Summary

Size-biased sampling arises when a positive-valued outcome variable is sampled with selection probability proportional to its size. In this article, we propose a semiparametric linear regression model to analyze size-biased outcomes. In our proposed model, the regression parameters of the covariates are of major interest, while the distribution of random errors is unspecified. Under the proposed model, we discover that the regression parameters are invariant regardless of size-biased sampling. Following this invariance property, we develop a simple estimation procedure for inferences. Our proposed methods are evaluated in simulation studies and applied to two real data analyses.

Keywords: Biased sampling, Linear Regression model, Log transformation, Size-biased probability of selection

1. Introduction

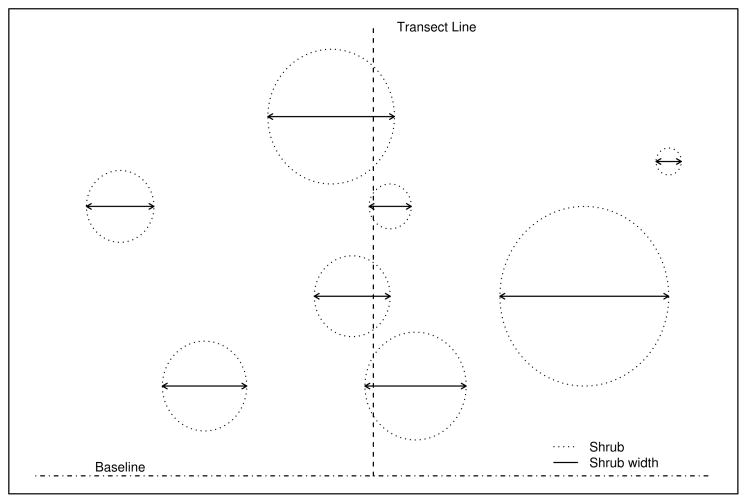

Muttlak (1988) presented a study to estimate vegetation coverage in an area of Laramie, Wyoming. This area was an old limestone quarry dominated by regrowth of mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus Montanus). As described in the study, a line-intercept sampling method (Canfield, 1941) was used: a straight baseline was first established, and then parallel transect lines were drawn perpendicular to the baseline. Those mountain mahogany shrubs intercepted by the transect lines were measured for their widths. See Figure 1 for an illustration. As shown in Figure 1, a shrub width is defined by the maximum distance between the shrub tangents that are parallel to the transect line. Apparently, shrub widths collected this way are not random samples, but subject to size-biased sampling, i.e., their probabilities of being sampled are proportional to the widths themselves. In statistical literature, this study has been a classical example to motivate methods development for size-biased sampling (Muttlak and McDonald, 1990; Jones, 1991; Wang, 1996).

Figure 1.

Schematic intercept sampling of shrub widths by one transect line

Size-biased sampling arises frequently in other studies as well, for example, when tumor size is measured in cancer screening trials to study tumor biology and progression (Kimmel and Flehinger, 1991). Because of lead-time bias in cancer screening trials, a tumor may be detected according to its individual size (Ghosh, 2008). More examples of size-biased sampling have been observed in industrial fiber testing (Cox, 1969), family studies of rare genetic diseases (Patil and Rao, 1978; Davidov and Zelen; 2001), etiological studies (Simon, 1980), and chronic/early disease modeling (Zelen, 2005).

In general, consider an outcome variable X > 0 with distribution function FX (x). When X is subject to size-biased sampling, its size-biased outcome, Y, then follows the distribution function of

where . Cox (1969) proposed a one-sample empirical estimator of FX(·) based on observed Y’s. Vardi (1982, 1985) later showed that it is indeed the nonparametric maximum likelihood estimator (NPMLE) of FX(·). A kernel density estimator by smoothing the NPMLE was developed in Jones (1991).

Usually, covariates, say Z, are also collected to study potential predictors or risk factors in association with X. In Muttlak (1988), information was collected on maximum shrub height and total number of shrub stems, both of which are important predictors to estimate the percentage of an area’s vegetation coverage. In Kimmel and Flehinger (1991), because tumors of local lesions may grow to shed cancer cells into the lymphatic system and/or blood stream, secondary cancers known as lymph-node or distant metastases may develop and lead to rapid disease progression or death. Therefore it is important to capture the association between tumor size and the metastasis status to understand the natural history of cancer progression. In fact, information was collected on tumor metastasis status and cancer types in Kimmel and Flehinger (1991). In either example, regression becomes an important tool to measure the association.

Parametric models can be used in regression. It is however important that the assumed parametric distributions are correctly specified, otherwise serious bias may arise in inferences (Duan, 1983). Nonparametric methods have been developed to estimate regression functions of size-biased outcomes. For example, the kernel estimator developed by Jones (1991) was extended to multivariate setting (Ahmad, 1995); Wu (2000) developed a class of local polynomial estimators; and Cristóbal and Alcalá (2000) proposed several regression function estimators by way of modified local polynomials. Since X tends to be positive, semiparametric proportional hazards models (Cox, 1972) have also been developed, for example, to model shrub width and tumor size in Wang (1996) and Ghosh (2008), respectively. In these models, regression parameters are based on hazard functions. When X is not time-to-event, such as shrub width or tumor size, regression models of X’s hazard functions are yet to be seen practical.

