Summary

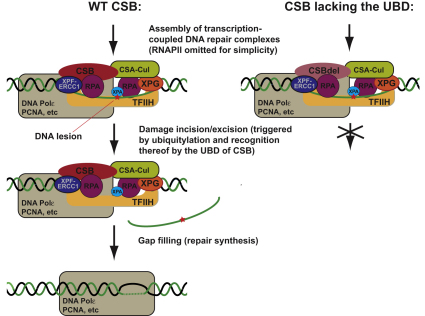

Transcription-coupled nucleotide excision repair (TC-NER) allows RNA polymerase II (RNAPII)-blocking lesions to be rapidly removed from the transcribed strand of active genes. Defective TCR in humans is associated with Cockayne syndrome (CS), typically caused by defects in either CSA or CSB. Here, we show that CSB contains a ubiquitin-binding domain (UBD). Cells expressing UBD-less CSB (CSBdel) have phenotypes similar to those of cells lacking CSB, but these can be suppressed by appending a heterologous UBD, so ubiquitin binding is essential for CSB function. Surprisingly, CSBdel remains capable of assembling nucleotide excision repair factors and repair synthesis proteins around damage-stalled RNAPII, but such repair complexes fail to excise the lesion. Together, our results indicate an essential role for protein ubiquitylation and CSB's UBD in triggering damage incision during TC-NER and allow us to integrate the function of CSA and CSB in a model for the process.

Keywords: DNA, PROTEINS

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

► Cockayne syndrome B protein harbors a carboxy-terminal ubiquitin-binding domain (UBD) ► UBD deletion (CSBdel) gives rise to the phenotypes typical of cells lacking CSB activity ► CSBdel becomes immobilized at DNA lesions and no longer supports transcription reactiviation ► CSBdel supports assembly of repair complexes, but these are incapable of damage incision

Introduction

Eukaryotic cells use multiple pathways to maintain genome integrity in response to DNA damage (Friedberg et al., 2005). One important response mechanism is nucleotide excision repair (NER), responsible for removing bulky DNA lesions such as those resulting from UV irradiation. The basic NER process can be separated into distinct steps, namely (1) damage recognition, (2) NER factor assembly, (3) dual incision and removal of a patch of single-stranded DNA containing the lesion (excision), and (4) DNA synthesis across the gap. Two distinct subpathways of NER have been described. Transcription-coupled nucleotide excision repair (TC-NER) is responsible for rapidly removing transcription-blocking DNA damage in the transcribed strand of active genes, whereas general genome repair (GG-NER) repairs lesions in the nontranscribed strand of genes, as well as in the large inactive regions of the genome (Wood et al., 2000; Svejstrup, 2002; Laine and Egly, 2006b; Hanawalt and Spivak, 2008). In humans, defective TCR is associated with Cockayne syndrome (CS), a severe autosomal-recessive disorder characterized by UV sensitivity, premature aging, and progressive neurodevelopmental abnormality (OMIM 133540-216400) (Lehmann, 2003). The vast majority of CS patients have defects in either the CSA or CSB gene (Licht et al., 2003), and cells carrying mutations in these genes are sensitive to UV irradiation, lack TC-NER, and display a dramatic delay in the recovery of RNA synthesis after DNA damage (Mayne and Lehmann, 1982; Venema et al., 1990; van Hoffen et al., 1993).

The CSA protein is a component of a ubiquitin ligase complex (Groisman et al., 2003), whose function in TC-NER has remained unclear. The CSB protein belongs to the SWI2/SNF2 family of DNA-dependent ATPases (translocases) (Troelstra et al., 1992). This protein is essential for establishing fully functional TCR complexes at DNA lesions in vivo (Fousteri et al., 2006) and in vitro (Laine and Egly, 2006a). Interestingly, the dramatic delay in recovering normal levels of transcription in UV-irradiated CSB cells is not due to the persistence of DNA damage per se, because even undamaged genes are repressed (Rockx et al., 2000; Proietti-De-Santis et al., 2006). This suggests that CSB plays at least two distinct roles: as a repair factor recruited to DNA damage in active genes and as a transcription factor required to keep genes active upon DNA damage.

As expected from its homology to the catalytic subunits of chromatin remodeling complexes, CSB can remodel nucleosomes in vitro (Citterio et al., 2000), and it also appears to affect transcription and chromatin structure in vivo in the absence of DNA damage (Newman et al., 2006). CSB can associate with complexes containing RNAPII (Tantin et al., 1997; van Gool et al., 1997; Citterio et al., 1998; van den Boom et al., 2004), and it has been suggested that the translocase activity of the protein might be used to remodel the interface between RNAPII and damaged DNA during TC-NER (Svejstrup, 2002, 2003). Although CSB has been intensively studied for many years and its importance in disease development and the DNA damage response is well established, answers to many key questions regarding the basic cellular function of the protein remain unknown.

As a starting point for the study described here, we analyzed CSB by sequence alignment. This uncovered a hitherto unnoticed, potential ubiquitin-binding domain at the C terminus of the protein. By the use of complementary in vitro and in vivo experiments, we here show that the ability of CSB to bind ubiquitin is essential for most, but not all aspects of its cellular function. Our findings shed light on the basic functions of CSB, and support the idea that TC-NER requires protein ubiquitylation and recognition thereof by CSB. They also allow us to propose a model for the mechanism of TC-NER, which incorporates the function of both CSA and CSB.

Results

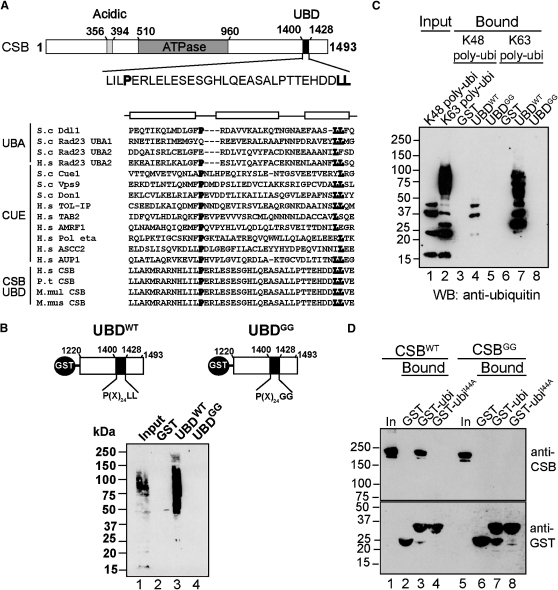

By visual inspection of the C-terminal region of CSB, we detected homology to a degenerate motif known as a “CUE” domain (amino acid Ile1400-Leu1428; Figure 1A, upper), found in a number of proteins involved in binding ubiquitylated proteins. The CUE domain consensus sequence consists of a conserved proline, and a dileucine motif, separated by ∼24 nonconserved amino acids (P(X)24LL) (Prag et al., 2003). Further in silico analysis of the region using 3D-PSSM software (which combines multiple sequence profiles with knowledge of three-dimensional protein structures [Kelley et al., 2000]) indicated the presence of a ubiquitin-binding associated (UBA) domain (between amino acids Ala1385 and Asn1433), encompassing the potential CUE domain. CUE and UBA domains are closely related. Both consist of three α helices with a hydrophobic core around a dileucine motif present in the third helix domains, and both are known to bind both mono- and polyubiquitin (Schnell and Hicke, 2003; Hurley et al., 2006). In the following, we shall refer to this CSB domain as the ubiquitin-binding domain (UBD). Sequence alignment of the predicted UBD with CUE and UBA domains from different proteins not only confirmed the presence of the conserved proline and dileucine motifs, but also predicted a significant degree of similarity in secondary structure (Figure 1A, lower). The motif is absent from the functional CSB homolog in budding yeast (Rad26), but comparison of CSB sequences from several mammalian species revealed that the key elements of the UBD are highly conserved (see Figure S1 available online), further supporting the idea that it might be functionally important.

