Abstract

Background

In the tephritids Ceratitis, Bactrocera and Anastrepha, the gene transformer provides the memory device for sex determination via its auto-regulation; only in females is functional Tra protein produced. To date, the isolation and characterisation of the gene transformer-2 in the tephritids has only been undertaken in Ceratitis, and it has been shown that its function is required for the female-specific splicing of doublesex and transformer pre-mRNA. It therefore participates in transformer auto-regulatory function. In this work, the characterisation of this gene in eleven tephritid species belonging to the less extensively analysed genus Anastrepha was undertaken in order to throw light on the evolution of transformer-2.

Results

The gene transformer-2 produces a protein of 249 amino acids in both sexes, which shows the features of the SR protein family. No significant partially spliced mRNA isoform specific to the male germ line was detected, unlike in Drosophila. It is transcribed in both sexes during development and in adult life, in both the soma and germ line. The injection of Anastrepha transformer-2 dsRNA into Anastrepha embryos caused a change in the splicing pattern of the endogenous transformer and doublesex pre-mRNA of XX females from the female to the male mode. Consequently, these XX females were transformed into pseudomales. The comparison of the eleven Anastrepha Transformer-2 proteins among themselves, and with the Transformer-2 proteins of other insects, suggests the existence of negative selection acting at the protein level to maintain Transformer-2 structural features.

Conclusions

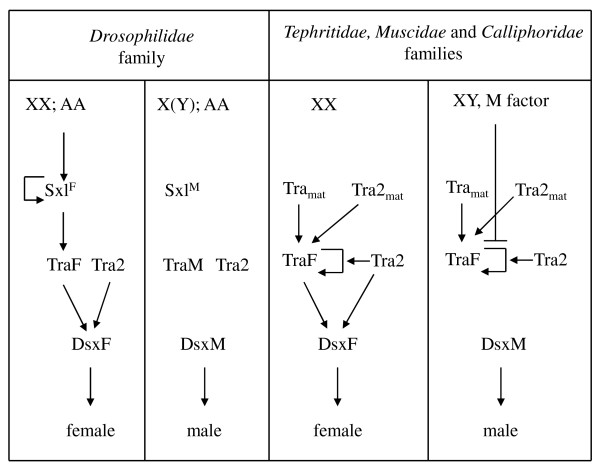

These results indicate that transformer-2 is required for sex determination in Anastrepha through its participation in the female-specific splicing of transformer and doublesex pre-mRNAs. It is therefore needed for the auto-regulation of the gene transformer. Thus, the transformer/transfomer-2 > doublesex elements at the bottom of the cascade, and their relationships, probably represent the ancestral state (which still exists in the Tephritidae, Calliphoridae and Muscidae lineages) of the extant cascade found in the Drosophilidae lineage (in which tra is just another component of the sex determination gene cascade regulated by Sex-lethal). In the phylogenetic lineage that gave rise to the drosophilids, evolution co-opted for Sex-lethal, modified it, and converted it into the key gene controlling sex determination.

Background

Sex determination refers to the developmental programme that commits the embryo to following either the male or the female pathway. The past few years have seen a great amount of interest in the evolution of developmental mechanisms at the genetic and molecular levels, and in determining the evolutionary processes by which these mechanisms came into existence. In this respect, sex determination is a process that seems to be exceptionally suitable for comparative study, given the great variety of mechanisms that exist. Indeed, sex determination has long been of major interest not only as a developmental process but also because of the evolutionary problem it poses - a problem that can only be solved by identifying and comparing the genetic structures of sex determination pathways. Molecular genetic technologies now allow such comparisons to be made. In addition, sex determination in the reference system of insects - that of Drosophila melanogaster - is known in fine detail, making truly informative comparisons possible.

The characterisation of the sex determination genes in D. melanogaster has shown that their control during development is governed by the sex-specific splicing of their products (reviewed in [1]). The product of a gene controls the sex-specific splicing of the pre-mRNA from the downstream gene in the genetic cascade. Sex-lethal (Sxl) is at the top of this cascade and acts as the memory device for female sexual development via its auto-regulatory function: its product controls the splicing of its own pre-mRNA [2,3]. In addition, Sxl controls the splicing of the pre-mRNA from the downstream gene transformer (tra) [4-6]. The Tra product and the product of the constitutive gene transformer-2 (tra-2) control the sex-specific splicing of pre-mRNA from the gene doublesex (dsx) [7-10], which is transcribed in both sexes but gives rise to two different proteins, DsxF and DsxM [11,12]. These are transcription factors that impose female and male sexual development respectively via the sex-specific regulation of the so-called sexual cytodifferentiation genes.

Genes homologous to the sex determination genes of D. melanogaster have been sought in other insects (reviewed in [13]). In the tephritid fruit flies, the gene Sxl has been characterised in Ceratitis capitata [14] and in Bactrocera oleae [15], tra has been characterised in C. capitata [16], B. oleae [17] and in twelve Anastrepha species [18], and dsx has been characterised in C. capitata [19], B. oleae [15] and in eleven Anastrepha species [20,21].

The tephritid Sxl gene is not regulated in a sex-specific fashion, and therefore the same Sxl transcript encoding the functional Sxl protein is found in both males and females [14,15]. Thus, in the tephritids, Sxl does not appear to play the key discriminating role (memory device) in sex determination that it plays in Drosophila.

As in the drosophilids, the tephritid tra gene is constitutively expressed in both sexes and its primary transcript shows sex-specific alternative splicing. However, whereas in the drosophilids Sxl regulates tra, in the tephritids this gene appears to have an auto-regulatory function that produces functional Tra protein specifically in females. The gene tra in the tephritids has male-specific exons that contain translation stop codons. The incorporation of these exons into the mature tra mRNA in males determines that, in this sex, a truncated, non-functional Tra protein is produced. In females, the male-specific exons are spliced out because of the presence of Tra protein [16-18]. The presence of putative Tra-Tra2 binding sites in the male-specific exons and in the surrounding introns may suggest that the Tra2 protein participates in the tra auto-regulatory function. The introduction of Ceratitis [16] or Bactrocera [17]tra-dsRNA into Ceratitis or Bactrocera embryos, respectively, results in the destruction of endogenous tra function in both species and the subsequent complete transformation of females into pseudomales. Together, these results support the proposal of Pane et al. [16] that the key regulatory role played by tra is to act as the memory device for sex determination via its auto-regulatory function.

The tephritid gene dsx codes for male- and female-specific RNAs, which encode the male-specific and female-specific Dsx proteins [15,19-21]. Putative Tra-Tra2 binding sites have been found in the female-specific exon, suggesting that, as in Drosophila, male-specific splicing represents the default mode and that female-specific splicing requires Tra protein, which would only be present in females.

So far, the isolation and characterisation of the gene transformer-2 (tra-2) in the tephritids has been only performed in C. capitata [22,23]. This gene is transcribed in both sexes. The injection of Ceratitis tra-2 dsRNA into Ceratitis embryos results in the transformation of genotypically female embryos into adult pseudomales, highlighting the role of tra-2 in Ceratitis sex determination [23]. Its function is required for the female-specific splicing of dsx and tra pre-mRNA; it therefore participates in tra auto-regulatory function [23].

The study of the evolution of the sex determination gene cascade (i.e., the genes and their interactions) requires its characterisation in different species. To better analyse the evolution of the gene tra-2, and more specifically its pivotal role in tra auto-regulation in the tephritids, its characterisation was undertaken in eleven tephritid species belonging to the less extensively analysed genus Anastrepha. The present analysis therefore included Anastrepha obliqua, A. amita and A. sororcula, plus the four closely related species of the so-called Anastrepha fraterculus complex - A. sp.1 aff. fraterculus, A. sp.2 aff. fraterculus, A. sp.3 aff. fraterculus and A. sp.4 aff. fraterculus [24,25], all of which belong to the fraterculus group [26] - along with A. serpentina (serpentina group), A. striata and A. bistrigata (striata group) and A. grandis (grandis group) [26].

Firstly, the gene tra-2 in the reference species A. obliqua was isolated and its molecular organisation, expression pattern and encoded product studied. Secondly, the tra-2 ORFs in the other Anastrepha species were identified, and a comparative analysis of all the known insect Tra2 proteins undertaken. Thirdly, its function in sex determination was studied by following the sexual development (at the morphological, chromosome and molecular levels) of Anastrepha embryos in which endogenous tra-2 function was destroyed by the injection of tra-2 dsRNA. Finally, the phylogeny of tra-2 in these species and in other insects was investigated.

