Abstract

Observational clinical and ex vivo studies have established a strong association between atrial fibrillation and inflammation1. However, whether inflammation is the cause or the consequence of atrial fibrillation and which specific inflammatory mediators may increase the atria's susceptibility to fibrillation remain elusive. Here we provide experimental and clinical evidence for the mechanistic involvement of myeloperoxidase (MPO), a heme enzyme abundantly expressed by neutrophils, in the pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation. MPO-deficient mice pretreated with angiotensin II (AngII) to provoke leukocyte activation showed lower atrial tissue abundance of the MPO product 3-chlorotyrosine, reduced activity of matrix metalloproteinases and blunted atrial fibrosis as compared to wild-type mice. Upon right atrial electrophysiological stimulation, MPO-deficient mice were protected from atrial fibrillation, which was reversed when MPO was restored. Humans with atrial fibrillation had higher plasma concentrations of MPO and a larger MPO burden in right atrial tissue as compared to individuals devoid of atrial fibrillation. In the atria, MPO colocalized with markedly increased formation of 3-chlorotyrosine. Our data demonstrate that MPO is a crucial prerequisite for structural remodeling of the myocardium, leading to an increased vulnerability to atrial fibrillation.

Atrial fibrillation remains the most common arrhythmia in humans and stands out as a major contributor to morbidity and mortality2–4. Despite recent advances in pharmacological and invasive strategies to treat atrial fibrillation, the underlying pathophysiology remains incompletely understood. Past attempts to elucidate the pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation mainly focused on the electrical substrate, with an increasing number of studies now suggesting that atrial fibrillation shows the pathophysiological characteristics of an inflammatory disease1. Clinical investigations have reported multiple associations between vulnerability to atrial fibrillation and circulating levels of cytokines, C-reactive protein, complement5–7 and, in particular, the activation state of leukocytes8–10. Whether this inflammatory phenotype represents an epiphenomenon in atrial fibrillation or is causally linked to the initiation and progression of atrial fibrillation remains unclear.

A key mechanistic link by which inflammation may contribute to atrial fibrillation seems to be atrial fibrosis. Increased deposition and turnover of matrix proteins within the atria is accelerated in atrial myocytes after challenge with cytokines, C-reactive protein and complement1. Key effectors of extracellular matrix (ECM) turnover are matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), enzymes that have been strongly linked to ECM remodeling in atrial fibrillation11. Notably, the activity of MMPs is regulated by redox reactions. Recent reports suggest that the leukocyte-derived heme enzyme MPO, by generating hypochlorous acid (HOCl), is a crucial regulatory switch modulating MMP activity12,13. Given the ability of MPO to leave the circulation by avidly binding to and transcytosing endothelial cells14, we investigated the role of MPO in the initiation and perpetuation of atrial fibrillation and its contribution to structural changes in the heart, including atrial fibrosis.

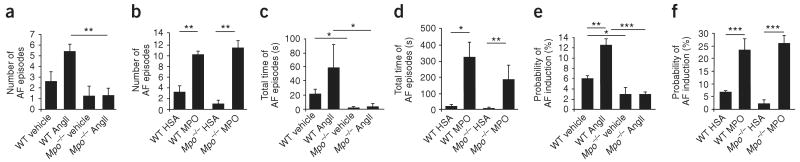

To elucidate the role of MPO in structural remodeling of the atria, we performed histological and liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS)-based studies of the atria from MPO-deficient mice (Mpo−/−) and C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) mice. In WT mice, a 2-week subcutaneous infusion of AngII, an effector of atrial remodeling and fibrosis15–18, substantially increased circulating MPO plasma concentrations and elevated myocardial deposition of MPO (Fig. 1a,b). Picrosirius red staining revealed marked attenuation of atrial fibrosis in AngII–treated Mpo−/− mice compared to AngII–treated WT mice (Fig. 1c,d). In support of the concept that atrial fibrosis depends on MPO, administration of recombinant MPO (intravenously via osmotic pumps) to Mpo−/− mice led to the development of a similar degree of atrial fibrosis as that observed for AngII- or MPO-infused WT mice. This finding reveals that atrial fibrosis developed independently of AngII administration indicating that MPO, once present in the tissue, does not require AngII as a cofactor (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b). To further characterize the molecular basis of MPO-dependent atrial remodeling, we determined atrial MMP-2 and MMP-9 enzymatic activities. These activities were both profoundly reduced in AngII–treated Mpo−/− mice, as assessed by zymography and by immunoblot analysis of MMP-9 (Fig. 1e,f). Given that MMPs are known to be activated by HOCl, we determined atrial tissue amounts of 3-chlorotyrosine, a specific footprint of MPO-dependent HOCl formation. Mass spectrometry–based quantitative analysis and immunohistochemical studies both showed markedly less formation of 3-chlorotyrosine in Mpo−/− mice after AngII treatment (Fig. 1g,h), indicating lower HOCl bioavailability in these mice.

