Abstract

Syntheses, molecular structures and magnetic susceptibilities of three meso-substituted high-spin iron(III) porphyrinate complexes ([Fe(TEtP)(Cl)], [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)], and [Fe(THexP)(Cl)]) are described. It was determined that the inter-ring interactions within each dimeric unit change upon alteration of the alkyl groups at the meso-positions. Magnetic exchange couplings between iron centers of the dimers are in accord with the trends in structural inter-ring geometries. Crystal data for [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)]: a = 10.1710(5) Å, b = 11.309(3) Å, c = 12.170(3) Å, α = 91.774(9) °, β = 113.170(14) °, γ = 112.149(9) °, V = 1165.2(4) Å3, triclinic, P1̄, Z = 2, R1 = 0.0844 and ωR2 = 0.2073 for observed data. Crystal data for [Fe([Fe(TPrP)(Cl)])(Cl)]: a = 13.040(2) Å, b = 15.221(2) Å, c = 14.6681(9) Å, β = 109.997(11) °, V = 2735.9(7) Å3, monoclinic, P21/n, Z = 4, R1 = 0.0477 and ωR2 = 0.1176 for observed data. Crystal data for [Fe(THexP)(Cl)]: a = 10.246(7) Å, b = 12.834(4) Å, c = 17.420(15) Å, α = 69.74(3) °, β = 87.52(4) °, γ, = 84.89(3) °, V = 2140(2) Å3, triclinic, P1̄, Z = 2, R1 = 0.1024 and ωR2 = 0.2659 for observed data.

Keywords: iron(III)meso-tetraalkylporphinates, inter-ring interaction, magnetic exchange couplings, Crystal Structures

Introduction

It is well-known that π–π interactions between two or more porphyrin molecules in close proximity are present in photosynthetic proteins, including light-harvesting chlorophyll arrays[1] and the photosynthetic reaction center special pair.[2] The interactions have played a critical role in electron(or energy)-transfer process in photosynthetic proteins. Scheidt and Lee[3] surveyed the inter-ring geometry for all structurally characterized neutral porphyrin dimers. They noted that the observed lateral shifts tend to cluster around specific values rather than displaying a continuous distribution. It has been shown that such dimerizations have a strong effect on the chemical reactivity and spectroscopic properties of the porphyrinato complexes.[4]–[6]

Studies on the replacement of meso-aryl substituents in metallotetrarylporphyrins by alkyl groups have attracted much attention recently owing to the fact that the alkyl-substituents may profoundly inuence the molecular and electronic structure as well as catalytic properties of the resulting complexes.[7]–[28] In the present work, we describe the synthesis and characterization of a series of meso-(tetraalkylporphinato)iron(III) chloride complexes. Their molecular structures indicate that inter-ring interactions change with alteration of the alkyl group substitutions in the meso positions. Also, we have investigated the effect of such inter-ring interaction on magnetic exchange interactions between the iron centers of these meso-alkyl substituted porphyrinates.

Experimental Section

General Information

Dichloromethane was distilled over potassium carbonate and hexanes were distilled over sodium benzophenone. All other chemicals were used as received from Aldrich or Fisher. meso-Tetra-n-propylporphyrin (H2TPrP) was prepared according to Neya’s method,[29] while meso-tetraethylporphyrin (H2TEtP) and meso-tetra-n-hexylporphyrin (H2THexP) was prepared according to Lindsey’s method.[30] Iron was inserted into the three H2-meso-tetraalkylporphyrinato derivatives by standard methods.[31] UV-vis spectra were recorded on a Perkin-Elmer Lambda 19 spectrometer and IR spectra on a Perkin-Elmer model 883 as KBr pellets. EPR spectra were obtained at 77 K on a Varian E-12 spectrometer operating at X-band.

Structure Determinations

Single crystals of [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)][32] and [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)] were obtained by slow di_usion of hexanes into a CH2Cl2 solution of the metalloporphyrin, whereas single crystals of [Fe(THexP)(Cl)] were obtained by slow evaporation of a concentrated CH2Cl2 solution. X-ray diffraction data for all the complexes were collected on a Nonius FAST area-detector diffractometer with a Mo rotating anode source (λ̄ = 0.71073 Å). Our detailed methods and procedure for small molecule X-ray data collection have been described previously.[33]

The structure of [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] was solved by Patterson methods, while [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)] and [Fe(THexP)(Cl)] were solved by direct methods.[34] All remaining non-hydrogen atoms were located by difference Fourier synthesis. The structures were refined against F2 using the program SHELXL-93,[35] in which all data collected were used including negative intensities. Hydrogen atoms of the porphyrin ligands and the solvent molecule were idealized with the standard SHELXL-93 idealization methods. A modified[36] version of the absorption correction program DIFABS and extinction were applied for [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)] and [Fe(THexP)(Cl)]. For [Fe(THexP)(Cl)], it was found that three hexyl substituents were disordered. One hexyl chain is disordered over two half-occupied positions (C(80) to C(85) and C(90) to C(95)). The last three carbon atoms of another hexyl group are disordered; C(4) to C(6) have refined occupancies of 0.76, while C(41) to C(61) have occupancies of 0.24. In the third disordered hexyl group, the final methyl group is disordered over two positions (C(24) and C(240)) with refined occupation factors of 0.63 and 0.37, respectively. There is one dichloromethane molecule with an occupancy factor of 0.10. Brief crystallographic data for all three complexes are listed in Table 1. Complete crystallographic details are available from the CCDC (Supporting Information).