For general positive outcomes, a useful alternative to the semiparametric proportional hazards model is the log-linear regression model (Kalbfleisch and Prentice, 2002, p. 218). When X is time-to-event, it is the so-called accelerated failure time model (Wei, Ying and Lin, 1990). It is also a transformation model in Tsiatis (1990). In this article, we aim to develop a semiparametric version of this model in size-biased sampling. In the rest of this article, we first introduce a semiparametric linear model and its invariance property in size-biased sampling. Then we develop a simple estimation procedure for inferences on regression parameters. We assess our methods validity and performance by Monte-Carlo simulations, and further demonstrate it in actual data analysis.

2. The Method

2.1 A linear regression model

Let Z ∈ ℛp be the covariates vector associated with outcome variable X. Assume that the distribution of (X, Z) is determined by a joint density function of fX,Z(x, z). Consider the following linear regression model:

| (1) |

where β ∈ ℬ ⊂ ℛp is the regression parameter. Here, T denotes the transpose of a vector or a matrix. In this model, ξ = exp(ε) are assumed to have an unspecified density function of fξ( ·). Thus an equivalent form of model (1) is

| (2) |

where fξ(·) is nuisance parameter and β is the parameter of interest. Similar to the semiparametric proportional hazards model, such a semiparametric model formulation shall allow a wide range of error distributions.

Now consider a size-biased sampling indicator S, being 1 when X is selected and 0 otherwise, such that pr{S = 1 | X = x, Z = z} = pr{S = 1 | X = x} ∝ x. Note that this selection probability depends on X only. Then the size-biased density function becomes

| (3) |

which is identical to those in Cristóbal and Alcalá (2000) and Wu (2000). Furthermore, under the assumed log-linear regression model (1), we have

where and μξ = Eξ. As a result, the regression parameter β is invariant regardless of size-biased sampling (3), as summarized in the following property:

Property 1

Assume that there exists a random variable η = exp(ε) with the density function fη(·), where fη(y) = yfξ(y)/μξ. Under size-biased sampling, model (1) satisfies that

| (4) |

According to (4), the size-biased (X, Z), say (Y, Z), satisfies log Y = −βTZ + ε. Comparing it with (2), we find that (Y, Z) would follow a model almost identical to that of (X, Z) for the same β, except for the nuisance parameters. Property 1 is hence called an “invariance property” of model (1) in presence of size-biased sampling. An illustrative example is provided in the web supplementary materials.

2.2 Estimation and Inferences

In random sampling, a collected dataset would usually consist of n independent and identically distributed (iid) copies of (X, Z), (Xi, Zi), i = 1, 2, …, n. Then the likelihood function of β in model (1) would be proportional to

| (5) |

Now suppose that data are instead collected subject to size-biased sampling (3). That is, the actual collected data consist of n iid copies of {(X, Z) | S = 1}, {(Xi, Zi) | Si = 1}, i = 1, 2, …, n. Since under (3),

where  and

and  are the supports of X and Z, respectively, then by Property 1, the likelihood function becomes proportional to

are the supports of X and Z, respectively, then by Property 1, the likelihood function becomes proportional to

If fξ(·) is parametric, the usual maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) can be used to estimate β. Nevertheless, L1(β) and L2(β) are identical in β under the semiparametric model (1), regardless of size-biased sampling. For this reason, we hence aim at developing a semiparametric estimation procedures for β, without resort to any parametric form of fξ(·) or fη( ·)

To simplify our notations, we drop the notation S and denote the size-biased data by (Yi, Zi), i = 1, 2, …, n. Let λ(y) = −d log F̄(y)/dy denote a hazard function, where F̄(y) = 1 − F(y). By Property 1, it is true that

| (6) |

Let Ni(y) = I(Yi ≤ y) and Δi(y) = I(Yi ≥ y), i = 1, 2, …, n. Thus the score function for β based on (Yi, Zi) is

Apparently, because λη(·) is not specified and hence unknown, lβ( ·) cannot be used directly to solve for an estimator of β as in the usual MLE method.

For model (1), however, λη(·) itself is an infinite-dimensional nuisance parameter. To estimate β, we adapt a quasi partial estimating equation approach in Chen and Jewell (2001). This approach would first construct a consistent nonparametric estimator for λη(·), and then develop appropriate estimating functions to estimate β.

Suppose that β0 is the true value of β. Since ENi(y) = F(y | Zi), i = 1, 2, …, n, therefore

| (7) |

where F̄(y | Zi) = 1 − F(y | Zi) and . In addition, since , we consider the following unbiased estimating equation for Λη(·) when β = β0,

| (8) |

By solving (8) we obtain a nonparametric estimator for Λη( ·),

| (9) |

Let , i = 1, 2, …, n. Then { } are martingales with respect to the filtration defined by . As a result, Λ̂η(y; β0) is consistent, since . Moreover, by the Martingale Central Limit Theorem, n1/2{Λ̂η(y; β0) − Λη(y)} goes to a mean zero Gaussian process as n → ∞.

