Abstract

Both end structures of eukaryotic mRNAs, namely the 5′ cap and 3′ poly(A) tail, are necessary for transcript stability, and loss of either is sufficient to stimulate decay. mRNA turnover is classically thought to be initiated by deadenylation, as has been particularly well described in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Here we describe two additional, parallel decay pathways in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. First, in fission yeast mRNA decapping is frequently independent of deadenylation. Second, Cid1-dependent uridylation of polyadenylated mRNAs, such as act1, hcn1 and urg1, appears to stimulate decapping as part of a novel mRNA turnover pathway. Accordingly, urg1 mRNA is stabilized in cid1∆ cells. Uridylation and deadenylation act redundantly to stimulate decapping, and our data suggest that uridylation-dependent decapping is mediated by the Lsm1-7 complex. As human cells contain Cid1 orthologs, uridylation may form the basis of a widespread, conserved mechanism of mRNA decay.

In budding yeast, most cytoplasmic mRNA turnover is initiated by deadenylation1. These messages are then either decapped and subject to 5′→3′ decay2,3 or degraded by the cytoplasmic exosome4. Although these decay pathways are conserved5,6, metazoans and fission yeast contain additional cytoplasmic RNA-processing enzymes; the roles of many of these have not yet been determined. S. pombe Cid1 is one such enzyme, a cytoplasmic member of a family of RNA nucleotidyl transferases7,8.

Cid1, identified through its involvement in the S-M checkpoint7, is now known to be one of a subgroup of this family possessing either poly(U) polymerase (PUP) and/or terminal uridyl transferase (TUTase) activity9. This subgroup also includes the human enzymes U6 TUTase, Hs2 and Hs39-11, although no member of this subgroup is present in budding yeast12.

Uridylation of mRNAs and non-coding RNAs has been described in fission yeast and metazoans. Known substrates include miRNA-directed cleavage products13 and replication-dependent histone mRNAs, which in metazoans contain a 3′ stem-loop structure rather than a poly(A) tail, and decay of which is stimulated by oligouridylation14-16. In addition, we previously observed terminal uridyl residues on polyadenylated S. pombe act1 mRNA during S-phase arrest9. While it seemed likely that Cid1-mediated uridylation was generally involved in mRNA metabolism, the effect of such modification on polyadenylated messages was unclear.

Here, we have used a circularized RACE (cRACE) technique to capture mRNA decay intermediates in S. pombe. Surprisingly, in contrast to the situation in S. cerevisiae, we find that decapped intermediates often contain substantial poly(A) tails, indicative of a novel deadenylation-independent decapping pathway for bulk mRNA in fission yeast. We also show that uridylation of polyadenylated mRNAs forms the basis for an additional 5′→3′ decay pathway, likely conserved in higher eukaryotes, which elicits decapping and appears to be mediated by the Lsm1-7 complex. Uridylation and deadenylation have overlapping and distinct stimulatory effects on decapping of polyadenylated mRNAs.

RESULTS

cRACE captures act1 mRNA degradation intermediates

To dissect RNA decay pathways in fission yeast, we employed the cRACE technique6. A tail-independent method of capturing 3′ and 5′ ends, this procedure allows distinction between decapped and capped mRNAs (Fig. 1a). Decapped and capped act1 transcripts from exponentially growing wild-type (WT) cells were first examined.

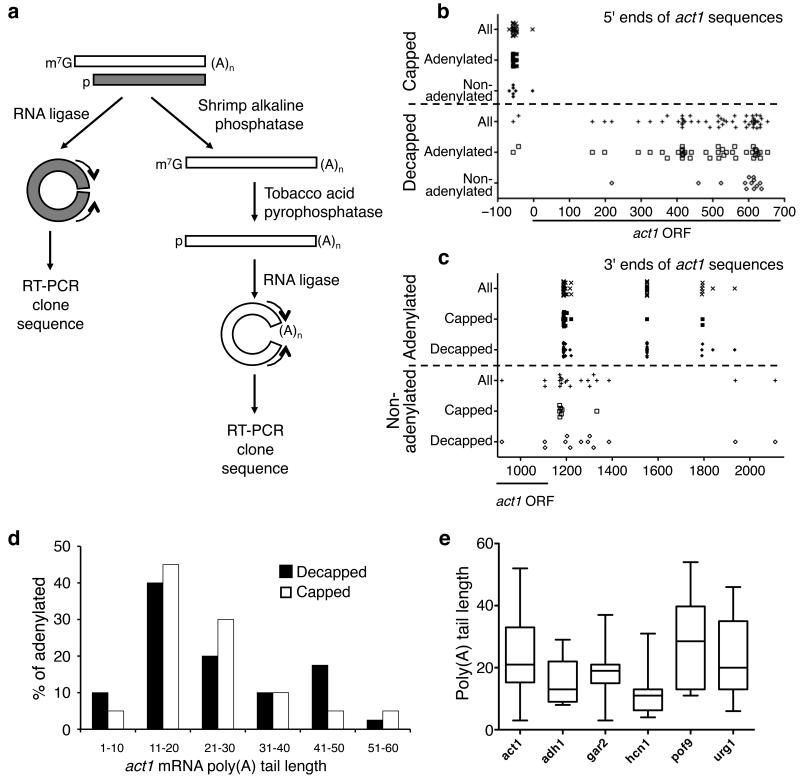

Figure 1. Decapping of mRNA can be independent of deadenylation.

(a) Overview of the cRACE procedures used to capture ends of decapped transcripts (gray) and mature transcripts (white). For details see Methods. (b, c) The 5′ (b) and 3′ (c) ends of various types of act1 cRACE sequences are plotted as the distance (in nt, as indicated on the horizontal axis) from the start codon. The open reading frame (ORF) is marked with a line. (d) Poly(A) tail lengths of decapped [black; 40 sequences] and capped [white; 20 sequences] act1 cRACE sequences were binned into groups of ten nt. Tail lengths were then plotted as the percentage of adenylated species. (e) Box-and-whisker plots of poly(A) tail lengths found on six different decapped transcripts, act1, adh1, gar2, hcn1, pof9 and urg1 (n=40, 16, 11, 12, 8 and 39 respectively). This plot depicts the quartiles of poly(A) tail length with the whiskers representing the range of each data set, the boxplot demarcating the second and third quartiles, which are separated by the median.

We initially wished to determine whether those products isolated from decapped cRACE analysis were derived from decay intermediates. To do this, we compared the 5′ ends isolated from capped and decapped mRNAs (Fig. 1b). The 5′ ends of products from capped transcripts generally lay 57 or 58 nucleotides (nt) upstream from the start codon (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1 online). These nucleotides presumably represent the major transcription start site for act1. In contrast, the 5′ ends of decapped products were heterogeneous, always downstream from the major transcriptional start site and distributed significantly differently from the capped species (p<0.0001, two-tailed Mann-Whitney Test). Thus, we conclude that these products represent mRNAs that have been subject to decapping and subsequent partial 5′→3′ decay in vivo.

We next compared the 3′ ends of adenylated and non-adenylated transcripts (Fig. 1c). Similar to previous observations17, we detected three cleavage and polyadenylation sites in the act1 gene: the first approximately 1190 nt downstream from the start codon (and 60 nucleotides downstream from the stop codon); the second, 1550 nt downstream from the start codon; the third, almost 1800 nucleotides downstream from the start codon. While the exact site of cleavage and polyadenylation was heterogeneous for the proximal and distal sites, at the medial polyadenylation site cleavage occurred precisely at a single position.