Table 1.

Crystallographic details for [Fe(TalkylP)(Cl)] complexes.

| Molecule | [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)] | [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] | [Fe(THexP)(Cl)] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formula | C28H28ClFeN4 | C32H36ClFeN4 | C44H60ClFeN4·0.1CH2Cl2 |

| FW, amu | 511.84 | 567.95 | 744.75 |

| a, Å | 10.1710(5) | 13.040(2) | 10.246(7) |

| b, Å | 11.309(3) | 15.221(2) | 12.834(4) |

| c, Å | 12.170(3) | 14.6681(9) | 17.420(15) |

| α, deg | 91.774(9) | 90 | 69.74(3) |

| β, deg | 113.170(14) | 109.997(11) | 87.52(4) |

| γ, deg | 112.149(9) | 90 | 84.89(3) |

| V, Å3 | 1165(4) | 2735.9(7) | 2140(2) |

| Crystal system | triclinic | monoclinic | triclinic |

| Space Group | P1̄ | P21/n | P1̄ |

| Z | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Dc, g/cm3 | 1.459 | 1.379 | 1.156 |

| F(000) | 534 | 1196 | 790 |

| μ, mm−1 | 0.787 | 0.678 | 0.448 |

| Radiation (λ̄, Å) | MoKα (0.71073) | MoKα (0.71073) | MoKα (0.71073) |

| Temperature, K | 130(2) | 130(2) | 130(2) |

| R indices [I > 2σ(I)] |

R1 = 0.0884, wR2 = 0.2073 |

R1 = 0.0477, wR2 = 0.1176 |

R1 = 0.1024, wR2 = 0.2659 |

| R indices (all data) |

R1 = 0.1060, wR2 = 0.2254 |

R1 = 0.0556, wR2 = 0.1235 |

R1 = 0.1647, wR2 = 0.3239 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.055 | 1.052 | 1.026 |

Magnetic Susceptibility Measurements

Magnetic susceptibility measurements were obtained on ground samples (immobilized in Dow Corning silicone grease) in the solid state over the temperature range 6–300 K on a Quantum Design MPMS SQUID susceptometer. Measurements at two fields (2 and 20 kG) showed that no ferromagnetic impurities were present and that preferential orientation of unpaired spins was not taking place. χM was corrected for the underlying porphyrin ligand diamagnetism according to previous experimentally observed values;[38] all remaining diamagnetic contributions (χdia) were calculated using Pascal’s constants.[39];[40] All measurements included a correction for the diamagnetic sample holder and the diamagnetic silicone grease.

