Abstract

Proteomics is a powerful tool to understand the molecular mechanisms causing the production of high penicillin titers by industrial strains of the filamentous fungus Penicillium chrysogenum as the result of strain improvement programs. Penicillin biosynthesis is an excellent model system for many other bioactive microbial metabolites. The recent publication of the P. chrysogenum genome has established the basis to understand the molecular processes underlying penicillin overproduction. We report here the proteome reference map of P. chrysogenum Wisconsin 54-1255 (the genome project reference strain) together with an in-depth study of the changes produced in three different strains of this filamentous fungus during industrial strain improvement. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, peptide mass fingerprinting, and tandem mass spectrometry were used for protein identification. Around 1000 spots were visualized by “blue silver” colloidal Coomassie staining in a non-linear pI range from 3 to 10 with high resolution, which allowed the identification of 950 proteins (549 different proteins and isoforms). Comparison among the cytosolic proteomes of the wild-type NRRL 1951, Wisconsin 54-1255 (an improved, moderate penicillin producer), and AS-P-78 (a penicillin high producer) strains indicated that global metabolic reorganizations occurred during the strain improvement program. The main changes observed in the high producer strains were increases of cysteine biosynthesis (a penicillin precursor), enzymes of the pentose phosphate pathway, and stress response proteins together with a reduction in virulence and in the biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites different from penicillin (pigments and isoflavonoids). In the wild-type strain, we identified enzymes to utilize cellulose, sorbitol, and other carbon sources that have been lost in the high penicillin producer strains. Changes in the levels of a few specific proteins correlated well with the improved penicillin biosynthesis in the high producer strains. These results provide useful information to improve the production of many other bioactive secondary metabolites.

Penicillium chrysogenum is a filamentous fungus (ascomycete) with the ability to synthesize penicillin (Fig. 1A) and related β-lactam antibiotics (1) in addition to several other secondary metabolites (2). Penicillins have greatly contributed to the improvement of human health since Alexander Fleming's discovery of antibiotic production by Penicillium notatum (3). Because of the very low amounts of penicillin (about 2 IU/ml or 1.2 μg/ml) yielded by Fleming's original P. notatum strain (NRRL 1249B21), the isolation of new strains became of paramount importance. An improvement of the process (Fig. 1B) occurred in 1943 with the isolation of P. chrysogenum NRRL 1951 from an infected cantaloupe in Peoria, IL (4). This microorganism was more suitable than P. notatum for penicillin production (60–150 μg/ml) in submerged cultures. The P. chrysogenum NRRL 1951 (wild type) was x-ray-treated, giving rise to the X-1612 mutant that was able to yield 300 μg/ml penicillin and was subjected to ultraviolet mutation at the University of Wisconsin. After several rounds of classical mutagenesis, the Q-176 strain, which produces 550 μg/ml penicillin, was obtained. This strain is the original ancestor of the Wisconsin line of strains; the improved producer Wisconsin 54-1255 (hereafter named Wis1 54-1255) has become a laboratory model strain (5–7). Later, this strain gave rise to penicillin high producer strains, such as the P2 strain of Panlabs (Taipei, Taiwan) (8), the DS04825 strain obtained at DSM (Heerlen, The Netherlands) (9), or the AS-P-78 and the E1 strains, which were obtained at Antibioticos S.A. (León, Spain) (10). These strains are the parents of those overproducer mutants currently used for the industrial production of penicillin that reach titers of more than 50,000 μg/ml in fed batch cultures.

Fig. 1.

A, penicillin biosynthetic pathway. The schematic representation shows the genes and proteins involved in different steps of the biosynthesis of benzylpenicillin. The estimated mass for each enzyme of the pathway is also indicated. B, genealogy of some P. chrysogenum strains during industrial strain improvement programs. Thin arrows represent either steps of selection (without mutagenic treatment) or x-ray irradiation, UV irradiation, or nitrogen mustard treatment. Arrows between strains BL3-D10 and Wisconsin 54-1255 represents a total of nine selection steps. The thick arrows between the Wis 54-1255 strain and the high producer strains represent several selection steps in different industrial laboratories. The names of the strains used in this work are boxed. Penicillin titers are indicated on the right for some of these strains.

The mutagenesis undergone by the P. chrysogenum strains has introduced several important modifications. Biochemical and genetic analyses have allowed the identification of some of these modifications. It is well known that the homogentisate pathway for the catabolism of phenylacetic acid (the side chain precursor in the biosynthesis of benzylpenicillin) is diminished in Wis 54-1255 and presumably in derived strains as well. This is due to modifications in a microsomal cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (encoded by the pahA gene) that lead to a reduced degradation of phenylacetic acid and to penicillin overproduction (11). Another well characterized modification resulting from the industrial improvement process is the amplification of the genomic region that includes the three penicillin biosynthetic genes. These genes, pcbAB, pcbC, and penDE, are linked in a single cluster located on a DNA region that is amplified in tandem repeats in penicillin-overproducing strains (10, 12, 13). This region is present as a single copy in the genome of the wild-type NRRL 1951 and Wis 54-1255 strains, but many of the improved penicillin producers contain several copies of the amplified region, like the AS-P-78 strain, which contains five or six copies (10). Microbodies (peroxisomes), organelles involved in the final steps of the penicillin pathway catalyzed by the acyl-coenzyme A:isopenicillin N (IPN) acyltransferase and phenylacetyl-CoA ligase (14–16), are also known to be more abundant in high producer strains (14, 17).

Despite this background knowledge, little is known regarding how P. chrysogenum became such a good penicillin overproducer, and much of the molecular basis for improved productivity remains obscure. Some light has been shed on this issue after the recent publication of the P. chrysogenum genome (17). These authors reported that transcription of genes involved in biosynthesis of the amino acid precursors for penicillin biosynthesis as well as of genes encoding microbody proteins was higher in the high producer strain DS17690. Full exploitation of P. chrysogenum requires the integration of knowledge from other -omics, such as proteomics.

Proteomics studies are one of the most powerful methods to evaluate the final result of gene expression, and 2-DE has been the technique of choice to obtain a reference global picture of the proteome map. This technique has been successfully applied to other ascomycete fungi, such as Schizosaccharomyces pombe (18), some Aspergillus species (19–21), and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (22, 23). Kiel et al. (24) have performed a proteomics-based inventory of the proteins present in the microbody matrix of P. chrysogenum.

In this work, we optimized a method to extract the P. chrysogenum cytosolic proteins. As a result, the cytosolic reference map for this filamentous fungus was developed. In addition, we characterized the relevant modifications produced during the industrial strain improvement program through the proteome analysis of three P. chrysogenum strains: the wild-type strain NRRL 1951 isolated in Peoria, IL; the genome reference strain Wis 54-1255 (an improved but still low producer); and the high producer strain AS-P-78 developed by Antibioticos S.A.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains and Growth Conditions

Three strains of P. chrysogenum were used in this work (Fig. 1): the wild-type NRRL 1951, the Wis 54-1255 (reference strain for the genome sequencing project), and the high producer strain AS-P-78 (kindly provided to us by Antibioticos S.A.). These strains were grown on solid Power medium (25) for 7 days at 28 °C. Conidia from one Petri dish were collected and inoculated into a flask with 100 ml of defined PMMY medium (3.0 g/liter NaNO3, 2.0 g/liter yeast extract, 0.5 g/liter NaCl, 0.5 g/liter MgSO4·7H2O, 0.01 g/liter FeSO4·7H2O, and 40.0 g/liter glucose). Cultures were incubated for 48 h (for the reference map) or 40 h (for the comparison experiments among strains) at 25 °C and 250 rpm, and the mycelia were collected by filtration through a Nytal membrane, washed once with 0.9% NaCl and twice with ddH2O, and stored at −80 °C.

RT-PCR Experiments

Gene expression was analyzed by RT-PCR. Total RNA was extracted from mycelium grown for 40 and 60 h in PMMY medium. RNA treatments and RT-PCR were performed as described before (26). The primers used to amplify the cDNA of the pcbC gene have been described previously (26). The cDNA of the penDE gene was amplified using the following primers: F, 5′-ATGCTTCACATCCTCTGTCAAGG-3′; and R, 5′-TCAAAGCCTGGCGTTGAGCGC-3′. The β-actin transcript was used as control and was amplified using the following primers: F, 5′-CTGGCCGTGATCTGACCGACTAC-3′; and R, 5′-GGGGGAGCGATGATCTTGACCT-3′. The intensity of the PCR bands was determined by densitometry as described before (26) using the “Gel-Pro Analyzer” software (Media Cybernetics).

Sample Preparation and Optimization of Protein Extraction Protocol

Frozen mycelia were ground to a fine powder in a precooled mortar using liquid nitrogen. Different procedures were used to optimize this protocol for P. chrysogenum proteins (see “Results”). The final optimal method (based on that described by Fernández-Acero et al. (27) for the fungus Botrytis cinerea) is detailed below and consisted of solubilizing proteins by phosphate buffer and precipitation with TCA/acetone.

