Abstract

The translocation of macromolecules through a nanopore requires the impingement of the molecules at the pore followed by threading through the pore. While most of the discussion on the translocation phenomenon focused so far on the threading process, the phenomenology on the frequency of encounters between the polymer and the pore exhibits diverse features in terms of polymer length, solution conditions, driving force, and pore geometry. We derive a general theory for the capture rate of polyelectrolyte molecules and the probability of successful translocation through a nanopore, under an externally imposed electric field. By considering the roles of entropic barrier at the pore entrance and drift of the polyelectrolyte under the electric field, we delineate two regimes: (a) entropic barrier regime and (b) drift regime. In the first regime dominated by the entropic barrier for the polyelectrolyte, the capture rate is an increasing nonlinear function in the electric field and chain length. In the drift regime, where the electric field dwarfs the role of entropic barriers, the capture rate is independent of chain length and linear in electric field. An analytical formula is derived for the crossover behavior between these regimes, and the general results are consistent with various experimentally observed trends.

INTRODUCTION

The translocation of a polyelectrolyte molecule through protein channels and solid-state nanopores, under an externally imposed electric field, exhibits rich phenomenology.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 In the single-molecule electrophysiology experiments, which is widely used to study polymer translocation, the ionic current through a pore in most experiments shows a temporary reduction whenever the polymer encounters the pore. The frequency of such encounters between the polymer and pore, as measured through temporary ionic current blockades, depends on many experimental variables such as the polymer concentration, polymer length, polymer sequence, pore geometry, chemical decoration of the pore, ionic strength, applied voltage difference, and gradients in hydrostatic pressure and salt concentrations across the pore. Only a certain fraction of these encounters results in the eventual completion of the translocation process, with its value again depending on the experimental variables. The latter threading process has already received substantial attention. In the present paper, we address the process of polyelectrolyte capture by the pore under an electric field.

Some of the typical results from experiments are as follows. Let Jc denote the rate of capture of the polymer of chain length N by the pore. Jc is the inverse of the average arrival time ⟨ta⟩ between any two successive events of ionic current blockades as observed in the ionic current traces in the single-molecule electrophysiology experiments. Alternatively, a histogram of ta may be constructed, such as exp(−Jcta), and Jc can then be extracted. The capture rate Jc was shown3 to depend on applied voltage difference Vm exponentially, above a threshold value, for biotinylated poly(dC)30 through α-hemolysin (αHL) pore in 1M KCl. Furthermore, the dependence of Jc on the voltage bias depended on the direction of the pore through which the polymer was pulled. In contrast, two exponentials were reported9 for the capture of poly(dC)40 through αHL in 1M KCl indicating two activated processes at low and high voltage difference regimes. For the capture of ds-DNA by a solid-state nanopore (3–4 nm in diameter), Jc was found15 to increase with Vm first exponentially, and then linearly for higher values of Vm. In this case, the chain length dependence of Jc showed an N-independent regime for large N and sharper increasing dependence on N for lower N values. In all these experiments, Jc was found to be linearly proportional to the polymer concentration c. The major objective of the present paper is to derive an expression for Jc in terms of the chain length N, polymer concentration c, and the applied voltage difference Vm, in order to delineate different regimes showing the above behaviors.

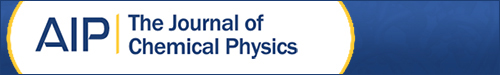

Basically, there are three stages in the process of single-file polymer translocation through a structureless blunt nanopore, as sketched in Fig. 1: (1) drift diffusion, (2) capture, and (3) translocation. In the first step, the polymer undergoes a combination of drift due to the externally imposed electric field and diffusion arising from collisions by solvent molecules. Near the pore, the flow field and the electric field can be significantly influenced by electro-osmotic forces, dielectric mismatch between the pore wall and the aqueous medium, ionic strength gradients, and pressure gradients across the pore. Depending on the details of these contributing factors, the nature of the flow field within a range of rc from the pore can be qualitatively different from that outside this range. rc can vary between subnanometers and micrometers. Within the range rc, the polymer may undergo conformational deformation as well. By experiencing these forces within rc, the polymer approaches the pore mouth, designated as stage 2 in Fig. 1a. In general, when the polymer reaches the pore mouth, it is in a jammed state without any initial correlation between the chain end and pore mouth. The third stage consists of three steps: (a) chain end localization, (b) nucleation, and (c) threading. The placement of one of the chain ends at the pore mouth, to enable the eventual single-file translocation, from a jammed coil state requires an entropic barrier. This step is designated as A→B in Figs. 1b, 1c. After the localization of the chain end, there is an additional entropic barrier for reducing the conformational degrees of freedom for the chain.16, 17, 18, 19 Only if sufficient number of monomers cross this “nucleation barrier,” the chain can undergo further translocation. This nucleation stage is B→C in Figs. 1b, 1c. The final threading step, C→D, is usually a down-hill process, which in its own right is a drift-diffusion process.17, 18, 19, 20, 21 The sketch of the shape of the free energy profile in Fig. 1b is based on the previous calculations.16, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 The free energy landscape sketched in Fig. 1 can be richer due to the chemical decorations of the pore and the pore geometry.

