Abstract

Background

Bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) is frequent and reported to cause numerous complications but clinical outcome of patients diagnosed with normal or mildly dysfunctional valve is undefined.

Methods and Results

In 212 (32±20 years, 65 percent male) asymptomatic community residents from Olmsted County, MN, BAV was diagnosed between 1980-99 with ejection fraction ≥50% and aortic regurgitation or stenosis absent or mild. Aortic valve degeneration at diagnosis was scored echocardiographically for calcification, thickening and mobility reduction (0 to 3 each) with range from 0 to 9.

At diagnosis, ejection fraction was 63±5% and left ventricular diameter 48±9 mm. Survival 20 years after diagnosis was 90±3%, identical to the general population (p=0.72). Twenty years after diagnosis heart failure, new cardiac symptoms and cardiovascular medical events occurred in 7±2, 26±4 and 33±5%, respectively. Aortic valve surgery, ascending aortic surgery or any cardiovascular surgery were required (20-years) in 24±4, 5±2 and 27±4% at younger age than the general population (p<0.0001). No aortic dissection occurred. Thus, cardiovascular medical or surgical events occurred in 42±5% 20 years after diagnosis. Independent predictors of cardiovascular events were age≥50 (risk-ratio 3.0[1.5-5.7] p<0.01) and valve degeneration at diagnosis (risk-ratio 2.4[1.2-4.5] p=0.016, >70% events at 20 years). Baseline ascending aorta ≥40 mm independently predicted surgery for aorta dilatation (risk-ratio 10.8[1.8-77.3], p<0.01).

Conclusions

In the community, asymptomatic patients with bicuspid aortic valve and no or minimal hemodynamic abnormality, enjoy excellent long-term survival but incur frequent cardiovascular events, particularly with progressive valve dysfunction. Echocardiographic valve degeneration at diagnosis separates higher-risk patients who require regular assessment from lower-risk patients who only require episodic follow-up.

Keywords: aorta, echocardiography, surgery, survival, valves

Introduction

Bicuspid Aortic valve (BAV) is a common congenital heart abnormality, affecting 0.5 to 2 percent of the population.1-3 It is often considered a serious condition, with notable valvular risk, particularly of aortic valve endocarditis,4,5 of frequent progression to aortic valve stenosis,6,7 especially in men,7 and of frequent aortic regurgitation requiring aortic valve replacement(AVR).8,9 Furthermore, BAV is not just a peculiar valve morphology but is a disease of the ascending aorta, characterized at an early stage by asymptomatic dilatation of the ascending aorta10 and later by frequent susceptibility to aneurysm formation of the aorta 11-13 and to the most dreaded complication, aortic dissection.2,9,14 However, these implied serious prognostic consequences of BAV were derived mostly from autopsy or referral centers’ studies with high concentration of patients already with these complications. There is little longitudinal data on asymptomatic, initially uncomplicated patients detected in the community who are not referred and may never be accounted for until autopsy.1 Thus, the real complication burden of BAV in the community has not been measured. While it is well established that patients with clinically significant aortic valve stenosis or regurgitation incur serious outcome consequences whether they have bicuspid and tricuspid valves,15,16 limited data is available regarding patients with initially normally functioning or minimally dysfunctional BAV,17,18 in whom mortality, cardiac and vascular event rates are undefined. To resolve these uncertainties, assessment of all cases diagnosed in a geographically defined community with high utilization of echocardiography and very long-term outcome assessment is essential in verifying the working hypothesis that BAV, even normally functioning or minimally dysfunctional, is associated with mortality in excess to that of the general population. We also aimed at defining cardiovascular complications rates and determinants and analyzed the Olmsted county community over 20 years to examine to define the complication rates of BAV.

Methods

Study Subjects

Eligible subjects were 1-residents of Olmsted County of all ages, MN, 2-in whom BAV was diagnosed and confirmed by echocardiography from 1980 to 1999, 3-with no cardiovascular symptoms at diagnosis, 4-with normal function or minimal dysfunction of the aortic valve, based on clinical evaluation confirmed by echocardiography showing no or at most mild stenosis (wide systolic valvular opening with mean gradient <20 mmHg in patients who underwent continuous wave Doppler) and no or mild regurgitation (no or mild left ventricular enlargement,19 no or mild regurgitation by pulsed-wave of LV outflow tract and of Aortic arch or by color flow Doppler) and 5-with left ventricular ejection fraction ≥50%. Olmsted County, MN is the geographical location of the Mayo Clinic and residents of the County represent the primary care basis of our institution, which provides all cardiovascular consultative services and all echocardiographic services to county residents. Exclusion criteria were 1-Severe comorbidity at diagnosis; 2-Complex congenital heart disease at diagnosis, 3-Prisoners of the Federal Medical center of Olmsted County, MN. The protocol was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. The study design was retrospective identification of all patients diagnosed with BAV using validated echocardiographic measurements (left ventricular size and function, aortic size, Doppler variables) measured prospectively during the diagnostic study.

Echocardiography

All patients underwent baseline clinical evaluation performed by their personal physician and comprehensive 2-dimensional and Doppler echocardiographic evaluation according to state of the art technology at diagnosis.20,21 Left ventricular ejection fraction was assessed with two-dimensional echocardiography guidance22 and visual estimation.23 Diagnosis of BAV was based on short axis imaging of aortic valve demonstrating existence of only two commissures delimiting only two aortic valve leaflets (Fig. 1). Multiple views were obtained with physician immediate review and if necessary repeat imaging to confirm the bicuspid valve. Bicuspid aortic valves were classified as typical (right-left coronary cusp fusion) if the commissures were at 4′-10′, 5′-11′ or 3′-9 o’clock (anterior-posterior cusps), and atypical (right-non coronary cusp fusion) if the commissures were at 1′-7′ or 12′-6 o’clock (right-left cusps).24-26 Presence of a raphe and systolic doming of the valve were also recorded. Doppler measured blood velocity, with pulsed- or color-Doppler or both assessing sub-aortic flow and degree of aortic regurgitation27 and with assessment of flow reversal in the aortic arch, and with continuous-wave Doppler measurement of maximal jet velocity.28 All patients diagnosed before availability of continuous wave Doppler, wide valvular opening ascertained the absence of valve stenosis. Two-dimensional ascending aorta measurements were made in patients with appropriate aortic visualization in systole at the proximal ascending aorta level.

