Abstract

Prion diseases are fatal neurodegenerative diseases resulting from misfolding of normal cellular prion (PrPC) into an abnormal form of scrapie prion (PrPSc). The cellular mechanisms underlying the misfolding of PrPC are not well understood. Since cellular prion proteins harbor divalent metal-binding sites in the N-terminal region, we examined the effect of manganese on PrPC processing in in vitro models of prion disease. Exposure to manganese significantly increased PrPC levels both in cytosolic and in membrane-rich fractions in a time-dependent manner. Manganese-induced PrPC upregulation was independent of messenger RNA transcription or stability. Additionally, manganese treatment did not alter the PrPC degradation by either proteasomal or lysosomal pathways. Interestingly, pulse-chase analysis showed that the PrPC turnover rate was significantly altered with manganese treatment, indicating increased stability of PrPC with the metal exposure. Limited proteolysis studies with proteinase-K further supported that manganese increases the stability of PrPC. Incubation of mouse brain slice cultures with manganese also resulted in increased prion protein levels and higher intracellular manganese accumulation. Furthermore, exposure of manganese to an infectious prion cell model, mouse Rocky Mountain Laboratory–infected CAD5 cells, significantly increased prion protein levels. Collectively, our results demonstrate for the first time that divalent metal manganese can alter the stability of prion proteins and suggest that manganese-induced stabilization of prion protein may play a role in prion protein misfolding and prion disease pathogenesis.

Keywords: metals, neurotoxicity, manganese, scrapie, environmental factors, prion accumulation

Prion diseases are fatal neurodegenerative disorders affecting humans (Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease), cattle (bovine spongiform encephalopathy [BSE]), deer (chronic wasting disease), goat, and sheep (scrapie). Regions of the brain that control motor function, including the basal ganglia, cerebral cortex, thalamus, brain stem, and cerebellum, are severely affected in prion diseases. The major neurological symptoms are extrapyramidal motor signs, including tremors, ataxia, and myoclonus (Aguzzi and Heikenwalder, 2006; Johnson, 2005). Neuropathological changes include vacuolation of neutropils, neuronal loss, and gliosis in brains of diseased animals and humans (Collinge and Palmer, 1992; Palmer and Collinge, 1992). Once thought to be caused by a virus-like particle, prion diseases were later proven to be caused by an abnormal conformation of a host prion protein (Chatigny and Prusiner, 1980). Normal prion protein (PrPC) is a cell surface glycoprotein expressed predominantly in the central nervous system and converted to the proteinase-resistant aggregate form (PrPSc) during the disease state (Collinge, 2005; Prusiner and Kingsbury, 1985). Neuropathological characterization of prion disease involves massive neuronal degeneration associated with accumulation of the abnormal prion protein PrPSc derived from the normal prion protein PrPC (Collinge, 2005; Ma and Lindquist, 2002). However, still the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the conversion of the normal form of PrPC into the proteinase-K (PK)–resistant diseased form PrPSc are yet to be identified.

Although normal cellular prion protein PrPC is highly expressed in the brain, the endogenous function of this protein has not been completely elucidated. PrPC has been suggested to function as an antioxidant, a cellular adhesion molecule, a signal transducer, and a metal-binding protein (Chiarini et al., 2002). While the function of PrPC is not well defined, the hallmark of prion disease is conversion of the soluble form of normal prion protein to the insoluble β-sheet-rich and infectious form through a still unknown mechanism (Prusiner and Kingsbury, 1985). PrPC is a cell surface protein linked via a glycosyl phosphoinositol anchor, with two N-linked glycosylations, and a disulfide bridge. PrPC contains several octapeptide repeat sequences (PHGGSWGQ) toward the N-terminus that have high binding affinity for divalent metals, such as copper, manganese, and zinc, and preferential binding for copper (Cu) (Brown, 2009; Hornshaw et al., 1995). The antioxidant properties of PrPC have been linked to Cu residency in the octapeptide repeat domain (Brown, 2009). Loss of this antioxidant activity has been linked to neurodegeneration seen in prion disease. Furthermore, the metal-binding sites have been suggested to play a role in the pathogenesis of prion diseases (Brown, 2009; Hornshaw et al., 1995; Moore et al., 2006). PrPC is believed to play a role in iron homeostasis, and iron binding to prion protein apparently affects the conversion to a protease-resistant form of prion protein (Singh et al., 2009). Interestingly, altered manganese (Mn) content has been observed in the blood and brain of humans infected with the prion disease Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD), in mice infected with scrapie, and in cattle infected with BSE (Brown, 2009). Additionally, manganese-bound PrPSc can be isolated from both humans and animals infected with prion disease. Despite these findings, the role of manganese in the pathogenesis of prion disease is currently unknown.

Recently, we studied the effect of Mn on oxidative stress, mitochondrial function, cellular antioxidants, proteasomal function, and protein aggregation in cell culture models of prion diseases (Choi et al., 2006, 2007). We have demonstrated that normal prion protein reduces manganese transport and protects the cells from manganese-induced oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular antioxidant depletion, and apoptosis, suggesting that normal cellular prion interacts with manganese and protects cells from manganese neurotoxicity at early stages of exposure (Choi et al., 2006, 2007). We also reported that PrPC protects against apoptotic cell death during oxidative stress but exacerbates apoptosis during endoplasmic reticular (ER) stress (Anantharam et al., 2008). While studying the role of prion protein in metal neurotoxicity, we unexpectedly found that manganese exposure upregulated cellular prion protein in neuronal cell models. Therefore, in the present study, we systematically characterized mechanisms underlying manganese-induced prion protein accumulation and its biological relevance using mouse cell culture models and brain slices.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies.

Manganese chloride (MnCl2), MG-132, and phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF) were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO); PMSF protease inhibitor cocktail was purchased form Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN); and Bradford Protein Assay Kit was purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM), Opti-MEM, fetal bovine serum (FBS), L-glutamine, penicillin, Trypsin/ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and streptomycin were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA); PK was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). DRAQ5 nuclear stain was purchased from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA). ECL chemiluminescence kit and [35S]-methionine were purchased from Amersham (Piscataway, NJ). Monoclonal mouse anti-PrP (3F4) antibody recognizing sequences 109 through 112 in hamster and human PrP was purchased from Signet Labs (Berkeley, CA). Monoclonal mouse anti-PrP (SAF32) antibody recognizing murine PrP was purchased from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI). Antiubiquitin polyclonal antibody was purchased from DAKO Cytomation (Carpinteria, CA). β-actin antibody was purchased from Sigma.

Cell culture.

Mouse neuronal cells expressing mouse prion protein with 3F4-hamster epitope (PrPC), kindly provided by Dr Suzette Priola at Rocky Mountain Laboratory (NIAIDS, Hamilton, MT), were cultured as described previously (Anantharam et al., 2008; Choi et al., 2007). Cells at ∼75% confluence were treated with varying concentrations of manganese (0, 100, 300, and 500μM) in T25 cell culture flasks and then collected for biochemical analyses. Cells were harvested into phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in either homogenization buffer (20mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 2mM EDTA, 10mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 2mM dithiothreitol, 1mM PMSF, 25 μg/ml aprotinin, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin) or lysis buffer (0.5% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 5mM Tris-HCl, 150mM NaCl, and 5mM EDTA in PBS, pH 7.4). For preparation of soluble and insoluble cell fractions, low-detergent lysis buffer (20mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10mM EGTA, 2mM EDTA, 2mM dithiothreitol, 1mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride, 25 μg/ml aprotinin, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 0.5% Triton X-100) and insoluble lysis buffer (20mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10mM EGTA, 2mM EDTA, 2mM dithiothreitol, 1mM phenylmethysulfonyl fluoride, 25 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 0.5% Triton X-100, and 0.2% SDS) were used.

