Abstract

Candidate HIV-1 vaccine regimens utilizing intramuscularly (i.m.) administered recombinant adenovirus (rAd)-based vectors can induce potent mucosal cellular immunity. However, the degree to which mucosal rAd vaccine routing might alter the quality and anatomic distribution of vaccine-elicited CD8+ T lymphocytes remains unclear. We show that the route of vaccination critically impacts not only the magnitude but also the phenotype and trafficking of antigen-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in mice. I.m. rAd immunization induced robust local transgene expression and elicited high-frequency, polyfunctional CD8+ T lymphocytes that trafficked broadly to both systemic and mucosal compartments. In contrast, intranasal (i.n.) rAd immunization led to similarly robust local transgene expression but generated low-frequency, monofunctional CD8+ T lymphocytes with restricted anatomic trafficking patterns. Respiratory rAd immunization elicited systemic and mucosal CD8+ T lymphocytes with phenotypes and trafficking properties distinct from those elicited by i.m. or i.n. rAd immunization. Our findings indicate that the anatomic microenvironment of antigen expression critically impacts the phenotype and trafficking of antigen-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes.

Acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection is accompanied by a massive, irreversible destruction of memory CD4+ T lymphocytes, particularly within the intestinal mucosa (11, 26, 30, 42), as a result of the high proportion of effector/memory target cells within the intestinal lamina propria. Chronic HIV-1 infection is characterized by inflammation within the intestinal mucosa, breakdown of epithelial-barrier integrity, and translocation of gut microflora from the intestinal lumen (10, 24). These processes may drive systemic inflammation and contribute to HIV-1 disease progression. Therefore, vaccination strategies that enhance mucosal cellular immunity and attenuate the mucosal immunopathology of HIV-1 infection would be desirable.

Recombinant adenovirus (rAd) vectors are potent inducers of cellular immunity (3, 12, 25), and we have recently demonstrated that intramuscular (i.m.) rAd immunization transiently activates peripheral antigen-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes and allows them to migrate to mucosal surfaces and establish potent, durable mucosal cellular immunity (22). Moreover, we have shown that an i.m. delivered heterologous rAd prime-boost regimen prevented the destruction of CD4+ T lymphocytes within the intestinal mucosa and attenuated disease progression following simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) challenge (29). Notably, this vaccine regimen did not contain the SIV Env protein, indicating that cellular mucosal immunity likely played a critical role in abrogating mucosal CD4+ T-lymphocyte destruction.

While our laboratory and others have observed potent mucosal CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses after i.m. immunization with rAd vectors (2, 21, 28, 41) and other vaccine modalities (40-41), other studies have suggested that mucosal routing of vaccine vectors may optimize mucosal cellular immunity (4-7, 16, 33, 36, 46). We therefore assessed the phenotype and anatomic trafficking patterns of antigen-specific CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses following i.m. and mucosal rAd immunization in mice. We found that the immunization route dramatically impacted the phenotype of vaccine-elicited systemic and mucosal CD8+ T lymphocytes. In particular, while both i.m. and intranasal (i.n.) rAd immunization resulted in efficient local transgene expression, only i.m. immunization induced potent, polyfunctional cellular immune memory in both systemic and mucosal anatomic compartments, while i.n. immunization elicited lower-frequency cellular immune responses that were restricted to mucosal surfaces and characterized by monofunctional gamma interferon (IFN-γ) secretion. Our data highlight the critical impact of the route of antigen delivery and the anatomic microenvironment of transgene expression on the quality and distribution of vaccine-elicited CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals, vectors, and immunizations.

The construction of rAd26 and rAd5HVR48 vectors expressing SIVmac239 Gag has been described previously (1, 34). rAd5HVR48 expressing firefly luciferase (Luc) and rAd5 expressing chicken ovalbumin (Ova) were constructed using an E1/E3-deleted adenovirus cosmid and adapter plasmid system as described previously (1, 3). Six- to 8-week-old C57BL/6, BALB/c, B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ, and OT-1 mice were obtained from Charles River and Jackson Laboratories and maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions. Mice were immunized with 107, 108, or 109 viral particles (VP) of various replication-incompetent rAd vectors. For i.m. immunization, the vectors were administered in 100 μl sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) divided equally between the two quadriceps muscles. For intranasal immunization, vectors were administered to mice under isoflurane anesthesia in 10 μl PBS divided equally between the two nostrils using round gel-loading pipette tips. For oral and rectal immunization, mice were fasted overnight prior to vaccination. For oral immunization, vectors were administered by gavage in 100 μl PBS using a disposable feeding needle. For rectal immunization, mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of ketamine, and vector was instilled 1 cm into the rectum in 50 μl PBS using a standard pipette tip. Animals were placed in a recumbent position for 30 min following immunization. For respiratory aerosol immunization, mice were anesthetized by i.p. ketamine administration. The trachea was transilluminated and cannulated with a respiratory aerosolization syringe (PennCentury, Inc.), and the vectors were delivered in 50 μl PBS as previously described (9). For prime-boost regimens, mice were immunized as described above with injections spaced 6 weeks apart. All animals used in this study were maintained in accordance with institutional guidelines, and studies were reviewed and approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Mucosal lymphocyte isolation.

Mucosal lymphocyte populations were isolated as previously described (22). Briefly, the small and large bowel, vaginal tract, and respiratory tract (total lung, bronchial, and tracheal tissues) were dissected free of associated connective tissue and cut into small pieces using straight scissors. Bowel specimens were incubated with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) supplemented with 0.2 mM EDTA and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C for 30 min with vigorous shaking to release the intraepithelial lymphocyte (IEL) population. Cells from the supernatant were resuspended in 40% Percoll (Sigma Chemical) and layered over 67% Percoll; samples were centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 20 min, and lymphocytes were isolated from the interface. After IEL removal, bowel specimens were washed three times with RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% FBS to remove all traces of EDTA. Mucosal tissues were then digested by two serial 30-min incubations at 37°C in RPMI 1640 containing 5% FBS supplemented with type II collagenase (Sigma Chemical) at 300 U/ml with vigorous shaking. Pooled supernatants from serial incubations were purified on a Percoll gradient as described above. Nasal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT) lymphocytes were isolated as previously described (18).

In vivo imaging of luciferase protein expression.

BALB/c mice were immunized with rAd5HVR48-luciferase as described above. At various time points following immunization, mice were anesthetized by i.p. injection of ketamine/xylazine (Sigma) and injected i.p. with 100 μl PBS containing 30 mg/ml d-luciferin (Caliper Life Sciences). In vivo luminescence (13) was observed and quantitated using an IVIS Lumina II charge-coupled device (CCD) imaging system and Living Image software (Caliper Life Sciences).

Tetramer binding assays.

