SUMMARY

Perhaps 5 to 10% of proteins bind to the membranes via a covalently attached lipid. Post-translational attachment of fatty acids such as myristate occurs on a variety of viral and cellular proteins. High-resolution information about the nature of lipidated proteins is remarkably sparse, often because of solubility problems caused by the exposed fatty acids. Reverse micelle encapsulation is used here to study two myristoylated proteins in their lipid-extruded states: myristoylated recoverin, which is a switch in the Ca+2 signaling pathway in vision and the myristoylated HIV-1 matrix protein, which is postulated to be targeted to the plasma membrane through its binding to phosphatidylinositol(4,5)bisphosphate. Both proteins have been successfully encapsulated in the lipid extruded state and high-resolution NMR spectra obtained. Both proteins bind their activating ligands in the reverse micelle. This approach seems broadly applicable to membrane proteins with exposed fatty acid chains that have eluded structural characterization by conventional approaches.

INTRODUCTION

Covalent attachment of fatty acids such as myristate and palmitate occurs on a wide variety of viral and cellular proteins (Resh, 1999). Myristate, a fourteen carbon saturated fatty acid, and palmitate, a sixteen carbon saturated fatty acid, commonly serve as key elements of membrane targeting and anchoring of proteins. Reversible membrane binding, controlled through triggered exposure of lipid anchors, is central to protein-protein interactions mediating signal transduction at the membrane (Casey, 1995). Lipid anchors are also now thought to be critical to the exit of viruses from the eukaryotic cell (Maurer-Stroh and Eisenhaber, 2004). For example, the coupled interaction of fatty acids covalently attached to the HIV matrix protein with the membrane and phosphoinositides embedded in target membranes is thought to be central to its localization to the plasma membrane which in turn begins the assembly of the immature virus (Ono et al., 2004; Saad et al., 2006). Accordingly, this initiation of virion assembly is argued to be a prime candidate for pharmaceutical intervention (Lindwasser and Resh, 2002). Structural knowledge of this process would be of obvious utility. However, detailed characterization of the structural features of the myristoylated matrix protein, both by itself and in complex with PIP2 has been frustrated by the poor solution properties of both the protein and PI(4,5)P2 (PIP2) (Saad et al., 2006). Often what is done is to simply remove the portion of the protein that carries the lipid anchor leaving a highly soluble and well-behaved protein. This, however, obviously precludes examination of the role of the anchor itself and the interaction of the anchored protein with molecules presented by the membrane. A review of the PDB reveals that high-resolution information about the nature of lipidated proteins is remarkably sparse perhaps because of this inherent difficulty. The classic and, one might argue, only structurally well-defined lipid anchor switch is that of recoverin which shows a calcium dependent exposure of a modified myristoyl group (Ames et al., 1997; Tanaka et al., 1995). Recoverin (+myr) is a membrane associated protein that reacts to the influx of Ca+2 to extrude the hydrophobic myristoyl chain into the rod outer segment (ROS) membranes. The structural characterization of myristoylated recoverin in the Ca+2 saturated state has also proved elusive due to the limitations imposed by aggregation.

In an effort to overcome many of the difficulties presented by the poor solution behavior of lipidated proteins in the membrane-anchored state, we have adapted the reverse micelle as a surrogate for the membrane bilayer in order to enable high-resolution structural studies by solution NMR methods. Over the past decade there has been significant progress in the preparation of soluble protein molecules encapsulated within the protective water core of a reverse micelle dissolved in a low viscosity solvent such as the liquid alkanes (Peterson et al., 2005a; Peterson et al., 2005c; Wand et al., 1998). The low viscosity solvent allows for sufficiently fast tumbling of the reverse micelle particle to significantly improve the NMR relaxation properties of the protein (Peterson et al., 2005a; Wand et al., 1998). This new approach is illustrated with the two myristoylated proteins discussed above: recoverin(+myr) and the HIV-1 matrix protein, MA(+myr). Both proteins have been successfully encapsulated in the lipid extruded state and high-resolution NMR spectra obtained. Both proteins can be directly titrated with their natural activating ligands in the reverse micelle and their interactions followed by high-resolution NMR. In the case of the HIV-1 matrix protein, chemical shift mapping identifies the location of the PIP2 binding site.