Cell culture model of infectious prion disease.

Rocky Mountain Laboratory (RML) mouse scrapie–infected Cath. A-differentiated cells (CAD5) and uninfected CAD5 cells were kindly provided by Dr Charles Weissmann of Scripps Institute (Jupiter, FL). Cell culture conditions used in this study were similar to those described previously (Mahal et al., 2007). Briefly, 20,000 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate and allowed to grow for 16 h. Infection was performed by addition of 0.3 ml of 5 × 10−6 RML-infected brain homogenate in Opti-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 90 U/ml penicillin and 90 μg of streptomycin per milliliter. After three 1:8 splits, the well with the highest amount of infected cells was subcloned and reinfected with 10−7 RML-infected brain homogenate. The most positive clone from a 14 split was then expanded and frozen in 50% FBS, 10% DMSO, and 40% Opti-MEM. RML infection was periodically verified by PK-resistant prion protein analysis with Western blot.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting.

After harvest, cells were lysed, homogenized, sonicated, and centrifuged as described previously (Sun et al., 2005). The supernatants were collected from cell lysates, and protein concentrations were determined and used for sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Cytoplasmic and membrane-rich fractions containing equal amounts of protein were loaded in each lane and separated on a 15% SDS-PAGE as described previously (Sun et al., 2005).

For determination of high–molecular weight ubiquitinated proteins, low-detergent soluble and insoluble fractions were separated according to a procedure described previously, with slight modifications (Sun et al., 2005). After exposure to manganese or proteasome inhibitor, MG-132 cells were collected and washed once with ice-cold PBS. The cell pellets were suspended in low-detergent lysis buffer. Lysates were ultracentrifuged at 100,000 × g for 40 min, and the detergent-soluble fraction was obtained by collecting the resulting supernatant. The detergent-insoluble pellets were washed once with lysis buffer and resuspended in insoluble lysis buffer and sonicated for 20 s. Equal amounts of protein were loaded in 8% SDS-PAGE, as determined by the Bradford protein assay.

Proteins were then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and nonspecific binding sites were blocked by treating with 5% nonfat dry milk powder. Membranes were then treated with primary antibody directed against the 3F4-epitope present in the PrPC protein (1:500 dilution), or SAF-32 (1:1000), which was followed by treatment with secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse antibody. For detection of ubiquitinated proteins, the membranes were probed with ubiquitin antibody (1:500) overnight at 4°C, followed by secondary HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody. Secondary antibody-bound proteins were detected using the ECL chemiluminescence kit. To confirm equal protein loading, blots were reprobed with a β-actin antibody at a dilution of 1:5000. Western blot images were captured with a Kodak 2000MM imaging system.

Confocal laser microscopy.

Cells were grown on coverslips precoated with poly-L-lysine and treated with 100μM manganese. Cells were then washed once with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. After fixation, cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated with blocking buffer (5% bovine serum albumin and 5% goat serum in PBS) to block nonspecific sites. For prion primary antibody (3F4) binding, fixed cells were incubated in the same blocking buffer with 0.1% Triton X-100. Fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibody incubation was performed in the blocking buffer. Nucleus staining was performed with 5μM DRAQ5 for 10 min. After final nucleus staining, fixed cells were washed with PBS and mounted onto a slide with Prolong (Invitrogen) antifade reagent and mounting medium. Confocal laser scanning was carried out using a Nikon C1 confocal microscope (Melville, NY).

Quantitative real-time PCR.

Total RNA was extracted by using the Absolutely RNA Miniprep Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. First-strand complementary DNA synthesis was performed with random hexamers as primers using a High Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems, University Park, IL) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Primers used were target gene—mouse PrP forward (FWD) 5′-CACGAGAATGCGAAGGAACA-3′, reverse (REV) 5′-TTAGGAGAGCCAAGCAGA CT-3′—and internal control gene—mouse 18S ribosomal RNA FWD 5′-TCAAGAACGAAAGTCGGAGGTT-3′, REV 5′-GGACATCTAAGGGCATCACAG-3′. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed with a M×3000P real-time PCR (RT-PCR) thermocycle (Stratagene) using the FullVelocity SYBR Green qPCR kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For actinomycin D treatment, cells were treated with actinomycin D (5 μg/ml) for 3, 6, and 9 h and processed as described previously. Amplification was performed in 40 cycles at 95°C for 10 s, and 60°C for 30 s, following initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min. The data were normalized by using the ΔCT method (ΔCT = CT target gene − CT internal control).

Proteasomal peptidase activity assay.

The proteasome enzymatic assay was performed as described previously (Sun et al., 2005). In brief, after the treatment, cells were collected, washed, and lysed in hypotonic lysis buffer (10mM N-2-Hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-Ethanesulfonic Acid (HEPES), 5mM MgCl2, 10mM KCl, 1% sucrose, and 0.1% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonic acid). For determination of chymotrypsin-like activity, the lysates were then incubated with the fluorogenic substrate Suc-LLVY-AMC (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) at 75μM in assay buffer (50mM Tris-HCl, 20mM KCL, 5mM magnesium acetate, and 10mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.6) for 30 min at 37°C. The cleaved fluorescent product was measured at an excitation wavelength of 380 nm and emission wavelength of 460 nm using a fluorescent plate reader (Gemini XS, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The enzymatic activity was normalized to the protein concentration, as determined by Bradford protein assay.

Pulse-chase study and immunoprecipitation.

Approximately 75% confluent cells were rinsed once with PBS and deprived for 1 h in DMEM lacking cysteine and methionine. Cells were labeled for 1 h by adding 300 μCi/ml of [35S]-methionine to the medium. After incubation, cells were rinsed twice with ice-cold PBS and collected using a cell scraper. Lysis buffer was added to the cell pellet that was lysed on ice for 30 min. Samples were then incubated with 3F4 prion antibody overnight on a platform rocker at 4°C. Protein A-Sepharose beads were added and placed on the platform rocker for an additional 2 h at 4°C. Immunoadsorbed proteins were washed twice in ice-cold lysis buffer and analyzed by 15% SDS-PAGE. Gels were exposed to a phosphor film and captured with a Typhoon 8600 Imager (Amersham). Captured images were analyzed with ImageQuant software (Amersham). The amount of total PrP present at each time point following the chase period (1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h) was expressed as percentage of PrP present at 1 h postchase time. Half-life was calculated by fitting to a single exponential decay curve.

Limited proteolysis of prion protein.