Of the 54 sequences obtained for decapped transcripts, 14 were not adenylated; similarly, 7 of 27 cRACE products obtained for capped transcripts did not contain untemplated adenyl residues. The 3′ ends of these species were heterogeneous and did not coincide with those of polyadenylated species. Importantly, all but two of the 3′ ends of non-adenylated products mapped upstream from the most distal polyadenylation site. Thus, in the case of decapped transcripts, these data are consistent with concerted 5′→3′ and 3′→5′ decay. In the case of capped transcripts, these non-adenylated transcripts presumably arise either from on-going transcription or from 3′→5′ decay after deadenylation.

Deadenylation-independent decapping in S. pombe

Numerous decapped transcripts contained long poly(A) tails, surprising as deadenylation to oligo(A) tails is thought normally to precede decapping in budding yeast18. Importantly, when the poly(A) tail lengths of decapped and capped act1 RNAs were compared, there was no significant difference between the two (p=0.65; Fig. 1d). The average poly(A) tail length on decapped messages was 25 nt, and on capped messages, 23 nt. This result is consistent with a previous report19 that found no correlation between poly(A) tail length and mRNA stability in fission yeast. In contrast, when decapped S. cerevisiae act1 transcripts were analyzed, the average poly(A) tail length was 11 nt (Supplementary Fig. 2 online), consistent with previous analysis1. These tails were also significantly shorter than those observed on decapped S. pombe act1 mRNAs (p=9E-06). Together, these data suggest that, in contrast to S. cerevisiae, where decapping of most messages requires deadenylation1,18, a deadenylation-independent decay pathway for act1 mRNA exists in S. pombe.

Decapped cRACE analysis of five other transcripts, adh1, gar2, hcn1, pof9 and urg1, was also performed (Supplementary Fig. 3 online). These messages allowed us to test the generality of deadenylation-independent decapping. The distribution of poly(A) tail lengths differed between these six genes (Fig. 1e). The average poly(A) tail length on adh1 cRACE products was 16 nt and on hcn1 products, 12 nt. Comparison of poly(A) tail lengths of capped and decapped cRACE products, suggests that hcn1 mRNA is mainly degraded by deadenylation-dependent pathways (Supplementary Fig. 4 online). On the other hand, the average length of poly(A) tails on decapped urg1 products was 23 nt, and over a third of polyadenylated, decapped urg1 products contained poly(A) tails longer than 30 nt. Similarly, we captured decapped pof9 products with tails as long as 54 nt. Given that poly(A) tails on average are 40 nt in S. pombe19, these data indicate that some mRNA, such as act1, pof9 and urg1, are subject to deadenylation-independent decapping.

Decapped transcripts are often uridylated

One to two non-templated 3′ terminal uridyl residues were found on 25% of the polyadenylated, decapped act1 transcripts (Fig. 2a), suggesting a role for uridylation in a novel mRNA decay pathway. No terminal uridyl residues were observed on non-adenylated products. Similarly, terminal uridyl residues were found on 18% of decapped, adenylated urg1 messages, 25% of decapped, adenylated hcn1, adh1 and pof9 messages and 45% of decapped, adenylated gar2 messages (Fig. 2a). Uridylation thus appears to be a widespread mRNA modification in S. pombe. In contrast, no terminal uridyl residues were observed on 22 S. cerevisiae act1 cRACE products analyzed (p=0.005, Supplementary Fig. 2b online). This finding is consistent with the observation that budding yeast does not contain a Cid1 ortholog12,20.

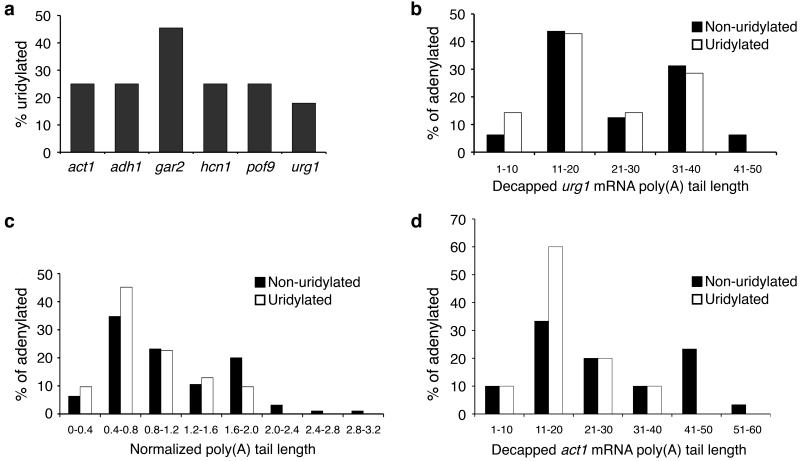

Figure 2. Decapped mRNAs are often uridylated.

(a) The percentage of decapped, adenylated cRACE products that contain terminal uridyl residues is shown for act1, adh1, gar2, hcn1, pof9 and urg1 (n= 10/40, 4/16, 5/11, 3/12, 2/8 and 7/39 respectively). (b) The poly(A) tail lengths of non-uridylated [black] and uridylated [white] decapped urg1 RNAs were binned into groups of ten nt. Tail lengths were then plotted as the percentage of adenylated species. (c) The poly(A) tail lengths of all non-uridylated [black; 31 sequences] and uridylated [white; 95 sequences] decapped transcripts are compared. For each transcript, each tail length was normalized to the median of non-uridylated tail length to correct for inter-transcript poly(A) tail length variability. These normalized lengths were then binned into groups and plotted as the percentage of adenylated species. (d) As in (b), the poly(A) tail lengths of non-uridylated [black] and uridylated [white] decapped act1 (b) were binned into groups of ten nt. Tail lengths were then plotted as the percentage of adenylated species.

In order to delineate this uridylation-dependent decay pathway, we first determined whether uridylation necessarily followed deadenylation by comparing the poly(A) tail lengths of uridylated and non-uridylated messages (Fig. 2b-d). Some long poly(A) tails did not have terminal uridyl residues, suggesting that the deadenylation-independent pathway described above is also uridylation-independent. Nevertheless, in several cases, terminal uridyl residues were found on poly(A) tails longer than 30 nt, suggesting that uridylation does not necessarily follow deadenylation. Indeed, for urg1 products (Fig. 2b), there was no difference between the lengths of poly(A) tails on uridylated and non-uridylated products (p=0.39, two-tailed Mann Whitney test).

To address this question more thoroughly, we compared the poly(A) tail lengths on uridylated and non-uridylated products for all six genes analyzed here (Fig. 2c). To correct for the difference in poly(A) tail length distribution between these transcripts, we first normalized within each gene to the median length of non-uridylated products. When we compared these normalized lengths of non-uridylated and uridylated transcripts of these six genes, no significant difference was observed (p=0.21, two-tailed Mann Whitney test). Nevertheless, it may be that individual transcripts, such as act1, are often degraded by the concerted action of uridylation and deadenylation (Fig. 2d). Taken together, these data suggest that uridylation and deadenylation can proceed both sequentially and in parallel.

Uridylation is Cid1-dependent

To investigate whether uridylation is Cid1-dependent, we performed act1 cRACE analysis on RNA from cid1∆ cells. Only one of 29 polyadenylated, decapped products (3.4%) contained a terminal uridyl residue (Fig. 3a), a significantly lower frequency than that observed in WT cells (p=0.007). We observed a tail of UUU on one nonadenylated, decapped transcript, out of a total of 45 products. No terminal uridyl residues were observed on capped messages. These data indicate that the majority of mRNA uridylation is dependent on Cid1 and suggest the presence of a second, minor uridylating enzyme in S. pombe. It is interesting to note that this low level of uridylation was not observed on budding yeast act1 products (Supplementary Fig. 2b online), perhaps indicating that this second enzyme is another Cid1 family member not found in S. cerevisiae.

