Abstract

All-cis-14,15-epoxyeicosa-5,8,11-trienoic acid (14,15-EET) is a labile, vasodilatory eicosanoid generated from arachidonic acid by cytochrome P450 epoxygenases. A series of robust, partially saturated analogs containing epoxide bioisosteres were synthesized and evaluated for relaxation of precontracted bovine coronary artery rings and for in vitro inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH). Depending upon the bioisostere and its position along the carbon chain, varying levels of vascular relaxation and/or sEH inhibition were observed. For example, oxamide 16 and N-iPr-amide 20 were comparable (ED50 1.7 μM) to 14,15-EET as vasorelaxants, but were approx. 10–35 times less potent as sEH inhibitors (IC50 59 and 19 μM, respectively); unsubstituted urea 12 showed useful activity in both assays (ED50 3.5 μM, IC50 16 nM). These data reveal differential structural parameters for the two pharmacophores that could assist the development of potent and specific in vivo drug candidates.

Introduction

The oxidative metabolism of polyunsaturated fatty acids by the cytochrome P450 branch of the eicosanoid cascade generates, inter alia, one or more regioisomeric epoxides.1 The best studied of these epoxanoids is all-cis-14,15-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid (14,15-EETa) which is derived from arachidonic acid and ascribed an impressive array of cardiovascular, pulmonary, renal, and CNS roles.2 Activation of a guanine nucleotide-binding protein (G-protein) is thought to play a pivotal role in many of the responses to 14,15-EET and often involves ADP-ribosylation of the Gsα subunit. For instance, opening of vascular calcium-sensitive potassium channels by 14,15-EET is completely thwarted by guanosine 5′-O-(2-thio)diphosphate, a G-protein inhibitor, or by an antibody against Gsα.3 A reversible and abundant high-affinity binding site for 14,15-EET and its analogs has been identified4 and shown to preferentially recognize the 14(R),15(S)-enantiomer.5 The kinetic parameters of this binding site share many characteristics in common with the canonical prostanoid and leukotriene receptors, e.g., Kd values in the low nanomolar range;4 however, characterization of the putative EET receptor at the molecular level has been elusive.6,7

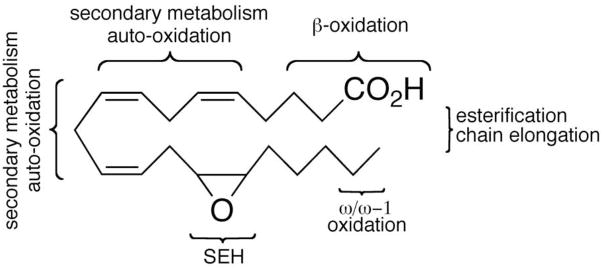

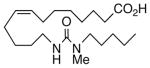

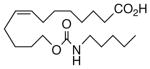

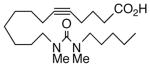

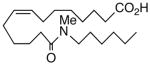

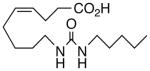

14,15-EET, in common with most eicosanoids,8 is chemically and metabolically labile (Figure 1).9 Further transformations by enzymes of the cascade,10 esterification,11 conjugation,12 β-oxidation,13 chain elongation, and hydration by soluble epoxide hydrolase14 (sEH) are well documented as inactivation or catabolic processes for 14,15-EET. The latter, in particular, appears to play a major role in regulating the intracellular levels of 14,15-EET,15 whose in vivo half-life has been estimated as a few seconds to minutes.16 Additionally, the proclivity of 14,15-EET towards auto-oxidation, a consequence of the 1,4-dienyl moieties present along the backbone,17 introduces a further layer of complication and often necessitates storage and/or handling under an inert atmosphere.9 Hence, a wide variety of factors combine to trammel the study of 14,15-EET and limit its potential therapeutic applications.

Figure 1.

Metabolism/Degradation of 14, 15-EET

Structure-activity studies in the Falck and Campbell laboratories have addressed some of these limitations and led to the introduction of partially saturated 14,15-EET agonist analogs that obviate or minimize secondary metabolism as well as auto-oxidation.18,19 More recently, Hammock and colleagues have pioneered soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition (sEHi) as an alternative, albeit indirect, strategy for pharmacological intervention in EET-dependent events.20 This approach ostensibly21 prolongs the eicosanoid’s half-life, thereby, elevating steady state levels of endogenous EETs as well as other epoxides. From an artful series of studies, lipophilic 1,3-disubstituted ureas emerged as especially efficacious in vitro and in vivo sEH inhibitors.20 Advanced members of this genre show promise as first-in-class therapeutics for a variety of diseases including diabetes, inflammation, and hypertension.22 In the present studies, we sought to develop and evaluate chimeric analogs that combine the more robust backbone of the partially saturated EET mimics with potential epoxide bioisosteres23,24 capable of functioning as stable 14,15-EET surrogates and/or as inhibitors of soluble epoxide hydrolase.25

Results and Discussion

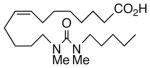

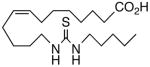

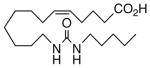

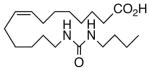

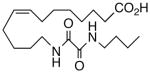

Drawing inspiration from the aforementioned studies, analog 1 was deemed a suitable point of departure for our investigation. Notably, 1 contains several key structural features, inter alia, (i) a partially saturated carbon backbone to avoid auto-oxidation17 and LOX metabolism,26 (ii) a cis-Δ8,9-olefin thought to be essential for EET agonist activity,18b and (iii) a sEH-resistant 1,3-disubstituted urea which we anticipated would function as a surrogate for the Δ14,15-epoxide.27 It was, thus, gratifying to find 1 mimics, albeit modestly, 14,15-EET as a vasorelaxant of precontracted bovine coronary artery rings (Table 1). Additionally, 1 proved to be a low nanomolar inhibitor of recombinant human sEH. Methylation of the proximal urea nitrogen of 1 provided 2, but had little influence upon the vascular properties; as anticipated, methylation dramatically attenuated sEHi activity.20 On the other hand, N-methylation of the distal urea nitrogen gave rise to regioisomer 3 and significantly improved EET-mimicry while sEHi activity degraded sharply. The differences between these N-methylated regioisomers for sEHi are similar to the differences observed previously with amide regioisomers.15 Substitution of both nitrogens as in 4 did not prove additive with respect to VR, but did further exacerbate the loss of sEHi. These data were the first convincing indications that EET agonist activity and sEHi could be at least partially differentiated in this compound series. Such differences may also be indicative of restricted orientation in the putative EET and sEH binding sites; further evidence can be found later in the series, e.g., N-methylated amides 19 and 23. A lesser level of discrimination between the two activities could also be achieved by heteroatom replacement.20 Thiourea 5 was equipotent with 14,15-EET across the entire concentration range of the vascular assay, while sEHi declined by a factor of 16 with respect to 1. On the other hand, replacement of either urea nitrogen with oxygen, i.e., 6 and 7, had relatively little influence on vessel tension, but did blunt sEHi. In light of these data, it’s tempting to speculate that hydrogen bonding or coordination to a metal center (e.g., Cu2+, Fe2+, or Zn2+) might be an important contributor to binding at the putative EET vascular receptor.

