Abstract

CD14 contributes to LPS signaling in leukocytes through formation of toll-like receptor 4/CD14 receptor complexes; however, a specific role for endogenous cell-surface CD14 in endothelial cells is unclear. We have found that suppression of glutathione peroxidase-1 (GPx-1) in human microvascular endothelial cells increases CD14 gene expression compared to untreated or siControl (siCtrl)-treated conditions. Following LPS treatment, GPx-1 deficiency augmented LPS-induced intracellular reactive oxygen species accumulation, CD14 expression, and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) mRNA and protein expression compared to LPS-treated control cells. GPx-1 deficiency also transiently augmented LPS-induced vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) expression. Adenoviral overexpression of GPx-1 significantly diminished LPS-mediated responses in adhesion molecule expression. Consistent with these findings, LPS responses were also greater in endothelial cells derived from GPx-1-knockout mice, whereas adhesion molecule expression was decreased in cells from GPx-1-overexpressing transgenic mice. Knockdown of CD14 attenuated LPS-mediated up-regulation of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 mRNA and protein, and it mitigated the effects of GPx-1 deficiency on LPS-induced adhesion molecule expression. Taken together, these data suggest that GPx-1 modulates the endothelial cell response to LPS, in part, by altering CD14-mediated effects.—Lubos, E., Mahoney, C. E., Leopold, J. A., Zhang, Y.-Y., Loscalzo, J., Handy, D. E. Glutathione peroxidase-1 modulates lipopolysaccharide-induced adhesion molecule expression in endothelial cells by altering CD14 expression.

Keywords: innate immunity, inflammation, ICAM-1, ROS

Increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the vasculature increase oxidant stress and contribute to vascular pathobiology (1). The vascular endothelium expresses antioxidant enzymes, such as the selenocysteine-containing glutathione peroxidases (GPx), which protect against oxidative stress (2,3,4). GPx-1 is one of the most abundant glutathione peroxidase isoforms in eukaryotic cells. Previous studies have associated a lack of GPx-1 with endothelial dysfunction, cellular apoptosis, and increased susceptibility to atherosclerosis (5,6,7,8,9); however, the molecular mechanisms by which GPx-1 deficiency promotes vascular injury are unclear. To elucidate the mechanisms by which GPx-1 modulates cellular responses, we first performed microarray analysis and found that CD14 was among the targets up-regulated in GPx-1-deficient cells compared to control cells.

CD14 is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked 55-kDa, myeloid-specific, leucine-rich repeat (LRR) glycoprotein (10) that is highly expressed on the surface of monocytes and other myeloid cells (11, 12). A role for endogenously expressed CD14 in endothelial cells is unclear, as CD14 is not highly expressed in these cells (13). Isoforms of CD14 are formed via posttranslational modification, resulting in a membrane-bound GPI-anchored glycoprotein (mCD14) or a soluble proteolytic fragment lacking the GPI anchor (sCD14) (14). Both GPI-linked mCD14 and sCD14 isoforms may contribute to LPS signaling via effects on Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4)-myeloid differentiation protein 2 (MD-2) receptor complexes (15,16,17). In endothelial cells, sCD14 is thought to play a major role in LPS-mediated responses (18, 19); however, recent studies suggest mCD14, expressed on the endothelial cell surface, may also play a role in LPS-mediated signaling (20). In vivo, CD14 appears to be necessary for LPS responses, as CD14-knockout mice are LPS insensitive and resistant to septic shock (21, 22), whereas transgenic mice expressing human CD14 are hypersensitive to LPS stimulation (23).

The interaction of LPS with CD14 on the surface of endothelial cells results in endothelial activation, as demonstrated by the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules (24, 25), and, in some cases, endothelial apoptosis (26). In this study, we demonstrate that GPx-1 deficiency increases CD14 expression and potentiates endothelial responses to LPS, leading to increased expression of adhesion molecules and the accompanying inflammatory phenotype in endothelial cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Small interfering RNA transfection and recombinant adenoviral vector infection

Human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVECs), human coronary endothelial cells (HCAECs), and EGM-2MV medium were obtained from Lonza (Allendale, NJ, USA). Cells were propagated according to the supplier’s recommendations. Cell culture dishes (100-mm or 6-well plates) of confluent HMVECs were transfected for 3 h with a solution of OptiMEM I (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing stealth siRNA (Invitrogen) and Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). To knock down GPx-1 expression, the sequence GGUUCGAGCCCAACUUCAUGCUCUU was used along with a control sequence, GGUAGCGCCAAUCCUUACGUCUCUU (27). To knock down CD14, HMVECs were transfected with the sequence CGGUCUCAACCUAGAGCCGUUUCUA. One day after transfection, HMVECs were incubated with medium containing 10–1000 ng/ml LPS for 3–24 h, and further studies were initiated. A recombinant adenovirus vector expressing GPx-1 tagged with a c-Myc epitope at the amino terminus (AdGPx-1) (28) was kindly provided by John F. Engelhardt through the Gene Transfer Vector Core (University of Iowa, Ames, IA, USA). Confluent HMVECs were incubated with AdGPx-1 or an empty adenoviral vector (Ad5Bgl II) for 1 d and then treated with LPS (1000 ng/ml) for 24 h.