Similar to (7), we also notice that . Thus with the consistent estimator of Λ̂η( ·) obtained in (9), we propose to use the following estimating equations to estimate the regression parameter β,

| (10) |

to solve for β. By some algebraic manipulation, the above equations become equivalent to Un(β) = 0, where Un(β) = Un(∞; β), and

| (11) |

Here, Z̄(y; β) = ℰ(1)(y; β)/ℰ(0)(y; β) with , k = 0, 1, 2, where ⊗ is the Kronecker matrix product that defines v⊗0 = 1, v⊗1 = v and v⊗2 = vvT for a vector v. In general, because Un(β) is not a continuous function of β, a unique solution to the estimating equations in (11) may not always be plausible. We thus define a solution β̂n as a zero-crossing of Un(β) such that Un(β̂n −)Un(β̂n +) ≤ 0, as in Tsiatis (1990), or the minimizer of the Euclidean norm of ||Un(β)||, as in Wei, Ying and Lin (1990).

Assume that limn → ∞ ℰ(k)(y; β) = e(k)(y; β). We have the following asymptotic results:

Theorem 2

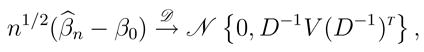

Under the regularity conditions specified in the Appendix, β̂n is consistent, and

|

where

Details of proof can be found in the web supplementary materials.

To apply the asymptotic results, we need to find consistent estimators for D−1V (D−1)T. A straightforward way is to find consistent estimators for V and D, respectively. For example, . For D, it is less straight-forward because of the unknown λη(·). One approach was suggested in Tsiatis (1990) by a smoothing kernel of λη(·). As pointed out by one reviewer, however, such an estimator is usually sensitive to the choice of smoothing parameter, although it may have less impact on the variance estimator of β̂n in the proposed semiparametric model. Other alternative approaches to estimating the asymptotic variance of β̂n may involve computer-intensive resampling to approximate the variance-covariance matrix, such as in Parzen, Wei and Ying (1994). A less computer-intensive sample-based algorithm can be used as well. See the web supplementary materials for details.

In addition to the estimation of regression parameter β, we may also be interested in estimating the distribution function of Fη(·) in model (6), and further the distribution function of Fξ(·) in model (1). In order to do so, for a given value of β, consider η̂i(β) = YieβTZi, i = 1, 2, …, n. By (6), an estimate for the distribution function Fη(·) is straightforward, which is simply the empirical distribution function based on η̂i(β)’s:

Moreover, according to Property 1, we know that . To estimate μξ, we consider the harmonic mean of η̂i(β) by Cox (1969),

Therefore, an estimate of Fξ(x) is

which is a weighted average of rescaled Ni(·)’s. Thus, Fη(·) and Fξ(·) can be estimated by F̂η( ·;β̂n) and F̂ξ(·;β̂n), respectively, where β̂n are the estimates obtained earlier. In fact, when β = 0, our proposed models reduce to a one-sample problem, and F̂ξ( ·; 0) becomes the exactly same NPMLE as studied in Vardi (1982).

Let Gη(y) = n1/2{F̂η(y; β̂) − Fη(y)}. Given the fact that Gη(y) = n1/2{F̂η(y; β̂) − F̂η(y; β0)}+ n1/2{F̂η(y; β0) − Fη(y)}, it is true that Gη( ·) converges weakly to a mean zero Gaussian process with covariance function of σ(y1, y2), similar to Theorem 8.3.3. of Fleming & Harrington (1991, p. 299). To construct a confidence interval of Fη(y), we consider the logit-transformation of F̂η(y; β̂). That is, a 95% confidence interval is

where

and

Here, σ̂(y, y) is an estimated standard error of G(y) and . Similar procedure can be applied to Gξ(y) = n1/2{F̂ξ(y; β̂) − Fξ(y)} to construct confidence intervals for Fξ(y).

Our proposed estimating functions can be extended to include more general weight functions, wn(y; β) say, with limn wn(y; β0) = w(y). Specifically, consider the weighted estimating equations for β:

| (12) |

Let

and

. Denote

the solution in (12). Under the assumed regularity conditions,

is consistent and

→

. The sample-based method can be similarly used to estimate the variance of

. In addition, by an application of Cauchy-Schwarz inequality, the optimal weight function for the weighted estimating functions in (12) should be proportional to

. It is indeed shown in Ritov (1990) that

of wopt(y) is the most efficient estimator among all of the semiparametric estimators under model (6). It is however yet to see a broader application of wopt(y) in practice given the challenge in its estimation.

. The sample-based method can be similarly used to estimate the variance of

. In addition, by an application of Cauchy-Schwarz inequality, the optimal weight function for the weighted estimating functions in (12) should be proportional to

. It is indeed shown in Ritov (1990) that

of wopt(y) is the most efficient estimator among all of the semiparametric estimators under model (6). It is however yet to see a broader application of wopt(y) in practice given the challenge in its estimation.

