Abstract

Systemic sclerosis has the highest case-specific mortality of any of the autoimmune rheumatic diseases as well as causing major morbidity. It is a major clinical challenge and one that has previously provoked substantial nihilism due to the limited therapeutic options available and perceived lack of evidence for clinical effectiveness of those treatments that are currently in use. However this situation is changing and there are emerging data supporting efficacy for some treatment approaches for this patient group together with a growing number of exciting potential novel approaches to treatment that are moving into the clinical arena. Some of the recent clinical trials are reviewed and discussed in detail.

Keywords: systemic scleroderma, systemic sclerosis, treatment, rapidly progressing systemic sclerosis, review, clinical trials, treatment

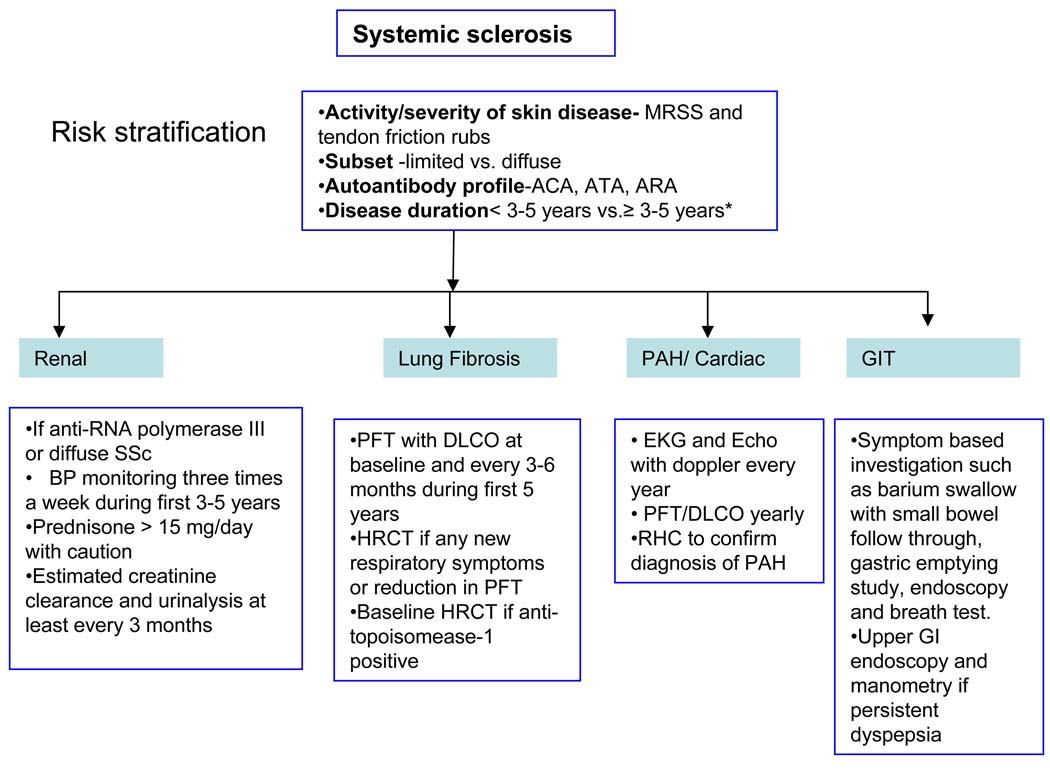

The major mortality and much of the morbidity of SSc arises through the development of specific complications of the disease including organ based complications such as cardiopulmonary, renal or gastrointestinal manifestations. The frequency and diverse nature of these complications makes systematic assessment and long term follow up essential to good management of SSc. In addition it is essential that accurate baseline assessment of each case is undertaken to define the extent and pattern of disease and to ascertain the likelihood of progression and risk of severe life-threatening complications. Current approaches to assessment and follow up of severe progressive SSc are summarized below.

Assessment of skin disease

Skin fibrosis is a hallmark feature of SSc. Depending on the extent of skin sclerosis the disease is classified into two major subsets – limited cutaneous SSc (lcSSc) when only skin distal to the elbows and knees (with or without face involvement) is affected and diffuse cutaneous SSc (dcSSc) when the skin thickening includes distal areas and also spreads proximally. These patients are also at risk from other complications of SSc.

The majority of cases of rapidly progressive SSc can be classified to the diffuse subset as there is almost always progression to involve proximal limbs or trunk. Nevertheless it is important to consider that almost all cases will at some point have had less extensive skin involvement. For this reason determining the duration of disease, as defined by the first non-Raynaud disease sign or symptom (such as joint pain and swelling, reflux disease, digital ulcer etc) is critical to assessment of cases of SSc. In addition, tendon friction rubs (TFR) a “leathery crepitus” on palpation of knees, wrists, fingers, and ankles during motion is a significant predictor of developing dcSSc (1). Before presenting the evidence for efficacy of the different agents in treatment of scleroderma skin disease, it is important to consider its relation to internal organ involvement in SSc patients and current methods of assessment that have shed insight onto the natural history of skin sclerosis in dcSSc.

Patients with early diffuse SSc tend to have worsening of their skin thickness over the first 1–3 years after disease onset. During this phase of skin thickening, patients develop internal organ involvement (Table 1). In addition, worsening skin thickness is a predictor of morbidity and mortality. Therefore, current efforts are directed in early diagnosis of internal organ involvement and institute therapies. Figure A summarizes our current diagnostic approach in patients with SSc. After 1–3 years of worsening skin thickening, the skin tends to soften irrespective of treatment(2;3). This has been noted both in clinical practice and randomized controlled trials of diffuse SSc(4). Although softening of skin is associated with improved survival(5), this relationship between change in skin score and internal organ involvement is not straightforward which questions its validity as a primary outcome in trials assessing treatment efficacy. With that background, the modified Rodnan skin score (MRSS), a measure of skin thickness has been used as the primary outcome measure in most of these trials, as it is feasible, reliable, valid, and responsive to change in multicenter clinical trials(6) and is routinely performed in clinical practice at scleroderma centers. It assesses skin thickness in 17 body surface areas (face, chest, and abdomen, and right and left fingers, hands, forearms, upper arms, thighs, lower legs and feet)(7). Each area was assessed for thickness on a 0 to 3 scale (0 = normal, 1 = mild but definite thickening, 2 = moderate skin thickening and 3 = severe skin thickening). The total score (the sum of scores from all 17 body areas) ranged from 0 to 51; a score of >=20 is associated with poor prognosis.

Table 1.

Diffuse vs. Limited Scleroderma -Distinguishing Features-

| Diffuse | Limited |

|---|---|

|

|

FIG A. Diagnostic approach in patients with systemic sclerosis.

