Abstract

Soot particles produced by incomplete combustion processes are one of the major components of urban air pollution. Chemistry at their surfaces lead to the heterogeneous conversion of several key trace gases; for example NO2 interacts with soot and is converted into HONO, which rapidly photodissociates to form OH in the troposphere. In the dark, soot surfaces are rapidly deactivated under atmospheric conditions, leading to the current understanding that soot chemistry affects tropospheric chemical composition only in a minor way. We demonstrate here that the conversion of NO2 to HONO on soot particles is drastically enhanced in the presence of artificial solar radiation, and leads to persistent reactivity over long periods. Soot photochemistry may therefore be a key player in urban air pollution.

Keywords: HONO, nitrogen oxides, photochemistry, aerosol, heterogeneous chemistry

Soot particles formed by incomplete combustion of fossil fuels and biomass comprise a significant portion of the total aerosol mass. The current global emission of black carbon, which is the main component of soot, has been estimated to be between 3 and 8 TgC yr-1 (1). Soot particles affect radiative forcing, showing both direct and indirect effects, with an overall contribution to global warming estimated to be second after that due to CO2 (2). Also, they comprise a health risk due to the presence of bound polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) (3, 4), compounds known for their carcinogenic and mutagenic potency to humans (5).

Soot particles exhibit a large specific surface area, ∼100 m2 g-1, which suggests a potential for heterogeneous interactions with atmospheric trace gases. Consequently, there have been many attempts to evaluate the importance of chemical transformations of atmospheric constituents on soot particle surfaces, especially those involving O3 and NOx (6). Other work has focused on the heterogeneous reactions of various atmospheric oxidants with PAHs (7–10). PAHs degradation on soot particles in the presence of radiation has also been studied (7, 11–13). The general conclusion from all previous investigations is that the impact of soot on atmospheric chemistry is likely to be negligible (14–17) because soot surfaces rapidly deactivate under atmospheric conditions via consumption of the reactive species responsible for uptake (18–20). The earlier works concentrated on studying heterogeneous interactions with soot under dark conditions. Recently, Brigante et al. (21) demonstrated a strong enhancing effect of actinic radiation on the kinetics of the heterogeneous reaction between NO2 and solid pyrene films. As PAHs such as pyrene are ubiquitous on soot, this suggested the following question: Does actinic radiation also promote heterogeneous reactions which change the atmospheric relevance of soot? In particular, could light enhance the uptake of tropospheric oxidants on soot particles? The aim of the present work was to address this question by evaluating the effect of light on the reaction of NO2 with various soot samples.

Results and Discussion

Nitrogen dioxide was chosen as the reactive gas because it is an important atmospheric trace gas, which is present at high concentrations along with soot in polluted areas. Its chemistry on soot surfaces in the dark has previously been investigated (14–20, 22–29) to assess its role in nighttime formation of HONO, an important precursor of OH radicals in the troposphere. These studies showed that, after an initial NO2 loss, the soot surface becomes deactivated, leading to no further uptake. Therefore, indicating a negligible overall importance of this process to the NOx chemistry. To assess the potential for photochemical enhancement of this reaction, we performed NO2 uptake experiments using a horizontal coated-wall flow tube reactor, surrounded by six fluorescent lamps (Philips CLEO 20 W), having a continuous emission in the 300–420 nanometers (nm) range and a total irradiance of 1.48 × 1015 photons cm-2 s-1. Trace amounts of NO2 were introduced into the flow tube diluted in 1 atm of synthetic air.