Figure 1.

Identification of a Ubiquitin-Binding Domain in CSB

(A) Upper: Schematic drawing of CSB indicating the UBD. Lower: Multiple sequence alignment of UBA and CUE domains from various proteins. Conserved residues that contribute to the hydrophobic core are in bold. Boxes at the top denote the locations of α helices in the yeast Cue2 CUE1 and human HHR23A UBA1 domains, respectively.

(B) Upper: GST-UBDWT and GST-UBDGG fusion proteins used for ubiquitin binding assay. Lower: Ubiquitylated proteins from human cell lysates retained on immobilized GST, GST-UBDWT, or GST-UBDLL. Total lysate (5%) and eluted proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by anti-ubiquitin immunoblotting.

(C) Pure multiubiquitin chains retained on immobilized GST, GST-UBDWT, or GST-UBDGG, analyzed as in (B).

(D) Binding of CSBWT or CSBGG to immobilized GST, GST-ubiquitin, or GST-ubiquitinI44A. Total human cell lysate (10%) and eluted proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by anti-CSB immunoblotting (upper panel). Equivalent loading was examined by anti-GST immunoblotting (lower panel). See also Figure S1.

CSB Binds Ubiquitin via the UBD

In order to investigate if the UBD can bind ubiquitin, its ability to isolate naturally occurring ubiquitylated proteins from human cells was tested (Figure 1B). We first established that a GST fusion protein containing a short 43 amino acid region with the core UBD motif (CSB amino acids 1389–1431) was unable to bind ubiquitin or ubiquitylated proteins when fused to glutathione S-transferase (GST) (data not shown), presumably because a larger region is required for proper protein folding. A GST fusion protein containing the C-terminal 273 amino acids of CSB, encompassing the UBD, was therefore used instead (Figure 1B upper; UBDWT). UBDWT, but not GST alone, pulled down ubiquitylated proteins (Figure 1B lower; compare lanes 2 and 3). The dileucine motif of the UBD was also mutated to diglycine (Figure 1B upper; UBDGG = L1427L1428→G1427G1428); UBDGG failed to bind ubiquitylated protein (Figure 1B lower, lane 4). In vitro binding assays with pure lysine48- and lysine63-linked polyubiquitin chains were also performed (Figure 1C). Although UBDWT bound both forms of polyubiquitin (lanes 4 and 7), neither UBDGG (lanes 5 and 8) nor GST alone (lanes 3 and 6) bound to any form of polyubiquitin.

The majority of ubiquitin-binding domains characterized so far interact with a hydrophobic patch on the surface of ubiquitin that includes ubiquitin isoleucine44 (Kang et al., 2003; Varadan et al., 2005). To test if point mutation of ubiquitin isoleucine44 abolishes interaction with CSB, different forms of full-length, myc-tagged CSB were expressed in human cells and the resulting cell extracts were incubated with either immobilized GST-ubiquitin, or immobilized GST-ubiquitinI44A (Figure 1D). GST-ubiquitin (lane 3), but not GST-ubiquitinI44A (lane 4) or GST alone (lane 2), pulled down wild-type CSB, whereas CSBGG failed to interact with GST-ubiquitin (compare lane 7 with lane 3). Together, these results indicate that CSB interacts with ubiquitin via the UBD at its C terminus.

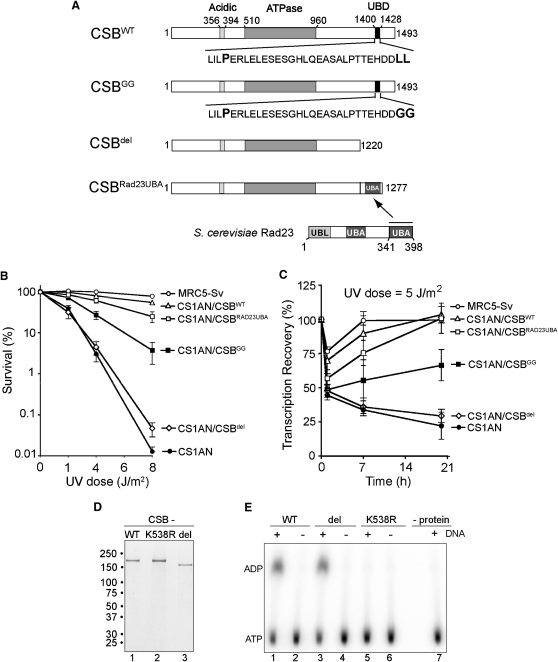

Defects in the Ubiquitin-Binding Domain Affect CSB Function

We now examined the importance of the UBD for CSB function in vivo. The CSB-deficient cell line CS1AN-Sv (CS1AN) was transfected with constructs expressing CSBWT and CSBGG to generate stable cell lines (Figure 2A, CSBWT and CSBGG), and cells expressing physiological levels of CSB protein were selected for further analysis. The relative UV sensitivity of CSBWT and CSBGG cell lines was then determined by clonogenic survival assays (Figure 2B). As expected (Mayne et al., 1986; Venema et al., 1990), CSB-deficient cells (CS1AN) were very sensitive to UV irradiation, whereas CS1AN cells expressing CSBWT exhibited a level of UV resistance that was similar to that of normal human fibroblast (MRC5-Sv) cells. Interestingly, cells expressing CSB with point mutations in the UBD (CSBGG) were also UV sensitive, although they were clearly less sensitive than the parental CS1AN-Sv cells (Figure 2B). This might indicate that the ability of CSB to bind ubiquitin is important but not absolutely required for normal function. Alternatively, it might simply mean that although the point-mutated CSBGG protein is severely defective for ubiquitin-binding in vitro, it is only partially deficient in vivo, i.e., that it has some residual ubiquitin-binding ability in the context of its other interaction partners inside the cell.

Figure 2.

Functional Importance of CSB's Ubiquitin-Binding Domain

(A) Schematic representation of proteins stably expressed in CSB-deficient (CS1AN-sv) human fibroblasts.