Table 1.

Vasorelaxation of Precontracted Bovine Coronary Artery and in vitro Inhibition of Recombinant Human Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase.a,b

| Compd | Analog | Vascular Relax. |

SEHi |

Compd | Analog | Vascular Relax. |

sEHi |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (10 μM) |

EC50 (μM) |

IC50 (nM) |

% (10 μM) |

EC50 (μM) |

IC50 (nM) |

||||

| 1 |  |

63 | 7.5 | 46 | 15 |  |

87 | 3.7 | 1374 |

| 2 |  |

59 | 7.6 | 71.5 | 16 |  |

89 | 1.7 | 58712 |

| 3 |  |

88 | 3.2 | 1451 | 17 |  |

70 | 4.4 | 17622 |

| 4 |  |

83 | 3.2 | 8484 | 18 |  |

64.5 | 6.1 | 79 |

| 5 |  |

99 | 1.5 | 770 | 19 |  |

64.5 | 4.3 | 11194 |

| 6 |  |

64 | 8.3 | 2834 | 20 |  |

100 | 1.7 | 10712 |

| 7 |  |

53 | 9.3 | 3480 | 21 |  |

69 | 5.7 | 272 |

| 8 |  |

29 | >10 | 48.5 | 22 |  |

74 | 4.9 | 66 |

| 9 |  |

62 | 3.1 | 43 | 23 |  |

12 | >10 | 13877 |

| 10 |  |

66 | 5.6 | 793 | 24 |  |

65 | 6.2 | 17755 |

| 11 |  |

77.5 | 2.3 | 11064 | 25 |  |

11 | >10 | 7147 |

| 12 |  |

86 | 3.5 | 16 | 26 |  |

33 | >10 | 688 |

| 13 |  |

84 | 4.6 | 152 | 27 |  |

16 | >10 | 1355 |

| 14 |  |

50 | >10 | 2596 | 28 |  |

46 | >10 | 8110 |

At 10 mM, 14,15-EET induces 85% of maximum vasorelaxation and its ED50 is 2.2 μM. For recombinant human sEH, the IC50 for 12-(3-adamantan-1-yl-ureido)dodecanoic acid (AUDA) is 3 nM.

Bioassay determinations (n) = 3–5.

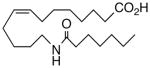

We next turned our attention to the olefinic moiety and found vascular activity was diminished in trans-olefin 8, but not acetylene 9. Accommodation of a linear carbon chain or one that is bent in the natural cis-configuration, but not trans-geometry, is consistent with a shallow binding pocket for this portion of the molecule. For sEHi, both 8 and 9 retained their low nanomolar potencies and were almost identical with that of the benchmark 1. Relocation of the cis-olefin to Δ5,6 of the carbon chain (analog 10) only modestly perturbed EET agonist activity and not at all for the related acetylene 11. This is unexpected given the regio-dependency observed18b in allied systems, e.g., cis-14,15-epoxy-eicosa-8(Z)-enoic acid is a 14,15-EET agonist while cis-14,15-epoxy-eicosa-5(Z)-enoic acid functions as a competitive antagonist. The dramatic slide in sEHi for 11, sans N-H, is consistent with established SAR for this pharmacophore.20 Shifting the urea one position right (analog 12) or left (analog 13) relative to its placement in 1 improved VR with respect to 1 whereas displacement (accompanied by the cis-olefin) two positions further from the carboxylate, resembling an ω-3 fatty acid, was counterproductive (analog 14); thus, it is difficult to discern a trend in the series 12→1→13→14 correlating urea chain position and VR. On the other hand, the IC50 for sEHi declined steadily following the same series. This appears generally consistent with the proposal20 that “one hydrophobic group should be present on each side of the urea” and confirmed indications that a six-carbon n-alkyl chain is sufficient for low nanomolar inhibition.20

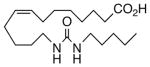

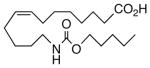

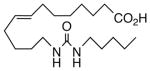

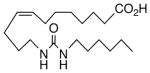

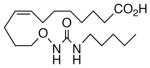

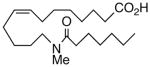

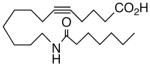

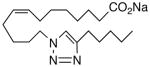

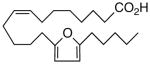

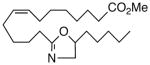

Bioisosteric epoxide replacement by N-hydroxyurea and 1,4-oxamide led to 15 and 16, respectively, both of which showed acceptable VR at 10 μM. The latter was distinguished by a somewhat better ED50, yet its IC50 for sEHi was more than three orders of magnitude greater than 1. In contrast to the outcome from conversion of 1 into 4, the N,N′-dimethylation of 16 to give 17 reduced its ability to relax the vessel while simultaneously moderating the loss of sEHi seen with 16.

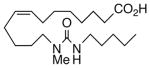

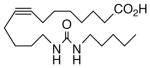

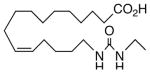

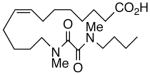

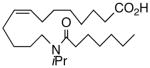

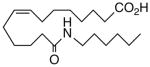

The regioisomeric amide bioisosteres 18 and 22 displayed potentially useful sEHi activities, but were lackluster EET mimics. The analogous N-methylated derivatives 19 and 23, respectively, as well as acetylene 21 lost potency, except for a small improvement in the EC50 of 19. sEHi by N-isopropyl 20 was likewise depressed, but the trend towards a more robust response in the vascular assay portended in 19 was clearly evident in this example. Whether the enhancement can be attributed to a hydrophobic binding pocket remains unclear at present.