RESULTS

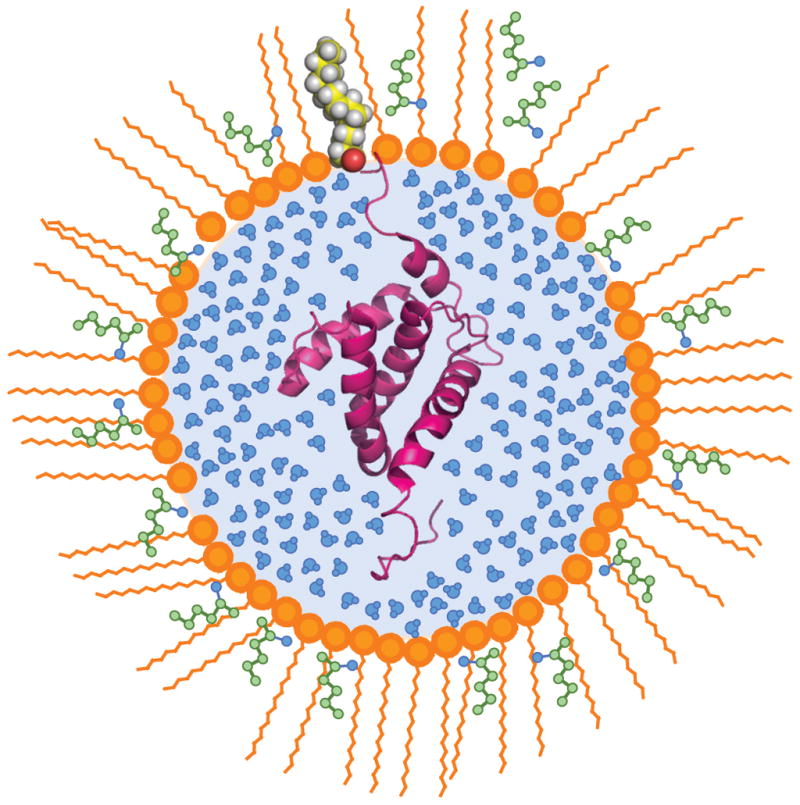

Encapsulation of myristoylated proteins within a surfactant system solvated in an alkane solvent proceeded as suggested by encapsulation protocols for water-soluble proteins (Babu et al., 2003; Lefebvre et al., 2005; Peterson et al., 2005c; Shi et al., 2005; Wand et al., 1998). The caveat for recoverin(+myr) and the HIV-1 MA(+myr) protein is the behavior of the hydrophobic myristoylate anchor. In free aqueous solution, both proteins show ligand-dependent exposure of the covalently attached myristoyl group, which generally complicates the solution behavior of both proteins in the putative membrane anchored state where the myristoyl group is extruded. The binding of calcium to recoverin(+myr) results in exposure of the otherwise buried myristoyl group (Ames et al., 1997; Ames et al., 1995; Tanaka et al., 1995). Similarly, the specific binding of PI(4,5)P2 to the HIV-1 matrix protein results in extrusion of the largely sequestered myristoyl group (Saad et al., 2006). It is predicted that the reverse micelle surfactant shell will provide a solubilizing environment for the myristoyl group and will therefore compete with the hydrophobic interior of the soluble protein for the lipid group, even in the absence of the ligand (Figure 1). This is indeed the case for both proteins.

Figure 1. Reverse micelle encapsulation of lipidated proteins for solution NMR.

Schematic illustration of the structure of a reverse micelle surfactant assembly hosting a lipidated protein. A ribbon representation of the NMR structure of HIV-1 MA (-myr) (Doyle et al., 1998) is shown. The surfactant CTAB (orange) co-solubilizes with hexanol (green) to form the reverse micelle shell. The myristoylated protein HIV-1 MA inserts into the aqueous interior with the acyl chain extruded into the hydrophobic surfactants. The reverse micelle particle is solvated in a compatible low viscosity solvent such as the short chain alkanes (Wand et al., 1998). This sample is designed to avoid the poor solution behavior of lipidated proteins that often defeats detailed solution NMR studies.

Encapsulation of recoverin (+myr)

We were unable to find conditions for direct encapsulation of calcium-saturated recoverin(+myr), perhaps because Ca2+-bound recoverin in solution tends to pre-aggregate which might prevent subsequent encapsulation. In the absence of calcium in free solution, the myristoyl tail is sequestered and the protein is well-behaved. The maximum concentration tolerated was ~ 2mM before aggregation of the myristoylated protein was evident. The identification of optimal encapsulation conditions for recoverin(+myr) began with the selection of the CTAB/hexanol surfactant system (Lefebvre et al., 2005) as the most probable success for a myristoylated protein with an acidic pI of 5.3. The preliminary results indicated mixed states of the encapsulated recoverin(+myr), likely resulting from myristoyl extruded and myristoyl sequestered forms. The aqueous protein buffer conditions were modified to include 1 mM EGTA to insure removal of any free Ca+2 ions from the solution thereby selecting the myristoyl sequestered state and limiting any protein aggregation. The concentration of NaCl was increased to 100 mM to further reduce the propensity to aggregate at the high protein concentration used. Encapsulation of the protein in this buffer system into CTAB/hexanol reverse micelles resulted in a largely disordered state (Figure 2). The spectrum is characterized by broad cross peaks of extremely low intensity, indicative of a dynamic equilibrium of a mixture of states that undergo exchange on the chemical shift time scale. Addition of Ca2+ to the encapsulated recoverin by direct injection of a concentrated solution of calcium results in a more homogeneous protein state apparently due to stabilization by the binding of Ca2+ to the protein (Figure 2). There is no evidence of aggregation in the reverse micelle encapsulated state of the Ca2+ bound recoverin(+myr). Final optimizations were directed at maximizing protein concentration in the reverse micelle. Surfactant concentration, aqueous solution protein concentration and water loading are the adjustable parameters. The total reverse micelle assembly size (correlation time) is also a consideration for spectroscopic success. The best signal-to-noise spectra were obtained with 200 mM CTAB, a starting protein concentration of 2.2 mM and a water loading, Wo, of 25. The resulting protein concentration in the reverse micelle solution was 180 μM recoverin(+myr). The pentane solution of encapsulated calcium-saturated recoverin is stable for months at room temperature. Other surfactant systems examined included the triple surfactant system LDAO: C12E4 : AOT ((Peterson et al., 2005c). This surfactant system was successfully applied to the encapsulation of flavodoxin (Valentine et al. 2007), which also has a low pI, but failed to successfully encapsulate recoverin(+myr) in a folded state.

