Abstract

The fourth lysine of histone H3 is post-translationally modified by methyl group via the action of histone methyltransferase, and such a covalent modification is associated with transcriptionally active and/or repressed chromatin states. Thus, histone H3 lysine 4 methylation plays crucial roles in maintaining normal cellular functions. In fact, misregulation of this covalent modification has been implicated in various types of cancers and other diseases. Therefore, a large number of studies over recent years have been directed towards histone H3 lysine 4 methylation and the enzymes involved in this covalent modification in eukaryotes ranging from yeast to human. These studies revealed a set of histone H3 lysine 4 methyltransferases with important cellular functions in different eukaryotes as discussed here

Keywords: Histone methyltransferase, Histone H3 lysine 4, Set1, COMPASS, MLL

Introduction

The DNA in eukaryotes is compacted in the form of chromatin. The fundamental unit of chromatin is the nucleosome which consists of a core histone particle wrapped around by 146 bp of DNA [1, 2]. The core histone particle comprises of a tetramer of histones H3 and H4 and dimers of histones H2A and H2B [2]. Each of these histones has a structured core globular domain and an unstructured flexible N- terminal tail protruding out from the core domain. The linker histone H1 associates with the core domain to form higher order structure, thus further compacting the DNA [3, 4]. Such compaction of DNA in higher order chromatin structure makes it inaccessible for proteins involved in different DNA transacting processes such transcription, replication, recombination and DNA repair. However, the chromatin structure is dynamic in nature in order for DNA transacting processes to occur [5-10], and such dynamic states are regulated by ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers as well as ATP-independent histone covalent modifications.

There are several ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers. These include the SWI/SNF (switching–defective/sucrose non-fermenting), ISW1 (imitation switch), Mi-2/NuRD (nucleosome remodeling and histone deacetylation), and INO80 complexes [11-25]. These complexes have a catalytic ATPase subunit with a DNA-dependent ATPase activity. The ATP-independent histone covalent modifications are acetylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitylation, methylation, sumoylation and ADP ribosylation [8, 10, 26-33]. Though most of these modifications occur on the N-terminal tails of histones, some of them also occur on C-terminal tails of histones H2A and H2B [29, 30, 34], and core region of histone H3 [30, 31, 35, 36]. These covalent modifications have profound effects on chromatin structure and hence gene regulation [5, 8, 9, 30, 33].

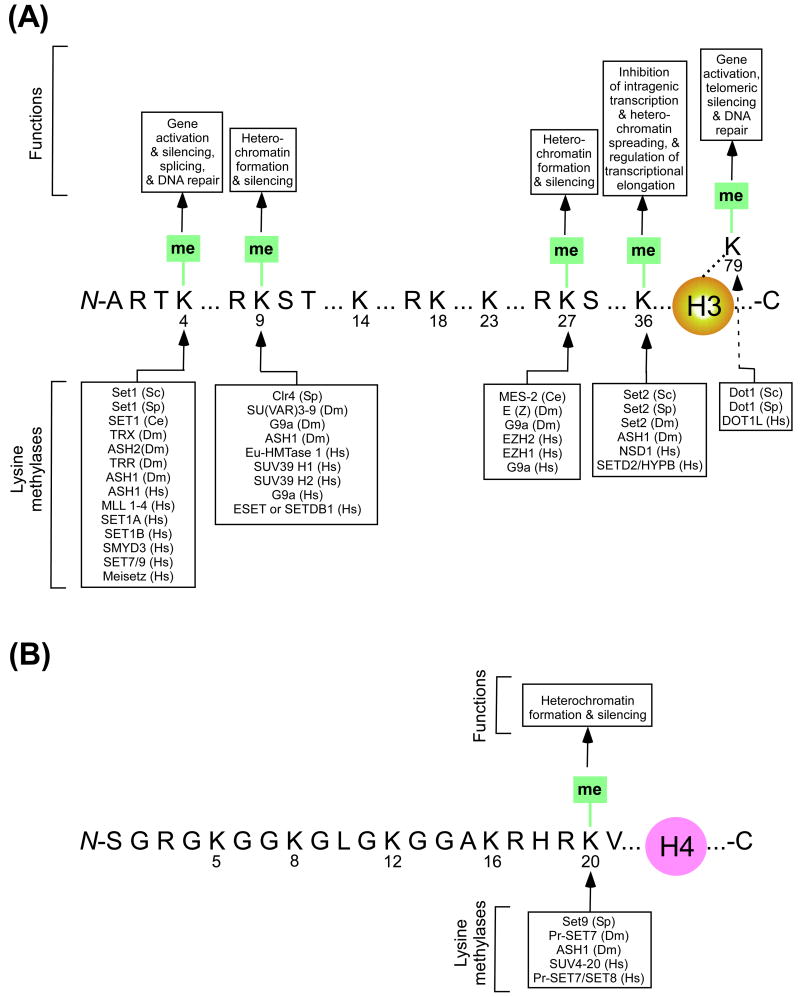

The lysine (K) residues of histones H3 and H4 can be mono-, di-, and trimethylated, and such methylation is associated with active and/or repressed chromatin (Figure 1). Thus, histone methylation is linked to diverse cellular regulatory functions [27, 30, 31, 33]. Indeed, a variety of studies have implicated histone methylation in various types of cancers and other diseases [30, 33, 37-39]. Therefore, a large number of studies over several years have been focused on histone methylation of different K residues and the enzymes involved in this covalent modification in diverse eukaryotes [27, 30, 31, 33, 40-45]. These studies have revealed several histone methyltransferases (HMTs) involved in K methylation of histones H3 and H4 with their crucial roles to maintain normal cellular functions in eukaryotes ranging from yeast to human (Figure 1). Here, we discuss histone H3 K4 methylation and the HMTs involved in this covalent modification with similarities and differences in several eukaryotes such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae (budding yeast), Schizosaccharomyces pombe (fission yeast), Caenorhabditis elegans (worm), Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly), Mus musculus (mouse), and Homo sapiens (human).

Figure 1.

Methylation of different lysine (K) residues of histones H3 (A) and H4 (B) with associated methylases and functions in genome expression and integrity. Sc, Saccharomyces cerevisiae; Sp, Schizosaccharomyces pombe; Ce, Caenorhabditis elegans; Dm, Drosophila melanogaster; and Hs, Homo sapiens.

Histone H3 K4 methylation and HMTs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S. cerevisiae), histone H3 K4 methylation is involved in stimulation of transcription [29-31, 33]. Further, histone H3 K4 methylation in S. cerevisiae has been implicated in silencing at telomeres, ribosomal DNA and mating type locus [30, 33, 46, 47]. Thus, histone H3 K4 methylation participates in both gene activation and repression. The enzyme responsible for this covalent modification was first identified in a multiprotein complex, named as COMPASS (complex proteins associated with Set1), in S. cerevisiae [48]. The COMPASS consists of the catalytic subunit, Set1, and seven other proteins (Cps60/Bre2, Cps50/Swd1, Cps40/Spp1, Cps35/Swd2, Cps30/Swd3, Cps25/Sdc1 and Cps15/Shg1) (Tables 1-3) [29, 33, 48, 49]. Set1 is essential for mono-, di-, and trimethylation of histone H3 at K4 [29, 30, 33, 48, 49]. Set1 is enzymatically active only when it is assembled into the multisubunit COMPASS complex. The ability of COMPASS to mono-, di- and trimethylate K4 of histone H3 depends on its subunit composition. For example, COMPASS lacking Cps60/Bre2 cannot trimethylate K4 of histone H3 while the Cps25 subunit of COMPASS is essential for histone H3 K4 di- and trimethylation [29, 33, 49, 50]. The COMPASS complex preferentially associates with RNA Polymerase II that is phosphorylated at serine 5 in its C-terminal domain at the onset of transcriptional elongation [33, 49, 51-54]. The interaction between COMPASS and RNA polymerase II is further facilitated by the Paf1 (RNA polymerase II-associated factor 1) complex that associates with the coding sequence in an RNA polymerase II-dependent manner during transcriptional elongation [33, 49, 51-54]. Thus, COMPASS is found to be predominantly associated with the coding sequences of active genes [33, 49, 51, 54, 55], and hence, the coding sequences of the actively transcribing genes are tri-methylated at K4 of histone H3 [33, 51, 54-58].

Table 1.

The histone H3 K4 methyltransferases in different eukaryotes (references are cited in the text).

| S. cerevisiae | S. pombe | C. elegans | Drosophila | Mammals (Mouse and Human) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMPASS/Set1C | Set1C | COMPASS-like complex | TAC1 | MLL1 |

| ASH1 | MLL2 | |||

| ASH2 | MLL3 | |||

| TRR | MLL4 | |||

| SET1A | ||||

| SET1B | ||||

| SET7/9 | ||||

| SMYD3 | ||||

| ASH1 | ||||

| Meisetz | ||||

Table 3.