A selection of nitrogen and oxygen heterocyclic bioisosteres, viz., triazole 24, furan 25, and 2-oxazoline 26, were prepared based upon the template in 1. They did not appear to offer any pharmacological advantage and were not pursued further. The loss of both VR and sEHi activities in the tetranor-ureas 27 and 28 is noteworthy given prior reports that chain-shortened 14,15-EETs retain much of their biological activity in the vasculature.13 Formally, 27 and 28 can be envisioned as arising from 1 and 9, respectively, via two cycles of β-oxidation.13 It will be of interest to determine if this is also a significant route of inactivation in vivo for the EET surrogates identified in this study.

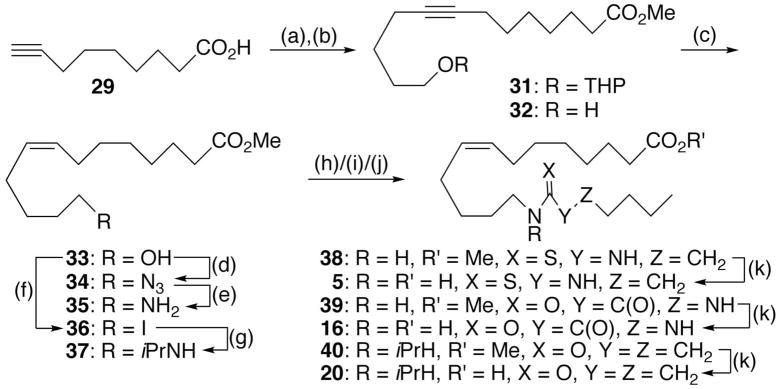

Chemistry

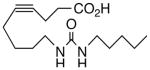

The syntheses of thiourea 5, oxamide 16, and N-isopropylamide 20 are summarized in Scheme 1 and are representative of the methodology used to prepare the other analogs. Following literature precedent,28 the dianion of commercial non-8-ynoic acid (29) was alkylated with one equivalent of 2-(4-bromobutoxy)-tetrahydro-2H-pyran29 (30) in THF/HMPA (4:1). The resultant disubstituted acetylene 31 gave rise to alcohol 32 following acidic hydrolysis in methanol. Semi-hydrogenation over P-2 nickel created cis-olefin 33 that was subjected to azidation using diphenylphosphoryl azide (DPPA) under Mitsunobu conditions. Staudinger reduction of the product, azide 34, led to primary amine 35. Reaction of the latter with n-pentylisothiocyanate or a combination of 2-(butylamino)-2-oxoacetic acid30 and 2-(7-aza-1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HATU) was unremarkable and furnished thiourea 38 and oxamide 40, respectively. Alternatively, 33 was converted with Ph3P/I2 to iodide 36 that was then displaced with excess iso-propylamine at 80 °C. HATU-induced condensation of the product 37 with n-heptanoic acid delivered amide 42 in good overall yield. Saponification of 38, 40, and 42 afforded the corresponding free acids 5, 16, and 20, respectively.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Representative Analogsa

a Reagents and conditions: (a) n-BuLi, THF/HMPA (4:1), −78 °C to 0 °C, 2h; then 30, −78 °C to 23 °C, 12 h; (b) p-MeC6H4SO3H (cat), MeOH, 23 °C, 12 h, 55% (2 steps); (c) Ni(OAc)2/NaBH4/H2NCH2CH2NH2, H2, EtOH, 23 °C, 1 h, 90%; (d) Ph3P/DEAD/DPPA, THF, −20 °C to 23 °C, 4 h, 65%; (e) Ph3P, THF/H2O, 23 °C, 12 h; (f) Ph3P/I2, THF, 0 °C, 1 h, 83%; (g) i-PrNH2/K2CO3, THF, 80 °C, 12 h, 70%; (h) 35/n-pentylisothiocyanate, THF, 23°C, 12 h, 70%; (i) 35/HOC(O)C(O)NHC4H9/HATU, CH2Cl2, 23 °C, 12 h, 76%; (j) 37/EDCI/n-heptanoic acid, DMF, 23 °C, 12 h, 77%; (k) LiOH, THF/H2O, 23 °C, 12 h, 90–95%.

Conclusions

Herein, we have shown N-substituted ureas, oxamides, and N-substituted amides are suitable bioisosteres for fatty acid epoxides whereas the urethanes, triazole, 2-oxazoline, furan, and secondary amides described above are not. In concert with literature observations, secondary amides were powerful sEH inhibitors as were 1,3-disubstituted ureas, if the appendages are sufficiently lipophilic. Some epoxide surrogates behaved as both good EET agonists and powerful sEH inhibitors. Overall, there was no correlation between vascular relaxation and sEHi potencies, suggesting differential structural parameters for the two pharmacophores. It is anticipated that these dual-activity analogs could function additively and provide a platform for the development of the next generation of analogs intended for in vivo applications.

Experimental Section

General Procedures

Unless stated otherwise, yields refer to purified products and are not optimized. Final compounds were judged ≥95% pure by HPLC. All moisture-sensitive reactions were performed under an argon atmosphere using oven-dried glassware and anhydrous solvents. Anhydrous solvents were freshly distilled from sodium benzophenone ketyl, except for CH2Cl2, which was distilled from CaH2. Extracts were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and filtered prior to removal of all volatiles under reduced pressure. Unless otherwise noted, commercially available materials were used without purification. Silica gel chromatography was performed using E. Merck silica gel 60 (240–400 mesh). Thin layer chromatography was performed using precoated plates purchased from E. Merck (silica gel 60 F254, 0.25 mm). Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) splitting patterns are described as singlet (s), doublet (d), triplet (t), quartet (q), and broad (br); the value of chemical shifts (d) are given in ppm relative to residual solvent (chloroform δ = 7.27 for 1H NMR or δ = 77.23 for proton decoupled 13C NMR) and coupling constants (J) are given in Hertz (Hz). The Michigan State University Mass Spectroscopy Facility or Medical College of Wisconsin provided high-resolution mass spectral analyses.