(B) UV-survival experiment, with percentage surviving cells (logarithmic scale) plotted against UV dose. Error bars indicate standard error based on three independent experiments.

(C) RNA synthesis after UV irradiation measured as the relative incorporation of 3H-uridine in 5 J/m2-irradiated cells compared with unirradiated cells (100%). Relative transcription is plotted against the UV dose. Error bars indicate standard error based on three independent experiments.

(D) SDS-PAGE analysis of overexpressed CSB proteins, purified from human cells, stained with Coomassie blue. Migration of molecular weight markers is indicated on the left.

(E) DNA-dependent ATPase activity of CSB proteins, measured as generation of α-P32-ADP from α-P32-ATP. CSB K538R is used as negative control. This mutation, in the invariant lysine residue in the NTP-binding motif of CSB, inhibits ATP hydrolysis (Citterio et al., 1998). See also Figure S2.

In order to further examine the importance of CSB's ability to bind ubiquitin, we therefore now created a deletion mutant where 273 amino acids (including the entire UBD) were removed from the C terminus of CSB (Figure 2A, CSBdel). Such deletion does not affect the catalytic activity of CSB. Indeed, highly purified CSBdel (Figure 2D) displayed DNA-dependent ATPase activity indistinguishable from that of CSBWT (Figure 2E; see also Figure S2 for similar data on CSBGG), indicating that deletion of the UBD does not inhibit the catalytic activity of the protein. We also generated a cell line expressing a new version of the CSB protein by appending one of the two ubiquitin-binding domains (UBA2) from the otherwise unrelated Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad23 protein (Chen et al., 2001) to the C terminus of CSBdel (Figure 2A, CSBRad23UBA). Strikingly, CSBdel cells were UV sensitive to an extent similar to that observed in the CSB-deficient cell line (CS1AN) (Figure 2B). In contrast, cells expressing the chimeric CSBRad23UBA protein exhibited a level of UV sensitivity that was similar to that of cells expressing full-length CSB (CSBWT), showing that the Rad23 UBA domain could functionally substitute for CSB's UBD.

Failure to recover RNA synthesis is another hallmark of CS cells, which can be restored by expressing WT CSB (Mayne and Lehmann, 1982; Troelstra et al., 1992). We examined RNA synthesis recovery after UV irradiation by [3H]uridine incorporation in the CSB cell lines (Figure 2C). As expected, overall transcription levels were rapidly reduced in all cell types upon UV irradiation. Transcription quickly recovered to normal levels in human fibroblast (MRC5) and CSBWT cells, but such recovery did not occur in CSB-deficient (CS1AN) cells. More importantly, expression of CSB with mutations in (CSBGG), or deletion of (CSBdel), the UBD failed to restore UV-induced inhibition of transcription even after 24 hr. In contrast, normal transcription recovery was observed in CSBRad23UBA cells, again indicating that Rad23's UBA domain can effectively replace the UBD of CSB to restore CSB function.

Taken together, these results point to a critical role for CSB's ability to bind ubiquitin during the DNA damage response.

Mutation in the Ubiquitin-Binding Domain of CSB Affects RNAPII Recruitment to the DHFR Promoter after UV Irradiation

When an undamaged reporter plasmid is introduced into UV-irradiated cells, reporter gene transcription is eventually observed in normal cells, but not in CSB-deficient cells (Proietti-De-Santis et al., 2006), suggesting that DNA damage generates a signal to repress transcription, and that recovery of expression requires CSB. Previous chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) studies revealed that upon UV irradiation, CSB is recruited to the promoter of constitutively active housekeeping genes, such as dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), and that concomitant recruitment of RNAPII to these genes is defective in CSB-deficient cells (Proietti-De-Santis et al., 2006). To examine the possible basis for the lack of recovery of RNA synthesis observed in cells expressing UBD mutants, the kinetics of CSB and RNAPII recruitment to the DHFR promoter after UV irradiation was examined. As observed previously (Proietti-De-Santis et al., 2006), the promoter occupancy of CSBWT was reduced immediately after UV irradiation, but then recovered at later time points (Figure 3A). The promoter occupancy of CSBGG and CSBdel was also significantly reduced after UV irradiation, but did not recover with time. In contrast, promoter recruitment did recover in UV-irradiated cells expressing CSBRad23UBA (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Association of CSB and RNAPII with the DHFR Promoter

(A) Upper: Schematic of DHFR and position of PCR primers. Lower: Kinetics of CSB occupancy at the DHFR promoter after UV irradiation measured by ChIP. The results obtained in untreated cells were set to one, and the other values relative to that, with standard deviation. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

(B) As in (A) but for RNAPII.

As expected (Proietti-De-Santis et al., 2006), a dramatic drop in RNAPII occupancy at the DHFR promoter occurred immediately after UV irradiation as well, but this gradually recovered to normal levels in CSBWT cells, whereas no such recovery was observed in CS1AN cells (Figure 3B). More importantly, little or no recovery of RNAPII recruitment was observed in CSBGG and CSBdel cells, whereas recovery was normal in cells expressing CSBRad23UBA (Figure 3B).

Taken together, these data indicate that the UBD of CSB is required for normal recruitment of both CSB and RNAPII to the DHFR promoter upon UV irradiation.