Results

The molecular organisation of tra-2 in Anastrepha obliqua, and its expression

The first step in the isolation of the A. obliqua tra-2 gene (Aotra2) was to perform RT-PCR on total RNA from female adults. Reverse transcription was performed using the primer oligo-dT, while two nested PCR reactions were performed with three degenerated primers: the nested forward Mar17 and Mar26 primers, and the reverse Tra2-B primer, the latter located in the very well conserved RRM domain of the Tra2 protein (see Materials and Methods and Figure 1A). The first PCR reaction was performed using the pair of primers Mar17 plus Tra2B, the second using Mar26 plus Tra2B. An amplicon of 92 bp was amplified, cloned and sequenced. The conceptual amino acid sequence of this amplicon showed a high degree of similarity with the 3' region of the RRM domain of D. melanogaster Tra2 protein, indicating that a fragment of the putative AoTra2 protein had been isolated.

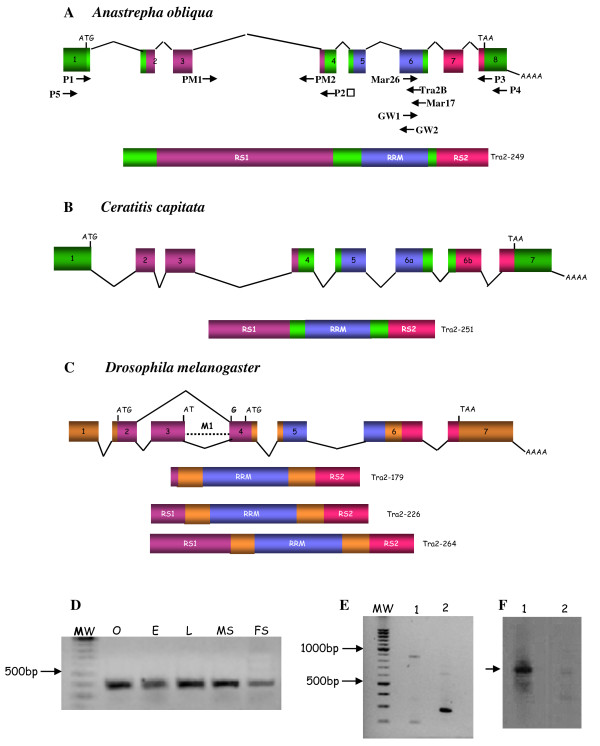

Figure 1.

Comparison of the molecular organisation of the tra-2 of A. obliqua (A), C. capitata (B) and D. melanogaster (C) and their proteins. Exons (boxes) and introns (dashed lines) are not drawn to scale. The numbers inside the boxes indicate the number of the exon. The beginning and the end of the ORF are indicated by ATG and TAA respectively. AAA stands for poly-A(+). (D) Expression of gene tra-2 of A. obliqua. RT-PCR analyses of total RNA from ovaries (O), embryos (E), from male and female larvae (L), male soma (head plus thorax, MS) and female soma (head plus thorax, FS). (E) Expression of gene tra-2 of A. obliqua. RT-PCR analysis of total RNA from A. obliqua testis. Lane 1 corresponds to PCR with primers PM1 and P2; lane 2 corresponds to PCR with primers P1 and P2 (see location of primers in Figure 1A). (F) Southern-blot corresponding to the gel shown in (E) and hybridisation with a probe specific for intron 3 of A. obliqua. The arrow marks the hybridisation to the higher band in lane 1 of Figure 1E. The size of the mRNAs encoding the proteins shown in this figure are: 1923 bp for A. obliqua mRNA, 1113 bp for C. capitata mRNA, and 960, 1583 and 1391 bp for D. melanogaster mRNAs tra2-179, tra2-226 and tra2-264, respectively.

To determine the molecular organisation of Aotra2 the following strategy was followed. Firstly, 3'- and 5'-RACE analyses were performed. To this end, specific primers from the amplified sequenced were synthesised (see Materials and Methods). These primers were used in nested PCR reactions involving total RNA from male and female adults. The amplicons, which were the same in both sexes, were then cloned and sequenced.

A GenomeWalker library of A. obliqua was synthesised (see Materials and Methods) and used to perform PCR genome-walking on the genomic DNA of A. obliqua from the initial amplicon towards the 5' and 3' directions (see Materials and Methods for the primers used). The genomic amplicons were cloned and sequenced. The sequences of the genomic fragments thus generated were compared with the A. obliqua male and female cDNA sequences previously determined. In this way, the exon/intron junctions were unambiguously identified.

Figure 1A shows the molecular organisation of Aotra2 and its comparison with that of C. capitata tra-2 (Figure 1B) and D. melanogaster tra-2 (Figure 1C). The transcription unit of Aotra2 was made up of 3635 bp and composed of eight exons and seven introns. The putative translation start site was the last three nucleotides of exon1, and the stop codon was located at 15 nucleotides of the beginning of exon 8. The size of the exons and introns of tra-2 from Anastrepha, Ceratitis and Drosophila is given as additional File 1. The sizes of the mRNAs encoding the Tra2 proteins shown in Figure 1 are given in the legend to this Figure.

The molecular organisation of gene tra-2 in Anastrepha, Ceratitis and Drosophila was very similar. The conceptual translation of the Aotra2 mRNA encoded a protein with an RNA-recognition motif (RRM) flanked by two arginine-serine rich regions (RS) as in Ceratitis and Drosophila. The RS1 domain was encoded in exons 2, 3 and 4, the RRM domain in exons 5 and 6, and the RS2 domain in exons 7 and 8 in Anastrepha and 6b and 7 in Ceratitis and Drosophila. The putative Aotra2 protein should have some additional amino acids at the amino-terminal end preceding the RS1 domain.

In D. melanogaster, tra-2 gives rise to three mRNAs (tra2-226, tra2-264 and tra2-179) by alternative splicing pathways and alternative promoters, which encode three distinct isoforms of the Tra2 protein [27,28]. As in the case of other dipterans C. capitata [23], Musca domestica [29] and Lucilia cuprina [30], only a single tra2 mRNA was detected in A. obliqua. This was confirmed by overlapping PCR on total RNA of males and females using the primers shown in Figure 1A.

The expression of Aotra2 was studied by performing RT-PCR on total RNA from a mixture of male plus female embryos, from a mixture of male plus female larvae at different developmental stages, from the heads plus thoraces of male and female adults (separately), and from adult ovaries. The primers used were GW1 from exon 1 and P4 from exon 8 (see Figure 1A). In all cases, a fragment of 368 bp was amplified (Figure 1D). This was cloned and sequenced confirming that it corresponded to the expected Aotra2 fragment. Negative controls in all these PCR reactions produced no amplicons (see Materials and Methods). These results indicate that the gene Aotra2 is expressed at all developmental stages and during adult life in both sexes, including the ovaries of adult females, what suggests that tra-2 has a maternal expression.

In the male germ line of D. melanogaster, the Tra2 protein acts negatively on the splicing of its primary transcript promoting the inclusion of intron M1 in the mRNA (see Figure 1C), which encodes a truncated, non-functional Tra2 protein [31]. This aberrant mRNA comprises about 50% of the total tra2 mRNA in the male germ line [32]. This retention of the M1 intron is the mechanism by which the functional Tra2 protein limits its own synthesis since the final amount of this protein is crucial for male fertility [33]. This negative regulation of the Tra2 protein is exerted by its binding to specific ISS-sequences located in intron M1 [34]. The existence of putative Tra2-binding ISS sequences in intron 3 of Aotra2 gene (data not shown) prompted us to investigate whether the mRNA isoform carrying this intron is also significantly produced in the testis of A. obliqua, as a sign that tra-2 negative auto-regulation might exist in the A. obliqua male germ line. To this end, RT-PCR was performed on total RNA from adult testis using the pair of primers P1 from exon 1 and P2 from exon 4. Only a single fragment of 300 bp was amplified that corresponded to the mature mRNA lacking introns 1, 2 and 3 (Figure 1E, lane 2). Notwithstanding, when primers PM1 at the beginning of intron 3 and primer P2 from exon 4 were used for PCR, two bands of about 200 and 900 bp, respectively, were amplified (Figure 1E, lane 1). Negative controls for all these PCR reactions produced no amplicons (see Materials and Methods). The 900 bp fragment might correspond to an mRNA isoform retaining intron 3. To confirm this expectation, a Southern-blot with the RT-PCR products of the two PCR reactions shown in Figure 1E was carried out using a probe corresponding to intron 3 (see Materials and Methods). Only the 900 bp band - not the small 200 bp band - in lane 1 showed positive hybridisation. The 300 bp band in lane 2 did not hybridise as expected since this corresponds to an mRNA lacking intron 3 (Figure 1F). Collectively, these results indicate that the mRNA isoform retaining intron 3 in the male germ line of A. obliqua is very poorly represented, in contrast to that seen in Drosophila and in agreement with which occurs in C. capitata [23] and Musca domestica [29].

The Tra2 protein of A. obliqua and other Anastrepha species

The conceptual translation of the female Aotra2 mRNA showed it to encode a polypeptide of 249 amino acids. It shared the main structural features that characterise the SR protein family, i.e., the RNA-binding motif (RRM) and two RS-domains, which are rich in serine-arginine dipeptides and confer upon these proteins the capacity to interact with others.

