Abstract

Interleukin (IL)-15 can cross the blood-brain barrier to act on its specific brain receptor (IL15Rα) and co-receptors. The important roles of neuronal IL15 and IL15Rα in experimental autoimmune encephalomeylitis (EAE) are suggested by the upregulation of IL15Rα mRNA in different regions of the brain and spinal cord, and by double-labeling immunohistochemistry showing neuronal localization of IL15 and IL15Rα in different neurons. Contrary to expectations, IL15 treatment lessened EAE severity. IL15 knockout mice showed heightened susceptibility to EAE with significantly higher scores that were decreased by treatment with IL15. Thus, IL15 improves this CNS autoimmune disorder as a potential therapeutic agent.

Keywords: IL15, cytokine, brain, immunity, autoimmune disease, blood-brain barrier

1. Introduction

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) reflects the autoimmune aspect of the human disease multiple sclerosis (MS), a devastating demyelinating disorder of the central nervous system (CNS) (Hart et al. 1998;'t Hart and Amor 2003). Despite the use of disease modifying agents including β interferons, glatiramer, mitoxantrone, and newer immunomodulatory agents, the prognosis remains poor for the relapsing-remitting and primary progressive types of MS. This warrants better understanding of its neuropathology and the search for novel therapeutic agents. Although proinfammatory cytokines play important roles in the progression of MS (Merrill et al. 1984;Zozulya et al. 2009), very few studies have directly addressed the role of interleukin (IL)-15 in MS and EAE. Here, we tested the hypotheses that the cerebral IL15 system is regulated by EAE and that it in turn modifies the severity of EAE.

IL15 is a 14 kD polypeptide that belongs to the IL2 subfamily of the four-alpha-helix bundle family of cytokines. IL15 binds to its specific receptor IL15Rα and two additional receptor subunits - IL2Rβ and IL2Rγ. IL15 mRNA has been found to be constitutively expressed in parenchymal cells of many organs as well as immune cells. In the nervous system, IL15 is expressed by neurons, astrocytes, and microglia (Lee et al. 1996;Budagian et al. 2006). Elevated expression of IL15 at both transcriptional and translational levels is found in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from MS patients (Pashenkov et al. 1999;Blanco-Jerez et al. 2002). Furthermore, upregulated IL15 is observed in serum and cerebrospinal fluid of MS patients (Losy et al. 2002;Rentzos et al. 2006). We have recently shown that EAE affects the distribution and turnover of IL15 after intravenous delivery which also alters the in-vivo BBB permeability to IL15 (Hsuchou et al. 2009b). This provides a basis to determine the functional roles of the IL15 system in EAE.

EAE is an ascending disease with a maximal increase in the permeability of the blood-brain and blood-spinal cord barrier (BBB) occurring in the lumbar and cervical spinal cord (Pan et al. 1996). Disruption of the BBB and demyelination are also pronounced in the brain. Although many EAE studies focused on neuropathology in the spinal cord, cerebral involvement probably has greater correlation with sickness behavior. In human MS, there is a higher incidence of supratentorial lesions than spinal cord demyelination. Therefore, the hippocampus was chosen as a region of interest for the study of EAE, since its susceptibility to neuroinflammation and corresponding behavioral changes have been well characterized (Pollak et al. 2002;Goshen et al. 2007;Dantzer et al. 2008). In this study, we determined both regulatory changes of the endogenous IL15 system and treatment effects of IL15. Further, the exciting finding that IL15 knockout (KO) mice show heightened susceptibility to EAE strongly supports an immunoprotective role of IL15 in EAE mice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Induction of EAE and IL15 treatment

All studies were conducted following a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. EAE was induced in female SJL/J (2 months old, Jackson Laboratory), IL15 KO (2 months old, C57BL/6NTac-IL15tm1Imx, Taconic), and their matching control (C57BL/6NTac) mice. The SJL/J mice were injected subcutaneously (sc) with 80 μg of proteolipid protein fragment 139–151 (PLP139–151, AnaSpec Inc., San Jose, CA), that was emulsified in either RIBI adjuvant (RIBI Immunochem Research Inc, Hamilton, MT), or complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) containing 500 μg of heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37RA. The injection was made in the lower flank (33 μl/spot × 3 injections). The control mice received adjuvant without PLP139–151. The IL15 KO mice and their controls received 100 μg of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)35–55 peptide along with 100 μl of CFA containing 4 mg/ml of heat-inactivated Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37RA. In mice receiving CFA adjuvant, pertussis toxin (200 ng in 100 μl phosphate buffered saline, PBS) was given intraperitoneally (ip) on the day of immunization and again 48 h later.

EAE was scored daily as follows: 0, no detectable signs of weakness; 0.5, distal tail limpness, mild postural changes, or reduced locomotor activity; 1, completely limp tail; 1.5, limp tail and hindlimb weakness (unsteady gait and poor grip with hindlimbs); 2, unilateral partial hindlimb paralysis; 2.5, bilateral hindlimb paralysis; 3, complete bilateral hindlimb paralysis; 3.5, complete hindlimb paralysis and unilateral forelimb paralysis; 4, total paralysis of hindlimbs and forelimbs; 5, moribund or dead.

To determine the effect of IL15 treatment on EAE score, two groups of SJL/J mice were studied (n = 8 /group). The experimental group received daily injection of IL15 at 100 ng/day/mouse ip from day 7 to day 14 after PLP + CFA immunization on day 0 (n = 8 /group). The control received PBS ip daily from day 7 to day 14. To determine the effect of IL15 deletion on EAE score, two separate groups of mice on C57 background were studied (n = 8 /group). All mice received MOG + CFA immunization. After apparent changes in EAE score between the IL15KO and wildtype mice were observed, half of the IL15KO mice were treated with IL15 (100 ng/day/mouse ip) from day 40 to day 55.

