Abstract

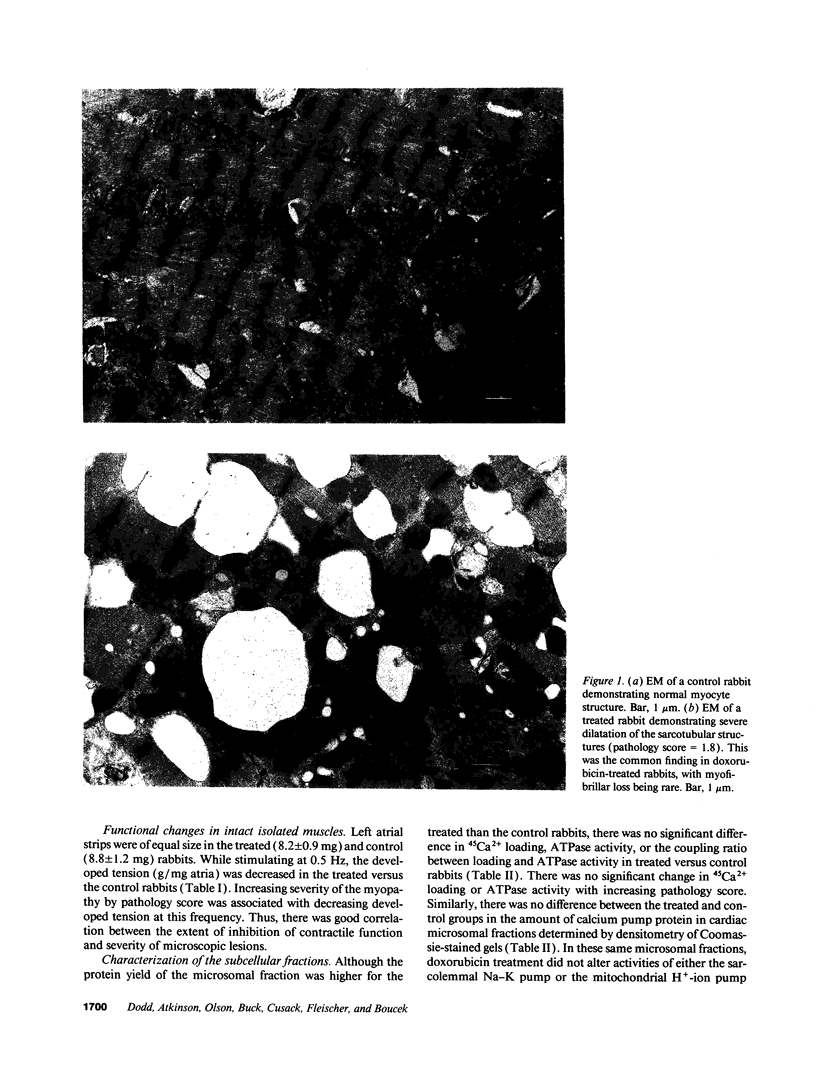

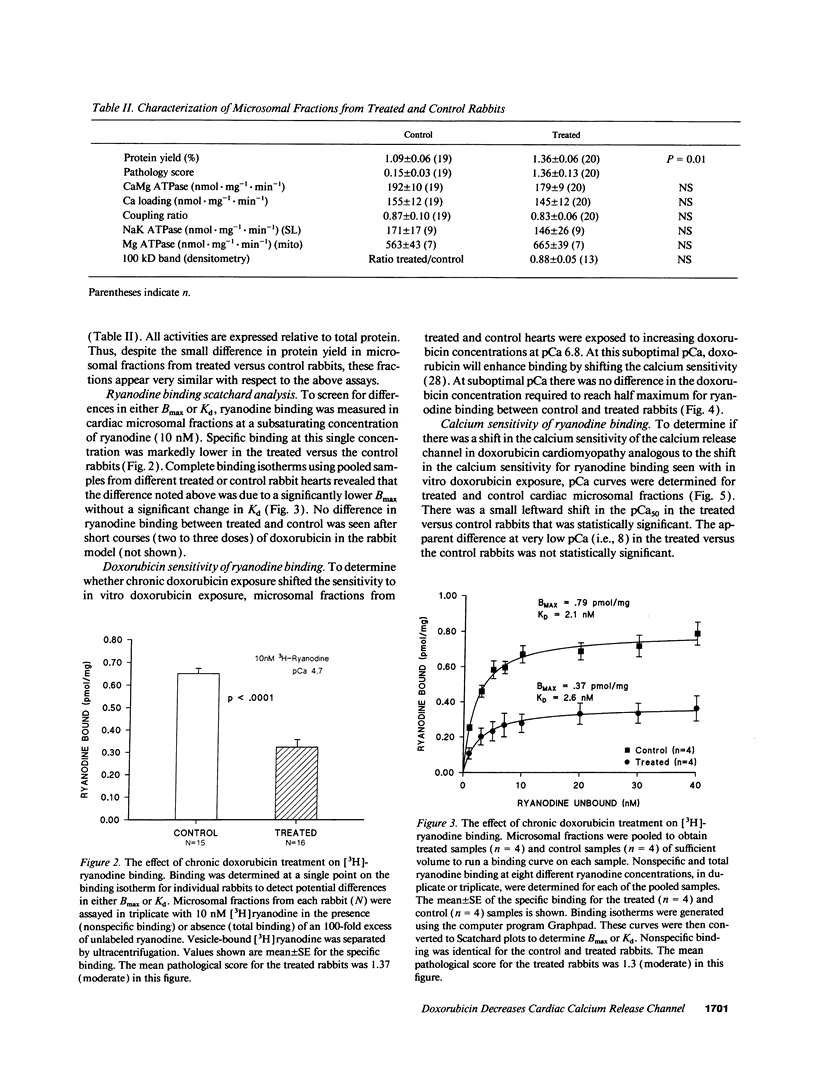

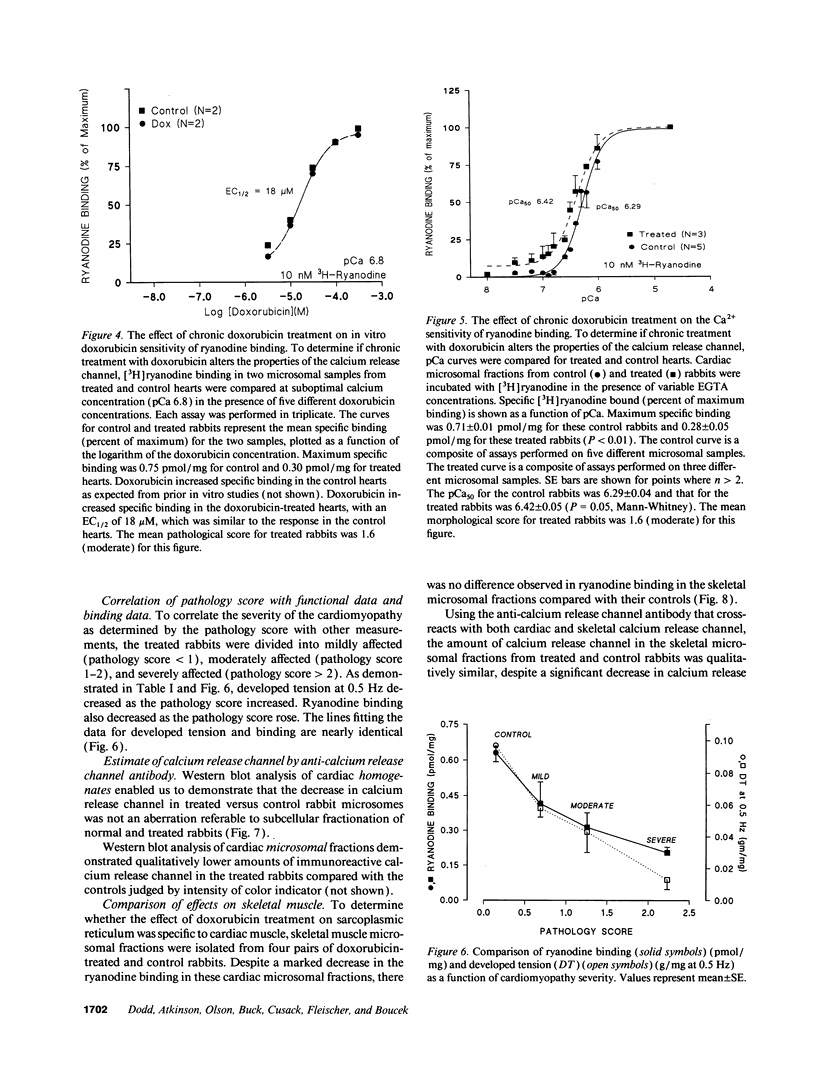

Doxorubicin is a highly effective cancer chemotherapeutic agent that produces a dose-dependent cardiomyopathy that limits its clinical usefulness. Clinical and animal studies of morphological changes during the early stages of doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy have suggested that the sarcoplasmic reticulum, the intracellular membrane system responsible for myoplasmic calcium regulation in adult mammalian heart, may be the early target of doxorubicin. To detect changes in the calcium pump protein or the calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) of the sarcoplasmic reticulum during chronic doxorubicin treatment, rabbits were treated with intravenous doxorubicin (1 mg/kg) twice weekly for 12 to 18 doses. Pair-fed controls received intravenous normal saline. The severity of cardiomyopathy was scored by light and electron microscopy of left ventricular papillary muscles. Developed tension was measured in isolated atrial strips. In subcellular fractions from heart, [3H]ryanodine binding was decreased in doxorubicin-treated rabbits (0.33 +/- 0.03 pmol/mg) compared with control rabbits (0.66 +/- 0.02 pmol/mg; P < 0.0001). The magnitude of the decrease in [3H]ryanodine binding correlated with both the severity of the cardiomyopathy graded by pathology score (light and electron microscopy) and the decrease in developed tension in isolated atrial strips. Bmax for [3H]ryanodine binding and the amount of immunoreactive ryanodine receptor by Western blot analysis using sequence-specific antibody were both decreased, consistent with a decrease in the amount of calcium release channel of sarcoplasmic reticulum in doxorubicin-treated rabbits. In contrast, there was no decrease in the amount or the activity of the calcium pump protein of the sarcoplasmic reticulum in doxorubicin-treated rabbits. Doxorubicin treatment did not decrease [3H]ryanodine binding or the amount of immunoreactive calcium release channel of sarcoplasmic reticulum in skeletal muscle. Since the sarcoplasmic reticulum regulates muscle contraction by the cyclic uptake and release of a large internal calcium pool, altered function of the calcium release channel could lead to the abnormalities of contraction and relaxation observed in the doxorubicin cardiomyopathy.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abramson J. J., Buck E., Salama G., Casida J. E., Pessah I. N. Mechanism of anthraquinone-induced calcium release from skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1988 Dec 15;263(35):18750–18758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramson J. J., Salama G. Critical sulfhydryls regulate calcium release from sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1989 Apr;21(2):283–294. doi: 10.1007/BF00812073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnolda L., McGrath B., Cocks M., Sumithran E., Johnston C. Adriamycin cardiomyopathy in the rabbit: an animal model of low output cardiac failure with activation of vasoconstrictor mechanisms. Cardiovasc Res. 1985 Jun;19(6):378–382. doi: 10.1093/cvr/19.6.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachur N. R., Hildebrand R. C., Jaenke R. S. Adriamycin and daunorubicin disposition in the rabbit. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1974 Nov;191(2):331–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellini O., Solcia E. Early and late sarcoplasmic reticulum changes in doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. An ultrastructural investigation with the zinc iodide-osmium tetroxide (ZIO) technique. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol. 1985;49(2):137–152. doi: 10.1007/BF02912092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucek R. J., Jr, Olson R. D., Brenner D. E., Ogunbunmi E. M., Inui M., Fleischer S. The major metabolite of doxorubicin is a potent inhibitor of membrane-associated ion pumps. A correlative study of cardiac muscle with isolated membrane fractions. J Biol Chem. 1987 Nov 25;262(33):15851–15856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow M. R., Billingham M. E., Mason J. W., Daniels J. R. Clinical spectrum of anthracycline antibiotic cardiotoxicity. Cancer Treat Rep. 1978 Jun;62(6):873–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick C. C., Saito A., Fleischer S. Isolation and characterization of the inositol trisphosphate receptor from smooth muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Mar;87(6):2132–2136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain B. K., Fleischer S. Isolation of canine cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Methods Enzymol. 1988;157:91–99. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)57071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu A., Dixon M. C., Saito A., Seiler S., Fleischer S. Isolation of sarcoplasmic reticulum fractions referable to longitudinal tubules and junctional terminal cisternae from rabbit skeletal muscle. Methods Enzymol. 1988;157:36–46. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)57066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer V. W., Wang G. M., Hobart N. H. Mitigation of an anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy by pretreatment with razoxane: a quantitative morphological assessment. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol. 1986;51(4):353–361. doi: 10.1007/BF02899044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer S., Inui M. Biochemistry and biophysics of excitation-contraction coupling. Annu Rev Biophys Biophys Chem. 1989;18:333–364. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.18.060189.002001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freter C. E., Lee T. C., Billingham M. E., Chak L., Bristow M. R. Doxorubicin cardiac toxicity manifesting seven years after treatment. Case report and review. Am J Med. 1986 Mar;80(3):483–485. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90724-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goorin A. M., Borow K. M., Goldman A., Williams R. G., Henderson I. C., Sallan S. E., Cohen H., Jaffe N. Congestive heart failure due to adriamycin cardiotoxicity: its natural history in children. Cancer. 1981 Jun 15;47(12):2810–2816. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810615)47:12<2810::aid-cncr2820471210>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goorin A. M., Chauvenet A. R., Perez-Atayde A. R., Cruz J., McKone R., Lipshultz S. E. Initial congestive heart failure, six to ten years after doxorubicin chemotherapy for childhood cancer. J Pediatr. 