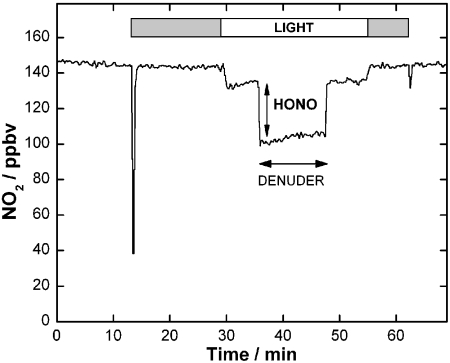

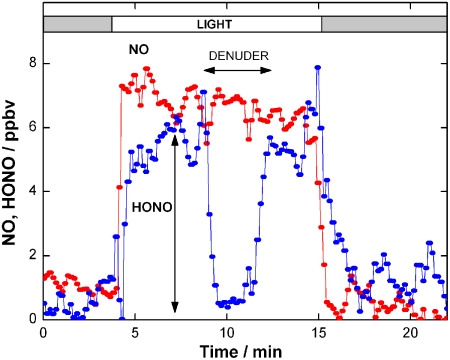

Fig. 1 illustrates the results of one such experiment, using soot formed under fuel-rich conditions exposed to 145 parts per billion by volume (ppbv) of NO2. The initial “spike” shows the uptake of NO2 under dark conditions; in agreement with the previous work, the soot becomes rapidly deactivated, reducing the uptake to zero over a time of approximately 1–2 min. Upon exposure to light, there is a clear time-independent loss of NO2 on the soot surface, persisting over 30 min in this instance. The presence of significant HONO is verified by passing the effluent flow through a carbonate denuder which traps acidic species before detection. This procedure is needed since HONO is detected by the chemiluminescence analyzer as NO2 (SI Methods). The HONO concentration is then obtained as the difference in the NO2 signal without and with the carbonate denuder in the sampling line.

Fig. 1.

NO2 uptake in the dark and under irradiation for soot (fuel-rich conditions). The HONO concentration is obtained as the difference in the detector signal without and with the carbonate denuder in the sampling line. The gray bars indicate exposure in the dark.