Two grams of cells were resuspended in 10 ml of 10 mm potassium phosphate buffer (K2HPO4:KH2PO4) (pH 7.4) (ratio, 1 g/5 ml) containing 0.07% (w/v) DTT and supplemented with tablets (one tablet/10 ml of buffer) of the protease inhibitor mixture CompleteTM (Roche Applied Science). The mixture was stirred at 4 °C for 2 h, and the extract was clarified twice by centrifugation at 13,200 rpm for 5 min. Proteins were precipitated for 1 h at −20 °C after the addition of 1 volume of 20% TCA in acetone containing 0.14% (w/v) DTT. The final pellet was washed twice with acetone followed by a final wash with 80% acetone and solubilized in 500 μl of sample buffer (8 m urea, 2% (w/v) CHAPS, 0.5% (v/v) IPG Buffer pH 3–10 non-linear (NL) (GE Healthcare), 20 mm DTT, 0.002% bromphenol blue). The insoluble fraction was discarded by centrifugation at 13,200 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was collected, and protein concentration was determined according to the Bradford method. This extraction procedure showed a high reproducibility in 10 repeated experiments.

2-DE Gel Electrophoresis

A solution containing 100 μg for silver staining or 350 μg for colloidal Coomassie (CC) staining of soluble proteins in the sample buffer (see above) was loaded onto 18-cm IPG strips (GE Healthcare) with an NL pH 3–10 gradient. Proteins were focused at 20 °C according to the following program: 1 h, 0 V and 12 h, 30 V (rehydration); 2 h, 60 V; 1 h, 500 V; 1 h, 1,000 V; 30-min gradient to 8,000 V; up to 7 h, 8,000 V until 50 kV-h. Focused IPG gels were equilibrated twice for 15 min in a buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 6 m urea, 30% (v/v) glycerol, 2% (w/v) SDS, 0.002% bromphenol blue, and 1% (w/v) DTT. For the second equilibration step, DTT was replaced by 4.0% (w/v) iodoacetamide. The second dimension was SDS-PAGE in 15% (for the reference map) or 12.5% (for comparison experiments) polyacrylamide in an Ettan Dalt Six apparatus (GE Healthcare) for 45 min at 3 watts/gel and then for 4 h at 18 watts/gel. Precision Plus Protein Standards (Bio-Rad) were used as markers. Gels were silver-stained following an MS-compatible protocol (GE Healthcare) or dyed with CC following the “blue silver” staining method (28), which provides high reproducibility, by using 0.12% Coomassie Blue G-250 (Sigma), 10% ammonium sulfate, 10% phosphoric acid, and 20% methanol.

Analysis of Differential Protein Expression

Two-dimensional images were captured by scanning stained gels using an ImageScanner II (GE Healthcare) previously calibrated by using a grayscale marker (Eastman Kodak Co.), digitalized with Labscan 5.00 (v1.0.8) software (GE Healthcare), and analyzed with the ImageMasterTM 2D Platinum v5.0 software (GE Healthcare). Three gels of each strain obtained from three independent cultures (biological replicates) were analyzed to guarantee representative results. After automated spot detection, spots were checked manually to eliminate any possible artifacts, such as streaks or background noise. The patterns of each sample were overlapped and matched, using landmark features, to detect potential differentially expressed proteins. Each strain showed less than 10% variability in the number of protein spots detected among biological replicates. Spot normalization, as an internal calibration to make the data independent from experimental variations among gels, was made using relative volumes to quantify and compare the gel spots. Relative volume corresponds to the volume of each spot divided by the total volume of all the spots in the gel. Differentially expressed proteins were considered when the ratio of the relative volume average (three gels) between strains was higher than 1.5 and the p value was <0.05.

Protein Identification by MALDI-TOF MS and MS/MS

The protein spots of interest were manually excised from colloidal Coomassie-stained gels by biopsy punches, placed in an Eppendorf tube, and washed twice with ddH2O. The proteins were digested following the method of Havlis et al. (29): samples were dehydrated with ACN (Carlo Erba) for 5 min, reduced with 10 mm DTT (GE Healthcare) in 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate (Fluka) for 30 min at 56 °C, and subsequently alkylated with 55 mm iodoacetamide (MS grade; Sigma) in 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate for 15 min in the dark. Finally, samples were digested overnight at 37 °C with 10.0 ng/μl modified porcine trypsin (sequencing grade; Promega) in 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate (pH 8.5). After digestion, the supernatant was collected, speed vacuum-dried, and resuspended in 4 μl of 50% ACN, 0.1% TFA in ddH2O. One microliter was spotted on a MALDI target plate and air-dried for 10 min at room temperature. Subsequently, 0.5 μl of matrix (3 mg/ml α-cyano-4-hydroxytranscinnamic acid (LaserBio Labs)) diluted in 0.1% TFA in ACN/H2O (1:1, v/v) was added to the dried peptide digestion and air-dried for another 5 min at room temperature. The samples were analyzed with a 4800 Proteomics Analyzer MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems). A 4700 Proteomics Analyzer calibration mixture (Cal Mix 5; Applied Biosystems) was used as external calibration. All MS spectra were internally calibrated using peptides from the trypsin digestion. The analysis by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry produced peptide mass fingerprints, and the peptides observed (up to 65 peptides per spot) were collected and represented as a list of monoisotopic molecular weights with a signal to noise ratio greater than 20 using the 4000 Series Explorer v3.5.3 software (Applied Biosystems). All known contaminant ions (trypsin- and keratin-derived peptides) were excluded for protein database searching and for later MS/MS analysis. Hence, from each MS spectra, the six most intensive precursors with a signal to noise ratio greater than 20 were selected for MS/MS analyses with CID (atmospheric gas was used) in 2-kV ion reflector mode and with precursor mass windows of ±7 Da. The plate model and default calibration were optimized for the processing of MS/MS spectra.

For protein identification, Mascot generic files combining MS and MS/MS spectra were automatically created and used to interrogate a nonredundant protein database using a local license of Mascot v2.2 from Matrix Science through the Protein Global Server (GPS) v3.6 (Applied Biosystems). The search parameters for peptide mass fingerprints and tandem MS spectra obtained were set as follows: (i) NCBInr (November 11, 2008) sequence databases were used; (ii) taxonomy was total (7,387,702 sequences) and fungi (433,354 sequences); (iii) fixed and variable modifications were considered (Cys as S-carbamidomethyl derivative and Met as oxidized methionine); (iv) one missed cleavage site was allowed; (v) precursor tolerance was 100 ppm, and MS/MS fragment tolerance was 0.3 Da; (vi) peptide charge was 1+; and (vii) the algorithm was set to use trypsin as the enzyme. Protein candidates produced by this combined peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF)/tandem MS search were considered valid when the global Mascot score was greater than 81 (total database) or 69 (fungi database) with a significance level of p < 0.05. Additional criteria for confident identification were that the protein match should have at least 15% sequence coverage and, for lower coverages, only those proteins with a Mascot ion score above 40 in the tandem MS analysis (with a significance level of p < 0.05) were considered valid.

RESULTS

Optimization of 2-DE for P. chrysogenum Wis 54-1255

To obtain soluble protein extracts optimal for 2-DE analysis, two approaches were followed: (i) a protocol based on the Clean Up kit (GE Healthcare) extraction described by Kniemeyer et al. (20) and (ii) a procedure based on phosphate buffer solubilization and protein precipitation (with either TCA or acetone) described by Fernández-Acero et al. (27) for B. cinerea. In addition, silver or CC staining conditions were analyzed. Each condition was tested at least three times using three biological replicates. Good results were obtained using the Clean Up kit protocol, but some streaking was detected under silver staining conditions (supplemental Fig. 1A). The streaks were almost fully avoided by using the phosphate buffer procedure combined with TCA precipitation (supplemental Fig. 1, C and D). The acetone precipitation showed the worst results (supplemental Fig. 1B). In addition to the phosphate buffer and TCA precipitation, the CC (blue silver) stain achieved the best staining results (supplemental Fig. 1D). Protein extracts of P. chrysogenum AS-P-78 needed an extra cleaning step by using the Clean Up kit before IEF to avoid the streaking in the acidic sector of the gel.

Reference Map Analysis: Proteome Overview

After optimization of the protein extraction protocol, a global proteome analysis of P. chrysogenum Wis 54-1255 was performed. This strain was selected because it was the reference strain for the genome sequencing project (17). The global reference map of this fungus was obtained using wide range IPG strips (pH 3–10 NL) and 15% SDS-PAGE, which allowed a wide overview of the P. chrysogenum soluble protein distribution. Spots were visualized with blue silver staining, which allowed the detection of 976 protein spots by digital image analysis (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Reference map of cytosolic P. chrysogenum proteome and functional classification of identified proteins. A, proteins were separated by 2-DE using 18-cm wide range IPG strips (pH 3–10 NL) and 15% SDS-PAGE and stained with CC following the blue silver staining method. A total amount of 976 spots were resolved in this range and were analyzed by PMF and tandem mass spectrometry (see supplemental Table 1). Molecular masses are shown on the left. Assigned numbers over each spot correlate with those shown in supplemental Table 1. B, the 950 identified proteins (549 different proteins and isoforms) were classified according to their biological function.

