Abstract

Control of M.tb, the causative agent of TB, requires immune cell recruitment to form lung granulomas. The chemokines and chemokine receptors that promote cell migration for granuloma formation, however, are not defined completely. As immunity to M.tb manifests slowly in the lungs, a better understanding of specific roles for chemokines, in particular those that promote M.tb-protective TH1 responses, may identify targets that could accelerate granuloma formation. The chemokine CCL5 has been detected in patients with TB and implicated in control of M.tb infection. To define a role for CCL5 in vivo during M.tb infection, CCL5 KO mice were infected with a low dose of aerosolized M.tb. During early M.tb infection, CCL5 KO mice localized fewer APCs and chemokine receptor-positive T cells to the lungs and had microscopic evidence of altered cell trafficking to M.tb granulomas. Early acquired immunity and granuloma function were transiently impaired when CCL5 was absent, evident by delayed IFN-γ responses and poor control of M.tb growth. Lung cells from M.tb-infected CCL5 KO mice eventually reached or exceeded the levels of WT mice, likely as a result of partial compensation by the CCL5-related ligand, CCL4, and not because of CCL3. Finally, our results suggest that most T cells use CCR5 but not CCR1 to interact with these ligands. Overall, these results contribute to a model of M.tb granuloma formation dependent on temporal regulation of chemokines rather than on redundant or promiscuous interactions.

Keywords: chemokine, granuloma, pulmonary, murine

Introduction

Following M.tb infection, macrophages and T cell aggregates (granulomas) form at sites of infection to limit bacterial growth through IL-12 [1], TNF [2], IFN-γ [3], and reactive nitrogen intermediate [4] production. Granulomas not only benefit the host by controlling pathogens but also protect adjacent tissue from damage by inflammatory mediators [5,6,7]. Additionally, granulomas may provide a niche for M.tb persistence [8].

Direct comparison between murine and human M.tb granulomas remains controversial [9, 10]. M.tb granuloma formation is predictable in both species, formed by early transient influx of neutrophils, followed by macrophages and lymphocytes. With chronicity, necrosis and fibrosis may develop [11,12,13]. Susceptibility to M.tb is associated with altered granuloma composition. For example, symptom-free M.tb-infected individuals [14, 15] and resistant mouse strains [7, 16] form compact lymphocyte-rich granulomas that limit M.tb growth for extended periods, and in resistant mice the lungs contain numerous antigen-specific, IFN-γ-secreting CD4 T cells [17]. In contrast, patients with active TB [14, 15, 18, 19] and M.tb-susceptible mice [16, 20,21,22] develop large, macrophage-dominated granulomas with few associated lymphocytes. Together, these observations suggest that the capacity for T cell migration may determine disease outcome by promoting functional, lymphocyte-rich granulomas able to control M.tb growth and/or dissemination.

We hypothesized that specific chemokines produced during M.tb infection recruit effector TH1 cells to the lungs for protective granuloma formation. We focused on CCL5 and two of its receptors, CCR5 and CCR1, as they are present in humans and mice infected with M.tb [23, 24], promote lymphocyte migration in vitro [25], and are expressed on TH1 effector cells [26]. Furthermore, CCL5 blockade in vivo decreases immune cell recruitment to granulomas induced by mycobacterial antigen-coated beads [27]. These observations support our hypothesis that CCL5 directs T cell migration in vivo to form lymphocyte-rich granulomas that limit M.tb growth. We studied the consequences of CCL5 deficiency on granuloma formation, antigen-specific responses, and M.tb susceptibility throughout early and chronic M.tb infection. Following a low-dose M.tb aerosol infection, our data demonstrated that CCL5 recruited early IFN-γ-producing, antigen-specific T cells to the lungs and promoted lymphocyte-rich granulomas, which controlled M.tb growth. Furthermore, the absence of CCL5 was not associated with T cell-priming defects, indicating that delayed T cell migration to the lungs was not a result of a failure to generate acquired immunity. Overall, in vivo CCL5 primarily mediates T cell migration to M.tb-infected lungs for optimal granuloma formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Specific pathogen-free, 4- to 8-week-old female C57BL/6 (Stock Number 000664, strain C57BL/6J) and CCL5 KO (Stock Number 005090, strain B6.129P2-Ccl5tm1Hso/J) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). The CCL5 KO mice were developed by disrupting exon I of ccl5 in 129P2/OlaHsd-derived E14 embryonic stem cells, and appropriately targeted chimeric animals were backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice for at least nine generations. CCL5 KO mice are maintained currently by homozygote-homozygote matings [28]. C57BL/6 WT mice (see Fig. 1, A, C, and D) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA). All mice were maintained in ventilated cages within Biosafety Level 3 facilities at The Ohio State University (Columbus, OH, USA) and provided with sterile food and water ad libitum. The Ohio State University’s Institutional Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee approved all protocols.

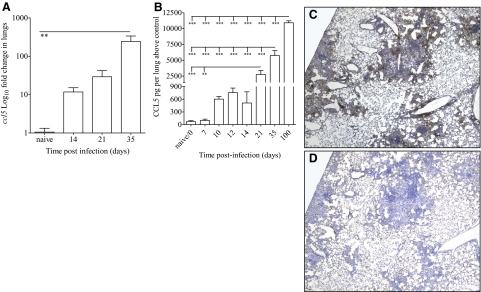

Figure 1.

CCL5 gene and protein expression in M.tb-infected mice. WT mice were infected with 50–100 M.tb Erdman CFU by aerosol, killed at the indicated time-points, and lung samples analyzed for relative ccl5 gene expression by real-time PCR (A), CCL5 protein by ELISA (B), and localization of CCL5 to granulomas by immunohistochemistry (C), compared with isotype control antibody (D). Data shown are the mean ± sem of four to eight mice/time-point (A) and combined data from at least two independent experiments each with four to five mice/time-point (B), analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test (**, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001). The photomicrographs represent one of four individual mice at Day 120 of M.tb infection (C and D).

M.tb stocks

M.tb Erdman (ATCC #35801) was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Stocks were grown in Proskauer-Beck liquid medium containing 0.05% Tween 80 to mid-log phase and frozen in 1 ml aliquots at –80°C.

M.tb infection

Mice were infected with 50–100 M.tb Erdman CFU using an inhalation exposure system (Glas-col, Terre Haute, IN, USA). M.tb burden was determined by plating serial dilutions of lung or MLN homogenates onto oleic acid, albumin, dextrose, and catalase-supplemented 7H11 agar and counting CFUs after 3 weeks at 37°C. For experiments lasting longer than 90 days, mice were weighed weekly. Mice with 20% weight loss, as compared with age- and sex-matched noninfected control animals with concurrent signs of disease (unthrifty hair coats, tachypnea, social isolation), were killed and excluded from the experiments.

Cytokine and chemokine quantification

Lung homogenates were centrifuged briefly, and clarified supernatants were assayed for CCL5, CCL4, and CCL3 by ELISA using DuoSet kits from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). MLN cell cultures were frozen at –80°C, and IFN-γ was detected by ELISA using a kit from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA).

Real-time PCR

Right medial lung lobes from individual mice were homogenized in 1 ml UltraSpec (Biotecx, Houston, TX, USA) and frozen rapidly at –80°C. Total RNA was isolated by following the manufacturer’s instructions, and 1 μg was reverse-transcribed using an Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Real-time PCR was performed with an iQ5 real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using TaqMan gene expression assays for ccl5 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The ΔΔ cycle threshold method was used for relative quantification of mRNA expression using 18S as an endogenous normalizer and samples from naïve mice as calibrators for relative gene expression.

Lung histology

The right cranial lung lobes from individual mice were inflated with 10% neutral-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, and stained with H&E or Ziehl-Neelsen’s acid-fast stain. A board-certified veterinary pathologist without knowledge of the groups evaluated glass slides. Digital images of 10 serial sections/group/time-point were captured using a scan scope (Aperio, Vista, CA, USA). The average granuloma diameter was calculated from two perpendicular measurements of cell aggregates visible at 4× magnification using Aperio Image Scope, v8.2.5.

Lung immunohistochemistry

The right cranial lung lobes from individual mice were inflated with 30% OCT in PBS, snap-frozen for 10 min on the Peltier element of a Leica CM 1850 cryostat, and stored at –80°C until the conclusion of the experiment. Blocks acclimated to –35°C were sectioned at 5 μm. Sections were fixed for 2–5 min in cold acetone, air-dried, and stained with H&E, anti-CD4 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), anti-CD8 (Abcam), anti-CCL5 (R&D Systems), or an appropriate isotype control. Positive immunohistochemical staining was determined using biotinylated secondary antibodies with HRP conjugation (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and developed with 3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride substrate (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA).