Cellular glutathione peroxidase activity assay

An indirect assay was used to detect GPx activity (mU/mg) as measured by NADPH oxidation (29).

Western blot analysis

Cells were washed in PBS (1%), scraped in PBS, and pelleted at 300 g for 5 min. Cell pellets were resuspended in ice-cold buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 5 mM EDTA; and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)], and lysed by the freeze-thaw method. Alternatively, cells were directly lysed in cell lysis buffer with protease inhibitors. Protein samples (10–40 μg) were separated on 4–15% SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond; Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The membranes were incubated with anti-GPx-1 antibody (MBL, Woburn, MA, USA), anti-intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) or anti-vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) overnight at 4°C, and visualized using the ECL detection system (GE Healthsciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The membranes were then stripped and reprobed with a polyclonal rabbit anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). A VersaDoc scanning system and the accompanying software (Bio-Rad) were used to quantitate band density.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

Total RNA from HMVECs was extracted with the RNeasy kit (Qiagen Sciences, Germantown, MD, USA), incorporating an optional DNase I step to remove residual DNA. cDNA was synthesized from 0.4–1 μg of each total RNA sample with oligo(dT) primers using the Advantage RT-for-PCR Kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative real-time PCR, including data analysis, was performed on the Applied Biosystems PRISM 7900 HT Sequence Detector containing specific primers (Table 1). PCR products were analyzed by a method that compared the amount of target gene to an endogenous control (GAPDH). Cycle parameters were 95°C for 15 min to activate Taq, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 58°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min.

TABLE 1.

Genes analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR

| Gene | Applied Biosystems assay | Reference sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Human | ||

| GAPDH | 4333764T | NM_002046.3 |

| GPx-1 | Hs00829989_gH | NM_201397.1, NM_000581.2 |

| ICAM-1 | Hs00164932_m1 | NM_000201.1 |

| VCAM-1 | Hs00365485_m1 | NM_080682.1, NM_001078.2 |

| CD14 | Hs02621496_s1 | NM_001040021.1, NM_000591.2 |

| MD-2 (LY96) | Hs00209770_m1 | NM_015364.2 |

| MyD88 | Hs00182082_m1 | NM_002468.4 |

| TLR-4 | Hs00152939_m1 | NM_138554.3 |

| Mouse | ||

| GAPDH | Mm99999915_g1 | NM_008084.2 |

| GPx-1 | Mm00656767_g1 | NM_008160.5 |

Dichlorodihydrofluorescein fluorescence

HMVECs were plated on 96-well plates and incubated with 5-(and 6-)-carboxy-2′-7′ dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate ester (DCF) (5 μM) for 1 h, and intracellular ROS accumulation was measured using a microplate fluorometer (30).

Endothelial cell isolation from mouse lung

Homozygous GPx-1-knockout (GPx-1 KO), homozygous transgenic overexpressing GPx-1 (tgGPx-1), and wild-type (WT) mice (C57/BL6) have been previously described (31). Briefly, 6 male 6- to 8-wk-old mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of a mixture of xylazine (5 mg/kg) and ketamine (100 mg/kg). Lungs were removed under sterile conditions, and pulmonary endothelial cells were isolated by collagenase digestion and Dynabead selection (Dynal Biotech, Carlsbad, CA, USA) using rat-anti-mouse CD31 (PECAM-1) antibody and rat-anti-mouse CD102 (ICAM-2) antibody (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), as described previously (32). Cells were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen) with high glucose, supplemented with 20% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, 100 μg/ml heparin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 100 μg/ml endothelial cell growth supplement (ECGS; Biomedical Technologies, Stoughton, MA, USA), 1× nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen), 2 mM l-glutamine, and 110 mg/L sodium pyruvate on fibronectin-coated flasks. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Harvard Medical School.

RESULTS

CD14 is synthesized and expressed in endothelial cells

To determine the pathways by which GPx-1 modulates cellular responses to ROS, we performed microarray analysis in HMVECs treated with 20 ng/ml TNF-α for 2 h following GPx-1 knockdown (siGPx-1) or control (siControl) transfection. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) identified >430 genes up- or down-regulated by >2-fold by TNF-α treatment. Among these changes, CD14 mRNA was 6.8-fold higher in TNF-α-treated siGPx-1 compared to siControl cells (data not shown). To analyze further the effects of GPx-1 deficiency on CD14 expression, we used qRT-PCR. We found that knockdown of GPx-1 in the absence of cytokine stimulation increased CD14 expression ∼7-fold after 48 h transfection compared to untreated cells (P<0.0001) an increase that was 2.9-fold higher than in siControl-treated cells (P<0.0001) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

CD14 gene expression in endothelial cells. HMVECs were transfected with siGPx-1 or siRNA control (siCtrl) for 48 h, and CD14 mRNA was measured by qRT-PCR (n=4). Data are presented as means ± se. Means were significantly different by ANOVA (P<0.0001). *P < 0.0001, #P < 0.03 vs. other groups; post hoc analysis using Fisher’s protected least-square difference (PLSD). UT, untransfected.