Figure 1.

(a) Three main stages of polymer translocation process: (1) drift diffusion, (2) capture, and (3) translocation; (b) free energy landscape; (c) three stages in the third translocation step. The set of sketches (a)–(c) is for one single event of translocation.

The main generic question in the present context is how a free energy barrier arising essentially from polymer entropy and an external driving force from the electric field combine to give the capture rate for a polyelectrolyte in translocation experiments through nanopores. We present below the simplest model for addressing this issue and analytical results for this model. Depending on the relative dominance of the entropic barrier with respect to the drift arising from the externally imposed electric field, we identify two regimes, namely, the entropic barrier regime and the drift regime. In the entropic barrier regime, Jc increases nonlinearly with both Vm and N. In the drift regime, operative for larger Vm and larger N, Jc is linear in electric field and is independent of chain length. In both regimes, Jc is directly proportional to the polymer concentration c. A crossover formula, connecting these two regimes, is derived in the steady state, and the predictions are compared to available experimental data.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The model and the theory addressing the simultaneous effects of free energy barrier and electric field are presented in Sec. 2. The results on the dependence of Jc on Vm and N are discussed in Sec. 3, followed by conclusions in Sec. 4.

MODEL AND THEORY

We map the encounter of the polymer at the pore and its eventual escape into either the donor or the receiver compartment as a one-dimensional stochastic process of the polymer chain negotiating the free energy landscape sketched in Fig. 1b under an applied voltage difference across the pore. Starting from the conservation of the number of polymer chains in the system, we derive below the steady state flux by imposing appropriate boundary conditions. We identify the steady state flux as the capture rate Jc defined in Sec. 1. The basic elements of the model are presented in Fig. 1, as the drift diffusion, capture, and the entropic barrier for the translocation process. Let us consider the variation in the number concentration of the polyelectrolyte molecules c(x,t) at time t along the x-direction, which is chosen along the pore axis from the donor compartment to the receiver compartment. The time evolution of c(x,t) is given by the continuity equation

| (1) |

where J(x,t) is the net flux of the molecules at location x and time t. The flux has the diffusive and convective parts,

| (2) |

where D is the diffusion coefficient of the polymer molecule and v(x,t) is the x-component of the net velocity of molecules at position x and time t. In writing the above equation, intermolecular interactions are ignored corresponding to an infinitely dilute polyelectrolyte solution in the donor compartment. For the typical pore geometry sketched in Fig. 1, a cylindrical coordinate system must be used as in Ref. 25 and the local concentration of the polymer depends on the radial distance from the pore. While the mathematical details are simpler in the one-dimensional description here, the physics is unaltered for the present problem. Therefore, we take c(x,t) as the local polyelectrolyte concentration along the central axis of the pore in the direction of transport. Also, we take the x-value for the polymer to be its center-of-mass value.

The velocity of the molecules arises from both the externally imposed force fields and the local gradients in the free energy landscape F(x) [which is sketched in Fig. 1b]. Examples of the externally imposed force fields are an electric field E and a pressure gradient ∂p∕∂x. If the pore bears some residual charges, the externally imposed electric field creates an electro-osmotic flow as well.10, 25, 26, 27 In general, the net velocity is

| (3) |

where vext is the velocity field generated by pressure gradients and electro-osmotic flow. μ is the electrophoretic mobility and ζ is the friction coefficient obeying the Einstein relation,

| (4) |

with kBT being the Boltzmann constant times the absolute temperature. In writing the above equation, we have assumed that the free energy landscape is time independent.

In the present paper, we consider simpler situations where there are no pressure gradients and no permanent charges are on the pore so that vext=0. The effects from ∂p∕∂x and the electro-osmotic flow can readily be added in the final expressions derived below if necessary. Substitution of Eq. 3 into Eq. 2 yields

| (5) |

with

| (6) |

By writing E as the negative gradient of the electric potential V(x) at x, the flux is given by

| (7) |

The three terms on the right hand side of Eq. 7 represent the contributions from the diffusion, drift, and free energy barrier, respectively.

Diffusion

For dilute solutions, the diffusion coefficient of the polyelectrolyte in sufficiently salty solutions obeys the Stokes–Einstein law,28, 29

| (8) |

where Rg is the radius of gyration of the polymer and η0 is the viscosity of the solution. Writing Rg∼Nν, where ν is the size exponent for the polymer, the N-dependence of D is given as

| (9) |

In solutions with high salt concentrations, the size exponent of a polyelectrolyte molecule is approximately the same as that of uncharged polymer molecules in good solvents, with ν≃0.6. Therefore,

| (10) |

The above equations for D are valid only if the electrostatic interaction among the polymer segments is fully screened. If the concentration of the salt is not high enough, the dynamics of the polyelectrolyte molecule gets strongly coupled to that of its counterions.30 This coupling results in a dramatic increase in D as the salt concentration is reduced. In fact, under these circumstances, the coupled diffusion coefficient Dc becomes independent28, 30 of N,

| (11) |

If we were to be interested in the flux due to polymer diffusion in salt-free solutions or very low salt concentrations, then Eqs. 1, 2 are insufficient and they should be accompanied by analogous equations for the time evolution of counterions. Since almost all experiments dealing with single-molecule translocation processes have a large amount of electrolytes, Eqs. 8, 9, 10 are sufficient for the discussion of the diffusion coefficient in the present paper.