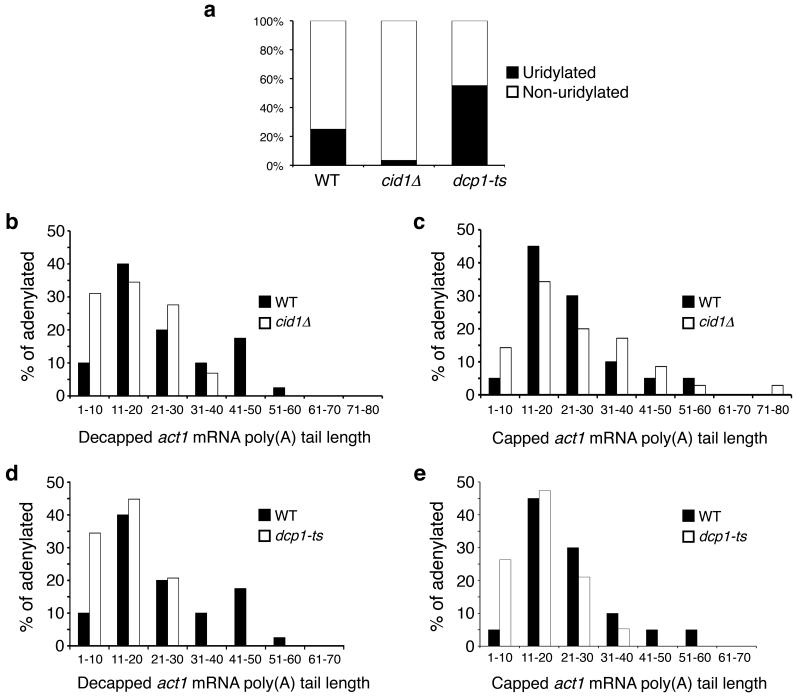

Figure 3. mRNA uridylation is Cid1-dependent and impairment of decapping increases uridylation on decapped messages.

(a) The percentage of adenylated, decapped act1 sequences that contain [black] or lack [white] terminal uridyl residues is plotted for sequences isolated from WT, cid1∆ and dcp1-ts cells (n=40, 29 and 20 respectively). (b, c) Poly(A) tail lengths, binned into groups of ten nt, of decapped (b) and capped (c) act1 sequences isolated from WT [black; n=40 and 20 respectively] and cid1∆ [white; n=29 and 36 respectively] cells are compared. (d, e) Poly(A) tail lengths, binned into groups of ten, of decapped (d) and capped (e) act1 sequences isolated from WT [black; n=40 and 20 respectively] and dcp1-ts [white; n=29 and 18 respectively] cells are compared.

The poly(A) tails of decapped act1 mRNAs isolated from cid1∆ cells were significantly shorter than those from WT cells (p=0.003; Fig. 3b). As there was no significant difference in the poly(A) tail length on capped transcripts (p=0.59; Fig. 3c), the shorter tails observed on decapped act1 transcripts in cid1∆ cells are most likely due to increased deadenylation (see below), consistent with the notion that uridylation and deadenylation play redundant roles in stimulating mRNA decay in fission yeast.

Uridylation precedes decapping

The above analysis did not allow us to determine whether uridylation precedes or follows decapping. To test this, we performed two experiments. First, a primer complementary to a region 90 nt downstream from the start codon was used during the PCR step, thus amplifying transcripts that had not been subject to substantial 5′→3′ decay (Supplementary Fig. 5 online). No significant difference in uridylation was observed between those products obtained with the upstream primer and those with the downstream primer used previously, which is complementary to a region 650 nt beyond the start codon (p=0.44). This result is consistent with uridylation preceding decapping.

In addition, act1 cRACE was performed on RNA from dcp1-ts cells (Supplementary Fig. 6 online), which contain a temperature-sensitive activator of decapping21. Even at the permissive temperature, decapping was impaired in these cells, as decapped and capped act1 cRACE products contained significantly shorter poly(A) tails than those in WT cells (p=9E-05 and p=0.011 respectively; Fig. 3d, e), consistent with previous reports that, in cells lacking the decapping enzyme, deadenylated, capped mRNA accumulates2. Strikingly, 55% of the decapped act1 cRACE products from dcp1-ts cells contained terminal uridyl residues (Fig. 3a). This represents a significant increase in comparison to WT cells (p=0.005). Moreover, this effect is specific to the decapping defect, as cells lacking Ski2, a cytoplasmic exosome component, did not show such an increase (Supplementary Fig. 5b online).

Due to the position of the most abundant transcriptional start site of act1, it was not possible to determine definitely by cRACE analysis whether capped mRNA was uridylated (Supplementary Fig. 7 online). To address whether 3′ uridylated, capped species accumulated in dcp1-ts cells, we used a 3′ cRACE technique called hybrid-selection cRACE (HSC-RACE)22, which has been used previously9 to demonstrate uridylation of act1 messages (Fig. 4a, b and Supplementary Tables 1, 2 online). Here, transcripts are specifically selected with a biotinylated RNA probe on magnetic streptavidin beads. The 3′ ends of the transcripts are liberated by oligonucleotide-directed RNase H cleavage and then circularized, amplified and sequenced as in cRACE. As RNase H cleavage precisely defines the 5′ ends of the captured RNAs, this procedure allows definitive sequencing of 3′ ends. The majority of these products are derived from the abundant, capped mRNAs. Consistent with the above cRACE analysis, the poly(A) tails on act1 mRNAs were significantly shorter in dcp1-ts cells than in WT cells (p=0.0002; Fig. 4c). While uridylation was observed on 17% of act1 transcripts in WT cells, this increased to 78% in dcp1-ts cells (p=0.0002; Fig. 4d). These data suggest that uridylation precedes decapping and, when decapping is impaired, uridylated, capped act1 intermediates accumulate.

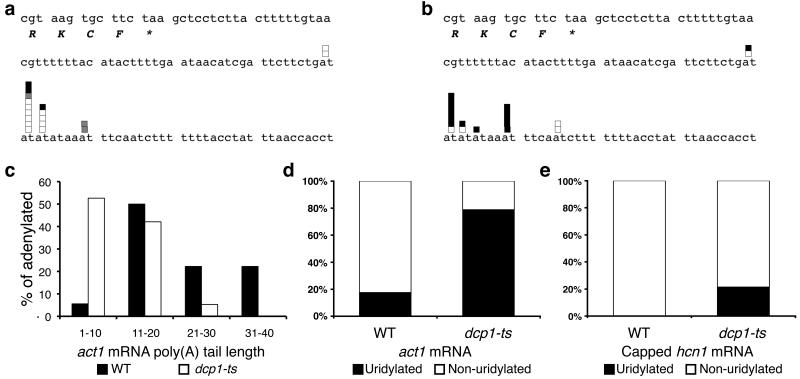

Figure 4. Uridylation precedes decapping.