Lung cell isolation

Lungs of noninfected and M.tb-infected mice were removed aseptically following perfusion through the heart with 10 ml PBS containing 50 U/ml heparin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA). Lungs were then placed in DMEM (500 ml; Mediatech, Herndon, VA, USA), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Atlas Biologicals, Fort Collins, CO, USA), 1% HEPES buffer (Sigma Chemical Co.), 10 ml 100× nonessential amino acid solution (Sigma Chemical Co.), 5 ml penicillin/streptomycin solution (50,000 U penicillin, 50 mg streptomycin, Sigma Chemical Co.), and 0.14% ME (complete DMEM). Lungs were diced with sterile razor blades, followed by a 30-min incubation at 37°C with 4 ml complete DMEM containing collagenase XI (0.7 mg/ml, Sigma Chemical Co.) and bovine pancreatic DNase (30 μg/ml, Sigma Chemical Co.). Complete DMEM (6 ml) was added subsequently to dilute enzymatic activity, and lung pieces were pressed through sterile 70 μm nylon mesh screens (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) to obtain a single-cell suspension. Residual RBCs were lysed using 2 ml ammoniumchloride/potassium carbonate (0.15 M NH4Cl, 1 mM KHCO3) for 3 min at room temperature, followed by washing with complete DMEM. Viable cells were counted using trypan blue exclusion and resuspended at working concentrations in complete DMEM or fixed for flow cytometry as described below.

Lung cell culture for IFN-γ ELISPOTS

Lung cells (2.5×105) from individual mice were serially diluted 1:2 in complete DMEM for at least four dilutions onto precoated and blocked ELISPOT plates (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Ready-Set-Go mouse IFN-γ ELISPOT kit, eBioscience). Lung cells were incubated with 10 μg/ml OVA or equal volumes of complete DMEM (negative control), 10 μg/ml M.tb CFP, 5 μg/ml M.tb ESAT-6, or 1 μg/ml anti-CD3 (BD Biosciences), plus 0.1 μg/ml anti-CD28 (BD Biosciences; positive control) at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 24 h, supernatants were removed, and spots were detected as per the manufacturer’s instructions (eBioscience). SFUs were counted and analyzed using the Immunospot analyzer (C.T.L., Cleveland, OH, USA). Antigen-specific, IFN-γ SFUs were determined by subtracting the number of spots formed in the presence of the negative control.

Lymph node cell isolation

Three lung-draining MLNs from each individual mouse were harvested with small curved forceps and pressed gently through sterile 70 μm nylon mesh screens (BD Biosciences) to obtain single-cell suspensions. Residual RBCs were lysed as described above. Viable cells were counted using trypan blue exclusion and resuspended for flow cytometry, or 2.5 × 105 cells/well were cultured in complete DMEM at 37°C, 5% CO2, for 18 h with monensin present for the last 12 h to inhibit cytokine secretion, as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Cytofix/Cytoperm™ fixation/permeabilization solution kit with BD GolgiStop™, BD Biosciences). Separate aliquots of 2.5 × 105 MLN cells were cultured for 24 h with 10 μg/ml OVA or equal volumes of complete DMEM (negative control), 10 μg/ml M.tb CFP, 5 μg/ml M.tb ESAT-6, or 1 μg/ml anti-CD3 (BD Biosciences), plus 0.1 μg/ml anti-CD28 (BD Biosciences; positive control) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cultures were frozen at –80°C and stored until analysis by ELISA.

Flow cytometry

The following antibodies and isotype controls were purchased from BD Biosciences: Fc Block™ (clone 2.462), allophycocyanin anti-CD11c (HL3), PE anti-CD11c (HL3), PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-CD11b (M1/70), PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-CD3ε (145-2C11), allophycocyanin-Cy7 anti-CD4 (GK1.5), PE-Cy7 anti-CD8 (53-6.7), PerCP anti-CD8 (53-6.7), FITC anti-IA/I-E (2G9), FITC rat IgG2a (2G9), PE anti-CD195 (C34-3448), PE rat IgG2c (C34-3448), PE anti-IL-2 (3C7), and PE rat IgG2a. In some experiments, PE anti-CD195 (HM-CCR5) and PE hamster IgG isotype control were obtained from Biolegend (San Diego, CA, USA). Anti-CCR1, rabbit polyclonal IgG, and rabbit F(ab)2, obtained from Abcam, were conjugated with allophycocyanin, as per the manufacturer’s instructions (PhycoLink APC conjugation kit, Prozyme, San Leandro, CA, USA). In some experiments, purified rabbit polyclonal anti-CCR1 (Imgenex, San Diego, CA, USA) was detected with FITC goat anti-rabbit IgG (Imgenex), following blocking with 25 μg/ml purified goat IgG (R&D Systems).

For flow cytometry, aliquots of 5 × 105 to 2.5 × 106 lung or lymph node cells from individual mice were fixed in FACS buffer [deficient RPMI (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA, USA), supplemented with 0.1% sodium azide (Sigma Chemical Co.)] for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were then incubated with 0.31–0.62 μg Fc Block™ for 10 min at room temperature to minimize nonspecific antibody binding. For surface staining, samples were incubated with 0.31 μg antibody (BD Biosciences) or dilutions recommended by the manufacturers’ instructions (BioLegend and Imgenex), or dilutions established following in-house optimizations (Abcam). Antibody incubations were performed in the dark for 20–30 min at 4°C, followed by at least three washes in FACS buffer.

For in vivo quantification of T cell apoptosis/necrosis, live lung cells were washed in cold PBS and stained with FITC-labeled Annexin V and PI in binding buffer, as per the manufacturer’s instructions (FITC:Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I, BD Biosciences). Lung cells were subsequently fixed in FACS buffer and then labeled with anti-CD3, anti-CD4, and anti-CD8, as described above.

For calculating in vivo T cell proliferation in lymph nodes and lungs, mice were injected with BrdU 24–36 h prior to euthanasia, as per the manufacturer’s instructions (BrdU flow kit, BD Biosciences). Single-cell suspensions were then surface-labeled with fluorescent antibodies, permeabilized, and labeled with anti-BrdU, anti-CCR5, anti-CCR1, anti-IL-2, or isotype controls, as per the manufacturer’s instructions (BrdU flow cytometry kit, BD Biosciences) for detection of intracellular molecules. In some experiments, lung cells were permeabilized with 0.3% saponin in PBS for 15 min at 4°C, incubated with antibodies in 0.1% saponin in PBS, and washed three times with 0.1% saponin in PBS.

In all flow cytometry experiments, final washes were performed in FACS buffer, and cells resuspended in 200–300 μl FACS buffer prior to reading on an LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Lymphocytes were identified according to their characteristic forward- and side-scatter profiles, and 20,000–100,000 events were counted within that gate/sample. Results from individual mice were analyzed with FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). Isotype controls were used to set gates for analysis.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 4 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Multigroup comparisons were analyzed with one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-test. Pairwise comparisons at the same time-points used the Student’s t-test. Statistical significance in all analyses was defined as *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001. Where necessary, outliers were removed following identification with the Grubb’s outlier test (QuickCalcs, GraphPad Software, http://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs).

RESULTS

CCL5 gene and protein expression in M.tb-infected lungs

The kinetics of ccl5 gene and protein expression in the lungs, as well as CCL5 localization to granulomas, was established following a low-dose aerosol M.tb infection. As expected, CCL5 protein was not detected in the lungs of naïve or M.tb-infected CCL5 KO mice (data not shown). In WT mice, ccl5 mRNA expression (Fig. 1A) and protein levels (Fig. 1B) increased over time during M.tb infection, similar to results published previously [23]. CCL5 protein was also localized to M.tb granulomas (Fig. 1C), as compared with the isotype control (Fig. 1D), as published previously [29]. Abundant CCL5 was present at the periphery of granulomas, closely associated with the macrophage–lymphocyte interface, suggesting that CCL5 secretion in M.tb-infected lungs contributes to granuloma formation.