The diffusion-limited regime arises when the second and third terms in Eq. 7 are negligible in comparison with the diffusion term. In this limit, the expression for the flux of the molecules into an absorbing domain, such as a pore embedded in a membrane, is well known. The capture rate of the molecules in the steady state by the absorbing domain is given by the law31, 32, 33

| (12) |

where the proportionality factor depends on the geometry of the absorbing domain. For example, if the absorbing boundary is a pore of diameter d embedded in a sheet separating the donor and receiver compartments, the proportionality factor is πd. In view of Eqs. 8, 9, 10 for salty solutions, the capture rate in the diffusion-limited regime is

| (13) |

Therefore, in the diffusion-limited regime, the capture rate decreases with chain length and is linear in the polymer concentration.

Drift

The second term on the right hand side of Eq. 7 is due to the electrophoretic movement of the polyelectrolyte molecules. If the moving species is an ion from the electrolyte or an isolated counterion, its electrophoretic mobility μ is given by the Einstein law,

| (14) |

where z is the charge of the moving species. If one were to assume that the Einstein law for the electrophoretic mobility of a simple ion is applicable also to a polyelectrolyte molecule of net charge Q, μ would be expected to be

| (15) |

This expectation is erroneous, as the polyelectrolyte molecule is not behaving like a simple ion. The macromolecule is strongly correlated with its counterion cloud.34, 35 Since the volume occupied by the macromolecule is larger than the local volume within which the electroneutrality is maintained on an average, the hydrodynamic correlations among the polymer segments and the net movement of the polymer are coupled to those of the counterion cloud. Experimental data29 on direct measurements of D and μ for different values of N have clearly demonstrated the inapplicability of the Einstein relation, Eq. 15, for the coupled polyelectrolyte-counterion system. The manifestation of this coupling is the fact that the electrophoretic mobility of a polyelectrolyte chain is independent of its chain length N, at all salt concentrations,

| (16) |

where the proportionality factor decreases with the salt concentration. It has been theoretically shown that35

| (17) |

where Θ(Rg∕ξD) is the factor arising from the coupling of the dynamics of the polyelectrolyte and the counterions. This is a function of the ratio of the radius of gyration of the polyelectrolyte to the Debye length ξD, which is proportional to the inverse square root of the salt concentration . By using the formula given in Ref. 32, the crossover function Θ(Rg∕ξD) depends on N according to

| (18) |

where ν is the effective size exponent and its value depends on the salt concentration. Defining the function

| (19) |

the net result is

| (20) |

where f(cs) is a decreasing function of the salt concentration and the electrophoretic mobility is independent of the chain length at all salt concentrations.

In the drift-dominated regime, where the first and third terms on the right hand side of Eq. 7 are negligible in comparison with the electrophoretic term, the constant flux in the steady state follows from Eqs. 1, 2 as

| (21) |

If Vm is the voltage difference that drives the negatively charged polymer from the donor compartment toward the positive electrode placed in the receiver compartment, it follows from Eqs. 20, 21 that

| (22) |

Therefore, in the drift-limited regime, where the effects of the diffusion and barrier may be ignored, the polymer flux is linearly proportional to the polymer concentration and the applied voltage difference, and is independent of the chain length.

Barrier

As already mentioned, when the chain approaches the pore entrance, it is in a jammed state with one chain end not necessarily at the pore for further threading as a single file. As illustrated in Fig. 1c, the chain end must unravel from a high monomer density jammed state in order to place itself at the pore entrance. This requires an entropic barrier. Let this entropic barrier for the localization of one chain end be . In addition to this part, there is a free energy barrier for squeezing the chain inside the pore. The latter arises from conformational changes in the polymer accompanying the confinement inside the pore, and let denote this contribution. Adding these two parts, the total free energy barrier F† is

| (23) |

The confinement part of the free energy barrier is discussed extensively in literature36, 37, 38 and it depends on the pore characteristics, such as the diameter, interaction energy between the polymer and pore surface, and polymer chain statistics reflecting the solvent quality and chain stiffness.