To characterise the Tra2 protein of other Anastrepha species, it was assumed that the tra-2 gene of the Anastrepha species studied here had a molecular organisation similar to that of A. obliqua. Under this assumption, RT-PCR analyses of total RNA from female adults were performed. Reverse transcription was performed with the P4 primer located in the 3'UTR region of Aotra2. PCR amplification of the cDNA was undertaken using the pair of primers P5 (from the 5'UTR of Aotra2) plus P4 (see Figure 1A). In this way the whole ORF of the tra-2 gene of all Anastrepha species studied here was amplified, cloned and sequenced. The Tra2 protein of all these Anastrepha species was composed of 249 amino acids. Their degree of similarity (i.e., identical plus conserved amino acids) was extremely high, ranging from 97.2 to 100% (see additional File 2).

The putative Tra2 protein from A. obliqua (used as the reference species), those from the dipterans C. capitata, B. oleae, M. domestica, L. cuprina, D. melanogaster, D. virilis and D. pesudoobscura, that from the lepidopteran Bombyx mori (the silkworm) and from the hymenopteran Apis mellifera (the honeybee), and the Tra2-like protein from the jewel wasp Nasonnia vitripennis (Hymenoptera), were then compared (see additional File 3). The number of amino acids composing these Tra2 proteins varied: the C. capitata and B. oleae had 251 amino acids, M. domestica 232, L. cuprina 271, D. melanogaster, D. virilis and D. pseudoobscura 264, 315 and 248 respectively, B. mori 284, A. mellifera 269, and the N. vitripennis Tra2-like protein 307. These differences are due to changes throughout the Tra2 protein except in the RRM domain, which has the same number of amino acids in all these species.

Similarity was higher among the dipteran Tra2 proteins than between these and the lepipdopteran and hymenopteran Tra2 proteins. The greatest degree of similarity was seen between the tephritid Anastrepha, Ceratitis and Bactrocera Tra2 proteins (83.9 - 86.3%), and between these and those of the Lucilia (57.4 - 58.9%), Musca (48.3 - 57.7%), Drosophila (36.7% - 49.6%) Apis (58.7%) and Bombyx (48.2%) representatives.

The gene tra-2 is required for sex determination in Anastrepha

Outside Drosophila, the function of tra-2 in sex determination has been unambiguously demonstrated in M. domestica [29] and in C. capitata [23] using RNAi procedures. The injection of the Musca and Ceratitis tra-2 dsRNA into their respective embryos, transformed XX flies into pseudomales. This methodology was used to test the requirement of tra-2 for sex determination in Anastrepha. An imperative of this technique is to have markers that allow one to determine whether male survivors really do correspond to XX females that have been transformed into pseudomales by destruction of the endogenous tra-2 gene function, or normal XY males. No Y chromosome molecular markers have yet been identified for Anastrepha flies. Therefore, to ascertain the chromosome constitution of the XX pseudomales, chromosome squashes from the testis of the adults were prepared. The X and the Y chromosome of A. obliqua are not easily distinguished [35], whereas those of A. sp.1 aff. fraterculus can be clearly separated one from another [25] as shown in Figure 2A-C. Hence, embryos of this latter species were used as hosts for the injection of Aotra2 dsRNA since the tra-2 gene of A. obliqua and that of A. sp.1 aff. fraterculus have a very high degree of similarity (see additional Files 3 and 4) (for details of the injection procedure and the analysis of chromosomes see Materials and Methods).

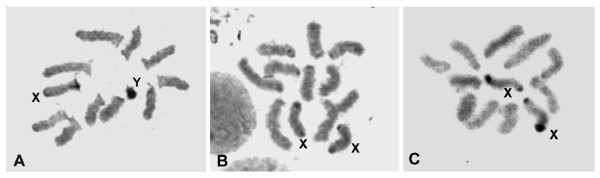

Figure 2.

Chromosomes of A. sp.1 aff. fraterculus. (A) Normal karyotype in a male that developed from an egg injected with buffer; (B) karyotype of a pseudomale that developed from an egg injected with tra-2 dsRNA; and (C) karyotype of a normal female.

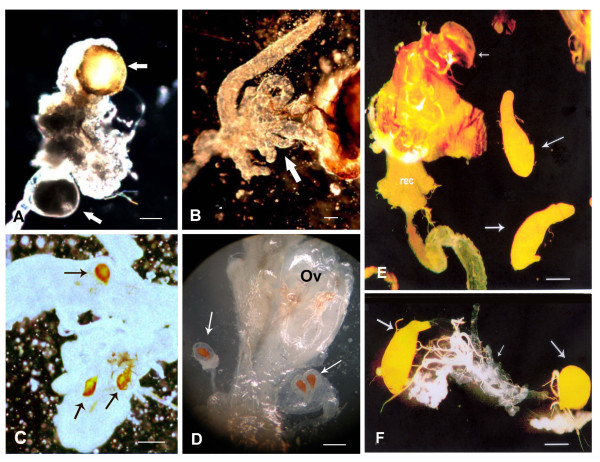

Of the 1450 A. sp.1 embryos experimentally injected with Aotra2 dsRNA, 86 reached the adult stage, and of these 76 were males and 10 were females. However, among the 1000 control injected embryos, 44 survived to adulthood, 21 being males and 23 females. The sex ratio bias associated with the experimental injection cannot be explained by a higher sensitivity of the female embryos to the injection procedure causing their death. Rather, it suggests a transformation of XX female embryos into XX pseudomales caused by a destruction of the endogenous tra-2 function. Testis squashes were prepared for the 76 experimental male survivors; 58 showed cell divisions and the chromosomes were unambiguously identified, showing there to be 47 XY males and 11 XX pseudomales. All these pseudomales showed normal male external terminalia (data not shown). However, after dissection, some of them showed male and female internal genital structures (Figure 3A-C). Others pseudomales had aberrant gonads such as underdeveloped testes, or a well-developed testis plus a poorly developed testis (Figure 3E, F). It was expected that these XX pseudomales would show a change in the splicing pattern of both endogenous tra and dsx pre-mRNAs. This was confirmed by RT-PCR assays on total RNA from the XX pseudomales, from which the gonads were removed.

Figure 3.

Internal terminalia of Anastrepha flies. Parts of the reproductive tract of an intersexual mosaic developed from an injected egg with Aotra2 dsRNA (A-C), and of a normal female (D). In (A) arrows point to two vesicles, one of which is yellow (similar to normal testes). (B) Arrow points to the accessory gland. (C) Arrows point to the spermathecae. (D) Parts of a normal female reproductive tract showing an ovary (ov) and the three regular spermathecae (arrows). Bar = 200 μm. (E, F) Parts of the reproductive tract of A. sp.1 aff. fraterculus males. (E) Testes of a normal male (larger arrows). Small arrow points to the male terminalia; rec, rectum. (F) Asymmetric testes of a male that developed from an egg injected with Aotra2 dsRNA. The right testis is spherical and the other shows the normal elliptical form; the small arrow points to the accessory gland. Bar = 300 μm.

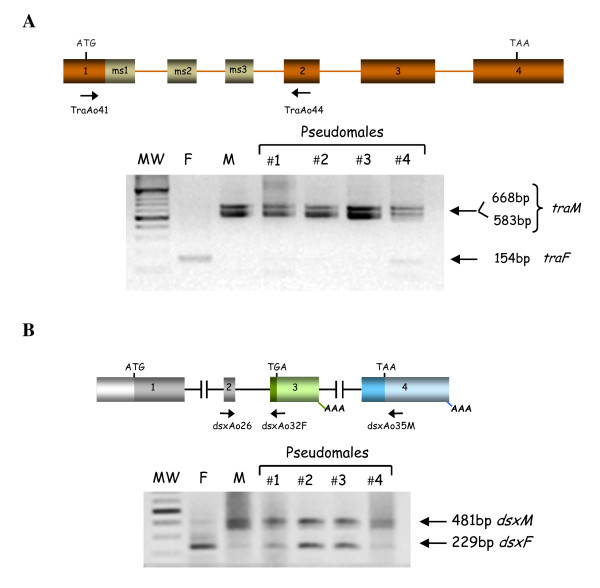

The gene tra of the Anastrepha species is transcribed in both sexes during development and in adult life, but its primary transcript follows alternative splicing routes: the male-exons, which are incorporated into mature mRNA in males are spliced out in females. It encodes three female mRNAs that differ in the length of the 3'-UTR depending on the poly-A(+) signal used, and five different isoforms of male mRNA depending on the male-specific exons included [18]. To analyse the splicing pattern of the endogenous tra pre-mRNA, the pair of primers TraAo41 and TraAo44 were used; these are located in common exons 1 and 2, respectively, which flank the male-specific exons (Figure 4A). Figure 4A shows that in the pseudomales the amplicons corresponding to the male tra mRNA isoform were generated (traces of the female tra mRNA were present in pseudomale #4). Negative controls in all these PCR reactions produced no amplicons (see Materials and Methods). These results indicate that the destruction of the endogenous tra-2 function causes a change in the splicing pattern of the endogenous tra pre-mRNA from the female mode into the male one. Consequently, the Tra2 protein is required for sex determination in Anastrepha through its participation in the female-specific splicing of tra pre-mRNA.