Another prominent choice of weight function is wg(y) = n−1 ΣiΔi(ye−βTZi) of the Gehan-type (Tsiatis, 1990), for which reduces to

Therefore, solving amounts to minimizing n−1 Σi,j min{log Yi − log Yj + βT(Zi − Zj), 0}. This minimization is achieved by a linear programming of maximizing Σi,j δij in β subject to δij ≤ min{log Yi − log Yj + βT(Zi − Zj), 0} (Koenker and Bassett, 1978). Denote the minimizer. Then is consistent and asymptotically normal (Jin et al., 2003), and can further assist to augment an algorithm for the general weighted estimating equations in (12). Specifically, consider the iterative algorithm proposed by Jin et al. (2003): ; in the kth step,

where w̄(β) = w(y; β)/wg(y; β). As k grows, β̂(k) is deemed to converge when ||β̂(k) − β̂(k−1)|| is less than a prespecified convergence criterion. In practice, this algorithm works sufficiently well by k = 3. To estimate the variance-covariance of , we can use the resampling approach developed in Rao and Zhao (1992), Parzen et al. (1994) and Jin et al. (2003). A computer software package called “rankreg” is available in R-language (http://cran.r-project.org/doc/packages/rankreg.pdf). Instruction and sample programs can be found in the package manual. This package generally works well with moderate sample sizes. However, it may be time-consuming and take up to 3–4 hours on a personal computer of 1G RAM to estiamte a model of 4 covariates, when sample size becomes 1,000.

One use of the weighted estimating equations is in model adequacy assessment. As proposed in Gill and Schumacher (1987) for the proportional hazards model, the rationale is that the estimates based on different weighted estimating equations should be reasonably close to each other if the assumptions of the proportional hazards model do hold, and should differ otherwise. This same rationale can be applied to the adequacy assessment of model (1). Specifically, consider the estimating equations in (12) for two different weight functions, wn,1(y) and wn,2(y) say. Their associated estimates of the regression parameter are and , respectively. Should model (1) be true, then a Wald-type of statistic based on is seemingly straightforward to use, given the asymptotic normality of similar to that in Lin (1991).

Due to the difficulty in estimating λη(·) and λξ(·) in the asymptotic variance of , however, we would instead use the method proposed in Wei, Ying and Lin (1990) to derive a goodness-of-fit test for model (1). That is, we consider , which is asymptotically joint normal with the variance-covariance matrix that is the limit of

where

and

Thus, the following statistic can be used in the goodness-of-fit assessment of model adequacy:

| (13) |

which is asymptotically -distributed as shown in Wei, Ying and Lin (1990).

3. Numerical Studies

3.1 Simulations

Simulation studies are conducted to assess both semiparametric methods and the MLE methods for the proposed linear regression model. In our simulations, we consider the linear regression model (1) of log X = −βTZ + ε, where two distributions are chosen for the random variable ε, i.e.,

a standard Normal distribution with the density function of (2π)−1/2 exp(−s2/2), and

an Extreme-value distribution with the density function of 2 exp(2s − e2s).

Hence for ξ = exp(ε), the density function fξ(·)’s are Log-normal (2π)−1/2s−1 exp{−(log s)2/2} and Weibull 2s exp(−s2), respectively. According to Property 1, for η = exp(ε) in log Y = −βTX + ε, then the respective density function fη( ·)’s are (2π)−1/2 exp{−(log s)2/2}/μL and 2s2 exp(−s2)/μW. Numerical integration shows that and .

In each simulation, we generate a sample of n iid copies of size-biased (Y, Z) according to the model of . Here, β0 is the true value of β, and Z are simulated according to a uniform distribution U[0, 1] and hence continuous. We use four methods to estimate β in model (1):

Para-L: MLE method with underlying Log-normal distribution,

Para-W: MLE method with underlying Weibull distribution,

Semi-L: semiparametric method with w(y) ≡ 1, and

Semi-G: semiparametric method with the Gehan weight function wg(·).

In particular, when the underlying distribution is Log-normal, Para-W represents an incorrect MLE method using the Weibull distribution. Similarly, when the underlying distribution is Weibull, Para-L represents an incorrect MLE method using the Log-normal distribution.

Simulation results are tabulated in Table 1. In this table, n is chosen to be 50, 200, and 500, representing small, moderate and large sample sizes, respectively. The true value β0 is chosen to be 0 and 1, representing the null and a specific alternative hypotheses, respectively. Each cell in the table is calculated with 10,000 simulated samples. A bias is calculated as the average of 10,000 (β̂ − β0)’s. A coverage probability is calculated as the percentage of 10,000 95% nominal confidence intervals (CI) containing β0. The sample standard error (SSE) of 10,000 β̂’s and the mean of 10,000 estimated standard errors (MSE) are also calculated.

Table 1.

Summary of simulation results on parametric and semiparametric estimation of β in model (1) of log X = −βTZ + ε.

|

fξ(·)†: Lognormal |

fξ(·)†: Weibull |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | n | Estimation‡ | Bias | 95% CP | SE | Mean SE | Bias | 95% CP | SE | Mean SE |

| 0 | 50 | Para-L | −0.0003 | 0.959 | 0.5031 | 0.5037 | 0.0092 | 0.831 | 0.3387 | 0.2437 |

| Para-W | 0.0123 | 0.853 | 0.6017 | 0.4911 | 0.0002 | 0.954 | 0.2297 | 0.2294 | ||

| Semi-L | 0.0006 | 0.951 | 0.7657 | 0.7651 | 0.0001 | 0.950 | 0.7899 | 0.7901 | ||

| Semi-G | 0.0002 | 0.955 | 0.6533 | 0.6534 | −0.0003 | 0.951 | 0.5084 | 0.5085 | ||

| 200 | Lognormal | 0.0002 | 0.945 | 0.2540 | 0.2539 | 0.0096 | 0.837 | 0.1779 | 0.1271 | |