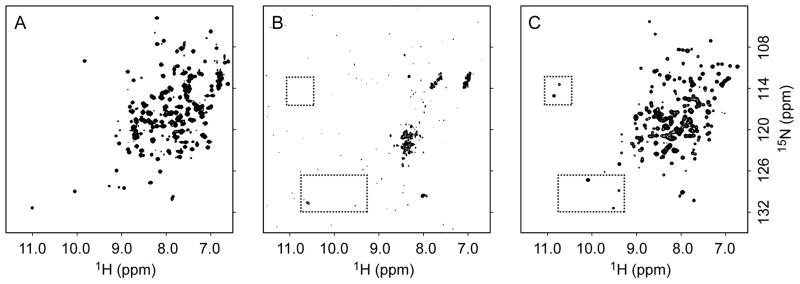

Figure 2. Encapsulation of myristoylated recoverin.

15N-HSQC spectra of recoverin (+myr) in (A) aqueous buffer in the Ca+2 free apo state; (B) Ca+2 free recoverin in CTAB/hexanol reverse micelles and (C) Ca+2 bound state of recoverin in CTAB reverse micelles. The spectra in B and C are the identical sample without and with Ca+2 collected with the same number of transients, the contour threshold is 5 times lower in spectrum B. The increased sensitivity and spectral dispersion of the Ca+2 bound state in reverse micelles is a clear demonstration of the folding of encapsulated recoverin(+myr) with the addition of Ca+2. The boxes include cross peaks that are followed during the titration of Ca+2 into reverse micelles shown in Figure 3.

The encapsulated apo-state of the protein can be quantitatively titrated with calcium and recovers an 15N-HSQC spectrum consistent with the native structure in free solution. Notably the very low intensities of crosspeaks in the spectrum of the apo-state are converted to a high intensity spectrum having the anticipated signal-to-noise ratio. This unusual result is most consistent with the apo-state being comprised of a dynamic mixture of structures (including lipid-sequestered and extruded forms) that interconvert on the chemical shift difference time scale. This effect is nicely illustrated by two glycine residues, G79 and G115, that participate in the turn region of the calcium loaded EF-hands and show have two characteristic upfield shifted amide N-H correlations in the calcium-saturated state. These cross peaks can be used to follow the binding of calcium to the protein (Figure 3). Binding of calcium stabilizes the form of the protein with an extruded lipid group (Ames et al., 1997). At a Ca2+: recoverin(+myr) stoichiometry of 1.5:1 weak signals begin to appear for the two glycine residues and increase upon subsequent addition of calcium while their chemical shifts remains constant. This demonstrates that the Ca2+-binding exchange rate is much slower than the chemical shift difference time scale and is therefore consistent with high affinity and functional Ca2+ binding under these conditions (see also Figure S3).

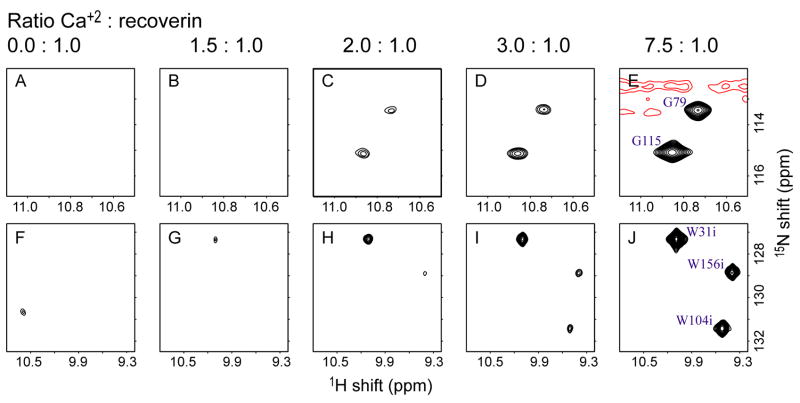

Figure 3. Titration of recoverin with Ca+2 in reverse micelles.