Results

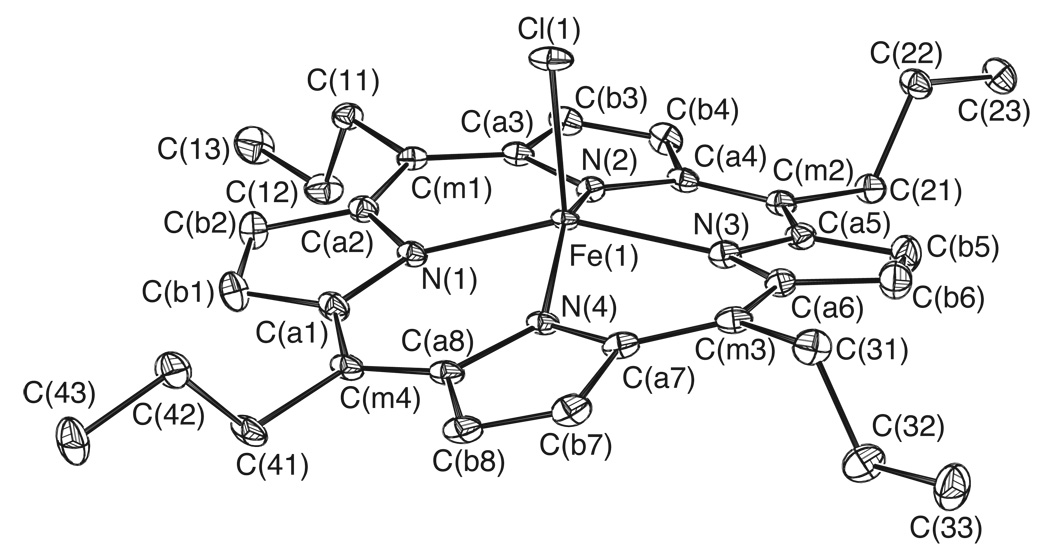

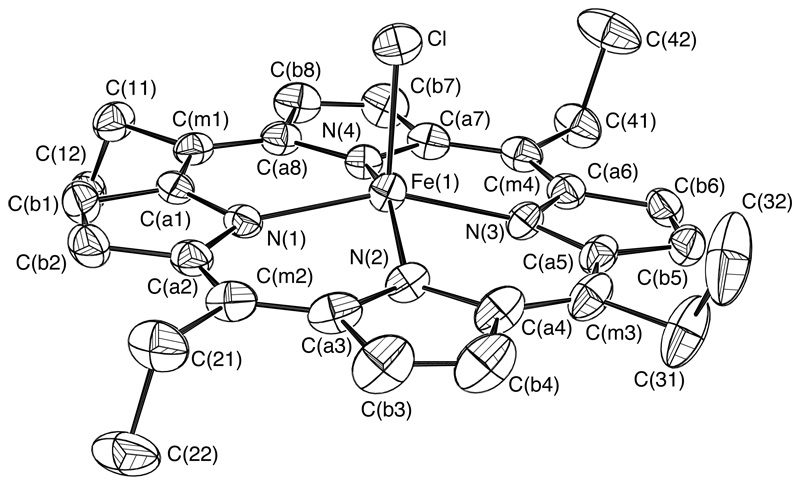

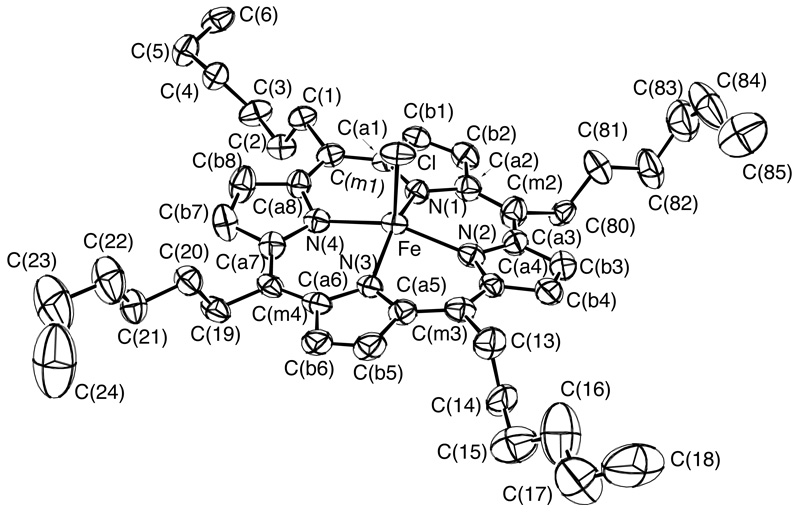

The molecular structures of three meso alkyl-substituted (chloro)iron(III) porphyrinate derivatives have been determined. The three iron porphyrin complexes differ in the length of the alkyl side chains with meso-substituents of ethyl, [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)], n-propyl, [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)], and n-hexyl, [Fe(THexP)(Cl)]. A labeled ORTEP diagram of [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] is shown in Figure 1. Labeled ORTEP diagrams of [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)] and [Fe(THexP)(Cl)] can be found in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Table 1 details selected crystallographic details for all three complexes.

Figure 1.

ORTEP diagram of [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)]. Ellipsoids are drawn to illustrate 50% probability surfaces. Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity.

Figure 2.

ORTEP diagram of [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)]. Ellipsoids are drawn to illustrate 50% probability surfaces. Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity.

Figure 3.

ORTEP diagram of [Fe(THexP)(Cl)]. Ellipsoids are drawn to illustrate 50% probability surfaces. Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity.