Homologous subunits of histone H3 K4 methyltransferase complexes in different eukaryotes (references are cited in the text).

| S.cerevisiae | S. pombe | C. elegans | Drosophila | Mammals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Set1 | Set1 | SET-2/SET1 | TRX | MLL1-4, SET1A/SET1B |

| Cps60 /Bre2 | Ash2 | ASH-2 | ASH2 | ASH2L/ASH2 |

| Cps50 /Swd1 | Swd1 | CFPL-1 | RBBP5 | |

| Cps30/ Swd3 | Swd3 | SWD-3 | WDR5 | WDR5 |

| Cps35/ Swd2 | Swd2 | SWD-2 | WDR82/SWD2 | |

| Cps40/Spp1 | Spp1 | SPP-1 | CFP1 | |

| Cps25 /Sdc1 | Sdc1 | DPY-30 | DPY-30 | |

| Cps15 /Shg1 | Shg1 | |||

| ASH1 | ASH1L/ASH1 | |||

| TRR | ||||

| Menin | ||||

| HCF1/HCF2 | ||||

| NCOA6 | ||||

| PA1 | ||||

| PTIP | ||||

| UTX | ||||

| MOF | ||||

| SET7/9 | ||||

| SMYD3 | ||||

| Meisetz |

Interestingly, the methyltransferase activity of the COMPASS complex is intimately regulated by ubiquitylation of histone H2B at K123 [30, 33, 59-63]. Both di- and trimethylation of histone H3 at K4 are impaired in the absence of histone H2B K123 ubiquitylation that is catalyzed by E2 ubiquitin conjugase and E3 ubiquitin ligase, Rad26 and Bre1, respectively. However, histone H2B K123 ubiquitylation does not regulate histone H3 K4 monomethylation [33, 62, 64]. Such a trans-tail cross-talk between histone H2B K123 ubiquitylation and histone H3 K4 di- and trimethylation is mediated via the alteration of the subunit composition of COMPASS [33, 55]. It was recently demonstrated that histone H2B K123 ubiquitylation is essential for the recruitment of Cps35/Swd2 independently of Set1 [33, 55]. Set1 maintains the structural integrity of the COMPASS complex [33, 55]. Consistently, COMPASS without Cps35/Swd2 is recruited to the coding sequence of the active gene in an RNA polymerase II-dependent manner in the absence of histone H2B K123 ubiquitylation [33, 55]. Such COMPASS without Cps35/Swd2 only monomethylates K4 of histone H3, but does not have catalytic activity for di- and trimethylation of histone H3 at K4 [33, 55]. When histone H2B is ubiquitylated by the combined actions of Rad26 and Bre1, it recruits Cps35/Swd2 which interacts with the rest of COMPASS that is recruited by elongating RNA polymerase II. Such an interaction leads to the formation of a fully active COMPASS capable of histone H3 K4 mono-, di- and trimethylation [33, 55]. Thus, histone H3 K4 methylation is regulated by the upstream factors that are involved in histone H2B K123 ubiquitylation. Further, histone H3 K4 methylation is controlled by a demethylase with the Jumonji C (JmjC) domain, namely Jhd2, which specifically demethylates the trimethylated-K4 of histone H3 (Table 4) [65]. Such demethylation provides an additional level of regulation of histone H3 K4 methylation in S. cerevisae.

Table 4.

Histone H3 K4 demethylases in different eukaryotes (references are cited in the text).

| S. cerevisae | S. pombe | C. elegans | Drosophila | Mammals (Mouse and Human) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jhd2 (me3) | Swm1 (me2) | SPR-5 (me2) | Lid (me3) | LSD1 (me2/1) |

| Swm2 (me2) | T08D10.2 (me2) | JARID1A (me3/2) | ||

| R13G10.2 (me2) | ||||

| JARID1B (me3/2) | ||||

| JARID1C (me3/2) | ||||

| JARID1D (me3/2) | ||||

Abbreviations: me3, trimethyl; me2, dimethyl; me3/2, tri- and dimethyl; and me2/1, di- and monomethyl.

Histone H3 K4 methylation and HMTs in Schizosaccharomyces pombe

Although the first histone H3 K4 methyltransferase was identified in S. cerevisiae, the chromatin structure in S. cerevisiae is not similar to that of Schizosaccharomyces pombe (S. pombe) or higher eukaryotes. For example, S. cerevisiae lacks homologs of the repressive H3 K9 methyltransferases and the heterochromatin proteins (e.g., HP1) that are present in S. pombe or higher eukaryotes [66-68]. Thus, S. pombe serves as a better model eukaryotic system to study the roles of histone H3 K4 methylation in regulation of chromatin structure and gene expression. Like in S. cerevisae, histone H3 K4 methylation in S. pombe is catalyzed by a SET [Su(var)3-9, Enhancer-of-zeste, Trithorax] domain-containing protein, Set1. The S. pombe Set1 protein is homologous to S. cerevisiae Set1. The Set1 proteins in budding and fission yeasts share a high degree of similarity in their SET domains. However, these two proteins exhibit overall 26% sequence identity [69]. The N-termini of Set1 in S. cerevisae and S. pombe are considerably different [69-71]. Such difference might be playing crucial roles in governing the specific functions of Set1 in S. cerevisae and S. pombe. For example, a recombinant S. pombe Set1 methylates K4 in a 20 amino acid long peptide corresponding to the N-terminal tail of histone H3 in vitro. In contrast, the recombinant S. cerevisae Set1 does not have methyltransferase activity in vitro. Further, the phylogenetic analysis indicates that S. pombe Set1 is more closely related to human Set1 than to S. cerevisae Set1 [69]. S. pombe Set1 mutants have slow growth, exhibit temperature sensitive growth defects and have slightly longer doubling time as compared to wild type cells [69].

DNA sequence analysis reveals that the homologs of the components of S. cerevisae COMPASS are also present in S. pombe. Indeed, Set1 methyltransferase complex (Set1C) has been purified in S. pombe, which shares many features of S. cerevisae COMPASS (Tables 1-3). However, these two complexes differ in several ways. For example, Ash2 component of Set1C in S. pombe has a PHD (plant homeodomain) finger domain, while the homologous protein, Cps60/Bre2 (Table 3), in S. cerevisae does not have this domain [70]. The Cps40/Spp1 component (that bears the PHD finger domain) is required for methylation in S. pombe, but not in S. cerevisae [70]. Furthermore, Set1C in S. pombe shows hyperlink to Lid2C (little imaginal discs 2 complex) through Ash2 and Sdc1 [70]. However, such a hyperlink is absent in S. cerevisae. In addition, the identified hyperlink, Swd2 (which is also a subunit of the cleavage and polyadenylation factor), in S. cerevisae COMPASS is not found in S. pombe [70-72]. Together, these observations support the fact that the Set1 HMTs from S. cerevisae and S. pombe are highly conserved (Tables 1-3), but their proteomic environments appear to differ. However, such differences in the proteomic environments may be related to the absence of histone H3 K9 methylation in S. cerevisae as suggested previously [70].

Histone H3 K4 methylation is correlated with active chromatin in S. pombe [69] as in S. cerevisae. However, unlike in S. cerevisiae, histone H3 K4 methylation is not required for silencing and heterochromatin assembly at the centromeres and mating type locus in S. pombe [69], possibly due to the presence of repressive H3 K9 methylation in S. pombe [69]. Furthermore, previous studies [69] have demonstrated that histone H3 K4 methylation is correlated with histone H3 acetylation in S. pombe, and hence, is associated with active genes. However, transcriptional stimulation by histone H3 K4 methylation is also closely regulated by histone demethylase, LSD1, which is absent in S. cerevisae. LSD1 is an amine oxidase which demethylates K residue in a flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-dependent manner. Since it functions through oxidation, it can only demethylate mono- and dimethylated-K4 of histone H3. There are two LSD1-like proteins, namely Swm1 and Swm2 (after SWIRM1 and SWIRM2), in S. pombe (Table 4) [73, 74]. These two proteins form a complex, and are involved in demethylation of methylated-K4 and K9 of histone H3. Such demethylation process plays important roles in the regulation of chromatin structure and hence gene expression.

Histone H3 K4 methylation and HMTs in Caenorhabditis elegans

Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) is a multicellular, yet simple, eukaryotic system with technical advantages to study chromatin structure in greater detail. Thus, C. elegans can serve as a model system to understand the role of histone covalent modifications in developmental processes. Like in S. cerevisae and S. pombe, histone H3 K4 methylation plays an important role to promote transcription in C. elegans [75]. However, the early C. elegans embryos have a transcriptionally repressed chromatin state, even though both di- and trimethylation of histone H3 at K4 are present in the chromatin of the germline blastomere [75]. Such repression is perhaps resulted from the lack of serine-2 phosphorylation in the C-terminal domain of the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II in the germline cells [76]. Following division of the germline lineage P4 cells into the primordial germ cells, histone H3 K4 methylation is lost [75]. However, histone H3 K4 methylation is regained prior to post embryonic proliferation. Such covalent modification activates gene expression in the post embryonic germ cells [75, 77].