(a, b) HSC-RACE products of total act1 transcripts isolated from WT cells (a) and dcp1-ts cells (b). The final four codons and stop codon [marked by *] are shown as well as the 3′ UTR. White boxes denote sequences with pure poly(A) tails; grey boxes denote poly(A) tails with internal non-adenyl residues; black boxes denote poly(A) tails with terminal uridyl residue(s). (c) Poly(A) tail lengths, binned into groups of ten nt, of HSC-RACE act1 species from WT [white bars] and dcp1-ts [black bars] cells. (d) Percentage of adenylated HSC-RACE act1 products that contain [black] or lack [white] terminal uridyl residues. (e) The percentage of capped hcn1 transcripts that contain [black] or lack [white] terminal uridyl residues is compared for RNA isolated from WT and dcp1-ts cells (n=18 and 14 respectively).

To support this analysis, we also used cRACE analysis to compare capped hcn1 transcripts isolated from WT and dcp1-ts cells. Interestingly, no uridylated, capped hcn1 intermediates were identified in WT cells (Fig. 4e). Uridylation-mediated decapping may itself be regulated by additional elements within the 3′ UTR such that decapping of uridylated hcn1 transcripts occurs more quickly than for uridylated act1 mRNAs. Importantly, when capped hcn1 transcripts in dcp1-ts cells were examined, 21% were now uridylated (p=0.02; Fig. 4e). Thus, we conclude that uridylation occurs prior to decapping as part of a novel mRNA decay pathway.

urg1 transcripts are stabilized in cid1∆ cells

We next wished to determine whether mRNA stability was affected by the absence of uridylation-dependent decapping. Determination of mRNA half-lives in other experimental systems is often based on the use of general transcriptional inhibitors, but inhibitors of this sort lacking various off-target effects have not yet been described in S. pombe19,23. As an alternative approach, we therefore examined urg1 mRNA: when uracil is removed from the medium, transcription of urg1 stops and the transcript undergoes rapid decay24. In addition, as urg1 is uridylated (Fig. 2a) and there are few off-target effects elicited by the removal of uracil24, this system appeared an ideal one to test the effect of uridylation on mRNA decay.

Mid-exponential cultures were grown in minimal medium containing uracil and then were shifted to medium lacking uracil to repress urg1 transcription. Samples were taken 0, 10, 20 and 30 minutes after uracil washout. The amount of urg1 mRNA remaining was quantified by northern blotting, normalized to pik1 mRNA, which is unaffected by the removal of uracil24, and the half-life of urg1 mRNA was determined.

In WT cells, urg1 mRNA had a half-life of 9.8±1.4 minutes (Fig. 5a, consistent with previous microarray analysis24. Importantly, in cells lacking Cid1, urg1 mRNA was stabilized, and the half-life of this transcript increased to 17.6±1.0 minutes, significantly longer than that in WT cells (p=0.0007, Fig. 5b). We conclude that Cid1-mediated uridylation stimulates the decay of urg1 mRNA.

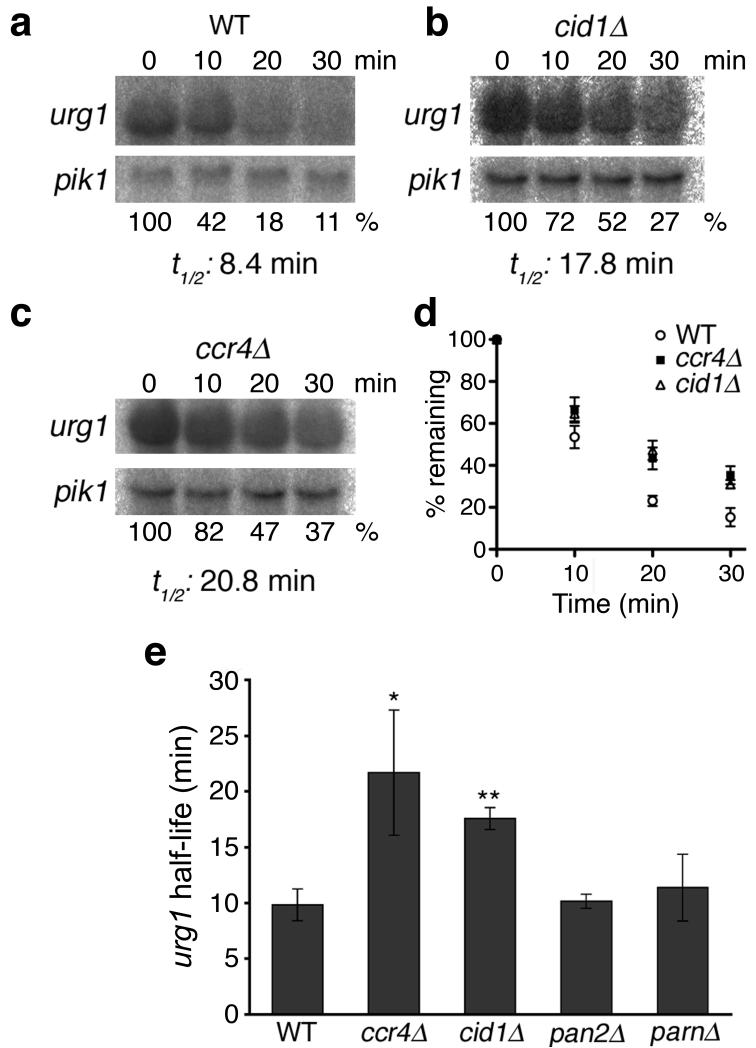

Figure 5. urg1 mRNA is more stable in cells lacking Cid1.

(a-c) Northern blots of urg1 transcript remaining at various time-points after uracil washout (top panel) in WT (a), cid1∆ (b) and ccr4∆ cells (c). urg1 levels were normalized to pik1 mRNA (bottom panel). The percentage of urg1 remaining at each time point (shown below the bottom panel) was calculated by comparison to the normalized amount at 0 minutes. (d) The percentage of urg1 mRNA remaining after uracil wash-out is shown for three strains, WT (open circles), ccr4∆ (black squares) and cid1∆ (open triangles). At least three independent replicates were performed; error bars represent SEM. (e) The half-life of urg1 mRNA in different strains is shown. At least two independent replicates were performed for each strain. * denotes p<0.01; ** denotes p<0.001. Error bars denote standard deviation.

The Ccr4-Caf1 deadenylase complex has been described as the major cytoplasmic deadenylase in budding yeast and mammalian cells25-27. In support of this view, deletion of ccr4 also resulted in an urg1 mRNA half-life longer than that in WT cells (21.7±5.6 minutes, p=0.009; Fig. 5c, d). Importantly, this did not differ significantly from that observed in cid1∆ cells (p=0.14). These data suggest that, like in budding yeast26, Ccr4-mediated deadenylation stimulates mRNA decay in fission yeast.

The fission yeast genome encodes two additional presumptive deadenylases, namely the Pan2-Pan3 complex and PARN. The Pan2-Pan3 complex is widely conserved among eukaryotes. In budding yeast, this complex is thought to be involved in nuclear trimming of poly(A) tails and is not a major factor in mRNA decay26,28,29. In line with analogous observations in budding yeast26, in pan2∆ cells urg1 mRNA was not stabilized and had a half-life of 10.2± 0.6 minutes (p=0.40; Fig. 6d). Although PARN has a role in specific mRNA decay pathways30,31, this deadenylase is notably absent from budding yeast and Drosophila melanogaster32. S. pombe PARN appears to not be a major enzyme in mRNA turnover, as urg1 half-life in parn∆ cells did not differ significantly from that in WT (half-life of 11.4± 3.0 minutes, p=0.24; Fig. 6d). Taken together, these data demonstrate that Cid1 and Ccr4, but neither the Pan2-Pan3 complex nor PARN, are important for mRNA decay, as judged by the increased stability of urg1 transcripts in the corresponding deletion strains. Thus, we suggest that deadenylation, mediated by Ccr4, and uridylation, mediated by Cid1, function in mRNA decay pathways in fission yeast.