| Weibull | 0.0125 | 0.859 | 0.3152 | 0.2436 | 0.0002 | 0.955 | 0.1096 | 0.1095 | ||

| Semi-L | 0.0003 | 0.947 | 0.3897 | 0.3899 | −0.0006 | 0.948 | 0.3973 | 0.3974 | ||

| Semi-G | 0.0004 | 0.952 | 0.3261 | 0.3261 | −0.0002 | 0.950 | 0.2603 | 0.2601 | ||

| 500 | Lognormal | −0.0001 | 0.949 | 0.1565 | 0.1564 | 0.0098 | 0.832 | 0.1195 | 0.0814 | |

| Weibull | 0.0121 | 0.857 | 0.2049 | 0.1537 | −0.0002 | 0.951 | 0.0716 | 0.0718 | ||

| Semi-L | 0.0002 | 0.950 | 0.2504 | 0.2503 | −0.0002 | 0.950 | 0.2472 | 0.2470 | ||

| Semi-G | −0.0001 | 0.950 | 0.2477 | 0.2479 | −0.0003 | 0.949 | 0.1619 | 0.1619 | ||

| 1 | 50 | Lognormal | −0.0045 | 0.942 | 0.5023 | 0.5021 | 0.0091 | 0.831 | 0.3391 | 0.2471 |

| Weibull | 0.0122 | 0.851 | 0.6297 | 0.4731 | −0.0001 | 0.947 | 0.2348 | 0.2347 | ||

| Semi-L | 0.0005 | 0.951 | 0.5451 | 0.5453 | −0.0007 | 0.952 | 0.5411 | 0.5409 | ||

| Semi-G | −0.0002 | 0.954 | 0.5227 | 0.5225 | 0.0001 | 0.951 | 0.4603 | 0.4605 | ||

| 200 | Lognormal | 0.0002 | 0.951 | 0.2511 | 0.2510 | 0.0093 | 0.830 | 0.1903 | 0.1275 | |

| Weibull | 0.0120 | 0.856 | 0.3111 | 0.2419 | −0.0005 | 0.951 | 0.1198 | 0.1198 | ||

| Semi-L | 0.0009 | 0.950 | 0.2751 | 0.2750 | −0.0001 | 0.951 | 0.2755 | 0.2754 | ||

| Semi-G | −0.0003 | 0.951 | 0.2603 | 0.2602 | −0.0001 | 0.949 | 0.2443 | 0.2445 | ||

| 500 | Lognormal | −0.0000 | 0.951 | 0.1628 | 0.1627 | 0.0096 | 0.833 | 0.1168 | 0.0809 | |

| Weibull | 0.0124 | 0.852 | 0.2081 | 0.1541 | 0.0003 | 0.950 | 0.0716 | 0.0716 | ||

| Semi-L | −0.0001 | 0.949 | 0.1689 | 0.1690 | 0.0001 | 0.949 | 0.1697 | 0.1698 | ||

| Semi-G | 0.0002 | 0.951 | 0.1654 | 0.1653 | −0.0000 | 0.951 | 0.1447 | 0.1448 | ||

fξ(·): true density function of ξ = exp(ε)

Estimation: Para-L, parametric estimation using Lognormal distribution; Para-W, parametric estimation using Weibull distribution; Semi-L, semiparametric estimation without weight function; Semi-G, semiparametric estimation using Gehan weight function

As shown in Table 1, the bias of β̂ for each method in this simulation setup is mostly close to zero, even though the MLE methods may specify incorrect underlying distributions for fξ( ·). The coverage probabilities for a correct Para-L or Para-W, i.e., an MLE method with correctly assumed underlying distributions, and Semi-L or Semi-W are generally close to the nominal level of 95%, while an incorrect Para-L or Para-W deviates from 95% notably. Similarly, the SSE and MSE are generally close to each other when the correct MLE methods and the semiparametric methods are used, but otherwise for the incorrect MLE methods.

As far as the semiparametric methods and the correct MLE methods are compared, the correct MLE methods generally yield smaller SSE and MSE, which means the semiparametric methods are yet to be fully efficient. As shown in the table, however, the efficiency of semiparametric methods may be potentially improved by choosing different weight functions. For example in the current simulation setup, the Gehan weight function may yield smaller variances, compared with those of wg(·) ≡ 1. As a summary, the correct MLE methods generally outperform the semiparametric methods. The validity of MLE methods however depend on whether or not the assumptions are correct. The semiparametric methods are generally more reliable with respect to different underlying distributions. Their efficiencies may be improved by choosing appropriate weight functions.

3.2 Real data examples

In this section, we use our proposed methods to analyze the real data examples that are introduced in §1: one is the classical dataset of shrub widths in Muttlak (1988), and the other is the tumor size dataset in Kimmel and Flehinger (1991). To save space, we present major analysis results in this article.

Example 1

The original dataset of shrub widths contains data on 89 shrub samples. In addition to the measurement of shrub widths (Width), two more attributes of mountain mahogany, maximum height (Height) and number of stems (Stem), were measured. Both attributes are important predictors of shrub width in estimating vegetation coverage of mountain mahogany. To ensure uniform coverage over the study area, two independent replications (Replicate), each with three systematically placed parallel transects (Transect), were established (Muttlak, 1988).