•Subset classification important as severe progressive skin disease associates with increased risk of renal crisis and cardiac involvement

•Disease duration reflects risk of major internal organ disease. Renal crisis in early dcSSc and severe lung fibrosis more likely in severe SSc of early onset; both less likely after 5 years. Gastrointestinal involvement, cardiac disease and PAH can occur in early and later disease.

*Disease duration is variable in an individual pt and continue monitoring till stabilization/improvement of skin dz

Although the MRSS is widely used as a clinical and research tool for the assessment of skin disease in SSc there have been attempts to develop new tools and to correlate these novel approaches with skin score as well as structure and histology of skin as observed on biopsy specimens. Assessment of biomechanical properties has shown promise including the assessment of skin elasticity using BTC-2000 suction device(8). Similarly it has been demonstrated that changes in skin score correlate well with durometer measurements(9). The use of these devices may provide a simple way of assessing skin hardness while having the advantage of potentially less variability between observers and the development of a continuous variable rather than the categorical skin score.

High frequency ultrasound provides a tool to measure skin thickness and has been shown to reflect skin score(10) while providing potential information about biochemical composition of skin and the degree of oedema. These tools are likely to be more applicable to clinical trials than for routine practice.

Bottom Line

The extent of skin involvement differentiates limited vs. diffuse SSc. MRSS continues to be primary outcome measure to assess skin involvement in clinical trials and practice but disease duration needs to be considered when interpreting change in MRSS in dcSSc. Worsening skin thickness is a predictor of morbidity and mortality.

Renal involvement in rapidly progressive SSc

The pattern of kidney manifestations in SSc may be divided into scleroderma renal crisis (SRC), chronic kidney disease and inflammatory renal pathology. However, SRC is the most important renal complication in SSc and occurs in 10–15% of patients with dcSSc and very rarely (1–2%) in lcSSc (11). The mortality among patients with SRC remains high despite the early treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (12), and clear evidence that ACEi therapy has a dramatic beneficial effect on early death rate. The typical features of SRC comprise new onset of significant systemic hypertension (>150/85 mmHg) and decreased renal function (≥30% reduction in calculated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR]). In approximately 20% of patients, the diagnosis of SRC precedes the diagnosis of SSc; therefore early identification of SSc is highly important(11). Other clinical features of SRC include either non-specific systemic symptoms (headaches, fever, malaise, exertional breathlessness) or signs and symptoms suggestive of end-organ damage (hypertensive retinopathy and encephalopathy, pulmonary oedema, acute renal failure). Arrhythmia, myocarditis, and pericarditis, if present, may indicate poorer prognoses. Microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia (MAHA) and thrombocytopenia are common, estimated to be 60% and 50% respectively but coagulopathy is rare(13). Urinalysis commonly demonstrates non-nephrotic range proteinuria and haematuria, with granular casts evident on microscopy. Risk factors that may predict development of SRC have been identified. Patients with early dcSSc are at greatest risk with the estimated median duration of SSc at SRC diagnosis is only 8 months. Rapidly progressive skin thickening and tendon friction rubs represent other independent risk factors. An estimated 66% SRC develop within a year of diagnosis of SSc(11). SRC has been linked to corticosteroid therapy; many patients have received corticosteroids prior to presentation. A recent history of high-dose corticosteroid use (e.g. prednisolone or equivalent at >15 mg/day) may precede SRC diagnosis(13) and studies suggest that even low-doses of corticosteroids may be associated with SRC(14). Although there is no evidence of a causal effect, this observation necessitates extreme caution in using corticosteroids in dcSSc. The incidence of extensive skin and renal disease are also significantly higher in patients with SSc-specific anti-RNA polymerase antibodies (I and III)(15), which were present in 59% of SRC patients in one cohort [10]. This represents the single strongest clinical association of any scleroderma specific autoantibody. Commercial anti-RNA polymerase antibodies III ELISA methods are now available which makes identification of these antibodies simpler.

Bottom Line

Consider anti-RNA polymerase antibodies III in all patients with dcSSc. Encourage three times/ week blood pressure monitoring at home in early dcSSc (first 3 years). Moderate-to-high dose prednisone (> 15 mg/day) should be used with caution and ACE inhibitors should be instituted immediately after the diagnosis of renal crisis.

Interstitial pulmonary fibrosis

The commonest forms of interstitial lung disease in SSc are histologically classified as usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) and non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). Investigation and assessment of interstitial lung disease in SSc focuses on early detection, severity assessment, and determination of progression that is best performed by regular pulmonary function tests (PFT). High resolution CT (HRCT) imaging remains the most valuable tool for detection of early lung fibrosis(16). Interstitial lung disease develops insidiously and generally progresses to fibrosis. Majority of decline in lung function occurs in a small (15%) of patients and in those, majority decline during the first 4 years of disease. Because lung fibrosis is irreversible, early diagnosis is vital. The most common initial symptoms are breathlessness, especially on exertion, and a dry cough. Chest pain is infrequent and hemoptysis rare; either one suggests the presence of additional pathology. On physical examination the most frequent finding is bilateral inspiratory crackles at the lung bases. Radiographic features consist of reticulonodular shadowing, usually symmetrical and most marked at the lung bases. However, because the chest radiograph is an insensitive indicator of early pulmonary fibrosis, it should be used only as an initial screen or to exclude infection or aspiration. Mildly symptomatic SSc patients often have normal chest radiographs despite interstitial lung disease, and PFT’s are more discriminatory. The single-breath diffusion capacity (DLCO) is abnormal in over 70 per cent of patients with dcSSc, including asymptomatic patients with no complaints and an unremarkable chest radiograph(17). A reduction in DLCO is the earliest detected abnormality in SSc patients who go on to develop interstitial lung disease. The combination of normal lung volumes but reduced gas transfer in the face of normal chest imaging is suggestive of pulmonary vascular disease(18).

The application of HRCT has been of immense value for definition and assessment of diffuse lung diseases, and has revealed the character and distribution of fine structural abnormalities not visible on chest radiographs(19). Pleural disease and mediastinal lymphadenopathy may also be identified. It is important to perform HRCT in both prone and supine positions, particularly in patients with early SSc, in order to exclude the contribution of gravity to the radiographic appearances from vascular and interstitial pooling in the dependent areas. In addition to identifying early disease, HRCT can be used to quantify the extent and delineate the pattern of lung abnormality. Recently published data from a well characterized cohort of cases of SSc associated lung fibrosis has used threshold analysis to determine the association between extent of disease on a formally scored HRCT and outcome. This has led to the development of a simple staging algorithm that utilizes simple lung function variables and rapid evaluation of HRCT to discriminate mild form extensive lung fibrosis(20). Those in the mild group require close observation but not necessarily intervention with currently available immunosuppressive agents (see below). In the future it is likely that markers of epithelial damage such as DTPA clearance or serum KL-6 will also be useful in stratifying cases of lung fibrosis in SSc and determining the likelihood of progression although brochoalveolar lavage does not appear to add to information from lung function or HRCT(21).

