Abstract

A hallmark feature of Ca2+/calmodulin (CaM)-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) regulation is the generation of Ca2+-independent autonomous activity by Thr-286 autophosphorylation. CaMKII autonomy has been regarded a form of molecular memory and is indeed important in neuronal plasticity and learning/memory. Thr-286-phosphorylated CaMKII is thought to be essentially fully active (∼70–100%), implicating that it is no longer regulated and that its dramatically increased Ca2+/CaM affinity is of minor functional importance. However, this study shows that autonomy greater than 15–25% was the exception, not the rule, and required a special mechanism (T-site binding; by the T-substrates AC2 or NR2B). Autonomous activity toward regular R-substrates (including tyrosine hydroxylase and GluR1) was significantly further stimulated by Ca2+/CaM, both in vitro and within cells. Altered Km and Vmax made autonomy also substrate- (and ATP) concentration-dependent, but only over a narrow range, with remarkable stability at physiological concentrations. Such regulation still allows molecular memory of previous Ca2+ signals, but prevents complete uncoupling from subsequent cellular stimulation.

Keywords: Calcium, Calcium/Calmodulin, Enzymes/Kinase, Neurobiology/Neuroscience, Signal Transduction/Protein Kinases/Calmodulin, Signal Transduction/Protein Kinases/Serine/Threonine

Introduction

Ca2+/calmodulin (CaM)2-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) can phosphorylate a large variety of substrate proteins and is a key player in many Ca2+-regulated cellular events (for review see Refs. 1–4). However, CaMKII is best know for its regulation of long term potentiation of synaptic strength (LTP) (5, 6), likely by increasing both number (7) and single channel conductance (8, 9) of synaptic AMPA-type glutamate receptors, and possibly by stimulating BDNF production (10, 11) (for review see Refs. 1–4). CaMKII autophosphorylation at Thr-286 generates Ca2+-independent autonomous activity (12–14), a process regarded as molecular memory (for review see Ref. 2) and indeed important in learning and memory (15).

Phosphorylation in the activation loop is a necessary step to generate full activity of many kinases, including PKA, PKC, and several CaMKs (for review see Refs. 16, 17). By contrast, CaMKII is thought to be fully activated by Ca2+/CaM alone, without requirement for phosphorylation. Its Thr-286 is not located in the activation loop, but in the N-terminal half of the autoinhibitory α-helix, which binds to the T-site (Thr-286-interaction site; Ref. 18) in the basal state of CaMKII (19) (Fig. 1A). The C-terminal portion of the autoinhibitory α-helix extends to block the substrate binding site (S-site)(19) (Fig. 1A). Ca2+/CaM binding to the autoinhibitory α-helix relieves the S-site block, and makes Thr-286 accessible for phosphorylation by a neighboring kinase subunit within the 12meric CaMKII holoenzyme (20–22). Phospho-T286 then prevents complete re-binding of the autoinhibitory α-helix.

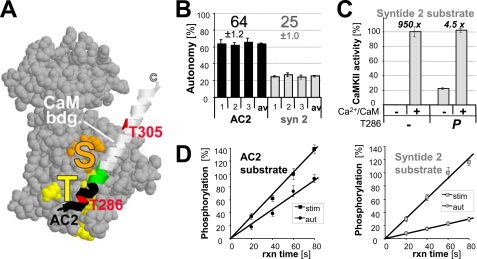

FIGURE 1.

CaMKII autonomy is substrate-dependent. A, CaMKII kinase domain (19) with the autoregulatory α-helix shown as a ribbon, containing the CaM binding site (white), Thr-286, and Thr-305 (red). The substrate binding S-site (orange) and the Thr-286 region binding T-site (yellow) are marked. AC2 is derived from the region shown in black. B, CaMKII (2.5 nm) autonomy toward the substrate peptides AC2 and syntide2 (75 μm) differed significantly from each other on three experimental days. Autonomy reflects the activity of Thr-286-autophosphorylated CaMKII after chelating Ca2+ with EGTA, relative to the activity of naïve CaMKII maximally stimulated by Ca2+/CaM (2 μm). C, Ca2+/CaM stimulated naïve CaMKII 950-fold, but still stimulated autonomous CaMKII 4.5-fold, at least for syntide2. D, measurement of stimulated (stim; Ca2+/CaM) and autonomous (aut; EGTA) CaMKII activity was in the linear range, as ascertained by stopping the reactions at different time points. Stimulated phosphorylation after 60 s was set as 100%. Error bars indicate S.E. in all panels.

The dual role of Ca2+/CaM in Thr-286 autophosphorylation (for kinase activation and substrate presentation) allows computation of temporal patterns in Ca2+ signaling, and indeed, CaMKII autonomy is dependent on the frequency of stimulation (23, 24). Such decoding of temporal patterns clearly requires short-term molecular memory of the stimulation history. Ever since its discovery, CaMKII autonomy has been speculated to also provide long-term memory storage (Refs. 12, 13; for review see Ref. 2). Indeed, autonomy-deficient T286A mutant mice are impaired in both LTP and in learning/memory (15).

It is generally believed that Thr-286-phosphorylated CaMKII is almost fully active (∼70–100%) (for review see Refs. 1–4), implicating that it can no longer be regulated and that its dramatically increased affinity for CaM (25) is of minor functional importance in regulating kinase activity. However, while there are indeed many reports of high autonomy (>70%)(13, 23, 26), there are also reports of much lower autonomy (∼20%)(12, 27) as well as some reports of medium levels of autonomy (∼40–60%)(14, 28), in studies that included the same substrates. High autonomy levels have prevailed in the general perception as better estimates, likely because it was easier to explain findings of low autonomy by submaximal experimental conditions than explaining high autonomy by supermaximal conditions.