The 15N HSQC spectra of recoverin (+myr) in CTAB/hexanol reverse micelles in the top panels (A) through (E) are titration points following the amide N-H correlations of residues G79 and G115 in the native state with the additions of Ca+2. The molar ratios of Ca+2 : recoverin (+myr) are indicated above the panels. The bottom panels (F) through (J) show the disappearance of the indole N-H correlations of the tryptophan sidechain in the disordered apo-state and the appearance of their counterparts in the calcium-saturated state. The molar ratios are the same as in the top panels.

The behavior of the tryptophan indole N-H chemical shift correlations also inform on the extensive dynamic averaging in the encapsulated apo-state of the protein. In the absence of calcium, there is a single weak signal due to one or more of indole N-H correlations of W31, W156 and W104. We also ascribe this residual, broad signal to the heterogeneous mixture of structures of encapsulated apo-state of recoverin(+myr) that interconvert on the chemical shift difference time scale. As calcium is added, this broad cross peak disappears and three sharp indole N-H cross peaks arise. The indole N-H cross peak of W31 is the first to be sufficiently populated to appear above the noise floor, at a Ca2+:recoverin(+myr) stoichiometry of 1.5:1.0, while the indole N-H correlations of W156 and W104 appear at slightly higher calcium concentration. The intensity initially appears slowly, as the protein competes with the residual free EGTA for the added calcium, then builds up in a linear stoichiometric fashion with added Ca2+. This accounts for the greater than stoichiometric 2:1 Ca2+:recoverin(+myr) plateau of the titration curve at 7.5:1 Ca2+:recoverin(+myr) (Figure 3). An endpoint of the titration is reached where further addition of calcium does not result in additional signal intensity. At very high calcium concentrations, corresponding to greater than 10:1 Ca2+:recoverin(+myr) molar ratio, the excess calcium apparently disrupts the stability of the reverse micelle assembly and a catastrophic loss of sample integrity ensues.

Encapsulation of HIV-1 MA (+myr)

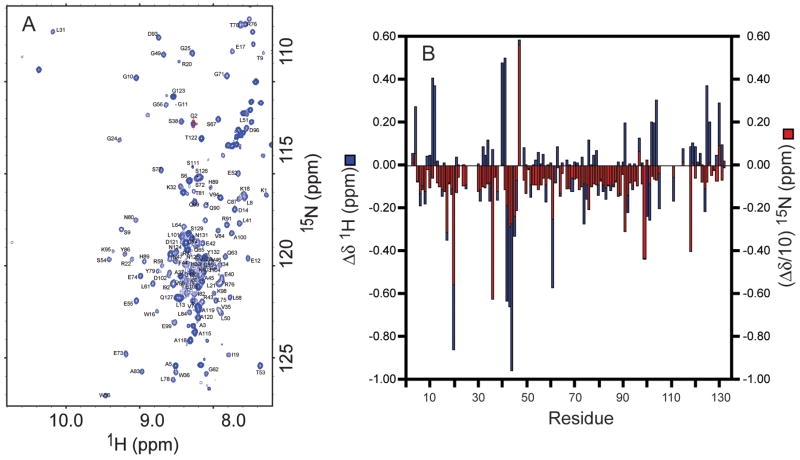

Encapsulation conditions have been developed for The N-terminal myristoylated matrix protein (MA) mediates membrane binding by an allosteric PI(4,5)P2-dependent myristoyl switch mechanism (Saad et al., 2006). Direct determination of the structure of the native PI(4,5]P2 bound state of the MA(+myr) domain has been precluded by insolubility problems and by the tendency of native PIP2 to form high molecular weight aggregates in solution. Recombinant MA proteins that contains [MA(+myr)] or lacks [MA(−myr)] the N-terminal myristoyl group were encapsulated into reverse micelles using the CTAB/hexanol surfactant system in pentane. The HIV-1 MA(+myr) protein has a basic pI of 9.1. Attempts to encapsulate HIV-1 MA(+myr) with either the acidic surfactant AOT or a triple surfactant mixture containing AOT : CTAB : LDAO proved fruitless. Though the MA protein encapsulated it was unfolded in both surfactant systems. In contrast, the CTAB/hexanol surfactant system produced an encapsulated folded myristoylated protein giving an 15N HSQC spectrum indicative of a folded protein. Encapsulation conditions were then optimized for maximum protein concentration. A maximum protein concentration in aqueous buffer of 4 mM could be maintained for a time sufficient for injection. Using a surfactant concentration of 200 mM CTAB and 8.5% (v/v) hexanol and a water loading (Wo) of 25 gave a final protein concentration of 180 μM. The 15N HSQC spectrum of encapsulated MA(+myr) is shown in Figure 4 and is compared to the aqueous spectrum in Figure S4. Except for a few resonances associated with surface residues that may have chemical shift perturbations due to electrostatic interactions with the surfactant shell, the backbone amide N-H chemical shifts of the encapsulated MA(+myr) protein are remarkably similar to those of the free solution MA(−myr) protein, which clearly indicates that the myristoyl group of the former leaves its hydrophobic pocket on the protein when placed into the reverse micelle assembly. The amide N-H chemical shift correlations were therefore initially assigned by reference the 15N/1H chemical shifts reported for the HIV-1 MA(−myr) in free aqueous solution (Massiah et al., 1994) and then corroborated using a 15N NOESY HSQC spectrum of the encapsulated protein and the main chain directed resonance assignment approach (MCD) (Wand and Nelson, 1991).