2.2. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) to determine the expression of IL15 and IL15Rα

SJL/J mice on day 12 after PLP + RIBI immunization were studied along with adjuvant controls. The mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and perfused intracardially with 4 % paraformaldehyde. Coronal sections of the hippocampus at 20 μm thickness were obtained by use of a cryostat. IHC was performed as described previously (Pan et al. 2008a;Hsuchou et al. 2009a). All primary antibodies and the corresponding blocking peptides were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The primary antibody for IL15 was L-20 (sc-1296, goat polyclonal against the C-terminus of IL15), and that for IL15Rα was N-19 (sc-5526, goat polyclonal against the N-terminus of IL15Rα). The secondary antibody was an Alexa488-conjugated anti-goat antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The specificity of the IL15 and IL15Rα immunostaining was confirmed by the lack of signal in sections where primary antibodies were preabsorbed with blocking peptide, and in sections with omission of primary antibodies. Double staining of the sections was conducted by inclusion of a primary mouse anti-NeuN antibody (MAB377B, Millipore, Temecula) with either IL15 or IL15Rα antibodies, followed by incubation with respective Alexa-conjugated secondary antibodies. Fluorescent images of matching sections between the control and experimental groups were captured by use of an Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope. The co-localization of IL15 with NeuN, or IL15Rα with NeuN, was determined by confocal microscopy.

2.3. ELISA of serum IL15

IL15 concentration in the serum of EAE mice after PLP + RIBI induction was measured with a mouse IL15 ELISA Ready-SET-Go kit (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). The linear range was 15.6 – 500 pg/ml with R2 = 0.99. EAE mice on day 3, 7, 12, 16, and 24 after induction were studied along with an adjuvant control group studied on day 3 (n = 3 – 4 for each time point).

2.4. Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from different brain and spinal cord tissues in the control and EAE mice at different days after PLP + RIBI immunization by use of an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The tissues analyzed included the hippocampus, striatum, hypothalamus, and cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spinal cord. After digestion with DNase I to eliminate trace amounts of DNA contamination, total RNA was purified with an RNA clean up kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA) and the concentration was measured by absorbance at 260 nm with a Bio-Rad spectrometer (Hercules, CA). Reverse transcription of the total RNA was conducted with a High Capacity cDNA Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The cDNA samples were incubated with Taqman® universal PCR master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Amplification was detected by use of an ABI 7900 instrument. Standard curves for quantification were generated with template plasmids containing fragments of the respective target genes. The level of expression of the target gene was normalized to that of glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in the same sample. All primers and fluorescent probes used for amplification are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Taqman primers and probes for real-time PCR

| Gene | Forward primer (FP) and reverse primer (RP) | Probes |

|---|---|---|

| IL15 | FP: ATGTTCATCAACACGTCCTGACT | 6-FAM-CATGCGAGCCTCTTCCGTGTTTCT-TAMRA |

| RP: GCAGCAGGTGGAGGTACCTTAA | ||

| IL15Rα | FP: CCAGGCCATTCCTGTGTTG | 6-FAM-CCGGGCACCACGTGTCCACC-TAMRA |

| RP: GATGTCAGCATGCTCAATAGATACG | ||

| IL2Rβ | FP: CGACTTCCATCCCTTTGACAA | 6-FAM-CTTCGCCTGGTGGCCCCTCATT-TAMRA |

| RP: TGGGTATCAATGTGCAGAACTTG | ||

| IL2Rγ | FP: GAAGCTGGACGGAACTAATAGTGAA | 6-FAM-GAACCTAGATTCTCCCTGCCTAGTGTGGA-TAMRA |

| RP: CTCCGAACCCGAAATGTGTAC | ||

| GAPDH | FP: TGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCTGA | 6-FAM-CCGCCTGGAGAAACCTGCCAAGTATG-TAMRA |

| RP: CCTGCTTCACCACCTTCTTGA |

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). For EAE scoring and treatment effects between groups, repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed. When both genders were tested, two-way ANOVA was performed to determine the effects of treatment (KO vs wildtype). Otherwise, pairwise comparisons between control and treatment groups were conducted by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. All graphs show mean ± standard error of the mean.