The relative resistance of prion protein to PK digestion was determined as previously described, with slight modifications (Priola et al., 1994). Cells were treated with 100μM Mn, while untreated cells were used as the control. After a 24-h incubation period, cells were collected and washed once with PBS. Lysis buffer was added to the pellet and vortexed. Clarified cell lysates were obtained by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 min. PK was added to the cell lysates at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml and incubated at 37°C for selected time points. To stop the digestion, PMSF was added to a final concentration of 4mM, and sample loading buffer was added to the digested lysates prior to analysis by Western blot. For cell-free studies, cells at confluency were collected and lysed in the lysis buffer. Following protein measurements using Bradford’s method, ∼5 mg/ml of cell lysates were separated into manganese-treated and untreated control groups. For manganese treatment, 100μM Mn was added to the cell lysate that was incubated at 37°C for 1 h prior to limited proteolysis.

Mouse brain slice preparation.

Mouse brain slices were obtained from adult C57BL/6 mice. All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Iowa State University and were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.” Animals were anesthetized with isofluorane, and brain was removed and placed in ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; 125mM NaCl, 2.5mM KCl, 26mM NaHCO3, 1.25mM NaH2PO4, 1.2mM MgSO4, 2mM CaCl2, and 15mM dextrose). Coronal slices (400 μm) were generated and placed in ice-cold aCSF. After preparation, the slices were transferred to sterile porous membrane units (Millicell 12 mm CM PTFE 0.4 μm, Millipore, Billerica, MA) and preincubated in incubation media containing 25% Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution, 25% heat-inactivated horse serum, 50% Modified Eagle Medium, 5mM L-glutamine, 6.5 mg/ml D-glucose, 20mM HEPES, and streptomycin/penicillin (5 g/ml and 5000 U/ml, respectively) for 2 h prior to initiation of manganese treatments. Slices were cultured for 1, 3, and 7 days at 37°C in 5% CO2 with or without manganese (300μM). The culture medium was changed every 2 days until the last day of treatment.

Quantification of brain-derived PrP.

Brain homogenates were prepared (10% wt/vol) in lysis buffer containing 150mM NaCl, 10mM Tris-HCl, 10mM EGTA, 2mM EDTA, and 1mM PMSF protease inhibitor cocktail. Protein concentration was measured using the Bradford method, as previously described (Choi et al., 2007). An equal concentration of protein was loaded for each sample, and separated proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane and probed with SAF32 monoclonal antibody. Following primary antibody incubation, blots were washed thoroughly and incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody and visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence. For verification of equal loading of proteins, the blots were stripped and reprobed with β-actin. All images were captured with a Kodak 2000MM imaging system. PrP levels were normalized to β-actin and plotted as percentage of PrP level of untreated sample at day 1.

Measurement of manganese concentration in mouse brain slices.

Brain slices were collected at 1, 3, and 7 days following treatment and weighed prior to analysis with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) to determine the concentrations of Mn, Fe, Cu, and Zn in each sample. The ICP-MS device was a high-resolution double-focusing instrument operated at medium resolution (m/Δm = 4000) in order to resolve the isotopes of interest from any interferences (Choi et al., 2007). The signals from the two most abundant isotopes of Fe, Cu, or Zn were measured, and the average concentration calculated from both isotopes is reported. Manganese is monoisotopic, so its concentration was calculated from the signal from one isotope. Each sample was placed in an acid-washed 5 ml Teflon vial and digested in l% high-purity nitric acid. Following digestion, the samples were diluted to 5 ml with Milli-Q 18.2 Mω deionized water for a final acid concentration of ∼2% nitric acid. The supernatant was analyzed with ICP-MS.

An internal standard method was used for quantification. Gallium was chosen as the internal standard because its m:z ratio is similar to that of the elements of interest, and it has no major spectroscopic interferences. A small spike of Ga standard solution was added to each sample such that the final concentration of Ga was 10 ppb. A 10 ppb multielement standard (Mn, Fe, Cu, Zn, and Ga) was also prepared. The nitric acid blank, the multielement standard, and each of the samples were introduced into the ICP-MS via a 100 μl/min self-aspirating PFA nebulizer (Elemental Scientific, Inc.). Between samples, the nitric acid blank was used to rinse the nebulizer. The results for each sample are calculated using the integrated average background-subtracted peak intensities from 20 consecutive scans. In order to correct for differences in isotopic abundance and elemental sensitivity in the ICP, the multielement standard was used to derive normalization factors for Mn, Fe, Cu, and Zn. The concentration of each element was then calculated for each sample.

Data analysis and statistics.

Data were analyzed with Prism 4.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Bonferroni post hoc multiple comparison testing was used to delineate significance between manganese-treated groups and the control (untreated) samples. Differences with p < 0.05 were considered significant and are indicated with asterisks. For densitometric analysis of limited proteolysis, band intensity was normalized to control bands at 0 min, and one-phase exponential decay was fit to the data.

RESULTS

Manganese Treatment Upregulates Normal Cellular Prion Protein (PrPC) Expression

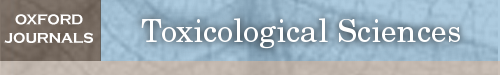

Previously, we showed that the EC50 of manganese was 100μM in mouse PrPC-expressing cells (Choi et al., 2007), and this concentration was used for all experiments. First, we measured cellular prion protein (PrPC) levels in the cytoplasm and membrane following manganese treatment using Western blot. As shown in Figure 1A, manganese-treated cells showed a time-dependent increase in PrPC expression in both cytosolic and membrane fractions up to 24 h. The increase was observed as early as 6 h after manganese exposure. Untreated control cells did not exhibit any significant increase in PrPC levels. Densitometry analysis of prion protein bands (Fig. 1A) shows a time-dependent increase in prion protein levels over a 24-h time period in both cytosolic and membrane fractions (Fig. 1B). Equivalent loading of proteins in each lane was confirmed using β-actin as the internal control. To further characterize the cellular distribution of prion protein levels, the immunocytochemical (ICC) method was employed. Confocal image analysis of immunohistochemically processed samples revealed more accumulation of PrPC in both the plasma membrane and the cytoplasm of manganese-treated cells as compared to untreated cells (Fig. 1C). Manganese-treated cells at 18 h showed significant morphological changes, with stronger immunoreactivity of PrPC in cytosol and membrane and fewer neuronal processes as compared to the control cells. At earlier time points of 6–12 h, no significant morphological changes were noted in Mn-treated cells, but prion protein immunoreactivity was evident in both cytoplasm and plasma membrane (data not shown). Collectively, these results suggest that manganese exposure significantly upregulates prion protein levels in neuronal cells.

FIG. 1.

Manganese-induced cellular prion protein (PrPC) upregulation in mouse neuronal cells. (A) Western blot analysis of PrPC at various time points following manganese treatment. The cells were treated with manganese (100μM) for 0, 6, 12, 18, and 24 h and harvested. Cytosolic fractions and membrane-rich fractions were obtained and analyzed by Western blotting. (B) Densitometry analysis of PrPC bands (17–37 kDa) in (A). *p < 0.05 or **p < 0.01 compared with the control group. (C) ICC expression of PrP in cells with and without manganese treatment. PrPC staining is shown in green and nucleus staining is in blue.