Bottom Line

PFT with DLCO should be performed at baseline and every 3–6 months during first 4 years of disease, irrespective of limited or diffuse SSc. HRCT of lungs is a useful tool to characterize fibrosis as recent studies showed a positive association of degree of baseline lung fibrosis and subsequent decline in FVC% predicted and mortality. Brochoalveolar lavage is not useful in clinical care.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension

Pulmonary arterial hypertension, defined as an elevation in the mean pulmonary artery pressure > 25 mmHg at rest with normal pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) on right heart catheterization, occurs in both limited and diffuse cutaneous forms of SSc, and has major mortality. The outcome in SSc-associated pulmonary hypertension is considerably worse than that of idiopathic pulmonary hypertension(22). This may reflect co-morbidity or differences in underlying pathogenetic mechanisms. In SSc, PAH due to intrinsic fibroproliferative abnormalities in the pulmonary vasculature, pathologically indistinguishable from idiopathic PAH, is most common, with a prevalence of approximately 10–15%. It is important to consider that left heart disease, diastolic dysfunction, severe systemic hypertension and pulmonary hypertension in association with pulmonary interstitial fibrosis may also occur in SSc. However, PAH in SSc also occurs in the context of pulmonary fibrosis, and typical histological appearance of PAH can be found in lung biopsies from SSc patients with lung fibrosis. Indeed, it has been suggested that it is coexistent vasculopathy that determines outcome and survival in many cases of SSc-associated pulmonary fibrosis (23). Although considered a late complication, recent data shows PAH is associated with both early and late SSc(24).

Pulmonary arterial hypertension may remain asymptomatic until quite advanced. The initial symptoms include exertional breathlessness, and less often chest pain or syncope. In patients with SSc, PAH is typically discovered during regular monitoring with PFT, Doppler-echocardiography and ECG examinations. An isolated reduction in DLCO with preservation of lung volumes (FVC/DLCO ratio> 1.4–1.6) is suggestive of PAH(18). Definitive diagnosis requires exclusion of thromboembolic disease by ventilation: perfusion lung scan, spiral CT scan or pulmonary angiography, and hemodynamic demonstration of a mean pulmonary artery pressure >25 mmHg at rest. There is a strong correlation between peak pulmonary artery pressure estimated by Doppler-echocardiography and direct measurements at right heart catheterization, except when pulmonary artery pressures are in the 30–50 mmHg range (25). Cardiac catheterization is essential because it allows the recognition of pulmonary venous hypertension and the precise determination of pulmonary vascular resistance, cardiac output (cardiac index) and pulmonary artery pressures. Serum levels of the N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) may be helpful for screening and monitoring PAH. The levels of serum BNP correlate with survival in patients with SSc-associated PAH (26). Treatment options ofr PAH in SSc are discussed below, together with the results of recent randomized controlled trials that have included cases of PAH-SSc.

Bottom Line

High index of suspicion is required in SSc. Echocardiogram with Doppler is a good screening tool but associated with false negative (in early PAH) and false positive (in pulmonary fibrosis) rates. BNP or NT-Pro-BNP is a useful biomarker. Isolated decline in DLCO< 55% and/or FVC/DLCO% ratio of >1.4 to 1.6 is a specific predictor of PAH. RHC is required to confirm the diagnosis.

Cardiac involvement

Cardiac involvement is a major factor determining mortality in SSc. As with other complications it is associated particularly with rapidly progressive dcSSc but current limitations in detection and diagnosis mean that the precise frequency of significant cardiac involvement in SSc has been difficult to ascertain(27). Moreover, one potential consequence of cardiac involvement is reduction in the ability to cope well with intercurrent haemodynamic of cardiac stress such as that due to electrolyte disturbance, fluid shift or acidosis so that these other complications become much more severe. In contrast to myocardial involvement, abnormalities of the pericardium are relatively easy to detect by virtue of the formation of a pericardial effusion. Up to 35% of SSc patients are found to have hemodynamically insignificant effusions. Larger effusions are less frequent. Pericardial effusions in SSc are often associated with complications such as PAH and SRC, where they may precede the onset of renal failure.

Myocardial involvement may be due to myocardial ischaemia, fibrosis and myocarditis. Potential mechanisms for ischemic damage include coronary arterial vasospasm, small vessel disease and occlusive coronary artery disease. However, histological examination of the coronary arteries in SSc has not shown excess fibromuscular hypertrophy. Moreover, the frequency of angiographically-proven coronary artery disease does not appear to be increased(28) although recent data showed increased asymptomatic coronary calcium, especially in patients with lcSSc compared to age-and sex- matched controls(29) . An association between cardiac mortality and myositis has been demonstrated in SSc, raising the possibility of associated myocarditis. Myocarditis may explain the frequent occurrence of exudative pericardial effusions in SSc, endocardial lesions found on histology, and ECG evidence of conducting tissue damage. Although at present there are few published data suggesting low grade myocarditis leading to diastolic dysfunction and the other cardiac abnormalities in SSc, we have described excess of troponin T release(27). An attractive hypothesis is that low grade intermittent myocardial inflammation causes subtle myocardial damage in the first few years when the disease process is most active, leading to mild fibrosis with diastolic dysfunction in later stages. Gated MRI may be a useful tool for detecting myocardial fibrosis, and for quantitation of abnormal contraction or relaxation(30). The frequent occurrence of diffuse interfascicular fibrosis in SSc may be challenging to detect by current imaging methods. Tissue Doppler studies and cardiac MRI together with more advanced echocardiographic methods are likely to be valuable in defining abnormalities in SSc cardiac structure and function but at present the definition of clinically important abnormalities is more challenging. Post-mortem studies consistently point to discrepancy between cardiac involvement and clinical and imaging abnormalities.

Gastrointestinal manifestations

The gastrointestinal tract is the most commonly involved internal organ system (approximately 90%) in SSc, and gastro-oesophageal manifestations are the most frequent(31). Despite major morbidity, only a minority of cases have life-threatening complications. Severe involvement of the small intestine typically occurs in patients with established SSc. At its most severe, small intestinal involvement leads to recurrent episodes of intestinal pseudo-obstruction due to ileus with dilated small bowel loops. Small bowel bacterial overgrowth complicating hypomotility results in recurrent diarrhea and bloating, and in more severe cases leads to malabsorption, weight loss, malnutrition and cachexia. The classic symptoms are change in bowel pattern, with frequent loose, floating, foul-smelling stools, and abdominal distension. Management of advanced bowel disease includes rotating antibiotics, stimulation of intestinal motility with prokinetic agents such as erythromycin or domperidone, and supplemental alimentation. In the short term, nocturnal feeding to maintain nutrition and a nasogastric or nasojejunal feeding tube may be effective. Longer term nutritional supplementation requires percutaneous jejunostomy, or gastroscopy if stomach emptying is not delayed. When malnutrition is the major problem, intermittent parenteral hyperalimentation may be required(32). Recent EULAR/ EUSTAR guidelines recommend PPI should be used for the prevention of SSc-related GERD, oesophageal ulcers and strictures; prokinetic drugs should be used for the management of SSc-related symptomatic motility disturbances (dysphagia, GERD, early satiety, bloating, pseudo-obstruction, etc); and when malabsorption is caused by bacterial overgrowth, rotating antibiotics may be useful(33).