3. Results

3.1. EAE mice show behavioral deficits and elevated hippocampal IL15 and IL15Rα immunoreactivity in neurons

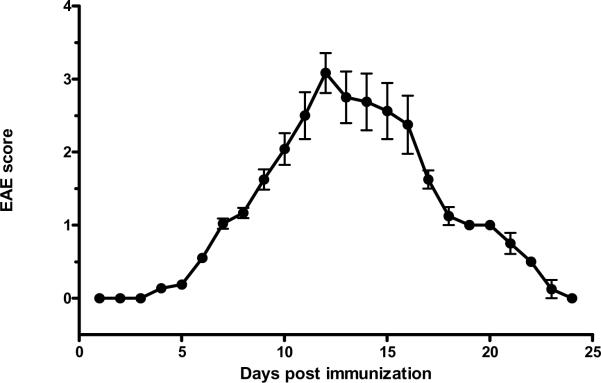

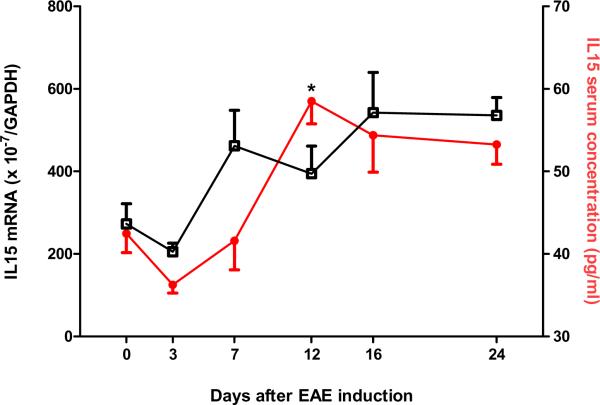

Two groups of mice were studied (n = 8 /group): those inoculated with PLP139–151 along with RIBI adjuvant (EAE group), and those receiving RIBI adjuvant only (control group). Mice in the EAE group showed a monophasic pattern of locomotor deficits. The EAE score, reflecting the deficits in motor activity and overall health, peaked at day 12 with a maximal score of 4 in individual mice (total paralysis of hindlimbs and forelimbs) and a mean score of 3 at this time (complete bilateral hindlimb paralysis). Afterwards, the scores decreased gradually so that clinical symptoms were absent on day 24 (Fig. 1). At day 0, 3, 7, 12, 16, and 24 after induction by PLP and RIBI adjuvant in the SJL/J mice (n = 4 /time point), blood IL15 concentrations, hippocampal IL15 immunoreactivity, and hippocampal IL15 mRNA were determined in the EAE mice. The 0 time control received RIBI adjuvant only. In these mice, serum IL15 concentrations showed a significant (p < 0.05) increase on day 12, rising from the basal low level of 2.5 ± 2.31 pg/ml to 58.52 ± 2.75 pg/ml (Fig. 2A). At this time, hippocampal IL15 immunoreactivity was also increased (Fig. 2B). Double-labeling immunohistochemistry showed that IL15 was mainly expressed in neurons (Fig. 2C).

Fig 1.

Progression of EAE score after induction with PLP139–151. Signs of weakness occurred on day 7. The scores peaked on day 12 and then returned to 0 (asymptomatic) on day 24 (n = 8).

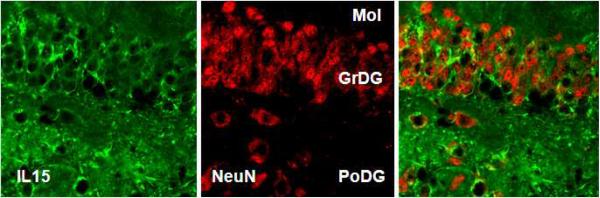

Fig 2.

Dynamic changes of IL15 expression in the EAE mice. (A) Hippocampal IL15 mRNA (left y-axis, squares) did not show a significant change from the control (time 0), though the levels from day 3 mice were significantly lower than those from day 16 and 24. Serum IL15 concentrations (right y-axis, closed circles) showed a significant increase on day 12 (58.51 ± 2.76 pg/ml) in comparison with controls (42.47 ± 2.31 pg/ml). *: p < 0.05. (B) IL15 immunoreactivity showed a neuronal pattern in the rostral hippocampus, and was higher in EAE (day 12) than control mice. Scale bar: 100 μm. (C) Double-labeling IHC showed that IL15 (green) and NeuN (red) were present in the same cells, indicating a neuronal source of IL15. Mol, molecular layer of the dentate gyrus; GrDG, granular layer of the dentate gyrus; PoDG, polymorph layer of the dentate gyrus.

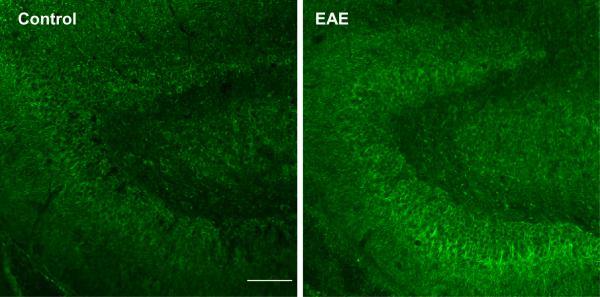

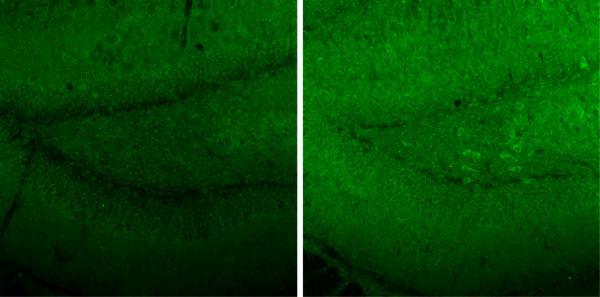

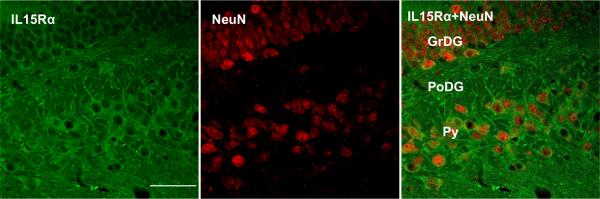

The increase of IL15Rα immunoreactivity was most pronounced in the hilus and granular cell layer of the infrapyramidal blade of the dendate gyrus (Fig. 3A). IL15Rα was also seen mainly in neurons, as shown by confocal microscopic analysis of tissue sections immunostained with both IL15Rα and NeuN (Fig. 3B). The hippocampal area with the highest intensity for IL15Rα was more caudal than that for IL15 seen in figure 2B. This suggests paracrine interactions.

Fig. 3.

Immunofluorescence of IL15Rα in the control and EAE mice. (A) On day 12 after EAE induction, there was a greater intensity of IL15Rα staining in hippocampal neurons in comparison with the control. Scale bar: 100 μm. (B) IL15Rα and NeuN double-labeling showed neuronal localization of the receptor. Scale bar: 50 μm. GrDG, granular layer of dentate gyrus; PoDG, polymorph layer dentate gyrus;, Py, pyramidal cell layer of the hippocampus.