Surprisingly, the results of this study show that CaMKII autonomy is substrate-dependent: Autonomous activity toward regular substrates was found to be low (15–25%) and significantly further stimulated by Ca2+/CaM. Higher autonomy (∼65%) seen for the same kinase preparation in parallel assays was found to be an exception that required a special mechanism (T-site binding of the substrate). The results directly show that generation of autonomous CaMKII activity does not lead to a complete uncoupling from subsequent neuronal Ca2+ signaling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Proteins and Peptides

CaMKII and CaM were purified as described (18). MAP2 was purchased (Sigma). Peptides were obtained from GenScript or CHI Scientific. mGFP-CaMKII wild type and mutants were expressed in HEK cells; their concentration in the extracts was determined by fluorescence and normalized for total protein (29). GST-NR2B-C (containing the cytoplasmic C terminus of rat NR2B from amino acids 1,120–1,482) was expressed in bacteria as described (18, 30), and purified by glutathione affinity chromatography.

CaMKII Peptide Substrate Phosphorylation

Phosphate incorporation into peptide substrates was assessed as described (18, 29). Assays were done at 30 °C for 1 min and contained 2.5 nm CaMKII kinase subunits, 50 mm PIPES, pH 7.0–7.2, 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 10 mm MgCl, 100 μm [γ-32P]ATP (∼1 mCi/μmol), and 75 μm substrate peptide, or as indicated. Stimulated activity was generally measured for naïve CaMKII (but also for prephosphorylated kinase where indicated) in presence of CaCl2 (1 mm) and CaM (2 μm; 1 μm in Fig. 1C); autonomous activity assays contained EGTA (0.5 mm) instead. CaMKII (50–250 nm) Thr-286 prephosphorylation was done in stimulation buffer, but without substrate and 32P, for >5 min on ice. Before activity assays, CaM dissociation was induced by EGTA (or in Figs. 1C and 3A by EGTA/EDTA) for at least 3 min. CaMKII activity was calculated as pmol of phosphorylated substrate per pmol of CaMKII subunits per min (resulting in the unit product/kinase/min); CaMKII autonomy reflects the ratio of autonomous activity to maximal stimulated activity.

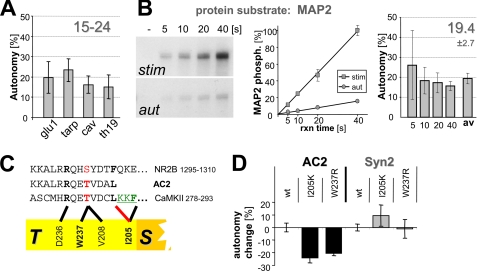

FIGURE 3.

CaMKII autonomy toward regular substrates is only 15–25%. A, CaMKII (20 nm) autonomy toward four peptides (75 μm) derived from cellular CaMKII phosphorylation sites was 15–24% (see supplemental Table S1 for details on the peptides). B, CaMKII autonomy toward the protein substrate MAP2 is <20%. MAP2 (200 nm) phosphorylation by stimulated and autonomous CaMKII (2.5 nm) was quantified using a StormSystem. Reactions were in the linear range, as determined in a time course. C, interactions with the CaMKII T-site involve residues Ile-205 and Trp-237, based on mutational analysis (28). D, T-site mutations I205K and W237R reduce CaMKII autonomy toward AC2 but not syntide2. Error bars indicate S.E. in all panels.

Western Blot Analysis and Protein Phosphorylation

SDS-PAGE, transfer onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and immunodetection were done as described, utilizing antibodies against CaMKIIα (CBα2), all CaMKII isoforms (BD Pharmingen) phospho-T286 or -T305 CaMKII, GluR1 phospho-S831 (PhosphoSolutions), total GluR1 (Calbiochem), or NR2B phospho-S1303 (Millipore) (29). Chemoluminescence was imaged by exposure to Hyperfilm (Amersham Biosciences), or, for quantification, by a CCD camera (alpha Innotech).

Proteins were phosphorylated in the same buffer as peptides, but substrate concentration was 200 nm MAP2 (or 1 μm GST-NR2B-C). After PAGE and transfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, phosphorylation of MAP2 was quantified using a Storm System and ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics).

Phosphorylation within PC12 Cells

PC12 cells were cultured in high serum medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), 10% horse serum, 5% fetal calf serum) on poly-d-lysine/laminin coated plates, differentiated in NGF (10 ng/ml) containing low-serum medium (DMEM, 1% horse serum), and transfected on day 5 using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). On the next day, cells were stimulated for 5 min by KCl depolarization (in 25 mm HEPES pH 7.4, 90 mm KCl, 85 mm NaCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 2 mm MgCl2, and 30 mm glucose) or treated for 5 min with control solution (as above, but containing 2.5 mm KCl and 119 mm NaCl instead) immediately before fixation for immunocytochemistry, done as described (30, 31) using rabbit anti-phospho-S19 TH (p1580–19; PhosphoSolutions) or mouse anti-total TH (mAb318; Chemicon; both at 1:500 dilution).