Figure 4. Encapsulation of myristoylated HIV-1 matrix protein.

(A) 15N HSQC spectrum of HIV-1 MA(+myr) in CTAB/hexanol reverse micelles. Assigned amide correlations are labeled. (B) The chemical shift differences between amide NH correlations in aqueous HIV-1 MA (-myr) spectrum minus the corresponding resonances the HIV-1 MA (+myr) protein encapsulated in CTAB/hexanol reverse micelles. the 15N chemical shift differences have been scaled by a factor of ten to reflect the difference in gyromagnetic ratios of 1H and 15N.

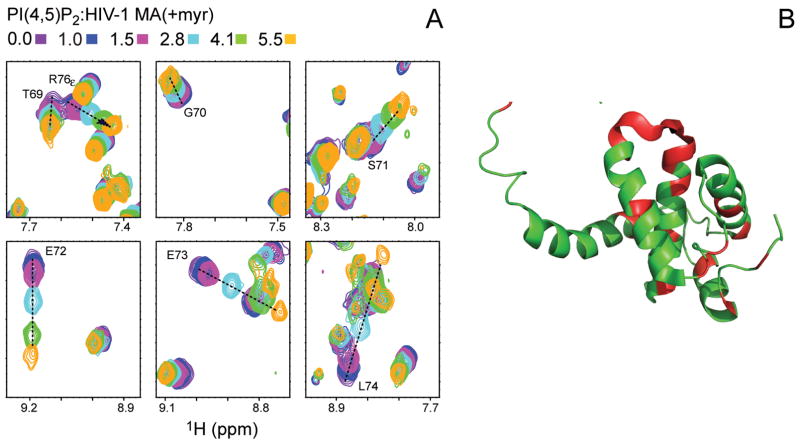

Titration of the MA(+myr) protein with its membrane targeting ligand 1-stearoyl-2-arachidonyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoinositol-4,5-bisphosphate in free solution results in degradation of the NMR performance of the protein due to severe line broadening (Saad et al., 2006). As mentioned above, this is due, in part, to the tendency of native PIP2 to form micelles in water. PI(4,5)P2 is insoluble in alkanes but is solubilized by CTAB/hexanol reverse micelles. This allows the MA(+myr) to be probed for the binding of the PI(4,5)P2 ligand. The binding of PI(4,5)P2 into the MA(+myr) was followed by 15N HSQC spectra (Figure 5). Several MA(+myr) amide N-H cross peaks can be seen to shift upon binding of PI(4,5)P2 but most remain relatively unperturbed (see Figure S5). The continuous shifting of selected resonances indicates specific binding that is in fast exchange on the NMR chemical shift time scale (Figure 5). The titration does not plateau (saturate) at the highest molar ratio of PI(4,5)P2: MA(+myr) of 5.5:1 that could be reached. Unfortunately, the reverse micelle assembly becomes unstable at higher concentrations of PI(4,5)P2. The amide sites that show significant shifts are indicated in green in the backbone ribbon diagram of the HIV-1 MA(-myr) NMR structure of Summers et al. (Massiah et al., 1994) (Figure 5). The binding is clearly localized at the basic surface patch containing the turn connecting helices III and IV, consistent with solution-state studies using soluble PIP2 analogs that contain truncated acyl chains.

Figure 5. Titration of encapsulated HIV-1 MA (+myr) with PI(4,5)P2.

(A) Expansions of the 15N HSQC spectra of HIV-1 MA(+myr) in CTAB/hexanol reverse micelles illustrating amide N-H correlations that shift upon titration with PI(4,5)P2. The molar ratios of PI(4,5)P2: MA(+myr) are color coded as indicated. (B) A ribbon representation of the solution NMR structure of HIV-1 MA(-myr) (Massiah et al., 1994) (PDB code 2HMX) is shown on the right with the backbone colored in red at sites that demonstrate significant shifts in the HSQC spectra on titration with PI(4,5)P2. Drawn with PyMol (DeLano, 2002).

DISCUSSION

Reverse micelle encapsulation appears to provide a simple and direct route to the detailed characterization of myristoylated proteins in their lipid extruded membrane anchored state. Under the surfactant and water compositions used here the reverse micelles contain on average several thousand water molecules. The quality of the spectra that are obtained for encapsulated calcium-saturated recoverin(+myr) and HIV-1 MA(−myr) are consistent with only one protein molecule in a reverse micelle. Higher occupancy would lead to severely broadened resonance lines (Wand et al., 1998).