The enzyme involved in histone H3 K4 methylation in C. elegans was identified recently via RNAi screen of the suppressors of heterochromatin protein mutants (hpl-1 and hpl-2). The RNAi screen identified set-2 as the homologue of yeast SET1 [78]. Further, several studies have revealed that SET-2 (also known as SET-2/SET1) forms a complex with SWD-3, CFPL-1, DPY-30, Y17G7B.2/ASH-2, C33H5.6/WDR82/SWD-2, F52B11.1/SPP-1 (Tables 1 and 2) [78]. These proteins are homologous to the budding yeast COMPASS (Table 3). Thus, like in S. cerevisae, SET-2/SET1 in C. elegans forms a COMPASS-like complex. Furthermore, like in fission yeast, SET-2/SET1 may be hyperlinked to the complex that is homologus to S. pombe's Lid2C containing Sdc1. In support of this notion, DPY-30 in C. elegans was found to be the homolog of fission yeast Sdc1 (Table 3), and it plays an important role in dosage compensation [79]. Thus, it is likely that SET-2/SET1 in C. elegans is connected to another complex via DPY-30, which remains to be elucidated.

Table 2.

The components of characterized histone H3 K4 methyltransferase complexes in different eukaryotes (references are cited in the text).

| S. cerevisae | S. pombe | C. elegans | Drosophila | Mammals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMPASS/Set1C | Set1C | COMPASS-like complex | TAC1 | MLL1 |

| Set1 | Set1 | TRX | MLL1 | |

| Cps60/Bre2 | Ash2 | SET-2/SET1 | CBP | ASH2L |

| Cps50/Swd1 | Swd1 | ASH2/Y17G7B.2 | SBF1 | WDR5 |

| Cps40/Spp1 | Spp1 | CFPL-1 | RBBP5 | |

| Cps35/Swd2 | Swd2 | SWD-3 | ASH1 | DPY-30 |

| Cps30/Swd3 | Swd3 | SWD-2/C33H5.6 | ASH1 | HCF1/HCF2 |

| Cps25/Sdc1 | Sdc1 | SPP-1/F52B11.1 | ? | Menin |

| Cps15/Shg1 | Shg1 | DPY-30 | MOF | |

| ASH2 | ||||

| ASH2 | MLL2 | |||

| ? | MLL1 | |||

| ASH2L | ||||

| TRR | WDR5 | |||

| TRR | RBBP5 | |||

| ? | DPY-30 | |||

| Menin | ||||

| HCF2 | ||||

| RPB2 | ||||

| MLL3/MLL4 | ||||

| MLL3/MLL4 | ||||

| ASH2L | ||||

| WDR5 | ||||

| RBBP5 | ||||

| DPY-30 | ||||

| NCOA6 | ||||

| PA1 | ||||

| PTIP | ||||

| UTX | ||||

| SET1A/SET1B | ||||

| SET1A/SET1B | ||||

| ASH2L | ||||

| WDR5 | ||||

| RBBP5 | ||||

| WDR82/SWD2* | ||||

| CFP1/CGBP* | ||||

| DPY-30 | ||||

| HCF1 | ||||

Like in yeast, the subunits of the COMPASS-like complex in C. elegans differentially regulate global histone H3 K4 methylation [78]. For example, no decrease in the global level of histone H3 K4 methylation was observed upon RNAi-based depletion of swd-2 [78]. A moderate decrease in histone H3 K4 methylation was observed in the absence of Y17G7B.2/ASH-2. Depletion of set-2, swd-3, cfpl-1, and dpy-30 led to a drastic decrease of global histone H3 K4 methylation with the most severe defect observed in swd-3 mutants. However, unlike in yeast, the residual level of global histone H3 K4 methylation was observed in the absence of SET-2/SET1 activity [78]. This observation suggests that additional histone H3 K4 methyltransferase(s) may exist in C. elegans.

Although histone H3 K4 methylation is associated with active transcription in C. elegans, it is reset during gametogenesis. A demethylase, SPR-5, has been recently identified in C. elgans, and it shows 45% similarity with human LSD1 [80]. SPR-5 is responsible for demethylation of dimethylated-K4 of histone H3 (Table 4). It interacts with the CoREST ([co]repressor for element-1-silencing transcription factor) repressor protein, SPR-1 [81-83]. Such an interaction is correlated with the repressive role of SPR-5 in gene regulation. Like SPR-5, two other proteins in C. elegans, namely T08D10.2 and R13G10.2, have LSD1-like amine oxidase domain as revealed by NCBI Conserved Domain Search Program (Table 4) [84]. The knockdown of T08D10.2 by RNAi extends the longevity, thus implicating the role of histone methyaltion in regulation of aging [85].

Although the studies in C. elegans have been quite helpful in understanding the role of histone H3 K4 methylation in gene expression and development, the pattern of cell lineage in C. elegans is highly invariant [86]. However, the development of embryos of Drosophila and mammals largely relies on cellular cues, thus making it a more complex process. Therefore, the studies in Drosophila will provide a better understanding of the regulatory roles of histone H3 K4 methylation in gene expression and development.

Histone H3 K4 methylation and HMTs in Drosophila

Drosophila has been for long a model organism for studying developmental processes, since development in human and Drosophila are homologous processes. Drosophila and human share a number of related developmental genes working in conserved pathways. Studies analyzing the interplay of the SET domain-containing trithorax group (trxG) and polycomb group (PcG) proteins in regulating transcription patterns during development and differentiation have been an area of extensive research in Drosophila [87-91]. The PcG and trxG proteins play a crucial role in epigenetic control of a large number of developmental genes including the Hox (Homeotic) genes [92-99]. The Hox genes are a cluster of genes that defines the anterior-posterior axis as well as segment identity during early embryogenesis. The expression pattern of the Hox genes is established early in development, and propagated in appropriate cell lineages [100]. However, the transcription of the Hox genes is closely regulated by antagonistic actions of the PcG and trxG proteins through different patterns of histone methylation. The PcG protein, E(Z), methylates histone H3 at K27 [100]. Further, histone H3 methylated at K27 is recognized by a chromodomain-containing PcG protein, PC [100]. These events repress the Hox genes and other target genes. On the other hand, the trxG proteins such as TRX (trithorax) and ASH1 (absent, small or homeotic discs 1) are histone H3 K4 methyltransferases which promote transcription of the target genes including Hox [100]. Thus, a close interplay between the specific PcG and trxG proteins maintains a tight regulation of Hox gene expression. Consistently, genetic studies in Drosophila have revealed that mutations in specific PcG and trxG genes result in flies with homeotic transformations due to misregualtion of the Hox genes [100-103].

As mentioned above, TRX is a member of the trxG proteins with histone H3 K4 methyltransferase activity in Drosophila, and it contains the SET and PHD finger domains. TRX is the homolog of yeast Set1 in Drosophila, and is an integral component of a 1 MDa complex, called TAC1 (trithorax acetylation complex 1). TAC1 consists of TRX, CBP (CREB-binding protein) and an anti-phosphatase SBF1 (Tables 2 and 3) [104]. Like mammalian CBP, Drosophila CBP has histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity [104]. Thus, TAC1 possesses both HMT and HAT activities [94, 104] which are associated with active transcription. The components of TAC1 are found to be associated with specific sites on salivary gland polytene chromosomes including Hox genes [104], and thus, exist together in vivo. The mutations in either trx or the gene encoding CBP reduce the expression of a Hox gene, namely Ubx (Ultrabithorax) [104]. Thus, the two different enzymatic activities of TAC1 are closely linked to Hox gene expression [104]. Moreover, the HAT activity of TAC1 may be counteracted by the deacetylase activity of the PcG complex, ESC/E(Z), thus accounting in part for antagonistic functions of the trxG and PcG protein-complexes on chromatin. Unlike its role in the regulation of Hox gene expression, TAC1 also promotes transcription of heat shock genes in a different mechanism through activation of poised or stalled RNA polymerase II. Heat shock genes are rapidly expressed by HSF (heat shock factor) and other transcription factors [94, 105]. TAC1 is recruited to several heat shock gene loci following heat induction, and consequently, its components are required for heat shock gene expression [94, 105]. Smith and colleagues [94] demonstrate that TAC1 associates with transcription-competent stalled RNA polymerase II at the heat shock gene, and subsequently, modifies histone H3 by methylation and acetylation. Such modifications of histone H3 facilitate stalled RNA polymerase II to begin transcriptional elongation [94, 105]. In contrast to the results at heat shock genes, poised or stalled RNA polymerase II is not found at the Hox genes [94, 105]. Thus, TAC1 appears to regulate transcription of the Hox and heat shock genes in distinct pathways.