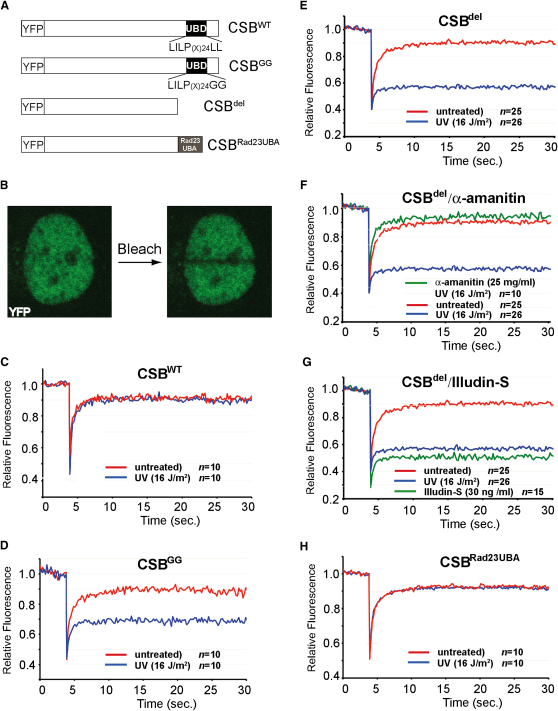

Ubiquitin Binding Is Crucial for the Nuclear Mobility of CSB

Previous results indicated that in contrast to general NER factors such as XPA and XPG, CSB is extremely dynamically associated with DNA damage (Rademakers et al., 2003; van den Boom et al., 2004; Zotter et al., 2006). In order to study the effect of the UBD on the mobility of CSB after DNA damage, we fused yellow fluorescent protein to the amino-terminus of it (YFP-CSBWT). We also generated YFP-CSBGG, YFP-CSBdel, and YFP-CSBRad23UBA constructs (Figure 4A). Stable cell lines expressing these CSB proteins were selected for further analysis. To monitor the dynamic properties of the different YFP-tagged CSB forms during TC-NER, we used fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) (Giglia-Mari et al., 2006). In this assay, fluorescent proteins are photobleached in a narrow strip spanning the cell nucleus by a high-intensity laser pulse (Figure 4B). The subsequent fluorescence recovery is monitored in time, providing a measure for the protein's mobility. To study CSB mobility during TC-NER, the recovery of fluorescence in cells before and after UV irradiation was measured. The fluorescence recovery plot of UV-damaged CSBWT cells revealed little or no reduction in fluorescence recovery when compared with undamaged control cells (Figure 4C), suggesting that only a minor fraction of YFP-CSBWT molecules are transiently immobilized during DNA repair. In contrast, CSBGG mobility was clearly reduced upon UV irradiation (Figure 4D). An even more dramatic reduction of fluorescence recovery was observed in irradiated YFP-CSBdel cells (Figure 4E), indicating that CSB protein lacking UBD function largely loses its dynamic interaction with DNA as a consequence of UV-induced damage. In order to confirm that CSBdel was retained specifically in the damaged area rather than being subject to a pan-nuclear UV-induced mobility reduction, we induced local damage with a UVC-laser in nuclei from YFP-CSBdel cells (Dinant et al., 2007) and then measured YFP-CSBdel mobility in both undamaged and damaged subnuclear regions by FRAP analyses, as previously described (Mari et al., 2006). YFP-CSBdel mobility was greatly reduced in UV-damaged, but not undamaged, areas of the cells (Figure S3A), demonstrating that the absence of the UBD specifically affects the ability of CSB to dissociate from DNA lesions. Likewise, once recruited to DNA damage, CSBdel failed to be recruited to lesions generated elsewhere (Figure S3B).

Figure 4.

CSB Lacking the UBD Becomes Immobilized at DNA Damage in a TC-NER-Dependent Manner

(A) Scheme of the different constructs used.

(B) Confocal images of a human fibroblast stably expressing YFP-CSBdel before and after bleaching of a strip along the nucleus width.

(C-E) Strip-FRAP graphs showing the mobility of (C) YFP-CSBWT, (D) YFP-CSBGG, and (E) YFP-CSBdel in untreated (red) and UV-irradiated cells (blue).

(F) As in (E), but using cells pre-treated with α-amanitin to block transcription (green).

(G) As in (E), but also using cells treated with 30 ng/ml Illudin S (green).

(H) Strip-FRAP graph showing the mobility of YFP-CSBRad23UBA in untreated (red) and UV-irradiated cells (blue). See also Figure S3.

Because TC-NER is triggered by RNAPII elongation complexes stalled at damage in active genes, we wanted to investigate if UV-induced immobilization of CSBdel was transcription dependent. No reduction in mobility was observed when YFP-CSBdel cells were treated with the specific RNAPII inhibitor α-amanitin before UV-irradiation, indicating that UV-induced immobilization of YFP-CSBdel indeed requires actively transcribing RNAPII (Figure 4F). We also examined the effect of the chemical mutagen Illudin-S, which causes DNA damage that is repaired only by TC-NER (Jaspers et al., 2002). Illudin-S treatment also resulted in a dramatic immobilization of YFP-CSBdel (Figure 4G), further supporting the idea that CSB immobilization is caused by TC-NER. Finally, in order to address whether the mobility of CSB depends on binding to ubiquitin, we studied the mobility of YFP-CSBRad23UBA. As observed with YFP-CSBWT, the chimeric protein was dynamically associated with the DNA also after UV irradiation (Figure 4H), indicating that the reduced mobility can indeed be attributed to the ubiquitin-binding ability of CSB.

Together, these results indicate that the UBD of CSB is required for remobilizing the protein during TC-NER of UV-induced DNA damage.

DNA Damage-Dependent Assembly of TC-NER Factors in Cells Lacking CSB UBD Function

We now addressed the mechanistic basis for the involvement of the UBD in TC-NER. The possible contribution of the UBD in recruiting proteins to sites of TC-NER was investigated using a previously described ChIP-western blot assay (Fousteri et al., 2006). In this approach, proteins are cross-linked to DNA with formaldehyde, the DNA fragmented by sonication (so that less than one DNA lesion on average is found on each fragment), and the (direct or indirect) coimmunoprecipitation of factors recruited to the area immediately around DNA damage examined. Previous experiments using this assay provided evidence for the association of CSB, CSA, NER factors, and other proteins with damage-stalled RNAPII (Fousteri et al., 2006). Cells lacking CSB fail to support association of any of these factors with RNAPII after DNA damage, whereas cells lacking CSA support damage-dependent association of CSB, NER factors, and RNAPII, but are defective for the recruitment of other proteins of unknown function, such as the HMGN1 protein (Fousteri et al., 2006).

We used the assay to examine DNA damage-induced association of different proteins with CSB (Figure 5). For simplicity, and because we had observed that deletion of the CSB UBD resulted in phenotypes similar to those of CSB-deficient cells, we only compared cells expressing CSBWT and CSBdel in these experiments. Interestingly, though cells expressing CSBdel failed to recruit RNAPII to the DHFR promoter after UV irradiation (see Figure 3B), this mutant could still associate with the polymerase in a damage-dependent manner (Figure 5A, compare lanes 3 and 4), though minor differences in the extent and timing were observed when compared with CSBWT (compare lanes 2 and 4; and data not shown). Likewise, CSBdel also remained capable of associating with general NER factors such as XPD (TFIIH), XPA, XPF, and RPA after DNA damage (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

CSB Lacking the UBD Remains Capable of Assembling TC-NER Complexes after DNA Damage

(A) Western blot of CSB-specific ChIPs using antibodies directed against the factors indicated on the left, in cell lines expressing CSB or CSBdel, as indicated.

(B and C) As in (A), but with antibodies against proteins involved in repair synthesis (B), or ubiquitylated histone H2A (C). Histone proteins in lower panels serve as loading controls.

Because CSBdel could assemble a potentially fully functional NER complex, we now looked at its damage-induced association with CSA and postincision (repair synthesis) factors (Figure 5B). CSA and DDB1 (components of the CSA ubiquitin ligase complex), as well as the HMGN1 protein (whose recruitment requires CSA [Fousteri et al., 2006]), were also recruited normally by CSBdel upon DNA damage. Surprisingly, even factors involved in repair synthesis, such as PCNA and DNA polymerase δ, associated with both wild-type and CSBdel in a DNA damage-dependent manner (Figure 5B), showing that proteins required for gap filling after damage excision could be recruited in the absence of the UBD as well.