The use of reverse micelle encapsulation to study lipidated proteins should prove highly complementary to those involving use of aqueous detergent micelles or isotropic bicelles. A particular advantage of the reverse micelle approach is the ability to employ low viscosity fluids such as liquid ethane that preserve favorable relaxation properties and thereby avoid the necessity for extensive deuteration. On the other hand, the continuing development of the more slow tumbling isotropic bicelle as a vehicle for studying membrane proteins in a true bilayer lipid environment will provide support for studies undertaken in the reverse micelle single layer shell (Kim et al., 2009).

The two example proteins studied here have quite distinct biological roles and contrasting ligand triggers for membrane anchoring. Recoverin employs the water-soluble calcium cation to initiate membrane anchoring that subsequently results in activation of the G-protein mediated signaling cascade. The calcium-activated state of the protein is fully folded while anchored to the reverse micelle surfactant shell. Interestingly, the presumably functionally inappropriate lipid extruded apo-state of the protein is promoted by encapsulation but results in an ensemble of states. The encapsulation of the protein apparently sufficiently modifies the equilibrium between the structures of recoverin that sequester or extrude the myristoyl group such that the latter is favored. This generates a dynamic mixture of sequestered and extruded forms in the apo-state and suggests that this mixture is dynamically exchanging in the absence of calcium, which would be consistent with the calcium-mediated signaling switch of the protein.. It is interesting to note that the encapsulated Ca2+-free recoverin exhibits very broad NMR resonances because the dynamic exchange of sequestered and extruded forms of the apo-protein causes structural changes that results in chemical shift differences that are not averaged thereby causing exchange broadening. The confined space of the reverse micelle apparently slows the dynamical interconversion of the ensemble of states such that no single (or average) spectral signature dominates. A similar effect is seen during the process of protein cold denaturation in reverse micelles (Babu et al., 2004; Pometun et al., 2006; Whitten et al., 2006).

The equilibrium between the sequestered and solvent exposed states of the myristoylated HIV-1 matrix protein is also significantly altered by encapsulation and pushed towards what is putatively the membrane-anchored structure of the protein. In contrast to recoverin, however, this state of the myristoylated MA protein is highly structured and is, by chemical shift analysis, closely similar to the unmyristoylated form of the protein i.e. the myristoyl group is fully extruded from the protein. This behavior is consistent with the idea that the MA protein needs to probe the identity of a given membrane by repetitive insertions of the anchor followed by binding of the plasma membrane specific PIP2 recognition element. In this model, the protein would naturally be stable and structured in both the soluble sequestered and membrane-anchored extruded states. Whether this distinction persists across the many different lipidated proteins remains an interesting and exciting question.

Analysis of the chemical shift perturbations brought about by the binding of PI(4,5)P2 to MA(+myr) indicate a similar but not identical interaction surface to that highlighted by the binding of a more water-soluble PIP2 analog (Saad et al., 2006). Detailed structural studies of the encapsulated MA(+myr):PI(4,5)P2 complex described here are on-going and will be reported elsewhere.

In conclusion, the results presented here suggest that the reverse micelle particle has been successfully adapted to the study of myristoylated proteins in the lipid-extruded state using high-resolution solution NMR methods. The generality of the encapsulation strategy for studying lipidated proteins remains to be ascertained especially with respect to the type of membrane anchor employed. Though some limitations are apparent, quite detailed structural investigations are clearly made feasible by this approach and include characterization of the structural basis for the interaction of ligands with proteins in the membrane-anchored state. Both water soluble and insoluble ligands can be employed. Though the confined space effects of reverse micelle complicate quantitative interpretation of observed binding phenomena, the ability to investigate the interactions of lipid-anchored proteins with small ligands in structural detail is a significant and very useful capability. Furthermore, the performance of proteins encapsulated in reverse micelles dissolved in alkane solvents of modest viscosity such as pentane can be directly reproduced in very low viscosity liquefied ethane. (Peterson et al., 2005b) and thereby take advantage of the reverse micelle approach as originally envisaged i.e. improve the relaxation properties of the protein such that the full power of solution NMR can be applied. The initial results presented here also provide the foundation for investigation of larger protein complexes associated with membrane-anchored protein cores. It should also be noted that the very simple reverse micelle surfactant system used here has quite different steric and electrostatic properties from a natural membrane bilayer. It is useful to begin consideration of reverse micelle surfactant systems to mimic the basic properties of membrane bilayers and “membrane rafts” (Pike, 2006).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Encapsulation of Recoverin(+myr) in reverse micelles