Methyl 13-hydroxytridec-8-ynoate (32)

n-Butyllithium (6.2 mL of 2.5 M solution in hexanes, 15.5 mmol) was added dropwise with stirring to a −78 °C solution of non-8-ynoic acid (29) (1 g, 6.5 mmol, G. F. Smith Chem. Co.) in THF/HMPA (4:1, 50 mL) under an argon atmosphere. After 30 min, the reaction mixture was warmed to 0 °C and maintained at this temperature for 2 h. After re-cooling to −78 °C, a solution of 2-(4-bromobutoxy)-tetrahydro-2H-pyran29 (30) (1.68 g, 7.14 mmol) in THF (10 mL) was added and the reaction temperature was slowly raised over 3 h to 23 °C. After 12 h, the reaction mixture was quenched with saturated aq. NH4Cl solution (5 mL) and the pH was adjusted to ~ 4 using 1M oxalic acid. The mixture was extracted with EtOAc (2 × 50 mL) and the combined extracts were washed with water (2 × 10 mL), brine (10 mL), dried, and concentrated under reduced pressure. Crude 31 was dissolved in methanol (20 mL) to which was added p-toluenesulfonic acid (PTSA, 25 mg). After 12 h, the solvent was evaporated and the residue was purified by SiO2 column chromatography to give 32 (700 mg, 55%) as a colorless oil. TLC: EtOAc/hexanes (1:1), Rf ~ 0.55; 1H NMR (300 MHz) δ 3.68 (s, 3H), 3.66 (t, 2H, J = 6.2 Hz), 2.31 (t, 2H, J = 7.3 Hz), 2.10–2.24 (m, 4H), 1.30–1.75 (m, 12H); 13C NMR (75 MHz) δ 174.55, 80.70, 80.14, 62.75, 51.73, 34.24, 32.13, 29.04, 28.84, 28.62, 25.56, 25.05, 18.85, 18.75; HRMS calcd for C14H25O3 [M+1]+ 241.1804, found 241.1807.

Methyl 13-hydroxytridec-8(Z)-enoate (33)

NaBH4 (16 mg, 0.416 mmol) was added in portions with vigorous stirring to a room temperature solution of Ni(OAc)2·4H2O (103.7 mg, 0.416 mmol) in absolute EtOH (7 mL) under a hydrogen atmosphere (1 atm). After 15 min, freshly distilled ethylenediamine (56 μl, 0.833 mmol) was added to the black suspension followed after a further 15 min by a solution of 32 (400 mg, 1.66 mmmol) in absolute EtOH (2 mL). After 1 h, the reaction mixture was diluted with Et2O (10 mL) and passed through a small bed of silica gel. The bed was rinsed with another portion of Et2O (10 mL). The combined ethereal filtrates were concentrated under reduced pressure to afford methyl 13-hydroxytridec-8(Z)-enoate (33) (345 mg, 98%) as a colorless oil. TLC: EtOAc/hexane (1:1), Rf ~ 0.42; 1H NMR (300 MHz) δ 5.32–5.48 (m, 2H), 3.66 (s, 3H), 3.64 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H) 2.30 (t, J = 7.4, 2H), 1.96–2.10 (m, 4H), 1.54–1.66 (m, 4H), 1.20–1.44 (m, 10H); 13C NMR (75 MHz) δ 174.77, 130.30, 129.70, 62.95, 51.73, 34.28, 32.42, 29.64, 29.17, 29.03, 27.29, 27.10, 26.03, 25.07; HRMS calcd for C14H25O3 [M+1]+ 243.1960, found 243.1959.

Methyl 13-azidotridec-8(Z)-enoate (34)

Diethyl azodicaboxylate (DEAD; 243 μL, 1.54 mmol) was added dropwise to a −20 °C solution of PPh3 (TPP; 405 mg, 1.54 mmol) in dry THF (10 mL) under an argon atmosphere. After 10 min, alcohol 33 (340 mg, 1.4 mmol) dissolved in dry THF (5 mL) was added dropwise. After 30 min, the reaction mixture was allowed to come to 0 °C and diphenylphosphoryl azide (DPPA; 364 μL, 1.68 mmol) was added dropwise. After stirring for 4 h at rt, the reaction mixture was quenched with water (10 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic extracts were washed with brine (20 mL), dried, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by SiO2 column chromatography eluting with 5% EtOAc/hexane to afford 34 (240 mg, 65%). TLC: 10% EtOAc/hexanes, Rf ~ 0.45; 1H NMR (300 MHz) δ 5.28–5.44 (m, 2H), 3.67 (s, 3H), 3.24 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 2.30 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.96–2.10 (m, 4H), 1.56–1.64 (m, 4H), 1.28–1.42 (m, 8H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 174.24, 130.69, 129.17, 51.64, 51.55, 34.26, 29.66, 29.22, 29.08, 28.61, 27.33, 26.96, 26.83, 25.09; IR (neat) 2985, 2954, 2845, 2106, 1754, 1250, 1104, 1029 cm−1; HRMS calcd for C14H25N3O2 [M+1]+ 267.3672, found 267.3680.

Methyl 13-aminotridec-8(Z)-enoate (35)

Triphenylphosphine (TPP; 89 mg, 0.338 mmol) was added to a stirring, room temperature solution of azide 34 (90 mg, 0.33 mmol) in THF (2 mL) containing 4 drops of deionized water. After 12 h, the reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (2 mL), dried, and concentrated in vacuo to give 35 (64 mg, 78%) as a viscous, colorless oil that was used directly in the next reaction without further purification. TLC: 20% MeOH/CH2Cl2, Rf ~ 0.25; 1H NMR (300 MHz) δ 6.22 (bs, 2H), 5.24–5.36 (m, 2H), 3.64 (s, 3H), 2.79–2.88 (m, 2H), 2.27 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 1.92–2.08 (m, 4H), 1.53–1.68 (m, 4H), 1.21–1.44 (m, 8H); 13C NMR (100 MHz) δ 174.54, 130.46, 129.40, 51.69, 41.08, 34.30, 29.70, 29.25, 29.11, 27.34, 25.12, 24.83; HRMS calcd for C14H27NO2 [M+1]+ 241.3697, found 241.3705.

Methyl 13-(3-pentylthioureido)tridec-8(Z)-enoate (38)

A solution of amine 35 (80 mg, 0.33 mmol) in THF (3 mL) was added dropwise to a stirring, 0 °C solution of n-pentylisothiocyanate (80 mg, 0.29 mmol) in THF (4 mL). After 12 h at room temperature, all volatiles were removed under reduced pressure and the residue was purified by SiO2 column chromatography eluting with 30% EtOAc/hexane to afford 38 (90 mg, 70%) as a colorless oil. TLC: EtOAc/hexanes (1:1), Rf ~ 0.65; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 5.72 (br s, NH), 5.29–5.35 (m, 2H), 3.66 (s, 3H), 3.40 (br s, NH), 2.30 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 1.97–2.05 (m, 4H), 1.57–1.64 (m, 6H), 1.26–1.42 (m, 12H), 0.88 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz) δ 174.54, 173.75, 130.17, 129.94. 51.67, 44.68, 34.30, 29.72, 29.64, 29.21, 29.26, 29.16, 27.55, 27.35, 27.31, 25.15, 26.98, 25.13, 22.74, 14.31; HRMS calcd for C20H38N2O2S [M+1]+ 371.2663, found 371.2669.