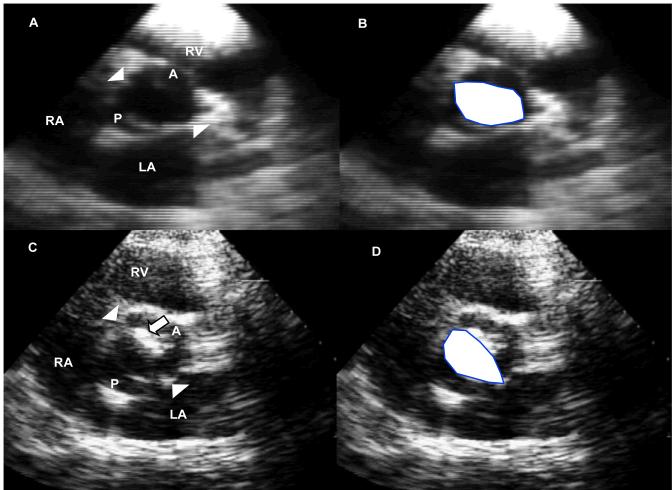

Figure 1.

Echocardiographic short-axis views in systole at aortic cusps’ levels in two patients with bicuspid aortic valves. In A is shown a patient with no valve degeneration with in B the same image superimposed with the drawing of the large valve orifice (white area). Arrowheads mark the commissures; A: Anterior cusp; P: posterior cusp; LA: Left atrium; RA: Right Atrium, RV: Right Ventricle. In C is shown a patient with valve degeneration (large arrow) involving mostly the anterior cusp with large orifice area drawn in D (white area). Labeling is similar to image A.

All baseline echocardiograms were reviewed by experienced observers blindly to identification and outcome, to evaluate valve degeneration (Fig. 1). A baseline 2-dimensional echocardiographic aortic valve degeneration score was calculated. Each component of valve degeneration was graded from 0 (normal), 1(mild alteration), 2 (moderate alteration) to 3 (severe alteration) for thickening, calcification and reduced mobility. Moderate or severe alterations were localized and did not affect the overall normal hemodynamic function of the valve. A visible raphe was not considered as a sign of valve degeneration. These three component scores were then summated into a final composite score of degeneration, which ranged potentially from 0 to 9 points. Twenty randomly chosen studies were also graded repeatedly for intra- and inter-observer agreement of the degeneration score.

Follow-up and outcomes

Clinical follow-up was obtained by review of medical records, surveys and telephone interviews. Cause of death was determined by review of medical records and death certificates. Events used as end-points were mortality and cardiovascular medical events, surgical events and total events. Medical cardiovascular events included cardiac death, congestive heart failure, new cardiovascular symptoms (dyspnea, syncope and anginal pain), stroke and endocarditis. Surgical events comprised aortic valve surgery (aortic valve replacement, repair or valvulotomy), and surgery of the thoracic aorta (due to aortic aneurysm, dissection or coarctation). Follow-up echo when available (143 patients) was analyzed for progression of aortic dilatation.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean±SD for continuous variables and percentage for categorical variables. Intra- and inter-observer agreement of degeneration score was analyzed using matched pairs for absolute differences and Pearson correlation coefficients. Survival and event rates were determined with the Kaplan-Meier method and compared between groups using the two-sample log-rank test. Association of baseline characteristics with events’ incidence was analyzed with Cox proportional-hazards method. Survival of patients was compared with that of the Minnesota white population matched for age and sex as defined by the US census bureau life tables and tested with one-sample log-rank test. As full-Doppler methods (continuous wave Doppler and color-flow imaging) were only available after 1985, we analyzed comparability of outcomes pre- and post-1985. P<0.05 was significant.

Results

Study subjects

Between 1980 and 1999, BAV was diagnosed in 5747 patients, of whom 5126 were distantly referred, and 621 were from Olmsted County of whom 373 had moderate or severe valve disease (with or without symptoms or abnormal ventricular function) and 248 had an echocardiographic diagnosis of BAV and a normal or minimally dysfunctional aortic valve. Seven were excluded because of questionable cusp number without BAV confirmation and 29 were excluded because at diagnosis they presented with severe comorbidity, complex congenital heart disease, symptoms of ongoing cardiovascular disease or ejection fraction <50% or could not be involved in research (inmates). The remaining 212 patients responding to eligibility criteria formed the final study group. Baseline characteristics of the 212 eligible patients (65% men) are presented in Table 1. Age at diagnosis was 32±20 years, 154 patients (73%) were ≥18 years at diagnosis and the oldest patient diagnosed with a normally functioning BAV valve was 89 years old. Indications for echocardiography were a systolic ejection murmur in 101 (48%), a systolic click in 32 (15%) patients, a diastolic murmur in 18 (9%) and miscellaneous in the remainder (including assessment of left ventricular function, suspected thoracic aortic disease, palpitations, atypical chest pain and non-cardiac symptoms). Associated congenital cardiac abnormalities were found in 32 (15%) patients and were mostly mild, causing no cardiac symptoms and no heart failure, with the most frequent being aortic coarctation (n=15). A typical BAV was present in 182 patients and atypical in 30 (14%). The degeneration score was low (0.80±1.4, median 0) and ranged from 0 to 6. Intra- and inter-observer correlations for degeneration score were 0.89 and 0.94, (both p<0.01) with no systematic difference (both p>0.50). There were 184 (87%) patients without valve degeneration (score <3, Fig 1A) and 28 (13%) with valve degeneration at diagnosis (score ≥3, Fig 1C) and their baseline characteristics are compared in the right part of Table 1. Valve degeneration showed the strongest association to older age and after adjusting for age, its association to hypertension became insignificant (p=0.80). However, adjusting for age did not affect the trend for association to cholesterol level (p=0.05). A raphe was visualized more frequently in patients with valve degeneration at diagnosis. A systolic click was heard more often in patients without valve degeneration. Diagnosis was made up to 1985 in 50 patients after 1985 in 162 patients. These subsets had similarly normal LV size (49±7 vs. 48±10 mm, p=0.15) similar ejection fraction (63±6 vs. 63±5%, p=0.92) and similar prevalence of valve degeneration (12 vs. 13.6%, p=0.83).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of Olmsted County community residents with bicuspid aortic valve overall and grouped according to the presence or absence of valve degeneration at diagnosis (degeneration score < or ≥3) by echocardiography