Figure 1.

Mpo−/− mice show less atrial fibrosis, reduced matrix metalloproteinase activity and lower chlorotyrosine bioavailability after AngII treatment. (a,b) MPO plasma concentrations (a) and myocardial MPO deposition (b) in saline (vehicle)- or AngII-treated WT and Mpo−/− mice, as determined by ELISA. n = 14–19, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. (c) Quantification of atrial fibrosis in Mpo−/− and WT mice by the picrosirius polarization method. Images are representative of ten images from eight to ten mice per group. LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle. (d) Quantitative assessment of atrial fibrosis in saline– or AngII-treated WT and Mpo−/− mice. n = 8–12, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (e) MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity in AngII-treated WT and Mpo−/− mice determined by zymography. n = 7, **P < 0.01. (f) Immunoblot detecting pro–MMP-9 and MMP-9 in mouse atrial tissue. n = 4, P < 0.05 for WT AngII versus Mpo−/− AngII. (g) LC-MS–based quantitative assessment of 3-chlorotyrosine (Cl−Tyr) in atrial tissue of WT and Mpo−/− mice. n = 10, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. (h) Immunostaining of atrial 3-chlorotyrosine in saline– or AngII-treated WT and Mpo−/− mice. All data in b, d–g are means ± s.d. Statistical analyses were performed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test. Data in a are presented as median and interquartile range. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Mann-Whitney U post hoc test was used for statistical analysis.

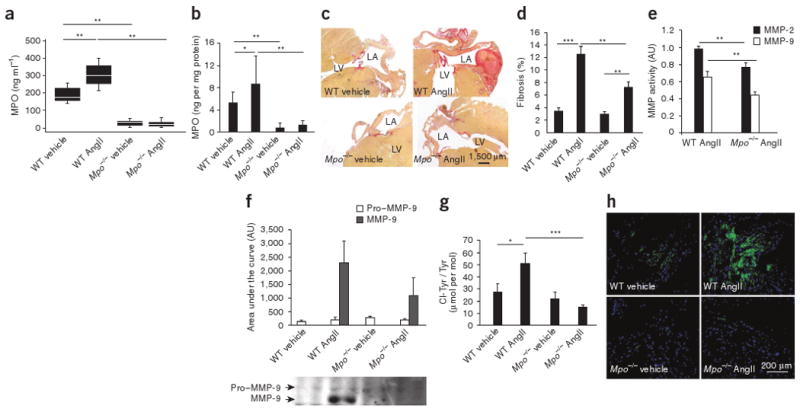

To test whether MPO-dependent structural remodeling also translated into increased electrical instability and thus higher vulnerability for the development of atrial fibrillation, we subjected Mpo−/− and WT mice to electrophysiological investigation in vivo19 (Fig. 2). Upon right atrial electrophysiological stimulation, WT mice challenged with AngII showed a higher susceptibility to atrial fibrillation compared to vehicle-treated WT mice, with a higher number and duration of atrial fibrillation episodes, as well as an increased probability of atrial fibrillation induction (Fig. 2a,c,e). In sharp contrast, AngII treatment did not affect the inducibility of atrial fibrillation in Mpo−/− mice, indicating an almost complete protection from atrial fibrillation in Mpo−/− mice (Fig. 2a,c,e). However, continuous intravenous supplementation of recombinant MPO via minipumps reestablished the vulnerability to atrial fibrillation in Mpo−/− mice (Fig. 2a–f); this effect was dose dependent and occurred in the absence of AngII administration (Supplementary Fig. 2). These results indicate that MPO, upon intravenous infusion and thus independently of leukocytes, and independently of AngII, can promote electrical instability in the atria. This suggests that MPO not only is a marker of leukocyte activation but also is mechanistically involved in the induction of atrial fibrillation, whereas AngII seems to unfold its proarrhythmic properties in large part by activation of leukocytes.

Figure 2.