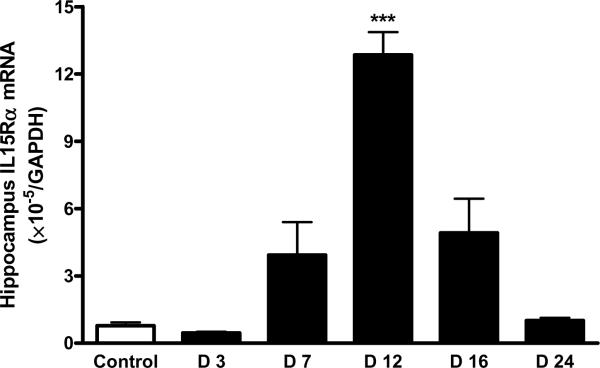

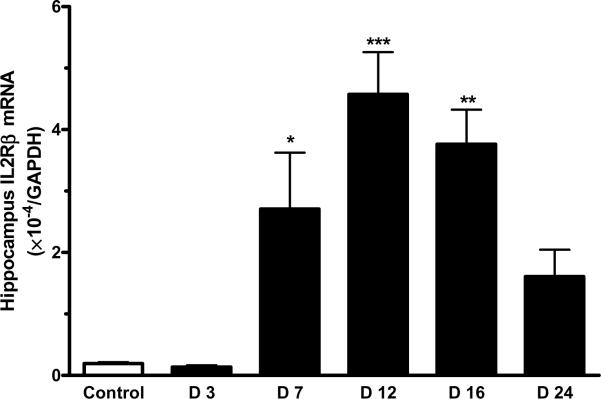

3.2. Time course of increased mRNA expression of IL15Rα, IL2Rβ, and IL2Rγ in the hippocampus of the EAE mice

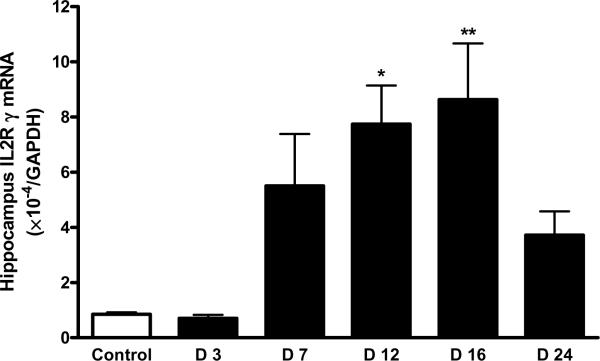

There was a robust increase of IL15Rα mRNA in the hippocampus of mice 12 d after EAE induction (p < 0.005). The increase on days 7 and 16 was not significant. By day 24, the mRNA for IL15Rα had returned to its low baseline (Fig. 4A). In comparison with the increase of IL15Rα, the elevation of IL2Rβ mRNA occurred earlier and lasted longer (day 7 – 16) in the hippocampus, although that in the hypothalamus was also significant on day 12 (Fig. 4B). IL2Rγ mRNA showed a significant increase on day 12 and day 16 (Fig. 4C).

Fig 4.

EAE induction was associated with a time-dependent increase in the level of mRNA expression of IL15 receptors in hippocampus. (A) IL15Rα; (B) IL2Rβ; and (C) IL2Rγ. *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001.

IL15 mRNA in the hippocampus showed a significant overall change determined by one-way ANOVA. However, there was no significant increase in any of the EAE groups in comparison with the controls. The elevation of IL15 protein without a significant increase of its mRNA suggests that the increase occurred at a post-transcriptional level.