Approximately 92% of the 976 spots detected were located between 10 and 100 kDa in a pH range from 3 to 10 (Fig. 2A). Stained spots were excised from the gel, digested as indicated under “Experimental Procedures,” and analyzed by PMF and tandem MS. From the total 976 spots detected, 128 spots could not be identified. The remaining 848 spots represented 950 correctly identified proteins (with an average error of 12 ppm) because some spots contained more than one protein (supplemental Table 1).

Almost all the significant Mascot searches provided an exact match with proteins inferred from the P. chrysogenum Wis 54-1255 genome, indicating high accuracy of the genome annotation process. However, there were some exceptions (supplemental Data 1). From the 950 proteins identified, 211 proteins showed a total of 612 isoforms (supplemental Table 2). The final number of different proteins identified was 549. Some examples of the proteins showing a high number of isoforms were a probable flavohemoglobin, Fhp (Pc12g14620; 14 isoforms); a probable catalase R (Pc16g11860; 12 isoforms); a glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase-like protein (Pc22g10040; 10 isoforms); a probable endonuclease, SceI 75-kDa subunit Ens1 (Pc22g19990; eight isoforms); and a hypothetical trunk lateral cell-specific gene, HrTLC1 (Pc18g00980; eight isoforms).

The 10 spots showing more intensity (relative volume) represented 13.01% of the total spot volume where spots 352 and 364, corresponding to a probable flavohemoglobin, Fhp (Pc12g14620), constituted 4.63% of the total percent volume. The reference map with a direct link to the identified proteins is available upon request.

Functional Classification of Proteins

The 950 proteins identified (549 different proteins and isoforms) were functionally classified according to their biological roles using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes and FunCat classification system (31). As shown in Fig. 2B and supplemental Table 1, 415 proteins were involved in energy formation and metabolism (43.68%); 103 proteins were involved in folding, modification, and targeting of proteins (10.84%); 76 proteins were involved in cell rescue, defense, and virulence (8.00%); 68 proteins were involved in transcription and translation processes (7.16%); and 149 proteins (15.68%) were involved in other different cellular processes. We also identified 139 proteins of unknown function (e.g. hypothetical proteins) (14.64%).

Penicillin Biosynthetic Enzymes and Other Secondary Metabolism Proteins

It is well established that there are three proteins directly involved in the penicillin biosynthetic pathway (Fig. 1A): α-aminoadipyl-cysteinyl-valine (ACV) synthetase, IPN synthase, and acyl-coenzyme A:isopenicillin N acyltransferase (for a recent review, see Ref. 16). The first enzyme in the pathway (ACV synthetase) is a non-ribosomal peptide synthetase with an estimated mass of 425 kDa so that its detection was not possible by 2-DE. The other enzymes of the pathway were identified in the reference map (Fig. 2A and supplemental Table 1). The IPN synthase was present in spot 427 (Pc21g21380), and the acyl-coenzyme A:isopenicillin N acyltransferase was found in spot 647 (Pc21g21370). Only the 29-kDa β-subunit of this enzyme could be identified in agreement with previous results (32) (see “Discussion”). One of the putative orthologs of the bacterial IPN epimerase, CefD (33), described in the P. chrysogenum genome (Pc12g11540) was identified in the reference map with two isoforms (spots 247 and 250); this protein probably functions as an aminotransferase as suggested previously (17). A probable 7-α-cephem-methoxylase subunit, CmcJ, was identified in spots 399 and 404 (Pc13g04680). This enzyme is present in cephamycin-producing organisms, such as Amycolatopsis lactamdurans, and together with CmcI, is involved in the synthesis of 7-α-methoxylated cephems (34). Because the P. chrysogenum genome only contains genes encoding putative CmcJ subunits of this enzyme and this microorganism does not produce cephalosporins, it is difficult to assign a specific role in β-lactam biosynthesis to this protein.

Enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites were also found (Fig. 2A and supplemental Table 1). Lovastatin, a fungal secondary metabolite capable of lowering the cholesterol level in blood, is synthesized by two polyketide synthases and several accessory enzymes, including an enoyl reductase, LovC (35). Six spots, including putative enoyl reductases of the lovastatin pathway (spots 450 and 461, Pc20g05830; and spots 456, 471, 474, and 476, Pc12g14200), were identified in the reference map. One of the enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of phenazines (chorismic acid derivatives with antibiotic properties) is an oxidoreductase (PhzF) (36), which was identified in spot 490 (Pc13g06860). Versicolorin A is a key intermediate in the biosynthesis of sterigmatocystin and aflatoxins. Biosynthesis of aflatoxins involves a set of proteins (37), including a versicolorin reductase, VerA (38, 39), which is present in spot 684 (Pc22g06690). A protein with weak similarity to isoflavone reductase (Pc18g00110) is included in spot 465. Isoflavone reductase was identified as a key enzyme involved in the late part of the medicarpin biosynthetic pathway; medicarpin is the major isoflavonoid phytoalexin found in alfalfa (Medicago sativa) responding to fungal pathogen attack (40).

Protein Differences Produced during Early Improvement of P. chrysogenum NRRL 1951

To find the changes introduced during the early strain improvement program, the wild-type strain NRRL 1951 was compared with the improved but still low producing Wis 54-1255. Analysis of the 2-DE gels (Fig. 3) identified 45 spots that were overrepresented in the NRRL 1951 strain (including 38 different proteins and isoforms), whereas in the Wis 54-1255, 29 spots (27 different proteins and isoforms) had higher representation compared with the wild-type strain (Fig. 4). Supplemental Tables 3 and 4 display the findings summarized below.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of intracellular proteomes of wild-type NRRL 1951 and Wis 54-1255 strains. 2-DE gels of the intracellular proteomes of the NRRL 1951 and the Wis 54-1255 strains grown for 40 h under the same conditions are shown. Proteins were separated by 2-DE using 18-cm wide range IPG strips (pH 3–10 NL) and 12.5% SDS-PAGE and stained with CC following the blue silver staining method. The designation “N” is used for those spots overrepresented in the NRRL 1951 strain, and “Ws” is used for those spots overrepresented in the Wis 54-1255 strain. The spots differentially represented in each strain are numbered and correspond to those proteins listed in supplemental Table 3 (for the NRRL 1951 strain) and supplemental Table 4 (for the Wis 54-1255 strain).

Fig. 4.

Close-up view of spots differentially represented in either NRRL 1951 or Wis 54-1255 strains. Enlargements of gel portions containing the spots overrepresented in the gels of Fig. 3 are shown. The designation “N” is used for those spots overrepresented in the NRRL 1951 strain, and “Ws” is used for those spots overrepresented in the Wis 54-1255 strain. The number of those spots differentially represented is indicated and corresponds to those present in supplemental Table 3 (for the NRRL 1951 strain) and supplemental Table 4 (for the Wis 54-1255 strain).

Carbohydrate Metabolism and Energy

Some of the changes in the improved strain Wis 54-1255 with respect to the wild-type NRRL 1951 affect carbohydrate metabolism. A probable β-glucosidase 1 (spot N1) is 6-fold overrepresented in the wild-type strain. This enzyme is involved in cellulose degradation (41), which indicates the ability of the NRRL 1951 to utilize cellulose as a carbon source. In addition, a probable sorbitol utilization protein, Sou2 (spot N8), is 2.56-fold more represented in the NRRL 1951 strain, indicating the capacity of this fungus to use sorbitol (a sugar alcohol found in stone fruits) as a carbon source.

The wild-type strain contains three spots (N16, N20, and N21) that include isoforms of a probable aldehyde dehydrogenase that are absent in the Wis 54-1255 strain. Another protein that is only present in the wild-type strain (spot N23) is a putative NADP(+)-coupled glycerol dehydrogenase proposed to be involved in an alternative pathway for glycerol catabolism (42); it shows a high similarity to a glycerol dehydrogenase, Gcy1, from Aspergillus fumigatus (92% homology and 87% identity). One of the enzymes of the Leloir pathway for galactose metabolism, a probable UDP-glucose 4-epimerase, is also overrepresented in the wild-type strain (spot N19). On the other hand, the expression of a variety of proteins is increased in the improved penicillin producer Wis 54-1255. This is the case for spot Ws17 containing a probable polygalacturonase for pectate and other galacturonan degradation that is overrepresented in the Wis 54-1255 strain. Taken together, these results suggest that the wild-type NRRL 1951 strain has a capability to use a variety of carbon sources that has been restricted (or enhanced in the case of polygalacturonase) in Wis 54-1255.

It is noteworthy that some proteins related to glycolysis and energy formation are overrepresented in the Wis 54-1255 strain. This is the case of spots Ws1 (probable ATP citrate lyase involved in the formation of cytosolic acetyl-CoA), Ws4 (probable fructose-bisphosphate aldolase), Ws10 (probable core protein II of the ubiquinol cytochrome c reductase), Ws13 (probable α-subunit E1 of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex), and Ws15 (probable soluble cytoplasmic fumarate reductase likely involved in anaerobic respiration). It is also remarkable that the probable malate dehydrogenase is overrepresented as the precursor protein in the NRRL 1951 strain (spot N7), whereas in the Wis 54-1255 strain, the mature form of this protein is predominant (spot Ws16).