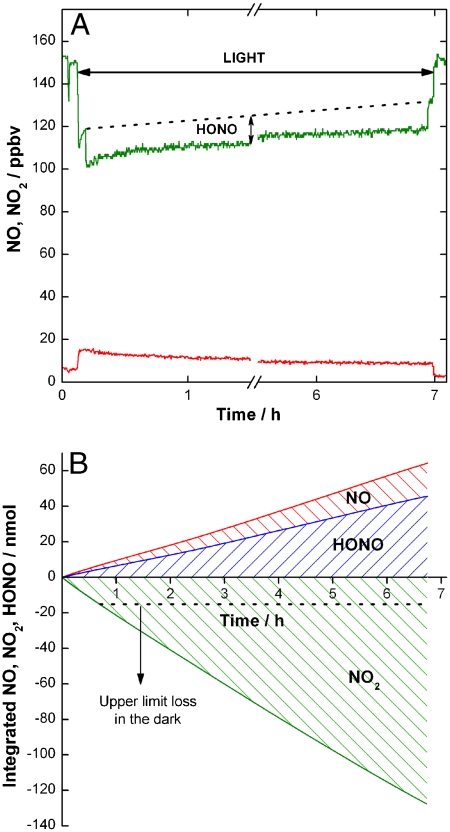

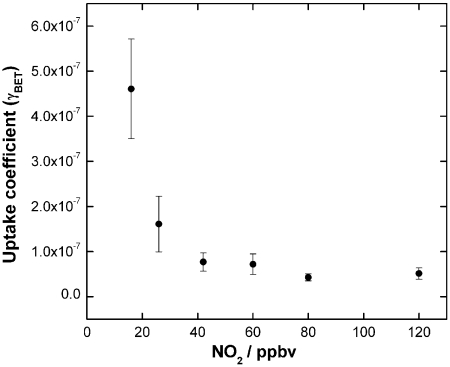

Fig. 2A shows the result of a similar experiment using soot formed under fuel-rich conditions exposed to 150 ppbv of NO2 for a longer period of time. It is clear from the figure that, upon exposure to the light, NO2 loss remains constant over many hours. Coupled with this NO2 uptake is the observation of HONO and NO release to the gas phase for as long as NO2 is taken up by the soot surface. The NO observed in all experiments is likely due to decomposition of HONO on the soot surface as suggested in previous studies (16, 28). Furthermore, no photodissociation of NO2 was observed under irradiation, in contrast to the conditions of the experiments reported by Chughtai et al. (30) on hexane soot, where the effects of light were mediated by NO2 photolysis. Fig. 2B displays the time-integrated loss of NO2 and formation of products under dark and light conditions. Whereas the rapid passivation of the soot surface in the dark leads to a rather insignificant time-integrated NO2 loss, under illumination both NO2 uptake and product formation persisted for almost 7 h, with only 25% NO2 reduction after 7 h. In terms of exposure, the conditions above could be translated into a constant reactivity towards 15 ppbv of NO2 for almost 70 h. Given the inverse dependence of the uptake coefficient (defined as the fraction of collisions with the soot surface which lead to NO2 loss from the gas phase) on the NO2 concentration, shown in Fig. 3, this extrapolation represents a lower limit only. In contrast with previous conclusions, soot may remain chemically active for several days under atmospherically relevant conditions, with a constant production of NO and HONO.

Fig. 2.

(A) Soot produced with a rich flame exposed to 150 ppbv of NO2 under irradiation for almost 7 hrs. The Red Line corresponds to NO and the Green Line to NO2. (B) Time-integrated NO, NO2 and HONO concentrations. The Black Dotted Line indicates the upper limit for NO2 loss in the dark.

Fig. 3.

Uptake coefficients for the heterogeneous reaction between soot (stoichiometric flame) and NO2 under irradiation as a function of the initial NO2 gas concentration. Error bars are derived from the uncertainties associated to the calculation of the uptake coefficients.

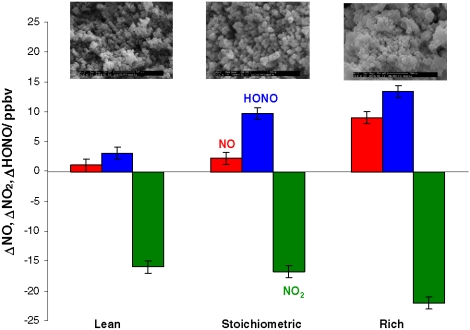

We note that the same qualitative behavior was also observed for soot samples generated from stoichiometric flames. However, the combustion conditions used for soot generation significantly modified the NO and HONO production yields (27, 28). As shown in Fig. 4, soot samples produced with the highest content of oxygen (lean flame) were slightly less reactive towards NO2 than soot samples generated with lower contents of oxygen (stoichiometric and rich flames). The HONO yield was 18% for the former condition, and increased up to 60% for the other burning conditions when the soot was exposed to 40 ppbv of NO2. Again, it must be stressed that in all cases HONO production was only slightly decreasing with time over many hours, in contrast to the chemistry occurring in the dark.

Fig. 4.

NO2 loss, NO and HONO formation on propane soot samples exposed to 40 ppbv of NO2 and generated with a lean, a stoichiometric and a rich flame. SEM images are shown in the upper panels of the figure. Error bars indicate the standard deviation from independent measurements.

Scanning and transmission electron microscopy (SEM, TEM) were used to characterize the soot samples obtained under different combustion conditions. Examples of these are presented in the upper panels of Fig. 4 and in Fig. S1. The nanoparticles constituting soot commonly aggregate into clusters having irregular morphologies and varied sizes (31). The morphology of the particles obtained was similar to the atmospheric soot aerosol described by Alexander et al. (32). As illustrated in Fig. 4 and Fig. S1, the fuel/air ratio, which is a key parameter in combustion technology, strongly influenced the morphology and the microstructure of the soot particles. The fuel/air ratio has previously been suggested to strongly influence the heterogeneous reactivity of soot towards NO2 (23, 27, 28).

The effect of the soot mass was evaluated on the NO2 uptake on soot samples produced with a stoichiometric flame (Fig. S2). The “geometric” uptake coefficient, i.e., the rate of uptake normalized to the geometric substrate surface area, increased linearly with the mass of the soot sample. A similar dependence was reported for different types of soot (19, 33). This behavior suggests that reaction of NO2 takes place at the internal surfaces of the soot sample, after diffusion of the gas through the film. A mass-independent uptake (Fig. 3) was derived using the BET (Brunauer, Emmett, Teller) surface areas, which were 122 ± 1 m2 g-1 and 137.2 ± 0.5 m2 g-1 for samples produced with a lean and a stoichiometric flame, respectively. The latter is similar to the value used by Al-Abadleh and Grassian to correct the geometric uptake coefficient on propane soot reported by Longfellow et al. (26, 33). Daly and Horn (34) reported a BET surface area of 97 ± 22 m2 g-1 for a fresh diesel soot sample.

