Abstract

Five Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates with reduced susceptibility to tigecycline (MIC, 2 μg/ml) were analyzed. A gene homologous to ramR of Salmonella enterica was identified in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sequencing of ramR in the nonsusceptible Klebsiella strains revealed deletions, insertions, and point mutations. Transformation of mutants with wild-type ramR genes, but not with mutant ramR genes, restored susceptibility to tigecycline and repressed overexpression of ramA and acrB. Thus, this study reveals a molecular mechanism for tigecycline resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae.

Klebsiella pneumoniae is an important pathogen of nosocomial infections, including urinary tract infections, pneumonia, wound infections, and sepsis (22). Klebsiella pneumoniae rapidly acquires resistance to most commonly used beta-lactam antibiotics by different mechanisms, including expression of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs), plasmid-mediated AmpC beta-lactamases, and recently also carbapenemases (29). Isolates are also frequently nonsusceptible to fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides, leaving only few if any treatment options, and even infections with untreatable, panresistant strains have been reported (6). Infections with such multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens represent an important field of application for treatment with the recently introduced antibiotic tigecycline (8, 14, 20, 30), the first member of the novel class of glycylcyclines (19). It has an extraordinarily broad spectrum of antibacterial activity, covering most Gram-positive, Gram-negative, and anaerobic pathogens, including vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and ESBL- and carbapenemase-producing strains (8). Unfortunately, the emergence of resistance to tigecycline in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates has already been reported (25, 28).

Overexpression of RamA, which is a positive regulator of the AcrAB efflux system, has been observed in tigecycline-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains (2, 25, 28) and also in tigecycline-resistant Enterobacter cloacae isolates (11). Furthermore, AcrAB and related efflux pumps which confer resistance to multiple antibiotics, including tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, chloramphenicol, and others (21, 23), have been implicated in resistance to tigecycline in several other species (4, 5, 9-12, 16, 26, 27, 32). The overexpression of ramA seemed to be causative for overexpression of AcrAB in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterobacter cloacae, but the molecular basis of ramA upregulation could not be defined in these species. We were recently able to show that upregulation of ramA and consecutively AcrAB in a tigecycline-resistant Salmonella enterica isolate was due to an inactivating mutation in ramR, a repressor of ramA (1, 13, 17, 24) in Salmonella (9). How ramA is regulated in bacteria other than Salmonella is currently unknown.

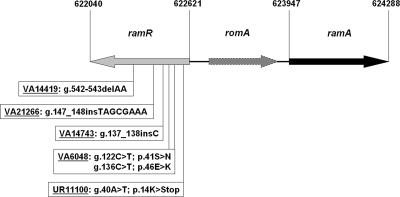

We collected five independent Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from our diagnostic service, and they exhibited suspiciously small disk diffusion zone diameters (<19 mm), and further analyzed these strains. For tigecycline, MICs were determined by broth microdilution with a commercially available tigecycline panel (Merlin Diagnostika GmbH, Bornheim-Hersel, Germany) using freshly prepared (<12 h old) Mueller-Hinton II broth (BBL, BD Bioscience, Sparks, MD). For ciprofloxacin and chloramphenicol, MICs were determined by Etest (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden). MICs were interpreted according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) clinical breakpoints (for tigecycline, ≤1.0 μg/ml is susceptible, 2.0 μg/ml is intermediate, and >2.0 μg/ml is resistant; for ciprofloxacin, ≤0.5 μg/ml is susceptible, 1.0 μg/ml is intermediate, and >1.0 μg/ml is resistant; for chloramphenicol, ≤8.0 μg/ml is susceptible and >8.0 μg/ml is resistant). All five isolates exhibited MICs of 2 μg/ml, which was interpreted as intermediate. Testing of 12 randomly collected Klebsiella pneumoniae patient isolates with disk diffusion zone diameters of >19 mm uniformly revealed MICs of 0.25 μg/ml. Resistance to tigecycline in Klebsiella pneumoniae has previously been linked to overexpression of ramA (28). Because we recently found in a tigecycline-resistant Salmonella isolate that ramA overexpression was due to a mutation in ramR, a known negative regulator of ramA (9), we asked whether a similar mechanism is instrumental in Klebsiella. A BLAST search identified a predicted Klebsiella pneumoniae protein (accession number YP_001334235) with 63% identity to Salmonella RamR (NP_459572.1). Strikingly, the gene for this protein is located directly upstream of the Klebsiella pneumoniae ramA gene (YP_001334236.1) in a head-to-head arrangement (Fig. 1), a genomic organization reminiscent of the respective situation in Salmonella. The intergenic region between ramR and ramA additionally harbors a predicted gene, romA, with homology to beta-lactamase genes. It was previously shown not to be involved in the ramA-mediated MDR phenotype (7), but if expressed, it may be coregulated by RamR due to its genomic localization, albeit with unknown significance. Interestingly, a putative palindromic binding element for RamR mutated in some fluoroquinolone-resistant Salmonella isolates (1, 13) is highly conserved in Klebsiella pneumoniae and located in the intergenic region between ramR and ramA (nucleotides 622742 to 622762). These similarities strongly suggest that the identified gene represents the Klebsiella pneumoniae homologue of Salmonella ramR.