Figure 4.

Analyses of the splicing pattern of tra (A) and dsx (B) pre-mRNAs of A. sp.1 aff. fraterculus in XX pseudomales developed from eggs injected with Aotra2 dsRNA. F and M indicates normal female and male respectively. The sequences of the TraAo41 and TraAo44 primers used, the locations of which are shown with arrows in Figure 4A, are described in Ruiz et al. [18]; the sequences of the dsxA26, dsxAo32F and dsxAo35M primers used, the locations of which is shown with arrows in Figure 4B, are described in Ruiz et al. [21].

The gene dsx of Anastrepha codes for male-and female-specific RNAs, which encode the male-specific DsxM and female-specific DsxF proteins [20,21]. The presence of putative Tra-Tra2 binding sites in the female-specific exon of dsx suggests suggest that, as in Drosophila, male-specific splicing represents the default mode and that female-specific splicing requires the Tra-Tra2 complex. To analyse the splicing pattern of the endogenous dsx pre-mRNA in the XX pseudomales, the pair of primers dsxAo26 in the common exon 2 and dsxAo32F in the female-specific exon were used to detect the female dsxF mRNA, whereas the pair of primers dsxAo26 in the common exon 2 and dsxAo35M in the male-specific exon were used to detect the male dsxM mRNA (Figure 4B). The four analysed XX pseudomales had the dsxM mRNA (Figure 4B), but three of then (#1, 2 and 3) showed also the dsxF mRNA although in different abundance. While in pseudomale #1 the transcript was barely visible, in pseudomales #2 and 3, the amount was almost similar relatively to the corresponding dsxM RNA. Negative controls in all these PCR reactions produced no amplicons (see Materials and Methods). These results indicate that the Tra2 protein is needed for the female-specific splicing of dsx pre-mRNA in Anastrepha.

Phylogeny and molecular evolution of gene tra-2

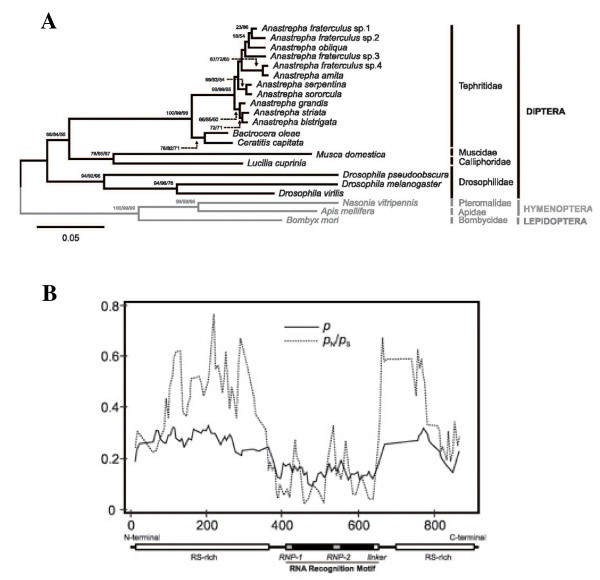

The Tra2 protein sequences determined for different Anastrepha species were aligned with homologous sequences from other tephritids and representative insects in order to reconstruct the evolutionary relationships of this protein in Diptera (see additional File 4), using the Tra2 sequences from B. mori (Lepidoptera), A. mellifera and N. vitripennis (Hymenoptera) as outgroups. The topology obtained for the Tra2 protein phylogeny shown in Figure 5A shows high confidence levels in the groups defined. In the phylogenetic tree, the Tra2 proteins of the Nasonia, Apis and Bombix representatives clustered in a basal clade and the dipteran species in another. Within the latter, Drosophila species were found in one branch and the other dipterans in another. Musca and Lucilia clustered in a subgroup and the species of Tephritidae in another. Among the tephritids, Bactrocera and Ceratitis clustered into one subgroup on the same branch, while the Anastrepha species clustered into a different subgroup of that same branch.

Figure 5.

Molecular evolution of Tra2 proteins. (A) Amino acid phylogeny encompassing Tra2 proteins from Diptera. Taxonomic relationships are indicated in the right margin of the tree. Numbers for interior nodes represent bootstrap and confidence probabilities based on 1000 replicates, followed by the BP corresponding to the maximum parsimony tree topology (shown only when greater than 50%). The topology was rooted with the Tra2 protein from the lepidopteran B. mori and the hymenopterans A. mellifera and N. vitripennis. (B) Proportion of nucleotide sites at which two sequences being compared were different (p, nucleotide substitutions per site) and ratio between the numbers of non-synonymous (pN) and synonymous (pS) substitutions per site across the coding regions of tra-2 in the analysed species. The different functional regions defined for the Tra2 proteins are indicated below the graph.

The Tra2 protein from the Anastrepha species appears to be closely related to Tra2 from other tephritids, such as Ceratitis and Bactrocera, as well as to Musca and Lucilia, showing a monophyletic origin. The Tra2 proteins of the Drosophila representatives, however, show substantial divergence.

The variation presented both at the nucleotide and amino acid levels of the tra-2 gene in Diptera was studied in the present work by discriminating between the different functional domains of Tra2 protein: the RRM, RS N-terminal (RS1) and RS C-terminal (RS2) domains and the linker region. The overall amino acid and nucleotide variation were 0.236 ± 0.011 and 0.359 ± 0.021 substitutions per site, respectively, are given in additional File 5. The nature of this nucleotide variation was essentially synonymous, being significantly greater than the non-synonymous variation in all cases except for the N-terminal RS1 domain of the protein. The overall variation obtained in Diptera was substantially higher than that seen for the tephritids, which showed a high degree of protein conservation among themselves (0.048 ± 0.007 amino acid substitutions per site and 0.081 ± 0.006 nucleotide substitutions per site). In the tephritids - as for the dipterans - the level of synonymous variation was significantly greater than that of non-synonymous variation. Comparisons between the extent of synonymous and non-synonymous variation revealed significant differences in all cases (Z-test, P < 0.001; see additional File 5) with the exception of the N-terminal RS1 domain of Tra2, pointing towards the presence of negative selection acting at the protein level in order to maintain Tra2 structural features, especially with respect to the RRM domain.

A higher degree of protein and nucleotide sequence conservation in the Tra2 protein was evident in the region corresponding to the RRM motif as well as in the linker region (adjacent to RRM), in contrast to the high degree of variation presented by the RS1 and RS2 domains. The nucleotide variation across the tra-2 gene is detailed in the graph shown in Figure 5B. A valley in the region corresponding to the RRM and linker regions were observed concomitantly with a reduction in non-synonymous substitutions, emphasizing the critical role played by this RRM domain in Tra2 function.

Discussion

In this work, Aotra2 was characterised and found to produce a single mRNA in both sexes that encoded a 249 amino acid-long protein with the features of the SR protein family. In contrast to that seen in Drosophila, no significant partially spliced mRNA isoform specific to the male germ line was detected. The observed mRNA is transcribed in both sexes during development and in adult life in both the soma and germ line. The injection of Aotra-2 dsRNA into Anastrepha embryos caused a change in the splicing pattern of the endogenous tra and dsx pre-mRNAs of XX females from the female to the male mode. Consequently, these XX females showed transformation into pseudomales.

The recover of XX pseudomales composed of a mixture of male and female structures in the internal genitalia indicates that the transformation of females induced by the Aotra-2 dsRNA was partial. This result is in line to observations of partial transformation induced by RNAi of the gene tra of C. capitata [16], of B. oleae [17], of L. cuprina [30] and of M. domestica [36], and the partial transformation induced by RNAi of the gene tra-2 of M. domestica [29] and of C. capitata [23], in which some pseudomales had, e.g. male external genitalia but female structures in the anterior regions of the body. Unfortunately, in Anastrepha species, including the A. sp.1 here studied, the degree of sexual mosaicism at the morphological level cannot be inferred since there are no sexually dimorphic structures in the adult body other than the genitalia (external and internal) and the external analia [37]. Based on the results found in C. capitata, B. oleae, L. cuprina and M. domestica above mentioned, it is expected that in A. sp.1 the extent of the sexual transformation was also variable among the pseudomales; i.e. although these were identified as males by inspection of the external terminalia, other structures of the fly could remain female if the injected dsRNA did not reach their cellular precursors. This would explain the fact that the analysed A. sp.1 XX pseudomales showed traF and dsxF transcripts besides the expected traM and dsxM mRNAs. The variable amount of the female transcripts found in the pseudomales would be related to the different proportions of female structures in their non-sexually dimorphic regions. These results indicate that the Tra2 protein is needed for sex determination in Anastrepha.