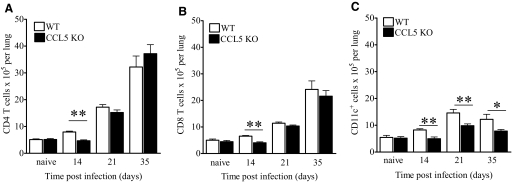

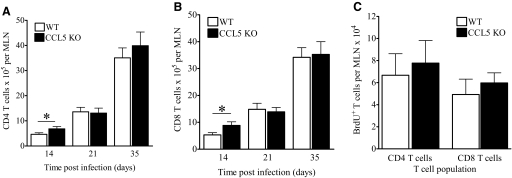

CCL5 recruits immune cells to M.tb-infected lungs

CCL5 protein levels [20] and ccl5 gene polymorphisms [30, 31] are associated with M.tb susceptibility in mice and humans, respectively. To determine a role for CCL5 during M.tb infection, we used CCL5 KO mice and C57BL/6 WT controls, hypothesizing that the lack of CCL5 would diminish immune cell migration to M.tb-infected lungs. As anticipated, the numbers of CD4 T cells (Fig. 2A) and CD8 T cells (Fig. 2B) in CCL5 KO lungs were moderately but significantly lower than WT controls at Day 14 of M.tb infection. Reduced lung T cells were not a result of increased apoptosis/necrosis in CCL5 KO mice, as determined by Annexin V and PI staining (data not shown). At Day 14 of M.tb infection, the lungs of CCL5 KO mice contained fewer BrdU+ CD4 and CD8 T cells than did WT lungs (data not shown), compatible with impaired T cell proliferation [32] or impaired migration of T cells which proliferated recently in the MLNs. By 21 and 35 days, however, CD4 and CD8 T cell numbers were similar, regardless of CCL5 status. These results indicate that CCL5 was required for early CD4 and CD8 T cell accumulation in the lungs and suggest that additional chemokines recruited T cells at later time-points of M.tb infection.

Figure 2.

Numbers of lung immune cells from M.tb-infected CCL5 KO and WT mice. Mice were infected with 50–100 M.tb Erdman CFU by aerosol, killed at the indicated time-points, and lung cells fluorescently labeled with anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, and anti-CD11c for flow cytometry. The numbers of CD4 T cells (A), CD8 T cells (B), and CD11c+ cells (C) are shown. Data are the mean ± sem of two independent experiments each with four to five mice/group/time-point, analyzed by the Student’s t-test (*, P<0.05; **, P<0.01) at each time-point.

It has been reported that CCL5 KO mice recruit fewer macrophages to sites of dermal inflammation [32]. To determine the contribution of CCL5 to innate immune cell localization to the lungs during M.tb infection, CD11c+ cells were quantified in the lungs of CCL5 KO and WT mice. CD11c is expressed at variable levels by alveolar macrophages, dendritic cells, and subpopulations of small macrophages and monocytes within mouse lungs [33]. The lungs of CCL5 KO mice contained significantly fewer CD11c+ cells than WT controls at all time-points tested (Fig. 2C). To confirm that CCL5 contributed specifically to macrophage and monocyte localization to the lungs, macrophage, monocyte, and granulocyte populations were discriminated with CD11c and CD11b expression [33]. At Day 14 of M.tb infection, the lungs of CCL5 KO mice contained fewer alveolar macrophages (CD11chi/CD11bmid-lo), fewer monocytes, and small macrophages (CD11cmid/CD11bmid, CD11c–/CD11bmid-lo) but equivalent numbers of granulocytes (CD11c–/CD11bhi), as compared with WT mice (Supplemental Fig. 1, A–D). Lung dendritic cells (CD11chi/CD11bhi) were not visualized as a discrete cell population in our analysis and therefore, were not enumerated. Together, these data demonstrate that CCL5 was required for optimal monocyte and macrophage migration but not necessary for granulocyte influx during M.tb infection. As seen with T cells, a fraction of CD11c+ cells entered the lungs in the absence of CCL5, illustrating that additional chemokines contributed to the monocyte and macrophage recruitment.

Overall, CCL5 was required for recruiting multiple types of potentially protective immune cells to the lungs during early M.tb infection. CCL5 promoted early T cell accumulation before 3 weeks of M.tb infection and mediated CD11c+ cell recruitment for at least 5 weeks of M.tb infection.

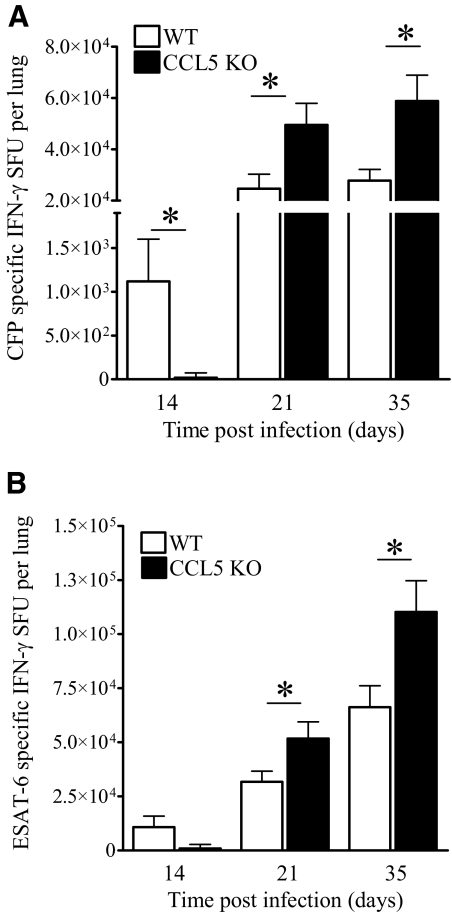

CCL5 recruits early antigen-specific, IFN-γ-producing cells to M.tb-infected lungs

As the number of immune cells may not positively correlate with protection against M.tb, we next determined how the absence of CCL5 affected protection against M.tb by quantifying antigen-specific, IFN-γ-producing cells. IFN-γ is required for resistance to M.tb [3, 34] and may be a correlate of protection in mice and humans [17, 35]. M.tb CFP was included to evaluate broad antigen-specific responses, and ESAT-6 tested recognition of an immunodominant M.tb antigen. The numbers of M.tb CFP (Fig. 3A)- and M.tb ESAT-6 (Fig. 3B)-specific, IFN-γ-producing cells in the lungs were reduced in CCL5 KO mice at Day 14 of M.tb infection. In contrast, by Days 21 and 35, the numbers of CFP-specific and ESAT-6-specific, IFN-γ-producing lung cells were increased significantly in CCL5 KO mice compared with WT. There were more ESAT-6-specific, IFN-γ-producing lung cells than the number of CFP-specific, IFN-γ-producing lung cells, likely as a result of abundant exogenous ESAT-6 and preferential ESAT-6 peptide presentation. Overall, the absence of CCL5 delayed but did not prevent the manifestation of M.tb antigen-specific immunity in the lungs.

Figure 3.

Numbers of IFN-γ-producing lung cells from M.tb-infected CCL5 KO and WT mice. Mice were infected aerogenically with 50–100 CFU M.tb Erdman, killed at the indicated time-points, and lung cells stimulated with M.tb CFP (A) or ESAT-6 (B) for 24 h. The numbers of antigen-specific, IFN-γ-producing lung cells were determined by ELISPOT, subtracting spots detected in response to OVA from spots formed in the presence of M.tb CFP or M.tb ESAT-6. Data are the mean ± sem of two independent experiments, each with four to five mice/group/time-point, analyzed by the Student’s t-test (*, P<0.05) at each time-point.

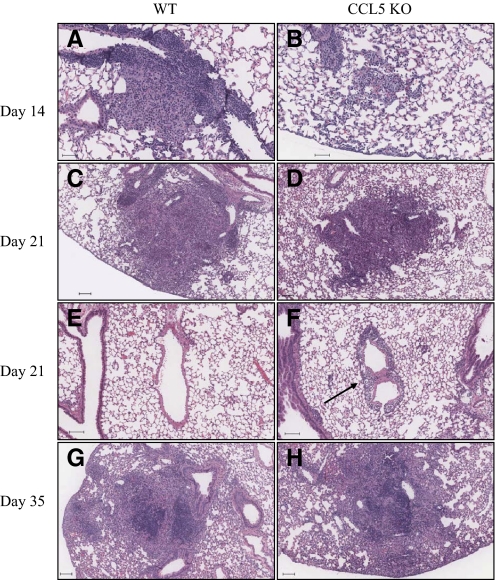

CCL5 promotes early formation of M.tb lung granulomas

CCL5 was necessary for recruitment of macrophages, monocytes, CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, and antigen-specific, IFN-γ-producing cells to the lungs following M.tb infection. However, flow cytometry and antigen-stimulation assays cannot evaluate granuloma formation. Therefore, despite isolation of abundant IFN-γ-producing cells from the lungs of CCL5 KO mice, immune cells may have been dispersed throughout the lungs and not localized to granulomas. This was important to address, as granulomas provide necessary cell-to-cell contact for induction of protective immunity and reflect the functional capacities of M.tb growth inhibition and minimize lung tissue damage. A board-certified veterinary pathologist evaluated sections of M.tb-infected lungs. The absence of CCL5 did not abolish granuloma formation, but subtle differences suggested altered immune cell trafficking in the lungs of CCL5 KO mice as compared with WT mice. This was evident by small, loosely organized inflammatory foci at Day 14 of M.tb infection in CCL5 KO mice (Fig. 4B). At that same time-point in WT mice, the lungs contained discrete granulomas with the typical cellular composition of epithelioid macrophages, lymphocytes, and neutrophils (Fig. 4A). At Day 21 of M.tb infection in CCL5 KO mice, perivascular interstitial lymphocytes were prominent (Fig. 4F), as compared with the lungs of WT mice (Fig. 4E). Localization of lymphocytes within perivascular, peribronchiolar, and alveolar septal interstitial tissue spaces suggests that immune cells were migrating toward, but had not yet encountered, M.tb-infected macrophages. By Day 35 of M.tb infection, the morphology of lung granulomas was similar in WT (Fig. 4G) and CCL5 KO (Fig. 4H) mice.