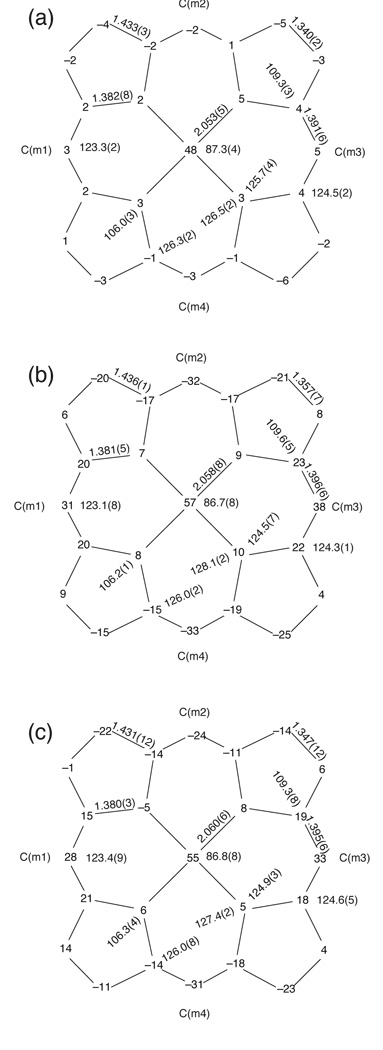

Bond distances and bond angles around the iron(III) atom in the three derivatives are listed in Table 2. Figure 4a–c presents formal diagrams of the porphinato cores in [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)], [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)], and [Fe(THexP)(Cl)], respectively, displaying the perpendicular displacements of each atom from the 24-atom mean plane of the porphinato core. Figure 4 also contains the average bond lengths and bond angles (including standard deviations) for each complex. The porphyrin core of [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)] (Figure 4a) is planar, while the porphyrin cores of [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] and [Fe(THexP)(Cl)] are S4– ruffled (Figures 4b and 4c).

Table 2.

Select bond distance(Å) and angles(°) for [Fe(TalkylP)(Cl)] complexes.

| [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)] | [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] | [Fe(THexP)(Cl)] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Bond Lengths (Å) | |||

| Fe(1)–N(1) | 2.060(3) | 2.063(1) | 2.068(4) |

| Fe(1)–N(2) | 2.052(3) | 2.054(1) | 2.063(5) |

| Fe(1)–N(3) | 2.048(3) | 2.055(1) | 2.056(4) |

| Fe(1)–N(4) | 2.051(3) | 2.062(1) | 2.054(5) |

| Fe(1)–Cl | 2.2644(13) | 2.2332(6) | 2.2375(18) |

| B. Bond Angles (deg) | |||

| N(1)–Fe(1)–N(2) | 86.66(14) | 86.30(6) | 87.32(17) |

| N(1)–Fe(1)–N(4) | 87.54(14) | 86.88(6) | 86.31(17) |

| N(2)–Fe(1)–N(3) | 87.49(14) | 87.16(6) | 86.41(17) |

| N(3)–Fe(1)–N(4) | 87.45(14) | 86.50(6) | 87.23(18) |

| N(1)–Fe(1)–N(3) | 154.47(14) | 152.24(6) | 152.14(17) |

| N(2)–Fe(1)–N(4) | 155.21(14) | 152.31(6) | 153.32(17) |

Figure 4.

Formal 24-atom mean-plane diagrams of (a) [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)], (b) [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)], and (c) [Fe(THexP)(Cl)]. The displacement of each atom from the 24-atom mean plane of the core is given in units of 0.01 Å. Also displayed are the averaged values of each type of bond distance and angle in the core. The number in parentheses is the standard deviation calculated on the assumption that all averaged values were drawn from the same population.

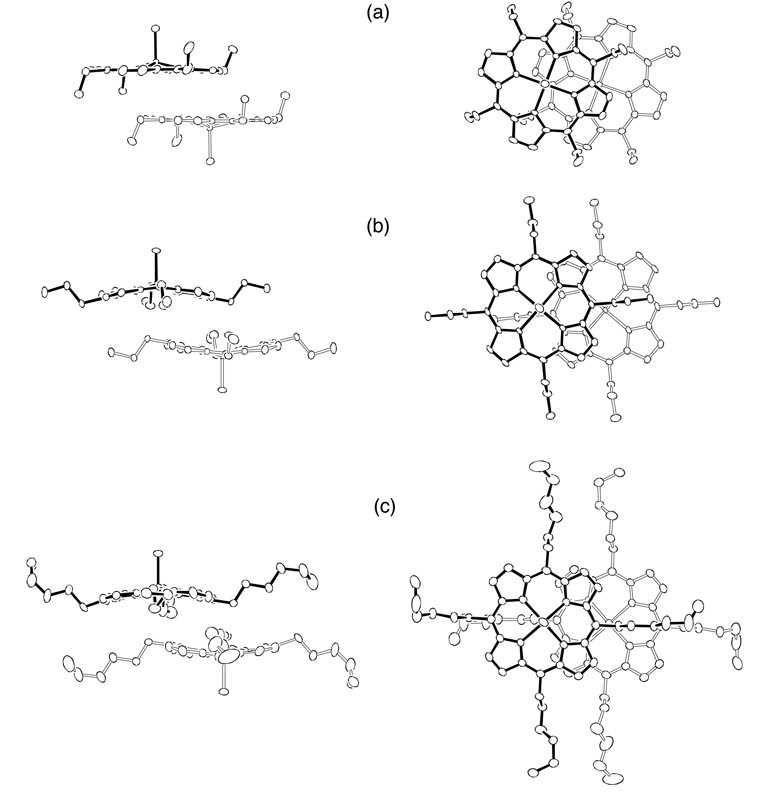

Solid-state π–π dimer formation is seen in all three [Fe(TalkylP)(Cl)] complexes. Figure 5a–c shows edge-views and top-views of the closest interacting pair of porphyrin dimers for [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)], [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)], and [Fe(THexP)(Cl)], respectively. The inter-ring geometries for each dimer, including Fe…Fe and Ct…Ct distances, lateral shifts (L.S.), and mean plane separations (M.P.S.), are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 5.