The free energy barrier for localizing a chain end at the pore mouth is difficult to estimate. For a polyelectrolyte chain confined in a small volume, various factors arising from chain conformations, distribution of counterion cloud around the polymer, electrostatic interaction among all charged species inside the confining volume, and solvent entropy contribute to . Due to the nonlinear coupling among the various contributing factors, numerical work is necessary to estimate . We have recently derived39 a self-consistent field theory to address . Here the small ions are treated at the level of the Poisson–Boltzmann prescription. The polymer conformations are treated with potentials arising from the self-generated excluded volume effects (from both the hydrophobic and electrostatic) and the ionic environment around the polymer. By a self-consistent procedure, we have computed the various contributions to the free energy from electrostatic interactions, conformational changes of the chain, correlations of ions, and solvent entropy. The computed results show that is mainly due to chain entropy. In general, is a nonmonotonic function of N, for a fixed confining volume. For sufficiently large values of N such that the monomer volume fraction is higher than about 0.1, is found to decrease with N according to

| (24) |

The error of ±0.1 in the apparent exponent α is due to the imposed variations in the salt concentration and the hydrophobic interaction. As discussed in Ref. 39, the reduction in the free energy barrier with the chain length originates from the entropic pressure created by the confining region to push the chain end in the direction of the pore entrance.

This trend is opposite to that of , associated with chain nucleation into the pore and for full confinement inside the pore. For example, for full confinement within a cylindrical pore of diameter d, is extensive in N so that36

| (25) |

In general, the free energy barrier sketched in Fig. 1b is a complicated function of the characteristics of the pore and polymer. Nevertheless, in the simplest situation of a narrow hole embedded in a thin membrane, the free energy barrier is dominated by . If the chain is caught inside a small region in front of the pore mouth, where the electric potential gradient is the strongest, decreases with N for sufficiently long chains. The discussion below in this section is valid for any free energy landscape F(x) and the consequences of these results for the simplest model mentioned above will be presented in Sec. 2D.

General result

By writing D as a common factor for all terms in Eq. 7 and using the definition of according to Eq. 20, we get

| (26) |

This equation can be rearranged as

| (27) |

If the length of the pore is L, extending from 0 to L along the x-direction, the steady state flux (being a constant, independent of x) follows by integrating Eq. 27 between the limits of 0 and L as

| (28) |

This equation is identical to the Goldman–Hodgkin–Katz current equation40 for transport of small ions through ion channels, generalized here to the movement of polyelectrolyte molecules. The function defined through Eq. 19 plays the role of the effective charge in units of kBT for the translocation of a charged macromolecule.

Probability of successful translocation

With the polyelectrolyte concentration being very low in the translocation experiments, the polymer concentration c(x,t) in Eq. 1 can be equivalently taken as the probability W(x,t) of finding a chain at x and time t. With this interpretation, the continuity equation is the Fokker–Planck equation,

| (29) |

where

| (30) |

with

| (31) |

and

| (32) |

The probability distribution of the first passage time and its moments can be obtained from the Fokker–Planck equation for general situations of and V(x), by following the standard procedures.41, 42, 43 In the present context, the average translocation time is the mean first passage time, which can be calculated by choosing the appropriate boundary conditions for W(x,t).

Once the chain is caught at the pore mouth, the probability of successful translocation is obtained as follows. We imagine that the polymer is at some location x0 very close to the entrance within the pore of length L. Alternatively, we can imagine that the actual pore is extended a bit inside the donor region to include the jammed state of the polymer. Given the initial location of the captured polymer at x0(0≤x0≤L), the probability of successful translocation is the probability that the stochastic process given by Eq. 29 attains the value x=L for the first time without ever reaching the other boundary at x=0. This probability Π+ follows from Eqs. 29, 30, 31, 32 as41, 42, 43

| (33) |

Using the absorbing boundary conditions, Π+(x0=0)=0 and Π+(x0=L)=1, the solution of Eq. 33 is

| (34) |

where

| (35) |

The model presented here specifically addresses the conformational attributes and the charged nature of the polyelectrolyte chain with its coupling to the counterion dynamics. The Fokker–Planck formalism has recently been used in the context of structureless particles undergoing translocation.44, 45, 46