The HONO yield for soot samples obtained under stoichiometric conditions was found to be 60%, and was invariant to the NO2 concentration between 16–60 ppbv; it decreased to 50% for higher concentrations (Table 1), in contrast to the results on hexane soot obtained in the dark by Aubin and Abbatt (14), who found near unit efficiency for HONO production. The HONO + NO yields were lower than 100% for almost all the concentration range. This suggests that under irradiation the heterogeneous reaction between soot and NO2 may form nonvolatile nitro compounds (15) giving rise to the lower product yields observed. To test this idea, a second set of experiments was performed in which soot samples that had previously been exposed to NO2 under illumination were then exposed to a constant flow of synthetic air in the dark in order to promote NO2 desorption from the surface. Once no further traces of NO and NO2 were observed, the lamps were turned on and emission of HONO and NO from the surface was observed. Fig. 5 shows the appearance of these species upon irradiation of the NO2-treated soot surface.

Table 1.

Uptake coefficients, HONO and NO yields derived from the NO2-soot (stoichiometric flame) reaction under irradiation for different initial NO2 gas concentrations. Errors are 1σ precision

| [NO2]0 ppbv | γBET | HONO yield, % | NO yield, % |

| 16 | (5 ± 1) × 10-7 | 61 ± 4 | 39 ± 5 |

| 26 | (1.6 ± 0.6) × 10-7 | 60 ± 5 | 19 ± 1 |

| 42 | (8 ± 2) × 10-8 | 58 ± 3 | 13 ± 1 |

| 60 | (7 ± 2) × 10-8 | 59 ± 3 | 24 ± 3 |

| 80 | (4.3 ± 0.7) × 10-8 | 49 ± 1 | 11 ± 2 |

| 120 | (5 ± 1) × 10-8 | 48 ± 2 | 13 ± 2 |

Fig. 5.

Effect of light on soot particles (rich flame), which had previously been exposed to 40 ppbv of NO2 and light. In Red is shown the NO signal and in Blue the NO2 signal, which was proved to be HONO when the carbonate denuder was switched into the sample line. Gray bars indicate dark conditions.

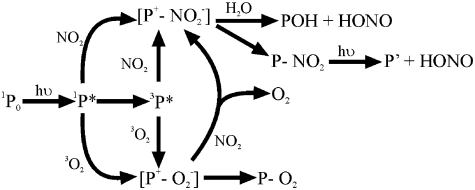

On the basis of the experimental results, a possible pathway is shown in Fig. 6. The electronically activated species (P∗), as PAHs, aromatic structures with carbonyl and carboxyl functional groups (3, 4, 15, 35) can undergo electron transfer followed by hydrolysis and/or nitro compounds formation, both pathways leading to HONO release (21, 22, 36). In addition, photoexcited PAHs species can react with O2 (37), via triplet ( ) and singlet (

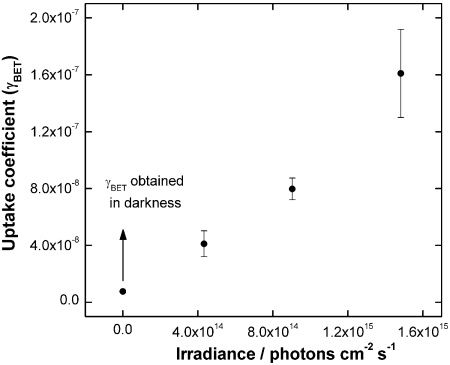

) and singlet ( ) excited states, the latter if the concentration of the reactant is sufficiently high (37, 38). Besides, singlet oxygen formation can not be excluded (39). Nevertheless, reduction of O2 content from 20% to traces did not change either the NO2 uptake or the NO and HONO yields. Following the mechanism illustrated in Fig. 6, the number of reactive sites at the surface is proportional to the number of photoactivated species (P∗), and the latter is proportional to the number of photons. This is demonstrated by the linear dependence of the uptake coefficient on the irradiance (Fig. 7).