Finally, the Tra2 proteins of ten other Anastrepha species were characterised and compared among themselves and with the Tra2 protein of other insects in which it has been characterised. The Tra2 protein from the Anastrepha species was closely related to the Tra2 from other tephritids, such as Ceratitis and Bactrocera, as well as to other dipterans such as Musca and Lucilia, showing a monophyletic origin. However, the Tra2 protein of Drosophila showed substantial divergence. The nature of the nucleotide variation in tra-2 was essentially synonymous (significantly more common than non-synonymous variation). This suggests the existence of negative selection acting at the protein level in order to maintain Tra2 structural features, especially with respect to the RRM domain.

Function of tra-2 in Anastrepha sex determination

In the tephritids C. capitata [16] and B. oleae [17], and in twelve Anastrepha species [18], the gene tra acts as the memory device for sex determination via its auto-regulatory function, i.e., through the contribution of the Tra protein to the female-specific splicing of its own pre-mRNA [16,17]. Further, the tra-2 of C. capitata is needed for the female-specific splicing of tra and dsx pre-mRNAs [23]. This requires the formation of a complex with the Tra protein, which then interacts with the Tra-Tra2 binding sites present in both pre-mRNAs [16,19]. This role for tra-2 in sex determination also exists in Anastrepha species (present work).

The maternal expression of tra [16-18] and tra-2 ([23]; present work) in tephritids supplies the embryo with maternal Tra-Tra2 complex. This is essential for imposing female-specific splicing of the initial zygotic tra pre-mRNA so that the first zygotic functional Tra protein is produced and tra auto-regulation can be established. In this scenario the XX embryos follow female development. In XY embryos, however, the yet non-characterised M factor present in the Y chromosome would prevent the tra auto-regulation system being set up. Consequently, these embryos would not produce functional Tra protein and develop as males [16] (see Figure 6). The existence of an M factor in the Y chromosome has been demonstrated only in C. capitata [38]. However, the analysis of tra in Bactrocera [17] and tra [18] and tra-2 (present work) in Anastrepha species suggests their Y chromosome have a similar function.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the sex determination gene cascades between Drosophilidae (Drosophila), and Tephritidae (Ceratitis Anastrepha and Bactrocera), Muscidae (Musca) and Calliphoridae (Lucilia) families of Diptera. Tramat and Tra2mat indicate maternal Tra and Tra2 product. DsxF and DsxM stands for female and male Dsx protein, respectively. Though the maternal expression of gene tra-2 in Lucilia and the characterisation of this gene in Bactrocera have not been reported, both species are included in the scheme of this Figure because the analysis of tra in Bactrocera [17] and the analysis of tra and tra-2 in Lucilia [30] suggests their tra-2 genes have a similar function as in Ceratitis, Anastrepha and Musca. Scheme based on references 16, 17, 18, 23, 29, 30 and 36.

Both the tephritid Tra and Tra2 protein show a dual splicing role in sex determination. On one hand both behave as a splicing activator of dsx pre-mRNA: the binding of Tra-Tra2 to the female-specific exon promotes the inclusion of this exon into the mature mRNA. On the other hand, Tra and Tra2 act as splicing inhibitors of tra pre-mRNA: the binding of Tra-Tra2 to the male-specific exons prevents the inclusion of these exons into the mature mRNA. It has been proposed that the Tra2-ISS binding sites, which have been found in the splicing regulatory region of the tra pre-mRNA of the tephritids, but not in dsx pre-mRNA, provide the distinguishing marker for the dual splicing function of the Tra-Tra2 complex in tephritids [18].

This role of genes tra and tra-2 in sex determination is not exclusive to tephritid insects (Diptera, Tephritidae) since the homologous genes in L. cuprina (Diptera, Calliphoridae) seem to play the same role [30]. A similar situation is found in the housefly M. domestica (Diptera, Muscidae), where the gene F plays the key role for female sex determination. The maternal product is needed to activate the zygotic function of F, which appears to show auto-regulation [39]. Recently, the molecular characterisation of F revealed it to be the orthologue of tra in the housefly [36]. tra-2 is also required for this auto-regulation in this species [29]. The existence of an M factor in the Y chromosome has been also demonstrated in Lucilia [40] and in Musca [41-43], though in this latter species, some strains carry the M factor in an autosome [44]. In XY zygotes, the presence of the masculinising factor M in the Y chromosome would prevent the establishment of tra auto-regulation and cause male development [30,36] (see Figure 6).

Together, these results support the model of Wilkins [45], who proposed that the evolution of sex-determining cascades was bottom up (for a theoretical analysis of this model see Pomiankowski et al., [46]). It has been suggested [18] that the tra/tra2 > dsx elements at the bottom of the cascade, and their relationships, likely represent the ancestral state (which still exists in the Tephritidae, Calliphoridae and Muscidae lineages) of the extant cascade found in the Drosophilidae lineage (in which tra is just another component of the sex determination gene cascade regulated by Sxl). Thus, in the phylogenetic lineage that gave rise to the drosophilids, evolution co-opted for the Sxl gene, modified it, and converted it into the key gene controlling sex determination.

In Drosophila, the gene tra-2 also shows a dual splicing role. It behaves as a splicing activator of dsx pre-mRNA in the soma of Drosophila females, but also acts as a splicing inhibitor of the M1 intron in tra-2 pre-mRNA in the germ line of Drosophila males (see Figure 1C). The presence of M1 in the mature tra-2 mRNA prevents the formation of full, functional Tra2 protein [32]. It has been found that Drosophila somatic cells are also able to prevent splicing of the M1 intron whenever levels of Tra2 protein are above normal [47]. The tra-2 promoter of the male-germ line is more active than the tra-2 promoter of the somatic tissues of Drosophila [27,28,47]. Regulated levels of Tra2 protein are therefore required since an excess of the Tra2 protein causes male sterility [33] and reduces the viability of Drosophila males and females [47].

The gene tra-2 produces a single mRNA in both sexes and no significant partially spliced mRNA isoform specific to the male germ line has been detected in Ceratitis [23], Musca [29], Lucilia [30] or Anastrepha (present work). Hence, it is here postulated that the promoter of this gene in the male germ line of these dipteran insects behaves in a fashion similar to that seen in the somatic tissues. The splicing inhibitor function of tra-2 observed in the Drosophila male germ line was probably acquired during the evolutionary lineage that gave rise to the drosophilids and may constitute an evolutionary solution for its high expression in this tissue and the return to normal levels of Tra2 protein. This protein belongs to the SR protein family, the members of which are involved in splicing regulation, mRNA transport and mRNA translation [48]. Its level in the cell must therefore be regulated if these processes are not to be impaired.

The molecular evolution of Tra2

The analysis of Tra2 relationships among the studied species resulted in a statistically well supported phylogenetic tree. In this tree, the Tephritidae species, which belong to the subgroup Acalyptratae of the suborder Brachycera, were more closely related to Musca and Lucilia, which belong to the Calyptratae subgroup of the suborder Brachycera, than to Drosophila species, which also belong to the subgroup Acalyptratae. These findings are in line with previous analyses of genes involved in sex determination, e.g., Sxl [49], tra [30] and tra-2 [22,30]. However, the analysis of dsx indicates a distinct relationship, i.e., Dsx proteins from the Tephritidae are more closely related to Drosophila than to Musca [21]. This discrepancy might be explained by the position of the genes dsx, tra and tra-2 in the sex determination cascade. The gene dsx is the more basal gene in this cascade, whereas the other genes would have been co-opted for sex determination over evolutionary time; thus, a higher degree of conservation can be expected for dsx than for tra or tra-2 [45]. The gene dsx encodes for transcription factors that control the sexual cytodifferentiation genes; dsx is therefore subject to strong purifying selection to maintain this control. The Tra and Tra2 proteins belong to the SR family of proteins involved in splicing, which are characterised by having repetitions of the serine-arginine dipeptide. Variation in the content of RS dipeptides seems to be a feature of the SR proteins whenever they have maintained enough such dipeptides to preserve their function [50].

The overall amino acid variation of Tra2 (present work) is significantly smaller than that previously reported for Tra [18]. The low rates of evolution shown by Tra2 in tephritids are also in agreement with the low rates of evolution reported for Tra in this group, and in stark contrast with the high rates of neutral evolution reported in some Drosophila species [50,51].

The extent of synonymous and non-synonymous nucleotide variation in the Tra2 proteins suggests the presence of extensive silent divergence. This, together with the strict conservation of the distribution of the RS-rich and RRM domains, suggests that tra-2 is subject to strong purifying selection to preserve the mechanism of action of Tra2 proteins. A higher degree of conservation was evident in the RRM and linker regions, in contrast to the diversity shown by the RS-rich regions. In fact, the RRM-linker junction region is considered a signature motif of Tra2 proteins [52].