Analysis of atrial fibrillation inducibility in Mpo−/− and WT mice in vivo. (a–d) After pretreatment with AngII or saline (vehicle) for 14 d (n = 10–16 per group) (a,c) or MPO or human serum albumin (HSA) for 7 d (n = 6–9 per group) (b,d), WT and Mpo−/− mice underwent electrophysiological investigation. (a,b) Quantification of the number of atrial fibrillation (AF) episodes. **P < 0.01. (c,d) Total time of atrial fibrillation episodes. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. (e,f) Probability of induction of atrial fibrillation, defined as inducible episodes divided by number of total testing maneuvers applied. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. All data are means ± s.d. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test.

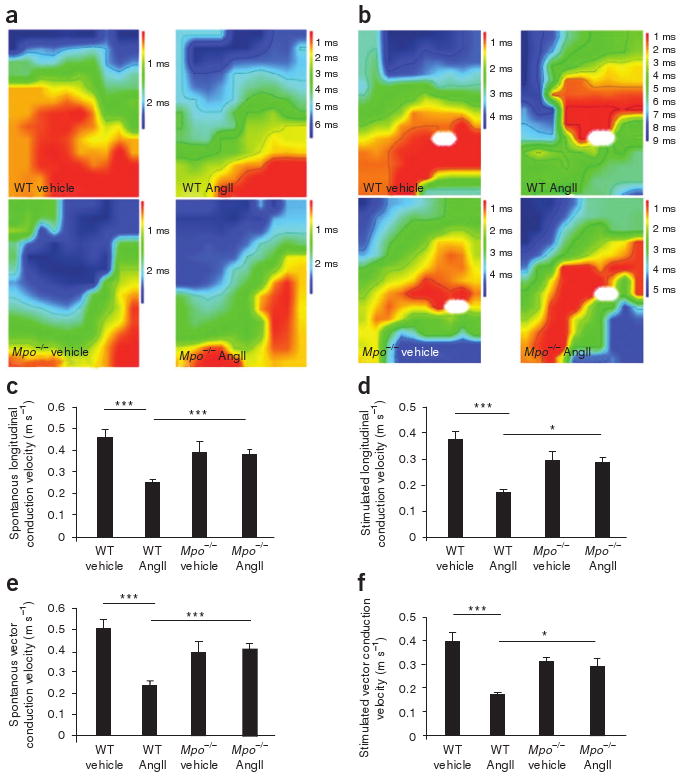

To further evaluate whether MPO-dependent atrial fibrosis increases atrial conduction inhomogeneity, an electrophysiological hallmark of atrial fibrillation20, we performed epicardial activation mapping in Langendorff-perfused hearts from WT and Mpo−/− mice21. Atria from AngII-treated Mpo−/− mice, in sharp contrast to atria from AngII-challenged WT mice, showed no retardation in conduction velocity (Fig. 3a–f); this finding complements the histological observations of attenuated atrial fibrosis in AngII-treated Mpo−/− mice. Accordingly, in vivo surface electrocardiogram tracings showed a significant prolongation of P wave duration in WT mice upon AngII treatment (P < 0.001, Supplementary Table 1) as opposed to AngII-treated Mpo−/− mice. Studies in isolated atrial cardiomyocytes showed that cell capacity, resting membrane potential and the overshoot and duration of the action potential did not differ between WT and Mpo−/− mice, thus excluding a major impact of MPO deficiency on the electrophysiology of atrial cells (Supplementary Fig. 3a–d). In addition, plasma potassium concentrations, a key covariate for the electrical stability of the atria, were similar across the four treatment groups (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Epicardial mapping of Langendorff-perfused hearts of AngII- or saline (vehicle)-treated WT or Mpo−/− mice. (a,b) Representative examples of spontaneous (a) and stimulated (b) conduction properties of epicardial activation mapping. White ovals indicate stimulation sites. (c–f) Quantification of spontaneous longitudinal conduction velocity (c), stimulated longitudinal conduction velocity (d), spontaneous vector conduction velocity (e) and stimulated vector conduction velocity (f). n = 5–13 per group, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. All data are means ± s.d. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA with Bonferroni's post hoc test.

Given the well-documented effects of AngII on blood pressure, the cytokine-like, leukocyte-activating properties of AngII22 and the established nitric oxide–consuming properties of MPO23,24, we assessed hemodynamics in AngII-treated WT and MPO-deficient mice by in vivo radiotelemetric blood pressure measurements. Whereas baseline blood pressure was not different between groups (Supplementary Fig. 4a), the blood pressure–elevating effect of AngII in WT mice was blunted in Mpo−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Conversely, blood pressure in Mpo−/− mice reconstituted with MPO in the absence of AngII remained unaltered as compared to vehicle-treated mice (Supplementary Fig. 5a,b), indicating that MPO-dependent effects on vascular tone and on structural atrial remodeling are differentially regulated. Echocardiographic studies revealed no changes in atrial diameters across groups (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Taken together, these observations reinforce the idea that electrical instability evoked by MPO does not simply reflect changes in systemic vasomotion and atrial dimensions but is functionally linked to structural transformation within atrial tissue.