Figure 4.

M.tb lung granulomas in CCL5 KO and WT mice. Mice were infected by aerosol with 50–100 M.tb Erdman CFU and killed at the time-points indicated. Lung lobes from individual mice were inflated and fixed with 10% neutral-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, stained with H&E, and digitally scanned. Granulomas/inflammatory foci from WT and CCL5 KO are shown. Granulomas are shown in WT mice (A), compared with inflammatory foci in CCL5 KO mice (B) at Day 14 of M.tb infection. (C and D) Similar granulomas in WT and CCL5 KO mice at Day 21 of M.tb infection. Lungs of CCL5 KO mice contain prominent perivascular interstitial lymphocytes (F, arrow) compared with lungs of WT mice (E) at Day 21 of M.tb infection. By Day 35, similar granulomas are shown in WT and CCL5 KO mice (G and H, respectively). A, B, E, and F scale bars = 50 μm; C, D, G, and H scale bars = 100 μm.

At all time-points, CD4+ and CD8+ cells were detected by immunohistochemical staining within the granulomas of CCL5 KO and WT mice (Supplemental Fig. 2, and data not shown). Together, these results indicate that CCL5 KO mice had altered immune cell trafficking but were eventually capable of M.tb granuloma formation with appropriate CD4+ and CD8+ cell localization.

The size of granulomas in CCL5 KO and WT mice at Day 14 of M.tb infection was not significantly different (Table 1). By 21 and 35 days, however, lung granulomas in CCL5 KO mice were significantly larger and more frequent than granulomas in WT mice. These results correspond with the increasing numbers of T cells and abundant, antigen-specific, IFN-γ-producing cells in the lungs of CCL5 KO mice (Fig. 2). Therefore, in the absence of CCL5, protective T cells were delayed in entering M.tb-infected lungs. The T cells that eventually migrated, however, were able to traffic to M.tb-infected macrophages and form granulomas.

TABLE 1.

M.tb Lung Granulomas in CCL5 KO and WT Mice

| Days of M.tb infection | Genotype | Cell distribution | Average diameter ± sem (μm) of inflammatory foci or granulomas | Frequency of granulomas >500 μm in diameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noninfected | WT | No inflammation or granulomas | N/A | N/A |

| Noninfected | CCL5 KO | No inflammation or granulomas | N/A | N/A |

| 14 | WT | Granulomas | 211 ± 15 | 0% |

| CCL5 KO | Small inflammatory foci | 202 ± 12 | 0% | |

| 21 | WT | Granulomas and mild interstitial inflammation | 403 ± 35 | 28% |

| CCL5 KO | Granulomas and widespread interstitial inflammation | 495 ± 95a | 44% | |

| 35 | WT | Granulomas | 274 ± 10 | 16% |

| CCL5 KO | Granulomas | 645 ± 40b | 39% |

Mice were infected by aerosol with 50–100 M.tb Erdman CFU and euthanized at the time-points indicated. Lung lobes from individual mice were inflated and fixed with 10% neutral-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, and stained with H&E. Results have been summarized from analysis of 10 serial sections/time-point of one experiment with four mice/group/time-point. Statistical analysis of the average granuloma diameter was performed by the Student’s t-test at each time-point (

P < 0.05;

P < 0.001). N/A, Not applicable.

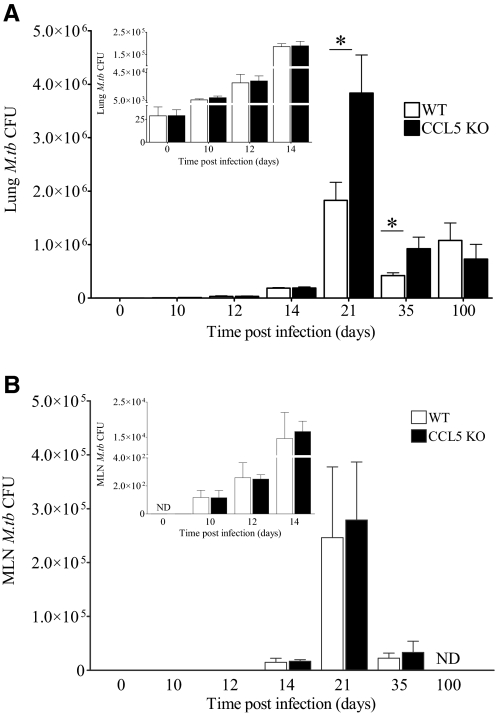

Increased M.tb burden in the lungs of CCL5 KO mice

As recruitment of many types of immune cells was transiently diminished by the absence of CCL5, we hypothesized that CCL5 KO mice would have impaired control of M.tb growth in the lungs. Following a low-dose aerosol infection, the lungs of CCL5 KO and WT mice contained similar M.tb burdens at 0, 10, 12, and 14 days (Fig. 5A, inset), a time-frame associated with innate pulmonary immune responses to M.tb [36]. Although the lungs of M.tb-infected CCL5 KO mice contained fewer monocytes and macrophages than WT mice (Fig. 2C and Supplemental Fig. 1), these similarities in M.tb growth over the first 2 weeks of infection suggest that innate immune cells functioned normally in the absence of CCL5. At time-points associated with adaptive immune control of M.tb infection [36], Days 21 and 35, the lungs of CCL5 KO mice contained significantly more M.tb CFU than the lungs of WT mice (Fig. 5A). M.tb burden declined to equivalent levels in CCL5 KO and WT mice by Day 100 of infection, indicating that CCL5 was not required for maintenance of a chronic M.tb infection (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

M.tb burden in the lungs and MLNs of CCL5 KO and WT mice. Mice were infected with 50–100 CFU M.tb Erdman by aerosol, killed at the indicated time-points, and M.tb burden determined by plating lung (A) or MLN (B) homogenates onto supplemented 7H11 agar and counting CFU after 21 days at 37°C. Results shown are the combined average ± sem of two independent experiments (A) or one experiment (B) with four to five mice/group/time-point, analyzed by the Student’s t-test (*, P<0.05). For ease of comparison, insets show the same data on a smaller scale. ND, Not determined.

Delayed T cell migration to the lungs of CCL5 KO mice may have been a consequence of insufficient antigens to generate protective acquired immunity. To rule out limited antigen availability, M.tb CFUs were calculated from homogenized MLNs (Fig. 5B). M.tb burdens were similar in CCL5 KO and WT mice at the time-points tested, suggesting that antigen levels were sufficient and that M.tb-infected dendritic cells did not require CCL5 for efficient migration.

Overall, these results demonstrate that CCL5 recruits IFN-γ-producing, protective CD4 and CD8 T cells to the lungs prior to 3 weeks of infection, which in turn, inhibits M.tb growth that can be detected by CFU assays at 3 and 5 weeks. In the absence of CCL5, recruitment of protective immune cells is delayed, allowing M.tb growth to continue and the peak M.tb burden to double. Protective immunity in the absence of CCL5 eventually controlled and stabilized M.tb, likely through the production of other chemokines responsible for T cell recruitment.