Manganese-Induced PrPC Upregulation is not due to Increased Transcriptional Rate or Impaired Protein Degradation Machinery

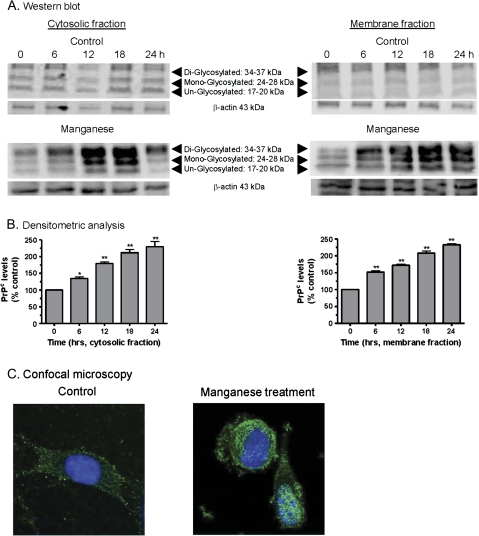

Next, we carried out a series of experiments to determine the cellular mechanisms underlying Mn-induced PrPC upregulation. We sought to examine whether the increase in PrPC level during Mn exposure is due to increase in transcription of PrP messenger RNA (mRNA) or due to impairment in degradation of PrPC protein by the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) or lysozymes. PrP mRNA expression in Mn-treated cells was measured by quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). As shown in Figure 2A, no significant difference in the mRNA levels was observed between manganese-treated and control cells. To further confirm that the increased PrPC levels were not due to differences in the stability of mRNA, cells were treated with actinomycin D and the stability was determined over time by qRT-PCR. The levels of PrP mRNA transcripts in the manganese-treated and control samples were not significantly different (Fig. 2B), suggesting manganese-induced PrPC levels are not due to increased stability of PrPC mRNA.

FIG. 2.

Effect of manganese on mRNA levels, ubiquitin proteasomal system, and lysozyme activity. (A) Comparison of PrP mRNA levels in manganese-treated and control mouse neuronal cells. The cells were treated with 100μM manganese for 24 h, and PrP mRNA levels were determined by quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. (B) Determination of PrP mRNA stability with manganese treatment. The cells were treated with actinomycin D to inhibit transcription of mRNA, and PrP mRNA levels were determined at 3, 6, and 12 h in manganese-treated and control cells. (C) Measurement of proteasomal activity with manganese treatment. Chymotrypsin-like activity was measured at 24 h following manganese treatment. (D) Evaluation of high–molecular weight ubiquitinated protein formation with manganese treatment. The cells were treated with manganese for up to 24 h; ubiquitinated proteins were measured in soluble and insoluble fractions by Western blot at 0, 6, 12, 18, and 24 h. A known proteasome inhibitor MG132 was used as a positive control. (E) Measurement of lysosomal activity with manganese treatment. Lysosomal activity was measured following 100μM manganese treatment at 24 h. Egg white lysozyme was used as a positive control. Experiments were repeated three to four times in each assay.

Since PrPC upregulation was not based on increase in transcripts or mRNA stability, we next examined whether the upregulation is due to impairment of the cellular protein degradation system. Ubiquitin proteasome function was assessed by measuring chymotrypsin-like enzyme activity. Manganese treatment did not alter chymotrypsin-like enzyme activity (Fig. 2C). Because impairment in the UPS has been associated with formation of high–molecular weight ubiquitinated proteins, we also measured ubiquitinated protein levels by Western blot. Manganese treatment did not increase the formation of high–molecular weight ubiquitinated proteins in soluble and insoluble fractions at various time points (Fig. 2D). The proteasome inhibitor MG-132 was used as a positive control, and MG-132 treatment caused significant accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in soluble and insoluble fractions. To further rule out possible involvement of another cellular degradative system during manganese treatment, lysosomal activity was measured. Lysosomal activity assay indicated that there was no significant difference between manganese-treated and control cells (Fig. 2E). Egg white lysozyme was used as a positive control for the lysosomal assay. These results collectively demonstrate that Mn-induced prion protein upregulation is not due to increased transcriptional rate, mRNA stability, or impairment of protein degradative machinery.

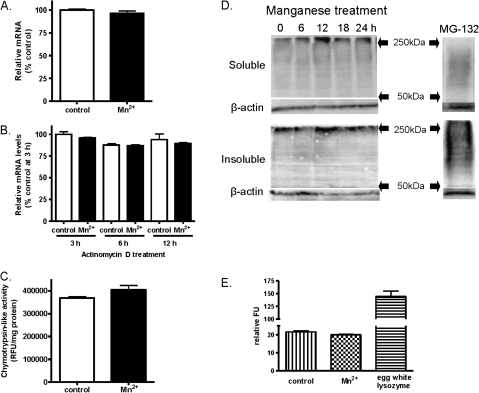

Manganese Delays the Turnover Rate of PrPC

Since neither the transcriptional rate nor the protein degradation was altered, we proceeded to investigate whether manganese altered the cellular metabolism of PrP. We measured the effect of manganese on prion protein turnover rate in a pulse-chase experiment. The cells were labeled with [35S]-methionine and then exposed to 100μM Mn, and the prion protein turnover was chased at various time points for a total of 24 h posttreatment. As shown in Figure 3A, manganese treatment protracted the turnover rate of PrPC as compared to the control group. The densitometric analysis of prion protein turnover in the autoradiogram was quantified at various chase time points (Fig. 3B). Manganese treatment significantly altered the turnover rate of prion protein over a 24-h chase period. The half-life of PrP in control samples was determined to be 13 h, while the half-life of PrP was increased to 21 h in manganese-treated samples. These data indicate that manganese treatment increases the stability of prion protein, resulting in higher accumulation of PrPC in manganese-treated cells relative to controls.

FIG. 3.

Effect of manganese on PrPC turnover rate measured by pulse-chase analysis. (A) Confluent mouse neuronal cells were metabolically labeled with 300 μCi/ml [35S]methionine for 1 h at 37°C. After the pulse, cells were incubated in cell culture medium without [35S]methionine in the presence or absence of 100μM manganese at 37°C for the indicated chase time periods. PrPC was immunoprecipitated with 3F4 antibody and then subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (B) Densitometric evaluation of autoradiogram. PrPC collected 1 h after the radioactive pulse was set as 100% PrPC population. Decreases in protein amounts following the chase periods are expressed as a percentage of total protein plotted as a function of time. The data points were fitted to an exponential curve using nonlinear regression analysis. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM for three replicates.