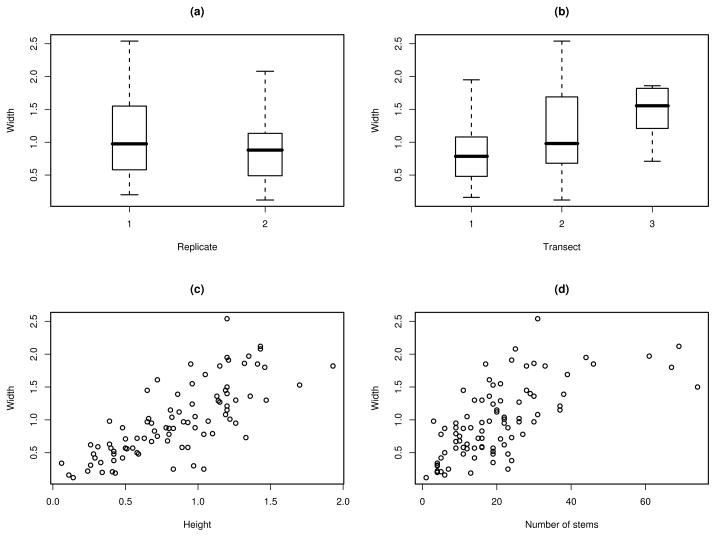

As shown in the scatter plots of Figure 2, when either attribute of Height or Stem increases, Width tends to increase. There appears, however, a quadratic relationship between Width and Stem. It is plausible that there may exist systematic deviation in Replicate and Transect. As shown in the boxplots of Figure 2, there appears some distributional difference in Width between different Replicates, although this difference is not seemingly prominent. There also appear distributional differences in Width between Transects I and II, and between Transects I and III. Some univariate summary statistics of the outcome variable and four covariates are in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Exploratory plots of shrub data: (a) boxplot of Width by Replicate; (b) boxplot of Width by Transect; (c) scatter plot of Width versus Height; (d) scatter plot of Width versus Stem

Table 2.

Summary statistics for shrub widths data

| Variable | Mean† | Min. | 25%-tile | Median | 75%-tile | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Width | 0.98 | 0.12 | 0.57 | 0.88 | 1.36 | 2.54 | |

| Replicate | 1 | 51.69% | |||||

| 2 | 48.31% | ||||||

| Transect | I | 56.18% | |||||

| II | 37.08% | ||||||

| III | 6.73% | ||||||

| Height | 0.84 | 0.06 | 0.50 | 0.83 | 1.19 | 1.93 | |

| Stem | 20.42 | 1.00 | 11.00 | 19.00 | 26.00 | 74.00 |

Mean, sample mean for continuous variables and frequency percentage for categorical variables

To examine the association between Width and the two attributes adjusting for Replicate and Transect, we consider a linear regression model log X = −βTZ + ε, where X is the outcome variable Width, and Z is the covariate vector including Height, Stem, Replicate and Transect, in regression analysis. Estimates of regression parameters are tabulated in Table 3. As shown in the table, all four methods, i.e., Para-L, Para-W, Semi-L and Semi-W, yield that Height and Stem are significant predictors, adjusting for Replicate and Transect, by their 95% confidence intervals (CI). This implies that taller shrubs with more stems are associated with greater width spread and hence more vegetation coverage, and per unit increase in Height and Stem would lead to about 118% and 2.5% increase in Width, respectively.

Table 3.

Parametric and semiparametric estimation of β in model (1) of log X = −βTZ + ε for shrub widths data

| Covariate | Est. | SE | 95% CI | Est. | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Para-L | Para-W | |||||

| Replicate | 0.0701 | 0.0949 | (−0.1159, 0.2562) | −0.0100 | 0.0814 | (−0.1697, 0.1496) |

| Transect I | ||||||

| Transect II | −0.0341 | 0.0987 | (−0.2276, 0.1593) | −0.0531 | 0.0849 | (−0.2195, 0.1132) |

| Transect III | −0.0238 | 0.1930 | (−0.4021, 0.3545) | 0.2056 | 0.1533 | (−0.0951, 0.5062) |

| Height | −0.9993 | 0.1280 | (−1.2501, 0.7484) | −0.8895 | 0.1233 | (−1.1313, −0.6478) |

| Stem | −0.0131 | 0.0038 | (−0.0206, −0.0056) | −0.0115 | 0.0038 | (−0.0190, −0.0040) |

| Semi-L | Semi-G | |||||

| Replicate | −0.0240 | 0.0804 | (−0.1817, 0.1337) | −0.0600 | 0.0814 | (−0.2175, 0.0976) |

| Transect I | ||||||

| Transect II | −0.0758 | 0.0953 | (−0.2625, 0.1110) | −0.0652 | 0.0849 | (−0.2520, 0.1216) |

| Transect III | −0.1719 | 0.2054 | (−0.5744, 0.2306) | −0.1608 | 0.1533 | (−0.5634, 0.2418) |

| Height | −0.8132 | 0.1336 | (−1.0751, −0.5514) | −0.7485 | 0.0904 | (−1.0103, −0.4866) |

| Stem | −0.0142 | 0.0042 | (−0.0226, −0.0059) | −0.0146 | 0.0028 | (−0.0228, −0.0064) |

For the seemingly quadratic association with Stem, we include an additional squared Stem in the model, and find that Width is not significantly associated with the added quadratic term. It is however still significantly associated with Height and Stem, with or without Replicate and Transect. Applying the goodness-of-fit test in (13) to the model with all covariates, we obtain T = 9.13 ~ χ2(p = 0.10, df = 5), which does not reject the models adequacy.