Myristoylated recoverin was prepared and purified from unmyristoylated protein by HPLC as previously described (Ames et al., 1994). The purified protein was >95% myristoylated as judged by electrospray mass spectrometry. A 0.5 mM solution of 15N recoverin(+myr) was buffer exchanged and concentrated using a 10 K amicon ultra-15 cell into 10 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 1mM DTT and 1 mM EGTA at pH 8.0. The maximum concentration tolerated was ~ 2mM before aggregation of the myristoylated protein was evident. The identification of optimal encapsulation conditions for recoverin(+myr) is summarized in the main text. The reverse micelle slurry of 200 mM CTAB, 8.5% v/v hexanol in d12-pentane was prepared in a glass vial. The concentrated protein solution (~68μl) was injected at a calculated water loading Wo of 25 (H2O:CTAB molar ratio) with a pipetman into the reverse micelle slurry and vortexed. With the addition of the aqueous protein solution, the reverse micelle assembles and the slurry clears in a matter of a few minutes with only gentle agitation. The solution is transferred to a Wilmad screw cap NMR tube for data acquisition. The reverse micelle solution is 180 μM recoverin(+myr), 200 mM CTAB, 8.5% (v/v) hexanol in d12-pentane. Encapsulated recoverin(+myr) was titrated with calcium by direct addition of aliquots of 100 mM CaCl2 in water. The sample was briefly vortexed to facilitate mixing

Encapsulation of HIV-1 MA(+myr)

15N-labeld HIV-1 MA(+myr) protein was prepared and purified from unmyristoylated protein as described previously (Massiah et al., 1994; Tang et al., 2004). The purity of the myristoylated protein was confirmed by electrospray mass spectrometry. The 15N HIV-1 MA(+myr) was buffer exchanged and concentrated using a 15K amicon ultra-4 cell into 1/10X the NMR buffer concentration 2 mM phosphate, 4 mM NaCl at pH 6.5. The maximum concentration tolerated was ~ 0.4 mM before aggregation of the myristoylated protein was evident. A protein aliquot of ~400 μl was then lyophilized. The lyophilized aliquot was the rehydrated in 1/10 the volume ~40μl resulting in a 20 mM phosphate, 40 mM NaCl buffered protein solution. The reverse micelle slurry of 200 mM CTAB, 10% v/v hexanol in d12-pentane was prepared in a glass vial. A sufficient volume of the concentrated protein solution (~40μl) to give a calculated water loading (Wo) of 15 (H2O:CTAB molar ratio)was injected into the reverse micelle slurry and vortexed. The initially cloudy solution clears in a few minutes. The reverse micelle solution in d12-pentane was 470 μM HIV-1 MA(+myr), 200 mM CTAB, 10% v/v hexanol and was transferred to a Wilmad screw cap tube for NMR data acquisition.

Titration of encapsulated HIV-1 MA(+myr) with PI(4,5)P2 18:0/20:4 lipid

The titration with PI(4,5)P2 is somewhat complicated by the lack of solubility of this lipid in either water or alkane solvent. The PI(4,5)P2 (Avanti Polar Lipids) was first dissolved in CHCl3:MeOH:H2O = 20:9:1 (v/v/v) at a concentration of 600 μM. Aliquots were then dried onto the surface of a glass vial with a stream of argon gas to form a thin film of the lipid. Solutions of encapsulated MA(+myr) in CTAB/hexanol reverse micelles were vortexed in the vial and the lipid solubilized into the reverse micelle assembly. The titration proceeded in increments of 0.5:1.0 to a final molar ratio of 5.5:1.0. Raising the concentration of lipid above ~1 mM in the 200 mM CTAB solution causes degradation of the reverse micelle solution resulting in extensive precipitation.