To evaluate MPO-dependent effects on atrial remodeling in humans, we tested whether the incidence of atrial fibrillation in individuals implanted with pacemakers (n = 42) for a period of 114 ± 73 d (Supplementary Table 2) correlated with MPO plasma concentrations. Studying individuals who all were carriers of a new-generation dual-chamber pacemaker allowed for continuous atrial sensing over the entire follow-up period for the detection of atrial fibrillation. Twenty-four individuals showed atrial fibrillation (atrial fibrillation burden defined as the percentage of time during which the atrial rate of depolarization exceeded 200 per min: 45.2% ± 39.9%, equaling 871 ± 1,541 h of atrial fibrillation). The individuals with atrial fibrillation showed significantly higher MPO plasma concentrations than those without atrial fibrillation (503.1 pmol l−1 (interquartile range: 404.6–880.7 pmol l−1) versus 437.8 pmol l−1 (interquartile range 348.9–488.0 pmol l−1; P = 0.025)), which correlated with the atrial fibrillation burden (Spearman's rho: 0.5; P = 0.002). Circulating concentrations of elastase, an enzyme stored in the same neutrophil granules as MPO, were also significantly elevated in individuals with atrial fibrillation (50.5 ± 23.9 ng ml−1 versus 38.3 ± 12.4 ng ml−1; P = 0.039), and also correlated with the atrial fibrillation burden (r = 0.5; P = 0.004), underscoring the concept that increased MPO concentrations are a reflection of leukocyte activation and degranulation.

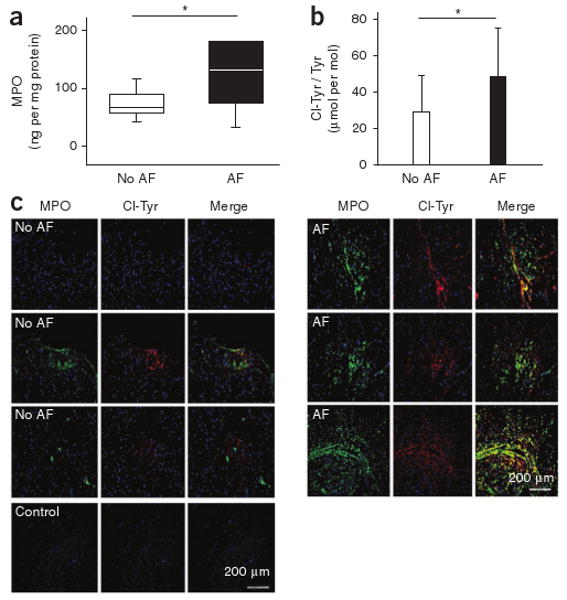

To test whether MPO is locally sequestered within the atria, we measured MPO concentrations and performed immunohistochemical studies in specimens derived from right atrial appendages of a cohort of individuals undergoing coronary bypass surgery (n = 27, Supplementary Table 3). Individuals with concomitant atrial fibrillation showed substantially higher atrial MPO deposition (Fig. 4a) and enhanced tissue 3-chlorotyrosine content (Fig. 4b), which colocalized with MPO, as evidenced by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 4c). These findings underscore the role of MPO as a mediator of the observed post-translational protein modification 3-chlorotyrosine.

Figure 4.

Atrial MPO amounts and protein-bound 3-chlorotyrosine in individuals with or without atrial fibrillation. (a) Quantification of MPO content in tissue homogenates of right atrial appendages of individuals undergoing on-pump coronary bypass surgery, as determined by ELISA normalized to protein concentration (no atrial fibrillation: n = 17, atrial fibrillation: n = 10). Data are presented as median (line) and interquartile range (box); whiskers indicate 5% and 95% percentiles, *P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed by the Mann-Whitney U test. (b) LC-MS–based quantitative assessment of 3-chlorotyrosine in atrial tissue of the same individuals. Data are means ± s.d. *P < 0.05. Unpaired Student's t test was used for statistical analysis. (c) Immunofluorescent staining of human right atrial appendage tissue. Left, three representative examples of MPO and the MPO-specific oxidant 3-chlorotyrosine from seven individuals without documented atrial fibrillation. Right, three representative images of right atrial appendage tissue from seven individuals with atrial fibrillation.

