, White NJ. Neurological sequelae of cerebral malaria in children. Lancet. 1990;336:1039–1043. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92498-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGuire W, Hill AV, Allsopp CE, Greenwood BM, Kwiatkowski D. Variation in the TNF-alpha promoter region associated with susceptibility to cerebral malaria. Nature. 1994;371:508–510. doi: 10.1038/371508a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Birmingham DJ, Shen XP, Hourcade D, Nickells MW, Atkinson JP. Primary sequence of an alternatively spliced form of CR1. Candidate for the 75 000 M(r) complement receptor expressed on chimpanzee erythrocytes. J Immunol. 1994;153:691–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar S, Tamura K, Jakobsen IB, Nei M. MEGA2: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Software. 2001 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDonald JH, Kreitman M. Adaptive protein evolution at the Adh locus in Drosophila. Nature. 1991;351:652–654. doi: 10.1038/351652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bellamy R, Kwiatkowski D, Hill AV. Absence of an association between intercellular adhesion molecule 1, complement receptor 1 and interleukin 1 receptor antagonist gene polymorphisms and severe malaria in a West African population. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:312–316. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(98)91026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herrera AH, Xiang L, Martin SG, Lewis J, Wilson JG. Analysis of complement receptor type 1 (CR1) expression on erythrocytes and of CR1 allelic markers in Caucasian and African American populations. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;87:176–183. doi: 10.1006/clin.1998.4529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rowe JA, Raza A, Diallo DA, et al. Erythrocyte complement receptor 1 expression levels do not correlate with a Hind III restriction fragment length polymorphism in Africans: implications for studies on malaria susceptibility. Genes Immun. 2002;3:497–500. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rowe JA, Rogerson SJ, Raza A, et al. Mapping of the region of complement receptor (CR) 1 required for Plasmodium falciparum rosetting and demonstration of the importance of CR1 in rosetting in field isolates. J Immunol. 2000;165:6341–6346. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sabeti PC, Reich DE, Higgins JM, et al. Detecting recent positive selection in the human genome from haplotype structure. Nature. 2002;419:832–837. doi: 10.1038/nature01140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krych-Goldberg M, Atkinson JP. Structure-function relationships of complement receptor type 1. Immunol Rev. 2001;180:112–122. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1800110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zimmerman PA, Buckler-White A, Alkhatib G, et al. Inherited resistance to HIV-1 conferred by an inactivating mutation in CC chemokine receptor 5: studies in populations with contrasting clinical phenotypes, defined racial background, and quantified risk. Mol Med. 1997;3:23–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Husain SM, Kalavathi P, Anandaraj MP. Analysis of sickle cell gene using polymerase chain reaction & restriction enzyme Bsu 361. Indian J Med Res. 1995;101:273–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rozas J, Rozas R. DnaSP version 3: an integrated program for molecular population genetics and molecular evolution analysis. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:174–175. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]