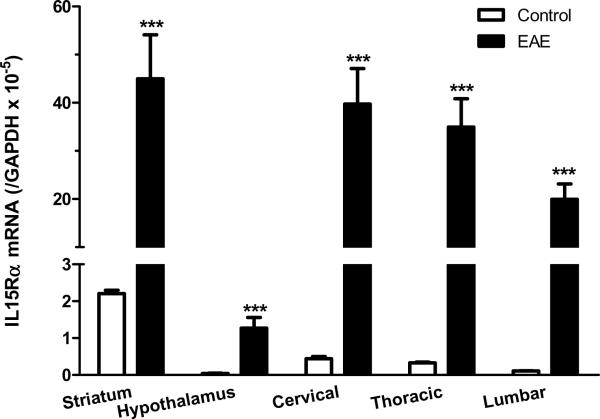

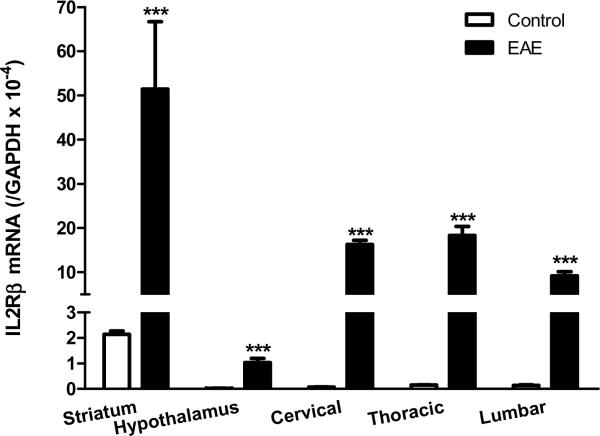

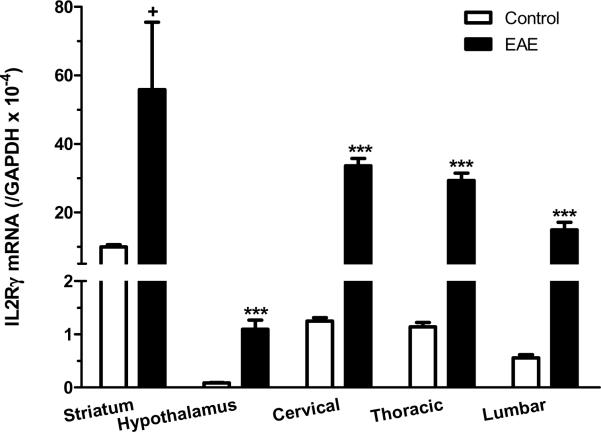

3.3. Spatial patterns of increased mRNA expression of IL15Rα, IL2Rβ, and IL2Rγ at the peak of EAE

Although we focused on the hippocampus in IHC analyses, IL15 and its receptors showed ubiquitous expression in the brain and spinal cord. High basal levels of IL15Rα and its co-receptors were also seen in the striatum. At the peak of EAE (day 12 after induction by PLP139–152 with RIBI adjuvant), there was an elevation of mRNA for all three receptor subtypes in the striatum and hypothalamus, though other brain regions were not sampled. In the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spinal cord, the mRNA for IL15Rα, IL2Rβ, and IL2Rγ also showed a significant increase on day 12 of EAE (Fig.5A–C). This suggests a widespread activation of IL15 signaling within the CNS of the EAE mice.

Fig. 5.

mRNA of IL15 receptors in striatum, hypothalamus, and cervical, thoracic and lumbar spinal cord on day 12 after EAE induction. (A) IL15Rα; (B) IL2Rβ; and (C) IL2Rγ. +: p < 0.06; ***: p < 0.001.

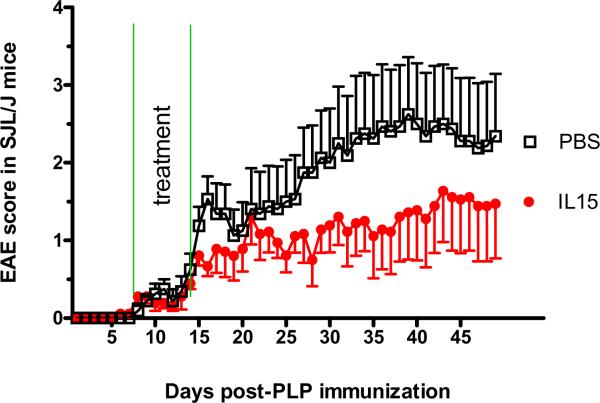

3.3. IL15 treatment reduces the severity of EAE

We also used CFA instead of RIBI adjuvant in the induction of EAE by PLP peptide in the SJL/J mice. The mice challenged with PLP + CFA showed lower EAE scores and delayed occurrence of symptoms, but the weakness lasted longer. These mice were randomly divided into groups receiving IL15 (100 ng/mouse/d ip) and PBS (n = 8 /group). The mice were treated from day 7 to 14, and observed until day 50. The choice of time to initiate treatment was based on the observation of symptom onset in the SJL/J mice treated with PLP + RIBI shown in figure 1. Treatment endpoint was determined by the observation of weakness on day 15 in the mice treated with PLP + CFA. IL15 treatment induced a decrease of EAE score that was evident by day 15 and lasted until the end of the study. The IL15-treated group showed a maximal EAE score of 1.5 in the IL15-treated group, whereas the control group has a maximal score of 2.5 (Fig. 6A). The PBS treated mice showed an initial small increase of symptoms (day 15–18), followed by a brief plateau for 2 days and then a persistent increase of EAE score. The IL15 treated group showed a smaller, rather inconspicuous peak on day 21. This might reflect different stages of immune and inflammatory processes in these mice. It is probably not caused by technical problems such as injury of the sciatic nerve during the inoculation, which would induce an earlier onset of transient weakness. Although the overall effect of IL15 treatment was statistically significant when analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA, only 33 % of the treated mice showed EAE scores higher than 2.0. This is in contrast with an incidence rate of 88 % in the control group. This average reduction of EAE score by 55 % reflects an apparent alleviation of the symptoms. Fisher's exact test for an EAE score of 2 showed that the difference between the groups was significant (p < 0.05).

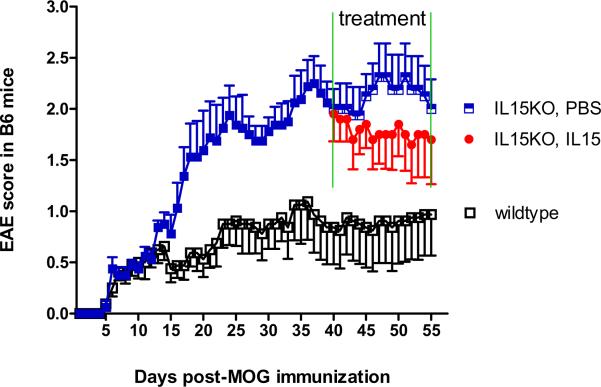

Fig. 6.

IL15 treatment of normal and IL15 KO mice after EAE induction. (A) In the SJL/J mice, IL15 treatment (100 ng/day/mouse) was administrated from day 7 to day 14 after EAE induction. The treated mice showed amelioration of their EAE severity. (B) IL15 KO mice displayed significantly deteriorated EAE symptoms compared with control mice (p < 0.01). Moreover, when given continuous IL15 treatment (100 ng/day/mice) from day 40, the IL15 KO mice showed improved EAE symptoms.

In comparison with the B6 wildtype mice receiving MOG + CFA, the IL15 KO mice showed severer weakness and significantly higher EAE scores, although the onset was as early as day 6 in both groups. The difference in the EAE score between the KO and wildtype mice persisted from day 15 to day 40 (p < 0.01). At this time, the KO mice were randomly divided into two groups that received either IL15 (100 ng/mouse/d ip) or PBS for 15 days (day 40–55, 2 wk duration). IL15 treatment tended to reduce the EAE score in the KO mice (Fig. 6B).

4. Discussion

In this study we show that EAE induction resulted in an increase of IL15 production and IL15 receptor expression in the brain, that IL15KO mice have a greater symptomatic deficit, and that IL15 treatment in both early and late stages of EAE progression can modify the disease course and reduce EAE severity. The results indicate that the cerebral IL15 system has immunomodulatory functions in restricting autoimmunity.