Our current work suggests that MPO is linked to the pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation. We found that the availability of MPO was increased systemically and locally in humans and mice with atrial fibrillation; MPO administration to mice led to structural changes, namely atrial fibrosis, known to be associated with the development of atrial fibrillation; genetic deficiency of MPO in mice profoundly decreased their vulnerability to atrial fibrillation; and reconstitution of MPO in these mice reestablished their vulnerability to atrial fibrillation in an AngII–independent fashion.

Atrial fibrosis is considered a key prerequisite for the initiation and propagation of atrial fibrillation25–27 and serves as a substrate for atrial fibrillation20. In considering subcellular mediators linking structural changes in the atria and the susceptibility for atrial fibrillation, AngII stands out as having a central role. AngII, generated either systemically or locally in the atria, propagates atrial dilatation, fibrosis and, ultimately, atrial fibrillation17. Our data extend the understanding of the contributory role of AngII in atrial fibrillation by revealing that AngII also elicits profibrotic and proarrhythmic properties independent of its direct effects on cardiac myocytes. Mpo−/− mice showed markedly reduced atrial fibrosis and were almost completely protected from the increased vulnerability to atrial fibrillation caused by AngII administration; both of these effects were dose-dependently reversed upon restitution of MPO. Thus, MPO acts as a major downstream mediator of atrial fibrosis and atrial arrhythmogeneity.

In search of the molecular mechanisms underlying MPO-dependent atrial fibrosis, we focused on atrial MMP activity. Increased activity of MMPs has been firmly linked to elevated atrial ECM turnover, fibrosis and atrial fibrillation11. MPO regulates MMP activity via post-translational modifications mediated by generation of HOCl in a concentration-dependent manner12,13. Here we showed that the abundance of 3-chlorotyrosine, a post-translational modification of proteins by the MPO-generated oxidant HOCl28, was increased within the atrial tissue of WT mice treated with AngII compared to vehicle-treated WT mice. The reduction in atrial tissue 3-chlorotyrosine content in Mpo−/− mice was accompanied by substantially reduced endogenous MMP activity in atria from these mice, consistent with the idea that MPO-dependent regulation of MMP activity is a key contributor to increased ECM turnover and atrial fibrosis.

The electrophysiological data obtained from vehicle-, AngII- and MPO-treated Mpo−/− mice complement these structural findings and identify a specific inflammatory mediator crucially linked to atrial fibrillation. These findings support the notion that MPO binding to the atria, protein oxidation and atrial fibrosis are required for the development of atrial fibrillation, a conclusion that was also supported by study of atrial specimens from humans with atrial fibrillation.

Certainly, other MPO-catalyzed oxidation reactions linked to increased cardiomyocyte apoptosis or inactivation of redox-sensitive enzyme systems such as myofibrillar creatine kinase29 may also contribute to protection from atrial fibrillation in MPO-deficient mice. Furthermore, MPO-dependent oxidants have been linked to inhibition of inhibitors of protease cascades such as α1-antitrypsin30 and tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases31. In addition, elevated arterial blood pressure in AngII-treated, MPO-competent mice may also have promoted atrial fibrosis. However, the fact that MPO supplementation alone did not affect blood pressure indicates that the observed structural effects mediated by MPO do not depend on increased afterload.

Taken together, the evidence provided here—documenting atrial accumulation of MPO accompanied by augmented fibrosis in mice and humans with atrial fibrillation—suggests that MPO is intimately involved in the pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation. Given that current pharmacological strategies to treat atrial fibrillation are, for the most part, of limited clinical efficacy and directed mainly at ion channels, MPO may serve as a potential new target of treatment in this disease.

Online Methods

Angiotensin II and myeloperoxidase treatment of mice

We treated male C57BL/6J (WT) and MPOtm1lus mice (Mpo−/−, Jackson Laboratory) on a C57BL/6 background, aged 12–15 weeks, via ALZET osmotic pumps with AngII (1.5 ng per g body weight per min, Sigma) or saline (vehicle) for 14 d before electrophysiological investigation. We treated another cohort of WT and Mpo−/− mice via ALZET osmotic pumps with a connected jugular catheter with recombinant MPO (3174-MP-250, R&D Systems, 5.0, 12.5 and 50 pg per g body weight per min, which we calculated to generate physiological plasma concentrations of MPO ranging between 100 and 1100 pM) or recombinant human serum albumin (Sigma) for 7 d in combination with either AngII or saline before electrophysiological investigation. Mouse experiments conformed with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health and were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Hamburg and the University of Bonn.