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of the genomic region comprising ramR and ramA of Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae MGH 78578 (CP000647). The mutations identified in the ramR genes of the nonsusceptible Klebsiella strains are indicated. g., gene (nucleotide position); p., protein (amino acid position); del, deletion; ins, insertion.

We amplified the ramR gene and the surrounding genomic region from the tigecycline-resistant strains and the 12 randomly collected strains with MICs of 0.25 μg/ml and performed sequence analysis (forward [5′-CTGCAG-TGCCCGGTGAACCCTGGCGT] and reverse [5′-CTGCAG-ATTTGCTGATTCAGCAGCGAC] primers). In all five non-tigecycline-susceptible strains, mutations in ramR relative to the reference sequence Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae MGH 78578 (CP000647), as depicted in Fig. 1, were detected. Four strains (UR11100, VA14419, VA14743, and VA21266) harbored deletions, insertions, or point mutations leading to a premature stop codon, which result in predicted truncated RamR proteins highly likely to be nonfunctional. VA6048 harbored two mutations leading to amino acid exchanges in the coding region of ramR. None of these mutations were found in the 12 tigecycline-susceptible strains. Instead, two different silent polymorphisms (594G→T and 150G→A [gene]) were detected and two strains harbored polymorphisms in the ramR gene, which resulted in amino acid exchanges (VA21490 harbored two exchanges, 437A→G [gene]/146I→T [protein] and 454A→T [gene]/152Y→N [protein], and VA21488 harbored one exchange identical to the first in VA24190, 437A→G [gene]/146I→T [protein]). We cloned the ramR genes of all the mutants, of a Klebsiella pneumoniae strain with a wild-type (WT) MIC to tigecycline, a wild-type sequence of ramR (from VA12262), and ramR sequences of the two strains (VA21488 and VA21490) harboring the coding polymorphisms together with the surrounding genomic regions into the PstI site of the pACYC177 vector using PCR products with the forward and reverse primers (see above). All constructs were verified by sequencing. Two of the mutant strains, VA6048 and VA14743, were amenable for transformation. Transformation of VA6048 and of VA14743 with wild-type ramRVA12262 [Klebsiella pneumoniae VA6048 (ramRVA12262-WT) and Klebsiella pneumoniae VA14743 (ramRVA12262-WT), respectively] lowered the MIC for tigecycline in both strains from 2 μg/ml to 0.25 μg/ml, as shown in Table 1. Both ramRVA21488 and ramRVA21490 lowered the MICs for tigecycline of VA6048 and VA14743 to the same extent as ramRVA12262-WT (data not shown), indicating that the amino acid exchanges represent nonfunctional polymorphisms. In contrast, introduction of any of the mutated ramR genes (ramRVA6048, ramRUR11100, ramRVA14419, ramRVA14743, and ramRVA21266) or the empty pACYC177 vector did not affect the MIC for tigecycline in VA6048 or VA14743. These findings suggest that the identified ramR homologue is involved in resistance to tigecycline and that the identified mutations in the nonsusceptible strains are functionally relevant. The AcrAB system is involved in resistance to antibiotics from multiple classes. Thus, we also tested MICs for ciprofloxacin and chloramphenicol in our strains, as both are known to be substrates of AcrAB. Consistent with the findings for tigecycline, MICs for ciprofloxacin and for chloramphenicol of VA6048 and VA14743 were lowered when wild-type ramR was introduced but remained unchanged when mutated ramR or empty pACYC177 vector was transformed (Table 1). These results strongly imply that ramR in Klebsiella pneumoniae is involved in the regulation of AcrAB in a manner similar to that in Salmonella.