| Population | Total | Valve degeneration at diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N=212 | Absent N=184 | Present N=28 | P value |

| Age, years | 32±20 | 28±19 | 52±16 | <0.01 |

| Male sex, n (percent) | 138 (65) | 117 (64) | 21 (75) | 0.23 |

| Hypertension, n (percent) | 43 (20) | 31 (17) | 12 (43) | 0.003 |

| Diabetes, n (percent) | 5 (2) | 3 (2) | 2 (7) | 0.13 |

| Smoking, n (percent) | 56 (26) | 45 (24) | 11 (39) | 0.09 |

| Ejection click, n (percent) | 71 (33) | 67 (36) | 4 (14) | 0.01 |

| Systolic murmur, n (percent) | 162 (76) | 139 (76) | 23 (82) | 0.41 |

| Diastolic murmur, n (percent) | 35 (17) | 30 (17) | 5 (19) | 0.78 |

| Typical BAV, n (percent) | 182 (86) | 157 (85) | 25 (89) | 0.56 |

| Visible raphe, n (percent) | 103 (49) | 83 (45) | 20 (71) | <0.01 |

| Systolic doming, n (percent) | 108 (51) | 96 (52) | 12 (43) | 0.42 |

| Ejection fraction, percent | 63±5 | 64±5 | 63±5 | 0.40 |

| LVD, mm | 48±9 | 48±9 | 50±5 | 0.42 |

| Aortic regurgitation, n (percent) | 100 (47) | 82 (45) | 18 (64) | 0.03 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.03±0.4 | 1.03±0.4 | 1.06±0.2 | 0.51 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 198±45 | 193±42 | 220±52 | 0.05 |

BAV=bicuspid aortic valve, LVD=left ventricular end-diastolic dimension.

Long-term clinical outcome

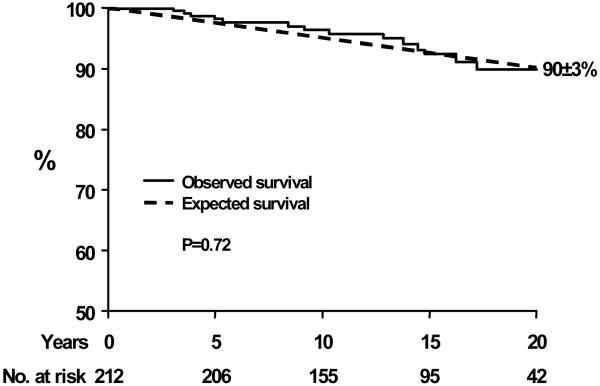

Follow-up was complete (for survival and morbid complications) up to July 2005-July 2006 or death in 196 (93%) of patients. The remaining 7% in whom last contact was earlier than 2005 were nevertheless followed 11±6 years. Total follow-up was 15±6 years (0.4-25 years) during which 14 deaths occurred of which 3 were related to the aortic valve (endocarditis, aortic stenosis and aortic regurgitation, one each). No death was related to ascending aortic or congenital disease complications. Survival was 97±1 and 90±3%, 10 and 20 years after diagnosis and was identical to expected survival of the population matched for age and sex (p=0.72, Fig. 2). Observed vs. expected survival comparison stratified by age at diagnosis, showed no excess mortality in the <20 years age-group (15 years 100 vs. 99%, p=0.38), 20-49 age-group (15 years 93 vs. 96%, p=0.55) and ≥50 age-group (15 years 64 vs. 66%, p=0.60).

Figure 2.

Survival after diagnosis of asymptomatic community members with bicuspid aortic valve (solid line) compared to the expected survival in the same community (dashed line). The numbers at the bottom indicate the patients at risk for each interval. The survival (±SE) is indicated 20 years after diagnosis.

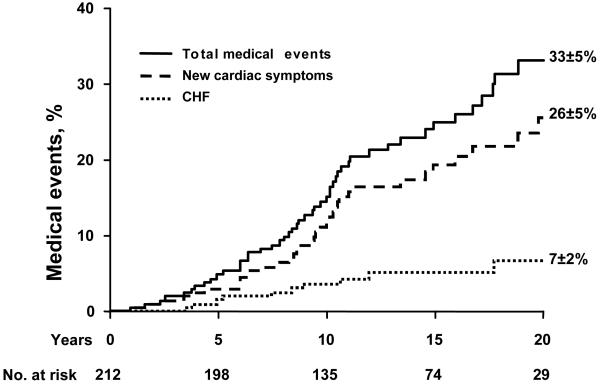

During follow-up, congestive heart failure occurred in 10 patients (7±2% at 20 years) and new cardiac symptoms (dyspnea, syncope or angina) occurred in 41 patients (26±4% at 20 years, Fig. 3). Four patients were diagnosed with bacterial endocarditis (subsequently 1 died and 3 underwent AVR) and stroke occurred in 5 patients. Thus, the incidence of cardiovascular medical events (cardiac death, heart failure, new symptoms, endocarditis or stroke) was 33±5% 20 years after diagnosis (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Incidence of total medical events (cardiac death, congestive heart failure, new cardiac symptoms, stroke and endocarditis; solid line), new cardiac symptoms (dyspnea, cardiac chest pain and syncope; dashed line) and congestive heart failure (CHF; dotted line). The numbers at the bottom indicate the patients at risk for each interval. The event rates (±SE) are indicated at 20 years.