H-2Db tetramers labeled with phycoerytherin and folded around the immunodominant SIV Gag epitope AL11 (AAVKNWMTQTL) (Db/AL11) were used to stain peripheral blood and tissue lymphocytes as described previously (22). Samples were analyzed using an LSRII flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) and FloJo software (Tree Star). CD8+ T lymphocytes from naïve mice were utilized as negative controls and exhibited <0.1% tetramer staining at all anatomic sites. The monoclonal antibodies used in multiparameter flow cytometry were purchased from BD Biosciences (CD8α-peridinin chlorophyll protein [PerCP]-Cy5.5 [53-6.7], CD3-allophycocyanin [APC] [145-2C111], and CD44-fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC] [IM7]) and eBioscience (CD127-phycoerythrin [PE]-Cy7 [A7R34], CD62L-APC-AlexaFluor750 [Mel-14], CD45.1-PE-Cy7 [A20], and CD45.2 APC-AlexaFluor750 [104]). Live/Dead Fixable Violet was used for vital dye exclusion in flow cytometric assays according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen).

Intracellular cytokine staining assays.

Lymphocytes isolated from various anatomic sites were stimulated for 6 h at 37°C in 500 μl medium containing 4 μl/ml GolgiStop and GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences), 4 μg/ml antibodies to CD28 and CD49d (37.51 and R1-2; BD biosciences), 5 μg/ml FITC-conjugated antibodies to CD107a and CD107b (1D4B and ABL-93; BD Biosciences), and 4 μg/ml pooled overlapping SIV Gag peptides. Cells incubated under the same conditions but without SIV Gag peptides were used as negative controls. The cells were stained with fluorescently conjugated anti-CD3α, -CD4, and -CD8 monoclonal antibodies as described above and then fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences). The permeabilized cells were incubated with PE-conjugated anti-interleukin-2 (IL-2) (JES6-5H4; BD Biosciences), APC-conjugated anti-IFN-γ (XMG1.2; BD Biosciences), and PE-Cy7-congugated anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (MP6-X22; BD Biosciences); washed; and resuspended in PBS containing 1.6% formaldehyde. Samples were analyzed using an LSRII flow cytometer and FloJo software.

Adoptive transfer studies.

Lymphocytes were isolated from the spleens and cervical, axillary, and inguinal lymph nodes (LN) of naïve OT-1 mice by mechanical dissociation. CD8+ T lymphocytes were purified from pooled lymphocyte populations by negative selection using immunomagnetic beads (CD8+ T-cell isolation kit; Miltenyi Biotec) and an AutoMACS cell separator (Miltenyi) according to the manufacturer's instructions. OT-1 CD8+ T lymphocytes were >95% pure by OT-1 tetramer binding assays. Purified OT-1 CD8+ T lymphocytes were washed twice with PBS, resuspended at 107 cells/ml in HBSS containing 1 μm carboxyfluorescein succinyl ester (CFSE; Invitrogen), and incubated for 20 min at 37°C with gentle rocking. The cells were washed once with serum-containing medium and twice with PBS. The cells were resuspended in cold, sterile PBS and transferred to recipient mice by tail vein injection.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism version 4.01 (GraphPad Software, Inc., 2005). Immune responses among groups of mice are presented as means with standard errors. Comparisons of mean immune responses were performed using two-sided t tests. In all cases, P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Intramuscular and intranasal rAd immunization generates comparable dynamics of transgene expression but divergent anatomic patterns of T-lymphocyte trafficking and cellular immunity.

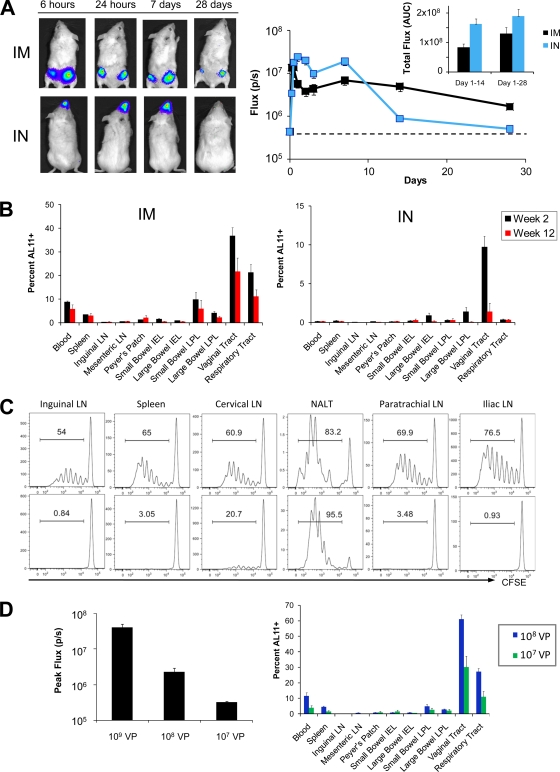

We initially evaluated the magnitude, kinetics, and anatomic distribution of rAd-transduced transgene expression following i.m., oral (p.o.), intrarectal (i.r.), or i.n. immunization in mice. For these studies, we utilized a hexon-chimeric rAd vector, rAd5HVR48, which has been described previously (34). VP rAd5HVR48 (109) encoding firefly luciferase (rAd5HVR48-luc) was administered by each route to BALB/c mice (n = 12/group), and the dynamics of in vivo luciferase protein expression were monitored following intravenous (i.v.) injection of luciferin substrate using a cooled CCD in vivo imaging system (13). P.o. and i.r. vector administrations were inefficient in inducing luciferase expression (data not shown). In contrast, i.m. and i.n. immunizations induced comparable high levels of luciferase expression that peaked 24 h following vector administration and persisted for at least 2 weeks following immunization (Fig. 1 A). The total area under the curve (AUC) of luciferase expression over time was greater following i.n. than following i.m. immunization through day 14 (P < 0.001 by a two-tailed t test) and day 28 (P = 0.06 by a two-tailed t test) (Fig. 1A, inset), although differences in expression kinetics were observed. There was also a marked difference in the anatomic distribution of luciferase expression, which was detected exclusively within the nasopharynx after i.n. immunization and within the quadriceps muscles and inguinal lymph nodes following i.m. immunization (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Comparative magnitude and anatomic distribution of transgene expression and vaccine-elicited cellular immunity following i.m. and i.n. rAd immunization. (A) BALB/c mice (n = 12/group) were immunized by the i.m. or i.n. route with 109 VP rAd5HVR48-luc. In vivo luciferase gene expression was quantitated at various time points following immunization using high-sensitivity in vivo imaging. (B) C57BL/6 mice (n = 4/group) were immunized by the i.m. or i.n. route with 109 VP rAd5HVR48-Gag. At week 2 following immunization, the magnitude and distribution of vaccine-elicited Gag-specific CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses were determined using Db/AL11 tetramer binding assays. (C) OT-1 CD8+ T lymphocytes (3 × 106) were labeled with CFSE and adoptively transferred to naïve, CD45-congenic recipients (n = 4/group). Mice were immunized by the i.m. or i.n. route with 109 VP rAd5-Ova, and OT-1 CD8+ T-lymphocyte proliferation, as indicated by CFSE dilution, was assessed at multiple anatomic sites at day 3 following immunization. (D) (Left) BALB/c mice (n = 8/group) were immunized i.m. with 109, 108, or 107 VP rAd5HVR48-luc, and transgene transduction was assessed by in vivo imaging. (Right) C57BL/6 mice (n = 4/group) were immunized i.m. with 108 or 107 VP rAd5-HVR48-Gag. Gag-specific CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses were determined at day 14 following immunization using a Db/AL11 tetramer binding assay. The error bars represent standard errors (SE).