In addition to TRX, two other trxG proteins, namely ASH1 and ASH2, methylate K4 of histone H3 [106-110]. Mutations in the Ash1 and Ash2 genes generate abnormal imaginal discs in flies [106-110], consistent with their roles in the regulation of Hox gene expression. Amorphic and antimorphic mutations in the Ash1 gene lead to a drastic decrease in the global level of histone H3 K4 methyaltion [106-110]. The catalytic domain of ASH1 is 588 amino acid long, and comprises the SET domain and cysteine rich pre-SET and post-SET domains [106, 107]. However, the biochemical studies demonstrate that the 149 amino-acid-long SET domain alone can methylate histone H3 at K4 in vitro [107]. ASH1 also contains a PHD finger, and a BAH (bromo-associated homology) domain [111]. The BAH domain of ASH1 might be responsible for protein-protein interactions during chromatin remodeling at the target genes. ASH1 is an integral component of a large 2 MDa complex [112]. In addition to histone H3 K4 methylation, the ASH1 complex also methylates K9 of histone H3 and K20 of histone H4 [106, 107]. Recently, Tanaka et al [113] have implicated ASH1 in methylation of histone H3 at K36. Apart from its role in histone methylation, ASH1 is also linked to histone acetylation via its interaction with CBP [114] which is an integral component of TAC1. Thus, ASH1 and TAC1 appear to have common roles via CBP.

Like ASH1, ASH2 is present in a 500 kDa complex [112]. ASH2 has been proposed to be the associated form of Bre2 and Spp1 of S. cerevisae COMPASS [48, 71, 115]. In mammals, ASH2 is a shared components of different complexes including a HMT bound by host cell factor 1 (HCF-1), Menin-containing complex and the COMPASS counterpart [116-120], and thus, indicates that it might be involved in the regulation of many different processes. However, its role in histone methylation was not known. Recently, Steward et al [121] have demonstrated that ASH2 in mammalian system plays an important role in histone H3 K4 trimethylation. Consistent with this observation, Beltran et al [122] have observed a severe reduction of histone H3 K4 trimethylation in ash2 mutants. This observation indicates that ASH2 might play a crucial role in histone H3 K4 methyltransferase activity. However, ASH2 does not contain a SET domain, but it has the PHD finger and SPRY domains [123]. In addition to its role in histone H3 K4 methylation, ASH2 is also linked to histone deacetylation through its interaction with Sin3A, a histone deacetylase [116]. Further, ASH2 has been implicated in the regulation of cell cycle progression via its interaction with HCF-1 [116].

Like trxG proteins, a trithorax-related (TRR) protein in Drosophila is also involved in methylation of histone H3 at K4 [124]. TRR contains the SET domain, and has histone H3 K4 methyltransferase activity [124]. TRR functions in the upstream of hedgehog (hh) in the progression of the morphogenic furrow [124]. It also participates in retinal differentiation [124]. TRR and trimethylated histone H3 at K4 is detected at the ecdysone-inducible promoters of hh and BR-C (broad complex) [124]. Ecdysone functions through binding to a nuclear receptor, EcR, which heterodimerizes with the retinoid X receptor homologue ultraspiracle. Such heterodimer is then recruited to the promoters of the target genes to regulate their expression, and hence, ecdysone triggers moulting and metamorphosis. Thus, the association of EcR along with TRR and histone H3 K4 methylation is also observed at the hh and BR-C promoters following ecdysone treatment in cultured cells [124]. Consistent with these observations, histone H3 K4 methylation is decreased at these promoters in embryos lacking functional TRR [124]. Thus, TRR appears to function as a coactivator at the ecdysone-responsive promoters by modulating the chromatin structure.

The histone H3 K4 methylation functions as a platform for the binding of different chromatin remodelers. One of such remodelers is the BRM complex that contains at least seven proteins [112]. Three components of the BRM complex are trxG proteins. These are BRM (brahma), Osa and Moira. However, these trxG protein components of the BRM complex do not have the SET domain as well as HMT activity. The BRM complex is the homolog of yeast SWI/SNF complex, and shares four components including the ATPase BRM [112]. BRM also contains an HMGB (high-mobility-group B) protein, namely BAP111, which binds nonspecifically to the minor groove of the double-helix, and bends the DNA [125, 126]. The BRM complex has ATP- dependent chromatin remodeling activity. Mutations in ash1 enhance brm mutations, suggesting that they might be functioning together [110]. Consistent with this observation, Beisel et al. [106] have demonstrated that epigenetic activation of Ubx transcription coincides with histone H3 K4 trimethylation by ASH1 and recruitment of the BRM complex. Similarly, mutations of ash2 and brm cause developmental defects of the adult sensory organs including campaniform sensilla and mechanosensory bristles [108, 127]. Thus, although ASH1, ASH2 and BRM are the components of three distinct complexes, they appear to function in concert to regulate transcription. Furthermore, histone H3 K4 methyltransferase activitity of TAC1 has been implicated to be linked to the BRM complex [112, 128]. Such linkage is mediated by the interaction of TRX of TAC1 with the SNR1 component of the BRM complex [128]. Together, these results indicate that histone H3 K4 methylation and ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler, BRM, function in a concerted manner to regulate transcription. Apart from the BRM complex, two other chromatin remodelers, namely NURF (nucleosome remodeling factor) and ACF (ATP-utilizing chromatin assembly and remodeling factor), have been implicated to participate in transcriptional stimulation through their binding to methylated-K4 of histone H3 that is mediated by TRX or other HMTs [100]. Both NURF and ACF are ATP-dependent remodelers, and carry ISW1 as an ATPase subunit [100]. Thus, the HMTs mark a modification pattern on histone H3 at K4 that is “read” by chromatin remodelers which, in turn, regulate the chromatin structure and hence gene expression.

Apart from histone H3 K4 methyltransferase and ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling activities, trxG protein is also involved in histone demethylation. Recent studies [129, 130] have demonstrated a trxG protein, namely Lid, contains a JmjC domain and other functional domains found in mammalian JARID1 (Jumonji, AT rich interactive domain 1) proteins. Lid has demethylase activity which can demethylate the trimethylated form of histone H3 at K4 (Table 4). Such demethylase activity of the trxG protein adds an additional layer to the gene regulation by the PcG and trxG proteins. Further, Lid interacts with the proteins associated with heterochromatin formation such as H3 K9 methyltransferase [Su(var)3-9], heterochromatin protein (HP1) and deacetylase (RPD3). Thus, Lid plays crucial roles in removing the activation marks, hence facilitating gene silencing.

Role of histone H3 K4 methylation and its regulation in Drosophila is largely conserved in mammals. However, the complexity of mammals demands a more intricate mechanism of regulation in determining the cell lineages and developmental fates. Thus, a large number of studies have been focused on histone H3 K4 methylation and HMTs, and their roles in gene regulation with implications in development in mammals. We discuss below histone H3 K4 methyltransferases and histone H3 K4 methylation in mouse and human with their regulatory roles in gene expression.

Histone H3 K4 methylation and HMTs in mouse and human

Histones are among the most conserved proteins during evolution of eukaryotes. As discussed for other eukaryotes, roles of histone methylation in maintaining epigenetic memory, gene regulation and development are largely conserved in mammals. Genomic studies have revealed that both mouse and humans have about 30,000 genes, and mouse has orthologs of 99% of the human genes (Mouse Genome Sequencing Consortium, 2002). Given the close conservation between these two systems, we have reviewed together the progresses made towards histone H3 K4 methylation and the corresponding HMTs in both mouse and human. The histone H3 K4 trimethylation patterns in mammals are similar to yeast, and are associated with transcriptional start sites. The histone H3 K4 dimethylation, however, has a distinct distribution pattern. Genomic mapping studies have revealed that histone H3 K4 dimethylation overlaps with histone H3 K4 trimethylation in the vicinity of active genes [131, 132]. However, significant H3 K4 methylation is also observed at the inactive genes within β-globin locus. This observation suggests that histone H3 K4 methylation may be playing important roles in maintaining transcriptional “poised state” [131], in addition to its role in transcriptional stimulation.

Although histone H3 K4 methylation is usually localized to punctuate sites, a unique pattern of histone H3 K4 methylation is found at the HOX gene cluster in mammals. Broad regions of continuous histone H3 K4 methylation spanning multiple genes with the intergenic regions are observed at HOX gene clusters in mouse and human [132]. Unlike in yeast which has just one histone H3 K4 methyltransferase, mammals have at least ten histone H3 K4 methyltransferases (Table 1) [33, 133-138]. Of these, six members containing the SET domain (MLL1, MLL2, MLL3, MLL4, SET1A, and SET1B) belong to the MLL (mixed lineage leukemia) family bearing homology to yeast Set1 and Drosophila TRX (Tables 2 and 3) [30, 33, 49, 133, 134]. Other histone H3 K4 methyltransferases identified are ASH1, SET7/9, SMYD3 and a Meiosis specific factor, Meisetz [33, 133, 134-138]. The presence of several HMTs in human might be due to the role of different HMTs at different developmental stages determining the cell fate. The MLL family of HMT proteins play important role in regulation of HOX gene expression. This is particularly significant as deregulation of HOX genes is associated with leukemia via the rearrangements of the MLL1 gene. In addition to the HOX genes, MLL1 also targets non-HOX genes like p27 and p18 [139]. Interestingly, deletions or truncations in MLL1, MLL2 and MLL3 genes have different phenotypes in mice. For example, deletion of MLL1 shows misregulation in a number of HOXA genes including HOXA1 [140-143]. While MLL2 controls the expression of HOXB2 and HOXB5, and loss of MLL3 causes severe growth retardation and widespread apoptosis [141-143]. Thus, MLL1, MLL2 and MLL3 appear to have non-redundant functions. Further, MLL proteins as well as histone H3 K4 methylation are involved in controlling epigenetic memory [134, 141-143].