The blood concentration of IL15 was significantly higher at the peak of EAE. This is consistent with a previous report that IL15 is increased in serum and cerebrospinal fluid of MS patients (Rentzos et al. 2006). Elevated serum IL15 is also seen in inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory synovitis, psoriasis, diabetes mellitus, bronchial asthma, and autoimmune vasculitis (Budagian et al. 2006). This suggests that IL15 is a weak biomarker for autoimmune diseases. In the hippocampus, both IL2Rβ/IL15Rβ (Petitto and Huang 2001) and the IL2Rγ common chain (Winocur et al. 2005) have a high level of expression shown by in-situ hybridization. Consistent with these reports, qPCR showed that the upregulation of IL15 did not reside mainly at the mRNA level. Rather, IL15 protein expression, seen in neurons in the basal state, was increased at the peak of EAE. IL15 immunoreactivity showed a neuronal distribution in the rostral hippocampus. The differential regulation of IL15 mRNA and protein on day 12 indicates that the changes probably occurred at the level of post-transcriptional processing.

Whereas many studies have focused on disruption of the blood-spinal cord barrier in EAE mice with ascending paralysis, the brain shows specific changes in EAE mice that may represent the underlying mechanisms for the associated depressive-like and sickness behaviors. It is well known that neuroinflammation and autoimmune disorders impair memory and decrease feeding behavior, but specific involvement of the hippocampus in the EAE model or human MS has not been fully investigated. Interestingly, IL15 and IL2 play important roles in hippocampal function. IL2 is enriched in hippocampus and facilitates neurogenesis during development (Araujo et al. 1989;Hanisch and Quirion 1995;Petitto et al. 1998). IL2 KO mice show defective hippocampal structure (Petitto et al. 1999;Beck, Jr. et al. 2002;Beck, Jr. et al. 2005), have increased levels of IL15, IL12, and the chemokines IP-10 and MCP-1, and show greater hippocampal neurogenesis in male mice (Beck, Jr. et al. 2005). The IL2 KO also confers reduced susceptibility to EAE (Petitto et al. 2000). These reports provide a strong basis to focus on the role of IL15 in the hippocampus of EAE mice.

Besides the increase of IL15Rα protein in different neurons in the hippocampus, the three receptor subtypes for IL15 all showed robust upregulation at the mRNA level. IL15Rα mRNA was significantly increased only on day 12 (peak of EAE symptom), whereas IL2Rβ mRNA was increased from day 7 to 16, and IL2Rγ mRNA was increased on day 12 and 16. The co-receptors IL2Rβ and IL2Rγ for IL15 are shared by other cytokines in the same family of four-alpha-helix bundle cytokines. Their longer lasting changes may suggest that the cellular responses to IL2 and perhaps other cognate cytokines are also upregulated. The neuroprotective role of IL15Rα is supported by the observation that IL15RKO mice have five times more motor neuron death after facial nerve axotomy (Huang et al. 2007), and that the serum concentration of IL15 is lower in Alzheimer's disease than in normal or vascular dementia patients (Rentzos et al. 2007).

To determine the functional role of IL15 and its receptors in the progression of EAE, we used two additional models of EAE that have a longer duration of symptoms. Whereas SJL/J mice after PLP + RIBI immunization showed monophasic EAE at day 6 – 22 with a higher score (behavioral deficits, Fig. 1), the model of SJL/J mice immunized with PLP + CFA showed a more protracted disease course and somewhat lower EAE score (Fig. 5A). B6 mice, known to be less susceptible to EAE, require induction by MOG + CFA, and showed an even lower score though the onset was earlier (Fig. 5B), making more apparent the striking increase in symptoms associated with the embryonic deletion of IL 15 after induction of EAE. IL15 treatment was effective in ameliorating the EAE symptoms in both SJL/J mice and IL15KO mice of a B6 genetic background. The treatment effect was evident both early in the disease course and after the symptoms were well established. These results strongly support a beneficial role of IL15 in restricting the autoimmune disease in EAE mice.

As a proinflammtory cytokine, IL15 has been postulated to mediate negative disease-promoting effects in MS (Kivisakk et al. 1998). The unexpected findings of a beneficial role of IL15 in EAE mice are in sharp contrast with that reported in peripheral autoimmune disease. IL15 blockade is considered a potential target for therapeutic intervention; anti-IL15 therapy has shown efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. This includes the use of antibodies against IL15 in a phase II clinical trial of rheumatoid arthritis (Waldmann 2004) and suppression of psoriasis in mice by blockade of IL15 (Villadsen et al. 2003). The differing findings suggest differing roles or doses of IL15 in CNS and peripheral disorders and might even reflect differential functions of subtypes of immune cells in the disease processes. The CNS increase of IL15 in EAE and MS could represent a compensatory mechanism to ameliorate the disease process. Many substances such as insulin, TRH, and bombesin are known to exert opposite effects in the periphery and CNS (Banks and Kastin 1993).

We have shown that IL15 receptors in cerebral endothelial cells composing the BBB can be upregulated by tumor necrosis factor α (TNF) (Pan et al. 2009), and that the lipopolysaccharide model of altered innate immunity is associated with an increase of IL15 permeation across the BBB (Pan et al. 2008b). By comparison, EAE is associated with a reduction of IL15 permeation from blood to the CNS (Hsuchou et al. 2009b). The immunoprotective effect of IL15 might involve multiple targets and cellular mechanisms, including promotion of T cell and natural killer (NK) cell proliferation (Grabstein et al. 1994;Carson et al. 1994), and CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T (Treg) cell activation or expansion. Treg has been recognized as a negative regulator of MS pathogenesis (Kohm et al. 2002;Viglietta et al. 2004). IL15 can stimulate Treg proliferation, reduce their apoptosis, and maintain their suppressive function in vitro (Wang et al. 2008;Ben et al. 2009). Thus, it is possible that the effect of exogenous IL15 treatment has an indirect effect on CNS disease processes, and that part of the exacerbation of EAE in the IL15KO mice is mediated by peripherally derived immune cytokines and other cytokines.