To determine the relationship between rAd-encoded transgene expression and rAd-elicited cellular immunity, C57BL/6 mice (n = 4/group) were immunized by the i.m., p.o., i.r., and i.n. routes with 109 VP rAd5HVR48 expressing SIVmac239 Gag (rAd5HVR48-Gag). The magnitude and anatomic distribution of Gag-specific CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses were determined at weeks 2 and 12 following immunization using Db/AL11 tetramer binding assays (22). P.o. and i.r. immunizations with rAd5HVR48-Gag proved poorly immunogenic in all anatomic compartments, presumably as a result of poor vector uptake and antigen expression (data not shown).

Unexpectedly, despite comparably efficient transgene transduction, i.m. and i.n. immunization gave rise to strikingly divergent patterns of CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses. Following i.m. immunization, robust CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses were observed in multiple systemic and mucosal anatomic compartments, including the spleen, small and large intestine lamina propria, respiratory tract, and vaginal tract, and these high-frequency responses persisted in each anatomic compartment through week 12 following immunization (Fig. 1B). Similar magnitudes and kinetics of systemic and mucosal CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses were observed following i.m. immunization with other rAd vectors, including rAd5 and rAd26 (data not shown). In contrast, i.n. immunization with rAd5HVR48-Gag gave rise to CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses that were lower in magnitude (P < 0.05 for comparison with i.m. immunization in blood, spleen, small intestine IEL and lamina propria lymphocytes [LPL], vaginal tract, and respiratory tract using 2-tailed t tests). Moreover, responses following i.n. immunization were almost exclusively restricted to mucosal surfaces, such as the large intestine and vaginal tract (Fig. 1B). I.n. immunization notably did not elicit any detectable systemic CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses in the blood or spleen. Similar results were observed at week 12 following i.n. immunization (Fig. 1B). These data demonstrate that the anatomic localization of rAd-encoded transgene expression profoundly impacts the pattern of the resultant transgene-specific mucosal CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses.

We next evaluated the impact of the anatomic localization of rAd-mediated transgene transduction on CD8+ T-lymphocyte priming and trafficking. CD8+ T lymphocytes were purified from the spleen and peripheral lymph nodes of naïve OT-1 mice, which possess a transgenic T-cell receptor (TCR) specific for the immunodominant SIINFEKL peptide from chicken ovalbumin (Ova) (19). Naïve OT-1 CD8+ T lymphocytes were labeled with CFSE and adoptively transferred to naïve, CD45-congenic recipients (C57.SJL). Recipient animals (n = 4/group) were then immunized by the i.m. or i.n. route with 109 VP of rAd5-Ova. At day 3 following immunization, early CD8+ T-lymphocyte priming and dissemination were evaluated by assessing CFSE dilution in OT-1 lymphocytes at multiple anatomic sites. Following i.m. immunization, proliferating OT-1 T lymphocytes could be observed in all mucosal and nonmucosal anatomic compartments that we studied (Fig. 1C). In contrast, proliferating OT-1 T lymphocytes were restricted to NALT and, to some extent, cervical lymph nodes following i.n. immunization (Fig. 1C). No proliferating OT-1 cells were observed in paratracheal lymph nodes draining the lower respiratory tract, consistent with our observation that transgene expression is restricted to the nasopharynx following i.n. rAd immunization (Fig. 1A). Likewise, proliferating OT-1 cells were absent from iliac LN draining the vaginal tract following i.n. immunization, indicating that the high-frequency CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses in the vaginal tract generated by i.n. immunization (Fig. 1B) likely represented T-cell trafficking rather than local priming. These data suggest that early differences in the anatomic patterns of T-cell priming and trafficking presumably underlie the different anatomic distributions of vaccine-elicited CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses following i.m. versus i.n. immunization.

Our data suggested a widely divergent relationship between transgene expression and induction of cellular immunity following i.n. and i.m. immunization. We therefore asked whether significantly lower doses of i.m.-administered rAd vectors that result in poor transgene expression would still induce high-frequency systemic and mucosal CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses. C57BL/6 mice (n = 4/group) were immunized i.m. with 108 or 107 VP rAd5HVR48-Gag, and CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses were assessed by Db/AL11 tetramer binding assays at day 14 following immunization. Concurrently, transgene expression was evaluated by in vivo imaging in mice immunized with 109, 108, or 107 VP rAd5HVR48-luc. Following i.m. immunization with 108 VP rAd5HVR48-luc, we observed a 5-fold-lower peak magnitude of transgene transduction compared to 109 VP of the same vector (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1D). Transgene expression was at the lower limit of detection following immunization with 107 VP rAd5HVR48-luc (Fig. 1D). Nevertheless, at doses of 108 and 107 VP, rAd5HVR48-Gag efficiently generated high-frequency CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses that bridged multiple anatomic compartments (Fig. 1D). These data indicate that the site of priming, and not solely the transgene expression level, determines the trafficking patterns and anatomic distributions of CD8+ T lymphocytes.

The route of rAd vaccine delivery impacts the phenotype of vaccine-elicited CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses.

While multiple studies have evaluated the magnitudes of CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses elicited by various systemic and mucosal routes of immunization (2, 4-7, 16, 21, 28, 33, 36, 41, 46), the impact of the immunization route on the phenotype of these responses has not previously been assessed in detail. We therefore evaluated the functionality of CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses in both peripheral and mucosal anatomic compartments following i.m. and i.n. rAd immunization.

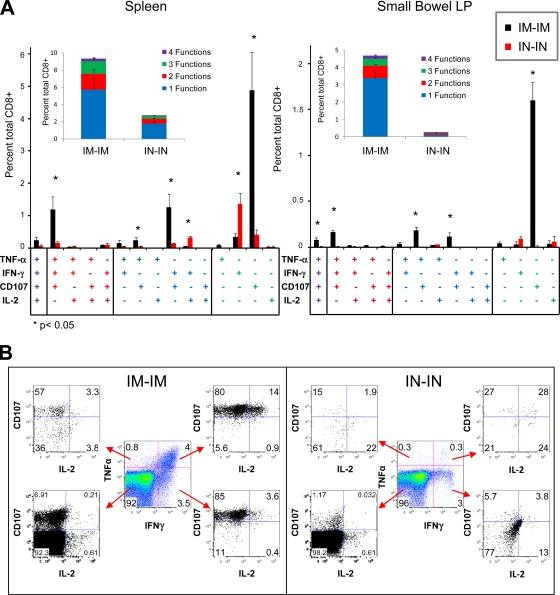

C57BL/6 mice (n = 8/group) were primed by either the i.n. or i.m. route with 109 VP of a rAd26 vector expressing SIV Gag (rAd26-Gag). At week 6 following the priming immunization, animals were boosted by the same route with 109 VP of a heterologous rAd5HVR48-Gag vector. CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses were evaluated in the spleen and small intestine lamina propria at week 2 following the boost immunization by intracellular cytokine staining assays specific for IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and the cytotoxic degranulation marker CD107 (8, 35). Both i.n.-i.n. and i.m.-i.m. regimens elicited CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses in each anatomic compartment. However, i.m.-i.m. rAd immunization induced a significantly higher proportion of polyfunctional Gag-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes that elaborated more than one effector function in both spleen and small bowel (Fig. 2A, inset; P < 0.05 for each comparison). Highly polyfunctional responses remained evident through week 20 following i.m. rAd immunization (data not shown). In contrast, i.n.-i.n. rAd immunization generated significantly higher monofunctional IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T lymphocytes (P < 0.05 in the spleen) and few CD107+ cells (P < 0.001 in both spleen and small bowel lamina propria). Sham immunization produced background response frequencies of <0.1% in each compartment (data not shown). Monofunctional IFN-γ-secreting cells are associated with an exhausted T-cell phenotype (8, 17, 35), and thus, these data suggest that i.m.-i.m. rAd immunization induces significantly more functional CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses than does i.n.-i.n.-i.n. rAd immunization.