Penicillin Biosynthetic Precursors

The non-ribosomal condensation of the three precursor amino acids (l-α-aminoadipic acid, l-cysteine, and l-valine) is the initial step of penicillin biosynthesis. Some proteins involved in metabolism of amino acid precursors for penicillin biosynthesis are differentially represented in these two strains. Spot N4, which contains a hypothetical cystathionine β-synthase involved in the biosynthesis of cystathionine from cysteine, is overrepresented in the NRRL 1951 strain. Only the wild-type strain shows a probable methylmalonate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase (spot N15), which is involved in valine catabolism (43, 44) and may result in a reduced valine availability for penicillin biosynthesis in the wild-type strain as compared with the Wis 54-1255 strain. Vice versa, spot Ws6 (including a cysteine synthase) is 2.14-fold overrepresented in the Wis 54-1255 strain. These findings suggest a reduction in cysteine and valine catabolism and explain the enhancement of their biosynthesis during the early improvement program.

Pigmentation and Secondary Metabolism

It is noteworthy that in the wild-type strain analysis a variety of proteins involved in pigment formation were identified in agreement with the known ability of this strain to synthesize an increased amount of pigment. A putative zeaxanthin epoxidase, which catalyzes the conversion of zeaxanthin to violaxanthin (natural xanthophyll pigment with an orange color), is 11-fold overrepresented in the wild-type strain (spot N10). In addition, a putative scytalone dehydratase involved in the biosynthesis of melanin is only present in the wild-type strain (spot N24). This pigment has been reported to protect hyphae and spores from UV light, free radicals, and desiccation and also serves as a virulence factor (45).

Other proteins involved in secondary metabolism pathways overrepresented in the wild-type strain are a probable 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase (spot N18) and a probable coproporphyrinogen oxidase III (spot N22). The first enzyme is involved in the formation of hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA for terpenoid synthesis, whereas the second one is involved in porphyrin metabolism.

In general, the improved penicillin producer Wis 54-1255 strain contains a lower amount of proteins involved in the biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites. However, some examples of a positive correlation may occur; e.g. spot Ws2 is 2.61-fold overrepresented compared with the wild-type strain. This spot corresponds to a probable enoyl reductase of the lovastatin pathway that is involved in the biosynthesis of the lovastatin precursor dihydromonacolin N (see “Discussion”).

Virulence and Defense Mechanisms

Several proteins related to host infection and virulence that are abundant in the wild-type strain are underrepresented in the Wis 54-1255 strain. A probable glucose oxidase (spots N2 and N3), involved in oxidation of d-glucose to d-glucono-1,5-lactone (further hydrolyzed to gluconic acid), is highly overrepresented in the wild-type strain. This enzyme is involved in virulence because gluconic acid and glucose oxidase have been associated with the pathogenicity of Penicillium expansum in apples (46). Accordingly, spot N28, which includes a probable host infection protein, Cap20, is only present in the wild-type strain. This protein plays a significant role in the fungal virulence on avocado and tomato fruits (47).

Proteins involved in redox metabolism are predominant in the wild-type strain. This strain shows three isoforms of the catalase R (spots N26, N27, and N30). Two of them are not detected in the Wis 54-1255 strain (spots N26 and N27), and the third one (spot N30) is 5.5-fold underrepresented in the Wis 54-1255 strain. The thioredoxin reductase (spot N29) is also underrepresented in the Wis 54-1255 as compared with the wild-type strain (1.92 times).

Protein Targeting and Processing

A global view of the enzymes related to protein fate pathways shows that proteinases/peptidases are overrepresented in the improved penicillin producer Wis 54-1255 strain (spots Ws19, Ws24, Ws25, Ws26, and Ws27). Two of these spots (Ws26 and Ws27) contain isoforms of the same protein (Pc20g09400), which is a probable dipeptidyl-peptidase V. This protein was initially described in A. fumigatus and was the first report of a secreted dipeptidyl-peptidase (48), which is identical to one of the two major antigens used for the diagnosis of aspergillosis. A probable cyclophilin-like peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase, CypA (spots N32 and N35), is overrepresented in the wild-type strain.

Proteomics of High Producer Strain P. chrysogenum AS-P-78: Analysis of Protein Differences Leading to Industrial Penicillin Producers

To assess some of the modifications that occurred during the development of the high producer AS-P-78 from Wis 54-1255, extracted proteins from these two strains were compared with each other as indicated above. Analysis of the 2-DE gels (Fig. 5) identified 43 spots (including 41 different proteins and two isoforms) that were underrepresented in the AS-P-78 strain, whereas 52 spots (including 37 different proteins and isoforms) had higher representation in the AS-P-78 strain (Fig. 6). The findings summarized below are detailed in supplemental Tables 5 and 6.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of intracellular proteomes of Wis 54-1255 and high producer AS-P-78 strains. Representative 2-DE gels of the intracellular proteomes of the Wis 54-1255 and the AS-P-78 strains grown for 40 h under the same conditions are shown. Proteins were separated by 2-DE using 18-cm wide range IPG strips (pH 3–10 NL) and 12.5% SDS-PAGE and stained with CC following the blue silver staining procedure. The name “W” is used for those spots overrepresented in the Wis 54-1255 strain, whereas “A” is used for those spots overrepresented in the AS-P-78 strain. The number of each differentially represented spot is indicated and corresponds to those in supplemental Table 5 (for the Wis 54-1255 strain) and supplemental Table 6 (for the AS-P-78 strain).

Fig. 6.

Close-up view of spots differentially represented in either Wis 54-1255 or AS-P-78 strains. Enlargements of gel portions containing the spots overrepresented in the gels of Fig. 5 are shown. The designation “W” is used for those spots overrepresented in the Wis 54-1255 strain, and “A” is used for those spots overrepresented in the AS-P-78 strain. The number of each differentially represented spot is indicated and corresponds to those present in supplemental Table 5 (for the Wis 54-1255 strain) and supplemental Table 6 (for the AS-P-78 strain).

Carbohydrate Metabolism and Energy

Three isoforms of a probable ribose-5-phosphate isomerase RpiB (spots A13, A14, and A16) were only found in the AS-P-78 strain. This protein is involved in the non-oxidative pentose phosphate pathway. Connected to this pathway is the hypothetical protein included in spot A44, which is 3.82-fold overrepresented in the high producer strain. This protein shares a high similarity to a transketolase from Laccaria bicolor (78% homology and 65% identity). This enzyme connects the pentose phosphate pathway to glycolysis. Interestingly, spot A2, identified as a probable polygalacturonase (Pc22g20290), is 1.94-fold overrepresented in the high producing strain. As indicated above, the same polygalacturonase (spot Ws17) is 3.84-fold overrepresented in Wis 54-1255 with respect to the wild-type strain. This enzyme is in charge of pectate degradation and is involved in starch and sucrose metabolism.

Spots W1 (probable mitochondrial aconitate hydratase), W3 (probable α-subunit E1 of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex), W10 (probable pyruvate kinase), W14 (probable citrate synthase), and W17 (probable malate dehydrogenase precursor) are underrepresented in the AS-P-78 strain. These proteins belong to the glycolysis or tricarboxylic acid cycle. In addition, spot W4, which contains a probable sorbitol dehydrogenase catalyzing the oxidation of sorbitol to fructose, is also underrepresented in the AS-P-78 strain (6.26 times). This large decrease in protein W4 in the AS-P-78 strain may be compensated in part by three isoforms of a different probable sorbitol utilization protein, Sou2 (spots A1, A8, and A17). Spot A45 is 2.6-fold overrepresented in the AS-P-78 strain. It contains a protein encoded by an acetate-inducible gene (aciA), which shows strong similarity to an NAD-dependent formate dehydrogenase, AciA/Fdh, from Neosartorya fischeri (90% homology and 84% identity). It catalyzes the oxidation of formate to bicarbonate, forming NADH (required for penicillin biosynthesis). Formate may serve as an auxiliary energy substrate for yeasts and fungi: it has been reported that mixed substrate feeding (glucose/formate) can be used to increase the yield of β-lactams (49); therefore, this enzyme might help to increase the penicillin levels in this high producer strain. Spot W21 contains a probable transaldolase only present in the Wis 54-1255 strain. This protein is involved in the non-oxidative steps of the pentose phosphate pathway, connecting it to glycolysis. The lack of this protein in the AS-P-78 strain supports an important implication of the pentose phosphate pathway in penicillin production: an increased flux through the pentose pathway and decreased glycolysis correlate with strain improvement.

Penicillin Precursors

Spot A6 (1.85-fold overrepresented in the high producer strain) includes a hypothetical cystathionine β-synthase that is involved in the biosynthesis of cystathionine, a precursor of the cysteine in the ACV tripeptide (50). In this strain, a probable branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase, Bat2p (spot A3), is 4.07-fold overrepresented. This protein participates in the metabolism of valine, leucine, and isoleucine and has been reported to be essential in S. cerevisiae for fusel alcohol production; this aminotransferase may provide additional valine for penicillin biosynthesis (51). A probable alcohol dehydrogenase, AlkJ (Pc22g10020), which converts aliphatic medium-chain-length alcohols into aldehydes, is 4.53-fold underrepresented in AS-P-78 (spot W6).