TABLE 1.

MICs and relative expressions of ramA and acrB of strains used in this study

| Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate | MIC (μg/ml) and statusa |

Relative expressiond |

Origine | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tigecyclineb | Ciprofloxacinc | Chloramphenicolc | ramA | acrB | ||

| VA6048 | 2 I | 0.125 S | 24.0 R | 28.9 ± 8.1 | 11.6 ± 1.3 | Gallbladder |

| UR11100 | 2 I | 4.0 R | 32.0 R | 25.1 ± 5.9 | 10.9 ± 0.4 | Urine |

| VA14419 | 2 I | >32.0 R | >256.0 R | 40.5 ± 11.4 | 14.9 ± 1.6 | Wound |

| VA14743 | 2 I | 4.0 R | 24.0 R | 48.9 ± 10.5 | 7.8 ± 1.0 | Trachea |

| VA21266 | 2 I | 0.25 S | 32.0 R | 38.9 ± 10.3 | 15.8 ± 2.8 | Pharynx |

| VA12262-WT | 0.25 S | 0.064 S | 8.0 I | 1 | 1 | Trachea |

| VA6048 (ramRVA12262-WT) | 0.25 S | 0.012 S | 1.0 S | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | |

| VA6048 (ramRVA6048) | 2 I | 0.125 S | 16.0 R | 32.4 ± 7.2 | 10.9 ± 1.8 | |

| VA6048(pACYC177) | 2 I | 0.125 S | 24.0 R | 46.5 ± 16.4 | 18.9 ± 6.6 | |

| VA6048 (ramRUR11100) | 2 I | 0.125 S | 24.0 R | 25.0 ± 11.6 | 5.8 ± 0.9 | |

| VA6048 (ramRVA14419) | 2 I | 0.125 S | 16.0 R | 21.2 ± 4.2 | 8.4 ± 3.0 | |

| VA6048 (ramRVA21266) | 2 I | 0.125 S | 16.0 R | 29.9 ± 10.7 | 14.5 ± 3.3 | |

| VA14743 (ramRVA12262-WT) | 0.25 S | 0.25 S | 1.0 S | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | |

| VA14743 (ramRVA14743) | 2 I | 4.0 R | 32.0 R | 50.4 ± 8.9 | 17.8 ± 9.3 | |

| VA14743(pACYC177) | 2 I | 4.0 R | 32.0 R | 45.6 ± 5.4 | 5.1 ± 0.5 | |

| VA14743 (ramRUR11100) | 2 I | 4.0 R | 16.0 R | 43.8 ± 7.0 | 11.0 ± 2.3 | |

| VA14743 (ramRVA14419) | 2 I | 2.0 R | 16.0 R | 57.6 ± 15.3 | 22.0 ± 10.2 | |

| VA14743 (ramRVA21266) | 2 I | 4.0 R | 32.0 R | 66.7 ± 30.1 | 10.1 ± 4.7 | |

S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant. Status determinations are according to EUCAST clinical breakpoints (www.eucast.org/).

Tested by broth microdilution.

Tested by Etest.

Measured by quantitative RT-PCR, shown as x-fold expression of VA12262 (expression = 1). Results are means of 3 (ramA) or 2 (acrB) runs ± standard deviations.

All isolates were obtained as a result of this study.