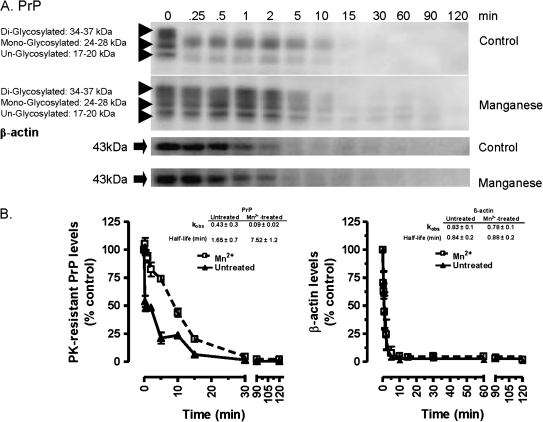

Manganese Treatment Decreases Proteolytic Susceptibility of PrPC

We next determined whether manganese treatment alters the proteolytic rate of prion proteins by performing a limited proteolysis assay with PK. PK-dependent proteolysis of prion protein is traditionally used for determination of the pathogenic form of PrPSc (Brown, 2009). Cell lysates from 100μM manganese-treated cells and control cells were incubated with 20 ug/ml PK and then the proteolytic susceptibility was monitored over time. As shown in Figure 4A, the proteolytic rate of prion protein in manganese-treated cell lysates was slower than in control lysates, indicating that manganese treatment induces a protease-resistant form of prion protein. To confirm the specificity of Mn treatment, we immunoblotted the lysates with β-actin antibody and found no change in β-actin proteolytic susceptibility (Fig. 4A). These results suggest that the altered protease resistance of PrP in manganese-treated cell samples is a result of manganese binding to prion protein, which stabilizes the prion protein inside the cell and confers higher PK resistance. Also shown in Figure 4B are the best-fit parameters of a single-phase exponential of data. The analysis revealed that Kobs for PrPC was significantly reduced in manganese-treated cell lysates, whereas the PrPC half-life was significantly increased in manganese-treated cells as compared to untreated control cells. Half-life for PrPC proteolysis was determined to be 1.65 and 7.5 min for untreated and manganese-treated cells, respectively. However, the half-life for β-actin was unaltered: 0.84 and 0.83 min for untreated and manganese-treated cells, respectively.

FIG. 4.

Manganese decreases PK-dependent PrPC proteolysis. (A) Limited proteolysis of PrPC in presence or absence of manganese. The cells treated with 100μM manganese and lysates were prepared as described in the “Materials and Methods” section. Samples were separated into equal fractions and treated with 1 μg/ml PK at 37°C. PK digestion was inhibited at indicated time periods with addition of 4mM PMSF and processed for Western blotting with 3F4 antibody or β-actin antibody; (B) Densitometric analysis of the PrPC and β-actin bands was quantified and fit to a single-phase exponential decay. Each data point represents mean ± SEM from three individual experiments performed.

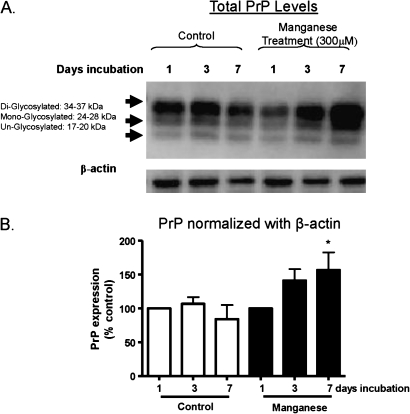

PrP Expression in Mouse Brain Slice Cultures Treated with Manganese

In order to extend our studies to brain tissues, we examined the effect of manganese on prion protein in mouse brain slice culture models. Mouse brain slices were prepared and then exposed to 300μM manganese for 1, 3, and 7 days. Following the treatment, tissues were lysed and equal amounts of protein were used for measurement of prion protein levels by Western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 5A, a time-dependent increase in PrP expression was observed in manganese-treated slices as compared to the control slices. All three isoforms, including di-glycosylated, mono-glycosylated, and unglycosylated isoforms, were increased. However, there was no significant change in the β-actin protein level, which was used as a loading control. Figure 5B shows the densitometric data for the 37 kDa band prion protein levels. These results show that manganese exposure significantly upregulates the level of prion protein in brain tissues, consistent with data obtained in cell culture models.

FIG. 5.

Manganese-induced PrPC upregulation in mouse brain slices. Mouse brain slice cultures were exposed to 300μM manganese for 1, 3, and 7 days, and slices were then homogenized and subjected to Western blot and metal analysis. (A) Representative Western blot analysis of total PrPC levels in mouse brain slices treated with manganese and in untreated slices is shown at top. (B) Below, the representative Western blot image is the quantification of band intensity of PrPC normalized with β-actin levels. Each data point represents experiments performed in triplicate *p < 0.05.

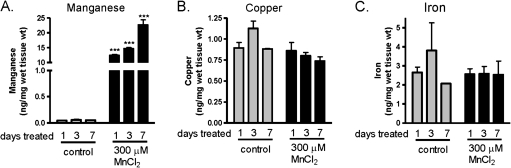

Manganese Levels in Brain Slices

To verify manganese uptake into the mouse brain slice cultures, slices were collected following treatment and processed for metal analysis by ICP-MS. As shown in Figure 6A, a significant increase in manganese content was observed in samples treated with manganese starting at day 1. The manganese uptake was quite evident as early as day 1 of treatment. However, levels of other divalent cations, copper (Fig. 6B), iron (Fig. 6C), and zinc (data not shown), were not significantly altered by manganese treatment and remained unchanged through 7 days of manganese treatment. The ICP-MS data suggest increased intracellular Mn levels during chronic manganese exposure in brain slices.

FIG. 6.

Divalent cation levels in mouse brain slices following manganese treatment. Quantitative analysis of divalent cation levels in mouse brain slice culture treated with 300μM manganese for 1, 3, and 7 days is shown in (A) Manganese, (B) Copper, and (C) Iron. Each data point represents experiments normalized to wet weight of mouse brain slices performed in triplicate ***p < 0.001.

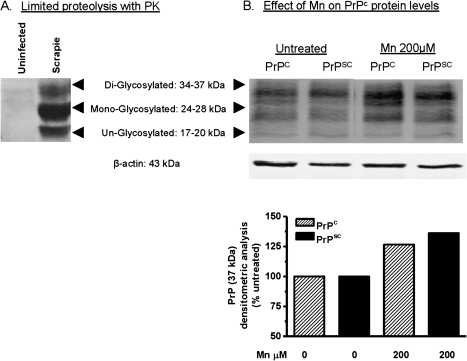

Manganese Induces Upregulation of Prion Protein in a Scrapie-Infected Cell Culture Model of Prion Disease

Next, we examined whether Mn is capable of upregulating PrP levels in the infectious form of prion protein, PrPSc. We used the RML scrapie–infected Cath. A-differentiated (CAD5) mouse neuronal cell line for this study. This cell model of infectious prion disease was obtained from Dr Charles Weissmann, whose laboratory at Scripps Institute, Florida, recently demonstrated that RML-infected CAD5 cells make an excellent cell culture model of infectious prion disease because these cells propagate PrPSc infection through multiple passages without the need for reinfection (Mahal et al., 2007). We first demonstrate the presence of PK-resistant PrPSc prion protein in scrapie-infected CAD5 cells by performing a limited proteolysis assay with PK. Prion proteins were immunoprecipitated with 6H4 antibody from uninfected and scrapie-infected CAD5 cells and then the proteolytic susceptibility was monitored. As shown in Figure 7A, PK-resistant PrPSc protein was present in scrapie-infected CAD5 immunoprecipitates but not in uninfected CAD5 immunoprecipitates. RML scrapie–infected and uninfected CAD5 cells were exposed to 200μM Mn for 12 h. Cells were harvested and subjected to Western blot analysis for PrP protein expression levels. As shown in Figure 7B, manganese induced similar increases in PrP protein levels in both uninfected and RML scrapie-infected CAD5 cells, suggesting that manganese treatment can affect PrP expression even during the progression of prion disease in infected cell culture models.