FIG. 2.

Quality of CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses elicited by i.m.-i.m. and i.n.-i.n. heterologous rAd prime-boost regimens. C57BL/6 mice (n = 8/group) were primed by either the i.m. or i.n. route with 109 VP rAd26-Gag. At week 6 following priming, mice were boosted by the same route with 109 VP rAd5HVR48-Gag. At week 2 following the boost immunization, the magnitude and functionality of Gag-specific CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses were assessed using ICS assays for IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, and CD107. (A) Collated data for each individual combination of functions and in summary by number of functions (inset). (B) A representative comparison of responses in the spleen. The error bars represent SE.

I.m.- and i.n.-administered rAd vectors differ in their capacities to prime for a boost immunization.

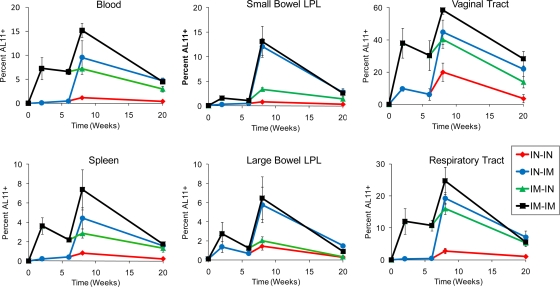

Previous studies have suggested that mucosal rAd vector immunization can efficiently prime for a boosted mucosal recall response (23, 44). We therefore evaluated the extent to which i.n. rAd priming would alter the magnitude of the resultant mucosal CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses following a heterologous boost immunization. C57BL/6 mice (n = 4/group) were primed by either the i.n. or i.m. route with 109 VP of rAd26-Gag. At week 6 following the priming immunization, animals were boosted by either the i.n. or i.m. route with 109 VP of rAd5HVR48-Gag. The magnitudes and anatomic distributions of CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses were evaluated at various time points through week 12 following the boost immunization using Db/AL11 tetramer binding assays.

I.m. rAd immunization efficiently primed for an i.m. boost response in multiple systemic and mucosal compartments (Fig. 3, black lines; P < 0.05 in blood, small bowel LPL, and respiratory tract, comparing responses at week 2 postprime versus week 2 postboost using 2-tailed t tests). In contrast, responses in the blood and spleen at week 2 postboost following i.n.-i.m. immunization were comparable to those at week 2 following the i.m. prime immunization (Fig. 3, blue lines at week 8 in comparison with black lines at week 2), indicating no detectable effect of i.n. priming in these anatomic compartments. However, for the same comparison, i.n.-i.m. immunization generated significantly higher CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses in the small bowel lamina propria (P = 0.01 using 2-tailed t tests) and a trend toward higher-frequency responses in the large bowel lamina propria and respiratory tract. These data confirm our previous results (Fig. 1B and 2) and show that i.n. rAd priming primarily induced mucosal recall responses with minimal systemic recall responses. Moreover, i.n. priming offered no detectable advantage over i.m. priming for eliciting mucosal CD8+ T-lymphocyte recall responses.

FIG. 3.

Comparative magnitudes and distributions of CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses elicited by i.m.-i.m. and i.n.-i.n. heterologous rAd prime-boost regimens. C57BL/6 mice (n = 4/group) were primed by either the i.m. or i.n. route with 109 VP rAd26-Gag. At week 6 following priming, the mice were boosted by either the i.m. or i.n. route with 109 VP rAd5HVR48-Gag. CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses were evaluated over a 20-week time course in multiple anatomic compartments by Db/AL11 tetramer binding assays. The error bars represent SE.

Respiratory rAd immunization generates polyfunctional systemic and mucosal CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses despite transient rAd-encoded transgene expression.