These results were intriguing: CSBdel cells were as UV sensitive as cells completely lacking CSB activity, yet the mutant cells were perfectly capable of assembling NER proteins and repair synthesis factors at sites of DNA damage-stalled RNAPII. Two obvious possibilities were raised by these results. First, the defect in CSBdel cells might not be in the actual TC-NER process itself, but rather in a downstream event, such as the recycling of factors after repair is completed. Alternatively, even though all the proteins required for completing the repair process are there, TC-NER might nevertheless not take place. We first addressed this conundrum by investigating the recruitment of ubiquitylated histone H2A (ubi-H2A) to sites of TC-NER. Previous results showed that the DNA-damage dependent appearance of this histone variant in chromatin is strictly dependent on NER: it represents a postrepair event (Bergink et al., 2006; Marteijn et al., 2009; Zhu et al., 2009).

Interestingly, a dramatic decrease in damage-induced association of ubi-H2A was observed in CSBdel cells (Figure 5C). This strongly indicates that no TC-NER is supported by the complexes built up by CSBdel at DNA-damage stalled RNAPII, though it was still formally possible that repair does take place, but that CSB's UBD is specifically required for the formation of chromatin containing ubi-H2A following repair.

Lack of TC-NER in CSBdel Cells

We now directly tested whether TC-NER occurred in CSBdel cells (Figure 6). Cells were UV-irradiated, and repair was allowed to take place, with aliquots taken out at different time point over the next 8 hr. Repair was then analyzed by alkaline agarose gel electrophoresis and probing Southern blots with DNA strand-specific probes (Spivak et al., 2006) (Figure 6A, upper). In this approach, T4 endonuclease V (T4 EndoV) is used as a diagnostic for cellular repair; it nicks the DNA at UV-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers, so that if lesions remain in the purified gene fragment, the DNA strand containing the lesion will be cleaved and therefore be absent from the blot. As repair (damage excision and repair synthesis) progresses with time, there will be more and more protection from T4 EndoV nicking (Figure 6A, lower). On the other hand, if damage excision (single-stranded DNA incision[s]) were to occur without subsequent repair synthesis, the gene fragment would disappear with time even in the absence of T4 EndoV treatment (example in Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

CSB Lacking the UBD Fails to Support TC-NER Damage Incision

(A) Upper: Schematic of the TC-NER assay (Spivak et al., 2006). Lower: Stylized example of result from normal TC-NER reaction. As long as damages persist in a fragment, T4 EndoV will digest it (+), resulting in a smaller amount of fragment compared with the untreated control lanes (−).

(B) Expected result from assay if damage incision (one or both) is defective in the tested cell line.

(C) TC-NER in endogenous DHFR gene in the cell lines indicated immediately below blots probed with a strand-specific probe. TS, transcribed strand; NTS, nontranscribed strand.

As expected (Venema et al., 1990), little or no TC-NER was observed in CSB-deficient cells (CS1AN) compared with cells expressing CSBWT (Figure 6C, upper two panels, compare lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8). More importantly, however, cells expressing CSBdel showed no appreciable TC-NER (third panel, lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8), and no evidence for incision without gap-filling was observed either (compare lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7). However, as expected from the UV insensitivity of these cells, TC-NER was recovered in cells expressing CSBRad23UBA (lower panel, lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8). No significant difference in GG-NER was observed between these cell lines; a weak signal was detected 8 hr after UV irradiation (lane 8 in all NTS blots), indicating repair in the nontranscribed strand of DHFR beginning to become detectable at this point, as expected (Mellon et al., 1987).

Together, these experiments indicate that the ability of CSB to bind ubiquitin is essential for measurable levels of damage incision to be triggered during TC-NER. This, in turn, causes a lack repair synthesis and the absence of ubi-H2A at sites of DNA damage in genes.

Discussion

The DNA-dependent ATPase (translocase) CSB is absolutely required for TC-NER in mammalian cells, but remarkably little insight into the molecular role of the protein has been obtained since this was first reported two decades ago. The data reported here show that, surprisingly, CSB contains a C-terminal UBD, which is absolutely required for TC-NER in vivo. The ubiquitin-binding domain from a heterologous protein, namely the UBA2 domain from the yeast Rad23 protein, can functionally replace the UBD, essentially ruling out the possibility that the deletion in CSBdel compromises any other essential CSB function than ubiquitin binding. Together, our data shed important light on the function of CSB, and provide the basis for proposing a model for the events taking place during TC-NER.

The Ubiquitin-Binding Domain of CSB

UBDs are found in diverse groups of proteins and connect various cellular processes to protein ubiquitylation (Hofmann, 2009). As the same types of ubiquitin modification are involved in numerous, fundamentally different processes, recognition of the ubiquitin mark has to be complemented by other recognition of the modified protein. Thus, specific interaction of a ubiquitylated protein almost certainly always involves two modes of recognition: one aimed at the target protein itself, and the other at its ubiquitin moiety (Hofmann, 2009). Data on the recognition of monoubiquitylated PCNA provide direct evidence to support this view: the translesion synthesis DNA polymerases Polι and polη bind directly to PCNA via their PCNA-interacting peptide (PIP box). However, in addition, DNA damage-induced monoubiquitylation of PCNA increases the interaction via the UBDs of these proteins (Bienko et al., 2005 and references therein). In the case of CSB, it is clear that its UBD in isolation can bind to a variety of ubiquitylated proteins and ubiquitin chains, with some preference for longer ubiquitin chains, especially those linked via ubiquitin lysine 63. However, the functional importance/relevance of this preference in the context of the whole CSB protein cannot be predicted at this point, and the finding that CSB's UBD can be replaced with a heterologous UBD is best consistent with the idea that there is no intrinsic restriction of binding to a particular type of ubiquitin (chain). We also note that full-length CSB protein even binds to a GST-(mono)ubiquitin fusion protein, showing that a polyubiquitin chain is not strictly required for binding. It is thus entirely possible that CSB's UBD normally recognizes a monoubiquitin moiety.

At first glance, ubiquitylated histone H2A might be considered a candidate for a target protein: CSB binds (un-ubiquitylated) core histones in vitro (Citterio et al., 2000), and we find that the UBD is required for the association of monoubiquitylated histone H2A (ubi-H2A) with CSB at sites of TC-NER in vivo. However, it is important to stress that the observed failure of CSBdel to support TC-NER in itself precludes the appearance of ubi-H2A in chromatin after UV irradiation. Indeed, previous data have provided convincing evidence that the damage-dependent appearance of ubi-H2A in chromatin absolutely requires functional NER (Bergink et al., 2006; Marteijn et al., 2009). Because no TC-NER takes place in cells expressing CSB lacking the UBD (so that ubi-H2A-containing chromatin cannot be generated in any case), we cannot at this point investigate the potential direct role of CSB's UBD in ubi-H2A transactions after DNA damage in vivo. Experiments with different CSB forms and nucleosomes containing either unmodified or ubi-H2A have so far failed to uncover an effect of H2A ubiquitylation on CSB's nucleosome-stimulated ATPase activity (R.A., unpublished data), but negative results should be treated with caution, so this needs to be further investigated. It is thus a formal possibility that CSB can also recruit (or remodel chromatin containing) ubiquitylated histones via its UBD. Interestingly, other core histones than H2A are also ubiquitylated (Osley et al., 2006), some in a damage-regulated manner (Wang et al., 2006). Moreover, CSB appears to also be involved in transcription and chromatin transactions in the absence of DNA damage (Newman et al., 2006). So, the UBD might be employed for purposes other than TC-NER as well. This is presently under investigation.