Two proteins, a probable thiamin-phosphate pyrophosphorylase/hydroxyethylthiazole kinase (spot A7) and a protein with weak similarity to a hypothetical intracellular protease/amidase-related enzyme of the ThiJ family CAC2826 (spots A18 and A19), were only detected in the AS-P-78 strain. These proteins are involved in the de novo synthesis of thiamin pyrophosphate (52, 53) that works as a cofactor of aminotransferases. This cofactor is involved in branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis, regulating acetolactate synthase, the rate-limiting enzyme in this pathway. Therefore, increasing thiamin pyrophosphate levels would favor valine accumulation. Several enzymes involved in metabolism of unusual sulfur compounds and in valine catabolism have less representation in the AS-P-78 strain, suggesting that they are unfavorable for penicillin biosynthesis. Spot W7 includes a probable dihydroxy-acid dehydratase, Ilv3 (Pc22g22710), which is involved in the biosynthesis of branched-chain amino acids, that is 3.54-fold overrepresented in the Wis 54-1255 strain.

In the AS-P-78 strain, spot W42 is 8.71-fold underrepresented as compared with Wis 54-1255. It contains a protein with strong similarity to the phytanoyl-CoA dioxygenase family protein from A. fumigatus (84% homology and 74% identity). This is a peroxisomal enzyme catalyzing the first step of phytanic acid α-oxidation involved in lipid and branched-chain fatty acid degradation. Its decreased level in AS-P-78 may save fatty acid precursors for penicillin biosynthesis.

The overrepresentation of spots A47, A48, and A49 in the AS-P-78 strain is also interesting. The A47 protein has strong similarity to the dienelactone hydrolase family protein from A. fumigatus (84% homology and 73% identity) that is involved in chlorocatechol degradation via the modified ortho cleavage pathway (54). Spots A48 and A49 include the same protein (Pc22g24530), which shares a high similarity to the dienelactone hydrolase family protein of A. fumigatus (84% homology and 75% identity). The high representation of putative dienelactone hydrolases proves the ability of the high producer strain to degrade catechol and related compounds as an additional carbon source.

Surprisingly, the AS-P-78 strain does not show a significant overrepresentation of the proteins directly involved in the penicillin pathway when compared with the Wis 54-1255 despite the fact that AS-P-78 contains five or six copies of the amplified region that includes the penicillin-coding genes (10, 13). To test whether the expression of the pcbC and penDE genes (coding IPN synthase and acyl-coenzyme A:isopenicillin N acyltransferase, respectively) was different in the Wis 54-1255 and AS-P-78 strains, RT-PCR experiments were conducted using RNA extracted from cultures of these strains at 40 and 60 h. As observed in Fig. 7, the AS-P-78 strain showed in the medium used for the proteomics studies up to 1.7- and 1.3-fold increases in the steady-state levels of the pcbC and penDE transcripts, respectively. This slight transcriptional increase was not translated in a proportional increase of either the IPN synthase or the acyl-coenzyme A:isopenicillin N acyltransferase in the AS-P-78 strain (see “Discussion”).

Fig. 7.

Transcriptional analysis of pcbC and penDE genes in Wis 54-1255 and AS-P-78 strains. A, electrophoresis of the RT-PCR products using RNA extracted at 40 and 60 h from cultures of the Wis 54-1255 strain (W) and the AS-P-78 strain (A) grown under the same conditions. The transcript of β-actin was used as control. The absence of contaminant DNA in the samples was tested by PCR (data not shown). B, the bands obtained after the electrophoresis were quantified by densitometry, and their intensity was normalized to that provided by the β-actin band (relative integral optical density (IOD)). The intensity values of the pcbC and penDE transcripts obtained from the Wis 54-1255 strain at 40 h were set to 100%.

Other Secondary Metabolites

In the AS-P-78 strain, spot A4 (2.70-fold overrepresented) corresponds to a probable enoyl reductase of the lovastatin pathway (Pc20g05830) that is involved in the biosynthesis of the lovastatin precursor dihydromonacolin N (see “Discussion”).

Spot W22 is present in the Wis 54-1255 but absent in the AS-P-78 strain. It is a protein with weak similarity to an isoflavone reductase, a key enzyme of the medicarpin biosynthetic pathway (55). Probably strain AS-P-78 has lost the ability to synthesize a flavonoid molecule of this type.

It is also interesting to note that only the AS-P-78 strain shows spot A28, which includes a probable aflatoxin B aldehyde reductase (Pc20g05270). This is the major enzyme providing protection against aflatoxin B1 (see “Discussion”).

Virulence and Defense Mechanisms

The Wis 54-1255 strain shows overrepresentation as compared with AS-P-78 of three isoforms (spots W24, W25, and W26) of a protein similar to a UDP-galactopyranose mutase from A. fumigatus (96% homology and 90% identity) that is in charge of galactofuranose biosynthesis. This compound plays a crucial role in cell surface formation and the infectious cycle (56, 57).

A probable glucose oxidase (spot W5), involved in oxidation of d-glucose into d-glucono-1,5-lactone (further hydrolyzed to gluconic acid), is also overrepresented in the Wis 54-1255 strain as compared with AS-P-78. Gluconic acid and glucose oxidase have been associated with the pathogenicity of P. expansum in apples (46).

Spot W27 is 4.64-fold overrepresented in the Wis 54-1255 strain and contains a 1,4-butanediol diacrylate esterase, BDA1 (Pc15g00720), that might act as a β-lactamase (see “Discussion”). In general, these enzymes involved in fungal attack to host plants decrease during the penicillin strain improvement program.

Oxidative Stress

The most striking finding in the AS-P-78 strain consists of the overexpression of several proteins involved in oxidative stress response. These proteins are: two probable glutathione S-transferase-like proteins (eight isoforms of Pc18g00790 and one isoform of Pc12g14390; spots A30–A37 and A20), two isoforms of a probable glutathione reductase (spots A25 and A26), two probable catalases R (spots A21 and A24), a probable quinone oxidoreductase (spot A23), a probable 1,4-benzoquinone reductase (spot A22), a protein with weak similarity to 2-hydroxyisoflavone reductase (spot A29), and a probable alcohol dehydrogenase, AdhIII, which is an oxidoreductase induced by periods of anaerobic stress (58).

Protein Targeting and Processing

In the Wis 54-1255 strain, probable cyclophilins CypA (spot W28) and CypB (spot W29) are overrepresented as well as probable Hsp60 (spot W32) and chaperone BipA (spot W33). In contrast, the AS-P-78 strain contains a highly represented probable carboxypeptidase S1 (spot A38).

Cell Wall Biosynthesis and/or Integrity

In the AS-P-78 strain, several proteins involved in cell wall biosynthesis and/or integrity are overrepresented (spots A40 and A41). In addition, spot A46 is only present in the high producer strain. This spot contains a protein with strong similarity to a hypothetical protein (contig_1_84_scaffold_5.tfa_850cg) from Aspergillus nidulans that shares similarity to a dolichol-phosphate mannosyltransferase from Aspergillus terreus (72% homology and 57% identity) that is involved in N-glycan biosynthesis.

In the high producer strain, spot A5 is 4.45-fold overrepresented. It includes a lysophospholipase (phospholipase B), which hydrolyzes both the acyl ester bonds of diacylphospholipids (diacyl hydrolase) and the acyl ester bond of monoacylphospholipids or lysophospholipids. The estimated mass of this protein (111 kDa) is larger than the theoretical mass (68.69 kDa), indicating post-translational modifications events. It has been reported that the purified phospholipase B from P. notatum is a glycoprotein with a molecular weight determined by gel filtration to be about 116,000 (59). This enzyme showed a carbohydrate content of ∼30%, explaining the difference between the expected and predicted masses.

DISCUSSION

One of the major efforts to modify microorganisms of biotechnological interest has been provided by the antibiotics industry. P. chrysogenum has been extensively mutated during the last decades to increase the penicillin titers, but despite the importance of this microorganism, the biochemical bases that have been modified during the strain improvement process remain poorly understood.

In this study, we performed for the first time an extensive 2-DE proteome reference mapping of the penicillin producer P. chrysogenum with a high resolution and reproducibility together with a detailed study by PMF and tandem mass spectrometry analyses of the protein changes produced during the industrial strain improvement program. We were able to identify a large number of proteins (950 representing 549 different proteins), which have been classified according to their function with a distribution similar to that reported for the ascomycete S. pombe (18). Because P. chrysogenum is important for the production of secondary metabolites, especially penicillins, we focused on the proteins related to the biosynthesis of these compounds. As indicated under “Results,” we identified the last two proteins involved in the penicillin pathway (IPN synthase and acyl-coenzyme A:isopenicillin N acyltransferase) but not the ACV synthetase due to its large molecular mass (425 kDa). Only the β-subunit of the acyl-coenzyme A:isopenicillin N acyltransferase was detected. The acyl-coenzyme A:isopenicillin N acyltransferase is a peroxisomal enzyme synthesized as an inactive 40-kDa preprotein that undergoes self-processing between residues Gly-102 and Cys-103, giving rise to an active heterodimer with subunits α (11 kDa; corresponding to the N-terminal fragment) and β (29 kDa; corresponding to the C-terminal region) (32, 60, 61). Although the 11-kDa α-subunit has not been identified in the reference map, Kiel et al. (24) found both subunits (the α-subunit in small amounts) during the analysis of P. chrysogenum peroxisomal proteins by nano-LC-MS/MS. It is likely that the 11-kDa α-subunit is further processed, hampering its identification by PMF.