FIG. 7.

Manganese-induced PrPC upregulation in an infectious cell culture model of prion disease. (A) PK-resistant PrPSc levels in RML-infected CAD5 cells. (B) Western blot analysis of PrPC at 12 h with 200μM manganese treatment in both uninfected and RML-infected CAD5 cells. (C) Densitometry analysis of PrPC bands (17–37 kDa) in (A).

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that manganese exposure upregulates prion protein levels without altering transcription of PrP mRNA or degradation of the protein. The increased protein level is mainly attributed to stabilization of the protein, as determined by increased half-life of PrPC in a pulse-chase experiment. In this study, we show that manganese-induced prion protein upregulation in various models, including neuronal cell cultures, mouse brain slices, and an infectious cell culture model of prion disease, confirming the reproducibility and biological significance of our novel observation. Our study also demonstrates that manganese treatment increases the PrPC resistance to PK-dependent proteolysis similar to that observed for scrapie prion protein (PrPSc). Additionally, results with an infected cell culture model reveal that manganese can increase the upregulation of the infectious form of prion protein, indicating the importance of metals in prion pathogenesis. To our knowledge, this is the first time that upregulation of prion protein independent of transcription contributing to enhanced stabilization and resistance to proteolysis is demonstrated. Thus, our results of manganese-induced stabilization of prion protein suggest that altered metal homeostasis may play an important role in the pathogenesis of prion diseases.

Many physiological and cellular changes occur during prion infections of central nervous system, such as neuronal vacuolization, neuronal loss, gliosis, oxidative impairment, and metal imbalance (Brown, 2009). Some of the most striking changes at the cellular level after prion infection are the loss of antioxidant function and altered metal content, suggesting a role of metals in the pathogenesis of prion diseases (Brown, 2009). In particular, increased manganese in the brains of various prion diseases, including BSE and CJD, were reported (Brown, 2009). We recently showed that cellular prion protein protects against oxidative stress–induced apoptotic cell death (Anantharam et al., 2008). We also demonstrated that manganese binds to prion protein and reduces the manganese transport into cells (Choi et al., 2007). We reported that PrPC expressing cells were more resistant to manganese-induced cytotoxic and apoptotic cell death as compared to PrPC knockout (PrPKO) cells. Also, manganese-induced reactive oxygen species production, caspase-3 and caspase-9 activation, and DNA fragmentation were significantly lower in PrPC cells as compared to PrPKO cells (Choi et al., 2007), demonstrating that endogenous normal prion protein protects against metal-induced oxidative stress and neurotoxicity. Thus, our previous studies suggested that cellular prion protein may act as a metal sink, thereby preventing manganese from entering the cells and exerting its neurotoxic effect at the early stages of metal neurotoxicity.

Manganese has been shown to cross the blood-brain barrier via specific carriers such as transferrin and divalent metal transporter 1 and also by diffusion. The normal concentration of manganese in human adult tissues ranges from 3 to 20μM, and the human blood manganese level is 7.2 μg/l, with a mean brain manganese level of 0.261 μg/g. Mn levels in the putamen, substantia nigra, and neuromelanin are 6.31, 0.34, and 58.5 ng/mg wet weight, respectively. Depending on the level of exposure, blood Mn concentrations can increase from 10- to 200-fold. Environmental exposures to manganese occur mainly by ingestion or inhalation. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency reference limit for ambient manganese concentration is 0.05 μg/m3. Studies have shown that manganese levels range anywhere from 20,000 to 450,000 μg/m3 in certain high exposure environments (Huang et al., 1989). In welding smoke, there might be more than 25,000 μg Mn per cubic meter (Wang et al., 1989). Normally, higher relative concentrations of manganese are required in cell culture studies, and the concentrations used in our studies are consistent with other studies. In our previous dose response study in cell culture models of prion, 117μM Mn was calculated as the EC50 concentration (Choi et al., 2007), and therefore, we used 100μM Mn for PrPC cells. In order to achieve adequate intracellular concentrations of Mn in CAD5 cells and brain slices, we used 100 and 300μM, respectively. The manganese concentrations used in our study are much lower than 0.6–1mM concentration of Mn used in other cell types (Latchoumycandane et al., 2005; Marreilha dos Santos et al., 2008; Milatovic et al., 2009). Higher relative concentrations of test compounds are generally needed to elicit responses in cell cultures due to the acute nature of the treatment period in in vitro studies (hours to days) compared with chronic long-term studies in animal models (days to months). Importantly, the 100–300μM manganese concentrations used in this study approximate the concentrations observed in the striatum of manganese exposed animals. Thus, the concentration of Mn used in the present study is consistent with the literature and relevant to Mn neurotoxicity (Marreilha dos Santos et al., 2008; Moreno et al., 2009).

While investigating the mechanisms of prion protein in metal neurotoxicity, we unexpectedly found that manganese treatment upregulates cellular prion levels. RT-PCR experiments revealed no increase in PrPC mRNA levels. Additionally, studies with the transcriptional inhibitor actinomycin D showed mRNA stability is not altered during manganese treatment, suggesting that neither the transcription nor the mRNA stability of prion contributes to manganese-induced upregulation of PrPC. Then, we examined whether upregulation of prion protein is due to impaired UPS and lysozyme activity, and the results indicated that both UPS and lysozyme protein degradative pathways are similar in manganese-treated and untreated cells. Alternatively, it is possible that manganese-induced increases in PrPC levels could result from decreases in a key protease, calpain. However, studies have shown that calpain and other cytosolic proteases can be activated to increase the degradation of retro-translocated prion protein in the cytosol (Wang et al., 2005) and that calpain-dependent endoproteolytic cleavage of PrPSc modulates scrapie prion propagation (Yadavalli et al., 2004). A recent article by Sorgato and Bertoli (2009) suggests that a relationship between the prion protein and Ca2+ homeostasis exists, and the authors discuss the possibility that Ca2+ may be the factor behind the enigma of the pathophysiology of PrPC (Sorgato and Bertoli, 2009). Since we did not see calpain-cleaved PrPC degraded fragments in Western blots, it is unlikely that calpain played a major role in our study. As described in the following section, we believe that Mn-induced PrPC upregulation may be the result of its binding to PrPC octapeptide repeats.

This led us to examine whether manganese affects prion protein turnover rates in pulse-chase experiments. Manganese significantly altered the turnover rate of prion protein. The half-life of PrP greatly increased to 21 h in manganese-treated cells as compared to 13 h in untreated control cells, suggesting manganese treatment increases the stability of prion protein, which subsequently results in increased levels of prion protein during manganese exposure. We previously demonstrated that upregulation of prion protein does not occur in PrPC cells during H2O2– or ER stress–induced apoptosis (Anantharam et al., 2008), suggesting that the altered prion protein turnover observed in this study probably results from Mn binding, which increases the stability of prion protein.