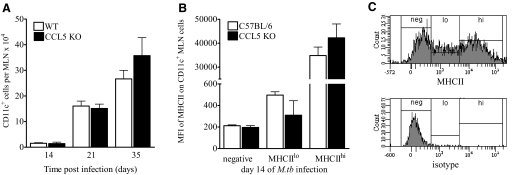

CCL5 is not required for T cell priming during M.tb infection

The previous results demonstrate that the absence of CCL5 transiently impaired T cell migration and M.tb control in the lungs but did not affect antigen delivery to the lung-draining MLNs. Although CCL5 is not involved directly in immune cell homeostatic trafficking to lymph nodes [37], exposure to CCL5 enhances immature dendritic cell migration under in vitro inflammatory conditions [38]. The absence of CCL5, therefore, may impair dendritic cell migration to the MLNs in vivo during M.tb infection. To address this possibility, the numbers of CD11c+ cells (a marker of dendritic cells in lymphoid organs [39]) in the MLNs were enumerated in M.tb-infected, CCL5 KO, and WT mice. Lymph nodes contained similar numbers of CD11c+ cells over the first 5 weeks of M.tb infection (Fig. 6A), illustrating that dendritic cell migration during M.tb infection was not dependent on CCL5. Although we cannot completely rule out the possibility that CD11c+ lymph node cells represented infiltrating macrophages and monocytes, attempts at discriminating these cell populations, with additional markers such as CD11b, CD83, and CCR7, were unsuccessful by flow cytometry (data not shown). Furthermore, CD11c+ cells from CCL5 KO and WT mice expressed similar levels of MHCIIhi and MHCIIlo (Fig. 6, B and C), suggesting that the dendritic cell maturation was intact in CCL5 KO mice.

Figure 6.

CD11c+ cells in the MLNs of CCL5 KO and WT mice. Mice were infected with 50–100 CFU M.tb Erdman by aerosol, killed at the indicated time-points, and MLN cells were harvested, fixed, and labeled with anti-CD11c (A) and anti-MHCII or rat IgG2b isotype control to determine the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of MHCII expression of CD11c+ cells (B). Representative flow cytometry histograms (C) show gating strategies (upper panel) based on the isotype control (lower panel). Data are the mean ± sem of two independent experiments (A) or one experiment (B and C), each with three to five mice/group/time-point, analyzed by the Student’s t-test (*, P<0.05) at each time-point. No statistically significant differences were identified.

We next determined whether the absence of CCL5 affected T cell priming by evaluating the numbers, proliferation, and function of CD4 and CD8 T cells in the MLNs. As the absence of CCL5 delayed the manifestation of protective immunity in the lungs, we hypothesized that CCL5 KO mice would have equivalent or more MLN T cells than WT mice. Indeed, total cells (data not shown), CD4 T cells (Fig. 7A), and CD8 T cells (Fig. 7B) were increased in lymph nodes from CCL5 KO mice at Day 14 of M.tb infection as compared with WT controls. These differences were not apparent at later time-points, corresponding to the formation of lung granulomas in CCL5 KO mice (Fig. 4 and Table 1). These results confirm that CCL5 was not required for T cell trafficking to MLNs during M.tb infection. Furthermore, the lymph nodes of CCL5 KO and WT mice contained similar numbers of BrdU+ CD4 T cells and BrdU+ CD8 T cells (Fig. 7C), demonstrating that in the absence of CCL5, T cells underwent normal clonal expansion. To quantify antigen-specific responses in the lymph nodes at Day 14 of M.tb infection, the numbers of IL-2+ CD4+ and IL-2+ CD8+ cells were enumerated by intracellular flow cytometry following TCR-mediated stimulation by anti-CD3 and anti-CD28. No differences were detected in the proportions of IL-2+ T cells by this method (data not shown). Similarly, no consistent differences were detected in the amounts of M.tb CFP- or ESAT-6-specific IFN-γ from CCL5 KO or WT MLN cell cultures (data not shown). These results demonstrate that MLN antigen-specific cytokine responses were intact in CCL5 KO mice.

Figure 7.

T cells from the MLNs of M.tb-infected, CCL5 KO, and WT mice. Mice were aerogenically infected with 50–100 CFU M.tb Erdman and killed at the indicated time-points. MLN cells were harvested, fixed, and labeled with anti-CD3, anti-CD4, and anti-CD8. The absolute numbers of CD4 T cells (A) and absolute numbers of CD8 T cells (B) were calculated. In separate experiments, mice were injected with BrdU 24 h prior to euthanasia, and MLN cells were fixed and labeled with anti-CD3, anti-CD4, and anti-CD8, permeabilized, and labeled with anti-BrdU or isotype control. The numbers of BrdU+ CD4 T cells and BrdU+ CD8 T cells were calculated (C). Data shown are the combined average ± sem of two experiments (A–C) with four to five mice/group analyzed by the Student’s t-test; *, P < 0.05.

Together, with our previous data illustrating equivalent antigen load and dendritic cell numbers/function in CCL5 KO as WT mice, these results provide further evidence that T cell priming/proliferation was unaffected by the absence of CCL5. Overall, this evidence supports our hypothesis that CCL5 funcitons primarily during M.tb infection to localize acquired immune cells to the lungs, forming early, protective granulomas.

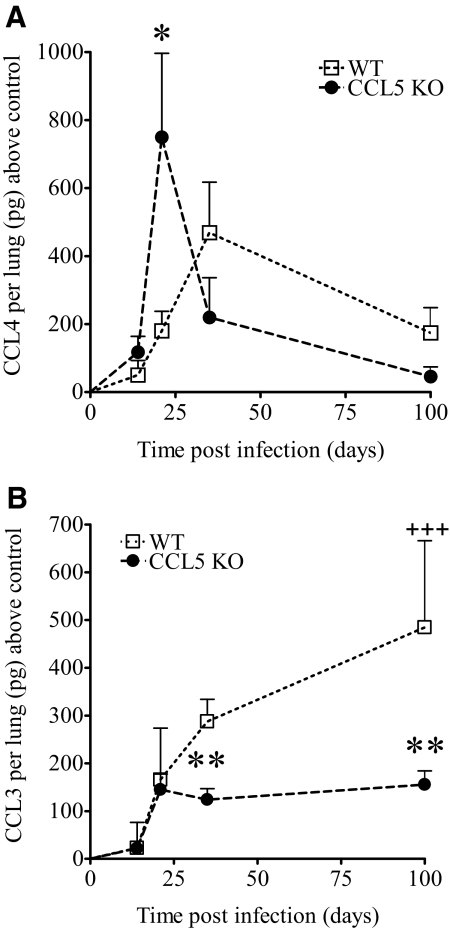

CCL4, not CCL3, partially compensates for the lack of CCL5 during early M.tb infection

The results using CCL5 KO mice established that CCL5 was important for early, protective M.tb-specific immunity and granuloma formation in the lungs, and delayed immune cell migration was not a consequence of defective T cell priming. It was apparent that additional chemokines participated in T cell migration and granuloma formation, as CCL5 KO mice eventually localized antigen-specific cells to the lungs, formed granulomas, and controlled M.tb. To determine which CCL5-related ligand(s) may have recruited CD4 and CD8 T cells to M.tb-infected lungs, the levels and kinetics of CCL4 (Fig. 8A) and CCL3 (Fig. 8B) were determined during acute and chronic infection. CCL4 and CCL3 share receptors (CCR5 and CCR1) with CCL5, and those receptors are expressed by TH1 and effector T cells [40,41,42,43]—the T cells that mediate M.tb resistance in humans and mice [36, 44,45,46,47,48]. CCL4 protein levels in M.tb-infected lungs peaked earlier and achieved significantly higher levels in CCL5 KO mice than in WT controls. Therefore, rapid and abundant CCL4 was produced when CCL5 was absent. This demonstrates that up-regulation of CCL4 may compensate partially for the lack of CCL5 and may have recruited the abundant IFN-γ-producing cells evident in the lungs of CCL5 KO mice at 3 and 5 weeks of M.tb infection.

Figure 8.

CCL4 and CCL3 levels in the lungs of M.tb-infected CCL5 KO and WT mice. Mice were infected aerogenically with 50–100 CFU M.tb Erdman, killed at the indicated time-points, and CCL4 (A) and CCL3 (B) protein was measured by ELISA in homogenized lung tissue. Data are the combined average ± sem of two independent experiments, each with four to five mice/group/time-point, except for Day 100, for which one experiment has been performed. Data were analyzed by the Student’s t-test (*, P<0.05; **, P<0.01) at each time-point and by one-way ANOVA over time with Tukey’s post-test (+++, P<0.001). No differences were noted between noninfected CCL5 KO and WT mice (data not shown).

In contrast to CCL4, the lung levels of CCL3 were not increased in CCL5 KO mice, and no significant differences were detected during the first 3 weeks of infection when compared with WT mice (Fig. 8B). By Day 35 and continuing until Day 100 of M.tb infection, lung CCL3 increased significantly over time in WT mice but remained low and stable in the lungs of CCL5 KO mice. These results suggest that CCL3 production did not compensate for the lack of CCL5. Furthermore, low CCL3 in CCL5 KO mice may be a consequence of lower numbers of CD11c+ cells (Fig. 2), as macrophages are a major cell source of CCL3 [49]. The absence of CCL5, therefore, may have secondary consequences on cellular recruitment during chronic M.tb infection. To determine whether the lack of CCL5 affected outcome of M.tb infection, survival was monitored in a group of CCL5 and WT mice for 300 days. No significant differences in survival were detected (data not shown), indicating that the lack of CCL5 or secondary consequences did not alter survival.