Electrophysiological investigation

We examined mice electrophysiologically by a single catheter technique19,32. We analyzed standard electrocardiogram parameters obtained by a six-lead surface electrocardiogram. Electrophysiological investigation included transvenous atrial and ventricular recording and stimulation21. For induction of atrial fibrillation, we performed atrial and ventricular burst and programmed atrial stimulations. We defined atrial fibrillation as rapid and fragmented atrial electrograms with irregular atrioventricular-nodal conduction for >1 s. We classified atrial fibrillation episodes persisting longer than 1 min as sustained atrial fibrillation. We analyzed the number, duration and probability of inducible atrial fibrillation episodes.

Epicardial mapping of Langendorff-perfused hearts

We determined spontaneous and stimulated myocardial conduction velocities and characteristics of Langendorff-perfused hearts by epicardial activation mapping with a 128-electrode array21.

Ex vivo electrophysiology studies

We isolated atrial myocytes enzymatically from WT and Mpo−/− mice and recorded action potentials by the ruptured-patch whole-cell patch-clamp technique33.

Assessment of myeloperoxidase content in human and mouse plasma and atrial tissue

We determined MPO concentrations by ELISA according to the manufacturer's instructions (human: CardioMPO kit, PrognostiX; mouse: HK210 kit, Hycult Biotechnology).

Detection of myeloperoxidase, 3-chlorotyrosine and matrix metalloproteinase-9

We incubated sections of human right atrial appendages and mouse atrial tissue with antibodies to MPO (475915, Calbiochem) and to chlorotyrosine (HP5002, Hycult Biotechnology). We assessed the protein-bound 3-chlorotyrosine content of mouse and human hearts by stable isotope dilution liquid chromatography with on-line tandem mass spectrometry on a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (ABI 3000 with redesigned source by Ionics) interfaced to an Aria LX Series HPLC (Cohesive Technologies)34. In brief, before tissue homogenization and acid hydrolysis with methane sulfonic acid, we added synthetic [13C6]-3-chlorotyrosine to samples as an internal standard for quantification of 3-chlorotyrosine. Simultaneous monitoring for the potential formation of artifactual 3-chlorotyrosine (detected as [13C9,15N] isotopomer) during sample preparation showed no detectable intrapreparative chlorination under the assay conditions employed. We detected pro–MMP-9 and MMP-9 by western blotting with a specific antibody (AF909, R&D Systems).

Histological assessment of fibrosis in mouse atria

We used the picrosirius polarization method for quantitative evaluation of fibrosis35. Quantitative analysis was performed by two independent pathologists blinded to the identity of the treatment groups.

Gelatin zymography

We performed zymography to measure MMP-2 and MMP-9 activities as described previously11.

Radiotelemetric blood pressure measurements

We performed blood pressure measurements as described previously36. In brief, we inserted the tip of the telemetry device (TA11PA-C10; Data Sciences International) into the carotid lumen. After 10 d, data acquisition started for 1 min every 5 min for 3 d. Thereafter, we started AngII, MPO or vehicle treatment. We recorded blood pressure and heart rate for one week in MPO-treated mice and 2 weeks in AngII-treated mice starting 3 d after mini-pump implantation.

Mouse echocardiographic studies

We determined maximal left atrial diameters in a modified parasternal long-axis view with a Vevo 770 microimaging system equipped with a 30-MHz center frequency single-element transducer.

Human study outline

Human studies, performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, were approved by the Board of Physicians Ethics Committee Hamburg, and we obtained written informed consent. We included 42 individuals with an already implanted newer-generation, dual-chamber pacemaker in the study, which allowed for continuous monitoring of atrial rhythm. Exclusion criteria were acute coronary syndrome within 1 month before study entry, decompensated heart failure, acute or chronic infections, malignancies, autoimmune disorders, renal failure and severe valvular dysfunction. At baseline, we collected venous blood samples and carried out transthoracic echocardiography to assess ejection fraction according to Simpson's rule, functional status of the heart valves and left atrial diameter37. We performed pacemaker interrogation to obtain the intervention rate, the time interval since the last interrogation and the atrial fibrillation burden at baseline and after 3 months of the follow-up period. We defined the atrial fibrillation burden as the percentage of time during which the atrial rate of depolarization exceeded 200 per min. We defined the presence of atrial fibrillation as an atrial fibrillation burden greater than 0% according to the memory read-out of the pacemaker. We also obtained right atrial appendages from 27 individuals undergoing elective coronary artery bypass surgery (ten individuals with persistent atrial fibrillation and 17 without atrial fibrillation). We determined plasma and atrial concentrations of MPO (CardioMPO, PrognostiX) and plasma concentrations of elastase (RE70731, IBL) by ELISA according to the manufacturer's recommendations. We assessed amounts of atrial 3-chlorotyrosine by LC-MS as stated above.