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

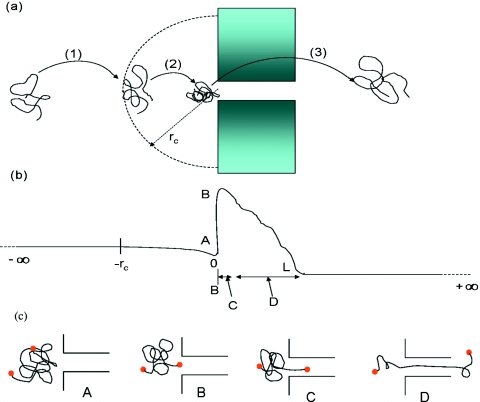

The consequences of the equations derived above for the steady state flux of polymer capture and the probability of the successful translocation of the captured polymer are illustrated here with the simplest situation sketched in Fig. 2. In general, the free energy barrier can have rich features including one or more metastable states. The simplest scenario considered here is sufficient to delineate the regimes for polymer capture by the pore. The pore is of length L along the x-direction. We have chosen the pore to include a small distance in the donor compartment where the electric field becomes strong to capture the polymer. Alternatively, we can define a distance a0 in front of the pore where the chain is initially captured and the pore can be taken as a composite pore of effective length L+a0. As the final physical results are not going to be changed by the parameter a0, we assume that L is the effective length of the pore. The free energy maximum (in units of kBT) arises due to the entropic barrier associated with the search by the chain end for the pore entrance, energy of interaction between the polymer and pore, and conformational changes in the polymer accompanying the nucleation stage of the translocation. Let this maximum occur at a distance ηL from the pore boundary at the donor side. In order to make the calculated results physically transparent, we assume that the free energy variation is ramplike, as sketched in Fig. 2b. In fact, in the presence of an electric field, the gain in electrostatic energy is quadratic in x as the translocation proceeds along the pore.7, 21 When the barrier is steep, the usual saddle-point approximation can be made resulting in the Kramers-like formulas. For weak barriers, saddle-point approximation is not sufficient. The present choice of ramplike profile allows simple analytical formulas that capture the Kramers-like results for steep barriers and the correct limits for weak barriers. Therefore, we restrict our discussion only to a ramplike profile given by

| (36) |

Here and η are taken as parameters. It must be emphasized that the above choice is made only for illustrative purposes and transparency of the physics in the analytical results. A more complicated from either our previous calculations21, 22, 23, 24, 25 for particular pores or new expressions can be used instead.

Figure 2.

Model of free energy barrier and voltage gradient.

For the variation in the electric potential across the pore, we assume that the electric field is uniform, as depicted in Fig. 2c, with the electrode in the receiver compartment,

| (37) |

with

| (38) |

Assuming that the polymer charge is negative, is sketched in Fig. 2d. Combining the free energy associated with the encounter of polymer with the pore and the electric potential gradient, the net free energy curve is [Fig. 2e]

| (39) |

The total free energy barrier is

| (40) |

and the free energy gain in the translocation process is

| (41) |

As marked in Fig. 2b, we choose x0 as the initial position in the calculation of the probability of successful translocation.

Capture rate

Substitution of Eq. 39 into Eq. 28 gives the steady state capture rate in terms of the two parameters and η, and the net free energy gain . We assume further that the polymer concentration in the receiver compartment is negligible, c(L)≃0, as the polymer chains continuously get removed from the pore after successful translocation events. The other boundary condition is that c(0) is the same as the polymer concentration c in the donor compartment. As a result, we get

| (42) |

where the free energy barrier is given in Eq. 40.

The dependence of on chain length, as given by Eq. 42, can be addressed by incorporating the N-dependence of the free energy barrier. We take Eq. 24 to describe the entropic barrier,

| (43) |

Furthermore, and D are N-dependent. Writing the N-dependence of as

| (44) |

where the coefficient z0 is related to the function Θ(Rg∕ξD), was given in Eq. 19. Also, we rewrite Eq. 9 for D as

| (45) |

Substituting Eqs. 43, 44, 45 into Eq. 42, the N-dependence of the steady state flux can be calculated.

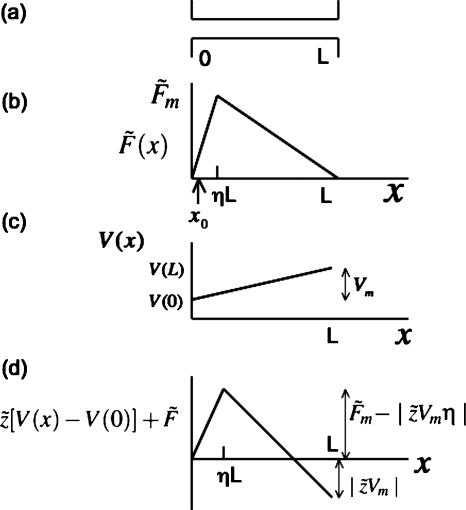

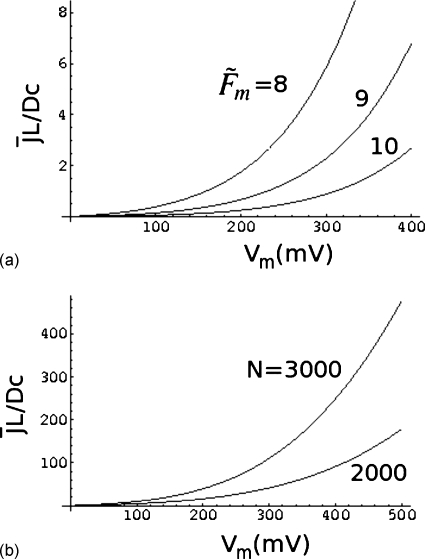

A typical result given by Eq. 42 is presented in Figs. 3a, 3b. In Figs. 3a, 3b, is plotted against for and η=0.1. The values of the parameters are typical of experimental conditions, essentially based on the fact that the applied voltage of 25 mV corresponds to room temperature, and the entropic barriers are about 10kBT–20kBT based on our earlier theory. As is clear from Fig. 3b, the steady state flux is linear in the electric potential difference Vm for very large values of Vm, above an apparent threshold value of . It must be mentioned that this threshold value does not indicate an on∕off process. There are always a finite number of capture events for voltage differences even below the threshold value, as is evident from Fig. 3a. In fact, in the limit of , Eq. 42 reduces identically to

| (46) |

In view of Eq. 20, , the steady state flux for high voltage differences can be written as

| (47) |

which is exactly the same as the drift-limited result given by Eq. 22. Therefore, we mark the high voltage difference regime as the drift-dominated regime, whereas the lower voltage difference regime as the entropic barrier regime. The crossover occurs at .