) excited states, the latter if the concentration of the reactant is sufficiently high (37, 38). Besides, singlet oxygen formation can not be excluded (39). Nevertheless, reduction of O2 content from 20% to traces did not change either the NO2 uptake or the NO and HONO yields. Following the mechanism illustrated in Fig. 6, the number of reactive sites at the surface is proportional to the number of photoactivated species (P∗), and the latter is proportional to the number of photons. This is demonstrated by the linear dependence of the uptake coefficient on the irradiance (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Proposed reaction mechanism for HONO formation.

Fig. 7.

Effect of irradiation intensity on the uptake coefficient for the heterogeneous reaction of NO2 and soot produced with a stoichiometric flame when exposed towards 25 ppbv of NO2. An NO2 uptake of (2.0 ± 0.6) × 10-6 would be expected if these results are extrapolated to the solar irradiance (in the 300–420 nm range). The arrow indicates the point at zero irradiance which shows the result under dark conditions.

Conclusions

Soot photochemistry first leads to persistent reactivity of soot particles towards NO2 gas traces to produce HONO, NO, and nitrogen containing organic compounds, which can then be photolyzed and release NO and HONO in a NOx-free atmosphere. These observations suggest that soot transported away from a polluted urban environment might provide a local photochemical source of NO and HONO. These results confirm the potentially important contribution of the NO2/soot reaction to the production of HONO because soot deactivation (18) does not occur under irradiation. If the results reported above are extrapolated to the solar irradiance (in the 300–420 nm range) using the dependence shown in Fig. 7, a HONO production rate of 40 ± 10 pptv h-1 (parts per trillion by volume per hour) would be expected for aerosol soot loading of 30 μg m-3 (40). These calculations are based on the data from a soot sample generated under stoichiometric combustion conditions (i.e., those most similar to real Diesel particles) and exposed to 25 ppbv of NO2 under irradiation. Similarly, an estimation of the HONO production rate from soot deposited on urban surfaces would give 25 pptv h-1 if only 1% of a street-canyon surface (41) with 10 m street width and 20 m building height is covered by soot. Taking into account these approximations, the HONO source strengths calculated here represent a lower limit value for an urban environment. Additionally, only the interaction between soot and the UV-a radiation has been investigated so far while the effect of visible light has not been quantified yet. Therefore, heterogeneous soot photochemistry may contribute to the daytime HONO concentration (42, 43). Moreover, recent field measurements indicating a good correlation between J values and an “unknown” HONO source (44) are supportive of the present study.

This process may have implications on the HOx budget in urban areas, due to HONO photolysis (45), but also on health effects, due to persistent soot reactivity under irradiation with potential formation of nitrogen-containing compounds as nitro-PAHs known for their high toxicity (46).

The results presented here challenge the current view about the negligible importance of soot chemistry with respect to the tropospheric composition due to its rapid surface deactivation in the dark. We have demonstrated that light prevents any surface deactivation over time scales comparable to the life time of soot in the atmosphere, thus underlining the need of more studies on soot photochemistry.

Materials and Methods

Soot Samples.

Soot particles were produced by means of a miniCAST (Combustion Aerosol Standard) soot generator using propane as fuel. High purity propane (99.9995%) was used as fuel, synthetic air as oxidant, and N2 (99.9995%) for quenching. The fuel flow was kept fix to 0.06 L min-1 and three variable oxidation air flows were used (1.32 L min-1, 1.50 L min-1 and 1.55 L min-1) to produce soot particles with a rich, a stoichiomentric, and a lean flame, respectively. Soot samples were collected at the exit of the soot generator on the inside walls of a pyrex tube (20 cm length, 1.1 cm i.d.). Different soot masses (0.2–3.2 mg) were tested. All the studies were carried out on fresh samples. Samples were either analyzed immediately after soot collection or stored and sealed under dark conditions. Specific surface areas were measured for the soot samples produced with a lean and a stoichiometric flame before exposure to NO2 using the BET method of N2 adsorption at 77 K using a TRISTAR 3000 apparatus. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy measurements were made with a Jeol JEM 2010 electron microscope (point-to-point resolution of 0.19 nm and acceleration tension of 200 kV). Dry samples were suspended in ethanol. One drop of the suspension was deposited onto a carbon film supported on a copper grid, and the ethanol evaporated quickly at room temperature. SEM analysis of fresh soot samples required sputter coating of the samples with gold prior to analysis. An FEI XL30, ESEM-FEG microscope with secondary electron detection was used with a beam voltage of 10 kV.