Bottom Line

GIT involvement in SSc is very common and has a major impact on quality of life. A proactive approach is suggested. The cornerstones of GIT examination are imaging studies and laboratory tests; physical examination of the GIT system yields little information(34). For motility disorders a barium contrast study is the preferred radiographic procedure, and for assessment of mucosal disease, endoscopy is the preferred test. Body weight or BMI should be collected in patients with SSc.

Autoantibodies in assessment of SSc

The role of autoantibodies in SSc is still unclear, although there is a growing body of evidence that antibodies are potential markers of organ-based complications that impact on disease outcome. Easier assays and more systematic evaluation offers real potential in risk stratification of SSc cases since most patients can be defined by their serological profile at initial presentation(35). The three most frequent SSc associated antibodies - anti-centromere antibodies (ACA), anti-topoisomerase (ATA) and anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies (ARA) are found in over 50% of patients with the disease. They are highly specific and generally mutually exclusive. Strong associations between antibody type and pattern of organ complications and survival in SSc patients exist and it is now widely accepted that autoantibodies are stronger predictors of disease outcome and organ involvement compared to disease subset, making antibody testing essential for disease assessment. Due to the specific organ disease associations, autoantibodies can be used also as predictors of survival in SSc patients. For example, ATA positive subjects have been demonstrated to have significantly higher mortality compared to other autoantibodies, which is related to the strong association with interstitial lung disease. Antibodies associated with features of overlap syndromes, such as anti-Pm/Scl, anti-U1RNP and anti-Ku generally predict milder disease.

Controlled Studies recently reported for systemic sclerosis

Overall

High dose immunosuppressive therapy (HDIT) and Autologous Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT)

Patients with severe SSc have been evaluated using HSCT. The underlying hypothesis is that upfront intensive immunosuppression would ablate immune responses driving disease activity, and the infused hematopoietic progenitors, depleted in vitro of disease causing mature lymphoid elements (using CD34-selection), may then be able to generate a new nonautoreactive immune system(36). Inclusion criteria included: ≤ 65 years, early (≤ 4 years), diffuse SSc and significant visceral organ involvement, including progressive pulmonary disease with a decrease of at least 15% in FVC or DLCO in the previous 6 months with any skin involvement(36;37). The eligibility criteria selected patients with a mortality risk from SSc of approximately 50% at 5 years with conventional treatment. Of the 34 patients, 27 survived 1-year. Of these 17 patients had sustained responses at a median follow-up of 4 (range, 1 to 8) years with stabilization of their FVC and DLCO. There were 12 deaths during the study (transplantation- related, 8; SSc-related, 4). The estimated progression-free survival was 64% at 5 years.

Based on these and other preliminary findings, a multicenter, randomized trial of CYC versus HSCT in Europe is underway: Autologous Stem cell transplantation in Scleroderma (ASTIS). As of July 2008, 122 patients have been randomized in 25 centers from 10 countries and allocated to either high dose immunoablation followed by autologous stem cell transplantation or cyclophosphamide pulse therapy (http://www.astistrial.com/ASTISnews.HTM accessed August 17th, 2009). All patients were enrolled because of severe SSc with extensive skin thickening and involvement of heart, lung or kidneys.

Another NIH-sponsored study (Scleroderma: Cyclophosphamide or Transplant [SCOT; www.sclerodermatrial.org]) will randomize 113 patients to either HSCT or CYC (57 randomized as of August 18th, 2009) with a primary composite end point (death, organ failure, change FVC, SHAQ and RSS) at 54 months post randomization. Patients with early diffuse SSc (≤ 5 years) and lung or renal involvement are eligible to participate.

Bottom Line

HDIT and autologous HSCT is an option for patients with early dcSSc with progressive pulmonary fibrosis and/or renal involvement. Patients should be referred to ASTIS or SCOT studies to assess the efficacy and safety of HSCT vs. high-dose monthly CYC.

Skin

dcSSc is a subset of SSc in which more rapid change in skin involvement occurs, making it more feasible to study in relatively short clinical trials. It is for this reason that dcSSc has been the focus of investigation in many clinical trials(38;39). As described before, MRSS, a measure of skin thickness has been used as the primary outcome measure in most of these trials (6). Recent studies have assessed different biological agents for the treatment of skin thickness.

Anti-TGFβ1 antibody

A human recombinant neutralizing TGFβ1 antibody was tested in a multi-center phase I/II trial(40). The study recruited patients with early diffuse SSc (< 18 months; mean disease duration of 6–9 months) and was designed as a safety study. Patients were randomly assigned to the placebo group or to 1 of 3 TGFβ1 antibody treatment groups: 10 mg/kg, 5 mg/kg, and 0.5 mg/kg. Infusions were given on day 0 and weeks 6, 12, and 18. There were four deaths in the TGFβ1 antibody group and no deaths in the placebo group. All deaths in the study were attributed to the progression of SSc. There were no differences in the TGFβ1 antibody vs. placebo in the MRSS or in changes in either the FVC or DLCO.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec) is currently approved for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia and gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Imatinib mesylate is a small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor that binds to the c-abl and blocks efficiently its tyrosine kinase activity; c-abl is an important downstream signaling molecule of TGFb(41;42). In addition, imatinib mesylate interferes with PDGF signaling by blocking the tyrosine kinase activity of PDGF receptors. In the tight skin 1 mouse model and bleomycin-induced dermal fibrosis, imatinib prevented fibrosis and induced regression of established fibrosis. In another proof-of-concept study, 2 patients with early diffuse SSc had a clinical improvement in MRSS and the immunohistochemical analyses of skin biopsy specimens demonstrated reductions of phosphorylated PDGFR-beta and Abl with imatinib therapy. Recently reported preliminary outcome from a number of prospective pilot studies suggest that imatinib treatment in SSc is generally tolerated but there is no unequivocal message of significant efficacy.