Treatment of macrovascular HCAECs with siGPx-1 caused a similar trend in increasing CD14 mRNA (data not shown). These findings indicate that GPx-1 deficiency is sufficient to increase CD14 expression in microvascular and macrovascular endothelial cells, suggesting that ROS play a role in the up-regulation of this immunomodulatory protein in endothelial cells.

LPS induces increased ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression in HMVECs

CD14 contributes to LPS signaling through formation of TLR-4-CD14 receptor complexes. In endothelial cells, the TLR-4-dependent LPS pathways induce adhesion molecule mRNA expression (33). In HMVECs, we observed that ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 mRNA levels were increased markedly 3 h after LPS stimulation (P<0.0001 and P<0.0001, respectively). Protein levels were significantly increased after 12 h (P<0.0001 and P<0.0001, respectively), with maximum levels following 18 h LPS (Fig. 2A, B). These changes were detectable with as little as 10 ng/ml LPS, and persisted at concentrations up to 10 μg/ml (Fig. 2C). On average, GPx-1 protein levels were not altered by LPS treatment, although GPx-1 mRNA levels increased up to 4.5-fold following-treatment (data not shown). LPS treatment increased CD14 mRNA expression 1.8-fold compared to untreated cells (P=0.0009) (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

LPS and ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression. A) HMVECs were incubated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 3–24 h, and ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 transcripts were measured by qRT-PCR (n=3). B, C) Proteins were separated on 4–15% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to HyBond membrane. Antibodies against GPx-1 (MBL), ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 (Santa Cruz), and actin (Sigma) were used to detect the effect of LPS in a time-dependent (n=4) (B), and dose-dependent (n=2) fashion (C). Representative blots are shown. D) After LPS treatment for 3–24 h, CD14 mRNA was measured by qRT-PCR (n=3). Data are presented as means ± se. *P < 0.0001, #P < 0.001 vs. no treatment; Fisher’s PLSD pairwise comparison.

GPx-1 deficiency increases ROS accumulation and augments LPS-induced ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression

LPS signaling is thought to rely in part on ROS generation (34). To test whether GPx-1-deficient HMVECs display an inability to remove oxidants, GPx-1-deficient and control cells were treated with 1000 ng/ml LPS, and DCF fluorescence was used as a nonspecific indicator of intracellular ROS accumulation. GPx-1 deficiency significantly increased LPS-induced intracellular ROS accumulation compared to LPS-treated control cells after 30 min (170.5±36.5 vs. 113.9±17.1%, P=0.03, Fig. 3A). Following 24 h of treatment with 1000 ng/ml LPS, CD14 mRNA was significantly up-regulated in GPx-1-deficient cells compared to LPS-treated siControl cells (P<0.0001) (Fig. 3B). In addition, GPx-1 knockdown plus 24 h LPS further augmented ICAM-1 mRNA (3.2-fold, P<0.0001) and protein (1.8-fold, P=0.006) expression compared to LPS-treated siControl cells (Fig. 3C, D), whereas VCAM-1 expression was similarly enhanced in LPS-treated siGPx-1 and siControl cells at 24 h (Fig. 3C, D). In the absence of LPS, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 mRNA (4.5-fold and 2.4-fold, respectively) and protein (3.0-fold and 2.9-fold, respectively) were increased by siGPx-1 alone. To further characterize the effects of GPx-1 on LPS stimulation, we performed dose-response (10–1000 ng/ml) and time course studies in the presence and absence of GPx-1. Strikingly, GPx-1 deficiency increased ICAM-1 protein at each dose of LPS (Fig. 3E). As shown in Fig. 3F, LPS-induced expression of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 was apparent 6 h following LPS treatment, in each of the doses of LPS tested (1000 or 100 ng/ml) and, at this early time point, GPx-1 deficiency enhanced LPS-mediated VCAM-1 expression; at the later time points, the difference between VCAM-1 expression in GPx-1-deficient and control cells was greatly reduced. In contrast, GPx-1 deficiency enhanced ICAM-1 expression throughout each time course. Overall, these data suggest that GPx-1 deficiency augments LPS-mediated responses, possibly by increasing oxidative stress.

Figure 3.

Knockdown of GPx-1 and LPS-induced ROS accumulation and adhesion molecule expression. A) ROS accumulation was measured by DCF fluorescence 30 min after 1 μg/ml LPS treatment (n=3). ANOVA, P < 0.0001. *P < 0.05; pairwise comparison. B, C) HMVECs were transfected with siGPx-1 or siRNA control (siCtrl) for 24 h and treated with 1 μg/ml LPS for 24 h. CD14 (B) and ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 (C) mRNA was measured by qRT-PCR (n=4). ANOVA, P < 0.05. *P < 0.05; post hoc pairwise analysis. D) Effect of 1 μg/ml LPS on GPx-1, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1 protein expression in GPx-1-deficient cells compared to siControl cells was determined by immunoblotting after 24 h of treatment. Densitometry was performed on 5 blots. Data are presented as means ± se; ANOVA, P < 0.0001. *P < 0.05; post hoc tests. E) Dose-dependent effects of LPS on ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression were analyzed by Western blot following 24 h of treatment in GPx-1-deficient and control cells (n=3). F) Time course of LPS-stimulated ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression was monitored by Western blot using 1000 and 100 ng/ml LPS (n=2–3). Representative blots are shown.