Lack of Transcription Recovery in Cells Expressing CSBdel: Immobilization at Sites of DNA Damage

Our ChIP experiments showed that the UBD of CSB is required for normal occupancy of both CSB and RNAPII at the DHFR promoter upon UV irradiation. This helps to explain the general failure of cells lacking the CSB UBD to recover RNA synthesis upon UV irradiation. Interestingly, whereas wild-type CSB is recruited to DNA damage and dynamically associated with it, we found that although CSBdel appears to be recruited normally to damaged DNA, it displays surprisingly little dynamic mobility upon UV-induced DNA damage. One possible explanation for this observation is that assembly of a stable TC-NER complex takes place around CSBdel, and that this stable complex is only slowly resolved because the repair reaction cannot be completed. Alternatively, or additionally, the UBD might somehow be required for the dynamic association with other proteins recruited to DNA damage. In any case, it is an obvious possibility that the failure of CSB to be recruited to the DHFR promoter upon UV irradiation is an indirect effect of its much longer retention time at sites of DNA damage.

Hypotheses for the Mechanism of TC-NER

Our data also indicate that the ubiquitin-binding domain in CSB is required for eliciting damage incision/excision during TC-NER. This is surprising, and provides insight into the process of TC-NER. It is surprising because we uncovered no evidence that factors involved in TC-NER are missing from repair complexes assembled by CSBdel. Indeed, even factors required for repair synthesis were recruited, yet no measurable damage incision/excision took place in these complexes. Importantly, the apparent presence of gap-filling/repair synthesis factors at RNAPII-stalling DNA lesions even before dual incision takes place suggests that all protein required for successful TC-NER are preassembled (probably through protein-protein interactions) before the start signal for repair is given. The results are also significant in that ubiquitylation of a factor(s) in the repair complex, such as RNAPII, one or more of the NER factors, or even CSB itself (Groisman et al., 2006; Nouspikel and Hanawalt, 2006; Anindya et al., 2007; Ulrich, 2009)—and recognition of this ubiquitylated protein(s) by CSB—now enters the fray as a possible trigger for damage incision. Alternatively, or additionally, the UBD may somehow allow CSB to be released after repair, or at different stages during the establishment of the TC-NER complex. In this scenario, the absence of UBD-promoted CSB recycling would only allow a minimal number of lesions to be removed from cells, causing the observed effects.

The ubiquitin ligase activity responsible for ubiquitylation (and thus ubiquitin-binding by CSB) at sites of TC-NER is likely to be found among factors that have previously been connected to TC-NER, such as CSA (Groisman et al., 2003). Indeed, it is striking that whereas mammalian CSB harbors a UBD that is essential for TC-NER, the yeast CSB homolog Rad26 lacks this domain. Remarkably, this correlates with a lack of requirement for a yeast homolog of CSA. The best homolog of CSA, Rad28, is thus not required for TC-NER in budding yeast (Bhatia et al., 1996), whereas CSA—via a mechanism that it has hitherto been difficult to even speculate on—is absolutely required for it in mammalian cells (Venema et al., 1990). It is now obvious to suggest that there is a connection between the UBD of CSB and the activity of the ubiquitin ligase complex containing CSA. The CSA-Cullin complex might, for example, ubiquitylate a target in the TC-NER complex, which is then contacted by CSB via its UBD, triggering damage incision. Alternatively, or additionally, CSA (whose activity is negatively controlled in a poorly understood fashion by the COP9/signalosome [CSN] [Groisman et al., 2003]) might somehow regulate functionally important recycling of CSB, and such recycling would be defective in cells lacking the UBD. In any case, the proposed “ubiquitin ligase - UBD double act” would be a late evolutionary add-on, found only in mammalian cells. It might, for example, have developed as a “checkpoint” ensuring that all proteins required for successful repair around damage-stalled RNAPII are correctly assembled, helping uphold the integrity of the complex genomes of higher cells. Addressing this and other possibilities raised by our results is an important goal in the quest to unravel the mechanism of TC-NER.

In summary, the discovery of a ubiquitin-binding domain in CSB represents an important advance in the field of TC-NER. Numerous questions about the mechanism of TC-NER remain unanswered, but our findings constitute a foundation on which the function of CSA and CSB may be pursued in the context of hypotheses that can be experimentally tested.

Experimental Procedures

Details on plasmids and cell lines can be found in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Ubiquitin Binding Experiments

GST, UBDWT, UBDGG, GST-ubiquitin, and GST-ubiquitinI44A expressed in BL21 were purified and immobilized on glutathione-sepharose. Whole cell extract was prepared from HEK293 cells expressing CSBWT or CSBGG. K-63 and K-48 linked polyubiquitin chains (Biomol) were dissolved (50 μg/ml, final concentration) in binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 200 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 15% glycerol) containing 50 μg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA). Human cell extract, or mixed-length K-48-linked or K-63-linked multiubiquitin chains, were then incubated with the affinity matrices for 2 hr at 4°C. After washing extensively with binding buffer, proteins were eluted with SDS-PAGE sample buffer and analyzed by western blot with anti-ubiquitin monoclonal antibody (Stressgen).

Protein Purification and ATPase Assay

Epitope-tagged CSB constructs were transfected into 293T cells using calcium phosphate, and overexpressed proteins were purified on M2-agarose beads (Sigma) by affinity chromatography. Details are available on request. Measurements of ATPase activity was performed in 15 μl reactions in 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 4% glycerol, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 100 μM cold ATP, 2.5 μM of [α-32P] ATP (800Ci/mmol), 80 μg BSA, and in the presence of CSBWT or CSBdel (50–80 μM) for 60 min at 30°C. Where indicated, the reaction was supplemented with 125 ng double-stranded λ-DNA (NEB). A 2 μl aliquot of the reaction was spotted onto a CEL300PEI-cellulose plate (Machery-Nagel) to separate ADP and ATP by thin-layer chromatography in 1 M formic acid, 0.3 M LiCl, and results were visualized by Phosphorimager exposure.

Survival and Recovery of RNA Synthesis after UV Irradiation

UV sensitivity of the CSB cell lines was determined by clonogenic survival assay as described previously (Rockx et al., 2000). Cells were fixed and stained using published methods (Franken et al., 2006). To measure RNA synthesis after UV irradiation, cells were pulse labeled with 3H-uridine as described elsewhere (Vermeulen et al., 2001).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

ChIP of RNAPII and CSB at the DHFR promoter was done as described previously (Proietti-De-Santis et al., 2006).

In Vivo Crosslinking and Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

Formaldehyde crosslinking and immunoprecipitation was performed as described elsewhere (Fousteri et al., 2006).