1990 Jan;116(1):144–147. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81668-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R. N., Doroshow J. H. Effect of doxorubicin-enhanced hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radical formation on calcium sequestration by cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985 Jul 31;130(2):739–745. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)90478-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H., Miller S. C., Billingham M. E., Akimoto H., Torti S. V., Wade R., Gahlmann R., Lyons G., Kedes L., Torti F. M. Doxorubicin selectively inhibits muscle gene expression in cardiac muscle cells in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Jun;87(11):4275–4279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaenke R. S. Delayed and progressive myocardial lesions after adriamycin administration in the rabbit. Cancer Res. 1976 Aug;36(8):2958–2966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julicher R. H., Sterrenberg L., Bast A., Riksen R. O., Koomen J. M., Noordhoek J. The role of lipid peroxidation in acute doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity as studied in rat isolated heart. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1986 Apr;38(4):277–282. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1986.tb04566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. H., Landry A. B., 3rd, Lee Y. S., Katz A. M. Doxorubicin-induced calcium release from cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum vesicles. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1989 May;21(5):433–436. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(89)90782-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefrak E. A., Pitha J., Rosenheim S., Gottlieb J. A. A clinicopathologic analysis of adriamycin cardiotoxicity. Cancer. 1973 Aug;32(2):302–314. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197308)32:2<302::aid-cncr2820320205>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis A. B., Crouse V. L., Evans W., Takahashi M., Siegel S. E. Recovery of left ventricular function following discontinuation of anthracycline chemotherapy in children. Pediatrics. 1981 Jul;68(1):67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis W., Gonzalez B. Actin isoform mRNA alterations induced by doxorubicin in cultured heart cells. Lab Invest. 1990 Jan;62(1):69–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipshultz S. E., Colan S. D., Gelber R. D., Perez-Atayde A. R., Sallan S. E., Sanders S. P. Late cardiac effects of doxorubicin therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. N Engl J Med. 1991 Mar 21;324(12):808–815. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103213241205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrew S. G., Wolleben C., Siegl P., Inui M., Fleischer S. Positive cooperativity of ryanodine binding to the calcium release channel of sarcoplasmic reticulum from heart and skeletal muscle. Biochemistry. 1989 Feb 21;28(4):1686–1691. doi: 10.1021/bi00430a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen S. A., Olsen H. S., Baandrup U. Chronic anthracycline cardiotoxicity: haemodynamic and histopathological manifestations suggesting a restrictive endomyocardial disease. Br Heart J. 1986 Mar;55(3):274–282. doi: 10.1136/hrt.55.3.