Figure 3.

Plot of reduced polymer flux against the reduced voltage difference.

In the absence of any voltage difference, where there is only diffusion and no drift, Eq. 42 reduces to

| (48) |

which for large barriers approaches the limit

| (49) |

In this limit, the flux is given by the Kramers-like formula. It must be noted that is a decreasing function of chain length in the diffusion-limited regime, as in Eq. 13, even when the barrier term brings an additional N-dependent factor.

The effects of barrier height and the chain length on the relation between and Vm are shown in Figs. 4a, 4b. In Fig. 4a, z0=0.04, η=0.002, N=3000, and , and 10. Vm is given in millivolts. As the barrier height increases, the capture rate decreases roughly exponentially for a given voltage difference, as expected from the Arrhenius law. The result for N=3000 is compared to that for N=2000 in Fig. 4b, for α=0.2, z0=0.04, η=0.002, and . As the chain length increases, the flux increases for a fixed voltage difference.

Figure 4.

Effects of (a) barrier height and (b) chain length on the relation between the flux and voltage difference.

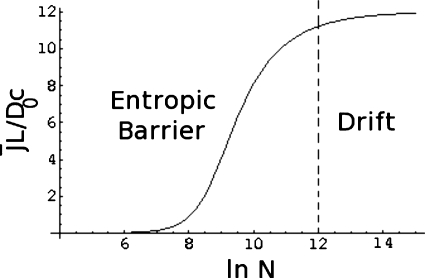

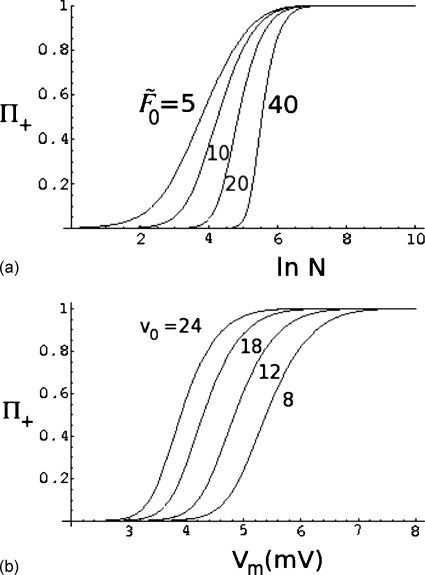

The dependence of on N is illustrated in Fig. 5, where is plotted against ln N for , v0=12, α=0.2, and ν=0.6. The steady state flux increases with chain length until it reaches the asymptotic drift-dominated regime of N-independence for very large values of N, as given by Eq. 47. There is a crossover between the entropic barrier-dominated regime at lower chain lengths and the drift-dominated regime at higher chain lengths, as indicated in Fig. 5. As the chain length increases, the barrier becomes progressively weaker as given by Eq. 24, and the drift term dominates at higher chain lengths. The details of the crossover depend on the barrier height and the strength of the voltage difference. These effects are given in Figs. 6a, 6b. In Fig. 6a, is plotted against ln N for , 20, and 40, v0=12, α=0.2, and ν=0.6. If the barrier due to the intrinsic nature of the pore is higher (that is, is higher), the flux is lower. Also, it takes longer chains to have a reduced effective barrier so that the molecules can undergo translocation. This is seen in the upward shift in N for the apparent threshold for the polymer flux.

Figure 5.

Chain length dependence of the reduced polymer flux.

Figure 6.

Effects of (a) barrier height and (b) voltage difference on the relation between the flux and chain length.

The analogous result for the dependence of the relation between the flux and chain length on the electric potential difference [Vm=v0∕z0, Eq. 44] is given in Fig. 6b for v0=8, 12, 18, and 24, , α=0.2, and ν=0.6. As expected, for each value of N, higher is the electric potential difference, higher is the flux.

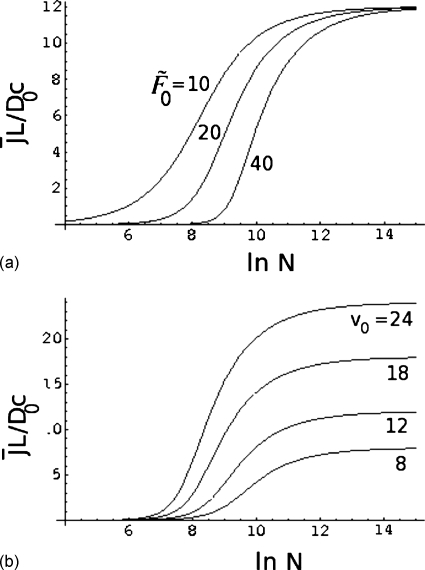

Probability of successful translocation

Substitution of Eqs. 39, 40 into Eqs. 34, 35 gives the expression for the probability of successful translocation in terms of the barrier height,

| (50) |

In writing this expression, we have taken the initial position of the molecule before crossing the barrier height.