The Tra protein seems to lack an RNA binding domain; thus, its influence in splicing regulation is exerted at the level of its interaction (through the RS domains) with other proteins carrying RNA-binding domains, such as Tra2 (reviewed in [53]). The variation in the number of RS dipeptides in the RS1 and RS2 regions of the Tra2 proteins parallels the situation found in the Tra proteins, which appear to undergo high rates of neutral evolution [50,51]. The high degree of conservation in the RRM domain of the Tra2 proteins studied here agrees with its fundamental role in the function of the Tra-Tra2 complex; this domain confers upon the complex its capacity to specifically interact with the tra and dsx pre-mRNAs and thus regulate its sex-specific splicing.

The high degree of divergence between the Anastrepha and the Drosophila Tra2 proteins is of particular interest. This divergence was mainly observed in the RS domains, which are involved in protein-protein interactions. This observation agrees with the experimental observation that the Anastrepha Tra-Drosophila Tra2 complex appears to be less efficient than the Drosophila Tra-Tra2 complex at inducing female-specific splicing of the Drosophila dsx pre-mRNA [54]. Hence, the interaction between the Anastrepha Tra protein and the Drosophila Tra2 protein might be impeded as a consequence of changes accumulated in these proteins after the Anastrepha and Drosophila phylogenetic lineages separated. These results suggest that Tra and Tra2 proteins co-evolved to exert their function in sex determination.

Conclusions

The gene transformer-2 is required for sex determination in Anastrepha through its participation in the female-specific splicing of transformer and doublesex pre-mRNAs. It is therefore needed for the auto-regulation of the gene transformer. Thus, the transformer/transfomer-2 > doublesex elements at the bottom of the cascade, and their relationships, probably represent the ancestral state (which still exists in the Tephritidae, Calliphoridae and Muscidae lineages) of the extant cascade found in the Drosophilidae lineage (in which tra is just another component of the sex determination gene cascade regulated by Sex-lethal). The extent of synonymous and non-synonymous nucleotide variation in the Tra2 proteins suggests the presence of extensive silent divergence. This, together with the strict conservation of the distribution of the RS-rich and RRM domains, suggests that tra-2 is subject to strong purifying selection to preserve the mechanism of action of Tra2 proteins.

Methods

Species

The species of Anastrepha studied, their host fruits, and the sites where they were collected are described in Ruiz et al. [21]. Rearing conditions were 23 ± 2°C, relative humidity 60-80%, light intensity 4000-5000 lux, photoperiod 12:12 h (L:D).

Molecular analyses

Genomic DNA was extracted from frozen specimens as described in Maniatis et al. [55]. Total RNA from adult female ovaries, adult male testis, embryos, larvae, and adult male and female somatic cells was prepared using the Ultraspec-II RNA isolation kit (Biotecx) following the manufacturer's instructions. Five micrograms of total RNA from each sample were reversed transcribed with Superscript (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription reactions were performed with an oligo-dT. Two percent of the synthesised cDNA was amplified by PCR. All amplicons were analysed by electrophoresis in agarose gels, cloned using the TOPO TA-cloning kit (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions and sequenced. In all cases, PCR reactions with RNA samples were performed to guarantee that they were not contaminated with genomic DNA (negative controls of PCR reactions).

The GenomeWalker genomic library of A. obliqua was synthesised using the BD GenomeWalker Universal kit (BD Biosciences), following the manufacturer's instructions.

Southern-blotting (see Figure 1F) was performed by transferring the RT-PCR products shown in Figure 1E onto a nylon membrane (Zeta-Probe Blotting Membranes BIO RAD). The probe used corresponds to a fragment of 630 nucleotides of the A. obliqua tra-2 gene, obtained by PCR involving genomic DNA and using the pair of primers PM1 and PM2 located at the 5' and 3' ends of intron 3 respectively (see Figure 1A). The probe was labelled with digoxigenin using the PCR DIG Labeling Mix kit (Roche) and hybridisation was detected with the DIG luminescent Detection Kit for Nucleic Acids (Roche) following the manufacturer's instructions.

DNA sequencing and sequence analysis

Sequencing was performed using an automated 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems). The analysis of sequences was performed by using the BLASTX programme.

Injection of Aotra2 dsRNA into Anastrepha embryos

The tra2 dsRNA was prepared as described for Drosophila [56]. The complete ORF of Aotra2 cloned in the pUAST plasmid was used as a template in a PCR reaction with the primer pair P1T7 and P3T3 (corresponding to primers P1 and P3) (see Figure 1A), flanked by a T7 promoter sequences at their 5' ends. The amplicon of this PCR was used as template to produce the tra2 dsRNA in an in vitro transcription reaction with T7 RNA polymerase using the Megascript kit (Ambion). This dsRNA was precipitated with ethanol and resuspended in the injection buffer [57].

Hemispheres made of 3% agar stained with red commercial food dye (aniline) and wrapped in parafilm® where furnished for oviposition [25], and eggs for injection recovered after 2 h. These were injected into the adjacent anterior region of the posterior pole with either 8 μM Aotra2 dsRNA (experimental embryos) or injection buffer (control embryos), following the described procedures [56] with minor modifications. The injected embryos were then transplanted into host fruit where they developed until reaching the pupal stage. The pupae were collected and transferred to population cages until the emergence of the adults. Newborn males (2-4 days old) were examined to record their external terminalia (external genitalia plus analia), which is the only external sexual dimorphic structure found in Anastrepha species [37], and then dissected for analysis of the internal genital structures and the removal of the testes for the determination of their chromosomal constitution.

Preparation of chromosome squashes

Chromosome squashes of testes from the Anastrepha males were prepared as previously described [58,59].

Sequences of the primers used in this work

Mar17: 5' GTRTGIGSIVGYTKNGTDATNGA 3';

Mar26: 5' MGIAGYCGNGGNTTYTGYTTY 3';

Tra2B: 5' NCKRTCRTCDATYTCCATNCC 3';

P1: 5' AGAGTTGGAATGAGTCCACG 3';

P2: 5' CACGTCGCTTATCGTATGGA 3';

P3: 5' CATATTTTTAATAGCGCGTACG 3';

P4: 5' ATTACCAAGGTGTGGGCTTC 3';

P5: 5' AGTGAAATCCAGTTGATACGC 3';

GW1: 5' TATCAGGATATAGCCGATGCTAAGGC 3';

GW2: 5' CAAGCGTCTTTAGCTGCCTTAGCATC 3';

PM1: 5' TACGAACGCAGCTTACTTCC 3';

PM2: 5' CTTGCGGTTCTGAGACTGAC 3'.

P1T7: 5' TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGACTAGAGTTGGAATGAGTCCACG 3'

P3T3: 5' TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGACTCATATTTTTAATAGCGCGTACG 3'

The Mar17 primer is described in Burghardt et al. [29]. The sequence of the Mar26 and Tra2B primers was generously provided by K. Komitopoulou.

Phylogenetic and Molecular Evolutionary Analyses

The present analysis included 21 tra-2 sequences belonging to different insects with the following accession numbers: DIPTERA: Anastrepha amita [EMBL: FN658617], A. bistrigata [EMBL: FN658616], A. fraterculus sp.1 [EMBL: FN658608], A. fraterculus sp.2 [EMBL: FN658609], A. fraterculus sp.3 [EMBL: FN658610], A. fraterculus sp.4 [EMBL:FN658611], A. grandis [EMBL:FN658612], A. obliqua [EMB:FN658607], A. serpentina [EMBL: FN658613], A. sororcula [EMBL: FN658614], A. striata [EMBL: FN658615], Ceratitis capitata [EMBL:EU999754], Bactrocera oleae [EMBL:AJ547623], Musca domestica [EMBL:AY847518], Lucilia cuprinia [EMBL:FJ461620], Drosophila melanogaster [EMBL:M23633], D. virilis [EMBL:XM_002049663], D. pseudoobscura [EMBL:XM_001360568]; LEPIDOPTERA: Bombyx mori [EMBL:NM_001126233]; HYMENOPTERA: Apis mellifera [EMBL:XM_001121070] and Nasonia vitripennis [EMBL:XP_001601106)]. Multiple sequence alignments were conducted on the basis of the translated amino acid sequences and edited for potential errors over 1089 nucleotide sites corresponding to 363 amino acid positions using BIOEDIT [60] and CLUSTAL W [61] software. The different domains in the Tra2 protein were defined according to Salvemini et al. [23] as: the RS-rich N-terminal region (19-459), the RNA recognition motif-RRM (502-717), the linker region (718-774), and the RS-rich C-terminal region (775-1077).