Phosphorylation within HEK Cells

HEK cells were cultured and transfected by the calcium phosphate method, as done previously (31). 24 h after transfection, cells were stimulated for 3 min by 10 μm ionomycin, and immediately harvested in SDS gel loading buffer. Phospho-S831 and total GluR1 in the extracts were determined by Western blot analysis as described above.

RESULTS

CaMKII Autonomy Is Substrate-dependent

CaMKII autonomy reflects the ratio of autonomous activity to maximal activity. Autonomous activity (in the absence of Ca2+) was measured for CaMKII prephosphorylated at Thr-286; maximal activity (stimulated by Ca2+/CaM) was measured for non-prephosphorylated naïve kinase. Direct comparison of CaMKII autonomy toward the two most commonly used substrate peptides, AC2 and syntide2, in parallel assays, revealed a significant difference (Fig. 1B): Autonomy was ∼65% of maximal stimulated activity for AC2, but only ∼25% for syntide2. Thus, autonomy is substrate-dependent, and low autonomy can be measured for a kinase preparation that is capable of high autonomy under the same conditions but with a different substrate. Ca2+/CaM still stimulated Thr-286-prephosphorylated CaMKII more than 4 fold over autonomous activity, to the same level as stimulated activity of naïve kinase, at least for syntide2 (Fig. 1C). To ascertain that the reactions were in the linear range, they were stopped at different time points (Fig. 1D), excluding the possibility that a saturation effect may have caused the difference (see supplemental Fig. S1 for autonomy and phosphorylation rates at each time point).

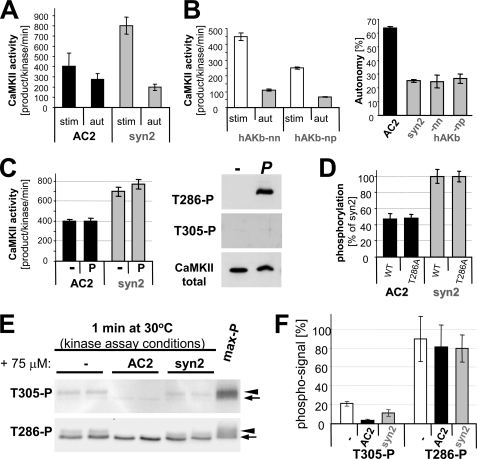

Low Autonomy Is the Default

Three possible mechanisms for substrate dependence of autonomy were ruled out experimentally (Fig. 2 and supplemental results). Briefly, substrate-dependent autonomy was not due to differences in stimulated phosphorylation rates, Thr-286 phosphorylation, or inhibitory Thr-305 phosphorylation (which prevents Ca2+/CaM-binding; Refs. 32–34) (Fig. 2). A major remaining difference between the two substrates tested is their interaction with CaMKII. Syntide2 is a regular substrate (R-substrate) that interacts with the substrate binding site (S-site) only. By contrast, AC2 is derived from the CaMKII autoregulatory region around Thr-286, and can additionally bind at the T-site (T-substrate)(29)(see Fig. 1A). Thus, we hypothesized that T-site interaction of AC2 may enhance the phospho-T286 induced partial displacement of the autoinhibitory α-helix from the T-site, thereby enhancing autonomous activity. If this is the case, AC2 should be an exception, and autonomy toward all regular substrates (S- but not T-site binding) should be low, as seen for syntide2. Thus, a set of four additional peptides (derived from several important CaMKII substrates sites) was examined (Fig. 3A): glu1 (GluR1 Ser-831), tarp (Tarp γ-4 Ser-259), cav (CaV1.2 Ser-439), and TH19 (tyrosine hydroxylase Ser-19) (see supplemental Table S1 for details on the peptides and function of the phosphorylation sites). In these assays, CaMKII concentration was increased, as the four peptides were poor substrates compared with AC2 and syntide2 (see supplemental Fig. S2). For all these peptides, autonomy of 15–25% was observed (Fig. 3A), as was predicted for regular substrates. Peptides are ideal for determining the default activity, as this minimizes the potential for additional levels of regulation that may confound the results. To test if there may be a principle difference in phosphorylation of protein substrates, we chose MAP2, an excellent CaMKII substrate with multiple phosphorylation sites (35). Autonomy toward MAP2 was ∼20% (Fig. 3B), as expected for a regular substrate. A possible saturation effect was again excluded by stopping the reactions at different time points (Fig. 3B). Thus, for all regular substrates tested, autonomous CaMKII activity can be further stimulated 4–6 fold by Ca2+ signals. Not surprisingly, the absolute phosphorylation rates differed widely between the substrates (see Fig. 2, and supplemental Figs. S1 and S2). However, autonomy (reflecting the ratio of autonomous to stimulated phosphorylation rates) was very similar for all regular substrates.

FIGURE 2.

