Abstract

A mononuclear CuII complex acts as an efficient catalyst for four-electron reduction of O2 to H2O by a ferrocene derivative via formation of the dinuclear CuII peroxo complex that is further reduced in the presence of protons by a ferrocene derivative to regenerate the CuII complex.

Cytochrome c oxidases (CcOs), with a bimetallic active-site consisting of a heme a and Cu (Fea3/CuB), are the terminal enzymes of respiratory chains, catalyzing the reduction of molecular oxygen to water by the soluble electron carrier, cytochrome c.1,2 Synthetic Fea3/CuB analogs have attracted significant attention, because the four-electron reduction of O2 is not only of great biological interest,3,4 but also of technological significance such as in fuel cells.5,6 Multicopper oxidases such as laccase also activate oxygen at a site containing a three-plus-one arrangement of 4 Cu atoms, exhibiting remarkable electroactivity for the four-electron reduction of oxygen at potentials approaching 1.2 V (vs RHE).7 Such electrocatalytic reduction of O2 has frequently been used to probe the catalytic reactivity of synthetic CcO model complexes3–5 and some copper (only) complexes have also been investigated.8–10 However, there has been no report on the copper complex catalyzed four-electron reduction of O2 employing one-electron reductants in homogeneous solution; such situations are amenable to systematic studies which provide considerable mechanistic insights.11

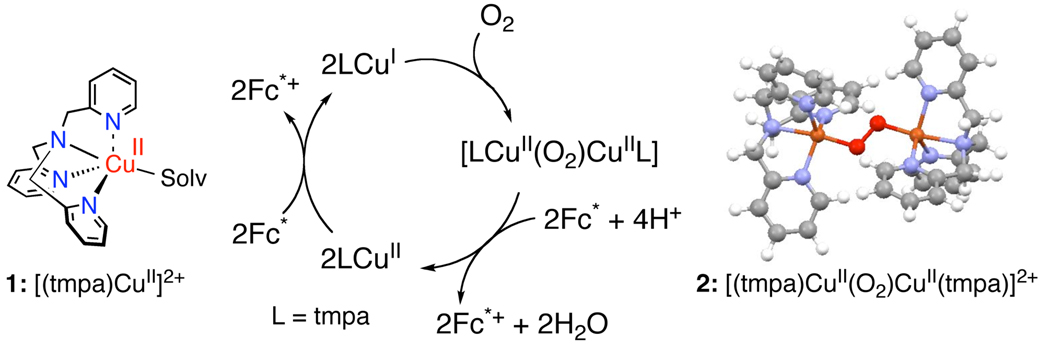

We report herein that a copper complex [(tmpa)CuII](ClO4)2 (1: tmpa = tris(2-pyridylmethyl)amine)12 efficiently catalyzes the four-electron reduction of O2 by one-electron reductants such as ferrocene derivatives in the presence of HClO4 in acetone. As described below, the catalytic mechanism is clarified based on kinetic studies and detection of reactive intermediates.