13-(3-n-Pentylthioureido)tridec-8(Z)-enoic acid (5)

LiOH (840 mL of a 1 M soln) was added to a 0 °C solution of methyl ester 38 (80 mg, 0.21 mmol) in THF/H2O (4:1, 10 mL). After stirring at room temperature for 12 h, the THF was evaporated under reduced pressure, the remaining reaction mixture was diluted with H2O (5 mL), re-cooled to 0 °C, and the pH adjusted to 4 using 1 M oxalic acid. The reaction mixture was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic extracts were washed with brine (20 mL), dried, concentrated under reduced pressure, and the residue was purified by SiO2 column chromatography eluting with EtOAc/hexane (1:1) to afford 5 (67 mg, 87%) as a colorless oil. TLC: 60% EtOAc/hexanes, Rf ~ 0.35; mp 84.4–85.2 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz) δ 5.28–5.36 (m, 2H), 3.38 (br s, 2H), 2.34 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.97–2.05 (m, 4H), 1.58–1.65 (m, 6H), 1.26–1.42 (m, 12H), 0.88 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz) δ 181.05, 179.53, 130.72, 129.25, 44.43, 34.15, 29.45, 29.32, 29.23, 28.92, 28.83, 28.68, 27.16, 27.03, 24.75, 22.55, 14.17; LCMS (M+1)+ 357; HRMS calcd for C19H36N2O2S [M+1]+ 357.2267, found 357.2572.

Methyl 13-(2-(n-butylamino)-2-oxoacetamido)tridec-8(Z)-enoate (39)

A mixture of 2-(n-butylamino)-2-oxoacetic acid30 (60 mg, 0.413 mmol), amine 35 (119 mg, 0.496 mmol), and 2-(7-aza-1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HATU; 172 mg, 0.455 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL) was stirred at room temperature overnight, then all volatiles were removed in vacuo. The resultant residue was purified by SiO2 column chromatography using 20% EtOAc/hexane as eluent to furnish oxamide 39 (112 mg, 76%) as a white solid, mp 112.5–112.9 °C. TLC: EtOAc/hexane (1:1), Rf ~ 0.62; 1H NMR (400 MHz) δ 7.42–7.67 (m, 2H), 5.23–5.42 (m, 2H), 4.07–4.14 (m, 2H), 3.65 (s, 3H), 3.25–3.38 (m, 4H), 2.28 (t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.96–2.08 (m, 4H), 1.49–1.62 (m, 4H), 1.21–1.41 (m, 10H), 0.92 (t, 3H, J = 7.1 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz) δ 174.44, 160.15, 130.57, 129.22, 51.62, 39.78, 39.59, 34.23, 31.41, 29.65, 29.20, 29.06, 28.99, 27.32, 27.08, 26.90, 25.07, 20.18, 13.85; HRMS calcd for C20H36N2O4 [M+1]+ 369.2753, found 369.2757.

13-(2-(n- Butylamino)-2-oxoacetamido)tridec-8(Z)-enoic acid (16)

Hydrolysis of 39 (100 mg, 0.272 mmol) using LiOH as described for 38 afforded 16 (76 mg, 90%) as a white solid, mp 101.4–102.2 °C. TLC: EtOAc/hexane (1:1), Rf ~ 0.18; 1H NMR (500 MHz) δ 7.94 (br s, 1H), 7.63 (br s, 1H), 5.39-5.30 (m, 2H), 3.35-3.30 (m, 4H), 2.37 (t, 2H, J = 7.3 Hz), 2.09-2.01 (m, 4H), 1.68-1.52 (m, 6H), 1.41-1.34 (m, 10 H), 0.94 (t, 3H, J = 7.3 H); 13C NMR (125 MHz) δ 178.9, 160.1, 160.0, 130.5, 129.2, 39.8, 39.7, 34.0, 31.2, 29.4, 28.9, 28.8, 27.0, 26.9, 26.8, 24.7, 20.1, 13.8; LC/API-MS m/z 376 [M+Na]+; HRMS calcd for C19H34N2O4 [M+1]+ 355.2597, found 355.2594.

Methyl 13-iodotridec-8(Z)-enoate (36)

tetra-n-Butylammonium iodide (941 mg, 2.58 mmol) and DDQ (1.52 g, 2.58 mmol) were added in sequence to a solution of triphenylphosphine (676 mg, 2.58 mmol) and methyl 13-hydroxytridec-8(Z)-enoate (33) (520 mg, 2.15 mmol) in dry dichloromethane (30 mL) at room temperature. After 3 h, the reaction mixture was quenched with water (2 mL) and extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 15 mL). The combined extracts were dried, concentrated under reduced pressure, and the residue was purified by SiO2 column chromatography using 3–6% EtOAc/hexanes as eluent to give methyl 13-iodotridec-8(Z)-enoate (36) (514 mg, 83%) as a pale yellow oil. TLC: 10% EtOAc/hexanes, Rf ~ 0.6; 1H NMR (300 MHz) δ 5.28–5.42 (m, 2H), 3.66 (s, 3H), 3.18 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 2.30 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.98–2.08 (m, 4H), 1.79–1.87 (m, 2H), 1.24–1.62 (m, 10H); 13C NMR (75 MHz) δ 174.46, 130.73, 129.16, 51.68, 34.28, 33.28, 30.72, 29.68, 29.25, 29.11, 27.36, 26.28, 25.12, 7.20. HRMS calcd for C14H25IO2 [M+1]+ 353.1004, found 353.1010.

Methyl 13-(isopropylamino)tridec-8(Z)-enoate (37)

Isopropylamine (418 mg, 7.10 mmol) and K2CO3 (596 mg, 4.26 mmol) were added sequentially to a room temperature solution of methyl 13-iodotridec-8(Z)-enoate (500 mg, 1.42 mmol) in dry tetrahydrofuran (7 mL). The mixture was heated in a sealed tube at 90 °C for 12 h, then cooled to rt, diluted with water (2 mL), filtered, and the filtrate was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 15 mL). The combined organic extracts were dried, concentrated under reduced pressure, and the residue was purified by SiO2 column chromatography using a gradient from 2–5% MeOH/CH2Cl2 as eluent to give methyl 13-(N-isopropylamino)tridec-8(Z)-enoate (37) (314 mg, 78%) as a pale yellow oil. TLC: 5% MeOH/CH2Cl2, Rf ~ 0.6; 1H NMR (300 MHz) δ 5.30–5.40 (m, 2H), 3.66 (s, 3H), 2.72–2.84 (m, 1H), 2.58 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.30 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.98–2.08 (m, 4H), 1.22–1.68 (m, 12H), 1.05 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (75 MHz) δ 174.28, 130.57, 128.58, 51.43, 49.93, 44.69, 34.05, 29.43, 29.01, 28.87, 27.14, 26.64, 26.02, 24.86, 19.33; HRMS calcd for C17H33NO2 [M+1]+ 284.2590, found 384.2592.