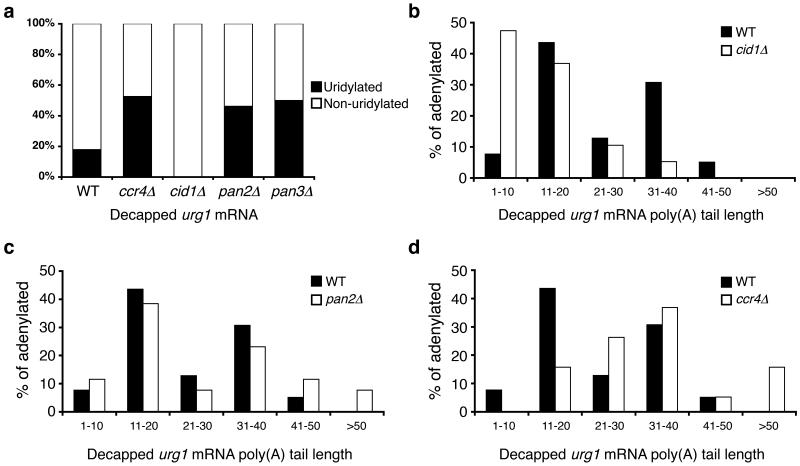

Figure 6. Deadenylation and uridylation function as redundant pathways in mRNA decay.

(a) The percentage of decapped, adenylated urg1 sequences that contain [black] or lack [white] terminal uridyl residues is compared for RNA isolated from WT, ccr4∆, cid1∆ cells, pan2∆ cells and pan3∆ cells (n=39, 19, 19, 27 and 20 respectively). (b-d) Poly(A) tail lengths, binned into groups of ten nt, of decapped urg1 mRNAs isolated from (b) cid1∆ cells [white], (c) pan∆ cells [white] and (d) ccr4∆ cells [white] compared to those products from wild-type cells [black].

In cells lacking both Cid1 and Ccr4, urg1 mRNA was again stabilized (half-life of 19.0±1.6 minutes, p=0.0008; Supplementary Fig. 8 online) though this half-life did not differ significantly from that observed in either of the single deletion strains. It seems likely that uridylation and deadenylation have distinct, though overlapping influences on mRNA stability. Accordingly, other deadenylases, such as the Pan2-Pan3 complex or PARN, may be able to act redundantly with Cid1 and the Ccr4-Caf1 complex, as has been suggested in both budding yeast and human cells26,27. Nevertheless, as urg1 mRNA is stabilized in cid1∆ cells, we conclude that uridylation forms the basis of a novel decay pathway for polyadenylated mRNA.

Uridylation and deadenylation are redundant pathways

We next hypothesized that, if uridylation and deadenylation act redundantly to lead to decapping and mRNA decay, then cells lacking uridylation might display increased deadenylation and, conversely, cells lacking deadenylases might show increased uridylation. To address this, we performed cRACE analysis on decapped urg1 transcripts isolated from cells lacking Cid1, Ccr4, Pan2 or Pan3 (Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. 9 online). This analysis was performed on cells grown in rich medium, which contains uracil, to ensure that sufficient urg1 mRNA was present to enable analysis.

We investigated the uridylation of decapped urg1 transcripts in cid1∆ cells. While in WT cells, as described above, 18% of urg1 cRACE products contained a terminal uridyl residue, none of the 19 decapped, adenylated products analyzed in cid1∆ cells contained a terminal uridyl residue (p=0.03; Fig. 6a). In addition, as with decapped act1 products (Fig. 2), decapped urg1 messages from cid1∆ cells contained significantly shorter poly(A) tails than those found in WT cells (p=0.001, one-tailed Mann Whitney test; Fig. 6b). Thus, it seems likely that deadenylation is able to compensate when uridylation-mediated decapping is lacking.

We next characterized poly(A) tails on decapped transcripts from the deadenylase deletion strains. Although global poly(A) tail length increases in pan2∆ cells33, there was no significant difference in the length of the poly(A) tails observed on decapped urg1 cRACE products in pan2∆ cells compared with those from WT cells (p=0.24, two-tailed Mann Whitney test; Fig. 6b). These data suggest that an additional deadenylase has overlapping function with Pan2; this deadenylase is most likely the Ccr4-Caf1 complex as has been described in budding yeast26.

In contrast, poly(A) tails on decapped urg1 cRACE products from ccr4∆ cells were significantly longer than those from WT cells (p=0.002, one-tailed Mann Whitney; Fig. 6d). Some non-uridylated urg1 species contained poly(A) tails longer than 50 nt and indicate the presence of the deadenylation-independent decapping pathway described above (Fig. 1). While in WT cells a bi-modal distribution for poly(A) tail length was observed, the peak of shorter tails was lost in ccr4∆ cells (Fig. 6d), consistent with impaired deadenylation.

We analyzed uridylation in cells lacking components of deadenylase complexes (Fig. 6a). In contrast to WT cells, where 18% of decapped, adenylated urg1 products were uridylated, in ccr4∆ cells this figure rose to 53% (p=0.003). Interestingly, uridylation also increased in pan2∆ and pan3∆ cells. Terminal uridyl residues were observed on 44% of decapped, adenylated products from pan2∆ cells and on 50% from pan3∆ cells, a significant increase in comparison to WT cells (p=0.007 and p=0.005 respectively). We thus propose that uridylation and deadenylation function redundantly to stimulate mRNA decay.

Lsm1-7 mediates uridylation-dependent decapping

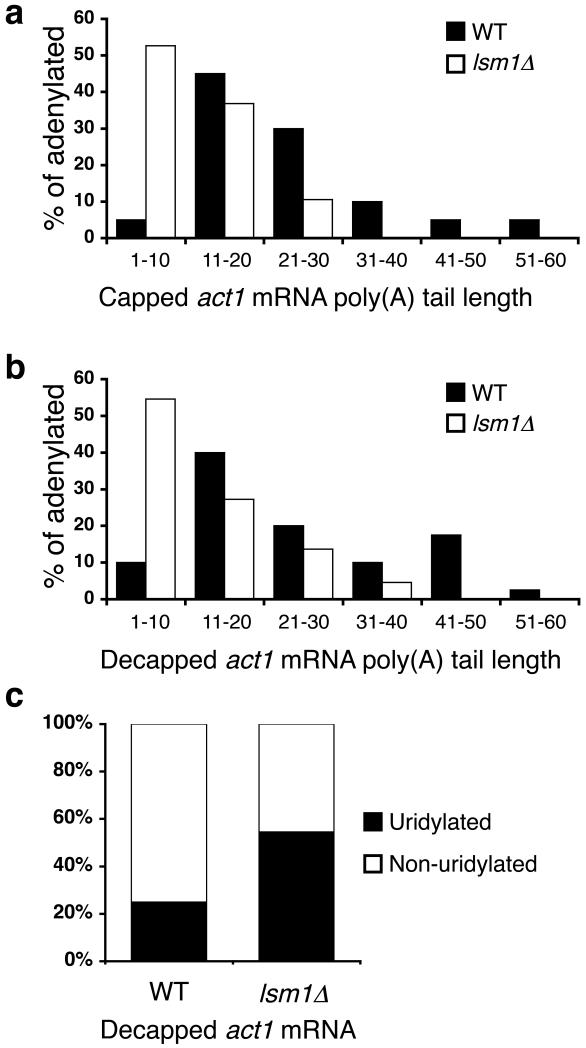

Previous reports have indicated that the Lsm1-7 complex not only enhances decapping in vivo but also is able to bind oligo(U) tracts in vitro to stimulate decapping34,35. Indeed, previous analysis has shown that the presence of a single terminal uridyl residue was sufficient to stimulate decapping significantly35. We therefore wondered whether the Lsm1-7 complex might mediate uridylation-dependent decapping. We performed act1 cRACE analysis on RNA isolated from lsm1∆ cells. As with dcp1-ts cells, poly(A) tails of capped and decapped act1 mRNAs from lsm1∆ cells were significantly shorter than those from WT cells (p=0.0002 and p=0.0004 respectively; Fig. 7a, b). This is consistent with previous observations in budding yeast that cells lacking Lsm1, like those lacking Dcp1, accumulate deadenylated, capped intermediates34.