Recombinant human relaxin

Relaxin is a naturally occurring protein with anti-fibrotic properties: it downregulates collagen production and increase collagen degradation (43). A phase II randomized controlled trial suggested that relaxin was safe and clinically effective in improving skin disease and functional disability(44). To replicate this finding, subjects with diffuse SSc (disease duration of ≤ 5 years) were enrolled in a RCT evaluating the safety, efficacy and dose-response effect of continuous subcutaneously infused recombinant human relaxin(45). 231 patients were randomized in the 24-week study to receive either relaxin (25 µg/kg/day, 10 µg/kg/day) or placebo in a 2:1:2 ratio for 24 weeks. The primary outcome measure, the MRSS, was similar between the 3 groups at baseline and at weeks 4, 12, and 24 (P=NS). Secondary outcome such as functional disability was similar in all 3 groups and the forced vital capacity significantly decreased in the relaxin groups (p< 0.04). The discontinuation of relaxin (both doses) at week 24 led to statistically significant declines in creatinine clearance and serious renal adverse events (defined as either doubling of baseline serum creatinine, renal crisis, or grade 3 or 4 hypertension), which were seen in 7 patients who had received relaxin therapy but in none who had received placebo (p=0.04). With a renewed interest in relaxin for management of heart failure, pre eclampsia, or induction of labor, patients may require close follow-up after patients cease relaxin therapy.

Oral bovine type I collagen

This phase III RCT assessed the efficacy and safety of oral bovine type I collagen (500 ug/day) vs. placebo (46). The premise was that oral collagen will induce immune tolerance and will lead to improvement in skin thickness as assessed by MRSS. This trial randomized 168 diffuse SSc patients with baseline disease duration of up to 10 years. The results showed no statistically significant difference in the change in the skin score at month 12 or 15 in the two groups. However, in a subanalysis of the available data at month 15, the CI-treated group of patients with late-phase dcSSc (>3 –10 years) experienced a significant reduction in the MRSS compared with that in the placebo-treated patients with late-phase dcSSc (change in MRSS at month 15; P =0.0063). The authors postulated that immune-mediated fibrosis in the early phase of the disease may be less susceptible to modulation by CI than are those in the late phase of the disease. Future study is being planned to assess the late phase diffuse SSc.

Other therapies

Investigators have recently assessed infliximab and rituximab in open-labeled trials without much clinically beneficial effect on MRSS. Rapamycin was compared to methotrexate in a single blind trial and was shown to have similar efficacy and toxicity.

Bottom Line

Two randomized controlled trials have shown that low-dose methotrexate (MTX) is more effective than placebo in patients with active SSc in improving skin thickness. Based on these studies, recent EULAR/ EUSTAR guidelines recommend considering the use of MTX in the treatment of skin manifestations in early diffuse SSc (10). Oral cyclophosphamide improved skin thickness in diffuse SSc patients participating in SLS. Other drugs (such as tryosine kinase inhibitors) should be considered investigational at this time.

Lung

Interstitial Lung Disease

Cyclophosphamide

The Scleroderma Lung Study (SLS) was the first randomized controlled trial to demonstrate the effectiveness of cyclophosphamide in improving lung function (FVC % predicted), relative to placebo, at the end of the one-year treatment period (47). Although the physiologic benefits of cyclophosphamide compared to placebo were modest (2.53% improvement in % predicted FVC at 12 months; p<0.03), these results were supported by parallel findings of improvement in patient-reported outcomes, including breathlessness, function (HAQ-DI) and some health-related quality of life measures (48), as well as skin thickness scores. Moreover, extent of fibrosis on the baseline HRCT scan was a significant predictor of worsening FVC in the placebo group and of response to cyclophosphamide (49). In contrast, BAL cellularity at baseline was not a predictor of response (21).

After 1 year of therapy, patients were followed for an additional year with the premise that 1-year of treatment with cyclophosphamide would be sufficient to prevent further disease progression without the need for ongoing immunosuppressive therapy (50). During the year following cessation of randomized treatment in the SLS, the beneficial effects of cyclophosphamide (compared to placebo) on lung function (FVC) continued to increase for an additional 6 months (51). After 18 months, the beneficial effects of the preceding treatment with cyclophosphamide waned so that by the end of the 2-year period, lung function in the two treatment groups was essentially the same (51). During the 2 year follow up, cyclophosphamide was associated with greater adverse events related to microscopic hematuria and leucopenia. However, in all other adverse events, including serious adverse events and death, there were no significant differences.

In an alternative approach, cyclophosphamide was administered by intravenous infusion monthly for 6 months (to minimize the risk of hemorrhagic cystitis associated with the oral route) followed by azathioprine, compared with placebo infusions followed by oral placebo, in 45 patients with active SSc-ILD (52) . The results showed a trend toward a favorable outcome in the actively treated group (p=0.08) while minimizing the toxicity of cyclophosphamide.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors

In an in vitro model of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis c-Abl inhibition by imatinib prevented TGF-beta induced extracellular matrix gene expression, transformation and proliferation of fibroblasts (42). There is an ongoing study assessing safety and efficacy of open-label imitinab in patients with SSc-ILD wherein the inclusion/exclusion criteria are similar to those of the SLS (Clinical Trial Registration Number: NCT00512902). Preliminary data from an ongoing open-label study suggests some stabilization of pulmonary function (Khanna D EULAR 2009). However, a high proportion of patients dropped out due to adverse events. A trial has also been designed to study dasatinib (2nd generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor that also inhibits src-kinase which plays an important role in extracellular matrix protein in dermal fibroblasts (53) in SSc-ILD (Clinical Trial Registration Number: NCT00764309).

Bottom Line

Cyclophosphamide therapy results in stabilization of lung fibrosis and the effect lasts for an additional 6 months. The improvement in lung physiology is associated with improvement in patient-reported outcomes. EULAR/EUSTAR guidelines recommend cyclophosphamide for treatment of SSc-ILD despite its known toxicity. Mycophenolate mofetil(54) and rituximab are investigational therapies at this time and require further studies.

Pulmonary artery hypertension

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a progressive disease that leads to increased pulmonary vascular resistance, compromised vasoreactivity and eventual right heart failure and death. Due to the overlap in the pathophysiology and specific therapeutic interventions , the 2008 Dana Point meeting has classified idiopathic, familial, and CTD (including SSc) under the umbrella of PAH. There are 8 FDA approved therapy for PAH in US. These include 2 endothelin-1 receptor blockers (bosentan [Tracleer®] and ambrisentan [Letaris®]), 2 phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor (sildenafil [Revatio®], and tadalifil (Revatio®), and prostacyclin derivatives (epoprostenol [Flolan ®], Treprostinil [Remodulin ®]).