Fluorescence Recovery after Photobleaching

FRAP experiments were performed as described previously (Giglia-Mari et al., 2006). Briefly, FRAP was conducted at high time resolution on a Zeiss LSM 510 meta confocal laser scanning microscope. A narrow strip spanning the nucleus of a cell was monitored every 200 ms at 1% laser intensity (30 mW Argon laser, current set at 6.5 A, 514 nm line) until the fluorescence signal reached a steady level (4 s). The same strip was then photobleached for 60 ms at the maximum laser intensity. Recovery of fluorescence in the strip was then monitored every 200 ms for about 30 s (1% laser intensity). All FRAP data were normalized to the average prebleached fluorescence after removal of the background signal. All FRAP curves represent an average of at least ten measured cells.

TC-NER Assay

The in vivo assay of TC-NER was performed essentially as described elsewhere (Spivak et al., 2006), using 20 J/m2 UV irradiation. Briefly, HindIII-digested/T4 EndoV-treated DNA from the relevant cell lines was transferred to a membrane by Southern blotting. The membrane was probed with strand-specific probes recognizing a 5366 bp HindIII fragment in exon 5 of the endogenous DHFR gene.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from Cancer Research UK (to J.Q.S.). Work in the Svejstrup, Mullender, Vermeulen, and Egly laboratories was supported by a grant from the European Community (Integrated Project DNA repair, grant no. LSHG-CT-2005-512113). P.-O.M. and G.G.-M. were funded by the Association for International Cancer Research (AICR 07-0129), a “Young Researcher Program” ATIP(CNRS)/InCa (France), and Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (ARC, France) (contract for equipment n: 8505). We thank Dr Camille Godon for the technical assistance, Dr. Dominik Boos for suggestions, and Svejstrup lab members for helpful discussions.

Published: June 10, 2010

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures and three figures and can be found with this article online at doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2010.04.017.

Supplemental Information

References

- Anindya R., Aygun O., Svejstrup J.Q. Damage-induced ubiquitylation of human RNA polymerase II by the ubiquitin ligase Nedd4, but not Cockayne syndrome proteins or BRCA1. Mol. Cell. 2007;28:386–397. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergink S., Salomons F.A., Hoogstraten D., Groothuis T.A., de Waard H., Wu J., Yuan L., Citterio E., Houtsmuller A.B., Neefjes J. DNA damage triggers nucleotide excision repair-dependent monoubiquitylation of histone H2A. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1343–1352. doi: 10.1101/gad.373706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia P.K., Verhage R.A., Brouwer J., Friedberg E.C. Molecular cloning and characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAD28, the yeast homolog of the human Cockayne syndrome A (CSA) gene. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:5977–5988. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.20.5977-5988.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienko M., Green C.M., Crosetto N., Rudolf F., Zapart G., Coull B., Kannouche P., Wider G., Peter M., Lehmann A.R. Ubiquitin-binding domains in Y-family polymerases regulate translesion synthesis. Science. 2005;310:1821–1824. doi: 10.1126/science.1120615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Shinde U., Ortolan T.G., Madura K. Ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domains in Rad23 bind ubiquitin and promote inhibition of multi-ubiquitin chain assembly. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:933–938. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citterio E., Rademakers S., van der Horst G.T., van Gool A.J., Hoeijmakers J.H., Vermeulen W. Biochemical and biological characterization of wild-type and ATPase- deficient Cockayne syndrome B repair protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:11844–11851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citterio E., Van Den Boom V., Schnitzler G., Kanaar R., Bonte E., Kingston R.E., Hoeijmakers J.H., Vermeulen W. ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling by the Cockayne syndrome B DNA repair-transcription-coupling factor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:7643–7653. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.20.7643-7653.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinant C., de Jager M., Essers J., van Cappellen W.A., Kanaar R., Houtsmuller A.B., Vermeulen W. Activation of multiple DNA repair pathways by sub-nuclear damage induction methods. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:2731–2740. doi: 10.1242/jcs.004523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fousteri M., Vermeulen W., van Zeeland A.A., Mullenders L.H. Cockayne syndrome A and B proteins differentially regulate recruitment of chromatin remodeling and repair factors to stalled RNA polymerase II in vivo. Mol. Cell. 2006;23:471–482. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franken N.A., Rodermond H.M., Stap J., Haveman J., van Bree C. Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:2315–2319. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg E.C., Walker G.C., Siede W., Wood R.D., Schultz R.A., Ellenberger T. Second Edition. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2005. DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. [Google Scholar]