Overall, these data illustrate that T cell migration to pulmonary M.tb granulomas follows temporal expression patterns of chemokine production that may not reflect the functional redundancies observed in vitro. For example, although CCL4 was produced earlier and more abundantly in the lungs of CCL5 KO mice than WT mice (Day 21 vs. Day 35), accelerated production did not completely compensate for the lack of CCL5, as evident by low numbers of T cells and low IFN-γ-producing cells at Day 14 of M.tb infection. Furthermore, it is unlikely that CCL3 compensates for the lack of CCL5, as levels were similar in CCL5 KO and WT mice over 3 weeks of M.tb infection and then declined.

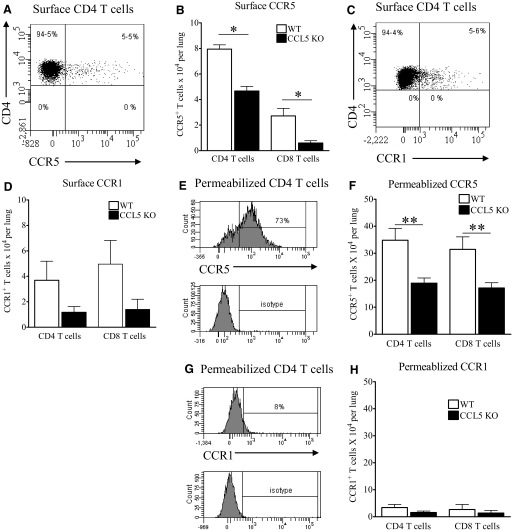

T cells internalize CCR5, not CCR1, in M.tb-infected lungs

Using CCL5 KO mice, we demonstrated that CCL5 recruited early, protective acquired immune cells to M.tb-infected lungs. To determine the T cell chemokine receptor requirements for CCL5-dependent T cell migration in the lungs, CCR5 and CCR1 were evaluated. We focused on CCR5 and CCR1, as they promote migration of effector and TH1 cells [40,41,42,43]—the cells considered most protective against M.tb.

We focused on Day 14 of M.tb infection, as this time-point showed consistently that the absence of CCL5 reduced the number of lung T cells and antigen-specific, IFN-γ-producing cells. In CCL5 KO mice, the numbers of surface CCR5+ T cells in the lungs were lower than in WT mice (Fig. 9, A and B), indicating that CCL5 and additional CCR5 ligands contribute to T cell migration. As chemokine receptors are endocytosed following ligand binding [50], we next permeabilized the lung cells and labeled with anti-CCR5 to detect intracellular receptors as a marker of chemokine-mediated migration. As the majority of CD4 T cells (Fig. 9A) and CD8 T cells (data not shown) internalized CCR5, the numbers of CCR5+ T cells in the lungs increased nearly fivefold following permeabilization (Fig. 9F). Overall, these results suggest that T cells use CCR5 to migrate within M.tb-infected lungs. In CCL5 KO mice, the numbers of permeabilized CCR5+ T cells were reduced to approximately half of that detected in WT mice, again illustrating that additional CCR5 ligands, such as CCL4, promote T cell migration during early M.tb infection but cannot fully compensate for the absence of CCL5.

Figure 9.

CCR5 and CCR1 T cell expression in M.tb-infected CCL5 KO and WT mice. Mice were infected with 50–100 CFU M.tb Erdman by aerosol and killed at Day 14 of infection. Lung cells were fixed and labeled with anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CCR5 (A and B), and anti-CCR1 (C and D) for flow cytometry. In separate experiments, lung cells were labeled with anti-CD3, anti-CD4, and anti-CD8, permeabilized, and labeled with anti-CCR5 (E and F) and anti-CCR1 (G and H). Data are the combined average ± sem of three independent experiments (B) and two independent experiments (D, F, and H), each with four to five mice/group, analyzed by the Student’s t-test (*, P<0.05; **, P<0.01). Representative histogram plots gated on surface-stained or permeabilized and stained CD4 T cells show detection of CCR5 (B and F) or CCR1 (C and G) with corresponding isotypes.

In contrast to CCR5, the numbers of CCR1+ T cells were small and did not increase following permeabilization by two different methods or detection with different CCR1-specific antibodies (Fig. 9, C, D, G, and H). These results suggest that CCR1 was a minor contributor to early T cell migration to M.tb-infected lungs. In CCL5 KO mice, the numbers of CCR1+ T cells in the lungs were also lower than in WT mice, suggesting that additional CCR1 ligands could promote low levels of T cell migration.

Overall, together with our previous data evaluating the levels of CCL4 and CCL3, these chemokine receptor results suggest that CCR5–CCL5 interactions account for ∼50% of CD4 and CD8 T cell migration during early M.tb infection. Under normal (WT) conditions in mice, CCR5–CCL4 and CCR5–CCL3 likely account for the additional CCR5-mediated migration. In the absence of CCL5, our data suggest that CCL4, but not CCL3, provides partial compensation. Finally, CCR1 appears to contribute minimally to T cell lung migration during early M.tb infection.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, we are the first to directly determine a role for the chemokine ligand CCL5 during M.tb infection in vivo. Collectively, our data illustrate an early, protective role for CCL5 in limiting M.tb growth by recruiting IFN-γ-producing, antigen-specific T cells through CCR5 expression. CCL5 also recruited macrophages and monocytes to the lungs; however, impaired innate control of M.tb growth was not apparent in our studies. These findings are consistent with another model [51], demonstrating that persistently low numbers of lung macrophages do not impair resistance or survival of mice following low-dose M.tb aerosol infection.

In the murine model, low ccl5 gene expression in the lungs is associated with M.tb susceptibility in DBA/2 mice [20] and in CBA/J mice (our unpublished observations). In humans, polymorphisms in the ccl5 promoter region occur at significantly higher frequencies in TB patients than in healthy control subjects [30, 31], suggesting that altered ccl5 transcription likely contributes to M.tb susceptibility. Although CCL5 protein levels were not evaluated, these results associate genetic differences in ccl5 with M.tb susceptibility. They do not, however, address the immune mechanisms underlying enhanced susceptibility. Together, with our results using CCL5 KO mice, it is clear that insufficient CCL5 alone does not result in TB disease. Therefore, despite a protective role for CCL5 in early M.tb-specific immunity, granuloma formation, and M.tb control, additional genetic and/or immune mechanisms in combination with deficient ccl5 gene and/or CCL5 protein expression must influence the progression from M.tb infection to TB disease.

Previous publications have used receptor-deficient (CCR5 KO) mice [23, 29] to identify a role for CCR5 in vivo during M.tb infection and to assess indirectly the contribution of CCR5 ligands. The lack of CCR5 did not affect M.tb lung burdens or survival. The lack of CCR5 did, however, increase the numbers of lung and MLN immune cells, especially within dendritic cell and lymphocyte populations [29]. Multiple possibilities may contribute to the phenotypic differences observed between ligand (CCL5) KO and receptor (CCR5) KO mice. It may simply reflect differences in the experimental time-points investigated or result from CCR5 interactions with up to eight ligands [26], and therefore, the absence CCR5 may not be an appropriate surrogate marker to determine the function of CCL5. Alternatively, the roles of CCL5 and CCR5 may differ in their dominant in vivo functions. Our results suggest that CCL5 contributes primarily to early, protective cellular migration and M.tb granuloma formation. In contrast, the results from M.tb-infected CCR5 KO mice [29] may reflect a dominant function of CCR5 as a pattern recognition receptor for mycobacterial heat shock proteins, which promote dendritic cell-mediated immune responses [52].

Although the main function of CCR5, as suggested by its absence in CCR5 KO mice, could be to promote dendritic cell function, our results show that CCR5 also has its expected chemotactic function: to promote T cell recruitment in response to M.tb infection, a finding that has been shown in human TB patients [53,54,55,56]. In our experiments, the CCR5-related receptor, CCR1 [26, 57, 58], contributed minimally to T cell migration to the lungs during early M.tb infection. Further experiments, however, are necessary to rule out effects as a result of CCR1 or CCR5 expression by other T cell populations, such as circulating naïve or circulating memory CD4 T cell subsets [59].

In addition to CCR5, other chemokine receptors have been shown to contribute to M.tb-protective immunity. For example, CCR2 protects during high-dose [60, 61] but not during low-dose M.tb infection, despite reduced numbers of lung macrophages [51]. Thus, the protective role of CCR2 during M.tb is dose-dependent, evident only following exposure to high bacterial loads.