NMR Spectroscopy

15N HSQC spectra were collected on Bruker Avance III NMR spectrometers operating at 750 and 600 MHz (1H). Three-dimensional 15N NOESY-HSQC spectra were collected on the 15N recoverin(+myr) and 15N HIV-1 MA(+myr) reverse micelle samples using an NOE mixing time of 110 ms. The d12-pentane was used to lock the spectrometer. Both spectrometers were equipped with a cryogenically cooled probe that provided excellent signal-to-noise on the 70 μM to 180 μM encapsulated protein solutions owing to their optimal low conductivity (Flynn et al., 2000). FELIX was used to process the data and Sparky (Goddard and Kneller, 2004) was used for data analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant GM 085120 and a grant from the Mathers Foundation awarded to AJW and NIH grants EY012347 awarded to JBA and AI30917 awarded to MFS. AJW and RWP declare a competing financial interest as Members of Daedalus Innovations, LLC, a manufacturer of reverse micelle NMR apparatus.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ames JB, Ishima R, Tanaka T, Gordon JI, Stryer L, Ikura M. Molecular mechanics of calcium-myristoyl switches. Nature. 1997;389:198–202. doi: 10.1038/38310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames JB, Tanaka T, Ikura M, Stryer L. Nuclear magnetic resonance evidence for Ca(2+)-induced extrusion of the myristoyl group of recoverin. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:30909–30913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.30909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames JB, Tanaka T, Stryer L, Ikura M. Secondary structure of myristoylated recoverin determined by three-dimensional heteronuclear NMR: implications for the calcium-myristoyl switch. Biochemistry. 1994;33:10743–10753. doi: 10.1021/bi00201a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu CR, Flynn PF, Wand AJ. Preparation, characterization, and NMR spectroscopy of encapsulated proteins dissolved in low viscosity fluids. J Biomol NMR. 2003;25:313–323. doi: 10.1023/a:1023037823421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu CR, Hilser VJ, Wand AJ. Direct access to the cooperative substructure of proteins and the protein ensemble via cold denaturation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:352–357. doi: 10.1038/nsmb739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey PJ. Protein lipidation in cell signaling. Science (New York, NY) 1995;268:221–225. doi: 10.1126/science.7716512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano WL. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. San Carlos, CA: DeLano Scientific; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle DA, Cabral JM, Pfuetzner RA, Kuo AL, Gulbis JM, Cohen SL, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. The structure of the potassium channel: Molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn PF, Mattiello DL, Hill HDW, Wand AJ. Optimal use of cryogenic probe technology in NMR studies of proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:4823–4824. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard TD, Kneller DG. SPARKY. Vol. 3. University of California: San Fransisco; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Howell SC, Van Horn WD, Jeon YH, Sanders CR. Recent advances in the application of solution NMR spectroscopy to multi-span integral membrane proteins. Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. 2009;55:335–360. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre BG, Liu W, Peterson RW, Valentine KG, Wand AJ. NMR spectroscopy of proteins encapsulated in a positively charged surfactant. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 2005;175:158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindwasser OW, Resh MD. Myristoylation as a target for inhibiting HIV assembly: unsaturated fatty acids block viral budding. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13037–13042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212409999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massiah MA, Starich MR, Paschall C, Summers MF, Christensen AM, Sundquist WI. Three-dimensional structure of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein. J Mol Biol. 1994;244:198–223. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer-Stroh S, Eisenhaber F. Myristoylation of viral and bacterial proteins. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono A, Ablan SD, Lockett SJ, Nagashima K, Freed EO. Phosphatidylinositol (4,5) bisphosphate regulates HIV-1 Gag targeting to the plasma membrane. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14889–14894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405596101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RW, Lefebvre BG, Wand AJ. High-resolution NMR studies of encapsulated proteins in liquid ethane. J Am Chem Soc. 2005a;127:10176–10177. doi: 10.1021/ja0526517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RW, Lefebvre BG, Wand AJ. High-resolution NMR studies of encapsulated proteins in liquid ethane. J Am Chem Soc. 2005b;127:10176–10177. doi: 10.1021/ja0526517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RW, Pometun MS, Shi Z, Wand AJ. Novel surfactant mixtures for NMR spectroscopy of encapsulated proteins dissolved in low-viscosity fluids. Prot Sci. 2005c;14:2919–2921. doi: 10.1110/ps.051535405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike LJ. Rafts defined: a report on the Keystone Symposium on Lipid Rafts and Cell Function. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1597–1598. doi: 10.1194/jlr.E600002-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pometun MS, Peterson RW, Babu CR, Wand AJ. Cold denaturation of encapsulated ubiquitin. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:10652–10653. doi: 10.1021/ja0628654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resh MD. Fatty acylation of proteins: new insights into membrane targeting of myristoylated and palmitoylated proteins. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1999;1451:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(99)00075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad JS, Miller J, Tai J, Kim A, Ghanam RH, Summers MF. Structural basis for targeting HIV-1 Gag proteins to the plasma membrane for virus assembly. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11364–11369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602818103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Z, Peterson RW, Wand AJ. New reverse micelle surfactant systems optimized for high-resolution NMR spectroscopy of encapsulated proteins. Langmuir. 2005;21:10632–10637. doi: 10.1021/la051409a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Ames JB, Harvey TS, Stryer L, Ikura M. Sequestration of the membrane-targeting myristoyl group of recoverin in the calcium-free state. Nature. 1995;376:444–447. doi: 10.1038/376444a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C, Loeliger E, Luncsford P, Kinde I, Beckett D, Summers MF. Entropic switch regulates myristate exposure in the HIV-1 matrix protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:517–522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305665101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wand AJ, Ehrhardt MR, Flynn PF. High-resolution NMR of encapsulated proteins dissolved in low-viscosity fluids. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15299–15302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wand AJ, Nelson SJ. Refinement of the main chain directed assignment strategy for the analysis of H-1 NMR spectra of proteins. Biophys J. 1991;59:1101–1112. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82325-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitten ST, Kurtz AJ, Pometun MS, Wand AJ, Hilser VJ. Revealing the nature of the native state ensemble through cold denaturation. Biochemistry. 2006;45:10163–10174. doi: 10.1021/bi060855+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.