Management of rapidly progressive SSc

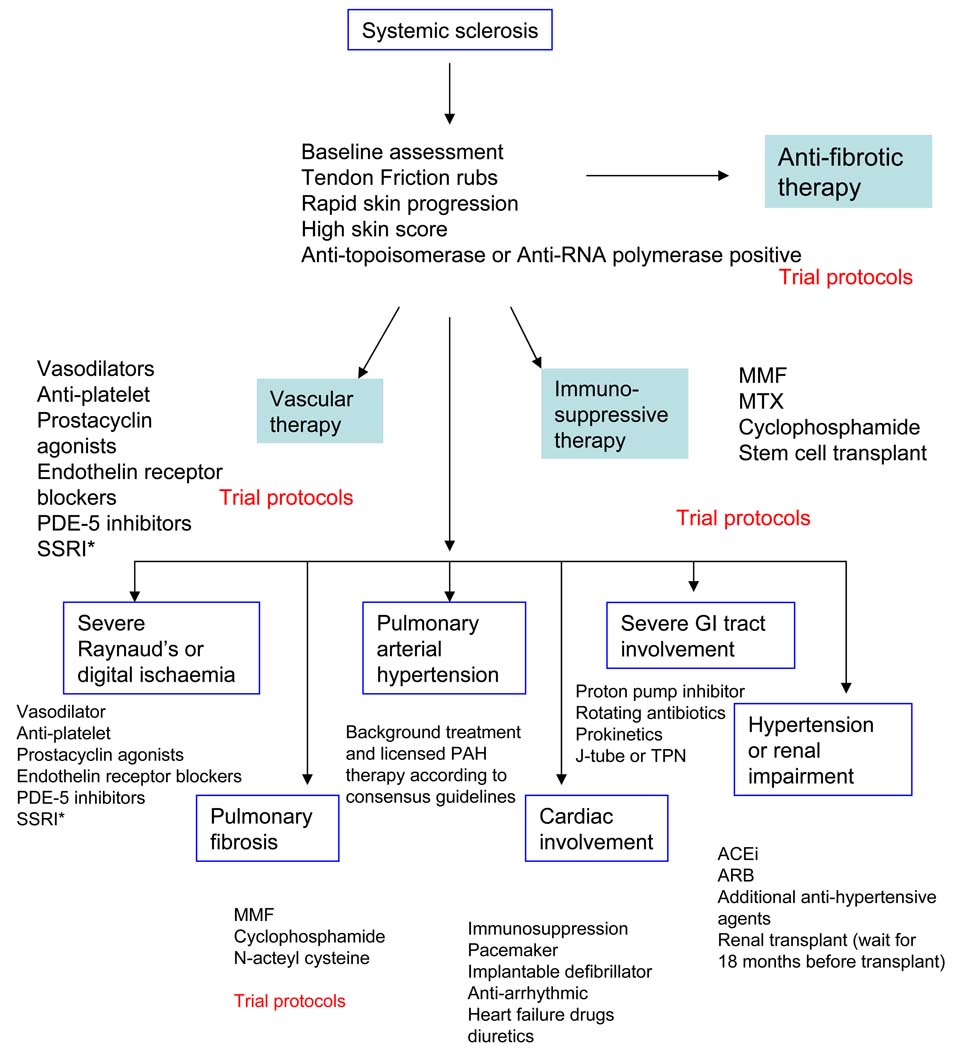

Current understanding of the diverse patterns of disease that fall within the spectrum of scleroderma and specifically within the subgroup of systemic sclerosis necessitates a systematic approach to case assessment and management. This needs to address important issues around likelihood of progression and the detection and appropriate treatment of organ-based complications such as pulmonary arterial hypertension and interstitial lung fibrosis as well as skin sclerosis. The emerging evidence base that underpins current therapy provides support for active treatment in all cases that are severe or progressive. A global approach to management is summarized in the clinical algorithm shown in Figure B. All patients should be considered for ongoing clinical trials. This approach should be considered in the context of more detailed discussion of disease assessment and treatment that is included in this article. Treatment for rapidly progressive SSc is based on skin, heart, lung, renal, GIT, or vascular involvement.

FIG B. Algorithm for treatment of severe progressive systemic sclerosis.

*Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

For skin, first line treatment varies according to local experience and practice but our recommendation is that all cases should be enrolled into clinical trial protocols where possible. Otherwise we recommend initial treatment with immunosuppressive agents and would recommend methotrexate at doses up to 25 mg (oral or subcutaneous) every week with folic acid or treatment with oral mycophenolate mofetil with a target dose of at least 2g daily. If improvement is not seen within 3 to 6 months then we would consider switching between these agents or use of low-dose pulse intravenous CYC. We have used monthly IVIG with success especially in patients with myopathy or inflammatory myositis and some success with anti-thymocyte globulin has been reported although longer term benefit over less intensive treatment regimens is not clear(55).

For ILD, we recommend treatment with pulse CYC at doses of 500–750 mg/ m2 every month. Moderate-to-high dose prednisone has not shown to be effective in treatment of ILD and we discourage this especially due to risk of renal crisis with prednisone. FVC should be assessed every 3–4 months and a decline of > 10% is considered a clinically meaningful decline and should lead to change in therapy. Other choices include mycophenolate mofetil and azathioprine.

For cardiac involvement, the precise management is less clear than for skin and lung. Based upon baseline investigations there should be medical treatment of hemodynamically significant arrhythmias or pericardial effusion (although uncommon – see text above). Our current practice is to use echocardiography to define systolic cardiac function and consider immunosuppressant with pulse CYC if there is impaired LV function (LVEF <50%). In addition if there are documented tachyarrhythmias or conduction defects implantable defibrillator or pacemaker devices may be considered. Cardiac MRI is increasingly used to assess patients with suspected myocardial involvement in SSc, as discussed above. The place of this together with serum markers such as troponin remains to be established.

For renal involvement, diagnosis of renal crisis should lead to initiation of ACE-inhibitor with a goal to normalize blood pressure. If inadequate BP control is achieved, add calcium-channel blocker and/or furosemide. Patients should be dialyzed, if needed. If on dialysis, wait 18 months before considering a renal transplant.

In GIT involvement, most common cause of continuing weight loss is malabsorption syndrome related to small bowel bacterial overgrowth and gastroparesis. Treatment with rotating antibiotics and prokinetics is necessary. In resistant cases, daily subcutaneous octreotide (50 mg twice to three times a day) may be helpful. In addition, some patients may need percutaneous gastric or jejunal feeding or parenteral nutrition.

For severe Raynaud’s phenomenon (cold blue finger) and digital necrosis, we initiate intravenous iloprost or another prostacyclin in the hospital setting. PDE-5 inhibitors may be used in addition to prostacyclin therapy. We have also used anti-platelet therapy and performed angiogram if we suspect vasculitis/thromboembolic event. Bosentan reduced new digital ulcer formation in two large controlled trials and may be considered for preventative therapy, and is a licensed therapy in the EU. It is probably most appropriate in those cases with severe ongoing digital ulcer disease(56).