Overexpression of GPx-1 reduces LPS-induced adhesion molecule expression

To determine whether excess GPx-1 could reduce LPS-mediated endothelial activation, we used adenovirus to overexpress myc-tagged GPx-1. Adenoviral overexpression of GPx-1 increased GPx-1 mRNA 83.8-fold (P=0.002) with an 11.6-fold (P<0.0001) increase in GPx-1 protein compared to control adenovirus-treated cells (Fig. 4A). Overall, adenoviral overexpression of GPx-1 attenuated LPS-mediated responses, including up-regulation of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 mRNA, compared with LPS-treated adenovirus control HMVECs (P<0.05) (Fig. 4B). Compared to empty vector conditions, GPx-1 adenovirus treatment also resulted in lower expression of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 in unstimulated cells. Despite dramatic overexpression of GPx-1, with an increase in GPx-1 activity of 5.5-fold (P<0.0001) compared to empty vector-treated cells, expression of adhesion molecules was only modestly, but significantly, decreased.

Figure 4.

Overexpression of GPx-1 and LPS-induced ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression. HMVECs were infected with AdGPx-1 or empty vector control (Ad5Bgl II) for 24 h, followed by treatment with 1 μg/ml LPS for 24 h. A) GPx-1 transcript levels were measured by qRT-PCR; GPx-1 protein was assessed by Western blotting. B) ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 transcripts were measured by qRT-PCR (n=3). Data are presented as means ± se; ANOVA, P < 0.0001. *P < 0.0001, #P < 0.05; pairwise comparisons.

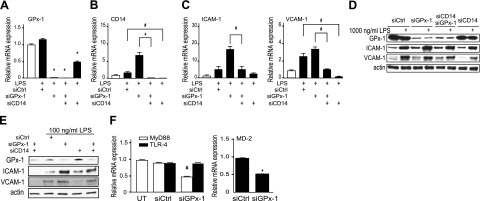

Targeted knockdown of CD14 reduces LPS-induced ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression

To confirm the role of endothelial CD14 in LPS-induced endothelial cell activation, we used siRNA to knock down CD14. siCD14 treatment decreased CD14 mRNA by 99.6% (Fig. 5B) and was accompanied by a subsequent decrease in ICAM-1 mRNA and protein expression following LPS stimulation in GPx-1-deficient cells (Fig. 5C–E). Unexpectedly, in the presence of 1000 ng/ml LPS, siCD14 decreased GPx-1 mRNA; however, there was no effect on GPx-1 protein expression under these conditions. In LPS-stimulated cells, double knockdown of GPx-1 and CD14 decreased ICAM-1 mRNA (P=0.0002) and protein (P=0.01) to a lesser extent than CD14 alone; however, the double knockdown was sufficient to reduce expression to the levels in LPS-treated siControl cells when cells were treated with 1000 or 100 ng/ml LPS (Fig. 5C–E). Similarly, LPS-mediated increases in VCAM-1 mRNA and protein expression were significantly diminished by siCD14 (Fig. 5C, D).

Figure 5.

Knockdown of CD14 and LPS-induced adhesion molecule expression. A–C) GPx-1 (A), CD14 (B), and ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 (C) transcripts were measured by qRT-PCR after transfection with siRNA (siCtrl, siGPx-1, siCD14, siGPx-1/siCD14) for 24 h followed by 1 μg/ml LPS treatment for 24 h (n=4). D, E) Western blots were performed to show the effect of 1000 ng/ml LPS (D) and 100 ng/ml LPS (E) on GPx-1, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1 protein expression in GPx-1-deficient and CD14-deficient cells compared to siControl cells. Representative blots are shown. F) HMVECs were transfected with siGPx-1 or siRNA control (siCtrl) for 48 h, and transcripts for TLR-4, MyD88, and MD-2 were measured by qRT-PCR (n=3). Data are presented as means ± se; ANOVA, P < 0.001. *P < 0.0001, #P < 0.01; Fisher’s PLSD test.

LPS signaling in endothelial cells also involves TLR-4, MD-2 (an accessory protein necessary for LPS recognition and TLR-4 signaling), and the adaptor protein myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88) (15,16,17). GPx-1 deficiency had no effect on expression of TLR-4, but decreased MyD88 and MD-2 mRNA (P=0.0005 and P<0.0001, respectively, Fig. 5F). Lack of MyD88 has been shown to greatly diminish inflammatory responses to LPS (35); however, with GPx-1 deficiency, we have found enhanced LPS-mediated effects, along with increased CD14 expression. Similarly, MD-2 is essential for TLR-4 recognition of LPS. That MyD88 and MD-2 expression decreases with GPx-1 deficiency argues for a partly compensatory mechanism modulating the extent to which GPx-1 deficiency enhances the LPS response. Thus, these data suggest that GPx-1 modulates the cellular response to LPS by altering CD14 expression, rather than by altering TLR-4 and does so despite a decrease in MyD88 and MD-2 expression.

ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 regulation in WT, GPx-1 KO, and tgGPx-1 mice

To confirm the role of GPx-1 in modulating the cellular response to LPS, we isolated pulmonary endothelial cells from GPx-1 KO, tgGPx-1, and WT mice. Compared to WT cells, pulmonary endothelial cells from GPx-1 KO mice had 94% (P<0.0001) less GPx-1 mRNA (Fig. 6A). By immunoblotting, GPx-1 protein was not detectable in GPx-1 KO cells (Fig. 6B). These changes in expression in primary cells derived from lung correlated with changes in GPx-1 activity measured in lung tissue extract from these mice (Fig. 6C). In comparison, endothelial cells from tgGPx-1 mice had a 55.6-fold increase in GPx-1 mRNA with a 9.4-fold increase in GPx-1 protein (P<0.0001) compared to WT cells. In these primary cells, 24 h LPS-treatment caused an up-regulation of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 protein in GPx-1 KO and WT cells, whereas tgGPx-1 cells had a blunted response to LPS, with no increase in ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 following LPS treatment (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Pulmonary endothelial cells and lung tissue from GPx-1 KO and tgGPx-1 mice and LPS-induced ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression. A, B) Pulmonary endothelial cells (passage 4) from WT, GPx-1 KO, and tgGPx-1 mice were incubated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 24 h. GPx-1 mRNA was measured by qRT-PCR (A); GPx-1, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1 protein were measured by immunoblotting (B) (n=3). C) GPx-1 activity was measured in lung tissue from WT, GPx-1 KO, and tgGPx-1 mice. *P < 0.0001 vs. WT, KO vs. tg.

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest that GPx-1 deficiency can increase CD14 expression in resting and stimulated endothelial cells and that increased expression results in enhanced LPS-mediated responses in these cells, including increased accumulation of ROS, and augmented expression of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1. Further, overexpression of GPx-1 mitigated LPS responses in these cells, and CD14 knockdown attenuated LPS-mediated endothelial cell activation, even in the presence of GPx-1 deficiency. Thus, in endothelial cells, GPx-1 modulates the cellular response to LPS by mechanisms that depend, in part, on endothelial expression of CD14.

CD14, a GPI-linked 55-kDa glycoprotein with multiple leucine-rich repeats, is abundantly expressed on monocytes/macrophages and neutrophils and at low levels on other cell types (14, 36,37,38). In endothelial cells, soluble CD14 (sCD14) was believed to play a major role in LPS-mediated activation, as these cells were considered negative for membrane-bound CD14 (mCD14) (18, 19); however, other studies suggest that endothelial cells can synthesize CD14 (13, 20) and indicate that soluble CD14 is unable to substitute fully for endogenously expressed CD14 (39). Thus, our findings further highlight the importance of endogenously expressed CD14 in endothelial cell responses to LPS.

As CD14 does not span the membrane, it is not a typical receptor and alone cannot cause cellular activation; rather, CD14/LPS complexes couple with TLR-4–MD-2 to activate cells (37, 40). On binding LPS and CD14 to TLR-4–MD-2, the cytoplasmic region of TLR-4 recruits MyD88, a signaling adaptor molecule essential for LPS-mediated activation of endothelial cells (41, 42). In GPx-1-deficient human endothelial cells, we found increased expression of CD14, with no change in TLR-4 gene expression and a decrease in MyD88 gene expression. In addition, expression of MD-2, a protein essential for LPS-mediated responses (15,16,17), is also down-regulated by GPx-1 deficiency. Although it is now recognized that TLR-4 may activate cells through MyD88-dependent and -independent pathways (42), loss of MyD88 is associated with diminished responses to LPS (35). The significance of decreased MyD88 expression is unclear, but it may be a mechanism to down-regulate TLR-mediated signaling, whereas previous studies indicate that enhanced expression of CD14 augments TLR-4 effects (23, 43, 44). Similarly, absence of MD-2 prevents TRL-4 responses to LPS (15, 17, 45). However, we found that MD-2 is highly expressed in endothelial cells and increased responses to LPS occur in the setting of its down-regulation, suggesting that its levels are not limiting in endothelial cells with GPx-1 deficiency. Thus, our findings of elevated CD14 expression, combined with the ability of CD14 knockdown to mitigate the effects of GPx-1 deficiency on LPS-signaling, suggest that GPx-1 modulates the LPS-response in endothelial cells, in part, by altering CD14 expression and CD14-dependent signaling. In fact, it has been suggested that up-regulation of CD14 could cause hypersensitivity to LPS (23) by a mechanism known as “priming” or “sensitization.” Thus, GPx-1 deficiency may directly potentiate the effects of LPS by sensitizing cells to LPS, by augmenting the downstream signaling effects of LPS, or both.