Flow Reactor.

The uptake experiments were conducted in a horizontal cylindrical coated-wall flow tube reactor made of pyrex which has been described elsewhere (21) (see SI Methods). The pyrex tube containing the soot sample was placed in the reactor, which was surrounded by six fluorescent lamps (Philips CLEO 20 W), having a continuous emission in the 300–420 nm range. The irradiance of the six lamps used in the experiments, the solar irradiance, and the soot absorbance spectrum for the rich flame condition are shown in Fig. S3. NO2 was introduced into the flow tube by means of a movable injector with 0.3 cm radius. Synthetic air was used as carrier gas, and the total flow rate introduced in the flow-tube reactor was 200 standard cubic centimeters per minute, ensuring a laminar regime. Gas phase NO2 concentrations ranged from 16 to 150 ppbv (4–37 × 1011 molec × cm-3). The experiments were conducted at 298 ± 1 K by circulating temperature-controlled water through the outer jacket of the flow tube reactor. The experiments were performed under atmospheric pressure and 30% of relative humidity. The temperature of the gas streams and the humidity were measured by using an SP UFT75 sensor (Partners BV). All gases were taken directly from cylinders without further purification prior to use. High purity synthetic air (99.999%), and NO2 (1 part per million by volume in N2; 99.0%) were purchased from Air Liquide. The gas flows were monitored before entering the reactor by mass flow controllers (Brooks).

The NO2 concentration was measured at the exit of the flow tube reactor with a THERMO 42 C chemiluminescence analyzer (see SI Methods) as a function of the injector position along the tube. This position determined the exposure time of the soot surface towards the gas. Control experiments were carried out to check the reproducibility of soot reactivity after the exposure to light and NO2. A constant NO2 loss was achieved under irradiation, confirming stable soot reactivity. Other control experiments were performed to confirm the chemical inactivity of the pyrex flow-tube surfaces, and to evaluate the contribution of NO2 photolysis. The empty tube (without soot) was filled with NO2 and exposed to light. NO2 photodissociation (see SI Text) and loss at the pyrex surface were negligible in comparison to the NO2 loss observed in the presence of soot sample.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

C.G. thanks M. Guth for helpful technical support and Agence de l’Environnement et de la Maîtrise de l’Energie for financial support. A.G.F. thanks the “Cluster Chimie Région Rhône Alpes” for the LM doctoral Grant; and M. Aouine and F. Beauchesne-Simonet for the microscopy analysis. D.J.D. acknowledges the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council for financial support, and the European Science Foundation for the award of an Exchange Grant through the Interdisciplinary Tropospheric Research: from the Laboratory to Global Change science programme. M.A. appreciates financial support by the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0908341107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Forster P, et al. Changes in Atmospheric Constituents and in Radiative Forcing. 2007 http://ipcc-wg1.ucar.edu/wg1/wg1-report.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobson MZ. Strong radiative heating due to the mixing state of black carbon in atmospheric aerosols. Nature. 2001;409(6821):695–697. doi: 10.1038/35055518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akhter MS, Chughtai AR, Smith DM. The structure of hexane soot I: Spectroscopic Studies. Appl Spectrosc. 1985;39(1):143–153. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akhter MS, Chughtai AR, Smith DM. The structure of hexane soot II: Extraction studies. Appl Spectrosc. 1985;39(1):154–167. [Google Scholar]