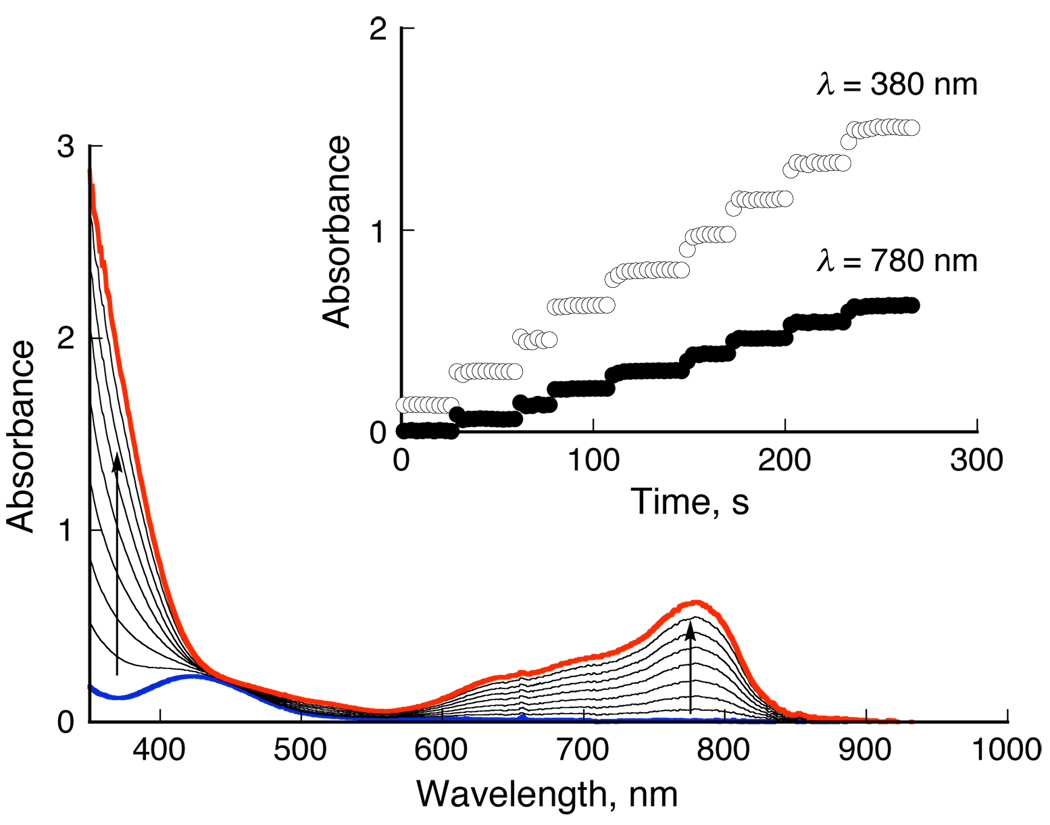

The addition of a catalytic amount of 1 to an O2-saturated acetone solution of decamethylferrocene (Fc*) and HClO4 results in the efficient oxidation of Fc* by O2 to afford ferrocenium cation (Fc*+) (see Supporting Information for the experimental section). Figure 1 shows the spectral changes obtained following stepwise addition of HClO4 to this solution. For each time period, the concentration of Fc*+ (λmax = 380 and 780 nm)11 immediately formed is the same as the concentration of HClO4 added. The reduced product of O2 is confirmed to be H2O based on the detection of H2 18O by 18O-labeled O2 experiments (Figure S1). It has also been confirmed that no H2O2 is detected via iodometric titration experiments (Figure S2).13 When more than four equiv. of Fc* relative to O2 (i.e., limiting [O2]) were employed, only four equiv. Fc*+ were formed in the presence of four equiv. HClO4 (Figure S3).14 Thus, the stoichiometry of the catalytic reduction of O2 by Fc* is given by eq 1.15

| (1) |

Figure 1.

UV-vis spectral change in four-electron reduction of O2 by Fc* (1.5 mM) with 1 (9.0 × 10−5 M) in the presence of HClO4 in acetone at 298 K. Inset shows the change in absorbance at 380 and 780 nm due to Fc*+ by stepwise addition of HClO4 (0.18 – 1.44 mM) to an O2-saturated acetone solution ([O2] = 11 mM) of Fc* and 1.