As is true for yeast and other eukaryotes, MLL family HMTs are assembled into multisubunit complexes (Table 2). These complexes have three common subunits, WDR5 (WD repeat domain 5), RBPB5 (retinoblastoma binding protein 5) and ASH2L (Drosophila ASH2-like) [49, 116, 117, 119, 120, 133, 143]. These three subunits form the core of the complex. MLL SET is active only when it associates with the core complex, a feature reminiscent of S. cerevisae COMPASS [145]. WDR5 subunit of the MLL complex is essential for binding of MLL HMT to dimethylated-K4 of histone H3. It is also a key player in conversion of di- to trimethylation of histone H3 at K4. Consistent with this observation, the reduced level of histone H3 K4 trimethylation is observed following knockdown of WDR5. Consequently, HOX gene expression in human cells is significantly decreased in the absence of WDR5 [146]. Thus, WDR5 appears to play a crucial role to regulate the actitivities of MLL HMTs.

In addition to its role in histone H3 K4 methylation, MLL complex interacts with a TAF (TBP-associated factor) component of TFIID (transcription factor IID), components of E2F6 (E2F transcription factor 6) subcomplex, and MOF (a MYST family histone acetyltransferase involved in histone H3 K16 acetylation) [147]. The interaction between the MLL1 complex and MOF is particularly interesting as both histone H3 K4 methylation and histone H4 K16 acetylation are marks of active transcription, and hint towards the coordinated actions of histone H4 K16 acetylation and histone H3 K4 methylation in transcriptional regulation. Indeed, it has been shown that MLL1 HMT and MOF HAT activities are required for the proper expression of HoxA9 [145, 147]. Further, MLL3/MLL4 complex coordinates histone H3 K4 methylation with demethylation of histone H3 at K27 through its UTX subunit [49, 133, 134, 148, 149]. Furthermore, histone H3 K4 methylation is coupled to histone deacetylation by the interaction of HMTs SET1/ASH2 with SIN3 deacetylase [116]. Thus, HMTs in human appears to play diverse functions in regulation of gene expression, and hence development.

In addition to its role in mammalian development, histone H3 K4 methylation also participates in the maintenance of pluripotency. It has been demonstrated that the embryonic stem cells maintain “bivalent domains” of repressive (histone H3 K27 methylation) and activating (histone H3 K4 methylation) marks. The bivalent domains silence the developmental genes in embryonic stem cells while still preserving their ability to be activated in response to appropriate developmental cues [150]. However, bivalent domains are also maintained at other genes in fully differentiated cell types [151, 152].

The methylation is dynamically regulated by demethylases like LSD1 and JmjC domain-containing enzymes. Demethylase, LSD1, can demethylate mono- and dimethylated-K4 of histone H3 (Table 4). LSD1 has been shown to interact with repressors like CoREST and activation complex like MLL1. These observations implicated that MLL1 is involved in transcriptional activation as well as repression [33, 49, 153, 154]. Demethylation of trimethylated-K4 of histone H3 is catalyzed by JmjC domain-containing proteins. Mammals have four members of JARID family with the JmjC domain (Table 4). These are JARID1A or Rbp2, JARID1B or PLU-1, JARID1C or SMCX and JARID1D or SMCY [33, 155]. Both histone H3 K4 methyltransferases and demethylases function in a coordinated fashion to delicately regulate histone H3 K4 methylation, and hence gene expression.

Significance of understanding the regulation of histone H3 K4 methylation is exemplified by the occurrence of cancers and other diseases following mutations of histone H3 K4 methyltransferases and demethylases or their altered expression [33]. For example, MLL1 is translocated in leukemia. SMYD3 is overexpressed in colorectal cancer, liver, breast and cervical cancers. The demethylase, LSD1, is overexpressed in prostate cancer. The implication of HMTs and demethylases in cancer and human diseases has lead to the idea of utilizing them as therapeutic targets. In fact, biguanide and bisguanidine polyamine analogues inhibit the demethylase, LSD1, in human colon carcinoma cells. Inhibition of LSD1 facilitates the expression of the aberrantly silenced genes in cancer cells [156]. In addition to targeting a single enzyme, epigenetic therapy combining related proteins/pathways is a promising alternative. Thus, combinatorial therapy targeting HMTs, demethylases, histone deacetylases, DNA methyltransferases and others may work efficiently in treating the diseases caused by epigenetic misregulations. In fact, a combinatorial therapy targeting histone deacetylases and DNA methyltransferases has shown to have a synergistic role in gene regulation, and consistently, the clinical trials have yielded encouraging results [157-161].

Structural and functional studies have shown specific similarities and differences among the HMTs in diverse organisms. In mammals, the core components of the MLL complex: RBBP5, WDR5 and ASH2L form a structural platform for the catalytic SET1 to associate while Set1 in S. cerevisiae is required for the integrity of the COMPASS complex. In S. cerevisiae, Cps60/Bre2 does not interact directly with Cps50/Swd1. However, in mammals their homologs RBBP5 and ASH2L strongly interact in the complex. These different interactions imply diverse regulatory mechanisms of the HMTs. This suggests that in higher eukaryotes, the core complex can be similar, but different subunits can associate with this core complex at different stages of cell development to provide HMT activity. Thus, there are several HMT complexes in higher eukaryotes dedicated to diverse cellular roles. Further, the C-terminal SET domain is invariant in different HMTs while the N-terminal domains are divergent. This enables the HMTs to associate with a broad spectrum of proteins to ensue the downstream events. Given the increasing complexity in higher eukaryotes, the diversity of histone H3 K4 HMTs is not surprising. However, the conservation of the fundamental SET domain in all of these HMTs is intriguing. In addition, many of the histone H3 K4 HMTs share several domains/components, indicating a common mechanism of action.

Concluding Remarks

Studies in several eukaryotes demonstrate the conservation of histone H3 K4 HMTs from yeast to human. The roles of histone H3 K4 methylation in gene regulation, chromatin structure and development have been extensively investigated in a variety of organisms, and we are closer than ever to the understanding of the intricate regulatory functions of histone H3 K4 methylation and HMTs in gene expression (see also accompanying three related articles in this review series). However, several baffling questions still exist. For example, why do mammals need several HMTs while yeast survives with a sole HMT? How do different states (mono-, di- and trimethylation) of H3K4 methylation translate into distinct biological cues? What signals the precise balance of methylation and demethylation in a cell? A deeper understanding of this important epigenetic mark will be helpful in the quest of drugs for treatment of disorders caused due to aberrations in this covalent modification.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to the authors whose work could not be cited owing to space limitations. The work in the Bhaumik laboratory was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant (1R15GM088798-01), a National Scientist Development Grant (0635008N) from American Heart Association, a Research Scholar Grant (06-52) from American Cancer Society, a Mallinckrodt Foundation award, and several internal grants from Southern Illinois University.