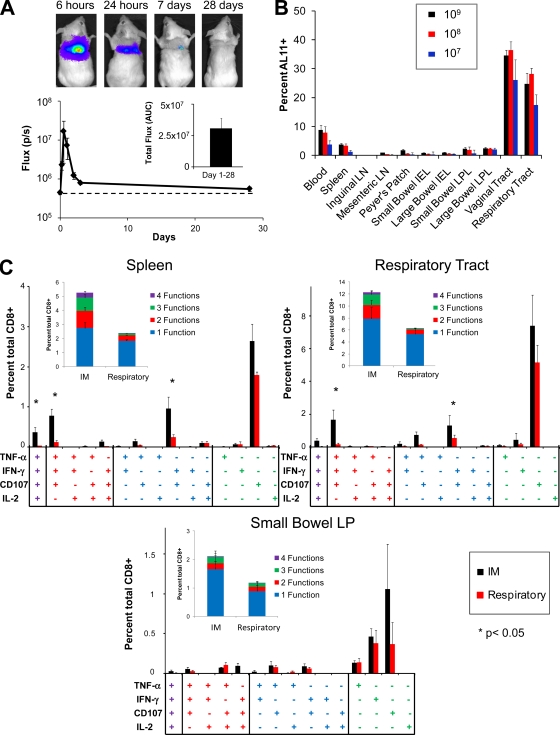

Previous studies have suggested that respiratory aerosolization efficiently delivers vaccines to the distal respiratory tract—a large mucosal surface rich in antigen-presenting cells (37-38). Therefore, we asked whether rAd vectors delivered by respiratory aerosolization could effectively transduce target cells in the lung and elicit polyfunctional systemic and mucosal CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses. To evaluate transduction efficiency, BALB/c mice (n = 12) were immunized by respiratory aerosolizaiton with 109 VP rAd5HVR48-luc, and the magnitude, kinetics, and distribution of luciferase expression were monitored by in vivo imaging (Fig. 4 A). rAd5HVR48-luc rapidly and efficiently transduced the lung following respiratory immunization, as shown by comparable peak magnitudes of luciferase expression obtained after respiratory (Fig. 4A) and i.m. (Fig. 1A) immunization. However, in contrast to i.m. immunization, there was a rapid loss of rAd transgene expression following respiratory immunization, with luciferase activity nearly returning to baseline by day 7 following immunization (Fig. 4A, inset, in comparison to Fig. 1A, inset; P < 0.001 for the comparison of AUCs for days 1 to 14 using 2-tailed t tests). Despite the more transient nature of transgene expression in this setting, respiratory immunization with 109 VP rAd5HVR48-Gag still induced robust CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses in multiple systemic and mucosal compartments at week 2 following immunization (Fig. 4B) that were comparable in distribution to responses induced by i.m. rAd immunization (Fig. 1B). Respiratory rAd immunization with 108 VP or 107 VP rAd5HVR48-Gag likewise elicited high-frequency CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses with a broad anatomic distribution at week 2 following immunization (Fig. 4B), comparable to the responses observed following i.m. immunization with these doses of vector (Fig. 1B). In each instance, we also evaluated the effector or memory phenotype of antigen-specific CD8+ T-lymphocyte populations using antibodies to CD127 and CD62L (20). No significant differences in the proportions of effector (CD62L− CD127low), effector memory (CD62L− CD127high), or central memory (CD62L+ CD127high) Gag-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes were observed at either week 2 or week 12 following immunization when respiratory was compared to i.m. immunization at each vector dose (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Trangene expression and vaccine-elicited cellular immunity following administration of rAd vectors by respiratory aerosolization. (A) BALB/c mice (n = 12) were immunized with 109 VP rAd5HVR48-luc by respiratory aerosolization, and the magnitude and distribution of luciferase gene expression were determined by in vivo imaging. (B) C57BL/6 mice (n = 4/group) were immunized with 109, 108, or 107 VP rAd5HVR48-Gag by respiratory immunization. The magnitude and distribution of vaccine-elicited CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses were determined at week 2 following immunization by Db/AL11 tetramer binding assays. (C) C57BL/6 mice (n = 8/group) were immunized by the i.m. or respiratory route with 109 VP rAd5HVR48-Gag. At week 2, Gag-specific CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses in the spleen, respiratory tract, and small bowel lamina propria were assessed by ICS assays for IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, and CD107. The error bars represent SE.

We next compared the functional phenotypes of Gag-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes elicited by i.m. and respiratory rAd immunization. C57BL/6 mice (n = 8/group) were immunized by the i.m. or respiratory route with 109 VP rAd5HVR48-Gag. Gag-specific CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses were evaluated at week 2 following immunization by polyfunctional intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) assays. In concordance with our tetramer binding assays (Fig. 1B and 4B), i.m. and respiratory rAd immunization elicited robust Gag-specific CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses at both systemic and mucosal sites, including the spleen, small bowel lamina propria, and respiratory tract (Fig. 4C). There were trends toward higher frequency and more polyfunctional responses in each anatomic compartment following i.m. compared to respiratory rAd immunization, but these differences were statistically significant only in the spleen (P = 0.003 for magnitude, and P = 0.006 for the ratio of polyfunctional to monofunctional Gag-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes using 2-sided t tests). Both i.m. and respiratory rAd immunizations induced a high proportion of monofunctional and polyfunctional CD107+ Gag-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes (Fig. 4C), although i.m. immunization induced a significantly higher frequency of IFN-γ, TNF-α, and CD107 triple-positive cells in both the spleen and respiratory tract (P < 0.01 by two-tailed t test) (Fig. 4C). These data indicate that both i.m. and respiratory rAd immunization can induce robust CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses in multiple systemic and mucosal anatomic compartments, despite striking differences in the kinetics and anatomic distribution of transgene expression.

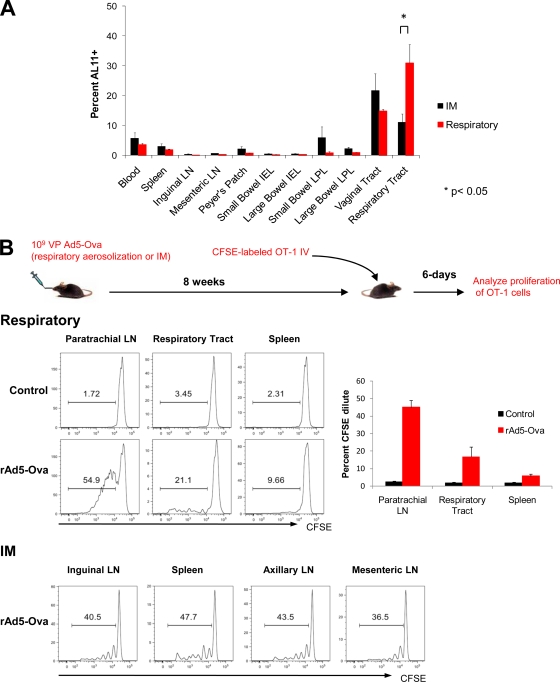

Differential trafficking of vaccine-elicited T lymphocytes following i.m. and respiratory rAd immunization.

The transition from the effector phase to the memory phase of a cellular immune response is typically characterized by contraction of the responding T-lymphocyte population (45). However, at week 12 following respiratory immunization with 109 VP rAd5HVR48-Gag, we observed unexpectedly high-frequency memory CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses in the respiratory tract (Fig. 5 A). Moreover, these week 12 responses in the respiratory tract, but not other anatomic compartments, were significantly greater in magnitude than those observed at the same time point following i.m. immunization (Fig. 5A; P = 0.026 using a 2-tailed t test). This observation suggested that i.m. and respiratory immunization may differentially impact the ongoing recruitment, expansion, and trafficking of CD8+ T lymphocytes.

FIG. 5.

Local CD8+ T-lymphocyte proliferation and anatomic skewing of memory responses following respiratory rAd immunization. (A) C57BL/6 mice (n = 4/group) were immunized with 109 VP rAd5HVR48-Gag by respiratory aerosolization. The magnitudes and anatomic distributions of vaccine-elicited CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses were determined at week 12 following immunization by Db/AL11 tetramer binding assays. (B) TCR-transgenic CD8+ T lymphocytes were purified from OT-1 mice and labeled with CFSE. Cells (106) were adoptively transferred to either naïve C57.SJL mice or C57.SJL mice that had been immunized 8 weeks earlier with 109 VP rAd5-Ova by respiratory aerosolization or i.m. injection (n = 4/group). Proliferation was assessed by CFSE dilution at day 6 following adoptive transfer. The error bars represent SE.