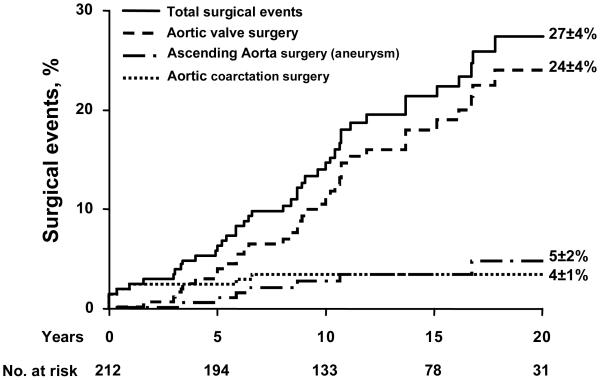

During follow-up, aortic valve surgery was performed in 39 patients, involving aortic valvotomy in 3 patients, 2 of whom later required reoperation (AVR) so that AVR was ultimately performed in 38 patients. AVR was indicated for severe aortic stenosis in 26 patients, severe aortic regurgitation in 6 and severe mixed aortic valve disease in 2 while moderate valve dysfunction with severe ascending aortic dilatation was present in 3 and acute endocarditis in 1. AVR was indicated for new symptoms or heart failure in 26 patients (68 percent) while asymptomatic aortic dilatation or ventricular dysfunction due to severe valve dysfunction justified the indication in 7 patients (18%) and patient and/or physician preference justified the indication in 5 patients. The time from diagnosis to valve surgery was 11±6 years and age at surgery was 49±20 years. Thus, 20-year aortic valve surgery incidence was 24±4% (Fig. 4). Eight patients required surgery for aortic coarctation leading to a 20-year rate of 4±1% and 8 patients required surgery for ascending aortic dilatation or aneurysm leading to a 20-year rate of 5±2% (Fig. 4). Among the 143 patients who underwent follow-up echo, aortic dilatation increased (diameter progressing from 35.5±6 to 39.4±7 mm, p<0.001 in patients initially older than 18 over 10±6 years of echocardiographic follow-up). Ascending aorta dilatation (>40mm) was noted in 15% at baseline and 39% at follow-up. There was no aortic dissection diagnosed or operated during follow-up.

Figure 4.

Incidence of total surgical events (aortic valve, ascending aorta, aortic coarctation; solid line), of aortic valve surgery (aortic valve replacement or surgical valvotomy; dashed line), of ascending aortic surgery (dashed and dotted line) and aortic coarctation surgery (dotted line). The numbers at the bottom indicate the patients at risk for each interval. The event rates (±SE) are indicated at 20 years.

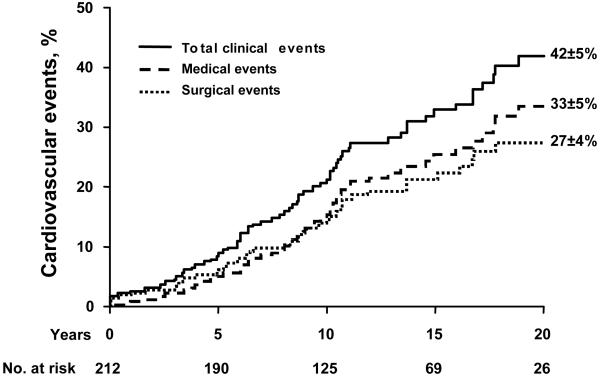

Thus, 20-year rate of surgical events (aortic valve or aorta) was 27±4% and rate of any cardiovascular event (medical or surgical) was 42±5% (Fig. 5). Excluding patients with coarctation, 20-year rates of cardiovascular medical, surgical and total events (35±5, 25±4, 40±5) were unaffected. The patients diagnosed up to 1985 vs. after 1985 had similar rates of medical (at 20 years 33±7% vs. 33±7%, p=0.88) and surgical events (at 20 years 26±7 vs. 27±5%, p=0.83).

Figure 5.

Incidence of any cardiovascular event (total of medical or surgical; solid line), of medical events (cardiac death, congestive heart failure, new cardiac symptoms, stroke and endocarditis; dashed line) and of surgical events (aortic valve replacement, surgical valvotomy, ascending aorta surgery or coarctation surgery; dotted line). The numbers at the bottom indicate the patients at risk for each interval. The event rates (±SE) are indicated at 20 years.

Comparing cardiovascular events in BAV vs. general population is difficult to conduct because population age- and sex-specific expected rates of morbid events are not available. With regard to CHF, in our BAV population the annual incidence rate was 370 per 100,000 subject-years while published overall CHF incidence rates in Olmsted County are between 378 and 280 per 100,000 subject-years respectively for men and women.29 However, our BAV population is young at diagnosis so that expected CHF rates for age are very low.30 Importantly, CHF occurs at the age of 62±20 years vs. 76±12 years in the general population (p=0.0002) demonstrating that CHF occurs prematurely in BAV as compared the general population. With regard to need for AVR, there are no national complete statistics. In Olmsted County, MN, during the period 1990-99, 190 patients underwent AVR with or without bypass leading to an estimated incidence rate of 19 per 100,000 subject-years, which contrasts with a rate of 1370 per 100,000 subject-years in our patients with BAV. Furthermore, AVR for BAV was performed at a younger age for BAV than for tricuspid aortic valve in our community (49±20 vs. 67±16 years, p<0.0001) demonstrating that need for AVR occurs prematurely in BAV compared to the general population.

Predictors of clinical events(Table 2)

TABLE 2.

Independent Predictors of Outcome after Diagnosis

| Endpoints | Independent Multivariate Predictors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | HR | CI | p value | ||

| Medical Cardiovascular Events | Cardiac Death, CHF, New CV Symptoms, Stroke, Endocarditis | Age≥50 years | 4.7 | 2.2-9.6 | <0.01 |

| Valve Degeneration | 2.6 | 1.2-5.3 | 0.016 | ||

| Surgical Cardiovascular Events | Aortic Valve Surgery, Thoracic Aorta Surgery | Age≥50 years | 2.9 | 1.3-6.2 | 0.01 |

| Valve Degeneration | 4.5 | 2.1-9.3 | <0.01 | ||

| Aortic Valve Surgery | Valvotomy or valve replacement | Age≥50 years | 4.8 | 2.0-11.6 | <0.01 |

| Valve Degeneration | 6.9 | 3.0-15.5 | <0.01 | ||

| Aortic Aneurysm Surgery | Baseline Aorta≥40 mm | 10.8 | 1.8-77.3 | <0.01 | |

| Total Events | Medical or Surgical Events | Age≥50 years | 3.0 | 1.5-5.7 | <0.01 |

| Valve Degeneration | 2.4 | 1.2-4.5 | 0.016 | ||

CHF: Congestive heart failure; CV: Cardiovascular

Characteristics noted at diagnosis used as candidate predictors of outcome were age, sex, hypertension, ejection fraction, BAV type, presence of aortic regurgitation, total cholesterol, ascending aortic diameter and degeneration score.