- Giglia-Mari G., Miquel C., Theil A.F., Mari P.O., Hoogstraten D., Ng J.M., Dinant C., Hoeijmakers J.H., Vermeulen W. Dynamic interaction of TTDA with TFIIH is stabilized by nucleotide excision repair in living cells. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groisman R., Kuraoka I., Chevallier O., Gaye N., Magnaldo T., Tanaka K., Kisselev A.F., Harel-Bellan A., Nakatani Y. CSA-dependent degradation of CSB by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway establishes a link between complementation factors of the Cockayne syndrome. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1429–1434. doi: 10.1101/gad.378206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groisman R., Polanowska J., Kuraoka I., Sawada J., Saijo M., Drapkin R., Kisselev A.F., Tanaka K., Nakatani Y. The ubiquitin ligase activity in the DDB2 and CSA complexes is differentially regulated by the COP9 signalosome in response to DNA damage. Cell. 2003;113:357–367. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanawalt P.C., Spivak G. Transcription-coupled DNA repair: two decades of progress and surprises. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:958–970. doi: 10.1038/nrm2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann K. Ubiquitin-binding domains and their role in the DNA damage response. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2009;8:544–556. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley J.H., Lee S., Prag G. Ubiquitin-binding domains. Biochem. J. 2006;399:361–372. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaspers N.G., Raams A., Kelner M.J., Ng J.M., Yamashita Y.M., Takeda S., McMorris T.C., Hoeijmakers J.H. Anti-tumour compounds illudin S and Irofulven induce DNA lesions ignored by global repair and exclusively processed by transcription- and replication-coupled repair pathways. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2002;1:1027–1038. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00166-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang R.S., Daniels C.M., Francis S.A., Shih S.C., Salerno W.J., Hicke L., Radhakrishnan I. Solution structure of a CUE-ubiquitin complex reveals a conserved mode of ubiquitin binding. Cell. 2003;113:621–630. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00362-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley L.A., MacCallum R.M., Sternberg M.J. Enhanced genome annotation using structural profiles in the program 3D-PSSM. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;299:499–520. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laine J.P., Egly J.M. Initiation of DNA repair mediated by a stalled RNA polymerase IIO. EMBO J. 2006;25:387–397. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laine J.P., Egly J.M. When transcription and repair meet: a complex system. Trends Genet. 2006;22:430–436. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann A.R. DNA repair-deficient diseases, xeroderma pigmentosum, Cockayne syndrome and trichothiodystrophy. Biochimie. 2003;85:1101–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licht C.L., Stevnsner T., Bohr V.A. Cockayne syndrome group B cellular and biochemical functions. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;73:1217–1239. doi: 10.1086/380399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mari P.O., Florea B.I., Persengiev S.P., Verkaik N.S., Bruggenwirth H.T., Modesti M., Giglia-Mari G., Bezstarosti K., Demmers J.A., Luider T.M. Dynamic assembly of end-joining complexes requires interaction between Ku70/80 and XRCC4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:18597–18602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609061103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marteijn J.A., Bekker-Jensen S., Mailand N., Lans H., Schwertman P., Gourdin A.M., Dantuma N.P., Lukas J., Vermeulen W. Nucleotide excision repair-induced H2A ubiquitination is dependent on MDC1 and RNF8 and reveals a universal DNA damage response. J. Cell Biol. 2009;186:835–847. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200902150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayne L.V., Lehmann A.R. Failure of RNA synthesis to recover after UV irradiation: an early defect in cells from individuals with Cockayne's syndrome and xeroderma pigmentosum. Cancer Res. 1982;42:1473–1478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayne L.V., Priestley A., James M.R., Burke J.F. Efficient immortalization and morphological transformation of human fibroblasts by transfection with SV40 DNA linked to a dominant marker. Exp. Cell Res. 1986;162:530–538. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(86)90356-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellon I., Spivak G., Hanawalt P.C. Selective removal of transcription-blocking DNA damage from the transcribed strand of the mammalian DHFR gene. Cell. 1987;51:241–249. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman J.C., Bailey A.D., Weiner A.M. Cockayne syndrome group B protein (CSB) plays a general role in chromatin maintenance and remodeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:9613–9618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510909103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouspikel T., Hanawalt P.C. Impaired nucleotide excision repair upon macrophage differentiation is corrected by E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:16188–16193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607769103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osley M.A., Fleming A.B., Kao C.F. Histone ubiquitylation and the regulation of transcription. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 2006;41:47–75. doi: 10.1007/400_006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prag G., Misra S., Jones E.A., Ghirlando R., Davies B.A., Horazdovsky B.F., Hurley J.H. Mechanism of ubiquitin recognition by the CUE domain of Vps9p. Cell. 2003;113:609–620. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00364-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proietti-De-Santis L., Drane P., Egly J.M. Cockayne syndrome B protein regulates the transcriptional program after UV irradiation. EMBO J. 2006;25:1915–1923. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rademakers S., Volker M., Hoogstraten D., Nigg A.L., Mone M.J., Van Zeeland A.A., Hoeijmakers J.H., Houtsmuller A.B., Vermeulen W. Xeroderma pigmentosum group A protein loads as a separate factor onto DNA lesions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:5755–5767. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5755-5767.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockx D.A., Mason R., van Hoffen A., Barton M.C., Citterio E., Bregman D.B., van Zeeland A.A., Vrieling H., Mullenders L.H. UV-induced inhibition of transcription involves repression of transcription initiation and phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:10503–10508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180169797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell J.D., Hicke L. Non-traditional functions of ubiquitin and ubiquitin-binding proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:35857–35860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R300018200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spivak G., Pfeifer G.P., Hanawalt P. In vivo assays for transcription-coupled repair. Methods Enzymol. 2006;408:223–246. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)08014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svejstrup J.Q. Mechanisms of transcription-coupled DNA repair. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;3:21–29. doi: 10.1038/nrm703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svejstrup J.Q. Rescue of arrested RNA polymerase II complexes. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:447–451. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tantin D., Kansal A., Carey M. Recruitment of the putative transcription-repair coupling factor CSB/ERCC6 to RNA polymerase II elongation complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:6803–6814. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.6803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troelstra C., van Gool A., de Wit J., Vermeulen W., Bootsma D., Hoeijmakers J.H. ERCC6, a member of a subfamily of putative helicases, is involved in Cockayne's syndrome and preferential repair of active genes. Cell. 1992;71:939–953. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90390-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich H.D. Regulating post-translational modifications of the eukaryotic replication clamp PCNA. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2009;8:461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Boom V., Citterio E., Hoogstraten D., Zotter A., Egly J.M., van Cappellen W.A., Hoeijmakers J.H., Houtsmuller A.B., Vermeulen W. DNA damage stabilizes interaction of CSB with the transcription elongation machinery. J. Cell Biol. 2004;166:27–36. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200401056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gool A.J., Citterio E., Rademakers S., van Os R., Vermeulen W., Constantinou A., Egly J.M., Bootsma D., Hoeijmakers J.H. The Cockayne syndrome B protein, involved in transcription-coupled DNA repair, resides in an RNA polymerase II-containing complex. EMBO J. 1997;16:5955–5965. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.19.5955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hoffen A., Natarajan A.T., Mayne L.V., van Zeeland A.A., Mullenders L.H., Venema J. Deficient repair of the transcribed strand of active genes in Cockayne's syndrome cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5890–5895. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.25.5890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varadan R., Assfalg M., Raasi S., Pickart C., Fushman D. Structural determinants for selective recognition of a Lys48-linked polyubiquitin chain by a UBA domain. Mol. Cell. 2005;18:687–698. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venema J., Mullenders L.H., Natarajan A.T., van Zeeland A.A., Mayne L.V. The genetic defect in Cockayne syndrome is associated with a defect in repair of UV-induced DNA damage in transcriptionally active DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:4707–4711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen W., Rademakers S., Jaspers N.G., Appeldoorn E., Raams A., Klein B., Kleijer W.J., Hansen L.K., Hoeijmakers J.H. A temperature-sensitive disorder in basal transcription and DNA repair in humans. Nat. Genet. 2001;27:299–303. doi: 10.1038/85864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Zhai L., Xu J., Joo H.Y., Jackson S., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Xiong Y., Zhang Y. Histone H3 and H4 ubiquitylation by the CUL4-DDB-ROC1 ubiquitin ligase facilitates cellular response to DNA damage. Mol. Cell. 2006;22:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood R.D., Araujo S.J., Ariza R.R., Batty D.P., Biggerstaff M., Evans E., Gaillard P.H., Gunz D., Koberle B., Kuraoka I. DNA damage recognition and nucleotide excision repair in mammalian cells. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2000;65:173–182. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2000.65.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q., Wani G., Arab H.H., El-Mahdy M.A., Ray A., Wani A.A. Chromatin restoration following nucleotide excision repair involves the incorporation of ubiquitinated H2A at damaged genomic sites. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2009;8:262–273. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zotter A., Luijsterburg M.S., Warmerdam D.O., Ibrahim S., Nigg A., van Cappellen W.A., Hoeijmakers J.H., van Driel R., Vermeulen W., Houtsmuller A.B. Recruitment of the nucleotide excision repair endonuclease XPG to sites of UV-induced dna damage depends on functional TFIIH. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:8868–8879. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00695-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.