Concluding comments

As can be seen in this review there have been substantial recent advances in the field of SSc in terms of disease assessment and therapy. This has included a greater appreciation of the strengths and limitations of current assessment techniques and a growing appreciation of the clinical diversity of SSc and heterogeneity in terms of disease progression. Thus it is clear that in those cases that are at highest risk of life-threatening complications or progression that an aggressive approach to treatment is mandatory. This may well include high intensity immunosuppression and in the future the use of biological agents that target key pathogenic mediators or pathways. It is also clear that some cases of SSc follow a more benign or slowly progressive course and vigilant monitoring with timely intervention to tackle organ-based complication such as pulmonary arterial hypertension or scleroderma renal crisis is the cornerstone of managing these cases. Therefore the immediate challenges for clinicians treating cases of SSc include identification of the most progressive cases as well as better definition of the clinical benefit from intervention both within formal clinical trials but also from careful observation of well-characterized clinical cohorts. Survival has improved in SSc but there is still scope for progress and this includes attention to the substantial disease burden beyond those complications that are immediately life-threatening.

Clinical Practice Points

Treatment of early SSc requires risk stratification.

Rapidly progressive scleroderma requires frequent physician visits and screening tests to evaluate for internal organ involvement.

Effective treatments are available for rapidly progressive skin disease, interstitial lung disease and pulmonary hypertension, if diagnosed early.

Patients should be referred to Scleroderma Centers to participate in multiple ongoing clinical trials