Edge-views and top-views of the dimeric units of (a) [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)], (b) [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)], and (c) [Fe(THexP)(Cl)]. Ellipsoids are drawn to illustrate 30% probability surfaces for [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)], 65% probability surfaces for [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)], and 30% probability surfaces for [Fe(THexP)(Cl)].

Table 3.

Summary of inter-ring geometries for [Fe(TalkylP)(Cl)] complexes.a

| Complex | Fe⋯Fe | Ct⋯Ctb | M.P.S.c | L.S.d | Group | Δe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)] | 5.56 | 5.04 | 3.34 | 3.79 | I | 0.48 |

| [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] | 6.44 | 5.64 | 3.66 | 4.29 | W | 0.57 |

| [Fe(THexP)(Cl)] | 6.36 | 5.77 | 3.64 | 4.48 | W | 0.55 |

Values in Å.

Ct is the center of the 24-atom porphyrin ring.

The average mean plane separation for the two 24-atom cores of the dimer.

The lateral shift between the two 24-atom cores of the dimer.

The out-of-plane displacement relative to the 24-atom mean plane.

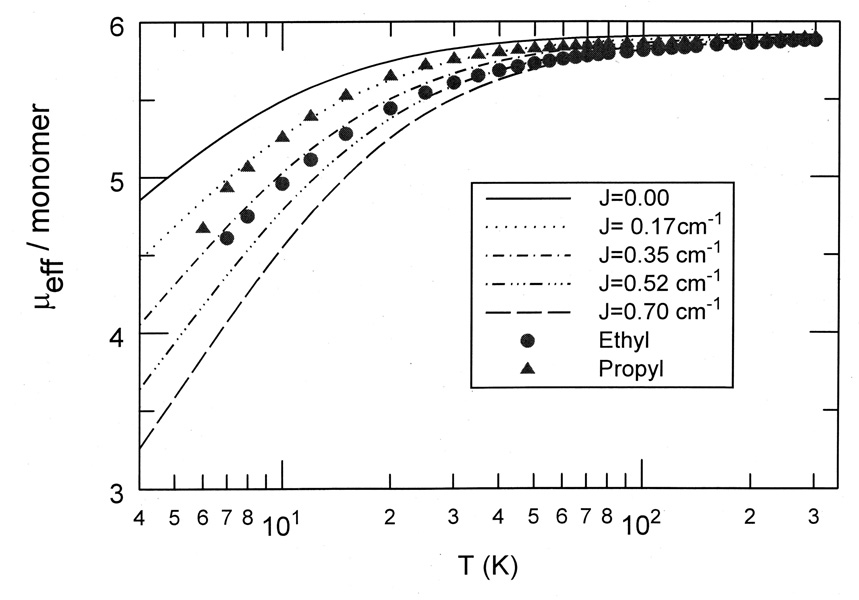

Temperature-dependent magnetic susceptibility measurements were carried out on the [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)] and [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] complexes over the temperature range 6–300 K. Figure 6 shows the temperature-dependent magnetic moments for both complexes.

Figure 6.

Comparison of observed and calculated values of µeff/monomer vs T for (a) [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)] and (b) [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)]. The solid lines are model calculation with the parameters–axial zero-field splitting D = 6.95 cm−1, antiferromagnetic coupling with J = +0.45 for (a) and J = +0.17 cm−1 for (b).