Substrate dependence of CaMKII autonomy is not caused by differential effects on stimulated activity. A, between AC2 and syntide2, the stimulated rate of phosphorylation differed more than the autonomous rate. B, stimulated rate of phosphorylation was not a predictor of autonomy, as two other substrates peptides (derived from AKAP79) with similar or lower stimulated rates than AC2 (left panel; compare A) showed the same degree of autonomy as syntide2 (right panel). C, prephosphorylation of Thr-286 did not significantly affect stimulated activity toward AC2 or syntide2. Prephosphorylation of Thr-286 but not Thr-305 under the experimental conditions was verified by Western blot. D, comparison of CaMKII wild type and T286A showed that Thr-286 phosphorylation has no differential effect on AC2 and syntide2. Phosphorylation rates of syntide2 were normalized to 100% to correct for differences between the two independent enzyme preparations. E, phosphorylation of CaMKII at Thr-305 and Thr-286 during mock-stimulated kinase activity assays (without 32P), with and without added substrates, was assessed by Western analysis. CaMKII and phospho-T286 CaMKII bands (arrow) versus shifted bands after autophosphorylation at additional sited (arrowhead) are indicated. F, quantification of analysis as in E showed that substrate further decreased the low level of inhibitory autophosphorylation at Thr-305, but AC2 even more so than syntide. Level of phosphorylated Thr-286 was not affected by substrate. Error bars indicate S.E. in all panels.

T-site Binding Can Cause Higher Autonomy

Is AC2 really the exception because of its T-site binding? To test this more directly, GFP-CaMKII wild type was compared with two T-site mutants, I205K and W237, predicted to impair T-site interaction of AC2 (Fig. 3C). Indeed, autonomy toward AC2 was significantly reduced by either mutation (Fig. 3D). By contrast, the mutations did not decrease autonomy toward syntide2 (Fig. 3D) or the other regular substrate peptides (supplemental Fig. S2); if any, autonomy appeared elevated in some cases (supplemental Fig. S2), consistent with fewer interactions of a mutated T-site with the autoinhibitory α-helix (28). All peptide phosphorylation reactions were in the linear range (based on total ATP conversion and compared with Fig. 1D). Thus, taken together, T-site binding is the mechanism underlying the elevated CaMKII autonomy toward AC2.

High CaMKII Autonomy Also Toward the Cellular T-substrate NR2B

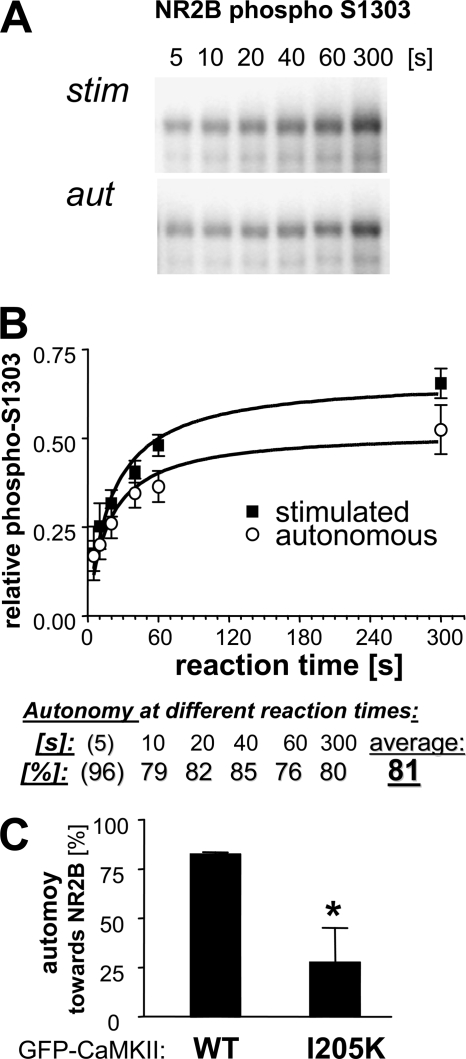

Other than the Thr-286 autophosphorylation site on CaMKII, Ser-1303 on the cytoplasmic C terminus of the NMDA receptor subunit NR2B is the only demonstrated cellular T-substrate (18, 30). Thus, we assessed stimulated and autonomous phosphorylation of a GST-NR2B C terminus fusion protein purified after bacterial overexpression. Specifically, phosphorylation of Ser-1303 after different reaction times was detected on Western blots using a phosphospecific antibody (Fig. 4A) and then quantified (Fig. 4B). At any given reaction time, the observed CaMKII autonomy was high (>75%; Fig. 4B), as predicted for T-substrates. In contrast to other kinase reactions performed in this study, the NR2B Ser-1303 phosphorylation reactions were not in the linear range, likely not even at the 5-s reaction time (Fig. 4 and supplemental Fig. S3). However, the high CaMKII autonomy observed toward NR2B at all reaction times was not due to earlier saturation of the stimulated reactions, as the calculated autonomy was high not only at late but also at early time points (Fig. 4); if any, the levels of autonomy determined for the shortest time reaction time (5 s) was actually higher (Fig. 4B). High autonomy toward NR2B was also observed for GFP-CaMKII, and this autonomy was greatly reduced by a T-site mutation, I205K (Fig. 4C). Thus, taken together, high CaMKII autonomy was an exception observed only for the two known T-substrates AC2 and NR2B Ser-1303.

FIGURE 4.

High autonomy toward the T-substrate protein NR2B. A, phosphorylation of GST-NR2B-c (a GST fusion protein with cytoplasmic C terminus of NR2B; 1 μm) at Ser-1303 by stimulated and autonomous CaMKII (5 nm) activity after different reaction times, as determined by Western blot analysis with a phospho-S1303 specific antibody. B, quantification of NR2B phosphorylation experiments (as shown in A; n = 6) show an average autonomy of 81% (excluding the less reliable 5-s reaction time, which showed even higher autonomy). High autonomy was not due to saturation of the stimulated activity, as the degree of autonomy was similarly high at both short and long reaction times. C, high autonomy of GFP-CaMKII wild type toward NR2B (measured as in B) was reduced by the T-site mutation I205K (*, p < 0.05; Student's t test; n = 3). Error bars indicate S.E. in all panels.