Molecular evolutionary analyses were performed using MEGA v.4 software [62]. The extent of nucleotide sequence divergence was estimated by means of the Kimura 2-parameter method [63] and the amino acid sequence divergence estimated by means of the uncorrected differences (p-distances). This approach is known to give good results, especially for distantly related taxa [64]. The number of synonymous (pS) and non-synonymous (pN) nucleotide differences per site were calculated using the modified method of Nei-Gojobori [65], providing the transition/transversion ratio (R) for each case. Evolutionary distances were calculated using the compete deletion option. Standard errors of the estimates were calculated using the bootstrap method (1000 replicates). Phylogenetic trees were reconstructed using the neighbour-joining tree-building method [66]. However, maximum parsimony trees were also inferred to ensure that the obtained results were not dependent on this choice. The reliability of the resulting topologies was tested by the bootstrap method [67] and by the interior-branch test [68], producing the bootstrap probability (BP) and confidence probability (CP) values for each interior branch in the tree respectively. Given that the bootstrap method is known to be conservative, a BP > 80% was interpreted as high statistical support for groups, whereas a CP ≥ 95% was considered statistically significant [69]. Phylogenies were rooted using the tra-2 gene of Lepidoptera and Hymenoptera.

The analysis of the nucleotide variation across coding regions was performed using the sliding-window approach afforded by DnaSP v.5 software [70], estimating the proportion (p) of nucleotide sites at which two sequences being compared were different, and the ratio between the numbers of non-synonymous (pN) and synonymous (pS) substitutions per site, employing a window length of 25 nucleotides and a step size of 5 nucleotides.

Authors' contributions

FS performed the experiments. MFR helped with the molecular biology experiments. JMEL performed the phylogenetic analyses. ALPP performed the analysis of chromosomes. DS performed the analysis of chromosomes and supervised the dsRNA injection experiments. LS conceived and supervised the study, and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Number of nucleotides that compose the exons and introns of gene tra-2 of A. obliqua, C. capitata and D. melanogaster. Exons (boxes) and introns (lines) are not drawn to scale.

Percentage similarity among the Anastrepha Tra2 proteins. Comparison of the Tra2 proteins of Anastrepha species.

Percentage similarity among the insect Tra2 proteins. Comparison of the Tra2 proteins of the insects so far characterised. A. obliqua was used as the reference species for the Anastrepha species.

Amino acid alignment of the Tra2 protein in the analysed species. The different protein domains are indicated as follows: RS-rich regions in grey background, RNA recognition motif (RRM) in green background, and linker region in yellow background. The RNP-1 and RNP-2 elements are indicated in open black boxes.

Evolutionary parameters of the Tra2 proteins from insects. Average numbers of amino acid (pAA), total nucleotide (pNT), synonymous (pS) and non-synonymous (pN) nucleotide differences per site, codon bias (Effective Number of Codons, ENC) and Z-test of selection in complete tra-2 genes and independent tra-2 domains from insects. SE, standard error; R, average transition/transversion ratio; n/a, not applicable. a H0: pN = pS; H1: pN <pS.

Contributor Information

Francesca Sarno, Email: francesca@cib.csic.es.

María F Ruiz, Email: nandyrl@cib.csic.es.

José M Eirín-López, Email: jeirin@udc.es.

André LP Perondini, Email: alpperon@ib.usp.br.

Denise Selivon, Email: dselivon@ib.usp.br.

Lucas Sánchez, Email: lsanchez@cib.csic.es.

Acknowledgements

This work was financed by grants BFU2005-03000 and BFU2008-00474 awarded to L. Sánchez by the D.G.I.C.Y.T. FS was the recipient of an EMBO Short-Term fellowship for the performance of the RNAi injection experiments at the University of Sao Paulo, Brazil. JME-L was supported by a contract within the Ramón y Cajal Subprogramme (MICINN).

References

- Sánchez L, Gorfinkiel N, Guerrero I. In: Comprehensive Molecular Insect Science. Gilbert LI, Iatrou K, Gill SS, editor. Vol. 1. Oxford: Elsevier Pergamon; 2005. Sex determination and the development of the genital disc; pp. 1–38. full_text. [Google Scholar]

- Bell LR, Maine EM, Schedl P, Cline TW. Sex-lethal, a Drosophila sex determination switch gene, exhibits sex-specific RNA splicing and sequence similar to RNA binding proteins. Cell. 1988;55:1037–1046. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90248-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell LR, Horabin JI, Schedl P, Cline TW. Positive autoregulation of Sex-lethal by alternative splicing maintains the female determined state in Drosophila. Cell. 1991;65:229–239. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90157-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggs RT, Gregor P, Idriss S, Belote JM, McKeown M. Regulation of sexual differentiation in Drosophila melanogaster via alternative splicing of RNA from the transformer gene. Cell. 1987;50:739–747. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90332-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belote JM, McKeown M, Boggs RT, Ohkawa R, Sosnowski BA. The molecular genetics of transformer, a genetic switch-controlling sexual differentiation in Drosophila. Devel Genet. 1989;10:143–154. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020100304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valcárcel J, Singh R, Zamore PD, Green MR. The protein Sex-lethal antagonizes the splicing factor U2AF to regulate alternative splicing of transformer pre-mRNA. Nature. 1993;362:171–175. doi: 10.1038/362171a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedley M, Maniatis T. Sex-specific splicing and polyadenylation of dsx pre-mRNA requires a sequence that binds specifically to tra-2 protein in vitro. Cell. 1991;65:579–586. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90090-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertel KJ, Lynch KW, Hsiao EC, Liu EHT, Maniatis T. Structural and functional conserevation of the Drosophila doublesex splicing enhancer repeat elements. RNA. 1996;2:969–981. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryner LC, Baker BS. Regulation of doublesex pre-mRNA processing occurs by 3'-splice site activation. Genes Dev. 1991;5:2071–2085. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.11.2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian M, Maniatis T. A splicing enhancer complex controls alternative splicing of doublesex pre-mRNA. Cell. 1993;74:105–114. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtis KC, Baker BS. Drosophila doublesex gene controls somatic sexual differentiation by producing alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding related sex-specific polypeptides. Cell. 1989;56:997–1010. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90633-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshijima K, Inoue K, Higuchi I, Sakamoto H, Shimura Y. Control of doublesex alternative splicing by transformer and transformer-2 in Drosophila. Science. 1991;252:833–836. doi: 10.1126/science.1902987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez L. Sex-determining mechanisms in insects. Int J Dev Biol. 2008;52:1059–1075. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072439ls. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saccone G, Peluso I, Artiaco D, Giordano E, Bopp D, Polito LC. The Ceratitis capitata homologue of the Drosophila sex-determining gene Sex-lethal is structurally conserved, but not sex-specifically regulated. Development. 1998;125:1495–1500. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.8.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos D, Ruiz MF, Sánchez L, Komitopoulou K. Isolation and characterization of the Bactrocera oleae genes orthologous to the sex determining Sex-lethal and doublesex genes of Drosophila melanogaster. Gene. 2005;384:111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pane A, Salvemini M, Bovi PD, Polito C, Saccone G. The transformer gene in Ceratitis capitata provides a genetic basis for selecting and remembering the sexual fate. Development. 2002;129:3715–3725. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.15.3715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos D, Koukidou M, Savakis C, Komitopoulou K. The transformer gene in Bactrocera oleae: the genetic switch that determines its sex fate. Insect Mol Biol. 2007;16:221–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz MF, Milano A, Salvemini M, Eirín-López JM, Perondini ALP, Selivon D, Polito C, Saccone G, Sánchez L. The gene transformer of Anastrepha fruit flies (Diptera, Tephritidae) and its evolution in insects. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(11):e1239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saccone G, Salvemini M, Pane A, Polito C. Masculinization of XX Drosophila transgenic flies expressing the Ceratitis capitata DoublsexM isoform. Int J Dev Biol. 2008;52:1043–1050. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082657gs. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz MF, Stefani RN, Mascarenhas RO, Perondini ALP, Selivon D, Sánchez L. The gene doublesex of the fruit fly Anastrepha obliqua (Diptera, Tephritidae) Genetics. 2005;171:849–854. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.044925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz MF, Eirín-López JM, Stefani RN, Perondini ALP, Selivon D, Sánchez L. The gene doublesex of Anastrepha fruit flies (Diptera, tephritidae) and its evolution in insects. Dev Genes Evol. 2007;217:725–731. doi: 10.1007/s00427-007-0178-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomulski LM, Dimopoulos G, Xi Z, Soares MB, Bonaldo MF, Malacrida AR, Gasperi G. Gene discovery in an invasive tephritid model pest species, the Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata. BMC Genetics. 2008;9:243. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvemini M, Robertson M, Aronson B, Atkinson P, Polito C, Saccone G. Ceratitis capitata transformer-2 gene is required to establish and maintain the autoregulation of Cctra, the master gene for female sex determination. Int J Dev Biol. 2009;53:109–120. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082681ms. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selivon D, Vretos C, Fontes L, Perondini ALP. In: Proc. VIth Intern. Symp. Fruit Flies Economic Importance: 2004; Irene, South Africa. Barnes BN, editor. Isteg Scientific Pub; 2004. New variant forms in the Anastrepha fraterculus complex (Diptera, Tephritidae) pp. 253–258. [Google Scholar]