Methyl 13-(isopropyl-n-heptanamido)tridec-8(Z)-enoate (40)

Solid EDCI [1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride] (75 mg, 0.39 mmol) was added in portions to a room temperature solution of amine 37 (110 mg, 0.39 mmol), DMAP (48 mg, 0.39 mmol) and n-heptanoic acid (51 mg, 0.09 mmol) in dry DMF (3 mL). After 12 h, the reaction mixture was diluted with water (10 mL) and extracted with Et2O (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic extracts were washed with brine, dried, and evaporated in vacuo. The residue was purified via SiO2 column chromatography to give methyl 13-(isopropyl-n-heptanamido)tridec-8(Z)-enoate (40) (115 mg, 77%) as a colorless oil. TLC: EtOAc/hexanes (1:1), Rf ~ 0.6; 1H NMR (300 MHz, ~3:2 mixture of rotamers) δ 5.25–5.38 (m, 2H), 4.61–4.67 and 3.99–4.04 (m, 1H for two rotamers), 3.66 (s, 3H), 3.04–3.13 (m, 2H), 2.20–2.36 (m, 4H), 1.90–2.06 (m, 4H), 1.20–1.64 (m, 20H), 1.15 and 1.09 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 6H for two rotamers), 0.85 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz) δ 176.96, 174.32, 172.76, 130.65, 129.99, 129.73, 129.04, 51.52, 48.36, 45.63, 43.54, 41.06, 34.32, 34.16, 33.94, 33.87, 31.82, 31.80, 31.63, 31.14, 29.82, 29.64, 29.58, 29.32, 29.15, 29.02, 27.71, 27.38, 27.31, 27.24, 27.08, 26.83, 25.84, 25.68, 25.03, 22.68, 22.62, 21.49, 20.61, 14.18; HRMS calcd for C24H45NO3 [M+1]+ 396.3478, found 396.3475.

13-(N-isopropylheptanamido)tridec-8(Z)-enoic acid (20)

Hydrolysis of 40 using LiOH as described for 38 afforded 20 (92%) as a colorless oil. TLC: 75% EtOAc/hexanes, Rf ~ 0.40; 1H NMR (300 MHz, mixture of rotamers) δ 5.25–5.39 (m, 2H), 4.63–4.68 and 4.02–4.07 (m, 1H for two rotamers in 55/45 ratio), 3.06–3.11 (m, 2H), 2.23–2.36 (m, 4H), 1.98–2.06 (m, 4H), 1.20–1.71 (m, 20H), 1.18 and 1.11 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 6H for two rotamers in 55/45 ratio), 0.87 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz) δ 179.00, 178.24, 173.51, 173.08, 130.81, 130.08, 129.95, 129.95, 129.15, 48.57, 45.66, 43.61, 41.26, 34.36, 34.28, 34.23, 34.10, 31.92, 31.86, 31.66, 31.26, 29.67, 29.60, 29.44, 29.40, 29.31, 29.17, 29.10, 28.97, 28.85, 28.49, 27.93, 27.47, 27.40, 27.32, 26.94, 26.81, 25.81, 25.93, 25.75, 24.99, 24.9, 22.78, 21.54, 20.75, 14.29; ESI-LC/MS m/z 380 (M-H)+; HRMS calcd for C23H43NO3 [M+1]+ 382.3321, found 382.3324.

Bioassays

The influence of eicosanoids and analogs on coronary vascular tone was measured by the induced changes in isometric tension of bovine coronary artery rings precontracted with the thromboxane-mimetic, U46619, as previously described.18a,31 Synthetic 14,15-EET was used as a control. All assays were conducted in triplicate or greater and are means ± 10% SD of the reported value.

Recombinant human sEH was produced in a baculovirus expression system32 and was purified by affinity chromatography.33 Inhibition potencies (IC50s) were determined using a fluorescent-based assay.34 Human sEH (~1 nM) was incubated with inhibitors (0.4 < [I]final < 100,000 nM) for 5 min in 25 mM bis-tris/HCl buffer (200 mL, pH 7.0) at 30 °C before the substrate, cyano(2-methoxynaphthalen-6-yl)methyl trans-(3-phenyl-oxyyran-2-yl]methyl carbonate (CMNPC; [S]final = 5 μM), was added. Activity was assessed by measuring the appearance of the fluorescent 6-methoxynaphthaldehyde product (λem = 330 nm, λex = 465 nm) at 30 °C during a ten min incubation (Spectramax M2, Molecular Device, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA).34 IC50s refer to the concentrations of inhibitor that reduced activity by 50% and are the averages of three replicates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support provided in part by NIH (GM32178, DK38226, HL51055, HL85727), NIEHS (R37 ES02710, RO1 13833), NIH/NIEHS (ES04699), and the Robert A. Welch Foundation.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: 14,15-EET, cis-14,15-epoxyeicosa-5(Z),8(Z),11(Z)-trienoic acid; sEH, soluble epoxide hydrolase; sEHi, soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition; VR, vascular relaxation.

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and copies of the 1H/13C NMR spectra for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Capdevila JH, Falck JR, Imig JD. Roles of the Cytochrome Arachidonic Acid Monooxygenases in the Control of Systemic Blood Pressure and Experimental Hypertension. Kid Internat. 2007;72:683–689. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Moran JH, Mitchell LA, Bradbury JA, Qu W, Zeldin DC, Schnellmann RG, Grant DF. Analysis of the Cytotoxic Properties of Linoleic Acid Metabolites Produced by Renal and Hepatic P450s. Tox Appl Pharm. 2000;168:268–279. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.9053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Fer M, Dreano Y, Lucas D, Corcos L, Salauen J-P, Berthou F, Amet Y. Metabolism of Eicosapentaenoic and Docosahexaenoic acids by Recombinant Human Cytochromes P450. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;471:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Barbosa-Sicard E, Markovic M, Honeck H, Christ B, Muller DN, Schunck WH. Eicosapentaenoic Acid Metabolism by Cytochrome P450 Enzymes of the CYP2C Subfamily. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;329:1275–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Yi XY, Gauthier KM, Cui L, Nithipatikom K, Falck JR, Campbell WB. Metabolism of Adrenic Acid to Vasodilatory 1α,1β-Dihomo-epoxyeicosatrienoic Acids by Bovine Coronary Arteries. Am J Physiol. 2007;292:H2265–H2274. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00947.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reviews: Fleming I. Vascular Cytochrome P450 Enzymes: Physiology and Pathophysiology. Trends Cardiovas Med. 2008;18:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2007.11.002.Spector AA, Norris AW. Action of Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acids on Cellular Function. Am J Physiol. 2007;292:C996–C1012. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00402.2006.Capdevila JH, Falck JR, Harris RC. Cytochrome P450 and Arachidonic Acid Bioactivation: Molecular and Functional Properties of the Arachidonate Monooxygenase. J Lipid Res. 2000;41:163–181.