The optimization of the 2-DE analysis for P. chrysogenum allowed us to perform a detailed comparative analysis of the wild-type strain NRRL 1951, the low producer Wis 54-1255, and the high producer AS-P-78. In the wild-type strain, those proteins involved in virulence and plant cell wall degradation for the obtention of nutrients are predominant (the wild-type strain isolated from a cantaloupe is able to infect and grow on fruits) (4). One of the reasons for the very low amount of penicillin produced by the wild-type strain might be the use of precursors and energy for the biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites, such as terpenoids (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase), porphyrins (coproporphyrinogen oxidase), or pigments like violaxanthin (zeaxanthin epoxidase) and melanin (scytalone dehydratase), which could divert the metabolic fluxes away from the penicillin biosynthetic pathway. It is known that during the mutagenic treatments (from the Q-176 strain to the BL3-D10 strain) pigmentless strains without the chrysogenin yellow pigment were selected (2).

Proteins involved in biosynthesis or degradation of precursor amino acids are distinctly represented in the three strains. In the wild-type NRRL 1951 strain, the increased levels of the methylmalonate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase might be one reason for the low penicillin biosynthesis in this strain. This enzyme is involved in the “distal pathway” of valine catabolism (43, 44), leading to valine pool depletion. Cysteine biosynthesis seems to be one of the major improvements that occurred during the selection process. Penicillin production flux is greatly influenced by cysteine availability for ACV formation (62). Cysteine synthase (forming cysteine from serine) is overrepresented in the Wis 54-1255 compared with the wild-type strain. This improvement is conserved in the AS-P-78 strain, which in addition showed an increased content of the cystathionine β-synthase, an enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of cysteine from methionine by transsulfuration. This indicates that the AS-P-78 strain has improved the two cysteine biosynthetic pathways.

In the Wis 54-1255 improved producer strain, those proteins in charge of energy obtention from carbohydrates are predominant. These proteins mainly belong to the tricarboxylic acid cycle, although there are also enzymes from the glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation pathways. It is likely that during the strain improvement process those mechanisms for energy obtention were of benefit to meet the increasing demand for penicillin biosynthesis.

An interesting finding is that the Wis 54-1255 strain overproduces, as compared with the AS-P-78 strain, one protein that may be related to penicillin modification or degradation. This enzyme is similar to a 1,4-butanediol diacrylate esterase, BDA1 (converting 1,4-butanediol diacrylate to 4-hydroxybutyl acrylate), which contains a domain conserved in class C β-lactamase and other penicillin-binding proteins. It shows similarity to a putative transesterase (LovD) from Aspergillus clavatus (85% homology and 72% identity) and to a β-lactamase from Paracoccidioides brasiliensis (48% homology and 32% identity). Transesterase LovD adds 2-methylbutyrate to monacolin J to form lovastatin. Therefore, this LovD-like protein may bind the nucleus of penicillin, contributing to its modification or degradation. The reduction of this protein in the AS-P-78 as compared with the wild-type and Wis 54-1255 strains might be one of the mechanisms that contributed to increase the penicillin titers in this industrial strain.

It is known that during the generation of the penicillin high producer strain AS-P-78 amplification of the penicillin biosynthetic gene cluster (pcbAB-pcbC-penDE) occurred (10). However, this amplification has not led to correlative protein synthesis even though there was a slight increase in transcription. This is in agreement with previous results obtained for the pcbC gene (63). In fact, it has been reported that there is no linear relationship between the increasing number of penicillin gene clusters and the penicillin titer (12). These results indicate that although gene amplification has an impact on penicillin production it is not the main mechanism that transformed the Wis 54-1255 strain into a penicillin overproducer.

Another modification that might have provided the basis for the increased penicillin titers of the AS-P-78 strain is the overproduction of enzymes of the pentose phosphate pathway. Enzymes from the non-oxidative phase of this pathway, like ribose-5-phosphate isomerase or transketolase, are predominant in the high producer strain. In addition, some enzymes involved in de novo synthesis of thiamin pyrophosphate were overrepresented. Thiamin pyrophosphate is a prosthetic group present in many enzymes. One of these enzymes is the transketolase (64), which connects the pentose phosphate pathway to glycolysis, feeding excess sugar phosphates into the main carbohydrate metabolic pathways. It is likely that a high concentration of ribulose 5-phosphate (together with reducing power in the form of NADPH) is formed in the high producer strain through the oxidative phase of the pentose phosphate pathway; therefore, the excess of this sugar phosphate would be converted by the ribose-5-phosphate isomerase into ribulose 5-phosphate (precursor of nucleotides and nucleic acids) and by the transketolase into precursors for glycolysis. An increase in the NADPH levels has been strongly correlated to β-lactam production (65–67). It is accepted that penicillin production in the high producer strains constitutes a major burden on the supply of NADPH (68) (biosynthesis of 1 mol of penicillin requires 8–10 mol of NADPH). In addition, it has been reported that penicillin production is greatly influenced by the ATP level and cysteine concentration. Because NADPH is required for the biosynthesis of this amino acid, there is a positive relationship between cysteine and NADPH levels and penicillin production (62). NADPH is also required to reduce the oxidized glutathione during oxidative stress that results from intense aeration rates (30). The increase in cysteine biosynthesis in the high penicillin producer strain may be related to an increased demand for glutathione biosynthesis to cope with increased oxidative stress. Our results have established that several proteins involved in the response to oxidative stress are overrepresented in the AS-P-78 strain.

Some differences in protein expression observed in the AS-P-78 strain show good correlation with the transcriptional responses described in a P. chrysogenum strain engineered to produce adipoyl-7-amino-3-carbamoyloxymethyl-3-cephem-4-carboxylic acid; this may be related to the fact that the host P. chrysogenum strain used in that study is a penicillin overproducer strain. These responses involved transcriptional up-regulation of a putative aflatoxin B1 aldehyde reductase, two glutathione S-transferases, a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, and an NADPH:quinone oxidoreductase (69). These results point to oxidative stress responses as adaptation mechanisms to penicillin overproduction.

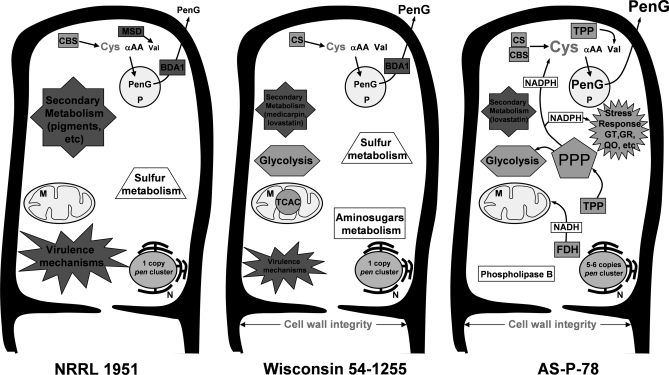

A global view of the proteins differentially expressed in these three strains revealed that the representativeness of some pathways and functions have been magnified during the improvement process, whereas others have decreased (Fig. 8). Glucose oxidase is a diminished protein in the wild-type strain as compared with the AS-P-78 strain. The underrepresentation of this enzyme associated with plant pathogenicity is not surprising because submerged liquid cultures have replaced the natural growth on fruits.

Fig. 8.

Schematic representation of some pathways and networks modified during strain improvement program according to results obtained after proteome comparison of NRRL 1951, Wis 54-1255, and AS-P-78 strains. Font size is in concordance with the protein amount observed by CC staining strength in the comparative proteome analyses. αAA, α-aminoadipic acid; BDA1, 1,4-butanediol diacrylate esterase (putative β-lactamase); CBS, cystathionine β-synthase; CS, cysteine synthase; FDH, formate dehydrogenase; GR, glutathione reductase; GT, glutathione S-transferase; M, mitochondrion; MSD, methylmalonate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase; N, nucleus; P, peroxisome; PenG, benzylpenicillin; PPP, pentose phosphate pathway; QO, quinone oxidoreductase; TCAC, tricarboxylic acid cycle; TPP, thiamin pyrophosphate.

Probably the most striking loss of some pathways that occurred during the selection of these strains is the reduction of many secondary metabolism routes to potentiate the biosynthesis of β-lactams. Pigments constitute one of the best examples of secondary metabolites lost during the manipulation of the wild-type strain to obtain the Wis 54-1255 strain. During the selection of the high producer strain AS-P-78, other pathways for secondary metabolism seemed to be blocked as suggested by the absence in AS-P-78 of a putative isoflavone reductase (involved in the latter part of the medicarpin biosynthetic pathway).