CaMKII Autonomy Is Substrate Concentration-dependent, but Has a Stable Low Phase in the Relevant Range of Cellular Substrate Concentrations

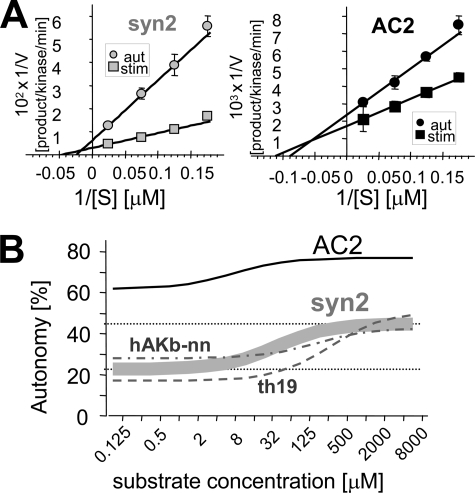

Low autonomy could be due to lower Vmax or higher Km for autonomous compared with stimulated activity. Varying the substrate concentrations revealed both decreased Vmax and increased Km for autonomous activity (Fig. 5A); both changes were larger for the regular substrate syntide2 compared with the T-site binder AC2 (Fig. 5A; supplemental Table S2). Two additional regular substrates showed an effect very similar to syntide2 (supplemental Fig. S4 and Table S2), and none of these regular substrates had any overlapping autonomy with AC2 (Fig. 5B). The dual change in Vmax and Km is important, as it makes autonomy additionally dependent on substrate concentration (by increased Km), but for regular substrates autonomous activity is still >2 fold enhanced by Ca2+/CaM even at infinite concentration (by decreased Vmax)(Fig. 5B). Autonomy at a specific substrate concentration can be calculated based on a modification of the Michaelis-Menten equation (as in Fig. 5B; see also supplemental text) shown in Equation 1,

with r representing the ratio of the autonomous value divided by the stimulated value. This equation results in a sigmoid function between minimal and maximal asymptotes, defined as Equation 2,

|

and Equation 3,

(Fig. 5B). Thus, with a change in both Vmax and Km, CaMKII autonomy is substrate concentration-dependent, but remains near constant both in the low and in the high range of substrate concentration, with a significant change only within a relatively narrow range between the two concentrations (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Autonomous CaMKII activity has both decreased Vmax and increased Km compared with stimulated activity. A, double reciprocal plot of phosphorylation rate as function of substrate concentration for stimulated and autonomous CaMKII activity, for syntide2 (left) and AC2 (right). B, the difference in Km makes CaMKII autonomy additionally substrate concentration-dependent. The difference in Vmax makes autonomous activity toward syntide2 more than 2-fold further stimulated by Ca2+/CaM even at infinite substrate concentration. The curve for syntide2 is based on four independent experiments as in A (see supplemental Table S2). Two additional regular substrates, derived from human AKAP79 (hAKb-nn) and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH19), respectively, (see supplemental Fig. S4) behaved very similarly as syntide2.

Autonomous Activity Can Be Further Stimulated Also at Cellular ATP Concentrations

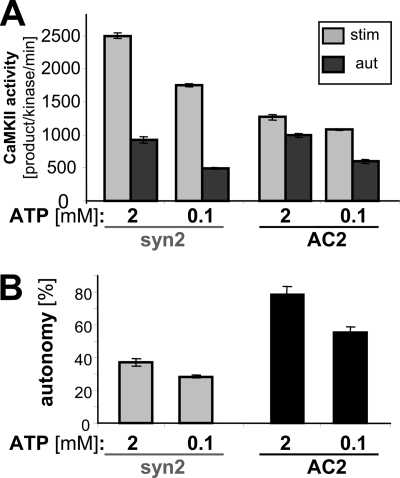

An ATP concentration of 0.1 mm was chosen for our standard CaMKII activity assays, as this concentration is low enough to allow reasonably strong [32P]ATP label per mCi, but is high enough to exceed the reported Km for ATP of ∼8 μm by >10-fold. However, cellular ATP concentration is much higher (in the low mm range), and previous studies have indicated that autonomy may depend on the ATP concentration (27). Thus, we directly compared CaMKII autonomy toward syntide-2 and AC2 at 0.1 mm versus 2 mm ATP (Fig. 6). Autonomy was ATP concentration-dependent, for both the regular and the T-site binding substrate. More importantly, the results showed that autonomous activity toward the regular substrate syntide-2 can be significantly further stimulated by Ca2+/CaM even at the mm ATP concentrations found within cells (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

CaMKII autonomy is dependent on ATP concentration, but can be further stimulated even at the mm concentrations found within cells. A, stimulated and autonomous CaMKII activity toward syntide2 and AC2 was measured at 0.1 mm and 2 mm ATP. B, autonomy (ratio of autonomous to stimulated activity) was significantly higher at 2 mm ATP for both syntide2 and AC2 (and significantly higher for AC2 than for syntide2 at each ATP concentration) (p < 0.01, Student's t test; n = 5). However, most importantly, autonomy at for the R-substrate syntide2 was less than 40% even at 2 mm ATP concentration. Error bars show S.E. in both panels.