References

- 1.Kornberg RD. Structure of chromatin. Annu Rev Biochem. 1977;46:931–954. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.46.070177.004435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kornberg RD, Lorch Y. Twenty-five years of the nucleosome, fundamental particle of the eukaryote chromosome. Cell. 1999;98:285–294. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81958-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodcock CL, Skoultchi AI, Fan Y. Role of linker histone in chromatin structure and function: H1 stoichiometry and nucleosome repeat length. Chromosome Res. 2006;14:17–25. doi: 10.1007/s10577-005-1024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger SL. Histone modifications in transcriptional regulation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:142–148. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bryk M, Briggs SD, Strahl BD, Curcio MJ, Allis CD, Winston F. Evidence that Set1, a factor required for methylation of histone H3, regulates rDNA silencing in S. cerevisiae by a Sir2-independent mechanism. Curr Biol. 2002;12:165–170. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00652-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischle W, Wang Y, Allis CD. Histone and chromatin cross-talk. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:172–183. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li B, Carey M, Workman JL. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell. 2007;128:707–719. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Razin SV, Iarovaia OV, Sjakste N, Sjakste T, Bagdoniene L, Rynditch AV, Eivazova ER, Lipinski M, Vassetzky YS. Chromatin domains and regulation of transcription. J Mol Biol. 2007;369:597–607. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groth A, Rocha W, Verreault A, Almouzni G. Chromatin challenges during DNA replication and repair. Cell. 2007;128:721–733. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becker PB, Horz W. ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:247–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gangaraju VK, Bartholomew B. Mechanisms of ATP dependent chromatin remodeling. Mutat Res. 2007;618:3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peterson CL. Multiple SWItches to turn on chromatin? Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:171–175. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)80047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peterson CL. SWI/SNF complex: dissection of a chromatin remodeling cycle. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1998;63:545–552. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1998.63.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vary JC, Jr, Gangaraju VK, Qin J, Landel CC, Kooperberg C, Bartholomew B, Tsukiyama T. Yeast Isw1p forms two separable complexes in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:80–91. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.80-91.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deuring R, Fanti L, Armstrong JA, Sarte M, Papoulas O, Prestel M, Daubresse G, Verardo M, Moseley SL, Berloco M, Tsukiyama T, Wu C, Pimpinelli S, Tamkun JW. The ISWI chromatin-remodeling protein is required for gene expression and the maintenance of higher order chromatin structure in vivo. Mol Cell. 2000;5:355–365. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80430-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Racki LR, Narlikar GJ. ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling enzymes: two heads are not better, just different. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsukiyama T, Palmer J, Landel CC, Shiloach J, Wu C. Characterization of the imitation switch subfamily of ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling factors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1999;13:686–697. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.6.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng Q, Zhang Y. The NuRD complex: linking histone modification to nucleosome remodeling. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2003;274:269–290. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-55747-7_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowen NJ, Fujita N, Kajita M, Wade PA. Mi-2/NuRD: multiple complexes for many purposes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1677:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Denslow SA, Wade PA. The human Mi-2/NuRD complex and gene regulation. Oncogene. 2007;26:5433–5438. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunert N, Brehm A. Novel Mi-2 related ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers. Epigenetics. 2009;4:209–211. doi: 10.4161/epi.8933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen X, Mizuguchi G, Hamiche A, Wu C. A chromatin remodelling complex involved in transcription and DNA processing. Nature. 2000;406:541–544. doi: 10.1038/35020123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conaway RC, Conaway JW. The INO80 chromatin remodeling complex in transcription, replication and repair. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bao Y, Shen X. INO80 subfamily of chromatin remodeling complexes. Mutat Res. 2007;618:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rice JC, Briggs SD, Ueberheide B, Barber CM, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Shinkai Y, Allis CD. Histone methyltransferases direct different degrees of methylation to define distinct chromatin domains. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1591–1598. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00479-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ehrenhofer-Murray AE. Chromatin dynamics at DNA replication, transcription and repair. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:2335–2349. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cosgrove MS, Wolberger C. How does the histone code work? Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;83:468–476. doi: 10.1139/o05-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shilatifard A. Chromatin modifications by methylation and ubiquitination: implications in the regulation of gene expression. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:243–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhaumik SR, Smith E, Shilatifard A. Covalent modifications of histones during development and disease pathogenesis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1008–1016. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kusch T, Workman JL. Histone variants and complexes involved in their exchange. Subcell Biochem. 2007;41:91–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shukla A, Chaurasia P, Bhaumik SR. Histone methylation and ubiquitination with their cross-talk and roles in gene expression and stability. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:1419–1433. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8605-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y. Transcriptional regulation by histone ubiquitination and deubiquitination. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2733–2740. doi: 10.1101/gad.1156403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ng HH, Feng Q, Wang H, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Zhang Y, Struhl K. Lysine methylation within the globular domain of histone H3 by Dot1 is important for telomeric silencing and Sir protein association. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1518–1527. doi: 10.1101/gad.1001502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider J, Shilatifard A. Histone demethylation by hydroxylation: chemistry in action. ACS Chem Biol. 2006;1:75–81. doi: 10.1021/cb600030b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider R, Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Unsafe SETs: histone lysine methyltransferases and cancer. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:396–402. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang GG, Allis CD, Chi P. Chromatin remodeling and cancer, Part I: Covalent histone modifications. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:363–372. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hake SB, Xiao A, Allis CD. Linking the epigenetic ‘language’ of covalent histone modifications to cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:761–769. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sims RJ, 3rd, Reinberg D. Histone H3 Lys 4 methylation: caught in a bind? Genes Dev. 2006;20:2779–2786. doi: 10.1101/gad.1468206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang K, Dent SY. Histone modifying enzymes and cancer: going beyond histones. J Cell Biochem. 2005;96:1137–1148. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pasini D, Bracken AP, Agger K, Christensen J, Hansen K, Cloos PA, Helin K. Regulation of stem cell differentiation by histone methyltransferases and demethylases. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2008;73:253–263. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2008.73.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cloos PA, Christensen J, Agger K, Helin K. Erasing the methyl mark: histone demethylases at the center of cellular differentiation and disease. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1115–1140. doi: 10.1101/gad.1652908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lan F, Nottke AC, Shi Y. Mechanisms involved in the regulation of histone lysine demethylases. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:316–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lan F, Shi Y. Epigenetic regulation: methylation of histone and non-histone proteins. Sci China C Life Sci. 2009;52:311–322. doi: 10.1007/s11427-009-0054-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krogan NJ, Dover J, Khorrami S, Greenblatt JF, Schneider J, Johnston M, Shilatifard A. COMPASS, a histone H3 (Lysine 4) methyltransferase required for telomeric silencing of gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10753–10755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200023200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Santos-Rosa H, Bannister AJ, Dehe PM, Geli V, Kouzarides T. Methylation of H3 lysine 4 at euchromatin promotes Sir3p association with heterochromatin. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47506–47512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407949200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller T, Krogan NJ, Dover J, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Johnston M, Greenblatt JF, Shilatifard A. COMPASS: a complex of proteins associated with a trithorax-related SET domain protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12902–12907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231473398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shilatifard A. Molecular implementation and physiological roles for histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) methylation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schneider J, Wood A, Lee JS, Schuster R, Dueker J, Maguire C, Swanson SK, Florens L, Washburn MP, Shilatifard A. Molecular regulation of histone H3 trimethylation by COMPASS and the regulation of gene expression. Mol Cell. 2005;19:849–856. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krogan NJ, Dover J, Wood A, Schneider J, Heidt J, Boateng MA, Dean K, Ryan OW, Golshani A, Johnston M, Greenblatt JF, Shilatifard A. The Paf1 complex is required for histone H3 methylation by COMPASS and Dot1p: linking transcriptional elongation to histone methylation. Mol Cell. 2003;11:721–729. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wood A, Schneider J, Dover J, Johnston M, Shilatifard A. The Paf1 complex is essential for histone monoubiquitination by the Rad6-Bre1 complex, which signals for histone methylation by COMPASS and Dot1p. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34739–34742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300269200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gerber M, Shilatifard A. Transcriptional elongation by RNA polymerase II and histone methylation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26303–26306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R300014200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ng HH, Robert F, Young RA, Struhl K. Targeted recruitment of Set1 histone methylase by elongating Pol II provides a localized mark and memory of recent transcriptional activity. Mol Cell. 2003;11:709–719. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee JS, Shukla A, Schneider J, Swanson SK, Washburn MP, Florens L, Bhaumik SR, Shilatifard A. Histone crosstalk between H2B monoubiquitination and H3 methylation mediated by COMPASS. Cell. 2007;131:1084–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wood A, Shukla A, Schneider J, Lee JS, Stanton JD, Dzuiba T, Swanson SK, Florens L, Washburn MP, Wyrick J, Bhaumik SR, Shilatifard A. Ctk complex-mediated regulation of histone methylation by COMPASS. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:709–720. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01627-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shukla A, Stanojevic N, Duan Z, Sen P, Bhaumik SR. Ubp8p, a histone deubiquitinase whose association with SAGA is mediated by Sgf11p, differentially regulates lysine 4 methylation of histone H3 in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3339–3352. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.9.3339-3352.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shukla A, Stanojevic N, Duan Z, Shadle T, Bhaumik SR. Functional analysis of H2B-Lys-123 ubiquitination in regulation of H3-Lys-4 methylation and recruitment of RNA polymerase II at the coding sequences of several active genes in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19045–19054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513533200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Latham JA, Dent SY. Cross-regulation of histone modifications. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1017–1024. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sun ZW, Allis CD. Ubiquitination of histone H2B regulates H3 methylation and gene silencing in yeast. Nature. 2002;418:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature00883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dover J, Schneider J, Tawiah-Boateng MA, Wood A, Dean K, Johnston M, Shilatifard A. Methylation of histone H3 by COMPASS requires ubiquitination of histone H2B by Rad6. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:28368–28371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200348200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shahbazian MD, Zhang K, Grunstein M. Histone H2B ubiquitylation controls processive methylation but not monomethylation by Dot1 and Set1. Mol Cell. 2005;19:271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weake VM, Workman JL. Histone ubiquitination: triggering gene activity. Mol Cell. 2008;29:653–663. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dehe PM, Pamblanco M, Luciano P, Lebrun R, Moinier D, Sendra R, Verreault A, Tordera V, Geli V. Histone H3 lysine 4 mono-methylation does not require ubiquitination of histone H2B. J Mol Biol. 2005;353:477–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liang G, Klose RJ, Gardner KE, Zhang Y. Yeast Jhd2p is a histone H3 Lys4 trimethyl demethylase. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:243–245. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Briggs SD, Bryk M, Strahl BD, Cheung WL, Davie JK, Dent SY, Winston F, Allis CD. Histone H3 lysine 4 methylation is mediated by Set1 and required for cell growth and rDNA silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3286–3295. doi: 10.1101/gad.940201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Noma K, Allis CD, Grewal SI. Transitions in distinct histone H3 methylation patterns at the heterochromatin domain boundaries. Science. 2001;293:1150–1155. doi: 10.1126/science.1064150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Litt MD, Simpson M, Gaszner M, Allis CD, Felsenfeld G. Correlation between histone lysine methylation and developmental changes at the chicken beta-globin locus. Science. 2001;293:2453–2455. doi: 10.1126/science.1064413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Noma K, Grewal SI. Histone H3 lysine 4 methylation is mediated by Set1 and promotes maintenance of active chromatin states in fission yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99 4:16438–16445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182436399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Roguev A, Schaft D, Shevchenko A, Aasland R, Stewart AF. High conservation of the Set1/Rad6 axis of histone 3 lysine 4 methylation in budding and fission yeasts. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8487–8493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209562200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roguev A, Schaft D, Shevchenko A, Pijnappel WW, Wilm M, Aasland R, Stewart AF. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Set1 complex includes an Ash2 homologue and methylates histone 3 lysine 4. EMBO J. 2001;20:7137–7148. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Roguev A, Shevchenko A, Schaft D, Thomas H, Stewart AF, Shevchenko A. A comparative analysis of an orthologous proteomic environment in the yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:125–132. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300081-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Opel M, Lando D, Bonilla C, Trewick SC, Boukaba A, Walfridsson J, Cauwood J, Werler PJ, Carr AM, Kouzarides T, Murzina NV, Allshire RC, Ekwall K, Laue ED. Genome-wide studies of histone demethylation catalysed by the fission yeast homologues of mammalian LSD1. PLoS One. 2007;2:e386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nicolas E, Lee MG, Hakimi MA, Cam HP, Grewal SI, Shiekhattar R. Fission yeast homologs of human histone H3 lysine 4 demethylase regulate a common set of genes with diverse functions. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35983–35988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schaner CE, Kelly WG. Germline chromatin. WormBook. 2006:1–14. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.73.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Seydoux G, Dunn MA. Transcriptionally repressed germ cells lack a subpopulation of phosphorylated RNA polymerase II in early embryos of Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster. Development. 1997;124:2191–2201. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.11.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schaner CE, Deshpande G, Schedl PD, Kelly WG. A conserved chromatin architecture marks and maintains the restricted germ cell lineage in worms and flies. Dev Cell. 2003;5:747–757. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Simonet T, Dulermo R, Schott S, Palladino F. Antagonistic functions of SET-2/SET1 and HPL/HP1 proteins in C. elegans development. Dev Biol. 2007;312:367–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hsu DR, Meyer BJ. The dpy-30 gene encodes an essential component of the Caenorhabditis elegans dosage compensation machinery. Genetics. 1994;137:999–1018. doi: 10.1093/genetics/137.4.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Katz DJ, Edwards TM, Reinke V, Kelly WG. A C elegans LSD1 demethylase contributes to germline immortality by reprogramming epigenetic memory. Cell. 2009;137:308–320. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Eimer S, Lakowski B, Donhauser R, Baumeister R. Loss of spr-5 bypasses the requirement for the C.elegans presenilin sel-12 by derepressing hop-1. EMBO J. 2002;21:5787–5796. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jarriault S, Greenwald I. Suppressors of the egg-laying defective phenotype of sel-12 presenilin mutants implicate the CoREST corepressor complex in LIN-12/Notch signaling in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2713–2728. doi: 10.1101/gad.1022402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lakowski B, Roelens I, Jacob S. CoREST-like complexes regulate chromatin modification and neuronal gene expression. J Mol Neurosci. 2006;29:227–239. doi: 10.1385/JMN:29:3:227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shi Y, Lan F, Matson C, Mulligan P, Whetstine JR, Cole PA, Casero RA, Shi Y. Histone demethylation mediated by the nuclear amine oxidase homolog LSD1. Cell. 2004;119:941–953. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McColl G, Killilea DW, Hubbard AE, Vantipalli MC, Melov S, Lithgow GJ. Pharmacogenetic analysis of lithium-induced delayed aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:350–357. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705028200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sulston JE. Neuronal cell lineages in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1983;48(Pt 2):443–452. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1983.048.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pirrotta V. Polycombing the genome: PcG, trxG, and chromatin silencing. Cell. 1998;93:333–336. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mahmoudi T, Verrijzer CP. Chromatin silencing and activation by Polycomb and trithorax group proteins. Oncogene. 2001;20:3055–3066. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dejardin J, Cavalli G. Epigenetic inheritance of chromatin states mediated by Polycomb and trithorax group proteins in Drosophila. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2005;38:31–63. doi: 10.1007/3-540-27310-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Orlando V. Polycomb, epigenomes, and control of cell identity. Cell. 2003;112:599–606. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ringrose L, Paro R. Epigenetic regulation of cellular memory by the Polycomb and Trithorax group proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 2004;38:413–443. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.091907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Beltran S, Blanco E, Serras F, Perez-Villamil B, Guigo R, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Corominas M. Transcriptional network controlled by the trithorax-group gene ash2 in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3293–3298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0538075100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Collins RT, Treisman JE. Osa-containing Brahma chromatin remodeling complexes are required for the repression of wingless target genes. Genes Dev. 2000;14:3140–3152. doi: 10.1101/gad.854300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Smith ST, Petruk S, Sedkov Y, Cho E, Tillib S, Canaani E, Mazo A. Modulation of heat shock gene expression by the TAC1 chromatin-modifying complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:162–167. doi: 10.1038/ncb1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Moazed D, O'Farrell PH. Maintenance of the engrailed expression pattern by Polycomb group genes in Drosophila. Development. 1992;116:805–810. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.3.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Brizuela BJ, Kennison JA. The Drosophila homeotic gene moira regulates expression of engrailed and HOM genes in imaginal tissues. Mech Dev. 1997;65:209–220. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Randsholt NB, Maschat F, Santamaria P. Polyhomeotic controls engrailed expression and the hedgehog signaling pathway in imaginal discs. Mech Dev. 2000;95:89–99. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00342-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kuzin B, Tillib S, Sedkov Y, Mizrokhi L, Mazo A. The Drosophila trithorax gene encodes a chromosomal protein and directly regulates the region-specific homeotic gene fork head. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2478–2490. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.20.2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Netter S, Fauvarque MO, Diez del Corral R, Dura JM, Coen D. white+ transgene insertions presenting a dorsal/ventral pattern define a single cluster of homeobox genes that is silenced by the polycomb-group proteins in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1998;149:257–275. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.1.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Grimaud C, Negre N, Cavalli G. From genetics to epigenetics: the tale of Polycomb group and trithorax group genes. Chromosome Res. 2006;14:363–375. doi: 10.1007/s10577-006-1069-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ingham PW. A gene that regulates the bithorax complex differentially in larval and adult cells of Drosophila. Cell. 1984;37:815–823. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90416-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kennison JA. The Polycomb and trithorax group proteins of Drosophila: trans-regulators of homeotic gene function. Annu Rev Genet. 