Chemokine ligands, in particular those inducible by IFN-γ (CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11), may also contribute to M.tb protection. All three have been detected within M.tb granulomas by in situ hybridization [62], and these chemokines recruit T cells during recall responses of TB skin test-positive healthy individuals [63]. Whether the recruited cells are truly protective, as measured by enhanced M.tb control or improved survival, is less clear, as mice treated with anti-CXCL9, as well as CXCR3 KO mice (which lack the receptor for all three chemokines), showed equivalent M.tb control and survival as WT mice, despite transiently smaller lung granulomas [64]. Thus, it appears that CXCL9–, CXCL10–, and CXCL11–CXCR3 interactions indeed promote immune cell migration to granulomas in vivo, but those cellular infiltrates may not be necessary to limit M.tb growth. Overall, these reports highlight the complexity of chemokines and chemokine receptors from multiple families in coordinating protective immune cell responses to M.tb and the difficulty in establishing clear roles for individual chemokines in vivo.

Complex roles for chemokine ligands in vivo are also seen in our results. CCL5 promoted a large proportion of early T cell migration to M.tb-infected lungs. It was apparent that additional CCL5-related ligands, such as CCL4 and CCL3, also contributed to immune cell migration, as CCL5 KO mice eventually localized protective cells to lungs, formed granulomas, and controlled M.tb infection. The roles of CCL4 and CCL3, however, were likely not redundant, as there were marked differences in the kinetics of expression and protein levels in the lungs. An early spike in CCL4 suggested that it compensated for the lack of CCL5. In contrast, CCL3 remained low when CCL5 was absent, suggesting that it was not compensatory, but rather, its production was dependent on CCL5. In conjunction with our chemokine receptor results, our findings illustrate that T cells preferentially used CCR5–CCL5 or CCR5–CCL4 interactions for early migration into M.tb-infected lungs and granuloma formation. In contrast, CCR1–CCL5, CCR1–CCL3, and CCR5–CCL3 interactions were likely less important for recruitment of protective cells during early M.tb infection and granuloma formation.

Overall, our data provide an updated model of M.tb lung granuloma formation that accounts for the temporal production of chemokines in vivo and in patterns that are not necessarily impacted by ligand redundancy and receptor promiscuity. Our results indicate that CCL5 contributes to early, protective, M.tb-specific immunity and that CCL4 but not CCL3 may compensate partially for the lack of CCL5. We also showed that T cells favor CCR5 interactions over CCR1 during early M.tb infection. If similar patterns of chemokine expression and receptor use could be identified in M.tb-infected people or in TB patients, chemokines may be targeted for TB disease stage-specific immunotherapies. For example, CCL5 supplementation could accumulate on activated endothelial cells [40, 65], promoting extravasation and migration of effector T cells into M.tb lung granulomas.

AUTHORSHIP

Bridget Vesosky provided intellectual, administrative, and technical support. Erin K. Rottinghaus contributed technical support, and Paul Stromberg contributed veterinary pathology services. Joanne Turner contributed intellectual support and mentoring. Gillian Beamer contributed intellectual and technical support.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Support was provided by the NIH R01 (AI064522; J. T.), NIH T32 (RR07073; G. B.), NIH K08 (AI071111; G. B.), and the PEO International Scholar Award (G. B.). Manuscript contents are the authors’ responsibilities and do not necessarily represent the views of the NIH or PEO. Colorado State University’s TB Vaccine Testing and Research Material Contract number HH5N266200400091c NIH N01AI40091 generously provided M.tb CFP and the recombinant plasmid pMRLB7 containing Rv3875 (esat-6). ESAT-6 was expressed in Eschierichia coli and isolated as per the contract’s recommendations. The Ohio State University’s Department of Veterinary Biosciences Histotechnology Services performed routine histology and CD4 and CD8 immunohistochemistry services.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CFP=culture filtrate protein, ESAT-6=early secreted antigenic target-6, KO=knockout, MLN=mediastinal lymph node, M.tb=Mycobacterium tuberculosis, NIH=National Institutes of Health, PEO=Philanthropic Educational Organization, PI=propidium iodide, SFU=spot-forming unit, TB=tuberculosis, WT=wild-type

The online version of this paper, found at www.jleukbio.org, includes supplemental material.

References

- Cooper A, Roberts A, Rhoades E, Callahan J, Getzy D, Orme I M. The role of interleukin-12 in acquired immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Immunology. 1995;84:423–432. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn J L, Goldstein M, Chan J, Triebold K, Pfeffer K, Lowenstein C. Tumor necrosis factor-α is required in the protective immune response against M. tuberculosis in mice. Immunity. 1995;2:561–572. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper A, Dalton D, Stewart T, Griffin J, Russell D, Orme I. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon-γ gene-disrupted mice. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2243–2247. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J, Xing Y, Magliozzo R, Bloom B. Killing of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis by reactive nitrogen intermediates produced by activated murine macrophages. J Exp Med. 1992;175:1111–1122. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.4.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dungworth D. The respiratory system. Jubb K, Kennedy P, Palmer N, editors. San Diego, CA, USA: Academic; 1993:641–652. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders B M, Cooper A. Restraining mycobacteria: role of granulomas in mycobacterial infections. Immunol Cell Biol. 2000;78:334–341. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2000.00933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders B M, Frank A A, Orme I M. Granuloma formation is required to contain bacillus growth and delay mortality in mice chronically infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Immunology. 1999;98:324–328. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00877.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers S. Lazy, dynamic or minimally recrudescent? On the elusive nature and location of the mycobacterium responsible for latent tuberculosis. Infection. 2009;37:87–95. doi: 10.1007/s15010-009-8450-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter R L, Jagannath C, Actor J K. Pathology of postprimary tuberculosis in humans and mice: contradiction of long-held beliefs. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2007;87:267–278. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North R J, Jung Y-J. Immunity to tuberculosis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:599–623. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona P-J, Gordillo S, Diaz J, Ojanguren I, Ariza A, Ausina V. Evolution of granulomas in lungs of mice aerogenically infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Scand J Immunol. 2000;52:156–163. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2000.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitch A. Tuberculosis: pathogenesis, epidemiology and prevention. Seaton A, Seaton D, Leitch A, editors. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science Ltd.; 2000:476–506. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas S B. Histopathology. Davies P, editor. London, UK: Chapman & Hall, Lippincott-Raven; Clinical Tuberculosis. 2003:113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers S. Why does tumor necrosis factor targeted therapy reactivate tuberculosis? J Rheumatol. 2005;74:35–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrichs T, Kosmiadi G A, Jorg S, Pradl L, Titukhina M, Mischenko V, Gushina N, Kaufmann S H. Differential organization of the local immune response in patients with active cavitary tuberculosis or with nonprogressive tuberculoma. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:89–97. doi: 10.1086/430621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner J, Gonzalez-Juarrero M, Saunders B M, Brooks J V, Marietta P, Ellis D L, Frank A A, Orme I M. Immunological basis for reactivation of tuberculosis in mice. Infect Immun. 2001;69:3264–3270. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3264-3270.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beamer G L, Flaherty D K, Vesosky B, Turner J. Peripheral blood interferon-{γ} release assays predict lung responses and Mycobacterium tuberculosis disease outcome in mice. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:474–483. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00408-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammas D, De Heer E, Edgar J, Novelli V, Ben-Smith A, Baretto R, Drysdale P, Binch J, MacLennan C, Kumararatne D S, Panchalingham S, Ottenhoff T, Casanova J-L, Emile J-F. Heterogeneity in the granulomatous response to mycobacterial infection in patients with defined genetic mutations on the interleukin 12-dependent interferon-γ production pathway. Int J Exp Pathol. 2002;83:1–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.2002.00216.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawn S D, Butera S T, Shinnick T M. Tuberculosis unleashed: the impact of human immunodeficiency virus infection on the host immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbes Infect. 2002;4:635–646. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01582-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona P-J, Gordillo S, Diaz J, Tapia G, Amat I, Pallares A, Vilaplana C, Ariza A, Ausina V. Widespread bronchogenic dissemination makes DBA/2 mice more susceptible than C57BL/6 mice to experimental aerosol infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5845–5854. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5845-5854.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina E, North R. Evidence inconsistent with a role for the Bcg gene (Nramp1) in resistance of mice to infection with virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1045–1051. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner O C, Keefe R, Sugawara I, Yamanda H, Orme I M. SWR mice are highly susceptible to pulmonary infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5266–5277. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.9.5266-5272.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badewa A, Quinton L, Shellito J, Mason C. Chemokine receptor 5 and its ligands in the immune response to murine tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2005;85:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedla N, Palladinetti P, Wakefield D, Lloyd A. Abundant expression of chemokines in malignant and infective human lymphadenopathies. Cytokine. 1999;11:531–540. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1998.0439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadek M I, Sada E, Toossi Z, Schwander S K, Rich E A. Chemokines induced by infection of mononuclear phagocytes with mycobacteria and present in lung alveoli during active pulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;19:513–521. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.19.3.2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rot A, von Andrian U H. Chemokines in innate and adaptive host defense: basic chemokinese grammar for immune cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:891–928. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chensue S W, Warmington K S, Allenspach E J, Lu B, Gerard C, Kunkel S L, Lukacs N W. Differential expression and cross-regulatory function of RANTES during mycobacterial (type 1) and schistosomal (type 2) antigen-elicited granulomatous inflammation. J Immunol. 1999;163:165–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Jackson Laboratory (2009, posting date) Strain information, http://jaxmice.jax.org/strain/005090.html [Google Scholar]