Example 2

In Kimmel and Flehinger (1991), a lung cancer dataset was used to examine the relationship between the occurrence of metastases and the size of primary cancers. In the dataset, lung cancers were diagnosed in a population of male smokers over 45 years old who enrolled voluntarily in a randomly controlled trial to evaluate the use of sputum cytology. Two types of lung cancer were detected: adenocarcinomas by radiologic screening or patients symptoms, and epidermoid cancers by sputum cytology, chest X-ray or patients symptoms. The diagnosis of metastases was based on the then best available staging, clinical, surgical, or pathological readings. Among the total 228 patients, there were 141 adenocarcinomas and 87 epidermoid cancers. Tumor sizes were determined by the geometric means of recorded dimensions: resected cancers were measured directly, and nonresected cancers were mainly measured on radiography. More descriptive details can be found in Ghosh (2008).

As pointed out in Ghosh (2008), a complication in analyzing tumor size in this dataset is the presence of size-biased sampling, i.e., tumors detected in the screening program tend to depend on their growth and hence the sizes themselves. In Ghosh (2008), tumor sizes were treated as time-to-event variables. Their hazard functions were modeled by the proportional hazards model. Therefore, the regression parameters would be interpreted in relative risk of tumor sizes. Additional summary statistics and exploratory analysis results of this dataset can be found in Ghosh (2008).

To examine the association between tumor size and the occurrence of metastases in size-biased sampling, we consider the proposed linear regression model. We first fit a linear regression model with the presence/absence of metastases only. The regression parameter estimate of β̂ equals 0.45 with a 95% CI (0.12, 0.78). This means that tumor size is about 56% significantly greater in presence of metastases. However, when including the cancer types of adenocarcinomas and epidermoid in the model, β̂ becomes 0.24 with a 95% CI (−0.07, 0.57), which is not statistically significant. On the other hand, the regression parameter estimate for cancer types is 0.65 with a 95% CI (0.45, 0.86). This implies that tumor size tends to be 91% greater in epidermoid cancers than that in adenocarcinomas. Our finding is consistent with the relative risk calculation in Ghosh (2008), although larger sample size may be needed to confirm a significant positive association in relative risk. Applying the goodness-of-fit test in (13) to the model with both covariates, we obtain T = 4.97 ~ χ2(p = 0.08, df = 2), which does not reject the models adequacy, either.

4. Discussion

Our proposed regression model is essentially a semiparametric linear model. In the statistical literature, semiparametric linear models have been extensively studied. For example, the accelerated failure time model is a classical example of semiparametric linear model in time-to-event analysis (Kalbfleisch and Prentice, 2002, p. 218). Additional examples include semiparametric linear models in curve regression analysis (Hardle and Marron, 1990), generalized linear regression (Chen, 1995) and partial linear regression (Bhattacharya and Zhao, 1997).

One prominent assumption in our proposed model is the choice of log-transformation. Because outcomes in size-biased sampling are mostly positive, a log-transformation would relax the restriction on β to allow a wide range of covariates Z. In addition, for log-transformed X, our proposed model essentially assumes a multiplicative association between X and Z. It is the multiplicative association that leads to the critical invariance property, which greatly simplifies our estimation. Other transformations, such as identity, are yet to be seen to have these advantages.

However, our proposed model can be generalized to, for example, log X = h(X, β) + ε for some function h(X, β). Under this generalized model, the invariance property still holds in size-biased sampling. This shall lead to further work. Specifically, an alternative class of regression models can assume that

where h(·) is unknown, but ε follows a known distribution, such as a standard Normal distribution, to avoid potential identifiability issue. This model shall further relax model assumptions and assist with model adequacy assessment.

As pointed by an Associate Editor, the use of hazard functions for outcomes other than censored time-to-event seems unnatural. This is in fact why semiparametric linear regression model may be more appealing to model outcomes, such as shrub width or tumor size, than the usual proportional hazards model. Nevertheless, we extensively use (cumulative) hazards functions in this manuscript to develop our estimation procedure, because of the simple representation of baseline cumulative hazard function in (9). This simple representation ultimately facilitates a straightforward estimation of β. The advantage of hazard functions is also seen in developing the asymptotic theory of Theorem 2. Otherwise the expression of D would be more complex.

When X is time-to-event, regression models based on hazard functions are appealing. When time-to-event is size-biased, it is usually called length-biased. Researchers have been studying censored length-biased time-to-event in the statistical literature. For example, Vardi (1989) estimated the lifetime distribution under multiplicative censorship; Asgharian, M’Lan and Wolfson (2002) developed an unconditional approach to studying length-biased lifetimes; and a recent work by Cristóbal, Alcalá and Ojeda (2007) proposed some nonparametric estimation from backward recurrence times. More work is needed to extend the proposed linear regression model to censored time-to-event.