- 5.IARC. Overall evaluations of carcinogenicity: An updating of IARC Monographs volumes 1 to 42. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum Suppl . 1987;7:1–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lary DJ, et al. Carbon aerosols and atmospheric photochemistry. J Geophys Res Atmos. 1997;102(D3):3671–3682. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esteve W, Budzinski H, Villenave E. Relative rate constants for the heterogeneous reactions of NO2 and OH radicals with PAHs adsorbed on carbonaceous particles Part 2: PAHs adsorbed on diesel particulate exhaust SRM 1650a. Atmos Environ. 2006;40(2):201–211. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gross S, Bertram AK. Reactive uptake of NO3, N2O5, NO2, HNO3, and O3 on three types of PAH surfaces. J Phys Chem A. 2008;112(14):3104–3113. doi: 10.1021/jp7107544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kahan TF, Kwamena NOA, Donaldson DJ. Heterogeneous ozonation kinetics of PAHs on organic films. Atmos Environ. 2006;40(19):3448–3459. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mmereki BT, Donaldson DJ. Direct observation of the kinetics of an atmospherically important reaction at the air-aqueous interface. J Phys Chem A. 2003;107(50):11038–11042. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Behymer TD, Hites RA. Photolysis of PAHs adsorbed on fly-ash. Environ Sci Technol. 1988;22(11):1311–1319. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamens RM, Guo Z, Fulcher JN, Bell DA. Influence of humidity, sunlight, and temperature on the daytime decay of PAHs on atmospheric soot particles. Environ Sci Technol. 1988;22(1):103–108. doi: 10.1021/es00166a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamens RM, Karam H, Guo JH, Perry JM, Stockburger L. The behavior of oxygenated PAHs on atmospheric soot particles. Environ Sci Technol. 1989;23(7):801–806. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aubin DG, Abbatt JPD. Interaction of NO2 with hydrocarbon soot: Focus on HONO yield, surface modification, and mechanism. J Phys Chem A. 2007;111(28):6263–6273. doi: 10.1021/jp068884h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirchner U, Scheer V, Vogt R. FTIR spectroscopic investigation of the mechanism and kinetics of the heterogeneous reactions of NO2 and HNO3 with soot. J Phys Chem A. 2000;104(39):8908–8915. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kleffmann J, Becker KH, Lackhoff M, Wiesen P. Heterogeneous conversion of NO2 on carbonaceous surfaces. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 1999;1(24):5443–5450. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saathoff H, et al. The loss of NO2, HNO3, NO3/N2O5, and HO2/HOONO2 on soot aerosol: A chamber and modeling study. Geophys Res Lett. 2001;28(10):1957–1960. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aumont B, et al. On the NO2 plus soot reaction in the atmosphere. J Geophys Res Atmos. 1999;104(D1):1729–1736. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lelievre S, Bedjanian Y, Laverdet G, Le Bras G. Heterogeneous reaction of NO2 with hydrocarbon flame soot. J Phys Chem A. 2004;108(49):10807–10817. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prince AP, Wade JL, Grassian VH, Kleiber PD, Young MA. Heterogeneous reactions of soot aerosols with nitrogen dioxide and nitric acid: Atmospheric chamber and Knudsen cell studies. Atmos Environ. 2002;36(36–37):5729–5740. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brigante M, Cazoir D, D’Anna B, George C, Donaldson DJ. Photoenhanced uptake of NO2 by pyrene solid films. J Phys Chem A. 2008;112(39):9503–9508. doi: 10.1021/jp802324g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ammann M, et al. Heterogeneous production of nitrous acid on soot in polluted air masses. Nature. 1998;395(6698):157–160. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arens F, Gutzwiller L, Baltensperger U, Gaggeler HW, Ammann M. Heterogeneous reaction of NO2 on diesel soot particles. Environ Sci Technol. 2001;35(11):2191–2199. doi: 10.1021/es000207s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerecke A, Thielmann A, Gutzwiller L, Rossi MJ. The chemical kinetics of HONO formation resulting from heterogeneous interaction of NO2 with flame soot. Geophys Res Lett. 1998;25(13):2453–2456. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalberer M, Ammann M, Arens F, Gaggeler HW, Baltensperger U. Heterogeneous formation of nitrous acid (HONO) on soot aerosol particles. J Geophys Res Atmos. 