1995;29:289–303. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.29.120195.001445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.LaJeunesse D, Shearn A. Trans-regulation of thoracic homeotic selector genes of the Antennapedia and bithorax complexes by the trithorax group genes: absent, small, and homeotic discs 1 and 2. Mech Dev. 1995;53:123–39. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Petruk S, Sedkov Y, Smith S, Tillib S, Kraevski V, Nakamura T, Canaani E, Croce CM, Mazo A. Trithorax and dCBP acting in a complex to maintain expression of a homeotic gene. Science. 2001;294:1331–1334. doi: 10.1126/science.1065683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sanchez-Elsner T, Sauer F. The heat is on with TAC1. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:92–93. doi: 10.1038/ncb0204-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Beisel C, Imhof A, Greene J, Kremmer E, Sauer F. Histone methylation by the Drosophila epigenetic transcriptional regulator Ash1. Nature. 2002;419:857–862. doi: 10.1038/nature01126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Byrd KN, Shearn A. ASH1, a Drosophila trithorax group protein, is required for methylation of lysine 4 residues on histone H3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11535–11540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1933593100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Adamson AL, Shearn A. Molecular genetic analysis of Drosophila ash2, a member of the trithorax group required for imaginal disc pattern formation. Genetics. 1996;144:621–633. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.2.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Angulo M, Corominas M, Serras F. Activation and repression activities of ash2 in Drosophila wing imaginal discs. Development. 2004;131:4943–4953. doi: 10.1242/dev.01380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tripoulas NA, Hersperger E, La Jeunesse D, Shearn A. Molecular genetic analysis of the Drosophila melanogaster gene absent, small or homeotic discs1 (ash1) Genetics. 1994;137:1027–1038. doi: 10.1093/genetics/137.4.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tripoulas N, LaJeunesse D, Gildea J, Shearn A. The Drosophila ash1 gene product, which is localized at specific sites on polytene chromosomes, contains a SET domain and a PHD finger. Genetics. 1996;143:913–928. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.2.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Papoulas O, Beek SJ, Moseley SL, McCallum CM, Sarte M, Shearn A, Tamkun JW. The Drosophila trithorax group proteins BRM, ASH1 and ASH2 are subunits of distinct protein complexes. Development. 1998;125:3955–3966. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.20.3955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tanaka Y, Katagiri Z, Kawahashi K, Kioussis D, Kitajima S. Trithorax-group protein ASH1 methylates histone H3 lysine 36. Gene. 2007;397:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bantignies F, Goodman RH, Smolik SM. Functional interaction between the coactivator Drosophila CREB-binding protein and ASH1, a member of the trithorax group of chromatin modifiers. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:9317–9330. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.24.9317-9330.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Nagy PL, Griesenbeck J, Kornberg RD, Cleary ML. A trithorax-group complex purified from Saccharomyces cerevisiae is required for methylation of histone H3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:90–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221596698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wysocka J, Myers MP, Laherty CD, Eisenman RN, Herr W. Human Sin3 deacetylase and trithorax-related Set1/Ash2 histone H3-K4 methyltransferase are tethered together selectively by the cell-proliferation factor HCF-1. Genes Dev. 2003;17:896–911. doi: 10.1101/gad.252103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lee JH, Skalnik DG. CpG-binding protein (CXXC finger protein 1) is a component of the mammalian Set1 histone H3-Lys4 methyltransferase complex, the analogue of the yeast Set1/COMPASS complex. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41725–41731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508312200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Goo YH, Sohn YC, Kim DH, Kim SW, Kang MJ, Jung DJ, Kwak E, Barlev NA, Berger SL, Chow VT, Roeder RG, Azorsa DO, Meltzer PS, Suh PG, Song EJ, Lee KJ, Lee YC, Lee JW. Activating signal cointegrator 2 belongs to a novel steady-state complex that contains a subset of trithorax group proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:140–149. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.140-149.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hughes CM, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Milne TA, Copeland TD, Levine SS, Lee JC, Hayes DN, Shanmugam KS, Bhattacharjee A, Biondi CA, Kay GF, Hayward NK, Hess JL, Meyerson M. Menin associates with a trithorax family histone methyltransferase complex and with the hoxc8 locus. Mol Cell. 2004;13:587–597. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Yokoyama A, Wang Z, Wysocka J, Sanyal M, Aufiero DJ, Kitabayashi I, Herr W, Cleary ML. Leukemia proto-oncoprotein MLL forms a SET1-like histone methyltransferase complex with menin to regulate Hox gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5639–5649. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5639-5649.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Steward MM, Lee JS, O'Donovan A, Wyatt M, Bernstein BE, Shilatifard A. Molecular regulation of H3K4 trimethylation by ASH2L, a shared subunit of MLL complexes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:852–854. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Beltran S, Angulo M, Pignatelli M, Serras F, Corominas M. Functional dissection of the ash2 and ash1 transcriptomes provides insights into the transcriptional basis of wing phenotypes and reveals conserved protein interactions. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R67. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Schwartz YB, Pirrotta V. Polycomb silencing mechanisms and the management of genomic programmes. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrg1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Sedkov Y, Cho E, Petruk S, Cherbas L, Smith ST, Jones RS, Cherbas P, Canaani E, Jaynes JB, Mazo A. Methylation at lysine 4 of histone H3 in ecdysone-dependent development of Drosophila. Nature. 2003;426:78–83. doi: 10.1038/nature02080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Thomas JO, Travers AA. HMG1 and 2, and related ‘architectural’ DNA-binding proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:167–174. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01801-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Papoulas O, Daubresse G, Armstrong JA, Jin J, Scott MP, Tamkun JW. The HMG-domain protein BAP111 is important for the function of the BRM chromatin-remodeling complex in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5728–5733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091533398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Elfring LK, Daniel C, Papoulas O, Deuring R, Sarte M, Moseley S, Beek SJ, Waldrip WR, Daubresse G, DePace A, Kennison JA, Tamkun JW. Genetic analysis of brahma: the Drosophila homolog of the yeast chromatin remodeling factor SWI2/SNF2. Genetics. 1998;148:251–265. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.1.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Rozovskaia T, Burakov D, Sedkov Y, Tillib S, Blechman J, Nakamura T, Croce CM, Mazo A, Canaani E. The C-terminal SET domains of ALL-1 and TRITHORAX interact with the INI1 and SNR1 proteins, components of the SWI/SNF complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4152–4157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Lee N, Zhang J, Klose RJ, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Jones RS, Zhang Y. The trithorax-group protein Lid is a histone H3 trimethyl-Lys4 demethylase. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:341–343. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Secombe J, Li L, Carlos L, Eisenman RN. The Trithorax group protein Lid is a trimethyl histone H3K4 demethylase required for dMyc-induced cell growth. Genes Dev. 2007;21:537–551. doi: 10.1101/gad.1523007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Schneider R, Bannister AJ, Myers FA, Thorne AW, Crane-Robinson C, Kouzarides T. Histone H3 lysine 4 methylation patterns in higher eukaryotic genes. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:73–77. doi: 10.1038/ncb1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Bernstein BE, Kamal M, Lindblad-Toh K, Bekiranov S, Bailey DK, Huebert DJ, McMahon S, Karlsson EK, Kulbokas EJ, 3rd, Gingeras TR, Schreiber SL, Lander ES. Genomic maps and comparative analysis of histone modifications in human and mouse. Cell. 2005;120:169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ruthenburg AJ, Allis CD, Wysocka J. Methylation of lysine 4 on histone H3: intricacy of writing and reading a single epigenetic mark. Mol Cell. 2007;25:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Campos EI, Reinberg D. Histones: annotating chromatin. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:559–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.032608.103928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Wang H, Cao R, Xia L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Borchers C, Tempst P, Zhang Y. Purification and functional characterization of a histone H3-lysine 4-specific methyltransferase. Mol Cell. 2001;8:1207–1217. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00405-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Nishioka K, Rice JC, Sarma K, Erdjument-Bromage H, Werner J, Wang Y, Chuikov S, Valenzuela P, Tempst P, Steward R, Lis JT, Allis CD, Reinberg D. PR-Set7 is a nucleosome-specific methyltransferase that modifies lysine 20 of histone H4 and is associated with silent chromatin. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1201–1213. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00548-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Hamamoto R, Furukawa Y, Morita M, Iimura Y, Silva FP, Li M, Yagyu R, Nakamura Y. SMYD3 encodes a histone methyltransferase involved in the proliferation of cancer cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:731–740. doi: 10.1038/ncb1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Hayashi K, Yoshida K, Matsui Y. A histone H3 methyltransferase controls epigenetic events required for meiotic prophase. Nature. 2005;438:374–378. doi: 10.1038/nature04112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Milne TA, Dou Y, Martin ME, Brock HW, Roeder RG, Hess JL. MLL associates specifically with a subset of transcriptionally active target genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14765–14770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503630102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Ernst P, Mabon M, Davidson AJ, Zon LI, Korsmeyer SJ. An Mll-dependent Hox program drives hematopoietic progenitor expansion. Curr Biol. 2004;14:2063–2069. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Terranova R, Agherbi H, Boned A, Meresse S, Djabali M. Histone and DNA methylation defects at Hox genes in mice expressing a SET domain-truncated form of Mll. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6629–6634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507425103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Yu BD, Hess JL, Horning SE, Brown GA, Korsmeyer SJ. Altered Hox expression and segmental identity in Mll-mutant mice. Nature. 1995;378:505–508. doi: 10.1038/378505a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Lee S, Lee DK, Dou Y, Lee J, Lee B, Kwak E, Kong YY, Lee SK, Roeder RG, Lee JW. Coactivator as a target gene specificity determinant for histone H3 lysine 4 methyltransferases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15392–15397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607313103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Milne TA, Briggs SD, Brock HW, Martin ME, Gibbs D, Allis CD, Hess JL. MLL targets SET domain methyltransferase activity to Hox gene promoters. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1107–1117. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00741-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]