For all cardiovascular events (medical and surgical) univariately, the most powerful predictor was older age (hazard ratio 4.4[2.4-7.9], p<0.01). While hypertension and ascending aortic diameter were univariately predictive of cardiovascular events (both p<0.01), adjusting for age and sex, these characteristics lost their association to outcome (both p>0.60). Baseline systolic or diastolic murmur and echocardiographic presence of aortic regurgitation were not associated with events. Conversely, valve degeneration at diagnosis with score ≥3 univariately predicted all cardiovascular events (hazard ratio 3.6[1.9-6.3], p<0.01) and remained so adjusting for age (as continuous variable, p=0.01) and sex. In multivariate analysis, baseline predictors of all cardiovascular events were age≥50 (risk ratio 3.0[1.5-5.7], p<0.01) and valve degeneration (risk ratio 2.4[1.2-4.5] p=0.016). The period of diagnosis (up-to vs. after 1985 did not significantly affect predictors of medical events, p=0.52)

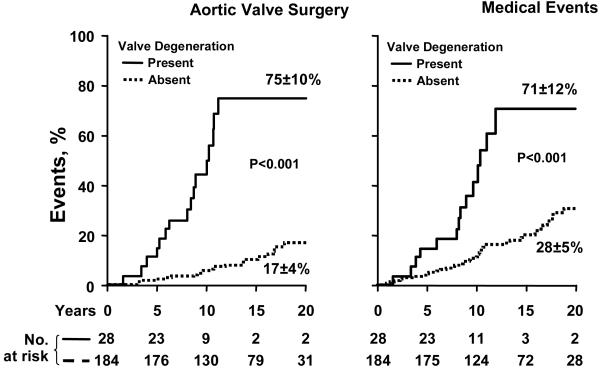

For surgical cardiovascular events, age ≥50 was also independently predictive (2.9[1.3-6.2], p=0.01) with valve degeneration (score≥3) at diagnosis (4.5[2.1-9.3], p<0.01). No other variable was independently predictive of all surgical events. For aortic valve surgery as the surgical endpoint, age≥50 (4.8[2.0-11.6], p<0.01) and valve degeneration (6.9[3.0-15.5], p<0.01) were also independently predictive of outcome. Aortic valve surgery incidence according to presence or absence of valve degeneration at diagnosis at baseline is presented in panel A of Fig. 6, showing a steep increase in surgery rate between 5 and 10 years after diagnosis in patients with valve degeneration at baseline. The period of diagnosis (up-to vs. after 1985) did not significantly affect predictors of surgical events (p=0.64).

Figure 6.

Incidence of events during follow-up according to the presence or absence of valve degeneration at diagnosis (defined as score ≥3 or <3). A-Left graph: Incidence of aortic valve surgery according to baseline valve degeneration at diagnosis. At 12 years aortic valve surgery was 75±10% with and 8±2% without valve degeneration at diagnosis. B-Right graph: Medical event rates according to baseline valve degeneration at diagnosis demonstrating the high medical events rate in patients who display valve degeneration at diagnosis at baseline.

During follow-up 8 underwent ascending aortic surgery for severe aortic dilatation or aneurysm. Ascending aorta ≥40 mm at baseline predicted subsequent aorta surgery (10.8[1.8-77.3], p<0.01) independently of age and sex. Medical cardiovascular events were also independently predicted by age≥50 (4.7[2.2-9.6], p<0.01) and by valve degeneration at baseline (2.6[1.2-5.3], p=0.016). Medical cardiovascular events according to presence or absence of valve degeneration at baseline are presented in panel B of Fig. 6, showing steep increase in event rate between 5 and 10 years after diagnosis with baseline valve degeneration.

Discussion

In this study of 212 asymptomatic community patients with normally functioning or minimally dysfunctional BAV, long-term follow-up to 20 years can be ascertained and provides both reassurance and reason for concern. In this mostly young population, overall mortality was low and no different from that expected for an age and sex matched population. However, cardiovascular morbid events were frequent affecting approximately 4 in 10 patients over 20 years. The main surgical event was aortic valve surgery, performed mostly for aortic stenosis and required at a much higher rate and younger age than in the general population. Surgery for aortic dilatation or coarctation was notable but less common and patients without coarctation had similar event-rates as the entire series. Medical events were frequent and mostly aortic valve related. Endocarditis was rare but serious. Ascending aortic dilatation increased with time becoming ≥40 mm in approximately 4 in 10 patients at follow-up. However, an encouraging observation was that no aortic dissection occurred. Apart from age, a major independent predictor of clinical outcome was presence of valve degeneration at diagnosis by echocardiography, while clinical signs are not discriminant. Despite baseline normal valvular function or minimal dysfunction, valve degeneration at diagnosis is associated with high subsequent event rates (>70% at 20 years). Hence, this first community study of BAV allows separating in clinical practice the majority of patients without valve degeneration in whom only episodic follow-up is necessary from the minority with valve degeneration at diagnosis in whom regular assessment and potential clinical trials of progression prevention should be considered.

Natural history of bicuspid aortic valves

Clinical outcome of patients with BAV has been poorly defined. There are definite reasons for such a gap in knowledge. Patients symptomatic and/or with moderate or severe valve disease are those coming to medical attention and their poor outcome reveals the degree of valve dysfunction rather the original valve deformation.31 Asymptomatic patients are usually not coming to medical attention,31 and from that point of view our community in which frequent contact to health care providers is the rule,32 offers a particular advantage. Also historical studies based solely on auscultatory diagnosis have been at a definitive disadvantage in accurately identifying and ascertaining BAV.17 While echocardiography allows reliable BAV identification, referral centers collect mostly referred patients with potential comorbidity and serious valve disease.18 Therefore, it is not surprising that results reported in the literature are based on small series and quite discordant. It has been suggested that endocarditis of BAV is the most prevalent complication,17 and is frequent and severe.4 Autopsy series painted a bleak picture, with high frequency of endocarditis and valve dysfunction leading to patients’ demise.5 Other series touted rapid progression to aortic stenosis,6,7 while it was also suggested that aortic regurgitation may be the most prominent threat.18 These discordant and concerning reports are confusing as to what guidelines for clinical management of patients with BAV presenting with no or minimal hemodynamic abnormalities should be.33 In our community, frequent population-health care provider contacts and high imaging utilization allow early detection of BAV, thus providing first large series with long-term outcome of affected community members.