Although the physiological function of PrPC remains to be elucidated, the metal-binding capacity of the protein is well recognized. The octapeptide repeat region of the protein structure has been established as key for the metal-binding role of PrPC (Choi et al., 2006, 2007; Hooper et al., 2008; Todorova-Balvay et al., 2005). Numerous studies have shown that PrPC has strong binding affinities to various divalent cations, including copper, manganese, and zinc (Choi et al., 2006, 2007; Hooper et al., 2008; Todorova-Balvay et al., 2005). One of the most significant differences seen with the absence of PrPC in both mouse brain and cell cultures is the reduced basal content of crucial divalent cations, such as copper and manganese, strongly suggesting that PrPC modulates metal homeostasis (Brown, 2009; Choi et al., 2007). Recent studies using recombinant PrP have shown that manganese can irreversibly replace copper bound to PrP, despite an apparent lower affinity, and this replacement causes conformational changes within the protein (Brazier et al., 2008; Brown et al., 2000). Recombinant PrP refolded in the presence of manganese was originally thought to bind up to four molecules of manganese at the octapeptide repeat domain, similar to copper (Brown, 2009). However, isothermal titration calorimetric studies demonstrated that PrP binds one molecule of manganese at each of two sites, with dissociation constants of 63 and 200μM (Brazier et al., 2008). In comparison, divalent metal transporter 1, a known transporter of manganese across the plasma membrane, was shown in kinetic studies of manganese uptake to transport manganese in millimolar concentrations (Garrick et al., 2006). The biological consequence of copper replacement by manganese on the prion protein is yet to be established. Studies using circular dichroism and Raman optical activity indicate that upon PrP binding to manganese, the secondary structure becomes more organized, gaining greater α-helix and β-sheet content than copper-bound PrP (Brown, 2009). This suggests that manganese may promote misfolding and aggregation of prion protein that is a hallmark of prion diseases. Future investigation in a relevant animal model of chronic manganese neurotoxicity will help to address the role of manganese in prion protein misfolding and aggregation.

Our results show that manganese exposure increases PK resistance to prion protein in neuronal cells. Similarly, manganese exposure resulted in higher levels of PrP both in uninfected and in RML scrapie-infected CAD5 cells, suggesting that manganese treatment can affect PrP stability and expression even during the progression of prion disease. Brown et al. have previously shown that primary rat astrocytes treated with manganese exhibit reduced proteolytic susceptibility, which they attributed to production of protease-resistant forms of PrP (Brown, 2009). Bocharova et al. (2005), however, have shown that manganese has little if any direct effect on recombinant PrP protease resistance or secondary structure. Interestingly, a study with yeast prion proteins also showed that yeast cells treated with manganese-supplemented media generated PK-resistant forms of PrP (Treiber et al., 2006). It appears that the interaction of metals with recombinant PrP protein in a cell-free system may be different from in vivo conditions. The biological relevance of manganese-induced prion protein upregulation is an important point to discuss. Studies from knockout mice as well as cattle have demonstrated that PrPC is an absolute requirement for propagation of prion disease (Fischer et al., 1996; Richt et al., 2007). Conversely, multiple copies of the PrP gene or PrP overexpressing transgenic mice show a shortened incubation time from infection to disease onset, resulting in exacerbation of the disease (Fischer et al., 1996). Since the normal cellular form of prion protein PrPC serves as a seed for conversion of the diseased form of prion protein, PrPSc, manganese-induced upregulation of PrPC could provide more substrate for spontaneous conversion of PrPC into PrPSc. The structural changes within the protein induced by manganese binding to the octapeptide repeats may explain the altered PK resistance and increased stability observed in this study. Whether manganese exposure alone can cause prion pathology remains to be investigated. However, the presence of higher levels of PK-resistant nonpathogenic prion protein can serve as a seed for PrPC conversion to pathogenic PrPSc, resulting in the acceleration of the prion disease progression. Together, this study points to the possibility of intracellular manganese impacting the availability of the PrPC substrate for conversion to PrPSc and thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of prion diseases.

The metal-induced prion upregulation may have some implications not only for prion diseases but also for other neurodegenerative diseases. Recent studies suggest that prion-like pathogenic mechanisms may play a role in Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and Huntington diseases (Miller, 2009; Olanow and Prusiner, 2009). Although other neurodegenerative diseases are not contagious like true prion diseases, the propagation of α-synuclein or amlyolid aggregations closely resembles prion-like mechanisms, in which normal proteins self-aggregate and the misfolded protein can be transmitted to unaffected neurons. Recently, α-synuclein has been shown to be transported via endocytosis from affected neurons to neighboring neurons and to engrafted neuronal precursor cells in a transgenic model, resulting in the formation of Lewy body–like Parkinson's disease (PD) pathology and apoptosis (Miller, 2009; Olanow and Prusiner, 2009). Recently, two independent studies revealed that the Lewy pathology appears to spread in grafted neurons in PD patient brains via prion-like propagation from the host tissues to tissue grafts (Kordower et al., 2008; Li et al., 2008). Interestingly, a recent study shows the polymorphism in prion octarepeats in Parkinsonism (Wang et al., 2009). Thus, our findings may provide further mechanistic insights into the pivotal role of metals in the pathological progression of prion disease and other neurodegenerative diseases.

In summary, our study indicates that manganese is an important factor that could interact with PrPC to stabilize the protein, leading to increased PrPC levels in neuronal cells. This in turn suggests that investigation of manganese interaction with PrPC could yield valuable insights into the functional role of PrPC in metal neurotoxicity, as well as the role of the metal in the pathogenesis of prion disease and other related proteinopathies, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Future studies in animal models will elucidate the interaction of metals with prion protein and its role in disease processes.

FUNDING

National Institutes of Health (NIH) (W81XWH-05-1-0239); U.S. Department of Defense; U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command through Vanderbilt University. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, United States Department of Defense, U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, or Vanderbilt University. NIH grants ES 10586, NS 38644 (A.G.K.); National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases-NIH PO1 AI 77774-01 (J.A.R.).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their appreciation for the mouse prion neural cell line obtained from Dr Sue Priola, Rocky Mountain NIH Lab, Hamilton, MT; and the infectious cell model of prion disease CAD5 cells kindly provided by Dr Charles Weissmann of Scripps Institute, Jupiter, FL. We also thank Dr Robert Houk, Ames Laboratory, and Chemistry Department, Iowa State University, for analyzing metal content by ICP-MS. The authors acknowledge Ms Mary Ann deVries for assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. W. Eugene and Linda Lloyd Endowed Professorship to A.G.K. also is acknowledged.