IL15 now can be added to the short list of protective cytokines in EAE (interferon α, leukemia inhibitory factor, IL10, and IL2). This assumes added importance because IL15 is usually considered a proinflammatory cytokine (Gomez-Nicola et al. 2006). Another unique feature is that the IL15 system is ubiquitously present in the CNS, suggestive of an important function in neuropathology. Even in the absence of inflammatory or autoimmune challenges, mice without IL15Rα show distinctive changes in metabolism, locomotor control, and thermoregulation (He et al. 2009). These mice also show memory and emotional deficits (He et al. 2010). The absence of IL15 induces depressive-like behavior in these KO mice, and IL15 treatment reverses it (Wu X et al., manuscript under review). Thus, the upregulation of the IL15 system in EAE might reflect its essential role in maintaining mood stability and reducing the depression commonly seen in MS patients.

In summary, EAE was associated with region- and time-specific upregulation of the IL15 system in mouse brain. Unexpectedly, IL15 treatment by peripheral injection reduced the severity of EAE, and IL15 KO mice showed lower EAE scores. The results indicate an important role of IL15 in restricting the progression of EAE.

Acknowledgements

Grant support was provided by National Institutes of Health (NS62291, NS45751, and DK54880).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 't Hart BA, Amor S. The use of animal models to investigate the pathogenesis of neuroinflammatory disorders of the central nervous system. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2003;16:375–383. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000073940.19076.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo DM, Lapchak PA, Collier B, Quirion R. Localization of interleukin-2 immunoreactivity and interleukin-2 receptors in the rat brain: interaction with the cholinergic system. Brain Res. 1989;498:257–266. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Kastin AJ. Physiological consequences of the passage of peptides across the blood-brain barrier. Rev. Neurosci. 1993;4:365–372. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.1993.4.4.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck RD, Jr., King MA, Huang Z, Petitto JM. Alterations in septohippocampal cholinergic neurons resulting from interleukin-2 gene knockout. Brain Res. 2002;955:16–23. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03295-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck RD, Jr., Wasserfall C, Ha GK, Cushman JD, Huang Z, Atkinson MA, Petitto JM. Changes in hippocampal IL-15, related cytokines, and neurogenesis in IL-2 deficient mice. Brain Res. 2005;1041:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben AM, Belhadj HN, Moes N, Buyse S, Abdeladhim M, Louzir H, Cerf-Bensussan N. IL-15 renders conventional lymphocytes resistant to suppressive functions of regulatory T cells through activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway. J. Immunol. 2009;182:6763–6770. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Jerez C, Plaza JF, Masjuan J, Orensanz LM, Alvarez-Cermeno JC. Increased levels of IL-15 mRNA in relapsing--remitting multiple sclerosis attacks. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;128:90–94. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budagian V, Bulanova E, Paus R, Bulfone-Paus S. IL-15/IL-15 receptor biology: a guided tour through an expanding universe. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17:259–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson WE, Giri JG, Lindemann MJ, Linett ML, Ahdieh M, Paxton R, Anderson D, Eisenmann J, Grabstein K, Caligiuri MA. Interleukin (IL) 15 is a novel cytokine that activates human natural killer cells via components of the IL-2 receptor. J. Exp. Med. 1994;180:1395–1403. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, O'Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008;9:46–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Nicola D, Doncel-Perez E, Nieto-Sampedro M. Regulation by GD3 of the proinflammatory response of microglia mediated by interleukin-15. J. Neurosci. Res. 2006;83:754–762. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshen I, Kreisel T, Ounallah-Saad H, Renbaum P, Zalzstein Y, Ben-Hur T, Levy-Lahad E, Yirmiya R. A dual role for interleukin-1 in hippocampal-dependent memory processes. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:1106–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabstein KH, Eisenman J, Shanebeck K, Rauch C, Srinivasan S, Fung V, Beers C, Richardson J, Schoenborn MA, Ahdieh M. Cloning of a T cell growth factor that interacts with the beta chain of the interleukin-2 receptor. Science. 1994;264:965–968. doi: 10.1126/science.8178155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanisch UK, Quirion R. Interleukin-2 as a neuroregulatory cytokine. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 1995;21:246–284. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(95)00015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart BA, Bauer J, Muller HJ, Melchers B, Nicolay K, Brok H, Bontrop RE, Lassmann H, Massacesi L. Histopathological characterization of magnetic resonance imaging-detectable brain white matter lesions in a primate model of multiple sclerosis: a correlative study in the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis model in common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) Am. J. Pathol. 1998;153:649–663. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65606-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Hsuchou H, Wu X, Kastin AJ, Khan RS, Pistell PJ, Wang W-H, Feng J, Li Z, Guo X, Pan W. Interleukin-15 receptor is essential to facilitate GABA transmission and hippocampal dependent memory. J. Neurosci. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6160-09.2010. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Wu X, Khan RS, Kastin AJ, Cornélissen GG, Hsuchou H, Robert B, Halberg F, Pan W. IL15 receptor deletion results in circadian changes of locomotor and metabolic activity. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s12031-009-9319-z. Epub PMID: 20012227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsuchou H, He Y, Kastin AJ, Tu H, Markadakis EN, Rogers RC, Fossier PB, Pan W. Obesity induces functional astrocytic leptin receptors in hypothalamus. Brain. 2009a;132:889–902. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsuchou H, Pan W, Wu X, Kastin AJ. Cessation of blood-to-brain influx of interleukin-15 during development of EAE. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2009b;29:1568–1578. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Ha GK, Petitto JM. IL-15 and IL-15R alpha gene deletion: effects on T lymphocyte trafficking and the microglial and neuronal responses to facial nerve axotomy. Neurosci Lett. 2007;417:160–164. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.01.