LPS treatment, in itself, has been shown to enhance CD14 expression in a number of cell types, including mononuclear cells (46), and LPS-induced up-regulation of CD14 is thought to augment further LPS-induced inflammation and damage. In both transfected and nontransfected cells, we found that LPS increased CD14 expression and that this increase was greater in the context of GPx-1 deficiency. These findings indicate that endothelial cells can be sensitized to LPS by prior LPS exposure, even in the absence of GPx-1 deficiency.

Chronic infection and TLR-4 responses have been postulated to contribute to atherosclerosis (47,48,49); however, in the absence of infectious agents, knockout of CD14 in apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice has no effect on the development of atherosclerosis (50). Knockout of TLR-4 or the adaptor protein Myd88, however, attenuates vascular lesions in diet-induced models of atherogenesis in ApoE−/− mice (50, 51). These findings suggest that TLR-4 may modulate atherogenesis, in some settings, by mechanisms independent of CD14. Nonetheless, CD14 plays an essential role in innate immunity and pathogen-mediated TLR-4 effects. In addition, this accessory molecule has been recently shown to regulate cardiovascular and metabolic complications of obesity by mechanisms not yet fully elucidated (52). Taken together, these findings suggest that alteration in CD14/TLR-4 complex components may substantially modify not only LPS-mediated activation but cardiovascular outcomes and risk. In human and animal models of cardiovascular disease, GPx-1 deficiency has been correlated with an increased risk for cardiovascular events and atherosclerosis (8, 9, 53); however, detailed mechanisms by which GPx-1 deficiency may affect endothelial function are not completely understood. The data presented here suggest that GPx-1 deficiency may contribute to atherogenesis, in part, by promoting endothelial adhesion molecule expression in response to CD14/TLR-4 activation.

Taken together, our data suggest a protective role for GPx-1 against LPS-induced stimulation of adhesion molecule expression by modulating oxidative stress-induced CD14 expression (Fig. 7). Thus, our findings link GPx-1, as an important determinant of intracellular ROS, to LPS-mediated TLR-signaling, and illustrate an important mechanism by which GPx-1 regulates adhesion molecule expression and endothelial cell activation.

Figure 7.

GPx-1 modulates LPS response in endothelial cells by CD14 mechanisms. LPS forms a complex with soluble CD14 (sCD14) or membrane-bound CD14 (mCD14). CD14-LPS complex formation facilitates TLR4-mediated activation of endothelial cells, which results in ROS production and adhesion molecule expression. Indirectly, oxidative stress, caused by GPx-1 deficiency, increases CD14 gene expression, augmenting LPS-mediated responses. GPx-1 deficiency also increases adhesion molecule expression, contributing to endothelial cell activation. Overexpression of GPx-1 reduces intracellular ROS, decreasing adhesion molecule expression, CD14 expression, and the cellular response to LPS.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Stephanie Tribuna for expert assistance with manuscript preparation, and all other lab members for technical assistance and helpful discussions. In addition, the authors acknowledge Scott R. Oldebeken for his assistance with the design, execution, and analysis of experiments crucial to the completion of this report. This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health grants HL 61795, HV 28178, and HL 81587 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant LU 1452/1-1 (to E.L.).