Our study both reassures and raises concerns regarding outcome of BAV with no or minimal hemodynamic dysfunction. A favorable result is that no excess mortality is observed 20 years after diagnosis. Later in life, BAV may exert a toll on life expectancy but within 20-year span, one can reassure patients with this condition irrespective of their age at diagnosis. Another favorable observation regards endocarditis, which may have serious consequences, but is infrequent in BAV.

Conversely, morbid events were frequent and over 20-year follow-up 4 patients in 10 incur a cardiovascular medical or a surgical event. The dominant morbid event is progression to aortic stenosis with development of symptoms or heart failure and requirement ofAVR.6,7 Our comparison to the Olmsted county population shows that AVR is required in subjects with BAV not only at higher rates but also at a younger age. Progression to aortic stenosis is complex with similarities to atherosclerosis and in some studies association to cholesterol levels.34 More recent studies emphasized a biphasic progression, with atherosclerotic initial lesion and secondarily geometric growth of calcifications independently of atherosclerotic risk factors.35 Imaging studies suggesting that valve sclerosis tends to progress36 are coherent with our observations in BAV. Despite quasi-normal valve hemodynamics, presence of valve degeneration, independently of age, portends a negative prognosis regarding future clinical events mostly related to progression to aortic stenosis. Valve degeneration supersedes potential impact of BAV morphology (typical vs. atypical) on progression, for which previous reports were discordant.15,26 Thus, patients with valve degeneration require relatively close follow-up that quasi-normal hemodynamics would not a-priory suggest. Medical treatment of patients with BAV to prevent progression to aortic stenosis is conjectural. Statins were not effective in preventing progression of advanced valve lesions but their role in early valve lesions is still an open question,37 particularly relevant with BAV. Progression mechanisms towards severe aortic regurgitation are poorly understood and deserve future studies to appreciate the factors leading to this less frequent but important complication.

Aortic complications associated with Bicuspid valves

Aortic complications of BAV are the focus of much controversy. Reports of referral centers suggested aortic dissection risk 5 to 9 times greater in bicuspid than tricuspid valves2,14 while others did not notice such association17,18 and while a large international registry of aortic dissections denoted low BAV prevalence (<2 percent).38 Contradictory data are also reported on aortic dilatation associated with BAV. While studies with mostly severe valve diseases suggested frequent aortic dilatation,11,12 others showed no such association.39 Thus, it remained unclear whether patients with BAV should be managed aggressively to monitor and protect from aortic dilatation and dissection or whether a more lenient approach is in order.

Our study both reassures and raises important issues of follow-up. For aortic dissection, reassurance is in order in patients diagnosed with minimal valvular dysfunction. With severe BAV dysfunction or after AVR, risk of aortic dissection may be higher.40 However, as we previously suspected,10 accelerated aortic dilatation is real in BAV, even without severe aortic stenosis or regurgitation and even without aortic coarctation.24,25 Indeed, approximately 4 in 10 patients develop notable ascending aorta dilatation during follow-up which then predicts subsequent need for ascending aortic surgery. Thus, aortic complication risk is notable, often requiring surgical correction, particularly when aortic dilatation is present at baseline. The wide confidence interval regarding the association of aortic dilatation and ascending aortic surgery is due to the relatively small event number (despite the fact that our series is the largest available) and will require further collaborative and large studies.

Clinical implications

Overall, patients diagnosed incidentally with BAV should be reassured that their condition is manageable and that major complications, mortality, endocarditis and aortic dissection are rare.

Conversely, these patients should be made aware that morbid events directly linked to the BAV are rather frequent and premature for age. These events are particularly frequent in patients with valve degeneration at diagnosis who despite quasi-normal hemodynamics are at risk of developing severe valve disease, particularly aortic stenosis, justifying regular assessment during follow-up. Also, patients with aortic dilatation are at risk of requiring ascending aortic surgery. Those who have neither valve degeneration nor aortic dilatation at baseline are at low risk of complication and can be followed episodically. A corollary of these findings is the importance of echocardiographic diagnosis of BAV in asymptomatic patients and thus of clinical skills in detecting and interpreting cardiac clicks and murmurs.

Limitations

BAV is a congenital valve condition. While BAV appears in-utero follow-up and analysis of outcome can only start at diagnosis due to potential undiagnosed disease bias. Furthermore, this approach provides clinically useful information on expected outcome after diagnosis in clinical practice. BAV may also be associated with other congenital heart disease. However, exclusion of symptomatic patients with notable comorbidity limited this concern. Even after exclusion of coarctation event-rates were almost unaffected, a reassuring observation.

During the study period, technical Doppler-Echocardiographic progress allowed marked improvement in the assessment of valve disease severity. However, for detecting patients with normal or near normal valve hemodynamics, we believe that adequate techniques were available throughout the study period. Indeed, wide valve area visible in systole ensures absence of valve stenosis. Pulsed-Doppler examination of left ventricular outflow tract and/or aortic arch reassures for regurgitation. Concordant normal left ventricular size and benign clinical presentation support the absent or minimal hemodynamic valve alteration. In that regard, the identical outcome observed in patients diagnosed up-to vs. after 1985 reassures that the outcomes described are not biased by undiagnosed moderate or severe valve disease.