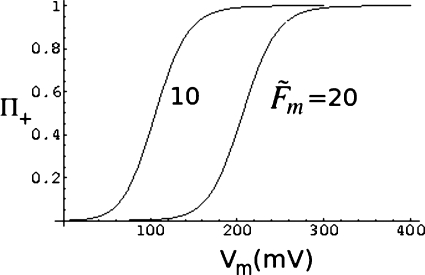

A typical result from the above equation is given in Fig. 7, where Π+(x0) is plotted against Vm (in millivolts) for x0=0.01L, η=0.02, and and 20. In writing Vm in millivolts, we have taken z0 in Eq. 48 as 0.04 mV−1, and N=3000 with ν=0.6. As is evident from this figure, higher is the barrier, lower is the success rate for a fixed voltage gradient. This expected result is given a quantitative form inEq. 50. Analogous to the above results for the capture rate, the dependence of the success rate on the chain length can be calculated from Eq. 50. The dependence of Π+ on ln N is given in Fig. 8a for different values of the barrier height , 10, 20, and 40. The other values of the parameters are v0=12, α=0.2, ν=0.6, η=0.05, and x0=0.01L. As seen from this figure, the probability of success is lower for a given chain length if the barrier is higher. Also, the dependence of the success rate on chain length becomes sharper as the barrier increases. The dependence of Π+ on chain length at different values of voltage difference (v0=8, 12, 18, and 24) is given in Fig. 8b. Here v0=z0Vm and we have chosen z0 as 0.04 mV−1, and , η=0.05, x0=0.01L, α=0.2, and ν=0.6. Again, Eq. 50 provides physically expected result of the success rate of translocation being reduced at lower voltage bias for a fixed chain length.

Figure 7.

Dependence of the probability of successful translocation on voltage difference.

Figure 8.

Effects of (a) barrier height and (b) voltage difference on the relation between the probability of successful translocation and chain length.

CONCLUSIONS

The main results are the closed form equations for the steady state capture rate and the probability of successful translocation, given by Eqs. 42, 50, in terms of the height and location of the barrier, and the voltage difference driving the translocation process. These expressions are general and capture all expected and experimentally observed trends. In general, there are two regimes: (a) entropic barrier regime for low voltage differences and lower chain lengths and (b) drift regime at higher voltage differences and longer chain lengths. The crossover point between these two regimes depends on the barrier height and chain length itself.

The formalism presented here is general for any translocation process. The illustrated results are specific to polyelectrolytes. In particular, the dependence of the electrophoretic mobility only on the salt concentration and not on the chain length is used in the derivation. Furthermore, in the present theory, we have treated the loss in entropy associated with the search of one chain end for the pore mouth as the major contribution to the chain length dependence of the capture rate. This is to be contrasted with other explanations15 in literature. In Ref. 15, the theoretical arguments ignore the entropic barrier for placement of the chain end at the pore mouth and the capture radius is assumed to be orders of magnitude larger than the polymer dimensions, apparently arising from only electrostatic forces and polymer diffusion. In the present theory dealing with polyelectrolytes and an externally applied voltage difference, the polymer flux is never dominated by diffusion and hence the diffusion-limited regime hardly occurs.

In order to elucidate the key aspects of how different regimes arise, we have assumed only a simple free energy profile for the polymer-pore interaction. Instead, more complicated and realistic free energy profiles involving multiple barriers can be taken as the input for Eqs. 28, 35, and the corresponding integrations can then be performed. Also, the results derived here can readily be extended to the presence of electro-osmotic flow and pressure gradients as additional drift contributions. One of the fundamental assumptions in the theory is that the polymer molecule is able to explore all of its conformations in a time scale shorter than the translocation time. It is of considerable interest to assess this assumption based on experiments. Another assumption in the present analysis is that the chain enters only as a tail. A generalization of the present theory allowing for chain entrance as hairpins is of interest.

Finally, the simplicity of the analytical formulas given in Eqs. 42, 50 allows an estimation of the free energy barrier for a particular polymer-pore system. Although the qualitative trends observed experimentally for the polymer flux are captured by these formulas in terms of chain length and applied voltage difference, it would be desirable to test the quantitative accuracy of the predictions for the various experimental systems involving protein pores and solid-state nanopores, in terms of the crossover values of the voltage difference and chain length between the entropic barrier and drift regimes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Acknowledgment is made to NIH (Grant No. R01HG002776) and NSF (Grant No. DMR0706454) for support of this work.