Discussion

Crystal Structures

The general trends in bond lengths and bond angles for all three [Fe(TalkylP)(Cl)] complexes are similar to those found in [Fe(TPP)(Cl)][41] and [Fe(OEP)(Cl)].[42] The coordination geometry of the iron centers in the [Fe(TalkylP)(Cl)] complexes is characteristic of high-spin iron(III) porphyrins. The equatorial Fe–Np bond lengths in [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)], [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)], and [Fe(THexP)(Cl)] (2.053(5) Å, 2.058(8) Å, and 2.060(6) Å, respectively) fit nicely into the category of typical high-spin Fe–N distances (≥ 2.045 Å).[43] A close inspection of bond angles reveals significant differences in the Fe–N–C(a) angles when comparing [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)] to [Fe([Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] and [Fe(THexP)(Cl)] (Figure 4). In [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)], the two types of Fe–N–C(a) angles are nearly equivalent [126.5(2) ° and 125.7(4) °] and are similar to those found in [Fe(TPP)(Cl)][41] [126.9(8) ° and 125.8(6) °] and [Fe(OEP)(Cl)][42] [126.3(6) ° and 126.5(5)°]. In contrast, [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] and [Fe(THexP)(Cl)] have two distinct types of Fe–N–C(a) angles with one of the angles being larger than the other [128.1(2) ° and 124.5(7) ° for [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] and 127.4(2) ° and 124.9(3)° for [Fe(THexP)(Cl)]]. The differences in Fe–N–C(a) angles are apparently the result of the change in macrocyclic conformations among these complexes. In [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)], the macrocycle is basically planar, as evidenced by an average deviation of the macrocycle carbon atoms from the 24-atom mean plane of 0.03 Å, and a maximum displacement of 0.06 Å (Figure 4a). The macrocycles of [Fe(TPrP(Cl)] and [Fe(THexP)(Cl)] are ruffled to reduce steric interactions between the meso-alkyl and neighboring pyrrole groups. The average and maximum deviations of the macrocycle carbon atoms from the 24-atom mean plane of [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] and [Fe(THexP)(Cl)] are 0.18 Å and 0.38 Å, and 0.15 Å and 0.33Å, respectively. Thus, ruffling of the macrocycles of [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] and [Fe(THexP)(Cl)] contributes to the significant differences in Fe–N–C(a) angles found in these two complexes. The effects of ring ruffling are also reflected in the coordination environment of the iron centers; the out-of-plane displacement of the Fe atom in planar [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)] (0.48 Å) is slightly smaller than those found in ruffled [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] and [Fe(THexP)(Cl)] (0.57 Å and 0.55 Å, respectively). Additionally, compared to planar [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)], an increase of the Fe–Np distances accompanied by a decrease of the Fe–Cl bond lengths is observed in ruffled [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] and [Fe(THexP)(Cl)] (see Table 2).

In addition to the differences in ring conformations, the inter-ring interactions among the [Fe(TalkylP)(Cl)] dimers are dramatically different. The lateral shift values increase from ethyl to hexyl groups (Table 3). The lateral shift of [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)] is 3.79 Å, which falls into the intermediate (I) group, as defined by Scheidt and Lee,[3] whereas the dimeric units of [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] and [Fe(THexP)(Cl)] show weaker interactions (Group W) with larger lateral shifts (4.29Å and 4.48 Å, respectively). The differences in lateral shifts among these complexes can be attributed to the orientation of the meso-substituents of the porphyrin rings. Each porphyrin in [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)] has two ethyl groups pointing up and two pointing down in an orientation as to favor inter-ring overlap. However, [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] and [Fe(THexP)(Cl)] have alternating up and down meso-substituents which leads to less favorable inter-ring overlap.

Magnetic Susceptibility Measurements

Temperature-dependent magnetic susceptibility measurements were carried out on [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)] and [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] to investigate the differences in magnetic exchange between the high-spin iron(III) metal centers of these porphyrinate dimers. To date, high-spin ferric porphyrin complexes have been thoroughly investigated by using physical techniques such as EPR, Mössbauer, and NMR; however, relatively few detailed and accurate magnetic susceptibility measurements of high-spin mononuclear iron(III) porphyrins have been carried out over a wide range of temperatures. For example, magnetization studies of ferric tetraphenylporphyrins were carried out at field strengths of up to 50 kG but were only studied between a narrow temperature range (2–20 K).[44] Original magnetic susceptibility data for [Fe(OEP)(Cl)][42] were reported at only a few temperatures and showed large scatter; recently, more accurate data for this compound has been reported from 4–100 K.[46] Although it is the lower temperature region that is most informative concerning the magnitude of the magnetic exchange interaction, large temperature ranges are helpful in determining a model that more thoroughly describes the magnetochemistry of the complex.

The temperature-dependent magnetic susceptibility plot (6–300 K) for [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] (Figure 6) is characteristic of a high-spin iron(III) complex; the room temperature µeff value of 5.90 corresponds with the spin-only moment for a S = 5/2 center, and the zero-field splitting parameter (6.95 cm−1) is typical for this class of compounds.[47] The coupling constant derived from _tting the magnetic data for [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] implies that there is an antiferromagnetic magnetic exchange interaction JS⃗1 · S⃗2 between iron centers of J = +0.17 cm−1. The temperature-dependent magnetic susceptibility plot for [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)] shows similar high-spin iron(III) characteristics (assuming a zero-field splitting parameter identical to that found in the [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] case), but is best described as having a magnetic exchange coupling constant about two times as large as that found in [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)].

As can be seen in Table 3, there is a relatively large difference between the intermolecular geometric parameters of [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] and [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)]. Most importantly, the Fe…Fe separation in [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)] (5.60 Å) is much smaller than that found in [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] (6.44 Å). Also, as can be seen in Figures 5a and 5b, the porphyrin overlap pattern is different for these two complexes. Thus, there is apparently a correlation between proximity of the iron centers of the dimeric unit and magnitude of magnetic exchange for these two complexes; stronger magnetic interaction between the iron centers of [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)] is most likely due to the closer proximity of the magnetic centers within the dimeric unit.