Ca2+/CaM Stimulates Phosphorylation of Endogenous Tyrosine Hydroxylase by Autonomous CaMKII within PC12 Cells

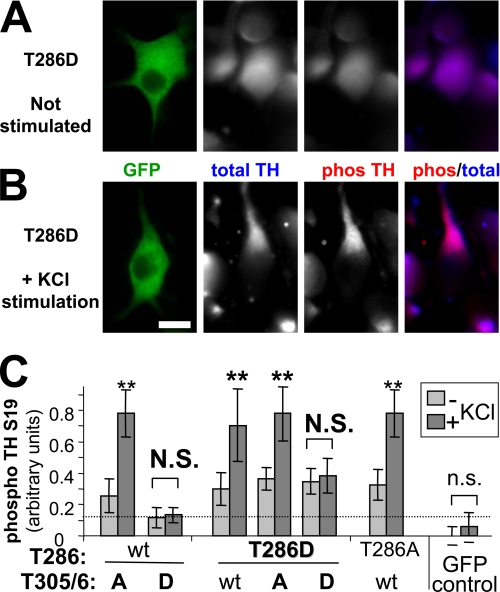

The biochemical data clearly demonstrated that autonomous CaMKII activity can be further stimulated by Ca2+/CaM. But is this biologically relevant, or are cellular substrates already maximally phosphorylated by the unstimulated autonomous activity, especially when autonomy acts over prolonged periods of time? To address this question, we examined phosphorylation of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) at Ser-19 in differentiated PC12 cells expressing various GFP-CaMKII mutants, before and after stimulation by KCl depolarization (Fig. 7A). TH is the rate-limiting step in dopamine/catecholamine biosynthesis, and phosphorylation of its Ser-19 by CaMKII enhances TH activity (36–38). Remarkably, even after expressing the constitutively autonomous CaMKII mutant T286D for 24 h, TH phosphorylation in PC12 cells was significantly further stimulated by 5 min KCl depolarization (Fig. 7, A–C). Additional T305/6D mutations (which interfere with CaM binding and thus further stimulation; supplemental Fig. S5) prevented the stimulation-induced increase in TH phosphorylation (Fig. 7C), while additional T305/6A mutations did not (Fig. 7C). Thus, substrate phosphorylation by autonomous CaMKII can also be significantly further enhanced by Ca2+/CaM within cells.

FIGURE 7.

Further stimulation of autonomous CaMKII activity toward endogenous tyrosine hydroxylase Ser-19 within PC12 cells. A and B, differentiated PC12 cells were transfected with the constitutively autonomous GFP-CaMKII T286D construct. 24 h later, total and phospho-S19 tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) was assessed by immunostaining (A). Degree of TH Ser-19 phosphorylation was further enhanced after stimulating the cells for 5 min by KCl depolarization (B). C, relative TH Ser-19 phosphorylation levels in PC12 cells, as in A and B, were quantified by the ratio of phospho-S19 to total TH staining intensity (expressed in arbitrary units), after transfection with GFP-CaMKII or various mutants at Thr-286 and/or T305/306 (n = 10 to 14). 5 min stimulation by KCl depolarization significantly increased TH phosphorylation for all conditions, including the constitutively autonomous T286D mutants (**, p < 0.05), but except for the CaM binding-deficient T305/6D mutants (N.S., p > 0.38) and the GFP control (n.s., p > 0.28; Student's t tests). Error bars indicate S.E.

The above comparison of the CaMKII mutants was based on whether or not cellular stimulation increased TH phosphorylation. It should be noted that comparison beyond that, such as direct comparison of unstimulated TH phosphorylation between the mutants, should be made carefully. Whereas all constructs with the T286D mutant had similar expression levels in the differentiated PC12 cells (and thus could compared directly with each other), this expression was ∼1/3 less than seen for wild type and T286A (supplemental Fig. S6). Thus, equal basal TH phosphorylation values together with the lower expression levels indicate stronger basal phosphorylation by the autonomous mutants, as expected. The differentiated PC12 cells expressed little endogenous CaMKII, and overexpression after transfection was ∼20-fold, as assessed by comparing anti-CaMKII immunofluorescence of transfected cells to their untransfected neighbors (supplemental Fig. S7).

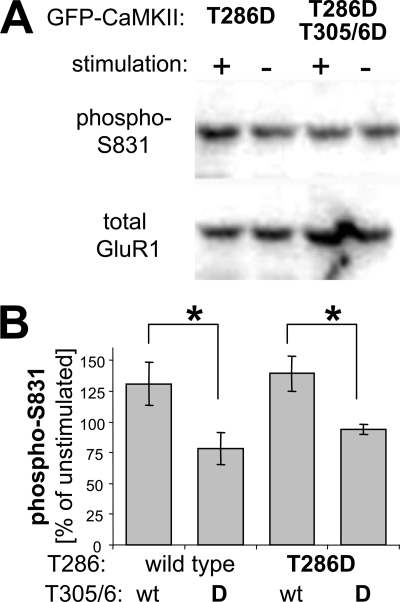

Ca2+/CaM Stimulates Phosphorylation of GluR1 Ser-831 by Autonomous CaMKII in Transfected HEK Cells