- Selivon D, Perondini ALP, Morgante JS. A genetic-morphological characterization of two cryptic species of Anastrepha fraterculus complex (Dipetra, Tephritidae) Ann Entomol Soc Amer. 2005;98:365–381. doi: 10.1603/0013-8746(2005)098[0367:AGCOTC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norrbom AL, Zucchi RA, Hernández-Ortiz V. In: Fruit Flies (Tephritidae): phylogeny and evolution of behaviour. Aluja M, Norrbom AL, editor. Boca Ratón: CRC Press; 1999. Phylogeny of the genera Anastrepha and Toxotrypana (Trypetinae: Toxotrypanini) based on morphology; pp. 299–342. [Google Scholar]

- Amrein H, Maniatis T, Nöthiger R. Alternatively spliced transcripts of the sex determining gene tra-2 of Drosophila encode functional proteins of different size. EMBO J. 1990;9:3619–3629. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07573.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattox W, Palmer MJ, Baker BS. Alternative splicing of the sex determination gene transformer-2 is sex-specific in the germ line but not in the soma. Genes Dev. 1990;4:789–805. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.5.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burghardt G, Hediger M, Siegenthaler C, Moser M, Dübendorfer A, Bopp D. The transformer2 gene in Musca domestica is required for selecting and maintaining the female pathway of development. Dev Genes Evol. 2005;215:165–176. doi: 10.1007/s00427-004-0464-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concha C, Scott MJ. Sexual development in Lucilia cuprina (Diptera, Calliphoridae) is controlled by the transformer gene. Genetics. 2009;182:785–789. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.100982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattox W, Baker BS. Autoregulation of the splicing of transcripts from the transformer-2 gene of Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1991;5:786–796. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.5.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattox W, Palmer MJ, Baker BS. Alternative splicing of the sex determination gene transformer-2 is sex-specific in the germ line but not in the soma. Genes Dev. 1990;4:789–805. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.5.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuffin ME, Chandler D, Somaiya D, Dauwalder B, Mattox W. Autoregulation of transformer-2 alternative splicing is necessary for normal male fertility in Drosophila. Genetics. 1998;149:1477–1486. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.3.1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi J, Su S, Mattox W. The doublesex splicing enhancer components Tra and RBP1 also repress splicing through an intronic silencer. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:699–708. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01572-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selivon D, Perondini ALP, Rocha LS. The mitotic chromosomes of eight species of Anastrepha (Diptera, Tephritidae) Neotrop Entomol. 2005;34:273–279. doi: 10.1590/S1519-566X2005000200015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hediger M, Henggeler C, Meier N, Pérez R, Saccone G, Bopp D. Molecular characterization of the key switch F provides a basis for understanding the rapid divergence of the sex-determining pathway in the housefly. Genetics. 2010;184:155–170. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.109249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White IM, Elson-Harris MM. Fruit flies of economic significance: their identification and bionomics. CAB International 1992, Wallingford; p. 601. [Google Scholar]

- Willhoeft U, Franz G. Identification of the sex-determining region of the Ceratitis capitata Y chromosome by deletion mapping. Genetics. 1996;144:737–745. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.2.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dübendorfer A, Hediger M. The female-determining gene F of the housefly, Musca domestica, acts maternally to regulate its own zygotic activity. Genetics. 1998;150:221–226. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.1.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedo DG, Foster GG. Cytogenetic mapping of the male-determining region of Lucilia cuprina (Diptera: Calliphoridae) Chromosoma. 1985;92:344–350. doi: 10.1007/BF00327465. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroyoshi T. Sex-limited inheritance and abnormal sex ratio does not contribute to the X:A ratio in strains of the housefly. Genetics. 1964;50:373–385. doi: 10.1093/genetics/50.3.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubini PG, Palenzona D. Response to selection for high number of heterochromosomes in Musca domestica L. L. Genet Agr. 1967;21:101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hediger M, Minet AD, Niessen M, Schmidt R, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Sükran C, Nöthiger R, Dübendorfer A. The male-determining activity on the Y chromosome of the housefly (Musca domestica L.) consists of separable elements. Genetics. 1998;150:651–661. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.2.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dübendorfer A, Hediger M, Burghardt G, Bopp D. Musca domestica, a window on the evolution of sex-determining mechanisms in insects. Int J Dev Biol. 2002;46:75–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins A. Moving up the hierarchy: a hypothesis on the evolution of a genetic sex determination pathway. BioEssays. 1995;17:71–77. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomiankowski A, Nöthiger R, Wilkins A. The evolution of the Drosophila sex determination pathway. Genetics. 2004;166:1761–1773. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.4.1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi J, Su S, McGuffin ME, Mattox W. Concentration dependent selection of targets by an SR splicing regulator results in tissue-specific RNA processing. Nucl Acids Res. 2006;34:6256–6263. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard PJ, Hertel KJ. The SR protein family. Genome Biology. 2009;10:242. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-10-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serna E, Gorab E, Ruiz MF, Goday C, Eirín-López JM, Sánchez L. The gene Sex-lethal of the Sciaridae family (Order Diptera, Suborder Nematocera) and its phylogeny in dipteran insects. Genetics. 2004;168:907–921. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.031278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister BF, McVean GAT. Neutral evolution of the sex-determining gene transformer in Drosophila. Genetics. 2000;154:1711–1720. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.4.1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulathinal RJ, Skwarek L, Morton RA, Singh RS. Rapid evolution of the sex-determining gene, transformer: Structural diversity and rate heterogeneity among sibling species of Drosophila. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:441–452. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauwalder B, Amaya-Manzanares F, Mattox W. A human homologue of the Drosophila sex determination factor transformer-2 has conserved splicing regulatory functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9004–9009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DL. Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:291–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz MF, Sánchez L. Effect of the gene transformer of Anastrepha on the somatic sexual development of Drosophila. Int J Dev Biol. 2010;54:627–633. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.092917fr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis T, Fritsch F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Kennerdell JR, Carthew RW. Use of dsRNA-mediated genetic interference to demonstrate that frizzled and frizzled 2 act in the wingless pathway. Cell. 1998;95:1017–1026. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81725-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin GM, Spradling AC. Genetic transformation of Drosophila with transposable element vectors. Science. 1982;218:348–353. doi: 10.1126/science.6289436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selivon D, Perondini ALP. Evaluation of techniques for C and ASG banding of the mitotic chromosomes of Anastrepha fraterculus complex (Diptera, Tephritidae) Brazil J Genet. 1997;20:651–654. [Google Scholar]

- Goday C, Selivon D, Perondini ALP, Greciano PG, Ruiz MF. Cytological characterization of sex chromosomes and ribosomal DNA location in Anastrepha species (Diptera, Tephritidae) Cytogenet Genome Res. 2006;114:70–76. doi: 10.1159/000091931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucl Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignments through sequence weighting, position specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucl Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rate of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 1980;16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M, Kumar S. Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Rosenberg HF, Nei M. Positive Darwinian selection after gene duplication in primate ribonuclease genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3708–3713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsestein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.2307/2408678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitnikova T. Bootstrap method of interior-branch test for phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1996;13:605–611. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitnikova T, Rzhetsky A, Nei M. Interior-branch and bootstrap tests of phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1995;12:319–333. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1451–1452. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Number of nucleotides that compose the exons and introns of gene tra-2 of A. obliqua, C. capitata and D. melanogaster. Exons (boxes) and introns (lines) are not drawn to scale.

Percentage similarity among the Anastrepha Tra2 proteins. Comparison of the Tra2 proteins of Anastrepha species.

Percentage similarity among the insect Tra2 proteins. Comparison of the Tra2 proteins of the insects so far characterised. A. obliqua was used as the reference species for the Anastrepha species.

Amino acid alignment of the Tra2 protein in the analysed species. The different protein domains are indicated as follows: RS-rich regions in grey background, RNA recognition motif (RRM) in green background, and linker region in yellow background. The RNP-1 and RNP-2 elements are indicated in open black boxes.

Evolutionary parameters of the Tra2 proteins from insects. Average numbers of amino acid (pAA), total nucleotide (pNT), synonymous (pS) and non-synonymous (pN) nucleotide differences per site, codon bias (Effective Number of Codons, ENC) and Z-test of selection in complete tra-2 genes and independent tra-2 domains from insects. SE, standard error; R, average transition/transversion ratio; n/a, not applicable. a H0: pN = pS; H1: pN <pS.