Statistical analyses

The aim of the human study was to detect a minimal difference of 15% in MPO plasma concentrations (logarithmized because of an assumed non-normal distribution) between the two groups with a two-sided α of 0.05 and a power (1 – β) of 0.80. Sample size calculation based on previous trials gave a formal sample size of n = 17. Categorical data are presented as frequencies, and we compared percentages and by χ2 test. We tested continuous variables for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Normally-distributed variables are presented as mean ± s.d.; for non-normally distributed data, the median and interquartile range is given. To test for differences between groups, we used Student's t test for normally distributed data and the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data. In the case of multiple groups, we used one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's post hoc test or the Kruskal-Wallis test with the Mann-Whitney U post hoc test. We assessed correlations between parameters with Spearman's correlation according to distribution of data. We considered a P value <0.05 as statistically significant. We carried out all statistical analyses with SPSS Version 15.0 (SPSS).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank H. Wieboldt for expert technical assistance. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (BA 1870/3-2 and BA 1870/7-1 to S.B., Ru 1472/1-1 to T.K.R. and SFB-TR19 to K.K.), the US National Institutes of Health (P01 HL076491-055328 and P01 HL087018-02001 to S.H.), the Deutsche Herzstiftung (to V.R. and R.P.A.) and the Werner Otto Stiftung (to S.B.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: V.R. designed the project, performed experiments, performed statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. T.K.R. performed experiments and prepared the manuscript. K.F., A.K., K. Sydow, D.L., E.-C.v.L. and K. Szoecs performed experiments. R.P.A., J.W.S., T.L. and G.N. were responsible for the design and the performance of the electrophysiological studies in mice. B.H.-H., A.P.S., A.S. and H.E. were responsible for the radiotelemetric measurements in mice and cellular electrophysiology. X.F. and S.L.H. were responsible for mass spectrometry analysis. M.D. performed the echocardiography in mice. H.T. provided human atrial tissue. K.K. was responsible for the fibrosis analysis. U.W., W.-H.Z., R.H.B., H.R., T.M., T.E., H.E., S.L.H., B.A.F. and S.W. provided suggestions on the project and revised the manuscript. S.B. supervised the project and wrote the manuscript.

Competing Financial Interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Medicine website.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions/.