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers C. E., McGuire W. P., Liss R. H., Ifrim I., Grotzinger K., Young R. C. Adriamycin: the role of lipid peroxidation in cardiac toxicity and tumor response. Science. 1977 Jul 8;197(4299):165–167. doi: 10.1126/science.877547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasaki K., Fleischer S. Modulation of the calcium release channel of sarcoplasmic reticulum by adriamycin and other drugs. Cell Calcium. 1989 Jan;10(1):63–70. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(89)90045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson H. M., Young D. M., Prieur D. J., LeRoy A. F., Reagan R. L. Electrolyte and morphologic alterations of myocardium in adriamycin-treated rabbits. Am J Pathol. 1974 Dec;77(3):439–454. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ondrias K., Borgatta L., Kim D. H., Ehrlich B. E. Biphasic effects of doxorubicin on the calcium release channel from sarcoplasmic reticulum of cardiac muscle. Circ Res. 1990 Nov;67(5):1167–1174. doi: 10.1161/01.res.67.5.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palade P. Drug-induced Ca2+ release from isolated sarcoplasmic reticulum. II. Releases involving a Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release channel. J Biol Chem. 1987 May 5;262(13):6142–6148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papoian T., Lewis W. Adriamycin cardiotoxicity in vivo. Selective alterations in rat cardiac mRNAs. Am J Pathol. 1990 Jun;136(6):1201–1207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessah I. N., Durie E. L., Schiedt M. J., Zimanyi I. Anthraquinone-sensitized Ca2+ release channel from rat cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum: possible receptor-mediated mechanism of doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. Mol Pharmacol. 1990 Apr;37(4):503–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salviati G., Volpe P. Ca2+ release from sarcoplasmic reticulum of skinned fast- and slow-twitch muscle fibers. Am J Physiol. 1988 Mar;254(3 Pt 1):C459–C465. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1988.254.3.C459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz R. G., McKenzie W. B., Alexander J., Sager P., D'Souza A., Manatunga A., Schwartz P. E., Berger H. J., Setaro J., Surkin L. Congestive heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction complicating doxorubicin therapy. Seven-year experience using serial radionuclide angiocardiography. Am J Med. 1987 Jun;82(6):1109–1118. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler S., Fleischer S. Isolation of plasma membrane vesicles from rabbit skeletal muscle and their use in ion transport studies. J Biol Chem. 1982 Nov 25;257(22):13862–13871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singal P. K., Deally C. M., Weinberg L. E. Subcellular effects of adriamycin in the heart: a concise review. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1987 Aug;19(8):817–828. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(87)80392-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solcia E., Ballerini L., Bellini O., Magrini U., Bertazzoli C., Tosana G., Sala L., Balconi F., Rallo F. Cardiomyopathy of doxorubicin in experimental animals, Factors affecting the severity, distribution and evolution of myocardial lesions. Tumori. 