To further test Ca2+/CaM regulation of autonomous CaMKII within cells, we monitored phosphorylation of the AMPA-type glutamate receptor subunit GluR1 at Ser-831 in HEK cells (heterologous cells transfected to express both GFP-CaMKII and epitope-tagged HA-GluR1). This phosphorylation site is thought to be important in synaptic plasticity, as it enhances the single channel conductance of AMPA receptors, which is indeed observed during long term potentiation (8, 9). GluR1 Ser-831 phosphorylation was assessed by Western blot analysis using a phosphospecific antibody, before and after inducing Ca2+ signals by ionomycin treatment of the HEK cells co-transfected with constitutively autonomous GFP-CaMKII mutants (Fig. 8A). Quantification showed that the ratio of phospho-GluR1 to total GluR1 increased significantly after ionomycin treatment in cell expressing autonomous CaMKII T286D mutant, to a similar degree as in cells expressing CaMKII wild type (Fig. 8B). In cell expression T305/6D CaMKII mutants, which are impaired in Ca2+/CaM binding, no increase in GluR1 phosphorylation was observed (Fig. 8B). Thus, the increased phosphorylation was indeed due to further stimulation not only of CaMKII wild type but also of the autonomous T286D mutant.

FIGURE 8.

Further stimulation of autonomous CaMKII activity toward GluR1 Ser-831 in transfected HEK cells. A, Western blot analysis of phospho-S831 and total GluR1 from extracts of transfected HEK cells before or after a Ca2+ signal induced by ionomycin treatment (10 μm, 3 min). HEK cells were transfected to co-express exogenous HA-tagged GluR1 and GFP-CaMKII T286D (constitutively autonomous) or T286D, T305/6D (constitutively autonomous, CaM binding impaired). B, quantification of Western blot analyses as in A showed that GluR1 Ser-831 phosphorylation by both wild type and the autonomous T286D CaMKII can be similarly and significantly increased by ionomycin-induced Ca2+ signals, compared with Ca2+/CaM-impaired mutants (T305/6D), which failed to show such increase, as expected (*, p < 0.05 in Neuman-Keuls multiple comparison test, after one-way ANOVA with p < 0.05; n = 3 or 5, for wild type or T286D, respectively). Error bars indicate S.E.

DISCUSSION

Generation of CaMKII autonomy by Thr-286 autophosphorylation is a vital step in regulating synaptic plasticity and learning/memory (15) (for review see Refs. 1,2,4). This study shows that this CaMKII autonomy is substrate-dependent, and that low autonomy (15–25%) is the general default. In contrast to previous general perception, Ca2+/CaM significantly further stimulated Ca2+-independent, autonomous CaMKII activity toward regular substrates (R-substrates), both in vitro and within cells (including GluR1 Ser-831, a CaMKII site highly implicated in synaptic plasticity; Refs. 8, 9). Higher autonomy was an exception seen only for T-site binding substrates (T-substrates), including NR2B Ser-1303.

This study provided the first demonstration that low autonomy (15–25%) and further Ca2+/CaM-stimulation can be observed with a CaMKII preparation shown to be capable of high autonomy (>60%) toward other substrates under the same conditions. Importantly, this low autonomy (the ratio of autonomous over maximally stimulated phosphorylation rates) was very similar for all regular substrates, and thus did not depend on the absolute phosphorylation rates (which differed widely between the substrates, as expected). Higher autonomy observed toward AC2 required a special mechanism: T-site binding. Mutational interference with this mechanism significantly reduced autonomy, further demonstrating that low autonomy is the default. Substrate-dependent but generally low autonomy could not have been directly predicted from the literature: Whereas the reported autonomy for AC2 was generally around 50% or above, reports for autonomy toward regular substrates such as MAP2 and syntide2 included both low (∼20%) and high (>70%) values (12, 13, 26, 27). This discrepancy, together with stronger theoretical arguments, allowed the common perception that high values would likely be better estimates for autonomy toward all substrates. The results of this study now clearly demonstrate that low autonomy is not only real, but actually the general default.

Further stimulation of autonomous CaMKII significantly increased substrate phosphorylation not only in vitro, but also within cells. This observation was by no means trivial: Even 20% of full CaMKII activity could conceivably have been sufficient to produce near maximal phosphorylation of cellular substrates, especially when acting over a prolonged period of time, which is indeed the case for autonomous kinase. Obviously, the phosphorylation state of cellular substrates is determined by the equilibrium between a forward kinase reaction and the reversing action of cellular phosphatases. Our results showed that even prolonged expression of an autonomous CaMKII did not overwhelm the endogenous phosphatase system of PC12 or HEK cells, allowing a significant further shift in the equilibrium by additional cellular stimulation. Thus, low CaMKII autonomy that can be further stimulated by Ca2+/CaM does indeed prevent the uncoupling from subsequent cellular stimulation.

Low CaMKII autonomy even at high substrate concentrations (75 μm) already indicated a reduced Vmax, but further studies showed additionally an increased Km. This is consistent with our model of an inhibitory gate that is fully displaced by Ca2+/CaM stimulation, but only partially displaced by Thr-286 phosphorylation under autonomous conditions (with further displacement only by the additionally T-site binding substrate AC2, leading to substrate-specific higher autonomy). As a direct consequence of increased Km, CaMKII autonomy is additionally substrate concentration-dependent. However, autonomy was remarkably stable both at low and high substrate concentrations, with a change occurring only within a relatively narrow concentration range. It is noteworthy that the cellular concentration of virtually all soluble proteins falls into the low stable range observed here for all regular substrates (as even the concentration of G-actin is below 70 μm). Infinite virtual substrate concentration leading to the high stable range of autonomy could be mimicked within cells by optimized targeting and positioning of the kinase relative to a specific substrate. However, even then, autonomous activity can still be ∼2-fold further stimulated by Ca2+/CaM, at least for regular substrates (as a direct consequence of lower Vmax of autonomous compared with stimulated CaMKII activity).