References

- Aguzzi A, Heikenwalder M. Pathogenesis of prion diseases: current status and future outlook. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006;4:765–775. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anantharam V, Kanthasamy A, Choi CJ, Martin DP, Latchoumycandane C, Richt JA, Kanthasamy AG. Opposing roles of prion protein in oxidative stress- and ER stress-induced apoptotic signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008;45:1530–1541. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocharova OV, Breydo L, Salnikov VV, Baskakov IV. Copper(II) inhibits in vitro conversion of prion protein into amyloid fibrils. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6776–6787. doi: 10.1021/bi050251q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazier MW, Davies P, Player E, Marken F, Viles JH, Brown DR. Manganese binding to the prion protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:12831–12839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709820200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DR. Brain proteins that mind metals: a neurodegenerative perspective. Dalton Trans. 2009;21:4069–4076. doi: 10.1039/b822135a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DR, Hafiz F, Glasssmith LL, Wong BS, Jones IM, Clive C, Haswell SJ. Consequences of manganese replacement of copper for prion protein function and proteinase resistance. EMBO J. 2000;19:1180–1186. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatigny MA, Prusiner SB. Biohazards of investigations on the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1980;2:713–724. doi: 10.1093/clinids/2.5.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarini LB, Freitas AR, Zanata SM, Brentani RR, Martins VR, Linden R. Cellular prion protein transduces neuroprotective signals. EMBO J. 2002;21:3317–3326. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi CJ, Anantharam V, Saetveit NJ, Houk RS, Kanthasamy A, Kanthasamy AG. Normal cellular prion protein protects against manganese-induced oxidative stress and apoptotic cell death. Toxicol. Sci. 2007;98:495–509. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi CJ, Kanthasamy A, Anantharam V, Kanthasamy AG. Interaction of metals with prion protein: possible role of divalent cations in the pathogenesis of prion diseases. Neurotoxicology. 2006;27:777–787. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collinge J. Molecular neurology of prion disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 2005;76:906–919. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.048660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collinge J, Palmer MS. Prion diseases. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1992;2:448–454. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M, Rulicke T, Raeber A, Sailer A, Moser M, Oesch B, Brandner S, Aguzzi A, Weissmann C. Prion protein (PrP) with amino-proximal deletions restoring susceptibility of PrP knockout mice to scrapie. EMBO J. 1996;15:1255–1264. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrick MD, Singleton ST, Vargas F, Kuo HC, Zhao L, Knopfel M, Davidson T, Costa M, Paradkar P, Roth JA, et al. DMT1: Which metals does it transport? Biol. Res. 2006;39:79–85. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602006000100009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper NM, Taylor DR, Watt NT. Mechanism of the metal-mediated endocytosis of the prion protein. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2008;36:1272–1276. doi: 10.1042/BST0361272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornshaw MP, McDermott JR, Candy JM. Copper binding to the N-terminal tandem repeat regions of mammalian and avian prion protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;207:621–629. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CC, Chu NS, Lu CS, Wang JD, Tsai JL, Tzeng JL, Wolters EC, Calne DB. Chronic manganese intoxication. Arch. Neurol. 1989;46:1104–1106. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520460090018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RT. Prion diseases. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:635–642. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordower JH, Chu Y, Hauser RA, Freeman TB, Olanow CW. Lewy body-like pathology in long-term embryonic nigral transplants in Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Med. 2008;14:504–506. doi: 10.1038/nm1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latchoumycandane C, Anantharam V, Kitazawa M, Yang Y, Kanthasamy A, Kanthasamy AG. Protein kinase Cdelta is a key downstream mediator of manganese-induced apoptosis in dopaminergic neuronal cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005;313:46–55. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.078469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JY, Englund E, Holton JL, Soulet D, Hagell P, Lees AJ, Lashley T, Quinn NP, Rehncrona S, Bjorklund A, et al. Lewy bodies in grafted neurons in subjects with Parkinson’s disease suggest host-to-graft disease propagation. Nat. Med. 2008;14:501–503. doi: 10.1038/nm1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Lindquist S. Conversion of PrP to a self-perpetuating PrPSc-like conformation in the cytosol. Science. 2002;298:1785–1788. doi: 10.1126/science.1073619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahal SP, Baker CA, Demczyk CA, Smith EW, Julius C, Weissmann C. Prion strain discrimination in cell culture: the cell panel assay. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:20908–20913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710054104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marreilha dos Santos AP, Santos D, Au C, Milatovic D, Aschner M, Batoreu MC. Antioxidants prevent the cytotoxicity of manganese in RBE4 cells. Brain Res. 2008;1236:200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milatovic D, Zaja-Milatovic S, Gupta RC, Yu Y, Aschner M. Oxidative damage and neurodegeneration in manganese-induced neurotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2009;240:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G. Neurodegeneration. Acting like a prion isn’t always bad. Science. 2009;326:1338. doi: 10.1126/science.326.5958.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RA, Herzog C, Errett J, Kocisko DA, Arnold KM, Hayes SF, Priola SA. Octapeptide repeat insertions increase the rate of protease-resistant prion protein formation. Protein Sci. 2006;15:609–619. doi: 10.1110/ps.051822606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno JA, Yeomans EC, Streifel KM, Brattin BL, Taylor RJ, Tjalkens RB. Age-dependent susceptibility to manganese-induced neurological dysfunction. Toxicol. Sci. 2009;112:394–404. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olanow CW, Prusiner SB. Is Parkinson’s disease a prion disorder? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:12571–12572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906759106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer MS, Collinge J. Human prion diseases. Curr. Opin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 1992;5:895–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priola SA, Caughey B, Raymond GJ, Chesebro B. Prion protein and the scrapie agent: in vitro studies in infected neuroblastoma cells. Infect. Agents Dis. 1994;3:54–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner SB, Kingsbury DT. Prions–infectious pathogens causing the spongiform encephalopathies. CRC Crit. Rev. Clin. Neurobiol. 1985;1:181–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richt JA, Kasinathan P, Hamir AN, Castilla J, Sathiyaseelan T, Vargas F, Sathiyaseelan J, Wu H, Matsushita H, Koster J, et al. Production of cattle lacking prion protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:132–138. doi: 10.1038/nbt1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Kong Q, Luo X, Petersen RB, Meyerson H, Singh N. Prion protein (PrP) knock-out mice show altered iron metabolism: a functional role for PrP in iron uptake and transport. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorgato MC, Bertoli A. From cell protection to death: may Ca2+ signals explain the chameleonic attributes of the mammalian prion protein? Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;379:171–174. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F, Anantharam V, Latchoumycandane C, Kanthasamy A, Kanthasamy AG. Dieldrin induces ubiquitin-proteasome dysfunction in alpha-synuclein overexpressing dopaminergic neuronal cells and enhances susceptibility to apoptotic cell death. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005;315:69–79. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.084632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorova-Balvay D, Simon S, Creminon C, Grassi J, Srikrishnan T, Vijayalakshmi MA. Copper binding to prion octarepeat peptides, a combined metal chelate affinity and immunochemical approaches. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2005;818:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treiber C, Simons A, Multhaup G. Effect of copper and manganese on the de novo generation of protease-resistant prion protein in yeast cells. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6674–6680. doi: 10.1021/bi060244h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JD, Huang CC, Hwang YH, Chiang JR, Lin JM, Chen JS. Manganese induced parkinsonism: an outbreak due to an unrepaired ventilation control system in a ferromanganese smelter. Br. J. Ind. Med. 1989;46:856–859. doi: 10.1136/oem.46.12.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang V, Chuang TC, Soong BW, Shan DE, Kao MC. Octarepeat changes of prion protein in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2009;15:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wang F, Sy MS, Ma J. Calpain and other cytosolic proteases can contribute to the degradation of retro-translocated prion protein in the cytosol. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:317–325. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410649200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadavalli R, Guttmann RP, Seward T, Centers AP, Williamson RA, Telling GC. Calpain-dependent endoproteolytic cleavage of PrPSc modulates scrapie prion propagation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:21948–21956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400793200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]