Abstract

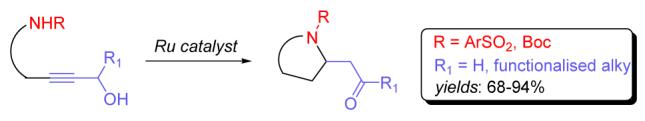

The Ruthenium catalyzed, atom-economical domino redox isomerisation/cyclization of tethered aminopropargyl alcohols is reported. This process displays a broad scope and functional group tolerance. Furthermore, it presents a novel retrosynthetic disconnection linking simple and easily available, linear propargyl alcohols with added-value nitrogen heterocycles in a single catalytic step.

Nitrogen-containing heterocycles are ubiquitous subunits of a variety of biologically active substances.1 Although this has spurred the development of a considerable body of synthetic methods aimed at their efficient preparation,2 there is a continuous need for new processes which can produce functionalized azacyclic substructures which maximize atom economy.

Our laboratory has recently been interested in harnessing the potential of alkynes as vehicles for bond-forming reactions.3 Although the chemistry of the venerable carbonyl group offers multiple possibilities for the elaboration of complexity and the forging of new carbon-carbon and carbon-heteroatom bonds, we believe that the triple bond, with its robustness and inertness towards many of the typical conditions used to manipulate carbonyl functionality, presents itself as a very appealing alternative. The design of mild and chemoselective methods for the activation of alkynes constitutes an exciting field at the forefront of developments in contemporary organometallic chemistry.4

One such method, termed the ruthenium-catalyzed redox isomerisation,5 implicitly renders a propargyl alcohol as a suitable synthon for an enal/enone, greatly reducing the number of operational manipulations of such sensitive intermediates. We hypothesized that the ability to juxtapose an appropriately substituted nitrogenated tether with a propargyl alcohol appendage could allow the direct synthesis of nitrogen heterocycles by a reaction cascade composed of redox isomerisation and intramolecular cyclization, as shown in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Proposal for a domino redox isomerisation/cyclization reaction of tethered propargyl alcohols

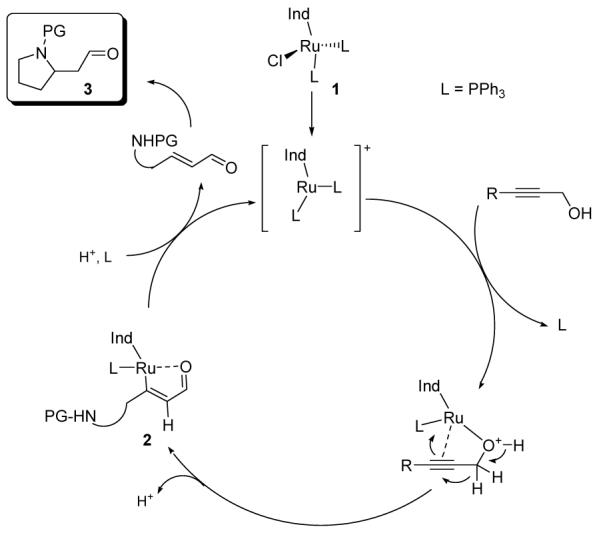

Thus, following complexation of the active catalyst derived from 1 to the triple bond and activation of the alcohol substituent, a [1,2]-hydrogen shift should provide the vinylmetal species 2.5 From this intermediate, the desired azacyclic products 3 could be formed either through protonolysis of 2 and Michael addition (the latter of which may be assisted by the Ru complex) or through nitrogen coordination to Ru and reductive elimination.

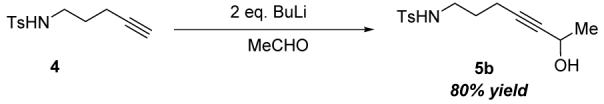

Key advantages of such a strategy, apart from the inherent atom economy of the whole process, lie in minimizing the manipulations of sensitive, α,β-unsaturated carbonyl functionality as well as providing ripe opportunity to take advantage of the unique reactivity of terminal alkynes in the preparation of substrates. For instance (equation 1), double deprotonation of the known ω-alkynyltosylamine 46 followed by quenching the dianion with acetaldehyde cleanly provides the aminoalcohol substrate 5b in high yield, with no need for functional group manipulations.

|

(1) |

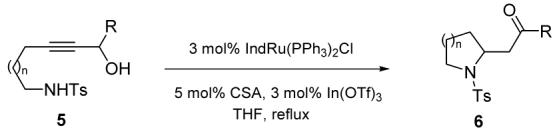

Gratifyingly, this plan proved immediately successful. In one of our first attempts (Table 1, entry 1), reacting the tosylaminoalcohol 5a with catalytic amounts of the ruthenium complex 1, in the presence of indium triflate and camphorsulphonic acid (CSA), directly provided pyrrolidine 6a in 75% yield from a simple acyclic precursor. The ability to successfully isolate aldehyde 6a bears testament to the mildness of this catalytic system.