Next, we directly analyzed the influence of Klebsiella pneumoniae ramR on the transcriptional expression level of ramA by Northern blot hybridization (hybridization probes for ramA were generated with primers 5′-ATGACGATTTCCGCTCAGGTGA and 5′-CAGTGGGCGCGACTGTGGTTC, and those for 16S rRNA [rrsE] were generated with primers 5′-TTGACGTTACCCGCAGAAGAA and 5′-TCTACAAGACTCTAGCCTGCCA; these were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP [Hartmann-Analytic, Braunschweig, Germany] by using the Megaprime DNA labeling system from GE Healthcare). We also used SYBR green quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) using the qPCR Core SYBR green I kit from Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium (primers used for qRT-PCR are the same as for the generation of the Northern blot hybridization probes except ramA-rev-qPCR [5′-CAGCCGTTGCAGATGCCATTTC]). RNA was isolated with the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). First, expression levels of ramA in the 12 randomly selected Klebsiella pneumoniae strains with MICs of 0.25 μg/ml were compared to those in the five nonsusceptible strains by Northern blot hybridization. Three micrograms of the isolated total RNA was separated by electrophoresis in a gel containing 1% agarose and 1.2% formaldehyde and was subsequently transferred to a nylon membrane (Macherey-Nagel, Dueren, Germany) by neutral capillary elution in 20× SSC (3 M NaCl, 0.3 M trisodium-citrate dehydrate). Hybridization was carried out at 65°C in 10 ml hybmix (7% SDS, 10% PEG 20000, 0.22 M NaCl, 1.5 mM EDTA, 15 mM sodium phosphate, 5 μg/ml sonicated salmon sperm DNA, 500,000 cpm specific probe) overnight, washed three times at 65°C with 2× SSC-0.1% SDS, and then exposed to Kodak MS autoradiograph films. While expression of ramA was uniformly low in strains with wild-type MICs to tigecycline, ramA expression was very prominent in the nonsusceptible strains (VA6048, UR11100, VA14419, VA14743, and VA21266), suggesting massive upregulation (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

RamR represses expression of ramA in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Expression levels of ramA were analyzed by Northern blot hybridization. Total RNAs of the strains indicated were isolated from mid-log-phase cultures. Three micrograms of total RNA was loaded into each lane, and the filters were hybridized with [32P]dCTP-labeled probes of ramA and subsequently 16S rRNA (rrsE) as a loading control. Values on the left of the panels are band sizes in kbp. (A) Comparison of ramA expression levels in non-tigecyline-susceptible strains and susceptible strains. VA14743 is included in the Northern blot on the right side as a positive control. (B) ramA expression in nonsusceptible strains transformed with mutated or wild-type ramR.

For qRT-PCR, RNA was pretreated with DNase I (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and then reverse transcribed with the SuperScript kit (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). qRT-PCRs were run on a Rotor Gene Q cycler (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) with 45 cycles of 20 s at 95°C, 20 s at 60°C, and 30 s at 72°C. Data were analyzed by using the 2−ΔΔCT method (15). Quantification by qRT-PCR demonstrated 25-fold to nearly 50-fold upregulation in the nonsusceptible strains compared to VA12262-WT, which served as the reference strain (Table 1). Furthermore, qRT-PCR of acrB (forward primer, 5′-TTAATACCCAGACCGGATGC; reverse primer, 5′-TGGCCGCGGGCCAGTTAGGCGGTA), a target gene of RamA, revealed concomitant 8-fold-to-15-fold upregulation in the mutants compared to the level for the wild-type strain VA12262 (Table 1). Transformation of wild-type ramR (from VA12262-WT) into VA6048 [Klebsiella pneumoniae VA6048 (ramRVA12262-WT)] and into VA14743 [Klebsiella pneumoniae VA14743 (ramRVA12262-WT)] resulted in strongly repressed ramA expression, while no change in ramA expression was noted in strains transformed with any of the mutated ramR genes from the nonsusceptible strains or the empty pACYC177 vector as analyzed by Northen blot hybridization (Fig. 2B) and by qRT-PCR (Table 1). Again, changes in the expression levels of acrB accompanied those observed for ramA (Table 1). All strains harboring mutated ramR overexpressed acrB in comparison to the wild-type strain VA12262 or the mutants VA6048 and VA14743 complemented with wild-type ramR [Klebsiella pneumoniae VA6048 (ramRVA12262-WT) and Klebsiella pneumoniae VA14743 (ramRVA12262-WT), respectively]. These experiments establish ramR in Klebsiella pneumoniae as a repressor of ramA.