On the other hand, there are proteins involved in pathways or functions that have increased during the strain improvement program. It is intriguing that one of the proteins (enoyl reductase LovC; Pc20g05830) involved in the biosynthesis of the lovastatin precursor dihydromonacolin N is overrepresented in the Wis 54-1255 strain compared with the wild-type strain and also in the AS-P-78 strain compared with the Wis 54-1255 strain. Up-regulation of the gene encoding the enoyl reductase has also been reported as one of the transcriptional responses in adipoyl-7-amino-3-carbamoyloxymethyl-3-cephem-4-carboxylic acid production in P. chrysogenum (69). It remains to be established whether this protein is truly involved in lovastatin biosynthesis or whether it is a LovC-like protein indirectly related to penicillin biosynthesis. Although other lovastatin-related genes occur in the genome of P. chrysogenum, they are not clustered together, making them unlikely to serve for lovastatin biosynthesis.

In conclusion, we have shown that the increase in penicillin production along the industrial strain improvement program is a consequence of metabolic reorganizations. The proteomics and transcriptomics of β-lactam biosynthesis is an excellent model for the study of thousands of other poorly known fungal secondary metabolites. The results provided by this work suggest that energetic burden, redox metabolism, and the supply of precursors are crucial for the biosynthesis of penicillin, a metabolic model that might be applied to any other secondary metabolite. Although proteome analysis of the cytosolic fraction has allowed us to decipher some of the protein expression differences leading to the production of high penicillin titers, many other processes still remain to be figured out, like the role of membrane-associated transporters in the fluxes of penicillin, penicillin precursors, or intermediaries (16).

Acknowledgments

The expert help of Abel A. Cuadrado (University of Oviedo, Oviedo, Spain) with the informatics tools and the critical review of the manuscript by E. Calvo (Fundacion Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares Carlos III (CNIC), Madrid, Spain) are acknowledged. We also thank B. Martín, J. Merino, A. Casenave, and A. Mulero (INBIOTEC) for excellent technical assistance.

* This work was supported in part by grants from the European Union (Eurofung Grant QLRT-1999-00729 and Eurofungbase), the Agencia de Inversiones y Servicios de Castilla y León (Proyecto Genérico de Desarrollo Tecnológico 2008), and the Ministry of Industry of Spain (PROFIT Grant FIT-010000-2007-74).

This article contains supplemental Fig. 1, Tables 1–6, and Data 1.

This article contains supplemental Fig. 1, Tables 1–6, and Data 1.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- Wis

- Wisconsin

- 2-DE

- two-dimensional gel electrophoresis

- CC

- colloidal Coomassie

- IPN

- isopenicillin N

- NL

- non-linear

- PMF

- peptide mass fingerprinting

- ddH2O

- double distilled H2O

- ACV

- α-aminoadipyl-cysteinyl-valine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Liras P., Martín J. F. (2009) β-Lactam antibiotics, in Encyclopedia of Microbiology (Schaechter M. ed) 3rd Ed., pp. 274–289, Elsevier Ltd., Oxford [Google Scholar]