References

- 1.Issac TT, Dokainish H, Lakkis NM. Role of inflammation in initiation and perpetuation of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review of the published data. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2021–2028. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kannel WB, Wolf PA, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Prevalence, incidence, prognosis and predisposing conditions for atrial fibrillation: population-based estimates. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:2N–9N. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00583-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nattel S, Opie LH. Controversies in atrial fibrillation. Lancet. 2006;367:262–272. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kannel WB, Abbott RD, Savage DD, McNamara PM. Epidemiologic features of chronic atrial fibrillation: the Framingham study. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:1018–1022. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198204293061703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aviles RJ, et al. Inflammation as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2003;108:3006–3010. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000103131.70301.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sata N, et al. C-reactive protein and atrial fibrillation. Is inflammation a consequence or a cause of atrial fibrillation? Jpn Heart J. 2004;45:441–445. doi: 10.1536/jhj.45.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conway DS, Buggins P, Hughes E, Lip GY. Prognostic significance of raised plasma levels of interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein in atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J. 2004;148:462–466. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fontes ML, Mathew JP, Rinder HM, Zelterman D, Smith BR, Rinder CS, et al. Atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery/cardiopulmonary bypass is associated with monocyte activation. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:17–23. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000155260.93406.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frustaci A, et al. Histological substrate of atrial biopsies in patients with lone atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 1997;96:1180–1184. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.4.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakamura Y, et al. Tissue factor expression in atrial endothelia associated with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: possible involvement in intracardiac thrombogenesis. Thromb Res. 2003;111:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(03)00405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen CL, et al. Upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in rapid atrial pacing-induced atrial fibrillation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;45:742–753. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu X, Kassim SY, Parks WC, Heinecke JW. Hypochlorous acid oxygenates the cysteine switch domain of pro-matrilysin (MMP-7). A mechanism for matrix metalloproteinase activation and atherosclerotic plaque rupture by myeloperoxidase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:41279–41287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106958200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu X, Kassim SY, Parks WC, Heinecke JW. Hypochlorous acid generated by myeloperoxidase modifies adjacent tryptophan and glycine residues in the catalytic domain of matrix metalloproteinase-7 (matrilysin): an oxidative mechanism for restraining proteolytic activity during inflammation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28403–28409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304739200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baldus S, et al. Endothelial transcytosis of myeloperoxidase confers specificity to vascular ECM proteins as targets of tyrosine nitration. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1759–1770. doi: 10.1172/JCI12617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin CS, Pan CH. Regulatory mechanisms of atrial fibrotic remodeling in atrial fibrillation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1489–1508. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7408-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casaclang-Verzosa G, Gersh BJ, Tsang TS. Structural and functional remodeling of the left atrium: clinical and therapeutic implications for atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burstein B, Nattel S. Atrial fibrosis: mechanisms and clinical relevance in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:802–809. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiao HD, et al. Mice with cardiac-restricted angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) have atrial enlargement, cardiac arrhythmia and sudden death. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1019–1032. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63363-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roell W, et al. Engraftment of connexin 43-expressing cells prevents post-infarct arrhythmia. Nature. 2007;450:819–824. doi: 10.1038/nature06321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verheule S, et al. Increased vulnerability to atrial fibrillation in transgenic mice with selective atrial fibrosis caused by overexpression of TGF-beta1. Circ Res. 2004;94:1458–1465. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000129579.59664.9d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schrickel JW, et al. Enhanced heterogeneity of myocardial conduction and severe cardiac electrical instability in annexin A7-deficient mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;76:257–268. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El Bekay R, et al. Oxidative stress is a critical mediator of the angiotensin II signal in human neutrophils: involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinase, calcineurin, and the transcription factor NF-κB. Blood. 2003;102:662–671. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abu-Soud HM, Hazen SL. Nitric oxide is a physiological substrate for mammalian peroxidases. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37524–37532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.48.37524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eiserich JP, et al. Formation of nitric oxide–derived inflammatory oxidants by myeloperoxidase in neutrophils. Nature. 1998;391:393–397. doi: 10.1038/34923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burstein B, Qi XY, Yeh YH, Calderone A, Nattel S. Atrial cardiomyocyte tachycardia alters cardiac fibroblast function: A novel consideration in atrial remodeling. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;76:442–452. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polyakova V, Miyagawa S, Szalay Z, Risteli J, Kostin S. Atrial extracellular matrix remodelling in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:189–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossi MA. Pathologic fibrosis and connective tissue matrix in left ventricular hypertrophy due to chronic arterial hypertension in humans. J Hypertens. 1998;16:1031–1041. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816070-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hazen SL, Heinecke JW. 3-chlorotyrosine, a specific marker of myeloperoxidase-catalyzed oxidation, is markedly elevated in low density lipoprotein isolated from human atherosclerotic intima. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2075–2081. doi: 10.1172/JCI119379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mihm MJ, et al. Impaired myofibrillar energetics and oxidative injury during human atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2001;104:174–180. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Desrochers PE, Mookhtiar K, Van Wart HE, Hasty KA, Weiss SJ. Proteolytic inactivation of α1-proteinase inhibitor and alpha 1-antichymotrypsin by oxidatively activated human neutrophil metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:5005–5012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y, et al. Myeloperoxidase inactivates TIMP-1 by oxidizing its N-terminal cysteine residue: an oxidative mechanism for regulating proteolysis during inflammation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:31826–31834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704894200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schrickel JW, et al. Induction of atrial fibrillation in mice by rapid transesophageal atrial pacing. Basic Res Cardiol. 2002;97:452–460. doi: 10.1007/s003950200052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwoerer AP, et al. Mechanical unloading of the rat heart involves marked changes in the protein kinase-phosphatase balance. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;45:846–852. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng L, et al. Apolipoprotein AI is a selective target for myeloperoxidase-catalyzed oxidation and functional impairment in subjects with cardiovascular disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:529–541. doi: 10.1172/JCI21109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lang C, et al. Connective tissue growth factor: a crucial cytokine-mediating cardiac fibrosis in ongoing enterovirus myocarditis. J Mol Med. 2008;86:49–60. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0249-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Butz GM, Davisson RL. Long-term telemetric measurement of cardiovascular parameters in awake mice: a physiological genomics tool. Physiol Genomics. 2001;5:89–97. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2001.5.2.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheitlin MD, et al. ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 guideline update for the clinical application of echocardiography: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ASE Committee to Update the 1997 Guidelines for the Clinical Application of Echocardiography) Circulation. 2003;108:1146–1162. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000073597.57414.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.