Table 1.

Redox isomerisation of tethered (tosylamino)propargyl alcohols

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | n | R | Yielda |

| 1 | 1 | H (6a) | 75% |

| 2 | 1 | Me (6b) | 79% |

| 3 | 1 | -(CH2)2Ph (6c) | 92% |

| 4 | 1 | -(CH2)4CO2Et (6d) | 77% |

| 5b | 2 | H (6e) | 77% |

| 6b | 2 | Me (6f) | 72% |

| 7b | 2 | -(CH2)2(6g) | 68% |

| 8b | 2 | -CH2OBn (6h) | 80% |

All yields are for pure, isolated products.

Performed with 10 mol% CSA (see Scheme 1).

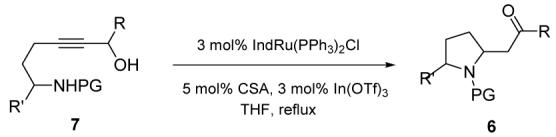

We then examined the scope of this transformation. It can be seen in Table 1 (entries 1-4) that a variety of differently substituted pyrrolidines are readily accessible from simple propargyl alcohols through this methodology. Importantly, all reactions proceed to completion within short reaction times (60 minutes), regardless of whether the carbonyl entity generated is an aldehyde or a ketone.7

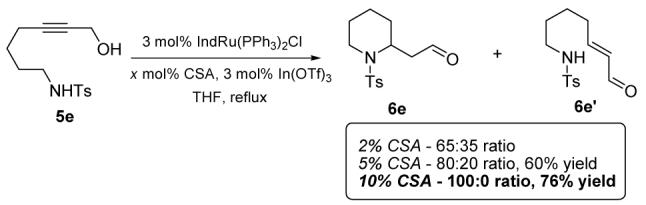

Extension to the homologous piperidines was then sought. In the event, a slight modification of the reaction conditions proved necessary (Scheme 2). As shown, increasing the amount of acid co-catalyst (CSA) was crucial in order to obtain full conversion of substrate to the piperidine product.8 Interestingly, we observed a direct proportionality effect between the amount of acid employed and the ratio of cyclic/acyclic product, an observation which is counterintuitive as one would have predicted that such a cyclization might be favored by increasingly basic, rather than acidic conditions (Scheme 2).9,10

Scheme 2.

Study on the formation of piperidine 4e

The functional group tolerance of this reaction is high. In particular, aromatic rings (Table 1, entries 3 and 7), esters (entry 4) and ethers (entry 8) all can be present without interfering with the catalytic system.

Furthermore, other widely employed nitrogen-protecting moieties also function as competent nucleophiles, as shown in Table 2 (PG = Boc, benzenesulfonyl and nosyl). It is interesting to note that changing the nitrogen substituent on a similar substrate (entries 1-4) appears to have only a slight influence on the efficiency of the reaction.11 This is an important observation, given the notable ease of unraveling of the Boc or Nosyl moieties.12

Table 2.

Comparative redox isomerisation of differently substituted aminopropargyl alcohols

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R | R | PG | Yielda |

| 1 | Me | H | Ts(6e) | 79% |

| 2 | Me | H | SO2Ph (6i) | 92% |

| 3 | Me | H | o-Ns (6j) | 85% |

| 4 | Me | H | Boc (6k) | 77% |

| 5 | H | Ph | Boc (6l) | 75%b |

All yields are for pure, isolated products.

Isolated as a 3:1 mixture of diastereomers.

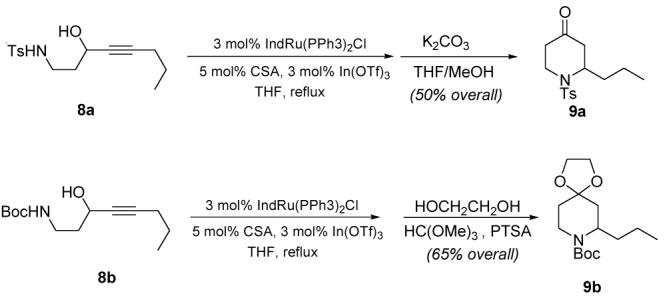

Finally, we found that shifting the position of the propargyl alcohol through the carbon backbone of the substrates results in interesting variations on this theme. For instance (Scheme 3), if the internal propargyl alcohol 8a is employed as a substrate, a simple one-pot, two-stage operation (addition of methanolic potassium carbonate to the mixture) furnishes the tetrahydropiperidone 9a in good yield. In complementary fashion, if the cyclization step is carried out under acidic conditions,13 the analogous N-Boc piperidinone ketal 9b can be obtained in 65% overall yield. Such piperidinone derivatives are very useful building blocks for drug discovery,14 and the ability to obtain cyclised products with different levels of protection of the carbonyl group is bound to be an asset in multistep synthetic planning.