- Algood H M S, Flynn J L. CCR5-deficient mice control Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection despite increased pulmonary lymphocytic infiltration. J Immunol. 2004;173:3287–3296. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu S-F, Tam C M, Wong H S, Kam K M, Lau Y L, Chiang A K S. Association between RANTES functional polymorphisms and tuberculosis in Hong Kong Chinese. Genes Immun. 2007;8:475–479. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Castañón M, Baquero I, Sánchez-Velasco P, Fariñas M, Ausín F, Leyva-Cobián F, Ocejo-Vinyals J. Polymorphisms in CCL5 promoter are associated with pulmonary tuberculosis in Northern Spain. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13:480–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino Y, Cook D, Smithies O, Hwang O, Nielson E G, Turka L, Sato H, Wells A, Danoff T. Impaired T cell function in RANTES deficient mice. Clin Immunol. 2002;102:302–309. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Juarrero M, Shim T S, Kipnis A, Junqueira-Kipnis A P, Orme I M. Dynamics of macrophage cell populations during murine pulmonary tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2003;171:3128–3135. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.3128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn J L, Chan J, Triebold K, Dalton D, Stewart T, Bloom B. An essential role for interferon-γ in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2249–2254. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai M, Zwerling A, Menzies D. Systematic review: T-cell-based assays for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: an update. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:177–184. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-3-200808050-00241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper A M. Cell-mediated immune responses in tuberculosis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:393–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggiolini M. Chemokines in pathology and medicine. J Intern Med. 2001;250:91–104. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabot V, Reverdiau P, Iochmann S, Rico A, Senecal D, Goupille C, Sizaret P-Y, Sensebe L. CCL5-enhanced human immature dendritic cell migration through the basement membrane in vitro depends on matrix metalloproteinase-9. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:767–778. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0804464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman R, Pack M, Inaba K. Dendritic cells in the T-cell areas of lymphoid organs. Immunol Rev. 1997;156:25–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen S J, Crown S E, Handel T M. Chemokine receptor structure, interactions, and antagonism. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:787–820. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonecchi R, Bianchi G, Bordignon P P, D'Ambrosio D, Lang R, Borsatti A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Gray P A, Mantovani A, Sinigaglia F. Differential expression of chemokine receptors and chemotactic responsiveness of type 1 T helper cells (Th1s) and Th2s. J Exp Med. 1998;187:129–134. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppermann M. Chemokine receptor CCR5: insights into structure, function, and regulation. Cell Signal. 2004;16:1201–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A, Mackay C. Chemokines and chemokine receptors in T cell priming and TH1/TH2-mediated responses. Immunol Today. 1998;19:568–574. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01346-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demissie A, Abebe M, Aseffa A, Rook G, Fletcher H, Zumla A, Weldingh K, Brock I, Andersen P, Doherty T M. Healthy individuals that control a latent infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis express high levels of Th1 cytokines and the IL-4 antagonist IL-4{δ}2. J Immunol. 2004;172:6938–6943. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn J L, Chan J. Immunology of tuberculosis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:93–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lienhardt C, Azzurri A, Amedei A, Fielding K, Sillah J, Sow O Y, Bah B, Benagiano M, Diallo A, Manetti R, Manneh K, Gustafson P, Bennett S, D'Elios M M, McAdam K, Prete G D. Active tuberculosis in Africa is associated with reduced Th1 and increased Th2 activity in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:1605–1613. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200206)32:6<1605::AID-IMMU1605>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan B M, Jobe O, Lazarevic V, Vasquez K, Bronson R, Glimcher L H, Kramnik I. Increased susceptibility of mice lacking T-bet to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis correlates with increased IL-10 and decreased IFN-{γ} production. J Immunol. 2005;175:4593–4602. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesosky B, Flaherty D K, Turner J. Th1 cytokines facilitate CD8-T-cell-mediated early resistance to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis in old mice. Infect Immun. 2006;74:3314–3324. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01475-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer M, von Stebut E. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1882–1886. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olbrich H, Proudfoot A, Oppermann M. Chemokine-induced phosphorylation of CC chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) J Leukoc Biol. 1999;65:281–285. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott H M, Flynn J L. Mycobacterium tuberculosis in chemokine receptor 2-deficient mice: influence of dose on disease progression. Infect Immun. 2002;70:5946–5954. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.11.5946-5954.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floto R A, MacAry P A, Boname J M, Mien T S, Kampmann B, Hair J R, Huey O S, Houben E N G, Pieters J, Day C, Oehlmann W, Singh M, Smith K G C, Lehner P J. Dendritic cell stimulation by mycobacterial hsp70 is mediated through CCR5. Science. 2006;314:454–458. doi: 10.1126/science.1133515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrero E, Biswas P, Vettoretto K, Ferrarini M, Uguccioni M, Piali L, Leone B E, Moser B, Rugarli C. Macrophages exposed to Mycobacterium tuberculosis release chemokines able to recruit selected leukocyte subpopulations: focus on γ-δ T-cells. Immunology. 2003;108:365–374. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2003.01600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayanja-Kizza H, Wajja A, Wu M, Peters P, Nalugwa G, Mubiru F, Aung H, Vanham G, Hirsch C S, Whalen C, Ellner J J, Toossi Z. Activation of β-chemokines and CCR5 in persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1801–1804. doi: 10.1086/320724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra D, Sharma S, Dinda A, Bindra M, Mandan B, Ghosh B. Polarized helper T cells in tubercular pleural effusion: phenotypic identity and selective recruitment. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2367–2375. doi: 10.1002/eji.200525977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokkali S, Das S D. Augmented chemokine levels and chemokine receptor expression on immune cells during pulmonary tuberculosis. Hum Immunol. 2009;70:110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combadiere C, Ahuja S, Tiffany H, Murphy P. Cloning and functional expression of CC CKR5, a human monocyte CC chemokine receptor selective for MIP-1(α), MIP-1(β), and RANTES. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;60:147–152. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.1.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raport C J, Gosling J, Schweickart V L, Gray P W, Charo I F. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of a novel human CC chemokine receptor (CCR5) for RANTES, MIP-1β, and MIP-1α. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17161–17166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Kawasaki H, Morimoto C, Yamashima N, Matsuyama T. An abortive ligand-induced activation of CCR1-mediated downstream signaling event and a deficiency of CCR5 expression are associated with the hyporesponsiveness of human naive CD4+ T cells to CCL3 and CCL5. J Immunol. 2002;168:6263–6272. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters W, Cyster J G, Mack M, Schlondorff D, Wolf A J, Ernst J D, Charo I F. CCR2-dependent trafficking of F4/80 dim macrophages and CD11c dim/intermediate dendritic cells is crucial for T cell recruitment to lungs infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2004;172:7647–7653. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters W, Scott H M, Chambers H F, Flynn J L, Charo I F, Ernst J D. Chemokine receptor 2 serves an early and essential role in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:7958–7963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131207398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller C, Flynn J, Reinhart T. In situ study of abundant expression of proinflammatory chemokines and cytokines in pulmonary granulomas that develop in cynomologous macaques experimentally infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2003;71:7023–7034. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.12.7023-7034.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walrath J, Zukowski L, Krywiak A, Silver R F. Resident Th1-like effector memory cells in pulmonary recall responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;33:48–55. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0060OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler P, Alchele P, Bandermann S, Hauser A, Lu B, Gerard N, Gerard C, Ehlers S, Mollenkopf H, Kaufmann S. Early granuloma formation after aerosol Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection is regulated by neutrophils via CXCR3-signaling chemokines. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2676–2686. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schober A. Chemokines in vascular dysfunction and remodeling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1950–1959. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.161224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.