1999;104(D11):13825–13832. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Longfellow CA, Ravishankara AR, Hanson DR. Reactive uptake on hydrocarbon soot: Focus on NO2. J Geophys Res Atmos. 1999;104(D11):13833–13840. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salgado MS, Rossi MJ. Flame soot generated under controlled combustion conditions: Heterogeneous reaction of NO2 on hexane soot. Int J Chem Kinet. 2002;34(11):620–631. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stadler D, Rossi MJ. The reactivity of NO2 and HONO on flame soot at ambient temperature: The influence of combustion conditions. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2000;2(23):5420–5429. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tabor K, Gutzwiller L, Rossi MJ. Heterogeneous chemical-kinetics of NO2 on amorphous-carbon at ambient-temperature. J Phys Chem. 1994;98(24):6172–6186. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chughtai AR, Gordon SA, Smith DM. Kinetics of the hexane soot reaction with NO2/N2O4 at low concentration. Carbon. 1994;32(3):405–416. [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Poppel LH, et al. Electron tomography of nanoparticle clusters: Implications for atmospheric lifetimes and radiative forcing of soot. Geophys Res Lett. 2005;32(24):L24811–10.1029/2005GL024461. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alexander DTL, Crozier PA, Anderson JR. Brown carbon spheres in East Asian outflow and their optical properties. Science. 2008;321(5890):833–836. doi: 10.1126/science.1155296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-Abadleh HA, Grassian VH. Heterogeneous reaction of NO2 on hexane soot: A Knudsen cell and FT-IR study. J PhysChem A. 2000;104(51):11926–11933. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daly HM, Horn AB. Heterogeneous chemistry of toluene, kerosene, and diesel soots. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2009;11(7):1069–1076. doi: 10.1039/b815400g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams PT, Abbass MK, Andrews GE, Bartle KD. Diesel particulate emissions. The role of unburned fuel. Combust Flame. 1989;75(1):1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bejan I, et al. The photolysis of ortho-nitrophenols: A new gas phase source of HONO. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2006;8(17):2028–2035. doi: 10.1039/b516590c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fasnacht MP, Blough NV. Kinetic analysis of the photodegradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in aqueous solution. Aquat Sci. 2003;65(4):352–358. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gollnick K, Schenck GO. Mechanism and stereoselectivity of photosensitized oxygen transfer reactions. Pure Appl Chem. 1964;9:507–525. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dabestani R, Ivanov IN. A compilation of physical, spectroscopic and photophysical properties of PAHs. Photochem Photobiol. 1999;70(1):10–34. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jacobson MZ. Control of fossil-fuel particulate black carbon and organic matter, possibly the most effective method of slowing global warming. J Geophys Res Atmos. 2002;107(D19):4410–10.1029/2001JD001376. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Theurer W. Typical building arrangements for urban air pollution modelling. Atmos Environ. 1999;33:4057–4066. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Acker K, et al. Nitrous acid in the urban area of Rome. Atmos Environ. 2006;40(17):3123–3133. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elshorbany YF, et al. Oxidation capacity of the city air of Santiago, Chile. Atmos Chem Phys Discussion. 2008;8(6):19123–19171. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Su H, et al. Nitrous acid (HONO) and its daytime sources at a rural site during the 2004 PRIDE-PRD experiment in China. J Geophys Res Atmos. 2008;113(D14312):10.1029/2007JD009060. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alvarado MJ, Prinn RG. Formation of ozone and growth of aerosols in young smoke plumes from biomass burning: 1. Lagrangian parcel studies. J Geophys Res Atmos. 2009;114:D09307–10.1029/2008JD011186. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Umbuzeiro GA, et al. Mutagenicity and DNA adduct formation of PAH, nitro-PAH, and oxy-PAH fractions of atmospheric particulate matter from Sao Paulo, Brazil. Mutat Res-Gen Tox En. 2008;652(1):72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.