1981 Oct 31;67(5):461–472. doi: 10.1177/030089168106700512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornalley P. J., Dodd N. J. Free radical production from normal and adriamycin-treated rat cardiac sarcosomes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1985 Mar 1;34(5):669–674. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(85)90262-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimm J. L., Salama G., Abramson J. J. Sulfhydryl oxidation induces rapid calcium release from sarcoplasmic reticulum vesicles. J Biol Chem. 1986 Dec 5;261(34):16092–16098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unverferth D. V., Magorien R. D., Unverferth B. P., Talley R. L., Balcerzak S. P., Baba N. Human myocardial morphologic and functional changes in the first 24 hours after doxorubicin administration. Cancer Treat Rep. 1981 Nov-Dec;65(11-12):1093–1097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Vleet J. F., Ferrans V. J., Weirich W. E. Cardiac disease induced by chronic adriamycin administration in dogs and an evaluation of vitamin E and selenium as cardioprotectants. Am J Pathol. 1980 Apr;99(1):13–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Hoff D. D., Layard M. W., Basa P., Davis H. L., Jr, Von Hoff A. L., Rozencweig M., Muggia F. M. Risk factors for doxorubicin-induced congestive heart failure. Ann Intern Med. 1979 Nov;91(5):710–717. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-91-5-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts R. G. Severe and fatal anthracycline cardiotoxicity at cumulative doses below 400 mg/m2: evidence for enhanced toxicity with multiagent chemotherapy. Am J Hematol. 1991 Mar;36(3):217–218. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830360314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y. M., Hill K. E., Burk R. F. Biochemical studies of a selenium-deficient population in China: measurement of selenium, glutathione peroxidase and other oxidant defense indices in blood. J Nutr. 1989 Sep;119(9):1318–1326. doi: 10.1093/jn/119.9.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R. C., Ozols R. F., Myers C. E. The anthracycline antineoplastic drugs. N Engl J Med. 1981 Jul 16;305(3):139–153. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198107163050305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorzato F., Chu A., Volpe P. Antibodies to junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum proteins: probes for the Ca2+-release channel. Biochem J. 1989 Aug 1;261(3):863–870. doi: 10.1042/bj2610863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorzato F., Margreth A., Volpe P. Direct photoaffinity labeling of junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum with [14C]doxorubicin. J Biol Chem. 1986 Oct 5;261(28):13252–13257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorzato F., Salviati G., Facchinetti T., Volpe P. Doxorubicin induces calcium release from terminal cisternae of skeletal muscle. A study on isolated sarcoplasmic reticulum and chemically skinned fibers. J Biol Chem. 1985 Jun 25;260(12):7349–7355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]