Thus, magnetic exchange coupling is found to be sensitive to modest structural changes between porphyrin dimer geometries, and this exchange interaction must be included in any detailed analysis of the data. In fact, it was reported that, in [Fe(OEP)(2-MeHIm)]ClO4,[45] consideration of this antiferromagnetic interaction was needed for a good fit with the experimental data. Similarly, a small but significant antiferromagnetic exchange between iron centers has been noted in [Fe(TPP)(Cl)] (J = +0.14 cm−1),[46] [Fe(OEP)(Cl)] (J = +0.02 cm−1),[46] and hemin chloride (J = +0.08 cm−1).[47] It should be noted that these coupling parameters are determined assuming a mean field model J< S⃗ > · S⃗ rather than a dimer-only coupling scheme JS⃗1 · S⃗2, thus care must be taken in comparing the coupling strengths.

Summary

We have prepared a series of meso-(tetraalkylporphinato)iron chloride complexes (alkyl = ethyl, n-propyl and n-hexyl). Their molecular structures indicate that inter-ring interactions change with alteration of the alkyl group substitutions in the meso positions. Magnetic exchange couplings between iron centers of the dimers are in accord with the trends in structural inter-ring geometries.

Supplementary Material

Table 4.

Summary of inter-ring coupling for various iron dimers.a

| Complex | Fe⋯Fe | M.P.S.b | L.S.c | J, cm−1 | ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Fe(TPP)(B11CH12)]·C7H8 | 5.49 | 3.83 | 3.67 | +3.0 | d |

| [Fe(OEP)(2-MeHIm)]ClO4·CH2Br2 | 4.28 | 3.31 | 1.49 | +0.85 | e |

| [Fe(OEP)(2-MeHIm)]ClO4·CHCl3 | 4.60 | 3.42 | 2.15 | +0.8 | e |

| [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)] | 5.56 | 3.34 | 3.79 | +0.45 | this work |

| [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] | 6.44 | 3.66 | 4.29 | +0.17 | this work |

Values in Å.

The average mean plane separation for the two 24-atom cores of the dimer.

The lateral shift between the two 24-atom cores of the dimer.

Inorg. Chem. 1987, 26, 3022–3030. Sign adjusted to +JS⃗1 · S⃗2

J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 83, 5945–5952. Sign adjusted to +JS⃗1 · S⃗2

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health for support of this research under Grant GM-38401 to WRS. Funds for the purchase of the FAST area detector diffractometer was provided through NIH Grant RR-06709 to the University of Notre Dame. We also thank the National Science Foundation for the purchase of the SQUID equipment under Grant DMR-9703732.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. The CIF files for the crystal structures were deposited at the CCDC. The CCDC deposition numbers of [Fe(TEtP)(Cl)], [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)], and [Fe(THexP)(Cl)] are 744649, 744651 and 744650, respectively. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