Figure 7. Uridylation-mediated decapping requires Lsm1.

(a, b) Poly(A) tail lengths, binned into groups of ten nt, of capped (a) and decapped (b) act1 sequences isolated from WT [black; n=20 and 40 respectively] and lsm1∆ [white; n=19 and 22 respectively] cells are compared. (c) The percentage of decapped, adenylated act1 sequences that contain [black] or lack [white] terminal uridyl residues is compared for RNA isolated from WT and lsm1∆ cells.

Critically, in lsm1∆ cells, as with dcp1-ts cells, there was a significant accumulation of decapped, adenylated act1 messages that had been uridylated. While 25% were uridylated in WT cells, 55% were uridylated in lsm1∆ cells (p=0.01; Fig. 7c). There was no difference between uridylation of decapped act1 transcripts in lsm1∆ and dcp1-ts cells, however (p=0.33). Analysis of capped transcripts similarly suggested that uridylated, capped intermediates accumulate in lsm1∆ cells as they do in dcp1-ts cells (Supplementary Fig. 7 online). Consistent with previous analysis, urg1 transcripts were stabilized in lsm1∆ cells, in which the half-life was 41.3±3.3 minutes (p=0.0003; Supplementary Fig. 8 online). This half-life was significantly longer than that observed in cid1∆ or in ccr4∆ cells (p=0.0005 and p=0.006 respectively). Taken together, these data suggest that the Cid1-mediated mRNA decapping pathway involves the Lsm1 protein, and by extension the Lsm1-7 complex, downstream from the mRNA uridylation step. Moreover, as the Lsm1-7 complex is also known to mediate decapping after deadenylation34, we propose that this complex also acts downstream from Ccr4-mediated deadenylation, and thus stimulates decapping after either uridylation or deadenylation.

DISCUSSION

Uridylation of mRNAs and non-coding RNAs, such as U6 snRNA11, has been described in fission yeast and metazoans, but until now the significance of this modification for bulk, polyadenylated messages has been unclear. The recent observation that uridylation of replication-dependent histone mRNAs stimulates their decapping15 provided a valuable clue, but left open the question of whether this was a decay pathway specific for these non-polyadenylated messages. Metazoan replication-dependent histone mRNAs differ from other mRNAs in that they contain a 3′ stem-loop structure rather than a poly(A) tail16,36. This structure, bound by the stem-loop binding protein (SLBP), is responsible for the instability of these transcripts, which are degraded at the end of S phase16. While decay of these messages is dependent on both SLBP and Upf1, an important nonsense-mediated decay factor14,16, these proteins are not thought to be involved in general mRNA decay. Given such differences in these decay pathways, we wished to determine whether uridylation-stimulated decapping was histone-specific or whether uridylation formed the basis of a hitherto undiscovered pathway for bulk mRNA decay.

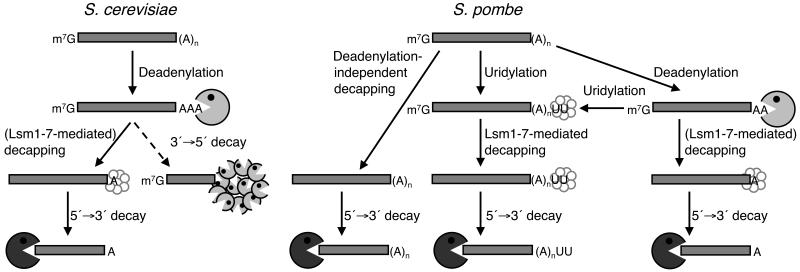

Here, we have identified two novel pathways for bulk mRNA decay in fission yeast, which act in parallel with the classical deadenylation-dependent pathway (Fig. 8). First, cytoplasmic uridylation, though absent from budding yeast (Supplementary Fig. 2 online), may be used in fission yeast to stimulate decapping and decay. A significant fraction of six functionally diverse transcripts, act1, adh1, gar2, hcn1, pof9 and urg1, were uridylated. It is important to note that the nature of this modification, typically one to two uridyl residues, precludes the use of genome-wide hybridization techniques, such as oligo(dA)-primed reverse transcription. Alternative strategies will be required to catalogue all of the transcripts affected by uridylation in fission yeast.

Figure 8. A comparison of decay pathways for bulk mRNA in S. cerevisiae and S. pombe.

See text for details.

In S. pombe, some transcripts are also subject to deadenylation- and uridylation-independent decapping. This stands in contrast to budding yeast, where decay is initiated by deadenylation to a tail shorter than 11 nt (Supplementary Fig. 2 online)1. This deadenylation-independent pathway in fission yeast may reflect similarities to mammalian systems: here, poly(A) tails are generally longer than in S. pombe and decapping can occur after initial deadenylation shortens the poly(A) tail to 30-60 nt6,27.

Uridylation is largely Cid1-dependent and precedes decapping (Fig. 8). Although we have captured rare non-adenylated products with (U)8 and (U)15 tails (OSR, unpublished data), the vast majority of uridylation on polyadenylated messages surprisingly involves only one or two uridyl residues. It is formally possible that long uridyl tails on polyadenylated messages were not observed due to an inability of RNA ligase to efficiently ligate poly(A)-oligo(U) hairpin structures. However, this seems unlikely for three reasons. First, we isolated several S. cerevisiae act1 cRACE products in which the cleavage site, GTA(U)5AA, was followed by an oligo(A) tail; this construct would also be able to form hairpin structures. Similarly, in our act1 HSC-RACE analysis on RNA from dcp1-ts cells, we were also able to isolate species with (A)8(U)4 and (A)10(U)4 tails. Taken together, these data suggest that the predominance of mono- and di-uridylation in WT cells does not result from any inability to ligate longer oligo(U) tails. Second, longer uridyl tails were also observed upon inhibition of decapping. Finally, no longer oligo(U) tails were identified when the RNA circularization step was performed at 65°C with a thermostable ligase (data not shown). Thus we suggest that on polyadenylated messages in vivo Cid1 may have distributive rather than processive polymerase activity. As only one or two uridyl residues were observed on the various decapped, polyadenylated transcripts analyzed in wild-type cells, longer oligo(U) tracts appear unnecessary for the mediation of decapping (see below). It is also possible that a highly efficient poly(U) exonuclease exists in S. pombe and that uridylation itself may be reversible.

Given that Dcp1 is required for viability in S. pombe21 while ski2∆ cells show few differences from WT cells (OSR, unpublished data), it appears that, as in budding yeast1, 5′→3′ mRNA decay is the major degradative pathway. However, in contrast to budding yeast, multiple redundant pathways are able to stimulate decapping. Importantly, urg1 mRNA was stabilized in cells lacking Cid1 (Fig. 6). The magnitude of stabilization observed in our study is similar to that seen in S. cerevisiae ccr4∆ cells26.