References

- Cai H, Harrison D G. Endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: the role of oxidant stress. Circ Res. 2000;87:840–844. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.10.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapenna D, de Gioia S, Ciofani G, Mezzetti A, Ucchino S, Calafiore A M, Napolitano A M, Di Ilio C, Cuccurullo F. Glutathione-related antioxidant defenses in human atherosclerotic plaques. Circulation. 1998;97:1930–1934. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.19.1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raes M, Michiels C, Remacle J. Comparative study of the enzymatic defense systems against oxygen-derived free radicals: the key role of glutathione peroxidase. Free Radic Biol Med. 1987;3:3–7. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(87)90032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursini F, Maiorino M, Brigelius-Flohe R, Aumann K D, Roveri A, Schomburg D, Flohe L. Diversity of glutathione peroxidases. Methods Enzymol. 1995;252:38–53. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)52007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crack P J, Taylor J M, Flentjar N J, de Haan J, Hertzog P, Iannello R C, Kola I. Increased infarct size and exacerbated apoptosis in the glutathione peroxidase-1 (Gpx-1) knockout mouse brain in response to ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Neurochem. 2001;78:1389–1399. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgione M A, Cap A, Liao R, Moldovan N I, Eberhardt R T, Lim C C, Jones J, Goldschmidt-Clermont P J, Loscalzo J. Heterozygous cellular glutathione peroxidase deficiency in the mouse: abnormalities in vascular and cardiac function and structure. Circulation. 2002;106:1154–1158. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000026820.87824.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgione M A, Weiss N, Heydrick S, Cap A, Klings E S, Bierl C, Eberhardt R T, Farber H W, Loscalzo J. Cellular glutathione peroxidase deficiency and endothelial dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1255–H1261. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00598.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis P, Stefanovic N, Pete J, Calkin A C, Giunti S, Thallas-Bonke V, Jandeleit-Dahm K A, Allen T J, Kola I, Cooper M E, de Haan J B. Lack of the antioxidant enzyme glutathione peroxidase-1 accelerates atherosclerosis in diabetic apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 2007;115:2178–2187. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.664250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torzewski M, Ochsenhirt V, Kleschyov A L, Oelze M, Daiber A, Li H, Rossmann H, Tsimikas S, Reifenberg K, Cheng F, Lehr H A, Blankenberg S, Forstermann U, Munzel T, Lackner K J. Deficiency of glutathione peroxidase-1 accelerates the progression of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:850–857. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000258809.47285.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrero E, Hsieh C L, Francke U, Goyert S M. CD14 is a member of the family of leucine-rich proteins and is encoded by a gene syntenic with multiple receptor genes. J Immunol. 1990;145:331–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekhuizen H, Blokland I, Corsel-van Tilburg A J, Koning F, van Furth R. CD14 contributes to the adherence of human monocytes to cytokine-stimulated endothelial cells. J Immunol. 1991;147:3761–3767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jersmann H P. Time to abandon dogma: CD14 is expressed by non-myeloid lineage cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2005;83:462–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jersmann H P, Hii C S, Hodge G L, Ferrante A. Synthesis and surface expression of CD14 by human endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 2001;69:479–485. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.479-485.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landmann R, Link S, Sansano S, Rajacic Z, Zimmerli W. Soluble CD14 activates monocytic cells independently of lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2264–2271. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2264-2271.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akashi S, Saitoh S, Wakabayashi Y, Kikuchi T, Takamura N, Nagai Y, Kusumoto Y, Fukase K, Kusumoto S, Adachi Y, Kosugi A, Miyake K. Lipopolysaccharide interaction with cell surface Toll-like receptor 4-MD-2: higher affinity than that with MD-2 or CD14. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1035–1042. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, Akashi S, Miyake K, Petty H R. Lipopolysaccharide induces physical proximity between CD14 and Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) prior to nuclear translocation of NF-κB. J Immunol. 2000;165:3541–3544. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimazu R, Akashi S, Ogata H, Nagai Y, Fukudome K, Miyake K, Kimoto M. MD-2, a molecule that confers lipopolysaccharide responsiveness on Toll-like receptor 4. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1777–1782. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.11.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haziot A, Rong G W, Silver J, Goyert S M. Recombinant soluble CD14 mediates the activation of endothelial cells by lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 1993;151:1500–1507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugin J, Schurer-Maly C C, Leturcq D, Moriarty A, Ulevitch R J, Tobias P S. Lipopolysaccharide activation of human endothelial and epithelial cells is mediated by lipopolysaccharide-binding protein and soluble CD14. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2744–2748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd K L, Kubes P. GPI-linked endothelial CD14 contributes to the detection of LPS. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H473–H481. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01234.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haziot A, Ferrero E, Kontgen F, Hijiya N, Yamamoto S, Silver J, Stewart C L, Goyert S M. Resistance to endotoxin shock and reduced dissemination of gram-negative bacteria in CD14-deficient mice. Immunity. 1996;4:407–414. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore K J, Andersson L P, Ingalls R R, Monks B G, Li R, Arnaout M A, Golenbock D T, Freeman M W. Divergent response to LPS and bacteria in CD14-deficient murine macrophages. J Immunol. 2000;165:4272–4280. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.8.4272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrero E, Jiao D, Tsuberi B Z, Tesio L, Rong G W, Haziot A, Goyert S M. Transgenic mice expressing human CD14 are hypersensitive to lipopolysaccharide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2380–2384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antal-Szalmas P. Evaluation of CD14 in host defence. Eur J Clin Invest. 2000;30:167–179. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2000.00610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hack C E, Zeerleder S. The endothelium in sepsis: source of and a target for inflammation. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:S21–S27. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devitt A, Moffatt O D, Raykundalia C, Capra J D, Simmons D L, Gregory C D. Human CD14 mediates recognition and phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. Nature. 1998;392:505–509. doi: 10.1038/33169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Handy D E, Loscalzo J. Adenosine-dependent induction of glutathione peroxidase 1 in human primary endothelial cells and protection against oxidative stress. Circ Res. 2005;96:831–837. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000164401.21929.CF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Sanlioglu S, Li S, Ritchie T, Oberley L, Engelhardt J F. GPx-1 gene delivery modulates NFκB activation following diverse environmental injuries through a specific subunit of the IKK complex. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2001;3:415–432. doi: 10.1089/15230860152409068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flohe L, Gunzler W A. Assays of glutathione peroxidase. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:114–121. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopold J A, Dam A, Maron B A, Scribner A W, Liao R, Handy D E, Stanton R C, Pitt B, Loscalzo J. Aldosterone impairs vascular reactivity by decreasing glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity. Nat Med. 2007;13:189–197. doi: 10.1038/nm1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Y S, Magnenat J L, Bronson R T, Cao J, Gargano M, Sugawara M, Funk C D. Mice deficient in cellular glutathione peroxidase develop normally and show no increased sensitivity to hyperoxia. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16644–16651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allport J R, Lim Y C, Shipley J M, Senior R M, Shapiro S D, Matsuyoshi N, Vestweber D, Luscinskas F W. Neutrophils from MMP-9- or neutrophil elastase-deficient mice show no defect in transendothelial migration under flow in vitro. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:821–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawa Y, Ueki T, Hata M, Iwasawa K, Tsuruga E, Kojima H, Ishikawa H, Yoshida S. LPS-induced IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 expression in human lymphatic endothelium. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56:97–109. doi: 10.1369/jhc.7A7299.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H, Arai T, Endo N, Yamashita K, Fukuda K, Sasada M, Uchiyama T. LPS-induced ROS generation and changes in glutathione level and their relation to the maturation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Life Sci. 2006;78:926–933. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.05.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Adachi O, Ogawa T, Takeda K, Akira S. Unresponsiveness of MyD88-deficient mice to endotoxin. Immunity. 1999;11:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song P I, Abraham T A, Park Y, Zivony A S, Harten B, Edelhauser H F, Ward S L, Armstrong C A, Ansel J C. The expression of functional LPS receptor proteins CD14 and toll-like receptor 4 in human corneal cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:2867–2877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara S, Sugiyama A, Nemoto E, Rikiishi H, Takada H. Heterogeneous expression and release of CD14 by human gingival fibroblasts: characterization and CD14-mediated interleukin-8 secretion in response to lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3043–3049. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3043-3049.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S D, Ramos R A, Tobias P S, Ulevitch R J, Mathison J C. CD14, a receptor for complexes of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS binding protein. Science. 1990;249:1431–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.1698311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Jones K L, Kelly M M, Kubes P. Varying importance of soluble and membrane CD14 in endothelial detection of lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 2008;181:1446–1453. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resman N, Vasl J, Oblak A, Pristovsek P, Gioannini T L, Weiss J P, Jerala R. Essential roles of hydrophobic residues in both MD-2 and toll-like receptor 4 in activation by endotoxin. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:15052–15060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901429200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S. Toll receptor families: structure and function. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, Akira S. TLR signaling pathways. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golenbock D T, Liu Y, Millham F H, Freeman M W, Zoeller R A. Surface expression of human CD14 in Chinese hamster ovary fibroblasts imparts macrophage-like responsiveness to bacterial endotoxin. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22055–22059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugin J, Heumann I D, Tomasz A, Kravchenko V V, Akamatsu Y, Nishijima M, Glauser M P, Tobias P S, Ulevitch R J. CD14 is a pattern recognition receptor. Immunity. 1994;1:509–516. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia H P, Kline J N, Penisten A, Apicella M A, Gioannini T L, Weiss J, McCray P B., Jr Endotoxin responsiveness of human airway epithelia is limited by low expression of MD-2. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:L428–L437. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00377.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nareika A, Im Y B, Game B A, Slate E H, Sanders J J, London S D, Lopes-Virella M F, Huang Y. High glucose enhances lipopolysaccharide-stimulated CD14 expression in U937 mononuclear cells by increasing nuclear factor κB and AP-1 activities. J Endocrinol. 2008;196:45–55. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullick A E, Tobias P S, Curtiss L K. Toll-like receptors and atherosclerosis: key contributors in disease and health? Immunol Res. 2006;34:193–209. doi: 10.1385/IR:34:3:193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehr H A, Sagban T A, Ihling C, Zahringer U, Hungerer K D, Blumrich M, Reifenberg K, Bhakdi S. Immunopathogenesis of atherosclerosis: endotoxin accelerates atherosclerosis in rabbits on hypercholesterolemic diet. Circulation. 2001;104:914–920. doi: 10.1161/hc3401.093153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostos M A, Recalde D, Zakin M M, Scott-Algara D. Implication of natural killer T cells in atherosclerosis development during a LPS-induced chronic inflammation. FEBS Lett. 2002;519:23–29. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02692-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkbacka H, Kunjathoor V V, Moore K J, Koehn S, Ordija C M, Lee M A, Means T, Halmen K, Luster A D, Golenbock D T, Freeman M W. Reduced atherosclerosis in MyD88-null mice links elevated serum cholesterol levels to activation of innate immunity signaling pathways. Nat Med. 2004;10:416–421. doi: 10.1038/nm1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelsen K S, Wong M H, Shah P K, Zhang W, Yano J, Doherty T M, Akira S, Rajavashisth T B, Arditi M. Lack of Toll-like receptor 4 or myeloid differentiation factor 88 reduces atherosclerosis and alters plaque phenotype in mice deficient in apolipoprotein E. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10679–10684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403249101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roncon-Albuquerque R, Jr, Moreira-Rodrigues M, Faria B, Ferreira A P, Cerqueira C, Lourenco A P, Pestana M, von Hafe P, Leite-Moreira A F. Attenuation of the cardiovascular and metabolic complications of obesity in CD14 knockout mice. Life Sci. 2008;83:502–510. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenberg S, Rupprecht H J, Bickel C, Torzewski M, Hafner G, Tiret L, Smieja M, Cambien F, Meyer J, Lackner K J. Glutathione peroxidase 1 activity and cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1605–1613. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]