We evaluated ongoing T-lymphocyte recruitment and trafficking at a late time point following rAd immunization using adoptive transfer studies. C57.SJL mice were immunized by respiratory aerosolization or i.m. injection with 109 VP rAd5-Ova. At week 8 following immunization, CD8+ T lymphocytes were purified from the spleen and peripheral lymph nodes of naïve OT-1 mice. Naïve OT-1 CD8+ T lymphocytes were labeled with CFSE, and 2 × 106 cells were adoptively transferred to immunized or control animals (n = 4/group). At day 6 following adoptive transfer, proliferation, as assessed by CFSE dilution, was evaluated at multiple anatomic sites. Only minimal proliferation of OT-1 lymphocytes was detected in any anatomic compartment in the control mice (Fig. 5B). In contrast, CFSE-labeled OT-1 lymphocytes proliferated and expanded efficiently in the paratracheal lymph nodes of mice that had been immunized 2 months earlier with rAd5-Ova (Fig. 5B). Proliferating OT-1 lymphocytes were also readily apparent in the respiratory tracts and, to a much lesser extent, in the spleens of rAd5-Ova-immunized animals (Fig. 5B). OT-1 lymphocytes also proliferated efficiently following adoptive transfer at 2 months after i.m. immunization (Fig. 5B). However, in contrast to respiratory immunization, proliferating OT-1 lymphocytes following i.m. immunization did not accumulate preferentially in the lymph nodes draining the original inoculation site but rather broadly trafficked to both systemic and mucosal lymphoid tissues. These data are consistent with our observations following i.m. and i.n. immunization (Fig. 1C) that the immunization route greatly impacts the anatomic trafficking patterns of vaccine-elicited CD8+ T lymphocytes.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show that the route of rAd vector delivery critically impacts the phenotype and anatomic trafficking patterns of vaccine-elicited CD8+ T lymphocytes. In particular, i.m. rAd immunization consistently generated high-frequency, polyfunctional CD8+ T lymphocytes that trafficked readily to systemic and mucosal compartments. In contrast, i.n. immunization generated monofunctional CD8+ T lymphocytes with restricted anatomic trafficking patterns. Thus, differences in the anatomic distribution and kinetics of antigen expression have a major impact on the magnitude, anatomic compartmentalization, and phenotype of the resultant antigen-specific CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses.

While previous studies have evaluated the impact of the route of immunization on the magnitude of systemic and mucosal cellular immune responses (2, 4-7, 16, 21, 28, 33, 36, 41, 46), the phenotype of CD8+ T lymphocytes elicited by different vaccination routes has not previously been assessed in detail. Using polyfunctional ICS, we demonstrated that i.m. and i.n. rAd immunization induced antigen-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes with markedly different phenotypes. Whereas i.m. rAd immunization generated significantly more polyfunctional antigen-specific CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses characterized by expression of the cytotoxic degranulation marker CD107, i.n. rAd immunization generated responses that were characterized primarily by monofunctional IFN-γ production (Fig. 2). Although the functional significance of these different phenotypes remains to be fully determined, several studies have correlated polyfunctional responses with enhanced protective efficacy, while monofunctional IFN-γ production has been associated with T-lymphocyte exhaustion and ineffective cellular immune protection (15, 31).

Our studies highlight the impact of microenvironment-specific factors on the interrelationship between antigen expression and the induction of vaccine-elicited mucosal cellular immunity. I.m. and i.n. rAd immunization afforded robust and comparable extents of local transgene transduction (Fig. 1A). However, i.m. and i.n. rAd immunization generated antigen-specific CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses with strikingly different magnitudes and anatomic distributions. Whereas i.m. rAd immunization generated broadly distributed, high-frequency CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses, i.n. rAd immunization generated lower-magnitude responses that were almost exclusively restricted to mucosal sites (Fig. 1B). Immunization with rAd vectors by respiratory aerosolization likewise generated high-frequency, broadly distributed CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses (Fig. 4B) despite markedly more transient kinetics of transgene transduction than with i.m. rAd immunization (Fig. 4A). It is not yet known which microenvironment-specific factors contribute to these divergent patterns of transgene expression and vaccine-elicited cellular immunity.

Our data are consistent with a number of studies that have reported rAd-induced mucosal CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses in mice and rhesus monkeys following intramuscular immunization (2, 21, 28, 41). However, our findings contrast with those of other studies that have suggested that mucosal rAd vector routing is advantageous for inducing CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses at mucosal surfaces (14, 16, 27, 32, 36, 43, 46). We suspect that these differences may be related to the specifics of the various experimental systems utilized, such as differences in immunization techniques or vector doses. For example, our i.n. immunizations were confined to the nasopharynx (Fig. 1A), whereas previous studies have shown that higher volumes of intranasal instillation mediate passage of the instillate to the lower respiratory tract (39). Some studies have also surgically or chemically manipulated mucosal surfaces (44, 46), which could lead to persistent inflammation at the site of antigen delivery and alter the dynamics of antigen uptake and presentation by local antigen-presenting cells. We do not exclude the possibility, however, that future advances in mucosal delivery technologies may improve the efficiency of mucosal immunization strategies.

Using adoptive transfer studies, we assessed the initial priming and trafficking patterns of antigen-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes following immunization. I.m. rAd immunization generated a population of proliferating antigen-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes that could readily traffic to multiple systemic and mucosal anatomic compartments (Fig. 1C). In contrast, CD8+ T lymphocytes proliferated only in the NALT and cervical LN following i.n. rAd immunization and were preferentially retained in these anatomic sites (Fig. 1C). Additionally, CD8+ T lymphocytes recruited to proliferate at late time points following respiratory, but not i.m., immunization preferentially accumulated at the site of antigen exposure (Fig. 5B). We speculate that the different priming microenvironments may have the capacity to imprint distinct trafficking properties on responding CD8+ T lymphocytes.

In summary, our data demonstrate that differences in anatomic patterns of antigen expression critically impact the phenotype and trafficking properties of vaccine-elicited CD8+ T lymphocytes in mice. The mechanisms underlying these complex interrelationships remain to be determined but may be related to differences in the priming and imprinting capacities of local antigen-presenting cells. Further studies should define these underlying mechanisms, which may improve our ability to design vaccines that target polyfunctional cellular immune responses to particular anatomic compartments. These findings indicate the importance of the local microenvironment of immune priming in driving distinct patterns of antigen-specific cellular immune responses.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Cruz, D. Lynch, E. Rhee, H. DaCosta, M. Lifton, V. Toxavidis, J. Tigges, N. Letvin and J. Goudsmit for generous advice and assistance.

We acknowledge grant support from the NIH (K08 AI083079) to D.R.K. and from the NIH (U19 AI066305, U19 AI078526, and R01 AI066924) and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (38614) to D.H.B.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 31 March 2010.