- 3.Li PL, Campbell WB. Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acids Activate K+ Channels in Coronary Smooth Muscle Through a Guanine Nucleotide Binding Protein. Circ Res. 1997;80:877–884. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.6.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang W, Holmes BB, Gopal VR, Kishore RVK, Sangras B, Yi XY, Falck JR, Campbell WB. Characterization of 14,15-Epoxyeicosatrienoyl-Sulfonamides as 14,15- Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acid Agonists: Use for Studies of Metabolism and Ligand Binding. J Pharm Exp Ther. 2007;321:1023–1031. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.119651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong PY, Lin KT, Yan YT, Ahern D, Iles J, Shen SY, Bhatt RK, Falck JR. 14(R),15(S)-Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acid (14(R),15(S)-EET) Receptor in Guinea Pig Mononuclear Cell Membranes. J Lipid Mediators. 1993;6:199–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang W, Tuniki VR, Anjaiah S, Falck JR, Hillard CJ, Campbell WB. Characterization of Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acid Binding Site in U937 Membranes Using a Novel Radiolabeled Agonist, 20-125l–14,15-Epoxyeicosa-8(Z)-Enoic Acid. J Pharm Exp Ther. 2008;324:1019–1027. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.129577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Interactions of EETs with known receptors and binding sites have been reported, but none fully account for the physiological effects of EETs: Behm DJ, Ogbonna A, Wu C, Burns-Kurtis CL, Douglas SA. Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acids Function as Selective, Endogenous Antagonists of Native Thromboxane Receptors: Identification of a Novel Mechanism of Vasodilation. J Pharm Exp Therap. 2009;328:231–239. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.145102.Wang X-L, Lu T, Cao S, Shah VH, Lee H-C. Inhibition of ATP Binding to the Carboxyl Terminus of Kir6.2 by Epoxyeicosatrienoic. Acids Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:1041–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.06.005.Watanabe H, Vriens J, Prenen J, Droogmans G, Voets T, Nilius B. Anandamide and Arachidonic Acid Use Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acids to Activate TRPV4 Channels. Nature. 2003;424:434–438. doi: 10.1038/nature01807.

- 8.(a) Fitzpatrick FA. The Stability of Eicosanoids: Analytical Consequences. Develop Pharm. 1980;1:189–201. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fiore S, Serhan CN. Phospholipid Bilayers Enhance the Stability of Leukotriene A4 and Epoxytetraenes: Stabilization of Eicosanoids by Liposomes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;159:477–481. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)90017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falck JR, Yadagiri P, Capdevila J. Synthesis of Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acids and Heteroatom Analogs. In: Murphy RC, Fitzpatrick FA, editors. Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 187. Academic Press, Inc; San Diego: 1990. pp. 357–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Capdevila JH, Mosset P, Yadagiri P, Lumin S, Falck JR. NADPH- Dependent Microsomal Metabolism of 14,15-Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acid to Diepoxides and Epoxyalcohols. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1988;261:122–133. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(88)90111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Le Quere V, Plee-Gautier E, Potin P, Madec S, Salaün JP. Human CYP4F3s are the Main Catalysts in the Oxidation of Fatty Acid Epoxides. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:1446–1458. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300463-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Capdevila JH, Kishore V, Dishman E, Blair IA, Falck JR. A Novel Pool of Rat Liver Inositol and Ethanolamine Phospholipids Contains Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acids (EETs) Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1987;146:638–644. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90576-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Karara A, Dishman E, Falck JR, Capdevila JH. Endogenous Epoxyeicosatrienoyl-phospholipids. A Novel Class of Cellular Glycerolipids Containing Epoxidized Arachidonate Moieties. J Biol Chem. 1999;266:7561–7569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chen J, Chen JK, Falck JR, Anjaiah S, Capdevila JH, Harris RC. Mitogenic Activity and Signaling Mechanism of 2-(14,15-Epoxyeicosatrienoyl)glycerol, a Novel Cytochrome P450 Arachidonate Metabolite. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3023–3034. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01482-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spearman ME, Prough RA, Estabrook RW, Falck JR, Manna S, Leibman KC, Murphy RC, Capdevila J. Novel Glutathione Conjugates formed from Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acids (EETs) Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;242:225–230. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90496-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang X, Weintraub NL, Oltman CL, Stoll LL, Kaduce TL, Harmon S, Dellsperger KC, Morisseau C, Hammock BD, Spector AA. Human Coronary Endothelial Cells Convert 14,15-EET to a Biologically Active Chain-Shortened Epoxide. Am J Physiol. 2002;283:H2306–H2314. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00448.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chacos N, Capdevila J, Falck JR, Manna S, Martin-Wixtrom C, Gill SS, Hammock BD, Estabrook RW. The Reaction of Arachidonic Acid Epoxides (Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acids) with a Cytosolic Epoxide Hydrolase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1983;223:639–648. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90628-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim IH, Heirtzler FR, Morisseau C, Nishi K, Tsai HJ, Hammock BD. Optimization of Amide-Based Inhibitors of Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase with Improved Water Solubility. J Med Chem. 2005;48:3621–3629. doi: 10.1021/jm0500929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Catella F, Lawson JA, Fitzgerald DJ, FitzGerald GA. Endogenous Biosynthesis of Arachidonic Acid Epoxides in Humans: Increased Formation in Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5893–5897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin H, Porter NA. New Insights Regarding the Autoxidation of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids. Antioxid Redox Sign. 2005;7:170–184. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Gauthier KM, Deeter C, Krishna UM, Reddy YK, Bondlela M, Falck JR, Campbell WB. 14,15-Epoxyeicosa-5(Z)-Enoic Acid: A Selective Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acid Antagonist That Inhibits Endothelium-Dependent Hyperpolarization and Relaxation in Coronary Arteries. Circ Res. 2002;90:1028–1036. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000018162.87285.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Falck JR, Krishna UM, Reddy YK, Kumar PS, Reddy KM, Hittner SB, Deeter C, Sharma KK, Gauthier KM, Campbell WB. Comparison of Vasodilatory Properties of 14,15-EET Analogs: Structural Requirements for Dilation. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:H337–H349. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00831.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gauthier KM, Jagadeesh SG, Falck JR, Campbell WB. 14,15-Epoxyeicosa-5(Z)-enoic-mSI: A 14,15- and 5,6-EET Antagonist in Bovine Coronary Arteries. Hypertension. 2003;42:555–561. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000091265.94045.C7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Gauthier KM, Falck JR, Reddy LM, Campbell WB. 14,15-EET Analogs: Characterization of Structural Requirements for Agonist and Antagonist Activity in Bovine Coronary Arteries. Pharm Res. 2004;49:515–524. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Yang W, Holmes BB, Gopal VR, Kishore RVK, Sangras B, Yi XY, Falck JR, Campbell WB. Characterization of 14,15-Epoxyeicosatrienoyl-Sulfonamides as 14,15-Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acid Agonists: Use for Studies of Metabolism and Ligand Binding. J Pharm Exp Ther. 2007;321:1023–1031. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.119651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.For 11,12-EET analogs, see: Falck JR, Reddy LM, Reddy YK, Bondlela M, Krishna UM, Ji Y, Sun J, Liao JK. 11,12-Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acid (11,12-EET): Structural Determinants for Inhibition of TNF-α-Induced VCAM-1 Expression. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:4011–4014. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.08.060.Dimitropoulou C, West L, Field MB, White RE, Reddy LM, Falck JR, Imig JD. Protein Phosphatase 2A and Ca2+-Activated K+ Channels Contribute to 11,12-Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acid Analog Mediated Mesenteric Arterial Relaxation. Prost Oth Lipid Mediat. 2007;83:50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2006.09.008.Imig JD, Dimitropoulou C, Reddy DS, White RE, Falck JR. Afferent Arteriolar Dilation to 11,12-EET Analogs Involves PP2A Activity and Ca2+-Activated K+ Channels. Microcirculation. 2008;15:37–150. doi: 10.1080/10739680701456960.For 5,6-EET, see: Yang W, Gauthier KM, Reddy LM, Sangras B, Sharma KK, Nithipatikom K, Falck JR, Campbell WB. Stable 5,6-Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acid Analog Relaxes Coronary Arteries through Potassium Channel Activation. Hypertension. 2005;45:681–686. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000153790.12735.f9.