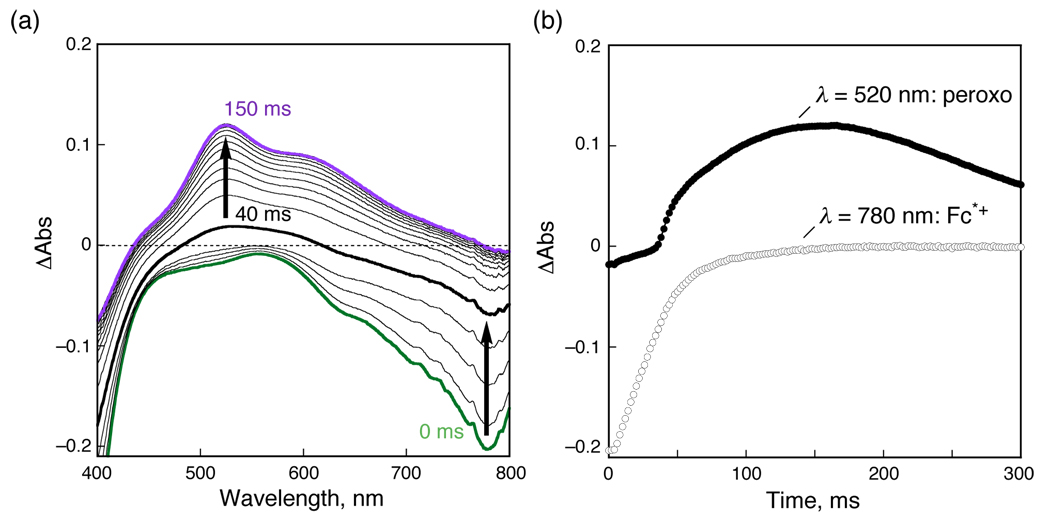

The time profile of the four-electron reduction of O2 with Fc* catalyzed by 1 in the presence of HClO4 in acetone at 298 K was examined by stopped-flow measurements. Figure 2a shows the observed absorption spectral change during the catalytic reaction. Under the conditions employed with relative concentrations of reagents as given in the Figure 2 caption, it is only after Fc*+ (λmax = 780 nm) is completely formed that the peroxo species, [(tmpa)CuII(O2)CuII(tmpa)]2+ (2: λmax = 520 nm)16 starts to be produced.17 This is more clearly seen in Figure 2b, the time profiles for the absorbance at 780 nm due to Fc*+, by comparison to the absorbance at 520 nm due to 2. Because the concentration of HClO4 is smaller than that of Fc*, HClO4 has been consumed when the reaction is over. It is well established that [(tmpa)CuI]+ reacts with O2 affording the superoxo species [(tmpa)CuII(O2 −)]+ which reacts rapidly with [(tmpa)CuI]+ to produce the peroxo species 2.16 Thus, electron-transfer reduction of 1 by Fc* with O2 but without HClO4 affords 2. This is the reason why 2 starts to appear only after HClO4 is all consumed. The stoichiometry of the reaction of Fc* with 1 and O2 is given by eq 2.

| (2) |

Figure 2.

(a) Formation of the peroxo species 2 (λmax = 520 nm) in electron transfer from Fc* (1.0 mM) to 1 (0.12 mM) in the presence of HClO4 (0.35 mM) in aerated acetone at 298 K. (b) Time profile of the absorbance at 520 nm (●) and 780 nm (○) due to 2 and Fc*+, respectively.

The rate of formation of Fc*+ in Figure 2b appears to be constant with respect to the concentration of Fc*+, when the concentration of Fc* is in large excess compared to that of HClO4. The constant rate (M s−1) increases linearly with increasing concentration of 1 and Fc* (Figure S5). The second-order rate constant (kobs) is determined to be (1.1 ± 0.1) × 105 M−1 s−1 from the slope of Figure S5, which is divided by the initial concentration of Fc* (1.0 mM).

The rate of formation of Fc*+, accompanied by formation of 2 via electron transfer from Fc* to 1 with O2, was also determined without HClO4, obeying pseudo-first-order kinetics, when the concentration of Fc* is much larger than that of 1 (Figure S6). This rate constant increases linearly with concentration of Fc*. From the slope of the linear plot, the second-order rate constant (k'obs) for formation of Fc*+ without HClO4 under single turnover conditions is determined to be (4.9 ± 0.4) × 104 M−1 s−1 (Figure S6). This value is one-half as compared to the rate constant under catalytic conditions with HClO4. This is quite consistent with the stoichiometries of the catalytic reaction (eq 1) and the single turnover reaction (eq 2), because an additional equiv. of Fc*+ is formed in the presence of HClO4 under the catalytic conditions following formation of one equiv. of Fc*+ under the single turnover reaction (see Supporting Information for the kinetic analysis).

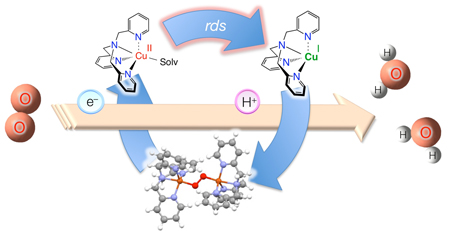

No further reduction of the peroxo species 2 occurs without an acid. However, the addition of HClO4 facilitates electron-transfer and the further two-electron reduction of 2 to produce two equiv. of Fc*+, accompanied by regeneration of 1. This was confirmed by low temperature measurements (Figure S7). Thus, the overall catalytic cycle is given in Scheme 1. The initial electron transfer from Fc* to 1 and reaction with O2 affords the two-electron reduction of oxygen to produce the peroxo species that can be further reduced in the presence of HClO4 to facilitate the four-electron reduction of O2 to H2O by Fc* (Scheme 1).18

Scheme 1.

In summary, a copper complex 1 acts as an effective catalyst for the four-electron reduction of O2 by one-electron reductants such as Fc* in the presence of an acid. The present study opens a new approach and the use of copper ion to develop efficient catalysts for the four-electron reduction of O2, because the catalytic activity and stability of intermediates can certainly be controlled and tuned by variation of ligands for copper ion.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid (No. 20108010) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan (S.F.), the National Institutes of Health (USA) (K.D.K., GM28962), and KOSEF/MEST through WCU project (R31-2008-000-10010-0) (S.F & K.D.K.)