The authors have paid a fee to allow immediate free access to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbink, P., A. A. Lemckert, B. A. Ewald, D. M. Lynch, M. Denholtz, S. Smits, L. Holterman, I. Damen, R. Vogels, A. R. Thorner, K. L. O'Brien, A. Carville, K. G. Mansfield, J. Goudsmit, M. J. Havenga, and D. H. Barouch. 2007. Comparative seroprevalence and immunogenicity of six rare serotype recombinant adenovirus vaccine vectors from subgroups B and D. J. Virol. 81:4654-4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baig, J., D. B. Levy, P. F. McKay, J. E. Schmitz, S. Santra, R. A. Subbramanian, M. J. Kuroda, M. A. Lifton, D. A. Gorgone, L. S. Wyatt, B. Moss, Y. Huang, B. K. Chakrabarti, L. Xu, W. P. Kong, Z. Y. Yang, J. R. Mascola, G. J. Nabel, A. Carville, A. A. Lackner, R. S. Veazey, and N. L. Letvin. 2002. Elicitation of simian immunodeficiency virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in mucosal compartments of rhesus monkeys by systemic vaccination. J. Virol. 76:11484-11490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barouch, D. H., M. G. Pau, J. H. Custers, W. Koudstaal, S. Kostense, M. J. Havenga, D. M. Truitt, S. M. Sumida, M. G. Kishko, J. C. Arthur, B. Korioth-Schmitz, M. H. Newberg, D. A. Gorgone, M. A. Lifton, D. L. Panicali, G. J. Nabel, N. L. Letvin, and J. Goudsmit. 2004. Immunogenicity of recombinant adenovirus serotype 35 vaccine in the presence of pre-existing anti-Ad5 immunity. J. Immunol. 172:6290-6297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belyakov, I. M., J. D. Ahlers, G. J. Nabel, B. Moss, and J. A. Berzofsky. 2008. Generation of functionally active HIV-1 specific CD8+ CTL in intestinal mucosa following mucosal, systemic or mixed prime-boost immunization. Virology 381:106-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belyakov, I. M., M. A. Derby, J. D. Ahlers, B. L. Kelsall, P. Earl, B. Moss, W. Strober, and J. A. Berzofsky. 1998. Mucosal immunization with HIV-1 peptide vaccine induces mucosal and systemic cytotoxic T lymphocytes and protective immunity in mice against intrarectal recombinant HIV-vaccinia challenge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:1709-1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belyakov, I. M., Z. Hel, B. Kelsall, V. A. Kuznetsov, J. D. Ahlers, J. Nacsa, D. I. Watkins, T. M. Allen, A. Sette, J. Altman, R. Woodward, P. D. Markham, J. D. Clements, G. Franchini, W. Strober, and J. A. Berzofsky. 2001. Mucosal AIDS vaccine reduces disease and viral load in gut reservoir and blood after mucosal infection of macaques. Nat. Med. 7:1320-1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belyakov, I. M., D. Isakov, Q. Zhu, A. Dzutsev, and J. A. Berzofsky. 2007. A novel functional CTL avidity/activity compartmentalization to the site of mucosal immunization contributes to protection of macaques against simian/human immunodeficiency viral depletion of mucosal CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 178:7211-7221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Betts, M. R., and R. A. Koup. 2004. Detection of T-cell degranulation: CD107a and b. Methods Cell Biol. 75:497-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bivas-Benita, M., R. Zwier, H. E. Junginger, and G. Borchard. 2005. Non-invasive pulmonary aerosol delivery in mice by the endotracheal route. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 61:214-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brenchley, J. M., D. A. Price, T. W. Schacker, T. E. Asher, G. Silvestri, S. Rao, Z. Kazzaz, E. Bornstein, O. Lambotte, D. Altmann, B. R. Blazar, B. Rodriguez, L. Teixeira-Johnson, A. Landay, J. N. Martin, F. M. Hecht, L. J. Picker, M. M. Lederman, S. G. Deeks, and D. C. Douek. 2006. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat. Med. 12:1365-1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brenchley, J. M., T. W. Schacker, L. E. Ruff, D. A. Price, J. H. Taylor, G. J. Beilman, P. L. Nguyen, A. Khoruts, M. Larson, A. T. Haase, and D. C. Douek. 2004. CD4+ T cell depletion during all stages of HIV disease occurs predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract. J. Exp. Med. 200:749-759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casimiro, D. R., L. Chen, T. M. Fu, R. K. Evans, M. J. Caulfield, M. E. Davies, A. Tang, M. Chen, L. Huang, V. Harris, D. C. Freed, K. A. Wilson, S. Dubey, D. M. Zhu, D. Nawrocki, H. Mach, R. Troutman, L. Isopi, D. Williams, W. Hurni, Z. Xu, J. G. Smith, S. Wang, X. Liu, L. Guan, R. Long, W. Trigona, G. J. Heidecker, H. C. Perry, N. Persaud, T. J. Toner, Q. Su, X. Liang, R. Youil, M. Chastain, A. J. Bett, D. B. Volkin, E. A. Emini, and J. W. Shiver. 2003. Comparative immunogenicity in rhesus monkeys of DNA plasmid, recombinant vaccinia virus, and replication-defective adenovirus vectors expressing a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag gene. J. Virol. 77:6305-6313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Contag, C. H., P. R. Contag, J. I. Mullins, S. D. Spilman, D. K. Stevenson, and D. A. Benaron. 1995. Photonic detection of bacterial pathogens in living hosts. Mol. Microbiol. 18:593-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Croyle, M. A., A. Patel, K. N. Tran, M. Gray, Y. Zhang, J. E. Strong, H. Feldmann, and G. P. Kobinger. 2008. Nasal delivery of an adenovirus-based vaccine bypasses pre-existing immunity to the vaccine carrier and improves the immune response in mice. PLoS One 3:e3548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darrah, P. A., D. T. Patel, P. M. De Luca, R. W. Lindsay, D. F. Davey, B. J. Flynn, S. T. Hoff, P. Andersen, S. G. Reed, S. L. Morris, M. Roederer, and R. A. Seder. 2007. Multifunctional TH1 cells define a correlate of vaccine-mediated protection against Leishmania major. Nat. Med. 13:843-850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallichan, W. S., and K. L. Rosenthal. 1996. Long-lived cytotoxic T lymphocyte memory in mucosal tissues after mucosal but not systemic immunization. J. Exp. Med. 184:1879-1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harari, A., S. Petitpierre, F. Vallelian, and G. Pantaleo. 2004. Skewed representation of functionally distinct populations of virus-specific CD4 T cells in HIV-1-infected subjects with progressive disease: changes after antiretroviral therapy. Blood 103:966-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heritage, P. L., B. J. Underdown, A. L. Arsenault, D. P. Snider, and M. R. McDermott. 1997. Comparison of murine nasal-associated lymphoid tissue and Peyer's patches. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 156:1256-1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogquist, K. A., S. C. Jameson, W. R. Heath, J. L. Howard, M. J. Bevan, and F. R. Carbone. 1994. T cell receptor antagonist peptides induce positive selection. Cell 76:17-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huster, K. M., V. Busch, M. Schiemann, K. Linkemann, K. M. Kerksiek, H. Wagner, and D. H. Busch. 2004. Selective expression of IL-7 receptor on memory T cells identifies early CD40L-dependent generation of distinct CD8+ memory T cell subsets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:5610-5615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaufman, D. R., J. Goudsmit, L. Holterman, B. A. Ewald, M. Denholtz, C. Devoy, A. Giri, L. E. Grandpre, J. M. Heraud, G. Franchini, M. S. Seaman, M. J. Havenga, and D. H. Barouch. 2008. Differential antigen requirements for protection against systemic and intranasal vaccinia virus challenges in mice. J. Virol. 