- 2.García-Rico R. O., Fierro F., Mauriz E., Gómez A., Fernández-Bodega M. A., Martín J. F. (2008) The heterotrimeric Gα protein Pga1 regulates biosynthesis of penicillin, chrysogenin and roquefortine in Penicillium chrysogenum. Microbiology 154, 3567–3578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleming A. (1929) On the antibacterial action of cultures of a penicillium with special reference to their use in the isolation of B. influenza. Br. J. Exp. Pathol 10, 226–236 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raper K. B., Alexander D. F., Coghill R. D. (1944) Penicillin. II. Natural variation and penicillin production in Penicillium notatum and allied species. J. Bacteriol 48, 639–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elander R. P. (1983) Strain improvement and preservation of beta-lactam producing microorganisms, in Antibiotics Containing the Beta-lactam Structure I (Demain A. L., Solomon N. eds) pp. 97–146, Springer-Verlag, New York [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elander R. P. (2002) University of Wisconsin contributions to the early development of penicillin and cephalosporin antibiotics. SIM News 52, 270–278 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demain A. L., Elander R. P. (1999) The β-lactam antibiotics: past, present and future. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 75, 5–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lein J. (1986) The Panlabs Penicillium strain improvement program, in Overproduction of Microbial Metabolites (Vanek Z., Hostalek Z. eds) pp. 105–140, Butterworths, Stoneham, MA [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gouka R. J., van Hartingsveldt W., Bovenberg R. A., van den Hondel C. A., van Gorcom R. F. (1991) Cloning of a nitrate-nitrite reductase gene cluster of Penicillium chrysogenum and use of the niaD gene as a homologous marker. J. Biotechnol 20, 189–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fierro F., Barredo J. L., Díez B., Gutierrez S., Fernández F. J., Martín J. F. (1995) The penicillin gene cluster is amplified in tandem repeats linked by conserved hexanucleotide sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 92, 6200–6204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodríguez-Sáiz M., Barredo J. L., Moreno M. A., Fernández-Cañón J. M., Peñalva M. A., Díez B. (2001) Reduced function of a phenylacetate-oxidizing cytochrome P450 caused strong genetic improvement in early phylogeny of penicillin-producing strains. J. Bacteriol 183, 5465–5471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newbert R. W., Barton B., Greaves P., Harper J., Turner G. (1997) Analysis of a commercially improved Penicillium chrysogenum strain series: involvement of recombinogenic regions in amplification and deletion of the penicillin biosynthesis gene cluster. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol 19, 18–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fierro F., García-Estrada C., Castillo N. I., Rodríguez R., Velasco-Conde T., Martín J. F. (2006) Transcriptional and bioinformatic analysis of the 56.8 kb DNA region amplified in tandem repeats containing the penicillin gene cluster in Penicillium chrysogenum. Fungal Genet. Biol 43, 618–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Müller W. H., van der Krift T. P., Krouwer A. J., Wösten H. A., van der Voort L. H., Smaal E. B., Verkleij A. J. (1991) Localization of the pathway of the penicillin biosynthesis in Penicillium chrysogenum. EMBO J 10, 489–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamas-Maceiras M., Vaca I., Rodríguez E., Casqueiro J., Martín J. F. (2006) Amplification and disruption of the phenylacetyl-CoA ligase gene of Penicillium chrysogenum encoding an aryl-capping enzyme that supplies phenylacetic acid to the isopenicillin N-acyltransferase. Biochem. J 395, 147–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martín J. F., Ullán R. V., García-Estrada C. (2010) Regulation and compartmentalization of β-lactam biosynthesis. Microb. Biotechnol, 3, 285–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van den Berg M. A., Albang R., Albermann K., Badger J. H., Daran J. M., Driessen A. J., Garcia-Estrada C., Fedorova N. D., Harris D. M., Heijne W. H., Joardar V., Kiel J. A., Kovalchuk A., Martín J. F., Nierman W. C., Nijland J. G., Pronk J. T., Roubos J. A., van der Klei I. J., van Peij N. N., Veenhuis M., von Döhren H., Wagner C., Wortman J., Bovenberg R. A. (2008) Genome sequencing and analysis of the filamentous fungus Penicillium chrysogenum. Nat. Biotechnol 26, 1161–1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hwang K. H., Carapito C., Böhmer S., Leize E., Van Dorsselaer A., Bernhardt R. (2006) Proteome analysis of Schizosaccharomyces pombe by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Proteomics 6, 4115–4129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melin P., Schnürer J., Wagner E. G. (2002) Proteome analysis of Aspergillus nidulans reveals proteins associated with the response to the antibiotic concanamycin A, produced by Streptomyces species. Mol. Genet. Genomics 267, 695–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kniemeyer O., Lessing F., Scheibner O., Hertweck C., Brakhage A. A. (2006) Optimisation of a 2-D gel electrophoresis protocol for the human pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Curr. Genet 49, 178–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vödisch M., Albrecht D., Lessing F, Schmidt A. D., Winkler R., Guthke R., Brakhage A. A., Kniemeyer O. (2009) Two-dimensional proteome reference maps for the human pathogenic filamentous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Proteomics 9, 1407–1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shevchenko A., Jensen O. N., Podtelejnikov A. V., Sagliocco F., Wilm M., Vorm O., Mortensen P., Shevchenko A., Boucherie H., Mann M. (1996) Linking genome and proteome by mass spectrometry: large-scale identification of yeast proteins from two dimensional gels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 93, 14440–14445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruckmann A., Hensbergen P. J., Balog C. I., Deelder A. M., Brandt R., Snoek I. S., Steensma H. Y., van Heusden G. P. (2009) Proteome analysis of aerobically and anaerobically grown Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells. J. Proteomics 71, 662–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiel J. A., van den Berg M. A., Fusetti F., Poolman B., Bovenberg R. A., Veenhuis M., van der Klei I. J. (2009) Matching the proteome to the genome: the microbody of penicillin-producing Penicillium chrysogenum cells. Funct. Integr. Genomics 9, 167–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Casqueiro J., Bañuelos O., Gutiérrez S., Hijarrubia M. J., Martín J. F. (1999) Intrachromosomal recombination between direct repeats in Penicillium chrysogenum: gene conversion and deletion events. Mol. Gen. Genet 261, 994–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kosalková K., García-Estrada C., Ullán R. V., Godio R. P., Feltrer R., Teijeira F., Mauriz E., Martín J. F. (2009) The global regulator LaeA controls penicillin biosynthesis, pigmentation and sporulation, but not roquefortine C synthesis in Penicillium chrysogenum. Biochimie 91, 214–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernández-Acero F. J., Jorge I., Calvo E., Vallejo I., Carbú M., Camafeita E., López J. A., Cantoral J. M., Jorrín J. (2006) Two-dimensional electrophoresis protein profile of the phytopathogenic fungus Botrytis cinerea. Proteomics 6, S88–S96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Candiano G., Bruschi M., Musante L., Santucci L., Ghiggeri G. M., Carnemolla B., Orecchia P., Zardi L., Righetti P. G. (2004) Blue silver: a very sensitive colloidal Coomassie G-250 staining for proteome analysis. Electrophoresis 25, 1327–1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Havlis J., Thomas H., Sebela M., Shevchenko A. (2003) Fast-response proteomics by accelerated in-gel digestion of proteins. Anal. Chem 75, 1300–1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Díez B., Schleissner C., Moreno M. A., Rodríguez M., Collados A., Barredo J. L. (1998) The manganese superoxide dismutase from the penicillin producer Penicillium chrysogenum. Curr. Genet 33, 387–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruepp A., Zollner A., Maier D., Albermann K., Hani J., Mokrejs M., Tetko I., Güldener U., Mannhaupt G., Münsterkötter M., Mewes H. W. (2004) The FunCat, a functional annotation scheme for systematic classification of proteins from whole genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 32, 5539–5545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.García-Estrada C., Vaca I., Fierro F., Sjollema K., Veenhuis M., Martín J. F. (2008) The unprocessed preprotein form IATC103S of the isopenicillin N acyltransferase is transported inside peroxisomes and regulates its self-processing. Fungal Genet. Biol 45, 1043–1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kovacevic S., Tobin M. B., Miller J. R. (1990) The beta-lactam biosynthesis genes for isopenicillin N epimerase and deacetoxycephalosporin C synthetase are expressed from a single transcript in Streptomyces clavuligerus. J. Bacteriol 172, 3952–3958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coque J. J., Enguita F. J., Martín J. F., Liras P. (1995) A two-protein component 7 alpha-cephem-methoxylase encoded by two genes of the cephamycin C cluster converts cephalosporin C to 7-methoxycephalosporin C. J. Bacteriol 177, 2230–2235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kennedy J., Auclair K., Kendrew S. G., Park C., Vederas J. C., Hutchinson C. R. (1999) Modulation of polyketide synthase activity by accessory proteins during lovastatin biosynthesis. Science 284, 1368–1372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parsons J. F., Calabrese K., Eisenstein E., Ladner J. E. (2004) Structure of the phenazine biosynthesis enzyme PhzG. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 60, 2110–2113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ehrlich K. C., Yu J., Cotty P. J. (2005) Aflatoxin biosynthesis gene clusters and flanking regions. J. Appl. Microbiol 99, 518–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keller N. P., Kantz N. J., Adams T. H. (1994) Aspergillus nidulans verA is required for production of the mycotoxin sterigmatocystin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 60, 1444–1450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keller N. P., Segner S., Bhatnagar D., Adams T. H. (1995) stcS, a putative P-450 monooxygenase, is required for the conversion of versicolorin A to sterigmatocystin in Aspergillus nidulans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 61, 3628–3632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dixon R. A., Steele C. L. (1999) Flavonoids and isoflavonoids—a gold mine for metabolic engineering. Trends Plant Sci 4, 394–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kawaguchi T., Enoki T., Tsurumaki S., Sumitani J., Ueda M., Ooi T., Arai M. (1996) Cloning and sequencing of the cDNA encoding beta-glucosidase 1 from Aspergillus aculeatus. Gene 173, 287–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Costenoble R., Valadi H., Gustafsson L., Niklasson C., Franzén C. J. (2000) Microaerobic glycerol formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 16, 1483–1495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goodwin G. W., Rougraff P. M., Davis E. J., Harris R. A. (1989) Purification and characterization of methylmalonate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase from rat liver. Identity to malonate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem 264, 14965–14971 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Y. X., Tang L., Hutchinson C. R. (1996) Cloning and characterization of a gene (msdA) encoding methylmalonic acid semialdehyde dehydrogenase from Streptomyces coelicolor. J. Bacteriol 178, 490–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gómez B. L., Nosanchuk J. D. (2003) Melanin and fungi. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis 16, 91–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hadas Y., Goldberg I., Pines O., Prusky D. (2007) Involvement of gluconic acid and glucose oxidase in the pathogenicity of Penicillium expansum in apples. Phytopathology 97, 384–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hwang C. S., Flaishman M. A., Kolattukudy P. E. (1995) Cloning of a gene expressed during appressorium formation by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and a marked decrease in virulence by disruption of this gene. Plant Cell 7, 183–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beauvais A., Monod M., Debeaupuis J. P., Diaquin M., Kobayashi H., Latgé J. P. (1997) Biochemical and antigenic characterization of a new dipeptidyl-peptidase isolated from Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Biol. Chem 272, 6238–6244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harris D. M., van der Krogt Z. A., van Gulik W. M., van Dijken J. P., Pronk J. T. (2007) Formate as an auxiliary substrate for glucose-limited cultivation of Penicillium chrysogenum: impact on penicillin G production and biomass yield. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 73, 5020–5025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kosalková K., Marcos A. T., Martín J. F. (2001) A moderate amplification of the mecB gene encoding cystathionine-γ-lyase stimulates cephalosporin biosynthesis in Acremonium chrysogenum. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol 27, 252–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schoondermark-Stolk S. A., Tabernero M., Chapman J., Ter Schure E. G., Verrips C. T., Verkleij A. J., Boonstra J. (2005) Bat2p is essential in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for fusel alcohol production on the non-fermentable carbon source ethanol. FEMS Yeast Res 5, 757–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nosaka K., Nishimura H., Kawasaki Y., Tsujihara T., Iwashima A. (1994) Isolation and characterization of the THI6 gene encoding a bifunctional thiamin-phosphate pyrophosphorylase/hydroxyethylthiazole kinase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem 269, 30510–30516 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mizote T., Tsuda M., Smith D. D., Nakayama H., Nakazawa T. (1999) Cloning and characterization of the thiD/J gene of Escherichia coli encoding a thiamin-synthesizing bifunctional enzyme, hydroxymethylpyrimidine kinase/phosphomethylpyrimidine kinase. Microbiology 145, 495–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moiseeva O. V., Solyanikova I. P., Kaschabek S. R., Gröning J., Thiel M., Golovleva L. A., Schlömann M. (2002) A new modified ortho cleavage pathway of 3-chlorocatechol degradation by Rhodococcus opacus 1CP: genetic and biochemical evidence. J. Bacteriol 184, 5282–5292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dixon R. A. (2001) Natural products and disease resistance. Nature 411, 843–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bakker H., Kleczka B., Gerardy-Schahn R., Routier F. H. (2005) Identification and partial characterization of two eukaryotic UDP-galactopyranose mutases. Biol. Chem 386, 657–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beverley S. M., Owens K. L., Showalter M., Griffith C. L., Doering T. L., Jones V. C., McNeil M. R. (2005) Eukaryotic UDP-galactopyranose mutase (GLF gene) in microbial and metazoal pathogens. Eukaryot. Cell 4, 1147–1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kelly J. M., Drysdale M. R., Sealy-Lewis H. M., Jones I. G., Lockington R. A. (1990) Alcohol dehydrogenase III in Aspergillus nidulans is anaerobically induced and post-transcriptionally regulated. Mol. Gen. Genet 222, 323–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kawasaki N., Sugatani J., Saito K. (1975) Studies on a phospholipase B from Penicillium notatum. Purification, properties, and mode of action. J. Biochem 77, 1233–1244 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Whiteman P. A., Abraham E. P., Baldwin J. E., Fleming M. D., Schofield C. J., Sutherland J. D., Willis A. C. (1990) Acyl coenzyme A: 6-aminopenicillanic acid acyltransferase from Penicillium chrysogenum and Aspergillus nidulans. FEBS Lett 262, 342–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tobin M. B., Baldwin J. E., Cole S. C., Miller J. R., Skatrud P. L., Sutherland J. D. (1993) The requirement for subunit interaction in the production of Penicillium chrysogenum acyl-coenzyme A: isopenicillin N acyltransferase in Escherichia coli. Gene 132, 199–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nasution U., van Gulik W. M., Ras C., Proell A., Heijnen J. J. (2008) A metabolome study of the steady-state relation between central metabolism, amino acid biosynthesis and penicillin production in Penicillium chrysogenum. Metab. Eng 10, 10–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]