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Steen VD, Medsger TA., Jr The palpable tendon friction rub: an important physical examination finding in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(6):1146–1151. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199706)40:6<1146::AID-ART19>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nihtyanova SI, Brough GM, Black CM, Denton CP. Mycophenolate mofetil in diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis--a retrospective analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46(3):442–445. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shand L, Lunt M, Nihtyanova S, Hoseini M, Silman A, Black CM, et al. Relationship between change in skin score and disease outcome in diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis: application of a latent linear trajectory model. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(7):2422–2431. doi: 10.1002/art.22721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amjadi S, Maranian P, Furst DE, Clements PJ, Wong WK, Postlethwaite AE, et al. Course of the modified Rodnan skin thickness score in systemic sclerosis clinical trials: Analysis of three large multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(8):2490–2498. doi: 10.1002/art.24681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steen VD, Medsger TA., Jr Improvement in skin thickening in systemic sclerosis associated with improved survival. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(12):2828–2835. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200112)44:12<2828::aid-art470>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clements P, Lachenbruch P, Siebold J, White B, Weiner S, Martin R, et al. Inter and intraobserver variability of total skin thickness score (modified Rodnan TSS) in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 1995;22(7):1281–1285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clements PJ, Lachenbruch PA, Seibold JR, Zee B, Steen VD, Brennan P, et al. Skin thickness score in systemic sclerosis: an assessment of interobserver variability in 3 independent studies. J Rheumatol. 1993;20(11):1892–1896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balbir-Gurman A, Denton CP, Nichols B, Knight CJ, Nahir AM, Martin G, et al. Non-invasive measurement of biomechanical skin properties in systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(3):237–241. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.3.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merkel PA, Silliman N, Denton CP, Clements P, Emery P, et al. Validity, Reliability, and Feasibility of Durometer Measurements of Scleroderma Skin Disease in a Multicenter Treatment Trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:S419. doi: 10.1002/art.23564. Ref Type: Abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akesson A, Forsberg L, Hederstrom E, Wollheim F. Ultrasound examination of skin thickness in patients with progressive systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 1986;27(1):91–94. doi: 10.1177/028418518602700117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penn H, Howie AJ, Kingdon EJ, Bunn CC, Stratton RJ, Black CM, et al. Scleroderma renal crisis: patient characteristics and long-term outcomes. QJM. 2007;100(8):485–494. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcm052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steen VD, Costantino JP, Shapiro AP, Medsger TA., Jr Outcome of renal crisis in systemic sclerosis: relation to availability of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(5):352–357. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-5-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teixeira L, Mouthon L, Mahr A, Berezne A, Agard C, Mehrenberger M, et al. Mortality and risk factors of scleroderma renal crisis: a French retrospective study of 50 patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(1):110–116. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.066985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeMarco PJ, Weisman MH, Seibold JR, Furst DE, Wong WK, Hurwitz EL, et al. Predictors and outcomes of scleroderma renal crisis: the high-dose versus low-dose D-penicillamine in early diffuse systemic sclerosis trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(11):2983–2989. doi: 10.1002/art.10589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bunn CC, Denton CP, Shi-Wen X, Knight C, Black CM. Anti-RNA polymerases and other autoantibody specificities in systemic sclerosis. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37(1):15–20. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Au K, Khanna D, Clements PJ, Furst DE, Tashkin DP. Current concepts in disease-modifying therapy for systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease: lessons from clinical trials. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2009;11(2):111–119. doi: 10.1007/s11926-009-0016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wells AU, Hansell DM, Rubens MB, King AD, Cramer D, Black CM, et al. Fibrosing alveolitis in systemic sclerosis: indices of lung function in relation to extent of disease on computed tomography. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(7):1229–1236. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199707)40:7<1229::AID-ART6>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robertson L, Pignone A, Kowal-Bielecka O, Fiori G, Denton CP, Matucci-Cerinic M. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in systemic sclerosis: diagnostic pathway and therapeutic approach. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(6):804–807. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.026427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desai SR, Veeraraghavan S, Hansell DM, Nikolakopolou A, Goh NS, Nicholson AG, et al. CT features of lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis: comparison with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. Radiology. 2004;232(2):560–567. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2322031223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goh NS, Desai SR, Veeraraghavan S, Hansell DM, Copley SJ, Maher TM, et al. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: a simple staging system. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(11):1248–1254. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200706-877OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strange C, Bolster MB, Roth MD, Silver RM, Theodore A, Goldin J, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage and response to cyclophosphamide in scleroderma interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(1):91–98. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200705-655OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denton CP, Humbert M, Rubin L, Black CM. Bosentan treatment for pulmonary arterial hypertension related to connective tissue disease: a subgroup analysis of the pivotal clinical trials and their open-label extensions. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(10):1336–1340. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.048967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Condliffe R, Kiely DG, Peacock AJ, Corris PA, Gibbs JS, Vrapi F, et al. Connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern treatment era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(2):151–157. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200806-953OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hachulla E, Launay D, Mouthon L, Sitbon O, Berezne A, Guillevin LF, et al. Is Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Really a Late Complication of Systemic Sclerosis? Chest. 2009 doi: 10.1378/chest.08-3042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mukerjee D, St George D, Coleiro B, Knight C, Denton CP, Davar J, et al. Prevalence and outcome in systemic sclerosis associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: application of a registry approach. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(11):1088–1093. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.11.1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams MH, Handler CE, Akram R, Smith CJ, Das C, Smee J, et al. Role of N-terminal brain natriuretic peptide (N-TproBNP) in scleroderma-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(12):1485–1494. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kahan A, Coghlan G, McLaughlin V. Cardiac complications of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48 Suppl 3:iii45–iii48. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akram MR, Handler CE, Williams M, Carulli MT, Andron M, Black CM, et al. Angiographically proven coronary artery disease in scleroderma. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45(11):1395–1398. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khurma V, Meyer C, Park GS, McMahon M, Lin J, Singh RR, et al. A pilot study of subclinical coronary atherosclerosis in systemic sclerosis: Coronary artery calcification in cases and controls. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(4):591–597. doi: 10.1002/art.23540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karwatowski SP, Chronos NA, Sinclaire H, Forbat SM, St John Sutton MG, Black C, et al. Effect of systemic sclerosis on left ventricular long-axis motion and left ventricular mass assessed by magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2000;2(2):109–117. doi: 10.3109/10976640009148679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sjogren RW. Gastrointestinal features of scleroderma. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1996;8(6):569–575. doi: 10.1097/00002281-199611000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sallam H, McNearney TA, Chen JD. Systematic review: pathophysiology and management of gastrointestinal dysmotility in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23(6):691–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kowal-Bielecka O, Landewe R, Avouac J, Chwiesko S, Miniati I, Czirjak L, et al. EULAR recommendations for the treatment of systemic sclerosis: a report from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research group (EUSTAR) Ann Rheum Dis. 2009 doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.096677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khanna D. Gastrointestinal involvement in systemic sclerosis. In: Font J, Ramos-Casals M, Rodes J, editors. Digestive involvement in systemic autoimmune diseases. Elsevier; 2008. pp. 51–69. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steen VD. Autoantibodies in systemic sclerosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;35(1):35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McSweeney PA, Nash RA, Sullivan KM, Storek J, Crofford LJ, Dansey R, et al. High-dose immunosuppressive therapy for severe systemic sclerosis: initial outcomes. Blood. 2002;100(5):1602–1610. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nash RA, McSweeney PA, Crofford LJ, Abidi M, Chen CS, Godwin JD, et al. High-dose immunosuppressive therapy and autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for severe systemic sclerosis: long-term follow-up of the US multicenter pilot study. Blood. 2007;110(4):1388–1396. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-072389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clements PJ, Hurwitz EL, Wong WK, Seibold JR, Mayes M, White B, et al. Skin thickness score as a predictor and correlate of outcome in systemic sclerosis: high-dose versus low-dose penicillamine trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(11):2445–2454. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200011)43:11<2445::AID-ANR11>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khanna D, Merkel PA. Outcome measures in systemic sclerosis: an update on instruments and current research. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2007;9(2):151–157. doi: 10.1007/s11926-007-0010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Denton CP, Merkel PA, Furst DE, Khanna D, Emery P, Hsu VM, et al. Recombinant human anti-transforming growth factor beta1 antibody therapy in systemic sclerosis: A multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled phase I/II trial of CAT-192. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;56(1):323–333. doi: 10.1002/art.22289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Distler JH, Distler O. Imatinib as a novel therapeutic approach for fibrotic disorders. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48(1):2–4. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daniels CE, Wilkes MC, Edens M, Kottom TJ, Murphy SJ, Limper AH, et al. Imatinib mesylate inhibits the profibrogenic activity of TGF-beta and prevents bleomycin-mediated lung fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(9):1308–1316. doi: 10.1172/JCI19603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Samuel CS, Hewitson TD. Relaxin in cardiovascular and renal disease. Kidney Int. 2006;69(9):1498–1502. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seibold JR, Korn JH, Simms R, Clements PJ, Moreland LW, Mayes MD, et al. Recombinant human relaxin in the treatment of scleroderma. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(11):871–879. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-11-200006060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khanna D, Clements PJ, Furst DE, Korn JH, Ellman M, Rothfield N, et al. Recombinant human relaxin in the treatment of systemic sclerosis with diffuse cutaneous involvement: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(4):1102–1111. doi: 10.1002/art.24380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Postlethwaite AE, Wong WK, Clements P, Chatterjee S, Fessler BJ, Kang AH, et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral type I collagen treatment in patients with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis: I. Oral type I collagen does not improve skin in all patients, but may improve skin in late-phase disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(6):1810–1822. doi: 10.1002/art.23501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements PJ, Goldin J, Roth MD, Furst DE, et al. Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(25):2655–2666. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khanna D, Yan X, Tashkin DP, Furst DE, Elashoff R, Roth MD, et al. Impact of oral cyclophosphamide on health-related quality of life in patients with active scleroderma lung disease: Results from the scleroderma lung study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(5):1676–1684. doi: 10.1002/art.22580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements PJ, Goldin J, Roth MD, Furst DE, et al. Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(25):2655–2666. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martinez FJ, McCune WJ. Cyclophosphamide for scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(25):2707–2709. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe068095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements PJ, Roth MD, Furst DE, Silver RM, et al. Effects of 1-year treatment with cyclophosphamide on outcomes at 2 years in scleroderma lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(10):1026–1034. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200702-326OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hoyles RK, Ellis RW, Wellsbury J, Lees B, Newlands P, Goh NS, et al. A multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of corticosteroids and intravenous cyclophosphamide followed by oral azathioprine for the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis in scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(12):3962–3970. doi: 10.1002/art.22204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Akhmetshina A, Dees C, Pileckyte M, Maurer B, Axmann R, Jungel A, et al. Dual inhibition of c-abl and PDGF receptor signaling by dasatinib and nilotinib for the treatment of dermal fibrosis. FASEB J. 2008;22(7):2214–2222. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-105627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gerbino AJ, Goss CH, Molitor JA. Effect of mycophenolate mofetil on pulmonary function in scleroderma-associated interstitial lung disease. Chest. 2008;133(2):455–460. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Herrick A, Lunt M, Whidby N, Ennis H, Silman A, McHugh N, Herrick Ariane L., Lunt Mark, Whidby Nina, Ennis Holly, Silman Alan, McHugh Neil, Denton Christopher P, et al. J Rheumatol. 2009. Obervational study of treatment oucome in early diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis. J Rheum - in press (2009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Korn JH, Mayes M, Matucci CM, Rainisio M, Pope J, Hachulla E, et al. Digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: prevention by treatment with bosentan, an oral endothelin receptor antagonist. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(12):3985–3993. doi: 10.1002/art.20676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]