82:6829-6837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaufman, D. R., J. Liu, A. Carville, K. G. Mansfield, M. J. Havenga, J. Goudsmit, and D. H. Barouch. 2008. Trafficking of antigen-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes to mucosal surfaces following intramuscular vaccination. J. Immunol. 181:4188-4198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ko, S. Y., C. Cheng, W. P. Kong, L. Wang, M. Kanekiyo, D. Einfeld, C. R. King, J. G. Gall, and G. J. Nabel. 2009. Enhanced induction of intestinal cellular immunity by oral priming with enteric adenovirus 41 vectors. J. Virol. 83:748-756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lackner, A. A., M. Mohan, and R. S. Veazey. 2009. The gastrointestinal tract and AIDS pathogenesis. Gastroenterology 136:1965-1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemckert, A. A., S. M. Sumida, L. Holterman, R. Vogels, D. M. Truitt, D. M. Lynch, A. Nanda, B. A. Ewald, D. A. Gorgone, M. A. Lifton, J. Goudsmit, M. J. Havenga, and D. H. Barouch. 2005. Immunogenicity of heterologous prime-boost regimens involving recombinant adenovirus serotype 11 (Ad11) and Ad35 vaccine vectors in the presence of anti-ad5 immunity. J. Virol. 79:9694-9701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, Q., L. Duan, J. D. Estes, Z. M. Ma, T. Rourke, Y. Wang, C. Reilly, J. Carlis, C. J. Miller, and A. T. Haase. 2005. Peak SIV replication in resting memory CD4+ T cells depletes gut lamina propria CD4+ T cells. Nature 434:1148-1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, Z., M. Zhang, C. Zhou, X. Zhao, N. Iijima, and F. R. Frankel. 2008. Novel vaccination protocol with two live mucosal vectors elicits strong cell-mediated immunity in the vagina and protects against vaginal virus challenge. J. Immunol. 180:2504-2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin, S. W., A. S. Cun, K. Harris-McCoy, and H. C. Ertl. 2007. Intramuscular rather than oral administration of replication-defective adenoviral vaccine vector induces specific CD8+ T cell responses in the gut. Vaccine 25:2187-2193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu, J., K. L. O'Brien, D. M. Lynch, N. L. Simmons, A. La Porte, A. M. Riggs, P. Abbink, R. T. Coffey, L. E. Grandpre, M. S. Seaman, G. Landucci, D. N. Forthal, D. C. Montefiori, A. Carville, K. G. Mansfield, M. J. Havenga, M. G. Pau, J. Goudsmit, and D. H. Barouch. 2009. Immune control of an SIV challenge by a T-cell-based vaccine in rhesus monkeys. Nature 457:87-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mattapallil, J. J., D. C. Douek, B. Hill, Y. Nishimura, M. Martin, and M. Roederer. 2005. Massive infection and loss of memory CD4+ T cells in multiple tissues during acute SIV infection. Nature 434:1093-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pantaleo, G., and R. A. Koup. 2004. Correlates of immune protection in HIV-1 infection: what we know, what we don't know, what we should know. Nat. Med. 10:806-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel, A., Y. Zhang, M. Croyle, K. Tran, M. Gray, J. Strong, H. Feldmann, J. M. Wilson, and G. P. Kobinger. 2007. Mucosal delivery of adenovirus-based vaccine protects against Ebola virus infection in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 196(Suppl. 2):S413-S420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ranasinghe, C., S. J. Turner, C. McArthur, D. B. Sutherland, J. H. Kim, P. C. Doherty, and I. A. Ramshaw. 2007. Mucosal HIV-1 pox virus prime-boost immunization induces high-avidity CD8+ T cells with regime-dependent cytokine/granzyme B profiles. J. Immunol. 178:2370-2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts, D. M., A. Nanda, M. J. Havenga, P. Abbink, D. M. Lynch, B. A. Ewald, J. Liu, A. R. Thorner, P. E. Swanson, D. A. Gorgone, M. A. Lifton, A. A. Lemckert, L. Holterman, B. Chen, A. Dilraj, A. Carville, K. G. Mansfield, J. Goudsmit, and D. H. Barouch. 2006. Hexon-chimaeric adenovirus serotype 5 vectors circumvent pre-existing anti-vector immunity. Nature 441:239-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rubio, V., T. B. Stuge, N. Singh, M. R. Betts, J. S. Weber, M. Roederer, and P. P. Lee. 2003. Ex vivo identification, isolation and analysis of tumor-cytolytic T cells. Nat. Med. 9:1377-1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santosuosso, M., X. Zhang, S. McCormick, J. Wang, M. Hitt, and Z. Xing. 2005. Mechanisms of mucosal and parenteral tuberculosis vaccinations: adenoviral-based mucosal immunization preferentially elicits sustained accumulation of immune protective CD4 and CD8 T cells within the airway lumen. J. Immunol. 174:7986-7994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sené, C., A. Bout, J. L. Imler, H. Schultz, J. M. Willemot, V. Hennebel, C. Zurcher, D. Valerio, D. Lamy, and A. Pavirani. 1995. Aerosol-mediated delivery of recombinant adenovirus to the airways of nonhuman primates. Hum. Gene Ther. 6:1587-1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith, D. J., S. Bot, L. Dellamary, and A. Bot. 2003. Evaluation of novel aerosol formulations designed for mucosal vaccination against influenza virus. Vaccine 21:2805-2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Southam, D. S., M. Dolovich, P. M. O'Byrne, and M. D. Inman. 2002. Distribution of intranasal instillations in mice: effects of volume, time, body position, and anesthesia. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 282:L833-L839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stevceva, L., X. Alvarez, A. A. Lackner, E. Tryniszewska, B. Kelsall, J. Nacsa, J. Tartaglia, W. Strober, and G. Franchini. 2002. Both mucosal and systemic routes of immunization with the live, attenuated NYVAC/simian immunodeficiency virus SIV(gpe) recombinant vaccine result in gag-specific CD8(+) T-cell responses in mucosal tissues of macaques. J. Virol. 76:11659-11676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tatsis, N., S. W. Lin, K. Harris-McCoy, D. A. Garber, M. B. Feinberg, and H. C. Ertl. 2007. Multiple immunizations with adenovirus and MVA vectors improve CD8+ T cell functionality and mucosal homing. Virology 367:156-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veazey, R. S., M. DeMaria, L. V. Chalifoux, D. E. Shvetz, D. R. Pauley, H. L. Knight, M. Rosenzweig, R. P. Johnson, R. C. Desrosiers, and A. A. Lackner. 1998. Gastrointestinal tract as a major site of CD4+ T cell depletion and viral replication in SIV infection. Science 280:427-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang, J., L. Thorson, R. W. Stokes, M. Santosuosso, K. Huygen, A. Zganiacz, M. Hitt, and Z. Xing. 2004. Single mucosal, but not parenteral, immunization with recombinant adenoviral-based vaccine provides potent protection from pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 173:6357-6365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang, L., C. Cheng, S. Y. Ko, W. P. Kong, M. Kanekiyo, D. Einfeld, R. M. Schwartz, C. R. King, J. G. Gall, and G. J. Nabel. 2009. Delivery of human immunodeficiency virus vaccine vectors to the intestine induces enhanced mucosal cellular immunity. J. Virol. 83:7166-7175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams, M. A., and M. J. Bevan. 2007. Effector and memory CTL differentiation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25:171-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu, Q., C. W. Thomson, K. L. Rosenthal, M. R. McDermott, S. M. Collins, and J. Gauldie. 2008. Immunization with adenovirus at the large intestinal mucosa as an effective vaccination strategy against sexually transmitted viral infection. Mucosal Immunol. 1:78-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]