In summary, we identified a gene in Klebsiella pneumoniae with homology to ramR, a repressor of ramA in Salmonella enterica, which is mutated in strains resistant to tigecycline (9) and to ciprofloxacin (1, 13, 17, 24). Our results imply that ramA in Klebsiella pneumoniae is regulated in a manner similar to its regulation in Salmonella and provide a molecular mechanism for tigecycline resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. All of our non-tigecycline-susceptible Klebsiella pneumoniae strains harbored mutations in the ramR gene, suggesting that this is a major molecular mechanism for tigecycline resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Though the susceptibilities of all of our strains were clearly reduced compared to those of wild-type strains, none of our strains exhibited full resistance to tigecyline by definition (MIC > 2 μg/ml). However, fully resistant Klebsiella strains have been described previously (6, 28), suggesting that several mechanisms might contribute to tigecycline resistance. Acquisition of mutations in ramR may represent one step in the development of full resistance; however, in certain body compartments like the bloodstream, where only low concentrations of tigecycline can be achieved, an intermediate phenotype may be sufficient to result in therapeutic failure of tigecycline (3, 18). Other resistance mechanisms, like Tn1721-associated tet(A) (9, 31), may be additive and upon acquisition successively result in full resistance. It is particularly worrisome that AcrAB-mediated multidrug resistance can be induced by prior treatment with a multitude of antibiotics. Furthermore, it cannot be unambiguously inferred from the resistance phenotype exhibited by an individual isolate in vitro during routine diagnostic resistance testing. Thus, susceptibility testing to tigecycline of all relevant isolates would be beneficial when tigecyline treatment is an option.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 March 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abouzeed, Y. M., S. Baucheron, and A. Cloeckaert. 2008. ramR mutations involved in efflux-mediated multidrug resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:2428-2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bratu, S., D. Landman, A. George, J. Salvani, and J. Quale. 2009. Correlation of the expression of acrB and the regulatory genes marA, soxS and ramA with antimicrobial resistance in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae endemic to New York City. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:278-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curcio, D. 2008. Tigecycline for treating bloodstream infections: a critical analysis of the available evidence. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 61:358-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Damier-Piolle, L., S. Magnet, S. Bremont, T. Lambert, and P. Courvalin. 2008. AdeIJK, a resistance-nodulation-cell division pump effluxing multiple antibiotics in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:557-562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dean, C. R., M. A. Visalli, S. J. Projan, P. E. Sum, and P. A. Bradford. 2003. Efflux-mediated resistance to tigecycline (GAR-936) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:972-978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elemam, A., J. Rahimian, and W. Mandell. 2009. Infection with panresistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: a report of 2 cases and a brief review of the literature. Clin. Infect. Dis. 49:271-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.George, A. M., R. M. Hall, and H. W. Stokes. 1995. Multidrug resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae: a novel gene, ramA, confers a multidrug resistance phenotype in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 141(Part 8):1909-1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hawkey, P., and R. Finch. 2007. Tigecycline: in-vitro performance as a predictor of clinical efficacy. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13:354-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hentschke, M., M. Christner, I. Sobottka, M. Aepfelbacher, and H. Rohde. 2010. Combined ramR mutation and presence of a Tn1721-associated tet(A) variant in a clinical isolate of Salmonella enterica serovar Hadar resistant to tigecycline. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:1319-1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hornsey, M., M. J. Ellington, M. Doumith, S. Hudson, D. M. Livermore, and N. Woodford. 2010. Tigecycline resistance in Serratia marcescens associated with up-regulation of the SdeXY-HasF efflux system also active against ciprofloxacin and cefpirome. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:479-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keeney, D., A. Ruzin, and P. A. Bradford. 2007. RamA, a transcriptional regulator, and AcrAB, an RND-type efflux pump, are associated with decreased susceptibility to tigecycline in Enterobacter cloacae. Microb. Drug Resist. 13:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keeney, D., A. Ruzin, F. McAleese, E. Murphy, and P. A. Bradford. 