- 20.Morisseau C, Goodrow MH, Dowdy D, Zheng J, Greene JF, Sanborn JR, Hammock BD. Potent Urea and Carbamate Inhibitors of Soluble Epoxide Hydrolases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8849–8854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.8849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.sEH inhibitors may also have direct effects upon vascular tissue: Olearczyk JJ, Field MB, Kim I-H, Morisseau C, Hammock BD, Imig JD. Substituted Adamantyl-Urea Inhibitors of the Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase Dilate Mesenteric Resistance Vessels. J Pharm Exp Therapeu. 2006;318:1307–1314. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.103556.

- 22.Other functionality may also be useful for sEHi: Anandan S-K, Do ZN, Webb HK, Patel DV, Gless RD. Non-Urea Functionality as the Primary Pharmacophore in Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase Inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:1066–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.01.013.

- 23.Wermuth CG, de la Fontaine J. Molecular Variations Based on Isosteric Replacements. In: Wermuth CG, editor. Practice of Medicinal Chemistry. 2. Elsevier; London: 2003. pp. 189–214. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Examples of other epoxide mimics: Prestwich GD, Kuo JW, Park SK, Loury DN, Hammock BD. Inhibition of Epoxide Metabolism by αβ-Epoxyketones and Isosteric Analogs. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;242:11–15. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90473-4.Van Duuren BL, Melchionne S, Blair R, Goldschmidt BM, Katz C. Carcinogenicity of Isosteres of Epoxides and Lactones: Aziridine Ethanol, Propane Sultone, and Related Compounds. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1971;46:143–149.Regueiro-Ren A, Borzilleri RM, Zheng X, Kim SH, Johnson JA, Fairchild CR, Lee FY, Long BH, Vite GD. Synthesis and Biological Activity of Novel Epothilone Aziridines. Org Lett. 2001;3:2693–2696. doi: 10.1021/ol016273w.

- 25.Microsomal epoxide hydrolase (mSH) is also blocked by ureas and related functionality: Morisseau C, Newman JW, Dowdy DL, Goodrow MH, Hammock BD. Inhibition of Microsomal Epoxide Hydrolases by Ureas, Amides, and Amines. Chem Res Tox. 2001;14:409–415. doi: 10.1021/tx0001732.

- 26.Nelson MJ, Seitz SP, Cowling RA. Enzyme-bound Pentadienyl and Peroxyl Radicals in Purple Lipoxygenase. Biochem. 1990;29:6897–6903. doi: 10.1021/bi00481a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.For early indications that lipophilic ureas might also harbor EET mimetic properties, see: Olearczyk JJ, Field MB, Kim IH, Morisseau C, Hammock BD, Imig JD. Substituted Adamantyl-Urea Inhibitors of Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase Dilate Mesenteric Resistance Vessels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:1307–1314. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.103556.

- 28.Rousseau G, Strzalko T, Roux MC. Preparation of Large Ring Acetylenic Lactones by Iodolactonization. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:4503–4505. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ochiai M, Sueda Takuya. Tetrahydrofuranylation of Alcohols Catalyzed by Alkylperoxy-l3- iodane and Carbon Tetrachloride. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:3557–3559. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu Y, Deck JA, Hunsaker LA, Deck LM, Royer RE, Goldberg E, Vander Jagt DL. Selective Active Site Inhibitors of Human Lactate Dehydrogenases A4, B4, and C4. Biochem Pharm. 2001;62:81–89. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00636-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pratt PF, Falck JR, Reddy KM, Kurian JB, Campbell WB. 20-HETE Relaxes Bovine Coronary Arteries Through the Release of Prostacyclin. Hypertension. 1998;31:237–241. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.1.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beetham JK, Tian T, Hammock BD. cDNA Cloning and Expression of a Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase from Human Liver. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;305:197–201. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wixtrom RN, Silva MH, Hammock BD. Affinity Purification of Cytosolic Epoxide Hydrolase using Derivatized Epoxy-Activated Sepharose Gels. Anal Biochem. 1988;169:71–80. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90256-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones PD, Wolf NM, Morisseau C, Whetstone P, Hock B, Hammock BD. Fluorescent Substrates for Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase and Application to Inhibition Studies. Anal Biochem. 2005;343:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.