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Experimental section, kinetic analysis, and figures (Figure S1–S7). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Ferguson-Miller S, Babcock GT. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2889. doi: 10.1021/cr950051s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pereira MM, Santana M, Teixeira M. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1505:185. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(01)00169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Tsukihara T, Aoyama H, Yamashita E, Tomizaki T, Yamaguchi H, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Nakashima R, Yaono R, Yoshikawa S. Science. 1995;269:1069. doi: 10.1126/science.7652554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yoshikawa S, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Nakashima R, Yaono R, Yamashita E, Inoue N, Yao M, Fei MJ, Libeu CP, Mizushima T, Yamaguchi H, Tomizaki T, Tsukihara T. Science. 1998;280:1723. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5370.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Kim E, Chufán EE, Kamaraj K, Karlin KD. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:1077. doi: 10.1021/cr0206162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chufán EE, Puiu SC, Karlin KD. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:563. doi: 10.1021/ar700031t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Collman JP, Boulatov R, Sunderland CJ, Fu L. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:561. doi: 10.1021/cr0206059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Collman JP, Boulatov R, Sunderland CJ. In: The Porphyrin Handbook. Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R, editors. Vol. 11. USA: Elsevier Science; 2003. pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Cracknell JA, Vincent KA, Armstrong FA. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:2439. doi: 10.1021/cr0680639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Willner I, Yan Y-M, Willner B, Tel-Vered R. Fuel Cells. 2009;9:7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Anson FC, Shi C, Steiger B. Acc. Chem. Res. 1997;30:437. [Google Scholar]; (b) Shin H, Lee D-H, Kang C, Karlin KD. Electrochim. Acta. 2003;48:4077. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Blanford CF, Heath RS, Armstrong FA. Chem. Commun. 2007:1710. doi: 10.1039/b703114a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mano N, Soukharev V, Heller A. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:11180. doi: 10.1021/jp055654e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Zhang J, Anson FC. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1993;348:81. [Google Scholar]; (b) Watanabe H, Yamazaki H, Wang X, Uchiyama S. Electrochim. Acta. 2009;54:1362. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thorum MS, Yadav J, Grewirth AA. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:165. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weng YC, Fan F-RF, Bard AJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:17576. doi: 10.1021/ja054812c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.For the catalytic reduction of O2 by chemical reductants with cobalt porphyrins and cobalt corroles, see: Fukuzumi S, Okamoto K, Gros CP, Guilard R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:10441. doi: 10.1021/ja048403c. Kadish KM, Frémond L, Shen J, Chen P, Ohkubo K, Fukuzumi S, Ojaimi ME, Gros CP, Barbe J-M, Guilard R. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:2571. doi: 10.1021/ic802092n.

- 12.Karlin KD, Kaderli S, Zuberbühler AD. Acc. Chem. Res. 1997;30:139. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Mair RD, Graupner AJ. Anal. Chem. 1964;36:194. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fukuzumi S, Kuroda S, Tanaka T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;107:3020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.The O2 concentration in an O2-saturated acetone solution (11 mM) was determined by the spectroscopic titration for the photooxidation of 10-methyl-9,10-dihydroacridine by O2; see Fukuzumi S, Imahori H, Yamada H, El-Khouly ME, Fujitsuka M, Ito O, Guldi DM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:2571. doi: 10.1021/ja002052u. Fukuzumi S, Ishikawa M, Tanaka T. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2. 1989:1037.

- 15.The turnover number (TON = 7) based on 1 was determined under the catalytic conditions as shown in Figure S3.

- 16.(a) Zhang CX, Kaderli S, Costas M, Kim E-i, Neuhold Y-M, Karlin KD, Zuberbuhler AD. Inorg. Chem. 2003;42:1807. doi: 10.1021/ic0205684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fry HC, Scaltrito DV, Karlin KD, Meyer GJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:11866. doi: 10.1021/ja034911v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Note that the spectra recorded were taken as difference spectra in which the final spectrum was subtracted; recovery of bleaching absorption at 780 nm corresponds to the formation of Fc*+ (see SI Figure S4)

- 18.The value of turnover frequency (TOF = 17 s−1) was obtained in the catalytic four-electron reduction of O2 by Fc* (1.0 mM) with 1 (5.0 × 10−6 M) in the presence of HClO4 (0.1 mM) in acetone at 298 K at 300 ms (TON = 5) as shown in Figure S5b.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.