2008. MarA-mediated overexpression of the AcrAB efflux pump results in decreased susceptibility to tigecycline in Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:46-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kehrenberg, C., A. Cloeckaert, G. Klein, and S. Schwarz. 2009. Decreased fluoroquinolone susceptibility in mutants of Salmonella serovars other than Typhimurium: detection of novel mutations involved in modulated expression of ramA and soxS. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:1175-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelesidis, T., D. E. Karageorgopoulos, I. Kelesidis, and M. E. Falagas. 2008. Tigecycline for the treatment of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a systematic review of the evidence from microbiological and clinical studies. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:895-904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livak, K. J., and T. D. Schmittgen. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-delta delta C(T)) method. Methods 25:402-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McAleese, F., P. Petersen, A. Ruzin, P. M. Dunman, E. Murphy, S. J. Projan, and P. A. Bradford. 2005. A novel MATE family efflux pump contributes to the reduced susceptibility of laboratory-derived Staphylococcus aureus mutants to tigecycline. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1865-1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Regan, E., T. Quinn, J. M. Pages, M. McCusker, L. Piddock, and S. Fanning. 2009. Multiple regulatory pathways associated with high-level ciprofloxacin and multidrug resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar enteritidis: involvement of RamA and other global regulators. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:1080-1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parsonage, M., S. Shah, P. Moss, H. Thaker, R. Meigh, A. Balaji, J. Elston, and G. Barlow. 2010. Breakthrough bacteraemia with a susceptible Enterococcus faecalis during tigecycline monotherapy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:370-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petersen, P. J., N. V. Jacobus, W. J. Weiss, P. E. Sum, and R. T. Testa. 1999. In vitro and in vivo antibacterial activities of a novel glycylcycline, the 9-t-butylglycylamido derivative of minocycline (GAR-936). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:738-744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peterson, L. R. 2008. A review of tigecycline—the first glycylcycline. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 32(Suppl. 4):S215-S222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piddock, L. J. 2006. Multidrug-resistance efflux pumps—not just for resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4:629-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Podschun, R., and U. Ullmann. 1998. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:589-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poole, K. 2005. Efflux-mediated antimicrobial resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56:20-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ricci, V., and L. J. Piddock. 2009. Ciprofloxacin selects for multidrug resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium mediated by at least two different pathways. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 63:909-916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruzin, A., F. W. Immermann, and P. A. Bradford. 2008. Real-time PCR and statistical analyses of acrAB and ramA expression in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3430-3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruzin, A., D. Keeney, and P. A. Bradford. 2005. AcrAB efflux pump plays a role in decreased susceptibility to tigecycline in Morganella morganii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:791-793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruzin, A., D. Keeney, and P. A. Bradford. 2007. AdeABC multidrug efflux pump is associated with decreased susceptibility to tigecycline in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 59:1001-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruzin, A., M. A. Visalli, D. Keeney, and P. A. Bradford. 2005. Influence of transcriptional activator RamA on expression of multidrug efflux pump AcrAB and tigecycline susceptibility in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1017-1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Souli, M., I. Galani, and H. Giamarellou. 2008. Emergence of extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli in Europe. Euro Surveill. 13:19045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stein, G. E., and W. A. Craig. 2006. Tigecycline: a critical analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 43:518-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tuckman, M., P. J. Petersen, and S. J. Projan. 2000. Mutations in the interdomain loop region of the tetA(A) tetracycline resistance gene increase efflux of minocycline and glycylcyclines. Microb. Drug Resist. 6:277-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Visalli, M. A., E. Murphy, S. J. Projan, and P. A. Bradford. 2003. AcrAB multidrug efflux pump is associated with reduced levels of susceptibility to tigecycline (GAR-936) in Proteus mirabilis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:665-669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]