In addition, urg1 mRNA was also stabilized to a similar extent in ccr4∆ cells, indicating that Ccr4-Caf1 is the major cytoplasmic deadenylase in S. pombe. In contrast, the roles of Pan2 and PARN, additional deadenylases, appear to be minor during bulk mRNA decay as inactivation of either had no effect on urg1 mRNA stability (Fig. 6). It may be that the S. pombe Pan2-Pan3 complex has a role in nuclear trimming of poly(A) tails, as has been shown in budding yeast28,29, rather than a role in mRNA decay, as is the case in higher eukaryotes27,37, though this would not explain the observed increase in mRNA uridylation in pan2∆ and pan3∆ cells (Fig. 6a). Dissection of the specific roles of the Pan2-Pan3 complex and PARN is currently being pursued.

The cRACE analysis of urg1 mRNAs in cid1∆ and ccr4∆ cells strongly suggests that uridylation and deadenylation act redundantly. Although we found evidence for the existence of a second, minor uridylating enzyme, Cid1 was responsible for the majority of mRNA uridylation (Fig. 2, 6), and uridylation was significantly decreased in cid1∆ cells. Consistent with redundancy of uridylation and deadenylation, the poly(A) tails of decapped act1 and urg1 mRNAs were significantly shorter in these cells than in WT (Figs 2, 6). This difference specifically arises during mRNA decay as we observed no difference in poly(A) tail lengths on capped act1 messages from cid1∆ and WT cells. Conversely, in ccr4∆ cells, where deadenylation is impaired, uridylation of decapped, adenylated urg1 cRACE products significantly increased when compared to those from WT cells.

We suggest that decapping of uridylated mRNAs is mediated by Lsm1 (Fig. 5), and by extension the Lsm1-7 complex, which is a known enhancer of decapping34. Although we observed only one or two terminal uridyl residues in WT cells, we suggest that this modification may be recognized by the Lsm1-7 complex for two reasons. First, a recent study15 has shown that decapping of human replication-dependent histone mRNAs involves oligouridylation and is mediated by the Lsm1-7 complex. Second, an in vitro analysis of decapping supports this interpretation35. In this study, Song and Kiledjian demonstrated that even a single terminal uridyl residue was able to stimulate decapping in cellular extracts. These authors proposed that uridylation of act1 mRNA, which we had previously described9, might indeed trigger decapping mediated by the Lsm1-7 complex. Considering the cRACE analysis presented here (Fig. 7), we propose that the Lsm1-7 complex is responsible for recognizing even mono-uridylated transcripts and stimulating decapping in fission yeast.

The Lsm1-7 complex is known to localize to P-bodies38. While these cytoplasmic foci are sites of RNA decay, they have also been shown to store translationally repressed mRNAs32,38,39. Presumably, Lsm1-7 complex recruitment results in the localization of uridylated mRNAs to P bodies. It may be that, during times of cellular stress and/or for some transcripts, P body localization elicits translational repression, rather than mRNA decay.

It is likely that the Lsm1-7 complex is also involved in deadenylation-dependent decapping in fission yeast, as has been described in budding yeast34. Interestingly, S. pombe lsm1∆ cells, like dcp1-ts cells, display a slow growth phenotype, while those lacking Cid1 or cytoplasmic deadenylases do not (OSR, unpublished data). Moreover, in lsm1∆ cells urg1 mRNA was significantly stabilized in comparison with that in cid1∆ and ccr4∆ cells, consistent with the Lsm1-7 complex acting downstream of both uridylation and deadenylation. Although urg1 transcripts were not stabilized in cid1∆ccr4∆ cells, relative to either single deletion, this result may reflect overlapping deadenylase activities. Accordingly, it may be necessary to create various triple deletion strains, such as ccr4∆cid1∆pan2∆, in order to recapitulate the growth defect and extended urg1 half-life seen in lsm1∆ cells, in which decapping after both deadenylation and uridylation is inhibited.

Budding yeast lacks mRNA uridylation (Supplementary Fig. 2 online), and RNA decay in this organism principally occurs through deadenylation-dependent pathways2,18. Notably, however, given the observations of histone mRNA uridylation15, the described PUP/TUTase activities of the human Cid1-like enzymes9,10, and observations presented here, uridylation likely plays an important role in the decay of polyadenylated mRNA in higher eukaryotes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank David Bartel for his generous support. We also thank other members of the laboratory, Alison Woollard, Elmar Wahle and Nick Proudfoot for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript, as well as Toshiaki Katada (University of Tokyo) for providing various strains. This work was supported by Cancer Research UK and the Biotechnologies and Biological Sciences Research Council. OSR was supported by a scholarship from the Rhodes Trust.

Appendix

METHODS

Primers

All oligonucleotide sequences are shown in Supplementary Table 3.

Fission yeast strains and methods

The conditions for growth and maintenance were as described previously40. We made the lsm1∆ strain using oligonucleotides 5′ Lsm1 del and 3′ Lsm1 del as described41; similarly, we made the pan3∆ strain using oligonucleotides 5′ Pan3 del and 3′ Pan3 del. We checked integrations using the appropriate oligonucleotides (see Supplementary Table 3 online). S. pombe strains used in this study (Supplementary Table 4 online) were grown at 30° C, except dcp1-ts cells, which we grew at 28°C, in yeast extract medium with supplements (YE5S). We isolated RNA using a hot phenol method as described40.

cRACE analysis

We performed cRACE as described previously6. Briefly, to analyze capped messages, degradation intermediates were dephosphorylated with shrimp alkaline phosphatase (SAP, Roche), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. We extracted reactions with phenol/chloroform and then precipitated RNA with ethanol, resuspended pellets in dH2O and then decapped RNA with 2.5 units tobacco acid pyrophosphatase (TAP, Epicentre Biotechnologies). We incubated these reactions for 1 hr at 37°C and then ethanol precipitated the products. We then incubated 10 μg of this RNA overnight with 1 unit T4 RNA ligase (New England Biolabs) in a 400 μl reaction at room temperature and ethanol precipitated the products. To examine decapped RNAs, we ligated 10 μg RNA in a 400 μl reaction, as before, without pre-treating with SAP or TAP. We used one twentieth of the resuspended ligation products to make cDNA with Superscript II (Invitrogen), then PCR amplified one twentieth of the cDNA using divergent primers for 20-22 cycles. We performed a second, nested PCR with one fiftieth of products from the first PCR, again using 20-22 cycles. After TA-cloning the PCR products into pCR2.1 (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions, we then determined their sequences.

urg1 half-life analysis

We grew cells to mid-exponential phase in Edinburgh Minimal Medium (EMM) with the appropriate supplements and uracil at 0.25 mg ml-1 to induce urg1 expression. After washing cells three times in an equal volume of distilled water, we resuspended them in EMM with the appropriate supplements but without uracil to repress urg1 transcription. We then harvested cells at 0, 10, 20 and 30 minutes after repression and extracted RNA, which we separated by formaldehyde/1% agarose gel electrophoresis and transferred to Hybond N+ nylon membrane (Amersham) by capillary action. We then cross-linked RNA to the membrane using a UVC 500 Crosslinker (Stratagene). We amplified DNA probes for urg1 and pik1 from S. pombe genomic DNA and labeled them with [α-32P] dCTP (Perkin Elmer) using the Rediprime II™ kit (Amersham), according to manufacturer’s instructions. We hybridized probes to the membrane overnight at 60°C in ExpressHyb solution (Clontech) and then washed them according to manufacturer’s instructions. We exposed the membrane to a phosphor-screen (Molecular Dynamics), which we subsequently scanned using a FLA5000 Fuji phosphoimager. We analyzed images using AIDA™ software (Raytest GmbH), normalized the urg1 signal to the pik1 signal and then compared it to that at the 0 minute time point. We calculated half-lives using a semi-log plot and calculating the line of best fit (Microsoft Excel).