References

- Kasianowicz J. J., Brandin E., Branton D., and Deamer D. W., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 13770 (1996). 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akeson M., Branton D., Kasianowicz J. J., Brandin E., and Deamer D. W., Biophys. J. 77, 3227 (1999). 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77153-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrickson S. E., Misakian M., Robertson B., and Kasianowicz J. J., Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 3057 (2000). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.3057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meller A., Nivon L., Brandin E., Golovchenko J., and Branton D., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 1079 (2000). 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meller A., Nivon L., and Branton D., Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 3435 (2001). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howorka S., Cheley S., and Bayley H., Nat. Biotechnol. 19, 636 (2001). 10.1038/90236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambjörnsson T., Apell S. P., Konkoli Z., DiMarzio E. A., and Kasianowicz J. J., J. Chem. Phys. 117, 4063 (2002). 10.1063/1.1486208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakane J., Akeson M., and Marziali A., Electrophoresis 23, 2592 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meller A. and Branton D., Electrophoresis 23, 2583 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu L. Q., Cheley S., and Bayley H., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 15498 (2003). 10.1073/pnas.2531778100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. L., Gershow M., Stein D., Brandin E., and Golovchenko J. A., Nature Mater. 2, 611 (2003). 10.1038/nmat965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P., Gu J., Brandin E., Kim Y. -R., Wang Q., and Branton D., Nano Lett. 4, 2293 (2004). 10.1021/nl048654j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storm A. J., Chen J. H., Zandbergen H. W., and Dekker C., Phys. Rev. E 71, 051903 (2005). 10.1103/PhysRevE.71.051903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siwy Z. S., Adv. Funct. Mater. 16, 735 (2006). 10.1002/adfm.200500471 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wanunu M., Morrison W., Rabin Y., Grosberg A. Y., and Meller A., Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 160 (2010). 10.1038/nnano.2009.379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthukumar M., Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 36, 435 (2007). 10.1146/annurev.biophys.36.040306.132622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung W. and Park P. J., Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 783 (1996). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzio E. A. and Mandell A. J., J. Chem. Phys. 107, 5510 (1997). 10.1063/1.474256 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthukumar M., J. Chem. Phys. 111, 10371 (1999). 10.1063/1.480386 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lubensky D. K. and Nelson D. R., Biophys. J. 77, 1824 (1999). 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77027-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthukumar M., J. Chem. Phys. 118, 5174 (2003). 10.1063/1.1553753 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong C. Y. and Muthukumar M., J. Chem. Phys. 120, 3460 (2004). 10.1063/1.1642588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong C. Y. and Muthukumar M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 18253 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthukumar M. and Kong C. Y., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 5273 (2006). 10.1073/pnas.0510725103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C. T. A. and Muthukumar M., J. Chem. Phys. 126, 164903 (2007). 10.1063/1.2723088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou T., J. Chem. Phys. 131, 034703 (2009). 10.1063/1.3170952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dorp S., Keyser U. F., Dekker N. H., Dekker C., and Lemay S. G., Nat. Phys. 5, 347 (2009). 10.1038/nphys1230 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forster S. and Schmidt M., Adv. Polym. Sci. 120, 51 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Stellwagen E., Lu Y., and Stellwagen C. C., Biochemistry 42, 11745 (2003). 10.1021/bi035203p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthukumar M., J. Chem. Phys. 107, 2619 (1997). 10.1063/1.474573 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berg H. C., Random Walks in Biology (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1993). [Google Scholar]

- Probstein R. F., Physicochemical Hydrodynamics (Wiley, New York, 1994). 10.1002/0471725137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier M. G. and Slater G. W., Phys. Rev. E 70, 015103(R) (2004). 10.1103/PhysRevE.70.015103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long D., Viovy J. -L., and Ajdari A., Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 3858 (1996). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.76.3858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthukumar M., Electrophoresis 17, 1167 (1996). 10.1002/elps.1150170629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Gennes P. G., Scaling Concepts in Polymer Physics (Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 1979). [Google Scholar]

- Casassa E. F., J. Polym. Sci., Part B: Polym. Lett. 5, 773 (1967). 10.1002/pol.1967.110050907 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaue T. and Raphael E., Macromolecules 39, 2621 (2006). 10.1021/ma0514424 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R. and Muthukumar M., J. Chem. Phys. 131, 194903 (2009). 10.1063/1.3264632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B., Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes (Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner C. W., Handbook of Stochastic Methods (Springer, Berlin, 1985). [Google Scholar]

- Risken H., The Fokker-Planck Equation (Springer, Berlin, 1989). [Google Scholar]

- Redner S., A Guide to First-Passage Processes (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001). 10.1017/CBO9780511606014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berezhkovskii A. M., Pustovoit M. A., and Bezrukov S. M., J. Chem. Phys. 116, 9952 (2002). 10.1063/1.1475758 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berezhkovskii A. M. and Gopich I. V., Biophys. J. 84, 787 (2003). 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74898-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammenti A., Cecconi F., Marconi U. M. B., and Vulpiani A., J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 10348 (2009). 10.1021/jp900947f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]