BAV diagnosis is not always easy. We excluded patients with questionable cusp numbers by echo and among those operated, in 3 the cusp numbers could not be determined pathologically, 1 had a unicuspid leaflet mimicking a bicuspid one and all others had BAV confirmation. Attention at recording well-oriented short-axis view is essential to appropriate BAV diagnosis. For simplification purpose, BAV were classified in two types, as fusion of left and non-coronary cusps is extremely rare. Diagnosis of valve sclerosis or degeneration previously was only qualitative36 and the present reproducible scoring system improves echocardiographic assessment. The score is a continuous variable but different thresholds did not affect our results. Medical events were 70±10, 71±12 and 76±12% with scores 2, 3 and 4 respectively and 26±5, 28±5 and 29±5% without, showing that event-rates are little affected by selected thresholds. Thus, it is more important to underscore reproducible detection of valve degeneration than specific score.

Valve degeneration is linked to age (Table 1) and predictive power for outcome independent of age is important to confirm. Age overlap between groups with and without degeneration allows detecting that degeneration is predictive of outcome independently of age, with model improvement by addition of degeneration to age (p=0.05). We were able to match for age (51 vs. 47 years, p=0.23), sex (p=0.99) and ejection fraction (p=0.86) patients with (n=26) and without (n=51) valve degeneration, and confirmed that those with degeneration, despite similar age, had higher 15-year cardiovascular event rates (75±10 vs. 35±8%, p=0.018) univariately and in multivariate analysis (2.3[1.13-4.8], p=0.02).

Screening of an entire population would provide true prevalence, but resources for such massive endeavor (approximately 40,000 echocardiograms) are not available,3 while our data obtained from all cases diagnosed in a community, informs on outcome, risk factors and management of presently detected community members with BAV. Similarly, changes in valvular degeneration progression rates with changes in risk factors will require large populations in multicenter studies that can now be planned using our outcome data

Conclusion

Our long-term, up to 20 years outcome study of asymptomatic community members with BAV displaying no or minimal hemodynamic deterioration provides both reassurance and reason for concern. Reassuring are the preserved life expectancy and the rarity of endocarditis or aortic dissection. Conversely, concerns are raised by frequent and premature occurrence of morbid cardiac events. These are dominated by development of symptoms or heart failure due to progression of aortic stenosis and are less frequently due to aortic regurgitation or development of severe ascending aorta dilatation requiring surgery. Patients with aortic valve degeneration at diagnosis are at higher risk for cardiac events and those with enlarged aorta are at notable risk for requiring surgery of the aorta, calling for regular assessment in such patients and emphasizing the importance of echocardiographic diagnosis in patients in whom BAV may be suspected.

Acknowledgments

The authors had full access to and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data. All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: “This is an un-copyedited author manuscript that was accepted for publication in Circulation, copyright The American Heart Association. This may not be duplicated or reproduced, other than for personal use or within the “Fair Use of Copyrighted Materials” (section 107, title 17, U.S. Code) without prior permission of the copyright owner, The American Heart Association. The final copyedited article, which is the version of record, can be found at http://circ.ahajournals.org. The American Heart Association disclaims any responsibility or liability for errors or omissions in this version of the manuscript or in any version derived from it by the National Institutes of Health or other parties.”

Conflict of Interest Disclosures relevant for the topic for all authors: None

Contributor Information

Hector I. Michelena, Division of Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic, Rochester.

Valerie A. Desjardins, Centre Hospitalier Pierre Le Gardeur, Lachenaie, Qc, Canada.

Jean-François Avierinos, La Timone Hospital, Marseille, France.

Antonio Russo, University Hospital of Bologna, Bologna, Italy.

Vuyisile T. Nkomo, Division of Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic, Rochester.

Thoralf M Sundt, Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Rochester.

Patricia A. Pellikka, Division of Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic, Rochester.