Scheme 3.

Access to 4-piperidinones

In summary, we have developed a new atom-economical,15 domino synthesis of nitrogen heterocycles. It was shown that both sulfonamides and carbamates are compatible with the overall process and participate in the domino reaction to form heterocycles via exo and endo type cyclizations. Given the inherent availability of propargyl alcohols through classical alkynylation chemistry, this catalytic domino reaction remarkably disconnects the α-position of a substituted nitrogen heterocycle to a triple bond (of a propargyl alcohol) in a retrosynthetic manner, further increasing the arsenal of possible chemical approaches to the synthesis of alkaloids. Further investigations on this process are underway and will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health (NIH-13598) for their generous support of our programs. N.M. is grateful to the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT) for the awarding of a Post-doctoral fellowship. We thank Johnson Matthey for a generous gift of ruthenium complexes.

References

- (1).See, for example: Cordell GA.The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology 200054Academic Press; San Diego: and others in this series. [Google Scholar]

- (2) (a).(b) Lopez MD, Cobo J, Nogueras M. Curr. Org. Chem. 2008;12:718–750. [Google Scholar]; (c) Michael JP. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2008;25:139–165. doi: 10.1039/b612166g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For recent reviews, see: Lawrence AK, Gademann K. Synthesis. 2008:331–351.

- (3) (a).Trost BM, Ball ZT, Laemmerhold KM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10028–10038. doi: 10.1021/ja051578h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Trost BM, Weiss AH.Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2007467664–7666. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4) (a).(b) Trost BM, Toste FD, Pinkerton AB. Chem. Rev. 2001;101:2067–2096. doi: 10.1021/cr000666b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Trost BM, Krische MJ. Synlett. 1998:1–16. [Google Scholar]; (d) Jang H-Y, Krische MJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:653–661. doi: 10.1021/ar020108e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Montgomery. J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000;33:467–473. doi: 10.1021/ar990095d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Stang PJ, Diederich F.VCH Modern Acetylene Chemistry 1995Weinheim: For reviews on bond-forming reactions of acetylenes, see: [Google Scholar]

- (5) (a).Trost BM, Livingston RC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:9586–9587. [Google Scholar]; (b) Trost BM, Livingston RC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:11970–11978. doi: 10.1021/ja804105m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).See the Supporting Information.

- (7).The catalytic loadings could also be lowered even further (to 1 mol% of 1), though this resulted in an increase of the reaction time with little variation of yield. For instance, Table 1, entry 1 – 1 mol% 1, 1 mol% In (OTf)3, 3 mol% CSA results in 4 h reaction, 69% yield.

- (8) (a).(b) Weintraub PM, Sabol JS, Kane JM, Borcherding DR. Tetrahedron. 2003:2953–2989. [Google Scholar]; (c) Buffat MGP. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:1701–1729. [Google Scholar]; For recent reviews on the synthesis of piperidines, see: Laschat S, Dickner T. Synthesis. 2000. pp. 1781–1813.

- (9).Control experiments reveal that the conversion ofacyclic 6e‘ to cyclized 6e appears to require the presence of both the ruthenium catalyst and the acid additive.

- (10).Unsurprisingly, when substrates possessing a longer tether are used azepine formation does not spontaneously take place under these conditions and only the acyclic, α,β-unsaturated aldehyde is obtained.

- (11) (a).(b) For examples of ruthenium-promoted synthesis of nitrogen heterocycles through C-N bond formation, see: Trost BM, Pinkerton AB, Kremzow D.J. Am. Chem. Soc 200012212007–12008. [Google Scholar]; (c) Li G-Y, Chen J, Yu W-Y, Hong W, Che C-M. Org. Lett. 2003;5:2153–2156. doi: 10.1021/ol034614v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Deng Q-H, Xu H-W, Yuen AW-H, Xu Z-J, Che C-M. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1529–1532. doi: 10.1021/ol800087p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For examples of ruthenium-promoted synthesis of nitrogen heterocycles through C-N bond formation, see: Naota T, Murahashi S. Synlett. 1991:693–694.

- (12) (a).Kocienski PJ. Protecting Groups. Georg Thieme; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]; (b) Greene TW, Wuts PGM. Protecting Groups in Organic Chemistry. Wiley; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Abrunhosa-Thomas I, Roy O, Barra M, Besset T, Chalard P, Troin Y. Synlett. 2007:1613–1615. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Watson PS, Jiang B, Scott B. Org. Lett. 2000;2:3679–3681. doi: 10.1021/ol006589o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Trost BM. Science. 1991;254:1471–1477. doi: 10.1126/science.1962206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.