Our study confirmed previous indications (27) that CaMKII autonomy is also dependent on the ATP concentration (a parameter thought to be stably in the mm range within live cells, and to change significantly only under pathological situations). This finding is consistent with the notion that Thr-286-phosphorylatd CaMKII is less accessible not only for substrate proteins but also for ATP when Ca2+/CaM is absent.

High autonomy was an exception seen for the T-substrates AC2 and NR2B, but not for R-substrates such as syntide-2, MAP2, tyrosine hydroxylase, or GluR1. Additional mechanisms that influence CaMKII autonomy may be identified for other specific substrates in the future. However, this study clearly demonstrates that low autonomy is the default. These findings do not diminish the demonstrated importance of CaMKII autonomy, but they reshape our understanding of this hallmark feature of CaMKII regulation. Autonomous CaMKII activity that is further regulated by Ca2+/CaM still allows for a molecular memory, but additionally prevents complete uncoupling from subsequent signaling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Leslie Krushel (University of Colorado Denver) and his laboratory for help with the Storm System.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants P30NS048154 (UCD Center Grant), R01NS040701 (to M. L. D.), and R01NS052644 (to K. U. B.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S7 and Tables S1 and S2.

- CaM

- Ca2+/calmodulin

- PIPES

- 1,4-piperazinediethanesulfonic acid

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- TH

- tyrosine hydroxylase

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Malenka R. C., Nicoll R. A. (1999) Science 285, 1870–1874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lisman J., Schulman H., Cline H. (2002) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 175–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hudmon A., Schulman H. (2002) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 473–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colbran R. J., Brown A. M. (2004) Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 14, 318–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malinow R., Schulman H., Tsien R. W. (1989) Science 245, 862–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silva A. J., Stevens C. F., Tonegawa S., Wang Y. (1992) Science 257, 201–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayashi Y., Shi S. H., Esteban J. A., Piccini A., Poncer J. C., Malinow R. (2000) Science 287, 2262–2267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benke T. A., Lüthi A., Isaac J. T., Collingridge G. L. (1998) Nature 393, 793–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derkach V., Barria A., Soderling T. R. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 3269–3274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang H., Schuman E. M. (1995) Science 267, 1658–1662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou Z., Hong E. J., Cohen S., Zhao W. N., Ho H. Y., Schmidt L., Chen W. G., Lin Y., Savner E., Griffith E. C., Hu L., Steen J. A., Weitz C. J., Greenberg M. E. (2006) Neuron 52, 255–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller S. G., Kennedy M. B. (1986) Cell 44, 861–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lou L. L., Lloyd S. J., Schulman H. (1986) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 9497–9501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schworer C. M., Colbran R. J., Soderling T. R. (1986) J. Biol. Chem. 261, 8581–8584 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giese K. P., Fedorov N. B., Filipkowski R. K., Silva A. J. (1998) Science 279, 870–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soderling T. R., Stull J. T. (2001) Chem. Rev. 101, 2341–2352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nolen B., Taylor S., Ghosh G. (2004) Mol. Cell 15, 661–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bayer K. U., De Koninck P., Leonard A. S., Hell J. W., Schulman H. (2001) Nature 411, 801–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenberg O. S., Deindl S., Sung R. J., Nairn A. C., Kuriyan J. (2005) Cell 123, 849–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanson P. I., Meyer T., Stryer L., Schulman H. (1994) Neuron 12, 943–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rich R. C., Schulman H. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 28424–28429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenberg O. S., Deindl S., Comolli L. R., Hoelz A., Downing K. H., Nairn A. C., Kuriyan J. (2006) FEBS. J. 273, 682–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Koninck P., Schulman H. (1998) Science 279, 227–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bayer K. U., De Koninck P., Schulman H. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 3590–3597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyer T., Hanson P. I., Stryer L., Schulman H. (1992) Science 256, 1199–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erickson J. R., Joiner M. L., Guan X., Kutschke W., Yang J., Oddis C. V., Bartlett R. K., Lowe J. S., O'Donnell S. E., Aykin-Burns N., Zimmerman M. C., Zimmerman K., Ham A. J., Weiss R. M., Spitz D. R., Shea M. A., Colbran R. J., Mohler P. J., Anderson M. E. (2008) Cell 133, 462–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith M. K., Colbran R. J., Brickey D. A., Soderling T. R. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 1761–1768 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang E., Schulman H. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 26199–26208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vest R. S., Davies K. D., O'Leary H., Port J. D., Bayer K. U. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 5024–5033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bayer K. U., LeBel E., McDonald G. L., O'Leary H., Schulman H., De Koninck P. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26, 1164–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Leary H., Lasda E., Bayer K. U. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 4656–4665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colbran R. J., Soderling T. R. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 11213–11219 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanson P. I., Schulman H. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 17216–17224 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu C. S., Hodge J. J., Mehren J., Sun X. X., Griffith L. C. (2003) Neuron 40, 1185–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schulman H. (1984) J. Cell Biol. 99, 11–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamauchi T., Fujisawa H. (1981) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 100, 807–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Griffith L. C., Schulman H. (1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 9542–9549 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bobrovskaya L., Dunkley P. R., Dickson P. W. (2004) J. Neurochem. 90, 857–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.