A. Jamil Tajik, Division of Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic, Arizona.

Maurice Enriquez-Sarano, Division of Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic, Rochester.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roberts WC. The congenitally bicuspid aortic valve. A study of 85 autopsy cases. Am J Cardiol. 1970;26:72–83. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(70)90761-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larson EW, Edwards WD. Risk factors for aortic dissection: a necropsy study of 161 cases. Am J Cardiol. 1984;53:849–55. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(84)90418-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinberger J, Moller JH, Berry JM, Sinaiko AR. Echocardiographic diagnosis of heart disease in apparently healthy adolescents. Pediatrics. 2000;105:815–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.4.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamas CC, Eykyn SJ. Bicuspid aortic valve--A silent danger: analysis of 50 cases of infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:336–41. doi: 10.1086/313646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenoglio JJ, Jr., McAllister HA, Jr., DeCastro CM, Davia JE, Cheitlin MD. Congenital bicuspid aortic valve after age 20. Am J Cardiol. 1977;39:164–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(77)80186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Subramanian R, Olson LJ, Edwards WD. Surgical pathology of pure aortic stenosis: a study of 374 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1984;59:683–90. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts WC, Ko JM. Frequency by decades of unicuspid, bicuspid, and tricuspid aortic valves in adults having isolated aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis, with or without associated aortic regurgitation. Circulation. 2005;111:920–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155623.48408.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts WC, Morrow AG, McIntosh CL, Jones M, Epstein SE. Congenitally bicuspid aortic valve causing severe, pure aortic regurgitation without superimposed infective endocarditis. Analysis of 13 patients requiring aortic valve replacement. Am J Cardiol. 1981;47:206–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(81)90385-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olson LJ, Subramanian R, Edwards WD. Surgical pathology of pure aortic insufficiency: a study of 225 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1984;59:835–41. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)65618-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nkomo VT, Enriquez-Sarano M, Ammash NM, Melton LJ, 3rd, Bailey KR, Desjardins V, Horn RA, Tajik AJ. Bicuspid aortic valve associated with aortic dilatation: a community-based study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:351–6. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000055441.28842.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hahn RT, Roman MJ, Mogtader AH, Devereux RB. Association of aortic dilation with regurgitant, stenotic and functionally normal bicuspid aortic valves. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;19:283–8. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90479-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keane MG, Wiegers SE, Plappert T, Pochettino A, Bavaria JE, Sutton MG. Bicuspid aortic valves are associated with aortic dilatation out of proportion to coexistent valvular lesions. Circulation. 2000;102:III35–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.suppl_3.iii-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pachulski RT, Weinberg AL, Chan KL. Aortic aneurysm in patients with functionally normal or minimally stenotic bicuspid aortic valve. Am J Cardiol. 1991;67:781–2. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90544-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts CS, Roberts WC. Dissection of the aorta associated with congenital malformation of the aortic valve. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:712–6. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beppu S, Suzuki S, Matsuda H, Ohmori F, Nagata S, Miyatake K. Rapidity of progression of aortic stenosis in patients with congenital bicuspid aortic valves. Am J Cardiol. 1993;71:322–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90799-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otto CM, Burwash IG, Legget ME, Munt BI, Fujioka M, Healy NL, Kraft CD, Miyake-Hull CY, Schwaegler RG. Prospective study of asymptomatic valvular aortic stenosis. Clinical, echocardiographic, and exercise predictors of outcome. Circulation. 1997;95:2262–70. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.9.2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mills P, Leech G, Davies M, Leathan A. The natural history of a non-stenotic bicuspid aortic valve. Br Heart J. 1978;40:951–7. doi: 10.1136/hrt.40.9.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pachulski RT, Chan KL. Progression of aortic valve dysfunction in 51 adult patients with congenital bicuspid aortic valve: assessment and follow up by Doppler echocardiography. Br Heart J. 1993;69:237–40. doi: 10.1136/hrt.69.3.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kotler MN, Mintz GS, Parry WR, Segal BL. M mode and two dimensional echocardiography in mitral and aortic regurgitation: pre- and postoperative evaluation of volume overload of the left ventricle. Am J Cardiol. 1980;46:1144–52. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(80)90285-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tajik AJ, Seward JB, Hagler DJ, Mair DD, Lie JT. Two-dimensional real-time ultrasonic imaging of the heart and great vessels. Technique, image orientation, structure identification, and validation. Mayo Clin Proc. 1978;53:271–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishimura RA, Miller FA, Jr., Callahan MJ, Benassi RC, Seward JB, Tajik AJ. Doppler echocardiography: theory, instrumentation, technique, and application. Mayo Clin Proc. 1985;60:321–43. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60540-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quinones MA, Waggoner AD, Reduto LA, Nelson JG, Young JB, Winters WL, Jr., Ribeiro LG, Miller RR. A new, simplified and accurate method for determining ejection fraction with two-dimensional echocardiography. Circulation. 1981;64:744–53. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.64.4.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rich S, Sheikh A, Gallastegui J, Kondos GT, Mason T, Lam W. Determination of left ventricular ejection fraction by visual estimation during real-time two-dimensional echocardiography. Am Heart J. 1982;104:603–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(82)90233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duran AC, Frescura C, Sans-Coma V, Angelini A, Basso C, Thiene G. Bicuspid aortic valves in hearts with other congenital heart disease. J Heart Valve Dis. 1995;4:581–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sabet HY, Edwards WD, Tazelaar HD, Daly RC. Congenitally bicuspid aortic valves: a surgical pathology study of 542 cases (1991 through 1996) and a literature review of 2,715 additional cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:14–26. doi: 10.4065/74.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernandes SM, Sanders SP, Khairy P, Jenkins KJ, Gauvreau K, Lang P, Simonds H, Colan SD. Morphology of bicuspid aortic valve in children and adolescents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1648–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perry GJ, Helmcke F, Nanda NC, Byard C, Soto B. Evaluation of aortic insufficiency by Doppler color flow mapping. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;9:952–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(87)80254-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Currie PJ, Seward JB, Reeder GS, Vlietstra RE, Bresnahan DR, Bresnahan JF, Smith HC, Hagler DJ, Tajik AJ. Continuous-wave Doppler echocardiographic assessment of severity of calcific aortic stenosis: a simultaneous Doppler-catheter correlative study in 100 adult patients. Circulation. 1985;71:1162–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.71.6.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roger VL, Weston SA, Redfield MM, Hellermann-Homan JP, Killian J, Yawn BP, Jacobsen SJ. Trends in heart failure incidence and survival in a community-based population. Jama. 2004;292:344–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodeheffer RJ, Jacobsen SJ, Gersh BJ, Kottke TE, McCann HA, Bailey KR, Ballard DJ. The incidence and prevalence of congestive heart failure in Rochester, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:1143–50. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, Gottdiener JS, Scott CG, Enriquez-Sarano M. Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study. Lancet. 2006;368:1005–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–74. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Kanu C, de Leon AC, Jr., Faxon DP, Freed MD, Gaasch WH, Lytle BW, Nishimura RA, O’Gara PT, O’Rourke RA, Otto CM, Shah PM, Shanewise JS, Smith SC, Jr., Jacobs AK, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Fuster V, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Hunt SA, Nishimura R, Page RL, Riegel B. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease): developed in collaboration with the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists: endorsed by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2006;114:e84–231. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan KL, Ghani M, Woodend K, Burwash IG. Case-controlled study to assess risk factors for aortic stenosis in congenitally bicuspid aortic valve. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:690–3. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01820-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Messika-Zeitoun D, Bielak LF, Peyser PA, Sheedy PF, Turner ST, Nkomo VT, Breen JF, Maalouf J, Scott C, Tajik AJ, Enriquez-Sarano M. Aortic Valve Calcification. Determinants and Progression in the Population. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:642–8. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000255952.47980.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cosmi JE, Kort S, Tunick PA, Rosenzweig BP, Freedberg RS, Katz ES, Applebaum RM, Kronzon I. The risk of the development of aortic stenosis in patients with “benign” aortic valve thickening. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2345–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan KL. Is aortic stenosis a preventable disease? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:593–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00786-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Januzzi JL, Isselbacher EM, Fattori R, Cooper JV, Smith DE, Fang J, Eagle KA, Mehta RH, Nienaber CA, Pape LA. Characterizing the young patient with aortic dissection: results from the International Registry of Aortic Dissection (IRAD) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:665–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.La Canna G, Ficarra E, Tsagalau E, Nardi M, Morandini A, Chieffo A, Maisano F, Alfieri O. Progression rate of ascending aortic dilation in patients with normally functioning bicuspid and tricuspid aortic valves. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:249–53. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.01.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russo CF, Mazzetti S, Garatti A, Ribera E, Milazzo A, Bruschi G, Lanfranconi M, Colombo T, Vitali E. Aortic complications after bicuspid aortic valve replacement: long-term results. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:S1773–6. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04261-3. discussion S1792-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]