5. Supplementary Materials

Details of those referenced in Section 2 are available in the web supplementary materials under the Paper Information link at the Biometrics web site http://www.tibs.org/biometrics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank an Associate Editor and two reviewers for their constructive comments, and also thank Professor Debashis Ghosh for his references to an earlier work and the tumor size dataset. This research is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health grants.

References

- Ahmad IA. On multivariate kernel estimation for samples from weighted distributions. Statistics & Probability Letters. 1995;22:121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Asgharian M, M’Lan CE, Wolfson DB. Length-biased sampling with right censoring: An unconditional approach. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2002;97:201–209. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya PK, Zhao PL. Semiparametric inference in a partial linear model. Annals of Statistics. 1997;25:244–262. [Google Scholar]

- Canfield RH. Application of the line intercept method in sampling range vegetation. Journal of Forestry. 1941;39:388–394. [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. Asymptotically efficient estimation in semiparametric generalized linear models. Annals of Statistics. 1995;23:1102–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Chen YQ, Jewell NP. On a general class of hazards regression models. Biometrika. 2001;88:687–702. [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR. Some sampling problems in technology. In: Johnson NL, Smith H H, editors. New Developments in Survey Sampling. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1969. pp. 506–527. [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables (with discussion) Journal of Royal Statistical Society Series B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Cristóbal JA, Alcalá JT. Nonparametric regression estimators for length biased data. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inferences. 2000;89:145–168. [Google Scholar]

- Cristóbal JA, Alcalá JT, Ojeda JL. Nonparametric estimation of a regression function from backward recurrence times in a cross-sectional sampling. Lifetime Data Analysis. 2007;13:273–293. doi: 10.1007/s10985-007-9033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidov O, Zelen M. Referent sampling, family history and relative risk: the role of length-biased sampling. Biostatistics. 2001;2:173–181. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/2.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan N. Smearing estimate: A nonparametric retransformation methods. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1983;78:605–610. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming TR, Harrington DP. Counting Processes and Survival Analysis. New York: Wiley; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh D. Proportional hazards regression for cancer studies. Biometrics. 2008;64:141–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill RD, Schumacher M. A simple test of the proportional hazards assumption. Biometrika. 1987;74:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Hardle W, Marron JS. Semiparametric comparison of regression curves. Annals of Statistics. 1990;18:63–89. [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z, Lin DY, Wei LJ, Ying Z. Rank-based inference for the accelerated failure time model. Biometrika. 2003;90:341–353. [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z, Ying Z, Wei LJ. A simple resampling method by perturbing the minimand. Biometrika. 2001;88:381–390. [Google Scholar]

- Jones MC. Kernel density estimation for length biased data. Biometrika. 1991;78:511–519. [Google Scholar]

- Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. 2. New York: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel M, Flehinger BJ. Nonparametric estimation of size-metastasis relationship in solid cancers. Biometrics. 1991;47:987–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenker R, Bassett GS. Regression quantiles. Econometrica. 1978;46:33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lin DY. Goodness of fit for the Cox regression model based on a class of parameter estimators. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1991;86:725–728. [Google Scholar]

- Muttlak HA. Ph.D. Dissertation. Laramie: University of Wyoming; 1988. Some Aspects of Ranked Set Sampling with Size Biased Probability of Selection. [Google Scholar]

- Muttlak HA, McDonald LL. Ranked set sampling with size-based probability of selection. Biometrics. 1990;46:435–446. [Google Scholar]

- Parzen MI, Wei LJ, Ying Z. A resampling method based on pivotal estimating functions. Biometrika. 1994;81:341–350. [Google Scholar]

- Patil GP, Rao CR. Weighted distributions and size-based sampling with applications to wildlife populations and human families. Biometrics. 1978;34:179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Rao CR, Zhao LC. Approximation to the distribution of M-estimates in linear models by randomly weighted bootstrap. Sankhyâ A. 1992;54:323–331. [Google Scholar]

- Ritov Y. Estimation in a linear regression model with censored data. Annals of Statistics. 1990;18:303–328. [Google Scholar]

- Simon R. Length biased sampling in etiologic studies. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1980;111:444–452. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiatis AA. Estimating regression parameter using linear rank tests for censored data. Annals of Statistics. 1990;18:354–372. [Google Scholar]

- Vardi Y. Nonparametric estimation in the presence of length bias. Annals of Statistics. 1982;10:616–620. [Google Scholar]

- Vardi Y. Empirical distributions in selection bias models. Annals of Statistics. 1985;13:178–203. [Google Scholar]

- Vardi Y. Multiplicative censoring, renewal processes, deconvolution and decreasing density: Nonparametric estimation. Biometrika. 1989;76:751–761. [Google Scholar]

- Wang MC. Hazards regression analysis for length-biased data. Biometrika. 1996;83:343–354. [Google Scholar]

- Wei LJ, Ying Z, Lin DY. Linear regression analysis of censored survival data based on rank tests. Biometrika. 1990;77:845–851. [Google Scholar]

- Wu CO. Local polynomial regression with selection biased data. Statistica Sinica. 2000;10:789–817. [Google Scholar]

- Zelen M. Forward and backward recurrence times and length biased sampling: age specific models. Lifetime Data Analysis. 2005;10:325–334. doi: 10.1007/s10985-004-4770-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.