HSC-RACE analysis

We performed HSC-RACE as described previously9.

Statistical analysis

When identical sequences were obtained, we reasoned that these were likely due to PCR amplification and counted them only once. Except where noted in the text, we performed statistical analysis with a one-tailed Student’s t-test. For non-normal distributions, we instead used a one- or two-tailed Mann Whitney test.

REFERENCES

- 1.Decker CJ, Parker R. A turnover pathway for both stable and unstable mRNAs in yeast: evidence for a requirement for deadenylation. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1632–43. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.8.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muhlrad D, Decker CJ, Parker R. Deadenylation of the unstable mRNA encoded by the yeast MFA2 gene leads to decapping followed by 5′-->3′ digestion of the transcript. Genes Dev. 1994;8:855–66. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.7.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muhlrad D, Decker CJ, Parker R. Turnover mechanisms of the stable yeast PGK1 mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2145–56. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson JS, Parker RP. The 3′ to 5′ degradation of yeast mRNAs is a general mechanism for mRNA turnover that requires the SKI2 DEVH box protein and 3′ to 5′ exonucleases of the exosome complex. Embo J. 1998;17:1497–506. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shyu AB, Belasco JG, Greenberg ME. Two distinct destabilizing elements in the c-fos message trigger deadenylation as a first step in rapid mRNA decay. Genes Dev. 1991;5:221–31. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Couttet P, Fromont-Racine M, Steel D, Pictet R, Grange T. Messenger RNA deadenylylation precedes decapping in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:5628–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang SW, Norbury C, Harris AL, Toda T. Caffeine can override the S-M checkpoint in fission yeast. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:927–37. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.6.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang SW, Toda T, MacCallum R, Harris AL, Norbury C. Cid1, a fission yeast protein required for S-M checkpoint control when DNA polymerase delta or epsilon is inactivated. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:3234–44. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.9.3234-3244.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rissland OS, Mikulasova A, Norbury CJ. Efficient RNA polyuridylation by noncanonical poly(A) polymerases. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3612–24. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02209-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwak JE, Wickens M. A family of poly(U) polymerases. Rna. 2007;13:860–7. doi: 10.1261/rna.514007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trippe R, et al. Identification, cloning, and functional analysis of the human U6 snRNA-specific terminal uridylyl transferase. Rna. 2006;12:1494–504. doi: 10.1261/rna.87706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aravind L, Koonin EV. DNA polymerase beta-like nucleotidyltransferase superfamily: identification of three new families, classification and evolutionary history. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1609–18. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.7.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen B, Goodman HM. Uridine addition after microRNA-directed cleavage. Science. 2004;306:997. doi: 10.1126/science.1103521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaygun H, Marzluff WF. Regulated degradation of replication-dependent histone mRNAs requires both ATR and Upf1. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:794–800. doi: 10.1038/nsmb972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mullen TE, Marzluff WF. Degradation of histone mRNA requires oligouridylation followed by decapping and simultaneous degradation of the mRNA both 5′ to 3′ and 3′ to 5′. Genes Dev. 2008;22:50–65. doi: 10.1101/gad.1622708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pandey NB, Marzluff WF. The stem-loop structure at the 3′ end of histone mRNA is necessary and sufficient for regulation of histone mRNA stability. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:4557–9. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.12.4557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mertins P, Gallwitz D. A single intronless action gene in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe: nucleotide sequence and transcripts formed in homologous and heterologous yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:7369–79. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.18.7369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muhlrad D, Parker R. Mutations affecting stability and deadenylation of the yeast MFA2 transcript. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2100–11. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.11.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lackner DH, et al. A network of multiple regulatory layers shapes gene expression in fission yeast. Mol Cell. 2007;26:145–55. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rissland OS, Norbury CJ. The Cid1 poly(U) polymerase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1779:286–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakuno T, et al. Decapping reaction of mRNA requires Dcp1 in fission yeast: its characterization in different species from yeast to human. J Biochem. 2004;136:805–12. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvh190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.West S, Gromak N, Norbury CJ, Proudfoot NJ. Adenylation and exosome-mediated degradation of cotranscriptionally cleaved pre-messenger RNA in human cells. Mol Cell. 2006;21:437–43. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santiago TC, Purvis IJ, Bettany AJ, Brown AJ. The relationship between mRNA stability and length in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:8347–60. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.21.8347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watt S, et al. urg1: A Uracil-Regulatable Promoter System for Fission Yeast with Short Induction and Repression Times. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1428. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tucker M, Staples RR, Valencia-Sanchez MA, Muhlrad D, Parker R. Ccr4p is the catalytic subunit of a Ccr4p/Pop2p/Notp mRNA deadenylase complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Embo J. 2002;21:1427–36. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.6.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tucker M, et al. The transcription factor associated Ccr4 and Caf1 proteins are components of the major cytoplasmic mRNA deadenylase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell. 2001;104:377–86. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamashita A, et al. Concerted action of poly(A) nucleases and decapping enzyme in mammalian mRNA turnover. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:1054–63. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boeck R, et al. The yeast Pan2 protein is required for poly(A)-binding protein-stimulated poly(A)-nuclease activity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:432–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.1.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown CE, Tarun SZ, Jr., Boeck R, Sachs AB. PAN3 encodes a subunit of the Pab1p-dependent poly(A) nuclease in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5744–53. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai WS, Kennington EA, Blackshear PJ. Tristetraprolin and its family members can promote the cell-free deadenylation of AU-rich element-containing mRNAs by poly(A) ribonuclease. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:3798–812. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.11.3798-3812.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lejeune F, Li X, Maquat LE. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in mammalian cells involves decapping, deadenylating, and exonucleolytic activities. Mol Cell. 2003;12:675–87. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parker R, Song H. The enzymes and control of eukaryotic mRNA turnover. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:121–7. doi: 10.1038/nsmb724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takahashi S, Kontani K, Araki Y, Katada T. Caf1 regulates translocation of ribonucleotide reductase by releasing nucleoplasmic Spd1-Suc22 assembly. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:1187–97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tharun S, et al. Yeast Sm-like proteins function in mRNA decapping and decay. Nature. 2000;404:515–8. doi: 10.1038/35006676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song MG, Kiledjian M. 3′ Terminal oligo U-tract-mediated stimulation of decapping. Rna. 2007;13:2356–65. doi: 10.1261/rna.765807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marzluff WF. Metazoan replication-dependent histone mRNAs: a distinct set of RNA polymerase II transcripts. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:274–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng D, et al. Deadenylation is prerequisite for P-body formation and mRNA decay in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:89–101. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200801196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheth U, Parker R. Decapping and decay of messenger RNA occur in cytoplasmic processing bodies. Science. 2003;300:805–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1082320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brengues M, Teixeira D, Parker R. Movement of eukaryotic mRNAs between polysomes and cytoplasmic processing bodies. Science. 2005;310:486–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1115791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moreno S, Klar A, Nurse P. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:795–823. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94059-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bahler J, et al. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast. 1998;14:943–51. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<943::AID-YEA292>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.