References

- 1.a) Kuhlbrant W, Wang DN, Fujiyoshi Y. Nature (London) 1994;367:614–621. doi: 10.1038/367614a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) McDermott G, Prince SM, Freer AA, Hawthorn-Thwaite-Lawless AM, Papiz MZ, Cogdell RJ, Isaacs NW. Nature (London) 1995;374:517–521. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deisenhofer J, Norris JR, editors. The Photosynthetic Reaction Center. Vol. 2. New York: Academic Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheidt WR, Lee YJ. Struct. Bonding (Berlin) 1987;64:1–70. [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Scheidt WR, Geiger DK, Lee YJ, Reed CA, Lang G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;107:5693–5699. [Google Scholar]; b) Chen B, Safo MK, Orosz RD, Reed CA, Debrunner PC, Scheidt WR. Inorg. Chem. 1994;33:1319–1324. [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Scheidt WR, Cheng B, Haller KJ, Mislankar A, Rae AD, Reddy KV, Song H, Orosz RD, Reed CA, Cukiernik F, Marchon JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:1181–1183. [Google Scholar]; b) Scheidt WR, Brancato-Buentello KE, Song H, Reddy V, Cheng B. Inorg. Chem. 1996;35:7500–7507. [Google Scholar]; c) Brancato-Buentello KE, Kang SJ, Scheidt WR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:2839–2846. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brancato-Buentello KE, Scheidt WR. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1997;36:1456–1459. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song Y, Haddad RE, Jia S-L, Hok S, Olmstead MM, Nurco DJ, Schore NE, Zhang J, Ma J-G, Smith KM, Gazeau S, Pécaut J, Marchon J-C, Medforth CJ, Shelnutt JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:1179–1192. doi: 10.1021/ja045309n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haddad RE, Gazeau S, Pécaut J, Marchon J-C, Medforth CJ, Shelnutt JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:1253–1268. doi: 10.1021/ja0280933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikeue T, Ohgo Y, Nakamura M. Chem. Commun. 2003:220–221. doi: 10.1039/b210229c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikeue T, Ohgo Y, Saitoh T, Yamaguchi T, Nakamura M. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:3423–3434. doi: 10.1021/ic001412b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikeue T, Ohgo Y, Uchida A, Nakamura M, Fujii H, Yokoyama M. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:1276–1281. doi: 10.1021/ic981184+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura M, Ikeue T, Fujii H, Yoshimura T, Tajima K. Inorg. Chem. 1998;37:2405–2414. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakamura M, Ikeue T, Fujii H, Yoshimura T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:6284–6291. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikeue T, Ohgo Y, Saitoh T, Nakamura M, Fujii H, Yokoyama M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:4046–4076. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ema T, Senge MO, Nelson NY, Ogoshi H, Smith KM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1994;33:1879–1881. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallucci JC, Swepston PN, Ibers JA. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B. 1982;38:2134–2139. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kutzler FW, Swepston PN, Yellin ZB, Ellis DE, Ibers JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:2996–3004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newcomb TP, Godfrey MR, Hoffman BM, Ibers JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:7078–7084. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jentzen W, Turowska-Tyrk I, Scheidt WR, Shelnutt JA. Abstract of 210th ACS National Meeting; Inorganic Division, 531; 1995. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakamura M, Ikeue T, Fujii H, Yoshimura T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:6284–6291. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamura M, Ikeue T, Fujii H, Yoshimura T, Tajima K. Inorg. Chem. 1998;37:2405–2414. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolowiec S, Latos-Grazynski L, Toronto D, Marchon JC. Inorg. Chem. 1998;37:724–732. doi: 10.1021/ic9802707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Senge MO, Medforth CJ, Forsyth TP, Lee DA, Olmstead MM, Jentzen W, Pandey RK, Shelnutt JA, Smith KM. Inorg. Chem. 1997;36:1149–1163. doi: 10.1021/ic961156w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meot-Ner M, Adler AD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975;97:5107–5111. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song XZ, Jentzen W, Jia SL, Jaquinod L, Nurco DJ, Medforth CJ, Smith KM, Shelnutt JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:12975–12988. [Google Scholar]

- 26.DiMagno SG, Wersching AK, Ross ICR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:8279–8280. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazzanti M, Marchon J-C, Shang M, Scheidt WR, Jia S, Shelnutt JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:12400–12401. [Google Scholar]

- 28.DiMagno SG, Williams RA, Therien MJ. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:6943–6948. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neya S, Funasaki N. J. Heterocyclic Chem. 1997;34:689–690. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindsey JS, Schreiman IC, Hsu HC, Kearney PC, Marguerettaz AM. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:827–836. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adler AD, Longo FR, Kampas F, Kim J. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1970;32:2443–2445. [Google Scholar]

- 32.The structure of [Fe(TPrP)(Cl)] has been reported earlier. The structure was determined at 298 K, with temperature effects considered, there are no significant differences. Ohgo Y, Ikeue T, Nakamura M. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C. 1999;C55:1817–1819. doi: 10.1107/s0108270101009842.

- 33.Scheidt WR, Turowska-Tyrk I. Inorg. Chem. 1994;33:1314–1318. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheldrick GM. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A. 1990;A46:467–473. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheldrick GM. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A. 2008;A64:112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.The process is based on an adaptation of the DIFABS[37] logic to area detector geometry by Karaulov: Karaulov, A. I. Cardiff CF1 3TB, UK: School of Chemistry and Applied Chemistry, University of Wales, College of Cardiff; personal communication. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walker NP, Stuart D. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A. 1983;A39:158–166. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sutter TPG, Hambright P, Thorpe AN, Quoc N. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1992;195:131–132. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Selwood PW. Magnetochemistry. New York: Interscience; 1956. Chapter 2. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Earnshaw A. Introduction to Magnetochemistry. London: Academic; 1968. Chapter 1. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scheidt WR, Finnegan M. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C. 1989;C45:1214–1216. doi: 10.1107/s0108270189000715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ernst J, Subramanian J, Fuhrhop J-HZ. Naturforsch. 1977;32A:1129–1136. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scheidt WR, Reed CA. Chem. Rev. 1981;81:543–555. [Google Scholar]

- 44.a) Behere DV, Date SK, Mitra S. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1979;68:544–548. [Google Scholar]; b) Behere DV, Mitra S. Indian J. Chem. 1980;19(A):505–507. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gupta GP, Lang G, Scheidt WR, Geiger DK, Reed CA. J. Chem. Phys. 1985;83:5945–5952. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marathe VR, Mitra S. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;78:915–920. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richards PL, Caughey WS, Ebersacher H, Feher G, Malley MM. J. Chem. Phys. 1967;47:1187–1888. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.