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivisakk P, Matusevicius D, He B, Soderstrom M, Fredrikson S, Link H. IL-15 mRNA expression is up-regulated in blood and cerebrospinal fluid mononuclear cells in multiple sclerosis (MS) Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;111:193–197. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00478.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohm AP, Carpentier PA, Anger HA, Miller SD. Cutting edge: CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells suppress antigen-specific autoreactive immune responses and central nervous system inflammation during active experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2002;169:4712–4716. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YB, Satoh J, Walker DG, Kim SU. Interleukin-15 gene expression in human astrocytes and microglia in culture. NeuroReport. 1996;7:1062–1066. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199604100-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losy J, Niezgoda A, Zaremba J. IL-15 is elevated in sera of patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Folia Neuropathol. 2002;40:151–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Mohlstrom C, Uittenbogaart C, Kermaniarab V, Ellison GW, Myers LW. Response to and production of interleukin 2 by peripheral blood and cerebrospinal fluid lymphocytes of patients with multiple sclerosis. J. Immunol. 1984;133:1931–1937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W, Banks WA, Kennedy MK, Gutierrez EG, Kastin AJ. Differential permeability of the BBB in acute EAE: enhanced transport of TNF-α. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:E636–E642. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.271.4.E636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W, Hsuchou H, He Y, Sakharkar A, Cain C, Yu C, Kastin AJ. Astrocyte Leptin Receptor (ObR) and Leptin Transport in Adult-Onset Obese Mice. Endocrinology. 2008a;149:2798–2806. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W, Hsuchou H, Yu C, Kastin AJ. Permeation of blood-borne IL15 across the blood-brain barrier and the effect of LPS. J Neurochem. 2008b;106:313–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05390.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W, Yu C, Hsuhou H, Khan RS, Kastin AJ. Cerebral microvascular IL15 is a novel mediator of TNF action. J. Neurochem. 2009;111:819–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06371.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pashenkov M, Mustafa M, Kivisakk P, Link H. Levels of interleukin-15-expressing blood mononuclear cells are elevated in multiple sclerosis. Scand. J. Immunol. 1999;50:302–308. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petitto JM, Huang Z. Cloning the full-length IL-2/15 receptor-beta cDNA sequence from mouse brain: evidence of enrichment in hippocampal formation neurons. Regul. Pept. 2001;98:77–87. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(00)00229-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petitto JM, Huang Z, Raizada MK, Rinker CM, McCarthy DB. Molecular cloning of the cDNA coding sequence of IL-2 receptor-gamma (gammac) from human and murine forebrain: expression in the hippocampus in situ and by brain cells in vitro. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1998;53:152–162. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petitto JM, McNamara RK, Gendreau PL, Huang Z, Jackson AJ. Impaired learning and memory and altered hippocampal neurodevelopment resulting from interleukin-2 gene deletion. J. Neurosci. Res. 1999;56:441–446. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990515)56:4<441::AID-JNR11>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petitto JM, Streit WJ, Huang Z, Butfiloski E, Schiffenbauer J. Interleukin-2 gene deletion produces a robust reduction in susceptibility to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in C57BL/6 mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2000;285:66–70. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00996-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak Y, Orion E, Goshen I, Ovadia H, Yirmiya R. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis-associated behavioral syndrome as a model of `depression due to multiple sclerosis'. Brain Behav. Immun. 2002;16:533–543. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(02)00010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentzos M, Cambouri C, Rombos A, Nikolaou C, Anagnostouli M, Tsoutsou A, Dimitrakopoulos A, Triantafyllou N, Vassilopoulos D. IL-15 is elevated in serum and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. Sci. 2006;241:25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentzos M, Paraskevas GP, Kapaki E, Nikolaou C, Zoga M, Tsoutsou A, Rombos A, Vassilopoulos D. Circulating interleukin-15 in dementia disorders. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2007;19:318–325. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2007.19.3.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viglietta V, Baecher-Allan C, Weiner HL, Hafler DA. Loss of functional suppression by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Exp. Med. 2004;199:971–979. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villadsen LS, Schuurman J, Beurskens F, Dam TN, Dagnaes-Hansen F, Skov L, Rygaard J, Voorhorst-Ogink MM, Gerritsen AF, van Dijk MA, Parren PW, Baadsgaard O, van de Winkel JG. Resolution of psoriasis upon blockade of IL-15 biological activity in a xenograft mouse model. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:1571–1580. doi: 10.1172/JCI18986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldmann TA. Targeting the interleukin-15/interleukin-15 receptor system in inflammatory autoimmune diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6:174–177. doi: 10.1186/ar1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Takeuchi H, Sonobe Y, Jin S, Mizuno T, Miyakawa S, Fujiwara M, Nakamura Y, Kato T, Muramatsu H, Muramatsu T, Suzumura A. Inhibition of midkine alleviates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis through the expansion of regulatory T cell population. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:3915–3920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709592105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winocur G, Greenwood CE, Piroli GG, Grillo CA, Reznikov LR, Reagan LP, McEwen BS. Memory impairment in obese Zucker rats: an investigation of cognitive function in an animal model of insulin resistance and obesity. Behav Neurosci. 2005;119:1389–1395. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.5.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zozulya AL, Ortler S, Lee J, Weidenfeller C, Sandor M, Wiendl H, Fabry Z. Intracerebral dendritic cells critically modulate encephalitogenic versus regulatory immune responses in the CNS. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:140–152. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2199-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]